The role that perspective taking plays in social and personal relationships has been extensively examined in relation to the attributions we make for others’ behaviour (Regan & Totten, Reference Regan and Totten1975), helping (Batson, Reference Batson1991), romantic relationship satisfaction (Davis & Oathout, Reference Davis and Oathout1987), and, more recently, anger, aggression, and anti-social behaviour (Day, Mohr, Howells, Gerace, & Lim, Reference Day, Mohr, Howells, Gerace and Lim2012). The ability to perspective take has also been associated with positive psychotherapeutic outcomes (Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, & Watson, Reference Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, Watson and Norcross2002), and is consistently identified as one of the foundations of a therapeutic relationship (Rogers, Reference Rogers1957). Yet, despite extensive consideration of the role that perspective taking plays in achieving important social outcomes, the process by which people take another's perspective has received comparatively little attention. Indeed, Dymond suggested as long ago as the late 1940s that regardless of the accepted ‘importance of the empathic process, there has been little or no systematic work done on the process itself’ (1949, p. 127). More than 50 years later, Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Soderlund, Cole, Gadol, Kute, Myers and Weihing2004) posed a similar question: ‘How does perspective taking work? That is, when we try to imagine another's point of view, what steps do we take to accomplish this goal?’, concluding that ‘surprisingly little work has directly addressed this issue’ (p. 1625). This article reports the findings of a study that investigates what it is that an individual does to apprehend the thoughts, feelings, and meaning of behaviours of another person during an interaction. First, however, it is important to establish where perspective taking fits into the empathy experience.

Davis’ Model of Empathy

Within the psychological literature, perspective taking is considered to be a main component of the broader construct of empathy. Dymond (Reference Dymond1950) defined empathy as ‘the imaginative transposing of oneself into the thinking, feeling, and acting of another’ (p. 343), while Davis (Reference Davis1983) subsequently specifically described perspective taking as ‘the tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological point of view of others’ (pp. 113–114). The similarity in these definitions reflects the use in the psychological literature of the term ‘empathy’ to refer to cognitive processes (as Dymond does), although, as will be seen, others have focused on affect in their definitions (e.g., Mehrabian & Epstein, Reference Mehrabian and Epstein1972). The model proposed by Davis (Reference Davis1994) is useful in terms of understanding how perspective taking is related to the wider concept of empathy, and where gaps exist in our understanding of the process.

The first component in his model involves the antecedents to a person taking the perspective of another or experiencing an empathic emotional response. These include the empathiser's dispositional tendencies for perspective taking, aspects of the situation (such as its emotional valence), and similarity between the empathiser and target. The second part of the model addresses the processes in which an empathiser might engage, which can be understood in terms of levels of cognitive activity from noncognitive processes (e.g., the primary circular reaction in infants and motor mimicry), simple cognitive processes (e.g., classical conditioning and direct association), and advanced cognitive processes (e.g., language-mediated associations and perspective taking). This conceptualisation draws on the work of Hoffman (Reference Hoffman, Lewis and Rosenblum1978) and others, where imagining oneself in the other's place is theorised to demand higher levels of perceptual and cognitive performance, making it a more voluntary process than mimicry, reflexive crying and some forms of conditioning.

According to Davis (Reference Davis1994), the empathic process results in the individual experiencing both intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes, the remaining two components in the model. Intrapersonal outcomes may include affective responses that are subdivided into parallel outcomes (where the empathiser experiences the same or quite similar affect to the target), and reactive outcomes (where the empathiser experiences affect that is a response to the target, but is not necessarily the same or similar to that of the target). These outcomes can be understood as what is often referred to as emotional empathy. The notion of sympathy, defined by Wispé (Reference Wispé1986) as ‘the heightened awareness of the suffering of another person as something to be alleviated’ (p. 318), fits here, as does empathic anger (anger toward an offender for a victim's plight; see Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1990). Non-affective outcomes are also included, and comprise of attributions as well as accuracy in inferences about the target's perspective. Altruism, (inhibition of) aggression, and other behaviours that are social in nature are identified as potential interpersonal outcomes.

The Process of Perspective Taking

Much of what is known about the perspective-taking process comes from studies that require the participant to consider the experience of an experimental target, with the outcomes of this process typically the major focus of investigation. For example, studies of altruism (see Batson, Reference Batson1991, Reference Batson2011), which focus on understanding the link between emotional empathic response and helping behaviours, begin by instructing participants to consider another's point of view. The main problem with this methodology is that it provides more information on the outcomes of the process than on what the participant is doing to apprehend the other's perspective.

The nature of an induction also appears to influence outcomes. In particular, asking a participant to imagine how another person is feeling in a situation in which he or she has found him- or herself (often referred to as an imagine-other condition) has been shown to lead to different physiological reactions (Stotland, Reference Stotland and Berkowitz1969), empathic emotion, personal distress, and moral behaviour (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Lishner, Carpenter, Dulin, Harjusola-Webb, Stocks and Sampat2003; Batson, Early, & Salvarani, Reference Batson, Early and Salvarani1997) than when the participant imagines him- or herself in that situation (imagine-self). Indeed, even when an empathy induction attempts to direct a perspective-taking effort, participants report that being exposed to another's situation can lead to both a self and other focus, although the level of focus is often weighted in the direction of the induction (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Early and Salvarani1997; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Soderlund, Cole, Gadol, Kute, Myers and Weihing2004). This would suggest that multiple strategies are used to accomplish perspective taking, and that broad instructions to take another's perspective from a particular vantage point (self versus other) fail to capture the complexity of the resulting process.

