1. Introduction

Researchers conducting behavioral studies typically collect data in the laboratory setting. A controlled laboratory environment can promote the reliability of measurements, ensure a lack of distractions, and provide similar conditions for each participant. Experiments conducted in the laboratory setting also allow researchers to control the actions taken by the participants at every stage of the study, which can improve validity and decrease the divergent interpretation of results. However, when it comes to behavioral experiments, especially those conducted on computers, the laboratory setting also has its flaws. For example, individuals are familiar with their own electronic devices, not only at the cognitive level but also at the level of muscle or subconscious memory. Factors such as familiarity with the particular shape of a keyboard, screen size and resolution, and the color palette can influence problem-solving and affect associated measurements, such as reaction times (Manahova, Spaak & de Lange, Reference Manahova, Spaak and de Lange2020).

In recent years, we have observed a sudden rise in accessibility to the Internet worldwide. Today, high-speed Internet is a common utility like running water or electricity, especially for the citizens of large cities in the Western world. This accessibility has allowed researchers to recruit participants via the Internet. Also, the tools available for conducting online behavioral experiments (such as PsychoPy), have allowed for behavioral studies to be conducted completely online, minimizing the limitations of this practice and maximizing profits. In particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic online platforms allowed researchers to continue the research projects they were working on (Scerrati et al., Reference Scerrati, Marzola, Villani, Lugli and D’Ascenzo2021). The critical question that we try to answer in the current study is whether the settings in which behavioral experiments are conducted (the in-person laboratory setting vs. the online setting) influence the results of well-known and frequently used experimental procedures (the emotional Stroop task in this case).

Some studies have already addressed this topic, outlining the pros and cons of research conducted online, and, more importantly, the limitations and challenges of online research (Garcia et al., 2022; Arechar et al., Reference Arechar, Gächter and Molleman2018; Peer et al., Reference Peer, Rothschild, Gordon, Evernden and Damer2022). Others have directly compared the results obtained in online vs. offline settings using the public goods dilemma, an experimental procedure examining the conflict between maximizing one’s own benefit or working for the profit of the whole group (Arechar et al., Reference Arechar, Gächter and Molleman2018). In this case, the results did not yield significant differences between the laboratory and online settings. A lack of significant differences between these two settings has also been reported in other studies (Buso et al., Reference Buso, Di Cagno, Ferrari, Larocca, Lore, Marazzi, Panaccione and Spadoni2021). However, some reports have suggested that the subjective experience of participants may differ in the online and offline settings (Schmelz & Ziegelmeyer, Reference Schmelz and Ziegelmeyer2020). Thus, it seems especially important to examine the differences in results produced when using a very subtle method of experimental manipulation in online vs. offline settings. Therefore, in the current study, we compared the results from presenting single words differing in their emotional loads on the dimensions of valence, arousal, and subjective significance on the emotional Stroop task (EST) in the laboratory and online settings.

1.1. Emotional factors in verbal stimuli

One of the most fundamental emotional dimensions is valence (Russell, Reference Russell1980), which is usually measured on a single bipolar scale with two constructs at the ends (i.e., positive and negative) and the neutral state exactly in the middle (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985; Russell & Barrett, Reference Russell and Barrett1999). Valence is an evolutionary based and simple emotional feature, as it is crucial for us to rapidly assess stimuli and decide whether they are negative (i.e., whether we should treat them as a warning and take into consideration that something unpleasant might happen) or positive (desirable, pleasant, and approachable) (Norris et al., Reference Norris, Gollan, Berntson and Cacioppo2010; Russell, Reference Russell1980). Therefore, it is not surprising that valence has a diffusive and significant influence on our functioning (Freddi et al., Reference Freddi, Tessier, Lacrampe and Dru2014; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Pastwa, Jankowska, Kosman, Modzelewska and Wielgopolan2020; Pêcher et al., Reference Pêcher, Lemercier and Cellier2009).

A second evolutionarily based and elementary dimension that has a significant impact on our functioning is arousal (Russell, Reference Russell1980; Russell, Reference Russell2003; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Wiese, Vaidya, Tellegen and David1999), defined as the amount of energy resources required to take up an action (Mehrabian, Reference Mehrabian1996; Russell, Reference Russell2003; Schimmack & Rainer, Reference Schimmack and Rainer2002). In Russell’s (Reference Russell2003) theory, arousal is conceptualized as a single unipolar dimension, ranging from low (sleep) to high (excitement). In addition, it is described as an automatic (coming from the experiential mind; (Epstein, Reference Epstein2003), physical, innate kind of activation (Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017, usually an immediate response to simple external stimuli. Therefore, most of our reactions caused by heightened arousal are fast and effortless but they are also simplified and even reflexive(e.g., jumping from fear after hearing some loud noise). Furthermore, arousal – often paired with valence in many two- or three-dimensional structural theories – has been shown to have a strong U-shaped relationship with this dimension (Imbir, Reference Imbir2016a), sometimes this relation was reported to be V-shape (Kuppens et al., Reference Kuppens, Tuerlinckx, Russell and Barrett2013). Furthermore, whilst the general relationship was replicated in studies, it could depend on individual differences (personality traits and cultural background; Kuppens et al., Reference Kuppens, Tuerlinckx, Russell and Barrett2013).

Recently, a novel theory was proposed to answer a long-standing debate on the heterogeneous nature of activation. In particular, it seemed that not all activation could be explained by automatic arousal (Schimmack & Rainer, Reference Schimmack and Rainer2002) and that its structure may be more nuanced than was previously assumed. Therefore, based on dual-process theories, a second type of activation was proposed (one “of the rational mind”; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017, namely subjective significance (Imbir, Reference Imbir2016a; Kissler et al., Reference Kissler, Herbert, Peyk and Junghofer2007; van Hooff et al., Reference van Hooff, Dietz, Sharma and Bowman2008). Contrary to arousal, subjective significance is thoughtful and effortful, with conscious energy directed towards some action. Subjective significance requires a decision to start doing something, which is usually made based on previous knowledge, experience, and in line with some rules or goals. Subjective significance is a measure of the reflective importance of a stimulus and is associated with how much action we tend to put toward it.

