Introduction

Over the past thirty years, the role of ‘social meaning’ in processes of language variation and change has become more central within variationist research. Social meaning is less directly observable than, for instance, a variable's linguistic constraints. Many researchers have explored the social meaning of variation using ethnographic methods (e.g. Eckert Reference Eckert2000; Moore Reference Moore2003; Kiesling Reference Kiesling2004); others have used experimental methods (e.g. Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2007; Pharao & Maegaard Reference Pharao and Maegaard2017). In general, both approaches have explored contemporary patterns of language use; however, there have been a handful of studies which have begun exploring the social meaning of variation in the past, using oral history archives (Moore & Carter Reference Moore and Carter2015, Reference Moore, Carter, Montgomery and Moore2017; Leach Reference Leach2021). Exploring social meaning in archive data has an added layer of difficulty, in that direct interaction with the speakers is usually not possible, either because they are no longer living, because they cannot be contacted, or because their identities are unknown. However, such research offers a unique insight into the social motivation for language change—particularly for changes that are now completed or near-completion.

Our article builds on the use of archive data in variationist research by applying a modified version of the lectal focusing in interaction (LFI) method (Sharma & Rampton Reference Sharma and Rampton2015; see also Sharma Reference Sharma2018) to oral history interviews. This method tracks a speaker's variation through the course of an interaction. Their shifts towards or away from certain variants can then be explored in relation to the non-linguistic shifts that are occurring in that interaction: for example, changes in the speaker's orientation. Linking particular orientations to the use of particular variants arguably allows an insight into the social meaning of these variants (Nycz Reference Nycz2018). Our approach differs from Sharma & Rampton's, and in doing so develops their method and expands its potential uses. While they use the method to explore a set of categorical variables, we use it to explore a single variable which we choose to treat as continuous, not categorical: rhoticity.

Our data comes from recordings currently being digitised as part of the British Library's Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project, which have been made available via the project's North-West regional hub based in the Archives+ section of Manchester Central Library. It consists of six oral history interviews conducted in the borough of Oldham, North-West England, in the late 1980s, with speakers born between 1893 and 1929. Since 1974 Oldham has been a borough of Greater Manchester, but prior to this, and during the periods under discussion in the recordings, it was split between Lancashire and Yorkshire. All of the speakers have variable rhoticity, a linguistic feature which occurs only rarely in contemporary speech in the area (Leemann, Kolly, & Britain Reference Leemann, Kolly and Britain2018). We use this data to view a snapshot of this change in progress, and to investigate possible social motivations for the change.

We first account for the linguistic constraints on variation and explore macro-level social patterns, discovering a gender split inviting further investigation, where the three men are more rhotic than the three women. Focusing in on two speakers of different genders by way of example, we use a modified version of the LFI approach to explore the social meaning of rhoticity for these speakers. Our analysis sheds light on social meaning during a change in progress, and how individual and demographic differences in overall rates may emerge from differences in social positioning and orientation.

The data

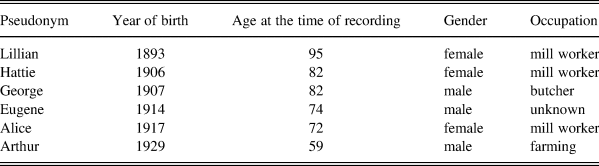

The interviews were conducted by BBC journalist Alec Greenhalgh and focused on the interviewees’ memories of growing up in the area. Table 1 contains the demographic information we have available for the six speakers we focus on.

Table 1. Demographic information for speakers.

Each interview is between one hour twenty-one minutes and two hours eleven minutes, giving us a dataset of eleven hours twenty-six minutes in total. We transcribed and analysed between thirty-four minutes and forty-one minutes per speaker (three hours and forty-three minutes in total), choosing sections to cover as wide a range of topics as possible. The topics covered include education, childhood games, family life, the two world wars, traditions, and descriptions of the neighbourhood. The resulting interviews provide a rich portrait both of turn of the century Oldham and of the interviewees’ life stories, attitudes, and orientations.

Rhoticity

Rhoticity in Oldham

When the fieldwork for the Survey of English Dialects (SED) was conducted in the 1950s, rhoticity was a fairly widespread feature in England (Orton, Sanderson, & Widdowson Reference Orton, Sanderson and Widdowson1998:Ph11). The regions where robust rhoticity was recorded at this time were the South-West of England, an area near the Scottish border in the North-East, and a region roughly corresponding to the county of Lancashire in the North-West.

Oldham, the region that we focus on in the current study, is on the border between rhotic Lancashire and its neighbouring, non-rhotic regions. It was not among the areas captured by the SED, and consequently the various maps produced using the data disagree about the presence or absence of rhoticity in Oldham in the 1950s (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1990:53; Orton et al. Reference Orton, Sanderson and Widdowson1998:Ph11; Chambers & Trudgill Reference Chambers and Trudgill1998:95). However, the interviews we analyse clearly show that variable rhoticity was present in the speech of older Oldham residents in the 1980s, strongly implying that it was also present in the 1950s.

Regarding more contemporary accounts of variation in the region, the English Dialects App (Leemann et al. Reference Leemann, Kolly and Britain2018) asked users to self-report on their rhotic pronunciation. Results were collated to create a series of dialect maps suitable for comparison with maps produced using the SED. The contrast is stark: rhoticity is only self-reported in the South-West of England and in a small area around Blackburn in Lancashire, with Oldham labelled as non-rhotic.

