The early twentieth century saw a spectacular growth in the number of women's clubs in the United States.Footnote 1 In California alone, membership in the Federation of Women's Clubs had, by 1922, reached 531 clubs serving 55,624 members.Footnote 2 In San Francisco, the state's largest city before 1920, seventy-three clubs belonged to the Federation in June 1920, most meeting twice a month.Footnote 3

To a certain extent these clubs were successors to, and developments from, the long tradition of female salons, which even in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries had become far more than social or artistic gatherings. As Susan Branson has shown, many salons in the post-Revolutionary United States began to assume a political complexion. Attracting an elite class of educated women and hosted by prominent figures such as Anne Willing Bingham, these salons welcomed politicians of distinction, featured heated debates on the major issues of the day, and touted the concept of “virtuous citizenship” as a justification for female education and autonomy.Footnote 4 Through such political salons, Branson asserts, women functioned as a crucial part of the public discourse, complicating the widely accepted notion of gender-separated spheres.

Although many of the women's clubs of the early twentieth century grew out of this activist tradition, some of them began to adopt a new focus centered on women's professional aspirations. This new direction resulted in part from increased opportunities for women in higher education, which also provoked vociferous challenges from traditionalists. The University of California, for instance, opened as a coeducational institution in 1868, leading to questions about the usefulness of a university education for women. Expressing a common perspective of the time, a 1915 article in the New York Evening Sun justified the admission of female students on the basis of traditional gender roles: The state university (of California), noted the unidentified author, educates a “great number of girls … —thousands of them that are to be intelligent mothers of the future, able to direct their sons and use well the new powers that women are to possess.”Footnote 5

Institutions such as San Francisco's Century Club of California (CCC), the subject of the present article, combatted such sexism by reinforcing women's role in the intellectual and professional life of the community. This education-oriented club formed in 1888, at which time it initiated weekly programs for members on Wednesday afternoons from September through May. The presentations in the club's early years (some by members, but most by invited guests) not only spotlighted women who had attained prominence in fields previously closed off to them, but also served as a forum for female engagement in the wider public discourse. Music assumed an outsized role during the club's first decades, functioning in ways that went well beyond that of a cultural ornament enlivening the organization's wide-ranging disciplinary programming. In fact, in some years fully 50 percent of the club's presentations included some musical component (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of total Century Club of California programs from 1888 to 1920 that contained some musical component. (Data accumulated from the author's log of 915 programs.)

Certain legislative actions and judicial rulings in the post-Civil War period helped to boost women's professional ambitions and gradually increase their financial, employment, and property rights. As early as 1879, California embedded in its constitution a clause forbidding employment discrimination based on gender. Article 20, Section 18 of the 1879 constitution reads: “No person shall, on account of sex, be disqualified from entering upon or pursuing any lawful business, vocation, or profession.”Footnote 6 Not to overstate the case, however, women's rights remained severely curtailed by law. As but one of many examples, a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1908 (Muller v. Oregon) upheld limitations on women's working hours.

The seventy-three women's clubs active in San Francisco in the early twentieth century fall into three broad categories: benevolent clubs, subject-oriented organizations, and clubs offering wide-ranging and often loosely defined intellectual engagement. Benevolent institutions began to proliferate after the Civil War and facilitated women's entry into public life. In the area of health care, for example, women could approach politicians and businessmen “without jeopardizing their middle-class claims to gentility, domesticity, and femininity.”Footnote 7 Charitable organizations thus became conduits through which women could influence the distribution of local resources.Footnote 8 Some benevolent clubs included music within their purview. An example in San Francisco was the California Club of California; founded in 1897 to aid hospitals, female prisoners, and women in need, the club also maintained a chorus.

Subject-oriented clubs throughout the country included many devoted specifically to music.Footnote 9 The main one in San Francisco was the San Francisco Musical Club (founded in 1890), which featured solo and chamber music performances at its meetings.Footnote 10 It was one of three federated music clubs in Bay Area (the other two were not restricted to women).

The third category includes clubs with generalized intellectual goals, some of which included music, such as the Cap and Bells Club (founded in 1904) for “furthering the development of wit and humor; study of the drama, music, languages” or the Clionian Club (founded in 1897) for “studying history, including the art, literature, and music of Europe.”Footnote 11 Within this third category, the Century Club (which continues to meet on Wednesday afternoons to the present day) was not only the most prominent, but also the most expansive in its purview. Its founding purpose was generalized and far-reaching: “to secure the advantages arising from a free interchange of thought and from co-operation among women.”Footnote 12 The club achieved astonishing visibility on both the local and national levels. Prominent speakers at its meetings during the first quarter-century included Susan B. Anthony and the physician and minister Anna Howard Shaw (another prominent suffragist);Footnote 13 Stanford University's first president, David Starr Jordan (on five occasions);Footnote 14 architects Julia Morgan (who later designed William Randolph Hearst's castle at San Simeon) and Bernard Maybeck (designer of San Francisco's Palace of Fine Arts);Footnote 15 Sarah Cooper, founder of San Francisco's kindergarten movement; astronomer Dorothea Klumpke, who was the elder sister of composer and violinist Julia Klumpke; and photographer Arnold Genthe, known especially for his historic photos of pre-earthquake Chinatown.Footnote 16 Titles and dates of their presentations appear in the club's Annual Reports each year. The CCC was influential enough to attract politicians as speakers: for example, mayor and later senator James Phelan, and California governor William Stephens.Footnote 17 Receptions took place for many luminaries, including composer Amy Beach and stars of the Metropolitan Opera. The club even hosted a reception for President Woodrow Wilson.

If the Century Club's purpose was the interchange of ideas, why, we might ask, should music be included at all? Examination of the musical components included in the club's programs suggests three responses. In the most traditional sense, musical performance reinforced women's conventional role as the bearers of culture, widely viewed as a “civilizing force” that promoted ethical behavior. In a more progressive vein, CCC presentations frequently spotlighted women who had developed independent careers and achieved success in male-dominated fields—in music, most prominently in composition. Finally, at a practical level, the club provided opportunities for members to perform in a semi-public setting, helping them overcome a socially enculturated reticence. Mildred Wells offers an example of such self-restraint from the oldest women's club in continuous existence (founded in Jacksonville, Illinois in 1833): “Though these women set forth bravely to raise education funds,” writes Wells, “they did not depart from the custom of the time that women should not take part in any public performance. Therefore, the officers of the Society requested gentlemen of their community, frequently their own husbands and members of the Illinois College faculty, to read their reports on public occasions.”Footnote 18

A major focus of the Century Club in its early years was helping women gain confidence in speaking publicly and persuasively, and thus potentially becoming a powerful force in changing established gender models. “Under the club's kindly influence,” wrote president May Morrison (1858–1939) on the occasion of the club's tenth anniversary, “timidity of expression has constantly yielded to the acquired art of forceful speech, thus enabling Club members to stand their ground freely and frankly in discussion of measures which they may either favor or oppose.”Footnote 19 For women with musical training, public performance functioned as an analog to public speech. The club offered members an opportunity to break through centuries of convention that had discouraged, and at times proscribed, women's appearances on the stage. The CCC and other clubs provided an opportunity for women to conquer their engrained “timidity of expression” by appearing in front of a sympathetic audience.Footnote 20 Of course, we can cite many women throughout Western music history who transcended the censorious view of female public performance, but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most U.S. women still struggled to negotiate conflicting expectations: on the one hand, playing a subsidiary role to the men in their lives and projecting a demure public persona, while at the same time responding to the increasingly strong pull of full citizenship—both social and political. Whether through performance, lecture, or study, clubs such as the CCC offered a safe environment to combat conventional constraints.

