Berry Gordy Jr.’s Motown Records was one of the most successful empires in popular music history, churning out hundreds of catchy, chart-topping singles with remarkable efficiency. This success was due in large part to the company's stable of highly skilled professional session musicians. With limited direction, these musicians were able to improvise intricate arrangements that gave Motown's music a distinctive sonic identity—what is commonly referred to as “the Motown Sound.”Footnote 1 However, exactly who played on their most iconic recordings remains a mystery because, as was standard practice within the music industry, no Motown release in the 1960s ever explicitly credited its session musicians.Footnote 2

These practices have led to conflicting accounts, the most famous of which concerns James Jamerson (1936–1983) and Carol Kaye (1935–), both of whom worked for the company—Jamerson as the in-house bassist for Motown's Detroit studio and Kaye as the go-to bassist for Motown's lesser-known West Coast recording operations. To this day, Kaye alleges that she has been purposefully omitted from Motown history, despite, as she claims, having played on hit singles by acts such as the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, and Brenda Holloway. Conversely, Jamerson—who died more than thirty years ago—continues to be vehemently defended by acolytes, such as biographer Allan Slutsky, who see Kaye's claims as blasphemous.

This particular controversy highlights the historiographical dilemma posed by uncredited session musicians: in the absence of direct evidence, their histories have been constructed largely out of memories, hearsay, and speculation—the veracity of which are difficult to determine. Although critics, fans, and scholars continue to take ardent positions on both sides of the Kaye/Jamerson debate, evidence has recently surfaced that sheds new light both on the controversy itself and on the discourse surrounding it. Drawing on two previously unexamined sources—Motown's Los Angeles Musician's Union contracts and Kaye's personal session log—this article reconstructs Kaye's involvement with Motown and, in so doing, reevaluates the merits of the Kaye/Jamerson controversy. From these sources, I document that Kaye played on more than 175 songs for Motown, including as many as five Top 40 hits. These sources confirm that Kaye's place in Motown history is larger than her critics would have us believe, yet at the same time, they also complicate many of her own claims. Building on the work of Motown historian Andrew Flory, I explore the role of session musicians in Motown's creative process and how critics and fans have subsequently received both bassists. As I argue, the vacuum created by the company's decision not to credit its session musicians has propagated a problematic discourse of geographic and stylistic authenticity, in which Jamerson has been valorized and Kaye has been dismissed. Ultimately, Kaye's story not only provides a useful corrective to the historical record but also points to the difficulties inherent in reconstructing an accurate account of session musicians’ contributions to popular music.

The Legacy of Session Musicians

Session musicians have been a staple of the American music industry nearly since the beginning of recording. As James P. Kraft has demonstrated, advances in phonograph and radio technology during the 1930s resulted in a loss of jobs for local musicians around the country; these same forces, however, created a demand for a new professional class of highly skilled musicians in major media centers, such as New York and Los Angeles.Footnote 3 There, these musicians would perform on radio broadcasts, commercial recordings, and film soundtracks—all of which would then be exported across the country. By the 1940s, session musicians had become pervasive within the industry; according to Rob Bowman:

In the postwar era, all major genres of North American popular music, including jazz, country, pop, rock, rhythm and blues, and blues, increasingly utilized session musicians. In Nashville, New York, Los Angeles and eventually Toronto, the session musician scene became highly competitive, with certain players clearly considered the first, second, or third choice on their instrument for sessions in a given style.Footnote 4

The use of session musicians expanded throughout the 1950s and 1960s to not only include major labels in big cities but also smaller labels whose music was produced at regional recording studios, such as Chess Records in Chicago, J&M Studio in New Orleans, Motown's Hitsville U.S.A. in Detroit, Stax Records in Memphis, and FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

Although numerous academic studies have effectively analyzed the studio as a creative space, reclaiming the role of the producer and engineer in the artistic process, less attention has been paid to the people who physically create the sounds within that space.Footnote 5 This critical gap is largely due to the fact that most session musicians did not receive explicit recognition for their work.Footnote 6 Regardless of their individual talent or sonic identity, the recording industry treats session musicians not as artists in their own right but rather as day-to-day employees—as small cogs in the larger record-making machine. This conception has, in turn, allowed critics and historians to repeatedly attribute the success of session musicians’ efforts to others (producers, songwriters, etc.), who can be more easily depicted as mastermind auteurs. Although some scholars have attempted to reclaim their contributions, the inherent anonymity of these musicians has led them to be chronically underrepresented in popular music histories.Footnote 7