Even in the areas where rhoticity survives, ‘existing dialectological research predicts that this is under sociolinguistic pressure from speakers in surrounding areas where non-rhotic speech is the norm’ (Barras Reference Barras2011:3; see also Britain Reference Britain2009). In Oldham in the late 1980s therefore, rhoticity was a change in progress, with the observed rhoticity in our oral history interviews set to disappear from the community within the following thirty years. Our question is, what did this fading feature mean to the speakers who were using it at this time?

Rhoticity measurements and analysis

In studies of rhoticity, the most common method is to use auditory analysis to code tokens as either rhotic or non-rhotic (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1972; Hay & Sudbury Reference Hay and Sudbury2005; Becker Reference Becker2009; Barras Reference Barras2011; Piercy Reference Piercy2012), but there are some questions about the reliability of this method (see Yaeger-Dror, Kendall, Foulkes, Watt, Eddie, Harrison, & Kavenagh Reference Yaeger-Dror, Kendall, Foulkes, Watt, Eddie, Harrison and Kavenagh2008; Lawson, Stuart-Smith, Scobbie, Yaeger-Dror, & Maclagan Reference Lawson, Stuart-Smith, Scobbie, Yaeger-Dror, Maclagan, Di Paolo and Yaeger-Dror2011:74–75). The potential unreliability of auditory coding of rhoticity may stem from the fact that rhoticity varies on a gradient scale. As such, both Lawson and colleagues (Reference Lawson, Stuart-Smith, Scobbie, Yaeger-Dror, Maclagan, Di Paolo and Yaeger-Dror2011:76) and Heselwood, Plug, & Tickle (Reference Heselwood, Plug, Tickle and Heselwood2010) suggest that the inter-rater reliability of auditory coding can be improved by the addition of at least one intermediate category. Another, potentially more reliable, measure of rhoticity is minimum F3. As noted by Thomas (Reference Thomas2010:131), English rhotics generally ‘share the acoustic characteristic of lowered F3’, where the lower the F3 value, the greater the degree of constriction in the vocal tract (see e.g. Hay & Sudbury Reference Hay and Sudbury2005; Hay & Maclagan Reference Hay and Maclagan2012; Love & Walker Reference Love and Walker2013). One benefit of using minimum F3 as a measure of rhoticity is the ability to examine shifts in rhoticity on a much more subtle, continuous scale. For example, Love & Walker (Reference Love and Walker2013) demonstrate that both English and US speakers significantly shift their use of rhoticity according to topic in such a way that is not necessarily auditorily perceptible but is certainly present in F3 measurements. However, there remain some disadvantages to using minimum F3 as the exclusive measure of rhoticity. In particular, Foulkes & Docherty (Reference Foulkes and Docherty2000) have cautioned that the increasingly common labio-dental variants of /r/ in the UK do not exhibit the same F3 lowering as bunched and retroflex variants.

Using minimum F3 to capture rhoticity on a gradient scale was a particularly attractive option in the present study. We are exploring subtle shifts in rhoticity throughout an interaction and, as noted by Love & Walker (Reference Love and Walker2013), these may not be reflected in a binary shift between rhoticity and non-rhoticity. However, given the potential drawbacks of using minimum F3 as the only measure of rhoticity, we additionally coded each token auditorily to verify that where the shifts were perceptible, this was reflected in the measurements.

As physiological differences in vocal tract length mean that raw minimum F3 scores are not always quantitatively comparable between speakers, normalisation is required. To do this, we also measured /r/ tokens in non-variable environments, that is, prevocalic /r/, and calculated a mean average minimum F3 for each individual speaker. Each non-prevocalic /r/ measurement was then divided by that number. As such, if a speaker generally has relatively high F3 when producing prevocalic /r/s (as was the case for the three women), the non-prevocalic /r/s are normalised relative to this. Although all of the speakers did show significant drops in F3 when producing /r/, this normalisation technique additionally accounts for any differing articulatory strategies that may affect F3.

All tokens of prevocalic /r/ and all potentially rhotic /r/s (i.e. near, nurse, square, start, north/force, cure, and lett er vowels preceding a consonant or pause) were analysed in the interviews with the six speakers. This resulted in a total of 1,814 prevocalic and 2,144 non-prevocalic /r/s across the six speakers. The dataset was then coded by the first two authors, with each taking half of the tokens. Using Praat (Boersma & Weenik Reference Boersma and Weenik2018), the lowest point of F3 for each of the /r/ tokens was measured by hand. Any tokens of /r/ that did not have a bunched realisation, such as trilled and labiodental variants, were excluded, as these variants may not consistently exhibit F3 lowering. Any prevocalic /r/ tokens where /r/ was not realised were also removed. The non-prevocalic /r/ tokens were additionally coded auditorily as present (/r/ fully realised), intermediate (some /r/-colouring), or absent (no evidence of /r/).

Inter-rater reliability was tested by a comparison of each researcher's coding of a subset of 100 tokens. Very high agreement was found in the minimum F3 measurements, with an average of only 57hz difference between the measurements, and < 300hz difference for 96% of tokens. Lower agreement was found for the auditory coding, at 66%. However, much of this disagreement was between intermediate and present codes. Additionally, ambiguous tokens (n = 233, 9% of the dataset) were noted during the coding and checked, discussed, and coded by the three authors and a fourth member of the wider research team. Any tokens that remained ambiguous were discarded. Taken with the much higher levels of agreement between the first two authors for the acoustic in comparison to auditory coding, minimum F3 was considered the most reliable measure of rhoticity in this study.

Rhoticity data overview

Figure 1 below shows a boxplot of normalised minimum F3 measurements for each speaker, coloured according to the auditory code. Speakers are ordered according to average minimum F3, with the lowest (meaning most rhotic) on the left. This shows a clear gender split in the data, with the three women all being less rhotic than the men. There is also, for all six speakers, a clear correlation between the auditory codes and minimum F3 measurements, demonstrating that F3 is a good representation of presence or absence of audible rhoticity in this dataset. Finally, Figure 1 shows a great deal of intra-speaker variation in F3, meaning that all the speakers vary in their use of rhoticity throughout the interaction. This is in line with our expectations that there was a change in progress towards non-rhoticity in Oldham at the time of the recordings. The following statistical analysis explores the linguistic constraints which may explain some of this variation.

Figure 1. Boxplot showing normalised minimum F3 measurements for each speaker, coloured according to the auditory code. ‘F’ and ‘M’ indicate a female or male speaker, respectively.

Previous variationist research on rhoticity has shown that both loss (Barras Reference Barras2011; Piercy Reference Piercy2012) and gain (Labov Reference Labov1972; Becker Reference Becker2009; Nagy & Irwin Reference Nagy and Irwin2010) of rhoticity is conditioned by a variety of linguistic constraints. Of these, Piercy's (Reference Piercy2012) account is particularly instructive, as it explores a large variety of constraints.

In line with Piercy (Reference Piercy2012), the present study models the effect of a variety of linguistic environments on non-prevocalic /r/: lexical set of preceding vowel, reduction of preceding vowel, and word context. Beginning with lexical set of the preceding vowel, each token was coded in line with Wells’ (Reference Wells1982) lexical sets. Both lett er vowels and those that are always realised as unstressed, such as forget, were coded as ‘schwa’. The word our, which has variable pronunciation, was coded auditorily as either start or schwa, where the latter represents an /aʊə/ pronunciation. Each token was also auditorily coded as ‘reduced’ or ‘unreduced’. Together with ‘schwa’ coded in preceding lexical set, this accounts for the effect of stress on /r/ production.

Word context was coded in line with both Piercy (Reference Piercy2012) and Nagy & Irwin (Reference Nagy and Irwin2010), although we do not include potential linking /r/ contexts in this study. Each token was coded as either pre-pausal, word-final followed by a consonant (e.g. another time), morpheme and syllable internal (e.g. work), morpheme final and syllable final (e.g. fairly), or morpheme final and syllable internal (e.g. years).

In addition to linguistic effects, this study tests the effect of two social factors, gender and birth year, on non-prevocalic /r/. Unfortunately, given the small size of the dataset and a very limited amount of demographic information about each speaker (see Table 1 above), we were not able to test factors such as social class or family links to the region. A full summary of the linguistic and social constraints we tested can be seen in Table 2 below, with examples and token counts for each category.

Table 2. Summary of social and linguistic effects on rhoticity, with examples and token counts. Categories marked with * were excluded from the analysis due to low token counts.

Rhoticity statistical analysis results

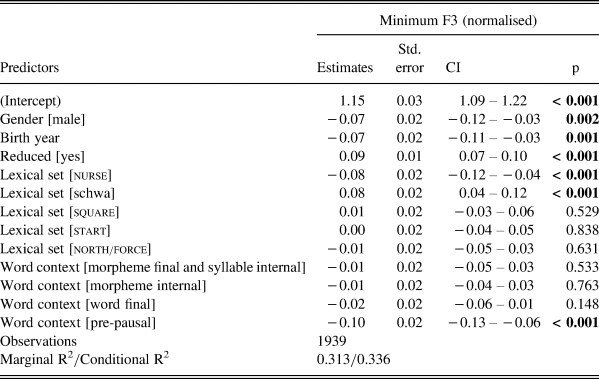

To test the effect on rhoticity of each of the social and linguistic constraints listed in Table 2 above, a linear mixed-effect regression model was fit with ‘Speaker’ as a random effect, and the normalised minimum F3 values as the outcome. The model was fit in R using lme4::lmer (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015). Following Winter (Reference Winter2019:263), afex::mixed (Singmann, Bolker, Westfall, Aust, & Ben-Shachar Reference Singmann, Bolker, Westfall, Aust and Ben-Shachar2021) was used to compute multiple ‘likelihood ratio tests’ on each of the fixed effects, which determined that they all significantly improved the model performance. The results of the mixed-effects regression analysis can be seen in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Results of the mixed-effects regression analysis of non-prevocalic /r/.

Beginning with the social factors, Table 3 above shows that both gender and birth year have a significant influence on rhoticity. First, the men have significantly lower minimum F3 than the women, suggesting that they are more rhotic. Indeed, a simple comparison of normalised minimum F3 values showed that all three of the women had lower levels of rhoticity than the men (see Figure 1 above).

The result for birth year was unexpected, as levels of rhoticity appeared to increase amongst the youngest speakers. However, we believe this is simply an artifact of the small dataset. Our youngest speaker, Arthur, was born in 1929 and was the most rhotic, while our oldest speaker, Lillian, was born in 1896 and was the least rhotic. Given that rhoticity was certainly a change in progress at that time, we think this is more likely related to the apparent gender effect than evidence that the change was reversing at this time.

Now turning to the linguistic constraints on non-prevocalic /r/ in this dataset, /r/ was much less likely to be present when the preceding vowel was reduced. Given that vowels are most likely to be phonetically reduced in unstressed contexts (e.g. Fourakis Reference Fourakis1991), this result is in line with previous research that has found a connection between stressed environments and /r/ use (e.g. Nagy & Irwin Reference Nagy and Irwin2010; Barras Reference Barras2011; Piercy Reference Piercy2012). The effect of stress on /r/ is also seen in the significant effect of lexical set of the preceding vowel, as schwa favoured /r/ the least. nurse favoured /r/ the most, and the other lexical sets cluster together in the middle. This is again in line with previous research on rhoticity, in which nurse favours /r/ in contexts where rhoticity is being gained (Nagy & Irwin Reference Nagy and Irwin2010), lost (Piercy Reference Piercy2012) and, interestingly, remerging (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2002). Regarding word context, word-final, pre-pausal environments favoured /r/ the most, as expected, and the three word-internal contexts roughly clustered together. Pre-pausal contexts most favouring /r/ is a robust effect across multiple studies (e.g. Bartlett Reference Bartlett2002; Nagy & Irwin Reference Nagy and Irwin2010; Barras Reference Barras2011; Piercy Reference Piercy2012).

Overall, this analysis has shown that the change toward non-rhoticity in Oldham was, in the 1980s, patterning as expected. Rhoticity was occurring most often following the nurse vowel and in pre-pausal contexts, and unstressed contexts (both following a reduced vowel and in unstressed syllables) disfavoured rhoticity. Although the small sample size means the apparent gender split should be treated with caution, women appear to be following the well-established tradition of leading the change (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1990), with all three being less rhotic than the three men.

However, as shown in Table 3, the conditional R2 value for the model is fairly low (0.336). This essentially suggests that around 34% of the variance in the F3 values is explained by the fixed and random effects in the model, meaning there remains quite a lot of unexplained variation. This is likely to be partly due to both the low number of speakers and the lack of demographic information we have about them. However, as shown in Figure 1, there are also high levels of intra-speaker variation that are evidently not explained by the linguistic factors alone. Therefore, in the section below, we use two case studies to explore the extent to which this variation may be socially motivated. Specifically, we examine how the intra-speaker variation may provide insight into the gender split we have observed in this analysis. Although this gender split is in line with widely observed patterns in language variation and change, it would be reductive to assume that women lead the change to non-rhoticity in Oldham simply because that's what women do. Instead, we examine how two speakers—the most and least advanced in the change—shift in their use of rhoticity throughout their interviews and consider how this aligns with the topic of discussion and their orientation towards the topic in that particular moment. We suggest that, in this instance, the widely observed pattern of men lagging behind women in the sound change may be grounded in a tendency to orient towards the ‘good old days’, while the women tend to orient toward modernity.

Investigating social meaning

Lectal focusing in interaction

To investigate how rhoticity patterns in interaction, we use a modified version of Sharma & Rampton's lectal focusing in interaction (LFI) method (Sharma & Rampton Reference Sharma and Rampton2015; see also Sharma Reference Sharma2018). Sharma & Rampton segmented their data into turn-constructional units and coded each unit for a set of thirteen variables, organised according to their association with contrasting lects. They then used a proportional measurement to calculate the degree to which a speaker was orienting towards a particular lect in each turn-constructional unit. (Sharma & Rampton Reference Sharma and Rampton2015:13). They note that their method could be modified to track individual variables, a modification which ‘might be preferable in situations where broad indexical values of variables are unclear’ (Sharma & Rampton Reference Sharma and Rampton2015:12). Taking this cue, we adapt the method and track one individual variable: rhoticity. This more exploratory approach makes sense in relation to our analysis, as the indexical value of rhoticity is not known a priori. Because we are tracking just one variable, we do not segment our data and take proportional measurements for each segment. Instead, we track changes in each speaker's level of rhoticity through the course of their interview, creating time series plots to illustrate these changes (Figures 2 and 3). Focusing in on the peaks and troughs, we then explore what is occurring in the interaction at these moments: that is, at high and low rhoticity moments, are the speakers consistently showing particular orientations? When we identify moments of interest in the interviews, we take into account the possibility that the changes we see in the variation might be linguistically motivated as opposed to socially motivated, with reference to the quantitative findings presented in the previous section. When a speaker's level of rhoticity appears to increase, we note whether they are, for example, using more lexical items with the nurse vowel, a phonetic environment which strongly favours rhoticity.

Figure 2. Time series plot showing changes in Arthur's normalised F3 minimum over the course of his interview, with his lowest rhoticity moments marked.

Figure 3. Time series plot showing changes in Lillian's normalised F3 minimum over the course of her interview, with her lowest rhoticity moments marked.

Our approach necessarily differs from that of Sharma & Rampton (Reference Sharma and Rampton2015) and Sharma (Reference Sharma2018). Their choice to use a set of thirteen categorical variables means that they can hone in on relatively small interactional units, and look at which variants cluster within these units. Our adaptation of the method to focus on a single continuous variable requires that we look at patterns across the interviews more broadly. We lose some interactional detail in comparison to Sharma & Rampton, in that we need to analyse and discuss the interviews in larger units, but we make the following gains.

(i) We are able to explore rhoticity in greater linguistic detail, and more reliably, than we could if we coded the variable categorically.

(ii) We are able to explore a variable in which the social meanings of the variants are not known a priori, and not necessarily associated with contrasting lects.

Our adaptation of Sharma & Rampton's method expands its potential uses, making way for other, similar analyses of continuous variables and variables whose social meanings are not known a priori.

In the following section, we apply our modified LFI method to our oral history data. Can an examination of the variables’ social meaning shed further light on why we see the women leading the change in this particular time and place? Due to space constraints, we focus our analysis here on the most rhotic speaker, Arthur (M), and the least rhotic speaker, Lillian (F). However, in the final section we also comment briefly on the use of rhoticity by the other speakers in the sample.

Arthur

Arthur is the most rhotic speaker in the sample overall, and his level of rhoticity is highly variable. He was fifty-nine at the time of his interview, making him the youngest of the six speakers. However, despite this, he often returns to the subject of how different the world of the 1980s is from the world of his childhood. In comparing the two, he is consistently more positive about the past than he is about the present.

Figure 2 shows Arthur's time series plot for rhoticity. Levels of rhoticity within the transcript are tracked using LOESS, or locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. This essentially computes a best-fit regression at each timepoint on the x-axis based on a small range of datapoints in that ‘neighbourhood’ and weighted by distance from the timepoint. The blue line shows a smoothed representation of these individual regressions, indicating the overall trend of F3 across time. A lower F3 measurement indicates a higher degree of rhoticity, so peaks in F3 represent low rhoticity moments and troughs in F3 represent high rhoticity moments. Tokens are shown as points, colour coded according to the broad topic of conversation at that point in the interview to give a sense of the structure and content of the interview. However, we suggest that it is more fine-grained shifts in orientation from moment to moment which are important in relation to the speakers’ variation. The separate ‘panels’ reflect either tape changes or a jump to the next transcribed section.

The sections of the interview in which Arthur's F3 is lowest, indicating that his level of rhoticity is highest, are labelled in Figure 2 as extracts (1) and (2). The first of these, extract (1), represents a sustained period of high rhoticity lasting three minutes and four seconds. Below, we present the transcript for this section of the interview. However, due to space constraints, we present only samples taken from the beginning, middle, and end (this is also the case for extracts (2), (4), and (7)). All names in this and subsequent extracts are pseudonyms.

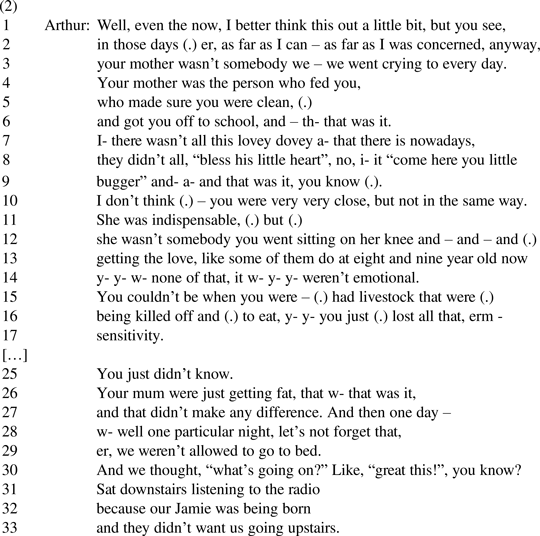

In extract (2), Arthur's level of rhoticity increases as he discusses how maternal relationships were different in his day, and how people were less sensitive in general. He goes on to say that pregnancy and childbirth were not discussed, so that when his younger brother was born, he had not been told that a new baby was coming.

As noted in the Rhoticity section, there are some environments which favour rhoticity more than others: in particular, rhoticity is favoured in the nurse lexical set, in unreduced tokens, and in tokens that occur in pre-pausal word-final position. All tokens occurring in variable contexts have the potential to carry social meaning; however, when rhoticity occurs in an environment which strongly favours rhoticity, we cannot be as confident that the rhoticity is socially motivated, as it is possible that it is entirely linguistically motivated. When rhoticity occurs in an environment which strongly disfavours rhoticity, we can have a higher degree of confidence. In extracts (1) and (2), some of Arthur's most rhotic tokens do occur in environments which favour rhoticity (e.g. work and weren't, arbitrator (.)), but others occur in environments which don't (e.g. forty, corporal, downstairs, and forget). This suggests that the observable shifts are not simply linguistically motivated, and may be at least partly socially motivated.

Arthur's interview suggests that he feels himself to be living in a rapidly changing world. When he was young, there was corporal punishment in schools, but “you accepted it” (extract (1), line 2) and it “didn't do you any harm” (extract (1), line 37). Life was tough, and there wasn't room for “all this lovey dovey… that there is nowadays” (extract (2), line 7), but children were tough too: he appears to disapprove of modern children “getting the love, like some of them do at eight and nine year old now” (extract (2), line 13). In extracts (1) and (2), he aligns himself with the older ways of life that he was raised with. At the same time, he increases his use of rhoticity.

Although we only have space to discuss these two extracts, they are representative of Arthur's tendency to orient positively towards the older generation, tradition, and older ways of life at particular moments throughout his interview. These moments generally co-occur with points of high rhoticity. For instance, he has high levels of rhoticity when discussing the superiority of the old school curriculum and, on several occasions, when highlighting the maturity and resilience that was required of children growing up on a farm. Based on the correlation of these orientations with high rates of rhoticity, we suggest that for Arthur, rhoticity has indexical links to tradition and older ways of life. This is perhaps not surprising, given that rhoticity was a change in progress at this time, and the most rhotic speakers in Arthur's life would most likely have been the older generation. For him, rhoticity may have therefore been associated with this older generation, and, through this association, with the older, traditional values they represented. It is also worth noting that Arthur's lowest rhoticity moments tend to occur at times when he is expressing an attitude of rebelliousness, irreverence, and opposition to authority. These moments are discussed in more detail and some examples are given in Dann, Ryan, & Drummond (Reference Dann, Ryan and Drummond2022), but they include descriptions of childhood misbehaviour like stealing, disobeying teachers, and fighting in the playground. It appears that Arthur may have higher levels of rhoticity when he is aligning himself with the values of the older generation, and lower levels of rhoticity when he is positioning himself as part of the younger generation coming into conflict with the older generation.

Lillian

Lillian is the oldest speaker in the sample and was ninety-five at the time of her interview. She is the least rhotic speaker overall, and like Arthur, her level of rhoticity is very variable. Lillian's two highest rhoticity moments occur when she is talking positively about her childhood, describing some of the traditional games she and her friends played. Like Arthur, higher rates of rhoticity may be associated, for her, with positive orientations towards tradition, older ways of life, and the ‘good old days’. However, she doesn't tend to positively orient to the past as frequently as Arthur. Indeed, an oppositional pattern appears to occur, where she uses less rhoticity when orienting towards modernity. Therefore, her lowest rhoticity moments are also of interest, and these are the moments we focus on in the remainder of the analysis.

Three of Lillian's lowest rhoticity (and highest F3) moments are labelled in Figure 3 as extracts (3), (4), and (7). We focus on moments where the vast majority of tokens are clustered with a high F3, and where it is unlikely that the F3 peak can be explained by linguistic constraints alone. For example, while linguistic constraints may play some role in the peak in extract (3), as some of the highest F3 (and lowest rhoticity) tokens are in environments which disfavour rhoticity (e.g. headmaster, standard, father), the extract also contains some high F3 (low rhoticity) tokens in environments which generally favour rhoticity (e.g. thirteen). Linguistic constraints do not offer much explanation for the F3 peak in extract (4); here, her lowest F3 (highest rhoticity) tokens are mostly in environments which do not particularly favour or disfavour rhoticity (e.g. marked, before, start). Linguistic constraints may play some role in the F3 peak in extract (7), where some of the highest F3 tokens disfavour rhoticity (unstressed contexts), but there are also high F3 tokens which do not particularly disfavour rhoticity (e.g. ordered, forwards, were).

The lack of clear linguistic explanations for these shifts suggests that it may be reasonable to look for social motivations. Therefore, we examine Lillian's orientations at these moments in the interview. In extract (3), she tells Alec that she was academically gifted, and completed her school's curriculum two years early. She was then asked to help with the youngest class during her last two years of school.

In extract (4), she again becomes less rhotic when she returns to telling Alec about her academic achievements.

These are the two moments in Lillian's interview where she most clearly displays a positive attitude towards school and education, and at both moments she becomes markedly less rhotic. At first glance, this behaviour appears to contrast with Arthur's in extract (1), where he becomes more rhotic when speaking approvingly about his school's firm disciplinary standards. This is in fact illustrative of a general pattern across all six of the speakers, in which the women become less rhotic when speaking positively about school and education, and the men do not. The other two women in the sample, Hattie and Alice, show a broadly similar pattern to Lillian, with some of their lowest rhoticity moments occurring when they are speaking positively about their educational experiences, or presenting themselves as good students who could have gone on to “something better”. In extract (5), a particularly low rhoticity moment, Hattie talks about surprising her teacher by writing a precocious piece of poetry at a very young age.

In extract (6), a particularly low rhoticity moment, Alice is giving a general description of her time at school, in which she displays a positive orientation towards education.

Why might this be the case? There are several possible explanations. One is that Lillian and the other women have experienced differing linguistic expectations in the classroom, perhaps with heightened pressure to conform to standardised language norms (for an overview, see Coates Reference Coates2013:ch. 11). However, another possible explanation relates to the proposed indexical links between rhoticity and respect for tradition and older ways of doing things. Perhaps these indexical meanings align with a positive orientation towards education for the men, and not for the women.

For Lillian, a positive orientation towards education is potentially at odds with respect for tradition and older ways of doing things. Lillian attended school from age five to thirteen, starting less than twenty years after the Education Act of 1880 had made primary school education for all genders compulsory. However, as summarised by Rose (Reference Rose1992:163), there remained little expectation or enforcement of school attendance for working class Lancashire girls, and when they did attend school, their education was ‘often geared to preparing them for their future domestic responsibilities’. Therefore, for women like Lillian, academic education was not part of the older way of doing things: it was something modern, even seen by some as threatening to traditional values and older ways of life (see e.g. Dyhouse Reference Dyhouse2012:103–104).

We suggest that, for Lillian, rhoticity may have indexical links to traditional values and older ways of life, and non-rhoticity may have corresponding indexical links to modernity and mobility. In extracts (3) and (4), Lillian is displaying a positive attitude towards education, but she is also depicting a possible alternative life for herself accessed through education, in which she could have ‘gone on to something better’ and ‘made a good journalist’ (extract (3), lines 17–18). This alternative life would likely have involved social and geographical mobility: taking on a middle-class profession and leaving the village she grew up in. It would have been a very different life from that of her parents and peers, as a journalistic career path had only very recently opened up to British women (Gray Reference Gray2012:4). As such, it would have been a move away from the traditional view of womanhood she grew up with. This alternative life never materialised for Lillian, as her family didn't have the financial means for her to continue her education, and she was obliged to leave school at thirteen and begin work in a cotton mill. But even at the age of ninety-five, as she talks to Alec about this alternative life, she moves away from rhoticity—the older, traditional variant associated with her local community—and towards non-rhoticity—the more modern variant, which was likely used by young urban professionals. This may be a part of her styling herself as a modern woman (from an early twentieth-century perspective) and turning away from the role assigned to her by established tradition.

Arthur and the other men in the study do not appear to decrease their level of rhoticity when orienting positively towards education, as the women do—at least not in the data sample we have available. But it may be that for them, education is not linked to modernity in the same way that it is for the women. As boys, their access to education would have been much more established and assured, and would not have stood in opposition to tradition and older ways of doing things.

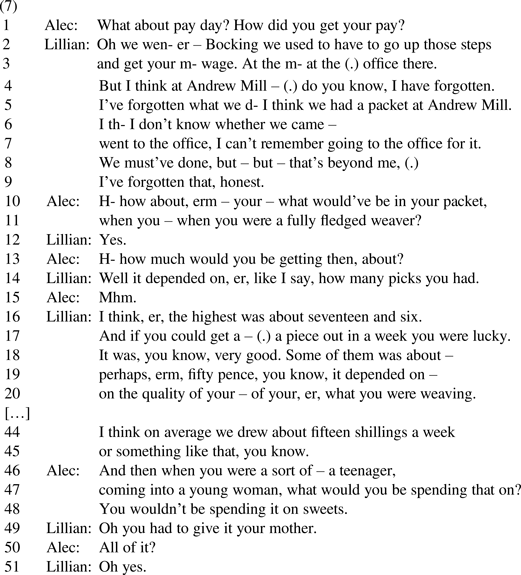

There is a third moment where Lillian's level of rhoticity decreases (and where this shift cannot easily be explained by linguistic constraints alone), marked as extract (7) and presented below.

In extract (7), Lillian becomes less rhotic as the topic shifts from a general description of life in the mills and towards how she was paid for her work. This moment is different from those shown in extracts (3) and (4), in that there is no clear orientation towards education, modernity, and mobility at this moment. It may be that the speaker's orientation in relation to tradition and modernity does not explain every fluctuation in rhoticity in the data: instead, there may be multiple processes at play simultaneously, as discussed by Sharma (Reference Sharma2018). In extract (7), the shift towards non-rhoticity may be triggered by the relative formality of the situation being described. It is also possible that non-rhoticity was the variant more likely to be used by those in managerial and administrative positions at the mill (see Leach Reference Leach2021 for findings on occupational role and /h/-dropping in the pottery industry in Stoke-on-Trent). When Lillian picked up her pay packet, this may have been the only time in her day-to-day life at the mill when she interacted with the managers and administrators, and in these interactions, it is possible that standard language ideologies or accommodation would have come into play, triggering a shift towards the more standardised variant. It is also possible that recalling these interactions may trigger a similar shift within the interview. Hay & Foulkes (Reference Hay and Foulkes2016:323) suggest that ‘[i]n discussing older events speakers may portray themselves as historical versions of themselves’, and in doing so, they may begin to speak more like they did at that time. Similarly, Lillian may be less rhotic when relating situations in which she would have reduced her level of rhoticity at the time. One such situation may well have been visiting the mill's office to pick up her wage packet.

Lillian has other low rhoticity moments for which we don't present extracts from the transcript, and which we don't examine in detail, due to space constraints. However, these do fit with the general pattern we observe. The first occurs at the beginning of Lillian_1 (see Figure 3), when she talks about memories of leaving her rural village to visit other parts of the country. For Lillian, it is quite possible that these trips out of her village are ideologically linked to mobility: a less permanent mobility than she would have experienced in her hypothetical career as a journalist, but mobility nonetheless. The second occurs at the beginning of Lillian_2, at a point where, as in extracts (3) and (4), she is talking about her academic achievements. At the end of Lillian_3, there is another low rhoticity moment where, as in extract (7), she is talking about being paid for her work in the mill.

Discussion and conclusions

We suggest that for these speakers, rhoticity may be ideologically linked to tradition and older ways of life, and non-rhoticity may be ideologically linked to modernity. That the ideological importance of tradition and modernity may have emerged in variation patterns for this generation is unsurprising, given that the early twentieth century was a time of social and economic change in the Greater Manchester area, as industry transformed, improved transport and communication increasingly connected the region and the world (Davies, Fielding, & Wyke Reference Davies, Fielding, Wyke, Davies and Fielding1992), and the suffragette movement secured votes for women (Purvis Reference Purvis2005). However, we suggest that the ideological link between rhoticity and wider discourses of tradition versus modernity is mediated through the local, and specifically through people in the speakers’ lives (as argued by Eckert Reference Eckert2008). Rhoticity loss in this part of England was well underway during these speakers’ lifetimes, and the most rhotic speakers in their lives were probably the older generation. At this point in the sound change, rhoticity may already have been perceived as old-fashioned, through its association with this older generation. This association may have forged an ideological link and opened up stylistic possibilities, where high rates of rhoticity can signal a positive orientation to the order generation and the traditional values they represent. The incoming variant, non-rhoticity, can in turn be used to signal an orientation away from these things, and towards modernity and mobility. For Arthur, positive orientations towards tradition and older ways of life at particular points in the interview coincide with higher levels of rhoticity, and for Lillian, positive orientations towards modernity and mobility at particular points in the interview coincide with lower levels of rhoticity. In the previous section we note how Lillian's pattern is reflected by the other women, and in Dann, Ryan, & Drummond (Reference Dann, Ryan and Drummond2022), we discuss the use of rhoticity by the other men, George and Eugene, showing a broadly similar pattern to Arthur's, albeit less exaggerated. Arthur and Lillian represent two extremes, both in terms of their levels of rhoticity and their orientations in relation to tradition and modernity, and they are ideologically opposed in their attitudes towards the past. For Arthur, his childhood is an idealised world that compares very favourably to the contemporary world of the 1980s. Lillian speaks positively about her childhood, but there is also implied dissatisfaction with the restricted opportunities this world gave her. For her, the older world appears to represent restriction of her potential, while for Arthur it appears to represent safety, comfort, and familiarity.

This ideological opposition is most clearly evidenced in Arthur and Lillian's interviews, but the other two women, Hattie and Alice, also express very similar attitudes towards education, and regret at having been obliged to leave school to work in the mills at age thirteen. Hattie, like Lillian, expresses a belief that she was unable to fulfil her academic potential because of the restrictions placed on her.

Alice also expresses dissatisfaction with the restrictions placed on her, both as a teenager unable to continue her education, and later as a housewife. Knowing the heavy domestic workload that would be placed on her later in life, her mother did not ask her to do household chores as a child.

Although the three women recall happy childhood memories, none of them appear to romanticise the past as Arthur does. In general, the women have a tendency to display similar orientations to Lillian with regard to education and modernity, and the men have a tendency to display similar orientations to Arthur: none of the men express the same feelings of restriction that the women do. This ideological difference is perhaps unsurprising, given the very different social positions of men and women at this time and in this place. For the women, more traditional ways of life may represent restriction, while modernity may represent opportunity and freedom. For the men, traditional life may not be so restrictive. We suggest that the gender difference we see in overall levels of rhoticity may be reflective of this ideological difference. The men have a tendency towards the use of rhoticity—the older, more traditional variant—and the women have a tendency towards the use of non-rhoticity—the more modern variant. In this way, demographic differences in overall rates may emerge from differences in social positioning and orientation. That women are often at the forefront of linguistic change is well-established (e.g. Labov Reference Labov1990). The locally situated details of female-led change are less well-established, and this investigation offers an insight into these processes in twentieth-century Oldham.

Despite the obvious challenges of investigating social meaning in archive data (see the Introduction), we build upon work such as Moore & Carter (Reference Moore and Carter2015, 2017) and Leach (Reference Leach2021) to demonstrate that explorations of this type are possible, and provide insight into potential social motivations for sound change. With regard to the challenge of applying LFI analysis specifically, we believe we have demonstrated that it can indeed be effective. Clearly, a major drawback of work with any kind of archive data is the difficulty of situating it within ethnographic observation (however, see Leach (Reference Leach2021) for a demonstration of how this kind of analysis could work). In the present study, the only data available were the audio recordings themselves, along with limited demographic information. However, the recordings described here are particularly appropriate for LFI analysis, as they are rich oral histories covering a variety of topics and regularly drawing on emotive memories. As such, they represent the opportunity to explore the ways in which the strategic (conscious or otherwise) deployment of variants align with interactional purpose, a relationship highlighted by Sharma & Rampton (Reference Sharma and Rampton2015:8) as contributing to the meaning-making process. Sharma & Rampton (Reference Sharma and Rampton2015:11) go on to explain how, in their work, they selected narratives for being ‘among those with the highest emotional engagement’. Again, this is covered by the nature of our recordings, as all involve quite emotionally charged memories at various points. The point is, while it is clearly difficult to work meaningfully in this way with the often-decontextualized nature of archive recordings, the challenge becomes less acute if the recordings themselves provide their own internal contextual depth. We have tried to demonstrate the effectiveness of such an approach in the analysis presented here.

We have also attempted to incorporate the effect of linguistic context into our analysis. To do this, we first modelled the effect of a variety of conditioning factors on /r/ use, determining which linguistic contexts most favoured or disfavoured rhoticity. We then selected points of interest from the LFI where moments of high or low rhoticity could not be explained by these linguistic factors alone. Another option would be to restrict the LFI analysis to a smaller selection of environments. However, this would be too restrictive in a study of rhoticity, as it is subject to a large variety of conditioning factors. In addition, our approach presupposes that either linguistic contexts favouring rhoticity will carry less social meaning, or that all linguistic contexts are equally socially meaningful. We cannot, of course, be entirely sure of this, and further (ideally experimental) work would be required to determine the extent to which different linguistic environments carry varying social meanings.

Despite the difficulties discussed above, we think there is great potential in using this type of analysis to explore social meaning in sound changes that are either completed or near-completion. As a result of this analysis, we now have some insight into what rhoticity may have meant to speakers as it transitioned from being a feature of the local dialect to a relic of the past.

Appendix: Transcription conventions

- (.)

noticeable pause

- -

abrupt stop in speech; truncated word or syllable

- –

speaker restart (dash surrounded by spaces)

- [laugh]

non-speech sounds