The Khwarizmian language, belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European family and spoken in the fertile delta of the Amu Darya river south of the Aral Sea, was long known to have existed only through the reports of the famed polymath Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (d. 1050). In one of his most important extant works, al-Aṯār al-bāqiya ‘an al-qurūn al-khāliya (Chronology), he discusses various calendrical terms, giving the names of the months, days, and lunar stations in Khwarizmian as he does for Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Syriac, and Sogdian.Footnote 1 In the same work, al-Bīrūnī also laments the Arab conquest of Khwarizm which led to the destruction of older institutions, especially to a loss of the knowledge of writing in the indigenous Khwarizmian script.Footnote 2 As a Khwarizmian by birth, al-Bīrūnī was of course personally familiar with its history and customs.Footnote 3 On the basis of a passage in another of his works, the Kitāb al-ṣaydana fī l-ṭibb (Pharmacology), it has been assumed that his native language was indeed Khwarizmian.Footnote 4 In that work, al-Bīrūnī justifies his praise of Arabic as the scientific language par excellence by explaining that not only is Persian, which he also knows, unsuitable, but that moreover he has a mother tongue even less suitable for science, though he does not name it explicitly:

والى لسان العرب نُقلت العلوم من أقطار العالم فازدانت وحلت في الافئدة وسرت محاسن اللغة منها في الشرايين والاوردة وان كانت كل امة تستحلي لغتها التي الفتها واعتادتها واستعملتها في مآربها مع الّافها وأشكالها . وأقيسُ هذا بنفسي وهي مطبوعة على لغة لو خُلِد بها علم لاستُغرب استغراب البعير على الميزاب والزرافة في العِراب . ثم منتقلة الى العربية والفارسية فأنا في كل واحدة دخيل ولها متكلف والهجو بالعربية أحبُّ اليّ من المدح بالفارسية وسيعرف مصداق قولي مَن تأمل كتاب علم قد نقل الى الفارسي كيف ذهب رونقه وكسف باله واسودّ وجهه وزال الانتفاع به اذ لا تصلح هذه اللغة الا للأخبار الكِسروية والأسمار الليلية .

“From diverse corners of the world the sciences were transferred into Arabic, were embellished, inhabited in hearts, and the niceties of the language flowed through their arteries and veins, even though each nation prefers their language, which it is familiar with and used to and uses in fulfilling its needs with its peers and familiars. I measure this against my own self, for I was brought up in a language which, were science ever to be immortalized in it, it would be as astounding as a mule in a water-spout or a giraffe among thoroughbreds. Then I went over to Arabic and Persian, and am a stranger in each language and struggle in each one. But I would prefer insults in Arabic to praise in Persian! He who has ever engaged with a book of science translated into Persian will know the truth of my words—how its elegance disappeared, its sense darkened, its visage blackened, and its usefulness was voided. For this language (Persian) is only fit for reciting the legends of kings or bedtime stories”.Footnote 5

Reports such as al-Bīrūnī's were already an indication that the Khwarizmian language continued to be spoken at least up until the turn of the first millennium—later in fact, than the other known Iranian languages of Central Asia, Sogdian and Bactrian, are attested in their respective homelands.

The Khwarizmian Sources

However, nothing else was really known of Khwarizmian until a series of spectacular discoveries made by the Beshkiri scholar Zeki Velidi Togan (1890–1970) between the 1920s and 1940s, which revealed two groups of Khwarizmian source material written in a modified Arabic script and recorded in Arabic texts.Footnote 6

One is comprised of Islamic legal texts in Arabic containing Khwarizmian sentences. Chronologically, the first of these is a compendium entitled Yatīmat al-dahr fī fatāwā ’ahl al-‘aṣr (The Matchless Pearl of the Age on the Fatwas of Contemporaries) composed by Muḥammad ‘Alā’ al-Dīn al-Tarjumānī al-Khuwārizmī (d. 1257), several manuscripts of which contain Khwarizmian sentences in Arabic script.Footnote 7 Next comes a similar type of text entitled Qunyat al-munya li-tatmīm al-ġunya (The Acquisition of that which is Desired for the Completion of the Sufficiency), compiled in the early 13th century by Najm al-Dīn al-Zāhidī al-Ghazmīnī (d. 1260).Footnote 8 The Qunya is itself a summary of a now-lost work entitled Munyat al-fuqahā’ by the teacher of al-Ghazmīnī, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Qubaznī (known as Qāḍī Badī‘), the Qunya itself repeating much of the material of the Yatīma probably via the Munya. Several manuscripts of the Qunya contain extensive text in Khwarizmian. Then, about a century later the Khwarizmian material of the Munya and the Qunya was gathered into an untitled compendium by yet another scholar of Khwarizmian origin, Jamāl al-Dīn al-‘Imādī (d. ca. 1354). This latter work, otherwise untitled, has been called the Risāla (Treatise).Footnote 9

