Introduction

Since the mid-2010s, the United States and China’s relationship has significantly shifted from cooperation to competition. Numerous studies have highlighted the accelerated growth of China’s economic power and its increasing influence on the global political stage, which has been perceived as a direct threat to US leadership in open markets and Western democracies (Wu Reference Wu2016; Zhou, Reference Zhou2019). This shift has triggered significant changes in US politics, particularly evident during Trump’s administration (Zhao Reference Zhao2021; Sutter Reference Sutter, Duarte, Leandro and Galán2023). Scholars have conceptualized these new circumstances as a new “geoeconomic order” (Robert, Moraes, and Ferguson Reference Roberts, Choer Moraes and Ferguson2019).

In this context, economic statecraft has become a salient practice in international politics (Van Bureij Reference Van Bergeijk2021; Aggarwal and Reddie Reference Aggarwal and Reddie2021). The defining characteristic of economic statecraft measures is their pursuit of political and geopolitical goals rather than economic ends (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985), resulting in a blurring of the traditional boundaries between the realms of economy and security. Questions about how and when trade, aid, or investment serve as tools in the hegemonic political competition are central to the current landscape of international political economy.

This article contributes to this literature by examining whether and how measures of economic statecraft have been employed in the US response to Latin American countries’ economic engagement with China. We argue that their engagement with China has been perceived as a threat to US interests, prompting the use of economic statecraft as the main response. Furthermore, we affirm that when dealing with non-revisionist, politically aligned, democratic states—predominantly the case in Latin America—the prevailing response towards engaging with China tends to be positive inducements, or “carrots,” rather than economic coercion or “sticks.”

Over the past two decades Latin America has experienced significant growth in its economic ties with China, transforming it into the primary trade partner for many nations. Additionally, China has become a crucial source of government finances and foreign direct investment (Wise and Chon Ching Reference Wise and Chonn Ching2018). The establishment of the Forum China-CELAC in 2014 expanded the mechanisms by which China was able to channel its presence in the region, forging stronger bonds of political and technical cooperation. In 2018, Beijing extended an invitation to CELAC to become part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). By the end of 2022, 20 countries from the region had already become members.

This development is particularly striking considering Latin America’s longstanding relationship with the United States as “America’s Backyard.” Initially, the expansion of China’s economic and political engagement in Latin America went unnoticed by the US and was rather seen as “another piece in the US-led globalization process” (Cordeiro Pires and do Nascimento Reference Cordeiro Pires and do Nascimento2020). Obama’s Administration acknowledged the challenges involved in China’s economic rise, but focused its attention on the Pacific Region (Clinton Reference Clinton2011). As the global inter-hegemonic dispute became tighter, this initial American indifference to the growing Chinese influence in Latin America started to change. Several speeches and documents from Trump’s years illustrate this perception of Chinese economic presence in Latin America as a threat to American interests. Examples include Tillerson’s declaration on the Monroe Doctrine; Trump’s speech at the UN General Assembly in September 2018, and also the 2021 Annual Report of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

It became evident that initiatives previously perceived as neutral, such as BRI, came to be perceived as a threat to US strategic interests in the region. The United States expressed concerns about Chinese influence over critical trade routes and its dominance in critical technologies, such as lithium resources, which are crucial for American competitiveness (US-China Economic and Security Review Commission 2021). In addition, the United States warned against Chinese “predatory loans” that burden countries “with unsustainable debts and threats to national security and sovereignty” (Department of State 2019b, 2020). Overall, Latin American engagement with China became framed as an institutional threat that could potentially undermine democracies and free open markets, and endanger US security partnerships in the region.

Despite Latin America’s significant position within the geoeconomic order, the impact of the hegemonic dispute on the region has remained an overlooked topic in academic literature, with only a few exceptions. Some studies have focused on the growth of economic ties with China, including the Latin American countries’ participation in the BRI (Wigzell and Landivar Reference Wigell, Landivar, Wigell, Scholvin and Aaltola2018; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2022a). Others have explored Latin American foreign policy strategies, as seen in the works of Heine and Ominami (Reference Heine and Ominami2021) and Gachúz Maya (Reference Gachúz Maya2022). Paradoxically, the US response to these changes in Latin America has been a less studied aspect of the issue. Previous empirical studies have highlighted that during 2003–2014, “Beijing has filled the void left by a diminished US presence in the latter’s own backyard” (Urdinez, Mouron, Schenoni, and de Oliveira Reference Urdinez, Mouron, Schenoni and de Oliveira2016, 1). However, there has been limited research on the American response to China’s growing influence in the region during the subsequent decade, particularly during the administrations of Donald Trump (Cordeiro Pires and do Nascimento Reference Cordeiro Pires and do Nascimento2020) and Joe Biden.

This article aims to explore how the United States has reacted to the increased presence of China in the region. Specifically, we will assess how and when the United States has utilized its economic statecraft toolkit of sticks and carrots as a reaction to Latin American countries’ tightening relations with China.

The contribution of our article is twofold. First, it enhances the understanding of the Latin America-US-China relationships in the twenty-first century. Second, it sheds light on the conditions driving the decision process of economic statecraft. While the effectiveness of economic sanctions and incentives has been deeply debated (Drezner Reference Drezner1999a; Blanchard and Ripsman Reference Blanchard and Ripsman2013), the conditions under which these tools are incorporated in foreign policy strategies is still a controversial issue (Zhang Reference Zhang2001; Lai Reference Lai2022).

The article proceeds as follows. We delve into previous theoretical and empirical literature focusing on the conditions that trigger the utilization of economic statecraft and the selection of the specific tools to be used by the initiator state. We also explain our theoretical argument and why we expect an economic-centered response by the United States to the increasing Chinese presence in the region and the conditions under which positive statecraft (“carrots”) is more likely. Next, we analyze the case of Panama’s economic engagement with China. Besides, we also present statistical evidence on the allocation of US foreign assistance disbursements supporting our hypothesis.