This is not to say that session musicians were necessarily exploited by the music industry. For many, session work provided a steady income, and within the confines of the studio itself, these musicians were well respected for their abilities. Still, as popular music has been re-valued over the last century, many of these musicians have come forward seeking wider recognition.Footnote 8

When Motown was established in 1959, the expectation that their session musicians would be anonymous was part of a long-established music industry norm. Reflecting the automotive industry practices of the company's Detroit birthplace, Gordy established Motown's entire creative process as an “assembly line” in which all of their employees (songwriters, artists, producers, musicians, arrangers, etc.) performed a clearly delineated function.Footnote 9 Gordy's goal was for Motown to function as a smoothly oiled machine, consistently producing well-crafted singles with widespread commercial appeal. Session musicians played an indispensable role in this vision.

By the time Motown reached massive success in 1964—most notably with a string of five consecutive #1 hits for the Supremes (“Where Did Our Love Go,” “Baby Love,” “Come See About Me,” “Stop! In the Name of Love,” and “Back in My Arms Again”)—the company was relying upon a stable coterie of Detroit session musicians, who called themselves the Funk Brothers. As biographer Allan Slutsky has described them:

The Funk Brothers were one of the most disciplined and creative hit machines of all time. … With Motown constantly expecting them to crank out three to four songs during every three-hour session, they must have been doing something right or they wouldn't have stuck around as long as they did. (An average work day consisted of 2 of these three-hour sessions, and on occasion, as many as three or four.) Motown's producers and songwriters threw material at them at such a staggering rate that the musicians often had no idea what the songs were called, or who they were intended for.Footnote 10

Beyond their ability to work quickly and diligently, these musicians were specifically able to generate material that sounded good on record (i.e., that was simultaneously catchy and blended well in a mono mix)—a learned skill that should not be taken for granted. They knew their instruments and they knew how best to use them within a studio environment.

The most important of the Funk Brothers was likely electric bassist James Jamerson (Figure 1), whose inventive musicality and idiosyncratic technical abilities led him to craft unique, propulsive bass lines that were central to the Motown Sound. In fact, Jamerson was considered so indispensable to the company that he was one of the first musicians they put on exclusive retainer, reportedly earning him $250 per week in 1964 and $1,000 per week by 1968 (or approximately $7,000 per week today).Footnote 11

Figure 1. James Jamerson, ca. 1977. Courtesy of Jon Sievert/humble archives

What made Jamerson so important to Motown was his ability to improvise memorable, melodic bass lines with little direction. As he later described,

[Producing/songwriting team] Holland-Dozier-Holland would give me the chord sheet, but they couldn't write for me. When they did, it didn't sound right. They'd let me go on and ad lib. I created, man. When they gave me that chord sheet, I'd look at it, but then start doing what I felt and what I thought would fit. All the musicians did. All of them made hits. … I'd hear the melody line from the lyrics and I'd build the bass line around that. I always tried to support the melody. I had to. I'd make it repetitious, but also add things to it. Sometimes that was a problem because the bassist who worked with the acts on the road couldn't play it. It was repetitious, but had to be funky and have emotion.Footnote 12

This proved to be a winning formula. Jamerson, in conjunction with the rest of the Funk Brothers—most especially drummer Benny “Papa Zita” Benjamin—improvised bass lines that became the backbone of over a hundred Motown hits.Footnote 13

Yet although they are the most celebrated today, the Funk Brothers were not the only session musicians that Motown employed. In fact, although it is omitted from most Motown histories, the company had begun recording in Los Angeles in the early 1960s. As Flory explains,

Headed by Marc Gordon and Hal Davis, Motown's California-based recording and publishing office opened in 1963 and collaborated with the company's Detroit headquarters to produce hundreds of recordings. Motown's first activity on the West Coast included sessions for records like Little Stevie Wonder's “Castles in the Sand” and Brenda Holloway's “Every Little Bit Hurts.” … Virtually all of Motown's most important artists recorded at least a few tracks in Los Angeles during the mid-1960s.Footnote 14

