Context of the imperial estate at Vagnari

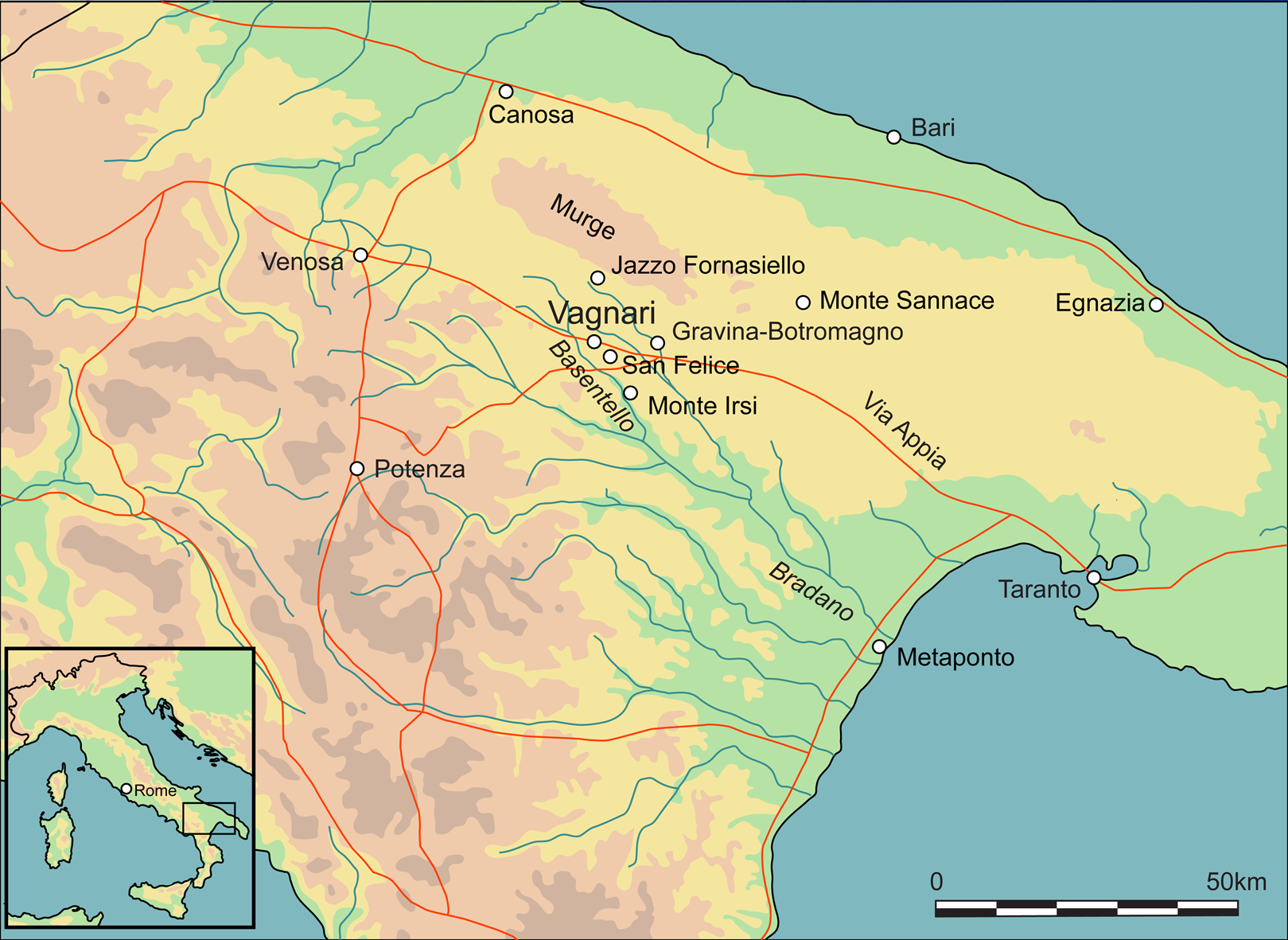

The archaeological site of Vagnari is located in the rolling hills of Puglia (ancient Apulia), just east of the Apennine mountains and about 15 km west of Silvium (modern Gravina in Puglia), a major Iron Age settlement of the Italic Peuceti that was taken and sacked by the Romans in 306 BCE (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 After the Hannibalic wars and the Roman conquest of southeast Italy in the 3rd c. BCE, Rome forged direct links with the region. Many large sites in western Apulia, such as Silvium, and smaller dependent settlements, such as Vagnari, went into decline or were abandoned at this time, and land was confiscated to become Roman state land (ager publicus).Footnote 2 In the wake of the appropriation and exploitation of tracts of Apulian land by wealthy enterprising Romans, however, life at both Silvium and Vagnari resumed in the 2nd c. BCE, but that life was based on rural production, and Silvium never attained municipal status under the Romans.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. Map of southeast Italy (Puglia) showing the location of Vagnari and other sites. (Map by I. De Luis.)

After a hiatus of perhaps a few decades, the Roman emperor, probably Augustus, acquired the land at Vagnari and developed imperial economic assets here in the late 1st c. BCE or early 1st c. CE. Ceramic roof tiles stamped with the name of an imperial slave confirm that this estate was the property of the Roman emperor himself.Footnote 4 The estate, occupying a vast area of at least 25 km2, was nestled between ancient transhumance routes connecting Apulia and Lucania with central Italy, the Via Appia, which linked Roman colonies at Tarentum (Taranto) and Venusia (Venosa) with Rome, and the Basentello river, which flows into the Bradano basin and the Ionian Sea.Footnote 5 We owe the discovery of the Roman village or vicus on the north side of a small ravine on the Vagnari plateau to Alastair and Carola Small, who conducted surveys in the Basentello River valley in 1999 and 2000.Footnote 6 This was by far the largest and one of the richest Roman sites found through fieldwalking and surface collection in the survey area, suggesting that the settlement was the main one on the estate and of central importance.

The landscape in which Vagnari is situated (Fig. 2) lies a considerable distance from Roman urban centers in eastern and coastal Apulia, all of which have been the subject of intense archaeological exploration. Here, the economic, cultural, and social integration in the Roman state is generally better understood than in the regions of western Apulia.Footnote 7 Although the Vagnari estate enjoyed a significant burst of activity in the 1st c. CE, the archaeological evidence retrieved in excavations in the vicus points to the period between the late 1st and the mid-3rd c. CE as the most active and productive phase of occupation in the vicus, with the 4th c. witnessing the decline and abandonment of the settlement.Footnote 8 The longevity of this central settlement of the estate is testament to its importance for the region in the Imperial period.Footnote 9

Fig. 2. The landscape of Vagnari, looking west. The site of the vicus is indicated by an arrow. (Photo by author.)

