Introduction

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (Hong Kong) is a metropolis located in the northern sector of the South China Sea at the eastern edge of the Pearl River estuary. Due to the estuary outflow, the water regime in Hong Kong is characterized by a gradient in water parameters such as organic nutrients and salinity from west to east, with the western water dominated by the fresh and nutrient-rich Pearl River effluent, and the eastern water mostly influenced by oceanic currents. Moreover, hydrological processes such as monsoon-driven currents, topography and tidal movement induces temporal dynamics to this gradient (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Gan, Liu, Liu, Xie and Zhu2021). This natural hydrological setting, along with the 1178 km of coastline and nearly 260 islands within the territory (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Chan, Dong, Hawkins, Bohn and Firth2019), has harboured numerous marine habitats such as coral communities, rocky reefs and brackish water. The subtropical climate with a sea temperature ranging from 13°C during the dry season to 30°C during the wet season has also allowed both tropical and temperate marine species to inhabit the area (Morton & Wu, Reference Morton and Wu1975). These factors have led to high marine biodiversity being found in the territory, where 26% of the total marine species records in China can be found, despite Hong Kong making up only about 0.03% of the marine territory of China (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Cheng, Ho, Lui, Leung and Williams2017).

Despite the absence of true coral reef structure, existing coral communities and substrates in Hong Kong are capable of sustaining a wealth of reef fish species, where fish species richness and abundance have been shown to correlate with substrate structural complexity (Cornish, Reference Cornish1999; Shea, Reference Shea2009). An initial underwater visual census and market survey study in 2000 documented 325 reef fish species (Sadovy & Cornish, Reference Sadovy and Cornish2000). In 2014, a subsequent study of similar scale was established to document reef fish species in Hong Kong. The study, employing underwater visual surveys, led to the discovery of 19 new species records to Hong Kong between June 2014 and July 2018 (To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016; Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018), bringing the total recorded reef fish species to over 340 species. Yet, it was estimated that the marine environment in Hong Kong could harbour over 500 reef fish species, implying that the reef fish diversity of the city remains largely underexplored despite being a biodiversity hotspot located just on the fringe of the Coral Triangle (Sadovy & Cornish, Reference Sadovy and Cornish2000; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Cheng, Ho, Lui, Leung and Williams2017).

For decades, the under-studied potential wealth of marine fish biodiversity in Hong Kong has remained insufficiently protected. Habitat degradation, water pollution, as well as high fishing pressure in the area have been and continue to be the major threats to the reef fish biodiversity in Hong Kong (Morton, Reference Morton1989; Liu & Hills, Reference Liu and Hills1998; To & Sadovy De Mitcheson, Reference To and Sadovy De Mitcheson2009). To date, millions of metric tonnes of sewage are discharged into the marine environment regularly (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Perkins, Ho, Astudillo, Yung, Russell, Williams and Leung2016). Eutrophication, often a result of nutrient pollution, has been shown to pose negative effects on coral biodiversity in Hong Kong (Duprey et al., Reference Duprey, Yasuhara and Baker2016), which is closely tied with the life cycle of reef fishes (Sadovy & Cornish, Reference Sadovy and Cornish2000). On fishing pressure, traditional fisheries have long been over-exploited since the 1970s, followed by a shift in ecosystem structure where large predatory fishes were replaced by smaller fishes and benthic invertebrates (Cheung & Sadovy, Reference Cheung and Sadovy2004). Despite the multiplicity of human disturbances, few regulations are in place to control the harvesting of what remains of the marine fish species in Hong Kong. Non-trawling fishing vessels are still permitted to continue fishing, while unregulated recreational fishing including hand-lining and spearfishing is on the rise. As yet, there have been few studies conducted to understand the impact of these activities on local marine fish biodiversity, and there is no guarantee that such fishing activities would not undermine existing species populations (Whitfort et al., Reference Whitfort, Cornish, Griffiths and Woodhouse2013).

To relieve pressures on local reef fish populations and to conserve what remains of the marine biodiversity, the designation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) has been a focus of the extension of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) to Hong Kong in 2011, as well as that of Hong Kong's first city-level Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (BSAP) in 2013, which aimed at stepping up biodiversity conservation and contributing to global efforts on biodiversity conservation (Environmental Bureau, 2016). Currently, there is a total of eight designated Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) (seven marine parks and one marine reserve) distributed around Hong Kong waters (Figure 1), occupying around 6117 hectares and ~3.7% of the total territorial waters (Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, 2022). This percentage is far below the goal of having 10% of the coastal and marine areas protected by 2020, as previously agreed by parties of CBD (Claudet et al., Reference Claudet, Loiseau, Sostres and Zupan2020).

Fig. 1. Maps showing (a) location of Hong Kong within the South China Sea, (b) designated marine parks and marine reserve in Hong Kong, that are highlighted in yellow; and sites with new species record to Hong Kong found in this study: 1. Port Island; 2. Kung Chau; 3. Tsim Chau; 4. East Dam; 5. Pak Lap Tsai; 6. Wang Chau; 7. Basalt Island; 8–9. The Ninepin Group; 10. Bluff Island; 11. Trio Island; 12. Jin Island; 13. Shelter Island; 14. Tai She Wan; 15. Sharp Island.