All of the outlined dimensions can be successfully perceived in many stimuli and thus can be used in psychological research. Recently, words have become one of the most commonly used stimuli used in such studies (Wierzba et al., Reference Wierzba, Riegel, Pucz, Leśniewska, Dragan, Gola, Jednoróg and Marchewka2015a). These stimuli have the advantages of being abstract, easy to manipulate (e.g., preparing a list of words with different valences but the same number of letters), and fast to encode by the participants. However, words may differ in their emotional load; for example, emotional words are faster processed than neutral words (Kousta et al., Reference Kousta, Vinson and Vigliocco2009); furthermore, depending on their different characteristics, they may either disrupt or facilitate cognitive functioning (Ashley & Swick, Reference Ashley and Swick2009; Citron, Reference Citron2012) and elicit different management of visual attention (Wielgopolan & Imbir, Reference Wielgopolan and Imbir2023). Therefore, the need for reliable and meticulously validated has resulted in the creation of several different databases, generating affective norms for words (Bradley & Lang, Reference Bradley and Lang1999; Imbir, Reference Imbir2015; Monnier & Syssau, Reference Monnier and Syssau2014; Montefinese et al., Reference Montefinese, Ambrosini, Fairfield and Mammarella2014; Riegel et al., Reference Riegel, Wierzba, Wypych, Żurawski, Jednoróg, Grabowska and Marchewka2015; Wielgopolan & Imbir, Reference Wielgopolan and Imbir2022; Wierzba et al., Reference Wierzba, Riegel, Pucz, Leśniewska, Dragan, Gola, Jednoróg and Marchewka2015a). Affective norms were created also in non-Indo-European languages – Indonesian (an Austronesian language; Sianipar et al., Reference Sianipar, Ikrar and Yuniarti2016), Chinese (Sino-Tibetan; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Wang, Zhang and Zhuang2017), Turkish (Turkic; Kapucu et al., Reference Kapucu, Kılıç and Metin2021), and Finnish (Uralic; Eilola & Havelka, Reference Eilola and Havelka2010). As it turns out, it is entirely possible to calculate the mean assessment of an emotional feature of a word and separate words based on these features (Bradley & Lang, Reference Bradley and Lang1999). This has allowed researchers to create reliable, validated sets of word stimuli with meticulously studied properties. This type of separation is also possible for the complex dimension of subjective significance (Imbir, Reference Imbir2016a; Wielgopolan & Imbir, Reference Wielgopolan and Imbir2022), as some words are culturally perceived as more or less subjectively significant.

In addition to perceiving the emotional load of a word (e.g., whether they are positive or negative), we are also influenced by this characteristic. For example, the presentation of single words can significantly change the warmth and competence assessments of ambiguous stimuli (Imbir & Pastwa, Reference Imbir and Pastwa2021), and can influence a consumer’s decisions (Imbir, Reference Imbir2018). As single words are stimuli that can easily be inserted into a number of research procedures, they have often been used in cognitive tasks, such as the lexical decision task, the Go-No-Go task, and the EST.

1.2. Emotional Stroop task

The EST allows for the testing of inhibitory control. In this task, as in the classic Stroop task (Stroop, Reference Stroop1935), participants are asked to name the font color of a presented word. In the original Stroop Task, the words presented are the names of colors whose font color matches or does not match the meaning of the word shown; as it measures the cognitive control and modifying the reaction (inhibiting the automatic reaction to read the word of the color). A slowdown was observed in the trials in which the meaning of the word did not match the color (Stroop, Reference Stroop1935). In the EST, the font color also varies from word to word, but the meanings of the words may differ in terms of their emotional load. For example, some are emotionally neutral, while others have emotional loads that evoke different levels of arousal, valence (Russell, Reference Russell2003), or subjective significance (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021). The emotional charge of a word has been found to influence reaction times i.e., negative words usually slowed down the reaction times in comparison to neutral stimuli (Frings et al., Reference Frings, Englert, Wentura and Bermeitinger2010). This effect is due to the interference phenomenon that occurs when a task involves two conflicting processes: automatic and controlled (Nigg, Reference Nigg2000). In the context of the EST, the automatic process is reading an emotionally charged word. This automatic response is learned during childhood and requires no control or effort. The controlled process, upon which success in the task depends, is the untrained, attention-demanding activity of naming the font color of the presented word.

1.3. Aims and hypotheses

The principal aim of the current study is to compare and contrast the results of experiments conducted using different data collection methods, specifically focusing on how different emotional states influence reaction times in the EST. To this end, we compared data collected in the traditional way (i.e., offline in a laboratory setting; Experiment 1) with that collected online (i.e., in a home setting with videoconferencing; Experiment 2). Both experiments were conducted in Polish. We employed the well-known EST but asked current research questions concerning how the dimensions of affect influence performance on this task. We expected as it was obtained in some other studies that compared both methods of conducting experiments (Buso et al., Reference Buso, Di Cagno, Ferrari, Larocca, Lore, Marazzi, Panaccione and Spadoni2021; McGraw et al., Reference McGraw, Tew and Williams2000) to find comparable effects using both types of data collection. First, we expected to find that increasing arousal levels would result in increased reaction times in the EST task. We also expected to find an interaction effect between the valence and arousal levels of words on reaction times. Finally, we expected that subjective significance would show a pattern of results opposite to that observed for arousal. That is, increasing subjective significance levels would shorten reaction times (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021).

