I. Introduction

With increasing globalization and interactions between cultures, countries’ behaviours are converging in many ways, including consumption patterns. This mimicry raises concerns when consumers in developing countries copy trends from high-income countries that are considered undesirable from such viewpoints as human health consequences. Tobacco and sugar are perhaps the most frequently mentioned items, as tobacco consumption globally has doubled since the early 1960s, and sugar use has increased by nearly half and is contributing to the spread of obesity. But the other item closely monitored by health authorities is the level of consumption of alcoholic and sweetened nonalcoholic drinks. Producers of beverages also seek to monitor consumer trends, focusing not only on overall levels of consumption but also on its composition or mix to ascertain changes in consumer preferences or behaviours. The wine, beer, and spirits industries, for example, are well aware that wine's share of global recorded alcohol consumption volume more than halved between 1961 and 2015, falling from 35% to 15%, while beer's increased from 29% to 42%, and the share of spirits rose from 36% to 43%.

The extent to which alcoholic beverage consumption patterns are converging across countries has been the subject of many previous studies. Examples since the new millennium include Smith and Solgaard (Reference Smith and Solgaard2000), Bentzen, Eriksson, and Smith (Reference Bentzen, Eriksson and Smith2001), Aizenman and Brooks (Reference Aizenman and Brooks2008), and Colen and Swinnen (Reference Colen and Swinnen2016). However, those studies have limited the scope of their analysis to a specific region or group of high-income countries or to just one or two types of alcohol. The present study updates earlier findings, covers all countries of the world since 1961 and key high-income countries since 1888, and introduces new summary indicators to capture several dimensions of the extent of convergence in total alcohol consumption and its mix of beverages. It also distinguishes countries according to whether their alcoholic focus was on wine, beer, or spirits in the early 1960s as well as their geographic regions and their real per-capita incomes. For recent years, we also add expenditure data and compare alcohol with soft drink retail spending, and we show the difference it makes when unrecorded alcohol volumes are included as part of total alcohol consumption.

In exploring alcohol consumption trends in European countries from 1960 to 2000, Smith and Solgaard (Reference Smith and Solgaard2000) find that the market shares for traditional beverages declined. In the Nordic countries, for example, the dominance of spirits in 1960 diminished as beer and wine shares grew over those four decades. Bentzen, Eriksson, and Smith (Reference Bentzen, Eriksson and Smith2001) use time series techniques to study alcohol consumption convergence in a number of European countries. They conclude from their unit root tests that differences in total alcohol consumption levels are diminishing. Aizenman and Brooks (Reference Aizenman and Brooks2008) study convergence during 1963 to 2000 across a larger sample of countries that included members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and middle-income countries, but only for beer and wine. Colen and Swinnen (Reference Colen and Swinnen2016) analyse mainly beer but also wine consumption across a large sample of high-income and developing countries. Echoing the conclusions of Smith and Solgaard (Reference Smith and Solgaard2000), they find that in many traditional beer- (wine-)drinking countries, the share of beer (wine) in total alcohol consumption is declining, and that of wine (beer) is increasing. They also show that beer consumption increased in developing countries with rising incomes but fell once higher levels of income were reached. However, spirits are omitted from their analysis.

The present paper first describes the data sources to be used. It then suggests several ways to indicate convergence over time in total recorded alcohol consumption and in the mix of beverages. The main section then presents findings based on annual data assembled for countries and regional residual country groups spanning the world from 1961 to 2014 and for some high-income countries dating to the late nineteenth century. The results from 1961 are shown also for groups of countries whose earlier focus was wine, beer, or spirits as well as for various regions of the world and by real per-capita income. Also shown is the relative importance of alcoholic versus various nonalcoholic drinks in total beverage consumption volumes and expenditures since 2001. Estimates of unrecorded alcohol consumption for the years 2000, 2005, and 2010 are then used to test the robustness of the convergence findings when these estimates are included as part of total alcohol consumption. The final section summarizes the findings and suggests that further research could provide new demand elasticity estimates, using econometrics to explain the varying extents of convergence over time, space, and beverage type.

II. Data Sources

The wine, beer, and spirits consumption volume data in this study are sourced from two new annual databases: one that includes wine, beer, and spirits volumes and stretches from 2014 back to the 1880s for eleven high-income countries and back to 1961 for all other countries (Anderson and Pinilla, Reference Anderson and Pinilla2017); and another that includes wine, beer, and spirits average consumer expenditure data compiled for all countries back to 2001 and for some high-income countries back to the 1950s (Holmes and Anderson, Reference Holmes and Anderson2017).

The longer time series on volumes consumed (in litres of alcohol, or LAL)Footnote 1 from 1961 includes 48 important wine-producing and/or wine-consuming countries plus 5 residual regions (treated here as 5 extra “countries”) that together make up the world. That database has a full matrix of data for the period 1961 to 2014, apart from information on Croatia, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, data for which became available only after the breakup of the Soviet Union. The shorter time series (2001–2015) is available from Euromonitor International (2016) for 80 countries plus, again, 5 residual regions.

To estimate average prices for wine, beer, and spirits for each of the countries that have expenditure data, we simply divide expenditure by the consumption volume. The value data are expressed in current US dollars converted from local currencies using each country's annual average nominal exchange rate.

Euromonitor International (2016) also provides soft drink volume and expenditure data from 2001 and total expenditure on all products. Other key statistics used include figures compiled from the World Health Organization (2015) and, in the case of our proxy for real per-capita disposable income back to 1961, the Maddison gross domestic product (GDP) estimates in 1990 International Geary-Khamis dollars.Footnote 2

All the consumption data mentioned above refer only to what has been recorded by national governments; an additional amount of alcohol produced and consumed each year is not recorded. WHO (2015) reports estimates of that unrecorded alcohol consumption volume for 98 countries for 2000, 2005, and 2010. In Section V, these are used to test the robustness of our findings on convergence in recorded alcohol consumption levels and mixes.

III. Indicators of Convergence

To study convergence across countries in national alcohol consumption volumes and beverage mixes, we employ a number of different indicators. One is simply the coefficient of variation (CoV) across countries each year. Then two indexes developed by Anderson (Reference Anderson2014a) to study wine grape varietal patterns across countries and regions are adapted to beverage consumption to measure convergence over time in national beverage consumption mixes toward the (changing) world average mix.