Although the CCC convenes today in much the same format as in its early years, this essay focuses on the organization's first three decades, a period in which the club actively served educated women as a gateway into their changing society. My examination of the nearly 1,000 programs presented at the club's meetings between 1888 and 1920 revealed 254 that included music. I treat this large body of material in four categories: programs that (i) modeled successful women; (ii) provided opportunities for club members to perform; (iii) presented new musical research; and (iv) supported women's musical organizations. As the discussions below reveal, each of these programming areas reinforced May Morrison's aim of amplifying women's voices, combatting a debilitating timidity by promoting forceful musical and verbal speech.

Club Membership and General Programming

The Century Club consisted of 200 (later expanded to 300) women selected by nomination and vote of the board. The constitution contains only one restriction to membership: 175 of the 200 members must live in San Francisco; the rest could come from elsewhere in California.Footnote 21 The lack of any prohibition regarding religion meant that quite a few members were Jewish in a time when Jews were excluded from numerous private clubs. For example, membership lists contain the names of several women from the Sloss family, which owned the Alaska Commercial Company and were among the founders and long-term supporters of the San Francisco Symphony. The Slosses and many other Jews in San Francisco were active in Temple Emanu-El, founded by the German Jewish community in 1850. In fact, the Century Club welcomed the temple's rabbi, Jacob Voorsanger, as a speaker on four occasions.Footnote 22

In terms of race, however, the club's geographic restriction did, in practice if not intent, exclude African Americans, because San Francisco's population was 95 percent white until the substantial migration of African Americans to California during World War II (see Figure 2; note the data for African Americans in 1950 as compared to 1910–40).

Figure 2. Population data 1910–50, San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles, as recorded in the U.S. census. Racial categories reflect those in the census.

The geographic restriction was probably instituted in order to ensure a large attendance at meetings. With no bridges spanning the San Francisco Bay until 1936, participation by women from Marin County in the north or from the East Bay, where there was a larger African American population, would have been unlikely at best (see the data for the East Bay city of Oakland in Figure 2). As Richard Rothstein has shown, geographic racial separation developed directly from government-supported racist policies that began in 1883 with the Supreme Court's negation the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and extended through much of the next century.Footnote 23

Even if the CCC's residency restriction was not racially motivated, we must not forget that the period under consideration witnessed the relentless advance of systemic racism in the country, developments of which club members would surely have been aware, namely the dismantling of Reconstruction, the institution of heinous Black Codes in the South, dozens of court cases supporting segregation that culminated in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision legalizing separate but (far from) equal schools and facilities, frequent lynchings of Blacks, and an outburst of racial violence following World War I that climaxed in the “Red Summer” of 1919.Footnote 24 Yet, despite the club's engagement with politics and social issues, as well as its documented interest in cultural practices other than those of its white membership, I found only one presentation related to African Americans in the 32 years covered by this study—a program of “Old Negro Dialect Recitations and Songs” by a Miss Alexander (no first name given) on January 28, 1903. The program did not pretend to be a serious exploration of, or even a focused engagement with, Black culture. Rather, it functioned as the entertainment for an afternoon of tea and fellowship. Club president Helen P. Sanborn mentioned it briefly in her annual report, citing it among the many “delightful” afternoons sponsored by the Social Entertainment committee: “Our social afternoons with their clever skits, their charming music and recitations, Japanese songs and darkey dialect…, their brave spreads of tea, and even sometimes cake and coffee, their good fellowship, as well as their good cheer, have been delightful,” she wrote.Footnote 25 Indeed, Sanborn placed a higher value on “development and training through constant association” than on the content of the programs. Belying the club's stated purpose (and in contrast to its central mission of providing educational enhancements), Sanborn characterized both the club's musical presentations and its lectures as “attractive accessories” to the more crucial function of bringing women together “on the same plane; where wealth and social position play but a small part, where every woman stands for what she individually is worth.”Footnote 26

Despite Sanborn's idealization of the club's social equality, race was apparently not part of the equation. The white homogeneity of San Francisco's population (and club membership) in these years may have also encouraged racialized listening practices, which reinforced the Otherness of U.S. Blacks. As Jennifer Lynn Stoever argues, such a “sonic color line” renders “dominant ways of sounding as default—natural, normal, and desirable—while deeming alternate ways of listening and sounding aberrant.”Footnote 27 Recital programming at the club did indeed prioritize traditional (white) European classical music, but occasionally the women's attention turned to other traditions, as we will see below.

The Century Club's membership in this period included no women of color. By contrast, some predominantly white clubs in the nation did admit African Americans, and many Black women formed their own clubs during this era. Notable among the latter was the Woman's Era Club (WEC) in Boston, organized between 1892 and 1894. The year 1896 saw the formation of the National Association of Colored Women, the first national Black organization in the country, later called the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs.Footnote 28 The most prominent African American club in the Bay Area was the Fannie Jackson Coppin Club in Oakland (founded in 1899). Like the Century Club, the Coppin Club included music as an essential component of its activities. Its stated objective was “to develop musical and literary inclinations of its members and work for the interests and uplift of humanity.”Footnote 29 The club still exists and now focuses on civil rights and economic improvement for African Americans. As far as I can determine, there was no interaction between the Century Club and the Coppin Club during the period under consideration.

At the national level, the question of admission of Black organizations to the National Federation of Women's Clubs rose to a crisis point in 1900 when Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin tried to take a seat as a delegate from the WEC. Over the objection of the Georgia delegation and especially the Federation's president, Rebecca Douglas Lowe, the board offered to seat Ruffin, but only as a representative of several mostly white clubs to which she also belonged; they refused to admit the WEC as a member organization. The ensuing crisis intensified over the next 2 years until a change in the Federation rules effectively barred Black clubs from joining the national organization.Footnote 30 In 1901, while this issue consumed the attention of the national organization, the Century Club held a formal debate on the issue of whether the “Color Line Should be Drawn in Women's Clubs.”Footnote 31 The presentation was part of the club's formal debate program, designed to offer the women an opportunity to “speak freely and frankly” (to quote May Morrison). The debates always included both sides of the question at hand; in this, and in all other cases, the women rendered no concluding judgment on the merits of the issue.

Many years later, in 1955, the Century Club again faced a racial issue, not of membership, but rather of facility usage concerning musical activities. The minutes of the board meeting of September 12, 1955 record a discussion of “the problem of repeated requests by colored people for the use of the [club's] hall and [grand] piano.” The board approved a motion, which the present archivist notes wryly was “not our finest hour,” specifying that all applicants for rental privileges had to be sponsored by a club member.Footnote 32

Despite the much larger number of Chinese and Japanese Americans in San Francisco, I found no evidence of Asian American club members. In contrast to the dearth of presentations on Black Americans, however, there was substantial interest in the history, culture, and politics of China, Japan, India, and Java. Of the 915 programs presented in the 32 years covered in this article, thirty (3 percent) dealt with Asian topics. Many of these presentations concerned Asian visual arts and some featured Asian or Asian-inspired musics: a Japanese tea ceremony with Japanese songs; a vocal quartet singing Japanese songs; a professional troupe presenting Japanese music and dancing in costume; a performance of Charles Wakefield Cadman's Sayonara to welcome the “Ladies of the Japanese Red Cross Delegation”; singing by “Chinese girls” at a social event; and a performance by local Chinese children that accompanied a lecture on the 1911 revolution in China.Footnote 33

