INTRODUCTION

Feminist scholars critiquing the neoliberal order that has come to characterize many wealthy, industrialized countries have argued that women are socially constructed as the ideal citizen (McRobbie Reference McRobbie2009; Gill & Scharff Reference Gill, Scharff, Gill and Scharff2011; Wilkes Reference Wilkes2015). Cultural discourses framing the importance of self-transformation and improvement, as well as self-regulation and control are aimed primarily at women, and it is women on whom cultural imperatives of self-discipline operate most acutely (Ouellette & Hay Reference Ouellette and Hay2008; Ringrose & Walkerdine Reference Ringrose and Walkerdine2008). As Gill & Scharff (Reference Gill, Scharff, Gill and Scharff2011:7) write, ‘To a much greater extent than men, women are required to work on and transform the self, to regulate every aspect of their conduct, and to present all their actions as freely chosen’. Within a larger capitalist milieu, the project of the regulated female body is, crucially, never complete, as the goal of ideal femininity is elusive and ever-changing. Of course, ideologies of gender are simultaneously bound up with race, class, and other identities that shape lived experience. Thus, we cannot discuss gender without attending to the ways that these other structures intersect and influence one another. Along these lines, scholars conscious of the dangers of ‘whitestream[ing] feminism’ (Grande Reference Grande2003) have given considerable attention to the ways in which ‘techniques of white femininity’ (Wilkes Reference Wilkes2021) work to reinscribe class-privileged white women as the neoliberal aspirational ideal.

A reigning contemporary example of the dominant reproduction of white femininity is the wellness industry, which promises ‘luminous good health and preternatural vitality’ (O'Neill Reference O'Neill2020:629). As part of a larger cultural preoccupation with makeover and self-transformation, the multibillion-dollar wellness industry is broadly recognized as having a target audience of primarily wealthy, white women (O'Neill Reference O'Neill2020; Wilkes Reference Wilkes2021), and promotes a wide range of products and practices purported to aid in the interminable project of self-improvement. The Goop franchise, founded by former actor Gwyneth Paltrow, is one of the most visible wellness companies in the US, and perhaps globally as well. Although the franchise has come under intense criticism and legal challenges based on unsubstantiated health claims, and potentially harmful products and advice,Footnote 1 the company continues to enjoy immense success, with a reported net worth of $250 million (Brodesser-Akner Reference Brodesser-Akner2018). Gwyneth Paltrow herself has been identified as ‘a key example of the embodiment of idealized whiteness’, in large part ‘because she is discursively placed in proximity to objects and values which are culturally judged to be good’ (Graefer Reference Graefer2014:110). As the face and name of Goop, her embodiment of idealized whiteness—which is also intertwined with gender and class—is a dominant motif of the franchise. A quick glance at goop.com reveals that the company features almost exclusively bodies that are similar to Paltrow's: white, thin, female, with ‘diversity’ represented as one dimension of difference away from this ideal (see Sastre Reference Sastre2014; Darwin & Miller Reference Darwin and Miller2021).

Goop represents an ideal cultural lens through which to view imperatives of white femininity and neoliberal discursive constructions of the body. I work here from the vantage point of an embodied sociolinguistics, with the understanding that ‘language is a primary means by which the body enters the sociocultural realm as a site of semiosis’ (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2016:173; see also Zimman & Hall Reference Zimman, Hall, Watt and Llamas2010). Along these lines, I ask here how the body is discursively constructed in the orbit of wellness, and in what ways the subject is impelled to act given the social meanings inscribed on the body within and across these cultural texts. In answering these questions, I probe a collection of articles from the Goop website, using techniques of corpus analysis paired with a critical discourse analytic approach. The discursive construction of the body at risk is shown to be ideologically linked to larger cultural discourses of discipline and control, and which are largely centered on the white female neoliberal citizen.

NEOLIBERAL CITIZENSHIP AND THE FEMALE BODY

Neoliberalism is traditionally understood through the lens of economics, in which policies are aimed at deregulating industry, privatizing institutions, and scaling back or eliminating programs of social welfare. Government intervention into the lives of private citizens is greatly reduced in all areas, as citizens are viewed as consumers whose freedom lies in their ability to make choices in the marketplace (Harvey Reference Harvey2005; Giroux Reference Giroux2008; see also Lazzarato Reference Lazzarato2009; Thurlow Reference Thurlow2020; Starr, Go, & Pak Reference Starr, Go and Pak2022). Here, I understand neoliberalism on a broader scale, as an ideology that permeates all areas of citizens’ lives in many industrialized societies. Neoliberal ideology has become a ‘hegemonic, quotidian sensibility’ (Gill & Kanai Reference Gill and Kanai2019:133), which impels individuals to make responsible decisions, to constantly work to improve themselves and their own social position, with no involvement or assistance from the state. Neoliberal ideology erases or ignores structural constraints, such as racism, classism, and the confines of patriarchy, pushing instead the narrative that freedom, mobility, and prosperity are granted to individuals who work hard and make the ‘right’ behavioral and consumerist choices, and who participate as rational actors in the capitalist market economy. Personal freedom and responsibility are valued far above the collective good, and those who do not succeed in the project of their well-being and happiness are blamed for their own failure.