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Participants

To estimate the required sample size for both experiments, we conducted a priori power analyses using G-Power software (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) setting the expected power as .95. We expected the effect sizes to range from ηp2 = .06 to ηp2 = .12 for effects of one factor and from ηp2 = .05 to ηp2 = .28 for two-way interactions, which was estimated based on previous experiments employing a similar paradigm (e.g., Imbir, Reference Imbir2021; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Pastwa, Jankowska, Kosman, Modzelewska and Wielgopolan2020), we also estimated the effect sizes for three-way interactions to be among low to middle values from the range for effects of one and two factors. Taking into consideration the repeated measure design of the study employing 27 groups of stimuli a sample size required to verify the effects would range from 15 participants for the larger effect sizes to 81 for the smaller effect sizes. Following these estimations, we assumed that the sample of 40 participants would be appropriate for the study.

Therefore, for Experiment 1, we recruited 40 volunteers (20 women and 20 men), all aged from 18 to 38 years (M = 23.47, SD = 4.18). All of them were students at Warsaw universities and from various faculties. We ensured that they were all right-handed, native Polish speakers, and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

For Experiment 2, we recruited 61 participants. However, two participants who had an overall accuracy lower than 90% on the EST were excluded. Thus, we ended up with an overall sample of 59 participants (30 women and 29 men) aged between 18 and 30 years (M = 22.11, SD = 2.17). All of these participants met the same inclusion criteria as in Experiment 1. We decided to increase the sample size for Experiment 2 as (1) it was conducted online (so we expected there to be slightly more drop-outs and perhaps a need to exclude more data because of noise), and (2) because, in Experiment 1, we observed a lot of multi-level interactions and a larger sample would allow us to study these in a more precise manner.

Before beginning each of the experiments, we asked the participants to provide their informed consent to participate. We informed them that they may withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason. We also ensured them that the data would be kept anonymous and only analyzed on a group level, and that it would be used for research purposes only. After finishing the study, the participants received a small payment (20 PLN, about $5 USD).

The experimental protocols were approved by the bioethical committee in the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw. IRB Approval number – 14/11/2023/32. The participants’ informed written consent was obtained. All of the procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

2.2. Design

In both of our experiments, we wanted to examine the reaction times in response to the emotional loads of words. To this end, we employed the same task for all participants (the EST), manipulating three emotional dimensions and controlling for two more. We analyzed the data using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a 2 (method of conducting the study: offline or online) x 3 (valence: positive, neutral, and negative) x 3 (arousal: low, moderate, and high) x 3 (subjective significance: low, moderate, and high) design. The method of conducting the study was a between-subjects variable, while the level of emotional saturation of words was a within-subjects variable. In this way, we obtained 27 groups of words for each method of conducting the study that differed in terms of the intensity of subjective significance, valence, and arousal (see the Materials section). The controlled dimensions were the number of letters and the frequency of usage in the Polish language. For the analyses, we applied the Greenhouse–Geisser correction if the data did not meet the sphericity assumption.

2.3. Linguistic materials

The words used in the study were taken from the Affective Norms for Polish Words Reloaded database (Imbir, Reference Imbir2016a). In the initial study generating this database, the affective charge of words was measured on eight scales, including the factors manipulated in this study. Each word was assessed by at least 50 participants (equal numbers of men and women) using Likert-like scales. The ANPW_R database includes means from the described ratings for each of the eight affective scales.

The lists of words differ between Experiments 1 and 2, the change of words is motivated by the Corrigendum for ANPW_R word base being publicated between experiments (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021). In the Corrigendum the statistics for a few hundred words were corrected, which resulted in the need to change exactly five words in our stimuli lists. Words “show, insult, coma, villa, and forage cap” from Experiment 1 have been switched to “prosperity, chaise, eagle, consequence, and magazine” in Experiment 2.

Based on the values from the ANPW_R, we constructed the lists of word stimuli used in the current study. Words with extreme values on the manipulated scales (valence, arousal, and subjective significance) were chosen in order to create groups of words intensely charged with emotional value, while words with moderate ratings were chosen to create the moderately charged/control groups. This led to a list of words with factors crossed orthogonally in the following design: three levels of valence (negative, neutral, and positive) x three levels of arousal (low, medium, and high) x three levels of subjective significance (low, medium, and high). The number of letters in the words and the frequency of usage in the Polish language (created on the basis of internet texts; Kazojć, Reference Kazojć2011) were controlled across the word groups.

The validity of the word lists was verified using ANOVAs, the results of which are available in S1 Appendix, together with descriptive statistics. For each word group, we observed the main effects for the manipulated variable with the particular factor as a dependent variable (e.g., an effect of valence for the valence ratings), while we did not observe any significant effects when using any other of the manipulated factors as dependent variables (e.g., no significant effect of valence with arousal as a dependent variable). Furthermore, we did not obtain any significant interactions between the factors. We also conducted ANOVA analyses within the levels of the manipulated factors, where, similar to the overall analyses, we observed only the expected effects of one factor on the dimension of the factor (e.g., an effect of valence with valence as the dependent variable, separately for the three levels of arousal), with no effects on other dimensions and no interaction effects.

2.4. Procedure

For Experiment 1, the participants completed the study in a laboratory setting. Before beginning the experiment, they were provided information on the affiliation of the researchers, the overall aim of the study (they were told that the study concerns color recognition and that they must respond as fast as possible), and the general procedure (its estimated length and the separate parts). The experimenter also assured them about the anonymity of the data and the possibility to withdraw at any moment. After obtaining their informed consent, the participants were asked to sit in front of a laptop and start the experiment, which was prepared using E-Prime 2 software. The procedure began with a training session, where the participants could try the task and learn the instructions. They were asked to indicate the color of the word presented on the screen using four keyboard keys: P, C, Z, and N, representing orange (pomarańczowy in Polish), red (czerwony), green (zielony), and blue (niebieski). The training trials started with a fixation cross (displayed for a random time, ranging from 300 to 590 ms). The participants were then shown a single word presented at the center of the screen and had to react by pressing the key corresponding to its color.