Most of these programs featured performances by white club members. As the annual presidents’ reports make clear, the intention of the sponsoring committees was one of friendly inquisitiveness and a desire to promote a degree of ethnic diversity, in contrast to the virulent racism that had sullied San Francisco's politics in the previous decades.Footnote 34 Indeed, only 9 years before the founding of the CCC, San Franciscans had elected a mayor from the Workingmen's Party, whose slogan was “The Chinese must go!”Footnote 35

At the same time, however, these club presentations also reflect a prevalent paternalism (or perhaps we should say maternalism).Footnote 36 San Francisco's Chinatown was virtually leveled in the devastating 1906 earthquake and ensuing fires, which burned for three days and destroyed 4.7 square miles in the city center.Footnote 37 By 1910–11, however, when the Chinese children sang at the club, the area had largely been rebuilt with wider streets and vibrant buildings. In the following decade the Chinese American community cultivated an assimilationist stance and Western instruments and ensembles proliferated.Footnote 38 The club's programs involving members of the city's resident Chinese population reflected to a certain degree these economic, social, and demographic changes and might have encouraged the CCC to reach out to local Chinese American presenters. It would be instructive to know whether the children who sang in conjunction with the lecture on the 1911 Chinese revolution performed in English or Chinese and what their repertoire was, but unfortunately the documents preserved by the club offer no elucidation.

Considering the discussion above, one might assume that most of the women of the Century Club were part of San Francisco's wealthy upper crust. Certainly the club's first president, Phoebe Apperson Hearst (1842–1919; Figure 3), fits that profile. The mother of newspaper czar William Randolph Hearst, Phoebe Hearst was not only extremely rich, but was also one of the most generous philanthropists of her time. During her life, she gave away more than $21 million. Hearst was an avid fan of opera and supported musical productions, organizations, individuals, and venues.Footnote 39 Despite having only an eighth-grade education, her primary focus was enhancing educational opportunities for women. She was a generous supporter of the University of California (UC), where she built a building for women that included an enormous space for concerts, to which she invited the entire student body in groups of about a thousand. She also endowed scholarships for women that are still awarded today (the grantees are called Phoebes). As president of the Century Club, Hearst could extend her support of women's education to those who never had the opportunity to attend college, as well as to those who had graduated from the university—women with lively curiosity and acumen who were poised to make changes to their circumscribed social position. For the Century Club in particular, Hearst not only served as president for the first 2 years and maintained a constant membership until her death in 1919, but also gave the club a Steinway grand piano and underwrote the entire rental cost for the clubhouse during the first year. At $125/month, this last donation amounted to $1,500 for the year (equivalent to approximately $43,000 today). As the club's delegate to the first conference of the General Federation of Women's Clubs in New York in 1890, Hearst was elected national treasurer.Footnote 40

Figure 3. Phoebe Hearst in 1895. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division (reproduction number LC-USZ62-70333). See http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001704044/.

An examination of the club's membership in its early years, however, reveals that Hearst was more the exception than the rule. Some of the club's members did come from San Francisco's moneyed class, it is true, and, like Hearst, they supported musical causes. For example, May Morrison, though not a musician, gave generously to musical organizations. She and her husband Alexander were among the original group of subscribers to a fund established to replace the enormous Grand Opera House, which was destroyed in the fires following the 1906 earthquake. In 1912 the Morrisons subscribed for two seats at $1,000 each (equivalent to about $26,000 apiece today).Footnote 41 Her estate eventually provided substantial funding for Morrison Hall—the music building at UC Berkeley—and for the Morrison Chamber Music Center at San Francisco State University.

Unlike Hearst and Morrison, however, most of the members of the club came from middle-class backgrounds. To learn more about their social and economic class, I compared the membership in 1908–14 to three lists that document affluence and/or high social status (the first two unpublished): founders of the San Francisco Symphony, contributors to rebuilding the Grand Opera House, and the 1911 Social Registry of the Bay Area. The symphony and opera house supporters were among the wealthiest members of the community. Symphony founders (295 contributors between 1910 and 1912) pledged $1,000/year for 5 years, equivalent to more than $25,000/year in 2021. Subscribers to the opera house rebuilding project in 1912 pledged $1,000–$15,000.Footnote 42 Interestingly, of the 390 members of the Century Club in 1908–14, only 12 percent (forty-four members) appear on the symphony and/or opera house project registers. On the other hand, 43 percent are listed in the Social Registry, which is an indication of prominence but not necessarily of extreme wealth.

Fully 15 percent of the members during these years were unmarried, but most of the single women were not young. I found only two in their late twenties; the rest were in their forties or fifties. Consulting the 1910 census data for the nearly 400 members of the club in the period 1908–14 reveals little in the way of occupation, but for those whose professions are listed, almost all were teachers in public or private schools. Two were principals; one was a university instructor. A few were music teachers. Many others are listed as “own income,” presumably indicating an inheritance. Five out of six members listed without the title Miss or Mrs. were doctors. Members, though not necessarily wealthy, did need to have some degree of financial discretion: During this period, dues were twelve dollars a year (c. $350 today) and there was an initiation fee of $20 (c. $600 today). We can conclude from this accumulation of data that whereas some of the CCC members were affluent, most were middle- or upper-middle class. They seem to have joined the club primarily from a desire for self-education and intellectual enrichment. Their coveted “forceful voices,” however, were only possible in the context of their comfortable socio-economic position. The club's programming offers no insight into what the CCC members might have expected in terms of enabling the voices of lower-income women, other than an often-expressed support for various community improvement projects and a desire to improve the lives of the poor through educational reforms (the subject of numerous programs).

The club's constitution mandated political neutrality. The by-laws state: “No demonstration on behalf of any political or religious object shall ever be made by this Club; and sectarian doctrines or political partisan preferences shall not be discussed at this Club at any regular or special meeting.”Footnote 43 Deliberations on religious and political topics that did not endorse partisan or religious preferences regularly took place, however, and always included progressive and conservative viewpoints. Nevertheless, an examination of the club's programming suggests a reformist outlook, especially in the area of suffrage. (California extended the vote to women in 1911, 9 years before the national constitutional amendment.) At the same time, the club's progressivism was limited by its own demographics, as noted above. Only certain voices were raised through its activities.

From its earliest years, the CCC's building contained a large space for lectures, presentations, and musical performances (Figure 4). Its extensive archive, currently being processed, not only offers an unusual window into the general workings of a highly influential woman's club that has been in continuous existence for more than 130 years, but also reveals the vital role of music in its proceedings.

Figure 4. Century Club lecture and music hall in the early 1890s. Courtesy of the CCC.

