INTRODUCTION

On July 13, 2013, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi posted #BlackLivesMatter on the micro-blogging site Twitter. Cullors, Garza, and Tometi created the hashtag to protest the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed African American teenager. The hashtag gained traction on the Internet throughout the remainder of 2013, as advocates for police reform utilized it to express their complex emotions in response to several high-profile cases where unarmed African American men and women died at the hands of police officers (Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Garza Reference Garza2014; Hockin and Brunson Reference Hockin and Brunson2018).

The phrase Black Lives Matter (BLM) gained even greater currency in our society when it became the organizing principle and mantra of the protests that swept through the nation in the wake of the shooting death of Michael Brown, an unarmed African American teenager, by a white police officer in Ferguson, MO (Bonilla and Rosa Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015; Jackson and Welles Reference Jackson and Welles2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016, 13–15). Since the summer of 2014, the BLM movement has grown into a network of grassroots organizations representing more than 30 American cities and four countries outside of the United States (Ransby Reference Ransby2015; Rickford Reference Rickford2016). Moreover, the visibility of large BLM protests in New York City; Oakland, CA; and Chicago, IL between 2014 and 2016 garnered considerable attention from the U.S. media and registered in the national consciousness on public opinion surveys (Horowitz and Livingston Reference Horowitz and Livingston2016; Neal Reference Neal2017).

As is often the case when new movements capture our attention, the BLM movement is now a hot topic of debate in both the public sphere and academia. The debate in both quarters is focused on the tactics and organizational structures that BLM activists employ to promote social change. Some critics of the movement have argued that its focus on disruptive protest tactics, decentralized organizational structures, and unwillingness to negotiate with political elites in the gradualist realm of public policy formation will ultimately limit the success of the movement. On August 24, 2015, for example, Barbara Reynolds, who described herself as a “septuagenarian grandmother” and “activist in the civil rights movement of the 1960s,” penned a powerful opinion editorial in the Washington Post that urged BLM activists to embrace the “proven methods” of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. “The loving, nonviolent approach is what wins allies and mollifies enemies,” Reynolds argued in her piece, “[but] what we have seen come out of Black Lives Matter is rage and anger—justifiable emotions, but questionable strategy” (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2015).

President Barack Obama, who got his start in politics as a community organizer in Chicago, IL, made a similar critique of the movement on a trip to England in 2016. While speaking at a town hall event in London on April 23, 2016, President Obama summed up the BLM movement as follows:

[The Black Lives Matter movement is] really effective in bringing attention to problems…Once you've highlighted an issue and brought it to people's attention and shined a spotlight, and elected officials or people who are in a position to start bringing about change are ready to sit down with you, then you can't just keep on yelling at them. And you can't refuse to meet because that might compromise the purity of your position. The value of social movements and activism is to get you at the table, get you in the room, and then to start trying to figure out how is this problem going to be solved (Shear and Stack Reference Shear and Stack2016).

In short, these critiques suggest that the BLM movement would be more successful if it emulated African American movements that ushered in what the sociologist John Skrentny (Reference Skrentny2002) calls the “minority-rights revolution” of the 1960s.

Ms. Reynolds's and President Obama's skepticism about the BLM movement's tactics and impact are not widely shared in the African American community. On the contrary, the movement receives very positive appraisals from African Americans on public opinion surveys. A national probability survey conducted by Pew Research in 2016 found that 65% of African Americans express support for the movement (Horowitz and Livingston Reference Horowitz and Livingston2016). Similarly, a nationally representative internet survey conducted by the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy at Northwestern University found that 82% of African Americans believe that the BLM movement is at least moderately effective at achieving its stated goals (Tillery Reference Tillery2017). At the same time, there is evidence in these surveys that African Americans do share some of the concerns about organizational structure that the critics of the movement have raised. Indeed, 64% of the respondents to the Northwestern University survey stated that they believed that the BLM movement would be more effective if it had a more centralized leadership structure (Tillery Reference Tillery2017).

The organizational and tactical differences between the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the BLM movement are also at the center of the burgeoning scholarly literature on the subject. However, academic researchers have largely set aside the question of the movement's long-term impact on policy—what both Ms. Reynolds and President Obama describe as “winning”—to focus on building knowledge about its internal dynamics and representations in the public sphere through detailed case studies and narrative accounts (Harris Reference Harris2015; Lindsey Reference Lindsey2015; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016). Thus far, three points of consensus have emerged within this nascent scholarly literature on the BLM movement. The first point is that BLM activists are intentionally rejecting the “respectability politics” model that animated the African American Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s (Harris Reference Harris2015, 37–39; Rickford Reference Rickford2016, 36–37; Taylor Reference Taylor2016, 153–191). Second, BLM activists tend to utilize frames based on gender, LGBTQ, and racial identities to describe both the problems they are combatting and the solutions that they are proposing through contentious politics (Harris Reference Harris2015, 37–39; Lindsey Reference Lindsey2015; Rickford Reference Rickford2016, 36–37). Finally, there is consensus within the literature that the BLM activists do not define their aims in terms of linear policy objectives and that they see intrinsic value in the disruptive repertoires of contention that they utilize to draw attention to their causes (Rickford Reference Rickford2016, 36; Taylor Reference Taylor2016).

The portrait of the BLM movement that emerges from the scholarly literature resembles more closely the “new social movements” that have emerged in Europe and the United States since the 1980s than the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Indeed, several studies of the BLM movement make this point. Harris (Reference Harris2015), for example, has argued that “the spontaneity and the intensity of the Black Lives Matter movement is more akin to other recent movements—Occupy Wall Street and the explosive protests in Egypt and Brazil—than 1960s [African American] activism” (35). Rickford (Reference Rickford2016) even goes as far as to say that the Occupy Wall Street protests were a “precursor” to the BLM movement. In short, the scholarly literature on the BLM movement makes the case that critics of the movement should not expect it to look and feel like Montgomery, Selma, and the other iconic campaigns of the 1960s movement—with their focus on respectability, rationally purposive action, and negotiation with political elites (McAdam Reference McAdam1982; Morris Reference Morris1981; Reference Morris1986).

