1 Introduction

The last decade has seen an explosion of research on politics from the lens of moral psychology. In particular, research on moral foundations theory by Haidt, Graham and colleagues has demonstrated how the political divide between liberals and conservatives may have its roots in their tendency to subscribe to different moral foundations (Reference Haidt and GrahamHaidt & Graham, 2007). Reliance on different moral foundations is measured with the moral foundations questionnaire (MFQ), which assesses belief in individuals’ rights to not be subjected to harmful or unfair treatment, as well as their obligations to respect authority, to be loyal, and to adhere to norms of purity and sanctity. Results from the MFQ show that liberals care more than conservatives about harm and fairness while conservatives care more than liberals about authority, loyalty, and purity (Reference Graham, Haidt and NosekGraham, Haidt & Nosek, 2009; Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and DittoGraham et al., 2013). International MFQ data provide evidence of the cross-cultural robustness of the connection between political ideology and reliance on moral foundations (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and DittoGraham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva & Ditto, 2011).

The MFQ does not specify the agents involved in the act to be judged. For instance, one of the items used to measure reliance on the moral foundation of fairness is “whether or not someone acted unfairly”, without any further indication of who “someone” is. The design thus implicitly assumes that liberals’ and conservatives’ reliance on moral foundations when judging acts does not depend on who is acting. However, there is a body of research documenting double standards in moral judgments. Double standards have been demonstrated both among the political right (Reference AltemeyerAltemeyer, 1996) and the political left (Reference CrawfordCrawford, 2012). Most relevant to the current investigation, Reference Uhlmann, Pizarro, Tannenbaum and DittoUhlmann, Pizarro, Tannenbaum and Ditto (2009) demonstrated that cues such as victims’ race or nationality influenced participants’ application of the abstract moral principle of consequentialism, with context determining whether double standards were found most strongly among liberals or conservatives. Uhlmann et al. (2009, p. 484) concluded that “moral principles generally held to apply across situations can be selectively applied in order to fit a desired moral judgment”.

Our key hypothesis is that people are motivated to approve of agents they like and to disapprove of agents they dislike. Thus, we should expect political double standards whenever liberals and conservatives have different feelings about agents.

1.1 How blatant are people’s double standards?

We will now argue that double standards can be more or less blatant. Recall that the MFQ asks respondents about how much they rely on various moral foundations when passing moral judgment on acts. Double standards would not necessarily show up when the agents involved in the acts are specified. Namely, one interpretation of the above quotation from Uhlmann and colleagues is that, while people claim that their principles are general (i.e., blind to who the agents are), the application of these principles is nonetheless selective so that desired moral judgments are arrived at. The alternative is what we will call blatant double standards, i.e., that people explicitly claim that different principles are relevant depending on which agents are involved. For illustration of this point, consider the moral foundation of fairness. Do people claim to rely on fairness as a general principle and find excuses for applying it differently depending on which moral judgment is desired? Or do liberals and conservatives claim to rely differently on fairness depending on who is unfair to whom? We shall investigate these questions by modifying the MFQ so that agents are specified.Footnote 1

To begin with we shall examine the case when agents are specified as either liberals or conservatives. Given the extent of political ingroup-outgroup biases (Reference Ditto, Liu, Clark, Wojcik, Chen, Grady and ZingerDitto et al., 2018), this case should be particularly favorable for blatant double standards to be exhibited. After submitting the first version of the present paper we learned of a new paper by Voelkel and Brandt (in press) in which they examined the effect of modifying the MFQ by specifiying the target of acts as either liberals or conservatives (e.g., “whether or not someone acted unfairly towards a conservative person”). Evidence of double standards was indeed found. Our study extends that of Voelkel and Brandt in several ways. As detailed below, we specify not only targets of acts but also the actor, and we further distinguish between good acts and bad acts. Moreover, we extend the set of agents beyond liberals and conservatives.

Recall our key hypothesis that people are motivated to approve of agents they like and to disapprove of agents they dislike. From this hypothesis it follows that blatant political double standards should occur whenever the agents involved tend to be liked by liberals and disliked by conservatives or vice versa. To test this, we chose to focus on corporations and news media, which are agents that play important roles in contemporary American politics. Note that corporations and news media are organization-level entities; however, organizations are still perceived as moral agents (Reference Tholen, de Vries and FarazmandTholen & de Vries, 2016).

Corporations are liked more by conservatives

Conservatives in the US have more favorable attitudes towards corporations than liberals do. For instance, conservatives are more concerned about the needs of businesses (Reference McClosky and ZallerMcClosky & Zaller, 1984) and tend to dislike government regulations of corporations (e.g., Layzer, 2012), whereas liberals tend to be more distrustful of corporations (Reference Adams, Highhouse and ZickarAdams, Highhouse & Zickar, 2010).

News media are liked more by liberals

Liberals in the US have more favorable attitudes towards the media, compared to their conservative counterparts. Analyses of General Social Survey data indicate that confidence in the press tends to be higher among more liberal respondents (Reference Gronke and CookGronke & Cook, 2007). A corresponding difference is found in attitudes about regulation of news media. The Pew Research Center measured the extent to which respondents consider it important that the media can report the news without government censorship (Pew, 2015). The US data from this survey, available from Pew, show that press freedom was rated as very important by 76.4% of participants identifying as liberal compared to 70.6% of participants identifying as conservative. Thus, even though the poll was conducted during the liberal Obama administration, the support for press freedom from government interference was higher among liberals. Today, under the conservative Trump administration with its notoriously tense relationship with the press, we assume that there has been increased polarization in attitudes toward the press. An indication of such polarization is provided in a recent survey asking whether the president should have the authority to deny press credentials; most Democrats disagree whereas most Republicans agree (Freedom Forum Institute, 2018, p. 13).

1.2 Hypotheses about rights, obligations, and virtues

There are typically two types of agents involved in morally charged acts: victims and perpetrators. Depending on whether the victim or the perpetrator is the focal agent, a moral judgment of an act can be seen as relying either on the victim’s right to not be treated poorly or the perpetrator’s obligation to not treat others poorly. For instance, the moral foundation of fairness can be regarded as people having a right to not be treated unfairly as well as an obligation to not treat others unfairly.

For people to obtain a desired moral judgment, we expect them to exhibit double standards in different directions for rights and obligations. People should be more concerned about rights to not be treated poorly for victims they like more, but be less concerned about obligations to not treat others poorly for perpetrator they like more. When focal agents are liked by conservatives but not by liberals (e.g., corporations and conservatives), blatant double standards should therefore take the form of conservatives showing more concern about rights and less concern about obligations than liberals do. The opposite pattern should be found when focal agents are liked by liberals but not by conservatives (e.g., news media and liberals).

So far our argument is based on moral judgments being about acts where there is a victim and a perpetrator. However, morality also concerns virtuous acts — the “prescriptive domain” instead of the “proscriptive domain” (Reference Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh and HeppJanoff-Bulman, Sheikh & Hepp, 2009). While the MFQ is predominantly focused on the proscriptive domain, it also involves a few items where someone performs a virtuous act. To obtain a desired moral judgment in such cases, people should find virtuous acts more relevant when they are performed by someone they like more.

In formal terms, we have three hypotheses about blatant political double standards. (H1) Individuals’ reliance on rights should be shaped by an interaction between their political ideology and the focal agent: stronger reliance on rights for victims that are held in higher regard within that ideology. (H2) Reliance on obligations should be shaped by the same interaction with the opposite sign compared to rights: weaker reliance on obligations for perpetrators that are held in higher regard within the individual’s ideology. (H3) Reliance on virtues should be shaped by the same interaction with the same sign as for rights: stronger reliance on virtues for agents that are held in higher regard within the individual’s ideology.

Note that rights, obligations, and virtues could be formulated with respect to any specific moral foundation. For brevity, we will use the suffix “-R” to denote rights with respect to a given moral foundation (harm-R, fairness-R, etc.). Similarly, we use the suffix “-O” to denote obligations and “-V” to denote virtues.Footnote 2

1.3 Outline of studies

Recall that prior research has found that, compared to conservatives, liberals tend to rely more on the harm and fairness foundations and less on the foundations of authority and liberty from government interference. Following our above argument, we conducted a series of studies to examine how political double standards may change these patterns when liked or disliked agents are specified. All studies were conducted in 2018.

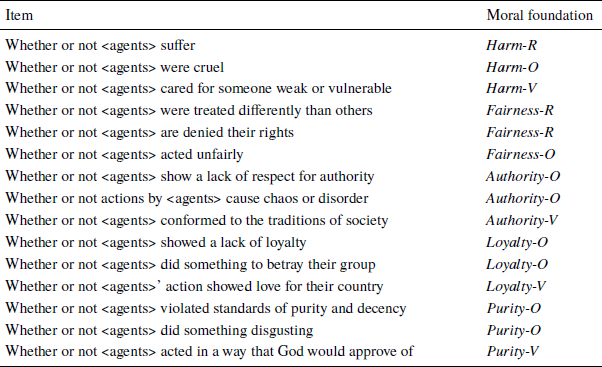

The MFQ measures reliance on five moral foundations — harm, fairness, authority, loyalty, and purity — with three relevance items for each (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and DittoGraham et al., 2011). In Study 1 we examined, in a US sample, how liberal and conservative participants responded to these relevance items when the unspecified agent “someone” was replaced with a specific focal agent, either “conservatives” or “liberals”. This resulted in 3 rights items, 8 obligations items, and 4 virtue items, see Table 1.

Table 1: Items used to measure reliance on moral foundations in Study 1

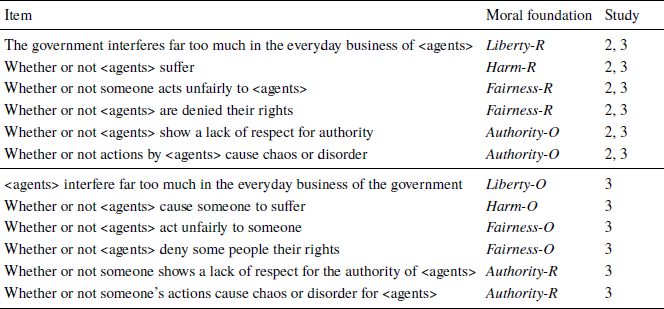

We also wanted to examine whether double standards extend to organizational agents. These studies used only five out of fifteen relevance items from the MFQ, as the other items did not apply as readily to organizational agents. In addition we included an item on liberty from government interference in one’s everyday business, which has been suggested as a sixth moral foundation (Reference Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto and HaidtIyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto & Haidt, 2012). Using these items, Study 2A focused on the right to avoid government interference in one’s everyday life, the right to not be harmed, the right to not be treated unfairly, and the obligation to not disrespect authority. See the top half of Table 2. We study unspecified agents (”people”) as well as the four specific focal agents (”corporations”, “news media”, “conservatives”, and “liberals”). Study 2A was conducted in the United States. We also conducted a replication with a sample from the United Kingdom, focusing only on the organizational agents (Study 2B). Study 3A replicated and extended the first study by measuring feelings about the focal agents and by including role reversals from victim to perpetrator and vice versa, see the bottom half of Table 2. Again we conducted a replication in the UK (Study 3B).

Table 2: Items used to measure reliance on moral foundations in Study 2 and Study 3

2 Study 1

The aim of our first study was to examine political double standards with respect to reliance on rights, obligations, and virtues.

2.1 Method

Inclusion criteria

As our research question is how focal agents interact with political ideology we include only participants who place themselves on a scale from liberal to conservative. This criterion applies to all studies in this paper.