The neoliberal regime urges individuals to practice discipline and control over the minutiae of their lives, to be hyper-aware that every decision is the right one, propelling them towards the goals of material and aesthetic success. In other words, individuals have great autonomy, but this comes alongside the ‘crushing responsibility to make the right life choices’ (Tulloch & Lupton Reference Tulloch and Lupton2003:3). Indeed, this neatly characterizes risk society, in which ‘unknown and unintended consequences come to be a dominant force’ (Beck Reference Beck and Ritter1992:22; see also Lupton Reference Lupton1999). In a risk society, much time and energy is spent looking towards the future, and is organized around potential risks and ways to ameliorate their effects. There is great concern placed on knowing about possible risks, so that the subject can make proper calculated decisions in order to reduce them. The societal outcomes of risk culture are keenly visible within a neoliberal hegemony, and the concomitant demand that individuals take full responsibility for their health and wellness, regardless of obstacles or structural barriers (Brown, Shoveller, Chabot, & LaMontagne Reference Brown, Shoveller, Chabot and LaMontagne2013; Brookes, Harvey, & Mullany Reference Brookes, Harvey and Mullany2016). This achieves the desired results of self-regulation and control, but operates stealthily within a discourse of empowerment and choice.

It is within this neoliberal risk society that we can clearly see the mechanisms by which the docile body is demanded and reproduced. From a Foucauldian perspective, the body is the primary site at which social control is enacted: ‘Discipline produces subjected and practiced bodies’, writes Foucault (Reference Foucault1977:138–39), ‘docile bodies’. It is not only through the gaze of others that discipline is actuated and ‘the body… is coerced into a normative discourse’ (Coupland & Gwyn Reference Coupland, Gwyn, Coupland and Gwyn2003:3), but crucially through self-scrutinizing gaze as well. Subjects have internalized the primary mechanism of social control—constant surveillance—and thus self-regulate in ways that conform to normative practices. Moreover, in a risk society, in which individuals are constantly on alert for potential danger, the discipline required for the production of docile bodies extends to ever-expanding areas in subjects’ lives.

Although all individuals in societies marked by neoliberal sensibilities are subject to its effects on their psychic and affective lives (Gill & Kanai Reference Gill and Kanai2019), much feminist scholarship has noted the ways in which the feminine subject is constructed as the ideal neoliberal citizen (McRobbie Reference McRobbie2009; Gill Reference Gill2016). And we must add to this: white, (upper) middle-class, able-bodied, thin, cisgender, heterosexual, for the ideal neoliberal citizen holds these intersections of privileged identities as well. It has been long recognized that discourses of the female body are rooted in racist ideologies, constructing white femininity as the ideal, both historically and at present (Thompson Reference Thompson2015; Strings Reference Strings2019). Moreover, there has been broad recognition of the close interconnectedness of neoliberalism and cultural discourses such as postfeminism and colorblindness, which insist that society has ‘moved past’ race and gender as social problems, thus ideologically—though crucially, not materially—leveling the playing field by ignoring structural constraints on individuals’ upward mobility, productivity, and institutional access (Giroux Reference Giroux2008; Mukherjee Reference Mukherjee2016; Scharff Reference Scharff2016). The ubiquitous representation of class-privileged white femininity as the aspirational ideal thus simultaneously reinscribes hegemonic patriarchy and white supremacist structures.

Previous feminist applications of Foucault to the subjugation of the female body have focused on the ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault Reference Foucault, Martin, Gutman and Hutton1988) that produce normative iterations of white femininity, particularly those having to do with weight and beauty (Bartky Reference Bartky, Diamond and Quinby1988; Bordo Reference Bordo, Jaggar and Bordo1989). In other research on the female body at risk, Weaver, Carter, & Stanko (Reference Weaver, Carter, Stanko, Allan, Adam and Carter2000) argue that the way media reports frame violence against women constructs the female body at risk, and as such engenders fear of public spaces among women. Tulloch & Tulloch (Reference Tulloch, Tulloch, Coupland and Gwyn2003:119) contend that discourses of crime in the media do not only lead to fear but simultaneously to a sense of outrage, and ‘a call to action’. Foregrounded by these studies are the cautionary practices white women in particular are urged to engage in to minimize their risk, whether that be risk of bodily harm or risk of falling short of a normative feminine ideal. For female subjects in particular, risk is indeed everywhere; reverberating throughout our cultural discourse is ‘a statistical nightmare of the female body’ (Woodward Reference Woodward, Coupland and Gwyn2003:234), and thus in constant need of disciplinary techniques for regulation and control.

In this article, I take these theoretical strands—neoliberal risk culture and the production of the docile white female body—as a point of departure for the interrogation of the discursive construction of the body in the wellness industry. The rise in the popularity and profitability of wellness over the last few decades can be interpreted through the desire for self-improvement; the world of wellness offers a broad swath of suggestions for improving virtually every aspect of the body and home, promising a path to utmost health and limitless happiness. Being unwell or unhappy signals only that the subject has not taken adequate steps to achieve wellness and happiness. The wellness industry, with its carefully curated regimens of health and individualized well-being for the privileged, has a primary female audience, as is the case with many other industries that prioritize self-improvement, transformation, and the never-ending quest for the optimal self (Cairns & Johnston Reference Cairns and Johnston2015; Elias, Gill, & Scharff Reference Elias, Gill and Scharff2017).

DATA AND METHODS: CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS AND CORPUS LINGUISTICS

I utilize here corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis, an approach that scholars have successfully applied to data from various media sources (Edwards & Milani Reference Edwards and Milani2014; Bednarek Reference Bednarek, Baker and McEnery2015; Baker & Levon Reference Baker and Levon2016), drawing together both quantitative and qualitative methods through which to examine linguistic data. The approach to discourse that I adopt starts from the position that texts encode relationships of power, as well as challenges to dominant structures (see e.g. Fairclough Reference Fairclough1989; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk2008; van Leeuwen Reference van Leeuwen2008; Wodak Reference Wodak2015). Such a critical discourse analysis (CDA) calls for both micro- and macro-analysis, tracing linguistic elements in the text to widely circulating discourses and their ideological effects. While CDA is a distinctly qualitative approach, sociolinguistic researchers in recent years have supported these analyses with quantitative measures from corpus linguistic methodologies. Corpus analysis not only provides a useful check on qualitative approaches, but it also allows researchers to examine the cumulative effects of discourse—to uncover how ideologies are circulated and reproduced, layered within and across texts, accruing over time (Baker Reference Baker2006; Levon, Milani, & Kitis Reference Levon, Milani and Kitis2017). Therefore, corpus linguistic analysis techniques are particularly well-suited for investigating language and embodiment because they allow for the analysis of large-scale, recurring patterns that construct bodies in particular ways (Motschenbacher Reference Motschenbacher2009; Milani Reference Milani2013; Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2016).