The Yatīma / Qunya groups of texts give cases of Islamic law taken from real life in medieval Khwarizm, often including dialogue in Khwarizmian and a discussion of the extent to which utterances in Khwarizmian have the same value under Islamic law as utterances in Arabic. Composed around the 13th century ce, they show a language still in wide daily use, albeit with much borrowing from Arabic and Persian. Though undoubtedly under pressure from both, Khwarizmian appears in the texts as a still-vital language with, for example, established strategies for integrating both Arabic and Persian loans: consider the abstract noun ḥl'l’wk [ḥalālāwak] meaning something like “halal-ness”, derived from the Arabic word ḥalāl and the Khwarizmian nominal suffix -’wk [-āwak].Footnote 10

In the 13th century, Khwarizm had long been under the rule of a succession of Turkic rulers and would be subjugated by the Mongols. Khwarizmian society was no doubt multilingual, with Arabic, Persian, and even Khwarizmian Turkic playing roles. The following extract from the Qunya illustrates how this text functions, how questions of language and law were considered, and the multilingual context of Khwarizm at that time. The passage first gives text in Khwarizmian (in Arabic script) and then proceeds to give an Arabic translation, as follows:

كاس اي مرڅ اي خوارزم وساڅ في غَشّياك في زڤاك في تركانك اَر اُغْلُمْ اوداس هيڅ كدامكام واڅ [Khwarizmian] نكُور ني ڤاڅ پا غشّياكاويَ اڅ ايّڅكام څي نان لفظ عِتق وا كذَاك كذاكِ

اي إن قال خوارزميٌّ في أثناء التلطّف على عبده بالتركية ار اُغْلُمْ و لم ينوِ شيءً في تلطّفه أيُستفادُ من لفظه هذا [Arabic] العتق؟ لا .

If a Khwarizmian man says “my brave lad” [är oġlum] in Turkish to his slave in the course of pleasantry, and if through the pleasantry he has no intention [to manumit him] whatsoever, will manumission proceed from that word or not? No.Footnote 11

The Arabo-Khwarizmian script has typically been transliterated rather than transcribed in publications by Iranists, and appears as follows in MacKenzie's edition of the text (short vowels are not written other than when indicated by the taškīl, which is represented in superscript):

kʾs ʾy mrc ʾy xwʾrzm wsʾc fy γašyʾk fy zβʾk fy trkʾnk ʾar ʾuγolumo ʾwdʾs hyc kdʾmkʾm wʾc nkuwr ny βʾc pʾ γšyʾkʾwya ʾʾci ʾyckʾm cy nʾn lfẓ ʿitq wʾ kδaʾk. kδʾki.

The second group of Khwarizmian source material is found in certain manuscripts of the Muqaddimat al-adab, the famed Arabic dictionary of al-Zamakhsharī (d. 1144), himself also a native of Khwarizm, which have interlinear glosses in Khwarizmian. Though it was long thought that the main manuscript was his autograph, it is more probable that it dates from around 1200, nevertheless not long after the author's death.Footnote 12 This material provides the majority of the known Khwarizmian lexicon with over 4,000 glosses, often individual words or brief phrases rather than sentences.