Participants

A total of 300 participants (47% female; age range from 18 to 75 years) were recruited among US users of Amazon Mechanical Turk for a payment of 0.50 US dollars. We made use of prescreening criteria to obtain a balanced sample of liberals and conservatives. Our analyses are based on the 286 participants who placed themselves on a seven-point liberal-to-conservative scale (122 liberals, 37 moderates, and 127 conservatives).Footnote 3

Moral foundations items

We adapted the full set of 15 relevance items from the MFQ. All but one of these items mention the unspecified agent “someone” or “some people”. Depending on condition we changed the unspecified agent to “conservatives” or “liberals”. The exceptional item mentioned “actions”, which we changed to “actions by conservatives” or “actions by liberals”. See Table 1 for the full set of items.Footnote 4

Responses were given on a 6-point response scalefrom not at all relevant to extremely relevant and coded from 0 to 5. For each moral foundation, responses to items of the same type were averaged. We acknowledge that the low number of items, only one or two per moral foundation, makes the measures not very reliable.

Procedure

Every participant was given the above 15 moral foundations items in one of two conditions (to which participants were randomly assigned): “conservatives” or “liberals”. Thereafter, we measured the participants’ political ideology on a 7-point scale from strongly liberal, coded 1, to strongly conservative, coded 7, plus three additional options: libertarian, other, and don’t know).

2.2 Results and Discussion

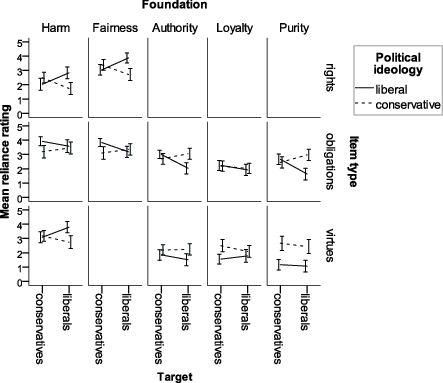

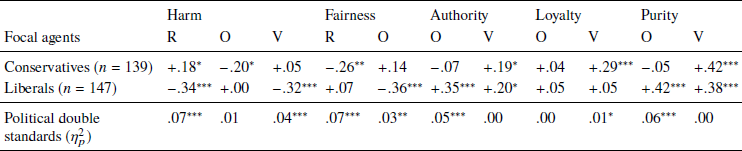

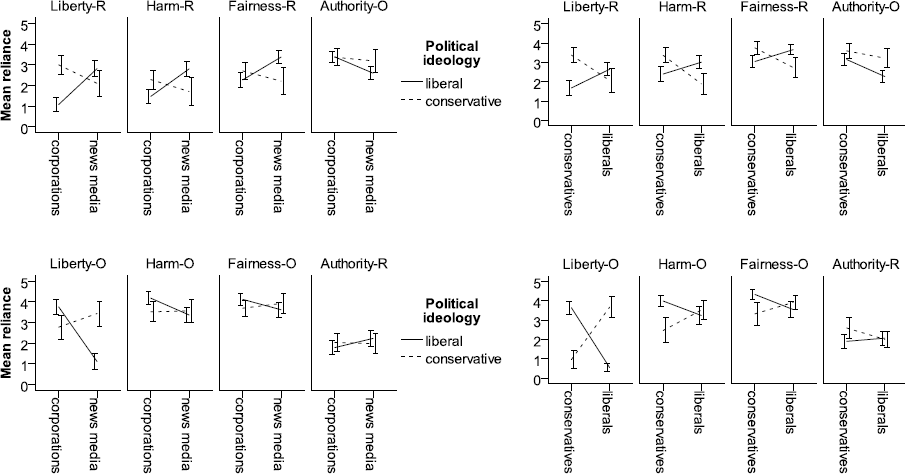

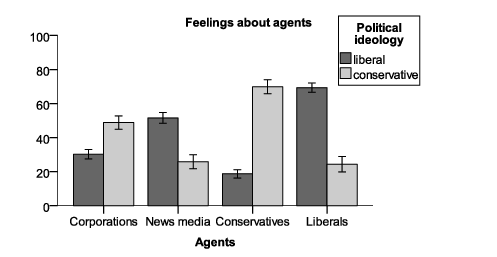

Figure 1 illustrates for each focal agent and each item type how liberals (steps 1 through 3 on the ideology scale) and conservatives (steps 5 through 7 on the ideology scale) differed in their reliance on each moral foundation. Political double standards are evident wherever the two lines — representing conservative and liberal participants’ reliance on a certain item type for a certain moral foundation — have different slopes when going from conservative agents (left) to liberal agents (right). Table 3 reports the corresponding correlations between reliance on an item and political ideology (coded as number between 1 and 7).

Figure 1: For focal agents “conservatives” vs. “liberals”, political double standards were exhibited for most moral foundations, such that both conservative and liberal participants tended to rely more on rights, less on obligations, and more on virtues for their political ingroup. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3: Results from correlational analyses and ANOVAs in Study 1

† p< .1

* p< .05

** p< .01

*** p< .001

Note: R stands for rights to not be treated poorly, O for obligations to not treat others poorly, and V for virtues. “Political double standards (![]() )” refers to the effect size of the interaction between agents and political ideology as obtained from an ANOVA.

)” refers to the effect size of the interaction between agents and political ideology as obtained from an ANOVA.

To formally assess evidence for double standards we conducted an ANCOVA for each of the 11 combinations of moral foundation and item type, using agent as a factor, political orientation as a covariate (using the full 1–7 scale), and the interaction between agent and political orientation. The bottom row of Table 3 reports the effect size and statistical significance of the interaction. A significant interaction, indicating political double standards, was exhibited in the majority of cases: harm-R, harm-V, fairness-R, fairness-O, authority-O, loyalty-V, and purity-O. As Figure 1 shows, participants consistently tended to rely more on rights, less on obligations, and more on virtues for their political ingroup than for their outgroup. Following Cohen’s guidelines for effect sizes we shall refer to a partial eta squared of 0.01 as “small”, 0.06 as ”medium”, and 0.14 as “large”. Thus the significant interactions ranged in effect size from small to medium.

