INTRODUCTION

Indexicality is a concept that can be used to identify the ways that language is embedded in and connected to social, conventional meaning that does ideological and normative work. Andrus (Reference Andrus2020b) explores indexicality in the context of police discourses and narratives about domestic violence (DV). She argues that discourses about DV can be traced indexically, identifying the ways in which DV is underpinned by social values that emerge in storytelling about DV. This article extends that research in an analysis of the ways that police officers show frustration in the stories they tell about DV victim/survivors.

According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (n.d.), ‘Domestic violence is the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another. It includes physical violence, sexual violence, psychological violence, and emotional abuse’. We have chosen to use domestic violence over intimate partner violence, because it is the term that police officers tend to use.

Stories about DV told by police officers instantiate and perform what Silverstein (Reference Silverstein2003) calls an ‘indexical order’ or ‘indexicality’. Indexicality refers to a process by which social meaning becomes linked to a linguistic form. That is, there are certain linguistic forms that index or trigger a relationship with social meaning. ‘Indexicality connects language to cultural patterns’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2007:115). Silverstein (Reference Silverstein2005:9) defines the index (Peirce Reference Peirce1940) this way: ‘Within any situation in which we participate, we can experience the relationship by a semiotic act of “pointing-to” which of course implies pointing-to from someplace (the arrow or the pointing finger starts somewhere and ends somewhere else)’. That is, indexicality implies both a thing that is pointed at—social meaning/social context—and a place from which the pointing occurs—a different context altogether.

Indexicality has come to mean something more social and ideological, but it still keeps its pointy-ness. An indexical form points at social meaning, while social meaning points back at the linguistic form, and this can happen multiple times, with many different social and contextual relationships forming with one linguistic form (Eckert Reference Eckert2008; Ochs Reference Ochs2012; D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2018; Andrus Reference Andrus2020a,Reference Andrusb). We propose that in stories told by police officers, we find indexicality. In the process of storytelling, police officers create a discourse, a wealth of narratives about DV and victim/survivors of DV that frame the context of staying in an abusive situation and the individuals who stay as frustrating. This set of narratives is available for any speaker in the context of policing to use and rearticulate for future use by future individuals with access to the set of narratives in circulation. The process of pointing and labeling from one context to another—police context to DV context—creates the indexical.

Indexicality is a concept that allows for the identification and articulation of the relationship between the ‘micro-social’ and the ‘macro-social’ features of text and talk (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003:193). As a linkage between the macro and the micro, the social and the linguistic, indexicality traffics in normative behaviors and discourses. According to Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2005:172), ‘Indexicality is one of the points where the social and cultural order enters language and communicative behavior’. Norms and social conventions emerge where the cultural meets the linguistic. Trinch (Reference Trinch2016) situates indexicality in the context of DV, arguing that indexicals create linkages that lead victims of DV to be blamed and held responsible for their own abuse and their in/ability to end the abuse.

The structure of indexicality is established in social norms and conventions, or social contexts. Indexicality ‘endows otherwise mere behavior with indexical significance that can be ‘read’ in relation to conventional norms’ (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003:197). Social contexts and norms are established and maintained interactionally through usage ‘between sign-users’ communicating in ‘context’ (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003:195). That is, sociality and context are constituted—presupposed and entailed—when people talk to each other in and about the context that is being established ‘by the fact of usage of the indexical’ (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003:195). Indexicality, then, is established through contextually and socially rich usage that creates and maintains indexical linkages (presupposition). Indexicality is linked to a group of users who do indexical work while interacting with and maintaining their groupness (entailment). That is, an indexical entails the context of use, and it presupposes that the user will be able to infer context and proper usage, such as when a police officer tells a story about an encounter with a victim/survivor that uses typified language in an expected context. The user of the indexical is presupposed to already understand the social nature, ideology, and function of use, or a user who can use the linguistic form in socially and contextually appropriate ways. Importantly, an indexical can have multiple, sometimes competing, meanings/usages, based on the social context and users of the indexical (Eckert Reference Eckert2008). ‘Linguistic features do not carry specific indexical meanings of their own, but can have different meanings in different clusters of features’ (Pharao, Maegaard, Møller, & Kristiansen Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Møller and Kristiansen2014:2). The specific meaning of an indexical depends on the contexts of usage and speakers.

This article considers a particular set of cultural and ideological discourses—police discourse about DV victim/survivors. Via the processes of indexicality, victim/survivors are entextualized as frustrations for police work. Johnson (Reference Johnson2004) shows that police are frustrated with victim/survivors. In this article, we look at how this frustration is constructed and circulated via discourse. We pinpoint two sociosemantic structures that index frustration: (i) the use of the word frustration, and (ii) narrative statements that initially show understanding and then mitigate that understanding with stories that index frustration. The linguistic features that signal ‘frustration’ function in police discourse as indexical features that can be used by police officers in order to describe encounters with victim/survivors. In short, this article argues that narratives about interactions between police officers and victim/survivors of DV do indexical work, creating linguistic structures that index frustration thereby framing and constituting victim/survivors as essentially frustrating.