A. Coefficient of Variation

CoV can be calculated across countries each year for total alcohol consumption volume and for the share of each of the three main beverage types in the total volume of recorded alcohol consumption. CoV measures the concentration of data around the mean value: If it declines over time, this serves as a simple indicator of cross-country convergence. It is calculated for each year by taking the level of consumption per capita across countries and dividing the standard deviation of the series, σ

t

, by the mean value of the sample,

![]() $ {\bar X}_t $

:

$ {\bar X}_t $

:

B. Beverage Consumption Intensity Index

The beverage consumption intensity index indicates the importance in a particular year of one type of alcoholic beverage in a country's alcohol consumption relative to the average share of that beverage in alcohol consumption by all countries of the world. We thus define the consumption intensity index for country i as

where there are i = 1, … , 53 (or 85) countries, and n = 1, 2, 3 beverages corresponding to wine, beer, and spirits. We define f

in

as the fraction of wine, beer, or spirits consumption in total national alcohol consumption volume or expenditure in country i, such that 0 ≤ f

in

≤ 1 and

![]() $\sum\nolimits_{n = 1}^3 {f_{in} = 1} $

. This is divided by the fraction for that same beverage in world total alcohol consumption, f

n

, with 0 ≤ f

n

≤ 1 and Σ

n

f

n

= 1. For brevity, we tabulate weighted averages of intensity indexes for groups of countries, using as weights each country's consumption of that beverage as a fraction of the group's total consumption of that beverage.

$\sum\nolimits_{n = 1}^3 {f_{in} = 1} $

. This is divided by the fraction for that same beverage in world total alcohol consumption, f

n

, with 0 ≤ f

n

≤ 1 and Σ

n

f

n

= 1. For brevity, we tabulate weighted averages of intensity indexes for groups of countries, using as weights each country's consumption of that beverage as a fraction of the group's total consumption of that beverage.

C. Alcohol Consumption Mix Similarity Index

The similarity index is a variant of an index developed by Anderson (Reference Anderson2014a) that in turn is adapted from indexes introduced by Griliches (Reference Griliches1979) and Jaffe (Reference Jaffe1986). Anderson (Reference Anderson2014a) uses it to measure the extent to which the wine grape varietal mix in the vineyards of one region or country matches that of another region or country or the world. Here, we adapt it for the purposes of comparing the beverage consumption mix of any one country with that of any other country or the average for the world.

The index uses vector representation to project combinations of variables, with lengths determined by the shares of wine, beer, and spirits in a country's total alcohol consumption volume or expenditure. The vector f im is again the fraction of beer, wine, or spirits consumption in the national alcohol consumption volume or expenditure in country i, such that these fractions are between 0 and 1 and total 1. The index is defined as

$$\omega _{ij} = \displaystyle{{\sum\limits_{m = 1}^M {\,f_{im} f_{\,jm}}} \over {\left( {\sum\limits_{m = 1}^M {\,f_{im} ^2}} \right)^{1/2} \left( {\sum\limits_{m = 1}^M {\,f_{\,jm} ^2}} \right)^{1/2}}}, $$

$$\omega _{ij} = \displaystyle{{\sum\limits_{m = 1}^M {\,f_{im} f_{\,jm}}} \over {\left( {\sum\limits_{m = 1}^M {\,f_{im} ^2}} \right)^{1/2} \left( {\sum\limits_{m = 1}^M {\,f_{\,jm} ^2}} \right)^{1/2}}}, $$

where i = 1, … , 53 (or 85) countries, j = 1, … , 53 (or 85) countries, and m = 1, 2, 3 beverages corresponding again to wine, beer, and spirits; therefore, M = 3. This makes it possible to indicate the degree of beverage mix “similarity” of any pair of countries. The index also can be generated for each country relative to the average of a sample of countries or of all the world's N countries. In short, ω ij measures the degree of overlap between f i and f j . The numerator of Equation (3) is large when i’s and j’s beverage mixes are very similar. The denominator normalizes the measure to unity when f i and f j are identical. Hence, ω ij is close to 0 for pairs of countries with little similarity in their beverage mix and 1 for pairs of countries with identical beverage consumption mixes. For cases between those two extremes, 0 < ω ij < 1.

This index is conceptually similar to a correlation coefficient. Like a correlation coefficient, it is completely symmetrical in that ω ij = ω ji . Thus, the results can be summarized in a symmetrical matrix plus a vector that reports the index for each country relative to that for the world (as reported in Holmes and Anderson, Reference Holmes and Anderson2017).

In a hypothetical two-beverage case, where country i has 50% of its alcohol consumption consisting of beer and country j has 30%, the index of consumption similarity is the cosine of the angle between the two vectors in Figure 1. Therefore, differences can be judged by the angular separation of the vectors f i and f j for the two countries (Jaffe Reference Jaffe1986).

Figure 1 Angular Separation Between Two Countries (i and j), Each Consuming Just Two Beverages (Beer and Wine)

It is possible to generate the similarity index for groups of countries by again using as weights each country's consumption of that beverage as a fraction of the group's total consumption of that beverage.

IV. Findings

In this section, we examine two types of convergence across countries in their alcohol consumption patterns: (i) in the aggregate level of alcohol consumed per capita per year, and (ii) in the mix of wine, beer, and spirits. The volumes of consumption, measured in litres of alcohol, are compared where possible with values of consumption, because the latter also incorporate changes in prices paid by consumers (e.g., because of a desire for higher-quality beverages or a change in relative excise taxes).

Before examining our convergence indicators, it is worth reflecting on why consumption patterns might differ. If all products could be traded around the world without cost, and if there were no government interventions, such as consumption (excise) or trade taxes or differences in value-added tax rates across jurisdictions, then the retail prices of each type of beverage would be identical throughout the world. According to Stigler and Becker (Reference Stigler and Becker1977), the key reason then for major differences in alcohol consumption patterns is differences in per-capita incomes. If all beverages were normal goods, we might then expect convergence in the level and mix of alcoholic (or indeed all) beverages consumed as convergence across countries occurs in national average per-capita incomes (which has been happening in recent decades – see, for example, Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2016).

In reality, costs of trading beverages across national borders are not zero (even though they have declined greatly over the past 150 years), which means countries have tended in the past to concentrate their consumption on those alcoholic beverages that can be produced at the lowest cost locally – hence the dominance of spirits in cold countries, beer where malting barley can be easily grown, and wine in the 30o to 50o latitude range near maritime weather influences. Excise and import taxes on beverages are also dissimilar across countries, and they vary greatly across beverage types (Anderson, Reference Anderson2010, Reference Anderson2014b), in some cases to protect local producers and thereby reinforcing climate-induced differences. Value-added taxes also vary across countries. Moreover, temperance movements have had different effects on the social acceptability of alcohol consumption at different times in various places (see, for example, Briggs, Reference Briggs1985; Phillips, Reference Phillips2014; Pinney, Reference Pinney1989, Reference Pinney2005; Wilson Reference Wilson1940). So, too, have concerns about human health: as per-capita incomes rise, people can afford to spend more on alcohol consumption but also choose to limit its volume for health reasons (in some cases, switching to soft drinks, including bottled water); and some people are also substituting greater quantities of wine (especially still red) because of its perceived positive influence on health when drunk in moderation. Given all the above possible influences on beverage consumption patterns, it would not be surprising if convergence in those patterns were not evident in the data.

A. Alcohol Consumption and Income

One way to begin to look for convergence in alcohol consumption patterns is to plot consumption per capita against real income per capita. That is done in Figure 2 for 53 countries and residual regions spanning the world from 1961 to 2014, showing the volume of total alcohol consumption as well as of wine, beer, and spirits, respectively. As demonstrated by each beverage, the volume of consumption first tends to rise with per-capita incomes but then falls. The peak consumption occurs at a real per-capita income (in 1990 International Geary-Khamis dollars) of $16,900 in the case of all alcohol. That is just slightly above the average per-capita income of Western Europe in 1990. The peak consumption occurs at $15,100 for wine, $18,100 for beer, and $16,350 for spirits. These inverted U-shaped figures suggest that income convergence alone (the gradual catching up of developing countries to the per-capita incomes of high-income countries) does not necessarily lead to convergence in alcohol consumption patterns based on per-capita volumes.

Figure 2 Relationship Between Recorded Alcohol Consumption Volume and Real GDP per Capita, 53 Countries/Regions,a 1961–2014 (One Dot per Country-Year)

B. Long-term Trends in Alcohol Consumption per Capita, Total, and by Type

Trends in the volume of total alcohol consumption per capita and in shares of overall alcohol consumption volume due to wine, beer, and spirits are shown in Tables 1 and 2 for a sample of high-income countries for which we have data from the late 19th century and in Table 3 for the world's 53 countries/regions since 1961. For the larger set of countries, consumption-weighted averages are shown for seven regions and for the world as a whole in the final rows of Table 3.

Table 1 Total Alcohol Consumption Volume per Capita, a High-Income Countries, 1888–2014 (Litres of Alcohol per Year)

a On average, the alcohol content by volume is assumed to be 4.5% for beer, 12% for wine, and 40% for spirits. Ready-to-drink spirits mixers are converted to spirits, assuming their alcohol content is 5%.

b 1898–1902.

c 1920–1923.

Source: Compiled from data in Anderson and Pinilla (Reference Anderson and Pinilla2017).

Table 2 Shares of Wine, Beer, and Spirits in Total Alcohol Consumption Volume, High-Income Countries, 1888–2014 (%, 5-Year Averages)

a 1898–1902 b 1920–1923

Source: Compiled from data in Anderson and Pinilla (Reference Anderson and Pinilla2017).

Table 3 Alcohol per-Capita Consumption Volume and Shares of Beer, Wine, and Spirits, a 53 Countries, 5 Regions, and the World, 1961–1964 and 2010–2014 (LAL and %)

a These data are volume-based in litres of alcohol (LAL) per year, 4- or 5-year averages.

b The bold numbers indicate which beverage has the highest share in total alcohol consumption volume in the period shown.

c “O” refers to “Other” for the residual sub-group of countries for each of the five geographic regions that is not separately identified (each sub-group is treated like an extra country).

Sources: Compiled from data in Anderson and Pinilla (Reference Anderson and Pinilla2017).

For the majority of the 11 countries in Table 1 with data back to the 19th century, the alcohol consumption was greater in the 1960s than around 1890. For all but France and Italy, consumption rose even more by the 1980s, but then in all 11 countries, the total alcohol consumption per capita fell over the subsequent three decades to well below the unweighted average in the 1970s and 1980s. Even in the global database, which includes numerous developing and transition economies, the weighted average was almost the same in 2010–2014 as it was in 1961–1964 (last row of Table 3), despite having been higher than both of those period averages in each of the intervening decades. This is consistent with the inverted U-shaped trend of Figure 2(a).

Table 2 shows that the mix of alcohols was very different across the 11 high-income countries up to the 1960s, especially with respect to wine, which ranged from 2% to 87% of all national alcohol sales during 1961–1964, but also for beer (3%–81%) and spirits (10%–78%). By 2010–2014, the ranges had narrowed somewhat for beer (19%–53%) but less so for wine (5%–59%) and hardly at all for spirits (11%–74%).

The mix across the global database changed very substantially over the past 55 years: Wine's share more than halved from 34% to 15%; beer's rose by more than one-third, increasing from 29% to 42%; and spirits’ rose only slightly, from 37% to 43% (final row of Table 3). For 11 countries, wine remained the main type of alcohol consumed; for 12 countries, beer continued to dominate; and for 10 countries, spirits retained the largest share (see the bold numbers in Table 3).

However, it is not possible to conclude from simply observing these per-capita volume trends whether alcohol consumption patterns are converging across countries – hence the need for better indicators, to which we now turn.

C. Coefficient of Variation

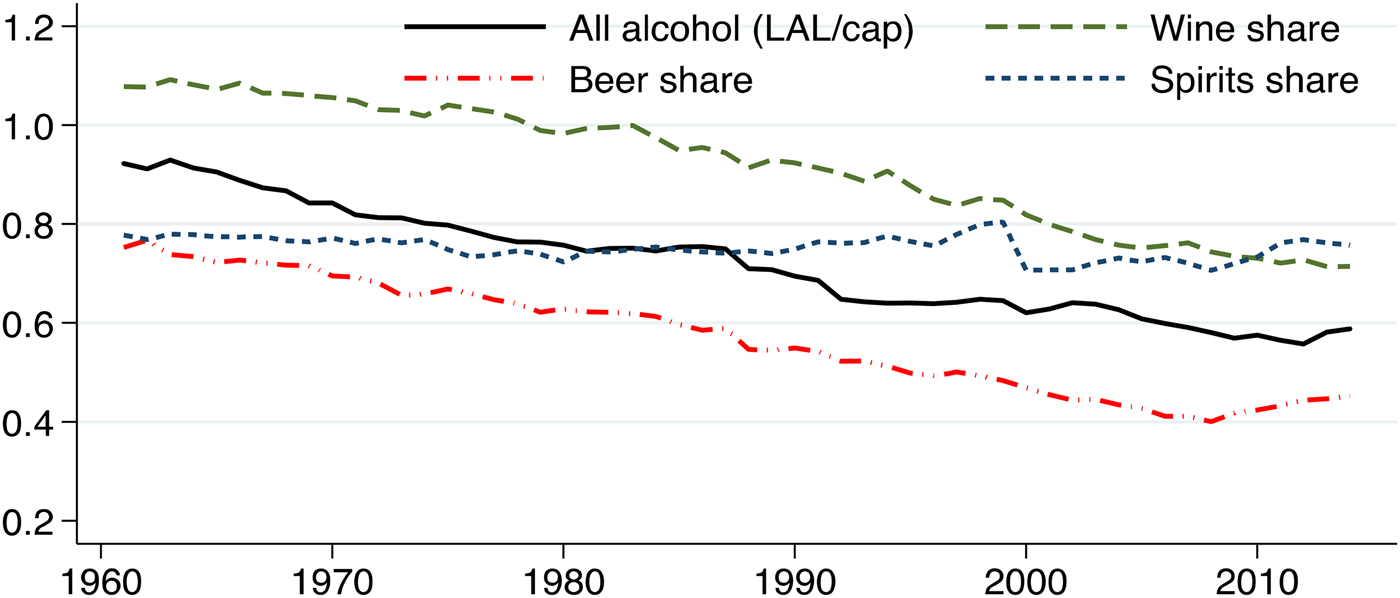

Since 1961, CoV has fallen for all three beverage groups, which implies some convergence. This trend can be seen in Figure 3, where CoV across the full set of countries is shown for the per-capita total volume of alcohol consumption and for the shares of wine, beer, and spirits within that total for each country. The coefficient for the total volume of alcohol consumption has nearly halved over the last half century, declining steadily throughout the period. There has been very little decline in the coefficient for the share of spirits, but there has been a very steep decline for beer (falling from 0.8 to 0.4), while that for wine has fallen by more than one-quarter.

Figure 3 CoV in Total Alcohol Consumption per Capita and in Shares of Each Beverage in That Total Consumption, across 53 Countries/Regions, 1961–2014

D. Beverage Consumption Intensity Index

To examine trends in the beverage consumption intensity (and mix similarity) indexes, it is helpful to divide into groups our 48 countries plus one residual sub-group of countries for each of five geographic regions (also called “countries” hereafter, for simplicity), yielding a total of 53. Two groupings are used here. One is according to which of the three beverages has the highest share of the volume of alcohol consumption in 1961–1964. It turns out those three groups each have almost the same number of countries (19 wine-focused and 17 each for beer-focused and spirits-focused; see footnote b of Figure 4). The other grouping is according to geography, with six regions identified. Each region includes a varying number of countries, ranging from 17 in Western Europe to 11 in Asia, 9 in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 6 in Latin America, 6 in Africa and the Middle East, and 2 in North America. One “country” in all but the last of those regions is the weighted average of all countries in the region that have not been separately identified. Australasia is omitted for space reasons.

Figure 4 Wine, Beer, and Spirits Consumption Volume Intensity Indexesa for Three Sub-sets of 53 Countries/Regions, by Main Focus in 1961–1964,b 1961–2014

The decrease in the share of wine in the overall volume of global alcohol consumption has been faster than the decrease in wine's share of consumption in a number of wine-focused countries, so those countries’ groups’ wine consumption intensity index has risen over the past half century, from 2.2 to around 3.0. Those groups’ spirits intensity index has not risen much (at around 0.5), but their beer intensity index has nearly doubled, from less than 0.4 to 0.75 (Figure 4(a)).

For the beer-focused countries, their beer intensity index has nearly halved, from close to 2.0 down to 1.2, while their wine intensity index has trebled and is now slightly above that for beer, and their spirits intensity index has fallen from just below to a little further below 1.0 (Figure 4(b)).

For the spirits-focused countries, their spirits intensity index has nearly halved in falling to 1.25, their beer intensity index has risen from 0.5 to 0.9, and their wine intensity index trend has remained flat at a little below 0.5 (Figure 4(c)).

Turning to the regions (Figure 5), the clearest convergence on intensity indexes of unity for the three beverages is found in Eastern Europe, and the next clearest region is North America. In Western Europe, by contrast, the beer and spirits intensity indexes have changed little from around 1.0 and 0.5, respectively, while the wine intensity index has risen from 1.6 to 2.7. The indexes for Africa and the Middle East also have diverged, with beer's rising further above 1.0 and spirits’ falling further below 1.0, while wine's has remained just below 1.0. In Latin America, wine and spirits have converged to just below 1.0 (wine from above, spirits from below), while beer has risen from 1.0 to 1.5. And in Asia, beer's index has doubled to 0.8, the spirits index has fallen from 2.4 to 1.5, and the wine index has risen from just above zero to 0.2.

Figure 5 Wine, Beer, and Spirits Consumption Volume Intensity Indexes for Three Sub-sets of 53 Countries, by Region, 1961–2014

These volume indexes suggest there are still major differences across these regions in their consumers’ beverage focus based on volume. But what do value-based indexes suggest, given that, as shown in Figure 6, tax-inclusive retail prices of alcoholic beverages vary enormously across these regions? We do not have expenditure data for all countries for the full period since 1961, but we do have them for recent years. Table 4 shows the differences by region between the consumption volume and value intensity indexes for the period 2013–2015. For three of the regions (Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and North America), all three value intensity indexes are closer to unity than are their volume indexes; for two regions (Australasia and Africa and the Middle East), two of the three value indexes are closer to unity than are their volume indexes; and for the other two regions, one of the three value indexes is closer to unity than their volume indexes. This comparison suggests that part of the reason for the cross-country variation in volume intensity indexes has to do with the variation in national average retail beverage prices.

Figure 6 Weighted Average Tax-Inclusive Retail Prices of Alcoholic Beverages, by Region, 2013–2015

Table 4 Wine, Beer, and Spirits Consumption Volume and Value Intensity Indexes, a by Region, 2013–2015

a The intensity index is defined as the fraction of wine, beer, or spirits consumption in total national alcohol consumption volume in country i divided by the fraction for that same beverage in world total alcohol consumption.

Source: Compiled from data in Holmes and Anderson (Reference Holmes and Anderson2017).

E. Alcohol Consumption Mix Similarity Index

The alcohol consumption mix similarity indexes for various country groups are plotted in Figure 7. The beer- and spirits-focused countries converged rapidly toward the world average (that is, the indexes approached 1.0) from the early 1960s to the mid-1980s and then moved more slowly in the next two decades. By contrast, the consumption mix similarity index for the wine-focused countries has not converged over this period. This result again reflects the fact that many of the wine-focused countries have reduced the share of wine in their consumption mix less than in other areas of the world. This is the same conclusion that we reached above by inspecting the intensity index for wine-focused countries in Figure 4(a).

Figure 7 Consumption Mix Similarity Index, Volume-Based, by Sub-sets of 53 Countries/Regions, 1961–2014

The same convergence toward unity in consumption mix similarity indexes is evident when countries are differentiated by geographic region, as in Figure 7(b). The convergence has been fastest for Asia and Latin America, albeit from a low base, but it is also evident for the other five regions, including North America and Eastern Europe, even though their indexes were already above 0.9 in the 1960s.

Even over the relatively short period of the 21st century for which we have data for 80 countries plus the 5 residual regions, as shown in Figure 8(a), the distribution of similarity indexes is becoming more skewed over time toward unity.

Figure 8 Convergence of Volume- and Value-Based Similarity Mix Indexes for All 85 Countries/Regions, 2001–2015

The volume-based distributions are comparable with those for value-based similarity indexes for the same three 5-year periods. The latter distributions are even more skewed toward unity than the volume-based similarity indexes (compare Figures 8(a) and 8(b)). Together, these findings indicate a general if not rapid global convergence in national beverage mixes.