Taken together, all these sources shed light on Khwarizmian as it was written in the 12th and 13th centuries in the Arabic script. And indeed, the manuscripts’ relative consistency in spelling and use of new letter-forms leads one to assume that they in fact are written in a roughly ‘standard’ Arabo-Khwarizmian script, even if later copyists did not always adhere to it or understand the Khwarizmian. And if, as al-Bīrūnī mentions, the Arab conquest ultimately led to the loss of knowledge of the indigenous script, it would be unsurprising if an Arabo-Khwarizmian one had developed soon after. Just as the Arabic script was extended to represent certain sounds required for Persian, such as چ for [č] and پ for [p], at some point it was also extended to represent Khwarizmian, in particular by the innovation of a new letter: څ, a ḥā’ with three dots on top.Footnote 13 This څ of the texts has been transliterated with a c by Iranists, as can be seen in the above extract from the Qunya. This goes back to Henning, who proposed transliterating c for څ on the basis of both modern Pashto where the letter څ represents [ts] and modern Ossetic in which Iranian *č and *-ti- become [ts], a sound change which Henning proposed also for Khwarizmian.Footnote 14 Later, Henning proposed that c encodes both this [ts] and a voiced allophone [dz]—also as in Pashto, where څ was used for [ts] and [dz] from the late 17th century until the 20th century when the separate sign ځ (a ḥā’ with hamza above) was developed for [dz].Footnote 15

Khwarizmian has a [č] چ besides this څ, a distinction made quite consistently in the Qunya/Risāla, though somewhat irregularly in the Muqaddima.Footnote 16 The conditions under which both sounds occur have not been sufficiently clarified, however.

Table 1. Extended Arabic letter-forms for Khwarizmian in the Risāla

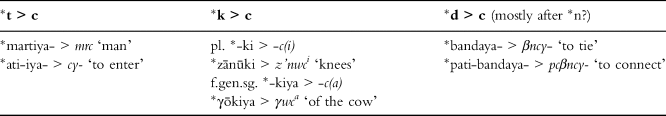

Since the Qunya is rather consistently pointed, it is possible to see that [č] چ occurs primarily in Persian loanwords (such as č’h ‘pit’ from Persian čāh) but also in inherited Khwarizmian words as a secondary change from earlier consonant clusters (such as ’čn ‘to be thirsty’ < *tršn-). There are a handful of words written with č where the č may go back to Old Iranian *č (such as črm ‘skin’ < *čarman-, but this could also be a Persian loan), but the majority of words with older *č are written with the څ (such as cm ‘eye’ < *čašman- or cf'r ‘four’ < čaθwāra-); the conditions under which *č is preserved as [č] have yet to be fully established. Several other sound changes in Khwarizmian have evidently led to c being a frequently occurring letter: these include the palatalisation of *t,Footnote 17 the palatalisation of *k, and also seemingly the palatalisation of *d, in the environment of high vowels or the palatal glide [y].

Table 2. Examples of palatalisation to c in Khwarizmian drawn from the Qunya and Muqaddima

As mentioned, it was words such as βncy which led Henning to suggest that څ not only encoded a voiceless affricate [ts] but also a voiced counterpart [dz] deriving from earlier *d; many if not most of these cases involve the sequence *-nd-, one of the few places where *d did not change into a fricative [ð] as it does elsewhere. We shall return to this discussion. In any case, this څ seems to have been invented specifically for the needs of Khwarizmian and these manuscripts represent the earliest attestation of the letter څ, at least three centuries before it is used for Pashto for the first time. Yet when it was first used for Khwarizmian cannot be said with any certainty. Manuscripts of al-Bīrūnī's works in which he cites Khwarizmian terms do not employ the څ, perhaps because they were copied by later, non-Khwarizmian-speaking scribes who did not know of the letter—in the Edinburgh manuscript (copied 1307) of the Chronology, the ultimate source of Sachau's manuscripts, words with c are written with either ج or چ , and in the Beyazıt manuscript, the oldest (12th c.) and best manuscript of the Chronology, such words are written with either no points (ح ) or just one (ج )Footnote 18—or because it had not been invented yet for the language. The earliest Khwarizmian source in Arabic script, the Konya manuscript of the Muqaddimat al-adab, does not appear until perhaps the end of the 12th century. But as with most ancient languages which are known today only in written form, it is difficult to know exactly how certain sounds were pronounced, and this څ is no exception. Fortunately, though, there exists a contemporary source potentially able to shed some light on the matter.

