No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2011

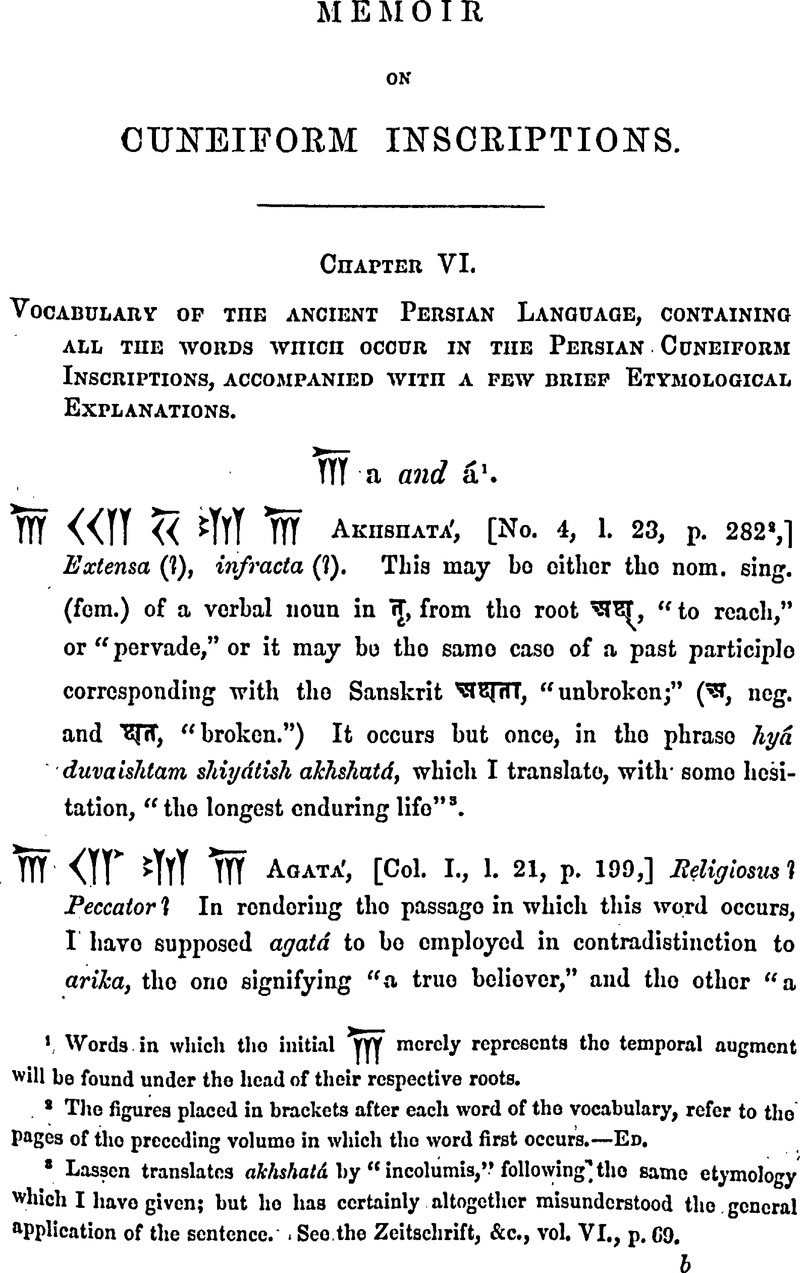

1note page 1 Words in which the initial ![]() merely represents the temporal augment will be found under the head of their respective roots.

merely represents the temporal augment will be found under the head of their respective roots.

2note page 1 The figures placed in brackets after each word of the vocabulary, refer to the pages of the proceding volume in which the word first occurs.—Ed.

3note page 1 Lassen translates akhshatá by “incolumis,” following”, the same etymology which I havo given; but he has certainly altogether misunderstood the.general application of the sentence. . See the Zeitschrift, &c, vol. VI., p. C9.

1note page 2 In this view the figure of speech employed will be the increment rather than the antithesis, for the application of the two phrases which occur in juxtaposition will be almost coincident.

2note page 2 Compare ‘upastám abara, “he brought help,” bájim abaratá, “they brought tribute;” also baratiya in the present, and baratuwa in the imperative.

3note page 2 If the signification were “I oppressed,” I should certainly expect to find the orthegraphy of abár(a)yam, and I leave the interpretation therefore of the phrase above quoted, as one of the points which I consider to be still doubtful.

1note page 3 Lassen, relying on a Zend etymology, translates dushiyára by “scarcity,” (lit. “bad year;”) I shall consider hereafter the propriety of this reading. See Lassen's Mem. abevo quoted.

2note page 3 The words aniya and ájamiyá afford a good oxamplo of the serious inconvenience which arises from the impossibility of distinguishing the quantity of the initial ![]() In ájamiyá, the vowel must, I think, be elongated; but the context can alono shew whether

In ájamiyá, the vowel must, I think, be elongated; but the context can alono shew whether ![]() , may represent the Sanskrit

, may represent the Sanskrit ![]() , or whether it may be derived from

, or whether it may be derived from ![]() .

.

3note page 3 See paragraphs 11 and 17 of the 4th column, at Behistun. The interdictory má requires to be joined to the aorist or imperfect without the augment, forms in which a servile long á can very rarely occur.

1note page 4 In the Supplement to Lassen's Memoir, which has reached mo since the above was written, I perceive that he rejects Westergaard's emendation of aniya for abiya, and that the latter gentleman acquiesces in this restoration of the old reading. See the Zeitschrift, p. 470. We must therefore, I think, translate the sentence in question, “ad hane provinciam ne (sint), &c., &c.”

2note page 4 Lassen translates ájamiy´ by “hiemis tempestas,” supposing the Cuneiform term to be allied to the Sanscrit hima, Zend zydo, (acc. zyäm,) Latin hiems, &c. See the Zeitschrift, p. 33; but I must observe on the one hand, that the initial ![]() which cannot be an unmeaning prosthesis, presents an insuperable etymological difficulty; while on the other, however applicable to the feelings and condition of the primitive Arian emigrants from Imaus may have been the dread of the herrors of winter depicted in the second Fargard of the Vendidád, it seems preposterous to suppose that any such apprehension could have existed amongst the inhabitants of the sunny plains of Persia.

which cannot be an unmeaning prosthesis, presents an insuperable etymological difficulty; while on the other, however applicable to the feelings and condition of the primitive Arian emigrants from Imaus may have been the dread of the herrors of winter depicted in the second Fargard of the Vendidád, it seems preposterous to suppose that any such apprehension could have existed amongst the inhabitants of the sunny plains of Persia.

1note page 5 For a full examination of the Cuneiform roots ish and aish, see under the head ish.

2note page 5 My rough copy gives the reading of Atiyádasha, but as the letters were much defaced, I must I think have mistaken ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

1note page 6 It is doubtful whether the Zend r ![]() should not rather be pronounced tád than tát, the former agreeing bettor with

should not rather be pronounced tád than tát, the former agreeing bettor with ![]()

2note page 6 For the employment of this suffix iu Zend and Sanskrit see Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 163, with the extract which is there given from Panini.

3note page 6 See particularly the concluding portion of the 11th Fargard of the Vendidád, (Bombay edition, p. 378,) where ![]() the 2nd pers. Plur. phir. of the imperative, occurs no less than thirteen times with the meaning of “destroy.” Bumouf (Yaçna, p. 531,) derives the Zend parsta from par, (i. e. pěrě), comparing the term with pěrˇnê, which is found in the preceding paragraph of the same chapter of the Vendidad; but I do not think his explanation of the inflexion in sta to be at all satisfactory. If we suppose the root to be par(a)s which in the inscriptions certainly has the signification of “destroying,” the Zend

the 2nd pers. Plur. phir. of the imperative, occurs no less than thirteen times with the meaning of “destroy.” Bumouf (Yaçna, p. 531,) derives the Zend parsta from par, (i. e. pěrě), comparing the term with pěrˇnê, which is found in the preceding paragraph of the same chapter of the Vendidad; but I do not think his explanation of the inflexion in sta to be at all satisfactory. If we suppose the root to be par(a)s which in the inscriptions certainly has the signification of “destroying,” the Zend ![]() will be the regular 2nd pers. plur. of the imperative.

will be the regular 2nd pers. plur. of the imperative.

1note page 7 Professor Lassen continues up to the present timo to compare the Cuneiform thag with the Persian ![]() , (See Zeitschrift, pp. 75 and 472), but the latter word is a puro Arabic derivative, (

, (See Zeitschrift, pp. 75 and 472), but the latter word is a puro Arabic derivative, (![]() “an arch,” from

“an arch,” from ![]() , “to be equal,”) and could not havo been known in Persia prior to the Mohammedan conquest. I hardly see moreover how he obtains from this source the meaning of “substructio.”

, “to be equal,”) and could not havo been known in Persia prior to the Mohammedan conquest. I hardly see moreover how he obtains from this source the meaning of “substructio.”

2note page 7 See Wilkin's Grammar, Rules 10G and 769. The suffix in in is very commonly employed in Zend, and is preserved also in the modern Persian. Compare (![]() , “sweet;”

, “sweet;” ![]() , “golden,”

, “golden,” ![]() , “heavy;”

, “heavy;” ![]() , “coloured,” &c.

, “coloured,” &c.

3note page 7 See Wilkius, Rules 824 and 833.

1note page 8 Where the Median reproduces a Persian word, of course the termination in na may occur in the nom., but I doubt exceedingly if the Median asanna be a reproduction of the Persian áthagaina, for the initial letter is that which uniformly answers to ![]() and not to

and not to ![]() alone.

alone.