In order to complete this analysis, we introduce two concepts: mitigated understanding is the introduction of understanding that is dismissed and mitigated via stories about frustration; and narrative indexicality, which are the narratives that propagate and distribute indexical forms that, in the case of police discourse, circulate feelings of frustration. In our analysis of narratives that police officers tell about victim/survivors, these two concepts articulate a notion of frustration in DV encounters that shape and give rise to particular notions about victim/survivors. Ultimately, we argue that through narrative indexicality, indexicals that point to ‘frustration’ constitute victim-blaming, by situating the victim/survivor as frustrating and situating them as the cause of their own harm.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND POLICE WORK

Law enforcement is polarizing, especially in the current sociopolitical context. Either the police force is lauded as upholding the law, maintaining safety, and establishing order, or it is condemned for racial profiling and violence (Champion Reference Champion2017:1). It goes without saying that in the context of DV, policing is just as fraught with contradiction (Martin Reference Martin1999:119). Andrus (Reference Andrus2020b) outlines multiple discourses that emerge when police officers tell stories about their work. Police narratives are available in discourses that circulate among and between officers, making them re/performable by the same or different officers in similar ways. Once the narrative performance is ratified through reiteration, it is available for reuse and distribution by the same and other officers. Because these elements of police narrative have been successful in the past, they can become habituated. Police ‘war stories’ create and establish myths that are perpetuated over time and over space, creating entextualized, ready-made stories for police officers (Fletcher Reference Fletcher1991; Kurtz & Upton Reference Kurtz and Upton2017).

Police work is dangerous, a point we want to establish upfront. In both the individual and group interviews Andrus conducted, police officers repeatedly noted how dangerous what they call ‘domestic calls’ are for police officers. Detective Tyler said, “[domestic calls are] the number—one of the top, if not the number one call that results in officer assaults, officer injuries. They're very dangerous calls to go on so we're pretty diligent in our safety”. This anecdotal assertion plays out in the literature. In a joint study, the US Department of Justice and the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund found that domestic calls represented 41% of fatal calls for service, second to traffic calls (Breul & Luongo Reference Breul and Luongo2018:21). Others reported that domestic calls were the third most deadly (Kercher, Swedler, Pollack, & Webster Reference Kercher, Swedler, Pollack and Webster2013; Blair, Fowler, Betz, & Baumgardner Reference Blair, Fowler, Betz and Baumgardner2016). Explicating the dangers of police calls, Detective Jacobs explains that police officers “start off basically with officer safety and ensure that there's at least two officers at this thing, because they're very volatile. It's probably the next dangerous thing next to a traffic stop”. Some of the literature corroborates this observation (Breul & Luongo Reference Breul and Luongo2018), while others claim that traffic stops are second in danger to ambush or armed robberies, or just as dangerous as domestic calls (cf. Garner & Clemmer Reference Garner and Clemmer1986; Kaminski & Sorensen Reference Kaminski and Sorensen1995; Kercher et al. Reference Kercher, Swedler, Pollack and Webster2013; Blair et al. Reference Blair, Fowler, Betz and Baumgardner2016).

After the relative safety of the officers and civilians has been established, the officers describe their job in terms of policy and protocol, referring to themselves as ‘fact-finders’ and claiming to have a neutral status in the situation. Police are there simply to find facts and establish the course of events. Sergeant Roberts explains it this way: “Most of the time, I'm there as a fact-finder and to establish what has occurred and how am I gonna weigh this to the interest of the criminal justice system based on what the facts of the case are—and then what the needs of the people are”. According to this and other officers, in any situation to which the police respond, the goal of police is to accumulate all of the facts and control the volatile situation. This role contributes to the multiple complexities found in domestic calls. At once, the officer must uncover the facts which could disclose a crime, after which they are required, by western state law, to make an arrest if an assault has been committed—this is a so-called ‘mandatory arrest’ state (See Hoppe, Zhang, Hayes, & Bills Reference Hoppe, Zhang, Hayes and Bills2020 for a history of mandatory arrest.)

METHOD AND METHODOLOGY

In this article, we operationalize theories of indexicality and narrative in a discourse analytic framework. We call what we do discourse analysis, broadly, because we are ‘studying language and its effects’ (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2008:2). The definition we use for discourse is a common one that we draw from Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2005). ‘Discourse is language-in-action, and investigating it requires attention both to language and to action’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2005:2). That is, the study of discourse is interested in how people actually use language rather than treating language as an abstract system (cf. Johnstone Reference Johnstone2008:3). ‘Discourse is what transforms our environment into a socially and culturally meaningful one’, writes Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2005:4). Research in discourse analysis, then, tends to be ‘interested in what happens when people draw on the knowledge they have about language, knowledge based on their memories of things they have said, heard, seen or written before, to do things in the world: exchange information, express feelings, make things happen, create beauty, entertain themselves and others, and so on’ (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2008:3). Discourse analysis focuses on the ways people use prior discourses and knowledges and anticipate future discourses and knowledges to accomplish the everyday goings-on in their lives. The present study constitutes a discourse analysis by paying attention to actual instances of speech. They are narratives told by police officers about DV and victim/survivors, elicited in interviews with Andrus. In particular, we pay attention to pronoun use, constructions of ‘frustration’, the repetition of the ‘be like’ construction, and the use of intensifiers.

In the present study, lengths were taken to put the interviewees at ease. For example, many were completed in groups, and in at least one interview, the context was entirely informal with police officers moving around freely in their break room and telling stories as much to and with each other as to Andrus. We do recognize, however, that the context of the interview and the process of talking to a veritable stranger still circumscribes the narratives in many ways. As with any production of discourse, the stories were certainly formed and shaped for the audience in contextually rich ways. Out of these interviews, rich data emerged in candid stories about DV victim/survivors, including narratives about frustration in the context of domestic calls. Narratives about frustration and the use of the word frustration were entirely introduced by the police officers themselves. The interviewer never used the word nor asked a question intended to measure police officer frustration. Narratives about frustration are almost always introduced with a very brief statement of understanding or empathy that is quickly mitigated with a longer story of frustration, which we call mitigated understanding. The configuration of mitigation that we are working with is concerned with the process of curtailing or downgrading an element that was initially introduced as important in the story and is then mitigated or interrupted by another portion of the story that is presented as doing more ideological work and carrying more narrative weight. In our case, it is understanding that is reduced, interrupted, and/or complicated—mitigated—by frustration.