The Dynamics of Economic Statecraft: Triggers and Choices

Geoeconomics or economic statecraft strategies involve the use of economic tools and leverage to achieve strategic objectives that go beyond economic outcomes. These strategies encompass a wide range of measures, including promises or threats, with different aims. For example, shaping the strategic environment (Vihma, Reference Vihma2018) and influencing the behavior of other countries by deterring or compelling them to take certain actions (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985; Mastanduno, Reference Mastanduno, Mansfield and Pollins2003). Although the use of economic statecraft is not a new phenomenon in International Relations, the expansion of economic interdependence through globalization has led to an increased significance in recent years.

While traditional studies have primarily focused on sanctions and economic coercion (Aggarwal and Reddie Reference Aggarwal and Reddie2021), economic statecraft encompasses a wide range of tools, including trade policy, investment policy, economic sanctions, cyber measures, economic assistance, financial and monetary policy, national policies related to energy and commodities (Blackwill and Harris Reference Blackwill and Harris2016), as well as regulatory policies governing market access and value chains (Aggarwal and Reddie Reference Aggarwal and Reddie2021). Each action of economic statecraft involves three elements: the specific measure employed (or the promise or threat thereof); the target (whether government or individuals); and the goal pursued by such action. Although some goals may remain implicit, the use of economic statecraft always involves some form of communication from the sender, conveying their demands or conditions (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985; Drezner Reference Drezner1999a). In addition, it entails a conscious policy decision (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985), evaluating the distributional costs it entails for the sender and the target (Drezner Reference Drezner1999a; Chen and Evers Reference Chen and Evers2023).

While the effectiveness of economic statecraft has been a focal point of academic debate, the question of how and when states resort to this type of strategy and which kind of tool is used remains a contested issue in the literature. Not every international challenge would lead to the use of economic statecraft, whether carrots or sticks.

The literature has identified a multicausal set of conditions, encompassing factors such as the salience of the defiant situation (Dobson Reference Dobson2002; Vihma, Reference Vihma2018, Baracuhy, Reference Baracuhy, Wigell, Scholvin and Aaltola2019), the sender’s bureaucratic capabilities, as well as its reputational and economic costs (Farrell and Newman Reference Farrell and Newman2019; Blackwill and Harris Reference Blackwill and Harris2016; Zhang Reference Zhang2019). Additionally, it considers the target’s political alignment, economic vulnerabilities, and the presence of alternative options (Peksen & Peterson, Reference Peksen and Peterson2016).

The decision on economic statecraft also involves determining the nature of the measure to employ, be it sticks, carrots, or a combination of both. We define “sticks” as the use, or threat to use, of coercive economic measures that restrict economic flows between the target and the sender, pursuing a political or strategic goal. These include export restrictions, tariff increases, withdrawal of most favored nation treatment, freezing assets, capital control, aid suspension, and similar actions. On the other hand, “carrots” are economic rewards, or the promise of them, fostering economic exchanges between the target and the sender. These economic engagement measures can be channeled through official international assistance, humanitarian aid, development finance, access to currency, trade preferences, preferential tariffs and subsidies. It is noteworthy that existing literature distinguishes between short-term incentives, which focus on achieving a specific and relatively immediate change in policy, and long-term inducements, also termed “catalytic,” which are designed to transform the target state’s interests and preferences (Blanchard and Ripsman Reference Blanchard and Ripsman2008; Nincic Reference Nincic2010; Donovan et al. Reference Donovan2023).

The choice of carrots or sticks is influenced by the conditions met by the target state and the resources available to the sender. It results from carefully considering the specific combination of “effectiveness, efficiency, legality, democracy, and legitimacy” of the policy options within a given context (Bemelmans-Videc et al. Reference Bemelmans-Videc, Rist and Vedung2011, 7). In numerous instances, negative and positive measures coexist (Caruso Reference Caruso2021).

The political alignment of potential targeted parties is relevant. Feldhaus et al. (Reference Feldhaus2020) argue that sanctioning behavior is more likely when the parties are not allies. Drezner (Reference Drezner1999a) posits that since threats of sanctions tend to be more effective when applied to partners, it would be more probable to find sanctions targeted to non-allies. In the realm of positive statecraft, Mastanduno (Reference Mastanduno, Mansfield and Pollins2003, 181) argues that economic engagement aims to strengthen internationalist coalitions within the target country at the expense of the nationalists, ultimately shifting the balance of domestic political power in favor of the former.

Additionally, the political regime affects the probability of “carrots” or “sticks.” Democracies are more likely to receive positive incentives than autocratic regimes due to lower transaction costs, as they are more capable of making credible commitments and have greater standards of transparency (Drezner Reference Drezner1999b). On the contrary, non-democratic states are more likely to receive sanctions (Peksen and Peterson, Reference Peksen and Peterson2016).

Lastly, it is important to note that the logic of economic engagement presupposes that the target state is not inherently revisionist or that if it is not currently a status quo state, it has the potential to be transformed into one (Mastanduno Reference Mastanduno, Mansfield and Pollins2003). Positive engagement has tended to require greater legitimacy than sanctions and negative economic statecraft (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1971).

The selection of the economic statecraft tool is also influenced by the capabilities and characteristics of the initiator state. Economic interdependence is a cornerstone of the power involved in economic statecraft. The specific sectors involved and their relation to domestic interests are also relevant considerations (Kastner Reference Kastner2007; Davis and Meunier Reference Davis and Meunier2011; Chen and Evers Reference Chen and Evers2023). Furthermore, the policy space available to the government to foster or interrupt economic fluxes is a crucial factor (Zelicovich Reference Zelicovich2023). The costs and durability of the chosen economic statecraft measures are also important considerations (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1985). It is worth noting that economic engagement is often a long-term strategy, requiring consistent application over time and the support of robust and stable bureaucracies (Mastanduno Reference Mastanduno, Mansfield and Pollins2003). For the sender, sticks tend to be costly when they fail, whereas carrots create costs when they succeed (Drezner Reference Drezner1999b).

