Introduction

Foundational sociolinguistic studies in African American (Vernacular) English (AA(V)E) have focused on collecting data from a social group that is urban, working-class, and predominately male (Labov, Cohens, Robins, & Lewis Reference Labov, Cohen, Robins and Lewis1968; Fasold Reference Fasold1972). Scholars have criticized defining the variety based only on the speech of this subset of the Black population, which contributes to stereotypical representations that create a monolithic portrait of Blackness (Smitherman Reference Smitherman, Smitherman-Donaldson and van Dijk1988; Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2003; Wassink & Curzan Reference Wassink and Curzan2004). While such a critique has been well-established in the literature, an additional oversight or gap in our study of inner-city, male youth is the lack of attention to the social and language practices of these speakers outside of their reproduction of AA(V)E and how such practices are part of a broader semiotic construction of identity. In addition to researching the most stigmatized features of the ethnic variety, we can also research stylistic variation amongst Black speakers, observing both the linguistic and nonlinguistic resources used in the construction of racialized urban personae to understand what language contributes to such styles through this process of bricolage (Hebdige Reference Hebdige1979).

Drawing on ethnographic observations and sociolinguistic interviews with African American speakers who were born and raised in Rochester, New York, I investigate how the bought vowel in New York City English variety has been reanalyzed in the construction of Rochester's Hood Kid persona and discuss its indexical potential as a marker of a particular place-identity in both Rochester and New York City, the most well-known and populated city in the state. I argue that the Hood Kid persona is embedded in a recursive racialized and classed network that includes the suburban-city contrast, as well as the embedded Hood-versus-non-Hood opposition within the city limits. In addition to the clothing and lexical features, the Hood Kid's reanalysis of boughtFootnote 1 represents an adequation of an enregistered (Agha Reference Agha2007) tough, aloof New York City persona, which has been reported amongst Black New Yorkers (Becker Reference Becker2014a). Such variation suggests that speakers’ conceptualization of race and place ideologically scales beyond immediately local geographic boundaries, while its study expands documentation of Black speech.

Background

Place and language in AAL

AA(V)E, or in its most recent designation, African American Language (AAL; Lanehart Reference Lanehart2015), is one of the most well-studied dialects in sociolinguistics. While earlier research focused on the shared canonical features of the variety, more recent research has begun to prioritize the study of regional variation (Kendall & Farrington Reference Kendall and Farrington2020), with cross-regional comparisons of various AA(V)E features or vocalic systems (Wolfram Reference Wolfram2007; Farrington, King, & Kohn Reference Farrington, King and Kohn2021). The designation, African American Language, more broadly reflects and embraces all African Americans’ linguistic behavior, beyond those associated with the most canonical patterns, hence the use of AAL hereafter (Lanehart Reference Lanehart2015; King Reference King2020). Complicating what it means to sound Black, such investigations reveal that there are multiple ways in which African Americans are enacting Blackness, alongside other dimensions of identity. The move toward viewing speakers’ identities as more multidimensional has advanced the field by diversifying representations of Blackness and exploring how linguistic practices are informed by intersectionality, the co-occurrence of multiple oppressions (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989), and co-constitution of multiple identities (Levon Reference Levon2015; King Reference King2021).

Broader cross-regional studies have compared linguistic patterns of African Americans from different cities, acknowledging how particular social processes such as migration, segregation, and gentrification have affected the observed variation. Such investigations raise questions about how these broader sociohistorical changes affect intra-community variation and speakers’ own construction of place identity. Work on African Americans in Washington, DC revealed that varying stances on place-based issues like gentrification can affect the production of linguistic patterns associated with AA(V)E (Grieser Reference Grieser2015; Podesva Reference Podesva, Samy Alim, Ball and Rickford2016). Importantly, in considering place identity, these analyses do not take for granted that speakers can simultaneously construct other dimensions of identity like gender and/or class. These analyses have focused on the patterns that may be associated with AA(V)E, like consonant cluster deletion, but there is a dearth of research assessing how regionalized features, outside of those associated with the African American Vowel System (Thomas Reference Thomas2007) become sites for observing the co-construction of place, race, and class identity. Work by Mallinson & Childs (Reference Mallinson and Childs2007) is one exception as their work on two communities of practice (the porch-sitters vs. the church ladies) revealed two different constructions of locality in a rural Appalachian community. The women in this study not only exhibited differences in productions of the local sound changes across groups, but also held different ideologies and practices related to Black femininity in that space and time. This work suggests that investigations of regional phonetic variation may be useful to understanding both the stability and variability of the linguistic behaviors we observe across African American communities.

Conceptualizing difference

Research in dialectological literature has emphasized the importance of complicating place identity and attending to multiple performances of such within a given region. These variationist studies have operationalized differences in place identity by attending to local social divisions including neighborhood affiliation (D'Onofrio & Benheim Reference D'Onofrio and Benheim2020; Benheim & D'Onofrio Reference Benheim and D'Onofrio2023), intracommunal ideological distinctions (e.g. town vs. country; Podesva, D'Onofrio, Van Hofwegen, & Kim Reference Podesva, D'Onofrio, Van Hofwegen and Kim2015), social network analyses (Sharma & Dodsworth Reference Sharma and Dodsworth2020), and customized metrics assessing speakers’ degree of rootedness or multiple aspects of one's alignment with a given place (Reed Reference Reed2020; Carmichael Reference Carmichael2023). These studies reveal that there are multiple means for exploring speakers’ connection to place. However, I prioritize the theoretic model of the persona, or figure of personhood, to explain the regional variation observed amongst Black speakers in this study.

