INTRODUCTION

Health care professionals are often deemed to be reflective in their practice; that is, they are actively engaged in recalling and critically evaluating events and experiences to understand what might be done differently. The reality is, although health care professionals are aware of the concept of reflection and reflective practice, they do not always engage in it actively or effectivelyReference Newnham1. In health care settings such as the Radiation Medicine Program (RMP) at Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto, evidencing reflection is viewed as a desirable method of documenting clinical experience and a key component to the development of professional portfolios. Portfolios have been adopted by RMP to help radiation therapists plan, implement, evaluate and showcase continuing professional development (CPD) activities to help develop clinical career pathways and encourage personal development planning2. Reflective practice documentation is strongly suggested for the portfolio as evidence of learning. However, RMP radiation therapists may not consciously engage in reflective practice or be performing it effectively. In addition, even if they are doing it regularly and effectively, they may not know how to evidence it. This article discusses the results of an evaluation of a series of workshops developed in RMP to assist practitioners in acquiring new skills to undertake and evidence reflection in their practice.

BACKGROUND

At the core of the reflective process is the acquiring of new understanding and appreciation, reframing problems and the development of knowledge creation capacitiesReference Smith3. These three core outcomes are obtained through the conscious act of thinking about past events, attending to the feelings and ideas that arise from those events and visualizing the resultant changeReference Williams and Lowes4. These actions are echoed in Kolb’s theory of experiential learning. Both processes involve observing a situation, realizing that one is in a situation, thinking about it and then making decisions about what to do nextReference Burnard5–Reference Donaghy and Morss7. They are all essential steps in the learning processReference Braine8.

Reflection is also an important component to critical thinking. A practitioner who is self-aware and reflective in their work is more likely to be able to develop good critical self-appraisal and clinical reasoning skillsReference Donaghy and Morss7,Reference Hargreaves9Reference McGrath and Higgins10. They would be able to engage in continual evaluation of their professional practice, critically analyzing and developing it furtherReference Wilson11–Reference Lyons14 and be able to narrow the theory–practice gap by reflecting on their experienceReference Donaghy and Morss7,Reference Hargreaves9,Reference Wilson11,Reference Lyons14–Reference Graham17. This would lead to practitioners developing greater self-awareness, confidence and understandingReference Newnham1,Reference Hargreaves9,Reference Paget13–Reference Manning, Cronin, Monaghan and Rawlings-Anderson16. Structured reflective learning activities could assist practitioners to appreciate their practice knowledge and understand and value their experiences more fully. It can empower practitioners to own their knowledge, contribute more fullyReference Newnham1,Reference Martin and Mitchell18, and thus impact positively on changing clinical practiceReference Paget13,Reference Duffy19.

The value in reflection and being reflective in practice is apparent. The question then becomes, is evidencing reflection necessary?

Increasingly many health care professions include evidencing reflection as a requirement of undergraduate studies. Reflection may also be needed for initial professional certification and continued professional registrationReference Braine8,Reference Hargreaves9,Reference Mallik20,Reference Cashell21. Reflection is also being increasingly used as a means of ensuring competenceReference Manning, Cronin, Monaghan and Rawlings-Anderson16. The undergraduate program in the Medical Radiation Sciences (MRS) at the University of Toronto/Michener Institute embeds the development of reflection and reflective journaling skills into their clinical practicum courses22. It is a key component of the first clinical practicum and is further encouraged in the clinical simulation semester and the Year 3 clinical practicum in the form of electronic portfolio entries. The Canadian Association of Medical Radiation Technologists (CAMRT) identifies “engaging in reflective practice, and self-assessment to identify a learning plan that will promote best practices” as a requirement for entry into practice23. The CAMRT Competency Profile for Radiation Therapy further elaborates that an entry-level radiation therapists requires critical thinking skills in order to “. . . assess, adapt, modify, analyze and evaluate in a variety of situations and environments”23. The College of Medical Radiation Technologists of Ontario also encourages the development and use of reflection and reflective practice skills in the maintenance and completion of the quality assurance program, which is an annual requirement for medical radiation technologists (MRT) to practice in Ontario24.