More recently, researchers have focused on process-explanations of perspective taking through an examination of the use of the self in taking another's point of view. Studies in this area have revealed that people make predictions about another's thoughts and behaviour in a way that suggests a process of effortful adjustment from one's own initial perspective (Epley, Keysar, Van Boven, & Gilovich Reference Epley, Keysar, Boven and Gilovich2004); and that imagining one's own feelings in a vignette character's situation in order to make inferences about that character's thoughts and feelings is a common strategy (Van Boven & Loewenstein, Reference Boven and Loewenstein2003). Davis, Conklin, Smith, and Luce (Reference Davis, Conklin, Smith and Luce1996) suggested that in the process of taking another's perspective the person's mental representations of self and target become more similar.

In a study utilising an excerpt from a talk show, Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Soderlund, Cole, Gadol, Kute, Myers and Weihing2004) found that self-related thoughts and feelings (e.g., judgments of similarity), as well as thoughts and feelings that are target-related (e.g., sympathy) and attempts to distance from the person in the video (e.g., judgement of dissimilarity) were associated with the perspective-taking process. In another qualitative study, Håkansson and Montgomery (Reference Håkansson and Montgomery2003) asked participants to describe a real-life empathy experience (their central focus was not perspective taking), and found support for four hypothesised components of the experience: understanding, emotion, perceived similarity, and action/concern for the wellbeing of the other person. Finally, a phenomenological study by Kerem, Fishman, and Josselson (Reference Kerem, Fishman and Josselson2001) found that cognitive components of empathy, such as perspective taking, were more often reported in a way that was easy to discern (as well as often being reported separately, in comparison to affect-related concepts, which it was suggested were often reported with cognitive-related components). These researchers stressed that this may be related to problems in articulating the complex emotions and affect involved in empathic situations. As such, perspective taking may comprise a number of processes, strategies, and cognitive and emotional content.

The work carried out thus far has revealed some of the ways that perspective taking may operate (e.g., adjusting from one's own perspective), but consideration of processes or strategies used has often been conducted in isolation and without consideration of the wider empathy experience. Basic research is therefore needed to elaborate on the perspective-taking component of Davis’ (Reference Davis1994) model. The purpose of the present exploratory study was to examine the ways in which individuals attempt to take the perspective of others during an interpersonal interaction. We chose to focus on attempts to perspective take rather than times, for example, when perspective taking did not occur. This is in order to highlight factors that influence perspective taking, relationships with empathic outcomes, as well as difficulties or unempathic behaviours that can result even when a person is attempting to consider the thoughts, feelings, and behaviours of another person.

Method

Participants

Twelve participants (five male, seven female) were recruited for participation in the study. The mean age of participants was 31.42 years (SD = 12.89; Range = 20–52 years). Six participants worked within administration and clerical positions, two were full-time university students, one worked within each of retail, education, and the military, and one was not in paid employment.

Materials

Induction to recall a perspective-taking experience

The perspective-taking induction presented a definition of perspective taking (similar to that provided by Dymond, Reference Dymond1949, Reference Dymond1950), and asked the participant to choose a previous situation in which they had taken the perspective of another person. The induction, presented below, drew on those used in previous empathy research (e.g., Batson et al., Reference Batson, Early and Salvarani1997; Stotland, Reference Stotland and Berkowitz1969) and broader visualisation inductions (e.g., McCullough, Worthington, & Rachal, Reference McCullough, Worthington and Rachal1997), but did not advocate a particular method (e.g., imaging self in the other's place).

Every day we interact with a number of different people in a variety of situations. Often in these situations we try to imagine or understand the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of another person by attempting to take their perspective.

Perspective taking is when we try to take the point of view of another person, attempting to interpret their thoughts, feelings, and actions ‘through their eyes’ or ‘from their perspective’.

I would like you to think of a time when you tried to take the perspective of another person. For a minute, try to remember and focus on this time, focus on the other person involved, and focus on yourself. Try to picture the situation in your mind, and recollect what was involved and what had occurred. Also, try to remember how you took the perspective of the other person, what your thoughts and feelings regarding the other person were while perspective taking, as well as the thoughts and feelings you had afterwards.

Interview protocol

The antecedent-process-outcome framework of Davis (Reference Davis1994) was used to guide participants through reflection on the experience. The protocol began with a question asking participants to describe briefly the situation reflected upon after the induction. Follow-up questions asked participants to reflect on the perspective-taking process: ‘Can you tell me what you did in order to imagine what the other person was thinking and feeling?’ or ‘Describe some of the processes and strategies you used to imagine what the other person was thinking and feeling’ (the latter adapted from Van Boven & Loewenstein, Reference Boven and Loewenstein2003). Other questions focused on the thoughts and feelings which participants believed the other to be experiencing (e.g., ‘While you were involved in this situation (so not looking back now), what did you think the other person was thinking/feeling?’), what the participant felt and thought (e.g., ‘. . . do you remember what you were thinking and feeling [what was going through your mind] while you were imagining the other person's perspective?’) and the behaviours of participants in the situation.

Participants were also asked to reflect on the outcomes of the situation (‘What happened after your interaction with the other person?’ and ‘. . .were you happy with the way it went?’); the ease with which they were able to accomplish the perspective-taking process (e.g., ‘How easy was it to imagine what the other person was thinking and feeling [or to take the other person's perspective]?’); and whether the individual felt they were accurate in inferring the thoughts and feelings of the participant and, if so, why.