Goop regularly publishes articles in the wellness section of the website that are similar to content found in lifestyle ‘women's’ magazines, containing a mixture of information, opinion, and advice (see also Motschenbacher Reference Motschenbacher2009). While wellness is a broad category, it is most closely associated with food, supplements, and ‘clean eating’ (O'Neill Reference O'Neill2020). Indeed, Goop's origin story is centered on food and eating, from the newsletters with recipes that pushed the brand forward, to the detox cleanses that Goop became so well known for, to the bestselling cookbooks that Gwyneth Paltrow has written. I therefore focused on the Health and Detox subsections of Goop's wellness page, gathering all articles available in these two sections of the website in January 2021, yielding a corpus of just under one million words. Additionally, a reference corpus was built from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; Davies Reference Davies2008–), using the iWeb samples, which contained roughly 116 million words. Analysis was conducted in AntConc (Laurence Reference Laurence2020), a freely available software program for corpus analysis.

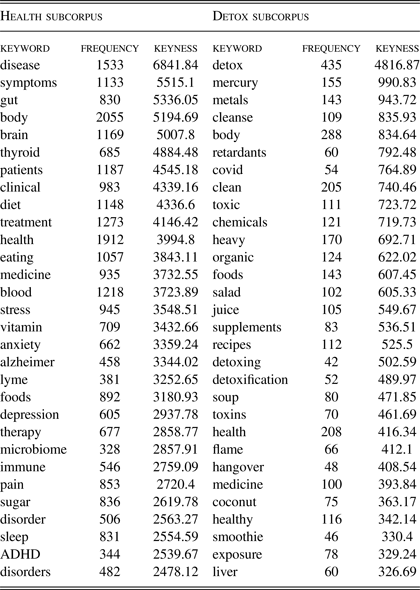

The reference corpus is included here for keyword analysis, a common technique applied as an entry point into the corpus under study. Keyword analysis is a statistical measure that shows frequency differences between the node and reference corpora (here, Goop and COCA, respectively). A measure of keyness indicates which words appear with more frequency in the target corpus when compared to the reference corpus, revealing ‘the basic contour of the ideological field’ (Levon et al. Reference Levon, Milani and Kitis2017:522). In other words, keyword analysis gives us a sense of the ‘aboutness’ of the corpus (also see Motschenbacher Reference Motschenbacher2020; Bogetić Reference Bogetić2021). Table 1 lists the top thirty content keywords for the Health and Detox subcorpora. I have excluded product/franchise names like Goop, and personal names like Gwyneth Paltrow/GP as well as function words, as they do not contain robust semantic information, and thus give little insight into the ideological composition of the corpus.

Table 1. Keywords in Health and Detox corpora.

The keyword analysis reveals several themes about these two subcorpora. In the Health subcorpus, it is particularly notable that disease and symptoms, both with negative, unhealthy meanings, top the list. Indeed, over half of the keywords in the list denote specific ailments (e.g. Alzheimer, depression), or have close semantic associations with disease and disorder (e.g. thyroid, treatment). Similarly, in the Detox subcorpus, over a third of the top keywords flag elements that are dangerous and harmful (e.g. chemicals, toxins, flame retardants). Taken together, these keyword lists already signal a distinct focus on bodily risk and harm.

While goop.com promotes the idea that ‘whole food is the cornerstone of health’, the ideological thrust of the corpus is one of poor health. What emerges from the keyword analysis are three major discursive themes threaded throughout the corpus: (i) harmful substances are everywhere, (ii) the larger environment is beyond individuals’ control, and (iii) good citizens must exert control over body, food, and home. I discuss each of these in turn below, before returning to a discussion of a larger cultural imperative of health, happiness, and the white feminine subject as the ultimate locus of these discourses of control.

NEOLIBERAL RISK AND FEAR: THE IMPERILED BODY

The body is constructed as ‘at risk’ by environmental factors such as elements in the food supply and airborne substances, as well as by lifestyle choices. Mercury, second in keyness within the Detox subcorpus, is a prime example of the way in which Goop constructs the body at risk. In the examples below, mercury is one of several heavy metals highlighted as a major cause of unwellness:

(1) Mercury and lead are especially potent neurotoxins, which interfere with neuron function and increase oxidative stress. Heavy metals cause damage on a cellular level, leading to potentially long lasting and irreversible effects. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/what-to-know-about-heavy-metals/)

(2) Heavy metal toxicity from metals such as mercury, aluminum, copper, cadmium, nickel, arsenic, and lead represents one of the greatest threats to our health and well being. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/a-heavy-metal-detox/)

(3) While all toxic heavy metals wreak havoc on the body, mercury is an especially insidious beast, responsible for untold suffering throughout human history… Mercury toxicity can be responsible for countless disorders and symptoms, including anxiety, ADHD, OCD, autism, bipolar disorder, neurological disorders, epilepsy, tingling, numbness, tics, twitches, spasms, hot flashes, heart palpitations, hair loss, brittle nails, weakness, memory loss, confusion, insomnia, loss of libido, fatigue, migraines, endocrine disorders, and depression. In fact, mercury poisoning is at the core of depression for a large percentage of people who suffer from it. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/a-heavy-metal-detox/)

