Most of the research addressing emotions in intimate and interpersonal relationships focuses on love (e.g., Hatfield & Rapson, Reference Hatfield and Rapson1993) and anger (e.g., Dutton, Reference Dutton, Potegal, Stemmier and Speilberger2010). However, relationships can have hurtful and damaging qualities that can elicit hate. Surprisingly, there is a lack of research addressing hatred in interpersonal relationships. Much research has been spent on understanding group hatred, specifically hatred towards minorities or other group members (Brewer, Reference Brewer1999; McCann, Reference McCann2009; Ray & Van Bavel, Reference Ray and Van Bavel2014). And although this research is laudable, the interpersonal dimension of hatred that deals with one's hatred towards another person (despite his/her group membership) has not been fully investigated. There are theoretical approaches to better understanding interpersonal hatred (e.g., Rempel & Burris, Reference Rempel and Burris2005; Sternberg, Reference Sternberg2003; Sternberg & Sternberg, Reference Sternberg and Sternberg2008); however, little empirical research has fully vetted these theories. Historically, much of the research on hatred in psychology comes from a psychoanalytic perspective (Blum, Reference Blum1997; Kernberg, Reference Kernberg, Shapiro and Emde1992; Klein, Reference Klein1975; McKellar, Reference McKellar1950; Moss, Reference Moss2003; Strasser, Reference Strasser1999; Vitz & Mango, Reference Vitz and Mango1997), which focuses more on the theoretical nature of hatred and less on the empirical evidence.

The primary purpose of the following studies was to better understand, from an empirical perspective, how interpersonal hatred can affect the quality of the relationship with someone hated. Much of the current literature concerning interpersonal relationships does not consider how ambivalent feelings (like having both hate and love in a relationship) can have an impact on a relationship's satisfaction. Some research does attempt to investigate how hate operates or is defined in a relationship. Fitness and Fletcher (Reference Fitness and Fletcher1993) conducted several studies on hate in intimate relationships and concluded that the overall concept of hate in intimate relationships involves low levels of control of the situation, with a high level of obstacles and significant unpleasantness. They concluded that hate may be one of the more difficult emotions to define as it is so closely categorised with instances of anger. Similarly, Shiota, Campos, Gonzaga, Keltner, and Peng (Reference Shiota, Campos, Gonzaga, Keltner and Peng2010) found that contempt and other negative emotions were more likely to be reported and experienced in Asian American couples than White American couples, suggesting that there may be cultural differences in how hate and love are experienced together, depending on degrees of emotional complexity (Larsen, McGraw, & Cacioppo, Reference Larsen, McGraw and Cacioppo2001; Larsen, McGraw, Mellers, & Cacioppo, Reference Larsen, McGraw, Mellers and Cacioppo2004). Providing further evidence that relationships, especially romantic relationships, may be prone to experiences of emotional complexity, Zayas and Shoda (Reference Zayas and Shoda2012) found that participants are more easily able to identify both positive and negative stimuli through the priming of their romantic relationships; providing further evidence that romantic relationships are prone to complexity and ambivalence. Thus, there is evidence suggesting that hate and love can coexist in a relationship; however, it is still unclear as to how it may operate.

Considering previous research has shown that the targets of one's hatred are often those we love or have loved (Aumer, Bahn, & Harris, Reference Aumer, Bahn and Harris2015; Aumer-Ryan & Hatfield, Reference Aumer-Ryan and Hatfield2007), the following studies are designed to better understand how previous feelings of hatred towards someone loved can affect the relationship. This research will answer the following questions: Does having hate in a relationship (e.g., friendship, towards a spouse, or a co-worker) damage the relationship or can it bolster the relationship, once the hatred has resolved?

Previous Research

Sternberg and Sternberg (Reference Sternberg and Sternberg2008) proposed a duplex theory of hatred that is very similar to Sternberg's (Reference Sternberg1986) triangular theory of love. While the triangular theory of love is composed of three aspects — passion, intimacy, and commitment — the duplex theory of hate is composed of anger, disgust, and devaluation/diminution. Sternberg's theoretical approach places hate on the opposite side of love. Similarly, Rempel and Burris (Reference Rempel and Burris2005) also place hate as an opposite of love, but in terms of motivation: love is intended to foster wellbeing and good intentions towards the loved target, while hate is intended to foster damage and destruction towards the hated target. Some empirical research has validated this close association between love and hate. For example, Zeki and Romaya (Reference Zeki and Romaya2008) found that similar areas in the brain (i.e., the putamen and insula) are involved with both love and hatred, and Aumer-Ryan and Hatfield (Reference Aumer-Ryan and Hatfield2007) found that hatred is often directed at those we have loved (e.g., former/current romantic partners), know well (e.g., friends and family), or spend considerable time with (e.g., coworkers, bosses, competitors).