Procedure

Participants were read the perspective-taking induction and then given time to think of a relevant situation. It took no longer than 5–10 minutes to select a situation, and no participants reported problems in being able to do this. Once a situation had been selected, participants were guided through the interview protocol. The protocol was adhered to closely in early interviews, with later interviews drawing on patterns that had become apparent during these first interviews (Rubin & Rubin, Reference Rubin and Rubin2005).

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed for analysis. A thematic approach to the analysis was undertaken using a deductive approach (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006), structured around the framework of Davis (Reference Davis1994). The first author took the lead role in analysis. Each transcript was read and re-read, with preliminary notes made and then initial codes attempted. These stages were conducted on printed transcripts and then involved using a word processing program to list transcript extracts under codes. An examination of the codes was undertaken for the purpose of generating higher order themes and subthemes. At all times during this process, the researcher reflected upon and recorded notes on the interpretation of data. The other authors provided feedback on codes and themes through reading a sample of interview transcripts.

Results

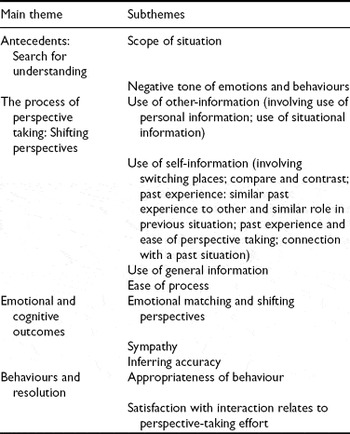

There were several main themes and subthemes identified in the analysis consistent with the framework of Davis (Reference Davis1994): (a) antecedents, (b) processes and strategies, (c) emotional and cognitive outcomes, (d) behaviours and resolution. A dominant theme emerged across parts of the framework: that of shifting perspectives between one's own perspective and experiences and those of another whom the individual was attempting to understand. This overarching theme is discussed throughout the analysis that follows. Table 1 presents a list of main themes and subthemes.

TABLE 1 Main Themes and Subthemes of the Analysis

Antecedents: Search for Understanding

The purpose of taking another's perspective centred on a search for understanding. In some cases, it was an explicitly-mentioned need, and one referred to at length. ‘Michelle’, for example, spoke of the need to understand why her younger daughter became physically aggressive with her older daughter: ‘It was easy to understand that she was feeling upset by the comments from her sister . . . but . . . I couldn't quite work out how she became so aggressive.’ Similarly, ‘Jack’ felt that he needed to understand why his ex-girlfriend was dating someone whom he considered to be an inappropriate choice. Jack's discussion reflected a somewhat explicit and intensive need to understand: ‘And I was trying to figure out why the hell she was with him.’

The theme of search for understanding could be understood as a reflection on the part of participants in terms of their lack of understanding, which then motivated their perspective-taking efforts. ‘Nicholas’ not only took his girlfriend's perspective to understand how she felt when Nicholas told her of his infidelity, but also reflected on a lack of understanding which pervaded much of the relationship: ‘See the thing is I never really understood how she felt about me. So, that's where it was hard for me to understand . . . how upset she was and how angry she was.’

Situations requiring this understanding were varied, and even when a similar event (e.g., wedding) was described, the specifics of this event were quite different across narratives. Participants discussed disagreements with another person (3 participants); witnessing an argument between other people (2); wedding planning and interaction with the bride and/or groom (2); interactions in a work setting (workplace, band rehearsal) (2); intimate relationships (2); and a family bereavement (1). In all cases except the workplace situation, the event involved an already-existing acquaintance. There was a mix of one-off or more isolated events, or those which fitted within a wider experience narrative (scope of situation). For example, the death of ‘Daniel's’ grandmother was a more specific event, while ‘Brooke's’ discord with a sibling was of a more continuing nature.

The behaviours and emotions involved tended to have a negative tone, including anger, frustration, upset/sadness, and confusion. Nine narratives involved some sort of argument or altercation. More positively toned emotions were discussed, but were often not the focus of the perspective-taking effort. ‘Joshua’, for example, referred to the happiness and appreciation of another band member working extensively on a song, but it was the frustration felt by the band at having to do this that was the focus of his narrative. Similarly, while ‘Laura’ discussed the hopes, dreams and plans of her soon-to-be-married daughter, much of the narrative concerned nervousness and overwork in planning the wedding.

The Process of Perspective Taking: Shifting Perspectives

The process of perspective taking involved a shift between self and other: a core theme labelled shifting perspectives. This was not a linear shift from one's own perspective to that of the other (with the other's perspective the ‘end point’). Instead, it reflected the use of information about the self and information about the other person simultaneously or alternately. The theme, therefore, involved the participant holding or considering both their own perspective and the other's perspective. ‘Cameron’ referred at length to the differences in perspective that he and his customer held: ‘I was trying to see it from her point of view . . . why she was annoyed . . . but I was also seeing it from my point of view ‘cause . . . I knew the facts why we didn't have it.’