The main experimental task was identical to the training session. The participants were required to name the color of randomly presented words from the group of 405 stimuli. Each of the subjects responded to 405 stimuli. Since we used a 3x3x3 research design, we obtained 27 groups of words. Each group contained 15 emotionally charged words. For example, one group contained words with a low level of subjective significance, negative valence, and low level of arousal, while the next group contained a low level of subjective significance, negative valence, and moderate level of arousal, etc. A fixation cross was always displayed between each word presentation (identical to the training sessions). There was no time limit to respond to the stimuli. When the procedure was finished, the participants were thanked for their participation. If they had any questions, they could ask the experimenter at that time. The whole procedure took about 40 minutes on average.

For Experiment 2, we used the Gorilla platform to implement the experimental procedure. As this experiment was conducted online, we made sure to recreate the laboratory conditions as closely as possible. We invited the participants to an online meeting (using either Google Meet or Zoom platforms) and asked them to keep their cameras and microphones turned on for the whole duration of the experiment. This allowed the participants to be able to freely ask the experimenter questions and the experimenter to monitor the conditions of the experimental session. The information given to the participants was identical to that presented in Experiment 1. The experimenter then sent the link for the Gorilla experiment and asked the participants to click on it. The general experimental procedure was exactly the same as in Experiment 1, including the training sessions and the main EST task. When the participants finished the experiment on the Gorilla platform, they returned to the open tab with the meeting and could ask the experimenter any questions or hear more about the detailed aims and the predictions for the study. They were then thanked for taking part in the experiment, and the meeting was ended. This procedure took about 40 minutes as well.

3. Results

We analyzed the data from both experiments using the same procedure. To prepare the data for analysis, we excluded trials in which participants gave incorrect answers. For the first experiment (offline), 843 trials were removed (5.2% of the total), and in the second experiment (online), 609 trials were removed (2.5% of the total). Next, we removed trials where the participant reacted slower than three standard deviations from their mean latency (207 trials, 1.3% of the total for Experiment 1 and 406 trials, 1.7% of the total for Experiment 2). We also removed trials shorter than 300 ms (149 trials, 0.9% of the total for Experiment 1 and 119 trials, 0.5% of the total for Experiment 2), as responses below this time were too fast to make an informed decision. For both experiments, we converted the reaction times to natural logarithms.

After the data from both studies were prepared, we combined the databases. This allowed us to test the hypothesis whether there were or not differences between the lab- and web-based experiments. On the combined data, we conducted four-way mixed ANOVA (2 methods of conducting the study x 3 levels of valence x 3 levels of arousal x 3 levels of subjective significance) with the study method (online vs. offline) as a between-subjects factor. The results of three-way ANOVA in a repeated measures design, conducted separately for each experiment, are available in the S2 Appendix. The analysis was performed using SPSS v. 28. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction for violations of sphericity was used when necessary. All post hoc tests were Bonferroni corrected.

The overall analysis showed a statistically significant main effect for arousal, F(2, 194) = 9.46; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.09. The participants responded slower to highly arousing stimuli (natural logarithm: LN = 6.71, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 910 ms, SEM = 25 ms) compared to low arousal (LN = 6.68, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 878 ms, SEM = 22 ms), t(98) = 4.62, p < .001, d = 0.46, and moderately arousing stimuli (LN = 6.69, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 886 ms, SEM = 23 ms), t(98) = 3.10, p = .02, d = 0.31. We also observed a statistically significant main effect for valence, F(2, 194) = 3.20; p = .043; ηp2 = 0.03. The reaction times for negative stimuli (LN = 6.69, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 885 ms, SEM = 24 ms) were shorter than for neutral stimuli (LN = 6.70, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 900 ms, SEM = 23 ms), t(98) = 2.81, p = .008, d = 0.28. The mean response times for the combined experiments and for each of them separately can be found in Table 1. A significant main effect for the type experimental setting was not observed, F(1, 97) = 0.46; p = .502; ηp2 = 0.01, nor was a main effect for subjective significance, F(2, 194) = 0.89; p = .412; ηp2 = 0.01.

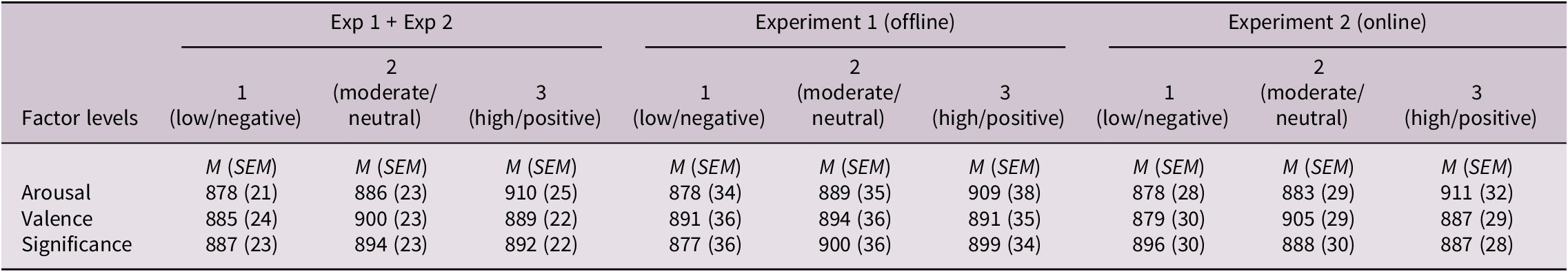

Table 1. Means and standard errors of mean for main effects of valence and origin combined for both studies and for each separately