In these examples, mercury is placed in a directly causal relationship with the afflictions named. Using unmodified, simple present tense verbs like is/are, interfere (with), cause, wreak (havoc), the articles presuppose an established link between the substance and risk to the body. While there is no evidence presented to support this straightforward causality, only rarely is it attenuated, as in (1) with potentially, but that concession is immediately counteracted by the permanence of the verb's complement, leading to… irreversible effects. Similarly, in (3), there are four instances of direct causality indicated by such relational constructions. The modal can is the only case in which this connection is weakened, but it is then followed by a list of no fewer than twenty-five ailments. Thus, even while can inserts a sense of suggestion, it is structurally overwhelmed by the itemized list. Paired with the observation that mercury is described with superlatives (greatest threats) and boosters (especially potent; especially insidious; untold suffering; countless disorders and symptoms), constructing a highly negative semantic profile around the word, these examples show that the conscious Goop reader is left with little room for uncertainty about the danger of the substance and the effects it has on the body.

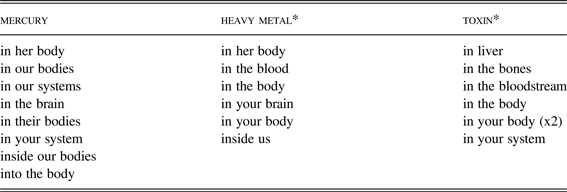

Mercury and other harmful substances are often located within the body itself. As Table 2 shows, the Goop corpus contains multiple examples of mercury followed by a prepositional phrase headed by in, into, or inside, locating this element directly within the body. The same trend is found with heavy metal(s) and toxin(s) as well.Footnote 2

Table 2. Prepositional phrases locating harmful substances in the body.

The body is thus constructed as a gathering site for harmful substances. Added to this is language that emphasizes the increasing presence of these substances, and the way that they collect within the body. Particularly prevalent, as seen in the examples below, is the notion of time as tied to risk: lifetime exposure, intergenerational transmission, and a sense of permanence unless action is taken.

(4) The majority of these common ailments are the direct result of toxin build up in our systems that has accumulated during the course of our daily lives. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/clean/)

(5) Thus, for optimal health, we need to eliminate not only the mercury we've accumulated in our own lifetime, but the mercury we inherited from our ancestors as well. Otherwise, as a human race we will become increasingly sensitive and intolerant to mercury and other heavy metals inside us. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/a-heavy-metal-detox/)

(6) Common toxic heavy metals, such as mercury, arsenic, lead, or cadmium, can accumulate in a person's body, causing them to get sick. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/what-to-know-about-heavy-metals/)

(7) Many flame retardants can persist in our bodies for years, and they can pass through the placenta from a mother to her growing fetus. These chemicals also accumulate in breast milk, further exposing the newborn to flame retardants (to clarify, although this fact is concerning, scientists agree that the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks posed by these chemicals). (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/flame-retardants-furniture/)

(8) Second, if we consume fatty foods, there is a good chance we will store more fat in our bodies. And guess what that means—more places for the fat loving chemicals to build up in. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/does-detoxing-really-work/)

(9) As long as there are heavy metals, chemicals, and/or radiation in your system, you are more susceptible to parasites and their eggs. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/you-probably-have-a-parasite-heres-what-to-do-about-it/)

In similar fashion to examples (1)–(3), the examples here present largely unmitigated assertions regarding the connection between these substances and the body: how they enter the body, how long they remain, and what effects they have. This relationship is presented as straightforward in (4), with no epistemic weakening of the claim. The definiteness of the NP the direct result not only emphasizes the causal relationship, but also points to toxin build up as the singular cause of these ailments. In (5), this is achieved through the deontic modality in need to eliminate, which presupposes that we have accumulated and have inherited mercury in our bodies. With no scientific evidence provided to support these ideas, the author proceeds to state an unequivocal claim about what will happen, with the modality again conveying the assuredness of this being borne out.

The verbs of accumulation (accumulate, build up, store) in these examples again bring into focus the importance of time, underscoring that the job of guarding against the risk is never complete. Harmful elements in the body are represented as not only present, but ever-increasing both over one's lifetime and across time more broadly, as inherited in (5). The ease with which harmful elements pass across generations is further underscored in (7), highlighting transmission through the placenta and breastmilk. Subjects are thus activated to both rid the body of substances that have unknowingly collected in the body over time, and also to prevent passing them on to more vulnerable bodies, viz. fetuses and newborn babies. The fear that drives action in this case centers on arguably one of the most protective subject positions, that of a parent caring for their child, and adds to the normative discourse of ‘ideal motherhood’ as being one in which mothers constantly make calculated decisions to parent in optimal, morally responsible ways, minimizing risk for their children at every turn (see Brookes et al. Reference Brookes, Harvey and Mullany2016). The discourse of neoliberal risk is cast into sharp relief in the parenthetical in (7), placing two potential risks in tension with one another (feeding your baby with breastmilk that has chemical traces, versus feeding your baby with formula). Every choice poses risk; the calculus of every decision is pressing and consequential.