Additionally, Drezner has introduced the expectations of future conflict as a condition influencing the choice between carrots and sticks. The larger the expectation of conflict, the more likely the sender is to apply sanctions. With adversaries, carrots will emerge only after a coercion attempt. On the contrary, with allies, when reputation effects are minor, it is more likely to use carrots, enhancing the utility of both the sender and the receiver (Drezner Reference Drezner1999a).

Unpacking the Argument: Conditions for Positive Economic Statecraft in Latin America

In our analysis, we focus on identifying specific conditions that shape a situation as a salient challenge for the initiating state within a given international context. These conditions should include the threat to a strategic interest, an asymmetric interdependence relationship where the initiating state holds a more powerful position, and a limited ability of the target state to mitigate the impact of economic measures through third-party channels. Additionally, the initiating state should have domestic support and vested interests in the economic statecraft measures, along with sufficient bureaucratic capabilities to sustain them. The initiating state should possess the necessary legitimacy and policy space to implement these actions. In general terms, sanctions—or threats of them—are more likely to be imposed when policies pursue short-term goals and the target country has a revisionist government. Conversely, carrots—economic engagement instruments or promises of them—are more probable in long-term strategic situations where the target country has an allied democratic internationalist government.

This article asserts that Latin America appears to be a fertile ground for the exercise of economic statecraft by the United States in response to strategic hegemonic competition. In addition, we hypothesize that positive economic statecraft—carrots—will be the prevailing answer when three conditions are met: the challenge threats a strategic American interest, the challenger is a non-revisionist democratic state, and sanctions are unlikely to succeed as a consequence of the target’s power or the existence of an outside option to mitigate potential economic costs. Furthermore, our theory predicts that positive economic statecraft will be the preferred economic tool when the ultimate goal is changing the target’s preferences, whereas sticks will prevail in achieving short-term specific policy changes.

Our central argument is that in the case of democratic and politically aligned countries, the US response to a closer economic relationship with China will not be primarily based on coercive economic statecraft. On the contrary, we expect that positive incentives are offered to the challenger to change its preferences. We state that BRI and Chinese infrastructure investment in Latin America can be framed as this type of challenge. They are perceived as a threat by the United States while simultaneously providing a third option for target economies in Latin America.

To test this argument, we first did a qualitative content analysis of US official reports and speeches from 2016 to 2023. This analysis aimed to identify the positions of the Trump and Biden administrations regarding Chinese economic presence in Latin America.

Next, we analyzed the case of Panama, a longstanding ally of the United States in the region. During the presidency of Varela, Panama implemented two distinct policies that challenged American hemispheric interests. In 2017, Panama made a significant diplomatic shift by recognizing the People’s Republic of China, which posed a major setback for Taiwan’s foreign policy objectives. A few months later, Panama joined the BRI and became the first Latin American country to participate in the Chinese project. Panama became a significant recipient of Chinese investment in infrastructure, particularly in ports and railroads. This move signaled a departure from traditional economic ties with the United States.

Panama’s economic engagement with China stands out as a unique case due to its profound implications for the American hemispheric strategy. Panama’s foreign policy choices carry exceptional sensitivity to strategic American interests as a consequence of its geographic location and the presence of the Panama Canal, one of the world’s most vital maritime choke points. Given its strategic importance and its role in maintaining American influence in the region, any actions or developments that could potentially undermine the American presence in the country would be a matter of significant concern to the United States. Consequently, the growing economic presence of China in Panama is more challenging to American interests than in any other country in the region.

Against this backdrop, Varela’s policies could be framed as a security concern and be responded to with diplomatic and economic coercive measures. However, if our theory is accurate, we would expect a positive statecraft response by the United States instead of sanctions. This is a consequence of two factors. First, Panama is a democratic State. Sanctions are expensive and difficult to justify against democratic states. Second, the promise of Chinese investment and economic flows presents a significant challenge, but one that is difficult to address with coercive economic statecraft. As the level of investment and economic ties with third countries increases, the effectiveness of punitive economic measures diminishes, as the targeted country has alternative options to mitigate the impact.

The case analysis study involved examining official US documents, including those from the Foreign Affairs Committees of the US Congress, as well as press releases and documents from the Department of State, and the US embassy in Panama, among others. We analyzed several speeches to trace how the US framed China’s presence in Panama as a challenge and examined whether any mention of economic instruments, such as promises, threats, or positive and coercive economic statecraft, was made. In addition, we observed the evolution of US-Panama economic flows, including trade, foreign assistance, and foreign investment, tracking them to identify any connections to the hegemonic competition. To consider an economic tool, or its promise or threat, as evidence of economic statecraft, it needed to be attributable to a governmental decision linking the weaponization of a specific economic flow to a political objective. This objective could involve a policy change related to the Panama-China relationship or a shift in Panama’s preferences countering Chinese influence. In each case, we classified the “carrots” or “sticks” by identifying the triggering situation, the stated goal, the main instrument implied, and whether it was a regional measure or explicitly targeted at Panama.

The declarations made by government officials across various agencies shed light on the reasoning behind foreign policy measures, which should align with the proposed hypothesis and causal mechanisms. By employing these sources, we were able to better understand the dynamics at play and evaluate the validity of our argument. Up to our knowledge, the Panama-US relationship after Panama established relationships with China has not been studied in the academic literature. Meanwhile, Panama’s ties with China and Chinese economic statecraft in this country have been analyzed by Mendez and Alden (Reference Mendez and Alden2021); Herrera et al. (Reference Herrera, Montenegro and Torres-Lista2021); Portada, Lem, and Paudel (Reference Portada, Lem and Paudel2020), among others.