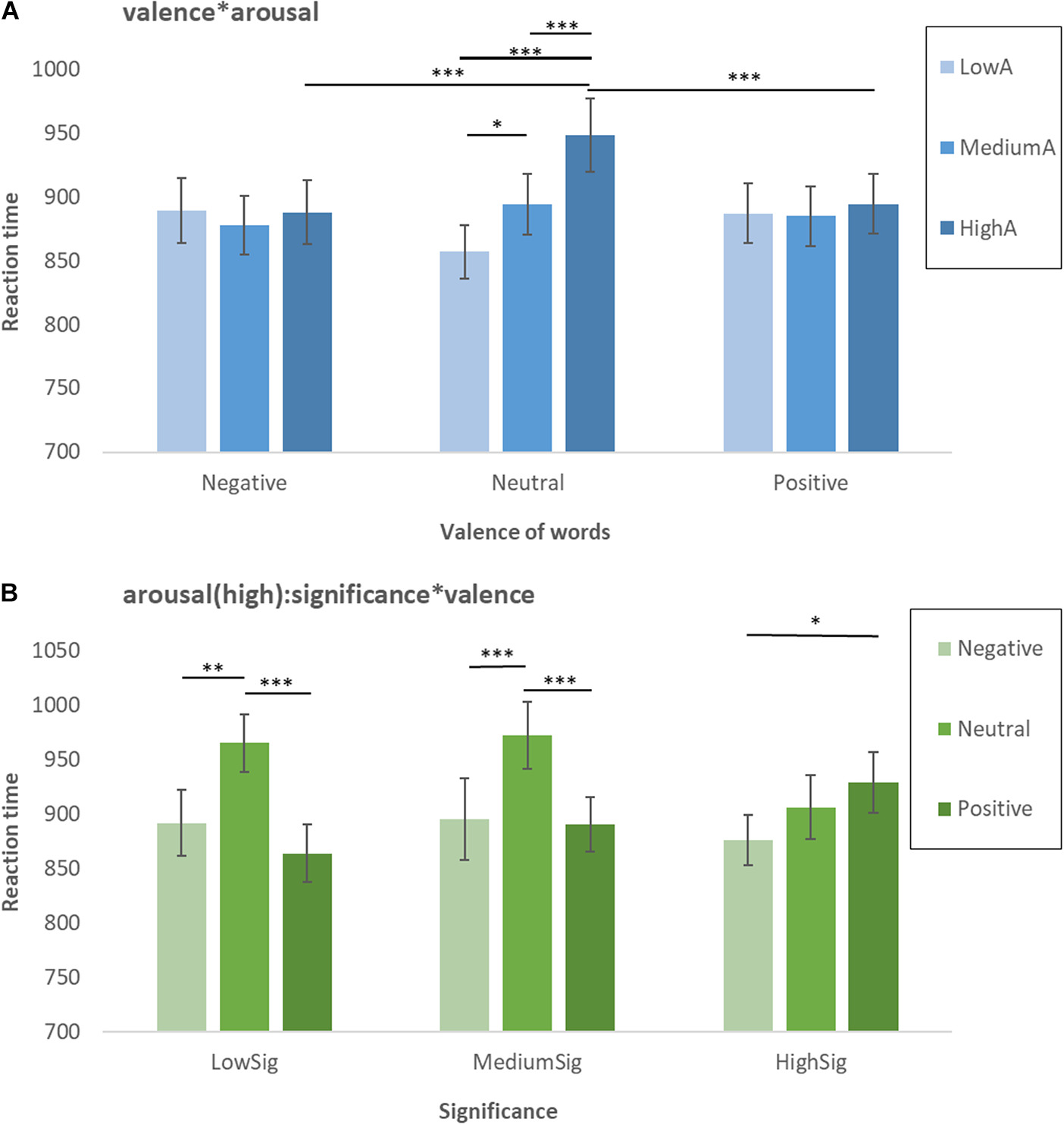

We obtained a statistically significant interaction between valence and arousal, F(4, 388) = 8.14; p < .001; ηp2 = 0.08. Post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction were carried out to acquire details of the interaction. As Figure 1 shows, for highly arousing stimuli, the participants responded slower to emotionally neutral stimuli (LN = 6.75, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 894 ms, SEM = 24 ms) than to negative stimuli (LN = 6.69, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 888 ms, SEM = 25 ms), t(98) = 5.00, p < .001, d = 0.50, and slower to emotionally neutral than to positive stimuli (LN = 6.70, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 895 ms, SEM = 24 ms), t(98) = 4.32, p < .001, d = 0.43.

Figure 1. The interaction between (A) valence and arousal, and (B) valence and significance for a high level of arousal only. The bars represent the mean response time in milliseconds, the error bars show the standard error of the mean, the black horizontal lines indicate significantly different means, and the asterisks indicate the level of significance. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. Lightest colors represent the lowest levels of dimensions, while darker colors indicate the highest levels.

For emotionally neutral words, the participants responded faster to low arousal stimuli (LN = 6.67, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 857 ms, SEM = 21 ms) than to moderately arousing (LN = 6.70, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 894 ms, SEM = 24 ms), t(98) = 2.87, p = .01, d = 0.29, and faster to low arousal stimuli than to highly arousing stimuli (LN = 6.75, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 948 ms, SEM = 29 ms), t(98) = 6.18, p < .001, d = 0.62. For emotionally neutral words, there was also a difference between highly arousing and moderately arousing stimuli. The participants responded faster to moderately arousing stimuli compared to highly arousing ones, t(98) = 4.19, p < .001, d = 0.42.

We did not find statistically significant differences in response times in analyses where the method of conducting the study was one of the factors. No significant interaction effect was noted for valence and the type of data collection, F(2, 194) = 1.12; p = .328; ηp2 = 0.01, or for arousal and the type of data collection F(2, 194) = 0.48; p = .620; ηp2 = 0.01. However, there was a significant interaction effect for subjective significance, and the method of conducting the study F(2, 194) = 4.27; p = .015; ηp2 = 0.04, but post hoc tests with the Bonferroni correction were not significant. There were no differences between methods of conducting experiments for stimuli with low significance (p = .242), moderate significance (p = .690), or high significance (p = .680). Non-significant interaction effects were also noted for the three- and four-way interactions, namely for valence, arousal, and type of study: F(4, 388) = 0.96; p = .427; ηp2 = 0.01; valence, significance, and type of study, F(4, 388) = 0.88; p = .477; ηp2 = 0.01; arousal, significance, and type of study, F(4, 388) = 0.82; p = .516; ηp2 = 0.01, and valence, arousal, significance, and type of study F(6.851, 664.528) = 1.29; p = .247; ηp2 = 0.01.