Ibn Sīnā's Remarks on Khwarizmian

Written between his arrival at the Iṣfahān court of ‘Alā’ al-Dawla in 1024 and his death in 1037, Ibn Sīnā's treatise Asbāb Ḥudūt̰ al-Ḥurūf (The Causes of the Genesis of the Consonants) gives a rigorous treatment of Arabic phonetics, detailing the various sounds in the Arabic language and the parts of the mouth involved in producing them.Footnote 19 While the treatise draws on ancient traditions, especially Galen, it also contains unique and novel arguments about the physical production of sound, no doubt based on Ibn Sīnā's medical expertise. Several features of the work, from the order in which the letters are discussed to the linguistic terminology to several of the concepts (such as qal‘ “sudden separation” and ruṭūba “moisture”), set it apart from the classical Arabic linguistic traditions.Footnote 20

In addition, the treatise has a chapter entitled fī l-ḥurūf al-šabīha bi-hādhihī l-ḥurūf wa-laysat fī lughat al-‘arab “Regarding consonants similar to these [Arabic] consonants but not in the language of the Arabs”,Footnote 21 in which are discussed both Arabic consonants which are produced incorrectly by non-Arabs, as well as sounds that were not part of Arabic but occurred in other languages with which he was familiar. His method involves comparing these sounds to the Arabic consonants he describes earlier in the treatise. For example, Ibn Sīnā notes that other languages have “ǧīm-like” consonants, “among them [being] the consonant which is pronounced at the beginning of the noun ‘well’ in Persian, which is čāh” (minhā l-ḥarfu lladhī yunṭaqu bihi fī awwali smi l-bi'r bi-l-fārisiyyati wa-huwa čāh).Footnote 22 Because of properties such as its place of articulation, Persian [č], Ibn Sīnā notes, and correctly from a modern linguistic perspective, that it is similar to the Arabic [ǧ]. He then states that there are other sounds which are not in Arabic or Persian but in other languages, such as a “ṣād-like” (šibh al-ṣād) consonant and a “sīn-like” (šibh al-sīn) consonant, for which he neither specifies the language in which they occur nor gives any examples. He then goes on to describe a “zāy-like sīn that is frequent in the language of the people of Khwarizm” (sīnun zā’iyyatun takṯaru fī lughati ’ahli khuwārizm).Footnote 23

Before coming to a discussion of this sound, it is worth asking whether Ibn Sīnā was referring to that which we now know of as the Khwarizmian language, as opposed to a distinctive local variety of (New) Persian, since he says the “language of the people of Khwarizm” (lughat ’ahl khuwārizm) while the somewhat later sources discussed in the first part of this paper use “Khwarizmian” (khuwārizmī); these latter sources were, of course, written by actual speakers who no doubt knew what to call their own language, even in Arabic. Scholars of the generation just prior to Ibn Sīnā were aware of, or had encountered, a distinct language in the region, though for the most part they did not give it a specific name: the geographer al-Maqdisī (d. 991) simply mentions that the “language of the people of Khwarizm cannot be understood” (lisān ’ahl khuwārizm lā yufhim)Footnote 24 while the noted traveller Ibn Faḍlān (d. 960) was somewhat more judgmental, writing in his travelogue that “the Khwarizmians are the most barbarous of people, both in speech and in custom. Their speech sounds like the cries of starlings (kalāmuhum ’ašbaha šay'in bi-ṣiyāḥi z-zarāzīr). There is a village…whose inhabitants are known as Kardaliya, and their speech sounds like the croaking of frogs (kalāmuhum ’ašbahu šay'in bi-naqīqi ḍ-ḍafādi‘)”.Footnote 25 Ibn Ḥawqal (d. ca. 978), who was in Khwarizm in 969, was more objective, stating that “[the Khwarizmians’] language is unique to them, no other like it is spoken in Khurāsān (wa-lisān ’ahlihā mufrad bi-luġatihim wa-laysa bi-khurāsān lisān ‘alā luġatihim)”.Footnote 26 So well before even al-Bīrūnī wrote about it, scholars of the time seem to have been aware of a particular and seemingly unique language in the region, and this general knowledge is likely to have been available to Ibn Sīnā.

More importantly, however, Ibn Sīnā spent about a decade, until 1012, living and working in Khwarizm at the court of the Khwarizm-Shāhs at Gurgānj, where he undoubtedly heard Khwarizmian being spoken and actually overlapped with al-Bīrūnī, with whom he also corresponded later in life.Footnote 27 In fact, like his polymath colleague, Ibn Sīnā may also even have been a speaker of a non-Persian Iranian language before learning and mastering both Persian and Arabic.Footnote 28 Given all this, it seems certain that Ibn Sīnā is indeed referring to the Khwarizmian language known to us.