Finally, we run a statistical analysis to check if our theoretical expectations can also pass a hoop test, including all countries in the region. In this regard, we assess the effects of economic engagement with China on the allocation of American foreign assistance, a key economic statecraft tool. Following our hypothesis, we argue that, if a Latin American country is aligned with the United States, engaging with China should have a positive effect in terms of the reception of American foreign assistance in the future.

Case Study: Us Response to Panama’s Engagement with China

Panama’s decision to join BRI came as a surprise to America’s government and potentially marked a turning point in US-Latin American relations. As discussed earlier, Latin America had gradually diminished in relevance in US foreign policy, while China’s positive economic engagement in the region had gained prominence. However, the longstanding position of the United States in Panama made the signature of the MoU in 2017 an unexpected move. Panama has traditionally been one of the main partners of the United States in Central America.

Some political unrest during Varela’s presidency arose in 2015 as a consequence of the asylum granted to former president Ricardo Martinelli in the United States and the controversy surrounding the “Panama Papers.” Furthermore, Panama’s budget in the US Strategy for Engagement in Central America was reduced due to the growing focus on the “Northern Triangle” of Central America and Panama´s improved economic performance. However, overall, the relations between the United States and Panama remained in good shape. The United States was by far the main market for Panama’s trade goods (21.7% of total exports).