On these West Coast sessions, Motown utilized a Los Angeles–based collective of session musicians, known today as the Wrecking Crew. In a departure from Motown's standard practices in Detroit, these session musicians were free to record for any label. Also, unlike the Funk Brothers, their work fell under the purview of the highly regulated Local 47 Chapter of the American Federation of Musicians, meaning that their work was far more regularly documented.Footnote 15

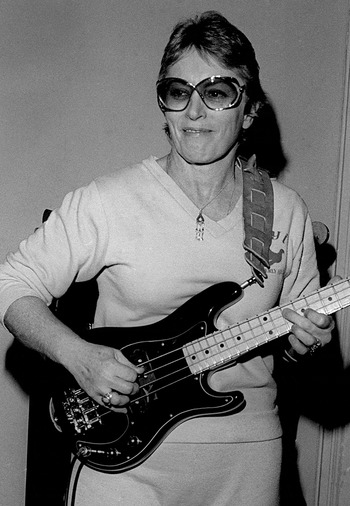

Motown's preferred electric bassist on the West Coast was Carol Kaye (Figure 2). Kaye began working as a session musician in 1957 and has since played on thousands of sessions, making her one of the most-recorded bassists of all time. Today, she is most remembered for her work with the Beach Boys, playing bass, for example, on “Help Me Rhonda” (1965), “Good Vibrations” (1966), and the entire Pet Sounds album (1966). She also supplied the bass lines to hits such as The Monkees’ “I'm a Believer” (1966), “Theme from Mission: Impossible” (1967), Joe Cocker's “Feelin’ Alright” (1969), Barbara Streisand's “The Way We Were” (1973), and many more. Working in the world of Los Angeles session musicians, Kaye's career depended on her ability to play in diverse musical styles. Her credits thus vary widely, from jazz and rhythm and blues, to country, rock, and pop (not to mention her work in film and television). Regardless, her process was not all that different from Jamerson's. Here, for example, is how she describes recording Glen Campbell's “Wichita Lineman” (1968):

“Wichita Lineman” is one of my favorite records. I got to improvise most of my bass line on that. … We just had a chord chart to work from and they were trying to come up with a lead-in line… so they asked me to “start it with a pickup on bass” … and what you hear is what I invented. … I mostly aimed for the roots/chordal notes, making up lines. … It sounds arranged, but it wasn't arranged. … You keep the bass line simple when the tune is especially good and add a few nuances here and there.Footnote 16

Figure 2. Carol Kaye, ca. 1982. Courtesy of Jon Sievert/humble archives

As a female musician in the male-dominated environment of the Los Angeles recording scene, Kaye faced distinct challenges, including verbal and sexual harassment.Footnote 17 Yet in many other ways, Jamerson and Kaye had very similar careers: They both got their start as gigging jazz musicians and fell into session work as a way to supplement freelance incomes; they both started out on different instruments—Jamerson originally played upright bass and Kaye originally played electric guitar—before switching to electric bass in the early 1960s;Footnote 18 they both considered themselves first and foremost jazz musicians and found recording pop songs to be a bit uninteresting but a good way to support their families;Footnote 19 and even though they both seemed unconcerned about their lack of credit while the Motown checks were arriving regularly, by the time their careers were waning each wanted the recognition they felt they deserved.Footnote 20

Today, Jamerson is rightly centered at the heart of Motown history, but Kaye's role at the company has been almost entirely expunged. It is easy to assume that this omission stems from her position as a white woman, but Motown's racial and gender dynamics were complex. For example, Motown was one of the first labels to have women work as company executives, with Berry Gordy hiring his sisters to manage internal operations—Loucye Gordy Wakefield was an early vice president at the company, and throughout the 1960s, Esther Gordy Edwards variously served as Motown's senior vice president, corporate secretary, and chief financial officer. Through Valerie Simpson, Motown was also one of the first labels to have women work as producers.Footnote 21 Furthermore, although Motown (and rhythm & blues in general) is often understood as a specifically black enterprise, the company did have a number of white employees, both in sales positions and as part of their in-house studio band. For example, white guitarist Eugene Grew played on Barrett Strong's “Money (That's What I Want)” (1959), one of the first songs recorded at Hitsville, and the Funk Brothers regularly featured white musicians, such as guitarists Joe Messina and Dennis Coffey and later bassist Bob Babbitt.Footnote 22 When it comes to Motown's West Coast sessions, many of those players—not just Kaye—were white.