This paper seeks to contribute to the scholarly conversation about the BLM movement by analyzing how six social movement organizations (SMOs) affiliated with the movement use Twitter. The aim is to determine if systematic content analyses of the ways that these SMOs use the micro-blogging site support the interpretations developed through the extraordinarily high-quality case studies referenced above. In other words, does examining the tweets of SMOs affiliated with the BLM movement as discrete speech acts in the African American counterpublic sphere lead us to the conclusion that the movement is more like Occupy Wall Street and other new social movements than the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s?

This is not the first study of how BLM activists use social media. On the contrary, there is a growing literature on this question within the fields of communications, African American Studies, and social movement studies. These studies have almost exclusively focused on the hashtags that drive conversations between BLM activists and their supporters and opponents on Twitter and Facebook. We have learned through these analyses that hashtags raise the profile of the BLM movement and spur action within the African American community (Cox Reference Cox2017; Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Ince, Rojas, and Davis Reference Ince, Rojas and Davis2017). These studies have also demonstrated that usage of hashtags gains the attention of political elites and sometimes encourages them to take positions in support of the movement (Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2018). What has been missing in this literature on social media usage is an account of the reasons that BLM activists use Twitter—to mobilize resources, communicate with political elites, or simply to convey their emotional states—and the types of frames that they construct and deploy within their tweets. The core argument made in this paper is that understanding these two dynamics will give us a greater sense of how BLM activists see their movement and facilitate our ability to make fine-grained classifications of the movement based on the rubrics provided by social movement theory.

The paper examines 18,078 tweets produced by six SMOs affiliated with the BLM movement—Black Lives Matter (@Blklivesmatter); Black Lives Matter New York City (@BLMNYC), Black Lives Matter Los Angeles (@BLMLA), Black Lives Matter Chicago (@BLMChi), Black Lives Matter Washington, DC (@DMVBlackLives), and Ferguson Action (@FergusonAction). These accounts were selected for three reasons. The first reason is their reach. When counted together, these six organizations have more than 350,000 followers on Twitter. Second, the SMOs that manage these accounts are responsible for some of the most visible protests associated with the BLM movement between 2013 and 2016 (Taylor Reference Taylor2016). Finally, the six accounts provide considerable regional variation. Moreover, the @Blklivesmatter account represents the BLM Global Network and not a geographically-defined chapter. Analyzing content from this account will allow us to determine if there are distinctions to be made between the behavior of the umbrella network and the place-based organizations.

The main research questions explored in this paper are: How do BLM organizations communicate on Twitter? Do they use Twitter primarily to mobilize resources in order to build the capacity of their SMOs? Do they tweet about specific policy goals? Do the six SMOs in this study use Twitter to communicate frames that place gender, LGBTQ, and racial identities at the center of their activism? Finally, do the BLM groups examined in this study encourage their supporters to pursue disruptive repertoires of contention over more conventional forms of political behavior?

The analyses presented below confirm the view that the BLM movement is best understood as a new social movement. Indeed, less than one-third of the tweets examined in this study were aimed at mobilizing resources or signaling political elites. Moreover, only about one-third of the tweets generated by the SMOs communicated meanings through frames about gender, LGBTQ, and racial identities. While the New Social Movement paradigm is the best theoretical lens for understanding how BLM organizations communicate on Twitter, the analyses presented below show that it is not the only window onto the on-line activism of these groups. This is so because all six of the organizations examined in this study tweeted more to urge their adherents to participate in the political system than they did to urge the pursuit of disruptive protest activities.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. The next section presents a discussion on the theoretical context for the study. It describes both the development of the New Social Movement paradigm within the literature on social movements and the core concepts that animate it as a research program. This section also presents three hypotheses derived from the new social movement theory about of the types of communication that we should expect to see in the Twitter feeds of the six SMOs examined in the content analysis studies. Section “Method, Data, and Study Designs” describes the data and methods utilized to conduct the three content analysis studies that provide the empirical evidence presented in the paper. Section “Findings” presents the main findings from the content analysis studies. It will show that, with some caveats, the findings of the three studies support the view that the BLM movement is best understood as a New Social Movement. The “Conclusions” section describes the broader significance of the findings for our larger understanding of the BLM movement and the literature on social movements.

THEORETICAL CONTEXT AND HYPOTHESES

As we have seen, several recent studies of the BLM movement have asserted that it has more in common with Occupy Wall Street than the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s in terms of its organizational structure, tactics, and representations in the public sphere (Harris Reference Harris2015; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016). From the standpoint of classifying the BLM movement using extant theories of social movements, this argument suggests that the movement is more intelligible through the lens of the new social movement paradigm than the dominant resource mobilization and political process theories. This is a very novel argument for the simple fact that social movement scholars have “mainly applied the theories [associated with the new social movement paradigm] to white, middle-class, progressive causes that cut across political and cultural spheres at the expense of paying attention to struggles that pertain to economic and racial issues” (Carty Reference Carty2015, 27). Thus, the rise of the BLM movement has precipitated the need to test the core assumptions of both paradigms against the behavior of the current generation of African American activists.

The dividing line between the new social movement perspective and the resource mobilization and political process theories is the main assumption that they make about the motivations of activists. Both resource mobilization and political process theories interpret the motivations of protestors through the three axioms of what Karl Dieter Opp (Reference Opp, Snow, Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013) calls “the most general vision of rational choice theory” (1051). The first axiom is that both the leaders of social movements and individual participants are rational, purposive actors (Oberschall Reference Oberschall1973; Opp Reference Opp1989; Reference Opp, Snow, Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013; Schwartz Reference Schwartz1976). Second, those who participate in social movements engage in cost-benefit analyses before they undertake an action (Klandermans Reference Klandermans1984; Reference Klandermans1997; Muller and Opp Reference Muller and Opp1986; Oberschall Reference Oberschall1973; Reference Oberschall1980; Opp Reference Opp, Snow, Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013). Finally, the rational choice perspective holds that movement participants are utility-maximizers who will “do what is best for them” (Opp Reference Opp, Snow, Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013, 1051).