There was a significant three-way interaction between valence, arousal, and subjective significance, F(6.851, 664.528) = 3.60; p < .001; ηp2 = 0.04. As can be seen in Figure 1, for stimuli of high arousal and low significance, the participants responded faster to negative stimuli (LN = 6.69, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 892 ms, SEM = 30 ms) than to emotionally neutral stimuli (LN = 6.76, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 966 ms, SEM = 38 ms), t(98) = 3.76, p = .003, d = 0.38. The participants also reacted faster to neutral words (LN = 6.76, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 966 ms, SEM = 38 ms) compared to positive words (LN = 6.67, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 864 ms, SEM = 23 ms), t(98) = 3.95, p < .001, d = 0.40. In addition, for highly arousing and moderately significant stimuli, the participants responded faster to negative words (LN = 6.69, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 895 ms, SEM = 26 ms) than to neutral words (LN = 6.78, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 973 ms, SEM = 31 ms), t(98) = 4.37, p < .001, d = 0.44. For the group of highly arousing and highly significant stimuli, the participants reacted faster to negative stimuli (LN = 6.68, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 876 ms, SEM = 27 ms) than to positive ones (LN = 6.73, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 929 ms, SEM = 28 ms), t(98) = 2.01, p = .049, d = 0.20.

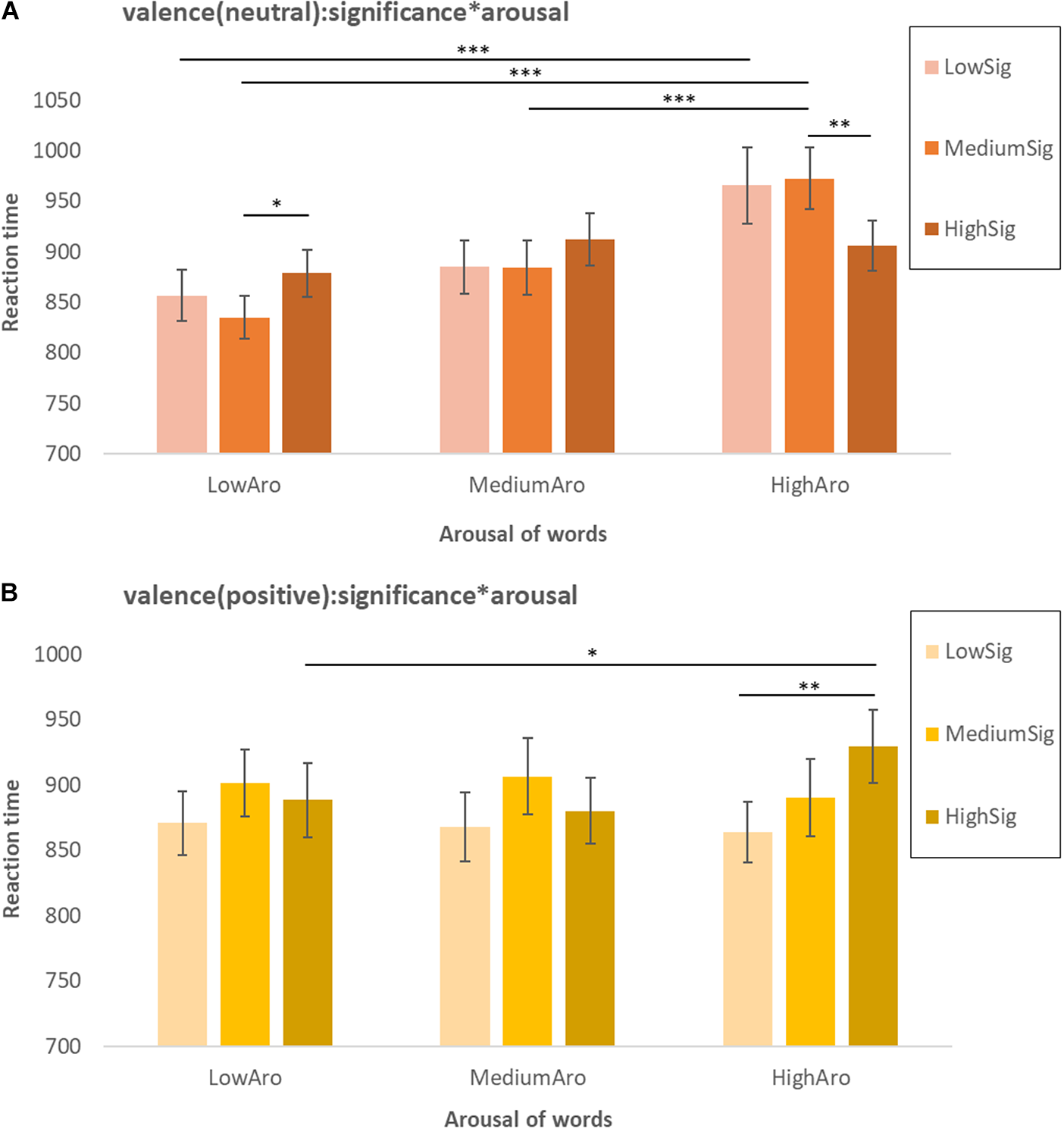

For the group of low arousal and moderately significant words, the participants reacted faster to emotionally neutral stimuli (LN = 6.64, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 835 ms, SEM = 21 ms) than to positive ones (LN = 6.71, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 901 ms, SEM = 25 ms), t(98) = 3.13, p = .005, d = 0.31. Figure 2 shows the interaction between subjective significance and arousal for emotionally neutral words. For emotionally neutral and low significance stimuli, the participants responded faster to low arousal stimuli (LN = 6.62, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 857 ms, SEM = 25 ms) than to high arousal stimuli (LN = 6.76, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 966 ms, SEM = 38 ms), t(98) = 5.07, p < .001, d = 0.51. A similar pattern of results was observed for emotionally neutral and moderately significant stimuli. For this group, the participants responded slower to high arousal stimuli (LN = 6.78, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 973 ms, SEM = 31 ms) than to low arousal stimuli (LN = 6.62, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 835 ms, SEM = 21 ms), t(98) = 6.13, p < .001, d = 0.62 and moderate arousal stimuli (LN = 6.68, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 884 ms, SEM = 27 ms), t(98) = 2.24, p < .001, d = 0.23. In the group of emotionally neutral and low arousal words, the participants reacted faster to moderately significant stimuli (LN = 6.64, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 835 ms, SEM = 21 ms) compared to highly significant stimuli (LN = 6.71, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 879 ms, SEM = 23 ms), t(98) = 2.82, p = .024, d = 0.28. In addition, for highly arousing and emotionally neutral words, the participants responded faster to highly significant stimuli (LN = 6.71, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 906 ms, SEM = 25 ms) than to moderately significant stimuli (LN = 6.78, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 973 ms, SEM = 30 ms), t(98) = 3.31, p = .006, d = 0.33 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The interaction between significance and arousal for (A) neutral level of valence, and (B) positive valence. The bars represent the mean response time in milliseconds, the error bars show the standard error of the mean, the black horizontal lines indicate significantly different means, and the asterisks indicate the level of significance.***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

As can be seen in Figure 2, for positive and highly significant stimuli, the participants reacted faster to low arousal stimuli (LN = 6.68, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 888 ms, SEM = 28 ms) compared to high arousal stimuli (LN = 6.73, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 929 ms, SEM = 28 ms), t(98) = 2.14, p = .044, d = 0.21. Also, for positive and highly arousing stimuli, they responded faster to low-significance stimuli (LN = 6.67, SEMLN = 0.02; M = 864 ms, SEM = 23 ms) than to highly significant stimuli (LN = 6.73, SEMLN = 0.03; M = 929 ms, SEM = 28 ms), t(98) = 2.45, p = .009, d = 0.25. We conducted a post hoc power analysis in order to verify the actual power achieved by each of the results observed on the whole sample (Exp 1 + Exp 2). The analyses showed that the main effect of arousal, the interaction between arousal and valence, as well as the three-way interaction, achieved a very high power of .99, while the main effect of valence achieved a high statistical power of .91.

