1. IntroductionFootnote 2

Balochi is a largely unwritten language; Balochi written literature is produced primarily by Balochi communities in Pakistan. Educated Baloch in Iran read and write mainly in Persian, although there is a strong writing tradition among Baloch writers and poets along the Coast.Footnote 3 Conversely, there is a rich body of oral literature of various genres in Balochi, which has been passed on from generation to generation. Elfenbein reports that “The literature of Balochi—until quite recently entirely oral and still largely so—consists of a large amount of history and occasional balladry (epic poetry), stories and legends, romantic ballads, and religious and didactic poetry. There is also a large variety of domestic poems i.e., work songs, lullabies, and riddles”.Footnote 4

1.1 State of storytelling across the dialects

The following is a brief comment on the state of storytelling and narration in Balochi.Footnote 5 Balochi varieties spoken along the coast have a strong tradition of storytelling and reciting songs. One can find an expert storyteller in almost every village. In fact, the tradition of the storytelling and reciting songs accompanies the life of Baloch people in this region from cradle to grave, owing to a strong cast system; as both narration and the reciting of songs are a means of income for lower caste communities such as the loḍi and Afro-Baloch. The term Afro-Baloch refers to the people of African origin along the southern coast of Iran who adopted the Balochi language, see for a more detailed discussion on Afro-Balochi communities,Footnote 6 and regarding their language situation see.Footnote 7 The oral narration language in these regions is just Balochi.Footnote 8

Balochi dialects spoken in Fars province, have a dynamic storytelling tradition than reciting songs in Koroshi. In the northern part of Fars, however, they prefer to narrate their stories in Qašqā’i. In contrast, Koroshi communities living in Southern of Fars province and in Hormozgan have a dynamic storytelling tradition in Koroshi. The oral narration language in the Koroshi communities varies across the regions. For instance, the Koroshi communities in northern Fars use both Koroshi and Qašqā’i, the Koroshi communities in Southern Fars use Koroshi, while the Koroshi communities in Hormozgan use both Koroshi and Balochi.Footnote 9

The tradition of storytelling in the Balochi communities in North of Sistan and Balochistan such as Zabol and Zahak has almost disappeared from society. However, the tradition of the reciting songs in Persian Sistani and to some extent in Balochi is still common among the older generation. The only exceptions to this generalisation are among the Balochi communities who are nomadic and among Baloch refugees from Afghanistan. The oral narration language in these regions is in Persian Sistani and Balochi.Footnote 10 Note: a mixture of Persian Sistani and Balochi has been attested in their narration. For instance, Baloch speakers recite the songs in their tales in Sistani Persian and the same is true for Sistani Persian storytellers.

1.2 The Data

Balochi is an Iranian language belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. It has three main dialects: Southern, Eastern, Western Balochi. Each of these dialects presents its own sub-divisions.Footnote 11 Balochi is mostly spoken in south-eastern and South-West Iran and south-western Pakistan, and also in Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Oman, and the UAE. The number of speakers can be estimated at about 7–8 million at least.Footnote 12 The dialects under study are the Koroshi (KoB), Sistani (SiB) and Coastal (CoB) dialects of Balochi.

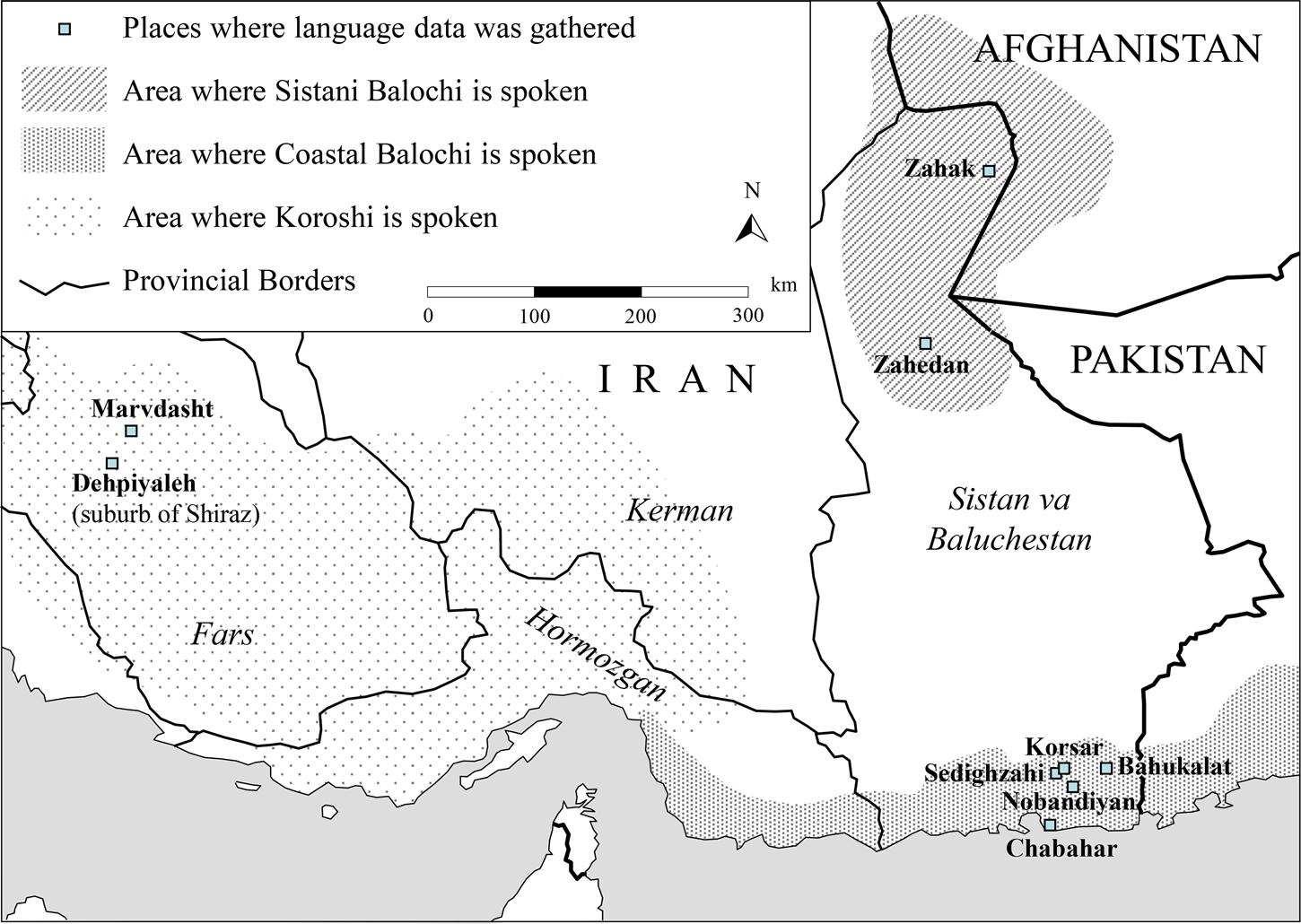

The language data used for the analysis of the present paper are extracted from published corpora by AxenovFootnote 13, Barjasteh DelforoozFootnote 14 and Nourzaei et al.,Footnote 15 Nourzaei,Footnote 16 and Nourzaei.Footnote 17 Additionally, I used unpublished texts from Coastal regions Nourzaei and Korn's unpublished corpora.Footnote 18 Map (1) one presents the location of the dialects mentioned above. Coastal Balochi is indicated as “Southern Balochi” in the map. Sistani refers to the Iranian part of the areal that is indicated as “Western Balochi” and Koroshi is indicated as such.