Hong Kong's MPA agenda is therefore evidently overdue. Prompt action is required to identify priority locations to implement effective and focused control to protect the overall reef fish diversity, as well as rare or threatened species that are yet to be found in Hong Kong. Clear indication of biodiversity, especially from long-term surveys, is therefore largely necessitated to ensure the identification and protection of biodiversity hotspots, and has been called for since the 1990s (Liu & Hills, Reference Liu and Hills1998).

Since 2014, a long-term study has been documenting Hong Kong's reef fish biodiversity to support conservation measures by way of underwater visual surveys (To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016; Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018) – a widely applied technique for surveying reef fish (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Zgliczynski, Williams and Sandin2016; Pais & Cabral, Reference Pais and Cabral2018). This paper describes 31 additional records made in Hong Kong between 2018–2021 from the abovementioned study. Consistent long-term data collection of reef fish biodiversity is foundational to the establishment of a reliable baseline and to build a regularly updated database, such that species and areas most in need of conservation attention could be identified for informed research and conservation efforts in the future.

Survey method

During the periods of August to October 2018, May to November 2019, May to October 2020 and May to November 2021, underwater visual surveys using scuba were conducted across 55 dive sites in Hong Kong waters, with a total of ~3171 hours of underwater survey time undertaken. The survey was mainly conducted in daytime, with a few dives conducted at dawn, during sunset and at night with depth ranging from 1.2–24 m. The surveys were conducted in the wet season from late spring to late autumn as species richness, abundance and biomass of reef fishes in Hong Kong were found to be considerably lower in the dry season (Cornish, Reference Cornish1999).

Whenever a new species to Hong Kong was encountered, the habitat and behaviour(s) of the fish were recorded, and photographs were taken as a record and used in post-dive species identification verification. All the species were further verified by ichthyologists with extensive experience in reef fish research. Reference to WoRMS (2022) was made to verify nomenclature. The approximate GPS location of the new species records were retrieved using Google Earth.

Results

Acanthurus xanthopterus Valenciennes, 1835, family: Acanthuridae

Three individuals of Acanthurus xanthopterus Valenciennes, 1835 were observed at East Dam (22°21′39″N 114°22′32″E) on 22 June 2020 during daytime (Figure 2a–c). The individuals swam along the dolosse wall at around 5 m depth, occasionally dipping in and out of the larger crevices between the dolosse. They were observed again when divers returned to the same site on 25 June and 7 July 2020. This species is found in the Indo-Pacific, in at least 68 countries/territories including records from Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Taiping Island, Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam, and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Fig. 2. Newly recorded species in Hong Kong: (a–c) Acanthurus xanthopterus; (d, e) Chaetodon adiergastos; (f) Chaetodon selene; (g) Heniochus singularius; (h) Diodon hystrix. Photographs: 114°E Hong Kong Reef Fish Survey.

Chaetodon adiergastos Seale, 1910, family: Chaetodontidae

A single individual of Chaetodon adiergastos Seale, 1910 was observed on 19 September 2019 at Tai She Wan (22°21′21″N 114°20′26″E) during a day dive (Figure 2d, e). The individual was ~12 cm in total length, and was found swimming around large boulders at 2–3 m depth and occasionally dipping into crevices. In 2021, the species was observed again at another dive site in a different location. The native range of this species covers mainly the Western Pacific region and found in at least 13 countries/territories, including Brunei, mainland China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, Timor-Leste, Vietnam, Australia and Palau (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Xisha Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Chaetodon selene Bleeker, 1853, family: Chaetodontidae

A single individual of Chaetodon selene Bleeker, 1853 was recorded on 10 June 2021 during daytime (Figure 2f) at the South Ninepin Group (22°15′33″N 114°20′57″E). The individual was ~10 cm in total length and was found singly, among soft corals at 13 m depth. Chaetodon selene is found in the Western Pacific in at least seven countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022) and is recorded in Taiwan (Pingtong County) and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022).

Heniochus singularius Smith & Radcliffe, 1911, family: Chaetodontidae

An individual of Heniochus singularius Smith & Radcliffe, 1911 was observed on 9 September 2021 during daytime (Figure 2g) at Pak Lap Tsai (22°21′112″N 114°22′05″E), and was spotted again a few days later on 12 September 2021 at the same site. The individual was found close to shore at around 3–5 m depth, and took shelter behind a large boulder. Heniochus singularius is documented to occur in the Pacific Ocean in at least 29 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Taiping Island, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Diodon hystrix Linnaeus, 1758, family: Diodontidae

On 29 June 2019, an individual of Diodon hystrix Linnaeus, 1758 was observed at Pak Lap Tsai (22°21′112″N 114°22′05″E), during daytime (Figure 2h). The individual was estimated to be ~45 cm in total length. It was found at around 4 m depth and took shelter in a large crevice between boulders. During survey dives in 2019 and 2021, individuals of various sizes were observed again at three other different dive sites, and each time the individuals were observed singly. This species is found in the Eastern Pacific, Western Atlantic and Western Indian Ocean, in at least 105 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022), and is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Amblyeleotris wheeleri (Polunin & Lubbock, 1977), family: Gobiidae

An individual of Amblyeleotris wheeleri (Polunin & Lubbock, 1977) was observed on 10 June 2021 during daytime, at the South Ninepin Group (22°15′33″N 114°20′57″E), at around 9 m depth (Figure 3a). The substrate was mainly sandy with small rocks. The individual was found perched outside its burrow. The species is distributed in the Indo-Pacific in at least 24 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Spratly Islands, Tungsha (Pratas), Ryukyu Islands, and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Fig. 3. Newly recorded species in Hong Kong: (a) Amblyeleotris wheeleri; (b) Amblygobius nocturnus; (c) Cryptocentrus nigrocellatus; (d) Eviota teresae; (e, f) Gnatholepis cauerensis; (g, h) Gobiodon axillaris. Photographs: 114°E Hong Kong Reef Fish Survey.

