In 1938 Rudy Vallée welcomed Tin Pan Alley lyricist Irving Caesar as a recurring guest on the NBC radio program The Royal Gelatin Hour. He introduced Caesar as a “great songwriter and the creator of hits by a hundred, whose fancy turns … to a new and important type of song.”Footnote 1 When asked to describe the new children's songs that he wrote with Gerald Marks, Caesar broke into song. He sang an introduction that addressed the intended audience of “Johnny B. Careful” and “Mary B. Ware.” Caesar and Marks aimed to prevent accidents and help children develop the cautious habits implied by these names. The final stanza of the introduction states,

Don't talk to strangers and don't play with matches;

These new little songs know the right from the wrong,

So learn while you're singing, and sing while you're learning,

And you will grow up to be healthy and strong.Footnote 2

The lyrics of these songs described domestic, playtime, and traffic safety lessons, presenting music as a pedagogical strategy for safety education. However, what is one to make of the performance of these educational children's songs on a commercial radio show with a broad audience?

By investigating Caesar's segments on The Royal Gelatin Hour and their associated sheet music, this article examines the role of children's music on the radio during the 1930s. Placing these segments and songs in their historical context, I show how they both portray and challenge citizenship and community roles with regard to age, gender, and race. After unpacking The Royal Gelatin Hour, the relationship between safety and citizenship education, and the use of music in safety education, I describe the standard of parenting presented during Caesar's segments. Then, using one of Caesar's segments as a case study, I examine the depiction of boyhood and race. In this case study, I trace the adaption of the safety patrol, a popular extracurricular activity, to the radio and explore the segment's capacity to create a club for listeners. Through unpacking the construction of childhood and parenthood in these segments, this article has three main aims. First, it addresses the relationship between children and the media and early uses of media as a parenting tool. Second, it examines the synergy of and tensions between education and the commercial interests of the music industry and sponsored radio programs. Third, it expands our understanding of the use of music to convey societal duties in everyday life as they shift throughout the life course.

Radio and Community

In the 1930s, Americans negotiated the role of radio in society. As David Goodman argues, American radio was unique in that it addressed “the productive tensions between entertainment and public service roles, and the commercial and the national faces of the networks.”Footnote 3 Moreover, by welcoming the outside into one's home, the medium created an “intimate public” and a sense of national unity through synchronous experience.Footnote 4

Scholars such as Michele Hilmes have examined the socio-cultural dimensions of American radio, addressing the radio's unique affordances by adapting concepts such as Benedict Anderson's “imagined communities.”Footnote 5 Hilmes unpacks the listener's relationship to the radio, discussing how the radio connects listeners through shared experiences. She examines radio as a process of meaning-making to address the implications of “print capitalism” and nationalism by tracing an analogous set of processes to Anderson's analysis of the newspaper.Footnote 6 She describes the radio as,

a system of productive relations driven by…advertising; a technology of communications…even more capable of negotiating not only the linguistic but the ethnic and cultural diversity brought about by the transformations of the modern age; and…a machine for the circulation of narratives and representations that rehearse and justify the structures of order underlying national unity.Footnote 7

Hilmes addresses the unique affordances of radio and the tension latent in reconciling the portrayal of national identity with the representation of difference.

However, radio's relationship to communities can be extended by considering listening practices and the intermedial dimensions of programs. An imagined community is reinforced by encountering someone else in one's daily life who consumes the same media. Listening to a program with others or overhearing someone else's radio creates a shared listening experience.Footnote 8 Material traces of one's engagement further substantiate community ties. In the case of the newspaper, encountering or possessing copies imparts physical artifacts of belonging, regardless of actual reading practices. In the case of the radio, encountering or possessing a premium—a prize that listeners could obtain by sending in box tops from the sponsor’s products—advertised on the radio imparts a physical artifact of one's belonging to a community of listeners, regardless of actual listening practices. These premiums sustain ties to a program after it concludes. They signify listenership not only to the medium of radio, but also to specific programs, such as The Royal Gelatin Hour.

Furthermore, a radio listener's interpretation of community is contingent on numerous factors. While one cannot make categorical claims regarding radio listeners, the relationship between a listener and a community involves a variety of factors such as their listening practices and preferences, their immediate listening contexts, and the messages portrayed on the radio program. For example, in the group listening context of children and their caregivers, the content that children are exposed to and retain depends on negotiating their preferences and levels of attention with those of their caregivers. As I will demonstrate, the creators of The Royal Gelatin Hour prompted listeners to attend to specific communities. They pitched Caesar's segments to families and intertwined an educational message of accident prevention with a commercial message to purchase the sponsor's products.