Daniel discussed trying to understand how his mother felt on their death of her mother, providing a metaphor for this process: ‘I think . . . it was a bit of a sort of a fight between what I was thinking and what I was drawing from my parents.’ In some cases, the juxtaposition was not always so explicitly referred to, although this idea of struggle was similarly reflected upon. Brooke referred to a struggle in attempting to understand her sister's perspective, but also referred to her sister's inability in this regard: ‘I don't think she understood . . . how upset I was about the situation.’ Brooke's struggle also involved difficulty in reconciling information about herself and information about her sibling (their differing levels of social interaction) when she attempted to ‘imagine myself in her shoes’. Many of these and the other narratives reflect an appreciation or understanding of the other's perspective, although not necessarily a taking on of this perspective: ‘After I'd done that I still had . . . my negative perspective that she was just being lazy, I hadn't actually taken on the reasons that she had’ (‘Natasha’).

Although some participants referred to one particular method for taking the other's perspective, many tended to suggest that there were a number of ways in which they attempted to understand or apprehend the perspective of the other. There were three main themes identified — (a) use of other-information, (b) use of self-information, and (c) use of general information — as well as a theme regarding ease of the processes and strategies used to take the other's perspective (ease of process).

Use of other-information

The theme use of other-information consisted of two subthemes: use of personal information (e.g., knowledge of the other's traits and predominant ways of behaving) and use of situational information (contextual elements of the other's situation). Nicholas thought that an emotional reaction on the part of his girlfriend in the specific situation was a somewhat predicable occurrence: ‘I thought that was quite normal for her.’ He also spoke of the context of their relationship prior to Nicholas telling her of the infidelity. Jack also provided a context to his ex-girlfriend's behaviour:

. . . she'd had a lot of problems with guys and being screwed around . . . a lot, so I was thinking about her background and . . . trying to understand that way, I guess. Yeah, mainly looking at what led her to that point.

The level of context provided differed between participants. While Jack's account looked at events involving his ex-partner over several years, ‘Andrea's’ discussion of observing two friends arguing was more tied to the specific situation. In Andrea's account, she stressed that ‘. . . it's not just something that's happened . . . once. So, yeah, I'm pretty aware of how she feels about him sort of bringing it up.’ It was unclear from her recounting of the situation whether this contextual information had limited Andrea's perspective taking in the new (spoken about) situation: ‘I just know that's her and that's what she does so I don't . . . look too much into it.’ In a later interview, Brooke suggested that previous occurrences were not necessarily a help to her in taking her sibling's perspective:

So, thinking back on all those different occasions, it was just like watching reruns. I could see the pattern . . . I just didn't know how to stop it, because I just wanted her to fix . . . like her way of thinking.

The participants’ discussions of personal or situational information did not appear to be for the purpose of providing background information to the interviewer. Instead, it seemed to be personally useful to the participant, in terms of either accomplishing the process of perspective taking, or for their personal understandings about the situation they were describing.

Use of self-information

More predominant in many of the narratives than the use of other-information was the theme of use of self-information. One of the first noticeable subthemes regarding self was switching places with the other person. Cameron attempted to take the perspective of his customer, who was frustrated and angry at a product not being available:

Well I sort of tried to, I suppose . . . not physically, but sort of imagine if I was that customer — I was a customer after something . . . that I really wanted and I spent all this time thinking that I do want it, and I come in all this way to get it and we haven't got it.

Daniel's narrative is useful in reflecting an internal shift that participants often saw as undergoing perspective taking: ‘I put myself in her place, and looking at things like what would happen, how would I feel if I lost my mother.’ While Nicholas had not experienced an infidelity, he took a methodical approach in taking his girlfriend's perspective and considering how he believed she would feel. Others similarly referred to such a strategy, although the switch was not necessarily always referred to as explicitly: ‘. . . and then I started to think about how . . . if the same thing happened to me, that I wouldn't probably like my husband coming in and changing all my things around’ (‘Elizabeth’).

In many cases, in order to accomplish such a shift, use of self-information was used to compare and contrast the responses of the other person. For example, when trying to understand her daughter's aggressive response, Michelle mentioned that ‘I know myself I don't like being nagged’, although she, as an only child, had problems in understanding why her two daughters did not appreciate each other more. She appeared to compare her potential response to a situation with that of her daughter, and found ways that were useful to understand her daughter. Daniel reflected that his strategy of imagining himself in his mother's place as she grieved the loss of his grandmother was particularly useful, given that he was close to his own mother.

Use of self-information also occurred in the theme of past experience; that is, where the participant had previously experienced a similar situation to that of the other person (similar experience to other), or had experienced a similar situation/role to what they were experiencing/occupying now (similar role in previous situation). The first theme, similar experience to the other, was more prevalent. For example, Joshua reflected that bringing a song to the band and anticipating on whether they would like it was an experience that happened ‘all the time’. His discussion of past experience was elicited when speaking of how easy (named past experience and ease of perspective taking) it was to imagine what his band mate was thinking and feeling:

Yeah because you'd been in that situation yourself, I guess. Every time . . . you bring something that's your own into rehearsal you . . . always think . . . are they working on it . . . just to be nice or if they really like . . . what you're playing.

Cameron and Nicholas had occupied a similar position to that which they were in now. Cameron had dealt with problematic customers before, and ease was similarly apparent: ‘. . . relatively easy I suppose only because I've been in that situation for several years’. Nicholas reflected both on his difficulty in imagining his girlfriend's perspective, and also how he had occupied a similar role previously (having been unfaithful to another partner). For Nicholas, perspective taking was difficult in the new situation: ‘No, it wasn't [easy], because it's never happened to me before . . . Like as much as I tried to understand, um, the kind of, you know feelings she was feeling, I've never felt them myself.’ Nicholas’ previous experience was one in which he was quick to point out the differences, and how it was not a situation that came to mind during the taking of his current girlfriend's perspective.