Amblygobius nocturnus (Herre, 1945), family: Gobiidae

A single individual of Amblygobius nocturnus (Herre, 1945) was observed at Sharp Island (22°21′39″N 114°17′28″E) during daytime on 21 October 2019 (Figure 3b). The individual was ~6 cm in total length, and was found hovering just above the sandy bottom at around 3–4 m depth with small rocks and dispersed Pavona sp. coral communities. Several more individuals of various sizes were observed at the same site on 9 November 2019, and 10 and 15 October 2020, with more than one individual observed in the same dive. This species is found in the Western Indian Ocean and throughout the Pacific in at least 30 countries/territories including Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Taiwan and mainland China (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Cryptocentrus nigrocellatus (Yanagisawa, 1978), family: Gobiidae

An individual of Cryptocentrus nigrocellatus (Yanagisawa, 1978) was observed on 13 June 2021 during daytime (Figure 3c), near southern Shelter Island (22°19′19.17″N 114°17′54.72″E). It was observed at ~6 m depth, at the mouth of its burrow in the sandy substrate. Individuals of the species were observed again singly on 8 July 2021 and 4 September 2021 at different dive sites. The species is documented to occur in the North-west Pacific in at least seven countries/territories. It is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas) and Ryukyu Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Eviota teresae Greenfield & Randall, 2016, family: Gobiidae

Both Eviota guttata Lachner & Karnella, 1978 and Eviota teresae Greenfield & Randall, Reference Greenfield and Randall2016 were considered possible identifications for this goby. While Eviota guttata is recorded in Taiwan (Shao, Reference Shao2022), sources also suggest that the species is mainly distributed in the Indian Ocean and mostly likely replaced by Eviota teresae when observed in the Pacific Ocean (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022, accessed online 8 May 2022). Eviota teresae is also recorded in Fiji and Japan (Greenfield & Randall, Reference Greenfield and Randall2016; Fujiwara et al., Reference Fujiwara, Jeong, Matsuoka and Motomura2022).

Two individuals of Eviota teresae were observed at Basalt Island (22°18′31″N 114°21′52″E) on 16 September 2020 during daytime in a survey dive (Figure 3d). The individuals were observed separately by the same divers. Both individuals were estimated to be ~3 cm in total length and found perched on the rocky substrate at ~5 m depth, surrounded by larger boulders and some distance away from each other. Both fish stayed for a few minutes as divers approached, before darting away into crevices between rocks. The species was recorded again in various dive sites after the first sighting, including in surveys in 2020 and 2021.

Gnatholepis cauerensis (Bleeker, 1853), family: Gobiidae

A single Gnatholepis cauerensis (Bleeker, 1853) was observed at Basalt Island (22°18′31″N 114°21′52″E), on 16 September 2020 during daytime (Figure 3e, f). The goby was found perched on sandy bottom at about 10–15 m depth, and fled from the diver after photographs were taken. Identification was made based on the dark bar above and under each eye, body pattern with a row of dark blotches along the side of the body, and distribution information. The individual is further differentiated from similar-looking species by the dorsal fin, in which the fifth D1 spine is shorter than the third to fourth spines, which gives the fin a rounded appearance when extended (personal communication, Lin 2022). Gnatholepis caurensis is reported from 42 countries/territories, including Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Gobiodon axillaris De Vis, 1884, family: Gobiidae

A single individual of Gobiodon axillaris De Vis, 1884 was observed on 14 August 2021 during daytime (Figure 3g, h) at East Dam (22°21′38.76″N 114°22′31.43″E). The individual was ~2–3 cm in total length and was found in Acropora sp. branches at ~3 m depth with individuals of Gobiodon prolixus Winterbottom & Harold, Reference Winterbottom and Harold2005. On 23 August 2021 a few individuals were spotted at the same site among other Acropora colonies. On 4 September 2021 individuals were spotted again at a different dive site (Pak Lap Tsai) at around 3–4 m depth. All observations were made during daytime, and in every encounter the fish were found in Acropora sp. Gobiodon axillaris is documented to occur in at least three countries/territories in the Indo-Pacific, including Australia, New Caledonia and Vanuatu (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Japan (Ryukyu Islands) (Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018). It has never been reported in Taiwan or mainland China, making this record the first in the region.

Gobiodon prolixus Winterbottom & Harold, 2005, family: Gobiidae

An individual of Gobiodon prolixus Winterbottom & Harold, Reference Winterbottom and Harold2005 was observed on 14 August 2021 during daytime at East Dam, among branches of Acropora sp. at ~3 m depth (Figure 4a–c) and alongside a few Gobiodon axillaris De Vis, 1883 individuals. The fish was ~3–4 cm in total length and appeared wary of divers, hiding deeper among the branches of the Acropora sp. Individuals were spotted during daytime again on 23 August 2021, at the same dive site but in different Acropora sp. colonies; and again during a day dive on 4 September 2021 at another dive site, where they took shelter under the same Acropora sp. colony with individuals of Gobiodon axillaris. Gobiodon prolixus is found in the Indo-Pacific in at least 12 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Japan (Ryukyu Islands) and Vietnam (Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Fig. 4. Newly recorded species in Hong Kong: (a–c) Gobiodon prolixus; (d, e) Anampses geographicus; (f) Bodianus dictynna; (g) Cirrhilabrus cyanopleura. Photographs: 114°E Hong Kong Reef Fish Survey.