The Royal Gelatin Hour

The Royal Gelatin Hour was a foundational network radio program broadcast by NBC from 1929 to 1939.Footnote 9 With both its innovative use of Rudy Vallée as an emcee and showman and the direct involvement of an advertising agency in its development, it became “the most influential variety show in the history of the medium.”Footnote 10 According to contemporaneous audience research, it was one of the most popular programs; between 15.7 and 39 percent of homes surveyed reported listening to the program.Footnote 11 While this provides evidence in favor of the show's popularity, audience research from the 1930s demonstrated a bias toward selecting audience members from urban households that were middle-class or higher.Footnote 12 Additional research on the radio preferences of children elicited mixed results, with some studies concluding that the program was the eleventh most popular and others reporting that the program was not among the most frequently mentioned favorite programs.Footnote 13

Paramount to the show's construction and its attempts to appeal to a broad audience was advertising agency J. Walter Thompson (JWT), which developed the program on behalf of Standard Brands.Footnote 14 Advertising agencies typically controlled their programs, providing the advertiser with the potential to increase awareness of their products, embed advertisements into dialogue, and associate a program's content with a product.Footnote 15 To appeal to a range of tastes, The Royal Gelatin Hour had a variety show format, traversing segments such as musical numbers, comedic sketches, and dramatic excerpts.Footnote 16 Though Vallée was framed as the show's central talent scout and creator, JWT transitioned Vallée to a master of ceremonies role by 1932.Footnote 17 As one executive for JWT remarked in an oft-quoted statement, Vallée “doesn't write one word of the script. All of the things about how he first met these people, etc., we make up for him.”Footnote 18 This productive fantasy ushers the listener into an intimate community comprised of Vallée, his guests, and the listener.

Children's Safety

Irving Caesar was one such guest, depicted as one of Vallée's prized finds during the show's segments about safety in 1938.Footnote 19 By this time, children's safety education was a well-established topic connected with citizenship, nationalism, and the negotiation of commercial interests and public education.Footnote 20 For example, Executive Secretary for the Education Division of the National Safety Council (NSC) Idabelle Stevenson remarked, the American “mortality rate from accidents [was in the late 1920s] almost twice that of any European country and one-fourth greater than that of Canada.”Footnote 21 These reports point to the importance of accident prevention so that America could compete with other countries in terms of labor force and quality of life.

Among the deadliest concerns was the changing function of the streets brought about by the automobile. What was once a shared space for play became a source of danger.Footnote 22 Reflective of what Viviana Zelizer identifies as the “new sacred value of child life,” the yearly deaths of thousands of children due to traffic accidents spurred an increase in accident prevention efforts during the first decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 23 As the Subcommittee on Safety Education in Schools for the White House Conference on Child Health and Protection stressed, “[t]he rapid increase in the number of motor vehicles, the congestion of … cities, the growth of various forms of transportation … and many other characteristics of … industrial civilization” were all hazards that necessitated the development of safe habits.Footnote 24 Statements such as these reinforced that changes to daily life required a robust safety education program to prepare one for their environment.

Safety education had three central components: First, a knowledge of a set of hazards prevalent in one's community; second, guidelines to address these hazards; and third, an adherence to care ethics which relied on thinking beyond oneself and about the safety of others.Footnote 25 Each of these components functioned together to create proper citizens, preparing children to avoid danger and “control [their] environment now, and as an adult later on.”Footnote 26 Contributing to these efforts, educators used songs to help children develop outlooks in line with the slogan “A.B.C. Always Be Careful.”Footnote 27 The phrase “safety song” gained traction in the 1920s to describe songs that taught accident prevention lessons.Footnote 28 Safety songs were performed for various occasions, including parent–teacher association meetings and demonstrations.Footnote 29

A “jingle” written by a second-grade class from Concord, New Hampshire, exemplifies the importance of multisensory awareness and demonstrates the place of safety and the arts in the school curriculum.Footnote 30 The students and their teacher wrote an acrostic poem with the word “green,” as in the green signal of a traffic light. They provided the following for the two E's,

E is for eyes

To help you be wise.

E is for ear—

The autos to hear.Footnote 31

Their jingle encompasses the three components of safety education. First, they identify a safety hazard (i.e., traffic). Second, they provide several strategies to confront the hazard (i.e., seeing changes in their surroundings and listening to automobiles). Third, they attend to the safety of others by publishing their work so that others may also learn about accident prevention.

By the 1930s, educators reflected on safety education and accident statistics produced in the 1920s. They noted that there was only a one-sixth percent increase in child mortality due to accidents, as compared with the 32 percent increase in adult mortality.Footnote 32 However, some educators, such as E. George Payne, expressed frustration with the lack of adult education and commercial involvement in safety education, believing that it was inauthentic and dangerous when laypersons were in charge of safety education.Footnote 33

Constructing the “Safety Songster”

The importance of accident prevention provided the historical conditions for the success of Caesar and Marks's safety songs. Caesar acknowledged the importance of safety education, remarking that “safety has always been next to war the public problem number one” and that in the 1930s, he likely “thought it was public problem number one.”Footnote 34 In 1937 he published Sing a Song of Safety, a book of twenty one safety songs with illustrations by Rose O'Neill and music by Gerald Marks.Footnote 35 Caesar's lyrics educated children on navigating their societal roles. For example, these lessons encouraged children to refrain from skating on thin ice and to remember their name, address, and phone number in case they became lost. Caesar spun the songs as appealing to the modern sentiments of children with playful titles such as “An Automobile Has Two Big Eyes.”Footnote 36