What emerged from the narratives was that the person needed to make a connection with a past situation for it to have some impact. Jack had been in a similar situation to that of his ex-girlfriend and also occupied a similar position to that which he had found himself in now: ‘. . . another mate of mine has a girlfriend . . . that none of us approve of.’ However, only his similar experience to his ex-girlfriend entered his mind while he was trying to take her perspective. Somewhat contradictory, however, was that Jack did not find it particularly easy to take his girlfriend's perspective in the service of understanding: ‘. . . in my perspective I just wouldn't let myself get into a situation like that.’ Natasha explicitly referred to the use of her past experience, although she made important differentiations: ‘I tried to think of previous experiences in which I hadn't wanted to get out of bed and why they had occurred, and I tried to assess . . . if . . . [they] would be applicable to her situation or not.’

Use of general information

Another process theme emerged whereby participants used general information about situations or people's reactions to them in order to take the other's perspective. It was a theme that emerged less, and was often referred to in passing (e.g., Michelle's comment that ‘Strange answer but it's hard to work out young children’ or Jack's ‘I think part of it was the very feminine thing of wanting to help’). Nicholas, who had not experienced a similar situation to that of his girlfriend suggested: ‘You can't sort of release that news to someone . . . and expect them to sort of take it lightly, especially if they feel strongly for you.’ Laura had been married and had theories regarding getting married: ‘. . . at the same time they've got all these aspirations and hopes and dreams and plans . . . which is sort of also normal’. It seemed that these general theories could be based on information from direct experience, or more general notions regarding thoughts, emotions, and behaviours.

Ease and process

Besides emerging in discussion of the use of past experience, a more general theme of ease as it related to taking another's perspective (ease of process) was examined in some detail. Overall, the idea of perspective taking being effortful was reflected in a number of narratives: ‘Yes I tried harder to understand’ (Elizabeth). Often, taking the point of view of the other was seen as difficult because of initial anger or annoyance: ‘I had to actually kind of pull myself back, calm myself down to see why, what information she was giving me and how I could interpret that to see how she was feeling’ (Natasha). ‘Emily’ found that once her anger had diminished, she was able to take the perspective of her friend, and actually found it rather easy to do so: ‘I would have . . . taken time out to understand what had happened, whether there's some confusion or something, instead of jumping to conclusions.’ Some parts of understanding the other's vantage point (e.g., understanding emotions) could be easier than others (e.g., their behaviour), and related to what tools the individual had to accomplish this. For example, Michelle had contextual information and information about herself in order to attempt to understand her daughter's emotions. Daniel, on the other hand, did not see himself as ‘a terribly emotional person’, and said that he had to imagine concrete things that would occur if his own mother passed away.

Brooke and Natasha found moving away from their own perspectives difficult, as well as the types of attributions they were making for the behaviour of the other person: ‘. . . oh she probably doesn't want to get out of bed because she's lazy . . . but then I'd think, well she's probably not thinking she's lazy . . . so not putting a negative spin, and a negative connotation on it was difficult’ (Natasha). This seemed to again relate to the process of shifting between self-information and information about the other, and the difficulties that can occur in such a situation.

Emotional and Cognitive Outcomes

An attempt was made in early interviews to elicit from participants their thoughts and feelings both during and following the perspective-taking process. Participants often found this difficult, and so later interview questions enquired more generally about thoughts and feelings (rather than a focus on when they occurred). In participant discussions, however, there was a differentiation that was more apparent, particularly when the person trying to understand another's perspective experienced some change in their thoughts or feelings as a result of doing so.

In many of the narratives there was a level of emotional matching, where the participant and the other person experienced similar feelings. However, the causes of similar emotional responses were often different. Both Joshua and his band mate experienced frustration: Joshua's from working longer than he would have liked on a song while the other band member's frustration was perceived to be the reluctance of the other members to do so. Similarly, while Nicholas's girlfriend was thought to be upset at hearing of the infidelity, Nicholas was also upset, although this was self-directed at his actions. Nicholas also felt guilt for what he had done as he assessed he was to blame for the situation. Guilt was an important part of Brooke's experience, and this emerged complexly in her consideration of the situation, her attributions, and the use of self-information: ‘. . . I feel really guilty because I feel like I haven't been there for her . . . But that's counteracted with anger, in the sense that she's not being honest about things.’

Another theme was labelled sympathy because it was referred to by participants and because it accorded well with definitions in the literature. Cameron, for example, spoke of an almost-emotional matching (although the cause of frustration was different) and alluded to a frustration with the customer's plight (as opposed to with the customer): ‘. . . from my point of view and her point of view’. An almost staged-process occurred: ‘I did start to take her position and I was starting to think all right . . . I'll try all that I can do to try and get this for the customer.’ Joshua's interview further elucidated this somewhat motivational component of sympathy: ‘Well, I don't know if sympathy is the word, but you . . . kind of see where he's coming from, and you feel like . . . you owe it to [him to] . . . work on that.’ While Brooke was happy in being able to communicate her perspective to her sister, she believed that her sister was still unhappy with the situation, and that she felt a motivation in this respect: ‘I'm fighting my selfishness in me to maintain my lifestyle that I'm enjoying, with the need to be able to help her now.’