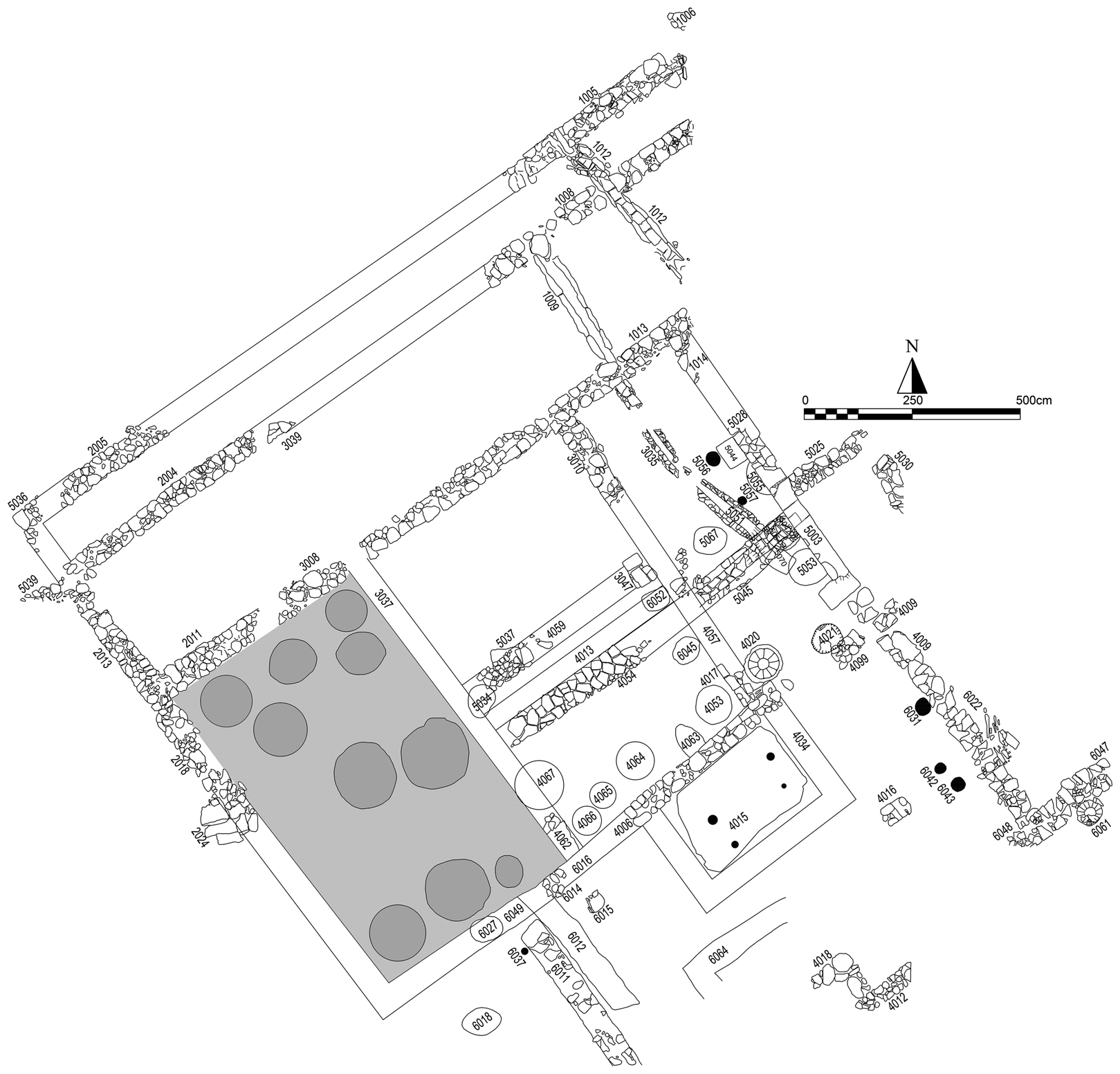

The excavations from 2012 to 2018 uncovered a series of buildings on the northern edge of the vicus, including a long structure possibly used for storing grain, residential quarters, courtyards, and a winery (Fig. 3).Footnote 10 Earlier fieldwork by the University of Edinburgh and the University of Foggia partially uncovered further buildings of uncertain purpose nearby, a large water reservoir, and tile kilns, while the retrieval of hypocaust tiles during survey work hinted at the existence of a bath building in the western part of the site.Footnote 11 Excavations by McMaster University have focused on the Imperial-period Roman cemetery on the other side of the ravine from the vicus.Footnote 12 On the same (south) side of the ravine, a smaller rural settlement grew up after the vicus had been abandoned; this continued in existence until it was destroyed in the late 5th c. CE.Footnote 13

Fig. 3. Vagnari, plan of the excavated remains of the vicus, 2012−18. The cella vinaria and dolia defossa are simplified and highlighted in gray tones. (Plan by J. Moulton.)

Two major sources of revenue for the estate were the cultivation of grain and the maintenance of grazing lands for the flocks of sheep whose wool was used for textile production.Footnote 14 Manufacture of building ceramics, metalworking, and wine and olive oil production were further elements of a diversified economy at Vagnari. However, the lack of large-scale or numerous pressing facilities for oil or wine (as found on senatorial and imperial estates in North Africa), and the size of the winery, suggests that the production of the other obvious staples besides grain and wool was on a relatively modest scale at Vagnari.Footnote 15

The cella vinaria at Vagnari

The existence of the cella vinaria is evidence that vineyards became part of the imperial exploitation of the landscape (Fig. 3).Footnote 16 The winery dates to the 2nd c. CE, as the deposits containing pottery of the 1st c. CE under its floor indicate; in addition, stone-built drains in use in the 1st c. CE were destroyed by the digging of basins to hold the new wine vats in the cella vinaria. Wine production was still an important agricultural activity at this time in coastal Apulia with its Adriatic ports, especially around Brindisi, although the peak of this agricultural product and its export in amphorae had been the 2nd c. BCE, with a reduction in maritime commerce in wine (and oil) in the 1st c. CE.Footnote 17 However, prior to the 2nd c. CE, there is no evidence for wine production at Vagnari. The winery remained in use for about a century.

This modestly-sized storage room was oriented northwest–southeast and measured 5.50 by 8.20 m internally (ca. 45 m2). It is likely that there was an entrance from the outside of the building on the long west wall, but we could not securely determine other ways of accessing the room (Fig. 4). We cannot be certain how the neighboring rooms to the south and east of the cella vinaria were used, but at the end of the 2nd c. CE a new rectangular building up to 30 m in length was built onto the northern side of the winery; this was used, at least in part, for grain storage and very probably a range of other purposes that cannot be determined on the basis of the archaeological remains. The cella vinaria is likely to have been unroofed, as there was no concentration of roof tiles here that are ubiquitous in other roofed areas on the site, and there were no traces of wooden posts supporting an awning or canopy over the dolia, as was the case in the winery at Villa Magna.Footnote 18

Fig. 4. Vagnari, 3D rendition of the buildings and the cella vinaria excavated in the northwest corner of the vicus, view from the west. (Reconstruction by I. De Luis.)