Reflective practice can lead to professional developmentReference Donaghy and Morss7,Reference Hargreaves9,Reference Duffy19,Reference Williams and Walker25 and the acquiring of practice knowledgeReference Wilson11,Reference Lyons14. It is the ability to access, make sense of, and learn through work experience to achieve a more desirable, effective and satisfying workReference Newnham1. Yet, many professionals find reflective practice confusing and are unsure of how to proceedReference Wilson11. In an attempt to lessen this barrier and support practitioners with evidencing their expertise, knowledge and growth, a course on reflection and reflective practice was developed, implemented and delivered. Such a course could potentially supplement any gaps in reflective knowledge, encourage reflection in the workplace, and propose tools and methods for evidencing practice knowledge and experience for the professional portfolio.

METHODOLOGY

Developing the reflective practice course

The Reflective Practice Course (RPC) was developed as a three-part foundational and interactive course to introduce and encourage reflective practice within the clinical setting. Each part was designed to be delivered within a 50-60 min time frame, ideally during lunch, over a 1-to-2-week period. The overall course goals were as follows:

1. To improve the ability to perform structured reflection and develop reflective practice skills

2. To assist with career development and professional portfolio reflective entries

3. To develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills

4. To provide therapists who teach with tools to increase engagement with learners and other colleagues

5. To assist in the transfer of skills, knowledge and providing feedback.

Course content

An extensive review of the literature established the framework for the content of the RPC. The first part of the RPC provided the theoretical understanding of reflection and reflective practice. It included definitions, benefits and the difficulties encountered in its application. From the literature, it was difficult to identify a single definition for reflection and reflective practice. Thus, a few definitions were provided as a means to demonstrate the complexity and lack of clarity in the concept of reflectionReference Williams and Lowes4,Reference Donaghy and Morss7,Reference Lyons14,Reference Cotton15,Reference Atkins and Murphy26 as well as the variability in its application. The role of reflection in learning was highlighted through a review of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory. This lead to the establishment of the various modes of reflecting: anticipatory (reflection-before-actionReference Greenwood27), in-action and on-actionReference Schon28. Finally, the benefits and barriers to reflection were discussed and further supported by a review of Cashell’s studyReference Cashell21, which was conducted in RMP, investigating radiation therapists’ perspectives of the role of reflection in clinical practice.

The second part titled “How to personally achieve reflective practice”, presented various models of reflection, elaborated on stages in the reflective process and provided non-discipline- and discipline-specific tools for the development and promotion of reflective practice skills. The variety of models discussed was intended to provide participants with the opportunity to connect to a model that best fit their individual way of knowing and reflecting. Although, it was emphasized to participants that neither were they limited to the use of a single model nor was it necessary to use one at all. The final component of the second session was to review methods to promote critical analysis and perform structured and non-structured written reflections. Individual and group exercises exploring the reflective splurgeReference Bolton29 were performed and templates and samples of learning logs, portfolio and journal entries were provided.

The third part of the RPC was titled “Reflective practice sharing and understanding”. It provided participants with information on the purpose and benefit of guided reflective conversations, the role of the facilitator, barriers encountered and included activities to establish trust and perform guided reflective conversations with each other as colleagues and with their students. Figure 1 summarizes the key components of the RPC curriculum.

Figure 1. Reflective Practice Curriculum

Study population

The 17 graduates of a Clinical Preceptorship Certificate CourseReference Bolderston, Palmer, Feuz and Tan30 were solicited to participate in the piloting of the RPC. Preceptors were identified as ideal candidates for the pilot group due to their introductory understanding of adult education theories and principles and their expressed interest in teaching and learning. Eight participants were anticipated, which represented approximately 50% of the eligible participant pool. As well, eight participants were viewed as a good sample size as it also represented a group size small enough to ensure and encourage full reflective engagementReference McGrath and Higgins10,Reference Manning, Cronin, Monaghan and Rawlings-Anderson16.

Data collection and analysis

An email outlining the purpose, time commitments and anticipated outcomes for enrollment in the RPC was sent to the eligible study participants. A consent form was attached to the email for review. Interested participants were requested to email their interest and any questions or concerns. All questions and concerns were addressed and those who agreed to participate were asked to sign a consent form. Participation was entirely voluntary and the participants were aware that they could withdraw at any time without consequences.