1.3 Background of the storytellers

I now comment briefly on the social background of the storytellers who feature in my research.Footnote 19 All of my storytellers from CoB are without a school education except two male storytellers who have a primary school education (grades two and three respectively). Two of my female storytellers have an Islamic school education. The storytellers were famous either for reciting the songs or for narrating folktales in their villages.

The storytellers from KoB excluding one young female storyteller (who has a high school education) have a basic school education (grades two and six respectively). My male storytellers were famous for telling stories among their communities.

Finally, the SiB storytellers except one male speaker with a basic school education (grade six) do not have a school education. However, one of the female storytellers has an Islamic school education. She is quite famous for reciting songs in public.Footnote 20 See Nourzaei (2017) for more details regarding their social background.

1.4 Terminology and definitions

Tail-head linkage: “the repetition in a subordinate clause, at the beginning (the ‘head’) of a new sentence, of at least the main verb of the previous sentence (‘tail’)”.Footnote 21

Repetition: “contiguous units that occur more than once in the same way or form and refer to the same event in the story”.Footnote 22

ke: general subordinating conjunction marker.Footnote 23

o: associative conjunction maker.

Default encoding:Footnote 24 the most frequent encoding for each context, based on a statistical count in a large number of texts.Footnote 25

Highlighted: “material that is marked as being of more importance than other material in the immediate context”.Footnote 26

Marked encoding:Footnote 27 non-default encoding, which means that other means of encoding are used than the statistically most frequent one.Footnote 28

S1 context: a context where “the subject is the same as in the previous clause and sentence”; e.g., John goes to the university. He studies law.Footnote 29

Highlighted: “material that is marked as being of more importance than other material in the immediate context”.Footnote 30

New narrative unit: “an event, section, or subsection of a narrative”.Footnote 31

Climax: the most intense, exciting, or important event in the story.

Development marker: marks the end of one package of events and the opening of a new package of events in the story.

Written style: typified by having a lot of pronouns, long sentences, subordination and conjunctions.

Oral style: typified by having a lot of pro drops, short sentences, oral technics such as tail-head linkage, repetitions, juxtapositions, etc.

Distinction between repetition and tail-head linkage

The main distinction between repetition and tail-head linkage in Balochi is intonation contour. The key feature of repetition is that the repeated part follows the intonation of the first part. So, if the first part has falling intonation, then the second part will start at about the same level and also have falling intonation. It will never be the case that the first part has falling intonation at the end, while the second part ends with rising intonation. In contrast, the key feature of tail-head linkage is that the repeated part (tail) has falling intonation, whereas the second part (head) starts at a higher pitch and has rising intonation at the end.Footnote 32

In addition, repetition is more commonly found within paragraphs,Footnote 33 while tail-head linkage occurs between paragraphs. In other words, tail-head linkage connects two paragraphs together. The main common feature between repetition and tail-head linkage is that both are used only when the subject is the same as in the previous clause and sentence.

2. Type of linking and frequency of their usage across the dialects

The structure of Balochi syntax varies across the dialects. Balochi dialects spoken in the South to East have preserved an archaic syntactic structure. In contrast, Balochi dialects in the North demonstrate a developed syntactic structure similar to New Persian. This may be due to direct contact with Persian speakers and education, media etc., or it could be an internal development. Regardless of the simplicity and complexity of Balochi syntactic structure, Balochi storytellers use different devices to link passages in their oral narrative texts, and there is variation across the dialects. I discuss these devices in the following sections.

2.1. RepetitionFootnote 34

Repetition is the most significant linking device to connect clauses inside paragraphs at a discourse level. There are two types of repetition in oral narrative texts:

i. Those that repeating the same verb form.

ii. Those that repeating a whole clause.

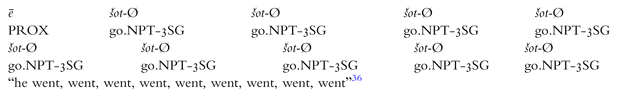

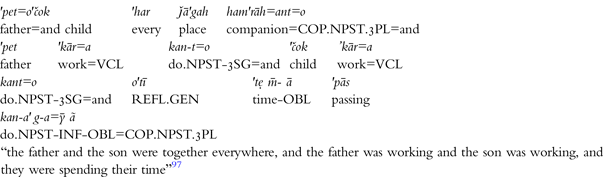

Passage 1 exemplifies repeating the same verb form of the previous clause.Footnote 35 The first instance of šot ‘went’ has raising intonation, and the following repeated verbs šot ‘went’ have the same intonation.

Ex. 1) repetition with the same verb form (CoB)

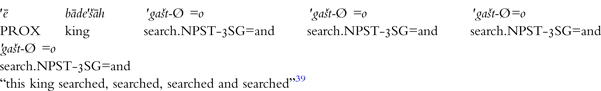

In the following passage, (c)Footnote 37 ‘the girl became aware’ has falling intonation, then (d) ‘the girl became aware’ has the same intonation. Thus, this passage exemplifies repeating all the clause of the previous clause.

Ex. 2) repeating all the clause (SiB)

In addition to the prototypical repetition, the following non-prototypical types have been attested across the dialects.

i. Repeating the same verb form with conjunction =o

ii. Repeating the whole clause with conjunction =o

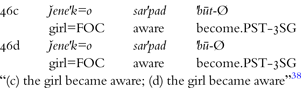

Passage 3 exemplifies repeating the same verb form of the previous clause with conjunction =o. The first verb 'gašto ‘searched and’ has falling intonation, and the following repeated verbs ‘searched and’ have the same intonation.

Ex. 3) repeating the same verb form combine with conjunction o (TB)

The constituent that is most commonly repeated is a verb. However, the data reveals that the repeated part can also be an adverbial phrase e.g., 'šapē 'ǰāē o'rōčē 'ǰāē o'šapē 'ǰāē o'rōčē 'ǰāē watrā rasēnt ‘He kept walking (lit. one night in one place and one day in one place, one night in one place and one day in one place), until he arrived’. This type of repetition occurs very infrequently.

2.1.1 Motivation for repetition

Repetition can occur in the discourse when the subject is the same as in the previous clause. The motivation for repetition depends on the subject of the verb.

The main motivations for the default subject repetition (see section 1.4) are:

(a) To enhance the coherence of the text.

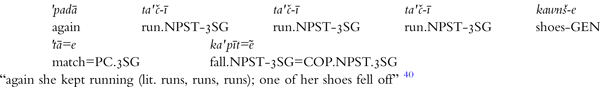

In the following passage, the motivation for repeating the same verb form ta'čī ‘runs’ is to enhance the coherence of the text.

Ex. 4) repetition to enhance the coherence of the text (CoB)

(b) To demonstrate duration of the time and space in the storyline.

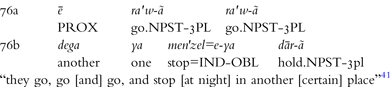

In the following passage, the storyteller repeats the verb ra'wã ‘go’ is to indicate the passing of time and space from the previous place where the king returns to his county to the second place where the Mullah came with a bad attention to the king's wife.

Ex. 5) repetition to demonstrate duration of time and space (CoB)

(c) To show duration of an action until an end point.

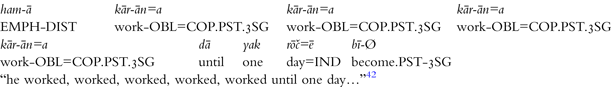

Sometimes the type of repetition described in (b) precedes the following adverbs tā, dẫ, dẫke, ‘till, until’ as in the following passage.