Although Kaye's race and gender may be contributing factors, her exclusion is more directly the result of shoddy record keeping, disputes over credits, the mythologizing of Jamerson's bass style, and an after-the-fact critical discourse that has overly simplified Motown history.

Contested Credits

In 1971, Kaye published her method book Electric Bass Lines No. 4.Footnote 23 Released during Jamerson's lifetime, Kaye's book featured multiple transcriptions of Motown bass lines, including the Supremes’ “Back in My Arms Again” (1965), Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell's “If I Could Build My Whole World Around You” (1967), Brenda Holloway's “You've Made Me So Very Happy” (1967), and Stevie Wonder's “I Was Made to Love Her” (1967), all of which she claimed as her own.Footnote 24 Many of these claims were later disputed—albeit tacitly—when Allan Slutsky (writing under his pseudonym, “Dr. Licks”) published his own electric bass method book, Standing in the Shadows of Motown, in Reference Slutsky1989.Footnote 25 Based primarily on interviews with surviving members of the Funk Brothers, Standing was a posthumous celebration of Jamerson's life and musical style, and it explicitly situated Jamerson both as a key architect of the Motown Sound and as the person responsible for Motown's most iconic bass lines.

Kaye, who is not mentioned in Standing in the Shadows of Motown, brought a defamation suit against Slutsky in October 1999, claiming that his book damaged her reputation by falsely crediting some of her bass lines to Jamerson; it was Kaye, her complaint alleged, who played bass on the Supremes’ “Baby Love” (1964), “You Can't Hurry Love” (1966), and “Reflections” (1967); the Four Tops’ “(I Can't Help Myself) Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch” (1965) and “Bernadette” (1967); and “numerous other classic Motown recordings.”Footnote 26 After Kaye dismissed the lawsuit, Slutsky addressed her allegations in a lengthy online rebuttal, claiming that, at most, she only played on album cuts and re-recorded versions: “THEY WERE NOT THE ORIGINAL SINGLES AND THEY WERE ALL PLAYED DIFFERENTLY AND ARRANGED DIFFERENTLY FROM THE ORIGINAL SINGLES.”Footnote 27 To this day, he contends that Kaye never played on any important hits and that her claims are simply lies.Footnote 28 Kaye similarly maintains her account of the facts, and since 2001, her personal website has listed twenty specific Motown hits on which she claims to play bass.Footnote 29

No one disputes that Kaye was part of Motown's West Coast recording operations. In fact, Lester Sill, the former head of Motown's publishing company Jobete Music, wrote a letter to this effect, stating categorically: “To whom it may concern, Carol Kaye has played bass on several Motown hits that were cut between the years 1963 and 1969.”Footnote 30 The difficulty lies in determining the actual extent of Kaye's work for the company, which is further confounded by Motown's idiosyncratic, assembly-line process itself.Footnote 31 As Flory explains, “Some records were created completely in California (including backing tracks and overdubs), and others began there as band tracks and were later taken to Detroit (or other locations) for vocal dubbing or mixing.”Footnote 32 Reconstructing an accurate account of whether it was Kaye's or Jamerson's performance that actually made it onto the released version of a song is thus a painstaking endeavor.

The New Evidence

For decades, it seemed as though nothing could conclusively settle this debate. However, forty-five years after Kaye's claims first appeared in print, two new pieces of evidence have come to light: Kaye's personal session log and Motown's long-buried Los Angeles Musician's Union contracts from the 1960s.Footnote 33 Cross referencing these sources against each other, as well as against Motown's master tape catalog, provides a much clearer, if no less complicated, picture of Kaye's work for the company.Footnote 34

Figure 3 is a typical American Federation of Musicians’ B-4 “Phonograph Recording Contract” from the period. The employer's name—in this case, Motown Records—is listed at the top right, followed by the local Musician's Union chapter number, the date, the session leader, the studio, the pay rate, “titles of tunes,” etc.; beneath that (not pictured) would be a list of all the musicians who played on the session. As with all of these contracts, however, we cannot take this information at face value. For instance, the date here is listed as August 12, 1966, but—judging by Kaye's session log—this particular session appears to have taken place the day before, on August 11. There are also far more extreme examples of date altering, where the company falsified contracts either to avoid late fines from the union or to legitimize an off-the-books session that had been conducted months prior.Footnote 35 This is occasionally true for Motown's Detroit B-4 contracts as well; for instance, Detroit contracts for the Supremes’ songs “Baby Love” and “Come See About Me” are dated March 10, 1965, but both of these songs had been commercially released months earlier.Footnote 36

The session leaders are listed here as H. B. Barnum, Gene Page, and (parenthetically) the Lewis Sisters. Barnum and Page, along with Frank Wilson and Ernest Freeman Jr., were the most common leaders on Motown's West Coast sessions from this era. The mention of the Lewis Sisters is notable, but misleading: Although Helen and Kay Lewis did have their own small career as a Motown act, the indication here actually denotes that they provided the session's scratch vocals, acting as stand-ins for the eventual singers in Detroit.Footnote 37

As is often the case, the “Title of Tunes” section contains the most misleading information. Some contracts provide accurate titles, and others provide incorrect titles or none whatsoever. The titles in Figure 3 contain several of these inconsistencies: “Our Love” was actually a version of “Old Love (Let's Try Again)” that was intended for the Supremes but was never released; there is no song called “Come Along” or anything like it in the Motown master tape catalog; “I'm Ready for Love” is properly listed, and was a #9 hit for Martha and the Vandellas; and “Number One (New Key)” was the working title of the song “Love is Here and Now You're Gone,” a #1 hit for the Supremes. Furthermore, there is much information not included in these contracts—most notably here that this session was actually produced by famed Motown songwriting team Holland–Dozier–Holland, who were in Los Angeles at the time working on a film project.Footnote 38

Figure 3. Top Half of Motown B-4 Contract, dated August 12, 1966. American Federation of Musicians Local 47

Although these contracts may be unreliable on their own, when checked against existing sources, they provide a wealth of new information that can go a long way toward filling in gaps in the historical record.Footnote 39 Here is what the evidence now shows: from contracts dated between June 1964 and June 1971, Kaye played on more than 175 songs for the label (detailed in Appendix A), approximately 40 percent of which have never been released. Kaye's personal log (detailed in Appendix B), however, lists Motown sessions dating as early as February 1964 and also includes 82 off-the-books sessions for which there are no contracts.Footnote 40 Although Kaye primarily recorded material for the Supremes, she played on sessions for nearly every major Motown act—including Barbara McNair, Brenda Holloway, the Four Tops, Martha and the Vandellas, Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles.

Kaye definitively appears on the A-Side of six Motown singles (Table 1), including four Top 40 hits: the aforementioned “I'm Ready for Love” (1966) and “Love is Here and Now You're Gone” (1967), the Supremes’ “In and Out of Love” (1967), and Brenda Holloway's “You've Made Me So Very Happy” (1967); she additionally appears on at least four B-Sides.Footnote 41 From aural and anecdotal evidence, we can also reasonably infer that she played on the Supremes’ last #1 hit “Someday We'll Be Together” (1969).Footnote 42 Additionally, she appears—at least partially—on seventeen hit albums, including I Hear a Symphony (1966), The Supremes A’ Go-Go (1966), The Supremes Sing Holland-Dozier-Holland (1967), and Diana Ross & the Supremes Join the Temptations (1968). She is most heavily and consistently featured on Motown's numerous LPs of Broadway standards such as the Four Tops’ On Broadway (1967), The Supremes Sing Rodgers & Hart (1967), the Temptations’ In a Mellow Mood (1967), and the Supremes/Temptations’ On Broadway album (1969).

Table 1. Motown A-Sides on which Kaye appears.