Anampses geographicus Valenciennes, 1840, family: Labridae

Three individuals of Anampses geographicus Valenciennes, 1840 were found on 22 July 2021 during daytime (Figure 4d, e) at the South Ninepin Group (22°15′33″N 114°20′57″E). The individuals were found swimming around with a group of Halichoeres marginatus Rüppell, 1835 at ~3 m depth. The individuals ranged from around 10–20 cm in total length, which is small relative to the potential maximum size of 31 cm in total length (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). A single individual of the species was observed again at another dive site (Pak Lap Tsai) on 12 September 2021. Anampses geographicus is distributed in the Indo-West Pacific, in at least 17 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Kaohsiung, Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018).

Bodianus dictynna Gomon, 2006, family: Labridae

An individual of Bodianus dictynna Gomon, 2006 was observed at Basalt Island (22°18′31″N 114°21′52″E), on 7 June 2020, in daytime (Figure 4f). The individual was ~10 cm in length, and was found dipping in and out of crevices between rocks at ~5 m depth. Bodianus dictynna is distributed in the Western Pacific and found in at least 17 countries/territories including Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam (Shao, Reference Shao2022; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Spratly Islands, Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Ryukyu Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018).

Cirrhilabrus cyanopleura (Bleeker, 1851), family: Labridae

An individual of Cirrhilabrus cyanopleura (Bleeker, 1851) was found at the Ninepin Group (22°16′00″N 114°21′58″E) on 31 May 2020 (Figure 4g). The individual was estimated to be ~8 cm in length. Boulders were the primary substrate where the individual was found, at 8 m depth, swimming rapidly 1–3 m above the substrate, and although it swam among other groups of fishes, it never schooled with them. The wrasse was observed again in the similar area when divers returned to the site on 11 August 2020. This species is found in the Indo-West Pacific, with records from at least 12 countries/territories, including Australia, Christmas Island, Indonesia, Japan, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Spratly Islands, Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Ryukyu Islands and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Halichoeres marginatus Rüppell, 1835, family: Labridae

An individual of Halichoeres marginatus Rüppell, 1835 was observed on 17 October 2018 during daytime at Jin Island (22°19′31.99″N 114°19′39.36″E), at ~3 m depth (Figure 5a, b). The fish was ~5 cm in total length (in juvenile phase), and was found swimming around a boulder. It was thereafter observed once on 18 May 2019 and multiple times in later years in various dive sites during survey dives in 2020 and 2021, in both adult and juvenile phases. On some occasions sub-adults of the species were found schooling with other sub-adult labrids. Halichoeres marginatus is found in the Indo-Pacific in at least 50 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022), and is recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Spratly Islands, Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Fig. 5. Newly recorded species in Hong Kong: (a, b) Halichoeres marginatus; (c) Halichoeres melanochir; (d) Thalassoma lutescens; (e, f) Upeneus sp.; (g) Scolopsis ciliata. Photographs: 114°E Hong Kong Reef Fish Survey.

Halichoeres melanochir Fowler & Bean, 1928, family: Labridae

A single individual of Halichoeres melanochir Fowler & Bean, 1928 was observed on 15 May 2019, at Basalt Island (22°18′31″N 114°21′52″E), during daytime (Figure 5c). The individual stayed close to the rocky substrate at around 5–6 m depth. Several other individuals were observed in survey dives throughout 2019 and 2020, including juveniles. This species is naturally found in the Western Pacific region, and has been reported in at least nine countries/territories, including mainland China, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, Timor-Leste, Vietnam and Australia (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008).

Thalassoma lutescens (Lay & Bennett, 1839), family: Labridae

A single individual of Thalassoma lutescens (Lay & Bennett, 1839) was observed on 27 July 2021 during daytime at East Ninepin Group (Figure 5d). The individual was ~20 cm in total length and was found swimming near large boulders at 11 m depth. On 2 September 2021 an individual was observed again at another dive site, at about 4 m depth. Thalasomma lutescens is found in the Indo-Pacific, in at least 36 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Kaohsiung, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Upeneus species, family: Mullidae

A small school of Upeneus species including 8–9 individuals of various sizes was observed at the Ninepin Group (22°15′33″N 114°20′57″E) on 8 September 2020 during daytime (Figure 5e, f). The individuals ranged from 10–15 cm in total length, and were swimming around the sandy substrate, often stopping to forage. Individuals were observed again in 2021 at the same site. Morphological features observed in the photographs taken, including a distinctive red bar below eye, body pattern, presence of red-brown stripes on the upper caudal lobe and visible stripes replaced by a single red-brown bar on the lower caudal lobe, indicate that the individuals may be either Upeneus sundaicus (Bleeker, 1855) or Upeneus guttatus (Day, 1868). Upeneus sundaicus and Upeneus guttatus are similar in appearance, and accurate identification between the two species can only be determined by obtaining a specimen for closer inspection to count for number of spines, rays, gill rakers, lateral line scales and measurements (Uiblein & Heemstra, Reference Uiblein and Heemstra2010, Reference Uiblein and Heemstra2011). Either species would be a new record for Hong Kong. Upeneus sundaicus is reported in 20 countries/territories, and Upeneus guttatus is reported in 21 countries or territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, Upeneus sundaicus is recorded in Ha Long Bay and Zhanjiang (Pavlov, Reference Pavlov2016; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Yi, Qiu, Liu, Gu and Yan2021). Upeneus guttatus is recorded in Kagoshima and the Philippines (Uiblein & Heemstra, Reference Uiblein and Heemstra2010; Motomura et al., Reference Motomura, Yamashita, Itou, Haraguchi and Iwatsuki2012).