Building on this rationalist perspective, resource mobilization theorists developed a model of social movements that elevated the ability of purposive activists to mobilize resources—e.g., labor, money, communication networks, facilities—in support of target goals to the main metric that differentiated successful movements from unsuccessful ones (McAdam Reference McAdam1982; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Morris Reference Morris1981; Reference Morris2000; Tilly Reference Tilly1978; Zald Reference Zald, Morris and Mueller1992). The proponents of resource mobilization theory also stress how important it is for the leaders of SMOs to remain attentive to environmental factors and shifts in the political opportunity structure (Freeman Reference Freeman1975; Jenkins and Perrow Reference Jenkins and Perrow1977; McAdam Reference McAdam1982; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977, 1224–1226; Morris Reference Morris1993; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1989). The political process theory of social movements grew out of this focus on political opportunity structures. Beginning in the 1970s, several scholars began to argue—based largely on analyses of the Civil Rights Movement—that sending the right signals to governing elites has the potential to shift political opportunity structures. Under this view, movements that successfully signal and negotiate with governing elites are more likely to attain their strategic goals than ones that fail at these tasks (McAdam Reference McAdam1982; McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001; Tilly, Tilly, and Tilly Reference Tilly, Tilly and Tilly1975). Despite the hegemony of resource mobilization and political process theories in social movement studies, even the leading practitioners of these approaches acknowledge that they do not explain every kind of movement. Zald (Reference Zald, Morris and Mueller1992), one of the principal progenitors of resource mobilization theory, for example, has written that the paradigm “does not begin to have all of the answers or pose all the important problems” that scholars must address about social movements (342).

Zald's insightful comments about the limitations of the resource mobilization and political process models were undoubtedly informed by the rise of the New Left movements in Europe in the middle of the 1980s. The emergence of these movements “stimulated,” in the words of Johnston et al. (Reference Johnston, Larana, Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994), “a provocative and innovative reconceptualization of the meaning of social movements” (3). This was so because the activists that populated these movements repeatedly demonstrated that they were less concerned with mobilizing resources to affect public policy debates or shift the trajectory of political institutions than with performing and representing their distinctive identities within post-industrial cultures (Boggs Reference Boggs1986; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Larana, Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994; Melucci Reference Melucci and Keane1988; Reference Melucci1989; Offe Reference Offe1985). Indeed, these movements tend to place messages about these identities at the center of the collective action frames that they proliferate in the public sphere (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Snow and Benford Reference Snow and Benford1988; Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Burke Rochford, Worden and Benford1986).

Moreover, the new social movements have demonstrated that for some activists signifying about these identities in the public sphere is an end unto itself (Dalton Reference Dalton1990; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Larana, Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994; Offe Reference Offe1985; Pichardo Reference Pichardo1997; Touraine Reference Touraine1971). In other words, sometimes the messages that activists associated with new social movements generate are what economists and social movement scholars call “expressive behavior” (Chong Reference Chong1991; Downs Reference Downs1957; Hamlin and Jennings Reference Hamlin and Jennings2011; Hillman Reference Hillman2010; Turner Reference Turner and Kriesberg1981). Hillman (Reference Hillman2010) has defined expressive behavior as “the self-interested quest for utility through acts and declarations that confirm a person's identity” (403). Turner (Reference Turner and Kriesberg1981) has argued that “expressive behavior” is often undertaken by an activist in order to “express support for the cause [of the movement] regardless of whether it produces direct and visible consequences” (11). Finally, many scholars have noted that expressive behavior is often emotionally charged and or undertaken to provoke an emotional response from fellow adherents or opponents of social movements (Clarke 1966; Chong Reference Chong1991, 80–81; Goodwin et al. Reference Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2009, 14–16).

The focus on signification within the new social movements does not mean that they ignore the importance of protests. On the contrary, a characteristic feature of these movements is that they encourage their adherents to pursue disruptive repertoires of contention through both mass mobilizations and individual actions (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Larana, Gusfield, Johnston, Larana and Gusfield1994; Klandermans and Tarrow Reference Klandermans and Tarrow1988). Moreover, the horizontal organizational structure of these movements makes it possible for activists to pursue multiple repertoires of contention within the same protest (Melucci Reference Melucci1996). In other words, because they are leaderless movements, there is no enforcement of tactical or messaging discipline on activists. It is also important to note that the new social movements are fueled by part-time activists who do not necessarily draw distinctions between participating in disruptive protests, pursuing individual acts of resistance, and even engaging in Internet activism or “hacktivism” (Carty Reference Carty2015; Jordan Reference Jordan2002).

Why analyze the Twitter usage of BLM-affiliated groups to ascertain the dynamics of the movement? There are multiple reasons that studying tweets provides an important window onto the movement. First, the BLM movement was born on Twitter and the micro-blogging site remains the primary tool that activists use to make representations about the movement in the public sphere (Cox Reference Cox2017; Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2018; Ince, Rojas, and Davis Reference Ince, Rojas and Davis2017). Second, Twitter has been widely adopted in the African American community. Indeed, while African Americans are only 13.5% of the U.S. population, they constitute 25% of the American Twittersphere (Brock Reference Brock2012). Third, studies have shown that Twitter is a space where African Americans are deeply engaged in a national conversation about race relations (Carney Reference Carney2016; Nakamura Reference Nakamura2008).

The extant studies of the role that Twitter plays in the BLM movement have focused on tracking the rise and impact of the distinctive hashtags that activists generate to mark their tweets. While this approach has yielded the great insights that the tweets BLM activists generate resonate with and spur their followers to protest and engage in hacktivism (Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2018; Ince, Rojas, and Davis Reference Ince, Rojas and Davis2017), there is still a lot that we do not know about the overall landscape of the BLM Twittersphere. For example, we do not know if BLM activists spend most of their time on Twitter trying to mobilize resources and communicate with governing elites as the resource mobilization and political process theories suggest they should or generating expressive tweets aimed at making representations about gender, racial, and LGBTQ identities.

This paper seeks to gain some clarity on these dynamics by asking the following questions: Do BLM activists use Twitter primarily to mobilize resources or to communicate through frames that promote expressive utility about their identities? Do BLM activists use Twitter to urge their adherents to pursue certain repertoires of contention over others? These questions will be pursued through content analyses of the public Twitter feeds of six SMOs affiliated with the BLM movement. The following three hypotheses were designed to produce strong tests of the new social movement paradigm and resource mobilization and political process theories:

H1

The Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain fewer tweets aimed at mobilizing resources than tweets generated to achieve other communicative goals.

