Garifuna (cab, ISO 639-3) is spoken by the Garifuna people (previously known as Black Caribs and currently also by the plural Garinagu – Cayetano Reference Cayetano1993), who reside along the Caribbean coast of Central America in communities in Belize, Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua, as well as in a large immigrant population in the United States. Population estimates in the literature for Garifuna speakers worldwide vary widely, but Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald, Dixon and Aikhenvald1999: 72) estimated between 30 and 100,000 speakers of the language. The latest census in Belize reports a population of 19,639 people who report at least one of their ethnicities as Garifuna and 8,442 people who report speaking Garifuna well enough to hold a conversation (Statistical Institute of Belize 2010 census).

Garifuna is the only Arawak language currently spoken in Central America, and the language with the largest population of speakers in the Arawak family, which is itself the largest language family in South America (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald, Dixon and Aikhenvald1999: 65). Garifuna is considered to be part of the North Arawak branch (Taylor Reference Taylor1977) which also includes Lokono/Arawak, Guajiro and Taino. The closest relative of Garifuna in the North Arawak branch is the more recently extinct Island Carib (Iñeri), documented by Taylor on the island of Dominica early in the 20th century.

A great deal of the linguistic description of the structure of Garifuna comes from Douglas Taylor, whose description is based on the language of speakers in Hopkins Village, on the southern coast of Belize (see map in Figure 1), in the late 1940s (Taylor Reference Taylor1951, Reference Taylor1955, Reference Taylor1956a, Reference Taylorb, Reference Taylor1958, Reference Taylor1977). This illustration draws from the work of Douglas Taylor, as well as E. Roy Cayetano (Cayetano Reference Cayetano1992, Reference Cayetano1993). Others who have described various aspects of Garifuna morphology and syntax include Hagiwara (Reference Hagiwara1993), Munro (Reference Munro, Hill, Mistry and Campbell1998, Reference Munro, Austin and Simpson2007), Ekulona (Reference Ekulona2000), Devonish & Castillo (Reference Devonish and Castillo2002), De Pury (Reference De Pury2003, Reference De Pury, Chamoreau and Lastra2005) and Escure (Reference Escure, Escure and Schwegler2005), all working with consultants from Belize. Suazo (Reference Suazo1991a) and more recently Haurholm-Larsen (Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016) and Quesada (Reference Quesada2017) base their descriptions on varieties spoken in Honduras. There is a small collection of literary work in Garifuna, including Lewis (Reference Lewis1994) and Suazo (Reference Suazo1991b), which were also consulted. This illustration is based on the speech of Zita Castillo-Muhsin, a woman who was born in the late 1970s in Hopkins Village, Belize (Figure 1) and emigrated to the USA as an adult. The speech that is the basis for the discussion of inter-speaker variation comes from interviews conducted in 2007–2008 with multiple speakers in Hopkins (Ravindranath Reference Ravindranath2009).

Figure 1 Map of Belize and surrounding parts of Central America, with Hopkins indicated. (Map created by the author using tableau.com.)

While Garifuna is not critically endangered in all of the communities where it is spoken, and there are active efforts for language planning, revitalization, and maintenance (Langworthy Reference Langworthy, Burnaby and Reyhner2002, Cayetano & Cayetano Reference Cayetano, Roy Cayetano and Palacio2005) the communities in which it is spoken are becoming more heterogeneous, and in most of the Garifuna diaspora language shift to English (US, Belize), Kriol (Belize), and Spanish (Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua) at the expense of Garifuna is ongoing. In Belize, only in the village of Hopkins, which has a total Garifuna speaker population of less than 1000, are there still a significant number of child speakers, yet preschool-aged Garifuna monolingual children are no longer as common as they recently were (Abtahian Reference Abtahian2017). In addition to a broad overview of the phonemic system of Garifuna, we also attempt to provide more detail on some aspects of sociolinguistic variation. As language use in different domains diminishes alongside language shift, stylistic variation is apt to become more limited, adding to the urgency of documenting natural texts.