The Research Ethics Board approved 10-question survey was administered to the participants 1 week prior to the start of the RPC to assess the participants initial knowledge and understanding and use of reflection and reflective practice. A second survey consisting of the eight core questions was completed immediately at the end of the third part of the RPC. The third survey, identical to the second, was completed 3 months post-completion of the RPC. The intent of the post-surveys (immediately post-RPC and 3 months post-RPC) was to assess frequency of use and comfort level with using reflection. The surveys were all administered, completed and collected online through Survey Monkey®. Confidentiality and anonymity was maintained throughout the survey administration and data collection. The pre-, post- and 3 months post-surveys were analyzed individually and in comparison with each other. Corresponding items in each questionnaire were cross-compared to observe trends and changes.

Ethics

Ethics approval was sought and obtained from the authors’ institution’s Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

Eight preceptors expressed interest and consent was given for participation in the RPC. The eight consenting participants completed the first workshop, after which two participants withdrew due to other obligations. One participant withdrew after the second workshop. In total, five participants completed all three workshops. Four of the five survey respondents are female.

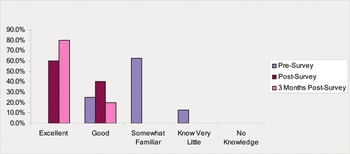

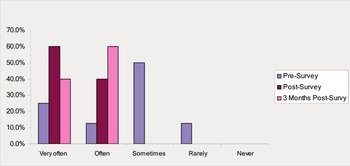

The pre-survey was completed by the initial eight participants, and the post-survey and 3 months post-survey were completed by five of the remaining participants. All three surveys had four common questions: one open-ended question for comments and three demographics questions. The results of the four common questions were compared with each other and are displayed in the following graphs.

The first question attempted to assess the preceptors understanding of reflection and reflective practice. Prior to the workshop, the majority of participants, 75%, indicated that they were “somewhat familiar” or had “good” knowledge. Only one participant identified that they “know very little”. The post-survey indicated that all participants’ knowledge had improved to “good” or “excellent”. This level of knowledge was slightly improved on the 3 months post-survey (Graph 1).

Prior to participation within the RPC, four of the participants indicated that they “sometimes” reflected on their practice with one indicating “rarely”. The remaining three participants indicated “often” or “very often”, which equates to 37.5% of reflecting on practice being equal to or greater than “often”. After completion of the RPC, 60% of the participants indicated that they plan to reflect “very often” on their practice and 40% indicated “often”. That is, 100% of all participants plan to reflect on practice at a level of “often” or greater. The overall post-RPC frequency rate of reflection on practice was maintained at 3 months, as can be seen in Graph 2.

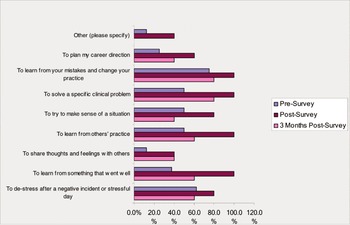

Graph 3 highlights the various scenarios in which participants frequently reflect. Participants were asked to check all categories in which they reflect. The pre-RPC results indicate that the reason to most often reflect, at 75%, was “to learn from your mistakes and change your practice”. The post-survey results demonstrate a marked increased in all categories, with four categories receiving 100%. In addition, when comparing the post- and 3 months post-results, there is a slight decrease in frequency at 3 months in all categories. However, the overall frequency in each category at 3 months remains greater than at the pre-survey level.

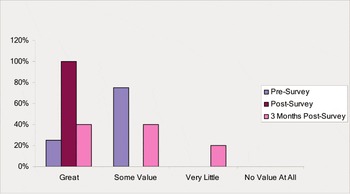

Participants were also asked to rank their perceived value in learning how to reflect and applying reflection in practice (see Graph 4). Prior to the survey, the majority of participants (80%) saw “some value” in learning how to reflect and applying it in practice, with 25% indicating “great” value. At the completion of the RPC, 100% of all participants identified that they saw “great” value in reflection. However, at 3 months after completion of the RPC, only 40% indicated “great” value, an equivalent 40% saw “some value” and one participant indicated “very little”.

Of the five participants that completed all three surveys, three participants had 11 years of experience or greater and the remaining two had less than 6 years of experience. The two participants with less than 6 years of experience had previous exposure to reflective exercises and formal training through the undergraduate MRS program. Neither did having greater length of service influence positively towards reflective practice engagement nor did a lack of service have a negative impact. In addition, all five responders had a baccalaureate degree. No correlation was observed regarding a high ‘level’ of academic achievement positively influencing reflective practice.