In conclusion, Study 1 demonstrated that reliance on moral foundations, as measured by items where “someone” is involved in a scenario, depends in a predictable way on who that someone is.

3 Study 2A

Study 1 established political double standards in reliance on moral foundations when agents were specified as liberals or conservatives. To examine the scope of this effect, the remaining studies also examine organization-level agents, including corporations and the news media.

3.1 Method

Design

This study had five between-subjects conditions, varying whether the focal agents were “people”, “corporations”, “news media”, “conservatives”, or “liberals”. The purpose was to investigate how correlations between participants’ political ideology and their reliance on various moral foundations depend on the focal agents.

Participants

After recruiting 500 participants among American users of Amazon Mechanical Turk (mturk.com) for a payment of 0.35 US dollars, we obtained a sample of 475 participants with self-reported political ideology on a scale from liberal to conservative (255 liberals, 96 moderates, and 124 conservatives; 55% female; age range from 18 to 81 years, M = 36 years).

Moral foundations items with specified agents

Using the criterion to include MFQ relevance that could also apply to corporations and news media, we identified five useful relevance items: one item relating to harm, two items relating to fairness, and two items relating to authority. We also included a statement item on liberty from government interference. The six selected items were adapted to allow specification of a focal agent. See Table 2. Each item had a 6-point response scale. For the statement item the scale ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Responses were coded from 0 to 5. The two fairness ratings were averaged, and similarly for the two authority ratings (the internal consistency was adequate in both cases, Cronbach’s α>.7). Again we acknowledge that the low number of items, only one or two per moral foundation, makes the measures not very reliable.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of five conditions, so that 100 participants were assigned to each condition. Conditions differed only on how focal agents were specified (as people, corporations, news media, conservatives, or liberals). Every participant was given the six moral foundations items with agents specified according to the condition they were assigned to. Participants’ political ideology was measured on a 7-point scale as in Study 1. We also measured (but do not use) participants’ approval of President Trump on a 7-point scale from strongly disapprove to strongly approve.

3.2 Results

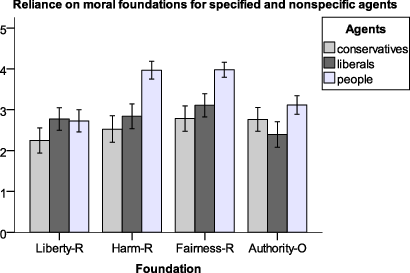

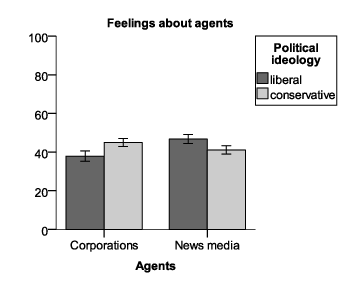

We first checked how mean levels of reliance on moral foundations varied depending on whether agents were nonspecific (”people”) or specified as liberals or conservatives. See Figure 2, where two moral foundations stand out. Reliance on Harm-R and Fairness-R was considerably higher for people than for liberals/conservatives. Thus, the specification of agents as liberals or conservatives made some participants reluctant to state that rights with respect to harm and fairness were highly relevant. Our interpretation is that these participants may have interpreted the questions as being about how relevant it is to their moral judgment that agents are liberals/conservatives, that is, that the group membership became the emphasis rather than the moral foundation. For the main purpose of our study this does not matter much, as this interpretation just emphasizes the application of double standards.

Figure 2: Mean reliance on various moral foundations for specified focal agents (”conservatives” and “liberals”) and nonspecific agents (”people”). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

We are mainly interested in how reliance on moral foundations for specified agents vary with political ideology. Correlations are presented in Table 4. The standard findings on moral foundations is that political conservatism is associated with less reliance on harm and fairness and greater reliance on authority and liberty, and that the harm foundation tends to show the weakest association with ideology (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and DittoGraham et al., 2011; Reference Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto and HaidtIyer et al., 2012). Results for the nonspecific “people” (top row of Table 4) replicated these standard findings, serving as a validation of our adapted items.

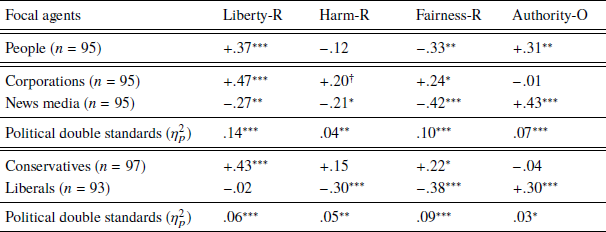

Table 4: Results from correlational analyses and ANOVAs in Study 2A

† p< .1

* p< .05

** p< .01

*** p< .001

Note: Entries are correlations between reliance on the moral foundation for a specific agent and political ideology. “Political double standards (![]() )” refers to the effect size of the interaction between agents and political ideology as obtained from an ANOVA.

)” refers to the effect size of the interaction between agents and political ideology as obtained from an ANOVA.

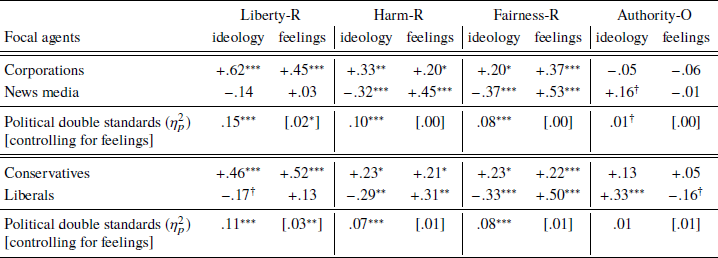

We now move on to the main focus of our study: whether specifying agents elicits political double standards in reliance on moral foundations. First consider the organizational agents “corporations” vs. “news media”. The second and third rows of Table 4 shows that more conservative participants tended to rely more on rights (Liberty-R, Harm-R, Fairness-R) for corporations, but rely less on those same rights for news media. The opposite pattern was observed for obligations (Authority-O). This interaction between focal agents and political ideology is evidence of political double standards. To further assess this interaction we conducted an ANCOVA for each of the four moral foundations, using agent as a factor, political ideology as a covariate, and the interaction between two. As reported in the fourth row of Table 4, the interaction was statistically significant for all four outcomes, with the effect size measure ![]() ranging from .04 to .14, that is, from small to large.

ranging from .04 to .14, that is, from small to large.

The remainder of Table 4 gives results for the political agents. Results for “conservatives” were remarkably similar to those obtained for “corporations”, and similarly for “liberals” and “news media”. Again, the interactions between agents and political ideology were consistently significant, with ![]() ranging from .03 to .09, that is, from small to medium.

ranging from .03 to .09, that is, from small to medium.

For graphical illustration we recoded political ideology as a binary variable, liberal vs. conservative, with moderates excluded. Figure 3 shows how reliance on moral foundations among liberals and conservatives changed when the focal agents changed.

Figure 3: Liberals’ and conservatives’ mean reliance on various moral foundations for focal agents “corporations” vs. “news media” (left panel) and “conservatives” vs. “liberals” (right panel) in Study 2A. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

3.3 Discussion

We found clear evidence of political double standards in reliance on moral foundations. For focal agents that conservatives (presumably) tend to like more — corporations and conservatives — conservatives relied more than liberals on rights and equally much on obligations. For agents that liberals (presumably) like more — news media and liberals — it was instead liberal participants who relied most on rights and least on obligations. These findings are consistent with our hypotheses that warm feelings for a victim should make reliance on rights stronger whereas warm feelings for a perpetrator should make reliance on obligations weaker.

4 Study 2B

We replicated Study 2A with a British sample to assess whether the results are specific to US political culture. We left out the agents “conservatives” and “liberals” which do not have the same connotations in the UK as in the US.

4.1 Method

Prior work has found that the association between political ideology and reliance on moral foundations, as measured by the MFQ, is somewhat weaker among UK respondents, compared to US respondents (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and DittoGraham et al., 2011). We therefore decided on a larger sample size by condition than in Study 2A. By leaving out the focal agents “conservatives” and “liberals” we had three conditions instead of five.

Participants

After recruiting 450 participants among UK users of Prolific (prolific.ac) for a payment of 0.50 British pounds, using Prolific’s prescreening criteria to obtain a balanced sample of liberals and conservatives, we obtained a sample of 432 participants who placed themselves on the liberal-to-conservative scale (162 liberals, 97 moderates, and 173 conservatives; 56% female; age range from 18 to 80 years, M = 37 years).

Procedure

Every participant was given the same moral foundations items as in Study 2A in one of three conditions: “people”, “corporations”, and “news media”. Following Graham et al. (2011) our measure of participants’ political ideology clarified the concepts of liberal and conservative as meaning left-wing and right-wing, respectively: “What is your political position on a scale from very liberal (i.e., very left-wing) to very conservative (i.e., very right-wing)?” (coded from 1 to 7).

4.2 Results

How reliance on moral foundations correlated with political ideology for different agents is presented in Table 5. Comparison with the results from Study 2A reveals both differences and similarities.

Table 5: Results from correlational analyses and ANOVAs in Study 2B

For the nonspecific agent, “people”, UK results were on the whole similar to those obtained in the US. However, political ideology correlated more weakly with reliance on liberty from government interference in the UK sample.

For the specific agents, “corporations” vs. “news media”, results were substantially weaker in the UK sample. The only moral foundation that yielded significant political double standards was liberty from government interference, and still only at a fraction of the effect size found in Study 2A.

4.3 Discussion

The aim of Study 2B was to examine whether the findings from the US sample in Study 2A would replicate in the UK. For non-specific agents we did indeed replicate the well-known relationship between political ideology and reliance on various moral foundations: conservatives scored lower on harm and fairness, but higher on liberty from government and authority. However, when focal agents were specified as “corporations” or “news media”, we did not observe the political double standards we found in the US. This could be due to Americans being more prone to double standards than their British counterparts, but this seems unlikely. Under the hypothesis that double standards arise from different desired moral judgments for different agents, a more plausible explanation is that feelings about corporations and news media are less tied to political ideology in the UK than in the US (so that people’s double standards do not show up as political double standards). We examine this in the next set of studies.

5 Study 3A

We conducted a further study to examine the hypothesis that reliance on moral foundations for specific agents depends on the respondent’s feelings about these agents. Can differences between liberals’ and conservatives’ feelings about agents account for shifts in their relative reliance on various moral foundations?

Moreover, we examine our hypothesis about how double standards depend on whether the focal agent is a victim or a perpetrator. Recall from the introduction our hypotheses about how feelings for agents should interact with whether it is reliance on rights or reliance on obligations that is measured. Warm feelings for a victim should make reliance on rights stronger, whereas warm feelings for a perpetrator should make reliance on obligations weaker. The differences observed in Study 2A between reliance on rights (liberty-R, harm-R, fairness-R) and reliance on obligations (authority-O) are consistent with this hypothesis. To achieve a stronger test, we here experimentally manipulate whether the focal agent is a victim or a perpetrator.

5.1 Method

Participants

After recruiting 480 participants among US users of Amazon Mechanical Turk (mturk.com) for a payment of 0.50 US dollars, we obtained a sample of 452 participants who placed themselves on the liberal-to-conservative scale (251 liberals, 81 moderates, and 120 conservatives; 45% female; age range from 19 to 74 years, M = 38 years).

Role-reversal of agents in the moral foundations items

From the set of items used in Study 2A we created a new set by changing the wording of each item to reverse the roles from perpetrator to victim or vice versa. See Table 2.

Note that role-reversal of the liberty item yielded an item that may stretch the boundaries of the liberty concept: “<agents> interfere far too much in the everyday business of the government”. Although usually not cast as a question of liberty, this item seems capture many facets of contemporary US politics. For instance, by conducting investigations of the executive branch of the federal government, liberals and news media may be seen as interfering with its everyday business. Similarly, corporations may be seen as interfering with government by offering various incentives to politicians to act in their interests. The current conservative president may be seen as interfering with the everyday business of government by installing heads of agencies that work against the agencies’ purpose.

Response scales and coding were identical to those in Study 1.

Study design

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, defined by whether agent roles were as in Study 2 or role-reversed. To decrease the number of participants needed, every participant was given the same items twice, once for organizational agents (corporations or news media) and once for political agents (conservatives or liberals). All four combinations were equally common. We can think of combinations as being either “congruent” (corporations+conservatives, news media+liberals) or “incongruent” (corporations+liberals, news media+conservatives). Our main analysis pools congruent and incongruent combinations, but we also consider whether results differ between congruent and incongruent combinations.

Procedure

Every moral foundation item was presented twice, first for the political agent and, directly afterwards, for the organizational agent. We also measured participants’ political ideology on the same scale as in previous studies. Finally, participants in all conditions were asked for their feelings about each of the four agents (i.e., corporations, news media, conservatives, liberals) on a “feeling thermometer” from 0 to 100.

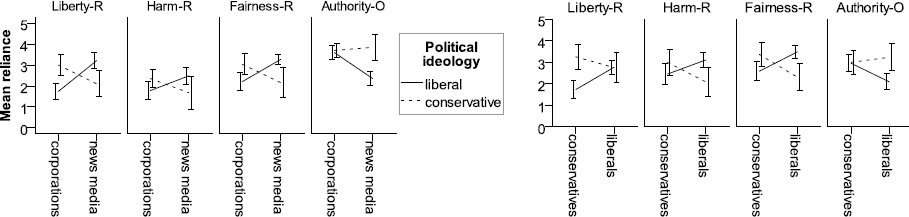

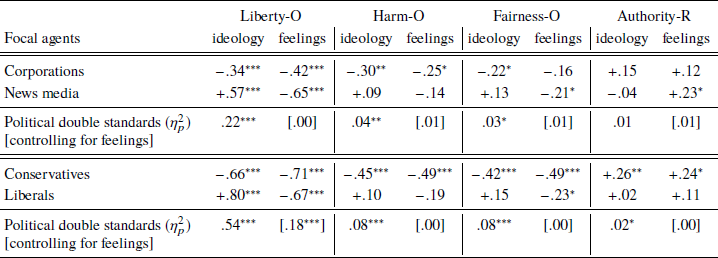

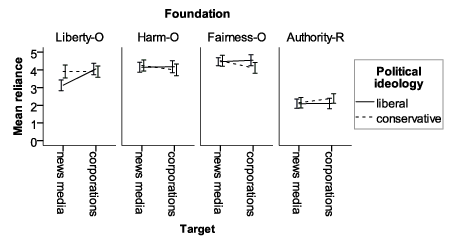

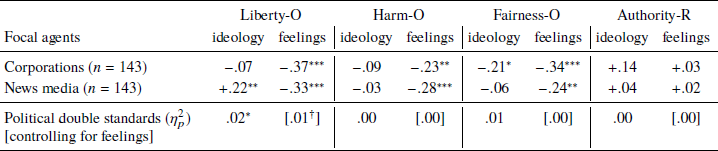

5.2 Results

Replication of Study 2A

In half the conditions, focal agents had the same roles as in Study 2A, that is, items covered rights with respect to liberty, harm, and fairness, as well as obligations with respect to authority. The top panel of Figure 6 shows the reliance on moral foundations among conservatives and liberals for each focal agent in these conditions. Note that the results of Study 2A were mostly replicated (compare with Figure 3). Specifically, double standards in reliance on moral foundations were clearly evident for liberty, harm, and fairness. The interaction between political ideology and focal agents was assessed using ANOVAs as in the previous studies. The interaction was very strong for liberty, small to medium for harm and fairness, and not significant for authority, see Table 6. We also conducted the same analyses separately for participants in congruent and incongruent conditions. The qualitative pattern of results was the same in both conditions. However, the effect sizes of the interaction by which we measure political double standards tended to be about twice as large in the congruent condition than in the incongruent condition. For instance, ![]() values for political agents depending on congruence or incongruence with organizational agents were .09 vs. .05 for Liberty-R, .10 vs. .03 for Harm-R, .10 vs. .04 for Fairness-R, and .02 vs. .00 for Authority-O.

values for political agents depending on congruence or incongruence with organizational agents were .09 vs. .05 for Liberty-R, .10 vs. .03 for Harm-R, .10 vs. .04 for Fairness-R, and .02 vs. .00 for Authority-O.

Figure 6: In the Study 3A condition where agent roles were the same as in Study 2A, similar results on double standards in reliance on moral foundations were obtained for agents “corporations” vs. “news media” (top left panel) as well as for “conservatives” vs. “liberals” (top right panel). When agent roles were reversed, all results on double standards in reliance on moral foundations were also reversed (bottom panel). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 6: Results from correlational analyses and ANOVAs in the condition in Study 3A that replicated Study 2A

† p< .1

* p< .05

** p< .01

*** p< .001

Note: Entries are correlations between reliance on the moral foundation for a specific agent and political ideology (”ideology” columns) or feelings about the agent (”feelings” columns). Cell sizes range between 109 and 114. “Political double standards (![]() )” refers to the effect size of the interaction between agents and political ideology as obtained from an ANOVA. Note that the political double standard effects tend to disappear when we control for feelings about the agent, see numbers within brackets.

)” refers to the effect size of the interaction between agents and political ideology as obtained from an ANOVA. Note that the political double standard effects tend to disappear when we control for feelings about the agent, see numbers within brackets.

Comparing reliance on rights and obligations for the same moral foundation

We now turn to the conditions where agent roles were reversed. The bottom panel of Figure 6 shows how this role reversal led to reversal of which ideological group relied more on each moral foundation. Specifically, reliance on obligations with respect to liberty, harm, and fairness tended to be lower in the ideological group that have warmer feelings about the agent. The interaction between political ideology and agents was very strong for liberty, medium-sized for harm and fairness, and small for authority. See Table 7. We also conducted the same analyses separately for participants in congruent and incongruent conditions and again obtained the same qualitative pattern of results in both conditions, with effect sizes larger in the congruent condition than in the incongruent condition. For instance, ![]() values for political agents depending on congruence or incongruence with organizational agents were .54 vs. .53 for Liberty-O, .13 vs. .04 for Harm-O, .13 vs. .05 for Fairness-O, and .01 vs. .02 for Authority-R.

values for political agents depending on congruence or incongruence with organizational agents were .54 vs. .53 for Liberty-O, .13 vs. .04 for Harm-O, .13 vs. .05 for Fairness-O, and .01 vs. .02 for Authority-R.

Table 7: Results from correlational analyses and ANOVAs in the condition in Study 3A that role-reversed Study 2A

Are political double standards accounted for by feelings for agents?

As expected, political ideology (coded high for conservative) was positively correlated with warm feelings about corporations, r=.39, and conservatives, r=.74, and negatively correlated with feelings about news media, r=−.43, and liberals, r=−.67. Figure 5 illustrates the large differences between liberals’ and conservatives’ feelings for the four focal agents.

Figure 4: In Study 2B, with a UK sample, political double standards with respect to agents “corporations” vs. “news media” were much weaker than in the US sample in Study 2A. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 5: In Study 3A, conservatives in the US were found to have quite warm feelings about corporations and conservatives but cold feelings about news media and liberals. The opposite held for liberals. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of mean values.

Tables 6 and 7 report, for each focal agent, how reliance on moral foundations correlated with feelings about the agent and also how the political double standards (i.e., the interaction between ideology and agents) tended to disappear when feelings for the agent were included as a covariate in the ANOVA. This is consistent with political double standards being driven by different feelings about the agents among conservatives and liberals.

5.3 Discussion

In our previous study (Study 2A), participants were not forced to consider whether they would respond differently for another agent. Study 3A replicated the finding of double standards in reliance on moral foundations among US liberals and conservatives, even though every Study 3A participant reported their reliance on moral foundations for two different focal agents, which arguably make the double standards even more blatant. However, participants exhibited somewhat smaller double standards in conditions where the two focal agents were “incongruent” (e.g., conservatives and news media), suggesting that this condition made participants more self-conscious of exhibiting double standards. If future research would include both rights and obligations in a within-subject design, we would expect a similar partial decrease in double standards.

Moreover, this study verified the validity of the assumption that conservatives and liberals tend to feel very differently about our focal agents. Importantly, these feelings accounted for the observed pattern of double standards.

Finally, the study established that the role of the agent — victim or perpetrator — is crucial for how double standards in reliance on moral foundations are expressed. For a fixed moral foundation, participants tended to rate rights to not be treated poorly as more relevant for agents they liked, but rate obligations to not treat others poorly as more relevant for agents they disliked.Footnote 5

6 Study 3B

In Study 2B we found little political double standards about news media and corporations in the UK, compared to the US. Our hypothesis was that this finding reflected a difference between the countries in how aligned feelings about these agents are with political ideology. The main aim of Study 3B was to test this by measuring feelings about these agents in the UK and examine (1) how feelings about agents correlate with political ideology and (2) how feelings about agents correlate with reliance on rights and obligations for the same agents. To limit participant costs, we did not replicate all conditions of Study 3A but focused on the novel condition in which roles were reversed.

6.1 Method

Participants

After recruiting 300 participants among UK users of Prolific (prolific.ac) for a payment of 0.50 British pounds, we obtained a sample of 286 participants who placed themselves on the liberal-to-conservative scale (124 liberals, 45 moderates, and 117 conservatives; 64% female; age range from 18 to 80 years, M = 38 years).

Procedure

Each participant was given the role-reversed moral foundations items from Study 3A in either of two conditions: “corporations” or “news media”. They were followed by the same seven-step measure of political ideology and the feelings thermometer for both agents.

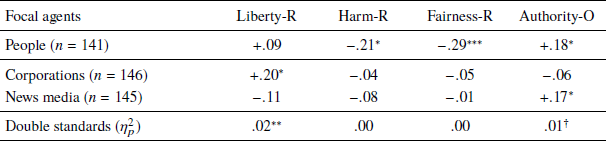

6.2 Results and discussion

Figure 7 shows differences between the political left and the political right in the UK in their feelings about corporations and news media. The differences were in the same direction as in the US but much smaller. In other words, how aligned people’s feelings about corporations and news media are with their political views appears to vary between countries.

Figure 7: In the UK there were very small differences between conservatives and liberals in their feelings about corporations (slightly warmer among conservatives) and news media (slightly warmer among liberals). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of mean values.

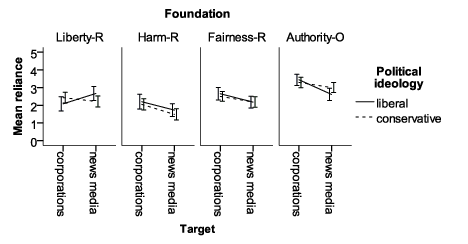

Figure 8 reports how reliance on moral foundations correlated with political ideology. Note that the interactions between political ideology and agents were very small. Thus our finding of weaker politicization of corporations and news media in the UK than in the US was mirrored by a weaker politicization of reliance on moral foundations for these agents.

Figure 8: In Study 3B, with a UK sample, the interaction between political ideology and the focal agents (corporations vs. news media) was much weaker than in the US sample in Study 3A. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 8 also reports that feelings about agents predicted reliance on moral foundations also in the UK. Thus there were still double standards in the UK — only not based on political ideology for these particular agents.

Table 8: Results from correlational analyses and ANOVAs in Study 3B

7 General discussion

The original Moral Foundations Questionnaire examines people’s reliance on moral foundations when judging acts in which the agents are not specified. Here we have broadened the scope by examining how people’s reliance on moral foundations depends on who are involved in the act to be judged. Across three studies we found that specifying agents changes how individuals claim to rely on moral foundations. We now discuss several features of these findings.

Interpretations of items

An important observation is that when we specified agents, reliance on the harm and fairness foundations showed a substantial decrease compared to when agents are nonspecific (Study 2A). This indicates that items may be interpreted differently when agents are specified. It is possible that some respondents interpreted the question as asking to what extent they employ double standards.

Feelings about agents

Our key hypothesis is that double standards in reliance on moral foundations arise when people like some agents more than others (and therefore desire different moral judgments for these agents). Our studies supported this hypothesis.

Different kinds of agents

We studied two different kinds of agents that we expected Americans would have polarized feelings towards: political groups (conservatives vs. liberals) and organizations (corporations vs. news media). Political double standards were observed for both kinds of agents. Indeed, as Figure 6 shows, the two kinds of agents yielded both similar sizes double standards and similar absolute levels of reliance on moral foundations. These findings support an extended scope of moral foundations theory. People appear to readily apply at least some moral foundations even to actors that are not people but organizations. It is conceivable that future work may discover additional moral domains that apply mainly to corporate actors.

Rights, obligations, and virtues

When specifying agents that are involved in an act to be judged, it becomes necessary to distinguish between two roles. Agents may be victims of others’ behavior, in which case the relevant moral principles are what rights they have to not be poorly treated. Alternatively, agents may be perpetrators victimizing others, in which case the relevant moral principles are obligations to not treat others poorly. In our examples, rights and obligations are paired, in that obligations are justified as ways to honor rights. But the parallelism disappears if agents are specified and people have double standards. Indeed, we found that people tend to find rights more relevant for agents they like, but found exactly corresponding obligations more relevant agents they dislike.

Agents may also be behaving virtuously, such as caring for someone weak or vulnerable, or showing love for their country. When we measured the relevance of virtuous behavior for people’s moral judgments, political double standards showed up again. Liberal participants tended to find caring for the weak and vulnerable particularly relevant when it was liberals behaving virtuously. Conservative participants similarly tended to find it particularly relevant when it was conservatives’ action that showed love for their country.

Differences in political double standards for different moral foundations

The political double standards we have documented tended to be stronger for liberty from government interference than for other moral foundations. The very strongest double standards arose when we reversed the roles to be about agents interfering in the everyday business of the government (Study 3A). Conservatives think that liberals and news media interfere in government business far too much, whereas liberals strongly disagree. This could have been a sign of conservatives simply caring more about interference with government business, but it is not. Namely, when such interference was done by conservatives or corporations instead, it was liberals who cared more about it. Future research should investigate why political double standards are particularly strong for these judgments. It could be that they are more permissible in this domain, since conservatives and liberals will clearly have divergent views on who should run the government.

Among the five original moral foundations, it is less clear whether political double standards are stronger for some foundations than for others. Although we sometimes observed stronger double standards with respect to harm and fairness than with respect to authority, loyalty, and purity, we have little faith in this pattern reflecting any deeper difference between the foundations. For instance, we might observe stronger double standards with respect to loyalty if we were to role-reverse the loyalty items in Study 1 to read “someone showed a lack of loyalty to <agents>” and “someone did something to betray their group of <agents>”.

Does any group “rely more” on certain moral foundations?

The most well-known finding from moral foundations research is that, compared to conservatives, liberals rely more on harm and fairness but less on other moral foundations (Reference Graham, Haidt and NosekGraham, Haidt & Nosek, 2009; Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and DittoGraham et al., 2013; Reference Haidt and GrahamHaidt & Graham, 2007). It is therefore remarkable that, due to political double standards, these patterns turned out to be reversed for specific agents. Nonetheless, we think the correct interpretation is that the original finding is in fact quite robust. Given the presence of double standards, we have here been investigating the cases that should produce the greatest possible deviations from people’s overall reliance on moral foundations. Yet, Figure 1 indicates that on the full set of 15 MFQ items, liberal participants often relied substantially more on harm and fairness than their conservative counterparts, but never substantially less. The same held, in the opposite direction, for authority, loyalty, and purity. Thus, rather than contradicting the standard finding, our data indicate that the standard finding would be the typical result for most specifications of agents.

Double standards across countries

By conducting studies in both United States and United Kingdom, we discovered that feelings about the news media and corporations are not inherent to political ideology but specific to countries’ political culture. Namely, in our UK sample the political left and right did not differ much in their feelings about corporations and news media. Consequently, there was little evidence of political double standards in the UK with respect to these agents. In line with our fundamental hypothesis, reliance on obligations for a given agent was still lower among those who had warmer feelings for that agent — but those feelings were evenly distributed across the political spectrum.

Conclusion

In this paper we have proposed that the moral foundations research paradigm can fruitfully be refined by specification of agents in different roles. This allows researchers to assess double standards as well as the robustness of individual differences in reliance on moral foundations. (A similar point was recently made by Voelkel and Brandt, in press.) Our findings indicate that double standards extend beyond moral judgment to the foundations on which those judgments rely. Moreover, they depend on people’s feelings for victims and perpetrators such that people are very concerned about how agents they like are treated but less concerned about how those agents treat others.