Viticulture required a considerable capital investment, especially if it involved preparing new ground for vines (as must have been the case at Vagnari), which necessitated a waiting period of several years in which the vines needed to be tended by personnel but did not bear fruit and could not yet bring in revenues. Bad years and ruined vintages might put further pressure on the landowner in future years.Footnote 19 The facilities needed for the pressing of grapes, the collection and fermentation of the juice, and the storage of the wine represented additional expenses. Wine storage at Vagnari is evident from the dolia defossa, but the wine production facilities were not revealed in our excavations. No traces of a mechanical press (torcularium), a treading tank (calcatorium), or basins (laci) for collecting the must have been found at Vagnari, although these should have been in a room in the immediate vicinity of or at least close to the cella vinaria. It is possible that a press and tanks were originally connected to the winery but were dismantled and removed once the winery went out of use, or perhaps our trenches narrowly missed the relevant facilities; on the other hand, a mechanical press was not always present in Roman wineries, especially in the more modest ones, and so we cannot be sure that it ever existed here.Footnote 20 Neither can we rule out that the grapes were pressed elsewhere on the estate with the juice being brought to the vicus in wine skins (cullei) to be emptied into the dolia defossa for storage. In this case, the cella vinaria would simply have been the place where the wine was stored and matured.

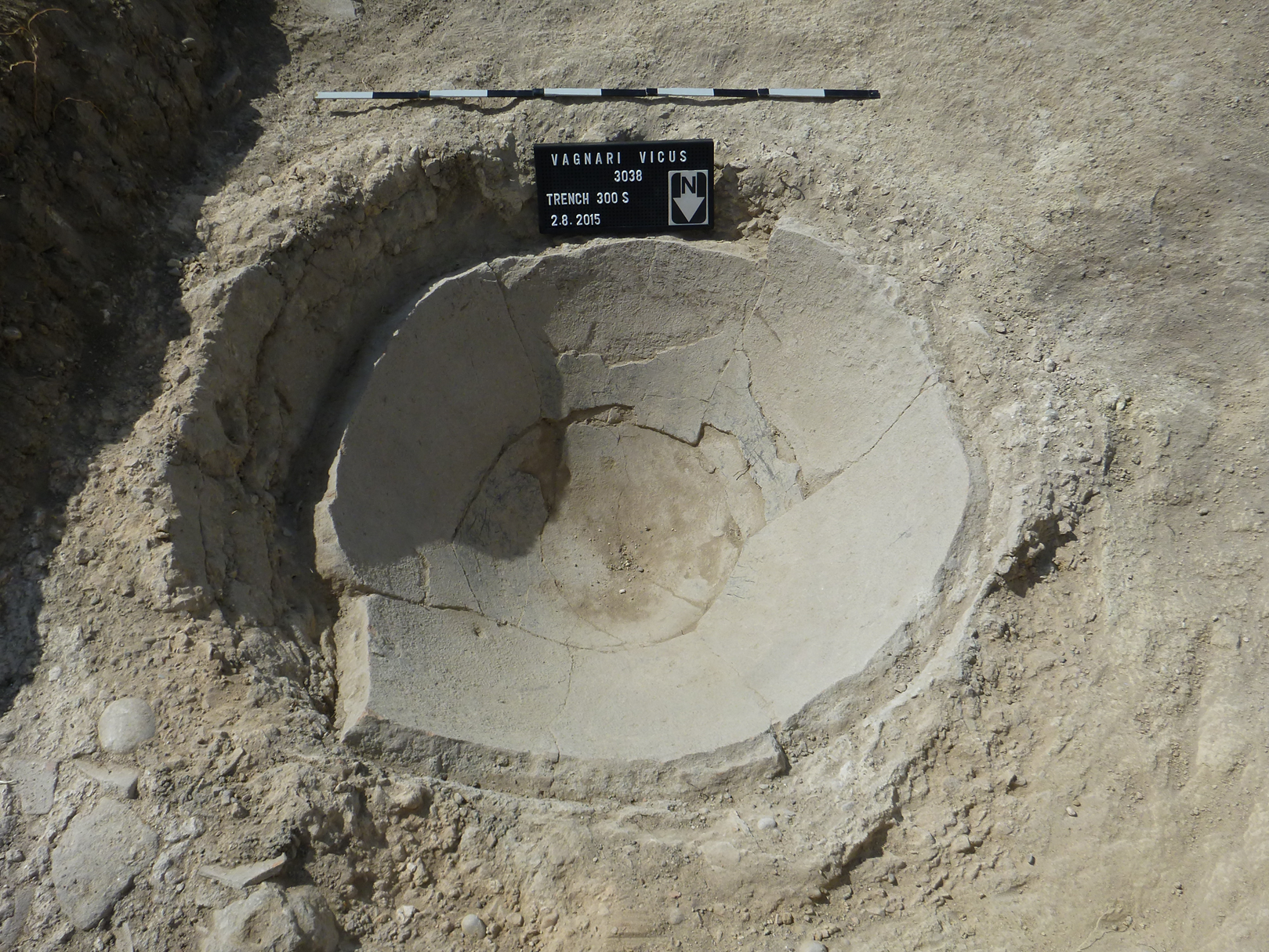

Of the dolia defossa inserted in rows into the mortar floor of the winery, 10 have left traces archaeologically (Fig. 4). There would have been enough space for up to 18 of them if they had been arranged closely in three rows, but the natural bedrock here was not very deep and this may have prevented the insertion of dolia in some spots or limited the depth of the basins dug for them. Some of them might also have been removed in antiquity, without leaving a trace for us to discover. Each dolium was buried up to its shoulder in a circular depression up to 65 cm deep that was lined with smoothed mortar, the mortar lining possibly insulating the dolia from any extremes in temperature, as well as ensuring a snug and stable support to keep the vessels upright (Figs. 5–6).Footnote 21

Fig. 5. Vagnari, excavating the mortar-lined basins for the dolia inserted into the mortar floor of the winery. (Photo by author.)

Fig. 6. Vagnari, one of the dolia defossa, the lower third of which is still in situ in its basin. (Photo by author.)