H2

The Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain more social movement frames that call attention to issues related to gender, racial, and LGBTQ identities than universalist frames related to socioeconomic status or individual rights.

H3

The Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain more tweets that urge their followers to pursue disruptive repertoires of contention over other forms of protest or political action.

The following section describes the data and explicates the design of the three content analysis studies developed to test these hypotheses.

METHOD, DATA, AND STUDY DESIGNS

Social scientists have used content analysis to understand political and cultural trends since the middle of the twentieth century (Franzosi Reference Franzosi2004; Holsti Reference Holsti1969; Krippendorff Reference Krippendorff2004; Lasswell Reference Lasswell and Leites1965; Neuendorf Reference Neuendorf2002; Weber Reference Weber1990). Over the past three decades, the method has become an analytic mainstay among scholars of racial and ethnic politics (e.g., Caliendo and McIlwain Reference Caliendo and McIlwain2006; Entman Reference Entman1997; Lee Reference Lee2002; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Reeves Reference Reeves1997; Tillery Reference Tillery2011). Three content analysis studies designed to test the hypotheses described in the previous section provide the empirical foundation for this paper. The data were extracted from the public Twitter feeds of six SMOs—@Blklivesmatter; @BLMchi (Chicago, IL); @BLMNYC (New York, NY); @DMVBlackLives (Washington, DC); @FergusonAction (Ferguson, MO)—affiliated with the BLM movement. The @Blklivesmatter feed is the account maintained by the national BLM organization established by Patrice Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometti, who created #BlackLivesMatter in 2013. The other five accounts are regional chapters of the same organization.

The Python program was used to scrape the feeds of these Twitter accounts between December 1, 2015 and October 30, 2016.Footnote 1 This time period was selected for two reasons. First, it coincides with the peak of the 2016 national elections in the United States. The resource mobilization and political process theories suggest that BLM-affiliated organizations should have strong incentives to mobilize their adherents to engage with the political system in such periods. Second, the first high-profile studies confirming that African Americans were disproportionately the victims of police killings were released by academics, media outlets, and grassroots organizations (like the BLM affiliate Mapping Police Violence) in 2015 (Makarechi Reference Makarechi2016). Regardless of the theoretical lens that one uses to interpret the BLM movement, it should follow that the release of these data into the public sphere would create what the social movement scholar James Jasper (Reference Jasper1997) calls a “moral shock” that would be likely to spur both recruitment and activism in the BLM movement.

The three content analysis studies utilized a two-coder system. Both coders read the entire universe of 18,078 tweets that appeared on the public feeds of the six BLM-affiliated accounts within the selected date range. The average intercoder reliability for the three content analysis studies is 87%. In the 13% of cases where there were disagreements between the first two coders, a third coder was utilized to break these ties. Further details about the goals and design features of each of the three content analysis studies are presented below.

The task at the center of Study 1 is coding the tweets and sorting them into three categories based on their apparent communicative function—resource mobilization, informational, and expressive. Study 1 was designed to provide an empirical test of Hypothesis 1, which holds that the Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain fewer tweets aimed at mobilizing resources than tweets generated to achieve other communicative functions. Tweets sorted into the resource mobilization category provide information about the SMOs' activities and/or encourage adherents to provide support to the SMO or broader BLM movement through financial contributions, non-monetary donations, protest actions, or political activity aimed at supporting the movement. Tweets coded as informational share news about events and incidents that are happening in the BLM movement, the external political environment, and current events. Finally, tweets that are coded as expressive transmit emotional responses—e.g., anger, sadness, joy—to developments in the movement and external events. A finding that the six Twitter feeds contain fewer tweets aimed at resource mobilization than tweets in the other two categories will provide confirmation of Hypothesis 1.

Study 2 examines the content of the social movement frames that appear in the Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations. The goal of the study is to test Hypothesis 2, which holds that the Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain more social movement frames that call attention to gender, racial, and LGBTQ identities than universalist frames related to socioeconomic status or individual rights. Benford and Snow (Reference Benford and Snow2000) define social movement frames as “interpretive schemata” that activists deploy to simplify the world “by selectively punctuating and encoding objects, situations, events, experiences, and sequences of actions within one's present or past environment” (137). Collective action frames make both diagnostic and prognostic attributions (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Snow and Benford Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992, 137; Snow and Machalek Reference Snow and Machalek1984; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Burke Rochford, Worden and Benford1986). Finally, social movement theorists argue that collective action frames “enable activists to articulate and align a vast array of events and experiences so that they hang together in a relatively unified and meaningful fashion” (Snow and Benford Reference Snow, Benford, Morris and Mueller1992, 138). The coding scheme for this study will sort tweets that contain movement frames about African American identity into the category racial identity. Tweets that contain frames about gender and or the intersectional status of African American women will be coded as gender identity. Similarly, tweets that frame the BLM movement as concerned with LGBTQ issues will be coded as LGBTQ identity. Tweets that contain more universal frames—about the economy or individual rights—will be sorted into their own categories. A finding that the majority of tweets examined in Study 2 deploy gender, racial, and LGBTQ frames will confirm Hypothesis 2.

Study 3 examines all the tweets in the sample that urge the organizations' followers to take immediate action. The goal of this study is to test Hypothesis 3: the Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain more tweets that urge their followers to pursue disruptive repertoires of contention over conventional forms of political behavior. The coding scheme for Study 3 sorts the subset of tweets urging action in the public sphere into three categories based on the repertoires of contention that the SMOs are encouraging their followers to pursue. Tweets that urge disruptive protest actions will be sorted into the category labeled “disruptive protests.” Tweets that urge the adherents of the BLM movement to pursue action through the political system—e.g., registering to vote, voting, contacting government officials, etc.—will be coded as conventional actions. Finally, Study 3 will examine the validity of claims that the BLM movement incites violence against police officers made by some law enforcement officials and right-wing pundits (Bedard Reference Bedard2017; Russell Reference Russell2017). Study 3 will code all tweets that attempt to incite or urge violence into the “violent actions” category. This study will confirm Hypothesis 3 if the majority of tweets generated by the six BLM accounts urge disruptive protests or violent actions over conventional forms of participation.