These targets of hate are in significant contrast to the targets of hate currently discussed in the literature on aggression and group hatred that is often aimed at minorities and whose targets are often unknown and not a previous person loved (Greenwald et al., Reference Greenwald, Banaji, Rudman, Farnham, Nosek and Mellott2002; Nosek, Banaji, & Greenwald, Reference Nosek, Banaji and Greenwald2002).

According to effort justification theory, the trials and tribulations that engender hate in a close interpersonal relationship may actually solidify or bolster intimacy and feelings of liking (e.g., Aronson & Mills, Reference Aronson and Mills1959). Similarly, cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962) suggests that participants still in a relationship in which they previously had feelings of hate should elicit stronger or more positive feelings about the person, because the relationship is still ongoing. As a person remains in a relationship that involves both love and hate, he/she may justify the amount of time, effort, and work put into the relationship by believing the relationship has endured the tribulations and hardships common in relationships. Thus, the relationship may be viewed as stronger than a relationship that has never had to ‘test’ the relationship's strength or bond. For many couples, it may be that having had an instance of hate in their close interpersonal relationship may produce a stronger or closer relationship than one in which no hate has been experienced.

In contrast, if hate really is a motivation to destroy the target of hate (Rempel & Burris, Reference Rempel and Burris2005), then having a relationship with someone you want to both destroy and cultivate a relationship with may produce irreconcilable conflict that affects the quality of the relationship. Thus, an alternative prediction would be that a relationship with previous instances of hate is less intimate than a relationship without any experiences of hate, due to the conflicting desire to both destroy and nurture the target of one's hate and love. The following studies were conducted to explore which of these hypotheses would best describe and explain the function of hate in current interpersonal relationships. If hate is only an emotional obstacle in a relationship in which one can overcome through effort justification, participants will report a higher quality in their relationships with a person they love but have hated versus someone they love and have never hated. However, if hate is a destructive motivation, participants will report a lower quality in their relationships with someone they love but have hated versus someone they love and have never hated.

STUDY 1

Method

Participants

The study received approval from Hawaii Pacific University's Institutional Review Board. One hundred and fifty-four participants took the survey, but 34 were eliminated due to not following or understanding directions. Participants were sampled for a 4-week period from the Hawaii Pacific University (HPU) subject pool. An additional sample of 74 participants was collected over the course of 12 weeks, providing a final sample of 228 participants (Female = 175, Male = 51, Other = 2). Ages ranged from 18 to 63 (M = 22.59, SD = 7.94). Reported ethnicities were: White (39%), Mixed (28%), Asian (21%), Hispanic (7%), Black (4%), and Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (2%).

Materials and Procedures

An online survey was created in Qualtrics and the URL was made available to students in the HPU subject pool via Facebook and Amazon Turk. All participants completed the demographics section first and were randomly assigned to complete the section on Person A (person you love and have never hated) or the section on Person B (person you currently love and have had feelings of hatred in the past) first. Order was not significant in predicting any of the dependent variables and thus was not included as a covariate in future analyses. Participants also took a personality questionnaire (TIPI; Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003), which is not presented in this study as it pertained to a separate research question.

Person A and B questions

We specifically asked participants to report on the quality of their relationships for two different people: Person A, who is loved and never hated, and Person B who is loved and at one time hated. Participants were also asked to identify the relationship type of Person A and Person B: (e.g., mum, dad, sister, brother, friend). Specifying a person not listed on the list of possibilities was an option. Length of relationship in years and two open-ended questions — ‘Why do you love the person?’ and ‘Why do you hate the person?’ (only for Participant B) — was asked of each participant. To screen for participants who did not have hate (in the past) for Person B or had hate for Person A, participants were asked if they ever hated or felt contempt for Person A and Person B. Our original sample included 313 participants; however, 84 participants were eliminated from the study due to not following directions (44 claimed to have hated Person A and 40 claimed to have never hated Person B), providing a final sample of 228.