Limitations

Limitations of the study are principally due to the small sample size. The five participants represent 29% of the identified eligible participant population. The responses provided by the small sample size may not necessarily be representative of the larger practitioner population.

The voluntary nature of this study would anticipate that those individuals open to reflection would agree to participate and provide responses. In addition, four of the five participants are female. The disparity in gender, however, corresponds to the typical gender demographics of the radiation therapy profession. However, the characteristics most typically associated with women (openness, willingness to share and a readiness to accept new ideas) are also the characteristics most conducive to engaging in reflectionReference Newnham1. Thus, there may already exist a predisposition for the female participants to engage in reflection.

DISCUSSION

There are many reasons for engaging in reflective practice. Practitioners may be asked to impart their knowledge to students and professional colleaguesReference Newnham1, participate in continued professional development activitiesReference Newnham1,Reference Williams and Walker25 or view it as a means to make sense of the world around themReference Pfund, Dawson, Francis and Rees31. Reflection can be used as a means to handle emotionally challenging situationsReference Williams and Lowes4,Reference Pfund, Dawson, Francis and Rees31. It can assist students and practitioners to recognize their strengths, application of knowledge and understand their own feelingsReference Pfund, Dawson, Francis and Rees31. It is through this process of reflection that they will be able to build confidence for future practice, transfer knowledge contextually and thereby improving practiceReference Wilson11–Reference Paget13,Reference Pfund, Dawson, Francis and Rees31.

Participation in a professional development workshop such as the RPC, which provides key reflective concepts and applicable tools to start the reflective process, is a good vehicle for promoting reflectionReference Donaghy and Morss7,Reference Braine8,Reference McGrath and Higgins10. The results from all three surveys indicate that with knowledge and skills training in reflection and reflective practice, participants’ understanding and knowledge regarding how to reflect and thus their application of reflection in/on practice can be improved upon. As well, the gain in the knowledge and skill has an immediate positive impact on the frequency of reflecting on practice. However, sustainability of the reflective practice skills at 3 months, although improved when assessed against the pre-RPC, did decline when compared with immediately after completion of the RPC. The sustainability may be impacted by the perceived value of reflection and applying it into practice.

Prior to the RPC, 25% of preceptors saw “great” value in learning how to reflect and being able to apply reflection in practice. After completion of the RPC, 100% of all preceptors saw “great” value in reflection and reflective practice. The positive shift in value may be primarily due to the RPC’s emphasis that all practitioners are reflective; however, they may not be aware that they are doing itReference Newnham1. This notion was supported with examples of common scenarios that practitioners often encounter and the thoughts they experience, which are examples of informal reflection taking place. Acknowledging that reflective thoughts and discussions do occur and are of significant value may have been the precursor to acceptance and shifting on the value of reflective practice.

Another key component to the positive shift to valuing reflection and reflective practice may have been the identification of methods and tools for translating reflective thoughts and discussions into formal documents of reflections. By establishing the need for reflective documentation for such activities as proof of professional development, professional portfolios, career development, continuing education and so forth, appropriate tools (learning logs, journaling/diaries, critical incident, questioning skills) were identified and methods for their completion were suggested. Providing the tools and instructions allowed participants to more easily complete the reflection, evidence their practice and visualize its impact on their professional careers.

The continued use of reflection is more likely when reflection is valued and the practitioner possesses awareness, motivation and the ability to use reflectionReference Lowe, Rappolt, Jaglal and Macdonald32. The RPC attempted to address improving awareness (knowledge and understanding) and ability (methods and tools) to use reflection through the delivery of the curricular content. However, motivation or the external demonstration of valuing is difficult to foster in others. Although the RPC attempted to foster reflection in practice by providing the knowledge and tools needed, there is no guarantee that it will continue to develop or even be maintained. In addition, the likelihood of reflection in use is further increased if the clinical processes and practice context are conducive to the use of reflectionReference Martin and Mitchell18,Reference Lowe, Rappolt, Jaglal and Macdonald32.

The decline in reflective value at 3 months post-RPC indicates that the knowledge transfer may not have been sufficient to sustain the positive shift in values. When barriers to reflection begin to surface, a transition to previous practice re-emerges. This often has the potential to be habitual and lacking a perceived need for reflection. This repetitive state of practice has been described by Chapman et al. as a ‘non-learning’ situationReference Chapman and Dempsey33. Thus, it is important that support and opportunity are provided in addition to reflective knowledge, if ongoing reflection is to be achieved. The support provided can be varied and may include the support of others, colleagues, supervisors, the workplace, time, and so onReference Braine8,Reference Paget13,Reference Martin and Mitchell18,Reference Mallik20.