FINDINGS

The three content analysis studies yielded some very interesting results. The findings of Study 1, which examined the types of communication—resource mobilizing, informational, and expressive—that the six BLM organizations generated most frequently on their Twitter feeds, were consistent with confirmation of Hypothesis 1. Again, Hypothesis 1 holds that the BLM organizations will generate fewer tweets aimed at mobilizing resources than pursuing other communicative goals. The coders successfully sorted all of the tweets in the sample into one of three categories. Moreover, the results of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), F(2,12) = 9.06, p = 0.003, confirm that there are statistically significant differences between the means of the three categories.

As Table 1 illustrates, all six of the Twitter feeds of the BLM groups contained fewer tweets in the resource mobilization category than in the informational and expressive communication categories. Overall, only 3,492 tweets, a figure that constitutes 19% of the sample, contained content aimed at mobilizing resources to strengthen the advocacy work of the six SMOs examined in this paper. The BLM chapter in Los Angeles, CA (@BLMLA) generated a quintessential example of tweets in this category on July 20, 2016, when they requested adherents to drop off supplies to support their #DecolonizeLACityHall protest. The text of the tweet reads: “#DecolonizeLACityHall nds [needs]: Tylenol, paper plates, foam board, coffee, deodorant, juice boxes, chairs, fruit. Drop off at 200 N. Main Street.” Another example comes from a tweet generated by the group Ferguson Action (@FergusonAction) on April 9, 2016 to ask their followers to register to participate in a national call for the #Justice4Gynnya campaign and add their names to a national database maintained by the Movement for Black Lives group. The tweet reads: “@mvmt4bl: 4/12 9PM We demand Justice! Register here for the call. #JusticeForGynnya.”

Table 1. Tweets by communicative goal

Source: Twitter (December 1, 2015 to October 31, 2016).

The largest category of tweets in the sample are expressive communications that demonstrate sadness or outrage with police shootings and other hardships faced by African Americans in the United States. As Table 1 shows, the coders assigned 7,525 tweets, a figure that represented 42% of the overall sample, to the Expressive category. On March 8, 2016, Black Lives Matter New York (@BLMNYC) generated a tweet expressing outrage about prosecutors in New York City deciding to not pursue charges against a police officer for shooting an African American man. The tweet, which reads “What a sham & a shame to not even bring a grand jury together to bring NYPD Officer Haste to trial for murdering #RamarleyGraham,” is perfectly representative of tweets sorted into the expressive category. Another excellent example from this category is when Black Lives Matter Chicago (@BLMChi) tweeted “@BLMYouth: We are justified in our pain” on September 14, 2016.

Informational tweets, generated to share stories and information about the movement and local and national news items, were the second largest category of tweets. As Table 1 illustrates, there were 7,061 informational tweets, a figure that comprises 39% of the overall sample, generated by the SMOs between December 2015 and October 2016. Most of the tweets in the informational category resemble the following tweet generated by the Washington, DC Metro area Black Lives Matter chapter (@DMVBlackLives) on March 9, 2016. The tweet, which reads “@NAACP_ODU: Roanoke, VA County Police Department responds to NAACP's concerns over officer-involved shooting now. #KionteSpencer,” circulated a news report about an officer-involved shooting in a neighboring jurisdiction. Another example comes from the Black Lives Matter chapter in Boston (@BLM_Boston). On December 28, 2015, the account generated a tweet that shared a news story about the case of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy who was shot by police in 2014 while playing with a toy gun in his neighborhood park in Cleveland, OH. The text of the tweet reads: “RT @BLM_216: The grand jury will announce NO INDICTMENT of the officers who shot Tamir Rice at 2:00 PM Eastern Time.” The fact that BLM groups generate a vast number of tweets simply to convey news reports is consistent with recent studies that have found that Twitter has become an important source of news for African Americans about the BLM movement and other issues (Cox Reference Cox2017; Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Jackson and Welles Reference Jackson and Welles2016; Rickford Reference Rickford2016).

The fact that the six SMOs affiliated with the BLM movement generated more than twice as many expressive tweets as ones aimed at resource mobilization confirms Hypothesis 1 and strengthens the argument that the BLM movement more closely resembles a new social movement than the social movements that emerged in the United States in the 1960s.

Study 2 examined the social movement frames that appeared in the public Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations. The aim of Study 2 is to provide a test of Hypothesis 2: the Twitter feeds of the six BLM organizations will contain more social movement frames that call attention to gender, LGBTQ, and racial identities than universalist frames related to socioeconomic status or individual rights. The coding scheme required two independent coders to read the entire universe of 18,708 tweets to determine which ones relayed distinct social movement frames.

The first noteworthy finding to come out of this study is that most of the tweets in the sample did not contain social movement frames. Indeed, only 4,292 of the tweets, a number that constitutes 23% of the overall sample, contain frames. Within this subset of the sample, the coders were able to identify five distinct categories of tweets. Moreover, the independence of these categories within the sample was confirmed by a one-way ANOVA: F(4,30) = 4.01, p = 0.010. As Figure 1 shows, 65% of the tweets in this segment of the sample—a total of 2,789 tweets—contain a frame that highlights violations to the individual rights of African Americans and makes demands based on the individual rights enshrined in the United States Constitution and guaranteed by state and local laws. The Black Lives Matter New York City (@BLMNYC) provided dozens of examples of this individual rights frame at the height of the #SwipeItForward campaign in July and August 2016. The goal of the campaign was to increase the presence of African American activists at major project and cultural events throughout the city by sharing funds on single use Metro cards. On August 29, 2016, for example, @BLMNYC tweeted: “#SwipeItForward Facts—Its ILLEGAL for someone to ask to be swiped into the train. But YOU can legally always offer to swipe them in.” The BLM groups also frequently quoted historical examples to convey frames about individual rights. On May 21, 2016, the Black Lives Matter Chicago chapter (@BLMChi) generated a tweet representative of this kind: “@BlackRT @DocMellyMel: #PanthersTaughtMe In organizing: “No rights without duties. No duties without rights. @LACANetwork @BLMLA @Blklivesmatter.”

Figure 1. Social movement frames by category.