Because of their fragmentary state, it is difficult to say whether individual dolia defossa in the Vagnari winery might have been replaced at any point, whether they had cracked, burst, or leaked, or whether they remained in place until the cella vinaria went out of use at the end of the 2nd c. or in the early 3rd c. CE. It is unclear how long dolia defossa might last. Peña recently suggested that such structures may have been in use for 20 or 30 years, or even longer, as is the case in the Caseggiato dei Doli at Ostia, where they appear to have been used for 40–70 years.Footnote 22 More recent ethnographic parallels in the Mediterranean point to the use-life of wine storage jars of more than 100 years.Footnote 23 Certainly, cracks in dolia often necessitated repairs consisting of tenons, clamps, plugs, or staples of lead or lead alloy.Footnote 24 Cato (Agr. 39.1–2) specifically recommended lead as an ideal material with which to mend wine vats, and this was one of the tasks farm workers should do “when the weather is bad and no other work can be done.” We found no lead repairs in place in any of the dolium sections or fragments at Vagnari, however, though this could be because the lead had been removed and remelted for another purpose when the dolia went out of use.Footnote 25

When the winery was abandoned, some dolia were either removed completely, to be reused elsewhere, as in the Villa of Augustus at Somma Vesuviana, or smashed into pieces to be used secondarily as building material, as they were at the villa of Settefinestre.Footnote 26 It is not uncommon in cellae vinariae to see backfilled circular depressions left in the ground from the complete removal of dolia, and this was found to be the case in places in the winery at Vagnari.Footnote 27 However, the lower portions of dolia were still in situ in two of the mortar basins. The large quantities of sherds from smashed dolia in the relevant backfills suggest that the vessels in these cases might already have been broken or that they broke when someone attempted to remove them, the debris then being dumped back into the basin.

The dolia defossa

The Vagnari dolia defossa were primarily globular or ovoid, with a small flat bottom of ca. 25–30 cm in diameter, although a couple appear to have had a slightly larger base (Figs. 5–6). They correspond to Carrato's “globulaire” and “conique” types, of which we have complete examples from the Tiber Valley and from Minturnae (Figs. 7–8).Footnote 28 A large body sherd of a cylindrical dolium with an angular carinated edge at one end was also retrieved; this had a maximum body diameter of ca. 1.2 m.Footnote 29 The walls of the dolia are up to 7 cm thick, and it is clear that the vessels were coil-built. The top vertical edge of the remaining lower third of one of the dolia is slightly undulating, preserving the indentations made by the fingers of the potter to create a surface onto which the next coil above would better adhere. A recent examination of dolia in Regio I, Insula 22, in Pompeii has confirmed that these vessels were coil-built, the transition points where the coils met still being easily visible.Footnote 30 A similar undulating break between two coils has been noted on Roman dolia in Gallia Narbonensis.Footnote 31 Such joints often cracked when the dolium was drying, during firing, or at a later stage during use.

Fig. 7. A conical dolium from the Tiber Valley, photographed outside the Baths of Diocletian in Rome. (Photo by author.)

Fig. 8. A globular dolium from the Garigliano Valley, photographed in the archaeological park at Minturnae. (Photo by author.)

Only one fragmentary ceramic lid (operculum) was retrieved. Dolia usually had two lids: the operculum and a domed ceramic lid (tectarium) on top of that to further protect the contents from rain or sun, as is apparent in the cella vinaria of the Villa Regina at Boscoreale (Fig. 9).Footnote 32 No trace of a tectarium was identified at Vagnari.

Fig. 9. Villa Regina at Boscoreale. Each wine storage vat was covered with two lids, an operculum and a tectarium. The latter are leaning against the wall in the background. (Photo by author.)

In the absence of any workshop data recorded in the Roman period, more recent production of dolia can put into perspective how work-intensive and time-consuming the making of such storage vessels was in Antiquity. There are pertinent ethnographic data on the production of enormous dolia in Spain (tinajas) and in Greece (pithoi) in the 19th and 20th c.Footnote 33 These vessels could take between 10 days and 2 months to dry, in advance of firing in specially-built kilns at 900–1000°C for 8–24 hours, depending on the size of the vessels.Footnote 34 In a modern workshop near Florence, each reproduction dolium with a 500-liter capacity is slowly built, coil by coil, from the bottom up over a period of 15–20 days; another month is then needed to dry them in preparation for firing at 1000°C in large kilns for three days.Footnote 35 Recent experimentation in the making of a dolium in France involved the drying of the complete vessel for five months before it was fired in the kiln.Footnote 36

Columella (Rust. 12.18.5–7) recommended that dolia defossa for wine be relined with pitch 40 days prior to the grape harvest, and this was repeated annually. The Vagnari dolia had been relined multiple times internally with layers of pine pitch, as a residue analysis by Matt Stern from the University of Bradford revealed (unpublished), although we cannot say precisely how many times it had been reapplied. The pitch coatings are a reliable confirmation that the original contents of the Vagnari dolia consisted of wine, as pitch was the normal internal surface treatment for vats containing wine, unlike oil dolia, which could be coated with wax or gum.Footnote 37 According to Cato (Agr. 23.1), coating the dolium interior with pitch was a task to be done on rainy days – presumably to keep workers busy. The degraded Pinaceae resin was found to be present only on the interior surfaces of the Vagnari dolia; it acted so effectively as (what today we would call) a waterproofing agent that it completely prevented the migration of any traces of wine into the ceramic walls.

Storage capacity of the Vagnari winery

The cella vinaria at Vagnari is comparable in size to the wine-storage rooms of private farms in the Vesuvius region, such as the Villa Carmiano at Stabiae (6 × 8 m, with at least 12 dolia, and possibly 15) built in the late 1st c. BCE, but it was much smaller than a 2nd-c. CE cella vinaria at the rural villa of San Giusto in Puglia (6.10 × 14.40 m, with 26 dolia).Footnote 38 Calculating the storage capacity at Vagnari is challenging because few dolia defossa were still in situ. The difficulties are compounded by the fact that none of the dolia is intact; moreover, the dolia, the basins, and the robbed-out dolium holes are not all the same size. However, there are some useful measurement data. One of the globular dolia had a maximum preserved internal body width of 0.96 m, suggesting that it may originally have had an internal diameter of at least 1 m or 1.10 m at the widest point higher up the vessel. One of the mortar basins had an internal diameter of 1.40 m, so the external diameter of the globular dolium in it cannot have been very much smaller. The fragmentary dolium lid with a diameter of 0.52 m suggests that at least one of the dolia had an internal rim diameter of about 0.42 m, as the lids cover the mouth of the vessel but never extend to the outer edge of the rim. The Vagnari dolia probably fell within the range of those from the Pisanella villa at Boscoreale, which were 1.36 m tall and had a maximum internal diameter of 1.26 m, or of those at the villa of N. Popidius Narcissus Maior in Scafati, which had an internal rim diameter of 0.42 m and an internal body diameter of 1.10 m.Footnote 39