Now, the entire passage to be discussed is as follows:

ومن ذلك سين زائية تكثر في لغة اهل خوارزم وتحدث بأن تهيّأ الهيئة التي عن مثلها تحدث السين ثم يحدث في العضلة الباطحة للّسان ارتعاد كما يحدث في الزاي يلزم ذلك الارتعاد مماسّات خفية غير محسوسة يحتبس لها الهواء احتباساتٍ غير محسوسةٍ فتضرب السين لذلك الى مشابهة الزاي .

Among these [sounds not occuring in Arabic] is a sīn zā’iyya that is frequent in the language of the people of Khwarizm. It occurs by preparing the construction from the like of which the sīn occurs, then in the flattening muscle of the tongue an irti‘ād occurs, as occurs with zāy. That irti‘ād is accompanied by hidden, imperceptible contacts, by which the air is trapped by imperceptible obstructions (iḥtisābāt). Thereupon the sīn occurs like the zāy.Footnote 29

How the sīn and zāy are to be combined is at first glance difficult to envisage. Not so for the next sound described in the chapter, however, which is a šīn-like zāy (zāy šīniyya) of the kind, Ibn Sīnā says, heard in Persian when they say žarf ‘deep’ (zāyun šīniyyatun tusma‘u fī l-lughati l-fārisiyyati ‘inda qawlihim žarf).Footnote 30 The point is quite clear: the zāy pronounced at the place of articulation of the šīn gives us [ž].Footnote 31 In modern linguistic terms, adding the voicing of the fricative [z] to the palato-alveolar articulation of the fricative [š] yields the voiced palato-alveolar fricative [ž]. Its writing with ژ in the Arabo-Persian script, it is worth noting, likewise points to its association with Arabic ز rather than with ج . But if a [š]-like [z] is the sound [ž], then [z]-like [s] is not a new sound but simply remains [z]. That is, adding of the voicing of [z] to [s] just gives [z]. We might try to match the sound described in the Causes with what we already think we know of Khwarizmian from the sources previously mentioned. There are several zāy-like and sīn-like sounds which are potential candidates for what Ibn Sīnā describes: besides [s] and [z] themselves, there are also [š] and [ž], as well as [č] and the sound written by means of څ. We can firstly eliminate [s], [z], and [š] from the list, as they, also occurring in Arabic, would not have merited any special comment by Ibn Sīnā. We can also eliminate [č] since he describes that separately from the sīn zā’iyya, as mentioned. What then could the sound be? Since Ibn Sīnā unfortunately cites no example from the Khwarizmian language, we must interpret his description of the consonants to determine what sound he understands this sīn zā’iyya to be. First is that the sīn zā’iyya is based on the construction of the sīn, the description of which is rather concise:

وأمّا السين فتحدث مثل حدوث الصاد إلا أن الجزء الحابس من اللسان فيه أقلّ طولاً وعرضاً وكأنها تحبس العضلات التي في طرف اللسان لا بكليتها بل بأطرافها

As for the sīn, it occurs like the occurrence of the ṣād except that the obstruction (ḥabs) of the tongue in it is less in length and in width. It is as though the muscles that are at the edge of the tongue obstruct (taḥbis) not with their entirety but with their edges.Footnote 32

The sīn is thus related to the ṣād in terms of its “obstruction” (ḥabs), but is said to be less (aqall) and to not involve the entirety of the tongue. If we turn to the ṣād, we find that it is likewise described in relation to the sīn, where it is said to have a “narrower” (aḍyaq) and “drier” (aybas) obstruction than the sīn but that it covers (yuṭbiq) two-thirds of the surface of the palate. If Ibn Sīnā's description of the sīn is brief, though, then his description of the zāy is much more long and complicated, but worth citing in full:

وأمّا الزاي فإنها تحدث من الأسباب المصفرة التي ذكرناها إلا أنّ الجزء الحابس فيها من اللسان يكون ممّا يلي وسطه ويكون طرف اللسان غير ساكن سكونه الذي كان في السين بل يمكن من الاهتزاز فإذا انفلت الهواء الصافر عن المحبس اهتزّ له طرف اللسان واهتزّت رطوبات تكون عليه وعنده ونقص من الصفير . إلا أنّه باهتزازه يحدث في الهواء الصافر المنفلت شبه التدحرج في منافذه الضيّقة بين خلل الأسنان فيكاد أن يكون فيه شبه التكرير الذي يعرض للراء وسسب ذلك التكرير اهتزاز جزءٍ من سطح طرف اللسان خفي الاهتزاز .