The data analyzed in this article were collected in a city in the western US in the summer of 2018. In order to keep the participants absolutely anonymous, no personal or demographic information was taken and each participant selected their own pseudonym. This was in accordance with the IRB expectations at Andrus’ institution. Andrus collected interviews from both victim/survivors and police officers and personnel, though only police officer interviews are analyzed in this article.

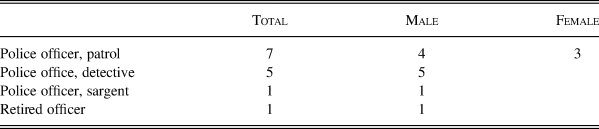

A total of fourteen law enforcement officers (detectives, retired and active officers, and a sergeant) were interviewed in fourteen interviews. Three of the fourteen officers presented as female, while the rest presented as male (see Table 1). And three of those interviewed (one woman and two men) disclosed that they had either been the victim/survivors of DV and/or were related to or in a relationship with someone who was a victim/survivor of DV.

Table 1. Police officer distribution by position and gender (adapted from Andrus Reference Andrus2020b:42).

Operationalizing narrative indexicality, the police officers use various linguistic forms to indicate understanding of the victim/survivor's behavior and situation, using the word ‘understand/ing’, and phrases such as ‘I/We get it/that’ or ‘I/We can see it/that’ to indicate their comprehension of and empathy toward victim/survivors. There were thirty-two instances of police officers expressing ‘understanding’, using one of the aforementioned constructions (see Table 2), with ‘I get it’, being the most used form.

Table 2. ‘Understanding’ phrases.

While one officer in particular showed empathy for victim/survivors, they all mitigated understanding with a critique of victim/survivors, typically for their inability to leave a violent relationship on the police officer's timeline. In most of the narrative fragments, ‘frustration’ mitigates the understanding a police officer might show toward a victim/survivor. In such stories, police officers open with understanding in a very brief clause or sentence, but then quickly move to more extended stories about ‘frustration’: for example, “I get that, but this is to the point where we've been here a couple times now, and ‘Go your separate ways’” (Officer McQuaid); “I get that. At the same time, there's a lot of denial going on” (Officer Love). There are twenty-three instances of police officers mitigating understanding with language that directly and/or indirectly indexed frustration.

A quick word about the discussion of demographic categories in the interviews with police. In the interviews with police, they sometimes mentioned gender in their stories about frustration and victim/survivors. Police officers mentioned gender explicitly only when they chose pronouns to represent victim/survivors and/or abusers. For example, Detective Sidwell uses pronouns representing both genders to represent abusers. He said, “Yeah, some victims just want us to make him be nice, or her be nice. They want us to end whatever situation they’re in”. Tyler, too, uses alternating pronouns in the context of abusers: “I've had ones where guys have, or girls have, or either party has assaulted the other one, and it's been going on for years—spousal sexual assault—just everything”. Acknowledging both pronouns is most common in representations of abusers rather than victim/survivors. That is, the police appear to find that men and women can be abusers, but they are less convinced that men can be victims. Therefore, gender came up a number of times. By contrast, though the racial and ethnic profiles of DV incidents in the western city match national demographics, it is impossible to say that police officers were indexing race or ethnicity when they talked about victims or abusers. Though bias is likely to be present in police discourse, in this data, there is no discussion of skin color, accented English, foreign language usage, need for a translator, or the like.

POLICING DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Discussions about DV often occurred in the context of recounting protocol. In extract (1), Officer McQuaid tells a hypothetical story about the process he goes through to ‘get the facts’.

(1) Officer McQuaid

1 It's a violent domestic.

2 You get there,

3 “What's the violence?”

4 “He's calling me names.”

5 “Did he threaten you?”

6 “No, he's calling me names.”

7 “Okay. It's not violent. It's mean and mean-spirited.

8 That's not very nice, but him telling you you're no good is not a criminal offense.”

The flat affect of getting the facts straight and the inability of police officers to do anything but arrest can lead to a showing of a lack of emotion. Often the emotion that is un/expressed when a police officer is ‘fact-finding’ works counter to the goals of the victim/survivors (Martin Reference Martin1999:119). Victim/survivors notice the ‘just the facts’ stance. As Violet put it, “to be honest, I felt like it was just any other, just random situation. … They had a protocol to follow. They were just doing their job, and that was it”. Violet recognizes that the officers helping her after her violent domestic attack were just going through the policy-motions, not caring particularly about her experiences or trauma. Trinch (Reference Trinch2001) argues that experience is translated into a matter of routine by institutions like law enforcement which tend to totalize and leave little room for full-fledged subjectivity and agency.

Police officers do occasionally express a sense of understanding for the plight of the victim/survivors. For example, Detective Tyler explains elsewhere in his interview that he had previously been married to a woman who had been in an abusive relationship earlier in her life. In extract (2), Tyler shows understanding for the circumstances of DV victim/survivors—perhaps related to his prior experiences—which he situates against a backdrop of a ‘typical’ police officer response to victim/survivor behavior.

(2) Detective Tyler

1 You hear it all of,

2 “Well, we've been over there so many times.”

3 “We've offered her help so many times.”

4 “We've hand-held so many times and it doesn't do anything so, obviously.”

5 “I'm tired of trying to help.”

6 I think that the officer needs to—

7 I guess I understand why he or she feels that way, and

8 I also understand the other half too.

9 I think that an officer needs to be more understanding and say,

10 “Look, until you're walking a mile in their shoes.”

11 It may seem outrageous to stay with somebody who is treating you the way

12 that they're treating you

13 but they're made to believe that the other person has got all this power and, most likely,

14 they make all the money.

15 They got kids.

16 They got this house.

17 They're giving up—

18 or they're thinking they're gonna lose everything.