O'Neill's illustrations conveyed the child's role in society by depicting white children at two stages of habit acquisition. First, she depicted children who required protection due to their obliviousness of the songs’ lessons. Second, she depicted children protected by the songs’ lessons. The former portrayed innocent white children performing a state of divine ignorance; they are both in need of and worthy of protection.Footnote 37 The cover of Sing a Song of Safety introduces this framework by depicting a wide-eyed boy and girl who appear astonished by the bevy of messages and guiding hands (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The cover of Sing a Song of Safety. Irving Caesar, Gerald Marks, and Rose O'Neill, Sing a Song of Safety (New York: Irving Caesar, 1937), Betsy Beinecke Shirley Collection of American Children's Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, CT. Words and Music by Irving Caesar and Gerald Marks Copyright (c) 1937 Round Hill Songs, WC Music Corp. and Irving Caesar Music Corp. Copyright Renewed All Rights for Irving Caesar Music Corp. Administered by WC Music Corp. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

O'Neill also juxtaposes the careful child who applies the lessons with the ignorant child who must learn the lessons. For example, the song “Keep to the Right” presents a lesson in pedestrian safety by encouraging one to follow the example of “Johnny Go Right” and keep to the right when they walk. The illustrations contrast two white boys: the orderly “Johnny Go Right” who avoids a collision, and the bewildered “Johnny Go Wrong” who endures an accident (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The depiction of “Johnny Go Right and Johnny Go Wrong.” Caesar, Marks, and O'Neill, Sing a Song of Safety, 34. Keep to the Right Words and Music by Irving Caesar and Gerald Marks Copyright (c) 1937 Round Hill Songs, WC Music Corp. and Irving Caesar Music Corp. Copyright Renewed All Rights for Irving Caesar Music Corp. Administered by WC Music Corp. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

“Johnny Go Wrong” lies on the ground mopping his brow, his mouth agape in befuddlement, his jacket unbuttoned, and hair askew. Conversely, “Johnny Go Right” is well-composed and maintains an immaculate ensemble. He understands his role in society. He monitors those ahead of him, engaging in the act of self-protection. A woman walking in the opposite direction offers him a seemingly approving glance. The use of song lyrics in the image contributes to the picture-book collage. The lyrics caption the images of the boys, and the moral of the safety song—“keep to the right”—is highlighted in large text accompanied by staff notation.

The songs appear as both an educational strategy and a relic of the Tin Pan Alley proclivity for writing novelty songs about current events. Caesar leveraged the vogue of safety education to attract listeners and potential buyers for the songs and increase profits. He constructed a broad marketing strategy to achieve his goal, which was “the sale of one million books,” and he stated that he had “organized a department which ha[d] been constantly promoting the book in the public school systems.”Footnote 38 Caesar corroborated his educational and financial motivation for writing the songs in his oral history when he remarked that he wrote the songs “because [he] thought it would be easy to teach children through song” and he “thought that there would be a market for them.”Footnote 39

Caesar positioned himself as both a pedagogue and a public safety official. He plugged Sing a Song of Safety at a range of venues, including at Columbia Teachers College, safety conferences, department stores, and NBC's presentation for the National Education Association on radio's educational potential.Footnote 40 Through this widespread promotion, the collection was subsequently listed in education bibliographies and generally received positive reviews that praised its “pleasant way of stating a safety problem and suggesting a way to avoid trouble.”Footnote 41 The fusion of Caesar's wholesome image with his business acumen positioned him as a valuable guest for a recurring segment on The Royal Gelatin Hour in 1938.

Royal Desserts and the Family

The Royal Gelatin Hour featured Caesar on twelve consecutive broadcasts beginning on March 24, 1938.Footnote 42 His segments usually included one or more safety songs and a sketch by comedian Tommy Riggs and his elementary-school-aged character Betty Lou. The segments typically concluded with a final performance of a safety song and an advertisement for two premiums: a sheet music copy of a safety song and a cutout of Betty Lou, available to the listener for ten cents and three box tops of Royal Desserts products.

Caesar's segments did not just have the potential to attract children to the program; they also contributed to the show's family-friendly image and fostered a sense of community. Principally, the sheet music and its on-air advertisements constructed parenting standards that aligned with contemporaneous marketing trends. JWT emphasized parental engagement by promoting a communal listening practice among parents and children. During the beginnings of episodes including Caesar's segment, the program implored parents to listen to “make sure your children hear Irving's song tonight.”Footnote 43 During the end of the segment, the program reminded “mothers and fathers” to send in for copies of the songs.Footnote 44 The use of the second person in the appeals to the listener scripts the parent in an active role, outlining their duty to monitor their child's listening.

Print advertisements for Royal Desserts and their competitors portrayed a standard of motherhood. Advertisers acknowledged that women and mothers did most of the retail buying and attempted to recruit white middle-class women as loyal customers.Footnote 45 Emphasizing maternal duty was one print advertising strategy used by Royal Desserts and their competitors in the mid-to-late 1930s. These advertisements often presented a social tableau indicative of a mother's duty to her children or houseguests stating, for example, “[t]hat's why mothers who want pure, wholesome fruit flavors for their children's gelatin desserts are insisting on R-O-Y-A-L!”Footnote 46 This conflates the purported flavor and nutrition of the product with one's duty to one's child, thereby producing an idealized image of motherhood and creating an economy of shame by equating a brand name with good parenting. The implication was that purchasing gelatin desserts from other companies is a mark against a mother's ability to nurture her family.

In contrast to the use of jingles and song lyrics to explicitly advertise a product on the radio, on-air advertisements for The Royal Gelatin Hour's premiums presented a renewed commitment to this economy of shame. As an advertisement on one of the shows claimed, “[s]urely every mother and father will want to join Irving Caesar's great safety crusade by sending for a copy of this safety song.”Footnote 47 Similar to the strategy used in print advertisements, these types of statements prompted parents to conform to a standard of parenthood upheld by an imagined collective of parents that followed the actions portrayed in advertisements.

One segment claimed that the sheet music served “to help mothers teach this safety lesson” in the home, making explicit the gendered labor implied by the premiums.Footnote 48 The advertising strategy encouraged mothers to negotiate with their children to listen to, perform, and retain the songs.Footnote 49 While this strategy partially departed from children's radio programs in the 1930s—which commonly advertised directly to children—it reflected one of JWT's previous advertising strategies, which aimed to convince mothers to motivate their children.Footnote 50 This process leveraged safety education to conflate the value of the sponsor's product (i.e., boxes of Royal Desserts) with a mother's duty.

Boyhood and the Safety Patrol

During the broadcast on May 12, 1938, Caesar invited sixteen boys from Public School (P.S.) 10 in New York City to join him in introducing an extracurricular activity, the safety patrol.Footnote 51 Caesar and the boys performed a skit and a new safety song, “The Safety Patrol March.” As stipulated by its official operation manual, the safety patrol's primary function was “to instruct, direct and control the members of the student body in crossing the streets at or near schools.”Footnote 52 Descriptions of patrol work in newspapers and magazines lauded patrols, attributing a reduction in child traffic accidents in part to their work.Footnote 53

The proliferation of local safety patrols during the first decades of the twentieth century reflected a biopolitical project of citizenship formation. In the 1920s, affiliates of local safety councils and the NSC typically organized patrols, largely supplanting the use of Boy Scout troops as patrol members.Footnote 54 Some local auto clubs also supported safety patrols, and the American Automobile Association (AAA) coordinated support for patrols in 1926 to place blame for accidents on pedestrians rather than on automobiles and drivers.Footnote 55

Patrol members incorporated music in their broader enrichment efforts, including field trips and appearances at parades.Footnote 56 For example, echoing the militarism of regimented enforcement, 11,000 patrol members marched to Henry C. Stephan's “School Safety Patrol March” during one of the AAA's national school safety patrol parades.Footnote 57 Stephan dedicated the piece “by the American Automobile Association to boys and girls who serve on AAA Safety Patrols,” valorizing the service of patrol members and positioning the work of the children under the auspices of the AAA.Footnote 58 In their status as “citizen-child[ren],” patrol members confronted adult labor shortages, contributing to society through peer regulation while demonstrating their potential as future adults.Footnote 59

Though the program's function varied based on the needs of each school, contemporaneous research and accounts corroborate that the group's primary duty was to help students cross the street.Footnote 60 As Rose Mancuso, a fifth grader from Oneida, New York, remarked, the “[patrol boys] have instructions to watch the boys and girls. The patrol boys take us across the street and tell us to be careful. … We always do what the patrol boy says.”Footnote 61 Mancuso's description reflects the importance of physical co-presence to the objectives of the safety patrol. The patrol member initiated pedestrian movement, judged traffic, and spoke directions to the pedestrian, while the pedestrian listened to the patrol member and regulated their movement accordingly.

Mancuso's gendering of the safety patrol members as male points to the patrol's gendered division of labor, and additional accounts from this time frequently stated that boys patrolled outside of school grounds on street corners and girls patrolled inside the school or on the playground.Footnote 62 As Dorothy Stewart and Fannie Iannizzaro, students from Warren, Ohio, reported, their school had “two [traffic] girls for each section of the hall. … They ke[pt] the passing lines of children straight and quiet.”Footnote 63 The girls’ duties served a similar function to the boys’ duties—that of teaching and regulation—but the girls performed them within the spatial confines of the school.

The stakes of safety education were particularly high when it came to educating boys, as boys—predominantly working-class boys—were statistically more likely to have accidents.Footnote 64 This was due to a combination of factors, including the pervasiveness of physicality in boy culture and character-building initiatives.Footnote 65 To protect boys, curricular and extracurricular educators enfolded care ethics into adventure. As an article in Boys' Life, the monthly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America, discussed in 1932, “[y]our own safety and the safety of everyone associated with you depend upon individual care and thoughtfulness. … In many accidents, it is not the individual whose thoughtlessness created the dangerous situation who suffers, but some person wholly innocent of its cause.”Footnote 66 Articles such as this reframed nurturing behavior by describing the boy's duty to protect his family, friends, and proximate strangers through thoughtful actions.

Some songs furthered both the coding of the safety patrol as a boy's activity and the positioning of the AAA as a core sponsor of safety patrols. The lyrics of songs related to the safety patrol usually disseminated the gospel of the safety patrol; they described the character traits and enumerated the duties of patrol members, reinforcing their status as admirable members of society.Footnote 67 Take Lucille Oldham's “The Official Song of the Safety Patrol,” a song published by a local branch of the AAA.Footnote 68 In Oldham's song, the singer embodies the role of one of “the boys of the safety patrol.”Footnote 69 Throughout the song, they describe their dedication to perform their duties “warm weather or cold” to ensure that their “schoolmates are all safe and sound.”Footnote 70

As dutiful workers, patrol members also contributed to the efforts of traffic officers and compensated for racial disparities in safety resources. As one reporter from the Afro-American noted, students at two schools for black children in Baltimore, P.S. 101 and 133, were “endangered throughout the school year by uncontrolled traffic on four busy intersections surrounding the buildings[,]” and the assigned traffic officer “could not be found.”Footnote 71 This was in contrast to the two traffic officers who helped children from P.S. 60, an elementary school for white children, safely cross the street.Footnote 72 Despite this discrepancy, there had been no traffic accidents and no formal complaints at the schools. The principal of P.S. 133 credited several precautions, including “a very efficient safety patrol…which ha[d] been successful in ensuring the safety of the pupils.”Footnote 73

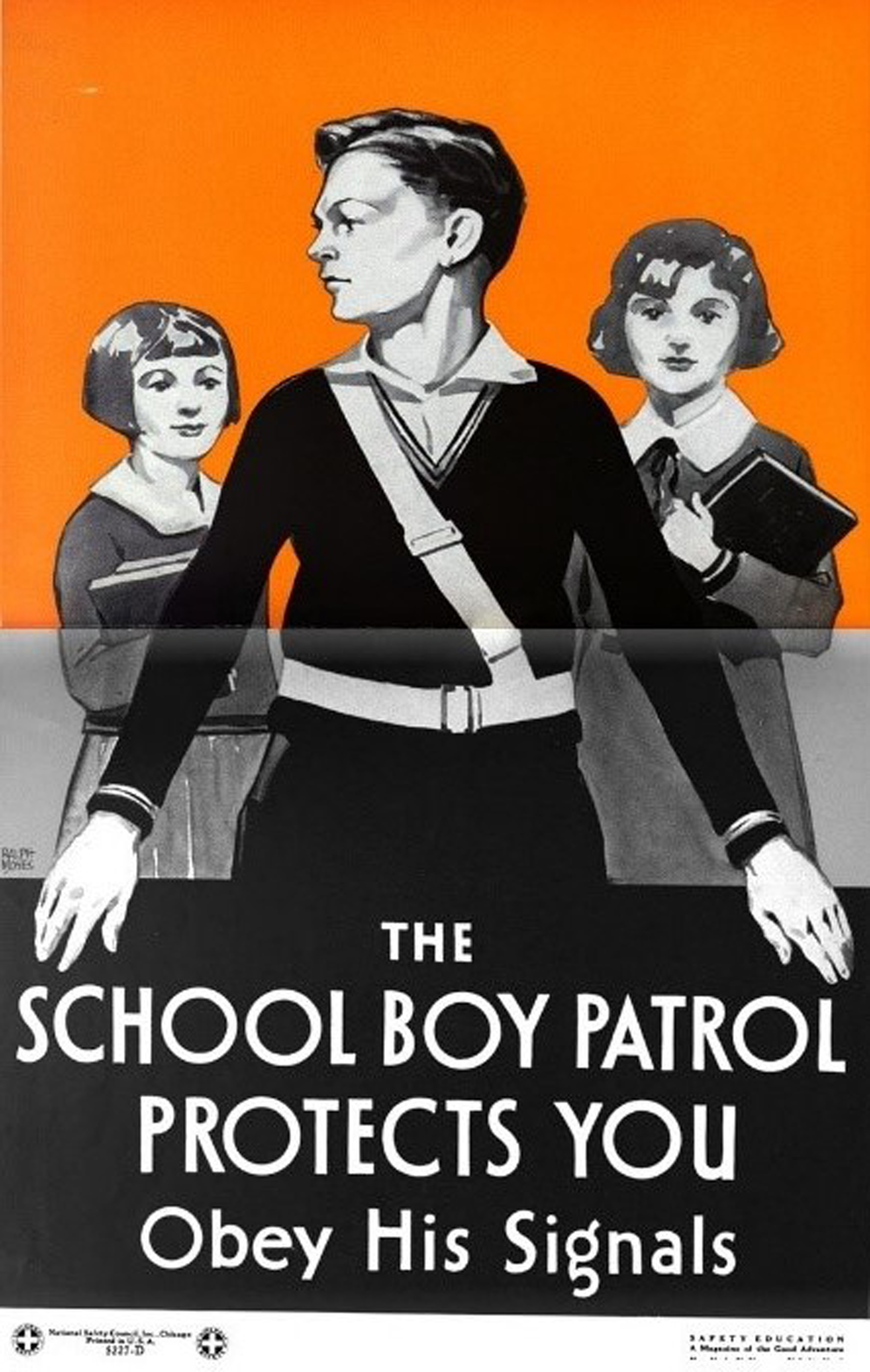

Since patrols existed throughout the country, local branches varied in makeup based on their demographics and the needs of individual schools.Footnote 74 However, there was a flattening of the kinds of boys visually depicted as archetypal patrol members. Sheet music covers, films, books, and posters typically depicted American safety patrollers as white boys assisting with traffic.Footnote 75 As the following poster from the NSC illustrates (Figure 3), images of the safety patrol member conform to white and masculine phenotypes.

Figure 3. Safety patrol poster issued by the NSC. “The School Boy Patrol Protects You: Obey His Signals,” Safety Education: A Magazine of Good Adventure, September 1934, n.p. Permissions to reprint/use granted by the NSC © 2021.

The safety patroller is distinguished from the female students. Positioned at the foreground of the image, he assumes the role of the orderly patrol boy with his focused expression scrutinizing traffic and both of his arms preventing the students behind him from crossing the street. His black sweater contrasts with his white Sam Browne belt, the standard uniform and visual signifier of the patrol, which was the same style often worn by police officers and military members.Footnote 76 The image and text depict the boy as an authority to be respected by his fellow students. This patroller was a chief collaborator with traffic officers in the present who was prepared to continue accident prevention efforts in the future. Both he and his classmates were entrenched in this community effort, one predicated on the physical enactment of safety lessons. The service of the safety patrol—as depicted in songs and images and enacted on street corners—allowed children to practice thinking about the safety of others while contributing to accident prevention.

The Ether's Safety Patrols

Since visually judging traffic was one essential component of educating children through safety patrol work, the segment adapted the safety patrol to fit the unique conditions of the radio and exploited an association with the safety patrol movement. During the segment, Caesar and Vallée define the safety patrol more generally than the National Safety Council Handbook, handbooks of local branches, and the observations of children. Caesar states a circular definition of the safety patrol, calling it “an organization of schoolboys who pledge themselves to work for safety.”Footnote 77 Though this definition is not mutually exclusive with that of the official organization, it deemphasizes the primary mission of the safety patrol, reflecting Caesar's more general approach to safety work.

Despite this contrast in definitions, the introduction to the segment establishes a connection with the safety patrol movement on a national level. Vallée states, “Irving and all of us are gratified by the interest taken in his songs of safety by schools all over the country. Tonight's new song is an example.”Footnote 78 This statement situates Caesar and Marks's song in the middle of an ongoing safety discourse. It frames the songs as sonic signifiers of national community and stresses their purported educational value through the context of the schools. Though “The Safety Patrol March” was not directly tied to the AAA or the NSC, the segment's introduction positions the song among these musical efforts by acknowledging the work of individual safety patrols while also creating a broader community of patrol members.Footnote 79 In doing so, the introduction straddles the boundaries between the national and the local. It constructs a national community by uniting local safety patrols, and then it hails a new set of participants into the safety patrol by adding radio listeners to this national community.

As the segment progresses, it develops its connections to the safety patrol movement by imitating practices common to safety radio programs. During this time, patrol members and their leaders broadcasted lessons, activities, plays, and songs on local radio stations to educate a broader audience.Footnote 80 Additional safety radio programs adapted the popular radio strategy of creating children's clubs for their listeners.Footnote 81 They typically featured an avuncular male host as the program's safety club leader, creating a community of children through imaginative play.Footnote 82 Some of these clubs, such as Uncle Red's A.B.C. Club, had thousands of members, including children from different states and countries.Footnote 83 Corporate sponsors eventually developed programs with a similar concept and format, as exemplified by Standard Oil Company's Babe Ruth Boys Club, which claimed that “the Home Run King ma[de] a special plea for safety” on every broadcast.Footnote 84

The Royal Gelatin segment positions Caesar as a safety club leader and depicts the guest students from New York City's P.S. 10 as members of a safety patrol broadcasting a safety lesson. The segment lionizes Caesar as an authoritative and affable instructor. The students respond to his requests for quiet with silence and dutifully answer his questions during the segment's skit.Footnote 85 The general format of the segment further establishes the student group as a safety patrol. Caesar leads the students through a brief lesson followed by a performance of “The Safety Patrol March,” reflective of the broadcasting practices of local safety patrols on local radio stations. Though The Royal Gelatin Hour was a nationally circulated broadcast, the segment's similarity to local radio programs reinforced its cultivation of an intimate community.

The segment reflects the ideology of the safety patrol by coding it as a boy's activity and portraying the boys as exemplary safety patrollers. The program primed its listeners for its boy-centric focus the week before the episode; Caesar claimed that “most of [his] songs are for boys and girls but ‘The Safety Patrol’ is a marching song for boys,” demarcating the segment as a space for boys.Footnote 86 Furthermore, during the safety-patrol-themed segment, both Caesar and Vallée alternate between calling the children “boys” and “men,” leveraging the oscillation for comedic effect. For example, Caesar states, “I thought you would like to meet some of our safety patrolmen so, I invited sixteen boys.”Footnote 87 Later, Vallée states, “thank you men” accompanied by audience laughter, and Caesar echoes “thank you men….Now class…as I told you boys up at school.”Footnote 88 In conjunction with the use of an all-boys chorus, this humorous device accentuates the male dominance of this activity and the future potential of boys as contributors to accident prevention. It illustrates the indoctrination of the boys in the process of training and habituation as they age.

Beyond the gender of the students and their potential function—as a “safety patrol” and a “glee club”—the nationally broadcast segment provides listeners with little information about P.S. 10.Footnote 89 The on-air introduction to the school notes that the boys were from “New York Public School 10 uptown.”Footnote 90 The lack of additional information given to the audience and the radio's absence of visual information has the potential to allow the audience to construct their own image of the ether's safety patrol.