2note page 8 I must observe, hewever, that the termination in aina is otherwise entirely unknown in the inscriptions, and that as it is evidently a secondary and artificial form for the instrumental, it is highly improbable that it sheuld have co-existed with the primitive ending in long a, which occurs in every other Cuneiform example on record; aina, in fact, contains three distinct etymological irregularities; the a of the base is changed to ai (![]() ) a euphenic n is then added, and the true instrumental case-suffix

) a euphenic n is then added, and the true instrumental case-suffix ![]() is shertened to

is shertened to ![]() . See. Bepp's Comp. Gram., s. 158. At the same time, I cannot identify aina as the nom. of a suffix either of agency or attribution, and I am obliged therefore to remain content with its possible correspondence with the Sans.

. See. Bepp's Comp. Gram., s. 158. At the same time, I cannot identify aina as the nom. of a suffix either of agency or attribution, and I am obliged therefore to remain content with its possible correspondence with the Sans. ![]() . I must add, also, as a further correction of the translation given in the text, that even admitting athagaina to be an instrumental, Ardástdnas cannot possibly represent that case. Ardastána for Ardastánas may be gen. or an ablat., but neither am I satisfied that these cases are ever used for the instrum., nor do I think that a gen. or abl. noun could possibly be joined to an instrument, adjective. If, therefore, áthagaina be. really the instrumental of the noun áthaga, perhaps the best translation may be “made by the labour of Ardastá, for the family of King Darius.” For further remarks see the note to Ardastána

. I must add, also, as a further correction of the translation given in the text, that even admitting athagaina to be an instrumental, Ardástdnas cannot possibly represent that case. Ardastána for Ardastánas may be gen. or an ablat., but neither am I satisfied that these cases are ever used for the instrum., nor do I think that a gen. or abl. noun could possibly be joined to an instrument, adjective. If, therefore, áthagaina be. really the instrumental of the noun áthaga, perhaps the best translation may be “made by the labour of Ardastá, for the family of King Darius.” For further remarks see the note to Ardastána

1note page 9 It would be tedious and unprofitable to enumerate all the passages in which each, particular word occurs. The reference is usually to the first passago in which the word is found, following the order of the inscriptions as they are given in the preceding chapters.

2note page 9 See Strabe XVI., 8. 52; Arrianus Alexander, 1. III. , c. 7; and Stephen, in voco Νίνος, ,where however he merely quotes from Strabe. Suidas repeats the quotation under the sarao head.

1note page 10 Dio Cass. 1. LV., s. 20.

2note page 10 The name of Assyria I also believe to be extant in the Babylonian Inscription on the grave of Darius, but I cannot yet satisfy myself of its exact orthegraphy.

3note page 10 See Reimar's note to Dio Cass., torn. I I. , p. 1141, and Walton's Polyglot Bible, p. 39.

4note page 10 The Arabic Geographers always give the titlo of Athúr to the great ruined capital near the mouth of the Upper Zab. The ruins are now usually known by the name of Nimrud. It would seem highly probable that they represent the site of the Calah of Genesis, for the Samaritan Pentateuch names this city Lachisa, which is evidently the same title as the Λάρισσα of Xenophen, the Persian τ being very usually replaced beth in Median and Babylonian by a guttural. (Compare the Chabaessoarach of Bcrosus with the Lalorosoarchod of Josoplius.) If Nimrud be Calah, the name of καλαχηνη attaching to the province will be sufficiently explained, but Itesen, named by the Samaritans Aspa, will still have to be discovered.

5note page 10 Upon this connexion depend very important ethnographical considerations which I shall exposo in the sequel.

1note page 11 See Bepp's Comparative Grammar, (Eng. edit) s. 198 and 202, with the note top. 215. It appears, hewever, that Panini (VII. 1.39) considers the Vedic ![]() :, “to dexterâ,” to be a genitive used for a locative, and certainly this transposition is very frequent in Zend. I prefer at the same time adopting Bepp's explanation, that the termination in ám is a corruption of ás.

:, “to dexterâ,” to be a genitive used for a locative, and certainly this transposition is very frequent in Zend. I prefer at the same time adopting Bepp's explanation, that the termination in ám is a corruption of ás.

2note page 11 ![]() in Sanskrit, however, is of the sixth conjugation, and with the prefixing of the particle of negation it would signify “not to possess,” rather than “to dispossess.” These are strong arguments against its identity with the Cuneiform

in Sanskrit, however, is of the sixth conjugation, and with the prefixing of the particle of negation it would signify “not to possess,” rather than “to dispossess.” These are strong arguments against its identity with the Cuneiform ![]() , yet I find other possiblo correspondent

, yet I find other possiblo correspondent

1note page 12 That is, din in the first conjugation should make the 1st pers. sing, of the impcrf. in ádinam and the 3rd pers. in ádina (for ádinat), with the shert instead of the long a. Examples, moreover, of the abeve regular formation of the verbs of the first class are so common in the inscriptions, that the final ![]() in ádiná, may be held determinately to remove the root from that conjugation.

in ádiná, may be held determinately to remove the root from that conjugation.

2note page 12 I do not at present remember any form with this senso in the cognate languages which will admit of a possible comparison, but the Scottish tint, “lost.”

1note page 13 ![]() is supposed by the grammarians to be derived from

is supposed by the grammarians to be derived from ![]() , “to eat,” but no great dependence can be placed on the explanations of these fanciful etymologists.

, “to eat,” but no great dependence can be placed on the explanations of these fanciful etymologists.

2note page 13 It was the apparent interchangeability of the letters ![]() and

and ![]() in the orthegraphy of the terms pridiya and Atřiyátiya, that induced me, against all etymological evidenco, to class the former character among the surd dentals; but I We corrected this error in my Supplementary Note on the Alphabet, p. 179. In the 38th line of the Nahhsh-i-Rustam Inscription, I also think in the word yadi-Patiya, the doubtful character which I have restored as

in the orthegraphy of the terms pridiya and Atřiyátiya, that induced me, against all etymological evidenco, to class the former character among the surd dentals; but I We corrected this error in my Supplementary Note on the Alphabet, p. 179. In the 38th line of the Nahhsh-i-Rustam Inscription, I also think in the word yadi-Patiya, the doubtful character which I have restored as ![]() must be altered to

must be altered to ![]() See p. 301.

See p. 301.

1note page 14 If adakiya be a genuino word, it must be etymologically explained, I think, as a compound of the demonstrative ada (for adas), and the neuter form kit of the intcrrogativo base ki; although it is not immediately apparent hew the meaning of “only” can be obtained from elements signifying literally, “that what?” For observations on the suffix in kit, see Bepp's Comparativo Gram. s. 390, sqq. The resemblance of the Pers. andak, and Turkish anjak, is perhaps’ accidental, for the one seems to be the diminutive of and ![]() and the terminal guttural in the other is probably a Seythic affix.

and the terminal guttural in the other is probably a Seythic affix.

2note page 14 Adas, in Sanskrit, is in Bopp's opinion, (Comp. Gr. s. 350,) compounded of the base a, and of a suffix which also occurs in i-dam, “this,” as well as in the Latin i-dem, qui-dam, &c. It is, I believe, the only neuter form in Sanskrit which has a terminal s; and Bopp, even in that case, does not allow the said termination to be primitive, but considers das to be a weakened form of dat.

1note page 15 From observing many other examples, I can now affirm that it is a fixed rulo of the old Persian language, that the pronominal neuter characteristic, whether it be s or t, should be every where elided except before the indefinito particle chiya.

2note page 15 In examining the Babylonian writing, I have become aware of a connection between the forms of the pronoun of the 1st pers. in the Arian and Semitic languages, to which I, must devote a brief explanation. In the Arian languages we may take the Sans, ah as the truo base, which has become as in Zend; ad in old Persian; ἐγ in Greek; eg in Latin; ik in Goth; ih in old Ger.; aszin Lithuanian; az in old Slavonic, &c. To this base has been added in many of these languages a suffix, for the purpose, as it would seem, of specification, and wo have thus ah-am; az-ěm; ad-am, ἐγ-ών whence ὲγ-ώ, and ego. Now, the same base has been employed in the Semitic languages, but instead of the suffix in am being appended, it has been prefixed to the pronoun under the form of an, (which seems to mark it as a definito article,) and in most of the later languages this article has remained as the dominant element, while the true base has been almost lost. Thus in Babylonian, preceded by the distinctive sign, wo have ak or, aka for ego, but without the sign, anak or andka; and in the same way wo havo the compound forms ![]() in Heb.;

in Heb.; ![]() in Coptic; and ἴωνγα in Æ Gr.: whilst in the Heb.

in Coptic; and ἴωνγα in Æ Gr.: whilst in the Heb. ![]() the Chald.

the Chald. ![]() ; the Syr.

; the Syr. ![]() ; the Arab.

; the Arab. ![]() ; and Æ.

; and Æ. ![]() : the true baso has been almost absorbed in the article. The samo analysis must be applied to the 1st pers. plur. as well as to the pron. of the 2nd pers. Compare Bepp's Comp. Gr. s. 320; Pritchard on the Celt. Lang. p. 110; Gescn. Lex., Erig. Ed. p. 79; and Conant's Translation of the Lehrgebädude, p. 30, foot note.

: the true baso has been almost absorbed in the article. The samo analysis must be applied to the 1st pers. plur. as well as to the pron. of the 2nd pers. Compare Bepp's Comp. Gr. s. 320; Pritchard on the Celt. Lang. p. 110; Gescn. Lex., Erig. Ed. p. 79; and Conant's Translation of the Lehrgebädude, p. 30, foot note.

1note page 16 That this affix is ama rather than ma is proved, I think, not only by the orthegraphy of paruvama, but by that also of anuvama, which would otherwise be written paruma and anuma, and wo have here therefore the samo baso with a euphenic prosthesis which occurs in the Gr. ἑμὲ, ἑμοῦ, ἑμέθεν, & c, and in the Pcrs. affixed am. It is doubtful, hewever, if in anuvama the affixed ama does not represent the locative rather than the ablat. case, for in the phrase anuva ‘Ufrátauvá, the former appears to be the case employed.

1note page 17 For observations on this gen. form, see Bepp's Comp. Gr. s. 330, and consult the extensive list of cognate Scythic forms given by Pritchard in his Researches into the Physical Hist, of Man, vol. IV., p. 390, and by Klaproth, in his Sprachatlas, pp. 10, and 30, 31.