Often it was explicit feedback that allowed the participant to infer the accuracy of their perspective taking. Four participants referred to verbal feedback from the other person as a way to judge that they had understood the thoughts and feelings of the other person. Another three referred to particular behaviours on the part of the other person (e.g., a display of happiness from her husband when Elizabeth decided to cease cleaning his workspace); and one referred to body language as being a good indicator: ‘. . . usually you . . . can tell by the body language; like he can [laughs], and I can tell by his body language and stuff what we're thinking.’ Jack approached it somewhat differently; for him, it was the behaviour of his ex-girlfriend and the perceived ‘match’ between this behaviour and his thoughts about her past which allowed him to infer the accuracy of his perspective taking.

Behaviours and Resolution

Participants frequently spoke of engaging in a particular behaviour following their perspective-taking effort (e.g., helping their customer). At other times, the decision was to ‘withhold’ behaviour. Jack, for example, decided to discontinue questioning his ex-girlfriend's choice, and Andrea decided not to intervene in her friends’ problems. It seemed that participants judged the appropriateness of their behaviour in deciding what to do.

Satisfaction with the interaction seemed to relate very much to the perspective-taking effort. Michelle, for example, believed that she understood a little bit more about how her daughter was feeling and was reasonably happy with the interaction (as was her daughter), and that it would inform how she handled the situation in the future. For Cameron and others, a lack of perspective taking at the beginning of the interaction left them a little unhappy with the interaction: ‘if . . . a similar situation came up again I'd probably, try the way I felt at the end of it, try and sort of impose that to start with.’

Discussion

The present study investigated the process by which individuals attempt to take the perspective of another person during an interpersonal interaction. The study revealed a number of ways in which people undertake the process of perspective taking, as well as generating further ideas about how the process of perspective taking fits into the wider empathic experience. This contributes to building on Davis’ (Reference Davis1994) model of empathic responding.

By asking participants to reflect on the process of perspective taking, it was assumed that (a) such processes are in some way deliberate or of a nature to which they are consciously aware; and (b) individuals can reflect on the processes and strategies they use. In regard to the first assumption, conceptualisations of perspective taking support the more voluntary and conscious nature of the process (e.g., Coricelli, Reference Coricelli2005; Hoffman, Reference Hoffman2000), although a comprehensive review by Hodges and Wegner (Reference Hodges, Wegner and Ickes1997) suggested that perspective taking can share both elements of automaticity and controllability. Goldman (1989/Reference Goldman, Davies and Stone1995) has stressed that our attempts to understand others by simulating how we would feel in their position can both exhibit automaticity and be influenced by previous efforts. With such a view, there will be times when the perspective-taking process (or parts of it) runs relatively easily or with minimally reported cognitive effort, while at other times it may be subjectively felt as less easy, more conscious, and/or called upon (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Conklin, Smith and Luce1996; Fennis, Reference Fennis2011; Roβnagel, Reference Roβnagel2000). It is likely that the latter situations are the type discussed by many of our participants.

In terms of participants’ ability to reflect on their perspective taking, Hodges and Wegner (Reference Hodges, Wegner and Ickes1997) believe that empathy should be conceptualised as ‘an organized mental activity . . . and can be most clearly understood as a state of mind’ (p. 312). This led them to assert that, ‘The more noteworthy implication of classing empathy as a mental state, however, is the recognition that empathy is a state of our minds upon which we can reflect’ (p. 313). This is also a good fit for the realist qualitative approach (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) adopted in the present study. Of course, it is not possible to be sure that the cognitions, emotions, and processes reported were those exactly experienced by participants during the interaction.

The Situations

In almost all cases, participants chose to discuss an event that involved conflict and the presence of negative emotions. This is in keeping with the majority of previous research in this area, where even studies that investigate prosocial responses often involve imagining the feelings and thoughts of a person experiencing a challenging situation (e.g., Batson et al., Reference Batson, Early and Salvarani1997). The question arises as to why participants freely chose to focus on events with a somewhat predominantly negative emotional characteristic. One possible explanation is that the need for perspective taking may be more apparent when there is a problem in a relationship. Traditional accounts of perspective taking see dyadic interactions as involving individuals who bring unique (not necessarily different) perspectives to a situation, with the need to both understand the other's perspective and monitor whether their own is appreciated (Cottrell, Reference Cottrell1942; Mead, 1936/Reference Mead and Strauss1964). In such interactions, any problems in communicating or understanding/being understood are likely to be more noticeable, and thus may be more salient or remembered by the person. The importance of understanding to the empathy experience has emerged in previous research (e.g., Håkansson & Montgomery, Reference Håkansson and Montgomery2003), and suggests that this was not only a function of the use of the word in the induction. Instead, participants actively attempted to move from a place of lack of understanding to restore some part of a relationship.