The content of the segment's skit highlights the ambiguous identity of the students. The main objective of Caesar's lesson before they sing the “Safety Patrol March” is to emphasize that diction is “the most important thing a singer should learn,” not to disseminate safety doctrine.Footnote 91 This lesson policed and shaped the boys’ mode of speech and self-presentation; it did not test their retention of safety lessons. While one cannot assess how the audience responded to these discontinuities, these fractures create a tension between the possible identities and extracurricular affiliations of the group of boys and between their performance with Caesar on the air and their actual lives as P.S. 10 students. For example, portraying the group as both a safety patrol and a glee club showcases two contributions to their community: helping children cross the street and educating through song. The conflation of the glee club with the safety patrol further contorts the mission of the safety patrol, rooting it in song and therefore positioning song as a way to access the experiential dimension of safety education.

Safety and Danger in Public School Number 10

While the segment promotes an image of unity, there was a contrast between the actual circumstances that children in schools such as P.S. 10 faced and the protective powers of song presented in the segment. When taken in conjunction with the contemporaneous geography of public schools in Manhattan, the short description of “New York Public School 10 uptown” points to an overcrowded elementary school with a predominately black population during the 1930s, located at St. Nicholas Avenue and West 117th Street in Harlem.Footnote 92 Although this school had a safety patrol, students faced danger and were at risk of accidents. According to former P.S. 10 student Cyril H. Price, the school had a successful safety patrol in the 1930s that eliminated traffic injuries for an entire school year, and members were rewarded for their service with a field trip to Yankee Stadium.Footnote 93 Despite these efforts, however, traffic accident statistics for the school district placed it at the fifth-highest rate of childhood street accidents per acre out of forty-four school districts surveyed in New York City.Footnote 94 Contemporaneous education scholar Hubert E. Brown identified several factors that increased the risk of childhood accidents, including population density due to tenement housing and a lack of recreational facilities or public play spaces.Footnote 95

Potential traffic accidents, racial discrimination, and outdated school facilities contributed to the hazards faced by P.S. 10 students and other students in Harlem schools. The commission tasked with determining the reasons for and providing governmental solutions to the Harlem riot of 1935 acknowledged concerns regarding Harlem Public Schools “on the grounds that they [were] old, poorly equipped and overcrowded and constitute fire hazards … [and] in the administration of these schools, the welfare of the children [was] neglected and racial discrimination [was] practiced.”Footnote 96 As Edith M. Stern reported in The Crisis in 1937, “Harlem schools [were] among the worst in the city,” and few new schools in the area had been built since 1900.Footnote 97 Child endangerment was also a concern of the Permanent Committee for Better Schools in Harlem, which advocated for the creation of new schools, in part due to concerns regarding overcrowding and the daily commute of students from P.S. 10 and P.S. 170, which required students to cross around twelve “dangerous traffic streets.”Footnote 98 Despite these efforts, school administrators denied the existence of discrimination. Instead, they blamed the students’ underperformance mainly on their home lives.Footnote 99

By distancing the listener from the actual context of P.S. 10 uptown, the segment addressed childhood accidents as primarily a pedagogical problem by assigning blame to children instead of drivers or civil engineers. The segment presents a sanitized version of the safety education movement, emphasizing community initiatives and amicable relationships between adults and children. By presenting a homogenized experience of safety, it does little to acknowledge the factors that put some children—particularly the students of P.S. 10 in Harlem—at a greater risk for accidents in unsafe learning environments. Instead, it emphasized the importance of the roles of boys as stewards of safety through proper singing technique and positioned after-school radio programs as utopian communities for children to learn safety lessons.

“The Safety Patrol March”

When developing this idealized community of future adult citizens, “The Safety Patrol March” presents the possibility of priming singers, listeners, and readers to think through different community roles. The song describes a code of conduct—a membership pledge in march time—that introduces attentive listeners to the ideal child roles created by adults in society while presenting children with the opportunity to perform these roles.

The song's ternary form is divided between children who receive assistance from the safety patrol (A) and safety patrol members (B). This deviates from several songs about the safety patrol, since here the singer adopts the roles of both the pedestrian and the patrol member. The song's form accentuates the pedestrian's role. This positions the patrol members in relation to their constituents, placing the pedestrian's laudatory remarks as both an initial enthusiasm for the patrol and then, in the rearticulation after the B section, as a positive reaction to the patrol.

In the refrain, the singers assume the roles of the cooperative children obeying the tenets of traffic safety, singing the following in the second stanza:

Shout, “Hooray! Hooray! Hooray!” for the Safety Patrol!

This is why our parents aren't nervous,

We make “Safety” our goal,

And they're glad to know we're at the service of the Safety Patrol.Footnote 100

This section encodes their obedience while valorizing the safety patrol as a surrogate watchful eye alleviating parental anxieties.

The subsequent section distinguishes the role of the safety patrol members from the pedestrians. The singers sing the following in the third stanza:

Stop! Look! Listen!