2note page 17 If vayam stand for vé+am, as philologers aro now agreed, it follows that the Zend vaem sheuld be equal to vai+ěm. According to Burnouf, however, ![]() can only be explained as a contraction of aya, and the Zend therefore is not a primitive but a secondary fonn, less ancient than its Cuneiform correspondent. (See Yaqna, surl'Alph. Zend, p. 55.) The termination in é being the regular pronominal plural characteristic, vé must be referred to a sing, va, and that this va again is in its origin identical with ma, the base of the oblique case in the singular, is rendered extremely probable by the analogy not only of the Scythic, but of the Semitic plurals. Thus in all the Turkish dialects the plur. is formed by a suffix of number, from the singular. Conf. Mong. bi, I, aadbi-da, we; Mandshu, bi and be; Turk, ben and biz, and particularly Finnish ma and me; and in the Semitic languages it must be observed, that the terminal na or nu, which distinguishes the 1st person plur. is also in reality a suffix of plurality, evidently allied to the plural-ending in verbs and in masculine nouns, in all of which a nasal is the chief element. Thus

can only be explained as a contraction of aya, and the Zend therefore is not a primitive but a secondary fonn, less ancient than its Cuneiform correspondent. (See Yaqna, surl'Alph. Zend, p. 55.) The termination in é being the regular pronominal plural characteristic, vé must be referred to a sing, va, and that this va again is in its origin identical with ma, the base of the oblique case in the singular, is rendered extremely probable by the analogy not only of the Scythic, but of the Semitic plurals. Thus in all the Turkish dialects the plur. is formed by a suffix of number, from the singular. Conf. Mong. bi, I, aadbi-da, we; Mandshu, bi and be; Turk, ben and biz, and particularly Finnish ma and me; and in the Semitic languages it must be observed, that the terminal na or nu, which distinguishes the 1st person plur. is also in reality a suffix of plurality, evidently allied to the plural-ending in verbs and in masculine nouns, in all of which a nasal is the chief element. Thus ![]() is the plur. of

is the plur. of ![]() and retrenching the prefixed article and the plur. sign

and retrenching the prefixed article and the plur. sign ![]() , we find the singular base

, we find the singular base ![]() exchanged for

exchanged for ![]() . In the same way the

. In the same way the ![]() in

in ![]() , the Arab. Correspondent of

, the Arab. Correspondent of ![]() , is the true pronominal base which has been lost in the sing.

, is the true pronominal base which has been lost in the sing. ![]() It is remarkable, hewever, that in almost all the Arian tongues, in the plural of the 1st pers. The pronominal base has given way altogether to the suffix of number; for wo can hardly doubt that the nasal in

It is remarkable, hewever, that in almost all the Arian tongues, in the plural of the 1st pers. The pronominal base has given way altogether to the suffix of number; for wo can hardly doubt that the nasal in ![]() , Lat. nos; Russ. nas; Welsh ni, &c. is to be thus explained. The Median plurals aro of great importance in illustrating this question, and will be considered hereafter.

, Lat. nos; Russ. nas; Welsh ni, &c. is to be thus explained. The Median plurals aro of great importance in illustrating this question, and will be considered hereafter.

1note page 18 For Bepp's remarks on asmé and asmákam, see Comp. Gr. s. 332, and the “Remark” added to section 340. He clearly shews that the termination of asmákam is a posscssivo suffix allied to the Hindustani ká, ké, kí. In the Cuneiform amakham, the lapse of the sibilant before the nasal is regular, but I am quite unable to explain the reason of the aspiration of the guttural.

2note page 18 I shall have repeated occasion hereafter to notice the employment of the middle for the passivo voico, as in agaubatá, “he was called;” agarbáyatá, “he was seized,” &c.

3note page 19 See the notes to ájamiyá, where I have shown that the reading of ániya for ábiya adopted by Lasscn, on the autherity of Westergaard, has been since retracted. I believe, therefore, that ániya, as a derivative from the root ![]() , must be rejected from the Vocabulary.

, must be rejected from the Vocabulary.

1note page 20 According to Bepp, the Sans. ![]() is formed of the base

is formed of the base ![]() and the relative

and the relative ![]() , and this appears to be fully berno out by Us analysis and examples. See Comp. Gr. s. 374, whero the following terms aro compared: Sans,

, and this appears to be fully berno out by Us analysis and examples. See Comp. Gr. s. 374, whero the following terms aro compared: Sans, ![]() ; Latin alius; Prakrit anna; Goth. alya; Gr. ἄλλος old Germ, alles, &c. In the Cuneiform aniya the i is undoubtedly euphenic, being introduced to combine the n and y, which will not unito. in a compound articulation. The base ana is also extensively employed in Zend.

; Latin alius; Prakrit anna; Goth. alya; Gr. ἄλλος old Germ, alles, &c. In the Cuneiform aniya the i is undoubtedly euphenic, being introduced to combine the n and y, which will not unito. in a compound articulation. The base ana is also extensively employed in Zend.

1note page 21 I have before observed, that where a terminal s does occur in a Sanskrit neuter, as in ![]() , it is considered by Bopp to be the weakened form of a primitive t, (see Comp. Gr. s. 350,) but perhaps the Cuneiform examples of aniyash and awash may change the Professor's opinion.

, it is considered by Bopp to be the weakened form of a primitive t, (see Comp. Gr. s. 350,) but perhaps the Cuneiform examples of aniyash and awash may change the Professor's opinion.

2note page 21 For a full explanation of the enclitical power of the Zend ![]() see Yaçjna, p. 27, and Bepp's Comparative Grammar, (Eng. Edit.) p. 163. Rosen also has a note. on the enclitical power of the Vedic chana, in his explanation of 1. 7, Hymn xviii. of the Rig Veda. See his “Adnotationes,” p. xliv.

see Yaçjna, p. 27, and Bepp's Comparative Grammar, (Eng. Edit.) p. 163. Rosen also has a note. on the enclitical power of the Vedic chana, in his explanation of 1. 7, Hymn xviii. of the Rig Veda. See his “Adnotationes,” p. xliv.

3note page 21 If Bepp's theory be true of the common derivation of the Sanskrit pronominal inflexions from the particle sma appended to the base, we sheuld expect to find the same orthegraphy in the ablat. aniyand, and in the genitive amákham, the one being for anya-smát, and the other for a-smákam; I cannot pretend to dispute his theory, (Comp. Gr. s. 166 and 183,) supported as it is by Zend and Pali analogy, yet the uniform employment of the suffix in ná for the old Persian pronominal sing. ablat. (compare aniyaná with aná and tyaná,) certainly indicates a distinction from the particle ma (for sma), which occurs in the plur. of the lst person.

4note page 21 On further consideration, I prefer comparing the Cuneiform inflexion in ‘uvá. (for huvá) with the primitive Sans, ![]() , which in Zend has become

, which in Zend has become ![]() , hva rather than with the contracted form of

, hva rather than with the contracted form of ![]() . For an explanation of this point, see under the head dahyaushuvá.

. For an explanation of this point, see under the head dahyaushuvá.

1note page 22 Bagáha is formed like the Vcdic ![]() and like all the Zend plur. Nominatives in

and like all the Zend plur. Nominatives in ![]() , áoñhó (See Comp. Gr. s. 220.) Aniya also may be supposed in the old Persian to follow the adjectival as well as the pronominal form of inflexion, and aniyá will thus be the regular correspondent of

, áoñhó (See Comp. Gr. s. 220.) Aniya also may be supposed in the old Persian to follow the adjectival as well as the pronominal form of inflexion, and aniyá will thus be the regular correspondent of ![]() :

:

2note page 22 The expression anairyáo dañghávó occurs in the Zend Avesta, in the hymn to Ashlad, and is undoubtedly, therefore, of very high antiquity. Burnouf believes the prefix to be the more privative particle, and translates accordingly, “the non-Arian provinces.” I prefer, hewever, considering an to be a contraction of aniya. See Yaçna, Notes, &c, p. lxii.

1note page 23 In col. 4, 1. 53, at Behistun, wo have, I think, also the compound term anuvama, “after me,” formed like hacháma and paruvama; and as tlio affix of the 1st pers. in hacháma is certainly in the ablat. case, wo must cither suppose that anu governs the ablat. as well as the locat., or that ama, as an affix, represents the two cases indifferently.

2note page 23 ![]() in Sanskrit, is of the first class, and is moreover one of the few roots which, in the causal form, lengthen the vowel

in Sanskrit, is of the first class, and is moreover one of the few roots which, in the causal form, lengthen the vowel ![]() to

to ![]() , instead of introducing the guna; so that it is impossible to Bay in the Cuneiform gaudaya, whether we have a change of conjugation from the first to the tenth class, or whether it may not rather be the regular gunaed causal form. The change also of an aspirate to a dental as a radical letter is suspicious.

, instead of introducing the guna; so that it is impossible to Bay in the Cuneiform gaudaya, whether we have a change of conjugation from the first to the tenth class, or whether it may not rather be the regular gunaed causal form. The change also of an aspirate to a dental as a radical letter is suspicious.

1note page 24 This adverb must have teen very early used with a special referenco to a difference of time as in the English “after,” for the Chaldeo ![]() , “at length,” (Ezraiv. 13,) and the Pehlevi afdom, “the last,” (as in Ardewán el Afdom, Artabanus the last Arsacidan king), are unquestionable cognate forms, the τ according to custom being changed to a nasal.

, “at length,” (Ezraiv. 13,) and the Pehlevi afdom, “the last,” (as in Ardewán el Afdom, Artabanus the last Arsacidan king), are unquestionable cognate forms, the τ according to custom being changed to a nasal.

2note page 24 Burnouf has fully examined the Zend ![]() , aparěm, and compared it with the

, aparěm, and compared it with the ![]() (in posterum) of the Rig Veda, in the continuation of his Zend researches, published in the Asiatic Journal of Paris. See Journal Asiatiquc, IVme Série, torn. V., No. XXIII, p. 296.