19 How are we gonna protect her from that—protect them from that?

Tyler uses the language of understanding to show empathy for both police officers and victim/survivors. He speaks for the typical officer conception of a victim/survivor through direct quotation in lines 2–5. According to Tyler, it is frustrating to return to the same house for domestic calls without seeing the victim/survivor taking steps to leave. Other officers—not him—might become “tired of trying to help” (line 5). Tyler then presents the stance that is his own, one in which he is “more understanding” (line 9). In the second half of extract (2), however, he takes a position that accounts for the emotional, psychological, and socioeconomic reasons a person might stay in an abusive relationship, demonstrating understanding for victim/survivors’ lives and experiences. In leaving, the victim/survivor is “going to lose everything” (line 18), he asserts, how will police officers “protect them from that” (line 19). That is, police officers should be understanding because they cannot protect victim/survivors from socioeconomic and other emotional forms of abuse.

Tyler takes a position in which he shows understanding for victim/survivors, attempting to understand their thought processes and social constraints. He is the only officer who, in this one moment of his interview, narrates the indexical police ‘understanding’ without immediately mitigating it (though he does show frustration elsewhere in his interview). Many others make a gesture toward understanding, but that gesture is always mitigated with a story about frustration. As ways of expressing empathy or sympathy, police officers use the verbs ‘to understand’, ‘to get’, and ‘to see’, most frequently using ‘to get’, as in ‘I get it’. Oftentimes, the indexical structure changes from the singular first-person pronoun ‘I’ in ‘I get it’ to the plural first-person ‘We’ in ‘We get it’. These discursive moves index a narrative about caring that is operationalized by others in the group.

An example of ‘frustration’ is found in Officer Taylor's narrative in extract (3).

(3) Officer Taylor

1 I don't get frustrated, necessarily, going there,

2 but every time you go, you hope that this is the time they're like,

3 “Okay. Let's do this.

4 “I'll cooperate. Do what I need to do. I'll get the help I need.

5 “I'll leave. I'll go somewhere safe,”

6 but— … Yeah.

7 I have yet to see it.

Taylor begins her narrative with the promise of empathy—she doesn't get frustrated when she returns to the same household more than once for domestic calls. However, her expression of empathy is cut short by her use of the word “necessarily” (line 1). Though Taylor opens by saying that she doesn't get frustrated, she ultimately shows frustration with victim/survivors who don't cooperate with police goals (lines 4–5). She says that each time she visits a particular household, she hopes this will be the time the victim/survivor will say “Okay. Let's do this. I'll cooperate” (lines 3–4). In this narrative, Taylor is equating cooperation with leaving the abusive situation: “I'll cooperate. Do what I need to do. I'll get the help I need. I'll leave. I'll go somewhere safe” (lines 4–5). Taylor's final expression of frustration is found in the final line. In all her time as a police officer, she has “yet to see” a victim/survivor cooperate and leave the abusive situation on the schedule of the police officer (line 7). This phrasing highlights what, for her, is the source of frustration—the victim/survivor.

Taylor, like her peers, is frustrated by intractable victim/survivors not by recidivist abusers. The frustration lies with the victim/survivor rather than the abuser. This statement not only highlights the source of frustration for Taylor, but solidifies the idea in police discourse that victim/survivors are recalcitrant because they don't leave when the officer thinks they should. While other officers go so far as to say the victim/survivors are “stupid” when they call the police multiple times for the same issue (Officer McQuaid), Taylor merely comments on the victim/survivors’ cooperation. The result, however, is the same. Through narrative indexicality, the police view that domestic calls and victim/survivors are frustrating is developed and made replicable in police discourse.

MITIGATED UNDERSTANDING AND FRUSTRATION

While some police officers spoke nearly entirely in terms of frustration, most used the indexical construction, mitigated understanding. First, the police officer would position themselves as understanding, using mitigation discourses that soften the frustration narrative that inevitably follows. Even though most officers make a discursive gesture to understand victim/survivors, some can't even do that. In that discursive situation, only frustration is narrated. For example, Sergeant Roberts said, “Speaking of victims, I don't understand why they don't get out of it”. He is befuddled by the reasons a person might stay in a violent relationship, misunderstanding family and socioeconomic factors, and perhaps being unaware of statistics regarding abuse after separation. (About ‘three quarters of abuse victims are still abused after leaving (Berry Reference Berry2000)’ (Andrus Reference Andrus2020b:13).)

Detective Jacobs uses narrative indexicality when he shows frustration with a victim/survivor who didn't want to see her abuser go to jail. “In a sense, it was pretty frustrating, because I've got someone here who's basically crying on the phone and begging me to help her, but doesn't like the way that that help's gonna be given, because she doesn't want him in jail”. Because they are in the business of arrest, at least in part, police officers find the desire of the victim/survivor for her abuser to stay out of jail frustrating. It frustrates their work both literally and figuratively. Not only does Jacobs use intensifiers such as “begging” to misunderstand the emotional inner-workings of DV, he is also disappointed that the victim/survivor is stopping him from doing his job.

We see narrative indexicality linked to mitigated understanding in extract (4)—a story told by Detective Sidwell about a hypothetical DV situation. Sidwell was interviewed with three other DV detectives: Detective Jacobs, Detective Michaels, and Detective Johnson.

(4) Detective Sidwell

1 And we get that.

2 They felt a bad moment, whatever,

3 alcohol, something involved, high emotion, stressful situation.

4 In someone's head, they still love each other.

5 And a lot of them will work beyond that and

6 live happily ever after, and

7 we hope so.

8 There are also the ugly situations that it's like,

9 why did you get him from jail again.

10 You know, and that's where it goes back to—and

11 you hate to have this feeling.

12 And again, we try to do everything right

13 based on policy and procedure and state law,

14 but it's like, don't call me if you don't want us to do something.