Revisiting the Controversy

These contracts clearly contradict many of Kaye's critics. Contrary to what Slutsky argued, she did play on original hit singles; yet they also do not corroborate many of Kaye's own claims. As detailed in Tables 2–4, Kaye's personal website maintains that she played on one album and twenty singles for Motown—including seven #1 hits by the Supremes (the group had just twelve in total).Footnote 43

The contracts reveal that six of the songs Kaye claims are actually re-recordings (Table 2). For instance, she claims to have played on the Four Tops’ hit version of “I Can't Help Myself” (1965), when she actually played on a later version that appeared on The Supremes A’ Go-Go.Footnote 44 Re-recording was a common practice at Motown—one act would have a hit and then the label would have a different act quickly record a new version of it for release on LP. This was usually done for practical reasons: first, it gave the company more material to fill out an entire album—a whole new release (and a more expensive one at that) could easily be constructed by pairing a few established hits with re-recorded filler; second, because Jobete Music owned these songs, the company made money off of each subsequent re-recording. One of the common assumptions among Kaye's critics, including Slutsky, was that she played on the Supremes/Temptations’ 1968 TCB NBC TV special, and it was there that she re-recorded many of the classic Motown bass lines she claims as her own. This, it turns out, is not entirely accurate: the contracts show that Kaye was not a part of the actual TCB special, but instead played bass on Diana Ross & The Supremes Join the Temptations (1968)—an album pre-recorded and released to coincide with the special. Five of the twenty songs that Kaye claims come specifically from this album.Footnote 45

Table 2. Motown singles that Kaye claims which are re-recordings.

Table 3. Motown singles Kaye claims on which she likely does not appear.

Table 4. Motown singles Kaye claims on which she definitively appears.

For another seven of the songs that Kaye claims (Table 3), evidence suggests that Kaye's participation is unlikely. In support of Slutsky's legal defense, Motown songwriter Brian Holland signed an affidavit attesting that it was James Jamerson who performed on “Bernadette,” “Reach Out,” “I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch),” “You Keep Me Hangin’ On,” “Standing in the Shadows of Love,” “Reflections,” “Baby Love,” “Back in My Arms Again,” “Come See About Me,” and “You Can't Hurry Love.” Songwriter Hank Cosby similarly provided an affidavit definitively stating that Jamerson appeared on “I Was Made To Love Her.”Footnote 46 For the rest of the songs in Table 4, there is either a Detroit B-4 for the song or the actual recording date does not match up to Kaye's personal log.Footnote 47 This does not rule out the possibility that Kaye could have re-recorded these songs at some point (e.g., as part of a backing track for television performances), it simply means that I have found no direct evidence of it. All of these seven songs were Top 10 hits on the Billboard Hot 100, and four of them went to #1.

That leaves seven songs and one album (Table 4) that Kaye claims which can solidly be attributed to her. It is noteworthy that she tacitly admits that three of these are actually re-recordings—claiming to have played on the Supremes’ and the Temptations’ versions of “I Second That Emotion,” “Ain't No Mountain High Enough,” and “You're All I Need to Get By”—and not the original hit versions (by, respectively, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles and Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell). Of the five hit singles I attribute to her, Kaye claims only three: “Love is Here and Now You're Gone,” “Someday We'll Be Together,” and “You've Made Me So Very Happy” (there is no mention of “I'm Ready for Love” or “In & Out of Love”).

Given that Kaye only appears on approximately one-third of the songs she claims, how should we interpret her account? Giving her the benefit of the doubt, it is possible to argue that she might not have known that she was “re-recording” a given track or that hers was not the hit version of a particular song. As previously mentioned, some of these recordings were cut using scratch vocalists and even Motown's Detroit musicians often did not know for whom songs were actually intended. Furthermore, Motown's assembly line process meant that every person was assigned a single role, and as a session musician, Kaye was not involved in or privy to any other part of Motown's operations.Footnote 48 This is also why she might come away from the experience thinking that she was Motown's most important bass player; in fact, the man in charge of Motown's West Coast operations, Hal Davis, was known in Los Angeles as “Mr. Motown,” much to Berry Gordy's amusement.Footnote 49 Also, because she has literally played on thousands of sessions, it is more than likely that she is simply misremembering.

It is easy to see why Jamerson supporters continue to doubt Kaye: many of her claims are, at best, misleading; at worst, they are outright fabrications (for example, there is no evidence that she played on any of the seven songs specifically cited by her lawyers in her defamation suit against Slutsky). Nevertheless, Kaye cannot simply be dismissed outright.