(in posterum) of the Rig Veda, in the continuation of his Zend researches, published in the Asiatic Journal of Paris. See Journal Asiatiquc, IVme Série, torn. V., No. XXIII, p. 296.

1note page 25 Bepp has given good reasons for supposing the terminal u in Sans, locatives of the second and third declensions, (bases in i and u,) to be a vocalization of s, and he would make ![]() therefore to be the original form of

therefore to be the original form of ![]() . (See Comp. Gr. s. 198.) I have before observed, (under the head Athuráyá,) that the suffix in ám for the same caso is also a corruption of ás, and it may thus be immaterial with which of the Sans. loc. terminations we compare the Cuneiform iyá.

. (See Comp. Gr. s. 198.) I have before observed, (under the head Athuráyá,) that the suffix in ám for the same caso is also a corruption of ás, and it may thus be immaterial with which of the Sans. loc. terminations we compare the Cuneiform iyá.

2note page 25 « The Zend also has a preposition ![]() , aoi, or

, aoi, or ![]() , aiwi, which signifies “on “or “towards,” and which, as well as

, aiwi, which signifies “on “or “towards,” and which, as well as ![]() is probably connected with the Cuneiform abiya: See Yaçna, Alphab. Zend, p. lxiii, noto 22 ; and Bepp's Comp. Gr., 8. 45.

is probably connected with the Cuneiform abiya: See Yaçna, Alphab. Zend, p. lxiii, noto 22 ; and Bepp's Comp. Gr., 8. 45.

1note page 26 Gesenius has a curious note on the origin and employment of this particlo in the Semitic languages, in his Lexicon, (Eng. Ed.) p. 122.

2note page 26 In Sanskrit ![]() is “a servant,” but

is “a servant,” but ![]() ;, “a magical observance” Abichari, perhaps, in the old Persian, is equivalent to the latter term, the suffix in i giving the same power as the causal form of the root.

;, “a magical observance” Abichari, perhaps, in the old Persian, is equivalent to the latter term, the suffix in i giving the same power as the causal form of the root.

1note page 28 I. do not remember to have met with the 2nd pers. sing. prcs. of the substantive verb in Zend, but I presume that the form must be ahi, agrecably to the orthegraphical rules of the language.

2note page 28 M. Burnouf has an excellent note on the suppression in Zend of s in the initial group sm, (Yaçna, Notes, &c., p. lxvii. Noto O,) and he explains the substitution of mahi for smasi, in the 1st pers. plur. of the ind. pres. by supposing the personal characteristic to be detached from the root; but this restriction will certainly not apply to the substant. verb in the languago of the inscriptions, for the s which is lost in amiya and amahya is radical, and has no connexion with the personal endings.

1note page 29 For a full comparison of the Zend and Sans, forms of the past tenses of the substantivo verb, see Burnouf's Yaçna, Alph. Zend, p. cxviii, and p. 434, noto 290.

2note page 29 See Rad. Ling. Sans., p. 300. It is curious that I do not find this form of asat, either in Bopp, Lassen, or Burnouf. The Vedic form which they invariably quote is ás. See Lassen's Ind. Bib., torn. I I I. , p. 78; and Bopp's Sana. Gram. p. 331. (I havo since found asat in the Rig Veda, Hymn ix., 1. 5. See Rosen's Notes, p. xxviii.)

3note page 29 On further consideration I am disposed to think that this distinction of quantity between the 3rd pers. sing. and plur. cannot be maintained. In the Vedic ![]() , asat, the temporal augment has evidently been dropped, as is very frequently the caso in that dialect, and the samo explanation is to be given of the Zend aghat, which is formed witheut the augment, according to the almost universal rule of that language; as áham stands for

, asat, the temporal augment has evidently been dropped, as is very frequently the caso in that dialect, and the samo explanation is to be given of the Zend aghat, which is formed witheut the augment, according to the almost universal rule of that language; as áham stands for ![]() ásam, so áha in the sing, must be for ásat, and in the plur. for ásan. The latter term, indeed, actually exists, and the former, (as Bepp has remarked, Comp. Gr. s. 532,) was probably the true and original form of the modern

ásam, so áha in the sing, must be for ásat, and in the plur. for ásan. The latter term, indeed, actually exists, and the former, (as Bepp has remarked, Comp. Gr. s. 532,) was probably the true and original form of the modern ![]() , ásít. The object of the Sans. in irregularly introducing a conjunctive vowel after the root, (notwithstanding that the verb is of the 2nd class,) has been to prevent the personal characteristics from being lost, but thcro aro only a few roots in the language, or

, ásít. The object of the Sans. in irregularly introducing a conjunctive vowel after the root, (notwithstanding that the verb is of the 2nd class,) has been to prevent the personal characteristics from being lost, but thcro aro only a few roots in the language, or ![]() , “to be,”

, “to be,” ![]() , “to eat,” and the class

, “to eat,” and the class ![]() ‘in which the peculiarity is found. In the old Persian the preservation of the personal endings in ásat, ásas, and ásan, was impossible, owing to the orthographical law of elision of the silent terminals; but the conjunctive vowel, which was first used with a view to that preservation, has been nevertheless retained. I am not sure that áoghat and áoghěn are genuine forms of the active imperfect of the intlic. mood in Zend; the forms of aghat and aghěn without the augment of past time are more regular, but still it is with the former that wo must compare the Cuneiform áha. See Comp. Gr. s. 530 sqq., and Yaçna, Notes, p. cxiv.

‘in which the peculiarity is found. In the old Persian the preservation of the personal endings in ásat, ásas, and ásan, was impossible, owing to the orthographical law of elision of the silent terminals; but the conjunctive vowel, which was first used with a view to that preservation, has been nevertheless retained. I am not sure that áoghat and áoghěn are genuine forms of the active imperfect of the intlic. mood in Zend; the forms of aghat and aghěn without the augment of past time are more regular, but still it is with the former that wo must compare the Cuneiform áha. See Comp. Gr. s. 530 sqq., and Yaçna, Notes, p. cxiv.

1note page 30 Bepp, hewever, considers mahi in the 1st pers. plur. of the mid. imperf. as an abbreviated form of madhi, comparing it with the Greek μεθα and the Zend maidhé, in the samo way as he derives mahé in the primary forms from madhé. It is perhaps, indeed, only in the activo pres. tenso that there is any reason for supposing the Vedic dialect to have employed a termination in wast. Compare Bepp's Comp. Gr. ss. 439, 472, and 536, with Yagna, Notes, p. lxx.

2note page 30 I am not aware that we have the middle imperfect of the sub. verb standing alone, either in Zend or in the Vedic or classical Sanskrit. I follow Wilkins, (p. 187,) and Bopp's Comp. Gr. S..544, for the forms which occur in composition, supposing the verb to be conjugated regularly in this tense according to the second class.

1note page 31 I find the Vedic bhaváti quoted by Westergaard in Iris Median Memoir, p. 390, and mairyáiti occurs in the Vendidad Sadé, p. 240. Bepp also exemplifies this rule by further Vedic, Zend, and Greek examples in his Comparative Grammar, s. 713.

2note page 31 There is, however, the same irregular aspiration of the dental as the initial letter of thakatá, “then.”

3note page 31 See Rosen's Adnotationes to his Spec. Rig Ved., p. xxiv.

1note page 32 For an analysis and explanation of these Zend terms, See Yaçna, pages 7 and 21.

2note page 32 Herodotus particularly mentions the absence of all the paraphernalia of sacrificial worship in the devotions which the Persians paid to the Gods, οὔτε βωμοὺς ποιεῦνται, οὓτε πῦρ ἀνακαί;ονσι μελλοντες ![]() ο ὐ σπονδῦ χρέωνται, οὐκὶ αὐλῶ, οὐ στέμμασι, οὐκὶ οὐλῦσι, but he still asserts that a victim was immolated, while the sacred chaunt was being performed, μάγος ἀνἠρ παρεστεὠς ἑπαεί;δει θεογονί;ην. Lib. I., c. 132. In support of my theory I may further observe, that while the Assyrian and Babylonian Bculptures abeund with representations of sacrificial worship, there is not a single trace at Pcrscpolis of the immolation of victims.

ο ὐ σπονδῦ χρέωνται, οὐκὶ αὐλῶ, οὐ στέμμασι, οὐκὶ οὐλῦσι, but he still asserts that a victim was immolated, while the sacred chaunt was being performed, μάγος ἀνἠρ παρεστεὠς ἑπαεί;δει θεογονί;ην. Lib. I., c. 132. In support of my theory I may further observe, that while the Assyrian and Babylonian Bculptures abeund with representations of sacrificial worship, there is not a single trace at Pcrscpolis of the immolation of victims.

3note page 32 The Magophenia, which is commemorated ,by Herod. 1. 3, c. 79, as well as by Ctesias and Agathias, has been a fruitful source of difficulty to these modern writers, whe supposo Darius to havo been the founder rather than the subverter, of Magism. See particularly the bungling explanation given by the Abbé Fouchcr, in his Paper on the S. cond Zoroaster, in the Mém. de l'Académic, torn. XLVI. p. 458. (12mo Edit.)

1note page 33 We have another example in the inscriptions of the post-position of the particle in the employment of pathya, and the same construction is sufficiently common beth in Zend and Sanskrit.

2note page 33 The expression harañm běrězaitim occurs in threo passages of the Zend Avesta as the name of the Elburz in the accusative case, and ![]() is again found in its proper sense of “a mountain,” in the hymn to Mithra, (taró harañm açnaoiti, “montem transsilit,”) given in Burnouf's Yaqna, Notes, &c, p. lxvi.

is again found in its proper sense of “a mountain,” in the hymn to Mithra, (taró harañm açnaoiti, “montem transsilit,”) given in Burnouf's Yaqna, Notes, &c, p. lxvi.