15 But on the other hand, that doesn't really help the situation.

16 And so, being human, officers sometimes get that feeling, and

17 it's horrible to say,

18 but it can be super frustrating

19 when you're trying to help somebody, and

20 they continue to shun you away, and

21 bring the problem back that you then have to deal with again.

22 Because domestic violences are very dangerous.

23 And, you know, we don't know if we're going into an ambush or

24 going to a problem and that they're super emotional.

25 They're—they're an ugly case to have to respond on,

26 especially blind.

27 Going into it and

28 not knowing what you're—what's really goin’ on.

In extract (4), Sidwell starts off with “we get that”, which shows a modicum of understanding. What Sidwell “gets” or understands is complicated. He gets that some relationships are loving (while also violent), and he gets that people stay in such violent relationships. However, he finds such behavior frustrating. He narratively constructs indexical frustration using two discursive strategies (the repetition of be + like and sarcasm) in the two stories that he tells. The first story is introduced with a thin and quickly contradicted statement, “We get that” (line 1). The first story presumes a loving outcome: “they still love each other. And a lot of them will work beyond that and live happily ever after” (lines 4–6). This idea, however, is undermined by the word “whatever” on line 2. ‘Whatever’ can mean ‘in any case or anything’, or it can mean something dismissive and sarcastic like ‘this is not important’. We suggest that in this case both function via sarcasm, making excuses for the abuser in a DV situation with claims that the relationship will become loving and “happily ever after” (lines 6), while also disbelieving in that outcome, “whatever”. Understanding, then, is both ratified and questioned in the same brief, sarcastic, story. This story, then, mitigates understanding while acting on the surface as though it is reinforcing understanding. That is, this story does indexical work, but the social meaning that is linked to “whatever” presents a loving relationship as a possible outcome of a domestic call while undermining and problematizing that outcome.

In the second story, which starts on line 8, Sidwell indexes frustration with victim/survivor behavior in ‘be like’ (and be + excuse language) constructions (Ferrara & Bell Reference Ferrara and Bell1995; Romaine & Lange Reference Romaine and Lange1995; Dailey-O'Cain Reference Dailey-O'Cain2000; Macaulay Reference Macaulay2001; Cukor-Avila Reference Cukor-Avila2002; Tagliamonte & D'Arcy Reference Tagliamonte and D'Arcy2004; D'Arcy Reference D'Arcy2007) and repetition. Sidwell opens this story in lines 8–9 by saying, “There are also the ugly situations that it's like, why did you get him from jail again”. This is an open critique of generalized victim/survivor behavior, “ugly situations”. The “ugly situations” are those in which victim/survivors do not follow the logic of police officers and “get him from jail”. The ‘be like’ construction, “it's like”, is a quotative, indicating that the storyteller said this or something like this in a previous conversation. But importantly, the speaker doesn't say “I was like”, introducing his own words or ideas, but rather it is constructed as “it's like”, which makes the statement somewhat more general. It is as though all or any police officer might have had this memory or made this statement. This move to claiming space for all police officers is a common feature of police discourse (Andrus Reference Andrus2020b), in which all police behavior and ideas are presented as seamlessly the same.

The ‘be like’ construction is also used on line 14, when Sidwell says, “but it's like, don't call me if you don't want us to do something”. Here the general police officer quotative constructed with ‘it + be + like’, is used to indicate frustration with those victim/survivors who don't make decisions the ways that the police would prefer. Again, the use of ‘it’ indicates a general frustration that may be owned by the speaker but that is shared with police in general. This feeling of frustration is reinforced and made explicit in lines 17–21, when Sidwell says, “it's horrible to say, but it can be super frustrating when you're trying to help somebody, and they continue to shun you away, and bring the problem back that you then have to deal with again”. Here Sidwell uses an ‘it + be’ construction without the ‘like’. The quotative value of this construction is indicated by the use of the word “say” on line 17: “it's horrible to say”. The ideas that are horrible to say have to do with victim/survivors, but only in minimal ways. The real focus of this statement is police officers and their supposed treatment by victim/survivors who don't take their advice, push them away, and make their jobs hard. The frustration construction here is clearly with victim/survivors—not the abuser and not the situation. Thus, the person who makes the situation ugly is not the abuser, or not the abuser alone, but the victim/survivor who is here situated as a party to their own abuse. This indexical construction of frustration is particularly problematic in that it connects the victim/survivor to their own abuse.

In Sidwell's narrative, ‘be like’ is used narratively to create a sense of group identity, group discourse, and group opinion about victim/survivors. It also creates a relationship between victim/survivors and the police. As a feature of this narrative, ‘be/it/like’ functions narratively to help the interlocutor understand not just what happened, but how to understand what happened. In extract (3), above, ‘be like’ is also used by Taylor, who used it to create imagined, generalized dialogue with a typical/typified victim/survivor. She said, “They're like, ‘Okay. Let's do this. I'll cooperate. Do what I need to do. I'll get the help I need. I'll leave. I'll go somewhere safe,’ but— … Yeah. I have yet to see it” (lines 2–7). Here, ‘are like’ uses the quotative to introduce a set of hypothetical statements, working to create a relationship between police and victim/survivor. Using the quotative construction, Taylor presents herself as knowing what the typical victim/survivor is going to say, and she judges the victim/survivor for it. For Taylor, this mini dialogue indexes frustration, indicated by the editorial “I have yet to see it” statement that follows up the typified victim/survivor language. For both Sidwell and Taylor, this discursive construction, ‘be + like’, works through narrative indexicality to link frustration with the social meaning of DV and victim/survivors. This excerpt shows frustration over understanding; it shows very little understanding.