The Style Debate

This new evidence would likely do little to sway Kaye's critics, because, although “hits” are the standard by which they measure success, the key component of this controversy is actually style. In the years since his death, Jamerson has been mythically recast as the great pioneer of the electric bass; Ed Friedland, former senior editor of Bass Guitar magazine, has gone so far as to describe him as: “[T]he man who started it all. Before him, the electric bass was an untapped reservoir of potential. Often poorly recorded and played without flair, it had not yet become a force in music. All that changed when Jamerson picked up the instrument.”Footnote 50 For those invested in this narrative, Jamerson is seen as the primogenitor of modern electric bass playing—his style is virtuosic, unique, and unquestionably his own invention.Footnote 51 Jamerson supporters thus see Kaye's claims as an affront to his legacy, and this perceived disrespect has led many (including Slutsky) to reject even the possibility that she appears on any of Motown's biggest hits.

Their arguments primarily rely on the differences between Kaye's and Jamerson's techniques and equipment. Jamerson played a stock Fender Precision Bass, including the original foam mute in his bridge that deadened the sound of his strings, and he played La Bella flat-wound strings, which he almost never changed. His action (the space between the strings and the fretboard) was unusually high, and he played solely with his index finger, a holdover from his time as an upright bassist. Sonically, the unique timbre of his bass was the result of Motown's recording process, in which Jamerson's bass was recorded directly into the mixing console; when he pushed his bass's electric signal, this direct-input (DI) process caused his bass to often sound overdriven and slightly distorted. Kaye, by contrast, played a muted Fender Precision Bass, but she played with a pick and recorded through a miked amplifier; her bass sound is thus produced using a method that is fundamentally distinct from Jamerson's. In practice, however, these differences are not always easy to hear.

Kaye's recorded output with Motown illustrates the diverse material the company recorded on the West Coast, including both pop singles and collections of Broadway standards. Each song's overall arrangement dictated Kaye's particular style of bass playing. As such, her bass lines can broadly be grouped into three categories: new creations, general allusions to Jamerson's style, and verbatim re-recordings of Jamerson material. All three reveal notable stylistic differences and are therefore useful for investigating this debate.

As mentioned earlier, Kaye played on a number of re-recorded versions of classic Motown songs. In these contexts, Kaye was often given a transcription of (or a loose approximation of) Jamerson's original bass line to work from. In her autobiography, she explicitly described one such situation: discussing her re-recording of “Ain't No Mountain High Enough” for Diana Ross & the Supremes Join the Temptations (1969), Kaye writes that,

I remember reading the written bass part, actually a copy of Jamerson's part he originally cut with Marvin Gaye and Tami [sic] Terrell on “Ain't No Mountain High Enough.” It was many pages of music. … While turning the music page over on ‘the’ take, my music fell about at the key change and I had to improvise after glancing quickly to [conductor] Gil [Askey], who didn't stop—he kept waving to keep going so I did.Footnote 52

Sonically, on each bassist's interpretation of “Ain't No Mountain High Enough,” the timbres of their instruments are noticeably distinct; yet they are not as radically different as Kaye's critics tend to describe. Instead, Kaye's felt mute and picking style conceal many of the aforementioned technical differences between her and Jamerson.Footnote 53 Listening today, the most obvious differences between the two musicians concern their approaches to attack, improvisation, and rhythm, with Kaye playing more aggressively on top of the beat and more often playing extended passages of eighth notes.Footnote 54

Kaye's work for Motown also included a more general pop/rhythm and blues style. This occasionally took the form of direct imitation of Jamerson, such as in “I'm Ready for Love” by Martha and the Vandellas; Kaye's bass line to this song—although not a verbatim transcription—is an obvious allusion to Jamerson's playing on the Supremes’ “You Can't Hurry Love” (1966).Footnote 55 Other times, Kaye was given more latitude to invent her own bass lines. For instance, to accompany Brenda Holloway's “You've Made Me So Very Happy,” Kaye improvises a nuanced, propulsive line that is distinctly her own and yet still fits perfectly within the Motown oeuvre. An even more extreme example can be heard in her performance on “My Girl” from the album Time Out for Smokey Robinson & The Miracles (1969); eschewing Jamerson's famous three-note motive from the Temptations’ original 1964 hit recording, Kaye improvises a funkier, more dynamic bass line that supplies a substantially different groove for the song. Kaye's contributions to Motown's albums of Broadway standards are similarly notable because, although they place her within a different stylistic context, her bass lines are still just as prominent in the overall mix (see, for example, “Mountain Greenery” from The Supremes Sing Rodgers & Hart).