3note page 33 That the Ar or Har of this namo signifies “a mountain,” I shall show under the head Armina.

4note page 33 For observations on. the Pehlevi Ar Parsin and Ar Burz, see Muller's Essay in the Journ. Asiat., for April, 1039, p. 337.

1note page 34 I have sometimes surmised that in this name we have the vernacular orthegraphy of the Greek Πασαργάδαι, but there are strong historical objections to the identification, which I shall state hereafter.

2note page 34 Fahraj would be the Arabicized form of the Persian Pdhrag. The name still attaches to a place between Shiraz and Kermán.

3note page 34 I conjecture this passage to be improperly pointed in the printed editions of Pliny. By placing a stop after rege, we may read,—“These Magi had a city named Ecbatana in the mountains, which was removed by King Darius.” See Pliny, 1. VI., c. 26.

4note page 34 The Persian orthegraphy of the namo is reproduced with little variation in the Median and Babylonian transcripts.

1note page 35 Lib. VI., c 98.

2note page 35 Burnouf has some good remarks on the use and derivation of ěrěta or arta, in his Commentary on the Yaçna, p. 474; Lasscn, also, in his last Cuneiform Memoir, p. 162, compares with the same term, the title of ἀρταῖοι, which Herodotus applies to the ancient Persian race, (lib. VII., c. 61) ; but which rather appears from Stephen and Hesychius to have been a particular epithet given in the vernacular dialect to the heroes of Persian romance. See these authers in vocc, and compare also the explanation given by Hesychius of ἀρτάς; μέγας καὶ λαμπρὶς

1note page 36 The Parthian name occurs in the bilingual inscription of Hajiabad. For the Sassanian orthegraphy, sce Do Sacy's Persian Antiquities, p. 100. In the Greek inscriptions of Persepolis wo havo the genitive ἀΡΤΑΞΑΡοΓΥ. Agathias continues to apply to the Achæmenian king the name of ἀρταξέρξης but he uses the orthegraphy of ἀρταξάρης for the first monarch of the Sassanian line, and in the reading of ἀρταξὴρ which he employs in speaking of the second monarch of the same name in that dynasty, he approaches, still more nearly to the Persian pronunciation. George of Pisidia writes Ἄρτεσις, which is a transcript of the Armenian form of the name. I find also in the Bun-Dehesh the truo Pehlevi form of ![]() , Ardashír.

, Ardashír.

2note page 36 These forms are taken from the inscription on the Venice Vase, noticed in p. 340 in the former chapter, and of which I have since found a detailed account in Westergaard's Median Memoir, p. 420. The difficulty of reading the Babylonian name arises from the doubtful figure of the fourth character.

1note page 37 For a comparison of the Sanskrit vrǐlta, Zend věrětó and Pazend vart, See Burnouf's Yaçna, p, 435, Note 290. The Sanskrit vrǐta, “selected,” which orthegraphically answers to the Zend věrěta, cannot be compared with the Cuneiform vardiya, for in the latter term the dental is radical, and does not belong to a participial suffix.

2note page 37 I once thought that we had in this name the title of ἀρτΥστώνη, the favourite queen of Darius, (see Herod. 1. VII., c. 69,) but I havo been compelled to abandon the idea, as the noun cannot be of the feminine gender.

3note page 37 See especially the note marked2 under the head Athagaina.

4note page 37 Jacquet recognized the Zend ěrědhwa in the ὈρθοκορΥβάντης “the high mountains” of Herodotus, (1. III., c. 92,) and he was probably right, for the district still retains the name of Bάlά Giriweh, which has the samo meaning. I believe also, that we have the Zend ěrědhwa, or Cuneiform arda, both in the name of Ardastán which attaches to the mountains west of Persepolis, and in Ardabil, “the hills of the shepherds.” In other Persian geographical names, such as Ardakán, Ardashir, Ardashat, Ardabád, we have probably the old Aria, or Zend arěta, the chango of the dental from the surd to the sonant grade being agreeable to the genius of the modern language.

1note page 38 There is a very remarkable difference in the Median orthegraphy of this name, as it is given in Westergaard's published copy of the Nakhsh-i-Rustam Inscription, and as I find it in Dittel's manuscript copy of the sarao writing, a difference which is of much importance in regard to the Median alphabet, but which I am unable at present to resolve. In the Babylonian transcript the name is unfortunately imperfect.

2note page 38 For remarks on the namo of Arabia, see Gcs. Lex. in voco ![]() .

.

1note page 39 Libi XVI., pago 737. The Greeks had a tradition that Arbela was founded by a certain Arbelus, one of the Athenian leaders whe followed Medea into Asia. See torn. V., p. 160, Noto 1, of the admirablo translation of Strabe published by the French Academy. Under the lower empire the site was known as ἀλεξανδρί;ανοι See Bekker's Theophylact, p. 219.

2note page 39 Dio Cass., 1. LXXVIII., c. 1; Curtius also, (1. V., c. 1,) mentions that Arbela contained the royal treasures.

3note page 39 Chap. IV., v. 9. The initial ![]() substituted for

substituted for ![]() in this title, I suppose to be the Chaldeo demonstrative pronoun, or rather article, which is, I believe, to be frequently recognized in Assyrian and Babylonian names. Compare in Ptolemy, Τεσκάφη or Σκάφη, (mod.

in this title, I suppose to be the Chaldeo demonstrative pronoun, or rather article, which is, I believe, to be frequently recognized in Assyrian and Babylonian names. Compare in Ptolemy, Τεσκάφη or Σκάφη, (mod. ![]() Askaf); ΔιδοὸοΥα or Δί;γοΥα, mod.

Askaf); ΔιδοὸοΥα or Δί;γοΥα, mod. ![]() Diklah,) &c, &c. Gesenius, in voce, does not venture to identify the Tarpelites; he merely compares the Ταρφαλαῖοι of the Septuagint, and it is certainly against the suggestion I have offered that the Syriac.translation of the verse in Ezra employs the orthegraphy of

Diklah,) &c, &c. Gesenius, in voce, does not venture to identify the Tarpelites; he merely compares the Ταρφαλαῖοι of the Septuagint, and it is certainly against the suggestion I have offered that the Syriac.translation of the verse in Ezra employs the orthegraphy of ![]() , where the l is entirely lost.

, where the l is entirely lost.

2note page 40 Gesenius compares with the Heb. ![]() the Gr. ὄρος, and Slavie gora; but if the latter term be admitted as of cognato origin, wo must also include in the list the numerous correspondents which exist for the Sans,

the Gr. ὄρος, and Slavie gora; but if the latter term be admitted as of cognato origin, wo must also include in the list the numerous correspondents which exist for the Sans, ![]() througheut the family of the Arian languages.

througheut the family of the Arian languages.

2note page 40 I believe that the name of Armani occurs repeatedly in the Mcdo-Assyrian Inscriptions of Van, which was actually within the limits of the ancient Armenia; and yet we have there what may be supposed to be the vernacular reading without the initial aspiration.

1note page 41 In beth passages it unfortunately happens that the termination is defective, and as I transcribed the paragraph from the rock in the Roman character, it is very possible I may have inadvertently written mi for ma.

2note page 41 It would appear as if the Persians regarded the titlo as a noun in which the affixes in ina and aniya might be employed indifferently. The Median everywhere has the ending in aniya, but the double orthegraphy is, I think, to be found in the Medo-Assyrian, and the early Arabs wroto  Armin as often as

Armin as often as  Arminiya. The Greeks, it is well known, referred the name to the Thessalian Armcnus, one of the Argonauts, (Strab., p. 530,) while the natives of the country pretend to derivo it from Armenac, one of their pristino kings.

Arminiya. The Greeks, it is well known, referred the name to the Thessalian Armcnus, one of the Argonauts, (Strab., p. 530,) while the natives of the country pretend to derivo it from Armenac, one of their pristino kings.

3note page 41 Lib. VI., c. 20.

1note page 42 See Herod, lib. VII., cap. 11 and 224.

2note page 42 M. Burnouf, however, will not admit the r in Arshashang to be a radical letter; he believes it to be introduced before the hard sibilant, in many names in Zend, and in this name in particular, by a certain natural tendency of articulation, (see Yaçna, pp. 437 and 470); and the combined examples of Ashaka on the Eastern coins of Arsaces, (see Cunningham's Plates, No. 15) of ασαάκ, the Parthian capital mentioned by Isidore of Charax, and of the Persian ![]() Ashak, are apparently in favour of his theory. The Median orthegraphy of Arsames is also, I think, Ahsháma, an aspirate almost always replacing the r in Median before a sibilant.

Ashak, are apparently in favour of his theory. The Median orthegraphy of Arsames is also, I think, Ahsháma, an aspirate almost always replacing the r in Median before a sibilant.

3note page 42 See St. Martin's Armenia, tom. I., p. 411.

1note page 43 See above, under the head Ayad(a)na.

2note page 43 I have the Median arikka in the translation of the thirteenth paragraph of the fourth column at Behistun. The term also occurs in the same evil sense in line twenty-four of the Median Inscription (II) on the outer wall at Persepolis, where however Westergaard (see his Copenhagen Memoir, p. 411,) has altogether mistaken the meaning.

1note page 44 See in particular Lassen's Indische Alterthumskunde, p 55,; Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 460, Note 325; and Wilson's Ariana Antiqua, p. 121.

2note page 44 Compare the Persian ![]() or

or ![]() , and I think also Gr. ἤ, and Heb.

, and I think also Gr. ἤ, and Heb. ![]() The Lat.vir; Gr. Fίἠρωσ Scyth. οἰὸρ Celt. Fear, Gwr, Wr, 'c., are probably referable to another root, Sans.

The Lat.vir; Gr. Fίἠρωσ Scyth. οἰὸρ Celt. Fear, Gwr, Wr, 'c., are probably referable to another root, Sans. ![]() , althouth Gesenius connects them. See Robinson's edition of the Heb. Lox., p. 50.

, althouth Gesenius connects them. See Robinson's edition of the Heb. Lox., p. 50.