4. Discussion

As expected, we observed no differences between the two experiments that collected data either offline or online. None of the comparisons were significant, which is in line with previous studies (Buso et al., Reference Buso, Di Cagno, Ferrari, Larocca, Lore, Marazzi, Panaccione and Spadoni2021; García et al., Reference García, Di Paolo and De Jaegher2022). The overall effects obtained in the two experiments were rather similar (the interactions between valence and arousal, as well as three-way interactions between the valence, arousal, and subjective significance). These data further show that, even for studies with a very subtle manipulation (not eliciting any strong emotional states but rather presenting stimuli only), it is possible to conduct them online and obtain reliable results (i.e., they are not significantly different from the results collected in a laboratory setting). Nevertheless, it is important to stress the fact that, when conducting the online study, we followed a very precise protocol (see the Methods section) and employed methods (an online platform to run experiments online and videoconferencing via other tools) that enabled continuous contact with the participants during the whole duration of the experiment.

The results obtained by our team are consistent with those obtained by other researchers examining whether results from online studies are similar to those from in-person studies (Arechar et al., Reference Arechar, Gächter and Molleman2018; García et al., Reference García, Di Paolo and De Jaegher2022; Peer et al., Reference Peer, Rothschild, Gordon, Evernden and Damer2022). However, it is worth noting that the cited studies pertain to entirely different research methods, such as qualitative comparisons of impressions from psychotherapy or decision-making in economic games. In our experiments, by contrast, the measure was reaction times to words with varying levels of emotional intensity, expressed in milliseconds, similar to some crowdsourcing projects in which we could see that the correlations between the laboratory and online-based studies are high (over r = .70; Brysbaert et al., Reference Brysbaert, Mandera, McCormick and Keuleers2019; Mandera et al., Reference Mandera, Keuleers and Brysbaert2020). The fact that consistent results were achieved in both online and in-person experiments with multifactorial analyses serves as a strong argument supporting the reliability of sensitive online measurements as well. An additional element confirming the quality of online measurements—at least in the field of affective behavioral research—is the consistency of the findings in this study with previous research we conducted on emotional factors in verbal stimuli.

In line with our predictions and with previous studies, we observed a significant main effect for arousal. As found in earlier studies, it was a disruptive factor for cognitive control (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017) capturing the attention of the participants, making it more difficult to stop an automatic response and choose a more deliberative one, and, consequently, slowing the reaction times. However, we observed this pattern for the online experiment only (Experiment 2). In the offline experiment (Experiment 1), there were some similar comparisons in the interactions with valence (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021), and with valence and subjective significance. One of the possible reasons for this may be the fact that, when participating in an online study, the participants are in familiar surroundings (i.e., usually at home with no stress caused by the unfamiliar laboratory situation). It may be that this setting allowed them to fully perceive the dimensions in the emotional load of the words, reacting to even very small changes in elicited arousal. When taking part in the study conducted in a laboratory, participants could be stressed by coming to an unfamiliar place and participating in a rigorously structured situation, which may tone down the emotional response to small differences in arousing value of stimuli.