The Process

The present study revealed more about what the individual did when taking the other's perspective. Consistent with previous research involving inductions (e.g., Batson et al., Reference Batson, Early and Salvarani1997; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Soderlund, Cole, Gadol, Kute, Myers and Weihing2004; Stotland, Reference Stotland and Berkowitz1969), other- or self-information was found to be widely used by participants. However, the findings extend that research by illustrating how information from these two psychological perspectives is used in an interaction. Central to that interaction was a shifting between the individual's own perspective and the perspective of the other. Participants frequently referred to struggles in doing this, and to circumstances where their own perspective in a situation prevented a fuller understanding of the other person. This provides a picture of the problems or issues that individuals typically grapple with in attempting to set aside their own vantage point to take on that of another, as well as the errors that can occur (see Epley et al., Reference Epley, Keysar, Boven and Gilovich2004 and, recently regarding transparency overestimation, Vorauer & Sucharyna, Reference Vorauer and Sucharyna2013). It also highlights a key component of perspective taking: namely, perspective is used in a dynamic way.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that participants differentiated between the use of information about the other person and the use of the self. Information about the other tended to involve knowledge of their characteristics and situation. This is a particularly valuable finding, as theory and research has often failed to consider the use of contextual information in the perspective-taking process. Indeed, in discussing empathic accuracy, Stinson and Ickes (Reference Stinson and Ickes1992) stressed that ‘the perceiver's cognitive activity be based in large measure on real knowledge of the other and of his or her circumstances and not merely on supposition, analogy, or projection’ (p. 788). Participants made use of such information, although they also reported engaging in analogy such as use of the self in understanding the other.

Use of self-information in taking the other's perspective was a prevalent theme. Participants discussed switching places imaginatively, and this often involved comparing their imagined perspective to the hypothesised perspective of the other actually experiencing the situation to see if this strategy was useful. This makes sense given that imagining oneself in another's position also requires an assessment of whether this perspective is a suitable ‘substitute’ for that of the other (Epley et al., Reference Epley, Keysar, Boven and Gilovich2004; Gordon, 1986/Reference Gordon, Davies and Stone1995). For example, using one's own perspective might not be seen as suitable if the empathiser is dissimilar to the other person. The literature on the use of self-information is somewhat equivocal; Ames (Reference Ames2004) posited a model where perceptions of similarity between self and other lead to the use of projection when attempting to understand the ambiguous actions of the other person, with stereotyping more likely when dissimilarity is highlighted, while Todd, Hanko, Galinsky, and Mussweiler (Reference Todd, Hanko, Galinsky and Mussweiler2011) suggest that when interacting with others ‘focusing on differences increases perceivers’ ability to step outside their own perspectives’ (p. 139).

The use of past experience was identified in participant narratives, often regarding the ease of taking the other's perspective. Indeed, the use of past experience as an individual strategy seemed to carry with it the greatest reflection regarding how this helped or hindered understanding the other's thoughts and feelings. Past experience thus facilitated perspective taking, but not all past experiences discussed in interviews were used in the actual situation. Instead, it took a connection on the part of the person regarding the utility or relevance of their experience to understanding the other person. While Håkansson and Montgomery (Reference Håkansson and Montgomery2003) noted participants in their study used past experiences at differing levels of generality or abstraction, those in the present study generally used past experiences that were closer to that of the other (e.g., both having been in a problematic relationship). This finding suggests that a strategy or tool (i.e., use of past experience) may not be used only because it is available; instead, it took a reflection on the part of the person to determine its relevance (see also Preston & Hofelich, Reference Preston and Hofelich2012).

The use of more general information by participants reflects broader theories of other-person perception, including the actor-observer effect in attributions of behaviour (Regan & Totten, Reference Regan and Totten1975), theory of mind accounts (e.g., Flavell, Reference Flavell2004; Gopnik & Wellman, Reference Gopnik, Wellman, Hirschfeld and Gelman1994; Gopnik & Meltzoff, Reference Gopnik and Meltzoff1997), as well as the transformation rule model (Karniol, Reference Karniol1986), which advocates the use of a hierarchical rule system to understand individuals’ reactions to certain stimuli. According to these explanations, people not only engage with information specific or unique to the situation, but make use of frameworks for understanding others. The less explicit emergences of this theme in the text may relate to the nature of such frameworks. That is, if these verbal statements reflect the operation of underlying theories or ideas for interpreting the world, these may be less consciously reflected upon and may even be, to some extent, automatic. Lesser reference to this type of general information could also occur because such general information is not always useful in taking a specific person's perspective (Karniol & Shomroni, Reference Karniol and Shomroni1999).

While participants reflected on difficulty in moving between their perspective and that of the other person, they also discussed some specific factors that made perspective taking an effortful process. These included anger and persistent attributions for the other's behaviour. Such emotion and cognition can, of course, be interactive. The tendency to stress dispositional explanations for another's behaviour and situational explanations for one's own (i.e., the actor-observer effect) may, for example, lead to misunderstandings and anger arousal, which subsequently interferes with cognitive processing and increases the potential for aggression (Davis, Reference Davis1994). For many participants in this study, perspective taking still occurred and a somewhat satisfying resolution to the situation was reached even when there were problems in apprehending the other's perspective. It may be that the negative emotions (e.g., anger) generated were of a quality that did not heavily disrupt the empathic process or, at least, did not apply to the whole interaction. Alternatively, the nature of existing acquaintances (e.g., largely family or friends were discussed) meant that participants felt that they had greater knowledge of the other's intentions and/or did not want to engage in anger or aggression toward close others. It could also be that the situations participants chose to discuss involved more ambiguity as to why the other person was acting a particular way. In situations where another person is clearly at fault, for example, seeing this through taking the other's point of view may not diminish anger and aggressive responses or generate empathic actions, particularly for those whose relationships with others are important to their own identity (Okimoto & Wenzel, Reference Okimoto and Wenzel2011).