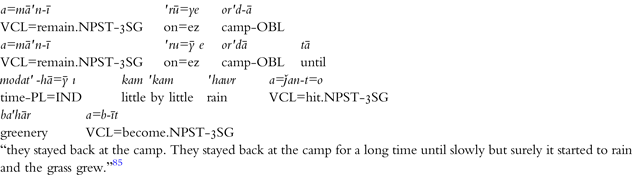

Ex. 6) repetition to demonstrate duration of the time and space with an end point (CoB)

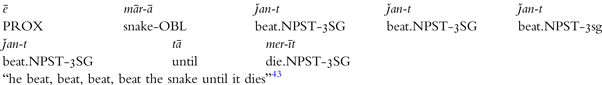

In the following passage, the storyteller repeats the verb ǰant ‘beat’ to present a completed action of killing the snake. This is reinforced by the lengthening of the vowels.

Ex. 7) Repetition to show an accomplishment of an action (SiB)

The main motivation for the marked subjectFootnote 44 repetitions is highlighting; e.g., highlighting a speech, action, event, or an important element in the story. In the following passage, the subject ‘the girl’ in (d) refers to the same person as ‘the girl’ in the previous clause, (c). The motivation for the marked repetition is to highlight the importance of the girl's speech relating to warning the boy of the approaching Mullah, which is significant for the rest of the story. See for more passages with other type of highlighting Nourzaei (2017).

Ex. 8) marked subject repetition to highlight the following speech (SiB)

2.2 Tail-head linkage

Like the repetition device, tail-head linkage is also common in oral narrative texts. There are two types of tail-head linkage: Prototypical types of tail-head linkage are as follows:

i. Repeating the last constituent of the clause (e.g., the verb) from the previous paragraph

ii. Repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph

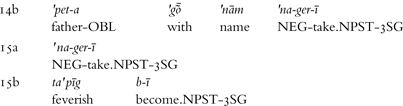

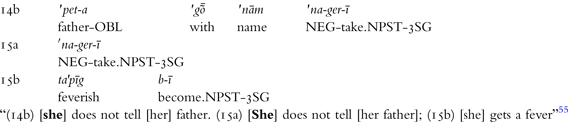

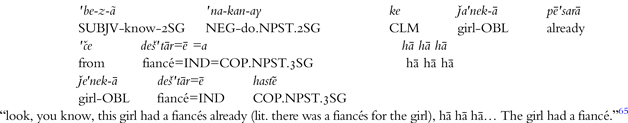

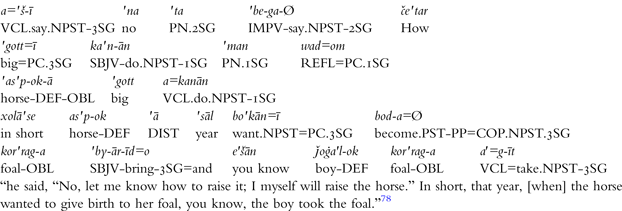

Passage 9 exemplifies repeating the verb in last constituent of the previous paragraph. The verb ‘did not tell’ in (b), has falling intonation, whereas (a) ‘did not tell’ starts at a higher level and has rising intonation at the end.

Ex. 9) Tail-head linkage (CoB)

“(14b) she did not tell [her] father. (15a) She did not tell [her father]; (15b) she got a cough”Footnote 46 The most common repeated constituent from the previous paragraph is the verb. In some passages, however, tail-head linkage is with a noun.Footnote 47 Guthrie uses the term “hook words”, and maintains “a rhetorical device used in the ancient world to tie two sections of material together. A word was positioned at the end of one section and at the beginning of the next to effect a transition between the two”.

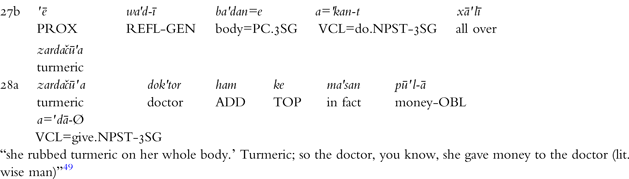

Passage 10 exemplifies repeating the same noun form in last constituent of the previous clause. The first noun in (b) zardačūˈa ‘turmeric’ has falling intonation, the following repeated non zardačūˈa turmeric has rising intonation at the end.

Ex. 10) tail-head linkage with a hook word (KoB)

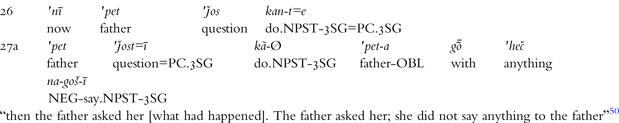

Passage 11 exemplifies repeating all the clause from the previous paragraph. The first verb in (26) ‘the father asks her’ has falling intonation, whereas (27a) ‘the father asks her’ starts at a higher level/pitch and has rising intonation at the end.

Ex. 11) tail-head linkage (CoB)

Note that the repeated part is not always the same as in the previous paragraph. For instance, the repetition of head in 27a is a variation of repetition of 26. Morphologically, it contains all the elements, but the form is different (see also passage12).

In addition to the prototypical types the following non-prototypical types have been attested across the dialects.

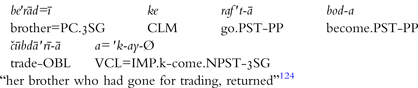

i. Repeating part of the clause as tail from the previous paragraph combined with the general subordination marker ke

ii. Repeating part of the clause as tail from the previous paragraph combined with conjunction =o

Passage 12 exemplifies repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph combined with ke. In (b) ‘[she] suddenly blows on this bridle inside her hand, this girl’ has falling intonation, whereas (a) ‘when the girl blows on [the bridle] starts at a higher level/pitch and has rising intonation at the end.

Ex. 12) Repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph combined with ke (SiB)

Passage 13 exemplifies repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph combined with conjunction =o. In (52) ‘this one made himself a crazy camel’ has falling intonation, whereas (53) ‘He made [himself] a crazy camel, and’ starts at a higher level/pitch and has rising intonation at the end.

Ex. 13) Repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph combined with o (SiB)

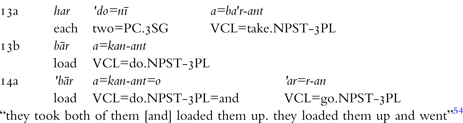

Passage 14 exemplifies repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph combined with conjunction =o. In (b) ‘they loaded them up’ has falling intonation, whereas (a) ‘they loaded them up and’ starts at a higher level/pitch and has rising intonation at the end. conjunction =o.

A question that might be posed is whether the conjunction =o is part of the clause or not. The recordings do not show a pause between the tail-head linkage and =o. The coexistence of tail-head linkage with =o might be a secondary development function of =o as opening a new paragraph.Footnote 52

Ex. 14) repeating the whole clause from the previous paragraph combined with =o (KoB)

2.2.1 Motivations for tail-head linkage

Like repetition, motivation for tail-head linkage depends on the subject of the tail-head linkage. The attested motivations for default tail-head linkage (see section 1.4) are as follows.

a) To enhance coherence in the text

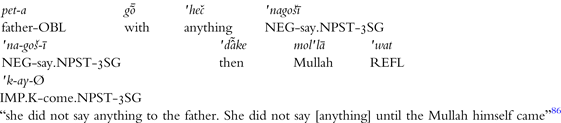

In the following passage, the repeated ‘she did not say’ (a) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for the unmarked tail-head linkage is to enhance coherence in the text.