Examples (8) and (9) also operate on fear, though towards more specific targets: fat bodies and parasites. The cultural discourse that views fat bodies—particularly fat female bodies—as abject and unworthy is a subject tackled by many feminist scholars (e.g. Bordo Reference Bordo1993; LeBesco Reference LeBesco2003). Here, fear of fat is centered not on appearance or others’ judgment, but on health and safety. The conditional if that introduces the agentive verb consume and its object fatty foods, widely understood to be unhealthy, sets up the reader as making an intentional poor choice. The underlying implication is that to make irresponsible choices is to put oneself at risk: if you have a body made fat by your irresponsible food choices, and you get sick from chemicals that have built up within it, then undesirable health outcomes are assured, and you are to blame. In (9), the focus is on the imperative to take action to eliminate existing harmful substances, again based on a discourse of fear. The link between harmful substances and the body at risk this time stems from invasive elements culturally understood as disgusting (parasites and their eggs), and especially the thought of their presence in the human body. The adverbial phrase as long as creates a sense of indefinite time (i.e. until you act), and underscores the causal link between foreign elements in the body: mercury, heavy metals, radiation as directly connected to parasites. It is the inaction in this case that assures the bodily affliction, and thus the reader is urged to rid the system of these substances in order to avoid parasitic invasion.

UNAVOIDABLE RISK: INESCAPABLE TOXICITY

If harmful substances such as mercury and chemicals are decidedly located within the body, how do they come to be there in the first place? This second discursive theme is tightly connected to the first. These elements that make the body unwell are found in our surroundings, and are largely unavoidable, posing an invisible, inescapable threat. It is this interaction between the body and the environment that drives action in the neoliberal pursuit of wellness: the body is constructed as at risk because of its very presence in the environment. This is a particularly clear illustration of Bucholtz & Hall's (Reference Bucholtz and Hall2016:186) observation that ‘the body is imbricated in complex arrangements that include nonhuman as well as human participants’. As such, an embodied sociolinguistics must pay attention to the way in which entities, such as the environment, do not ‘remain distinct from the bodies that deploy them but as participants that are complexly intertwined in the production of action, social meaning, and subjectivity’ (Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2016:187). The willingness and capacity for the subject to act in response to harmful substances, as urged by wellness discourse, emerges thus from the interaction of the body and the environment within which it operates. In the examples below, several strategies are employed that impart the idea that the environment is an entity that both puts the subject at risk, and which is beyond the subject's direct control.

(10) Mercury is an extremely toxic element and heavy metal that is increasingly affecting the health of millions of people. It's a major problem today because our exposure to it is rising, from the air we breathe to the food we eat. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/how-to-get-mercury-out-of-your-system/)

(11) Endocrine-disrupting chemicals are virtually everywhere these days—from inside our shampoo bottle to the lining of canned foods. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/infertility/)

(12) This entire response is compounded by the fact that free radical-generating substances are present all around us: in fried food, alcohol, tobacco smoke, pesticides, air pollutants, and even the sun's rays. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/earthing-how-walking-barefoot-could-cure-your-insomnia-more/)

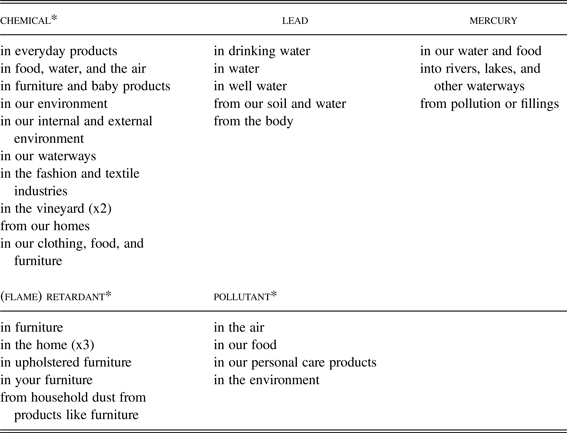

(13) But even municipal water can contain mercury and other heavy metals. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/how-to-get-mercury-out-of-your-system/)

Most striking in these examples is the way in which the environment is presented as teeming with elements that are cause for worry. In examples (4)–(9), the body was constructed as a vessel in which these harmful substances accumulate over time. In (10)–(13), this risk is further heightened because of the ubiquity of dangerous elements in the environment which the body inhabits. There is an emphasis on the threat these substances pose through intensifying modifiers (highly toxic; extremely toxic; major problem), and a focus on time, either in absolute terms (decades) or in relation to some previous time (increasingly affecting; exposure to it is rising; these days). Furthermore, no modals are present to weaken the epistemic claims of just how far-reaching these elements are. In (11) and (12) they are virtually everywhere and present all around us, while in (10) this exposure… is rising. (10) and (11) both contain the construction from NP to NP, linking together two unrelated groups of things. The coordination of the two heads in these phrases suggests a plethora of additional, unnamed items in between which bridge the gap; the example in (12) fills this gap by cataloging seven different elements that pose this risk to the body. In both (12) and (13), the lists end with the adverb even, setting up the following NP as unexpected: the sun's rays, firmly implanting the idea of inescapability, and municipal water, which readers in industrialized countries may presume to be safe and clean.Footnote 3 Table 3 provides additional examples from the corpus of harmful substances discursively placed in the environment through prepositional phrases (as opposed to within the body as in Table 2).

Table 3. Prepositional phrases locating harmful substances in the environment.

Collocation is a measure of which words in a corpus are statistically likely to occur together, beyond random chance. Collocates are an effective way of understanding the semantic prosody of lexical items in a corpus, revealing how associations between words are expressed in and across texts (Baker Reference Baker2006). Identifying these associations helps uncover the ideological aura around particular words, and can reveal ways in which authors express evaluations and otherwise infuse ideological meanings into the text at a localized level (Hunt Reference Hunt, Baker and McEnery2015; Levon et al. Reference Levon, Milani and Kitis2017). In the present analysis, these associations prove to be quite useful in further revealing how Goop constructs the body as unwell and the environment in which the body exists as dangerous. Collocations for several harmful substances recurring in the corpus are provided below in Table 4, using a span of five words to the right and left.