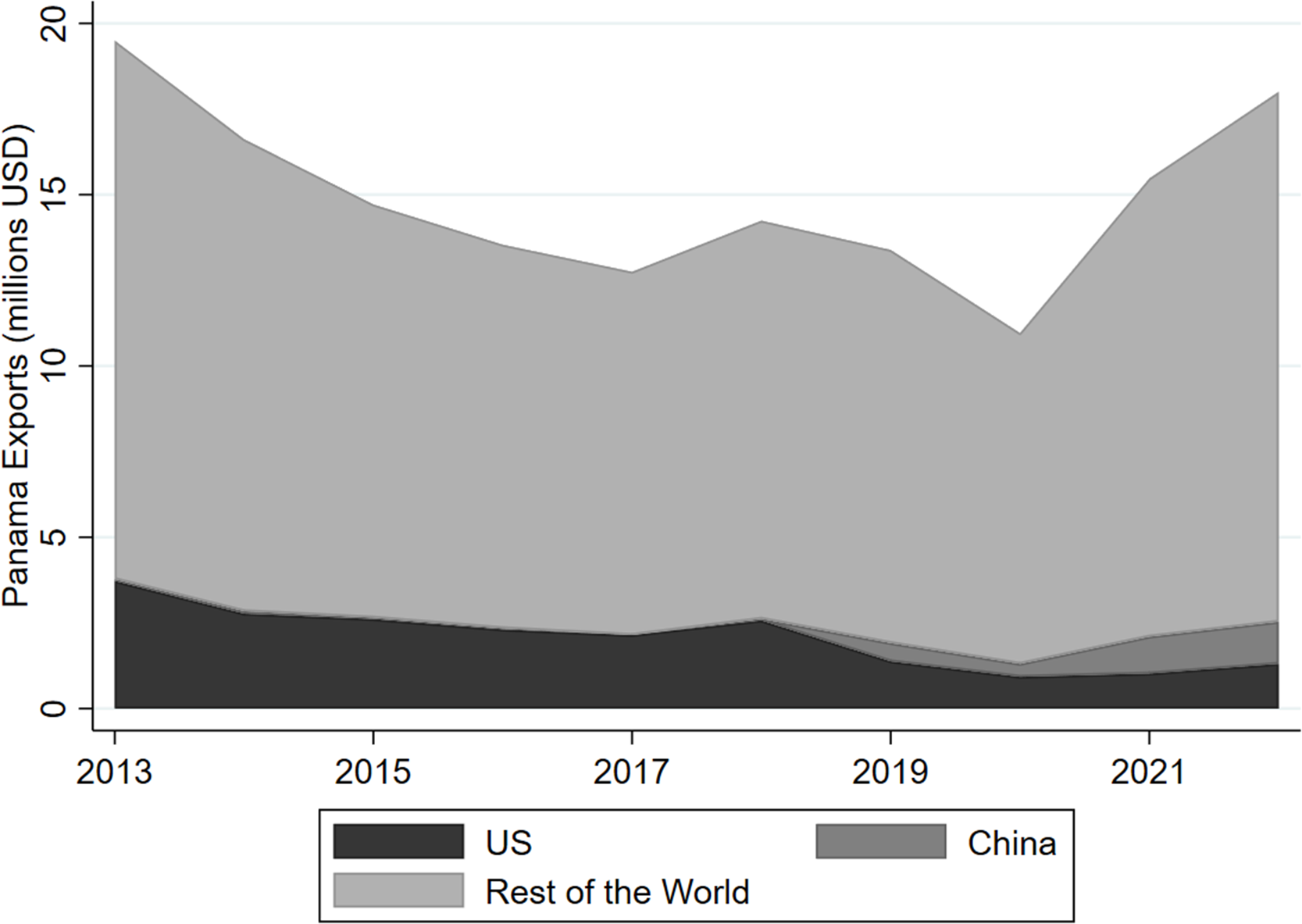

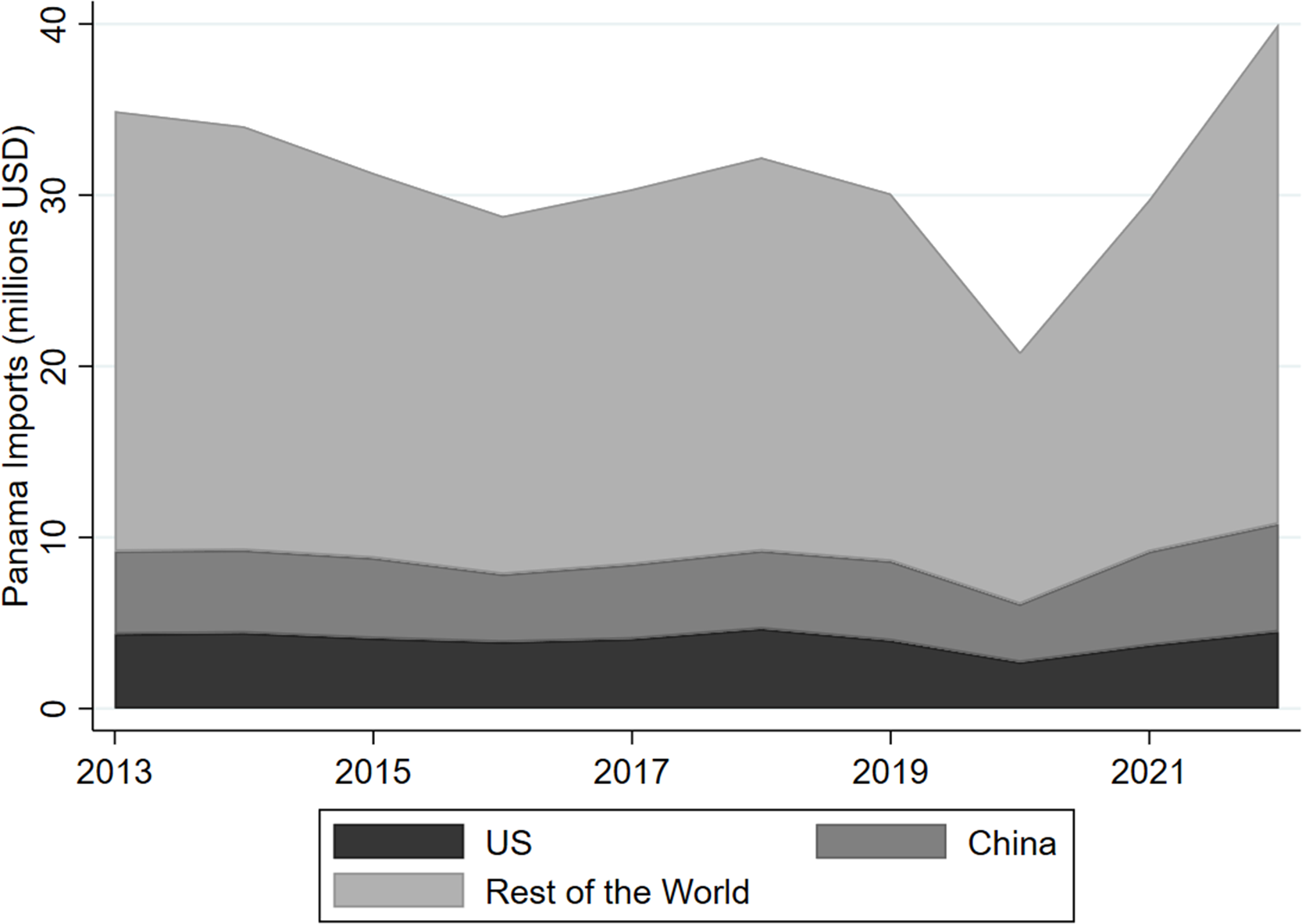

Within this context, the forthcoming foreign policy decisions by the Panamanian government were highly unexpected. On June 12, 2017, Panama announced the termination of its ties with Taiwan and the establishment of diplomatic relations with China, just days before Varela’s meeting with President Trump.Footnote 1 According to the press, the American ambassador to Panama at the time, John Feeley, learned about the switch only an hour before it was announced during a conversation with President Varela about an unrelated matter (Wong Reference Wong2018). In November 2017, Varela made an official visit to China, followed by the signing of the MoU to enter BRI. By the end of 2018, Panama had signed 47 bilateral agreements with China (Marra de Souza et al. Reference Marra de Souza, Duarte, Leandro and Galán2023). Over the following months, trade with China experienced exponential growth, mirrored by a reduction of US participation in total exports (Figures 1 and 2). These substantial shifts in trading partners highlight the transformative impact of China’s engagement in Panama’s trade landscape.

Figure 1. Panama Exports Destinations 2013–2022.

Source: International Trade Center, 2023

Figure 2. Panama Import Origins 2013–2022.

Source: International Trade Center, 2023

The growing engagement with China was initially perceived as a bilateral matter between Panama and China, with the United States showing little significant concern (Department of State 2017, June 13). Gradually, however, this perception evolved into a more interventionist stance. Washington began cautioning Panama, stating that “Chinese practices are not always beneficial to governments in the region” (Department of State 2018, October 17). This change in perspective was subsequently reinforced by Secretary Pompeo’s official visit to the region, underscoring Panama’s renewed importance on the US agenda. This shift is also evident in the increased frequency of official missions, as well as the growing number of references to Panama in reports and speeches. By engaging with China, Panama captured the attention of the US bureaucracy. The decision of the Dominican Republic and El Salvador to also cut ties with Taiwan, following Panama’s move, heightened the concerns of the US government.Footnote 2