Musical Programming at the Club

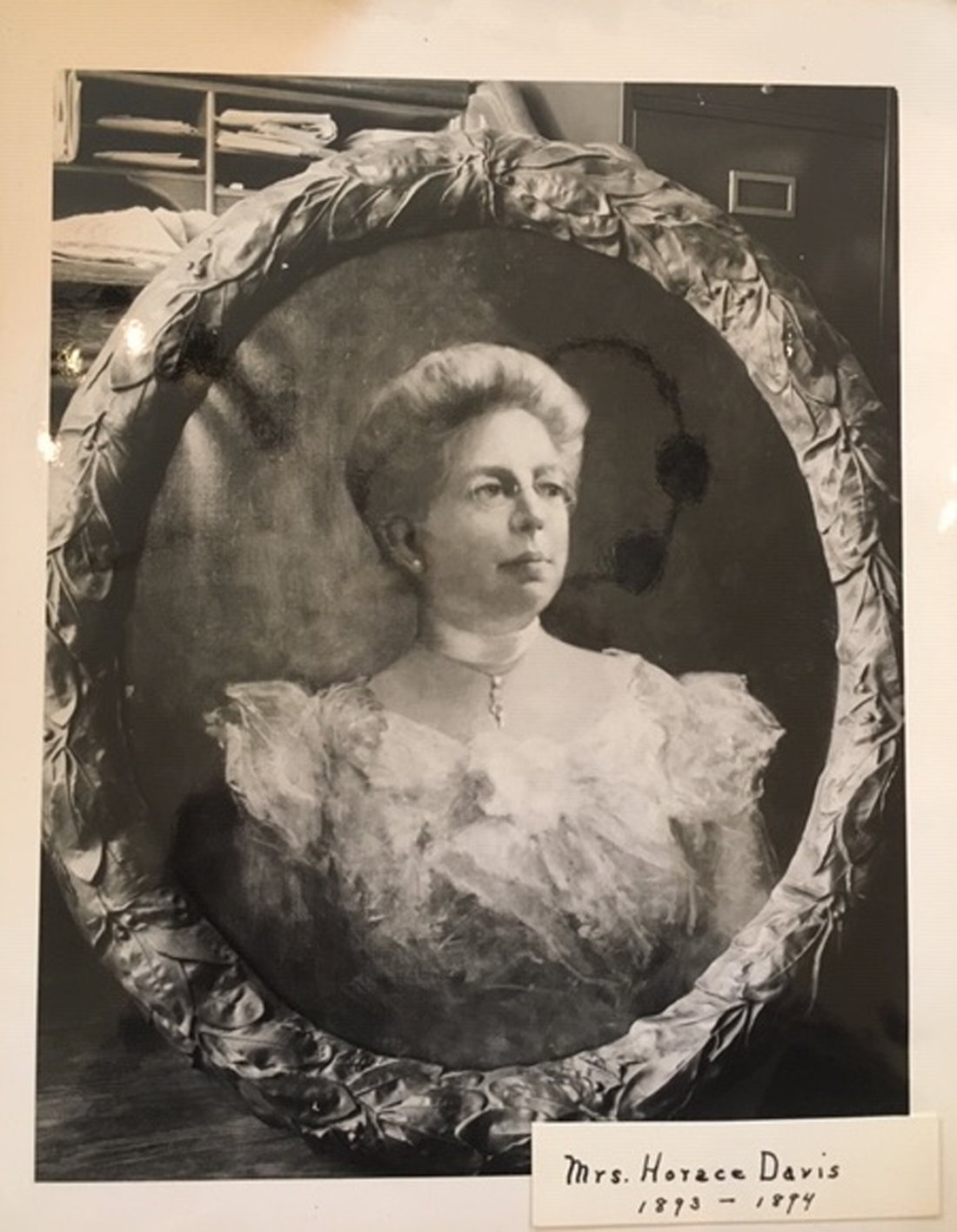

A group of subject-based committees arranged the programming for the CCC's Wednesday meetings. For the first 2 years, musical programs were planned through a subcommittee of “Art and Literature,” but by September 1890, an independent music committee had formed, which set up about four programs each year. The first chair of this new Music Committee was Edith King Davis (1852–1909; Figure 5), a pianist who became the club's president in 1893–94.Footnote 44 The other five committees were Art and Literature, Practical Questions of the Day, Science and Education, Social Entertainment, and Formal Debate.

Figure 5. Edith King Davis (1852–1909), pianist and president of the Century Club, 1893–94. Courtesy of the CCC.

Information on the specific programs comes from the extensive Annual Reports, which list the committees, presenters, and presentation titles. Unfortunately, the archives contain no actual papers. About three dozen recital programs do survive, however; and from 1898 through 1904, the reports list the full repertoire for recitals sponsored by the Music Committee.

The six-committee programming model began to break down near the beginning of World War I, allowing for a more flexible variety of presentations. From 1912–13 and onward, the reports no longer list programs by committee, but rather just by date. Nevertheless, music continued to have a designated committee, responsible for several presentations each year. Although this new programming model might have marked a good stopping point for the present study, I continued to 1920 to determine whether the restructuring led to a reduction in the number of programs with musical content. As Figure 1 shows, it did not; music continued to enjoy a large presence in the club. The year 1920 also marks a good endpoint in light of the death of Phoebe Hearst in 1919 (from the “Spanish flu” epidemic); the new paradigms for women that emerged during the “Roaring 20s”; and the advent of radio, which, although it obviously did not put an end to live performance, did alter dramatically the way music reached a public audience.

In addition to programs sponsored directly by the Music Committee, presentations arranged by the other committees also frequently included music. Figure 6 compares the programming by the Music Committee (the almost steady, solid line at the bottom) to the overall number of programs in all fields (the dashed line at the top) and the actual number of programs that included musical components (the dotted line in the middle).

Figure 6. Century Club musical programs, 1888–1920. (Graph created by the author from an examination of all programs presented during these years.)

The sharp dip in the center of the graph represents the temporary decline in activity following the earthquake of April 18, 1906. The CCC's building escaped damage, although it was on the edge of the fire zone. Following the disaster, the club rented its space to the California Supreme and Appellate Courts until August 1907. Activities temporarily ceased, but then resumed sporadically in September 1906, with meetings held in individual homes and at the First Unitarian Church.Footnote 45 A Music Day had been scheduled on the day of the quake—a large event organized by singer Louise Marriner-Campbell (1837–1922) that involved a chamber orchestra performing the Bach double violin concerto, a Beethoven string trio, and works with voice. Of course, it did not take place.Footnote 46

As Figure 6 shows, music had a strong cross-disciplinary pull. That the club's Social Entertainment committee would consider music an essential enhancement might be expected. More surprising, however, are the number of presentations by other committees—for instance, a talk in 1895 by singer Marie Withrow (1853–1932) on “Tone Perception” sponsored by the Science and Education committee, or a session on the history of music in the United States in general, and the development of the oratorio in particular, sponsored in the same year by the Art and Literature committee.Footnote 47 Marriner-Campbell, who appeared seventeen times in CCC presentations over a 27-year period, delivered the history lecture. Such presentations by club women—whether on music or other topics—challenged the coding of “knowledge” and “lecture” as male, thus emboldening female voices. The number of such lectures by club members increased over the period under consideration as the women gained confidence.