There is great variability in the capacity of dolia defossa in wineries throughout Italy, ranging, for example, from those containing 392.50 l at the Villa Regina at Boscoreale, through smaller and larger dolia in Regio I, Insula 22, at Pompeii holding 133–734 l, to two types holding 480 l or 790–1730 l at San Giusto in Puglia.Footnote 40 There is also great variability in the annual yield stored in cellae vinariae. The Pisanella villa at Boscoreale had 72 dolia defossa, each with a capacity of 1,000–1,100 l; the yield of wine annually would therefore have been about 75,000 l (750 hl).Footnote 41 Much more modest was the winery of C. Olius Amplicatus in the southeast suburbs of Naples; here, 26 dolia defossa with a capacity of 500–700 l could store an annual yield of 17,000 l (170 hl).Footnote 42 Some variability existed at Vagnari as well, given the different sizes of dolia, but the fragmentary nature of the vessels prohibits absolute precision in determining specific capacities or an annual yield. A cautious estimate of 500 l on average for the 10 dolia defossa would give us a modest 5,000 l (50 hl) per annum; if there were originally 18 dolia, the yield could have been an only slightly less modest 9,000 l (90 hl) annually.

Taking André Tchernia's estimate for a range of yields of 15–30 hl per ha on Roman estates, the vineyard at Vagnari would have been between approximately 1.6 and 6 ha in size, or between 6.4 and 24 iugera, well below the standard vineyard of 100 iugera described by Cato, although Cato's hypothetical vineyard could have been interplanted with other vegetation as well.Footnote 43 Of course, the cella vinaria at Vagnari might have been used only for a portion of the wine from a vineyard which could have been much larger, the rest being stored somewhere else on the site and still awaiting discovery. That smaller vineyards could produce large amounts of wine is demonstrated by the commercial vineyard inside the walls of Pompeii (Regio I, Insula 5), where a property of only 0.65 ha (just over 2 iugera), planted with up to 4,000 vines, could yield up to 10,000 l, to judge by the 10 dolia defossa, each with a capacity of 1,000 l, in the small cella vinaria; in this case, the extraordinarily fertile Vesuvian soil was probably responsible for the high productivity.Footnote 44 According to Girolamo De Simone's calculations, the Vesuvian region could easily have produced four times the local demand for wine for its population, despite the fact that the farms were usually quite modest.Footnote 45

If we take the daily ration of one sextarius (= 0.546 l) per day per person, following some Roman historical and agricultural sources, 5,000 l would be sufficient for roughly 25 people; a potential yield of 9,000 l would therefore suffice for 45 people.Footnote 46 This is not a large consumer group. In its size and capacity, the Vagnari winery resembles those of the modest family farms at Stabiae-Carmiano (6 × 8 m, with 12 or perhaps 15 dolia; yield of ca. 7,000 or 9,000 l) and Boscoreale-Villa Regina (6.60 × 8.47 m, with 18 dolia; yield of ca. 10,000 l).Footnote 47 Moreover, if we accept the consumption of one sextarius per person at those two farms, the amount of wine grown would suffice for an equally modest group of 35 or 45 people at Stabiae-Carmiano or for 50 people at Boscoreale-Villa Regina.

These rough comparisons related to vineyard size and daily consumption raise the question whether the winery at Vagnari was perhaps only one of others in the vicus or whether it was located where it was to service just a section of the population of the estate, maybe even just the people in the household of the estate's administrator(s). Without knowing the total population of the estate, and without excavating the vicus in its entirety, this remains unclear. At any rate, the quantities of wine stored at Vagnari do not support the idea of surplus production for sale and export.

Provenance of the dolia defossa made for Vagnari

The fabric of the dolia from Vagnari consisted of a distinctive orangey-red clay with black, glassy particles and reddish-brown grit fragments as temper; it was distinctively different from that present in the other ceramics from the site and clearly different from the building ceramics made of locally-sourced clay. The dolium fabric also differed from that of the surviving dolium lid fragment, which was made of a fairly fine buff clay, suggesting a different source. It is not unusual for dolia and lids to be made of different clays and in different workshops, as they were in Gallia Narbonensis, where analysis shows that some lids were made in Rome but that the vessels were local products.Footnote 48 That is also the case for the dolia on board the Grand Ribaud D wine tanker that sank off the south coast of France at the very end of the 1st c. BCE.Footnote 49 This makes sense, as almost any potter anywhere could make a lid, but only specialist workshops could manufacture the dolia. Furthermore, lids could be replaced easily at any time and be sourced from any workshop. A large, almost complete mortarium at Vagnari, which has not yet been analyzed, has a fabric that is visually very similar to that of the dolia defossa, perhaps pointing to the same place of manufacture, as different types of heavy ceramics were often produced together in extensive workshops or figlinae, be it in Latium, Apulia, or Istria.Footnote 50