3note page 44 A'rya-búmi and A'rya-desa are also usual in Sanskrit in the same sense.

4note page 44 I suppose-these wars to be figured in Greek fable by the conflict between Perseus and Cepheus. In Persian romance, Feridún was probably the leader of the Arian immigration. The old Seythic speech is that I suspect of the Median tablets.

5note page 44 The Zend ![]() vaejo, answering to the Sans.

vaejo, answering to the Sans.![]()

6note page 44 See the quotations in Burnouf's Yaçna, Notes, üller.

8note page 44 Lib. VII., c. 62.

1note page 45 Quoted by Nicol. Damase, in Libro περὶ αρρῶν I follow the text as it is given in Hyde, p. 292.

2note page 45 See Steph. de Urb., in voce αριάνια in my Mem. on Ecbatana I have also shown its application to the Median Capital. See Journ. Royal Geog. Soc, v. X., p. 139.

3note page 45 For the Eastern Ariana, see Plin., 1. VI. c. 2 3; Dionys. Per., 8. 1098; ælian, de Animal., XVI., c. 16; Tac. Annal., 1. XI, c. 10, &c. We must be careful not to confound Ariana with Ἀρια or Herat, in Zend ![]() and in the inscriptions Hariva.

and in the inscriptions Hariva.

4note page 45 See throughout the second chapter of Strabe's fifteenth beok.

5note page 45 For these notices, see De Sacy's Mem. sur Div. Ant. de la Perse, p. 48. St. Martin's Armenia, tom. I., p. 274, and Quatremère's Hist des Mongols, tom. I., p. 241, Note 76.

6note page 45 The epenthetic i was introduced into the Sassanian Airán through the Zend, agreeably to a law of orthegraphy which obtains in the latter language.

7note page 45 I take the Parthian Arián and An-árián from the bilingual inscription of Sapor, in the cave of Hajiábád, which affords several other very valuable readings.

8note page 45 The names of ![]() and

and ![]() are undoubtedly identical, as.has been shown by Müller, in his Essai sur le Pehlevi, Jour. Asiat. Soc, tom.VII., p. 298. I think I discover the reason of the interchange of the Pehlevi terminations in án and ák, which is incontestable, in a certain guttural power inherent in the Babylonian nasal, beth the one form and the other being referable to a primitive ánk. The name of Irán, however, must have been very early subjected to this corruption; for the terms αρυὶκαι αναριάκαιArauca, &c, are common to the Greek and Latin geographers. See Strab. XI., 7; Ptol. VI., 2 and 14; Plin. VI, 19; Orosius, 1. I., c. 2, &c.

are undoubtedly identical, as.has been shown by Müller, in his Essai sur le Pehlevi, Jour. Asiat. Soc, tom.VII., p. 298. I think I discover the reason of the interchange of the Pehlevi terminations in án and ák, which is incontestable, in a certain guttural power inherent in the Babylonian nasal, beth the one form and the other being referable to a primitive ánk. The name of Irán, however, must have been very early subjected to this corruption; for the terms αρυὶκαι αναριάκαιArauca, &c, are common to the Greek and Latin geographers. See Strab. XI., 7; Ptol. VI., 2 and 14; Plin. VI, 19; Orosius, 1. I., c. 2, &c.

1note page 46 ![]() also signifies “excellent” in Sanskrit. Rosen compares ἀρεἰωνᾴριστος,ἀρετή, &c; see Rig-Veda Spec, Notes, p. 20.

also signifies “excellent” in Sanskrit. Rosen compares ἀρεἰωνᾴριστος,ἀρετή, &c; see Rig-Veda Spec, Notes, p. 20.

1note page 47 For observations on the Zend Ráman, seo the explanation of the namo of Rama khastra in Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 219. Seo also Do Sacy's Mem. sur Div. Ant. de ln Persc, p. 210.

2note page 47 Thus ![]() “a horse,” in the Vedas; Aurwat, “swift,” in Zend; “the mountain” Arwand; “the river” ’ο;ρο;άτης, &c., &c. Seo Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 251.

“a horse,” in the Vedas; Aurwat, “swift,” in Zend; “the mountain” Arwand; “the river” ’ο;ρο;άτης, &c., &c. Seo Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 251.

3note page 47 Bopp supposes the suffix in va which occurs in the Sans, ava, eva, iva, sva, &c., to bo connected with the enclitic ![]() “as,” (Comp. Gr. s. 381 and 383), and in accordance with his system of an original identity between pronouns and prepositions, he maintains the Sans.

“as,” (Comp. Gr. s. 381 and 383), and in accordance with his system of an original identity between pronouns and prepositions, he maintains the Sans. ![]() “from,” to be one and the same word with the Zend

“from,” to be one and the same word with the Zend ![]() ava, “this,” (Comp. Gr. s. 377.

ava, “this,” (Comp. Gr. s. 377.

1note page 48 Seo an excellent philological article reviewing “Prichard on the Celtic Languages,” in the Edinburgh Review, vol. LVII., No. CXIII., p. 98.

1note page 49 For some valuable remarks on the Zend ava, see Burnouf's Yaçna, Alphab. Zend, p. lxiii, and Note A, p. iii, of the Notes et Eclaircissemens. Gesenius is wrong, I think, in comparing ![]() with the Heb.

with the Heb. ![]() The Persian word, like the Cuneiform ava, and Zend

The Persian word, like the Cuneiform ava, and Zend ![]() comes from the pronominal root a, and not from the demonstrative sibilant modified to an aspirate.

comes from the pronominal root a, and not from the demonstrative sibilant modified to an aspirate.

2note page 49 See Robinson's Gesenius, in voce ![]() , P270.Where the double employment of the Hebrew pronoun is particularly noticed.

, P270.Where the double employment of the Hebrew pronoun is particularly noticed.

3note page 49 I cannot certainly affirm that the distinction between hau and hauva in com-position is intended to mark a distinction of gender, for at Behistun, col. 2, 1. 70, p.226, we have the term hauvamaiya, “ille mihi,” referring to a mase. antecedent; but still the cxample of haushaiya may be held to provo the terminal ![]() t o he euphonie.

t o he euphonie.

1note page 50 As in the terms ’uvámarshiyush, ‘Uvakhshatara, and ’uváip(a)shayam.

2note page 50 Hagha, indeed, must it would seem be derived from sasva through. the Zend ![]() , hakha, a term which I do not remember to have met with in the Zend writings, but which may have very well existed in the language.

, hakha, a term which I do not remember to have met with in the Zend writings, but which may have very well existed in the language.

3note page 50 See Heb. Lex. (Eng. Edit.) p. 269, with the references to Fulda and Schmittheuner; the Greek ὁ is of course cognate.

4note page 50 Compare Semitic Heb.![]() , and Babylonian sha or asha, “who;” Arian, Sans.

, and Babylonian sha or asha, “who;” Arian, Sans. ![]() ,

, ![]() , “he,” “she,” and the characteristic of the 2nd person in verbs; Goth:, sa, so, “that;” Germ, sie, so; Eng. she; Arm. sa, “this;” Esthon. sa, “thou;” Gr. σν; Irish, so, “that;” se, “he;” sibh, “you;” siad, “they,”&c. and Seythie, Turk, sen, Finnish sina, “thou,” &c. Gesenius, in an excellent note to the Heb.

, “he,” “she,” and the characteristic of the 2nd person in verbs; Goth:, sa, so, “that;” Germ, sie, so; Eng. she; Arm. sa, “this;” Esthon. sa, “thou;” Gr. σν; Irish, so, “that;” se, “he;” sibh, “you;” siad, “they,”&c. and Seythie, Turk, sen, Finnish sina, “thou,” &c. Gesenius, in an excellent note to the Heb. ![]() (Lex., Eng. Ed. p. 111), maintains the primitive demonstrative to be a dental, which passing through th becomes a sibílant.

(Lex., Eng. Ed. p. 111), maintains the primitive demonstrative to be a dental, which passing through th becomes a sibílant.

1note page 51 Since writing the above, I have found a complete explanation of the Cuneiform ![]() in Bopp's Comp. Gr. s. 347. The Sans, base sa should form, of course, according to rule, in the nom. sing. masc. sas, and wo thus actually have the orthography of

in Bopp's Comp. Gr. s. 347. The Sans, base sa should form, of course, according to rule, in the nom. sing. masc. sas, and wo thus actually have the orthography of ![]() : before a stop. The case sign s, however, (which is lost in the common

: before a stop. The case sign s, however, (which is lost in the common ![]() , to avoid, as Bopp says, s. 348, an iteration of the same element, is frequently vocalized to u, and

, to avoid, as Bopp says, s. 348, an iteration of the same element, is frequently vocalized to u, and ![]() , therefore, which occurs beforo words commencing with a is a contraction of sa+u for sas. To this

, therefore, which occurs beforo words commencing with a is a contraction of sa+u for sas. To this ![]() exactly answers the Zend

exactly answers the Zend ![]() hó and I cannot doubt, therefore, thathau is the true orthography of the Cuneiform pronoun. The euphonic va has been added, as a word in the old Persian cannot terminate in u, and it has subsequently remained, (with the exception of the solitary example of haushaiya) as an integral portion of the pronoun. This does not explain, however, the employment of hauva for the feminine, instead of há for

hó and I cannot doubt, therefore, thathau is the true orthography of the Cuneiform pronoun. The euphonic va has been added, as a word in the old Persian cannot terminate in u, and it has subsequently remained, (with the exception of the solitary example of haushaiya) as an integral portion of the pronoun. This does not explain, however, the employment of hauva for the feminine, instead of há for ![]() or

or ![]() , nor does it impugn the connexion I havo proposed to establish between, the Arian and Semitic correspondents; on the contrary, the Zend hó, and Cuneiform hau, (or by extension hauva,) determinatoly, as I think, connect the Hebrew

, nor does it impugn the connexion I havo proposed to establish between, the Arian and Semitic correspondents; on the contrary, the Zend hó, and Cuneiform hau, (or by extension hauva,) determinatoly, as I think, connect the Hebrew ![]() ) with the Sans.

) with the Sans. ![]() and prove the Semitic to be a secondary and later form, by showing that it owes its termination in úa to the vocalization of a case-sign s, which is peculiar to the nominativo of languages of the Arian family. The indifferent employment of hauva, moreover, for the masc. and fem. is a remarkable point of coincidence between the early Hebrew and the language of the inscriptions, and would appear to indicate that the Semites had adopted the term from the Persian branch of the Arian stock of languages.

and prove the Semitic to be a secondary and later form, by showing that it owes its termination in úa to the vocalization of a case-sign s, which is peculiar to the nominativo of languages of the Arian family. The indifferent employment of hauva, moreover, for the masc. and fem. is a remarkable point of coincidence between the early Hebrew and the language of the inscriptions, and would appear to indicate that the Semites had adopted the term from the Persian branch of the Arian stock of languages.

2note page 51 With ava compare the Greek αὐ in αὐ-θι, αὐ-τός, &c., and also the Sclavonic ovo.

3note page 51 Bopp observes in his Comp. Gr. s. 231, (Eng. Edit. p.245,) that “Neuters have in Zend, as in the kindred European languages, a short a for their termination, perhaps the remains of the full as.” The existence of this s, however, can, I believe, hardly bo traced in Zend or Sanskrit, and the Cuneiform terms therefore, avashchiya and aniyashchiya are the more valuable. It is singular, however, that where the neuter s does occur in Sans, in adas, Bopp considers it to be a weakened form of t. See Comp. Gr., s. 350.

1note page 52 Avamsham, which frequently occurs in the inscriptions, is the accus. masc. sing, of the demonstrative pronoun in composition with the genitive plural suffix of the 3rd person.

2note page 52 The Zend avá (instead of aváo) however, for the nom. and accus. masc. plur. of the demonstrative pronoun requires explanation. According to Bopp, (see Comp. Gram., s. 239, and note to s. 231), they must be, I think, neuter forms substituted. for the masculine. Burnouf (Yaçna, Notes, &c, p. ix.) engages to discuss them at some future time.

3note page 52 Bopp (Comp. Gram., note to s. 228,) observes, that “In Zend the pronominal form in é occurs for the most part in the accus. plur.;” but I do not find the reason of this marked disagreement with the Sanskrit.

1note page 53 For an excellent examination of the plural neuter in Zend, see Bopp's Comp. Gr., note to s, 231.

2note page 53 Bopp, however, in the note to s. 234 of his Comp. Gr., decides differently.

3note page 53 Bopp considers the pronominal ending in sám, (which becomes after an i shám, and which in nouns is contracted to ám) to bo the original, and formerly the universal form of the case-suffix of the gen. plur. of the Sanskrit; and ho compares with it the Goth, zé or zo; Germ, ro; Latin rum; and the Gr. endings in αγν and εων for ασων and ![]() . (Sec Comp. Gr. s. 248, and the foot-note to the same).

. (Sec Comp. Gr. s. 248, and the foot-note to the same).

1note page 54 Compare Sanskrit asya, Vedic ayá, Zend and Cuneiform aná, or Sanskrit asmat, &c., &c.

2note page 54 See Comp. Gr. ss. 55 and 341; ![]() sé, in Prakrit, and

sé, in Prakrit, and ![]() he.

he. ![]() hói, and

hói, and ![]() she, in Zend, aro of very frequent employment for the gen. and dat. of the 3rd pers. sing, in all genders. Bopp considers that where we havo shé, sháo, &c, in Zend written with the

she, in Zend, aro of very frequent employment for the gen. and dat. of the 3rd pers. sing, in all genders. Bopp considers that where we havo shé, sháo, &c, in Zend written with the ![]() , the aspiration must bo caused by the influence of a preceding i or u; but in the old Persian the employment of the

, the aspiration must bo caused by the influence of a preceding i or u; but in the old Persian the employment of the ![]() , which is perhaps the primitive form of the base, is certainly independent of all euphonic rules, and has been continued in the modern language.

, which is perhaps the primitive form of the base, is certainly independent of all euphonic rules, and has been continued in the modern language.

3note page 54 See Bopp's Comp. Gr., 8. 248. the German philologist was not awaro of the oxistcnco of the suffix for the gen. plur. of the 3rd pers. or he would probably have compared it with the pronominal ending in ![]() shám.

shám.

1note page 55 Beh., Col. III., 1. 52, p. 234.

2note page 55 See Comp. Gr., ss. 236 and 239.

3note page 55 Shim and shám aro certainly used for the fem. as well as the masc, but I do not think we have any example of the double employment of shiya; shish is a doubtful word.

4note page 55 See the notes to these passages in Chap. IV.

5note page 55 As in the regular plural ending in ani, where the n is simply euphonic. Seo Comp. Gr., sect. 234.

6note page 55 Thero is I find in Zend a pronoun of this exact form, ![]() dít or dísh, which is supposed to bo the instrum. plur. of di, being contracted from

dít or dísh, which is supposed to bo the instrum. plur. of di, being contracted from ![]() dibís. I doubt if the Cunciform

dibís. I doubt if the Cunciform ![]() can represent the instrumental case, but it may well bo referred to the same demonstrative baso di, (connected according to Bopp with ta,) which has produced in Zend dísh or dís in the plur., and the accus.

can represent the instrumental case, but it may well bo referred to the same demonstrative baso di, (connected according to Bopp with ta,) which has produced in Zend dísh or dís in the plur., and the accus. ![]() dim, “him,” in the singular. See Comp. Gr. foot-notd to s. 219, and the referenco which is thero given to Burnouf's Paper in the Nouv. Journ. Asiatique.

dim, “him,” in the singular. See Comp. Gr. foot-notd to s. 219, and the referenco which is thero given to Burnouf's Paper in the Nouv. Journ. Asiatique.

1note page 56 In Zend, however, the usual adverb of manner is ![]() aévatha. where the pronominal root is that which occurs in the Sans, evam, etad, &c. For the general construction of the Zend adverbs, see Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 11 and 12, Bopp discusses the formation of adverbs of “kind or manner,” in his Comp. Gr. s. 425.

aévatha. where the pronominal root is that which occurs in the Sans, evam, etad, &c. For the general construction of the Zend adverbs, see Burnouf's Yaçna, p. 11 and 12, Bopp discusses the formation of adverbs of “kind or manner,” in his Comp. Gr. s. 425.

2note page 56 Bopp observes (loco citato) that the terminations in ![]() and

and ![]() are related to one another as accusative and instrumental, the latter being formed with the long á, and without the euphonic n, according to the principle of the Zend language.

are related to one another as accusative and instrumental, the latter being formed with the long á, and without the euphonic n, according to the principle of the Zend language.

3note page 56 It may bo assumed, I think, as almost certain, that the Turkish case-sign in deh is connected with ![]() and θα' as the ablative den is also certainly allied to the Gr, θεν in ἐκεῖθεν, αὐτόθεν, ἐντεῦθεν, &c.

and θα' as the ablative den is also certainly allied to the Gr, θεν in ἐκεῖθεν, αὐτόθεν, ἐντεῦθεν, &c.

1note page 57 See Burnouf's Yaçna, loc. cit.

2note page 57 See Comp. Gram., (Eng. Ed.) p. 387, and also s. 420 of vol. II., p. 589.

3note page 57 See Comp. Gram., (Eng. Ed.) p. 202, in the note to s. 183.

4note page 57 Perhaps the termination in ava-dasha is after all nothing more than a modification of the Sans. ![]() , with which is allied the Latin tus in cœlitus, and tur in igitur. At any rato the old Germ, yú-dúshe, “from whence,” has tlie same ablativo affix, and that term is compared by Bopp with the Sanskrit

, with which is allied the Latin tus in cœlitus, and tur in igitur. At any rato the old Germ, yú-dúshe, “from whence,” has tlie same ablativo affix, and that term is compared by Bopp with the Sanskrit  yatas. See Comp. Gr. s. 421.

yatas. See Comp. Gr. s. 421.

1note page 58 In my notes to col. 3, par. 11, at Behistun, I havo shown the impossibility of regarding ava as a pronoun united to a postposition, for in that case the antecedent would bo feminine, and the a in ava would bo elongated.

2note page 58 The prosthetic a, so common in Zend and Persian, is not acknowledged in Sanskrit, yet I cannot otherwise explain the orthography of avasathas, for the etymology of the grammarians given by Wilson, (Diet. p. 81,) is evidently forced. In the inscriptions also, although the employment of the prosthesis is certainly very rare, it would bo hazardous to say it were unknown.

1note page 59 This root in Zend becomes ![]() or

or ![]() zan, and in modern Persian

zan, and in modern Persian ![]() zan.

zan.

2note page 59 In this view ávájaniyá will stand for ávájaniyát.

1note page 60 On a more mature consideration I now propose to regard ávájaniyá for ávájaniyát, as the subjunctive imperfect of a denominative verb, formed from ![]() “calling,” with the affix in

“calling,” with the affix in ![]() , preceded by the euphonic in i; and I translate accordingly, “he would declare” or “he would proclaim.” For examples of this tense in Zend and in the dialect of the Vedas, see Bopp's Comp. Gr. s. 714.

, preceded by the euphonic in i; and I translate accordingly, “he would declare” or “he would proclaim.” For examples of this tense in Zend and in the dialect of the Vedas, see Bopp's Comp. Gr. s. 714.

2note page 60 In Sanskrit, the causal form is ![]() sthápaya, instead of

sthápaya, instead of ![]() stháya, but wo may very well suppose the latter to have been the primitive orthography. I see also in Westergaard's Radices, that with a gerund

stháya, but wo may very well suppose the latter to have been the primitive orthography. I see also in Westergaard's Radices, that with a gerund ![]() is employed to denote “duration of an action,” and wo may possibly havo an example of that particular construction in the Cuneiform phrase, gáthwaá avásiáyam. See Rad. Ling. Sans., p. 18.

is employed to denote “duration of an action,” and wo may possibly havo an example of that particular construction in the Cuneiform phrase, gáthwaá avásiáyam. See Rad. Ling. Sans., p. 18.

1note page 61 See Ins. No. 4, 1. 15. I continue to read “dahyáva tyá parauviya,” the Eastern provinces,” parauviya being for ![]() , the locat. sing, of

, the locat. sing, of ![]() “the East.”

“the East.”

2note page 61 Lassen (Pentapot., p. 32,) and Troyer (Raj. Tar., tom. I. p. 501,) are content to derive the affix in Trigarta, (which is still the family name of the Rájas of Jallandhar), from ![]() , “a cavern;” but such an etymology seems to be anything but satisfactory. I shall examine the term in detail, under the head Vardanam.

, “a cavern;” but such an etymology seems to be anything but satisfactory. I shall examine the term in detail, under the head Vardanam.

1note page 62 The Aswas, of Indian romance, were one of the great divisions of the Yadava race. They are first known in classical history as the invaders of Bactria, (Strab. XI., p. 511,) and may bo subsequently traced for a long period in Chinese annals as the dominant race in Persian Khorasan. (See Foĕ Kouĕ Ki, p. 83; Nouv. Melanges Asiat., torn. I., p. 217; and Do Guignes' foot-noto to p. 51, torn. I., Part 2ms of the Hist, des Huns.)

2note page 62 The first immigration of the Asi into the north of Europe is lost in antiquity, but Odin brought in the second colony from Asgard, about the Christian era. the subject has been thoroughly examined by Geijer, in his Schwedens Urgeschichte.

3note page 62 Odin was popularly believed to have brought the Asi from the Euxino.

4note page 62 Lib. III., c. 93; the Σαράγγαι are of course the inhabitants of Zaranj, ![]() , of whom more hereafter. In the Θαμάναι, I recognize the tribe which gave its name to

, of whom more hereafter. In the Θαμάναι, I recognize the tribe which gave its name to ![]() Damaghán,

Damaghán, ![]() Damawend, &c. The Οὔτιοι may, perhaps, be identified with the Yuilyá of the Inscriptions, and the μέκοι colonized

Damawend, &c. The Οὔτιοι may, perhaps, be identified with the Yuilyá of the Inscriptions, and the μέκοι colonized ![]() Mekrán.

Mekrán.

5note page 62 Lib. VII., c. 85; the Pactyans are a disputed race, but may, I think, be compared with the Zend  Baghdhi, which by common consent is identified with Bactria.

Baghdhi, which by common consent is identified with Bactria.

1note page 63 Lib. XLI, c. 1; in all editions of Justin that I have consulted, the name is written Spartani, but this must be an error for Sagartani.

2note page 63 Lib. VI., c. 2; Ptolemy's Geography of Media is very loose; he appears to join Zagros, Orontes, Jasonium (Damawand), and Coronus in a continuous chain, and where he mentions Zagros in allusion to the Sagartii, I understand him to speak of that part of the rango about the Caspian Gates. In his Χωρομιθρήνη I recognize ![]() Khár, although he names the same district in his account of Parthia, Χοροάνη.

Khár, although he names the same district in his account of Parthia, Χοροάνη.

3note page 63 The. ethnography of Persia will be examined in detail hereafter.

4note page 63 In the old authors ![]() now called Shibbergán.

now called Shibbergán.

1note page 64 ![]() the initial letter is the Pehlcvi article. The construction of this fort, which is near the town of Semnám, bears evident, marks of the very highest antiquity.

the initial letter is the Pehlcvi article. The construction of this fort, which is near the town of Semnám, bears evident, marks of the very highest antiquity.

2note page 64 Compare also the Georgian Spár-sálár, a general of cavalry, and see an excellent note on the word in St. Martin's Armenia, torn. I., p. 298. I have already alluded to the Aswas of Indian history, oue of the great Scythic tribes which held the country between the Oxus and the Indus; but I have not explained the subsequent mutations of the name, which aro however full of interest; for according to the Pali rule of simplifying compound grbupes, we havo on the ono hand Assá-can, the Greek 'Ασσακύνοι, and on the other the Appa-goni of Pliny, whence the modern ![]() Afghan the termination in both cases being, as I think, a Seytlhic plural suffix, which was adopted from the same source into the Chaldee and Pehlevi.

Afghan the termination in both cases being, as I think, a Seytlhic plural suffix, which was adopted from the same source into the Chaldee and Pehlevi.

1note page 65 Professor Bopp has elaborately examined this subject in his Comp. Gram. BS. 215–225, and Bumouf's Remarks on the Origin and Uso of the Vowel Modifications in Zend which precede the case-endings, may bo seen in his Commentairo sur le Yaçna, p. 177.

2note page 65 Seo Gesen. Lex., p. 1020, Eng. Edit.: Gesenius, however, pretends to derive ![]() from anobsolcto root

from anobsolcto root ![]() “to bo high.”

“to bo high.”

1note page 66 See under the heads Chartaniya and Thastaniya, where I have given a conjectural explanation of the ending in aniya, and supposed it to represent a gerund of present time, rather than a true present participle.

2note page 66 For an analysis of this pronoun, seo Bopp's Comp. Gram., s. 369, Eng. Edit., vol. II., p. 518. Bopp appears to consider e in ![]() &c., as a distinct pronominal base.

&c., as a distinct pronominal base.

3note page 66 Aitamaiya is no doubt formed on the same principle as avataiya, tyamaiya, &c.; the neuter characteristic having been once lost, cannot be reproduced except by the enclitical power of the particle chiya.

1note page 67 See Comp. Gram., s. 381, Eng. Edit., vol. II., p. 535.

2note page 67 See particularly Burnouf's Yaçna, pp. 70—80.

3note page 67 See the notes to Ins. No. 17, where I have drawn an inference of importance from this remarkable orthography.

4note page 67 Professor Lasscn quotes the Nairukta-Cabda-Sangraha. See the Zeitschrift, P. 16.

1note page 68 Burnouf prefers the latter derivation, and compares δα with the Pers. ![]() dáná “wise,”

dáná “wise,” ![]() dánistan, “to know.” He also shows that the Zend

dánistan, “to know.” He also shows that the Zend ![]() dáo, “knowledgo,”

dáo, “knowledgo,” ![]() dámi, “wise,” the Sans.

dámi, “wise,” the Sans. ![]() dásus, “a sage,” and the Gr. δά-ημι, δι-δά-σκω, &c., are probably derivatives from the same root dá, which, with the sense of “knowing,” however, has been lost to the Sanskrit. See hereafter under the head adáná.

dásus, “a sage,” and the Gr. δά-ημι, δι-δά-σκω, &c., are probably derivatives from the same root dá, which, with the sense of “knowing,” however, has been lost to the Sanskrit. See hereafter under the head adáná.

2note page 68 There would appear from this passago to have been some distinct source, different from Ormazd, from whence “lies” darauga, were supposed to have had their origin; but it can hardly have been the spirit of evil, for it was friendly to Darius. The name which commences with Di - - - is unfortunately mutilated.

3note page 68 I may add, that to the early Greeks, Herodotus, Xenophon, &c., Persian, dualism was evidently unknown. Ormazd is the Ζεὺς or Ζέγιστος of those authors, who was the prime object of worship.

1note page 69 The name of Ormazd, does not, I believe, occur in any native Babylonian monument.

2note page 69 I take the Parthian form ![]() from the inscription of Nakhsh-i-Rustam, copied by Flower, or Chardin, in 1667, when the writing was in a more perfect state of preservation than at the time of Niebuhr's visit.

from the inscription of Nakhsh-i-Rustam, copied by Flower, or Chardin, in 1667, when the writing was in a more perfect state of preservation than at the time of Niebuhr's visit.

3note page 69 See De Sacy's Ant. de la Perse, pp. 107 and 249. I cannot hero enter into any detail on the Median and Babylonian alphabetical systems, but I will state that the letter ![]() in both languages is a nasal, perhaps approaching the Zend

in both languages is a nasal, perhaps approaching the Zend ![]() ; and that with the pronunciation of añ or aña, it signifies “a God,” being, in fact, the samo as the Arab.

; and that with the pronunciation of añ or aña, it signifies “a God,” being, in fact, the samo as the Arab. ![]() Allah.

Allah.

4note page 69 See the Zeitschrift, p. 511, and the reference which is there given to Cole-brooke's Gram., p. 49. Bopp, in his Comp. Grammar, hardly notices this declension, but refers to his Gram. Crit., s. 130.

1note page 70 Burnouf has carefully examined the respective formations of the Zend nom. and gen. in his Comment sur la Yaçna, p. 77.

2note page 70 The á is preserved in these terms in Sanskrit, as the case-endings do not commence with vowels, but are the simple consonants s and m.

1note page 71 The terminal elongation in Auramazdáhá is peculiar to Persepolis, and is evidently a corrupted form of the true case-ending. Dá-as, in fact, must have become dá(h)a before it could be lengthened to dáhá, for the principle of elongation depends upon the a being a terminal letter.

2note page 71 Lasscn supposes an anomalous dativo in Auramazdáiya, but that term is certainly an error of the engraver for Auramazdámaiya. It occurs in Ins. No. 6, 1. 50, p. 308.

1note page 72 Bopp has thoroughly examined this suffix in his Comp. Gr., vol. I., p. 386, 73 &c., and he has shown the thematic identity of ἔνθα, ![]() idha, and

idha, and ![]() iha, in sect. 373 of the same work.

iha, in sect. 373 of the same work.

1note page 73 Am is a general termination for pronouns; comp. aham, twam, vayam, yúyam, &c.

2note page 73 Bopp observes, that the a base is often phonetically lengthened to e in Sans., as in cbhis, ebhyas, eshám, eshu, and that ayam, therefore, may come immediately from e+am. Sco Comp. Gr., s.366, vol. II.; p. 515.