Scolopsis ciliata (Lacepède, 1802), family: Nemipteridae

On 29 September 2019, three individuals of Scolopsis ciliata (Lacepède, 1802) were observed at Bluff Island (22°19′31.1″N 114°21′15.2″E) during daytime in a survey dive (Figure 5g). These individuals ranged from 10–15 cm in total length, and formed a school while swimming near the sandy substrate along the edge of coral communities at 4–5 m depth. The species was recorded again during surveys in 2020. Scolopsis ciliata is found in the Indo-West Pacific in at least 24 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022), including Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Parapercis millepunctata (Günther, 1860), family: Pinguipedidae

A single individual of Parapercis millepunctata (Günther, 1860) was observed at Tsim Chau (22°2′21″N 114°2′14′′E) on 7 July 2020 during daytime (Figure 6a–c). The individual was found hiding under a branching coral at water depth of 4 m. The species was observed again at the same site on 9 July 2020. Another individual was found at Cheung Tsui/Long Mouth on 6 August 2020 during daytime, perched on rocky substrates at 5–6 m depth. In both sites, individuals were ~15 cm in total length. During surveys in 2021, the species was also observed at Cheung Tsui. Parapercis millepunctata is found throughout the Indo-Pacific and Oceania in at least 29 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022), including Taiwan and mainland China (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Fig. 6. Newly recorded species in Hong Kong: (a–c) Parapercis millepunctata; (d) Parapercis tetracantha; (e) Centropyge bicolor; (f) Plectroglyphidodon leucozonus; (g) Pomacentrus nagasakiensis; (h) Pomacentrus tripunctatus. Photographs: 114°E Hong Kong Reef Fish Survey.

Parapercis tetracantha (Lacepède, 1801), family: Pinguipedidae

A single individual of Parapercis tetracantha (Lacepède, 1801) was observed on 29 June 2019 at Wang Chau (22°19′46″N 114°22′33″E) during daytime (Figure 6d). The individual was about 16 cm in total length, and was found perched on rocky substrate near a large boulder at about 4–5 m. This species is found mainly in the Indo-West Pacific, and has been recorded at least in Andaman Islands, Cocos Island, India, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Fiji, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Island and mainland China (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas) and Ryukyu Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018).

Centropyge bicolor (Bloch, 1787), family: Pomacanthidae

On 20 September 2020, an individual of Centropyge bicolor (Bloch, 1787) estimated to be ~12 cm in total length was observed at the Ninepin Group (22°15′38″N 114°21′08″E) during underwater surveys (Figure 6e). The fish was observed at ~9 m depth. Boulders were the primary substrate of the habitat, and the fish was observed to swim around a large boulder above smaller boulders. The species was also observed at the same site on 22 September 2020, and again at another location on a different day. This species is found in the Indo-Pacific, and recorded in at least 56 countries/territories including Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Plectroglyphidodon leucozonus (Bleeker, 1859), family: Pomacentridae

A single individual of Plectroglyphidodon leucozonus (Bleeker, 1859) was observed at Wang Chau (22°19′46″N 114°22′33″E) on 29 June 2019 in daytime (Figure 6f). The individual was found hiding between crevices of rocks piled on the substrate at ~6 m depth. Several other individuals were observed during dives in 2020, at a different dive site. Plectroglyphidodon leucozonus is found throughout the Indo-Pacific, and reported in at least 38 countries/territories including Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Kaohsiung, Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Pomacentrus nagasakiensis Tanaka, 1917, family: Pomacentridae

One individual of Pomacentrus nagasakiensis Tanaka, 1917 was recorded at Port Island (22°30′12.48″N 114°21′23.31″E) on 26 August 2018 during daytime (Figure 6g). The individual was estimated to be around 5 cm in total length and was found at around 7 m depth. An individual was observed again on 6 August 2020 at another dive site. Pomacentrus nagasakiensis is observed in the Indo-West Pacific in at least 16 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). It is also recorded in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Pomacentrus tripunctatus Cuvier, 1830, family: Pomacentridae

A single individual of Pomacentrus tripunctatus Cuvier, 1830 was observed on 25 October 2021 during daytime (Figure 6h) at Sharp Island (22°21′39″N 114°17′28″E). The individual was estimated to be ~4 cm in total length and was observed in shallow water of ~2–3 m depth, dipping in and out of corals and debris on the substrate. An individual was observed again at the same dive site on 2 November 2021. Pomacentrus tripunctatus is found in the Indo-West Pacific in at least 18 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022), including in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Kaohsiung, Pingtong County, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Ptereleotris heteroptera (Bleeker, 1855), family: Ptereleotridae

A single Ptereleotris heteroptera (Bleeker, 1855) was observed on 7 June 2019 during daytime (Figure 7a) at Kung Chau (22°28′59″N 114°22′20″E). The individual was ~5 cm in length, and was found at ~11 m depth among a group of Ptereleotris hanae (Jordan & Snyder, 1901). It eventually swam away from the group on its own. The diver noticed the individual of Ptereleotris heteroptera by the distinctive black blotch on the caudal fin, and took photographs. Ptereleotris heteroptera is found in the Indo-Pacific, and recorded in at least 41 countries/territories including Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Philippines, Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

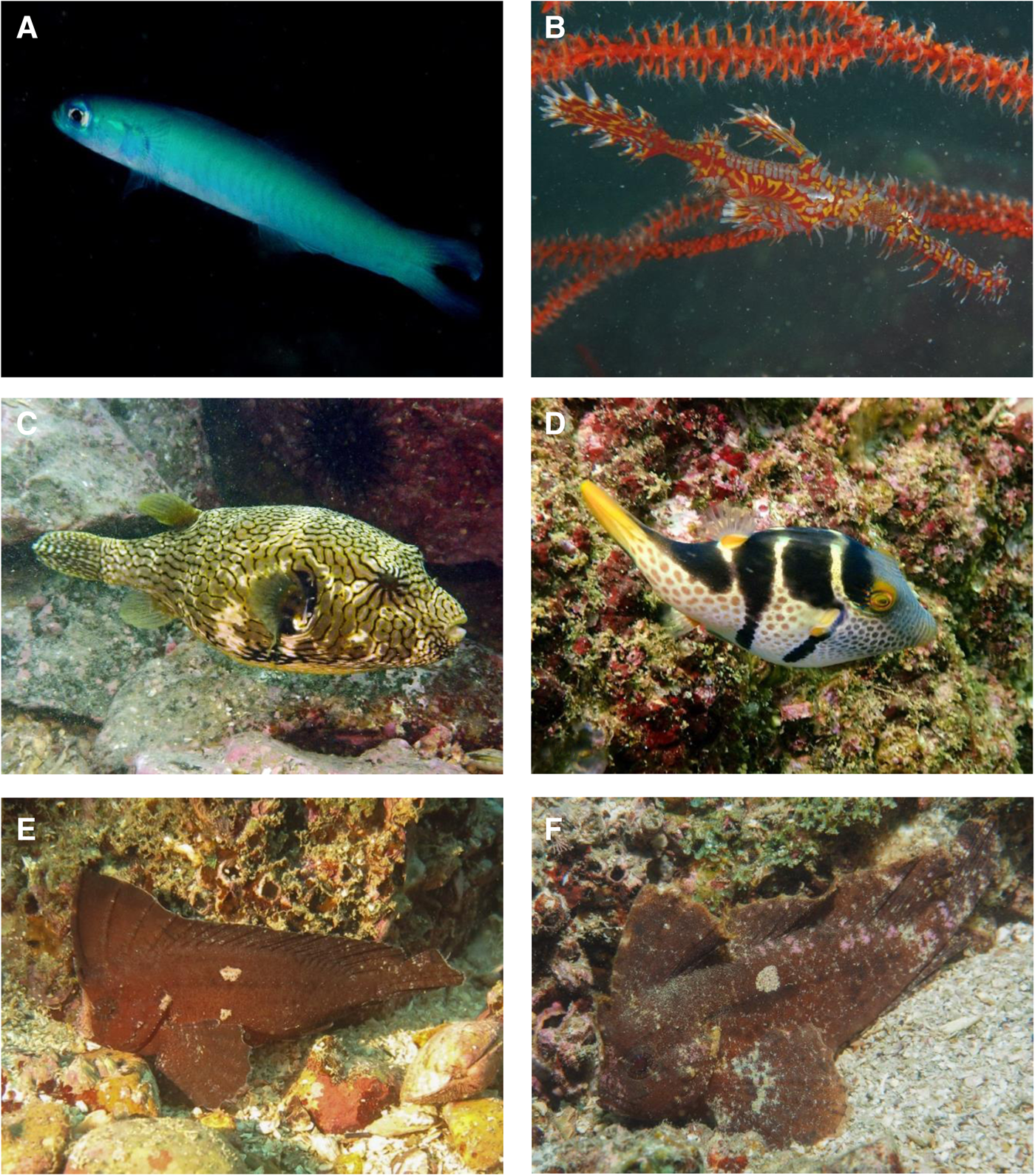

Fig. 7. Newly recorded species in Hong Kong: (a) Ptereleotris heteropteran; (b) Solenostomus paradoxus; (c) Arothron mappa; (d) Canthigaster valentine; (e, f) Ablabys taenianotus. Photographs: 114°E Hong Kong Reef Fish Survey.

Solenostomus paradoxus (Pallas, 1770), family: Solenostomidae

An individual of Solenostomus paradoxus (Pallas, 1770) was observed on 29 September 2021 during daytime (Figure 7b) at Basalt Island (22°18′31″N 114°21′52″E). The individual was ~10 cm in total length, and was found camouflaged among whip corals (Dichotella spp.) at ~10 m deep water. Solenostomus paradoxus is found in the Indo-West Pacific (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022) in at least 25 countries/territories. In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is also recorded in mainland China, Ryukyu Islands and south Taiwan (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Shao, Reference Shao2022).

Arothron mappa (Lesson, 1831), family: Tetraodontidae

An individual of Arothron mappa (Lesson, 1831) was observed on 20 October 2019 during daytime (Figure 7c) at eastern Sharp Island (22°21′46.15″N 114°17′47.41″E) at ~4 m depth. The individual was found swimming near large boulders. Individuals were observed again on at least two separate survey days in 2020, at Basalt Island and Jin Island. Arothron mappa is found in the Indo-Pacific in at least 24 countries/territories, with records in nearby regions including Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Tungsha (Pratas), Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Canthigaster valentini (Bleeker, 1853), family: Tetraodontidae

One individual of Canthigaster valentini (Bleeker, 1853) was observed at Basalt Island (22°18′31″N 114°21′52″E) on 18 May 2019 during daytime (Figure 7d). The individual was ~7 cm in length, and was encountered at ~10 m depth, swimming among large boulders and gorgonian corals. Canthigaster valentini is distributed in the Indo-Pacific, and found in around 40 countries/territories including Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Tungsha (Pratas), Spratly Islands, Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam and Xisha Islands (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008, Reference Shao, Chen, Chen, Huang and Kuo2011; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Chen, Du, Loh, Liao, Liu and Yang2021).

Ablabys taenianotus (Cuvier, 1829), family: Tetrarogidae

A few individuals of Ablabys taenianotus (Cuvier, 1829) were observed at Trio Island (22°18′05.5″N 114°19′09.79″E) during daytime on 9 May 2021, hiding and swaying among seaweed at ~5 m depth (Figure 7e, f). All individuals were of a similar size, estimated to be ~15 cm in total length. Individuals were observed again at the same site on 27 July 2021, and on 1 October 2021 a single individual was observed at another dive site. Ablabys taenianotus is found in at least 15 countries/territories (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022) in the Eastern Indian Ocean and Western Pacific, with records in Taiwan and mainland China (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Huang and Lin2012; Shao, Reference Shao2022). In the proximity of Hong Kong, it is recorded in Pingtong County, Ryukyu Islands and Vietnam (Shao et al., Reference Shao, Ho, Lin, Lee, Lee, Tsai, Liao, Lin, Chen and Yeh2008; Nakae et al., Reference Nakae, Motomura, Hagiwara, Senou, Koeda, Yoshida, Tashiro, Jeong, Hata, Fukui, Fujiwara, Yamakawa, Aizawa, Shinohara and Matsuura2018; Van Nguyen & Mai, Reference Van Nguyen and Mai2020).

Discussion

In total, 50 species were recorded for the first time in Hong Kong through regular underwater visual surveys from 2014–2021 (To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016; Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018). These records were expected by scholars as reef fish species composition in Hong Kong has been poorly described in the past due to a lack of active survey effort (To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016; Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018). Hence, some of the species documented may have simply been overlooked in the past. Although there is not yet sufficient information to put forward a definitive answer to explain this continuous appearance of new species records in local waters, several hypotheses exist, including species arrival through natural dispersion of fish larvae by oceanic currents, such as the Hainan current, the Taiwan current (Cornish, Reference Cornish1999; Sadovy & Cornish, Reference Sadovy and Cornish2000) and possibly the Kuroshio current (Lui et al., Reference Lui, Chen, Hou, Liau, Chou, Wang, Wu, Lee, Hsin and Choi2020).

The possibility of new species arrival is suggested by repeated sightings of several new-to-Hong Kong species that were somewhat regular throughout the survey (To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016; Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018), such as Amblyeleotris japonica (first reported in To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016), and Rhabdamia gracilis (first reported in Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018). However, continuous long-term monitoring and genetic analysis among populations in the region would be required to provide further evidence to support such a hypothesis.

Additionally, most new species records found by the study are tropical species, except Amblyeleotris japonica, which is considered a subtropical species (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). The high number of tropical species sightings along with the repeated sightings of certain new-to-Hong Kong species suggests that the increased sightings of new-to-Hong Kong species might possibly be linked to climate change, as the distribution range of one species tends to expand or shift to higher latitude due to climate change-related drivers such as rise in sea-surface temperature, habitat loss, or increase in extreme events (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Lam, Sarmiento, Kearney, Watson and Pauly2009; Booth et al., Reference Booth, Bond and Macreadie2011; Hollowed et al., Reference Hollowed, Barange, Beamish, Brander, Cochrane, Drinkwater, Foreman, Hare, Holt, Ito, Kim, King, Loeng, MacKenzie, Mueter, Okey, Peck, Radchenko, Rice, Schirripa, Yatsu and Yamanaka2013). However, without robust statistical analysis, it is difficult to conclude that the dominance of new tropical fishes discovered in Hong Kong is related to climate change. Further studies are required to examine the effects of climate changes on local biodiversity.

To determine whether the record of new species was a result of natural processes or artificial introduction, several indicators were used. To & Shea (Reference To and Shea2016) discussed a number of key indicators for differentiating artificially introduced fishes and natural occurring fishes, which include the natural distribution range of the species as documented in existing literature, ease of access of dive sites to fish release activities (especially if an adult fish is encountered where no juvenile or sub-adult individuals of the species were found previously) and the availability of the species in the local aquarium trade. Other indicators include the health of the fish in appearance (fish released from the seafood trade tend to carry injuries from captivity), and presence in habitats not described as the species' natural habitat in existing literature. In addition, artificially introduced individuals might display unnatural behaviours, such as swimming in unnaturally close proximity to diver(s), which is rarely seen in most reef fishes in Hong Kong.

Based on these indicators, there were no clear signs that the discovery of fish species in this study was a result of artificial introduction. For example, Hong Kong sits within the natural ranges of distribution for all fish species described in the study (Froese & Pauly, Reference Froese and Pauly2022). Based on recounts from divers who reported sighting of the described species from underwater visual surveys, most of the individuals spotted were in the sub-adult phase; or relatively small compared with their maximum sizes; and were wary of divers. Encounters with individuals carrying visible injuries that are common in artificially introduced fish or encounters with individuals found in unnatural habitats have not been reported. As far as known, most of the newly recorded species have not been reported to be a popular commodity in local food fish trade (Lau & Li, Reference Lau and Li2000) or aquarium trade (Chan & Sadovy, Reference Chan and Sadovy2000), and are therefore unlikely to be occurring in local waters as a result of fish mercy release activities or escape during transportation.

Implications for marine protected areas (MPAs)

Currently, only 3.7% of Hong Kong's waters are designated as MPAs. However, initial sightings of new species records described in this study have all been made in sites outside the currently established MPAs in Hong Kong, suggesting that potential biodiversity hotspots favouring fish larvae settlement might still be unprotected from anthropogenic disturbances. In particular, numerous new species records described in this study were made in Port Shelter and the Ninepin Group (Table 1), which shelters several dive sites of exceptional reef fish biodiversity, with some sites hosting a species diversity of over 260 recorded species (unpublished data). Unfortunately, there are currently very limited conservation management policies or regulations in place to protect these areas from stressors such as commercial and recreational fishing activities (including but not limited to spearfishing and squid jigging), ghost fishing, marine litter, religious fish release activities, water pollution and unregulated recreational activities (Lee & Lam, Reference Lee and Lam2018). Even though much of marine biodiversity in the region remains unknown, the current findings demonstrate that Hong Kong hosts exceptional reef fish species diversity with potentially more species awaiting discovery and documentation with increased research effort (To & Shea, Reference To and Shea2016; Shea & To, Reference Shea and To2018). While the current study is focused on reef fish, studies focusing on other marine life have also established Hong Kong as a marine biodiversity hotspot, including for amphipods, cephalopods and polychaetes (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Cheng, Ho, Lui, Leung and Williams2017), further indicating that an increase in MPAs in Hong Kong is critical for the conservation of the local marine life.

Table 1. Number of newly recorded species found in dive sites visited in this study

Looking forward, continued research and surveys of marine biodiversity, including reef fish biodiversity, would be crucial to providing foundational support for the informed establishment of effective MPAs to conserve marine biological diversity in Hong Kong. Through understanding species diversity and distribution, continued underwater visual surveys could serve as a primary tool to monitor effectiveness of established MPAs (Edgar et al., Reference Edgar, Stuart-Smith, Willis, Kininmonth, Baker, Banks, Barrett, Becerro, Bernard, Berkhout, Buxton, Campbell, Cooper, Davey, Edgar, Försterra, Galván, Irigoyen, Kushner, Moura, Parnell, Shears, Soler, Strain and Thomson2014), and to continue identifying ecologically sensitive areas in need of protection.

Conclusion

This paper has described the discovery of 31 fish species found in Hong Kong that are new to the official records of Hong Kong. Maintaining a long-term biodiversity database is crucial for managing the local ecological resources. Knowledge and understanding for the local biodiversity are not only the first step towards the proper conservation of species, but also provide a baseline from which further research can be built. It is hoped that the current reef fish database can fill in one of the data gaps for the local biodiversity, enabling better conservation measures for the local marine life, such as by establishing more effectively managed MPAs, and aid future conservation and research work.

Data

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Andy Cornish, Dr Allen To, Prof. Yvonne Sadovy de Mitcheson and Dr Professor Helen Larson, Prof. K.T. Shao and his team (particularly Chen Ching-Yi and Dr Chen Hong-Ming) and Baian Lin for their expert advice and comments provided on the identification of species included in this paper. Thank you to Diving Adventure and Ah Ming of Hong Kong Coastal Activities Association (HKCAA) for providing logistic and technical support to the surveys. None of these findings would have been possible without the help of survey volunteers – in particular, thank you to volunteers who first found this paper's species, photographed the fish and shared the photographs with the survey team or provided their photographs to this paper, including (in alphabetical order) Andrew Fung, Dr Cornish, Dr Allen To, Bosco Chan, Brian Lam, Caron Wong, Dr Calton Law, Cherry Ho, Eric Keung, Gigi Cheung, Grape Tang, Kamy Yeung, Kathleen Ho, Miko Lui, Nicole Kit, Ryan Cheng, Sumi Leung, Tony Liu and Vania Kam. Thank you also to survey volunteers who took note of species observations by recreational divers posted onto social media and suggested the associated dive sites to the survey. Finally, thank you to ADM Capital Foundation for their unwavering support to the survey project and team Immense gratitude is owed to the Swire Group Charitable Trust for providing the funding support for the expense of this publication and of underwater reef fish surveys since 2016.

Authors’ contributions

All authors of the paper were involved in the field survey for reef fish in this study. SKHS was chiefly involved in species identification and verification and the processing of photographs submitted by survey volunteers. All authors prepared the draft of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

The Swire Group Charitable Trust provided funding support for the surveys in which the findings were made and for the expense of this publication. ADM Capital Foundation supported the survey project in kind by the provision of office space and office equipment.