Though the present article is not about ‘be like’ as a sociolinguistic variable as much as a feature of narrative, it is interesting to note that though the ‘be like’ construction is more commonly associated with speakers presenting as female, in this case it was used repetitively by both men and women presenting speakers. As Durham and colleagues (Reference Durham, Haddican, Zweig, Johnson, Baker, Cockeram, Danks and Tyler2012:319) note, ‘the further be like diffuses, “the more likely it is to differentiate male and female speech” (Tagliamonte & Hudson Reference Tagliamonte, D'Arcy and Hudson1999:167)’. That is, the more ‘be like’ is used, the more likely it will be that all genders of speakers use it.

Narrative indexicality around frustration in extract (4) continues to be developed and deployed beginning on line 11. Following this short discussion of victim/survivor behavior is a statement of frustration that coordinates with the “whatever” from line 2 to mitigate any understanding that may have been implied in the opening, “We get that”. In lines 11–14 Sidwell says, “you hate to have this feeling. And again, we try to do everything right based on policy and procedure and state laws, but it's like, don't call me if you don't want us to do something”. Again, understanding is presented with a statement that Sidwell wishes he didn't feel the way he does, but that understanding is immediately mitigated in the admission that he does feel frustrated. This discussion of feelings is further complicated with a narration of procedure and policy, which works to disclaim any personal action, after which he expresses frustration—“don't call me if you don't want us to do something”. This is a message directly to the victim/survivor: don't call the police if you don't want them to do their job—make an arrest.

Once Sidwell starts down this path toward frustration, he doesn't stop. Frustration is produced in an indexical cascade. Though he recognizes that he should not feel this way, “it's horrible to say” (line 17), these feelings of frustration are “human” (line 16), and therefore natural, normal, and within the cultural status quo. This narrative creates an indexical link between naturalized, social behavior and police feelings of frustration with regard to victim/survivors. Thus, Sidwell ultimately claims that working with victim/survivors can be “super frustrating” (line 18), because victim/survivors don't take the help of police officers in precisely the way the help is being offered, by “shun[ing]” police help away. Through the construction and recapitulation of indexical narrative around police response to DV, victim/survivors are framed as pushing police help away, even in a story that misunderstands and is negative toward victim/survivors.

Sidwell's stories are examples of narrative indexicality. It is the formation of a dance between understanding and frustration that ultimately constructs and reinforces the indexicality of frustration in the context of DV and the framing of victim/survivors as difficult to work with—even recalcitrant. In these stories, victim/survivors and their behavior are positioned as frustrating, while police officers position themselves as just doing their jobs. This establishes an indexical dichotomy between rule-following police officers and frustrating victim/survivors. Once established in narrative, these indexicals and their dichotomous relationship are available for use by other members of the police force. They are available as police discourse where they benefit police officers but hurt victim/survivors.

In extract (5), Officer Taylor's identity emerges indexically via the performance of ‘frustration’ and ‘mitigated understanding’.

(5) Officer Taylor

1 It's frustrating.

2 I try to understand.

3 I haven't been in a situation

4 like that myself, so I can't fully put myself in a position like that.

5 Yeah. It's frustrating to me

6 because I want them to be able to take care of themselves and be safe, and

7 obviously they're not

8 if they're calling every other day.

Taylor begins her story with an expression of frustration, “It's frustrating” (line 1), a sentiment that is woven throughout the entire narrative, ending with a comment on frustration with victim/survivors who call the police “every other day” (line 9). The narrative indexicality in Taylor's frustration is complex. At first, the expression of frustration is due to her inability to fully understand the victim/survior's situation even though she claims to attempt to understand, “I try to understand” (line 2). Then her frustration morphs into a common complaint by police officers that victim/survivors hinder their work (see extract (3) above).

Encased in narrative language, understanding functions as a pre- and post-amble for Taylor's frustration, as seen in her concern for victim/survivor wellbeing, “I want them to be able to take care of themselves and be safe” (line 7). This is a performance of the ‘understanding’ indexical. As we see across these data, however, this concern for victim/survivors is soon negated, giving way to the indexical performance of frustration: “obviously they're not [taking care of themselves] if they're calling every other day” (lines 8–9). Here, Taylor is saying that in order for victim/survivors to be self-sufficient and safe they need to stop repeatedly relying on help from police officers, disregarding the fact that it is the job of the police to protect the citizens and community. Her use of the adverb “obviously” (line 8) is interesting because it implies that it is discernible—common knowledge—that victim/survivors are not being safe or self-sufficient when they stay in abusive relationships and repeatedly call the police for help. Moreover, using “obviously” diminishes the past experience and knowledge gained by the victim/survivor to know when a relatively safe time to leave the abusive situation would be. Taylor dismisses the knowledge of victim/survivors, narrating an indexical construction of frustration and judgment that runs through police discourse. That is, in the narrative indexicality created in this story, the performance of the indexical understanding is so thoroughly mitigated that it is as though it never existed.

In Taylor's narrative, pronouns—her use of first-person, ‘I’ and object case ‘me’—not only participate in the lack of empathetic narrative indexicality, but also make the fact that these victim/survivors won't leave their abusive partners personal to police officers. This is demonstrated by a particular use of ‘me’, as if the victim/survivor's behavior is directed against police officers and police work. Throughout this short narrative, there are seven instances of first-person pronoun ‘I’ usage. In her first justification for not being able to understand a domestic situation, Taylor says, “I haven't been in a situation like that myself, so I can't fully put myself in a position like that” (lines 3–5). Using “I”, Taylor inserts herself into the DV situation, and then immediately puts existential distance between herself and the victim/survivor of DV—the person who calls the police for help. This calls attention to the performance of her identity as being other than or not a victim/survivor. “I” have never been in this situation. Thus, because she is not a victim/survivor of DV, she cannot understand DV or victim/survivor reasoning.