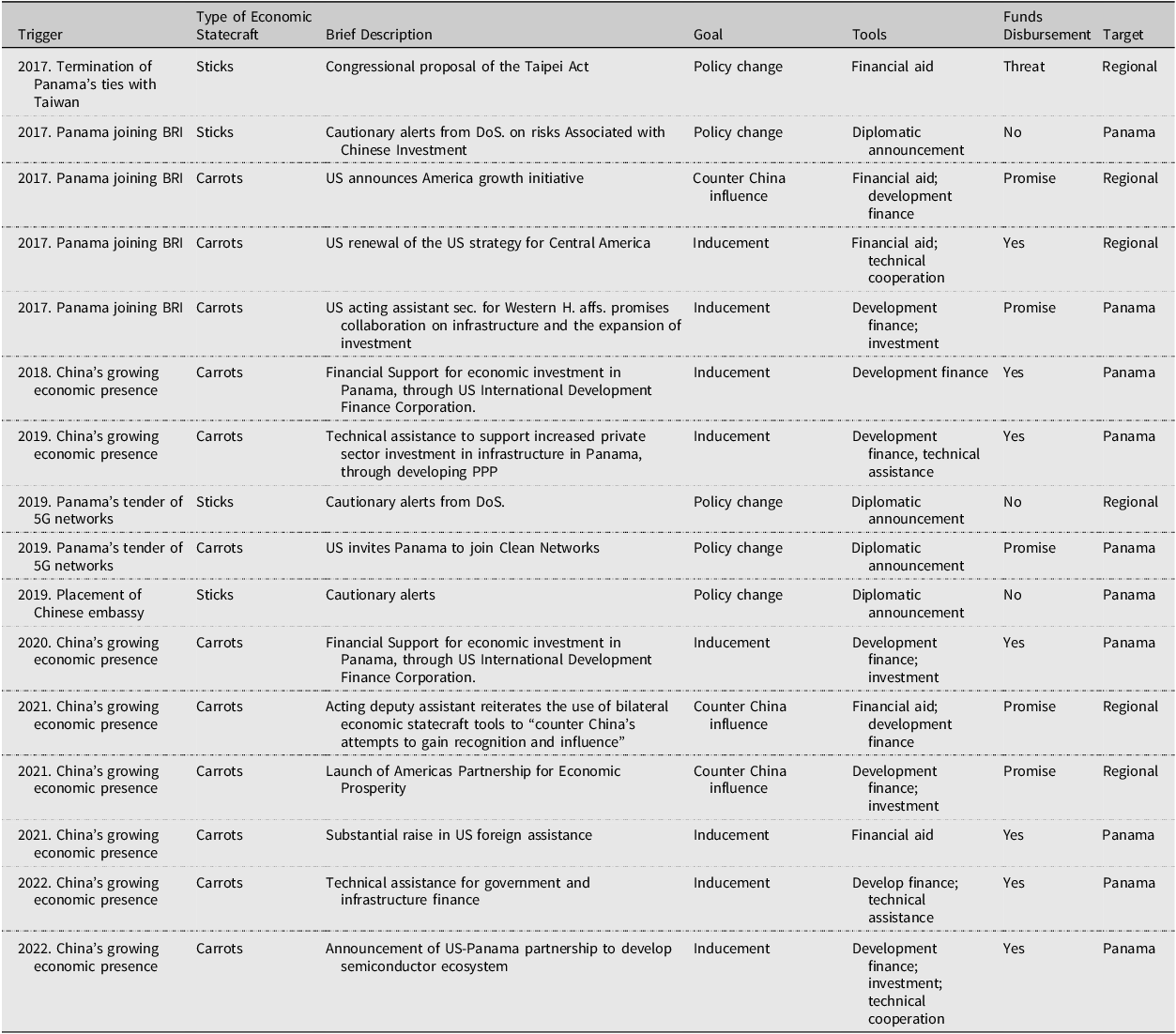

US concerns about Chinese investment and economic activities in Panama were acknowledged in reports to Congress (Sullivan Reference Sullivan2020). Marco Rubio’s (R-FL) proposed the Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (TAIPEI Act), which aimed to downgrade US relations with governments moving away from Taiwan, signaling how this shift was perceived and responded to by some domestic coalitions. However, despite the concerns raised, the United States has refrained from implementing coercive measures involving negative economic statecraft towards Panama. On the contrary, the prevailing strategy has been focused on positive economic engagement, indicating a renewed emphasis on offering economic benefits and promoting cooperation to counterbalance China’s influence in the region (Table 1).

Table 1. Carrots and Sticks in US Reaction to Panama’s Engagement with China (2017−2023)