Table 4. Top lexical collocates of harmful substances in the environment, listed in order of decreasing p-value (log-likelihood).

Of particular note in Table 4, each word collocates with either exposure or exposed, and in several cases both word forms are collocates of the harmful substance. Additionally, the collocational patterns further reveal how Goop emphasizes the overwhelming number of harmful substances that the reader should pay attention to. Here, each of the elements collocates strongly with a diverse range of other harmful things, underscoring just how far these inescapable risks reach. Also of note is that the strongest collocate of toxin* is environmental. Traces of this strong pairing can be seen throughout the other columns as well, in the general terms exposed/exposure and everyday, as well as the lexical items that name specific sources of harm or risk (e.g. mold, smoke, air). Together, these observations again strengthen the notion that subjects are, without knowledge or consent, placing the body in constant contact with substances that have potentially detrimental effects on their well-being. The corpus does more, however, than simply establish that the environmental toxins that put the body at risk are inescapable. The texts also draw together harmful substances in the environment with a wide range of ailments and illnesses in a causal relationship, as in the examples below.

(14) In my book, The Adrenal Thyroid Revolution, I show how a multitude of seemingly unrelated symptoms share one source, what I call Survival Overdrive Syndrome (SOS), a condition that occurs when the body becomes overloaded by stress, poor diet, lack of sleep, toxic overload, and chronic viral infections that are inescapable in our world today. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/is-epstein-barr-virus-at-the-root-of-chronic-illness/)

(15) Ninety-eight percent of the time, cancer is caused by a virus and at least one type of toxin. There are many viruses that can be involved with cancer; the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is one of them. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/the-medical-medium-on-the-origins-of-thyroid-cancer/)

(16) Chronic low level metal toxicity is common, is underdiagnosed, and can lead to a myriad of vague symptoms, including chronic fatigue, depression, insomnia, skin, digestive disorders, and more. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/what-to-know-about-heavy-metals/)

(17) Your exposure to environmental toxins and your ability to detoxify your body also affect your genetic expression. Whether you know it or not, you are affecting your own genetics daily and perhaps even hourly through the foods you eat, the air you breathe, and even the thoughts you think. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/how-to-not-look-old-tired/)

Critical in these examples is that the symptoms and illnesses resulting from environmental toxins are nebulous and vague, alerting the subject to always be vigilant, always on the lookout for a hint of potential unwellness in the body. The choice of verbs again underlines the causal relationship presented between the body's exposure to harmful elements through the environment, and the risk that poses to the subject's well-being. As in previous examples, the epistemic modality is unattenuated (are inescapable, is caused by, affect, are affecting). In the one instance where this modality is lowered in (16), it is immediately followed by a long list of bodily afflictions, which effectively undoes any mitigation of can. Risk lurks everywhere, and harm may be indetectable; it is thus imperative to exert control over, for example, one's food, sleep, and thoughts, and determine ways to fix the condition. Interestingly, the only example here that imparts a sense of agency is (17), you are affecting your own genetics, which is attenuated by the preceding whether you know it or not. This places the reader as responsible for the demise of their genetic expression, though the subject is cast as doing so unknowingly, without intent. Now armed with this knowledge of the risk that is inherent to being in a body in the world, the responsible citizen must intervene and make choices that actively work to minimize that harm. Of course, the process is never complete since these ills are simply inescapable as in (14), making the project of individual transformation an ongoing endeavor, requiring constant vigilance around all aspects of life.

Keywords and collocates, paired with extended concordance lines have illuminated how the environment is constructed as a risk-filled, all-encompassing entity, with the body at the center of risk and harm, swept into the cyclical, unending process of self-surveillance that is a central tenet of neoliberal ideology. In the following section, I consider how these meanings are mobilized to activate the neoliberal subject to engage in self-regulating, transformative practices that lead to wellness. Additionally, it is through this wider-lens view of the corpus that exposes how the female body—in particular a white, class-privileged female body—is interpellated in the discourse of wellness. It is to this last discursive theme in the corpus to which I now turn.

ACHIEVING WELLNESS: THE GOOD CITIZEN EXERTS CONTROL

As discussed above, the underpinning of the neoliberal regime is the obligation of the individual to make the ‘right’ choices in order to succeed and thrive (Harvey Reference Harvey2005). As Ng (Reference Ng2019:134) puts it ‘the ideal self-interested neoliberal subject [will] transcend whatever constraints that may be present’ in order to attain success. In the world of wellness, this is urged through a combination of restriction and consumption, material practices which are both tightly linked to white, middle- and upper-class female subjects (Lupton Reference Lupton2018; Wilkes Reference Wilkes2021). To this end, Goop provides a virtual roadmap to wellness through suggested practices and products. Many of these revolve around food and eating—a trend already noticeable in the keyword analysis (Table 1), in which foods figure prominently. Recommendations center largely on these themes as well, including both foods to avoid, and foods that are purported to cure and heal. Goop articles suggest a range of restrictive practices for readers such as elimination diets and prescribed detox regimens, all of which are claimed (without robust scientific backing) to rid the body of harmful substances and cure ills, as in the examples below.