Programs that Modeled Successful Women

Century Club musical programming often featured successful nonclub members through presentations by female composers and performers. The club also reinforced such appearances by holding formal receptions for famous visiting artists, during which CCC members would typically perform. For example, in 1900 the club welcomed German soprano Johanna Gadski, along with American baritone David Bispham, who were in San Francisco performing with the Metropolitan Opera.Footnote 48 The eminent guests listened to an afternoon of music for violin and piano by club members Claire and Elsie Sherman. More than 500 people attended.Footnote 49 The two singers, along with soprano Suzanne Adams, came back the following year when the Met returned to San Francisco, on which occasion the club provided an exceptional opportunity for young local talent: The Met stars heard a program by the voice students of Marriner-Campbell.Footnote 50

Actress and singer Lotta Crabtree, who commissioned a fountain erected on Market Street, came as a guest on November 22, 1893, as did composer Amy Beach, who traveled to San Francisco for the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition (PPIE) in 1915. The exposition had commissioned Beach to compose the “Panama Hymn,” which was performed on the fair's opening day (February 20) and repeated frequently throughout its nine-month duration. Beach appeared at a CCC reception in her honor on May 12. As with the visits by the Met singers, club members presented a special entertainment for her, in this case a one-act drama set in San Francisco's Chinatown.Footnote 51

That the club sent invitations to such renowned musicians speaks to its mission of exposing the membership to prominent women in various fields. That such women accepted the club's offer speaks to the CCC's own forceful voice within the community. Beach herself, of course, confronted issues concerning the projection of her distinctive voice. Following her marriage to Henry Harris Aubrey Beach in 1885, she curtailed her public performance schedule at his behest, and donated the proceeds from any concerts she did present to charity (an expected female obligation). Until her husband's death in 1910, she identified herself as Mrs. H. H. A. Beach and it was only with some reluctance that she began to use the name Amy Beach shortly thereafter. The restriction on Beach's concert career during her husband's lifetime led her to concentrate more intensely on composition, an activity he encouraged. At the same time, she received no formal training, as composition study was largely closed off to women in the widespread belief that music “could only be transmuted into great art by intellect and the ability to think in abstract terms, the latter supposedly found wanting in women.”Footnote 52 In 1904–5, the Century Club made a change similar to Beach's: Beginning with the seventeenth Annual Report, the membership lists included in them provide first names as well as married names.

The club took special interest in female composers. On August 4, 1915, for example, the members welcomed two (male) organists currently performing at the PPIE, Clarence Eddy and Sumner Salter, but May Morrison's president's report singled out Salter's wife, Mary Turner Salter (1856–1938), as “a composer of note…. Many musical people were in attendance on that afternoon and a very enjoyable impromptu program was given by some of the distinguished musicians present.”Footnote 53 Mary Salter was a graduate of Boston College of Music, a voice instructor at Wellesley College, and a prolific composer of songs for voice and piano. The cover of the sheet music for one of her compositions, published by G. Schirmer in 1904, for example, lists fifty-one of her “Songs and Ballads” available for purchase.Footnote 54 Salter was also one of the founders of the American Society of Women Composers.

When male composers performed at the club, their wives typically appeared with them. On March 1, 1893, for example, Edgar Stillman Kelley gave a presentation with his wife, pianist Jessie Gregg, and five others, including several club members.Footnote 55 Eleven years later the Literature Committee sponsored another program of Kelley's music during a commemoration of poet Edward Rowland Sill, whose texts Kelley had set to music. On this occasion, club member Mary Camden Wetmore (1861–1924) sang. She was very active in the organization, appearing on five programs during the period under consideration and directing the music on a sixth.Footnote 56 Edward Schneider, composer and faculty member at Mills College in Oakland, performed on December 2, 1903 with his wife, noted mezzo-soprano Katherine L. Adler Schneider, and club member Elsie Sherman (1881–1938).Footnote 57

If an opportunity arose to feature a female composer, the CCC was receptive, even if the woman was little known, such as Leila France McDermott (1854–1940), who appeared on September 24, 1917 for “An Afternoon with a California Author and a California Composer.” McDermott had published, in that same year, a book of songs for children derived from bird calls.

At times, the club sponsored programs open to the public outside of its regular Wednesday afternoon membership meetings. For example, on November 22, 1910, 17-year-old pianist and composer Cecil Cowles (1893–1968) presented a recital that included a number of her original vocal and piano works. Phoebe Hearst, who eagerly supported many young musicians, helped to underwrite the event.Footnote 58

Indeed, the club provided a platform for many aspiring local performers. Among the most important was pianist Ada Clement (1878–1952), who played there in 1902 and 1904, when she was just beginning to develop her career. In 1917 Clement founded, with Lillian Hodghead and Nettiemae Felder, the Ada Clement Piano School, which incorporated in 1923 as the San Francisco Conservatory.Footnote 59

Similarly, the CCC welcomed three of the four Pasmore sisters—daughters of composer, pianist, and singer Henry Bickford Pasmore—who were making headlines at the turn of the century: Mary, violinist; Dorothy, cellist; Suzanne, pianist; and Harriet (more widely known as Radiana), contralto.Footnote 60 The three instrumentalists formed a piano trio that garnered rave reviews in the local press (Figure 7). Their exceptional skill led to the later success of Dorothy (1889–1972) and Mary (1886–1974), who were among five female string players who joined the San Francisco Symphony for the 1924–25 season; they were the first women in the country to be hired by a major professional orchestra (other than as harpists). Conductor Alfred Hertz brought in the women without any fanfare, quietly changing the gender composition of professional orchestras in the United States.Footnote 61 The Pasmore piano trio performed at the Century Club on April 17, 1901, and the individual sisters participated in other recitals in 1893, 1913, and 1914.Footnote 62

Figure 7. The Pasmore Trio, 1912. Left to right: Suzanne (piano), Mary (violin), and Dorothy (cello). This photo appears on the Web site of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music: https://sfcmhistoryblog.wordpress.com/2011/11/16/the-pasmore-trio/.

The club also heard from well-known local male performers, but often they brought with them talented women. An example is Hother Wismer (1872–1946), whose violin study in Europe was supported by Phoebe Hearst in the 1890sFootnote 63 and who later played viola in the San Francisco Symphony. He appeared on twelve CCC programs from 1891 to 1916, six of which also included his mother, singer Mathilde Wismer, “one of the oldest members of the San Francisco Musical Club and one of the most beloved and highly esteemed women in San Francisco's musical and club activities.” One obituary upon her death in 1921 characterized her home as “the mecca of the local musical world.”Footnote 64

Recital Performances by Club Members

The CCC's recital programming during its first 32 years included 397 individual performers—285 women and 112 men. Forty-six were club members. The men almost always appeared in an ensemble context, as did the majority of the nonclub women. Other than Hother Wismer, the most prominent men included Giulio Minetti, leader of the Tivoli Opera House orchestra and conductor of several nonprofessional ensemblesFootnote 65 (four appearances); violinist Henry Heyman, one of the founders of the city's Philharmonic Society in the 1880s; violinist and composer Henry Holmes; prominent local pianist Fred Mauer; Henry Pasmore (three appearances); pianist and composer Ashley Pettis; organists Wallace Sabin and Uda Waldrop; pianist and conductor Walter Handel Thorley; conductor Theodore Vogt; and five San Francisco Symphony members—Kajetan Attl, harpist, Emilio Puyans, flutist, Wenceslao Villalpando and Arthur Weiss, cellists, and Nathan Firestone, violist. They all played in ensemble situations that included women.

The forty-six club members who performed on CCC programs were not widely known professionals and thus their appearances represented a significant stepping out from their daily (socially restricted) lives into the spotlight of public exposure, much in the same way as their nonmusician colleagues subjected themselves to the public eye by participating in formal debates and lectures. At the same time, some of these women were highly skilled, as evidenced by the “forceful” repertoire they presented, which required intensive training and a willingness to engage with music traditionally coded as masculine/strong (e.g., Beethoven, Liszt), as well as by their performances of contemporary works (also a traditionally male purview). Especially noteworthy in this regard are violinist Elsie Sherman, cellist Ida M. Holden, and pianists Ina Griffin Cushing, Helen Andros Hengstler, Marie Wilson Stoney, and Ella Partridge Odell, all of whom presented music requiring significant technical prowess and who included in their programs works by contemporary figures such as Niels Gade, Christian Sinding, and Anton Arensky.