Effort justification and cognitive dissonance

To measure how much effort participants put into their relationships, we asked participants: ‘How long have you known Person A/B?’ Given effort justification theory (Aronson & Mills, Reference Aronson and Mills1959) and cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962), the more time spent with and knowing someone may facilitate the desire to justify that time and to see the relationship and person as more desirable and satisfying than relationships without as much time invested. Participants reported knowing Person A an average of 11.33 years (SD = 9.40) and Person B for 12.19 years (SD = 11.25).

Intimacy

The 17-item Miller Social Intimacy Scale (MSIS; Miller & Lefcourt, Reference Miller and Lefcourt1982) was used to measure intimacy. Two subscales, Intensity (6 items) and Frequency (11 items), were measured using a 10-point Likert scale (1 = not much/very rarely to 10 = great deal/almost always). Participants filled out a MSIS for Person A and Person B. Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for Person A on both subscales (Intensity = 0.67; Frequency = 0.91) and Person B (Intensity = 0.78; Frequency = 0.95).

Love

The 45-item Sternberg (Reference Sternberg1997) Triangular Love Scale (TLS) was used to measure love. Three subscales with 15 items each (Passion, Intimacy, and Commitment) were were measured using a 9-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 9 = extremely). Participants filled out the TLS for both Person A and Person B; however, the subscale of passionate love was not included for participants who did not identify a romantic partner for Person A or Person B. Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for romantic Person A on all subscales (Intimacy = 0.97; Passion = 0.97, Commitment = 0.97) and non-romantic Person A (Intimacy = 0.97; Commitment = 0.97). Similarly, reliability was good for romantic Person B (Intimacy = 0.98; Passion = 0.98, Commitment = 0.98) and non-romantic Person B (Intimacy = 0.98; Commitment = 0.97).

Hate

The 29-item Sternberg & Sternberg (Reference Sternberg and Sternberg2008) Triangular Hate Scale (THS) was used to measure hate. Three subscales: Disgust (10 items), Anger (9 items), and Devaluation (9 items) were were measured using a 9-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 9 = extremely). Because Person B should be a person loved and at one time hated, these items were reworded to be in the past tense. Participants filled out the THS for Person B. Participants also filled out the THS for Person A only if they mentioned having ‘felt extreme anger towards this person or had had an argument with this person’, and were thus instructed to fill out the THS with this episode of anger or argument in mind. Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for Person B on all subscales (Disgust = 0.95; Anger = 0.92; Devaluation = 0.96) as well as for Person A (Disgust = 0.96; Anger = 0.97; Devaluation = 0.97).

Relationship satisfaction

The seven-item Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) was used to measure relationship satisfaction (Hendrick, Reference Hendrick1988). Although this scale was intended for romantic couples, the wording of the questions could apply to any loving relationship. We changed any item that used ‘partner’ with ‘person’. Participants filled out the RAS for both Person A and Person B. Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for Person A (0.87) and Person B (0.84).

Results

Participants tended to choose a Family member (e.g., mom, dad, sibling), Friend, or Romantic partner (e.g., husband, wife, boyfriend) as their Person A (see Table 1). A few people chose their Ex-Romantic partners or Other (both co-workers). A similar breakdown can be seen for Person B; however, more participants chose an Ex-Romantic partner as Person B.

TABLE 1 Percentage of People Chosen as Person A and Person B for U.S. Sample

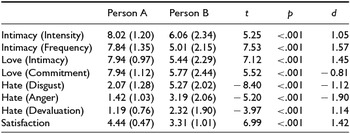

To discover if relationships that had previous feelings of hate were of less quality than relationships that had never had experienced hate, a paired samples t test was performed on intimacy (both frequency and intensity), love (Sternberg's Intimacy and Commitment subscales), hate, and relationship satisfaction. Means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 2. Analyses for both romantic and non-romantic individuals were clumped together and analysed; t tests revealed that intimacy, love, and relationship satisfaction were rated lower for Person B in comparison to Person A. Similarly, there were stronger feelings of hate (with the Sternberg Hate subscales) towards Person B. The effect for previous feelings of hate was large, as can be seen by Cohen's d. One could argue that it is not the previous feelings of hate that shape the relationship quality, but the relationship type. For example, people may just report having better relationships with their mothers (or other family members) than with their friends, because of the nature of the relationship, and this may have nothing to do with previous feelings of hate.

TABLE 2 Means and Standard Deviations of U.S. Participants and Their Intimacy, Love, Hate, and Relationship Satisfaction of Person A Versus Person B

Note: To calculate the Cohen's d in a paired samples t test, the pooled sample variance was used and can be referred to as Cohen's d subscript z (Lakens, Reference Lakens2013).