F. Alcohol Consumption and Aggregate Expenditure

The moderating impact on indicators of the differences across countries in retail prices of alcoholic beverages (both absolute and relative; see Figure 6) suggests the need to revisit the finding from Figure 2 of an inverted U-shaped relationship between national per-capita alcohol consumption volume and real GDP per capita. This is done for our larger sample of 85 countries for the years 2001–2015 in Figure 9 for volumes and values of total alcohol consumption per capita, which are plotted against aggregate expenditures per capita in 2015 US dollars. An inverted U-shape prevails for volume but not for value of alcohol consumption as national aggregate expenditure rises.

Figure 9 Relationship Between per-Capita Aggregate Expenditures and Recorded Alcohol Consumption Volume and Value, 80 Countries,a 2001–2015 (One Dot per Country-Year)

Also revealed in Figure 9 is the wide variance in per-capita alcohol expenditures across equally affluent countries. Partly that is due to differences across countries in value-added or goods-and-services taxes and in alcohol excise or consumption taxes (Table 5).

Table 5 Per-Capita Income, Excise Taxes on Alcohol Consumption by Type, and VAT/GST, High-Income Countries, 2014 (% Ad Valorem Equivalent)

Sources: Anderson and Pinilla (Reference Anderson and Pinilla2017) and Anderson (Reference Anderson2014b).

When the expenditure data are disaggregated into the three beverage types, Figures 10(a) and 10(b) reveal that wine and beer expenditures rise with aggregate expenditures. However, Figure 10(c) suggests that expenditures on spirits peak at an aggregate national expenditure level of US$27,800 per capita (in 2015 dollars) and decline thereafter.

Figure 10 Relationship Between per-Capita Aggregate Expenditure and Value of Recorded Alcohol Consumption, 80 Countries,a 2001–2015

G. Alcoholic Versus Nonalcoholic Beverages

As of 2010–2014, alcohol made up nearly two-thirds of the world's recorded expenditures on beverages, with the rest being bottled water (8%), carbonated soft drinks (15%), and other soft drinks, such as fruit juices (13%). Those beverage shares varied widely across regions (Table 6), in part because retail prices varied between countries: For all soft drinks, they ranged from an average for 2013–15 of 70 US cents per litre in Africa and the Middle East to 260 US cents in Australasia (Euromonitor International, 2016). The degree of substitutability between alcoholic and soft drink consumption may vary across countries; so too does the availability of low-cost reticulated potable water. These facts suggest further reasons to expect differences across countries in alcohol consumption volumes and mixes.

Table 6 Shares of Beverage Household Expenditure by Beverage Type, Seven Regions Spanning the World, 2010–2014 (%)

Source: Holmes and Anderson (Reference Holmes and Anderson2017).

Globally, during 2001–2015, the world's volume of alcohol consumption increased by one-quarter while that of nonalcoholic beverages rose by two-thirds. However, global retail expenditures (including taxes) on those two product groups rose by similar current US dollar amounts: 81% for alcoholic and 90% for nonalcoholic beverages (Euromonitor International, 2016). That difference between the volume and value increases for alcohol consumption is not inconsistent with the findings of the previous sub-section, in which the volume of alcohol consumption traces a much more-pronounced inverted U-shape as total expenditures rise than does the value of alcohol consumption.

V. Robustness Test

All the consumption data reported above refer only to what have been recorded by national governments; an additional amount of alcohol produced and consumed each year is not recorded. WHO (2015) has compiled estimates of those amounts for 98 countries for 2000, 2005, and 2010.

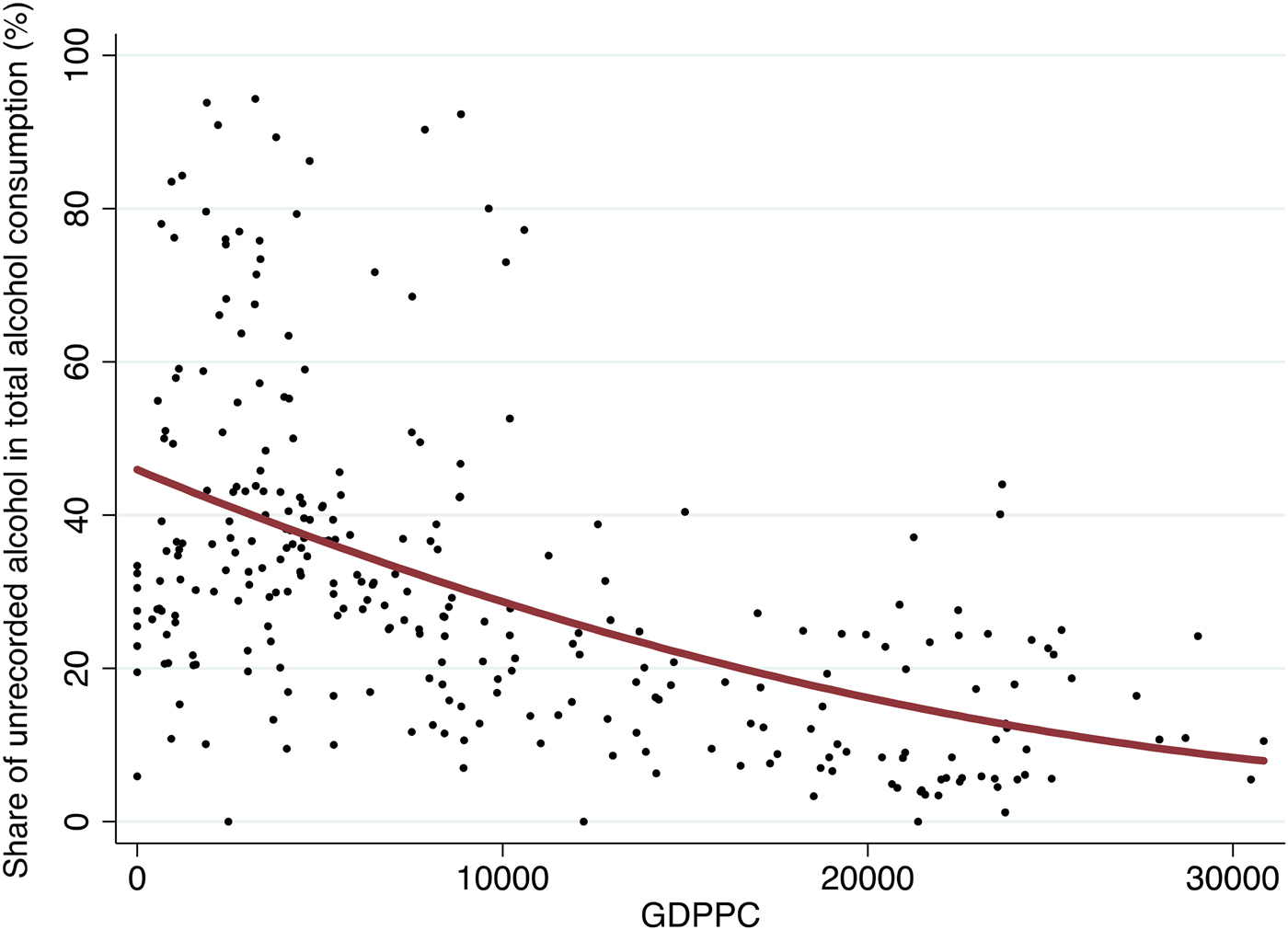

Evidently, the share of unrecorded total alcohol consumption declines with real GDP per capita (Figure 11 and Table 7),Footnote 3 thus exposing another aspect of convergence across countries in alcohol consumption – namely, in the share of national consumption that is unrecorded, which converges toward zero as per-capita income grows.

Figure 11 Relationship Between Share of Unrecorded Alcohol in Total Alcohol Consumption Volume and Real GDP per Capita,a 98 Countries, 2000, 2005, and 2010 (One Dot per Country-Year)

Table 7 Importance of Unrecorded in Total Alcohol Consumption Volume, by Region, 2000, 2005, and 2010 (Litres of Alcohol* per Capita)

a Real GDP per capita is in thousands of 1990 International Geary-Khamis dollars from www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/data.htm, updated to 2010 by taking the latest PPP estimates in 2011 dollars from the World Bank's International Comparison Project at http://icp.worldbank.org and splicing them to the Maddison series.

* litres of alcohol = LAL

Source: Compiled from data in Holmes and Anderson (Reference Holmes and Anderson2017).

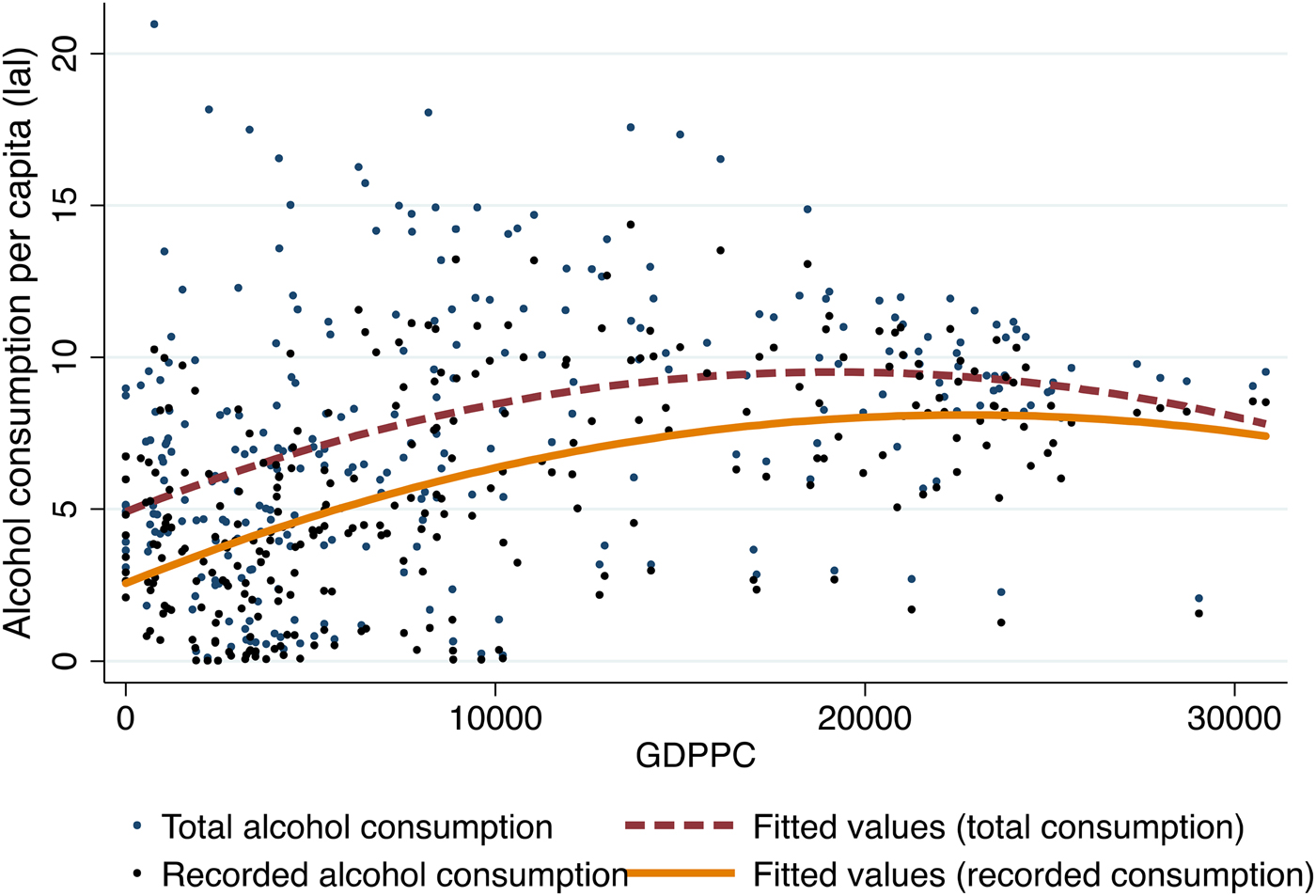

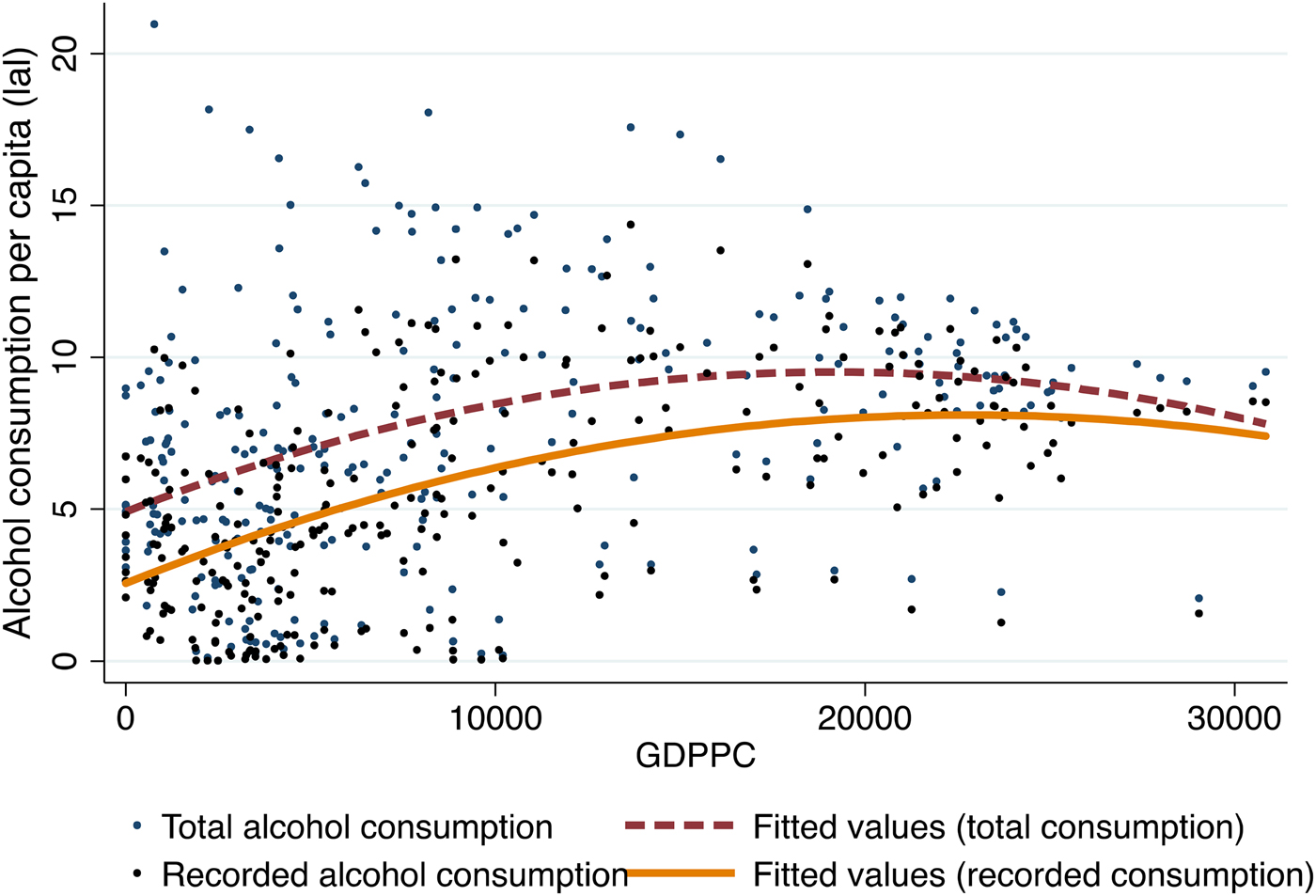

Another implication of this phenomenon is that the inverted U-shaped relationship between per-capita alcohol consumption and per-capita real GDP is flatter once unrecorded consumption is included, as shown by the quadratic fitted regression lines in Figure 12 for the 3 years and 98 countries for which estimates are available.

Figure 12 Relationships Between Alcohol Consumption Volume and Real GDP per Capita,a Recorded and Total (Recorded plus Unrecorded), 98 Countries, 2000, 2005, and 2010 (One Dot per Country-Year)

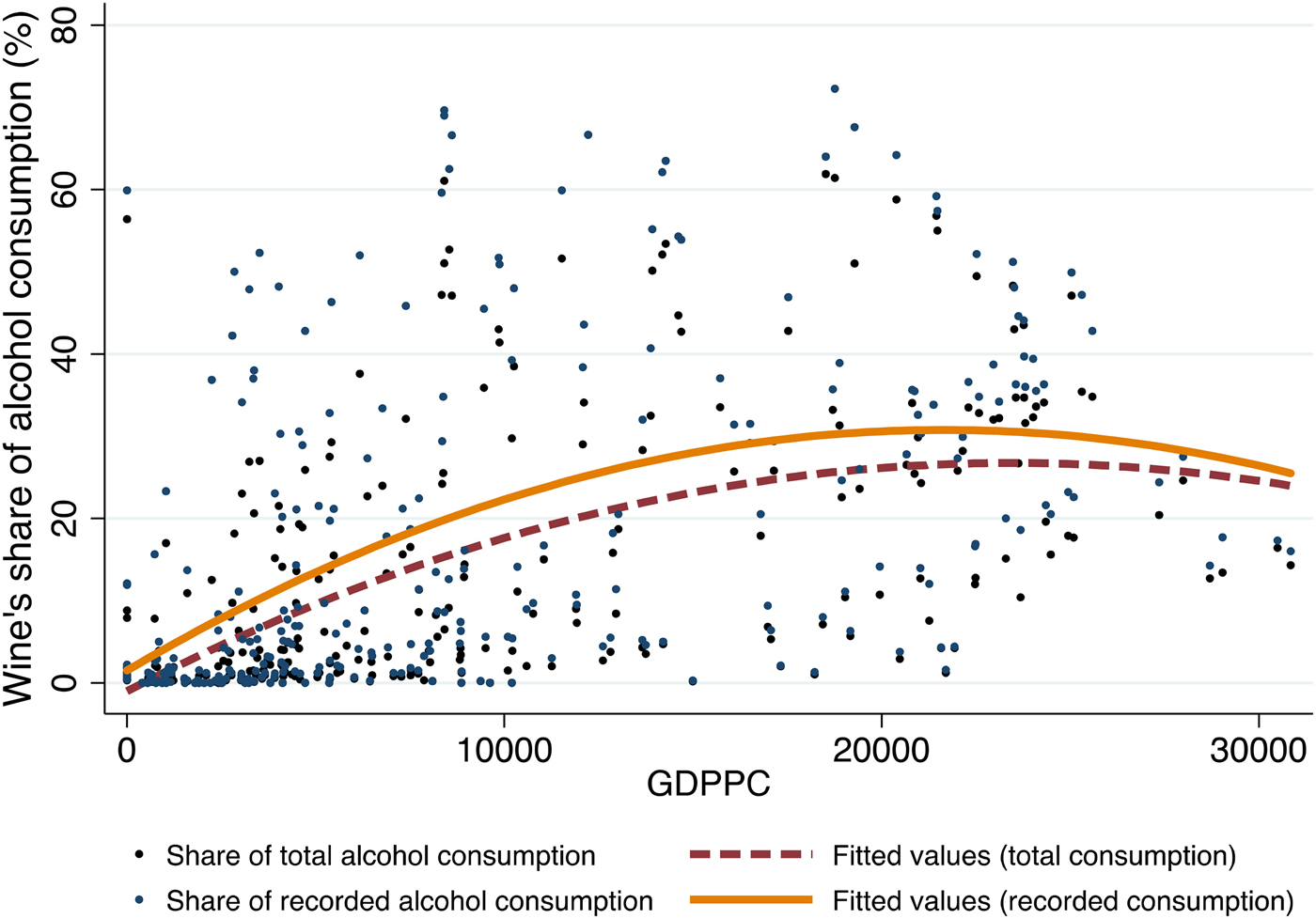

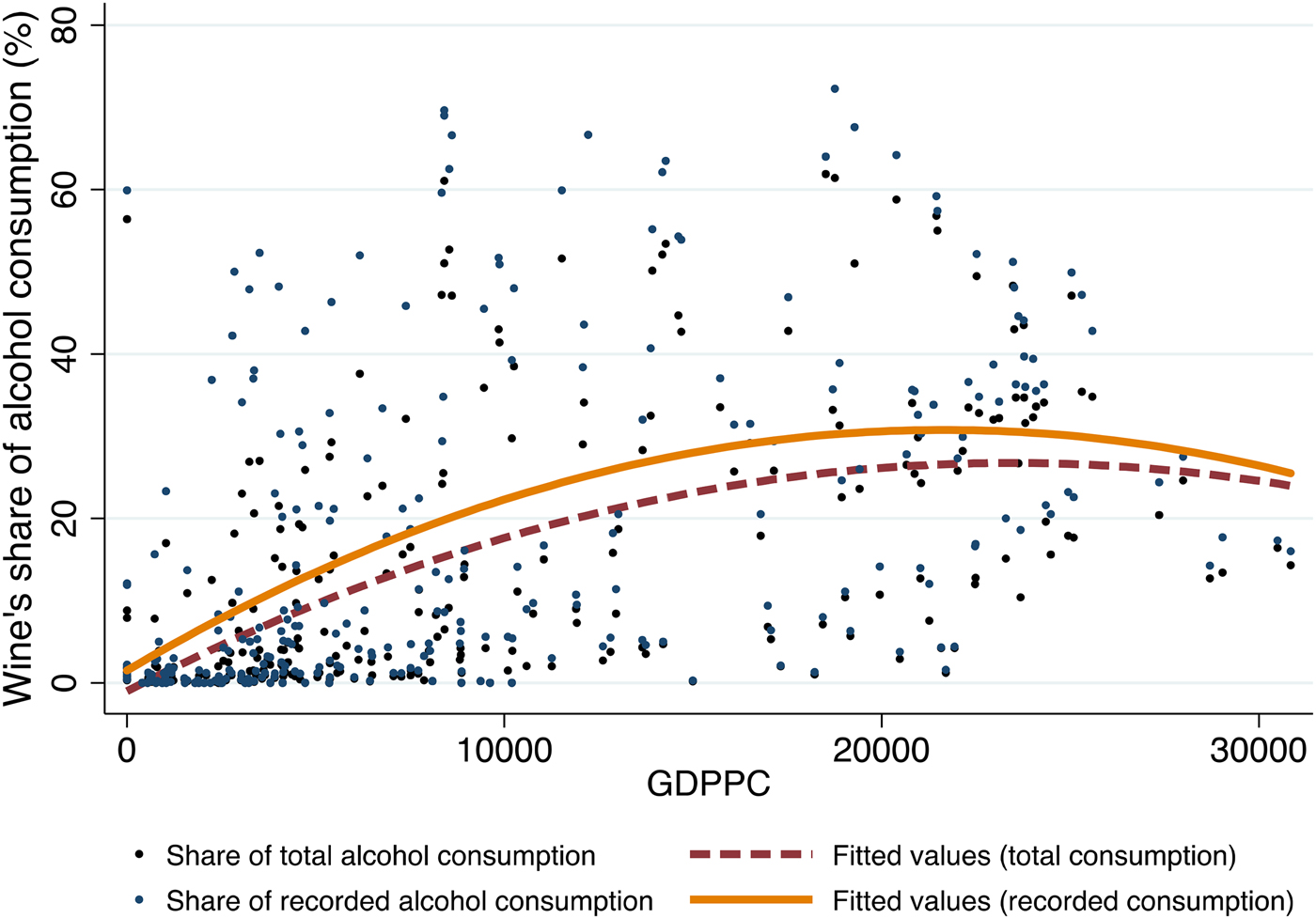

A more-specific implication is that the share of wine in total alcohol consumption globally is lower than its share of recorded alcohol consumption, because very little of that unrecorded alcohol is wine.Footnote 4 But as Figure 13 shows, when unrecorded consumption is included, the quadratic fitted regression line tracing wine's share of total alcohol consumption against real GDP per capita tends to plateau rather than turn down with higher per-capita income levels.

Figure 13 Relationships Between Wine's Share of Alcohol Consumption Volume and Real GDP per Capita, Recorded and Total (Recorded plus Unrecorded), 98 Countries, 2000, 2005, and 2010 (One Dot per Country-Year)a

VI. Conclusions

The above global data show big changes in national, regional, and global alcohol consumption patterns. At the global level, we note that during 1961–2014, wine's share of the total volume of alcohol consumption more than halved, from 34% to 15%; beer's rose by more than one-third, from 29% to 42%; and spirits’ rose only a little, from 37% to 43%. These figures reveal a trend away from equal global shares of the three beverages. At the national level, the above analysis provides a number of indicators of convergence in alcohol consumption patterns toward that changing global average mix, but also some anomalies. Key findings include the following:

-

• The per-capita volume of total alcohol consumption first rises as per-capita income rises, but beyond a threshold income level, it falls.

-

◦ However, that inverted U-shaped curve is flatter for per-capita expenditures on alcohol (at least for 2001–2015) and when unrecorded consumption is added to recorded consumption.

-

-

• Each of the three types of alcohol consumption per capita also traces out an inverted U-shaped curve over the per-capita income spectrum in volume terms, but that is true in value terms (at least for 2001–2015) only for spirits.

-

• CoV across countries in the total volume of alcohol consumption, and in the shares of each beverage in that total consumption, fell considerably over the 1961–2014 period (but least so for spirits).

-

• When countries are grouped by their main beverage focus as of 1961–1964, the share of that focus beverage in the total volume of alcohol consumption for that sub-group of countries fell over the next five decades.

-

◦ However, the consumption intensity index rose rather than fell for wine in the wine-focused group of countries, due to the wine share's falling less for that group of countries than for the world as a whole.

-

-

• In beer-focused countries, wine's share grew rapidly, whereas in wine- and spirits-focused countries, beer rose in importance.

-

• When countries are grouped by geographic region, all three beverage consumption volume intensity indexes converged toward unity for North America and Eastern Europe, but they diverged for Western Europe and Africa and the Middle East.

-

• The consumption mix similarity indexes moved closer during 2001–2015 for most regional country groups and for beer- and spirits-focused countries – but not for wine-focused countries, and only barely for Western Europe.

In short, we find strong but not unequivocal indications of convergence in national alcohol consumption patterns across the world. It remains to draw out their implications for demand elasticity estimates and to explain these evolving patterns econometrically now that we have a comprehensive global database. A next step would be to build on and extend the seminal work by Selvanathan and Selvanathan (Reference Selvanathan and Selvanathan2007) to see to what extent income, own-price, and cross-price elasticities of demand for alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages differ across countries and over time. Subsequent work could focus on explaining econometrically the cross-country differences in our two indexes in terms of such variables as beverage consumer tax rates, per-capita incomes, and trade costs.