Many of these women served on the club's Music Committee, and in this role helped to promote and encourage the musical voices of less highly trained members. In 1902–4, when programs were particularly rich in contemporary music, Hengstler, Odell, Cushing, and Sherman all served on the Music Committee.

Cushing (1865–1955) and Odell (1862–1927) were exceptional in receiving recognition in the local press, at least prior to their marriages. Reviews in the San Francisco Chronicle and the Oakland Tribune highlight Odell's technical skills and single out Cushing as “among the best musicians of Oakland and San Francisco.”Footnote 66 Cushing played in ten programs at the club, one of which, on February 17, 1912, featured historical keyboard instruments—an Italian spinet and a German clavichord. Odell made her first appearance (as Ella Partridge) on May 22, 1889 and then performed on thirteen additional concerts up to 1914. Because neither developed an independent professional career, their club recitals served as an outlet for their considerable talent, especially after their marriages.

As far as Andrea Thurber, the club archivist, and I can determine, nonmembers and members alike appeared on Century Club programs without remuneration. The club was seemingly influential enough that prestigious artists, educators, scientists, historians, and others offered their services without a fee.Footnote 67

Musical performances do involve some expenses, of course, the largest of which would have been renting and tuning a piano—a cost that could prove considerable for a young organization. The Annual Reports list expenses for “piano” in the treasurers’ reports, but without further detail; the annual outlay averaged $50–$70 (with a range from $36 to $111).Footnote 68 In 1896–97, the club made a strong commitment to musical performance by raising $600 in subscriptions to purchase a piano.Footnote 69 Before the members could act, however, Phoebe Hearst stepped in and gifted a “nearly new” Steinway parlor grand.Footnote 70 (In 1954, the club replaced Hearst's piano with a concert grand at a cost of $7,000 and authorized tuning it four times a year, attesting to the continued frequency of recital performances. The board sent announcements to music groups throughout the area advertising the availability of the instrument and the hall.)Footnote 71

Among the club members who performed on recitals, all but four were vocalists or pianists. One was a harpist, an instrument typically coded female as noted above. The other three were trumpeters, countering the typically gendered association of brass instruments with male performers. The three women—Ethel Beaver, Sophia Brownell, and Persis Coleman—performed only once at the club during the period under consideration, in a 1906 presentation sponsored by the Art Committee,Footnote 72 but their membership suggests that the CCC was an attractive outlet for musicians who challenged traditional norms. In addition to Louise Marriner-Campbell (cited above), other vocalists who appeared frequently include Elizabeth Putnam (1859–1925; nine times), Mary Camden Wetmore (six times), and Marie Withrow, one of the club's founding members.Footnote 73 On October 30, 1895, Withrow and singer Anna Beaver (1852–1937; sister of trumpeter Ethel Beaver) staged a formal debate on music as a force for improving society: “Resolved, that Music exerts a greater influence for good than either Poetry or Painting” (Figures 8 and 9).Footnote 74 Reflecting the club women's adherence to a historical, socially based norm that discouraged them from appearing too assertive, the presidents’ reports often lament the dearth of willing participants in the club's debate program. Withrow had no such qualms. She and her sister Eva, a painter, frequently took part in prominent public activities. Twenty years after the debate, Marie published a book of short (“staccato”) aphorisms on the development of the vocal art. Her approach to singing emphasized the role of the intellect on performance skill, thus accentuating the links between music, rationality, and character development. “If we are normally healthy and normally built,” Withrow wrote, “all the obstacles to splendid vocal work are Mental. Attention must be turned to how we think, what we think, how fast or slowly we think, and what we expect to get out of our thinking….” In another pithy piece of advice, she writes: “At the sight of a new score, the Amateur begins to sing. The Artist begins to think.”Footnote 75 Reinforcing the connection between music and daily living, the anonymous reviewer in the San Francisco Chronicle claimed that the book was “as much a work on how to live as on how to sing.”Footnote 76

Figure 8. Marie Withrow (1853–1932), singer and one of the founders of the Century Club. Courtesy of the CCC.

Figure 9. Anna Beaver (1852–1937), singer and Century Club member. Courtesy of the CCC.

In addition to recital programs, the Music Committee at times presented short operettas. Twice, for instance, members of the club sang selections from Virginia Gabriel's Widows Bewitched, the first time in 1894 accompanied by members of the all-female Saturday Morning Orchestra (discussed below) and the second time in 1910 with piano accompaniment.Footnote 77

Presentations Highlighting Musical Research

Club members tried to stay abreast of the latest developments in all fields, and music was no exception. Historical performance practices and pre-Baroque repertoire, for example, were quite new areas of research in this era. One example of the club's awareness of these areas of interest is Cushing's previously cited performance on historical keyboards. A second was an extensive program on February 11, 1903, featuring Elizabeth Putnam in a lecture-recital entitled “Popular Song—Music of Olden Times,” including a variety of performers singing selections from the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries.Footnote 78

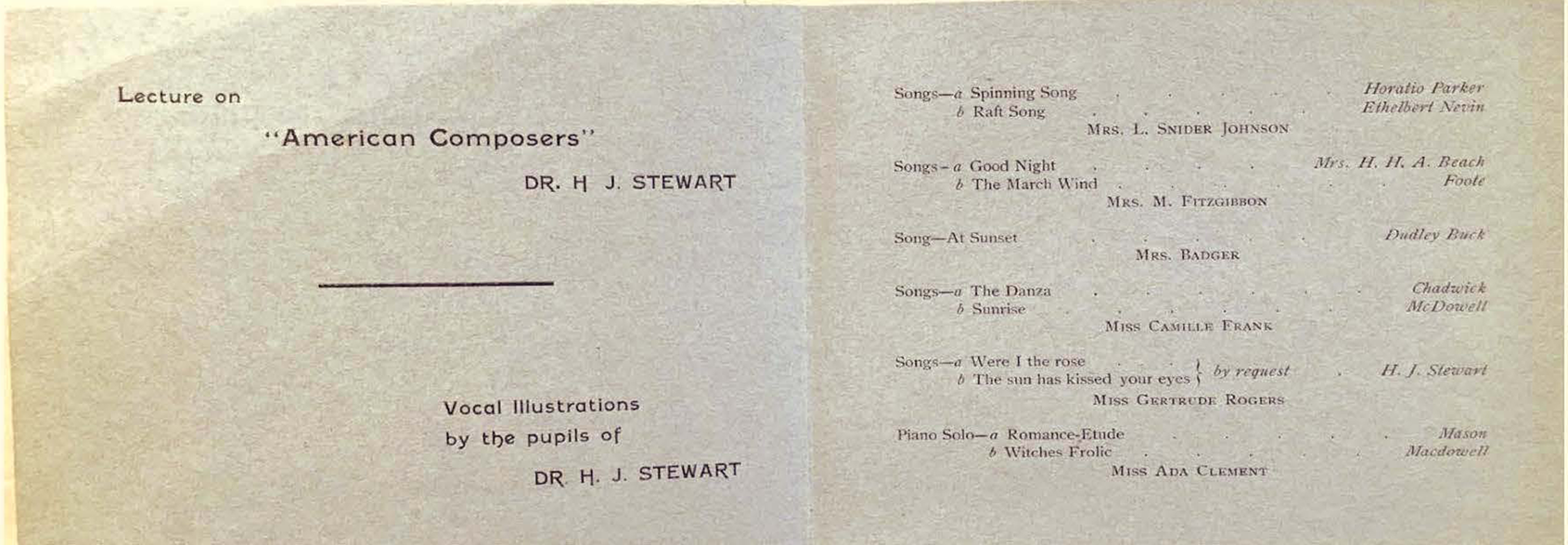

The club also learned of new trends in composition. In 1902, for example, Humphrey John Stewart presented a lecture-recital on “American Composers,” illustrated by performances by his voice students and Ada Clement (Figure 10). Stewart included music by himself and eight contemporaries, all but one of whom were alive at the time; the one who was not (Ethelbert Nevin) had died only 1 year earlier. MacDowell, the most famous of the group, denigrated such all-American programs as political events that encouraged “musical protectionism” and he even discouraged references to himself as an “American” composer.Footnote 79 Stewart, however, apparently felt that it was not only important to expose intelligent members of his community to American music in general, but also to feature contemporary (albeit mostly East Coast) U.S. creators.