Ex. 15) tail-head linkage to maintain the coherence of the text (CoB)

b) Duration of time and space in the story

In the following passage, the repeated ‘he run’ (a) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for the unmarked tail-head linkage is to indicate a change of time and space from the previous place where the king's son was chased by the school children to the king's palace where they are about to kill his horse. The repeated verb is reinforced by the lengthening of the vowels. Note. In contrast to CoB dialect, KoB storytellers do not use a long repetition of the same verb form (see passage 1).

Ex. 16) tail-head linkage for duration of time and space (KoB)

c) As a hesitation device

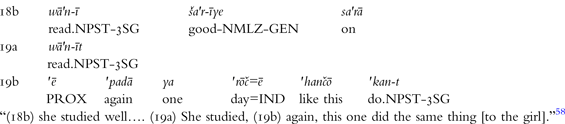

In the following passage, the repeated ‘getting thinner’ (19) is an example of tail-head linkage. The storyteller uses the unmarked tail-head linkage as a hesitation device to give herself some time to remember what happens next in the story.

Ex. 17) tail-head linkage as a hesitation device (KoB)

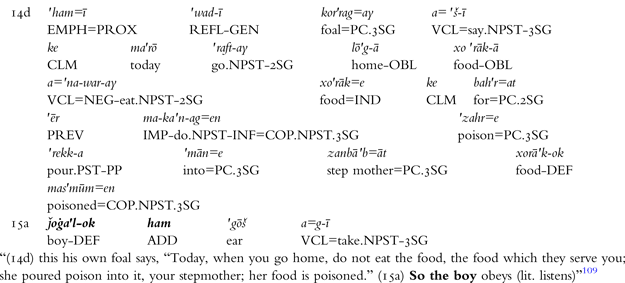

d) The same function as a development device

In the following passage, the repeated ‘she studies’ in (19a) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for the unmarked tail-head linkage is to close the previous event where the king's daughter for a while studies very well at school and to begin a new event in the story where the Mullah starts to give hard time to the king's daughter again.

Ex. 18) unmarked tail-head linkage preceding a development device (CoB)

e) To introduced a climax of the story

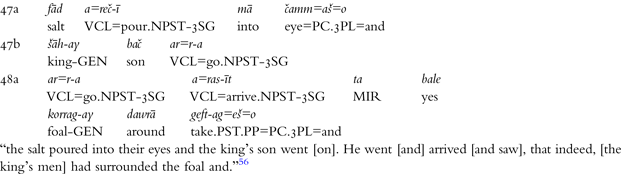

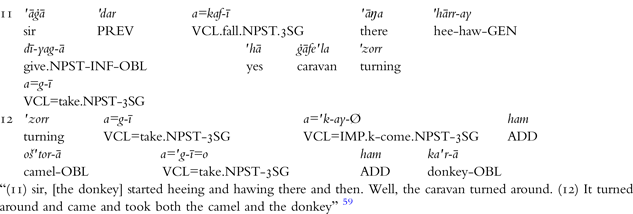

In the following passage, the repeated ‘It turned around and came in (12) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for the unmarked encoding tail-head linkage to slow down the story and introduces one of the significant climaxes of the story where the caravan returns and captures both the donkey and the camel in the story.

Ex. 19) unmarked tail head-linkage at the climax of the story (KoB)

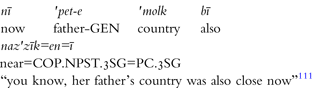

f) Prior to the introduction of important background information in the story

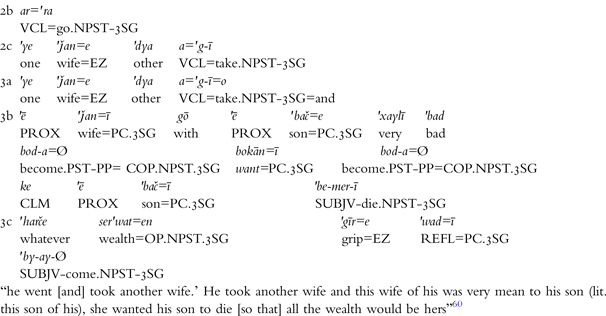

In the following passage, the repeated ‘he took another wife in clause (3a) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for the unmarked encoding to introduce important background information regarding the king's new wife into the story.

Ex. 20) tail-head linkage prior to the introduction of important back ground information (KoB)

g) to resume the storyline

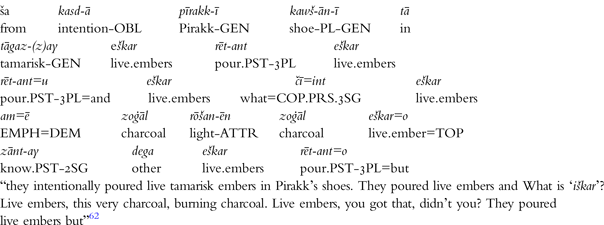

Storytellers can be interrupted at different stages of their narrations. One of the most common interruptions is when the storyteller explains some points to the audience. He/She then resumes the storyline by repeating the last sentence.Footnote 60 In the following passage, the audience asks for the meaning of eškar ‘live.ember’. The storyteller stops his narration to explain it to them. Then he returns to the storyline by repeating the verb of the previous passage.

Ex. 21) Repetition to show resumption to the storyline (SiB)

The main motivations for marked tail-head linkages are as in the following:

a) To mark the beginning of a new narrative unit

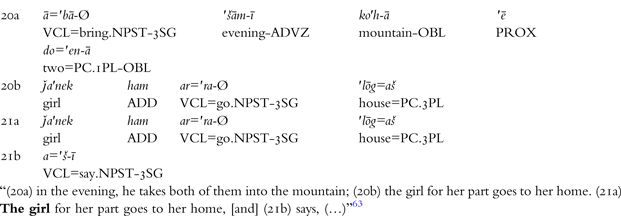

In the following passage, the repeated ‘the girl for her part goes to her home’ in clause (21a) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for such over-encoding is to mark the beginning of a new narrative unit. This is because there is an attention shift from the place where Alamdar stopped the girl, her father and her brother, to the place where the girl reported to her family what happened to her father and brother.

Ex. 22) tail-head linkage at the beginning of a new narrative unit (KoB)

a) Highlighting (highlighting the following event, the facts, and the significant elements in the story and etc.)

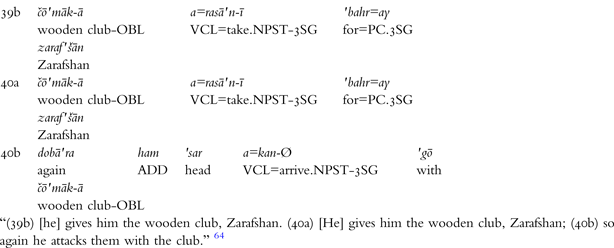

In the following passage involving tail-head linkage, the subject ‘Zarafshan in clause (40a) ‘Zarafshan gives him the wooden club’, is an instance of the marked encoding. The motivation for the marked encoding is to highlight the following event in the story where Alamdar attacks to the people with the club and bits them.

Ex. 23) tail-head linkage for highlighting the following event (KoB)

Similarly, to the un-marked tail-head linkage, the marked tail-head linkage appears in the oral narrative texts when the storyteller resumes to the storyline due to either distraction or to remember what is next in the story. Note that it has been attested in my corpus where the storyteller laughs to some events in the story during her narration. She stops laughing and resuming to the storyline by repeating the last sentence. As in the following passage.