As for the zāy, it occurs from the whistling causes that we mentioned except that the ḥabs of the tongue emerges near its middle and the edge of the tongue is not holding the stationary position that occurs in the [articulation of the] sīn, but is, rather, capable of ihtizāz. If the whistling air escapes the place of obstruction (maḥbas), the edge of the tongue vibrates (ahtazza) to it; the moistures that it has and that are on it vibrate (ahtazzat) and it has a diminishment of the whistling, except that in its ihtizāz it causes in the whistling and coursing air a quasi-tumble in its narrow passages between the gaps of the teeth. There is in it almost the quasi-repetition that happens to the rā’ and the cause for that repetition is the ihtizāz of a part of the surface of the edge of the tongue with a hidden ihtizāz.Footnote 33

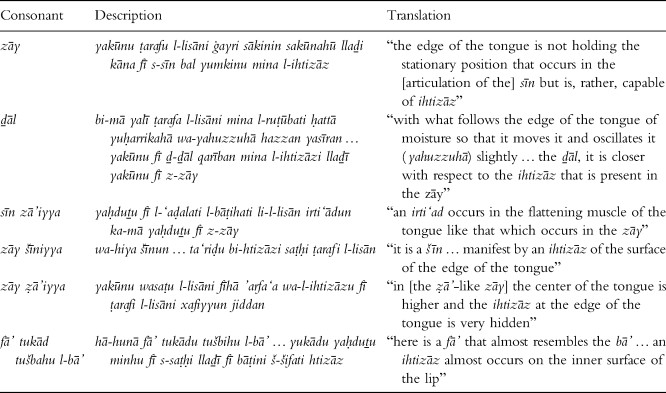

The first way in which the sīn zā’iyya is then zāy-like is that, according to its description, “in the flattening muscle of the tongue an irti‘ād occurs, as occurs with zāy” (yaḥduṯu fī l-‘aḍalati l-bāṭiḥati li-l-lisāni kamā yaḥduṯu fī l-zāy). The description of the zāy, however, mentions no irti‘ād, which I have left untranslated for the moment. Instead, the zāy is described as differing from sīn with regards to ihtizāz: “the edge of the tongue is not holding the stationary position that occurs in the [articulation of the] sīn but is, rather, capable of ihtizāz” (yakūnu ṭarafu l-lisāni ġayri sākinin sukūnahū lladhī kāna fī l-sīni bal yumkinu mina l-ihtizāz). The related consonant zāy šīniyya [ž] is also described as “manifested by the ihtizāz of the surface of the tip of the edge of the tongue” (tu‘riḍu bi-htizāzi saṭḥi ṭarafi l-lisān). So, to the zāy itself and the šīn-like zāy, Ibn Sīnā ascribes the characteristic of ihtizāz, which he only uses for the small group of consonants presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Consonants to which Ibn Sīnā ascribes ihtizāz or irti‘ād

As can be seen, this ihtizāz or irti‘ād is employed only for the Arabic consonants zāy [z] and ḏāl [ð], and for several non-Arabic consonants such as the “fā’ which almost resembles the bā’” (by which is meant the Persian [v] or [β]), the šīn-like zāy (Persian [ž]), the zāy-like sīn of Khwarizmian, and a ẓā’-like zāy in an unspecified non-Arabic language. Ibn Sīnā only otherwise uses the term in the description of the ġayn, where he says the airflow causes something similar to ihtizāz (but not ihtizāz itself). Since the description mostly uses ihtizāz, and only once irti‘ād (which is linked to the zāy where ihtizāz is used), it is possible that both terms are meant to refer to the same phenomenon. In particular, this seems to be a characteristic of what we would now call voiced fricatives. Though in 2009 Sara translated ihtizāz as “oscillation” but irti‘ād as “trembling”, implying a difference in the two, I think that on the basis of their usage and the similarities in the consonants grouped above, it is reasonable to assume that Ibn Sīnā intended them to describe the same phenomenon.Footnote 34 As a property common to voiced fricatives, both terms may best be translated with “vibration”. Yet in general the Causes does not make use of a category comparable to our modern category of “voice”. Instead, by using “vibration”, the treatise tends to point to where vibration, as an effect of voiced consonants, can be felt in the mouth: for [z] and [ð] it is on the “edge of the tongue” (ṭarafi l-lisān) while for the sīn zā’iyya it is in the “flattening muscle of the tongue” (al-‘aḍalati al-bāṭiḥati li-l-lisān), for the [ž] it is on the “surface of the edge of the tongue” (saṭḥi ṭarafi l-lisān), and for the [v] or [β] it almost occurs on the “inner (surface) of the lip” (bāṭini š-šifati).