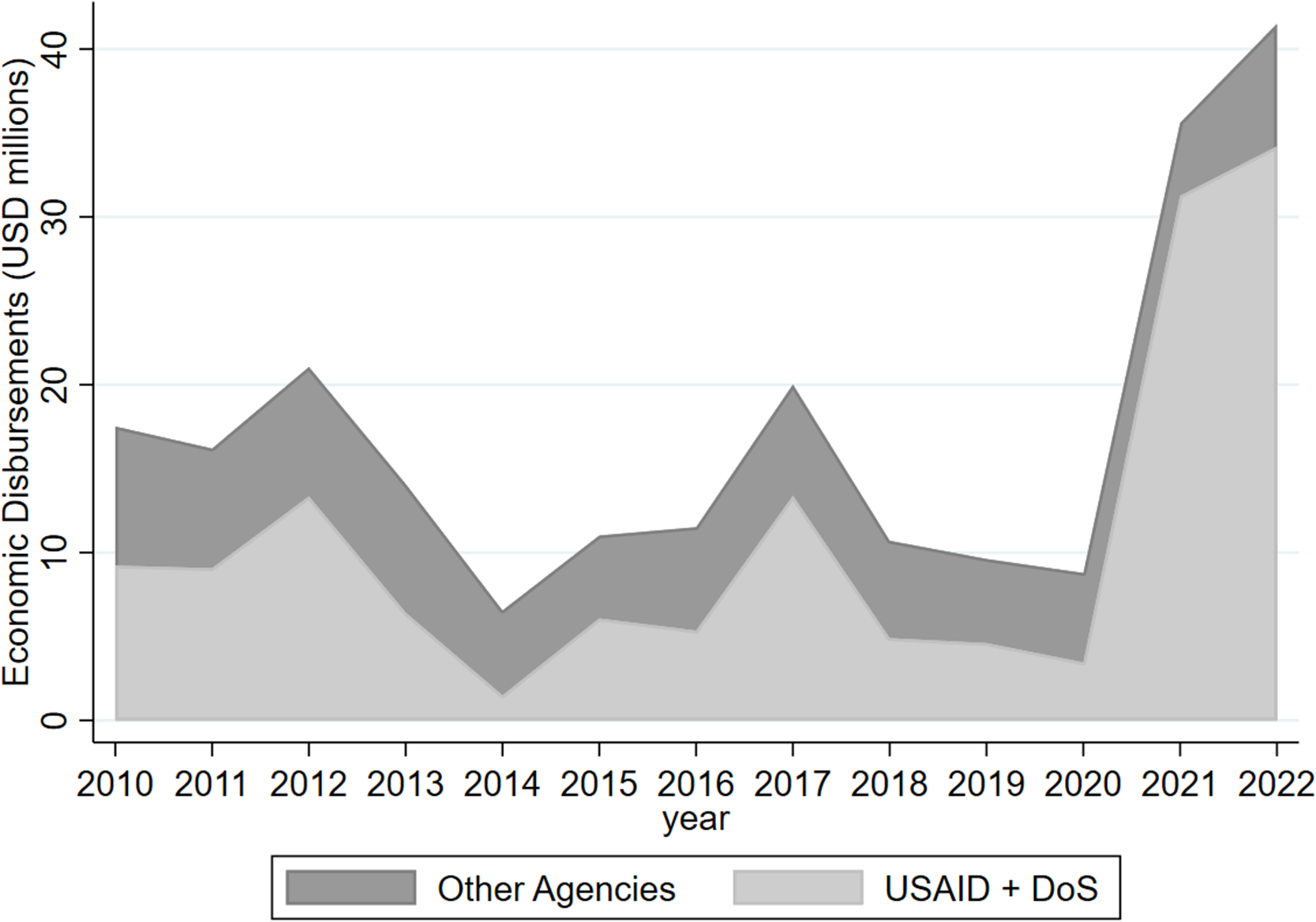

First, the US response involved reframing previous economic engagement tools within the context of the geopolitical competition in Central America. For example, Pompeo explicitly addressed the concerns about the geopolitical implications of Chinese economic presence in the region in his remarks at the 2018 Conference on Prosperity and Security in Central America (Reference Pompeo2018), which came as part of the renewal of the US Strategy for Central America. In 2018, the United States announced the Growth in the Americas Initiative, which focused on creating partnerships with Latin American governments and supporting economic development and infrastructure—which competed with Chinese expansion in the region. Panama was also included in this initiative. These were “carrots” looking to counter the Chinese expansion, although many of them remained only promises. In the context of fiscal limitations in the US Agency for International Development (USAID) budget,Footnote 3 US foreign assistance obligations to Panama were maintained, but actual disbursements decreased between 2017 and 2020. However, after 2021, foreign assistance disbursements rapidly increased again and more than quadrupled in one year (see Figure 3).

In the 2019 presidential election in Panama, pro-US candidate Laurentino Cortizo emerged victorious. Following our proposed causal mechanism, allied democracies with internationalist coalitions, such as Cortizo’s government, are expected to be targeted with positive economic engagement as a preferred economic statecraft tool. Indeed, numerous announcements and actions during this period indicate the growing economic relationship between the two countries. In 2019, Ambassador Michael Kozak, US Acting Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs, conducted his first trip abroad to Panama, where he made promises regarding collaboration on infrastructure and the expansion of pro-market investment (Department of State 2019a). Additionally, several meetings throughout 2020 further solidified the relationship between the parties. US Foreign Assistance started to grow. These closer ties with the United States did not result in a reversal of the economic engagement with China. Even though some areas, such as infrastructure contracts, experienced a cooling down, Panama’s exports to China still skyrocketed, reaching 8% of total exports in 2021—more than ten times the level of 2018, and in a similar ratio of the exports to the United States—.

In 2020, the United States also launched the Clean Network, an initiative to implement international standards on 5G technology among like-minded countries that restricted access to Huawei and other Chinese companies. By that time, Panama had already started 5G tender preparations. Economic statecraft was part of the toolkit Washington used to reverse this process. There were several cautionary alerts from the US Department, but these diplomatic threats were complemented with carrots (Carreño Reference Carreño2020). The United States invited Panama—alongside Brazil, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica—to join the Clean Network, which implied the promise of economic benefits (US embassy in Panama 2020). Panama did not join the network but backpedaled the 5G announcement soon after (Bnamericas 2021).

The Biden administration continued with the “carrots”-toolkit approach. However, the perception of China’s presence in the region had shifted from a mild concern to that of a strategic rival in foreign relations. This change is evident in the 2022 National Security Strategy, which “recognizes that the PRC presents America’s most consequential geopolitical challenge” (White House 2022, 11). Statements during this period explicitly identify China’s presence as a threat and propose using economic engagement as a geoeconomic strategy in the US-China competition. For example, Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary Laura Lochman reported that “[the US government] will continue to explore the use of bilateral tools, such as (the) US Export-Import Bank trade financing, US International Development Finance Corporation financing, and assistance through USAID, to provide needed economic and technical support. Collectively, these efforts strengthen our ability to […] counter the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) attempts to gain recognition and influence in the Caribbean through malign actions” (2021, 1).

One significant piece of evidence supporting the economic statecraft “carrots” approach came into light in 2022 with the announcement of the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity as part of the Build Back Better World Initiative. This project was explicitly presented as “a viable alternative to Chinese economic engagement” (Nichols Reference Nichols2023, 3). This was in line with previous debates regarding foreign policy towards the region. Brian Nichols, Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs, affirmed that “carrying forward this positive agenda for the hemisphere advances US interests and increases our partners’ resilience to engagements and investments of concern, particularly by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia, Iran, and other actors who do not share our values” (2021, 4). Panama is among the partner countries within this initiative that promises greater foreign assistance and investment for the region.Footnote 4

Further examples of the extension of the “carrots” approach can be found in the 2024 budget debates, where the use of US financial tools for building long-term partnerships in the region was proposed, emphasizing the differentiation of the US approach to development from the “opaque and opportunistic approach of the People’s Republic of China” (Nichols Reference Nichols2023, 2). More recently, the US Department of State announced a partnership with the government of Panama with the aim of “exploring opportunities to grow and diversify the global semiconductor ecosystem under the International Technology Security and Innovation Fund (‘ITSI’ Fund), created by the CHIPS Act of 2022” (Department of State 2023).