To control for relationship type, we conducted paired sample t tests with only participants who identified having a similar relationship with their Person A as they did with their Person B (e.g., naming a friend for Person A and a friend for Person B). Sixty-two of our 228 participants had similar relationship types for both their Person A and Person B. Most participants identified family members (n = 29) or friends (n = 26) as both their Person A and Person, B while the remaining seven identified ex-lovers. Of these participants, few (n = 16) ever felt anger or could remember an intense argument with their Person A, and thus the paired sample t tests for the THS was not compared. As can be seen in Table 3, the impact of hate on the relationship qualities of intimacy, love, and satisfaction is comparable to the comparison of those who named dissimilar relationship types for their Person A and Person B. Participants rated less intimacy, love, and satisfaction for their friends, family, and ex-lovers when hate was previously experienced in the relationship.

TABLE 3 Means and Standard Deviations of U.S. Participants and Their Intimacy, Love, and Relationship Satisfaction of Person A Versus Person B for Same Relationship Type

Note: To calculate the Cohen's d in a paired samples t test, the pooled sample variance was used and can be referred to as Cohen's d subscript z (Lakens, Reference Lakens2013).

To test if effort justification or cognitive dissonance contributed to the perception of relationship quality, we conducted a multivariate regression analysis with the outcome variables hate, love, intimacy, frequency, and satisfaction, As can be seen in Table 4, time knowing Person B was statistically significant in predicting one's commitment to Person B, as well as anger felt towards Person B. Specifically, the more time knowing Person B, the more committed and angry one felt towards Person B. Additionally, if one is in a romantic relationship with Person B, passionate love seemed to be affected by the length of time knowing Person B. Specifically, the longer one knew Person B, the lesser the passionate love one felt towards Person B. Examining partial eta squares reveals that this relationship only accounted for a small amount of variance. Additionally, when the same multivariate regression analysis was done for Person A, the only statistically significant parameter estimate was observed with passionate love: B = -0.06, SE =0.03, t = -2.10, p = .04, partial eta squared = 0.06, suggesting that passionate love decreases in a relationship over time, despite the presence of hate. However, commitment and anger were not related to the amount of time Person A was known, providing further evidence that over time, the presence of hate may lead one to ‘justify’ the time spent with someone in which the relationship is less than satisfactory, and thus participants reported an increased commitment to Person B as time went on.

TABLE 4 Multivariate Regression Analysis Predicting Intimacy, Love, Hate, and Satisfaction From Time Spent Knowing Person B

Discussion

Our data revealed that previous instances of hate negatively affected the quality of the current relationship. The type of relationship (e.g., family member, friend, or romantic partner) did have an impact on the scales of intimacy and satisfaction, suggesting that future research may want to consider previous instances of hate or contempt as well as relationship type when assessing relationship quality, as these relationships with their previous feelings of hatred may be of lower quality. Additionally, some support was found for effort justification or cognitive dissonance. The longer one reported being in a relationship with someone they have had previous feelings of hate directed towards, the more committed, less angry, and, if in a romantic relationship, less passionate the person reported feeling towards that individual. Again, future research should consider the presence of hate when measuring the commonly considered constructs of satisfaction, love, and anger, as it appears the presence of hate and length of time in the relationship may be related to their outcomes.

Although this sample of participants readily disclosed feelings of hate, several participants in previous studies (e.g., Aumer, Bahn, & Harris, Reference Aumer, Bahn and Harris2015; Aumer-Ryan & Hatfield, Reference Aumer-Ryan and Hatfield2007) reported never experiencing hate and would not be able to hate. It may be that there is a cultural taboo of hate in the United States and our participants were an unusual group of people who went against this taboo. It may be that hate is culturally dependent and with a sample from a different country or cultural background, the relationship between relationship quality and hate would be different. To address these issues, we conducted a second study with the same measures using a sample in Norway.

STUDY 2

Method

Participants

The study received approval from HPUs Internal Review Board. To help increase participation, participants were told that they could enter for a chance to win 500 Norwegian Kroner (~USD70). The study was open for a 4-week period, and although 217 participants began the survey, more than 72% of participants dropped out before completing the survey. Sixty-one participants completed the survey, but 15 were eliminated due to not following or understanding directions. Participants were sampled from Facebook, different Norwegian forums such as Kvinneguiden.no and Freakforum.no (general forums where people go for information), and on the Lillehammer University College website. A final sample of 46 participants (Female = 29, Male = 17) was retained. Ages ranged from 19 to 69 (M = 25.85, SD = 11.32). Due to cultural sensitivities about asking participants about their racial and ethnic identity, participants were not asked about race or ethnicity.

Materials and Procedures

The same measures and procedures were used for Study 2 as they were for Study 1. All the measures were translated into Norwegian, with the exception of the TIPI (Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003) as this measure was already translated by two native speakers of Norwegian. (Like the U.S. data, information regarding the TIPI is not presented here as it pertained to a separate research question.) Each measure was then independently back translated by two volunteers who were also native speakers of Norwegian. The forward and back translations continued several times until back translations from Norwegian into English were understandable and agreed upon 100%. Because Norwegian has two distinct words for love — one being romantic love and the other a friendship love — both words were included in the Sternberg's love measure. The study was advertised and open for 4 weeks and closed at the end of 4 weeks. Considering the same procedures were used in Study 2 as they were in Study 1, only the reported reliabilities for this sample are provided.

Effort justification and cognitive dissonance

Participants reported knowing Person A for an average of 13.02 years (SD = 12.80) and Person B for 13.71 years (SD = 12.91).

Intimacy

Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for Person A on both subscales (Intensity = 0.79; Frequency = 0.89) and Person B (Intensity = 0.86; Frequency = 0.93).

Love

Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for romantic Person A on all subscales (Intimacy = 0.95; Passion = 0.86, Commitment = 0.94) and non-romantic Person A (Intimacy = 0.95; Commitment = 0.89). Similarly, reliability was good for romantic Person B (Intimacy = 0.92; Passion = 0.86, Commitment = 0.74) and non-romantic Person B (Intimacy = 0.98; Commitment = 0.98).

Hate

Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for Person B on all subscales (Disgust = 0.92; Anger = 0.96; Devaluation = 0.99) as well as for Person A (Disgust = 0.91; Anger = 0.95; Devaluation = 0.96).

Relationship satisfaction

Reliability (measured with Cronbach's alpha) was good for Person A (a = 0.82) and Person B (a = 0.92).

Results

Participants in Norway reported knowing both Person A (M = 12.11, SD = 11.46) and Person B (M = 13.22, SD = 9.88) for an average of between 12 and 13 years. As can be seen in Table 5, and similar to the U.S. sample, participants tended to choose a Family member (e.g., mom, dad, sibling), Friend, or Romantic partner (e.g., husband, wife, boyfriend) as their Person A. A similar breakdown can be seen for Person B; however, more participants chose either a Friend or an Ex-Romantic partner as Person B.

TABLE 5 Percentage of People Chosen as Person A and Person B for Norwegian Sample

A paired samples t test was performed on intimacy (both frequency and intensity), love (Sternberg's Intimacy and Commitment subscales), hate, and relationship satisfaction to assess the relationship between previous feelings of hate and relationship quality. Means and standard deviations are displayed in Table 6. As was seen in the U.S. sample, paired t tests revealed that intimacy, love, and relationship satisfaction was rated lower for Person B in comparison to Person A. Similarly, there were stronger feelings of hate (with the Sternberg Hate subscales) towards Person B. The effect for previous feelings of hate was quite large, suggesting that previous feelings of hatred can greatly affect the current quality of the relationship.

TABLE 6 Means and Standard Deviations of Norwegian Participants and Their Intimacy, Love, Hate, and Relationship Satisfaction of Person A and Person B

Note: To calculate the Cohen's d in a paired samples t test, the pooled sample variance was used and can be referred to as Cohen's d subscript z (Lakens, Reference Lakens2013).

Unfortunately, only 17 participants reported having a similar relationship with their Person A as they did with their Person B, and thus controlling for relationship type was not possible as previous power analyses revealed that a sample size of at least 30 was required to test the relationship between relationship type and the relationship quality variables.

To test for effort justification and cognitive dissonance, we conducted the same multivariate regression analysis with time knowing Person B as the predictor and the outcome variables of hate, love, intimacy, frequency, and satisfaction, Unlike the U.S. sample, the only parameter estimate that was statistically significant for Person B was passionate love: B = -0.07, SE = 0.03, t = -2.65, p = .01, partial eta squared = 0.04; commitment and anger did not seem to be related to length of relationship. Also, unlike the U.S. sample, passionate love did not seem to decrease for Person A as the relationship progressed: B = 0.01, SE = 0.02, t = 0.30, p = .76, partial eta squared = 0.002, suggesting that cultural differences may exist in how relationships with love and hate are perceived over time.