Ex. 24) Repetition to show resumption to the storyline (CoB)

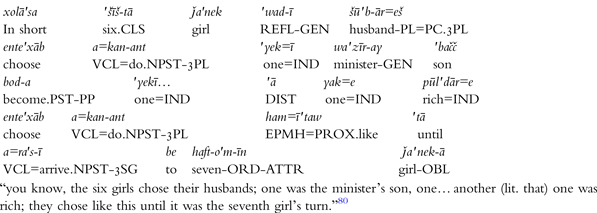

Similar to the un-marked tail-head linkages the marked one also attested when the narrator gives time her/himself to remember the rest of the story. In the following passage, the repeated ‘The king had seven daughters’ (66a) is an example of tail-head linkage. The motivation for it is the narrator gives some times to himself to remember the next part of the story. In fact, the next part of the story starts in 66b.

Ex. 25) Tail-head linkage to remember the rest of the story (KoB)

The frequency and types of repetition and tail head-linkage are not the same across the dialects. The four Balochi dialects being studied use repetition and tail-head linkage to a different extent which can be represented on a cline. CoB,Footnote 66 the most conservative dialect in the present study, displays a high tendency to use prototypical repetition and tail-head linkage in its narrations. It is situated at one end of the cline. KoB is located in the middle, with older narrators in particular having a strong tendency to use tail-head linkage.Footnote 67 The narrations by the younger generation reveal almost no trace of using tail-head linkage and repetition.Footnote 68 SiB and TB are situated at the other end of the cline, having a very low tendency to use repetition and tail-head linkage. When they are attested, they may be in combination with conjunctive =o ‘and’ and the general marker of subordination ke. Such is the case in Barjasteh Delforooz's corpus (eighteen passages), Axenov's corpus (eight passages) and in my own corpora (twenty passages). I found only eight examples of prototypical tail-head linkage in AxenovFootnote 69 and five in my own unpublished corpora.

The following passage demonstrates prototypical tail-head linkage in TB taken from Axenov.Footnote 70

Ex. 26) Prototypical tail-head linkage (TB)

This passage could suggest that both Sistani and Turkman Baloch storytellers used to use prototypical tail-head linkage in their narrations before starting to linking them with the subordination marker -ke and conjunctive =o. One could assume that the attested examples are a remnant of an earlier stage when prototypical repetition and tail-head linkage were common in this dialect.

2.3 Development devices

In addition to the use of tail-head linkage to connect two paragraphs within a discourse, there is another type of connective that marks the development of the oral narrative text. SiB presents a variety of development devices (see Barjasteh Delforooz for a detailed description of them in SiB).Footnote 72 The most common development devices attested in the SiB corpora are: āxer/āxerā ‘at last, finally, in the end’, goṛān\goṛā and bad ‘then, after that, next’, ta/tā ‘until, as soon as’, bass ‘just, just then, immediately after that’, xayr ‘well’, belaxara ‘finally’ and ta e ki ‘until that’.

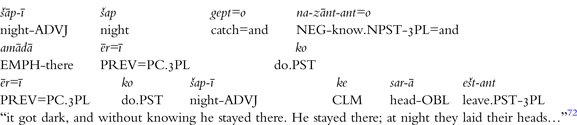

In addition to these connectives, the word īččī ‘well’ and the conjunction o have been attested as markers of development in my data, though Barjasteh Delforooz makes no reference to them.Footnote 73 In the following passage, the narrator uses the word īččī ‘well’ to close the previous even where the youngest son goes and steals one pieces of golds and jumps to a new event where their father dies.

Ex. 27) Development device (SiB)

In SiB, a development device always appears at the beginning of the clause as in passage 27. However, it has been attested sporadically in second position in the clause in Barjasteh Delforooz's corpus with some of the words listed above such as goṛān\goṛā. Footnote 75

In KoB, the development devices are not as diverse as in SiB. The most common ones are: xolāsa, Footnote 76 in short’, tā, ‘till, until’, goda and bad, ‘and then, afterwards’. Apart from ‘goda’, which is an original Balochi word, the rest of these devices are most probably a borrowing from Persian.

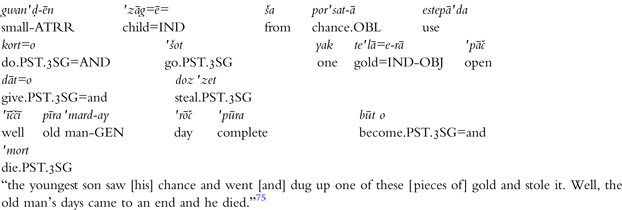

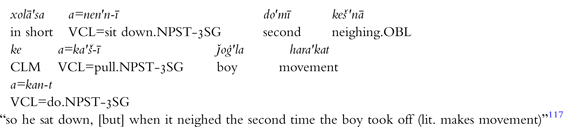

As a development device, xolāsa ‘in short’, indicates a temporal break with a lapse of time. This device introduces a new development in the narrative by signalling the close of one set of events and the beginning of another set that immediately follows. In the following passage, the narrator employs xolāsa to close the conversation between the king's son and the horse and to introduce that a new event in the story.

Ex. 28) Development device (KoB)

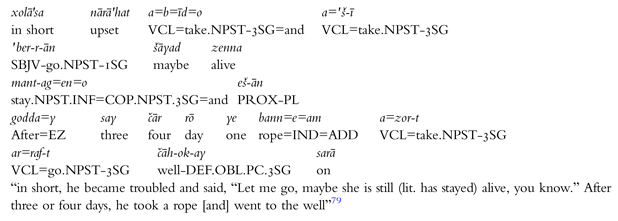

goda bad, badke ‘then’, afterwards, after that, after’ is used in my oral narrative texts to introduce what happened next in the story. In the following passage, godda ‘after’ indicates the passing of three and four days before the man took a rope and went to the well.

Ex. 29) Development device (KoB)

The development device tā ‘till, until’ has both temporal and spatial meanings. It is used to mark the end of a development unit. This is illustrated in the following passage.

Ex. 30) Development device (KoB)

A combination of two development devices has also been attested, such as tā xolāsa and tā bad in.Footnote 80

In CoB, the most common development devices are: goṛā, ‘then, after that, next’ nī ‘then, now’, āxer, ‘at last, finally, in the end’, dẫke, dan, and tā ‘until, till’ and xayer ‘well’. goṛā, nī and dẫke, dan, and tā are the most frequent development markers. Their function is similar to KoB and SiB.

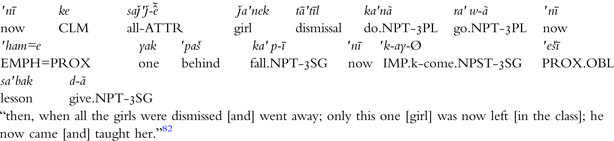

In the case of nī, beside its function as a development device, it also links clauses inside a paragraph. It could be that its function as development device is a secondary function as in the following passage:

Ex. 31) nī in (CoB)

In contrast to the SiB dialect, both KoB and CoB use unmark tail-head linkage as a development device in the discourse as in passage (18). However, it has been attested in Turkman Balochi.Footnote 82

The position of the development devices in KoB and CoB is very interesting.

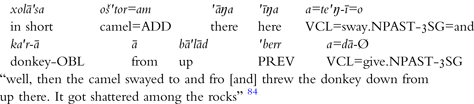

(a) They appear alone at the beginning of the paragraph. In the following passage, the narrator uses the lexical development device xolā'sa to close the previous group of events where the camel and the donkey has a long discussion and open a new event where the camel takes an action and throws the donkey down the hill.