Lines 5 and 6 combine to narrate an explicit lack of sympathy. They read, “so I can't fully put myself in a position like that. Yeah. It's frustrating to me”. Line 5 is very agented, talking about what Taylor cannot do: she cannot put herself in the position of being abused or the position of a victim/survivor. The “yeah” in line 6 works like an indexical connector, situating “It's frustrating to me”, as the result of a situation in which the officer cannot put herself. This frustration is opened up with an “it” without a clear antecedent. We posit that “it” gestures back to the DV situation referenced in line 3, and that it gestures forward, to lines 7–9, where she says, “because I want them to be able to take care of themselves and be safe, and obviously they're not if they're calling every other day”. These lines indexically link the idea of frustration with the victim/survivors not being able to take care of themselves, which is indicated by the fact that they call the police “every other day”. Thus, the thing that is frustrating is the context of DV, the victim/survivors, and the fact that they frequently call for help, not Taylor's inability to understand victim/survivors. To put it another way, Taylor is not frustrated with her own inability to be empathetic. She is frustrated that she has to spend so much time on these types of calls.

Taylor's story is another example of a police officer's narrative indexicality of frustration via mitigated understanding. Victim/survivors are discussed in terms of frustration—they call the police too much. Taylor's lack of empathy for victim/survivors is quite final. Because her identity is constructed as being other than a victim/survivor, she claims she cannot understand the victim/survivor's reasoning, and she claims so without hedging. In this way, this narrative work creates and maintains police discourse, while making frustration available for future use.

Detective Jacobs does significant work in extracts (6) and (7) creating and operationalizing indexical frustration through storytelling. He tells stories about victim/survivors that situate them as both the receiver of understanding and the creator of frustration. In extract (6), Jacobs is telling a story about a woman who is harboring her abusive intimate partner. When police arrive at her house, they see him through the door, only to have the victim/survivor lie and “play him off as being somebody else”. In this story, the victim/survivor acts as though the abusive partner, who the police were there to arrest (for a separate crime), was not at home, and instead, asserts that the man they had seen was not the correct man. Extract (6) picks up at this point.

(6) Detective Jacobs

1 I lost all my compassion, really, for her.

2 I just got to be real stern with her.

3 I said, “Look, don't give me this crap anymore”, type attitude.

4 “I know it's him, and all that.”

5 She didn't want me to take him to jail or not.

6 I said, “Sorry, you don't get that choice.”

The first line in extract (6), “I lost all my compassion, really, for her”, indicates both understanding and the mitigation of that understanding. The fact that compassion was lost shows that at one point the detective had compassion for her or for victim/survivors, in general. The result is indexical frustration that is both avuncular and policing. Because he lost compassion, he “got to be real stern” (line 2). At this point in the story, Jacobs moves into his police officer voice. Rather than using a ‘be + like’ quotative, Jacobs opts for an ‘I said’ quotative construction. This direct quotation style demonstrates ownership over the statement that follows. In line 3, Jacobs represents himself as saying, “Look, don't give me this crap anymore”. This statement performs frustration indexicality that is linked to and results from constraints on proper police procedure and work created by the victim/survivor's behavior. The final self-quotation is “Sorry, you don't get that choice”, said in response to the hypothetical victim/survivor's desire to keep her abusive partner out of jail. This statement entextualizes police work within the indexical frustration with victim/survivors.

One of the ways that indexicality functions in these data is through intensifiers. Intensifiers, amplifiers, or hedges work throughout the police discourse, indicating ‘the attitudes of the speaker or writer’ (Xiao & Tao Reference Xiao and Tao2007:242). Intensifiers are ‘linguistic devices that boost the meaning of a property upwards from an assumed norm’ (Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, & Svartvik Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:590). The intensifiers found throughout the data index frustration of police officers regarding victim/survivors’ actions, creating a sense of urgency and need to respond. The inability to satisfyingly respond and the repeated nature of victim/survivors’ inability to do what police officers wish lead to heightened emotions, indicated through intensifiers. In extract (6), Jacobs says “I lost all my compassion, really, for her. I just got to be real stern with her. I said, ‘Look, don't give me this crap anymore’, type attitude” (lines 1–3). Here, he uses “all”, “really”, and “real” to amplify his frustration with the victim/survivor, punctuated by “don't give me this crap”, which indicates heightened emotion—frustration. He had to become “real stern” when he lost “all [his] compassion”. Through his use of amplifiers, Jacobs places the blame for his actions—his need to become very stern—toward the victim/survivor.

Jacobs is not alone in his use of intensifiers, which result in victim blaming. In extract (2), Tyler uses intensifiers alongside repetition, saying, “so many” three times in as many sentences. Officers physically go to the same address, offer help, “hand-hold”, and are turned away by victim/survivors “so many” times. Tyler says “Well, we've been over there so many times. We've offered her help so many times. We've hand-held so many times and it doesn't do anything so, obviously. I'm tired of trying to help” (lines 2–5). The intensifier-repetition construction is completed with the statement “I'm tired of trying to help”, which indicates heightened emotion and tells the interlocutor how to understand the short narrative. Intensifiers can point to the ways in which police officers talk about and position victim/survivors in their narratives. These intensifiers highlight and link frustration to victim/survivors.

In extract (7), Jacobs begins by vacillating between understanding and frustration.

(7) Detective Jacobs

1 It's kind of the boy who cried wolf.

2 We try to be sensitive to not be jaded to that kind of thing,

3 but when you go and go, and go, and go, and go, and

4 you find out that you're being used to manipulate,

5 now who's the victim?

6 That can be difficult to keep an open mind about.

7 Look, I'm gonna find the evidence of a crime, and

8 that's what I'm gonna act on, and

9 try to take the emotion and the frustration out of it.