The second largest category of social movement frames in the sample—13% of all tweets containing frames—are ones that focus on African American cultural expression. In the 575 tweets that the coders sorted into this category, the six BLM organizations commented on the distinctive contributions made by African Americans to popular culture in the United States through music, sports, and the visual arts. The Black Lives Matter chapter in New York City (@BLMNYC) provided excellent examples of the tweets deploying cultural frames of the movement. On September 22, 2016, @BLMNYC generated a tweet urging their adherents to support a gathering of artists that supported the movement. The tweet reads: “@occupytheory: Sat. Sept. 24. 3PM—Art Action Assembly in Manhattan. #decolonizethisplace.” The group also celebrated the importance of African American cultural production to the BLM movement. On August 28, 2016, for example, they tweeted “Visit us on ACTIVISM ROW @ #AfroPunk today! Come trade books written by Black Women. #BLERD” to announce that they were turning their booth at New York's AfroPunk festival into a book swap to circulate the work of African American women.

The coders identified 438 tweets that contained frames about gender identity. This figure constitutes 10% of all frames present in the sample. We know that BLM organizations put a lot of focus on amplifying the names of African American women who were victims of police brutality through the use of #SayHerName (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2015). The six SMOs examined in this study often framed the overall movement as a project to elevate African American women and girls. The Chicago chapter of BLM (@BLMChi) produced several excellent examples of this kind of tweet. On April 30, 2016, @BLMChi called on their followers to join a protest action to support women separated from their families due to incarceration in the Cook County prison. The tweet reads: “Join @MomsUnitedChicago @Supporthosechi & us for a vigil outside CCJail on 5/7 #ForgottenMoms.” On May 7, 2016, @BLMChicago urged their adherents to “support #BlackGirlMagic in Chicago and donate to @AssataDaughters! The[y’]re doing unique and critical work.”

There were 325 tweets in the sample that contained frames centering LGBTQ identities. This number, which is 7% of all tweets with frames, is lower than expected in light of the focus that some leading BLM activists have placed on amplifying the experiences of LGBTQ African Americans as victims of the “hetero-patriarchal” culture that is dominant in the United States of America (Rickford Reference Rickford2016, 36). Another unexpected finding is that 92% of the tweets utilizing frames about LGBTQ identities come from the @Blklivesmatter Twitter feed maintained by the national BLM campaign. In short, the five SMOs with geographic boundaries almost never framed the movement using LGBTQ identities during the period under study. On June 24, 2016, @Blklivesmatter generated an excellent example of the tweets sorted into this category to describe their #PoliceOutofPride protest actions designed to highlight what they argued is the dangerous over-policing of Pride Parades across the country. “As we work to protect ourselves from homophobic violence,” @Blklivesmatter tweeted, “it is important to remember we can't police away hate. #policeoutofpride.” On the day after the action, the group tweeted: “Pride was a riot. Of Queerness. Of Trans dignity. Of Gender Non-conformity. Led by folks of Color. Against the police. #PoliceOutofPride.”

The coders identified 189 tweets in the sample that framed BLM as a universal movement for economic equality. The tweets in this category, which constitute 3% of all tweets with frames, describe the BLM movement as fundamentally concerned with expanding the rights of workers and addressing inequalities rooted in socioeconomic status. The Ferguson Action (@FergusonAction) group generated several tweets in this category as they publicized their work through the #RECLAIMMLK campaign in January 2016. On January 15, 2016, for example, @FergusonAction tweeted: “@BYP_100: We're talking #BuildBlackFutures on MLK weekend because Dr. King was assassinated working to win black economic justice #ReclaimMLK.” Similarly, on January 20, 2016, @FergusonAction tweeted “@BaySolidarity: Invest in workers-Divest from Police! #underpaidoverpoliced #96Hours #RECLAIMMLK.”

There were, as Figure 1 illustrates, just 86 tweets—2% of all the tweets with frames—that contained frames of the BLM movement predicated on ideologies that stress African American group consciousness (e.g., Black Nationalism, Afro-pessimism, etc.). The Los Angeles chapter of Black Lives Matter (@BLMLA) produced several tweets that stressed African American solidarity to challenge Najee Ali, an advisor to Mayor Eric Garcetti and a frequent critic of the BLM movement in the Los Angeles media. On July 13, 2016, @BLMLA tweeted: “@LeonardFiles Najee Ali is a modern-day Benedict Arnold to the BLM and entire Black movement for police accountability.” Black self-love is also a consistent theme within this subset of tweets. On August 2, 2016, for example, Ferguson Acton (@FergusonAction) tweeted: “@4EdJustice: A1 the #Vision4BlackLives is a love note to our mov't. We center the wholeness of Black people. We see us. We Got us.” While the dearth of movement frames referring to African American identity within the text of tweets is interesting, we should not read too much into this finding. This is so because it is likely that the frequency with which BLM activists mark their tweets with #BlackLivesMatter obviates the need to generate additional frames based on racial identity within the texts of their tweets.

The relatively low number of frames within the tweets about gender and LGBTQ identities is somewhat surprising. After all, some of the most visible BLM activists in the U.S. media have frequently articulated that one of the movement's major goals is to “center” the lives and contributions of “Black Queer and trans folks, disabled folks, Black-undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all Black lives along the gender spectrum” (Garza Reference Garza2014). An important caveat to this finding is that the data are drawn from only one year in the 4-year life span of the BLM movement. As a result of this fact, it is plausible that gender and LGBTQ frames are more prevalent when we observe the longer arc of the movement. Subsequent studies should explore this issue to get a firmer sense of how much SMOs affiliated with the BLM movement actually work to frame the movement in terms of these identities. For now, it is sufficient to say that, while less than the predicted value, it is not trivial that 33% of the tweets generated by these organizations deployed one of these identity frames.