Ex. 32) Development device (KoB)

(b) A development device also accompanies tail-head linkage. In the following passage, the narrator employs both tail-head linkage and the development device tā to show the passing of time in the story, where it takes a long time that both the camel and donkey stays on the camp until the spring arrives. The frequency of this type is much higher than the development devices alone in both dialects.

Ex. 33) The coexistence of a development device and tail-head linkage (KoB)

In the following passage, the narrator uses both tail-head linkage ‘nagošī’ and the development device ‘dẫke’ to close the previous group of events where the king's daughter came back from school to the palace but at the palace, she does not say to his father what has been happened to her at school, and to open a new event where the Mullah comes to the king and complains about her daughter.

Ex. 34) The coexistence of a development device and tail-head linkage (CoB)

The coexistence of lexical development devices with unmarked tail-head linkage in both KoB and CoB confirms that development devices are rather new in these dialects and they have not become systematised as in SiB. In addition, the usage of tail-head linkage with the same function as a development device in CoB and KoB, and the existence of some remnants of tail-head linkage in TBFootnote 86 strengthens our hypothesis that before lexical development devices appeared, the norm was using tail-head linkage in the same way as a development device in Balochi.

So far, I have discussed how paragraphs are linked together at the discourse level. Now I will discuss how the clauses are linked together at the discourse level in the following sections.

2.4 Coordinating strategies

Clauses in the Balochi dialects being studied are coordinated through juxtaposition (asyndetic coordination) of clauses or the use of coordinating conjunctions (syndetic coordination).

2.4.1 Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is a common means of coordinating clauses to associate them in Balochi and other Iranian languages.Footnote 87 Nourzaei et al. report that, “Such events are not portrayed as distinct, but as part of a whole; the one flows into the next. Rising intonation at the end of each clause is the only means by which the coordinated structure can be recognized”.Footnote 88 The following passage illustrates this.

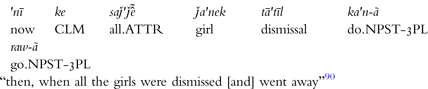

Ex. 35) Juxtaposition (CoB)

Similar to repetition and tail-head linkage, CoB and KoB have the highest frequency of juxtaposition across the dialects with (54 and 40 tokens respectively). SiB demonstrates the lowest frequency of juxtaposition with (10 tokens).Footnote 90 My data demonstrates that in fact, juxtapositions in SiB has even been started to be replaced with conjunction =o ‘and’. In many contexts where one could expect for a juxtaposition, the narrator employs the conjunction =o.

2.4.2. The associative conjunction =o

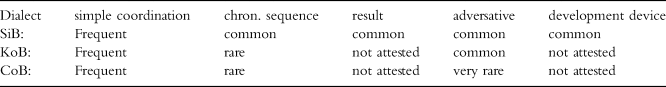

The most common coordinating conjunction across the dialects is expressed by =o. It has two allomorphs as wa, and o. Its function is always associative. It is used to associate clauses when there are various semantic relationships between them. The range of sematic relationships between clauses vary. The following table demonstrates a summary of the range of semantic relationships regarding to the associative conjunction =o between clauses across the dialects.

Table 1. summary of the rage of semantic relationships regarding to the associative conjunction=o

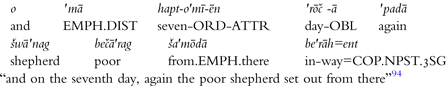

For SiB, Barjasteh Delforooz reports the following contexts: when the events being coordinated are not in chronological sequence (“simple coordination”), when they are in chronological sequence, when they introduce the result of the previous event, and when the two clauses are in an adversative relationship.Footnote 91 However, my corpus demonstrates that associative conjunction =o also functions as a development device. In the following passage, the narrator uses the associative conjunction =o to close the previous event in the story where the merchant and his family decide how to reject the shepherd's son's proposal and jumps on a new event where after passing seven days, the shepherd comes far way to receive the merchant's answer regarding his son's proposal.Footnote 92

Ex. 36) Associative conjunction (SiB)

In KoB, in contrast to SiB, this element is utilised in more limited contexts. Nourzaei et al. 2015 reports the following contexts in which it is used: simple coordination and adversative. The sporadic use of =o has also been shown in the chronological sequence contexts in.Footnote 94

In CoB, the associative conjunction=o is found in the following contexts: simple coordination, which has a high percentage usage in the corpus, adversative (just once appeared in the corpora). Its usage in chronological sequences contexts is very rare. It has been attested very sporadically only by one of my storytellers. One of his texts published inFootnote 95 as in the following passage:

Ex. 37) The associative conjunction=o (CoB)

Comparing the range of semantic relationships of associative conjunction=o across the dialects could suggest that the original usage of associative conjunction =o most probably was as a simple coordination. Extending its usages to other contexts such as indicating chronological sequence, adversative, resultative, and also its usage as a development device is its later semantic development.

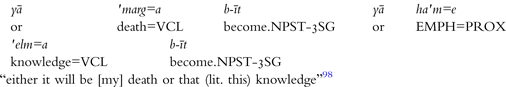

2.4.3 Disjunctive conjunctions

Clauses in a discourse can also be linked by a disjunctive conjunction, of which I discuss two types: positive disjunction (‘or, either … or’) and negative disjunction (‘neither … nor’).

In SiB, the common positive disjunctive conjunction is yā ‘or’ which can also be repeated as yā…yā (na…na) ‘either…or’. There are 10 tokens in Barjasteh Delforooz's corpus and 28 tokens in mine. The frequency of the simple disjunctive conjunction yā ‘or’ is higher than the repeated yā…yā ‘either … or’, which is illustrated in the following passage.

Ex. 38) Disjunctive conjunction (SiB)

For KoB, Nourzaei et al. report that the common disjunctive conjunction is yā which can also be repeated as yā…yā ‘either’.Footnote 98 There are 22 tokens in the corpora.Footnote 99 In both dialects there are very few remnants of expressing disjunction through juxtaposition. In Barjasteh Delforooz‘s corpus disjunction is expressed only twice through juxtaposition.Footnote 100

In CoB, in contrast, the most common means to express disjunction is juxtaposition. However, one of my storytellers uses disjunctive yā ‘or’, (five times) and yā…yā (once).Footnote 101 Note that aga ‘if’ is also used for disjunction in this dialect.

Ex. 39) disjunctive conjunction (CoB)

The negative disjunctive combination na… na ‘neither…nor’ is rarely used across the dialects. It has been attested (eight tokens) in SiB (three tokens),Footnote 103 in KoBFootnote 104 and just once in CoB.Footnote 105

It seems that the development of a specific disjunctive marker (as distinct from juxtaposition) is rather new across the Balochi dialects. Both SiB and KoB due to contact with Persian have a tendency to use it, whereas for most of my CoB narrators except one who is traveling around, the disjunctive conjunction ‘neither… nor’ is not attested. So, a question which might be posed is whether a disjunctive conjunction exists in their daily usage or whether it simply didn't feature in their oral stories.

2.4.4 Additive

The most common additive across the dialects is ham/(=am/om) and hã. It has been attested as both a free word and a clitic. SiB and CoB have the highest frequency of additives across the dialects with (19 and 12 tokens respectively) and KoB displays the highest frequency with (57 tokens).