General Discussion

Current research on hate is largely theoretical and by providing empirical evidence on how hatred in interpersonal relationships may operate we hope to further the understanding of hate in general. We conducted two online studies that assessed hatred in interpersonal relationships in two different countries: the United States and Norway. We specifically asked participants to report on the quality of their relationships for two different people: Person A, who is loved and never hated; and Person B, who is loved and at one time hated. By assessing relationship quality with these two different people (Person A and B), we hoped to better understand how hate operates and functions. Previous research and literature suggests that hate may have counterintuitive effects. For example, when looking at literature concerning groups and how people feel about groups they may love or hate, effort justification theory (e.g., Aronson & Mills, Reference Aronson and Mills1959) and cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, Reference Festinger1962) suggests that previous experiences with hate may help bolster the quality of a relationship because people put in more effort to make these relationships work. Similarly, people may alleviate the anxiety or dissonance created by being with someone they both love and have hated, by reporting a stronger relationship with that person, than in a relationship where no hate was ever reported. However, Rempel and Burris (Reference Rempel and Burris2005) posit that hatred is a motivation to destroy. If hate is really a destructive motivation, it may be difficult or impossible to reconcile that motivation, even with strong feelings of love.

The data presented here suggest that hate has a very negative impact on an interpersonal relationship, such that even when the hate has resolved, participants still rate their interpersonal relationships as less satisfying and intimate. Additionally, participants also rate feeling less love and more feelings of hate towards someone whom they love and once hated. The Norwegian sample showed the same relationship, further bolstering evidence that hate may leave a lasting impression on a relationship, even when people declare that the hate is no longer felt within the relationship. When we controlled for relationship type by examining relationship quality only for those who reported similar relationship types for Person A and Person B, we found that people still reported less satisfaction, love, and intimacy for their Person B than their Person A, further supporting the idea that residual hate in a relationship is not easily let go across all relationship types (e.g., family, friends, and ex-lovers).

When we examined the impact of effort justification or cognitive dissonance by using length of relationship as a measurement of effort justification and cognitive dissonance, we see that for the U.S. sample, participants were more likely to increase commitment with their Person B as the relationship lengthened, suggesting that as time progresses in a relationship that has had incidences of hate, people are more likely to possibly justify or explain their ongoing relationship by increasing their level of commitment; and further suggesting that participants do engage in some kind of effort justification or cognitive dissonance when in these relationships, and this can be seen through their degree of commitment.

Surprisingly, the Norwegian sample did not replicate the relationship between length of relationship and relationship quality, providing additional evidence that love and hate may be experienced differently depending on cultural norms (to see a review of the impact of culture on love see Hatfield, Forbes, & Rapson, Reference Hatfield, Forbes, Rapson and Bormans2013). These findings suggest that, for at least some cultures, effort justification and cognitive dissonance can be found in interpersonal relationships with respects to hatred and love. Interestingly, these data also show support for Rempel and Burris’ (Reference Rempel and Burris2005) claim that hate is a motivation for destruction and this motivation negatively impacts the quality of the relationship. Our data suggest that the presence of hatred towards an individual may leave behind issues and feelings of betrayal/hurt/resentment that are difficult to resolve even when the person is simultaneously loved. Future research should consider the importance of assessing interpersonal hatred when examining factors like intimacy, satisfaction, and love.

Limitations

These studies can help explain the impact of hatred on interpersonal relationships, but they cannot tell us how that hate was alleviated or the best way to alleviate that hatred. For many participants in our study, the method they used to stop their hatred was not indicated, and our results could also reflect ineffective methods of handling hate. Additionally, our Norwegian sample was small. Most participants reported that the survey length was too long and stopped filling out the survey halfway. Although the results were in similar directions and support the data in our U.S. sample, the differences in romantic relationships revealed in our Norwegian sample need to be interpreted with caution.

Future research that identifies elements of hatred in interpersonal relationships may provide better understanding of how to help improve relationship satisfaction or indices for dissolution. Gottman (Reference Gottman1993) has already identified contempt as one of the key factors in marital dissolution and this research further bolsters the role that hatred has in affecting relationship quality in various relationships, not just marriage. Better understanding of the differences between hate, contempt, and extreme dislike in future research may help better understand how these emotions and motivations work in interpersonal relationships.