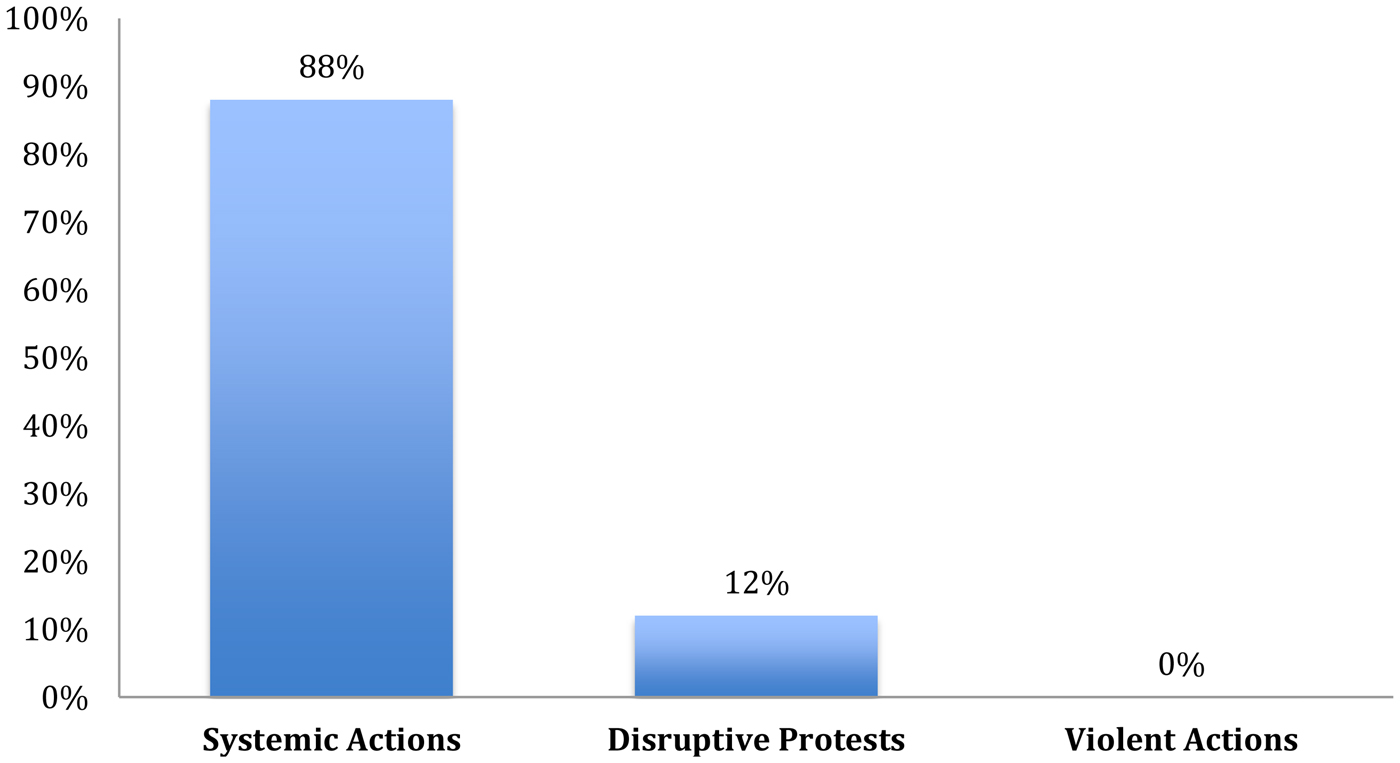

Study 3 examined the 7% of the tweets in the overall sample that contained specific calls to action. In other words, it focused on the 1,320 tweets where the six SMOs urged their adherents to immediately take an action. The primary goal of the study was to discern whether BLM activists more frequently urged their followers to pursue disruptive repertoires of contention—e.g., traffic blockades, the interruption of public meetings, occupation of businesses, etc.—or actions that fall within the conventional bounds of the political system. A secondary goal was to determine if BLM activists encouraged their adherents to engage in violence. As Figure 2 illustrates, the coders did not find one tweet in the entire dataset of 18,078 that urged the use of violence as a tactic. The coders were able to identify tweets that urged the pursuit of disruptive repertoires of contention and a second category that encouraged conventional forms of political behavior. Moreover, the results of a Student's t-test, t(10) = 4.60, p = 0.001, demonstrate that the means of these two categories are distinct.

Figure 2. Calls to action issued by BLM activists on Twitter.

During the height of the national BLM action to protest the killing of Philando Castile by police in Minneapolis, MN, New York City's Black Lives Matter chapter (@BLMNYC) generated several tweets that demonstrate the ways that these SMOs struck a balanced their calls for the use of disruptive tactics with calls for maintaining peaceful interactions with the police. On July 9, 2016, as news that a spontaneous protest was forming to block an interstate highway in Atlanta, @BLMNYC tweeted: “ATLANTA WE SEE YOU. SHUT THAT SHIT DOWN. NO BUSINESS AS USUAL.” Two minutes later, @BLMNYC urged caution by tweeting “#BlackLivesMatter! Keep it peaceful but Stand your ground Atlanta! We will not be stopped.” The findings that BLM activists never incited violence and were more likely to urge their followers to pursue conventional forms of political behavior than disruptive protests during the period between December 1, 2015, and October 31, 2016 provides evidence that indicates we should reject Hypothesis 3.

Further analyses of the tweets that the BLM organizations generated to spur participation in the political system only strengthen the case for rejecting Hypothesis 3. The majority of the tweets containing a call to action urged adherents to engage with the political system by signing petitions to governmental officials (366 tweets), contacting government officials (161 tweets), and voting (136). Together these tweets urging participation in the political system constituted 50% of all calls to action issued by the six SMOs. The Washington, DC area Black Lives Matter chapter (@DMVBlackLivesMatter) composed some excellent examples of these types of calls to action. On March 18, 2016, @DMVBlackLivesMatter retweeted a national petition calling for the firing of a Chicago police officer, Dante Servin, who was charged with manslaughter in the case of 22-year-old Rekia Boyd. In the wake of Terrence Sterling's death at the hands of DC police, @DMVBlackLivesMatter tweeted “Keep calling @MayorBowser at (202)-727-2643 about #TerrenceSterling tell her to release names of the officers and arrest them today.”