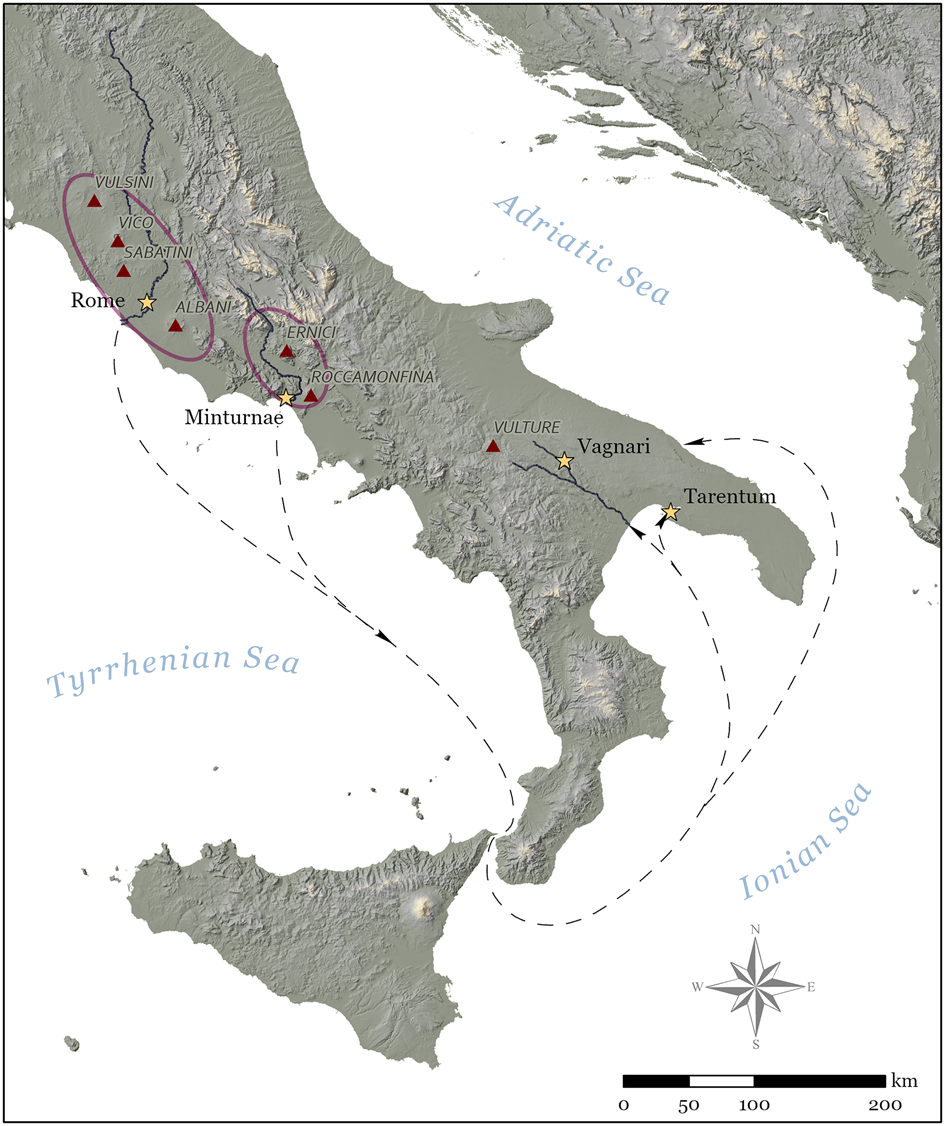

An archaeometric analysis of the dolia defossa was conducted to determine whether they were made at Vagnari or anywhere else in the region, or whether they were sourced from figlinae located further away. Ten samples of dolia were subjected to mineralogical-petrographic and chemical analysis; the detailed results of the scientific analyses have been published elsewhere.Footnote 51 The physically closest source of volcanic material that could have been used to temper the clay of the dolia at Vagnari is Monte Vulture, about 80 km northwest of our site, but the results show that this is not the source; Campanian volcanic products from the Phlegraean Fields, Ischia, and Somma Vesuviana can also be distinguished from the Vagnari material. Instead, the analysis strongly supports the hypothesis of provenance from the wide volcanic region which covers most of the central Italian (Tyrrhenian) west coast, from the Vulsini Mountains and Bolsena Lake areas southward along the Tiber River toward Rome, and further down to the area around the Garigliano (ancient Liris) River basin, which forms the border between Latium and Campania. The dolia, therefore, were made of clay that came from the Tyrrhenian coast of Latium and Campania, either from the Roman Magmatic Province (with Rome as a focus in the Tiber Valley) or from the Ernici-Roccamonfina Magmatic Province (with Minturnae as a key site; Fig. 10).Footnote 52 The better match for the temper and clay of the Vagnari dolia is the region around Rome, but the hinterland of Minturnae cannot be ruled out completely as the source of the materials in the vessel fabric.

Fig. 10. Map showing the volcanic provinces of central Italy and relevant sites: the Roman Magmatic Province, with Rome at its center; and the Ernici-Roccamonfina Province, with Minturnae as a key site. The possible routes for transporting the dolia defossa to Vagnari are indicated. (Map by H. Goodchild, with data from Jarvis et al. Reference Jarvis, Guevara, Reuter and Nelson2008 and the Geoportale Nazionale.)

Unfortunately, no stamps have survived on the dolia at Vagnari, so epigraphically we cannot connect any of the known manufacturers from the Rome or Minturnae regions with these vessels.Footnote 53 The urgent need for the archaeometric analysis of dolia to determine their source is quite apparent and the issue has often been raised, although very few vessels have been studied in this way.Footnote 54 Only two archaeometric studies that have attempted to identify the source of raw material for dolia have been conducted: one at a Roman pottery production site at Scoppieto di Baschi, east of Lake Bolsena in the Tiber Valley; and a second at a Roman villa at San Giovanni on the island of Elba. In the first case, at Scoppieto, Late Republican and Early Imperial dolia and mortaria were manufactured using raw materials sourced from the Vulsini volcanic district, on the eastern edge of which Scoppieto lies.Footnote 55 One might expect Tiber Valley agricultural estates to use dolia made locally, but this might not hold true for Rome and its suburbium, as is indicated by the finds of dolia defossa at two villas in the northern suburbs of Rome (Cecanibio and Prima Porta) bearing the names of manufacturers known to be based in Minturnae (the Codonius and Piranus families).Footnote 56 The second archaeometric study and source analysis, on Elba, concerns two dolia defossa from a Roman wine cellar of the villa at San Giovanni, the results revealing that they were made in figlinae either in the Tiber Valley or at Minturnae.Footnote 57

Systematic archaeometric studies of dolia found in central Italy (and beyond) might demonstrate that the producers in the Tiber and Garigliano Valleys supplied a much larger area than imagined. A study of the pastes used in making dolia defossa in Gallia Narbonensis, for example, has shown that one workshop or group of workshops had a diffusion zone extending over nearly 400 km, from Lyon to Narbonne, through Arles and the outskirts of Marseille, corresponding to almost the whole province from the 1st to the mid-2nd c. CE.Footnote 58 The fabric analysis thus reveals both production and diffusion. This research on the Vagnari dolia defossa is therefore an important step in understanding the organization of the dolium “industry” in central Italy, how the vessels were deployed, and the routes taken to transport them to their destinations. The imperial estate at Vagnari is the first site on the other side of Italy to provide evidence for dolia defossa from the Tyrrhenian coast, but this may be related to the special circumstances of imperial ownership of properties, as discussed in the following sections.

Opus doliare and wine production in the Tiber and Liris-Garigliano Valleys

Two regions in the volcanic zones of Latium (Rome and the Tiber Valley) and on the Latium–Campania border (Minturnae and the Garigliano Valley) are indicated as the potential sources for the dolia defossa at Vagnari, but it is difficult to say with absolute certainty in which of them the vessels were made. For this reason, both landscapes will be discussed, and their historical and economic backgrounds in regard to viticulture and the production of heavy ceramics will be contextualized, before moving on to a specific discussion of the economy of the patrimonium.