The finding that the participants reacted faster to negative stimuli than to neutral stimuli is more fully explained by the interaction between valence and arousal. Negative stimuli, as they can be threatening, should attract our attention more quickly, but also hold it longer, which could result in a longer reaction time (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Mathews and MacLeod1996; McKenna & Sharma, Reference McKenna and Sharma2004). However, the results of the current study and of those of Imbir (Reference Imbir2021) show, that the reaction times to negative stimuli are shorter compared to neutral stimuli, but only for highly arousing stimuli, and not for low arousal or moderately arousing stimuli. It may be that the participant’s attention is captured faster by negative words, but due to high arousal, this attention is not maintained on the negative stimuli, allowing them to focus back on naming the colors of the words, thus resulting in a faster response time. In other words, high arousal could take the attention away quicker from the negative words, which might prevent negative stimuli from capturing attention for longer.

We did not obtain significant results for subjective significance (other than in the three-way interactions from Appendix S2), which we had expected based on previous studies (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017). In most cases, this effect was close to the level of significance, but either did not meet it, or the correction within the pairwise comparisons made the differences insignificant. This result was consistent in both of the experiments. Thus, it seems that while subjective significance may modify the results of valence and arousal (in the interaction with these two dimensions), it does not modify the reaction times in the EST by itself contrary to previous studies (Imbir, Reference Imbir2018). This effect, however, has been observed previously in a similar experiment (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021), in which subjective significance came into the interactions only. Therefore, the effects of subjective significance itself may be suppressed when it is paired in an experimental design with much more fundamental, evolutionary, and automatic dimensions (i.e., valence and arousal). Future studies are needed to verify the effects of subjective significance on its own (or paired with arousal only, but with valence as a controlled variable (Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017 to give us a clearer picture.

It is also worth noting that high arousal itself slows reaction times. However, the narrative outlined above that high arousal speeds up responses to emotional stimuli is supported by the observed interaction indicating that, only for emotionally neutral words, there were faster responses to low arousal stimuli compared to highly arousing stimuli. An almost identical pattern of results was reported by Imbir (Reference Imbir2021), which raises doubts as to whether these results are an artifact. In this case, emotionally neutral words do not capture attention faster than emotionally negative stimuli, and high arousal, instead of helping to take attention away from negative stimuli, makes it difficult to focus on the task. Consequently, these factors result in a slower response time.

One of the limitations of the current study is the homogeneity of our sample. We studied only young adults enrolled in Polish universities. Thus, this group of individuals were very similar to each other in their cognitive abilities and general reaction times. While this is a reason not to generalize our results to other age groups (e.g., because of the differences in reaction times appearing with age; (Deary & Der, Reference Deary and Der2005), it was crucial for our experiments to recruit such a sample. The database from which we derived the word lists was assessed by students (Imbir, Reference Imbir2016a) and, therefore, there was a congruency between the previous raters and the current participants. In addition, some assessments (e.g., subjective significance, which may be very much tied to the generational values, aims, and opinions; (Imbir, Reference Imbir2015; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017) may be shared between people of the same age, but not with older participants. It is also worth noting that, despite the lack of significant interactions in the four-way ANOVA, statistically significant differences were found in the three-way ANOVA for subjective significance in the offline experiment (Appendix S2). This result may suggest that there are very subtle differences between different types of experimental setups, which are specific to the given context. It is worth noting, however, that the inclusion of five changed words across experiments can be considered a strength of the current study, as it enhances the generalizability of the findings by demonstrating their consistency despite slight variations in the experimental materials.

It is also important to mention that we studied cognitive control, not only in a very specific task (and mostly its interference facet), but also using very particular stimuli. While there is a need to replicate our results using different stimuli, words are one of the best ways to create comparable conditions in an experiment. We were not only able to easily choose stimuli with different characteristics (i.e., measuring arousal and subjective significance very precisely – this is especially difficult as the nature of these two types of activation is rather different; (Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Spustek, Bernatowicz, Duda-Goławska and Żygierewicz2017, but also to control for other variables, such as the length of words and the frequency of their usage in the Polish language. However, not all variables could have been controlled such as orthographic neighborhood (Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Mercer and Balota2006). While this kind of manipulation may not be perfect (as explained when discussing the valence results), it is the most precise that can be used to obtain an orthogonal design and be able to compare the results from different word groups.

5. Conclusions

Our results further show how experiments (even behavioral ones analyzing the reaction times) may be conducted using different methods. The results indicate that the data obtained from the online experiment were not significantly different than those obtained from the offline one. Furthermore, in both experiments, we replicated effects observed in previous studies using linguistic materials and the EST paradigm (Imbir, Reference Imbir2021; Imbir et al., Reference Imbir, Pastwa, Jankowska, Kosman, Modzelewska and Wielgopolan2020). Nevertheless, there were some specific effects (e.g., the arousal effect in the online study only) that should be further investigated in future studies (e.g., using the eye-tracking method to examine managing visual attention while completing the study in the laboratory vs. at home). As we have already mentioned in the discussion of limitations, the obtained effects could also be examined using a different task engaging cognitive control (e.g., the Go-No-Go task) or other types of stimuli.

The current results provide a rationale for further developing and improving the protocols for online studies, as this method seems reliable. As we argue above, online data collection has many benefits (e.g., recruiting participants from across the country rather than from one university, as often happens with laboratory studies) that should not be overlooked. Online studies may also improve the overall inclusiveness of data (e.g., regarding samples that are difficult to reach) and open the possibility of collecting data on a larger scale (e.g., increasing the sample sizes).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2024.77.

Data availability statement

The datasets from both of our experiments are publicly available in Figure share repository: https://Figureshare.com/s/58a2959e4039a826e943. The experiment was not preregistered.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marcin Giermaniuk for help in gathering the data.

Competing interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethics statement

The study received a positive opinion granted by the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw.