Introduction

In current Paraguay, certain traditional and folkloric ‘popular’ musical styles (música popular), such as the Paraguayan polca and the guarania,Footnote 1 as well as two ‘iconic’ instruments, the guitar and the harp, evoke and reflect Paraguayan identity, often referred to as paraguayidad (Paraguayanness). Paraguayidad is closely interlinked with nationalism following the proclamation of independence from Spain in 1811 and the subsequent nation-building projects of the various Paraguayan governments during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. During my fieldwork experience in Paraguay and throughout my past and current interactions with Paraguayans, I found that paraguayidad shapes people’s consciousness in their everyday lives and provides many Paraguayans with an imagined shared sense of community and belonging, memory and heritage. This is not surprising, since paraguayidad was actively constructed and reinforced through the state’s creation and promotion of local ‘popular’ traditions, including religious festivities, folk music, folk dances, crafts and food, which still today represent and evoke tangible elements of national identity. Moreover, nationalism continues to dominate the historiography which has, for at least the past century, narrated and constructed the myth of Paraguayan desconocimiento (unknownness),Footnote 2 and Paraguayan linguistic, cultural, geographical and historical excepcionalidad (exceptionalism).Footnote 3 Continued Paraguayan nationalism combined with the belief in Paraguayan exceptionalism and the notion of Paraguay’s ‘exoticness’ and disconnection from the region more broadly continue to dominate the regional historiography and social science literature.

To most Paraguayans, certain musical genres, instruments and musical characteristics reflect Paraguayan national identity most directly: the polca paraguaya and the guarania; the diatonic harp in performances of Paraguayan traditional and popular (folkloric) music (known as música popular); the use of the Paraguayan polka rhythm in 6/8 (ritmo paraguayo); the combination of harp and guitar; and the use of Guaraní and Jopará (a mixture of Spanish and Guaraní) lyrics. All these musical genres, instruments and characteristics embed a series of aural signifiers through which many Paraguayans today articulate a shared sense of identity as inherently linked to the nation of Paraguay. Besides the continuation of local ‘popular’ traditions in contemporary Paraguay and their constructed significance for expressing paraguayidad, I found through interviews and interaction with local performers that other musical styles and instruments too, including classical and rock music along with the guitar, are platforms for the articulation of national distinctiveness. Moreover, some rock music is used to reflect a certain political stance in opposition to mainstream societal values, while classical art music serves as a symbol of taste and for particular social groups to distinguish themselves from other, lower-status social groups. In other words, music reflects the hierarchical divisions of society, or its patterns of social stratification. Music reflects and shapes the structural conditions that underpin social relationships in Paraguay today, and is an important signifier of class-based ‘imagined community’ at local, translocal and affective levels.Footnote 4

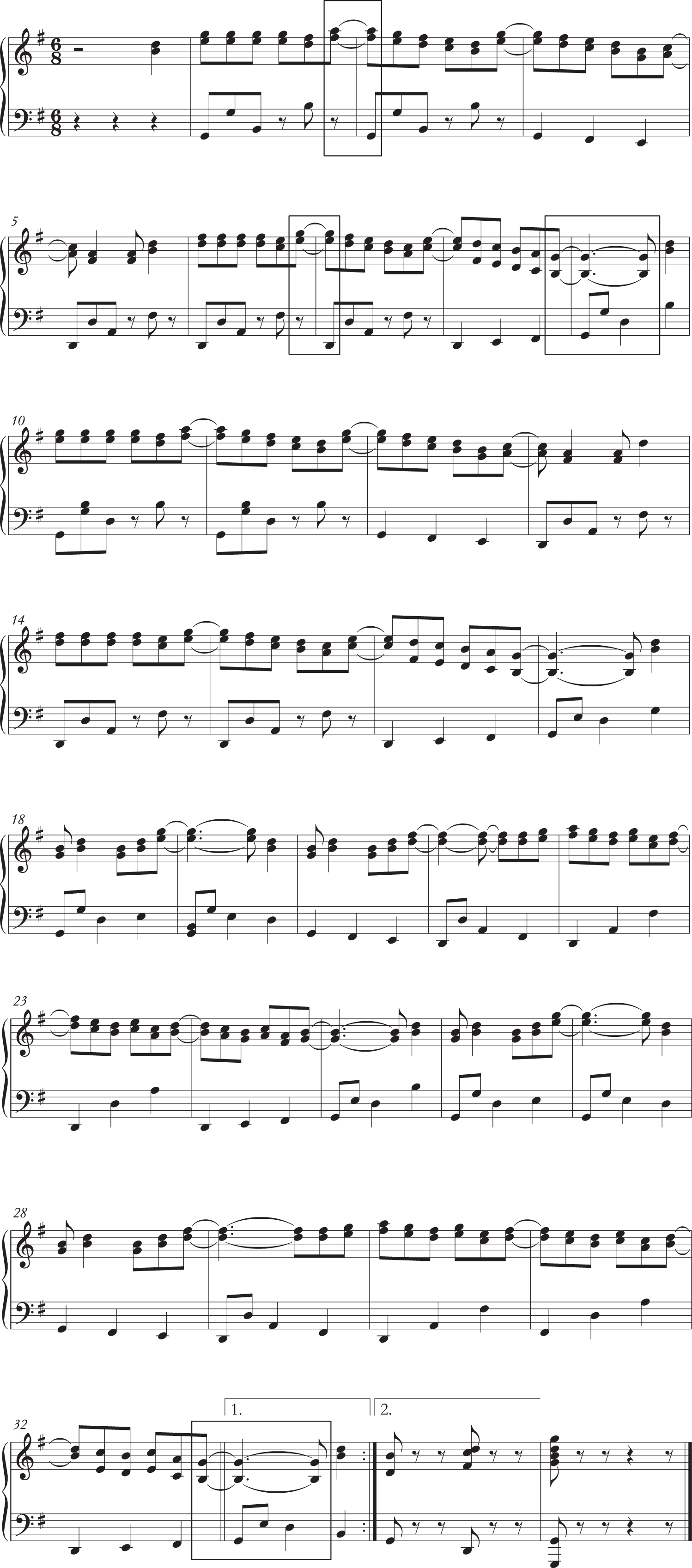

Paraguayan identity is thus more encompassing than paraguayidad, and the purpose of this article is to illustrate the way in which music operates in creating, constructing, articulating, negotiating and reflecting Paraguayan identity as it is informed by nationalism and by racial and class-based beliefs and perspectives. Illuminating the ways in which Paraguayan identity is expressed in and through music, I take contemporary guitar music recordings that commemorate the work of Agustín Barrios Mangoré (1885–1944) as a starting point in order to explore Paraguayan national, racial and class identity, specifically within the context of guitar music culture, spanning genres and styles from traditional and folkloric to art and popular music. Specifically, Rolando Chaparro’s rock fusion album Bohemio (2011), which contains rock arrangements of musical compositions by Barrios, helps to show the various ways in which Paraguayan identity is reflected in its various expressions, including national identity (via the inclusion of Barrios’s nationalistic pieces), ethnic identity (constructed as Guaraní) and class identity in contemporary Paraguay.Footnote 5 Chaparro’s album thus serves as an analytical lens through which to understand contemporary identity expressions in Paraguay. This article has grown out of my ethnographic fieldwork and continuing engagement with Paraguayan music, while featuring anecdotal evidence based on personal observations and informal interviewing, alongside musical and semiotic analyses.

This article opens with an extensive review of existing academic debates on music and identity generally, and on music and identity in Paraguay more specifically, in order to provide appropriate contextualization, as well as to address Timothy Rice’s critique of a general lack of critical engagement with literature on identity in ethnomusicology, whose scholars ‘seem to take for granted identity as a category of social life and of social analysis’.Footnote 6 The literature review thus contributes towards an understanding of the way in which identity is defined and discussed more generally in the social sciences and humanities, and builds on the publications of those who have written on this theme before. Secondly, the article introduces my ethnographic research, explores the way in which nationalism and paraguayidad are expressed in what I term here folkloric ‘popular’ musics (música popular) and goes on to discuss the role played by the concept of raza guaraní (a widespread belief in a common ancestry based on Spanish and Guaraní ethnic identity) in the construction, maintenance and expression of national and nationalist identity. In the final section, the article explores the Barrios revival in the early 2000s, and the role that that has played in people’s class consciousness, before presenting its general conclusions.

Music and identity: a review of literature

It is widely accepted today that music is a primary means for people in cultures around the world to construct, express and transmit their identity, along with their cultural and societal values, belief systems, norms and behaviours. In music sociology, anthropology, ethnomusicology and popular-music studies, the role played by music in the formation and articulation of identity has been conceptualized in at least two ways.

Social individual and collective identities

First, identity came to be regarded as a psychosocial category of analysis functioning at the individual (self-identity) and societal (group) levels, the latter focus having dominated music studies since the nineteenth century. This focus may have been shaped by the symbolic interactionist perspective, which regards meaning in music as a social product that emerges from interactions between people. People are social actors in the co-creation of collective meaning, including musical meaning. Music sociologists, anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, popular-music scholars and practitioners of other branches of musicology are therefore interested in people’s beliefs and thoughts about the world, on the basis that meanings are the result of the process of communicative interaction between people.