The Tiber Valley

The production of wine in the hinterland of Rome was substantial during the Republican and Imperial periods.Footnote 59 Both the archaeological remains and the surviving texts of Roman agricultural writers who owned land in the region attest to this. One of these vineyards, about 16 km from Rome, near Nomentum, acquired in the mid-1st c. CE by the writer Seneca, was particularly productive, yielding “piles of grapes” and having been cultivated to “an almost incredibly wonderful condition.”Footnote 60 The production of wine may have been preferred as a form of elite economic investment in this region, but a fragmented landowning pattern is evident. The individual production sites are relatively modest and only a small number of press sites have been discovered thus far.Footnote 61 As appears to have been the case in the Vesuvius region, estates in the hinterland of Rome might have been small, but the land was heavily exploited to make it productive as a whole.Footnote 62

The relatively low number of locally produced wine amphorae in the immediate hinterland of Rome and in Rome itself has been remarked upon; this primarily has to do with the use of perishable materials, such as skins or perhaps barrels, rather than amphorae, to transport the wine from the estates to the consumers in Rome.Footnote 63 Wine from further afield in the upper Tiber Valley, on the other hand, was shipped downriver to Rome in amphorae.Footnote 64 One of these wine producers was Pliny the Younger, whose villa in Tuscis at San Giustino in the territory of Tifernum is known archaeologically, and whose amphorae bear his name stamp.Footnote 65 Excavations at this site revealed an estate of the Augustan period belonging to a member of the senatorial elite (M. Granius Marcellus), later transferred in ownership in the Julio-Claudian period to the emperor, and subsequently owned by Pliny the Younger. It had wine-making facilities that were expanded under Pliny, thereby enhancing the productivity of the estate. Unfortunately, we have no information or truly conclusive evidence for the place of manufacture of Pliny's dolia or those from other estates in the Tiber Valley, although the earlier cited study of dolia and mortaria made in the kilns at Scoppieto di Baschi indicates the use of raw materials from the Vulsini volcanic zone.Footnote 66 The importance of the Tiber as a major transportation route for agricultural products, such as wine in amphorae, and for the dolia produced for the wineries on various estates throughout the river's valley is evident, although there might have been seasonal and other constraints on the use of the river.Footnote 67

The changes in ownership of some properties, such as that at San Giustino, indicate that the emperor and the imperial family acted as prominent landowners and producers here. The establishment of imperial properties and elite residences around Tibur, in the Alban hills, and on the coast of Latium south of Rome goes back to the Augustan period, and this trend continued throughout the 1st, 2nd, and early 3rd c. CE.Footnote 68 One well-known imperial residence southeast of Rome is the Villa Magna, inhabited and described by the emperor Marcus Aurelius. Luxurious as it may have been, it was also a working estate that produced wine, evidence of which was provided by recent excavations in the cella vinaria, which contained 38 dolia defossa.Footnote 69 The emperors were “economic actors” in producing wine not only near Rome but in various parts of Italy; but their part in producing the ceramic equipment for wine making is particularly important in the context of Vagnari.Footnote 70

More archaeometric studies of dolia from wineries around Rome need to be conducted to ascertain if they are Tiber Valley products or if they might be from places further afield, like the dolia from Minturnae in villas at Cecanibio and Prima Porta in the northern suburbs of Rome.Footnote 71 That said, there is a considerable amount of epigraphic and historical evidence for the production of dolia and other heavy ceramics in Latium. We know that brick, tile, dolia, mortaria, and even terracotta sarcophagi – opus doliareFootnote 72 − were manufactured in vast quantities in production centers around Rome and all along the Tiber River: centers that were owned by the Roman senatorial elite, many of them gradually being transferred to imperial ownership by bequest or confiscation.Footnote 73 By the late 2nd or early 3rd c. CE, in fact, the majority of these figlinae and properties (praedia) were in imperial possession.Footnote 74 The emperor and the imperial family commanded a considerable property portfolio which included land with various assets such as clay deposits. To cite just one prominent example, Domitia Lucilla Minor, wife of Marcus Annius Verus and mother of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, inherited and owned extensive clay pits, employed various brickmakers, and was a major player in the production of opus doliare.Footnote 75 One of the production areas of this enterprise, a site with two tile kilns, was excavated about 90 km north of Rome at Mugnano in Teverina, località Rota Rio.Footnote 76

The Liris-Garigliano Valley

Moving south to the border between Latium and Campania, the Roman colony at Minturnae owed its prosperity to its location on the Via Appia and at the mouth of the Garigliano River, as well as to the rich agricultural land and forests in its hinterland.Footnote 77 The far-flung connectivity of Minturnae and the economic activities channeled through it, however, are probably still underestimated.Footnote 78 Numerous slaves and freedmen of known Minturnaean families are attested on Delos, for example, demonstrating the involvement of businessmen and merchants from the region in the eastern Mediterranean.Footnote 79

Archaeological discoveries in the territory of Minturnae, Fundi (to the north), and Sinuessa (to the south) demonstrate that as early as the 3rd c. BCE the main economic relevance of the region was in the production and diffusion of Italian wine.Footnote 80 Horace (Epist. 1.5.5) thought that the wine from “between marshy Minturnae and Mount Petrinum near Sinuessa” was not outstanding, but the wine of the neighboring Ager Falernus between Sinuessa and the Volturno River in northern Campania was highly prized.Footnote 81 Some estates around Minturnae and in the region were owned by the Late Republican elites of Rome, including some members of Sulla's and Pompey's families; with the emergence of commercial wine production, it can be assumed that many of them participated in this activity.Footnote 82 One of the Roman notables involved in viticulture and commerce in wine was L. Cornelius Lentulus Crus, consul of 49 BCE, an elite landowner in the Minturnae region.Footnote 83

In the Early Imperial period, we have less evidence for named proprietors of estates, although it seems that senatorial families or people connected to the imperial court may have been accumulating land after the civil wars.Footnote 84 For example, one of these high-ranking individuals who owned properties near Minturnae was C. Laecanius Bassus Caecina Paetus, consul suffectus in 70–71 and proconsul of Asia in 80–81 CE.Footnote 85 Some elite estates here became part of the imperial patrimony.Footnote 86 A well-known member of the imperial family in the region in the 2nd c. CE was Matidia Minor (or Mindia Matidia), an aunt of Antoninus Pius and a frequent benefactor not only of Suessa Aurunca but also of Minturnae; her properties were inherited by Marcus Aurelius at her death around 161 CE.Footnote 87 She also owned brickworks in Rome, and she was one of several landowning elites with close ties to the imperial house and with businesses in Latium and Campania and beyond.Footnote 88

It is clear from historical sources and archaeological exploration that the shipbuilding industry flourished on the Garigliano River. Remains of shipsheds have been located on a 200 m-long stretch of the riverbank at Minturnae, and there is also the funerary monument of an architectus navalis.Footnote 89 Maritime mercantile activity and shipbuilding at the port of Minturnae were closely tied to the production of another category of dolia, the gigantic transport vessels containing Italian wine with a capacity of up to 3,000 l.Footnote 90 These enormous dolia were transported in bulk on specially constructed tanker ships sailing around the western Mediterranean (Fig. 11).Footnote 91 The gens Pirana, in particular, is attested in the business for a few generations, from the late 1st c. BCE to the mid-1st c. CE; they made both the transport dolia for ships and the dolia for use in wineries, presumably in the same kilns.Footnote 92

Fig. 11. Gigantic transport dolia from wine tanker ships, photographed at Ostia Antica. The stamps on the dolia identify them as products of Minturnae. (Photo by author.)

From the early 1st c. BCE, dolia were part of the repertoire of Minturnaean figlinae (Fig. 8), as indicated by a vessel of that period from Minturnae bearing a stamp of the slave Dem… Coionius.Footnote 93 And the Codonii and Pirani figlinae at Minturnae made dolia defossa that were acquired by villa owners north of Rome, as we have seen.Footnote 94 However, although we have considerable information about the production sites and kilns used for making amphorae in the territory of Sinuessa and Minturnae, no remains of dolium workshops or kilns have yet been located archaeologically.Footnote 95

Opus doliare and the imperial patrimonium

The fabric analysis of our dolia has revealed a connection between Vagnari and areas in the Tiber Valley or in the Garigliano River basin. In the following, the significance of this connection in the context of the economy and the imperial patrimonium is explored. The most pressing and interesting questions are: Why were vessels from such a distant source acquired for an imperial estate in southeast Italy? And how did these vessels get to Vagnari?

Normally, in regions where Roman wine was produced in significant quantities, the kilns and workshops for dolia were located at or near the harvesting sites and estates. This is the case, for example, at Giancola near Brindisi in Puglia.Footnote 96 Likewise, at the villa of Saint-Bézard at Aspiran in the Hérault region of southern Gaul, the wine produced in its vineyards from the 1st to the 3rd c. CE was stored in dolia that were made in workshops and kilns on the estate.Footnote 97 However, the emperor – or, rather, the imperial procurator responsible for the estate at Vagnari – did not procure dolia for the new winery in the 2nd c. CE from any local providers in Apulia.Footnote 98 Elio Lo Cascio has championed the idea that the emperor or his representatives behaved very much like a private landowner in the running of estates.Footnote 99 If this were the case, however, we might expect the emperor to supply his Apulian estate at Vagnari with products locally made, as private vintners in Apulia did, and to conform with the normal market scenario (as far as we understand it) in terms of balancing investment and expenditure against profit. Using suppliers for essential (and specialist) equipment from the Tyrrhenian coast on the other side of the peninsula makes little sense in this context and it seems excessive and unnecessary, unless there were particular reasons to do so.

It is proposed here, therefore, that the emperor and/or his procurator did not use private providers for Vagnari because they drew on figlinae that belonged to the patrimonium Caesaris, and the dolia produced therein were imperial property.Footnote 100 This can be argued very plausibly for Rome and the Tiber Valley, where various clay pits and workshops are known to have been owned by the imperial family.Footnote 101 We are less well informed archaeologically or epigraphically about figlinae for opus doliare and about the imperial ownership of such workshops in the Liris-Garigliano River basin, but that does not mean that figlinae belonging to the patrimonium did not exist here. Dolia, whether from the Tiber Valley or from Minturnae, were not always stamped, so the lack of stamps recording imperial ownership cannot be interpreted as a sign that the imperial fiscus was not a participant in this form of production.

It would have required considerable effort to get the dolia from the west coast of Italy to Vagnari, and it is particularly striking that this was the case because the winery at Vagnari was a decidedly modest one, likely only producing or storing sufficient wine for the estate inhabitants. The act of outfitting the winery this way, however, might be explained as a decision of the imperial administration to move equipment from one property in the emperor's possession to another. Transfers of property assets from one imperial estate to another might have represented a kind of economy on the part of the administration of the fiscus, if it sought to avoid spending cash outside the patrimonium. Although it might seem irrational not to make use of producers nearby who could provide the needed ceramic vessels at a reasonable price, the imperial fiscus may have sought to exercise a degree of control by keeping money within its own system.Footnote 102

So perhaps an imperial estate like Vagnari, which primarily produced grain, exchanged this with properties elsewhere in western Italy that produced other needed commodities, such as dolia. Apulia was considered an exporter of high-quality grain in the 1st c. BCE and the 1st c. CE, and in Late Antiquity the region supplied not only Rome but also Gaul.Footnote 103 Although we hear nothing about Apulian grain in the 2nd c. CE, when the dolia were being brought from the Tyrrhenian coast to Vagnari, it clearly was being cultivated and stored in the vicus; there is also no reason to think that this grain could not have been transferred by the emperor to recipients on other properties in his possession. Another plausible exchange item might have been wool, a further mainstay of the Vagnari imperial estate. The emperor owned flocks of sheep that were driven regularly between Apulia and Samnium (though we cannot say for certain that these were driven along the tratturi directly near Vagnari). Additionally, a wool-worker who was an imperial slave is attested epigraphically in the territory of other Apulian imperial properties near Venosa and Canosa.Footnote 104 Perhaps the transfer of goods within the patrimonial system can be understood as an aspect of what we might term the internal economy of imperial properties.

Given the difficulty of transporting such bulky goods by land over the Apennines, it seems likely that the dolia destined for Vagnari were shipped by sea.Footnote 105 Transporting them to the estate overland would have involved several wagons and teams of oxen (or other draft animals) and men; shipping them would have been more efficient, and perhaps all 10 (or 18) dolia would have fit on one or two ships. Water routes, in any case, would have been the preferable solution.Footnote 106 The ship(s) might have sailed around the tip of the Italian peninsula − from Ostia/Portus or Minturnae − either to one of the ports on the Adriatic coast or to the coast of the Ionian Sea and upriver as far as possible, or to the harbor at Tarentum, the starting point of the Via Appia (Fig. 10). The last leg of the journey to Vagnari would have been overland. Either of these routes from the western Roman harbors meant that the dolia would travel more than 1,000 km, reaching their destination in hardly less than 10 days. This may seem a noteworthy situation to us, but for the emperor, the “beneficent manager of the whole Italian landscape,” the production, management, and movement of commodities from one imperial property to another, whether near or far, may have been routine.Footnote 107

Acknowledgments

I thank Alastair and Carola Small for their insights and willingness to discuss (repeatedly) the archaeology of Roman Apulia with me. I have benefited enormously from conversations with Dennis Kehoe on aspects of the imperial economy and Roman legal sources, and I am very grateful to him for this. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. I should like to thank my York colleague Helen Goodchild for taking the time to make maps for me, and I also thank Jonathan Moulton and Irene De Luis for their expert and quick production of maps, plans, and 3D reconstructions. Finally, I am grateful to my two human scales in Figs. 7–8, Susan Russell and Angela Kalinowski.

Funding statement

The research on Roman dolia was carried out in good part at the British School at Rome, with a grant from the British Academy, and I am grateful to both institutions.