The common function of this additive is similar to ‘also, as well, and too’ in English. So far, the previous researcher reported other contexts in which it is used in SiB.Footnote 106 KoB uses the particle ham in a way that is not attested in SiB or CoB. When a reported speech in KoB is followed by a “response proposition” which “is anticipated by the stimulus [i.e., the reported speech], fulfils the conditions of the stimulus, or is closely associated with the stimulus”Footnote 107 then the response is introduced with an overt reference to the respondent, to which is attached the additive enclitic. Consider the following passage:

Ex. 40) S2 NP in connection with the particle ham

In the above passage, the enclitic ham adds the expected result to the speech that stimulated it.Footnote 109 The exact function of this conjunctive requires further research in Balochi dialects.

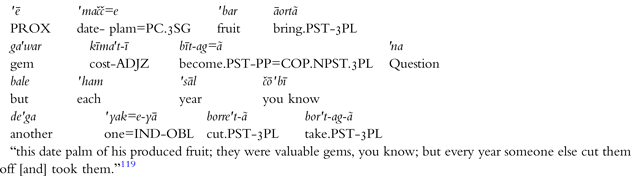

Note that it has been attested in the CoB data a construction with bī ‘also’ as in the following passage. This construction might be a borrowing from Urdu since it has not been attested in KoB and SiB.

Ex. 41)

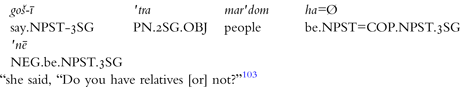

2.5 Adversative

The most common words which express an adversative meaning in SiB are mage, bale, ama and o ‘but’. Barjasteh Delforooz gives a detail description of their functions, which my data also confirms it.Footnote 111 It is more likely that SiB speakers have borrowed them from Sistani Persian due to the close contact.

An adversative relationship can also be expressed via juxtaposition in SiB. However, their frequency is very low. In my large corpora the adversative was attested only onceFootnote 112 and five instances in Barjasteh Delforooz's corpusFootnote 113 via juxtaposition. These passages indicate the remnant of using juxtapositions to express an adversative meaning in SiB.

The most common way to express adversative meaning in KoB is via juxtaposition.Footnote 114 However, it has been attested both wale, walī ‘but’ most probably copied from Persian which occurred (in twelve passages) in the corpora.Footnote 115 This demonstrates that this borrowing from Persian is rather new in this dialect because it has not been systematised in the language.

Ex. 42) Adversative (KoB)

Note that it has been attested =o and ke also function as adversative in discourse, but their frequency is very low.Footnote 117

Similar to KoB the data demonstrates that high frequency of adversatives in the discourse expresses through the juxtaposition in CoB. It has been attested only one lexical word bale, ‘but’ which functions as adversative as in the following passage:

Ex. 43) Adversative (CoB)

This observation leads us to conclude that Juxtaposition could reveal the earlier stage of expressing adversative across the dialects before development of adversative words.

2.6 Subordination

All Balochi dialects under study make use of general subordinating conjunction ke to introduce complement clauses, relative clauses and adverbial clauses see in.Footnote 119 What is interesting here among these dialects and worthy to be discussed is the issue of relative clauses.

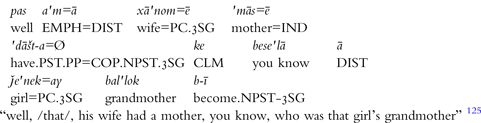

Subjects, objects, and adjuncts can all be relativised. Relative clauses are introduced with the subordinating conjunction ke. The dialects show a different strategy towards using of relative clauses. CoB hardly uses the relative clauses.Footnote 120 It means that the relative clauses expressed in two separate clauses instead of linking with relative marker ke. For instance, the speaker uses two separate clauses to express an English relative clause i.e., I saw a man who was a teacher. He/she says: I saw a man. He was a teacher. It has only been attested eight passages with subjects which have been relativised in my large corporaFootnote 121 as in the following passage:

Ex. 44) Relative clause (CoB)

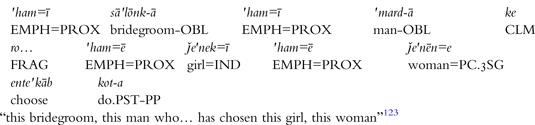

KoB has a stronger tendency to relativise subjects, objects and adjuncts. However, in some oral narratives still one can find traces of combining two sentences to relativised a subject or object. The following passage is an example of the relativised subject.

Ex. 45) Relative clause (KoB)

SiB has a very strong tendency for using relative clauses and show high frequency of usage of relative clauses across the dialects. The following passage presents a relativised object in SiB.

Ex. 46) Relative clause (SiB)

3. Some thoughts and reflections

When I studied the state of orality in these three dialects, I discovered that they demonstrated three different types of orality. As with the alignment system.Footnote 125

CoB was the most conservative one in the present study and presented traditional orality in all social contexts. The storytellers use short sentences, with hardly any lexical conjunctions, and almost no trace of subordination. In contrast, they employ a lot of unmarked repetition and tail-head linkage as enhancing coherence and as development device in their narrations. In addition, they use juxtaposition, instead of associative conjunctions and adversatives, to express logical relations in the discourse.

KoB preserved orality in prose, however, storytellers prefer Qašqā’i for narration. In comparison with CoB, the KoB storytellers tend to produce complex sentences with the help of subordination. Unmarked repetition and tail-head linkage are still used for coherence and as a development device in the narrations. However, there is a strong tendency among younger storytellers to use less repetition and tail-head linkage. Similar to CoB, the strategy of juxtaposition is very strong in narrations.

In SiB, the storytelling tradition has almost disappeared, except when using oral style for reciting songs, which was still common among the older generation when I did my field work. The structure of the sentences has become more and more complex with a high usage of subordination and conjunctions. There is a strong tendency to borrow conjunctions from Persian to express logical relations in the oral narratives. In contrast to CoB and KoB, there is almost no trace of repetition or of tail-head linkage as a development device. In contrast to CoB and KoB, the lexical development devices have been fully systematised. The juxtaposition strategy is not as strong as in CoB and KoB. Juxtaposition has already started to be replaced by the conjunction =o and by new conjunction borrowings from Persian. Thus, the narration style has switched from an oral style to a more written style by losing of oral techniques.Footnote 126