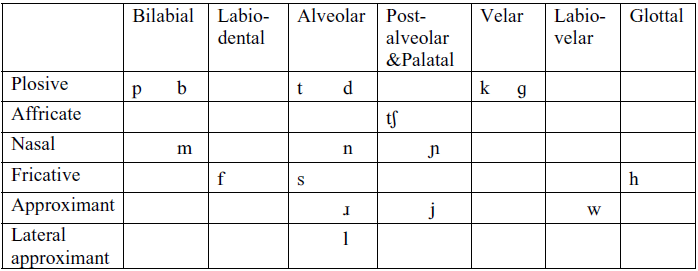

Consonants

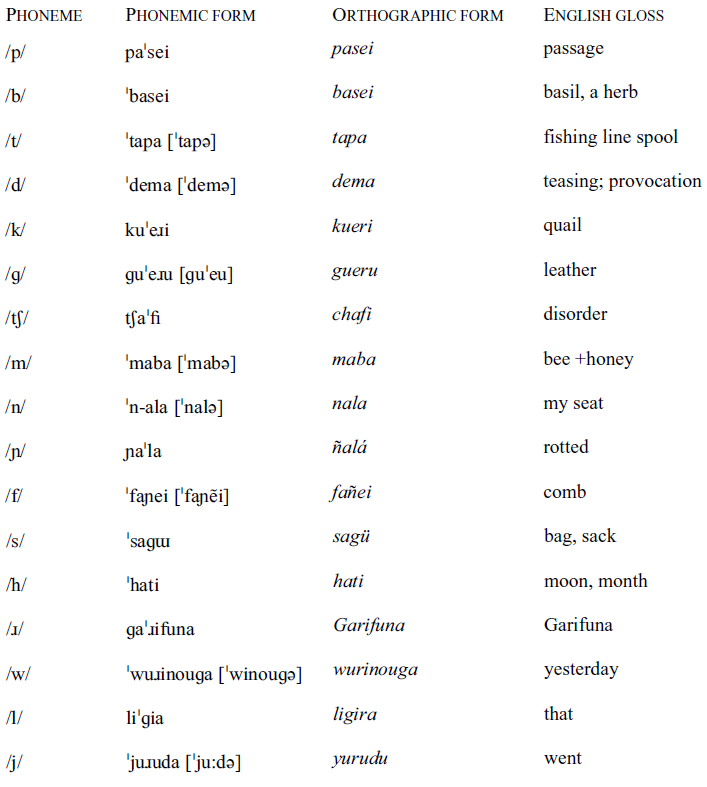

There are seventeen phonemic consonants in the Garifuna spoken in Hopkins. This includes seven sonorants (including two glides and three nasals) and ten obstruents. The obstruents include six plosives, three fricatives and one affricate. Only the plosives have a voicing distinction. In the Hopkins variety of Garifuna there is variable lenition of the post-alveolar affricate to a palatal fricative; this is discussed below. The rhotic /ɹ/ is usually an alveolar approximant in the Hopkins variety but a tap or a trill in other varieties of Garifuna (Suazo Reference Suazo1991a, Haurholm-Larsen Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016, Quesada Reference Quesada2017). In his description of the Hopkins variety in the 1950s Taylor (Reference Taylor1955: 235) notes that ‘/r/ varies from an apical flap to a mild trill’, but in Hopkins today the tapped or trilled variant is rare. As younger speakers rarely produce it, this seems to be a change in progress that has gone to completion, as described in more detail in Ravindranath (Reference Ravindranath2009). While it seems likely that the difference between the approximant in the Garifuna of Belize and the tap in the Garifuna of Guatemala and Honduras is due to language contact with the dominant language (English or Kriol in Belize; Spanish in the rest of Central America), more detailed study is needed. In the Hopkins variety there is also variable deletion of /ɹ/, discussed further below. All of the words in the word list below were said alone and in a carrier phrase in this format ‘TOKEN, neˈɹẽgujẽ TOKEN hun, TOKEN’.

Note: In this table and throughout this illustration we use the vowel /a/ to denote a low central vowel for typographical convenience, although strictly speaking the vowel in Garifuna is closer to /ɐ/.

The phonemic transcription the words in the word list here includes additional, phonetic detail for those phenomena that are discussed in more detail in this illustration. The orthographic form is based on Cayetano (Reference Cayetano1993).