(18) We must turn this thinking around and adopt a detox lifestyle, where we are living in a healthy and reasonable way most of the time, so that we are constantly detoxing (because we are constantly exposed to unwanted chemicals). And save the binging for the bad stuff. Break down and have some yummy barbecue ribs and fries if you must. But make that the exception. Or maybe a cheese platter is your big weakness. As long as it isn't a daily cheese platter. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/does-detoxing-really-work/)

(19) In my experience, an eight day, mono diet goat milk cleanse accompanied by a specific vermifuge made of anti parasitic herbs is the most successful treatment. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/you-probably-have-a-parasite-heres-what-to-do-about-it/)

These examples strategically impart a sense of authority, establishing the non-negotiability of the advice. Some guidance is strikingly similar to traditional diet and weight-loss protocols, as in (18), which exhorts the reader to restrict their food intake choices and exhibit self-control. The short edicts, stacked one after another, and addressed directly to the reader in imperative form (save, break down, make) leave little space for the consideration of alternative actions. In fact, the reader is taken through a highly structured decision matrix in which bad choices are discouraged, but tolerable in the face of extreme temptation (if you must, your big weakness), as long as they are taken with discipline and control. In (19), overlexicalization serves to convey a feeling of precision and expert knowledge. This is evident in the redundancy of mono diet, which describes a goat milk cleanse as a regimen consisting of a single food, as well as anti parasitic herbs to specify the components of a vermifuge, which is, by definition, an anti-parasitic medicine. The unattenuated and boosted epistemic claim that this is the most successful treatment further the authoritative tenor as well, balancing out the hedging of the advice as derived from personal observation (in my experience), which prefaces the entire sentence. As these examples also show, Goop articles make a clear distinction between acceptable and unacceptable foods—those that put the body in good health as opposed to at risk—although restricting/avoiding unacceptable foods is justified as getting rid of unwanted toxins and parasites as opposed to unwanted fat. In both cases, the virtue is in restricting and resisting, and those choices framed as responsible and good lead to a transformed, improved body and self. While the discourse of Goop may be cloaked in language of (female) empowerment and working towards meritorious good health, it does not challenge dominant ideologies that regulate the female body, but rather reproduces those very same ‘deeply ingrained processes of intimate self-regulation’ (Milani Reference Milani2013:629).

In addition to food-restricting practices, the corpus contains a multitude of suggestions for avoiding the harmful substances discussed above.

(20)

1. Eat more vegetables and less meat and dairy, to increase fiber and avoid animal fat.

2. Eat organic food, to avoid cancer-causing pesticides.

3. Buy toxin free personal care and household products—read the labels.

4. Drink lots of fresh filtered water.

5. Sweat several times a week.

6. Exercise regularly, even if it is just a 20 minute work-out. (https://goop.com/wellness/detox/does-detoxing-really-work/)

(21) The first is to take inventory of what oral-care products you are using and then eliminate products that might strip and/or destroy the microbiome. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/oral-microbiome/)

(22) I recommend removing baseboards, cutting out wet drywall, removing wet carpet or hardwood floors, to minimize the risk for mold any time you have a leak. (https://goop.com/wellness/health/how-to-identify-hidden-mold-toxicity-and-what-to-do-about-it/)

The verbs in these examples aid in imparting a sense of urgency. In (20), each of the verbs, offered in list form, is in the imperative (eat, buy, read, drink, sweat, exercise), compelling the reader to take these actions. In (21) and (22), the verbs depict extraction (eliminate, remove, cut out), instructing that until the toxic elements are removed, the danger remains; thus, it is crucial to act. Moreover, these examples also illuminate the way in which Goop reproduces a neoliberal logic that ignores structural inequities. Such choices are afforded only to those who inhabit privileged lives; as adduced by Skeggs (Reference Skeggs2004), the capacity to choose is in itself a resource. For example, dismantling portions of one's home (taking out walls and flooring) not only assumes access to resources that such projects require, like time and money, but also that the readers own the home they are living in and thus are licensed to undertake such renovation projects. Drinking fresh filtered water similarly requires access to resources, needed to either purchase a filter or regularly buy bottled water. Imperatives such as these fuel the fear-driven narrative that neoliberal risk culture rests upon; having the knowledge and acting appropriately is the only rational choice (Ng Reference Ng2019; Skeggs Reference Skeggs2004; Harvey Reference Harvey2005), and structural barriers are left out of the equation.

As noted above, the practices of restriction and elimination represent only one part of Goop's scheme for acting in ways congruent with ideal neoliberal citizenship; ensuring that the body is well also rests upon making the right choices around consumption. Of course, choosing properly when it comes to food and eating is paramount for the neoliberal female. So-called ‘clean eating’, which includes, for example, detoxes and raw or plant-based diets, is lauded as responsible for a similarly wide-ranging set of cures. Particular foods are often identified as directly responsible for curing specific illnesses and maladies: sweet potatoes are purported to ‘cleanse and detox the liver from EBV byproducts and toxins’; celery juice with cilantro is said to ‘cleanse your body of toxic heavy metals’; and raw honey is claimed to ‘stop cancer in its tracks’. The cost required, in time and money, to procure ‘clean’ foods (which entails avoiding, for example, processed foods, which are widely accessible and highly affordable) is ignored. Instead, the only rational course of action is presented as choosing foods and products promoted for their ability to enhance overall well-being; the subject is assured that by doing so, they are on the path to an improved version of the self.