Reflecting on one’s practice involves a level of emotional vulnerability that not all practitioners are comfortable encountering. Issues such as trust, comfort, safety and support all exert influences on the degree to which an individual feels prepared to disclose their thoughts and feelings of a particular experienceReference Durgahee34,Reference Williams and Walker25. Providing a safe environment where trust has been established is vital to encouraging reflection and the sharing of reflection through reflective dialogueReference Durgahee34. At 3 months after the completion of the RPC, the safe environment that was created within the course and with the participants may no longer exist. Without the support, encouragement and safety of the RPC group and the facilitator/guide, the participants perhaps began to lose value in reflecting and sharing their reflections. As well, the valuing of personal experiences, which is paramount to reflection and plays a role in self-development and emancipation, may begin to diminishReference Graham17,Reference Martin and Mitchell18,Reference Williams and Walker25.

Qualified staff may have difficulties in accessing support for their reflection on actionReference Williams and Lowes4. Barriers are mostly institutional and include such things as a lack of readiness to embrace reflective practice and its implicationsReference Paget13. Andrews et al. believe that reflection needs to be supported by managers and incorporated into work life if individuals are expected to show continued commitment to the processReference Williams and Lowes4,Reference Findlay and Dempsey35. As well, practitioners have expressed concerns regarding their abilities to use it in their practice because of barriers such as workload demandsReference Lowe, Rappolt, Jaglal and Macdonald32 and limited time to engageReference Braine8. Institutional support plays a major role in the continuation and valuation of reflective practice.

Practitioners may be keen to reflect on practice when supported and compelled to by requirements of a course or workshop, by their colleagues, peers, supervisors or their governing college but may demonstrate little incentive when there is no recognition. The lack of support and encouragement (recognition and acknowledgement) from the workplace can greatly impact the motivation to initiate and continue with reflective practiceReference Martin and Mitchell18,Reference Cashell21. As well, some aspects of clinical and practice knowledge are difficult to articulate. This difficulty can act as a hindrance to seeking opportunities for reflection or sharing reflective thoughts and ideas. In addition, due to the highly personal and individual nature of reflectionReference Martin and Mitchell18,Reference Chapman and Dempsey33,Reference Durgahee34, it is often perceived as uncomfortable to perform. It has the potential to be emotionally exposing and threateningReference Cotton15,Reference Manning, Cronin, Monaghan and Rawlings-Anderson16,Reference Duffy19,Reference Pfund, Dawson, Francis and Rees31. Thus, support is needed to initiate and promote the continuation of reflection in practice.

CONCLUSION

The adoption of reflection as a process and tool for learning is apparent throughout the literature. However, the variety of definitions, models and tools for reflection are many and multi-facetted that it can often make a simple concept rather confusing. With the demands of undergraduate education, professional governing bodies and the workplace requiring the evidencing of reflection and reflective practice, it was determined there was a need to formally develop, implement and deliver a course on reflection and reflective practice. The RPC attempted to meet those demands.

Participation in a reflective practice professional development workshop, such as the RPC, can improve knowledge and understanding of reflection and reflective practice. It can also provide participants with the tools and skills necessary to actively engage in reflection. However, the path and time to mastery can vary from individual to individual. The RPC has provided an initial framework for a formal and practical introduction of reflection and reflective practice concepts. Future plans are to offer the RPC as a secondary workshop to graduates of the Clinical Preceptorship Certificate CourseReference Bolderston, Palmer, Feuz and Tan30. In the mean time, structured reflection should be integrated into institutionally endorsed CPD as a means to give learners time to reflect on their learning priorities as well as encourage the enhancement and maintenance of reflective practice skills in the clinical environmentReference Chapman and Dempsey33. Institutional support should be demonstrated through the endorsement and time to complete reflective activities and should be incorporated into CPD programs.

Knowledge of the various models and tools for reflection is helpful and is a great starting point; however, it is not enough. For sustainability of the reflective skills outside of the professional development scenario, the reflective knowledge must be accompanied by appropriate ongoing institutional support and opportunity to encourage its continuation. As well, value in the concept and process of reflection must be at the appropriate level in order to foster the seeking of opportunities for deep reflection.