The second characteristic of the sīn zā’iyya is that the airflow is trapped by “imperceptible obstructions” (iḥtisābāt ġayr maḥsūsa). The feature of “obstruction” (ḥabs) occurs frequently in the work and appears to be a fundamental feature of Ibn Sīnā's phonetic description. Ḥabs is used to describe how and where oral elements touch each other to change the airflow and produce different sounds: this could be the tongue touching the palate (as in the ṣād), but could also be both lips touching each other (as in the bā’). Many consonants have a “complete obstruction” (ḥabs tāmm), some have an “incomplete obstruction” (ḥabs ġayr tāmm), and others, interestingly enough, are described as having no ḥabs, in particular the šīn, which is said to be like the jīm but with no obstruction at all.Footnote 35 Since the ḥabs is what is involved in obstructing the oral cavity, it does not just have quantity (“complete” or “incomplete”) but also quality: as we have seen it may be “less” (aqall) as in the sīn or “drier” (aybas) as in the ṣād.Footnote 36

Do these descriptions help us to understand the articulation of the sīn zā’iyya? First, it is related to the sīn (and thereby also to the ṣād) in the quality and quantity of its ḥabs. This suggests that among obstruents, it belongs towards the fricative (including [s] but excluding [š]) to affricate side of the consonant group (the only affricate in Ibn Sīnā's system seems to be [ǰ]). Secondly, it has “vibration” like the zāy and other voiced fricatives. Ibn Sīnā's system thus suggests that the sīn zā’iyya is a voiced alveolar sibilant fricative or affricate.

As mentioned previously, Iranistic scholarship has postulated the sounds [ts] and [dz] for Khwarizmian, both encoded by the Arabic letter څ. If our analysis of Ibn Sīnā's description of the sīn zā’iyya is correct, then the best match for it seems to be [dz] rather than [ts]. From the perspective of our understanding of the Khwarizmian sources, this is somewhat unexpected, as [ts] seems to be the more common sound, at least on the basis of etymology. One possibility is that what has been thought thus far to be a [ts] was actually a voiced [dz], and this [dz] was therefore one of the most prominent “foreign” sounds to an Arabic or Persian ear. It seems odd that Ibn Sīnā, with his firsthand knowledge of Khwarizmian and ability to describe both differing pronunciations of Arabic sounds such as qāf Footnote 37 and non-Arabic sounds such as the [p], [v], [č], and [ž] of Persian, would not have been able to notice both a [ts] and a [dz], if both existed. But his treatise on phonetics does not cover all the possible sounds he could have heard in the various languages spoken in the places he lived; perhaps a [dz] was more unusual to him than other sounds and therefore merited description.Footnote 38

At the same time, Ibn Sīnā does not claim to exhaustively describe all non-Arabic sounds he had ever heard, and does not consistently give examples for those which he does describe. It thus seems that the section on non-Arabic sounds in the Causes most likely served to give further examples illustrating the applicability of his phonetic approach to speech sounds in general. Ibn Sīnā's remarks do not, unfortunately, bring a definitive solution to our study of this aspect of Khwarizmian phonology. It is nevertheless my contention that he was describing a real sound present in the Khwarizmian language of his day, and quite possibly the sound, or one of the sounds, encoded by the Arabic letter څ, developed specially for writing Khwarizmian. What scholars reconstruct of the phonology of a medieval language preserved only in written texts is, of course, tentative. It is thus instructive to consider examples, rare as they may be, of linguistic analysis of such languages dating from a time in which they were still spoken. That the two may not neatly agree is an invitation both to revisit our understanding of those texts and to continue to cast our nets wider in search of contemporary sources.