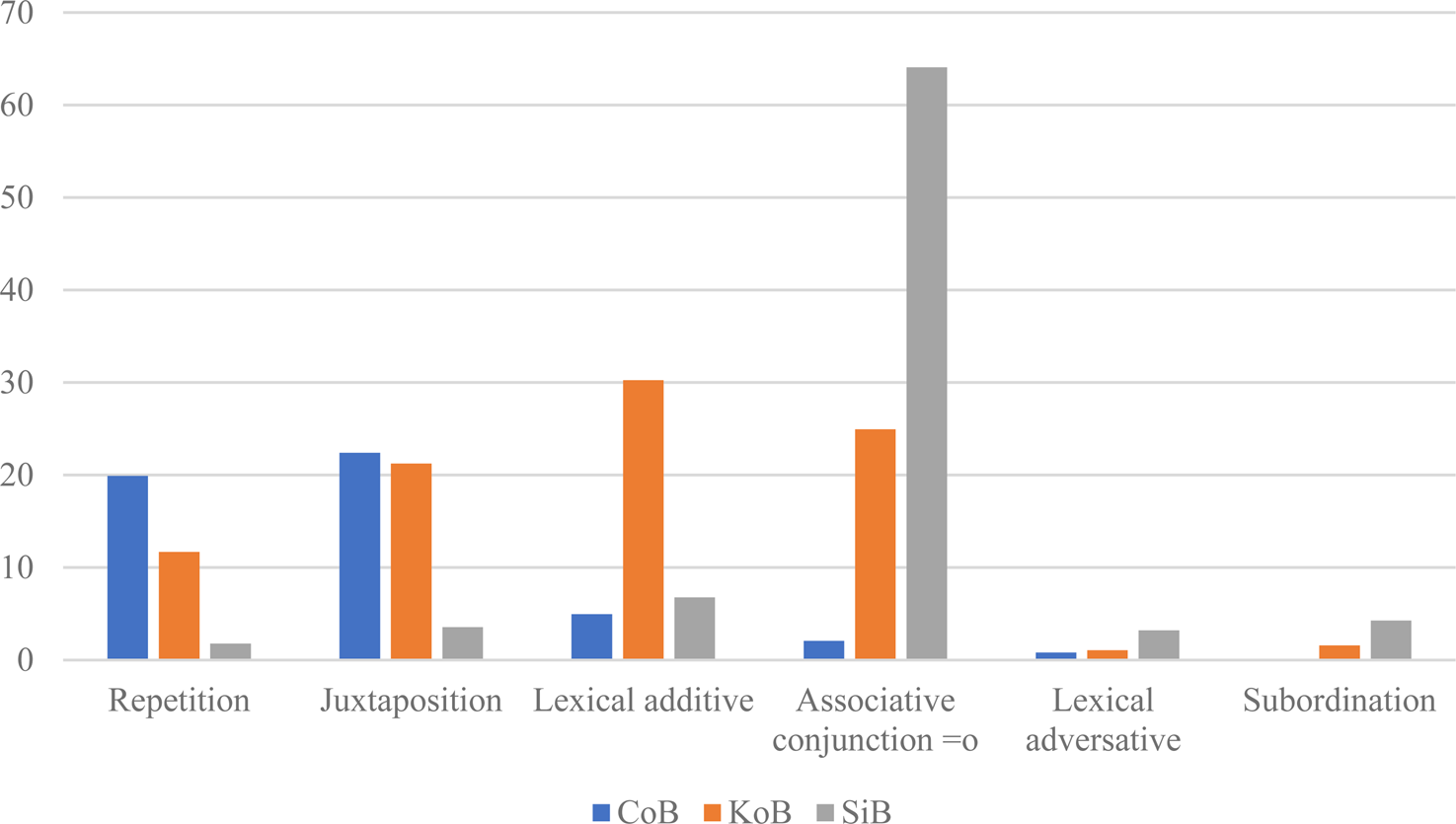

The following table demonstrates the frequency of the oral features discussed above across the dialects. The figures have been obtained from three long stories published in.Footnote 127 Each text represents the longest fairy tale for the respective dialect in my corpus. The total amount of the words per text is 2411 for CoB, 1884 for KoB and 2810 for SiB, normalised to a value of frequency per 1000 words to enable comparison across texts of different length.Footnote 128

Figure 1. Overall frequency of the features above mentioned across the dialects per 1000 words

As can be seen from the above table, CoB shows high frequency of using repetitions and less frequency of using additives, associative conjunction=o, lexical adversatives and no subordination. SiB, on the other hand, presents less usage of repetitions but a high usage of subordination, adversative and associative conjunction=o across the dialects. This observation leads us to conclude that SiB storytellers simply changed their style of narration due to stronger influence of the written language which was presumably considered more prestigious or higher school rate, using more writing techniques.Footnote 129 In contrast, the CoB storytellers use more archaic orality techniques in their narrations. KoB takes an intermediate position. It has a close similarity with CoB regarding the usage of juxtaposition, and lexical adversatives. But, it has the highest usage of lexical additives across the dialects.Footnote 131

Map 1: Map of the areas where data was gathered taken fromFootnote 130

These three dialects represent three different stages on a cline that is determined by the degree to which the relation between sentences is made explicit. Sentence connections in CoB are mostly implicit (simple juxtaposition). For this type, repetition of co-referent elements is the most common means to express a closer relation between sentences. The additive marker could be a sign of the intermediate stage as it makes the consecutive order explicit. This means that the additive marker ham/am/ hã = was used to spell out the relation that was otherwise implied by juxtaposition. Adversatives, associative, and subordinative conjunctions are another means to refine the different logical relations by different explicit expressions in the discourse.

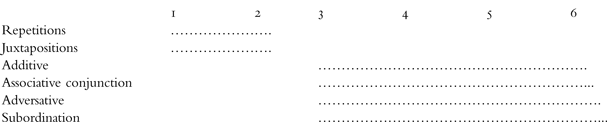

This cline of the degree of explicitness might not only be a synchronic typological cline, but a diachronic one as well. We have seen that repetition and juxtaposition are very common in CoB (where oral narration prevails, while the use of subordinating conjunctions by using complementizers is more elaborate in SiB where the tradition of oral storytelling is nearly lost). This suggests that the types identified above are linked to oral and written language. It is plausible that oral language represents the original style with written language being a later elaboration. If we assume a Proto-Balochi which all these three dialects derived from, it is likely that it exhibited prototypical features of oral style, i.e. repetition and juxtaposition. Additive, associative conjunction, adversative and subordination features would then be later developments, with additive markers probably being the first to emerge. This gives the following stages:

Stages 1–2 exhibit prototypical oral features and stages 3–6 prototypical written features. CoB is located at stage 2, KoB at stage 3 and SiB at stage 6.

This cline of the degree of explicitness corresponds to another gradual development, viz. the fading of ergativity in Balochi. This gives rise to the question whether there is any correlation between the fading of orality and ergativity? I would suggest that at least in Balochi the fading of orality (oral style) had a strong connection with fading of ergativity.Footnote 132 In the dialect that has preserved ergativity (CoB), orality was a living art. In the dialects that have lost ergativity (KoB and SiB) the state of orality was not so prominent.

Since we do not have any documented material from the earlier stages of Balochi, it will be difficult to draw a pathway of fading orality features in Balochi. However, the present comparison between three dialects sheds light on the course of the change from pure orality style to more written style by losing oral techniques.

In addition, one could think that education plays an important role in fading of the orality features across the dialects. However, the background of my storytellers from the CoB, KoB and SiB dialects belies this, as most of them were without a school education except for three storytellers who had a primary school education (primary school). The oral narrative texts from SiB demonstrate a high loss of orality features even though the storytellers were without a school education as well.Footnote 133 Thus, I would suggest that fading of orality features in Balochi dialects is a language-internal development.

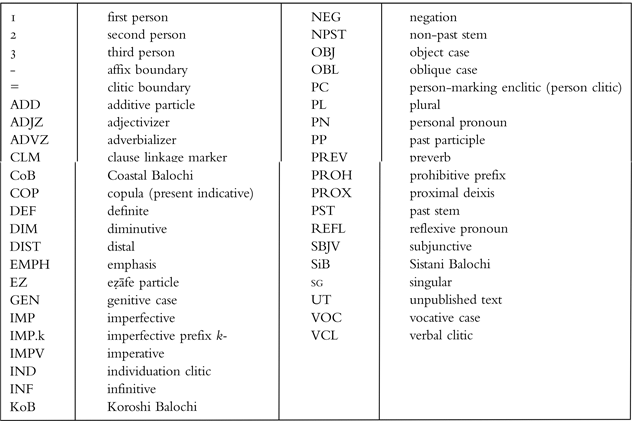

Abbreviations and glosses