Health and happiness are embodied on goop.com by the slim, white, class-privileged female who overwhelmingly inhabits the pages throughout the site, refractions of Gwyneth Paltrow herself. This image of ‘idealized whiteness’ (Graefer Reference Graefer2014; see also Shome Reference Shome2014; Wilkes Reference Wilkes2021) cultivates a disciplined and docile body. Always striving for the happiest, healthiest version of herself, Paltrow is—and the reader is asked to be—morally responsible and virtuous. It is in this ‘pursuit of an ever-changing, homogenizing, elusive ideal of femininity’ that the docile body is reproduced (Bordo Reference Bordo1993:14). In Goop's online world, in the visual representations that appear alongside the articles, it is the middle- and upper-class white woman specifically who is positioned as the ultimate embodiment of wellness. This picture of the ideal neoliberal citizen, always called on to enact transformative, self-actuating practices is also congruent with media representations of ‘clean living’ practices more broadly. As Wilkes (Reference Wilkes2021:4) writes, ‘Middle- and upper-class interests appear to be aligned in the visual representations of wellness as white and female, as both class groups have embraced and promoted “wellness” and healthy eating through consumption as acts of distinction’. Within a white supremacist patriarchal system, the class-privileged white female is positioned discursively and visually as the emblem of good taste and distinction, as the icon of self-improvement, and what the (white) female subject ought to strive for in her own never-ending process of self-transformation. Whether this is scrutinizing every piece of clothing purchased to ensure it is free of flame retardants, replacing all dental fillings with a composite that is mercury-free, or scooping adaptogenic powders into smoothies, she is calculating in every decision, constantly signaling her virtue and moral responsibility. She is doing all the right things to secure her own health, happiness, and overall well-being in a society where risk is inescapable and in which the body is always potentially in harm's way. This is a powerful tool of the neoliberal regime, its ability to call up a ‘happy object’ (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2010) to which the self-interested subject can aspire; here, it is a compelling figure whose health and happiness the subject can also achieve, if only they make the right choices.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

This article has asked how the body is discursively constructed in the world of wellness, with a particular focus on the Goop enterprise, as one of the most well-known franchises of wellness in the US and across the world. The analysis has revealed a focus on mechanisms of bodily regulation and control within a neoliberal framework, which obliges individuals to make rational decisions to minimize risk and work towards an ongoing project of improving the self. I have shown that the body is ultimately constructed as not well and as at risk within wellness discourse. Here, a new mechanism of control for the reproduction of docile bodies has emerged. More than long-recognized practices ‘directed toward the display of [the feminine] body as an ornamented surface’ (Bartky Reference Bartky, Diamond and Quinby1988:27) having to do explicitly with normative standards of beauty and attractiveness, the locus of control on the docile female body lies its discursive construction as inherently at risk. And not only at risk of violence or sexual assault, or of being unattractive or otherwise abject—for these things would run counter to the autonomous, free, empowered female that our ‘postfeminist sensibilities’ (Gill Reference Gill2008) have imagined—but at risk by virtue of being a body in the environment. The risk is thus at once everywhere and inescapable, calling for the subject to be ever-vigilant, widely knowledgeable, and willing to enact the right choices to reduce harm.

While many examples examined here in fact demonstrate that there are systemic issues that enable, for example, the circulation of toxins in the environment, the onus is on the individual to act responsibly: exerting control by simultaneously engaging in restrictive practices and consciously consuming the correct foods and products, in order to be fully healthy and productive. Neoliberalism does not care about structural inequities; citizens must, no matter the cost, make self-interested, rational choices rather than the government intervene to prevent disastrous situations like lead in drinking water, which disproportionately affect underserved communities.

Additionally, while I have been unable to give attention to the issue here, it is worth pointing out the rampant cultural appropriation within the wellness industry of practices and elements from countries such as China and India (see e.g. Wilkes Reference Wilkes2021 and Starr et al. Reference Starr, Go and Pak2022 for further discussion). The Goop corpus is replete with references to, for example, Ayurveda and ashwaghandha, and features a recurring themed section called ‘Ancient modalities’. Throughout the corpus, these appropriated practices are incorporated into the business of wellness, and in particular are recruited as tools for curing a vague set of bothers, or a general sense of malaise. Again, while beyond the scope of this article, it is useful to note that the construction of an orientalized Other—as imagined collectives of healthy and wise brown people rooted deeply in old cultural traditions—further centers whiteness as the invisible norm, and white people as superior in morality and virtue (Hill Reference Hill2009; Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2019), having the capacity to harness this knowledge for application in the modern world.

My purpose in this analysis has not been to determine the truth value of the articles in the Goop corpus, nor to evaluate their merit. I do not purport to judge or minimize the effects of substances like mercury on the body or in the environment. Instead, my goal has been to interrogate how the body—and what kind of body—is brought into being through wellness discourse. This examination has illuminated how the wellness industry has emerged as a new mechanism of control on the body within the modern neoliberal regime. The female body as a site of political struggle is an enduring concern for feminist scholars and activists alike. A discourse of fear is central to upholding the heteropatriarchal order; a female subject who is afraid—of getting old (Coupland Reference Coupland, Coupland and Gwyn2003), of getting fat (LeBesco Reference LeBesco2011), of being violently assaulted (Tulloch & Tulloch Reference Tulloch, Tulloch, Coupland and Gwyn2003)—is restricted in her actions, and therefore controlled. However, fear and control run counter to current postfeminist sensibility, which celebrates the ‘empowered’ white female citizen, who makes choices that respond to her individual desires, and which make her feel good (Banet-Weiser Reference Banet-Weiser2018; Gill & Kanai Reference Gill and Kanai2019). Contemporary neoliberal discourses of the body thus move away from, for example, explicit talk of dieting for weight loss, but still demand discipline, regulation, and control, and bind these choices closely to morality, virtue, and individual responsibility. The risk has shifted, or perhaps expanded, to an inescapable, ever-present entity—so that sleeping, eating, breathing, indeed merely existing in the environment is cause for constant, sustained vigilance. Displays of class-privileged white femininity hold the promise of the ability to ‘have it all’—the result of carefully calculating each decision to secure optimal health, well-being, and productivity. The discursive construction of the body in wellness thus reveals the industry as a modern purveyor of disciplinary techniques for embodied white femininity. As such, it is a major force in reinscribing a hegemonic norm that is gendered, raced, and classed, and at the same time a mechanism for helping to ensure the continued reproduction of docility.