Kaye contributed to and innovated within the Motown bass style, even if she did not invent it. When her critics argue that she couldn't possibly have played on these songs or that her timbre or technique make her immediately stand out as an outsider, they do her a disservice. They forget that Kaye worked in the cutthroat scene of Los Angeles session musicians. Her livelihood was predicated on her ability to act as a chameleon, playing whatever sound or style was needed on a given session. That is not to say that there were not important differences between Kaye's and Jamerson's approaches to the bass, it merely means that the recording itself is not always enough to conclusively identify either musician. This latter point can clearly be seen in the example of “Love is Here and Now You're Gone”—even though the contracts show that it is definitively a Kaye recording, Slutsky included a transcription of its bass line in Standing in the Shadows of Motown, incorrectly attributing it to Jamerson.Footnote 56

Conclusion

When James Jamerson died in 1983, he was a completely unknown figure.Footnote 57 Thanks largely to Slutsky's book and the subsequent 2002 Standing in the Shadows of Motown documentary, he has been rescued from obscurity, and today he is correctly recognized as an innovative bassist and a key figure in Motown history.Footnote 58 However, in the years since his death, the mythology surrounding Jamerson has also grown exponentially, to the point that any conflicting narrative is now immediately suspect. Kaye has likewise been the subject of both a book and a documentary (Kent Hartman's Reference Hartman2012 Wrecking Crew book and Denny Tedesco's Reference Tedesco2015 Wrecking Crew film), yet her role at Motown—even if it is smaller than she might claim—has been erased completely.Footnote 59

The Kaye/Jamerson controversy is a particularly complicated case study, one that could have been easily avoided had Motown credited their session musicians (or at the very least, kept better internal records). But that was not the reality of their working environment. Like nearly all other labels at the time, the company simply saw their musicians as in-house employees who were already being compensated for their work. As this music has since become enshrined as an important cultural artifact, the uncertainty surrounding who actually played on these recordings has created a vacuum that has bred wild speculation. One of the most important lessons from Kaye's story is that such speculation can lead to problematic narratives that often reproduce preexisting bias. In the absence of tangible evidence, fans, critics, and historians have simplified and mythologized Motown history to the point that Motown can only mean Detroit and can only mean Jamerson. This mythology in turn has become all consuming, even, as the evidence now shows, when it is wrong.

Slutsky concluded his rebuttal of Kaye's claims as follows:

History is a funny thing. Once something is published, whether in magazines, books, or on the internet, it becomes a part of history. As the witnesses to the original events die out, false, revisionist versions of history tend to confuse and even, in some instances, destroy the real facts for future generations. … To those of you who keep pushing Carol's Motown agenda, I say this: You are taking that legacy away from James, you are taking it away from history, and you are taking it away from the bass lore that should be handed down to generations of future bassists. Carol has enough credits. Let James keep his.Footnote 60

Although his discussion of “revisionist history” may seem a bit ironic, his goal is clear: he wants to preserve the unimpeachable mythology of James Jamerson. But acknowledging Kaye's contributions does not diminish Jamerson's significance—rather, it simply validates the work of a fellow anonymous session musician. Kaye played on original hits by the Supremes, Martha and the Vandellas, and Brenda Holloway, and she deserves recognition for her work.

Even with these new sources, there is still much that is left unresolved, and for many recordings, we may never know exactly which musicians are performing. Nonetheless, it remains vitally important that historians carve out a space for Carol Kaye and the thousands of other session musicians like her, who both literally and symbolically were never given their proper credit. For many in this unlucky club, there are no buried contracts waiting to be found, no evidence outside of fading memories—too much time has passed, and too few records have been kept. Yet these people were an integral part of the music we listen to and study, and if for no other reason, their stories deserve to be told.

Appendix A: Detailed Record of Every Motown Los Angeles Musician's Union Contract That Lists Kaye as a Performer

(Source: Los Angeles Local 47 Musician's Union)Footnote 61

Appendix B: Annotated Record of Every Motown Entry from Kaye's Personal Session Log

(Source: Carol Kaye, Studio Musician, 60s No. 1 Hit Bassist, Guitarist, Burbank Printing, Reference Kaye2016)Footnote 64