Those are three commands;

You must stop and look and listen,

You must watch the Patrol Boy's hands[.]Footnote 101

In the first iteration of “Stop! Look! Listen!” the singers follow these instructions with rests, as if to embed proper conduct in the music by allowing time for the singers and audience to stop, look, and listen, keeping abreast of the patrol's directions (Figure 4).Footnote 102 In conjunction with the repetition of the directions, these orders reflect the multisensory dimension of safety education. The singer proclaims a list of traffic safety directives in the next stanza in a declamatory fashion, reflecting the march's regimented character through a repetitive pattern. They accent the two dotted-quarter pulses in each measure for most of the stanza (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The first iteration of the lyrics “Stop! Look! Listen!,” mm. 41–44. Transcribed from Irving Caesar and Gerald Marks, “The Safety Patrol March” (New York: Irving Caesar, 1938), Diana R. Tillson Collection of Children's Sheet Music, Cotsen Children's Library, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. The Safety Patrol March Words and Music by Irving Caesar and Gerald Marks Copyright (c) 1937 Round Hill Songs, WC Music Corp. and Irving Caesar Music Corp. Copyright Renewed All Rights for Irving Caesar Music Corp. Administered by WC Music Corp. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

Figure 5. The regimented character of the safety patrol's second stanza, mm. 57–60. Transcribed from Caesar and Marks, “The Safety Patrol March.” The Safety Patrol March Words and Music by Irving Caesar and Gerald Marks Copyright (c) 1937 Round Hill Songs, WC Music Corp. and Irving Caesar Music Corp. Copyright Renewed All Rights for Irving Caesar Music Corp. Administered by WC Music Corp. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

The text markings in the advertised sheet music amplify the resolute characterization of the safety patrol. The A section is marked as a refrain, but the B section is labeled as the space of the patrol and given the character of deciso (Figure 6). When performing the song, singers and listeners practice the roles of the dutiful child and the purposeful patrol member. Although the nature of children's actual engagement is unknown, the song and the radio could be interpreted as creating additional accountability measures. When taken in conjunction with the potential of radio to foster communities, knowledge of other children learning their roles could hold some children accountable to the roles prescribed by adults.

Figure 6. The labels and performance directions for the song's two sections. Caesar and Marks, “The Safety Patrol March.” The Safety Patrol March Words and Music by Irving Caesar and Gerald Marks Copyright (c) 1937 Round Hill Songs, WC Music Corp. and Irving Caesar Music Corp. Copyright Renewed All Rights for Irving Caesar Music Corp. Administered by WC Music Corp. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

The show's premiums expand the songs’ creation of social groups and reflection of civic duty. The two premiums advertised during this episode of The Royal Gelatin Hour—sheet music to “The Safety Patrol March” and a safety patrol emblem—had the potential to substantiate community ties after the broadcast.Footnote 103 As advertised when the segment concluded, the products were desirable status symbols. After imploring parents to send for sheet music, the on-air advertisement promised to send “another reminder of safety to safeguard children who must cross streets going to school … They'll wear this handsome pin proudly.”Footnote 104 The language scripts the child's engagement with the premiums as objects of belonging to this manufactured radio club. The emblem became a visual marker of belonging and a future role in one's community, reflecting contemporaneous toy trends that emphasized the use of boys’ toys to train them to be future contributors to the public sphere.Footnote 105 It also extends the contextual associations of the music to the badge itself, framing it as an object of child-rearing and a reinforcer of safe habits through wear, imaginative play, and performance.

The historical resonances of the emblem heighten the segment's connection to safety patrols and children's radio programs. Though badges were not specified as official components of safety uniforms by the national handbook, some local branches included badges as part of their standard uniform.Footnote 106 Patrol members also earned emblems, medals, and trophies for acts of service, their roles as safety captains, or winning safety contests.Footnote 107 While the actual use of the emblem by consumers is unknown, its historical signification of merit illustrates the multiplicity of the badge's meaning, as an artifact of one's membership to Caesar's safety patrol, as an award for assumed attentive listening to the segment, and as a token of one's loyalty to Royal Desserts products.

The Place of Sing a Song of Safety

Critically examining radio ephemera and children's music highlights music's role in citizenship formation and interventions in public safety efforts. This reflects the synergy of and tension between goodwill efforts and profit, between Caesar as a good Samaritan of Tin Pan Alley and Caesar as an opportunist, and between the entertainer as a celebrity and as a public health official. It shows the potential of educational songs and premiums to improve the safety of children, yet the inability of these mediums, in the case of P.S. 10, to address external barriers to safety in children's lives. This reveals both how children were educated about safety and who was positioned as protecting and worthy of protection. Inscribed in these artifacts are not only lessons about accident prevention, but also historical snapshots of prescriptive gender roles and the presentation of safety as a racialized discourse.

Through the social groups described and marketed to on the program, the child's listening experience was constellated in a complex of radio celebrities, companies, educators, parents, and other children. As mothers reviewed the safety songs with their children and parents sent in for copies of the songs, the show's advertisements positioned parents themselves as consumers and stewards of children's music. They monitored the child's listening hygiene and curated musical content through their tuning of the radio dial, consumption, and teaching, as prescribed by the segment. While one cannot advance a unilateral reading of child and parental radio engagement, the program's advertisements suggest that thinking through the marketing strategies and relations in children's music provides us with multiple insights that both encompass and exceed the traces of children's musical experiences. This includes the connection of music to advertising, the musical experiences of adults, and the construction and circulation of ideal child and parent roles.

The sonic traces in practicing and overhearing safety songs and visual encounters with emblems and sheet music positioned audience members in relation to themselves, collectives, and the constructed ideals portrayed on the show. The segment and its premiums place one amidst the simultaneous protection and endangerment of the students of P.S. 10, the kinship ties of families, and local safety patrol branches. Music and radio shuttle the listener between the local and the national, leading one to the child's role in and contributions to American society and the imagined “Johnny B. Careful” and “Mary B. Ware.”