A macrosocial category, such as ‘Californians’, ‘women’, or ‘African American’, is oftentimes the social construct we begin with when exploring group language practices. Yet, macrosocial categories are populated by personae, and they can be an ‘important construct in understanding how on-the-ground interactional practice builds up to form larger-scale patterns of sociolinguistic variation and change’ (D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020:1). Following Agha (Reference Agha2005), D'Onofrio describes the persona as a ‘social construct linked with recognizable registers, or ways of speaking’, and names Los Angeles’ Valley Girl and Pittsburgh's Yinzer (Johnstone, Andrus, & Danielson Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006) as examples of such personae with their own respective varieties like Californian English or Pittsburghese (D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020:2–3). Such a model helps to accomplish three goals in the study of African Americans’ speech. First, as the study of cross-regional variation has revealed the importance of attending to multidimensionality across African American identity, the persona affords us another means through which to expand and/or diversify portrayals of Blackness in sociolinguistic descriptions of Black speech. Second, as we are increasingly interested in the social processes that affect the phonology of Black speakers, it requires that we attend to the sociohistorical events and changes particular to the Black speakers’ communities we study. The persona encapsulates not only the co-construction of identities, but connects speakers to a particular chronotope, or a semiotic representation of time and space peopled by certain social types (Agha Reference Agha2007:321). The connection between the persona and the chronotope relies on ethnographically informed observations and contextualizes the emergence of linguistic variation within the bounds of a community, its history, and its people. Finally, this construct is not only important for connecting individual speakers to specific registers of speech, but it is also part of a broader system of semiosis through which speakers are making meaning (Eckert Reference Eckert2012; Mendoza-Denton Reference Mendoza-Denton2014; Calder Reference Calder2019). Engaging in understanding the cross-modal performance of a persona illuminates the role language and other non-linguistic features play in the construction of racialized identities and how they cluster together in social space.

In addition to using the theoretic model of the persona to explore regional variation in African Americans’ speech, recruiting Bucholtz & Hall's (Reference Bucholtz and Hall2010) theories that view identity as relational can explain how different personae are positioned in relation to one another. The focus on intersubjectivity between different individuals or groups of Black speakers need not be about maximizing difference, even in studies of heterogeneity, for the sake of maintaining distinction. Specifically, sameness and difference can be conceptualized through Bucholtz & Hall's (Reference Bucholtz and Hall2010:24) theory of adequation and distinction such that we can recognize both the similarities aligning specific personae and the dissimilarities distinguishing them and why. As discussed below with the Hood Kids, the basis of this performance relies on an ideological likening to an existing racialized persona already in circulation for New York City, but their linguistic behavior also distinguishes them from the other young African Americans in Rochester who do not identify as Hood. The Hood Kids conform to such a persona as result of an ideologically shared racialized, gendered, class identity, while diverging from the locals with whom they do not share this particular aspect of their class identity. Holding both the variation and sameness constant requires acknowledging how speakers share the same social categories such as age and city of origin, but also contending with the other dimensions in which they diverge. Thus, the goal of fieldwork amongst African Americans in Rochester, New York was to examine the community-specific distinctions relevant to that social landscape and to understand how the adequation of a New York City persona constitutes a project of scale-making amongst participants (Lempert & Carr Reference Lempert, Summerson Carr, Lempert, Summerson and Carr2016).

Such concepts of relationality can also be captured in theories of scale, which Gal (Reference Gal, Lempert and Summerson Carr2016:91) defines as ‘a relational practice that relies on situated comparisons among events, persons, and activities’. This ideological practice can be accomplished through semiotic means. Both theories on scale and adequation elucidate how to understand the relationship between the personae, the Hood Kids (Rochester) and New York Niggas (New York City). Scale captures the ideological social comparison itself between these personae, while adequation accounts for the nature of the comparison and how it is realized, such that the Hood Kid is both an approximation and reinterpretation of a New York persona that allows the Hood Kids to remain recognizable as a kind of New Yorker, but distinguishable from the urban center, New York City itself.

The community

Within Rochester's inner city, there are multiple kinds of urban styles that speakers can enact based on where they live. Salient axes of differentiation (Gal Reference Gal, Lempert and Summerson Carr2016) with respect to location-based distinctions include the suburb vs. city opposition where the suburbs are ideologically racialized and classed as white and privileged, while the inner city is racialized and classed as Black and underserved (King Reference King2021). Further, within the city limits, another fractal (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000) emerges such that the racialized and classed dichotomy reproduces itself in a Hood vs. non-Hood contrast. Specifically, amongst the inner city, which is primarily ideologized as Black, Black participants are distinguished from one another based on whether they identify with growing up in low-income neighborhoods, housing projects, or blighted streets. Within these oppositions, speakers’ understanding of the larger social demographic categories like class, gender, and race are embedded into their conceptions of how space is organized.

The Hood cannot be delocalized from the sociohistorical circumstances in which it developed. Rochester, which at the time of data collection had a Black population of 41%, has a history of being racially hyper-segregated and excluding African Americans from the workforce up until the mid-sixties (McKelvey Reference McKelvey1967; Massey & Tannen Reference Massey and Tannen2015). During the post-industrial economic decline of rust-belt regions, like Rochester, African Americans felt the downturn of the economy with high unemployment and low wages (Wilson Reference Wilson2011). Further, Rochester was even named on a 2023 list of the worst cities for Black Americans because of Black median income ($31,920; 48.2% of white income), unemployment rates (12.5% Black and 3.7% white) and homeownership rates (31.9% Black and 72.9% white) in comparison to white Americans in the area (Suneson Reference Suneson2023).

Behind New York City and Buffalo, Rochester is the third largest city in the state. People have jokingly referred to Rochester as Canada, New York, given its closer geographic proximity to the Canadian border than to New York City. Such an observation reinforces scaling as an ideological project considering the comparison point for Black Rochesterians is not about the proximity or distance from a geographic location more than it is about the perception of a shared experience. Put differently, the legibility of the Hood Kid, in part, depends on the positioning of Rochester's social landscape against the social landscape of New York City, the most recognizable urban center in the state. This persona is rendered through the uptake of variables attached to New York City personae and the variables include linguistic features like local slang, the bought vowel, as well as other stylistic resources like Timberland boots, New York Yankee Fitted Caps, and other kinds of streetwear.

The enregisterment of the Hood Kid and the New York Nigga personae

Enregisterment is the process through which particular dialects or ways of speaking come to be associated with some group of speakers, whether such forms are real or imagined (Agha Reference Agha2005:38). In discussing the emergence of the Hood Kid as a recognizable type in Rochester, I argue that it draws on the New York Nigga, a persona associated with an enregistered racialized style originating from New York City.

As suggested in my discussion of the axes of differentiation, the Hood Kid is a persona connected to a locale that is racialized as Black and such observations are supported by speakers. For example, when ChrisFootnote 2 (age twenty-eight) discusses attending events in the Hood he says, ‘If I go to a party in the Hood, it's just straight Black. Everybody’. Hood derives from both neighborhood and Hoodlum, but the definition assumed in this article refers to a region characterized by a concentration of underserved, working-class, Black communities. In the top three highest-rated definitions on Urban Dictionary, a crowd-sourced means for defining slang, the Hood is viewed as both a kind of space in the inner city such as the ghetto, but also an adjective to describe someone from that space and/or the culture that has emerged from that space. This is consistent with Joseph's (age thirty-two) description of himself:

I just feel like I'm just a regular – regular city Hood Kid. That's it. Like, I mean as far as me – By me saying a Hood Kid, it's just like, you know, I'm a by-any-means-necessary do-what-I-have-to-do to stay where I'm at.

The phrase ‘regular city Hood Kid’ implies that this is a recognizable and familiar urban identity. Joseph's use of the phrase ‘by any means necessary’ is dialectic, drawing on discourses by revolutionaries like Franz Fanon or Malcolm X and their culture of resistance to oppressive conditions. In the context of Joseph's entire interview, I interpret his deployment of such a phrase to express the means he has exploited to survive a blighted neighborhood, such as working up to three jobs. The toughness he needed to develop is not to be confused with intimidation, but is one of resilience in the face of financial insecurity.

Alongside speakers like Joseph, Trey (age twenty-six) uses the term ghetto, which can also be used interchangeably with Hood in both an adjectival and nominal form to discuss his connection to be being born there, while also recognizing that there is a culture that has been cultivated in that space:

I call myself a ghetto kid. I'm a ghetto baby. I ain't gonna say – I'm not gonna ever disclaim the streets. I came from the streets. I came from the ghetto. That's what it is. That's culture.

Trey identifies with the experience of growing up in the ghetto and claims it as a badge of honor. Hood is more than just a place, as denoted in speakers’ excerpts and Urban Dictionary definitions and it represents a specific kind of locality performed through unique sets of practices.

Speakers of the community can explicitly name the semiotic resources used to construct this style. In the following conversation, Joseph and Remy (age thirty-two) two speakers who both identify as Hood, were asked if Hood Kids have a particular style of dress. Both speakers were able to speak to the stylistic practices (Eckert Reference Eckert2012), as well as discuss the origins of these resources.

Joseph: I mean, yeah, White tees, jeans

Remy: – Three times too big!

Joseph: Trying your hardest to get some Timbos, A Fitted – Well, back then we use to wear head bands.

Interviewer: Do you think that kind of style sorta like derived from New York City kind of style?

Remy: I think it's just a New York thing, so yeah.

In this interaction, Joseph mentions that White tees and jeans are characteristic of this style, but Remy interrupts him to emphasize that the jeans are three times too big. This overemphasis refers to the bagginess of the jeans, which are often sagged, or worn below the waist such that the top of one's boxers is sometimes exposed. In addition to these two items, Joseph mentions ‘Timbos,’ which is slang for Timberland boots, and a ‘Fitted,’ which is short for a New Era Fitted Baseball Cap. He notes that there was a time in which Hood Kids wanted to wear headbands more than Fitteds and this reveals how this persona has followed trends happening in streetwear fashion relevant to Hip-Hop culture at a given moment. The style has been fluid with different resources coming into the construction of the Hood Kid, but certain items have always remained in circulation.

The New York Yankee Fitteds and Timberland boots have become emblems of specific urban personae in New York City, such as the New York City Nigga, which largely derives from stereotypes about urban, Black, male New Yorkers, as well as from New York City rappers like Jay Z, Fabolous, or DMX. Fitteds refer to a specific model of the cap called the 59Fifty, and community members are referencing the cap with the New York Yankees logo, rather than another New York team logo. This cap is distinguished from others due to its lack of a Velcro or plastic adjuster.Footnote 3 The connection between Hood culture and this hat, also dubbed the ‘The Brooklyn Style’ cap, has been popularized and circulated via Hip Hop, a global culture that emerged from the streets of New York. Particularly, one of the most prominent New York hip hop artists, Jay-Z, has constructed a rap persona around street culture, emphasizing his business savvy and street-smart skills to hustle his way out of the projects by selling drugs then rapping to climb the socioeconomic ladder. He expresses New York pride wearing the iconic Yankee Fitted cap and in his ode to the city, ‘Empire State of Mind,’ he raps, ‘Catch me at the X wit OG at a Yankees Game. Shit, I made the Yankee hat more famous than a Yankee can’.

Like Fitteds, Timberland boots have also been associated with Hip Hop culture in New York, and, perhaps, Hood culture more broadly. The Original Yellow BootFootnote 4 was a leather, waterproof boot released in 1976 and it was designed for the blue-collar workforce in the New England region. Valued for its ability to withstand the harsh weather conditions, it was adopted into street culture being worn year-round for those involved in organized crime, rather than just worn in the winter (Woolf Reference Woolf2014). Now, the boots are less about weather practicality and selling drugs and index a kind of cool streetwear style that has extended beyond New York. They rose to greater popularity in the nineties via hip hop artists like the Wu-Tang Clan, Biggie, and, again, Jay Z.

As discussed by Remy and Joseph, the stylistic elements of the Hood Kid persona derive from the New York City landscape, but these speakers see them as being available resources for all residents of the state. In the last line of the previous excerpt, Remy's response indicates that these items are viewed as resources available to New York through prosodic prominence of the words ‘New York’ (in bold), contrasting from the interviewer's naming of ‘New York City’. This subtle distinction helps to constitute a scaling project, generalizing across the broader state, rather than just the city. Omitting ‘city’ minimizes the distinction between Rochester and New York City, despite the approximately 300-mile physical distance. This erasure is an example of an observed ideological equation whereby Rochesterians draw on practices and semiotic resources associated with a non-local place identity perhaps because of the indirect indexicalities of The City and/or the covert prestige it provides. Such ideologies underlie the observed linguistic adequation where speakers approximate specific features to adopt a passable New York identity, while avoiding claims of inauthenticity. That is, Rochesterians can genuinely identify as ‘New Yorkers’, without claiming to be from New York City.

In addition to the circulation of this style via Hip Hop music, Hood Kids have acquired this style via visits to the city. For example, Paul discusses how he draws on Black culture in New York City whenever he visits.

I feel like we just instantly pick up uh – especially – especially Black people like – like just that culture there, we just instantly pick up on that – that New York City culture ‘cause I – I mean I been down there for like a week and I come back, you know, sounding like I was from the Bronx.

Alongside the uptake of the culture through visits to New York City, speakers are exposed to the culture via social media platforms like the former Twitter and Instagram, which also serve as sites for ethnographic fieldwork (Bonilla & Rosa Reference Bonilla and Rosa2015). Platforms like these are akin to virtual neighborhoods (Appaduari Reference Appadurai1996), providing a window into the digital co-construction of personae. For example, stereotypes about Black New Yorkers have been propagated via memes and tweets with hashtags like #newyorkersbelike and #newyorkniggas. Note that the hashtags make use of the habitual be found in AA(V)E and the lexical item nigga. In Figure 1, we can observe the construction of a racialized New York identity, which draws on the New York stylistic staples, Fitteds and Timberland Boots. These conceptions of the New York Nigga may be hyperbolic, but it reveals the legibility of this social type across social media.

Figure 1. Urban Dictionary definition of New York Nigga.

In addition to the non-linguistic semiotic resources, my research participants have also named other regionalized lexical items that are associated with Black speakers in New York City including intensifiers like mad & dead-ass as in that's mad corny or I'm dead-ass serious, as well as address terms like son as in What up, son? to address people that are not actual children of the speaker and need not be male. Beyond these Black regional examples, there are also examples of pan-regional AA(V)E patterns in the speech of the Hood Kids including the use of invariant habitual be, done as completive aspectual marker, copula absence, existential it, and negative concord among others, but further analysis of those are beyond the scope of this particular article.

Hood could be an important identity across other inner cities in the United States, but to characterize how it becomes legible in Rochester's social landscape, I have presented how the performance depends on the uptake of semiotic resources from urban, New York City personae and argue that the reanalysis of bought offers an additional site to observe the construction of the Hood Kid persona. It is through bricolage, or the constellation of recombined and reinterpreted linguistic and nonlinguistic variables in innovative ways (Hebdige Reference Hebdige1979; Eckert Reference Eckert2012) that we come to understand the multidimensional construction of this specific racialized locality (King & Calder Reference King and Calder2024).

Gender performance of Hood Kids

Although the description of the Hood Kid has mostly focused on the persona's locality and class, it also tends to be gendered as male. The New York Nigga operates as a young, male-coded persona drawing on the term nigga which tends to reference ‘males of any ethnicity in much the same way as does guy’ (Spears Reference Spears, Mufwene, Bailey, Baugh and Rickford1998:12). Further, the quotes defining hood mostly come from young men in the sample and they are more likely than women to explicitly identify as hood possibly due to gendered expectations of men as strong, tough, and protective and women as soft, meek, or docile. The circulation of this persona partly emerges from a male-dominated genre that glorifies hustle-culture, and the associated quality of toughness is more readily available to men, but not exclusively so. While the Jay-Zs exist, we can also point to female rappers from New York like Lil’ Kim, Remy Ma, and Cardi B as embodiments of subversive female entertainers for their ability to portray similar qualities. However, in this study, fewer women claim such an identity.

Methods

This data was collected by the author, an African American community member born and raised in the inner city of Rochester, New York. The researcher grew up in the millennial generation and attended public school until college, where she went to private universities for her undergraduate and graduate degrees. Following her undergraduate graduation, she relocated to California for graduate school, but visited Rochester during the summers from 2012–2018.

All interviews were collected over the course of two years between 2016 and 2017 and this fieldwork also included ethnographic observations. To enlist speakers, the researcher tapped into various networks including churches, local activist groups, social media, and local colleges. Using the snowball method (Milroy Reference Milroy1980), people in these networks connected the researchers to other speakers born and raised in the area. The interviews took place in the interviewer's or interviewees’ homes, their workplace, or a reserved room in libraries. Speakers were asked a range of questions including where they grew up, where they attended school, how they have seen their communities change, whether they believe Rochester is a diverse city, and so on. Interviews ranged in length with the shortest being thirty-one minutes and the longest lasting one hour and forty-one minutes.

The variable: bought

I begin by discussing bought's properties in New York City English, but as I show below, its production among the Hood Kids in Rochester, New York, is distinguished by way of its movement and degree of dipthongization. In New York City English, bought is considered raised if characterized as having an F1 value lower than 700, and is also known for its inglide (Labov Reference Labov1966; Labov, Ash, & Boberg Reference Labov, Ash and Boberg2006; Coggshall & Becker Reference Coggshall and Becker2009). Labov (Reference Labov1966) documented bought-raising in his work in the Lower East Side, finding a change in progress led by upper working class and lower middle-class speakers, as well as women and Jewish speakers. Recently, Becker's (Reference Becker2014a) return to the Lower East Side revealed a reversal of the pattern among white ethnic groups, Asian Americans, and LatineFootnote 5 Americans. She reasons that the reversal may be a result of the stigma attached to New York City English features, as well as speakers disassociating with the white ethnic New York persona to which it is attached. Despite the reversal, African Americans appeared to maintain bought-raising, displaying some of the highest means across her sample. In contrast to Labov's (Reference Labov1966) findings that African Americans were not raising bought to the same degree as white speakers, Becker finds raising among older African Americans and maintenance of this patterns among younger generations of speakers.

Alongside the production data, Becker also conducted a matched guise experiment with speakers from New York City to explore the social meaning of the variant. Raised bought was associated with older and working-class speakers from the outer boroughs, as well as members of white ethnic groups like Jewish and Irish Americans. These findings corroborate what has been found in production data for older white Americans in the Lower East Side, but it is unclear the extent to which the feature is becoming indexical of a particular kind of localized African American identity given its prevalence among African Americans’ speech. Becker also explored the qualities associated with users of this variable and found bought-raisers were characterized as aloof and mean, features she attributes to a ‘classic New Yorker’ persona.

The stereotype of the working-class New Yorker from Jewish, Irish, or Italian descent is a highly enregistered persona even for non-New Yorkers as is evident across popular culture. Instantiations of this persona appears in sitcoms, dramas, and variety sketches like The Nanny, The Sopranos, and Saturday Night Live's ‘Coffee Talk’ (Becker Reference Becker2014a; Wong & Hall-Lew Reference Wong and Hall-Lew2014). For example, Linda Richman's production of coffee talk as cawffee tawk in her SNL skit contributes to an authentic performance of a New York character type. The tie between this persona and the raised bought has been reproduced through the sale of commodities like the Brooklynese Cawffee Mug (Becker Reference Becker2014a), reifying raised bought as indexical of the quintessential ethnic New Yorker, Jewish American.

Despite white ethnic groups representing the stereotypical New Yorker, other ethnic groups can draw on the linguistic resource to index aspects of their regional identities. Given a variable's indexical field is fluid, it can accrue new associations, being reinterpreted in the context of different styles and interactions. The reconstrual of these meanings is not random but has some ideological connection to previous indexical values of the variable (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003). In Becker's (Reference Becker2014b) work where African Americans living in the Lower East Side have become the dominant users of bought-raising, she finds intraspeaker variation across topics for the speaker, Lisa, a young, African American woman from The Lower East Side. When Lisa assumes that her interlocutor is from the region, she uses the non-raised variant. However, upon finding out that the interlocutor is a transplant vehemently opposed to affordable housing opportunities, Lisa uses the raised variant, and Becker argues that Lisa can adopt an oppositional stance toward the transplant by using the raised variant that indexes aloofness. The feature is not just about communicating racial identity, but a specific place identity that helps Lisa to construct herself as a certain kind of racialized, local subject in the Lower East Side.

Data preparation and measurements

The data come from ethnographic observations and sixteen sociolinguistic interviews and conducted among speakers (nine men, seven women) between the age of twenty-one and thirty-six. To investigate the relationship between bought and Hood, each speaker is coded as Hood if they articulated that they were Hood or grew up in the Hood (see quotes by Trey and Joseph as examples). Speakers who did not identify as Hood or as being from the Hood were coded as non-Hood. In the sample of sixteen speakers, seven (five men, two woman) were coded as Hood and nine (six women, three men) were coded as non-Hood.

Interviews were transcribed in Elan and forced-aligned into word and sound segments using the FAVE software package (Rosenfelder, Fruehwald, Evanini, & Yuan Reference Rosenfelder, Fruehwald, Evanini and Yuan2011). Praat scripts extracted the following vowel classes from stressed positions: beet, bit, bet, bat, ban (bat in prenasal environments), bought, but, pool. bought was the vowel of interest for this investigation, while the others were anchor vowels in the normalization of each speaker's vowel space. Due to observations of back vowel fronting for too (post-coronal boot) and boot, pool was used as the back anchor vowel. The velarization of /l/ in coda position retains the vowel in a back position.

An additional script was used to extract all tokens and manually adjust the adjacent consonant boundaries for up to twenty-five tokens per vowel class. No more than two tokens per lemma were accepted, except in the case of pool, which occurs less often. With the exception of pool, tokens preceding a vowel, glide, /r/, or /l/ were excluded, as were tokens following a vowel, glide or /r/. Vowels less than seventy milliseconds were not included in the twenty-five tokens. A total of 3,048 tokens were analyzed across all vowel classes, with 316 bought tokens submitted to regression analyses. A final script measured all vowels at 25%, 50%, and 75% into the vowel. The 25% and 75% measurements were used to observe the trajectories of the bought and were plotted in NORM (Thomas & Kendall Reference Thomas and Kendall2007) to examine the glide of said vowels considering that longer glides are important to NYC's production of bought. Observations of the glide in F1 and F2 plots (examples in Figure 2) revealed that the glides are short, suggesting a more monophthongal production of the feature. Additional analyses done on the delta values (75%–25%) for the F1 and F2 of each vowel were submitted to regressions and no main effects or interactions emerged.Footnote 6 Subsequently, only mid-point analyses are presented below.

Figure 2. Vowel plots for speakers labeled as Hood (white box) vs. non-Hood (black circle).

All vowels were normalized using Traunmüller's (Reference Traunmüller1997) formula to convert Hertz values to Bark values, accounting for how speech is filtered and heard through the human ear. Further, the Watts and Fabricius modified method (Fabricius, Watt, & Johnson Reference Fabricius, Watt; and Johnson2009), was used to normalize vowel formants based on three corners of speakers’ vowel spaces since not all the vowels in the speakers’ vowel systems were extracted and plotted. These corners include the high front vowel, the high back corner, and the bottom corner. Further, this method of normalization allows one to compare formant values of different vowels for each speaker. The resulting normalized formant values were submitted to various analyses.

Data analyses

As the Hood Kid and the New York Nigga both draw on similar semiotic resources like clothing (Timbs and NY-Yankee Fitted Caps) and linguistic items (mad as an intensifer) to construct these personae, the bought vowel may be an additional site of meaning-making for the Hood Kid. To explore this question, I examine how the production of bought varies between the participants who identify as Hood and those who do not. If this is a socially meaningful variant for the Hood Kids, the expectation is that they will differ from their non-Hood identifying peers and that the difference will trend in the direction of what has been reported for New York City speakers. To evaluate such differences, the data was submitted to different linear mixed-effects regressions. These models were created in R using the Lmer function (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2014) and p-values were obtained using the LmerTest package. The simplest models were constructed with additional fixed effects included incrementally. The included models are those with the best fit, evaluated using the anova function in R, and there were no significant interactions. In the first model, I assess the dependent variable, F1 midpoint values, which inversely correlates with height, while the second model assesses F2 midpoint values, directly correlated with backness, as the dependent variable. For both models, hood status, gender, birth year, and duration (log-transformed, given the time-series data) are all included as fixed effects, while participant, word, and preceding and following environment are included as random effects.

Results

We can examine the envelope of variation for bought-raising and lowering in Figure 2. Though there are several differences in the vowel space relative to its shape for either sets of speakers, bought is the focus of this analysis. The mean for all the speakers labeled as Hood (white squares) appears more raised and retracted than those labeled as non-hood (black squares). However, the trajectories of this vowel for both groups appear similar in length, though bought is slightly longer for the Hood kids and facing downward, consonant with previous observations in NYC (Coggshell & Becker Reference Coggshall and Becker2009).

In Figure 3, there are two plots representing a speaker who identifies as a Hood Kid, Joseph, and a speaker who does not identify as a Hood Kid, Melanie. All Black speakers recognize ‘the Hood’ as a reference point in the landscape, but speakers like Joseph and Trey also self-identify as Hood Kids, explicitly establishing themselves as having grown up in this space and adopting attitudes and practices associated with it. By contrast, Melanie, a local planning to relocate within a few years of the interview, distanced herself from the hood by distinguishing herself as having ‘lived up the street from the ghetto’, but not inside it. She also explains that she did not participate in the activities associated with that space and such positioning exhibits the ideological construction of place beyond geography. Both speakers show qualitative differences in their production of bought such that Joseph's bought vowel is positioned higher in his vowel space. The F1 value is a little less than 1.2, slightly higher than bet. In relation to bot's F1 value, there is a large amount of phonetic distance such that the ellipses do not overlap. The ellipses show the extent to which tokens fall one standard deviation from the mean.

Figure 3. Vowel plots for Joseph (Hood) and Melanie (non-Hood).

In Melanie's plot, bought is positioned lower such that its F1 value is greater than 1.2. In addition to having a higher F1 mean, Melanie's bought mean has a higher F2, appearing fronter than Joseph's bought. Both patterns, the raised and backed variant and the lower and fronted variant, are observed across speakers’ vowel plots. Like, Joseph, Melanie does not show any overlap between bought and bot, though there is less distance between the two vowels in Melanie's plot. The distance between bought and bot are expected for both speakers given the relevant vocalic systems for this region (e.g. Northern Cities Shift) and this racialized group (African American Vowel Shift). Both speakers’ bought vowels show short trajectories, inconsistent with what has been found for the New York City bought vowels, but the variance observed indicates that Rochesterians are reanalyzing the vowel such that the height and backness seem to be more important dimensions to examine across this community of speakers.

In addition to the vowel plots, we can observe the speakers’ means across persona type by F1 and F2 to examine their range of variation. In Table 1, the values are listed in increasing order with the lowest values atop and the greatest values at the bottom of the columns. The Hood kids (shaded) tend to cluster in the upper half of both the F1 and F2 values suggesting that these speakers tend to have lower F1 means, or higher vowels, and lower F2 means, or more retracted vowels, apart from one Hood Kid that falls in the lower half.

Table 1. Watt-Fabricius normalized F1 and F2 means listed from lowest to highest across Hood (shaded) and non-Hood (unshaded) speakers.

The differences observed across the height and backness means for the Hood and non-Hood speakers are plotted in Figure 4. The mean F1 value for the speakers that identify as Hood appear to be lower than those who do not identify as Hood. Furthermore, the range of variation for the Hood speakers appears to be wider and skewed toward lower values compared to the non-Hood speakers. Together the lower F1 mean and downward skew suggests that the Hood Kids produce higher bought tokens. With respect to the F2 means, the range of values is also skewed lower for the Hood speakers, though the envelope of variation is wider for the non-Hood kids in their F2 dimensions compared to their F1 dimension. The lower F2 values for the Hood Kids indicate more retracted bought tokens.

Figure 4. Jitter plot of Watt-Fabricius normalized F1 and F2 means for bought values across speakers coded as Hood (green) and non-Hood (red); F1 values are inversely correlated with height and F2 is directly correlated with backness.

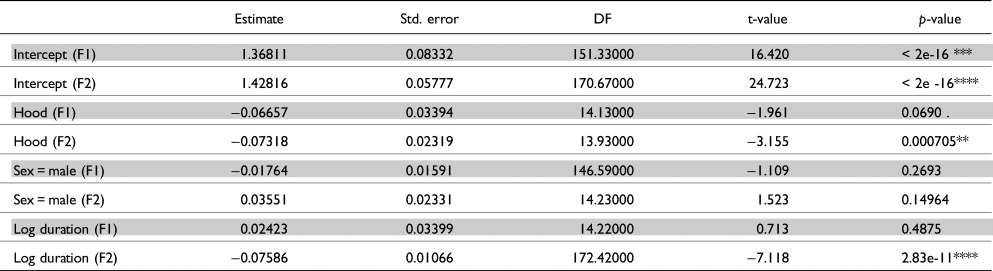

Table 2 shows the results for the linear regression model constructed to assess the F1 and F2 values across Hood identity. The F1 values (shaded), which appeared to show differences across Hood vs. non-Hood in Table 1 and Figure 4 differ only marginally across the two groups (p = 0.069). The results of the linear regression for the F2 (unshaded) values are also shown in Table 2. The observed differences in the production of F2 values emerge as significant in the model with the Hood speakers having lower F2 values than the non-Hood speakers (p < 0.001). Further, duration emerges as significant, with the retracted vowels tending to be shorter. Finally, there is no effect of gender or duration and no interactions in either model.

Table 2. Summary of main effects from linear mixed effects models with bought normalized F1 (shaded) and F2 values (unshaded).

Discussion

The social meaning of bought

Through music, pop culture, social media, and physical movement between Rochester and New York City, the circulation of linguistic and nonlinguistic resources become available for uptake and reconstrual. In the context of New York City, the raised bought has been associated with a quintessential older, working-class New Yorkers with white ethnic origins, such as Jewish speakers from the Lower East Side. However, Becker's (Reference Becker2014b) production data suggests that the uptake and maintenance of this pattern among African Americans may constitute a new order of indexicality that re-racializes such a pattern as African American. In the broader construction of Black personae like the Hood Kid or the New York Nigga, the use of the more raised and/or retracted variant can indirectly index (Ochs Reference Ochs, Duranti and Goodwin1992) the characteristics of the New York persona that Becker identifies as tough, defiant, or street-smart. Such qualities are consistent with Rochesterians’ conceptions of Hood as a ‘by-any-means-necessary, do what I have to do’ disposition. Though, this urban persona may specify macrosocial categories, around class, race, and gender, importantly, this persona does not itself embody the entire social group, African American.

The ability to exploit such meanings derives from the fact that the Hood Kid is an adequation of the New York Nigga, with the Hood Kids perceiving themselves as occupying similar social positions within the Rochester landscape and having to develop a resilience-as-toughness kind of attitude in response to their own blighted social conditions. Adequation requires similarity, but not sameness, thus, despite the similarity in the kinds of semiotic resources used, there are still qualitative differences which make Rochester's performance of Hood unique to their region, but still recognizable as a broader New York State kind of style. The bought vowel does not have the same ingliding as those associated with the New York City raised bought, nor is the raising as extreme as observed among New Yorkers. Thus, the feature has been reanalyzed and the performance is not an exact replica, but systematically varies in the same direction as the New York City variant. In avoiding the exact reproduction of such a feature, perhaps Rochesterians can sound both Black and from New York State, without being read as inauthentic posers pretending to be from New York City.

Finally, the production of retracted bought feeds into a larger discussion regarding the relationship between low back vowel production and sound symbolism. In Eckert's (Reference Eckert2010) examination of a preadolescent girl's use of bot and bite, she found that fronted productions occurred during performances of more childlike sweetness, and backed productions occurred when expressing more negatively valenced emotions like fear and annoyance. Further, Pratt's (Reference Pratt2020) investigation of tech kids in a San Francisco arts high school revealed that this group of students, described as ‘badass’ and ‘tough’, produced significantly higher bot vowels, in addition to velarized /l/ variants. She argued that together, these features constitute an articulatory setting that embodies toughness. Considering this work, we can view the Hood Kids’ retracted production of bought as iconic of a kind of tough or hard affect. If bought retraction and raising can do the work of toughness in this community, when stylistically combined with the other semiotic resources, perhaps speakers can project urban personae ranging from street-smart to hustlers.

Scaling and adequation

While regional variation is apparent in the study of AAL, less work is done to consider why and how such variation emerges and is maintained cross-regionally. This case study of two related personae reveals the flexibility of place and how participants ideologically establish such through meaningful linguistic and nonlinguistic practices. While such research began with a determined sense of place defined by specific geographic boundaries and a specific vowel shift region, the results speak to the permeability of such confines via ideological comparisons. As Lempert and Carr (Reference Lempert, Summerson Carr, Lempert, Summerson and Carr2016:4) suggest, ‘people are not simply subject to preestablished scales; they develop scalar projects and perspectives that anchor and (re)orient themselves’. Understanding how participants engage in scale-making explains how linguistic variation, beyond vocalic variables, appears in unexpected or distant places, while also drawing on participants’ epistemologies, rather than a priori contrasts. Finally, examining the adequation of such signs, such as bought movement, contests the regimentation of recognizable categories (Rosa & Flores Reference Rosa and Flores2017) such that sociolinguists do not overdetermine the linguistic behavior of racialized individuals in the study of AAL and other minoritized varieties. That is, attending to both the perception of social positionings across both landscapes, and the uniqueness in the production of similar vocalic patterns invites us to consider and name the sociohistorical racial projects that influence such ideological comparisons across regions, while also recognizing the mutability of such signs that can be used to communicate such social distinctions.

The limits of the ethnolect

Deeper explorations of subphonemic variation across African Americans’ speech can inform our understanding of place identity in this community. Accounting for heterogeneity across and within African American communities requires expanding sites for observing meaningful variation in African Americans’ speech beyond the traditional variables (King Reference King2020). We can identify local social distinctions that set one group of speakers apart from another, while also identifying similarities across groups, even if not identical. The Hood Kid is distinguished from others in the community not only in their production of particular vocalic variables, but also in how they ideologize place, how they enact those ideologies through practice, as well as how those ideologies are informed by their material conditions. Recall research identifying the Mobile Black Professional as a kind of persona which looks to distance themselves from the immediate landscape of Rochester in hopes to relocate to larger urban centers further south or west in the United States (King Reference King2021). While these personae are both Black and from the inner city, the way they scale place differs. That is, the Hood Kid relies on relating to the urban center and remaining in state, whereas the Mobile Black Professional relies on relating to other professionals beyond the state. Such a contrast reveals different scalar projects and displays the negotiation of place identity from different perspectives, despite growing up and living within the same social landscape. Thus, in our broader call to study regional identity and language in dialectology or across African Americans’ speech, we cannot take place for granted as stable or fixed, but always as a kind of production from multiple vantage points (Carmichael Reference Carmichael2023). While it may be methodologically difficult, it appears necessary to account for multiple constructions of locality and race within a given community and to attend to multiple conceptions of place.

The results of this work have important consequences for how we theorize about the dialectal status of African American English and other ethnolects, more broadly. Such concerns have been discussed in more recent work by Benheim & D'Onofrio (Reference Benheim and D'Onofrio2023) in their analyses of regional variation across Jewish communities in Chicago versus New York City showing that the uptake of features associated with the ethno-religious repertoire of New York City are mediated by both class and place ideologies. That is, a single set of dialectal patterns more canonically associated with Jewish identity, does not account for all speech by Chicagoan Jewish speakers. This point is underscored in work on Asian-American communities, such as Chinese speakers in San Francisco and New York City who were shown to produce bought in ways that matched the patterns of their respective regions, rather than exemplifying a singular ethnic pattern (Wong & Hall-Lew Reference Wong and Hall-Lew2014). Wong & Hall-Lew argue that the indexical potential of such a variable can point to ethnicity, place, and the intersection of the two.

It is evident that in a purely ethnolect-driven framework which maps a variety to a racial group, we cannot explain the variable uptake of this regional pattern in Rochester, New York. Though not an indictment on the study of African American English, the variation in the raising and retraction of bought, suggests the need to resituate the relationship between African Americans and their language production so as not to erase the various productions of regional and racial identities (King Reference King2020). No one linguistic variable is inherently Black, and its indexical potential is a negotiation amongst the communities in question. African Americans constitute a heterogenous collectivity (Collins Reference Collins2000) and there are multiple ways to account for such diversity, while also acknowledging shared membership including drawing on constructs like the persona (Agha Reference Agha2005; D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020) in community studies, as well as drawing on more general repertoire analyses which view speakers as having a toolbox of features at their disposal to draw on for different means of doing identity work (Benor Reference Benor2010; Becker Reference Becker2014b). As Becker states about Lisa from the Lower East Side of New York City, ‘If she is multivalent with respect to her identity, we should expect her to be multivalent in her linguistic practice as well’ (Becker Reference Becker2014b:47).

Conclusion

Recognizing the heterogeneity in African Americans’ speech supports a broader use of the label African American Language (Lanehart Reference Lanehart2015), whereby we acknowledge the patterns of all African Americans regardless of whether speakers use the more canonical patterns documented in the earliest studies of African Americans’ speech. Sociolinguists’ study of cross-regional variation in African Americans’ speech does not need to maximize distinction between speakers in order to locate meaningful variation but can also focus on finding similarities within language use and lived experiences beyond the use of the most vernacular patterns. That is, in addition to attending to semiotic practices of distinction we can view adequation as an important semiotic practice of indistinction or purposeful unmarkedness and imprecision. The Hood Kid's placement in the social landscape signifies a complex relationship between race, place, gender, and class and the racialization of space suggests that what constitutes locality is affected by how racial groups have been historically positioned within a community, as well as how they navigate such positions. Through this work, I am advocating to consider not just the racial group or the regional dialect, but to consider African Americans’ ethnospatial epistemology, or the local knowledge of being Black and from a certain space, in hopes to move toward fuller descriptions of Black speech. As is evident in the study of the Hood Kid, speakers are not just from the Hood, but are doing Hood in their dress, their speech, and their social activities. Further, this social group, which is historically associated with the most vernacular patterns, draws on a host of other linguistic cues in addition to the most stigmatized ethnolectal patterns. Attending to the local social distinctions of African Americans extends our theory on stylistic variation, while continuing varying representations of the social group.