Voicing and aspiration

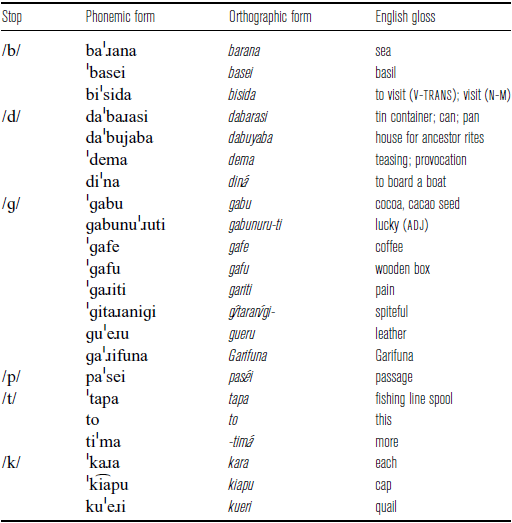

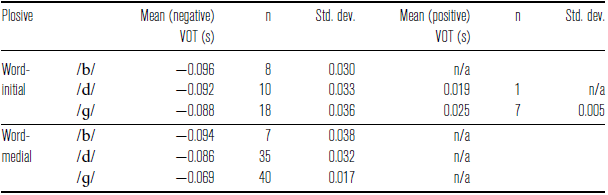

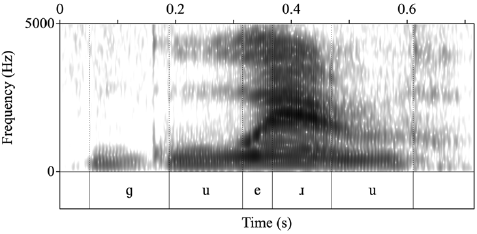

The phonemic contrast for the set of plosives in Garifuna is between a voiceless aspirated /p t k/ and voiced /b d ɡ/. Although a voicing contrast is unusual for Arawak languages (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald, Dixon and Aikhenvald1999), we find a voicing contrast in all three places of articulation for plosives. There is no voicing contrast for the three fricatives /f s h/ or the affricate /tʃ/. Taylor (Reference Taylor1955) describes the voiceless plosives as unaspirated, allowing that they are occasionally aspirated in the onset of stressed syllables, but in our data we find aspiration of voiceless stops that is consistent throughout the data (see Table 3 and Figures 2 and 4 below). We cannot rule out the possibility that the development of the contrast between voiceless aspirated and unaspirated voiced stops was promoted by contact with English, where the contrast exists. Similar changes have been reported, for example for Maori, where the unaspirated plosives typical of Polynesian languages have developed into aspirated voiceless plosives (Maclagan & King Reference Maclagan and King2007). A contact explanation for the development of aspiration in Garifuna does beg the question of why the word-initial voiced stops in Garifuna are pre-voiced, contra the usual English realization as voiceless and unaspirated, and highlights the need for further empirical studies of language contact and language variation in dialects of Garifuna.

Table 1 List of words used to measure stop VOTs.

The voice onset times were measured for both word-initial and word-medial plosives in three iterations of the words in Table 1, following Lisker & Abramson (Reference Lisker and Abrahmson1964), and Keating (Reference Keating1980), from the abrupt onset of energy of the stop’s release. Word-medially, VOT was only measured in those plosives where there was a visible burst (as discussed below, word-medial voiced plosives are frequently lenited to approximants).

VOT measurements before the release were noted as negative, and those after the release were noted as positive. The average VOT for each type of plosive are given in Tables 2 and 3. Voiced plosives /b d ɡ/ have mostly negative VOTs, except for a few instances. Positive and negative VOTs for voiced plosives are reported separately in Table 2.

Table 2 Mean VOT for voiced plosives in both word-initial and word-medial position.

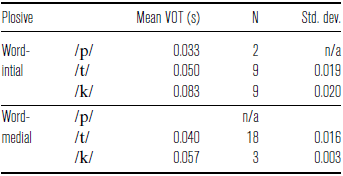

Table 3 Mean VOT for voiceless plosives in both word-initial and word-medial position.

Voiceless plosives are infrequent in the language; many of the instances of word-initial velar and bilabial plosives are in loanwords. There were no instances of word-medial /p/. In the word list elicitation, all of the word-initial voiceless plosives are aspirated, with all instances having positive VOTs. The number of tokens for each type is also given in Table 3.

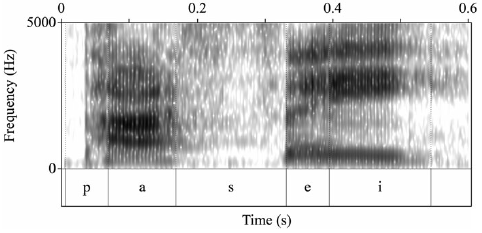

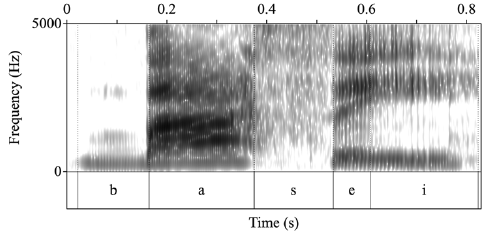

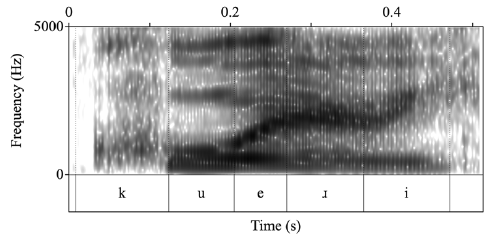

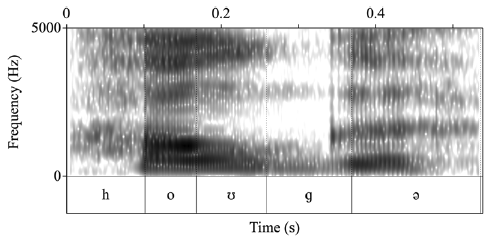

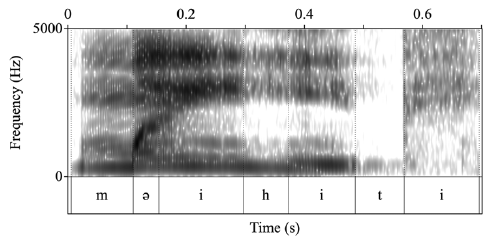

The distinction between voiced and voiceless plosives is seen most clearly in the spectrograms for the minimal pairs pasei and basei (Figures 2 and 3) and kueri and gueru (Figures 4 and 5), where the voiceless stops /p/ and /k/ include a characteristic release burst followed by frication before transitioning to the vowel.Footnote 1

Figure 2 Pasei ‘passage’ with voiceless aspirated /p/.

Figure 3 Basei ‘basil’ with voiced /b/.

Figure 4 Kueri ‘quail’ with voiceless aspirated /k/.

Figure 5 Gueru ‘leather’ with voiced /ɡ/.

Lenition

Plosives

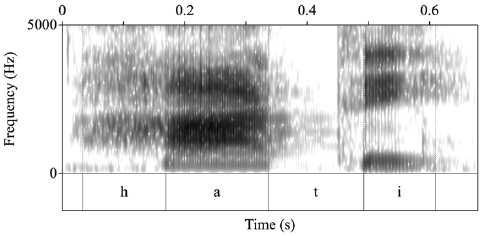

Although Taylor writes that intervocalic voiceless stops ‘vary freely’ with voiced stops, this does not occur in this data. In the speech of our consultant even many of the intervocalic voiceless plosives are aspirated, as shown in Figure 6 in the word hati ‘moon/month’, where the /t/ includes aspiration following the release burst before transitioning to the regular pulses of the vowel formants in /i/.

Figure 6 Hati ‘moon/month’ with voiceless aspirated intervocalic /t/.

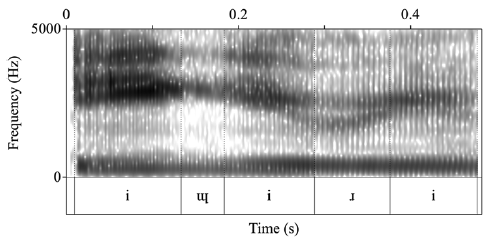

In contrast, her inter-vocalic voiced plosives sometimes lenite to voiced approximants; this seems to occur more often with alveolar or velar plosives than with the bilabial. Figure 7 demonstrates this lenition in the word igiri ‘nose’, where the velar plosive is lenited to an approximant.

Figure 7 Igiri ‘nose’ with lenition of intervocalic voiced /ɡ/.

Affricates

The post-alveolar affricate /tʃ/ demonstrates lenition to a voiceless palatal fricative [ʃ]. This was described as allophonic and/or stable sociolinguistic variation by Taylor (Reference Taylor1955: 235), who writes:

/c/ varies from a hushing sibilant, [š], in unstressed syllables, to a palatal affricate [č], in stressed syllables; most speakers employ the latter variant in deliberate speech for all positions.

The initial part of this description implies that the variation is allophonic if the affricate only occurs in the onset of stressed syllables and the fricative elsewhere, however the latter part of the description sounds as if the variation could today be described as sociolinguistic, that is that in any context the outcome is variable depending on speaker and ‘deliberateness’ of speech.Footnote 2

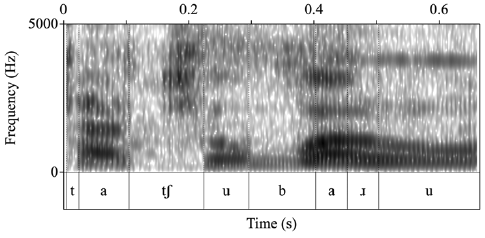

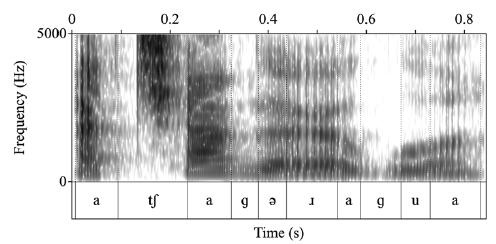

Recordings of natural speech from sociolinguistic interviews in Hopkins provide evidence against a strictly allophonic analysis, as both variants are possible in the onset of stressed syllables. As there are no obstruent codas in Garifuna, all of the tokens of either variant are in syllable onsets. The examples in Figures 8 and 9 come from the speech of a Hopkins man, born in the 1940s, in the context of telling the Mercer Meyer story ‘A Boy, a Dog and a Frog’. In Figure 8 he uses the affricate in the onset of the stressed syllable <chu> in the word tachubaru ‘jump’, with clear evidence of a plosive (release burst) before the onset of frication; in Figure 9 he uses the fricative [ʃ] in the same word, with no evidence of a release burst.

Figure 8 Tachubaru ‘jump’ with the affricate [tʃ].

Figure 9 Tachubaru ‘jump’ with the fricative [ʃ].

The consultant for this illustration produces the affricate variant categorically in the word list as well as in the longer text, as do most speakers born after 1970 (for more on this see Abtahian Reference Abtahian2020); this may be an effect of contact with English, where the two sounds are phonemic.

Rhotic

The rhotic in Garifuna is usually an alveolar approximant in Hopkins although the tap or trill are also attested in the community as well as in other parts of the Garifuna diaspora. In Honduras, where Garifuna is in contact with Spanish (where alveolar rhotics include a tap and a trill), the tap is the only reported variant (Suazo Reference Suazo1991a, Haurholm-Larsen Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016). In Belize, where Garifuna is primarily in contact with varieties of English and Kriol that use the approximant, the approximant is the more common variant (Ravindranath Reference Ravindranath2008, Reference Ravindranath2009). This demonstrates a real-time change in Hopkins from Taylor’s (Reference Taylor1955) description of the rhotic as varying between an apical flap and a trill. In fact, the change from tap to approximant seems to be an ongoing change: of the 61 speakers interviewed for Ravindranath (Reference Ravindranath2009) only six produced any tokens of /ɾ/, and all of these speakers were born before 1955. Speakers born after that time were categorical users of the approximant. The two variants may be heard in the examples laru duna ‘to the water’ [laɹu dunə] and ladagaragudüni ‘put it down’ [ladagaɾagudɯni], both from the same recording of a Hopkins man, born in the 1940s, telling the Mercer Meyer story ‘A Boy, a Dog and a Frog’.

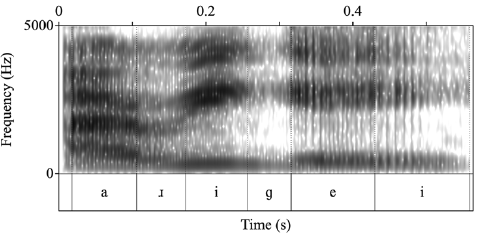

The alveolar approximant is also variably lenited or elided completely by some speakers. For this illustration our consultant read a list of words with /ɹ/ in various phonological environments and produced both the /ɹ/-ful and /ɹ/-less pronunciations when they were available for her. In some cases the /ɹ/ could not be elided, which may be a lexical phenomenon. Figures 10 and 11 demonstrate the word arigei ‘ear’ with both forms.

Figure 10 Arigei ‘ear’ with [ɹ].

Figure 11 Arigei ‘ear’ with /ɹ/ elided and vowel coalescence of /a+i/ → [e].

When the rhotic is elided the /ai/ that is left may be variably realized as [ai] or as [eɪ] (sometimes with an accompanying stress shift to the initial vowel, as happens here). This is described further below in the section on vowels. In the examples in Figures 10 and 11, /ɹ/ is pronounced in Figure 10 but elided in Figure 11; in the latter case the initial vowel is also raised, such that [ai] > [eɪ].

Vowels

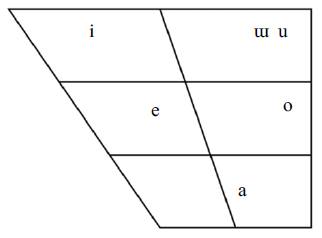

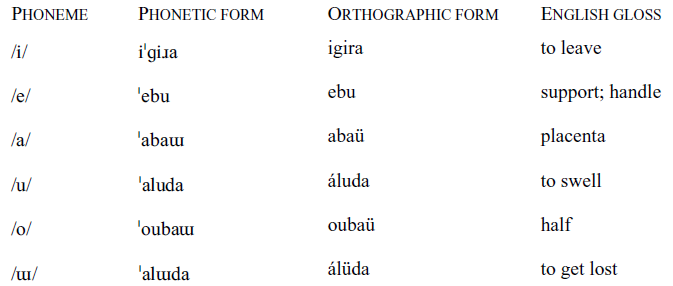

The Hopkins variety of Garifuna has six phonemic monophthongs: /i e a u o ɯ/ (orthographic i, e, a, u, o and ü). There is generally broad agreement in previous descriptions on these vowels, with a few exceptions. First, the orthographic e is variably described as /e/ (Taylor Reference Taylor1955) or /ɛ/ (Haurholm-Larsen Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016); Taylor writes that [e] and [ɛ] are allophones; we have transcribed these as /e/. Second, the high back unrounded vowel /ɯ/ is described as a fronter /ɨ/ by Haurholm-Larsen and left out of Taylor’s description completely. We have used /ɯ/ here as the mean F2 values for that vowel suggest that it is more back, with a mean F2 similar to /u/ and /o/.

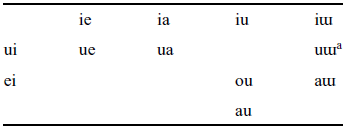

Cayetano (Reference Cayetano1993) additionally lists twelve ‘compound vowels’. We have listed these in Table 4, but leave their further phonetic description for future work (Haurholm-Larsen Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016 describes them as vowel + glide while noting that Munro Reference Munro2013 treats them as diphthongs). For the purposes of this illustration we have segmented and annotated each vowel separately in the spectrograms included here, even when they are tautosyllabic.

Table 4 Garifuna compound vowels in Cayetano (Reference Cayetano1993).

a Cayetano notates this as wɯ; we have used uɯ for consistency.

Although Taylor (Reference Taylor1955) describes nasalization of vowels as phonemic with both monophthongs and diphthongs having nasalized counterparts, we do not find evidence that nasality is distinctive. Phonetically, both progressive and regressive nasalization of vowels can occur when following or preceding a nasal consonant. Haurholm-Larsen (Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016: 20) posits that all nasal vowels that do not precede nasal consonants word-finally are derived diachronically from a following, deleted, nasal segment. Examples of the nasalized /e/ and /ie/ occur in the illustrative passage and in the carrier phrase for the word list.

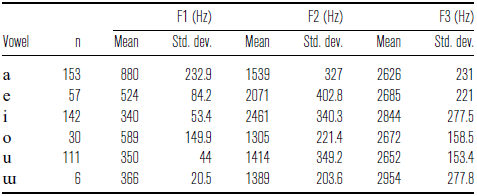

Table 5 Mean F1, F2, and F3 values in Hz for the six Garifuna monophthongs.

Figure 12 F1 and F2 values in Hz for the six Garifuna monophthongs from the word list.

The vowel formants for the six monophthongs were measured manually using Praat: the vowel intervals were identified and the formant values were measured at the midpoint of these intervals. Table 5 presents the mean F1, F2, and F3 values for the six monophthongs in Garifuna. These values were calculated using 499 stressed vowel tokens: 153 for /a/, 57 for /e/, 142 for /i/, 30 for /o/, 111 for /u/, and six for /ɯ/, all from the same speaker. The F1 and F2 values are plotted in Figure 12 using R’s ggplot2 and dplyr packages (with /ɯ/ represented in the plot by its orthographic form ü).

The F1 and F2 measurements indicate a great deal of overlap between the monophthongs /u/ and /ɯ/, and there is disagreement in the existing Garifuna literature both as to the existence of /ɯ/ and its phonetic quality. Cayetano (Reference Cayetano1993) and Haurholm-Larsen (Reference Haurholm-Larsen2016) list six monophthongs (although for Haurholm-Larsen the sixth vowel is an unrounded [ɨ]), but Taylor (Reference Taylor1955: 237) lists only five vowels, and treats [ɯ] as an allophone of /u/. The words áluda ‘to swell’ and álüda ‘to get lost’ serve as a minimal pair distinguishing the two vowels in our data, and in this minimal pair the tokens do not overlap; the three /ɯ/ tokens are fronted with respect to the three /u/ tokens. It seems likely here that the two vowels are distinguished by rounding. The mean F3 measurement for [ɯ], although based on only six tokens, is somewhat higher in our data than the mean F3 for [u].

Resolution of vowel hiatus

When /ɹ/ is deleted, as described above, leaving two adjacent vowels, there are at least three possible outcomes, including vowel deletion, vowel coalescence, and/or vowel lengthening. We briefly illustrate some cases of vowel hiatus resolution here but leave a further discussion of this phenomenon for future work.

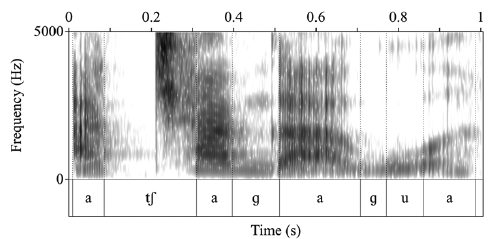

Deletion of one of the vowels may occur both when the r-deletion occurs between two different vowels or two of the same vowel. Figures 13 and 14 demonstrate this deletion in the word achaguragua ‘to chew tobacco’, where the following [a] is also lengthened.

Figure 13 Achaguragua ‘to chew tobacco’ with canonical realization of /ɹ/.

Figure 14 Achaguragua ‘to chew tobacco’ with deletion of /ɹ/ and vowel lengthening.

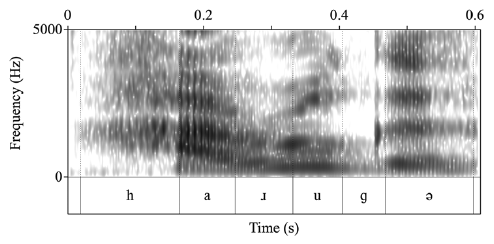

Figure 15 Haruga ‘tomorrow’ with canonical realization of /ɹ/.

Figure 16 Haruga ‘tomorrow’ with deletion of /ɹ/ and vowel coalescence of /a+u/ → [oʊ].

Figure 17 Marihiti ‘blind’ with canonical realization of /ɹ/.

The pattern of vowel coalescence, where phonemic [a] is raised before high vowels [i] and [u] is demonstrated in Figure 11 above for the word arigei ‘ear’, and in Figure 16 for the word haruga ‘tomorrow’, where vowel coalescence occurs following intervocalic r-deletion. Figure 15 shows a production of haruga with the /ɹ/ retained. Hagiwara (ms) explores a number of phonological processes concerning this phenomenon that are worth further investigation. In addition to the two types of coalescence described by Hagiwara (he names these AI-coalescence, and AU-coalescence), and exhibited in Figures 11 and 16, we also found several instances of /a/ and /i/ coalescence that resulted in diphthongs instead of the monophthongal [e]. This is demonstrated in the contrast between Figure 17 (with /ɹ/) and Figure 18 (without /ɹ/) for marihiti ‘blind’ where /a/–/i/ coalescence results in a more centralized [ə] before an offglide [i].

Figure 18 Marihiti ‘blind’ with deletion of /ɹ/ and vowel coalescence to a diphthong [əi].

Prosodic features

Garifuna is maximally a CV language, except in borrowings, where CCV is permitted (but is often broken up with a vowel in slow speech). Taylor (Reference Taylor1955: 235) notes at least one case where VC is permitted, that is in the exclamation og! – an exclamation of astonishment – but such cases are rare. All consonants may occur in onset position, although some are quite rare word-initially (including the voiceless stops /p/ and /k/, as well as /ɹ/). Additionally, vowel-initial words typically have glottalization preceding the vowel, as can be seen in the spectrograms in Figures 10 and 11 above, for arigei ‘ear’.

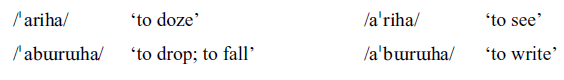

Although the placement of stress in Garifuna is usually predictable, it can be contrastive, as demonstrated by the following minimal pairs, from Cayetano (Reference Cayetano1992):

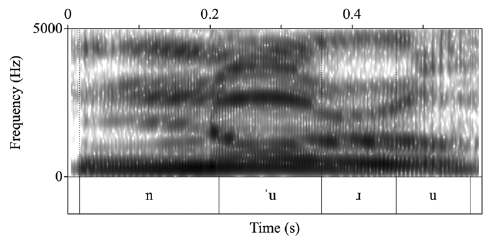

In our data pasei ‘passage’ and basei ‘basil’ serve as a near-minimal pair for the acoustic characteristics of stress (Figures 2 and 3 above), as do nuru ‘northeast wind; sea breeze’ and murú- ‘tight’ (Figures 19 and 20). In both pairs the stressed vowel has a longer duration than the corresponding unstressed vowel in the other member of the pair, and the stressed syllable exhibits a higher intensity and f0 peak.

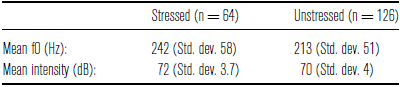

In order to determine the acoustic correlates of stress, f0 and intensity were measured for stressed and unstressed vowels in the illustrative passage. These measurements, shown in Table 6, come from 64 primary stressed syllables and 126 non-primary stressed syllables in 64 words. The words in the passage range from one to five syllables long. Measurements were made at the highest f0 and highest intensity peaks during the vowel. In the majority of the words the stressed syllable had the highest f0 and highest intensity in that word. Moreover, stressed syllables were on average consistently and significantly higher for both f0 and intensity than they were in unstressed syllables.

There are additional phonetic correlates of stress. Unstressed vowels in Garifuna are usually weak. Unstressed full vowels may be reduced to [ə], as in the word-final vowels in the word haruga ‘tomorrow’ in Figures 16 and 17, especially in final position. In addition, unstressed vowels may be devoiced in final position (Taylor Reference Taylor1955: 236). Figures 18 and 19 illustrate this variable devoicing: in Figure 18 the final /i/ in the word marihiti ‘blind’ is voiced, with a characteristic voice bar throughout in the spectrogram, while in Figure 19 the same final vowel /i/ is devoiced, as seen by the lack of a voice bar.

Figure 19 Nuru ‘northeast wind; sea breeze’ with primary stress on the first syllable.

Figure 20 Murú- ‘tight’ with primary stress on the second syllable.

Table 6 F0 and intensity in stressed and unstressed syllables in continuous speech.

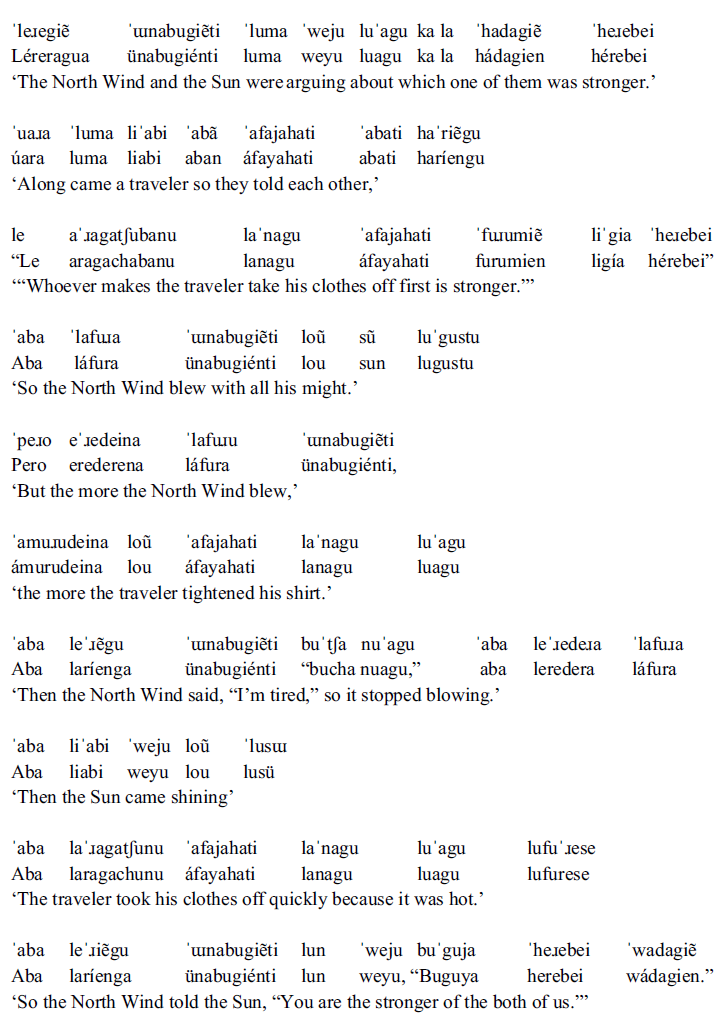

Transcription of recorded passage

The recorded passage is a retelling of ‘The North Wind and the Sun’. The transcription is primarily a phonemic transcription at the word level (morpheme boundaries are not included). Note that phonemic /ɹ/s are included in the transcription even when they are deleted in pronunciation and that final full vowels are transcribed even when they are reduced to [ə]. Phonetic nasal vowels are transcribed as such (in the orthography they are written as a vowel and following nasal consonant). An orthographic version and an English translation are included below the phonemic transcription.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the support and collaboration of the people of Hopkins, in particular Krishna Molefi, Zita Castillo-Muhsin, Sarita Martinez, Rudolph Coleman, the late Francis Lewis, and the Nunez family (Coma, Joycelyn, Prudence, Barbara, and Avis). We gratefully acknowledge the support of NSF BCS-0719035 for funding the fieldwork upon which some of this research is based. We would also like to thank Joyce McDonough, Peter Guekguezian and the members of the Phon-Phon reading group for feedback at early stages of preparing this illustration, and Peter Guekguezian for insightful notes and help during the recording process. Two anonymous reviewers, Associate Editor Marc Garellek, and Editor Marija Tabain offered helpful suggestions and commentary on the illustration. All mistakes remain our own.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100323000038.