Figure 10. Lecture-recital program on American composers, presented to the Century Club on September 24, 1902 by Humphrey John Stewart (1856–1932). Courtesy of the CCC.

Arthur Fickenscher, an early experimenter with microtonal music and the inventor of the Polytone, which could produce sixty pitches to the octave, gave a presentation on December 7, 1904 with his wife, singer Edith Cruzan. Attesting to the cross-disciplinary reach of music, the Social Entertainment Committee sponsored their appearance. This same Social Entertainment Committee presented two other programs featuring new technology: an 1894 demonstration of an “electric orchestra”—perhaps meaning recordings—and another in 1909 that showcased the Welte-Mignon player piano, which had only been introduced in the United States 3 years earlier.Footnote 80

Folk music, an area of considerable interest at the time, formed the basis for several programs. In addition to the Japanese songs referenced above, programs included folk songs from Germany, Russia, and Romania. The presenter of the Romanian program was Lucy Sprague Mitchell, the first dean of women at UC and a lecturer in the English Department.

This period also marks one of intense interest by ethnologists in the recording and transcription of American Indian songs, sometimes in questionable situations (such as Frances Densmore's surreptitious notation of a song by Geronimo at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair).Footnote 81 The resulting song collections inspired composers such as Beach and MacDowell to embed Indian melodies in instrumental chamber music and orchestral works. Others, such as Arthur Farwell, set Native American songs in miniatures for piano alone or for solo voice with piano, sometimes in a simple style, other times using quite adventurous harmonic language. Kara Anne Gardner links the craze for such “Indianist” music—manifest in an extensive output of published sheet music—to an antimodernist sentiment among middle-class intellectuals, precisely the demographic represented in the CCC.Footnote 82

Two presentations during the club's first 32 years reference Native American music. The first, on November 19, 1913, consisted of a special program arranged by then-president Marie Withrow that contained three distinct sections: “Zuni Indian songs” sung by “Miss N. L. Walker”; “English songs” by “Miss Eva Falker”; and “German songs and Recitation of ‘Das Hexenlied’” by “Mr. Ernst Wilhelmj.” Withrow's presidential report contains no commentary on this unusual grouping of repertoire, but it is possible that she consciously chose to use her influence as president to suggest the inherent validity of ethnically diverse musical expressions.

The second occasion was a dramatic presentation for voice and piano on January 29, 1919 called “Gesture Songs and Poems of the American Desert,” featuring Alice Ena Hicks Muma (1887–1938), accompanied by pianist Estelle Drummond Swift.Footnote 83 Muma had graduated from UC in 1913; Swift was a well-known local keyboardist who was appointed organist at Berkeley's First Unitarian Church a few years after this event.Footnote 84 The two women presented the same program a month before their CCC appearance at the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority in Berkeley.Footnote 85

The printed program for “Gesture Songs” consists of a prose narrative followed by a list of “poets, composers, and authors” whose works were included in an uninterrupted presentation. Muma aimed specifically to evoke images of the desert (particularly at sunrise) and to reference the customs of Native Americans. Without identifying any specific Indigenous peoples, she writes that the program included “an Indian Fire Song”; a representation of an “Indian lover [who] woos his bride by strutting before his maiden's house displaying his gorgeous blanket”; and an “Indian Mother [who] croons her baby with a flute song with which her warrior husband wooed her.” References to the home, to wooing, and to lullabies seem designed specifically to appeal to female audiences.Footnote 86

The composers listed at the end of Muma's narrative were all part of the Indianist movement. They include well-known figures Charles Wakefield Cadman and Arthur Farwell as well as lesser-known ones: Carlos Troyer (whom Michael Pisani calls a “German-born con artist who affixed wildly imaginative ritualistic descriptions of Indian life in the Southwest to his melodramatic fantasies”); Los Angeles composer Homer Grunn, who set Native American tunes in a Romantic style; and Thurlow Weed Lieurance, who composed nearly a hundred songs based on Native American melodies he transcribed.Footnote 87

Muma's narrative gives no titles of specific works, but it is easy to identify some likely candidates. Troyer's Traditional Songs of the Zuni Indians (1904), for instance, includes both the “Lover's Wooing, or Blanket Song” and “The Sunrise Call”; Lieurance's Nine Indian Songs (1913) opens with a lullaby that the composer describes in words very similar to Muma's narrative quoted above: “While the Indian woman croons her lullaby, her returning warrior signals his coming with the flute, playing the song he wooed his sweetheart with.” Gertrude Ross's Three Songs of the Desert (1914) includes depictions of Sunset, Night, and Dawn. Cadman was likely represented by a selection from his collection From Wigwam and Tepee: Four American Indian Songs Founded upon Tribal Melodies (1914) or his older Four American Indian Songs (1900), and Grunn by a piano solo, possibly his “Song of the Mesa: Tonepicture of the Desert” (1916). The program included readings by authors who wrote about the desert and Native American cultures: Orville Henry Leonard, whose The Land Where the Sunsets Go: Sketches of the American Desert appeared in 1917, and Mary Austin, who studied the lives of the Indigenous inhabitants of the Mojave Desert and published The Land of Little Rain in 1903.

This program surely drew inspiration from Farwell's widely acclaimed lecture-recitals, which he presented in cross-country tours during the first decade of the century, and which, as Michael Pisani recounts, “spawned countless imitations by other performers,” who “also believed in the persuasive power of American Indian music as a source for composition.”Footnote 88 Although Farwell idealized Native American song, his work was hardly free from “overtones of imperialism,” notes Beth Levy. He mixed scientific anthropology with subjective reflection, eschewed in-person contacts with Native Americans in their home environments, and relied on Western notation and translated texts. Nevertheless, Levy concludes, even though his “attitudes toward Indians would never completely slough off their skin of exoticism, Farwell found in Indian ritual a valuable example of the power of music to unify and sanctify a community.”Footnote 89 Similarly, Muma aimed to use Native American communal ritual to project a wider vision of peacefulness and oneness with the natural environment: “No attempt has been made to imitate Indian gestures or movements,” she wrote, “but the desire has been to give an impression of the Desert—a call to prayer at sunrise, a visualization of some of a day's happenings upon the Desert.” Her gentle vision of Indian life contrasts sharply with fierce portrayals of Native Americans more typical at the time. One egregious example with local resonance was Victor Herbert's Natoma (1911), featuring a libretto by the San Francisco lawyer and composer Joseph Deign Redding, which had premiered with great fanfare 8 years earlier. Redding's libretto depicts the trope of the submissive racial Other who supposedly is happy to subjugate their desires to those of whites: The self-sacrificing “Indian maiden” Natoma commits murder to ensure the happiness of her white mistress Barbara, not only forfeiting her freedom (in the end, Natoma converts to Christianity and enters a convent), but also suppressing her own amorous desires. Herbert's climactic “Dagger Dance” from Act 2 is an egregious example of racial stereotyping.