Twenty-three percent of the calls to action in the sample (304 tweets) urged people to engage in individual acts of resistance—such as building memorials and signs, taking pledges to support the principles of the BLM movement, praying, etc. On July 13, 2016, the Black Lives Matter organization (@Blklivesmatter) tweeted to urge their followers to pledge solidary with the movement by taking the “Movement for Black Lives Pledge.” The tweet reads: “Every generation is called to define itself. Take the pledge for peace and justice. #M4BLPledge.” On August 8, 2016, the Los Angeles chapter of BLM (@BLM_LA) generated a tweet inviting people to join a “Morning prayer circle at #DecolonizeLACityHall.”

Finally, there were 198 tweets—15% of the tweets containing a call to action—that urged on-line activism or hacktivism. On May 18, 2016, for example, the Los Angeles chapter of Black Lives Matter (@BLM_LA) tweeted: “RT @BLACKlife585: Please read, react and retweet. @ShaunKing @DMVBlackLives @BLMChi @BLMLA @BLMNYC #SayHerName #Justiceforindia #ROC https…” Similarly, on August 2, 2016, the Ferguson Action group (@FergusonAction) tweeted: “Over 2K ppl have endorsed #Vision4BlackLives today. Join us at 3pm EST tmrw for a twitter townhall to talk about it.”

The rejection of Hypothesis 3 does not necessarily mean that the new social movement perspective does not hold validity for understanding the BLM movement. Again, the very fact that there are so few tweets in the sample that urge action is in some ways a characteristic of a new social movement. Moreover, it is plausible that this result is a function of the fact that the data were collected from the six SMOs during the 2016 primaries and general election cycles. As the BLM movement continues to build up its public profile on Twitter, we will be able to glean a more definitive answer to this question through comparative analyses of tweets over multiple election years. These caveats notwithstanding, the finding that BLM groups are more likely to urge their followers to pursue systemic actions over disruptive repertoires of contention suggests that the activists who are crafting the messages and frames that drive the BLM movement have not completely given up on the U.S. political system.

CONCLUSIONS

The BLM movement was born on Twitter when Patrice Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi created #BlackLivesMatter to express their grief and outrage over George Zimmerman's acquittal in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin. Over the past 4 years, the movement has morphed into a vital, multi-issue social movement in African American communities across the United States (Harris Reference Harris2015; Rickford Reference Rickford2016; Taylor Reference Taylor2016). As previous researchers have demonstrated (Cox Reference Cox2017; Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Ince, Rojas, and Davis Reference Ince, Rojas and Davis2017), Twitter has been an indispensable tool for BLM activists as they work to build their movement. Most extant studies have highlighted the role that hashtags play in forming dialogs between core BLM activists and their adherents. These studies have led to considerable gains in our knowledge by demonstrating how these dialogs have boosted the movement's ability to disseminate information and mobilize supporters for protest actions (Cox Reference Cox2017; Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark Reference Freelon, McIlwain and Clark2016; Ince, Rojas, and Davis Reference Ince, Rojas and Davis2017).

Despite their profound contributions to theory building, the hashtag studies do not allow us to make distinctions between the communications originating from the BLM movement's core activists, who ostensibly have control over the movement's strategy and messaging, and rank-and-file protestors and bystanders. This means that it is impossible to analyze the behaviors of the core activists as they attempt to build the movement. This situation, in turn, leaves us in the position of being unable to make firm judgments about the dynamics of the BLM movement. This paper has advanced the position that focusing exclusively on the tweets generated by the SMOs helps to resolve these dilemmas.

The results of the three content analysis studies presented in this paper leave us in a stronger position to understand the BLM movement. The findings from Study 1 that the vast majority of tweets generated by the six SMOs examined in this study are expressive in nature certainly lends credibility to the conventional wisdom that BLM is best understood as a New Social Movement. The results of Study 2, which examined the frames deployed by the SMOs, were not as definitive. While 33% of the frames used to talk about the movement made a reference to gender, LGBTQ, racial identities, or cultural issues, most tweets in the sample used a liberal frame focused on individual rights. This finding does not necessarily cut against the interpretation of BLM as a New Social Movement, but it does illustrate that the movement's core activists take a broader approach to talking about their movement than just “centering” the identities of the most marginal segments of the African American community.

The results of Study 3 present the strongest challenge to the classification of BLM as a New Social Movement. Again, this study found that only 12% of the SMOs' tweets issued a call for immediate action that urged followers to engage in disruptive protest activities. Moreover, the vast majority of tweets in this subset of the sample (88%) urged the pursuit of actions through the existing political system. Together these findings present a very different narrative of the BLM movement than what is portrayed in academic writings, media accounts, and by the core activists themselves. Indeed, the results of this study suggest that BLM groups do value the political process and are willing to mobilize their followers to pursue outcomes within it. Moreover, the fact that there was not one tweet among the 18,078 examined advocated violence provides a significant challenge to the argument that the movement incites attacks upon law enforcement officers.

While, at first glance, these findings suggest that BLM is something of a hybrid movement that sometimes resembles a new social movement and sometimes engages in traditional resource mobilization, we must be cautious not to overstate the meaning of these findings for two reasons. First, as we have seen, the number of tweets produced by the SMOs that exhort their followers to action is an incredibly small subset of the overall sample. Second, the fact that data for this study were collected at the height of the 2016 primary and general elections in the United States may have encouraged the BLM groups to generate more tweets about mainstream politics than they would do in a non-election year. Subsequent studies will be required to truly get a handle on this issue. For now, it is sufficient to say that, by judging all of this evidence in context, the SMOs examined in this study are building a movement that is focused much more on expressive communication than strategic communication aimed at mobilizing resources and negotiating directly with the elites who control the levers of power that are making African Americans vulnerable to police brutality and other forms of predation.

Contrary to the viewpoints expressed by the movement's critics, the fact that the BLM movement pursues expressive communication more often than strategic communication does not limit its potential to have a long-term impact on African American communities and American politics. As we have seen, even without issuing explicit calls to action, BLM organizations have been able to foment large and enduring protests in dozens of American cities since 2013. These protests are clearly a response to the expressive and informational content that BLM activists deliver to their followers. This reality provides further evidence in support of social movement scholars who have argued over the past two decades that emotional appeals hold great potential to generate protest activities and, as a result of this reality, we should dispense with the artificial distinction between expressive and strategic behavior (Jasper Reference Jasper2018; Polletta and Amenta Reference Polletta, Amenta, Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2001).