Line 1 indicates frustration. “It's kind of a boy who cried wolf” references a story in which a little boy said there is a bad wolf when there was not one. When a bad wolf ultimately arrives, nobody believes him. This statement indexically relates this well-known fairytale to DV and victim/survivors. The narrative presumes that the victim/survivor is calling the police and then refusing to leave the relationship, making it hard for police officers to have compassion for victim/survivors and return the next time they are called. The officer is frustrated that when he arrives on scene, there is no “wolf”. Indexical frustration is reinforced in the lines 2 and 3, which read, “We try to be sensitive to not be jaded to that kind of thing. But when you go and go, and go, and go, and”. That is, when a victim/survivor repeatedly calls for police help without leaving their abuser, police officers stop being “sensitive” to the needs of that particular victim/survivor. “Now who's the victim?” Jacobs exclaims. In a shocking turn of the tables, this statement claims that the result of a victim/survivor needing help multiple times is the victimization of police.

Though the police try hard to “keep an open mind” (line 6), victim/survivor behavior makes that difficult; it frustrates police procedure and policy. It is, after all, policy and procedure to “try to take the emotion and frustration out of it” (line 9). That is, Jacobs recognizes that these situations are frustrating, and in so doing, he indexes policy that recognizes that such situations are frustrating and instructs police to not get frustrated. The entextualized indexical frustration is therefore linked to police policy and is embedded in broader police discourses about DV and victim/survivors. At the same time, police present themselves as understanding, only to quickly move away from that positionality into a more judgmental description of frustration. All of this happens in narrative. Narrative is the location where frustration is performed indexically—linking ideology and social context to narrative form.

DISCUSSION

Stories about DV are constructed, performed, and used as indexical forms that link frustration with victim/survivors. Narrations of frustration are presented as a norm with regard to DV. According to Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2005:172), indexicality is made up of ‘stratified patterns of social meanings often called “norms” or “rules”’. That is, indexicality creates, responds to, and maintains socially meaningful alignments that make sense to those who use the linguistic forms associated with those meanings and alignments.

Taken together, the extracts analyzed above function indexically, linking held assumptions and values in the larger police community with specific stories about policing and victim/survivors. That is, these stories do indexical work by linking social values, social contexts, ideological frameworks with linguistic forms, narratives, about (i) police work and (ii) police frustration with victims/survivors. Narrative indexicality of this sort links context to social values. The way the police officers tell stories about victim/survivors—linking a hypothetical, any-person, with the real person who the story is ostensibly about—identifies at least one way that the police feel about victim/survivors. The fact that they expect the interviewer to agree with them, a fact established by the tone and form of their narratives, anticipates that everybody feels the same way. This is the establishment of narrative indexicality—the establishment and circulation of social meaning, values, and stratifications through storytelling.

Police officers accessed and operationalized social ways of telling stories about DV and police work that find their own behavior clearly reasonable and the behavior of victim/survivors frustrating. This is to say that the indexical nature of police narratives implies that those who are listening to stories about police work will recognize and positively respond to the relationship between understanding and the mitigation thereof—frustration. In short, these stories presume that frustration will make sociocultural and contextual sense, or at least that the speaker presumes that they will make sense for their interlocutor/s. These stories make presumptions about victim/survivors’ reasons for not leaving at the point at which police and others think they should, and they indicate that the storyteller feels frustration about victim/survivors’ leaving decisions. These stories indicate that when police officers narrate DV, they find frustration at every turn, in ample amounts.

CONCLUSIONS

The indexical constructions used by the police occur in storytelling. Both narrative and indexicality connect the speaker with the audience, working to find common ground and social meaning. Narratives are contextual, situated in a sociocultural set of discourses in which they function indexically. Stories point at social discourses about DV and about police work. They also point at some past event of police working in the context of DV. Narrative connects a story with an assumed, shared, social meaning and the specific words and features of a story. In the context of this article, that means that in bringing together multiple contexts, through multiple moments of indexicality, we can see an emergent social meaning of DV that is shared by police officers and perhaps even by society at large. In other words, in assuming that there is shared meaning between interlocutors, there is a presumption of shared prior discourses and shared ways of thinking that are indexed by a story. In short, norms are established, circulated, and maintained through narrative. This is the space of narrative indexicality—a discursive site in which social meanings are created, shared, and circulated through narrative. It is also the space of victim-blaming.

The frustration that emerges in stories about DV and victim/survivors is placed on the victim/survivors rather than on the abuser. Victim/survivors are blamed for not leaving violent relationships soon enough, in accordance with normative social/police logic, or on the police officers’ timelines. Rather than establishing any claim at all about the person perpetrating the abuse, it is the victim/survivor and their presumed inability to leave that is framed indexically through narrative as ‘frustrating’. At the same time, the police officers indexically frame themselves as understanding. What we have shown is that in police officers’ stories, understanding is mitigated with discourse that frames the victim/survivor as frustrating. This establishes the victim/survivor as frustrating and as party to their own abuse, while also constructing indexicality around police work; the police officer is just doing their job with empathy toward the victim/survivor. Most police officers frame the victim/survivor as readily able to leave the violent situation once police have intervened. If victim/survivors don't, they are seen as elements in their own abuse. Police work, by contrast, is narrated in terms of either non-emotional fact-finding or understanding. In either case, police are doing their jobs, which victim/survivors frustrate. Victim/survivors are thus frustrations, while police officers are simply doing their jobs.

The process of narratively situating the victim/survivor as frustrations to police work and frustrations to the victim/survivors’ own happiness is nothing short of victim-blaming. Indeed, victim-blaming is a norm that emerges in the narrative indexicality around DV both in police discourse and in the broader cultural norms and stratification in which the police are situated and to which they respond (Andrus Reference Andrus2020b). The police officers tell stories that coordinate with and reinforce social discourses about DV, namely that victim/survivors who don't leave their abusive situations on the external timelines of social norms and conventions are frustrating—frustrations to police work and frustrations to society. In this way, victim-blaming functions with amplitude in these stories, entextualized in police discourse and performed indexically in narratives about police work.