In contrast, Muma's idealization of Indian life reflected a common romantic trope of the time that served to counter the discontent many Americans felt with the increasingly industrialized world. “Playing Indian” could be empowering, Gardner reminds us, as “an antidote to overcivilization,”Footnote 90 especially, we might add, for women seeking a place in an intimidating patriarchal society.

Support for Women's Musical Organizations: The Case of the Saturday Morning Orchestra

One of the CCC's most fruitful associations was with the all-female Saturday Morning Orchestra—all-female, that is, except for the conductor, Jacob H. Rosewald, who came to San Francisco from Baltimore in 1884 with his wife JulieFootnote 91 on the advice of doctors to seek a warmer climate (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Sketch of the Saturday Morning Orchestra by Oscar Kunath, San Francisco Chronicle, October 15, 1893.

Rosewald (1841–95) had been superintendent of music in the Baltimore public schools, concertmaster of the Peabody Orchestra, and a conductor and violinist with the Emma Abbott Opera Company.Footnote 92 Julie Rosewald (1847–1906) was a widely acclaimed operatic soprano who appeared throughout Europe and the United States with touring opera companies. In 1884 she became the first female cantor in the country at Temple Emanu-El in San Francisco,Footnote 93 cited earlier for the association of its rabbi and several of its members with the CCC. Despite Julie's renown and the links between the temple and the club, she does not seem to have performed there. Jacob, however, did. In 1890 he played with pianist Edith King Davis and then founded the Saturday Morning Orchestra, which included the “daughters of many of the first families in the city.”Footnote 94 The orchestra performed at the club on March 11, 1891, eleven months before its first public concert; it reappeared twice more in the following 5 years.Footnote 95 Beginning with only fifteen members, the group first met at the home of club member Joanna Wright (1830–1919), a conservative Southerner who founded a local chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. Wright continued to act as president, secretary, and treasurer of the orchestra even after its size exceeded the capacity of her home. At its public debut in February 1892, the Saturday Morning Orchestra included thirty-five women and thereafter received rave reviews. Exemplifying the more traditional role of women in U.S. society, the orchestra donated all proceeds to hospitals and orphanages. By November 1892, the group was playing at the 4,000-seat Grand Opera House, which the anonymous reviewer in the Chronicle states (improbably) was sold out.Footnote 96 The ensemble seemed to be flourishing, expanding to forty-five members the next year; but in February 1894 Rosewald resigned after a dispute about orchestra seating. He died the following year. Fritz Scheel, who made a splash in San Francisco at the 1894 Midwinter Fair and would become the first conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1900, replaced Rosewald. Activating their forceful group voice, however, the women rebelled. In the interest of improving musical quality, Scheel had reduced the orchestra to strings and harp; he demanded a salary that was impossible for this amateur organization to provide; and he made “so many exactions and objections that the young ladies became discouraged.”Footnote 97 The controversy raises the question of the appropriate aims for such organizations: in short, how to balance professional performance standards with much-needed training—especially for women, who had few opportunities to gain orchestral experience. Scheel clearly prioritized performance excellence over education. The women, on the other hand, craved an artistic experience that was mostly the purview of men and, as Morrison advised, they “stood their ground” firmly.Footnote 98 The orchestra fired Scheel and hired band director Alfred Roncovieri (1868–1945), who rekindled the group's enthusiasm and emphasized the organization's training goals, but unfortunately he was not able to reclaim its former success. The last recorded concerts took place in 1896. Roncovieri subsequently became Superintendent of the San Francisco Public Schools, where he was able to further the cause of music education by introducing instrumental music instruction into the curriculum.

Conclusions

Judging from her correspondence and donations, Phoebe Hearst's aims in supporting musical education in general and organizations such as the Century Club in particular were simultaneously practical and idealistic: Through her financial support, she could enrich the quality of the cultural environment; but more broadly, through her influential position in the community, she could help to develop enlightened critics of the arts and mold a more edified citizenry. Hearst was not alone, of course, in touting the personal and communal benefits of musical training—a concept well-established in writings of the time. Charles Seeger, for example, lauded the social benefits of music in a 1912 talk at a “grand orchestra concert” that initiated the San Francisco People's Philharmonic, heralding music “as a preventative of crime, a stimulator of intelligence, and a force for character development.”Footnote 99

The Century Club similarly underscored the crucial role of music in society. Rather than raising money for benevolent organizations—a worthy cause to be sure, but also a stereotypical female one—the club supported foundational gender transformations by enhancing women's knowledge of the latest developments in science, social science, and the arts; promoting a positive self-image; and, most importantly, amplifying their voices. By furthering female learning through presentations covering a wide variety of topics (music prominent among them) and encouraging members to develop the self-confidence to speak out and perform in public with conviction in these presentations, the club buttressed the ambitions of the forthright and determined women of the era who were entering the public workforce.

That is not to say that the members of the Century Club ignored concerns about children and the home. Many club presentations dealt with reforms to enhance pre-college education. In addition to the appearances of Sarah Cooper, the instigator of the kindergarten movement in the city, the club welcomed Estelle Carpenter (1874–1948), Supervisor of Music for the San Francisco Public Schools from 1897 to 1945; she conducted a children's chorus from the Redding Primary School as part of a Thanksgiving program on November 23, 1904. Carpenter, who was known as “that dynamo in skirts…,” used her public position to speak out with her own forceful voice. As a biographical sketch of her has noted, “Under her guidance … the school system initiated one of the most innovative and thorough musical programs in the nation.”Footnote 100 Like Seeger, Carpenter underscored the power of music to shape individual character. In a 1916 letter to her supervisor, superintendent Roncovieri, she wrote that

the emotions may be intensified and uplifted by the continuous use of the right kind of music. This will have the correct effect upon the impulses. There is no other subject that can so grip the whole child. It gives him poise, power, and a higher development, because it gives him a higher love…. If rightly used music has the power to formulate the motives of life.Footnote 101

Carpenter does not define the “right kind of music,” but in her letter she emphasized the choral music activities in the schools and advocated for music by modern composers in general and California composers in particular.

The Century Club women, like Seeger, Carpenter, and many others, considered music an integral, necessary, formulative, and defining constituent of civilized life. Their support of artistic creativeness enriched the local musical environment and stimulated debate about the proper role of the arts in the public sphere. The club's prominent inclusion of music at once reinforced women's traditional role as the bearers of culture, while also moving well beyond that limited goal by encouraging women in music (and many other professions) to enter public life with confidence.

Like the mostly white middle-class women populating the energetic New Woman movement of the time, the members of the Century Club pursued an ideal of gender equality through the lens of their own comfortable social position, which provided them the leisure and opportunity to break out of constricted gender roles. Indeed, the wealth of women such as Phoebe Hearst actually gave them some degree of independence to promote a progressive agenda (albeit limited by racial and demographic boundaries) without provoking condescending or disparaging responses. Women artists and writers have long been hailed as a vital part of this movement. The activities of the Century Club underscore the contributing role of female musicians as well—performers, researchers, scholars, and composers.

Leta Miller, Professor Emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has published widely on twentieth-century music, including her 2011 book Music and Politics in San Francisco and biographies of composers Aaron Jay Kernis and Chen Yi. She has authored three books on Lou Harrison and more than twenty articles on Harrison, John Cage, Henry Cowell, Charles Ives; music in the San Francisco area; and the musical philanthropy of Phoebe Apperson Hearst.