The specific term ‘identity’ has only recently emerged in public parlance and is generally attributed to the psychologist Erik Erikson’s work in the 1950s on psychological development.Footnote 7 Prior to this work, sociologists and anthropologists used other words to represent what would now be called identity to describe an expanding range of social and cultural concerns. For example, several foundational social scientists, including Max Weber and Theodor Adorno, were guided by a ‘grand’ focus on music as a mirror or reflector of social structure. Owing to art’s privileged position in both society and early academia, most of this early work was preoccupied with Western art music. Weber, for instance, analysed art music’s functional tonality as an expression of rationality in modern Western societies. Meanwhile, in the USA, early twentieth-century sociologists from the Chicago School focused on music as a by-product of broader analyses, including several early ethnographic studies of dance halls and musical careers within broader studies of labour and urbanization, while others examined the 1950s recording industry and audience patterns within larger studies of mass culture, youth and deviance.Footnote 8 The American sociologist John H. Mueller contributed a major work on the American symphony orchestra.Footnote 9

The 1950s and 60s witnessed significant cultural and intellectual shifts in Western societies, with consequences for the academic study of music, notably in the development of sociological and social-anthropological perspectives and concerns. For instance, the emergence of ethnomusicology in US academia in the 1950s advocated the inclusion of traditional music in the academic study of music, followed in the 1960s and 70s by jazz, rock, folk and popular music as legitimate objects of academic study, which challenged the exclusivity of art music that had dominated the academic study of music since the nineteenth century. Meanwhile, British cultural studies (particularly the work of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham) and its concern with subcultures, leisure and music’s meanings for audiences became influential in British music sociology, anthropology, ethnomusicology, popular-music studies, new musicology and other disciplines with a focus on music. During the 1980s, music disciplines moved away from the ‘grand’ focus on music as a mirror of social structure and became increasingly concerned with how music is socially shaped, and how its production, distribution and consumption is mediated by the contexts in which these activities take place. Ethnography, interviewing and people-focused interactions became established research methods in the attempt to understand music’s role in social life, as is evident in the social anthropologist Ruth Finnegan’s account in The Hidden Musicians and in Sara Cohen’s study Rock Culture in Liverpool; in the sociologist Deena Weinstein’s Heavy Metal;Footnote 10 and in ethnomusicological writings of the time.Footnote 11 Consequently, the boundaries between music sociology, social anthropology, ethnomusicology, popular-music studies, cultural studies, feminism and some forms of musicology became increasingly blurred.

Intensive globalizing trends worldwide have supposedly led towards a more classless society, yet musical taste and preference still often indicate people’s social identity and status. Indeed, the early work of Max Weber and Thorstein Veblen, while looking at the bifurcation of fine art and popular culture in the nineteenth century, developed a view that ranked status groups in terms of their appreciation of the arts and letters, their clothing style, their language and their leisure pursuits, while noting a close association with income, occupation and schooling.Footnote 12 This perspective has shaped subsequent studies (notably Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital) that regarded fine art as a marker of class position, while showing the way in which arts appreciation and other cultural indicators are used as a means to express and maintain the status hierarchy. An important strand within music studies of identity, including studies of musical taste and its role in the construction of social differences and social exclusion, thus began to focus on music’s link to status; notable examples include William Weber’s Music and the Middle Class, Bourdieu’s monumental study Distinction, which reflects the way in which music can serve negative and exclusionary politics, and Paul DiMaggio’s work on the musical canon in nineteenth-century America.Footnote 13 Examining the relationship between social (for example, class) identity and musical taste, Bourdieu argues that correlations exist between ‘high culture’ and a taste for art music, and that individuals of high social status tend to use displays of their musical taste – through ‘cultural capital’ – to distinguish themselves from those of lower social status. In other words, cultural capital is most closely associated with ideas of quality, refinement and authority, and is indicative of a high level of class status. Studies of ‘univore taste’ cultures defined by class were challenged by US-based sociologists, notably Timothy Dowd, who instead argued that high-status individuals also distinguish themselves through their omnivorous tastes (for example, their enjoyment of a wider variety of musics).Footnote 14

Beyond studies of taste and exclusion, music studies have explored value and talent in music, their articulations and the link between status and musical ‘politics’ (for example, musical value and talent as socially shaped), with notable studies including Henry Kingsbury’s ethnographic analysis Music, Talent and Performance and Tia DeNora’s Beethoven and the Construction of Genius. Footnote 15 Hierarchies of talent and articulations of musical value have further opened up discussions on the connections between music and identity/differentiation, studying the way in which music helps to shape identity, social action and subjectivity. A growing interest in the study of music as the basis for the formation of social identities emerged out of earlier studies from the 1960s and 70s, but now with a more explicit character, including for instance studies on popular music and on gender and sexed identities. Fundamental to this intellectual interest is the work of Simon Frith, who argued that popular music serves as both a strong source of identity for individuals within society and a powerful force in forming collective cultural and group identities, through which individuals draw sustenance in constructing a sense of self.Footnote 16 Frith, like Adorno, focused on aesthetic judgment, but rather than making those judgments he focused on their understanding. Paul Willis’s classic ethnographic study Profane Culture, for instance, had described a group of young men, the Bikeboys, in terms of how they used music both to articulate their self-notion and as a catalyst for action.Footnote 17 Meanwhile, Ellen Koskoff’s edited volume Women and Music in Cross-Cultural Perspective, Susan McClary’s Feminine Endings and Sheila Whiteley’s Women and Popular Music adopted a feminist perspective on the gendered provenance of music.Footnote 18 By the 1990s, the boundaries between ethnomusicology, social anthropology, music sociology and popular-music studies had become even further blurred, with a growing shared interest in issues surrounding ethnicity, difference, identity and globalization, including an interest in the concept of ‘place’ in the study of music, with Martin Stokes’s edited volume Ethnicity, Identity and Music providing another landmark publication on the broader theme of music and identity.Footnote 19

More recently, DeNora’s Music in Everyday Life, which focuses on music’s mediating role in relation to social action and experience, has helped us to understand how links between music and social life/social experience are forged.Footnote 20 Music helps people to experience socially constructed modes of subjectivity, and this has been the overarching focus in related studies on music and emotion, including Emilie Gomart and Antoine Hennion’s study of the love for music and drug-taking and DeNora’s aforementioned study of music’s role in the daily lives of American and British women as they use music to regulate, enhance and change qualities and levels of emotion.Footnote 21 Other important studies, such as Weinstein’s Heavy Metal (see above, note 10) and Sarah Thornton’s Club Cultures,Footnote 22 have focused on music and identity in relation to genres and subcultures, which reflect the key concern with identity politics and the link between music and social status. More recent developments are marked by even more rigorous accounts of musical meanings and social identities, while Georgina Born’s edited volume Music, Sound and Space has made an important recent contribution that bridges musical identity, meaning and interaction, and is both deeply social and deeply musical.Footnote 23

Identity as essential or constructed

A second way in which the role played by music in the formation and articulation of identity has been conceptualized in music sociology, anthropology, ethnomusicology and popular-music studies is by identity being understood as essential or constructed. The essentialist position grew out of nineteenth-century biological determinism, which explained human behaviour through stable and durable, innate and biological human characteristics, such as sex and race. As explained above, one key theme explored by early music sociologists assumed that all human thought and action is socially constituted, and hence that music’s structures and sounds are of social significance. In other words, music’s meanings are themselves socially constituted. The work of early sociologists thus asked questions as to whether music mirrors or reflects social structures. Informed by the seminal work of the German sociologist and philosopher Adorno, who sought to show that aspects of society are embedded within musical structures, subsequent studies similarly explored the way in which musical form and structure (for example, harmony, themes, tonality, structure, timbre, instrumentation and performance) encode, for instance, ‘male hegemony’.Footnote 24 These studies were based on the central idea that the character of social or cultural formations could find expression through musical structures and sounds. Yet this work has seen considerable criticism for its tendency towards essentialism, assuming that all people of a particular gender (or class or ethnicity) are perceived to be the same or ought to be the same.

Essentialism also influenced the identity politics of nationalism. With its roots in the romantic nationalism of Hegel and his contemporaries, national identity came to be understood as a nation’s character or distinct genius, in which music played an important role. While in many continuing practices of nationalist discourses music is still often regarded as reflexive, symbolic and expressive of such a stable and durable, unitary identity of the nation, from the 1980s onwards the concept of the nation was opened up to refer to a symbolic construct of ‘imagined communities’ with ‘invented traditions’ of (often folkloric) rituals, symbols and practices.Footnote 25 Key literatures in the latter camp include Philip Bohlman’s Music, Nationalism, and the Making of the New Europe, which regards nationalism, including ‘national’ and ‘nationalistic’ identities, as the key to understanding European music; and, in the specific context of Paraguay, Alfredo Colman’s The Paraguayan Harp, which explores harp music – via analyses of the instrument, the popular repertoire with which it is associated and the techniques employed in playing it – as the heart of Paraguayan national identity and illustrates that the harp is one of Paraguay’s national emblems.Footnote 26

The constructivist position gained momentum from the 1970s, influenced by the 1960s feminist and anti-racist movements and the introduction of identity politics based on race, ethnicity and gender at American universities and elsewhere, followed by 1990s discourses surrounding fragmentation and deterritorialization as a consequence of globalization, postcolonialism, transnationalism and the formation of diaspora. Regarding identity as unstable, learnt and thus changeable owing to socialization, constructivist thinkers ask questions about the link between identity, agency and power, domination and subordination, and resistance and opposition to the powerful positions from subaltern ones defined by class, race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, age, disability and so forth.Footnote 27 Music sociologists, anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, popular-music scholars and others have since examined the ‘hybridity’ of identities and movement between multiple identities, as these are beset with contradiction, fluidity and contestation. Thus, the constructivist position also posits that individuals have multiple and fragmented identities, while music is understood to participate in the social construction of these changeable and fragmented identities, with studies usually falling into two camps, one focusing on the way in which music reflects social identities, the other studying the way in which music actually helps to construct social identities.

Music and national identity in Paraguay

This article is underpinned by the constructivist position to explore the way in which music is an expression and reflection of collective Paraguayan national identity as it is informed by nationalism and racial and class-based beliefs and perspectives, spanning music genres and styles from traditional and folklore to art and popular music. In general, literature on the music of Paraguay is in short supply. There exist numerous titles, published exclusively in Spanish and often printed as limited editions, surveying Paraguay’s musical landscape from musicological or historical perspectives. These include the writings of Juan Max Boettner, Florentín Giménez, Bartomeu Melià and Sergio Cáceres Mercado, Diego Sánchez Haase, Luis Szarán and Rafael Eladio Velázquez;Footnote 28 the proceedings of a 2019 symposium edited by the Secretaría Nacional de Cultura;Footnote 29 more generic titles about Paraguayan culture and history;Footnote 30 and studies of notable individuals in Paraguayan music, including José Asunción Flores (1904–72) and Cayo Sila Godoy (1919–2014).Footnote 31 In the English language, there exist shorter chapters or encyclopaedia articles similarly providing general overviews on Paraguayan music and musical instruments,Footnote 32 including the piano,Footnote 33 as well as selected writings on the Paraguayan harp.Footnote 34 Some writings relate specifically to the music of the Jesuits.Footnote 35 And more recently, Paraguayan music has been explored by documentary presenters including the SOAS academic and journalist Lucy Durán (on the harp and classical guitar), the television presenter David Attenborough (on cowboy music from the Misiones region) and the radio producer and presenter Betto Arcos.Footnote 36

Literature on the theme of music and identity in Paraguay is particularly scarce, being limited to Colman’s aforementioned research on the Paraguayan harp and cultural identity, Robert Wahl’s research on Barrios and musical identity,Footnote 37 and a few studies of Paraguayan identity, nationalism and paraguayidad more generally.Footnote 38 This article will address this lack of academic research, with specific focus on the way in which Paraguayan national, racial and class identity is actively reinforced through the classical guitarist and composer Agustín Barrios Mangoré, whose music has been resurrected and revived during three waves as a major contribution to the national cultural heritage of Paraguay: in the 1950s with the commissioned collections of his works by Cayo Sila Godoy; in the 1970s with John Williams’s recording of the 1977 LP John Williams Plays Music of Agustín Barrios Mangoré;Footnote 39 and in the early 2000s, as will be shown below. There exist numerous Spanish-language publications on the life, works and musical ‘genius’ of Barrios,Footnote 40 while his achievements as a composer and a virtuoso guitarist have also led to the proliferation of English-language research and publications.Footnote 41 For example, the historian Carlos Salcedo Centurión, who has dedicated his life to researching Barrios’s history, published his vast collection of artefacts and facts in an impressive art book, and also directed, produced and wrote the only documentary ever produced on Barrios’s life, history and musical significance.Footnote 42

Yet none of the research to date connects Barrios to discussions on music and identity, even though ‘popular’ pieces of his such as ‘Danza paraguaya’ (based on the polca paraguaya) are hugely relevant to discussions concerning music and Paraguayan national identity. The polca paraguaya, along with the guarania, epitomizes the nationalist dimension of Paraguayan identity as an exemplar of the ‘typical’ Paraguayan musical folklore, born of the nationalist movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, that sought to construct and reinforce the sociocultural values associated with paraguayidad. Nationalist efforts also promoted the concept of raza guaraní as a signifier of an indigenous racial identity directly representative of the Guaraní people that came over time to serve as an ultimate expression of the Paraguayan national identity and nationalism which Barrios represented both musically and visually. Relevant literatures exist that explore Paraguay’s traditional folklore repertoire often, but not exclusively, within the context of an idealized (imagined) Guaraní culture,Footnote 43 yet none of these are concerned with identity construction. The celebratory treatment of Barrios’s classical repertoire reflects the widespread romanticized belief in Barrios as a ‘Paraguayan genius’ and a ‘lost national treasure’ in need of being collected, preserved and promoted worldwide, through which displays of class-based social status hierarchy are being achieved among certain social groups, a theme that has not yet been explored in the literatures on Paraguayan music.

First encounters with Paraguayan music

I first travelled to Paraguay in 2011, during the country’s bicentennial of independence from Spain, when I met the classical guitarist Luz María Bobadilla (b. 1963). At the time, she was in the process of recording and releasing (under the musical direction of the Paraguayan jazz guitarist and composer Carlos Schvartzman) the album Barrios Hoy: Luz María Bobadilla guitarra (2011), which pays tribute to Barrios.Footnote 44 The album was premièred as part of the official bicentennial celebrations on 9 May 2011 during a televised performance in the Teatro Municipal Ignacio A. Pane, Asunción,Footnote 45 which is, along with the Centro de Convenciones del Banco Central del Paraguay, the Club Centenario and the Centro Cultural de España Juan de Salazar, one of the main venues for the performance of classical music, including concerts and opera. The televised performance was attended by urban Paraguayans from higher-status groups, including politicians, professionals, guitar aficionados and others, who actively support or patronize the ‘high’ arts in Paraguay. The performers received standing ovations, particularly in tribute to Bobadilla for her contributions to Paraguay’s classical guitar culture for the duration of her career, which has spanned some 40 years.

I knew that Paraguay was inextricably linked to the classical guitar, and many Paraguayans take great pride in the world fame of Barrios. When I arrived in Paraguay, I found that his works and status were undergoing a massive revival, which in fact had already begun with commissioned collections of his works in the 1950s and continued with John Williams’s recording of 1977. From the 2000s, the Barrios revival proliferated through the performance practices of La Escuela de Mangoré (the School of Mangoré) under the direction of Cayo Sila Godoy, who is credited with the preservation of Barrios’s legacy, and it has continued in the work of Bobadilla, Berta Rojas and Felípe Sosa. There is also a growing younger generation of contemporary classical guitarists, notably Rodrigo Benítez, Diego Guzmán and Diego Solís, who specialize in the performance of Barrios’s classical guitar repertoire. Since the 2000s, the Barrios revival has been strengthened by growing interest in his musical heritage on the part of government officials, scholars, historians, patrons and guitar enthusiasts, as is evident in the vast proliferation of Barrios-themed musical and extramusical activities involving live and mediated guitar concerts and festivals in commemoration of him; recordings in different musical styles dedicated to his life and times; public displays and museum exhibitions; cultural tours to sites of relevant heritage; and scholarly and journalistic literature about his life and music.

This third wave of the Barrios revival saw an exciting increase in mediated performances via recordings based on his compositions and arranged in eclectic musical styles. For example, the album Bohemio – recorded by Rolando Chaparro, one of the best-known contemporary rock guitarists, singer-songwriters and bandleaders in Paraguay – pays tribute to Barrios, interpreted, however, in the style of rock-jazz fusion, based on 1980s ‘classical’ rock and characterized by melodic, harmonic and rhythmic alteration with jazz-induced influences. Chaparro and his band performed the music from the album live in his show Bohemio: Tributo a Mangoré (Bohemian: Tribute to Mangoré), held in the Cabildo Museum, Asunción, on 5 May 2012,Footnote 46 which attracted some Barrios aficionados along with the ‘typical’ crowd of younger, working-class rock-music fans. Rock music became popular in Paraguay during the 1960s as an underground movement influenced by American rock and the use of electronic instruments. This underground rock was targeted by the state, so a more Paraguayan rock paraguayo emerged ‘officially’ in 1980 with the band Pro Rock Ensemble. During the 1990s, and with the country’s transition to democracy, rock paraguayo enjoyed new opportunities, greater freedom to be performed in concerts and festivals, and new subgenres.Footnote 47 A distinct trend emerged among some rock bands to explore the roots of Paraguayan folk and traditional music, notably the polca paraguaya, guarania and songs in the Guaraní language. This continued to evolve into what is known today in Paraguay as experimental and fusion music (rock fusión), composed and performed by artists and bands like Chaparro, Dosis, La Secreta, Fauna Urbana and Made In Paraguay, who merged the 6/8 (compound triple) metre with hemiola features typical of Paraguayan folklore along with elements of jazz and other world-music ingredients in their fusion rock repertoire.

Music, nationalism and paraguayidad

Music serves as a cultural resource in the formulation and articulation of individual and collective identities in contemporary Paraguay, and provides an interesting, even powerful means through which to understand the constructed notion of Paraguayan national identity. Schvartzman, the director and arranger of Barrios Hoy, explained in a personal interview the particular challenges that arose during the album’s production, and commented on Barrios’s ‘La catedral’ performed by Bobadilla, the pianist Pierre Blanchard and a chamber orchestra. Schvartzman emphasized that the pianist had no experience of playing traditional Paraguayan music, such as the guarania, which posed a challenge for him:

Paraguayan music is pretty difficult because … it has a lot of rhythms or polyrhythm … You can think it is in 6/8, but you can also think in 3/4 … So there is a mix of 6/8 in the melody and 3/4 in the bass … which is the basis of Paraguayan music [and] is a feature that has to be present always in Paraguayan music.Footnote 48

We continued to talk about any similarities between the Mexican and the Paraguayan polca, but Schvartzman re-emphasized that traditional Paraguayan music, such as the Paraguayan polca, is ‘very unique!’

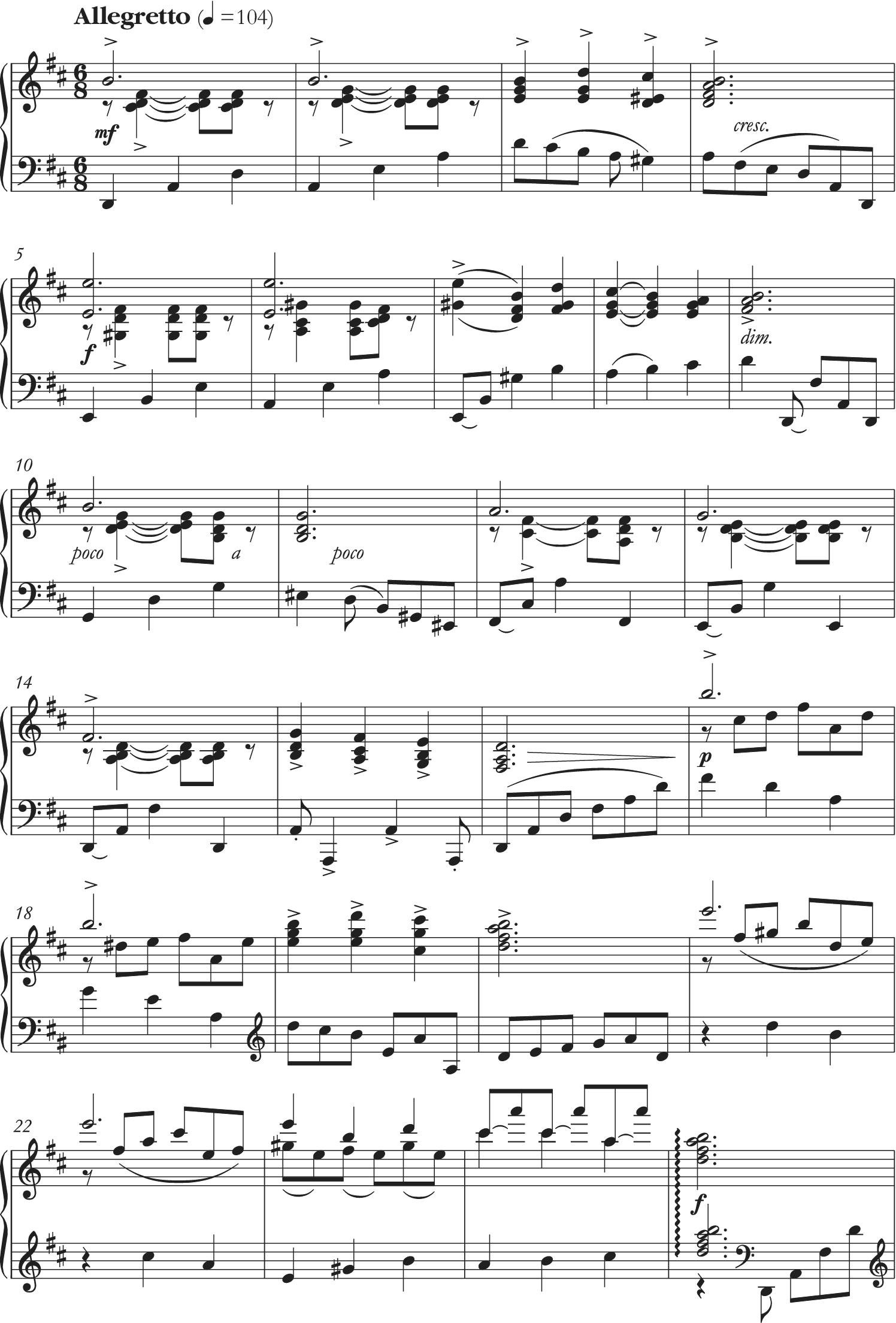

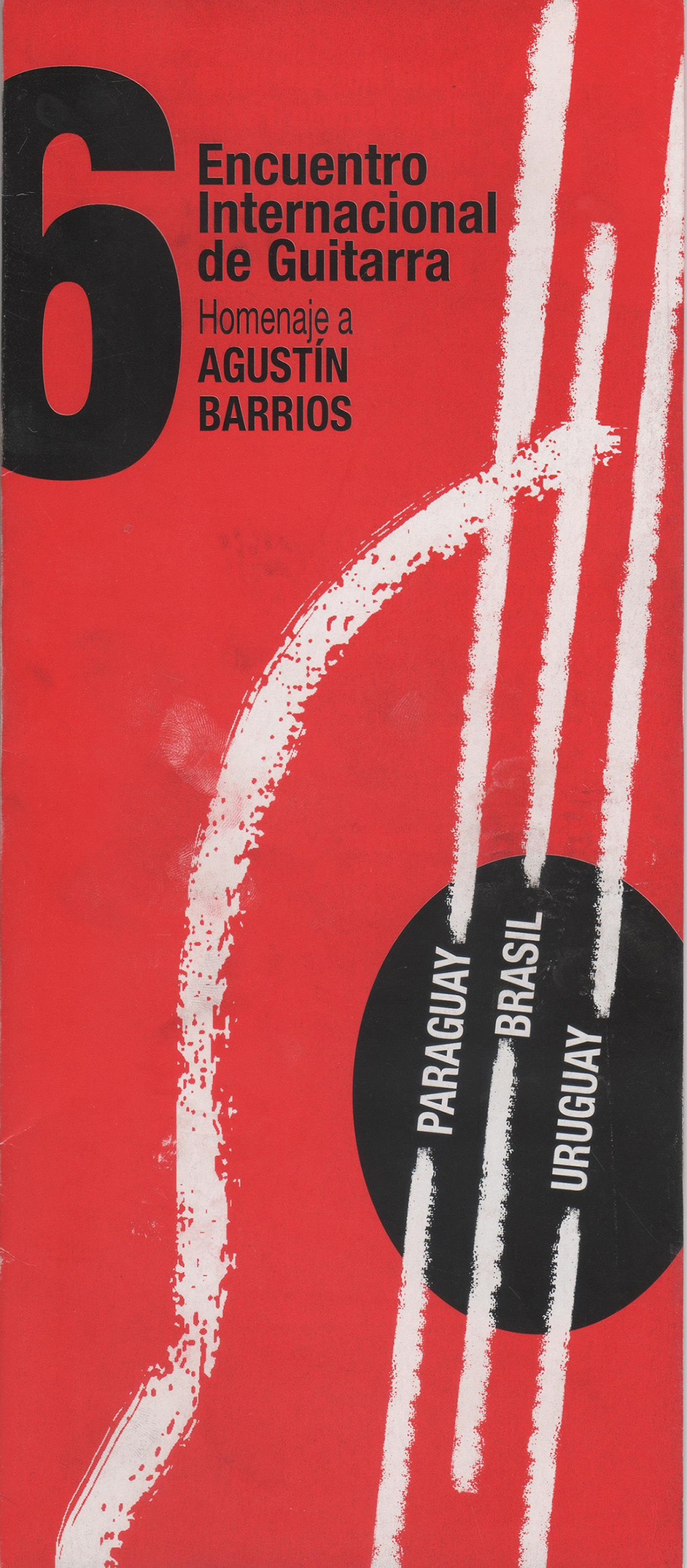

Like Schvartzman, several other musicians and non-musicians to whom I spoke expressed strong views surrounding the unique characteristics of folkloric ‘popular’ music, and frequently spoke about the polca paraguaya with its ‘typical’ 6/8 rhythm (which Schvartzman and others described as ritmo paraguayo). Indeed, I found the polca paraguaya to be ubiquitous in Paraguay, and most Paraguayans to whom I spoke regarded it, along with the guarania, to be the most ‘authentic’ expression of Paraguayan music.Footnote 49 For their 2011 album projects, both Bobadilla and Chaparro chose to include the polca paraguaya via an interpretation of Barrios’s ‘Danza paraguaya’ (1926; see Example 1; see also Appendix). The piece is structured in rondo form, ABACA – effectively a version of the two-section galopa extended by adding a third section (C) in the relative subdominant key.Footnote 50 It reflects many of the ‘typical’ characteristics of folkloric (‘popular’) music in Paraguay: it is in triple metreFootnote 51 and contains the sincopado paraguayo – use of syncopation in the melodic line placed on the last beat of a bar and the first beat of the following, which creates the impression that the melody is lagging behind the rhythmFootnote 52 – in the second section (B) in bars 17–32 and in the third section (C) in bars 53–6. The piece is based on a characteristically steady rhythm consisting of broken chords performed on the guitar, and features typical parallel thirds or sixths in the harmony, particularly in section B (at bars 21–4). The piece is structured in rondo form, ABACA –effectively a version of the two-section galopa extended by adding a third section (C) in the relative subdominant key. In terms of voice leading, the rich harmonic texture of Barrios’s composition utilizes four voices (a melody, a harmony, a middle line and a bass line), but at times there appear to be only three.Footnote 53

Example 1 Agustín Barrios Mangoré, ‘Danza paraguaya’, as edited in The Complete Works of Agustín Barrios Mangoré for Guitar, ed. Richard ‘Rico’ Stover (Pacific, MO: Mel Bay, 2003), 2 vols., i, 100–3.

Even though ‘Danza paraguaya’ is clearly composed and performed in the style of classical guitar music, Bobadilla, Chaparro, Schvartzman and several other musicians with whom I spoke described it as ‘popular’ Paraguayan music (música popular). This is confirmed by the fact that, notwithstanding its status as Paraguayan concert music, the piece has entered the canon of Paraguayan folkloric music (música popular paraguaya), as is demonstrated in Mauricio Cardozo Ocampo’s Mundo folklórico paraguayo and Carlos Lombardo’s Folklore guaraní – interpretación; see Examples 2 and 3.

Example 2 Opening of Barrios’s ‘Danza paraguaya’, as edited in Mundo folklórico paraguayo, ed. Mauricio Cardozo Ocampo, 3 vols. (Asunción: ATLAS Representaciones, 2005), ii, 253, where the piece occurs as a piano arrangement in 6/8 metre.

Example 3 Barrios’s ‘Danza paraguaya’, as edited in Carlos Lombardo’s Folklore guaraní – interpretación: Desquite de Guaranía (Asunción: El Lector, 1998), 107, where it occurs as a single-line melody in 6/8 metre.

So far, I have argued that folkloric (popular) Paraguayan music like the polca paraguaya collectively evokes in many Paraguayans a strong shared sense of paraguayidad. This shared sense is rooted in the state’s initiatives actively to construct Paraguayan national identity, reinforced by the official creation and promotion of so-called local ‘popular’ traditions (música popular), and exemplified in the ‘officialization’ of religious festivities, folk music, folk dances, crafts and food. Indeed, Paraguayan identity has been intimately connected with the construction of the Paraguayan nation since its independence from Spain in 1811 and has been shaped by Paraguay’s geographical isolation, its history of war and immigration, its bilingualism (Guaraní and Spanish) and its strong regard for geographical territory.Footnote 54 Folkloric (popular) music traditions became the primary means for constructing and expressing Paraguayan national identity, and this musical nationalism can be traced along three broad historical periods following Paraguay’s colonial period, beginning in 1811. It is important to note here that other histories of Paraguay exist, and that there is no intention here of retelling the country’s history. For instance, Colman highlighted to me that there exists ‘a highly complex web of Paraguayan “histories” and their explanation’ which presents Paraguay’s history according to five historical events or ‘historic moments’ of major significance: the colonial period (from the mid-sixteenth to the eighteenth century); the process of independence (1811); the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–70); the post-war and reconstruction period (1870–1900); and the Chaco War (1932–5).Footnote 55 The tripartite structure of my article aims to simplify such complexities and to bring some order into the development of nationalist music styles in Paraguay over the past two centuries, beginning with music and identity in the Nationalist Period (1814–70) and moving on to music and national identity in the Liberal Era (1904–40) and during Colorado Party rule (1940–89).

Music and identity during the Nationalist Period (1814–70)

After independence in 1811, the systematic construction of Paraguayan national identity was part of the political project of the governments of the dictator José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1766–1840; ruled 1814–40)Footnote 56 and President Carlos Antonio López (1792–1862; ruled 1840–62), as well as the latter’s successor and son, Francisco Solano López (1827–70; ruled 1862–70). The period 1814–70 is known as the Nationalist Period, and was marked by republican despotism, geographical isolationFootnote 57 and a perpetual post-colonial fear of Argentinian and Brazilian annexation. Paraguay was under continuous threat from other neighbouring countries in a succession of wars, notably the 1811 war against Argentina’s General Belgrano, the War of the Triple Alliance (1864/5–70) consisting of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay (which occupied Paraguay at the time),Footnote 58 and (during the Liberal Era) the Chaco War (1932–5) against the Bolivian invasion of disputed Chaco territory. Paraguay’s isolation had a huge cultural impact in shaping paraguayidad, creating a more inward-looking society and fostering a stronger sense of shared cultural norms and identity, intensified by the shared suffering and collective memory of war that further strengthened a sense of solidarity and difference.

During the nineteenth century, fashionable dances like the polka, gallop, waltz and mazurka became popular in Asunción: they were first introduced at receptions organized by Francisco Solano López’s lifelong companion Elisa Alicia Lynch (1835–86) and often performed at parties held at the National Club there.Footnote 59 Gradually, these dances were adopted and modified, and became incorporated into the repertoire of traditional folk dances of Paraguay.Footnote 60 An example is the aforementioned polca paraguaya (derived from the Bohemian polka), a rhythmically lively song and dance style in 6/8 metre featuring hemiola rhythmic patterns with juxtaposed groups of three notes in the bass against two in the melodyFootnote 61 and syncopation that may have been used to accompany the gato dance. Musically, short melodic phrases feature a typical syncopation on the last beat of one bar tied to the first of the next. Harmonically, the instrumental accompaniment utilizes parallel thirds or sixths and the so-called ‘Andalusian cadence’ (a minor descending tetrachord in conjunction with a VI–V–IV–III progression).Footnote 62 Characteristic of the lively polca is a steady rhythm consisting of broken chords performed on the harp or guitar. Numerous anonymous polcas survive from the nineteenth century, such as ‘El solito’ (see Example 4). When the polca is presented as vocal music (as opposed to instrumental music intended to accompany dancing), performances are usually slower and are referred to as polca canción (in Guaraní purahéi). These may be sung in Spanish, Guaraní or a mixture of the two, while (under descriptive onomatopoeic titles) making reference to romance, nature, towns, nostalgia, epic topics, political parties and football clubs. The history of wars also often informs the lyrics of the polca canción. There are many variants of the polca and there exist numerous disagreements as to their classification, so the term polca paraguaya often refers to Paraguayan music in general.Footnote 63

Example 4 ‘El solito’ (anon.), a Paraguayan dance (polca paraguaya) still frequently performed by conjuntos to accompany dancers in traditional costumes, as edited in Mundo folklórico paraguayo, ed. Mauricio Cardozo Ocampo, 3 vols. (Asunción: ATLAS Representaciones, 2005), i, 192. The boxed areas illustrate examples of ‘typical’ musical characteristics found in many polcas, including syncopation, parallel thirds and parallel sixths.

Other nationalist musical styles

A substyle of the polca paraguaya is the dance music termed galopa (deriving from the European gallop), which also uses a lively rhythm in 6/8 metre with hemiola rhythmic patterns, and is distinguished by its closer association with folk and traditional dancing to the accompaniment of a folk band (see above, note 50). While the polca consists of a single musical section, the galopa, as mentioned above, is divided into two, with the second half presenting significant rhythmic variations played by the percussionists as the music accompanies female galopa dancers. Another European-derived music style is the vals (also called the valseado paraguayo), which is characterized by short, repetitive melodic phrases; standard harmonic progressions (I–V–I–IV–I–V–I); and a steady triple metre. The ‘folkorized’ valseado showcases some distinctive features: the dancers’ foot movement alternates between side to side and back to centre, while guitar strumming (rasgueo) is used to accent the rhythm. The instrumental accompaniment is usually performed by harp and guitars.

Among the vocal styles to emerge during the nineteenth century are the rasguido doble (double strumming) and compuesto. The rasguido doble is a song style in simple duple metre, which derives from particular strumming patterns performed on the guitar (for example, a mixture of strumming techniques and slapping strings onto the fretboard with the fingernails of the right hand, thus creating a percussive snare-like sound in between rasguaedo strumsFootnote 64) and often emphasizes two golpes (strums) of semiquavers on the first half of the first beat. Otherwise, it shares the typical characteristics of folkloric music: tonal harmony; a melodic line enriched through parallel thirds or sixths; and short, syncopated melodic phrases. The compuesto is a storytelling style set either to the Paraguayan polca (in 6/8, compound duple metre) or the rasguido doble (in 2/4, simple duple metre). Two singers, who are accompanied by guitars, harp and accordion, as well as the rabel (spike fiddle, a form of ‘popular’ violin), perform descriptive balladry (usually by anonymous authors or poets) centred on a real dramatic, epic or tragic event (suceso), as well as on festive, humorous or religious topics. At times, it serves as satire to ridicule authorities, or alternatively as a means to extol politicians and military leaders. Usually structured in four-line verses (coplas) or ten-line verses (décimas), the ballads are sung in Guaraní or Jopará.

Music and national identity during the Liberal Era

During the early twentieth century, efforts were made by the Liberal Party (1904–40; formerly the Centro Democrático) to restore a sense of national pride, identity and direction to a nation devastated by the War of the Triple Alliance. The Nationalist Period was reinterpreted as the ‘golden age’ of independent development, progress and prosperity, led by the ‘father’ of the nation (Francia) and the ‘builder of the nation’ (López), and the War of the Triple Alliance was reconstructed as a heroic defence and glorious (even inevitable) defeat. The nationalist discourse also constructed the idea of raza guaraní, that is, the widespread belief in a common ancestry based on Spanish and Guaraní ethnic identity,Footnote 65 which rendered the Paraguayan nation unique and distinctive in terms not only of history, culture and land, but also of ‘racial’ identity. While the term itself suggests racial purity, it was used in the nationalist discourse to convey a sense of blended (mestizo) ancestry, which is not unique in the Latin American context.Footnote 66 Yet the foregrounding of the indigenous element in the hybrid social construction of the concept of raza guaraní is what is most unique in the Paraguayan case. I will return to the notion of raza guaraní below.

An important national tradition to emerge in 1925 was the guarania, created by the Paraguayan composer José Asunción Flores as an urban vocal and instrumental musical style on the basis of earlier experiments with the polca paraguaya. The guarania involved altering the tempo of the polca and slowing it down in order to facilitate a more accurate performance of the latter’s melodic accentuation and rhythmic syncopation. Originally composed as an instrumental musical style, the guarania was quickly adapted for vocal music, where it emphasized romance and nostalgic themes with a high degree of emotion. The significance of the guarania in Paraguayan identity resulted in its national recognition as an official Paraguayan musical genre when Flores’s composition ‘India’ (c. 1930) was adopted as the guarania nacional in 1944, and when his birthday (27 August) became established in 1994 as the Día Nacional de la Guarania. Other musicians and composers have embraced the guarania, which, with the development of the recording industry in the 1950s, spread both within and beyond Paraguay, where it was shaped by other Latin American musical styles.

Music and national identity during the Colorado Party era (1940–89)

The narrative of the Paraguayan nation that developed under the Liberal Party provided the subsequent ideological foundation of the Colorado Party (formerly the Asociación Nacional Republicana), which ruled between 1940 and 1989, notably under the three-decade dictatorship of General Alfredo Stroessner. Self-imposed isolation continued to be a recurrent theme adopted for political convenience by the Stroessner dictatorship.Footnote 67 Paraguay’s geographical and political isolation created a more inward-looking society while fostering a stronger sense of shared cultural norms and identity. The Colorado Party focused on formal education programmes to promote Guaraní grammar and Paraguayan history, to re-educate Paraguayans and to create the sentiment of an undivided nation where citizens adhere to the core values of the constitution – libertad, unión e igualdad (freedom, union and equality), values also expressed in the national anthem of Paraguay.Footnote 68 While Paraguay is a country of immigrants, Paraguayans are officially bilingual, Spanish being the language of the political and legal systems, the mass media and the public administration, while Guaraní is the preferred language of the majority of the population.Footnote 69 It was owing to the promotion of systematic instruction in and spoken use of the Guaraní language as part of nation-building from the 1920s until the 1970sFootnote 70 that Guaraní became ‘the language of the people’ and was constructed as a key defining characteristic of paraguayidad. Footnote 71

Paraguayan identity was also constructed and reinforced through the state’s creation and promotion of invented folkloric traditions exemplified by the propagation of religious festivities, folk music, folk dances, crafts and food. Colman, who experienced this period at first hand, explains:

Beginning in the late 1950s and until the mid-1980s, the state promoted artistic, musical, and popular expressions associated with paraguayidad. Among these ‘officialized’ expressions, the para-liturgical activities (dance, fair, food, games, music) connected especially to the festivities of San Blás (Saint Blas, Catholic patron saint of Paraguay) on February 3, Kuruzú Ara (the feast of the Cross) on May 6, San Juan (Saint John the Baptist) on June 21, and the Virgen de Caacupé (The Virgin Mary of Caacupé); and the choreographic productions offered by the newly created Ballet Folclórico Municipal (The Municipal Folkloric Ballet) and the folk music performances of the Banda Folclórica Municipal (The Municipal Folk Music Band), were of paramount significance in the construction and reinforcement of popular expressions. Paraguayans take such expressions to be long-standing cultural traditions […] [it] is crucial to recognize that this socio-constructed idea [paraguayidad], first inculcated by the state, has served as one of the main means of propagating invented traditions such as folk music festivals.Footnote 72

In the 1970s, the Paraguayan composer Oscar Nelson Safuán (1943–2007) invented a new hybrid music style termed avanzada in an effort to innovate Paraguayan traditional music (notably the galopa, guarania and polca paraguaya) while expanding the traditional harmonic language also to include augmented, diminished and dominant-seventh chords, and encouraging the inclusion of acoustic, electronic and percussion instruments. The avanzada combines the rhythmic patterns of the Paraguayan galopa with those of the guarania in a ratio of two bars to one: within one bar of the slow (compound duple) guarania are placed two bars of the fast (compound duple) galopa. The result is a hybrid rhythmic structure in compound duple metre.

This era in Paraguayan nationalism was instrumental in constructing the belief that Paraguayan identity is part of the essence of paraguayidad which refers to a shared set of beliefs and values shaped by an ideal historical past (the ‘golden age’), and it explains why still today most Paraguayans use the terms identity and paraguayidad interchangeably. Paraguayidad is a constructed belief in a shared national experience, shaped by Paraguay’s relative isolation, its historical memory of war and immigration, its strong regard for land/geographical territory (la tierra colorada) and its unique language, which resonates with the stark differences between wealth and poverty, land ownership and landlessness, privilege and inequality still evident in Paraguay.Footnote 73 This belief is still reflected in much traditional and folkloric music, which is often sung in Guaraní, Spanish or Jopará.

Today, a large body of folkloric traditions represents and evokes national tangible elements of paraguayidad, including ñandutí, a weaving tradition from the town of Itauguá (see Figure 1); chipá, a corn starch and cheese bread; tereré, a yerba mate cool drink; filigrana, silver jewellery from Luque; and Paraguayan folkloric music (música popular). In music, paraguayidad is expressed most directly in conjunto (ensemble) performances by harp and guitars (including the requinto guitar) and the accordion, using the Paraguayan polca rhythm (ritmo paraguayo), with singing in Guaraní and Jopará. While Paraguayans regard the polca paraguaya and guarania as the most ‘authentic’ folkloric expressions of paraguayidad, other styles like the aforementioned galopa, vals, rasguido doble, compuesto and avanzada have entered the canon of Paraguayan folklore.Footnote 74 Numerous conjuntos (ensembles playing música popular) have performed them both nationally and internationally, notably Luis Alberto del Paraná and his conjunto Los Paraguayos, who travelled extensively in Europe and South America and recorded some 80 albums, as well as other popular conjuntos such as Los Indios, Los Carios, Los Gómez and Los Mensajeros del Paraguay. These ‘invented’ folkloric traditions most directly evoke and reflect paraguayidad today.

Figure 1 Paraguayan ñandutí (a weaving tradition from the town of Itauguá) and other local crafts sold at the craft market in Asunción, 30 June 2011. © Simone Krüger Bridge.

Music, paraguayidad and raza guaraní

While paraguayidad and Paraguayan identity are intimately connected and have been related to the construction of the Paraguayan nation since the early nineteenth century, the nationalist discourse also constructed the idea of raza guaraní, a founding ‘myth’ of common ancestry and common ethnic community based on Spanish and Guaraní ethnic identity, which rendered the Paraguayan nation unique and distinctive in terms of race and ethnicity.Footnote 75 I found the belief in raza guaraní to be still widespread among Paraguayans today, both in Paraguay and in the diaspora. For example, in November 2018, at the invitation of Nuno Vinhas, the president of the Anglo-Paraguayan Society, I presented a talk at the Instituto Cervantes in London, which was attended predominantly by Paraguayans living in the south of the UK. To my surprise, in attendance was also the (former) ambassador and plenipotentiary of Paraguay, His Excellency Mr Miguel A. Solano-López Casco, who made a speech after my talk, stressing the point that raza guaraní is a fact, and that Paraguayans have indeed evolved from the creolization of Spanish men and Guaraní women. The speech felt very powerful, and Paraguayans in the audience agreed unanimously, so I wondered, ‘Who am I to define and somewhat judge their shared (even if constructed) belief?’

In the context of contemporary music, the rock guitarist Chaparro evokes this shared belief in racial and cultural identity directly by emphasizing the Guaraní elements of Barrios’s concert persona during 1930–4 on the album cover of Bohemio (see Figures 2 and 3), where the overlaid image in the centre shows Barrios as the sixteenth-century Guaraní warrior Mangoré. Barrios would enter the stage in full ‘Indian’ dress, including headdress with feathers, surrounded by palm leaves and bamboo to evoke ideas of ‘the jungle’. Concert advertisements depicted Barrios as the exotic figure of Chief Nitsuga MangoréFootnote 76 and described him as ‘the messenger of the Guaraní race […] the Paganini of the guitar from the jungles of Paraguay’.Footnote 77 As the figure of Mangoré, Barrios may also be regarded as expressing a strong sense of musical nationalism that aligned with the prevailing political movements towards independence from colonial Spain, and with it an assertion of the culture of the New World against the Old WorldFootnote 78 – yet it is important to stress that this is but one interpretation among others.Footnote 79

Figure 2 Album cover of Rolando Chaparro’s album Bohemio (2011), which pays tribute to the Paraguayan composer and guitarist Agustín Barrios Mangoré (1885–1944). © RCH Producciones. Reproduced by permission of Carlos Salcedo Centurión.

Figure 3 Image of Agustín Barrios Mangoré dressed as Chief Nitsuga Mangoré (c. 1933). Photograph provided by the Barrios historian Carlos Salcedo Centurión and reproduced by his permission.

By appearing in ‘native dress’ surrounded by jungle imagery as Chief Nitsuga Mangoré, Barrios used the concept of raza guaraní as a concert marketing strategy at a time when nationalist discourses continued to promote the belief that Paraguayans are ‘the result of the mix of Spanish and Guaraní, the enlightened European and the noble savage, the “warrior farmer” […] [which had] by the mid-1930s […] become part of the official government line’.Footnote 80 It is therefore perhaps not surprising that most Paraguayans today believe Guaraní culture and language to be the essence of paraguayidad.

While Chaparro clearly makes visual references to raza guaraní, he goes even further by including a musical reference to Guaraní and its imagined connection to indigenous culture by framing his rock fusion arrangement of the classical tremolo work ‘Una limosnita por el amor de Dios’ (‘Alms for the Love of God’; track 10 on the album Bohemio) with a field recording of children singing a nursery rhyme in Guaraní, which is faded in and out before and after the piece proper. This is significant, because Guaraní has become constructed as the ‘language of the indigenous people’,Footnote 81 even though indigenous peoples have suffered a long history of racism, maltreatment and inequality under Spanish colonialism. Indeed, racism and discrimination persist in Paraguay even today, and the constitutional rights of native groups have not been translated into legislative, administrative or other measures.Footnote 82 Chaparro uses this Guaraní musical expression to denote his radical stance in opposition to such mainstream societal values, which is embedded within the wider rock aesthetic that provides the backdrop to his expressions of political and social values. Indeed, many Paraguayans regard Chaparro as a representative of ‘the people’, a title which he received on account both of his socio-economic (working-class) background and of the political activism expressed through and in his music, including his varied musical collaborations with Guaraní and African artists and musical representations of the ‘other’ in Paraguayan society.Footnote 83

The Barrios revival and class consciousness

The decision made (separately) by Bobadilla and Chaparro to arrange and record the music of Barrios, rather than, for example, Flores, is significant, even though it takes on different meanings and significance in each case. While Bobadilla herself conceived the idea for her album Barrios Hoy (see Figure 4), in Chaparro’s case it was the Barrios historian Centurión who encouraged (and organized the funding for) him to arrange and record the Bohemio album as part of his sustained efforts to promote Barrios and his works worldwide. While Barrios may have been forgotten in Paraguay during his lifetime, his work has been the object of constant revival efforts since the 1950s which peaked during my research visit in 2011 during the bicentennial of independence. This continued interest in Barrios among certain members of Paraguay’s elite and middle-class groups reflects the strong class consciousness prevalent in contemporary Paraguay. Indeed, as I observed and confirmed through numerous interviews and casual conversations during and after my fieldwork experience, urban higher-status Paraguayans have always looked to Europe, and specifically to European ‘high’ art, for their perception of Paraguayan identity. This is clearly reflected in local revival efforts that continue to celebrate Barrios’s compositions, music recordings and elevated status as the ‘greatest guitarist-composer of all time’.Footnote 84 For example, during conversations with the Paraguayan singer and doctoral student in ethnomusicology Romy Martínez, I became aware that singing styles based on classical conventions are often more highly valued than popular singing in Paraguay, since preferences for classical music are associated with sophistication and refinement, which are in turn closely linked to the notion of belonging to a particular social class.

Figure 4 Album cover of Barrios Hoy: Luz María Bobadilla guitarra. © Luz María Bobadilla and Carlos Schvartzman, and reproduced by permission of Luz María Bobadilla and Carlos Schvartzman.

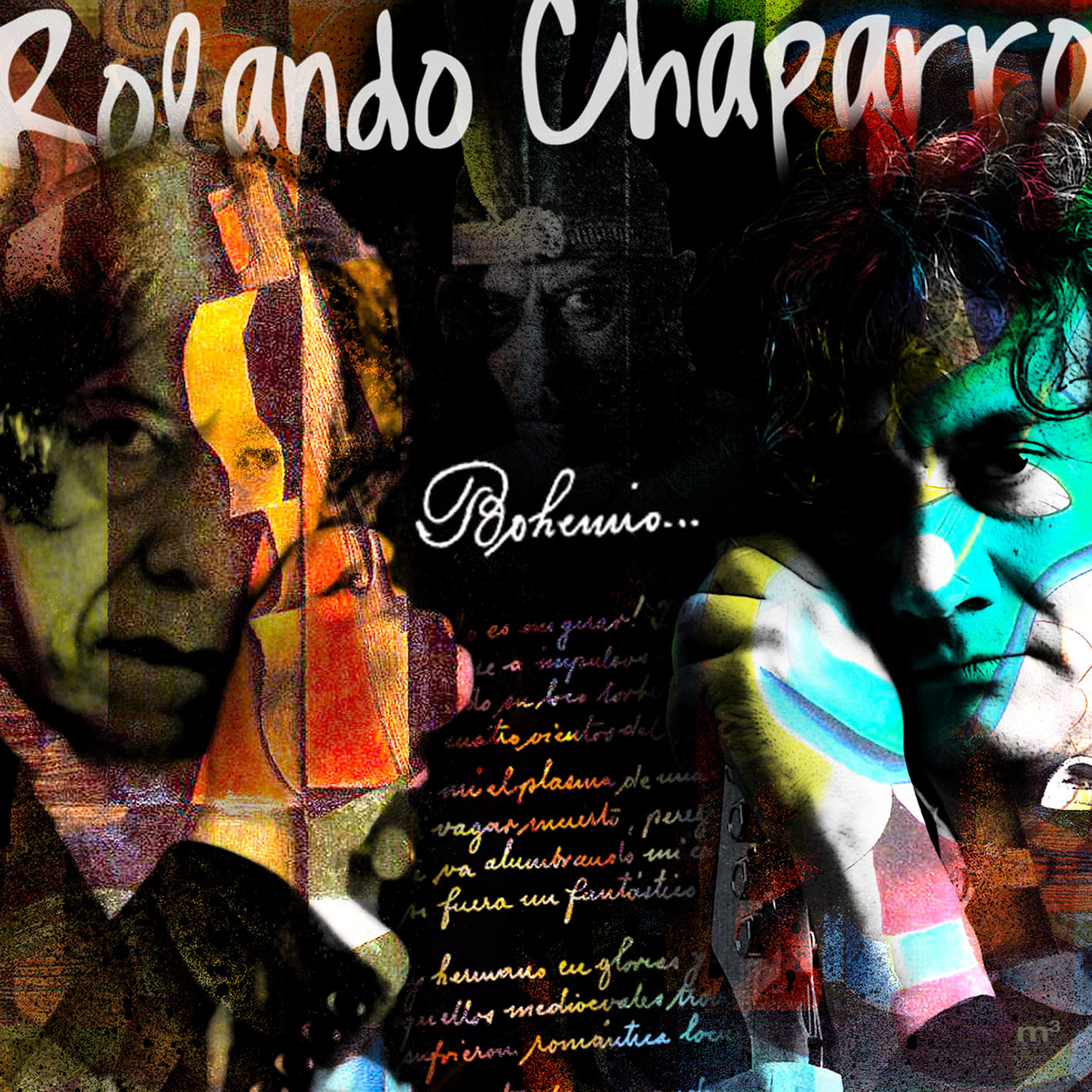

Barrios’s guitar compositions, however, are similarly adopted as a hallmark of the upper classes in Paraguay. For instance, I could not help but notice the vast proliferation of Barrios-themed musical and extramusical activities involving live and mediated guitar concerts and festivals in commemoration of him. Notable examples included the Paraguayan virtuoso guitarist Berta Rojas’s 2011 performance tour (Con Berta Rojas, hoy toca Mangoré) showcasing works by Barrios (see Figure 5); and the tribute of the International Guitar Festival (Encuentro Internacional de Guitarra) ‘Homenaje a Agustín Barrios’ held at the Centro Cultural de España (CCEJS) in Asunción, 13–15 July 2011, featuring guitarists from Paraguay (Diego Guzmán, Rodriguez Benítez), Uruguay and Brazil (see Figure 6).Footnote 85 There was also a wave of activity surrounding music recordings in different musical styles dedicated to the life and times of Barrios.

Figure 5 Outside cover of an educational/promotional pamphlet advertising the Paraguayan virtuoso guitarist Berta Rojas’s 2011 performance tour (Con Berta Rojas, hoy toca Mangoré) of works by Barrios, provided to author by Berta Rojas and reproduced by permission of Berta Rojas.

Figure 6 Front cover of pamphlet advertising the International Guitar Festival (Encuentro Internacional de Guitarra) in tribute to Barrios (‘Homenaje a Agustín Barrios’) held at the Centro Cultural de España (CCEJS) in Asunción, 13–15 July 2011, and provided to the concert audience.

The Barrios revival also proliferated by means of public displays and museum exhibitions, cultural tours to sites of relevant Barrios heritage, and scholarly and journalistic literature and publications on Barrios’s life and music. For instance, the Cabildo Museum in Asunción has since 2007 housed a major exhibition of Barrios’s original manuscripts, recordings, guitars, photographs and other artefacts within its larger exhibition on Paraguayan culture, while the Teatro de Municipal houses a smaller collection of original 78rpm recordings alongside publications and publicity material (see Figures 7–8).

Figure 7 Exhibition of Barrios’s original manuscripts, recordings, guitars, photographs and artefacts at the Cabildo Museum and Teatro de Municipal in Asunción. The guitar to the right is the instrument originally made in 1930 by the Spanish luthier Enrique Sanfeliú, which Barrios had decorated with his initials ABM (Agustín Barrios Mangoré) in 18ct gold. Photograph taken on 28 June 2011. © Simone Krüger Bridge.

Figure 8 Exhibition of Barrios’s original manuscripts, recordings, publications and publicity material at the Cabildo Museum and Teatro de Municipal in Asunción. Photograph taken on 28 June 2011. © Simone Krüger Bridge.

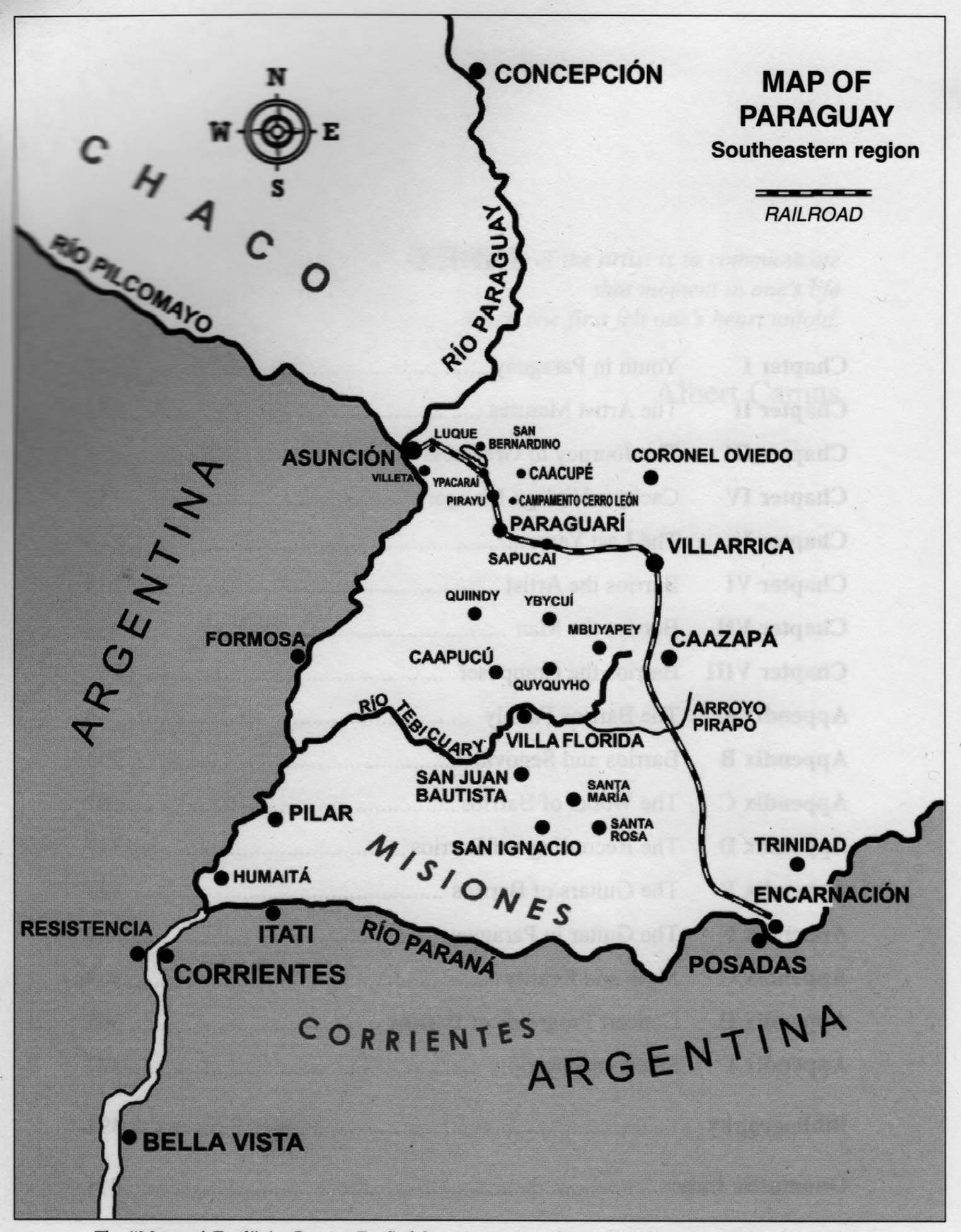

Meanwhile, the recently established ‘Ruta Mangoreana’ (Barrios Trail), conceived and promoted by the Asunción-based Guitars from the Heart Association and its affiliated research group, the Barrios Mangoré Project Centre, reveals the origins and movements of the Barrios family in and around Paraguay (see Figure 9). During my stay in Paraguay, I was invited by María Selva Corrales and Dalila Corrales Martino on a tour of San Juan Bautista, where the Barrios family home, Casona Mangoré, has been turned into a museum and a monument has been erected (see Figures 10–11); the neighbouring town Villa Florida, which is believed to be Barrios’s birthplace (although this is only one of at least two circulating theories) and where the Corrales family exhibit Barrios nostalgia in their private ranch house; San Bernardino, where the Hotel del Lago houses a ‘Barrios Room’ and other memorabilia and offers occasional guitar concerts by leading Barrios specialists like Bobadilla, Rojas, Sosa and other invited guests; the former Argentinian Consulate in Villa Florida, where Barrios’s father, José Doroteo Barrios Falcon, worked as a vice-consul; and other places of Barrios-inspired nostalgia. I also took the boat tour of the Rio Paraná with members of the Corrales family to visit the infamous place where Barrios would have crossed the river.

Figure 9 ‘La Ruta Mangoreana’ (Mangoré Trail). © Barrios Mangoré Project Centre and Guitars from the Heart Association. Reproduced by permission from Carlos Salcedo Centurión.

Figure 10 Casona Mangoré, the former Barrios family home in San Juan Bautista, Misiones. Photograph by author (14 August 2011). © Simone Krüger Bridge.

Figure 11 Barrios monument in San Juan Bautista, Misiones. Photograph by author (14 August 2011). © Simone Krüger Bridge.

Official efforts, meanwhile, were evident in 2009, 2010 and 2011, when the Paraguayan government of President Fernando Lugo Méndez (unsuccessfully) requested from El Salvador the repatriation of Barrios’s remains on the basis of his Paraguayan citizenship and national identity, reflecting the fact that Barrios is considered today as a major figure in the national cultural heritage of Paraguay.Footnote 86 This fact is further exemplified by a new 50,000 guaraníes note that came into circulation in 2011 (see Figure 12), depicting (on the front) an image of Barrios and (on the back) a classical guitar owned by him from 1918 with the words ‘Mangoré: popa su guaraní’ (‘Mangoré: fifty thousand guaraníes’) beneath, an example of which survives in the private collection of Renato Bellucci.Footnote 87 Noteworthy here are similar initiatives by the Paraguayan government in issuing commemorating postal stamps with Barrios’s image (one in 1985 and two in 1994), as well as a commemorating postmark in 2005.Footnote 88 Moreover, I could not help but notice the many commemorative posters in celebration of Paraguay’s bicentenary on lamp posts throughout Asunción depicting well-known and influential personalities in Paraguay’s history, including Francia, Benjamín Aceval, Carlos Frederico Reyes, Juan Bautista Rivarola and, not surprisingly, Barrios himself (see Figure 13). The year 2011 also saw the publication (in Spanish) of the revised, updated and greatly expanded biography of Barrios in Stover’s 1992 edition of Six Silver Moonbeams, commissioned by the Paraguayan government under Lugo Méndez and supported by Margarita Morselli (the director of Cabildo Museum) and the Barrios Mangoré Project Centre, notably its founder, the music historian Carlos Salcedo Centurión, who became a key informant during my stay in Paraguay.Footnote 89

Figure 12 The new 50,000 guaraníes note that came into circulation in 2011, depicting (on the front) an image of Barrios and (on the back) a classical guitar owned by him from 1918 with the words ‘Mangoré: popa su guaraní’. © Banco Central del Paraguay. Available at <https://www.bcp.gov.py/monedas-y-billetes-en-circulacion-i513> (accessed 15 January 2021) and reproduced for educational purposes.

Figure 13 Commemorative posters celebrating Paraguay’s bicentenary appeared on lamp posts throughout Asunción, depicting well-known and influential personalities in Paraguay’s history, including Barrios. Photograph by author (23 July 2011). © Simone Krüger Bridge.

The local newspapers seemed scattered with Barrios-related news about his life and work, while reinforcing the idea of the ‘artist as hero’ and the related concept of the ‘artist as genius’.Footnote 90 In terms of my own presence in Paraguay, I often found myself instantaneously tied up in the Barrios revival, as if by default my informants assumed that I had travelled to Paraguay because of Barrios. For instance, following an interview (organized by Centurión) with the journalist Nancy Duré Cáceres (from the national newspaper ABC Color) about my research into guitar music cultures in Paraguay, I was surprised to discover that the extended article that resulted centred heavily on Barrios (witness its title and the Barrios-related images that featured throughout), even though he was clearly not the sole focus of my research.Footnote 91

While the revival efforts clearly reinforce the widespread belief among urban middle-class and higher-status Paraguayans in Barrios as a ‘Paraguayan genius’ and a ‘lost national treasure’ that needs to be collected, preserved and promoted worldwide, they also reflect the relationship between class-based identity and musical taste. In the context of Paraguay, I observed a strong correlation between ‘high’ culture and a taste for ‘high’ art and classical music, and urban Paraguayans of higher social status tended to use displays of their musical taste to distinguish themselves from those of lower social status. There is indeed a huge gap there between the large lower-class population and the small wealthy group of Paraguayans. It was the latter group who patronized the Barrios revival, thereby displaying their taste in and preference for musical quality, refinement and authority, all indicative of a high-class status that has its roots in modern European societies, where the dominant musical expression is ‘serious’ art or classical music, reflecting the cultural preferences of the dominant social class of the bourgeoisie. Art music of the nineteenth century became seen as an expression of composers’ own personal feelings, which marked a deliberate move away from ideas that regarded so-called ‘primitive’ or ‘light’ (popular) music as an expression of collective experience.

The 2011 Barrios revival efforts driven by individuals from Paraguay’s elite and middle-class groups clearly reflect the idea that the only legitimate object of study is that of the classical art tradition, which renders other music, such as folkloric and popular styles, as being inadequate and inferior. I remember, for instance, a long conversation in July 2011 with the acclaimed pianist and composer Florentín Giménez (b. 1925) at his house in Asunción, to which I was invited by Colman, during which Giménez expressed strong views with regard to the lower status and value of folkloric ‘popular’ music as compared with classical art music. This shared understanding of musical value reflects a general, even if loose connection between socio-economic stratification and musical hierarchy, and, with it, links between music and value, taste and social class in Paraguay, which are actively reinforced through upbringing, education, music institutions and, indeed, music revival efforts.

Conclusions

Identity is a fruitful concept for the social and cultural analysis of music in contemporary Paraguay. To focus on identity is to acknowledge the central position which the concept occupies in contemporary debates in ethnomusicology, music sociology and popular-music studies. In ethnomusicology particularly, the concept of identity has been of paradigmatic significance and has informed the intellectual history of the discipline. It has ignited endless juxtapositions with case studies of traditional and, more recently, popular musics and is articulated in numerous studies of musical styles and traditions. Here, the term typically refers to the ways in which groups and individuals define and represent themselves – as members of nations and groups and as individuals – through the music they perform and value. Identity is thus not merely reflected in and through music but also shaped by the constitutive or transforming role of music. In other words, music both constructs new identities and continues to reflect existing ones. Aesthetic meaning in music is therefore understood as being situated within its wider social and cultural contexts, which this article has sought to understand through a focus on guitar culture in contemporary Paraguay.

It is within this context that this research is situated, illuminating the ways in which Paraguayan identity is expressed in and through music. Taking two contrasting albums that commemorate the work of Agustín Barrios as a starting point, this article explores Paraguayan national, racial and class identity, specifically within the context of guitar music culture, spanning music genres and styles from traditional and folkloric to art and popular music. Specifically, Chaparro’s rock fusion album Bohemio, which contains rock arrangements of musical compositions by Barrios, has served here as an analytical lens through which to understand the various ways in which Paraguayan identity – national, racial, class – is expressed. My research is also intended to make an indirect contribution to recent studies surrounding the cultural identity of musical instruments, as instruments themselves become markers or icons of cultural significance.Footnote 92 Although the harp is regarded as the national instrument of Paraguay, the guitar occupies a prominent role in all spheres of life and transcends musical genres and styles. Yet while the Barrios revivals have provided a tremendous boost to the study of the classical guitar in Paraguay and worldwide, the central role played by the guitar in other Paraguayan music still deserves concentrated scholarly attention.

In Paraguay, identity expressed in music assigns significance through national, racial and class dimensions. National identity is evoked by tapping into the official construct of the Paraguayan nation, which is actively reinforced through the figure of Barrios, whose music, as I have shown here, has been resurrected as a major contribution to the national cultural heritage of Paraguay. In terms of the music, two types of repertoire – música popular and Western classical music – exemplify this, but evoke identity in quite different ways. On the one hand, an understanding and appreciation of the musical complexity and significance of Barrios’s classical repertoire reflects a widespread romanticized and constructed belief in Barrios as a ‘Paraguayan genius’ and a ‘lost national treasure’ through which displays of social hierarchy are achieved. On the other hand, the significance of Barrios’s Paraguayan ‘popular’ pieces (such as ‘Danza paraguaya’) epitomize the cultural dimension of identity as an exemplar of ‘typical’ Paraguayan musical styles, as these were born out of and constructed during the nationalist movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Nationalist efforts to construct and reinforce the sociocultural values associated with paraguayidad also included the Guaraní ‘race’ as a signifier of an ethnic identity directly representative of the Guaraní people that came to serve over time as an ultimate expression of Paraguayan national identity. While nationalist discourses constructed the idea of raza guaraní, that is, the widespread belief in a common ancestry based on Spanish and Guaraní ethnic identity, Chaparro in particular tapped into this constructed and widely shared belief in powerful ways both musically and visually and within the rock aesthetic as an expression of political and social value in opposition to mainstream hegemonic values and ideology.

Yet besides their nationalist, racial and class-informed expression of Paraguayanness, both albums also add a further dimension to the expression of Paraguayan identity by way of musical hybridity and syncretism. The musical style of both albums is thoroughly eclectic, blending various ingredients – including classical music, música popular, Western rock and jazz – through which a more contemporary, globalized Paraguayanness is expressed and constructed, reflecting the recent impact of globalization mediated through mass communication. This has encouraged cultural interaction and worked to diminish national and ethnic boundaries. This eclectic musical style expresses an inclusive identity defined in terms of musical hybridity and collaboration, while also reflecting more complex globalized, transnational musical identity that extends beyond national boundaries and becomes entangled in the global circulation of people and musical practices.

APPENDIX

Original transcription of Agustín Barrios’s ‘Danza paraguaya’ (1926) in the Martín Borda and Pagola Collection, obtained in 1999 by Jorge Gross Brown from Aida Borda and Pagola de Pío Bano (daughter). This collection of original manuscripts consists of 28 works, the majority of which are by Barrios and dated to the 1920s. Photographed by the author on 5 July 2011 in Asunción, Paraguay. © Simone Krüger Bridge.