Emotions, Cognitions and Behaviours When Empathising

Participants provided rich descriptions of emotions, cognitions, and behaviours that occurred during the perspective-taking experience. Empathic responses of a more reactive nature (Davis, Reference Davis1994) such as guilt were discussed, and similar emotions between empathiser and recipient often came about for different reasons. It may be that participants did experience more parallel-type emotions to those of the other person, but focused in their narratives on the feelings that arose due to their own unique perspective. This is likely to be particularly prevalent in situations where the participant is actively involved in the event, and not merely an observer.

Prevalent within discussion of affect was sympathy as a behaviourally motivating experience, a finding that accords well with theory and research supporting the motivational component of empathy or sympathy in areas such as helping (Batson, Reference Batson1991, Reference Batson2011; Wispé, Reference Wispé1986; Zhou, Valiente, & Eisenberg, Reference Zhou, Valiente, Eisenberg, Lopez and Snyder2003). The theme was labelled ‘sympathy’, as it moved beyond definitions of emotional empathy, which stress an emotional reaction without (necessarily) a behavioural component. Participants did sometimes decide not to enact an explicit behaviour. This is behaviour in itself, although harder to recognise as such (Guerin, Reference Guerin2004). Indeed, a diverse range of possible ‘behavioural’ manifestations of empathy were discussed by participants (see Kerem et al., Reference Kerem, Fishman and Josselson2001 for similar findings).

Perspective taking was perceived to have many positive or relationship-enhancing properties, while, as mentioned, a lack of perspective taking at some points during an interaction often caused problems. Although this supports notions of the positive outcomes of taking another's perspective, participants may have chosen situations that involved more successful perspective taking and/or resolution of a problematic situation. Several participants did, however, reflect on more ambivalent situations. A related factor here is the notion of accuracy, since appreciation of another's perspective in as accurate a manner as possible would seem a prime objective for satisfaction (particularly for the other person). Participants reported that they discerned accuracy primarily through some sort of feedback, which highlights the often neglected importance in empathy research of verbal, facial, and bodily feedback (Ickes, Stinson, Bissonnette, & Garcia, Reference Ickes, Stinson, Bissonnette and Garcia1990). This may again relate in part to the reported experiences (i.e., a direct ‘physical’ contact with another person), as in situations where such feedback is not available and an inference of accuracy is required, other strategies are likely to be needed. However, it does suggest that interactions with others often result in quite concrete information as to their thoughts and feelings (Ickes et al., Reference Ickes, Stinson, Bissonnette and Garcia1990).

Limitations

There are limitations to the present study. The induction was prescriptive in defining perspective taking, and a framework of the empathic experience (Davis, Reference Davis1994) directed the analysis. However, the questions did not enquire about the presence of particular processes or emotions and, as such, participant responses suggested that the narratives were not unduly constrained by the way in which questions were asked. Nonetheless, participants were allowed to choose a situation to reflect upon and, as such, experimental control over the types of situations utilised could not occur. The sample was small and somewhat heterogeneous in age and occupation. Sex, age, and other differences in empathic responding have been previously identified (Lennon & Eisenberg, Reference Lennon, Eisenberg, Eisenberg and Strayer1987) and may have influenced the findings of this study. Similarity in participant responses (e.g., methods in perspective taking), suggest that core strategies are typically used when taking another's perspective. Nonetheless, it is not possible to generalise these findings with confidence, given the nature of the participant sample.

Conclusion and Future Research

The main purpose of this exploratory study was to investigate the perspective-taking process and, in doing so, extend understanding of this empathic component. A qualitative approach was chosen for, as Smith (Reference Smith1996) contends: ‘while quantitative research can operate at a macro level, constructing broad models of, for example, cognition and behaviour relationships, qualitative research will work at the micro level, exploring the content of particular individuals’ beliefs and responses and illuminating the processes operating within the models’ (p. 265). In this way, the research extends Davis’ (Reference Davis1994) model and meets the calls of researchers decades apart (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Soderlund, Cole, Gadol, Kute, Myers and Weihing2004; Dymond, Reference Dymond1949) for greater investigation of perspective taking and empathy. For participants, perspective taking was in the service of understanding another person in situations of some conflict, and involved the use of a number of processes and strategies. These strategies included using information about the other person and their situation, switching places with them, comparing and contrasting self and other perspectives, use of past experience, and utilising general theories for understanding others. A central component of the findings regarding the process, as well as findings pertaining to affective and behavioural outcomes, was the regular shift between the self and the other. This notion of shifting between self and other requires further investigation in a larger study, as does the relationship between past experience and how subjectively easy it is to take another's point of view. The authors will report in a future article a study specifically investigating whether having had a similar past experience and reflection on that experience influence ease of perspective taking relative to other strategies. Another way to investigate both of these areas (self- and other-shift, past experience and ease) would be to examine how differences in self-focus and reflection on one's own past experiences (both dispositional and in a particular situation, whether manipulated or observed), as well as insight into past experiences, influence the application of such knowledge to another person. While requiring examination, the findings regarding self and other in this study could foreseeably be utilised to improve perspective-taking skills. The focus of the method used (asking a participant to focus on a particular real-life experience) on self-reflection and the perspective-taking process could provide a way for individuals to examine their perspective taking and to improve understandings of their own perceptions and those of others. This could be utilised with different groups of people, such as those who are required to take the perspective of others in a professional capacity (e.g., health professionals), as well as those who have difficulties (e.g., persons with anger issues; violent offenders) in social and personal relationships.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mikaila Crotty for useful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.