Regarding how these economic tools combined with other policy measures, we observed a heightened level of political oversight concerning Panama. Economic statecraft is not an isolated strategy. This was evident through frequent visits from the US Southern Command to the country expressing concern about Chinese economic presence, especially when related to the canal. Furthermore, reports and press releases indicated instances where the United States exerted pressure concerning Chinese investment or the placing of the Chinese Embassy near the canal.Footnote 5 However, there is little evidence of sanctions or economic coercion threats. Even though subtle warnings expressing dissent on Panama’s policy and communications signaling the potential risks associated with Chinese investment have been part of US reactions, these threats have been confined to a narrow set of issues, and the prevailing approach towards Panama’s engagement with China has been one of economic carrots rather than sticks.Footnote 6

It is important to highlight that we found no evidence of economic coercion in trade. According to the Global Trade Alert database, the United States implemented 225 measures between 2016 and 2023 that affected Panama’s trade. From those measures, only 36 measures involved a kind of policy that could be related to a weaponized use of trade flows against Panama.Footnote 7 However, none were specifically targeted towards Panama, but to third markets.

While the effectiveness of US economic statecraft is not the focus of this article, it is worth noting that while Cortizo suspended many Chinese investment projects, it did not reverse its membership to BRI or restore ties with Taiwan. Among others, the building of the new Panama Colon Container Port (PCCP) and the railway in the northern part of the country were projects with Chinese involvement that were delayed or canceled. The government of Panama also discarded the Amador area, at the front of the Canal entrance, as the location for the new building for the Chinese Embassy. In contrast, Chinese companies remained in charge of building a fourth bridge on the Panama Canal, and a subway in Panama City.

Statistical Analysis: Chinese Economic Influence and Allocation of US Foreign Assistance in Latin America and the Caribbean

Our theoretical framework and qualitative case analysis suggest that closer economic ties with China may lead to a positive response from the United States, as long as the challenger is a democratic and non-revisionist country. However, this raises the question of whether our hypothesis applies effectively to other cases in the region. To address this, regression analysis can function as a means of testing our theory’s validity and providing additional evidence in support of our hypothesis.

The statistical analysis of US economic statecraft encounters significant challenges due to two primary factors. First, the available data tends to be skewed towards cases where statecraft tools have been implemented, neglecting the entire spectrum of economic promises and threats (Drezner Reference Drezner1999a). This bias often overlooks the utilization of strategies involving threats, subtle pressure, or the provision of material incentives to influence actions. Second, the decentralized nature of trade and investment in the United States, which are inherently private activities beyond direct government control, poses a particularly difficult challenge. This complexity is further compounded by a multitude of variables affecting trade and investment flows, making precise quantification of economic statecraft extremely difficult (Feldhaus et al. Reference Feldhaus2020).

A potential solution to address these challenges is to narrow the focus to government-controlled material flows that hold the potential to influence policies in countries with asymmetrical interdependence with the United States. An effective strategy in this context is to examine the allocation of foreign assistance, which can provide insights into the utilization of economic statecraft. Overseen by several agencies within the US government, mainly the USAID and the Department of State, foreign aid and development assistance hinge on congressional approval and operate under presidential guidance. In addition, several agencies maintain a persistent presence across Latin America and the deployment of its funds has been previously explored as an instrument of statecraft, such as its role in promoting democracy (Collins Reference Collins2009).

In this line, we test the impact of economic engagement with China on the value of US foreign assistance received. In essence, we expect that the effect of variations in the level of Chinese economic influence on the future US foreign assistance received will depend on the recipient characteristics. Our hypothesis is that Latin American and Caribbean countries that are politically and economically aligned with the United States and increase their economic engagement with China are more likely to receive positive economic incentives (“carrots”) and benefit from an increase in US foreign assistance. By contrast, countries that are not aligned with the United States and increase their economic ties with China are more likely to be subject to negative statecraft (“sticks”) and, therefore, observe a decrease in the reception of American foreign assistance.

To test this hypothesis, we perform a series of regressions with panel-corrected standard errors, in line with recommendations in the statistical literature (Wilson and Butler Reference Wilson and Butler2007), to predict US foreign assistance allocation to 24 Latin American and Caribbean countries in a ten-year period between 2012 and 2021.Footnote 8 Data on the dependent variable was collected from ForeignAssistance.gov. We use three different measures at this point. First, we include all disbursements categorized as economic foreign assistance sent by all American agencies.Footnote 9 Second, we test our models using a more restrictive measure of assistance, where only economic disbursements made by the USAID and the Department of State were considered. These are the two most relevant agencies in terms of the amount of funds allocated in the region. In addition, qualitative research suggests that they are the agencies that more quickly respond to political changes and are often used to implement economic statecraft measures. Third, we use the complete dataset of annual disbursements, which also takes military assistance into account, as a broader indicator of US economic incentives. All dependent variables are measured in millions of US dollars.

Given our hypothesis, our main independent variable is the level of economic engagement with China, while our intervening variable is the degree of alignment with the United States. To identify the former, we use the annual variations in the levels of bilateral trade, investment, and development assistance provided by China. First, we include the annual variation of exports to China as a percentage of local GDP. All data on bilateral trade was collected from the Trade Map dataset by the International Trade Center. Second, we include data from the China Global Investment Tracker by the Heritage Foundation. We use the annual variation of foreign direct investment and construction contracts combined, measured as a percentage of local GDP.Footnote 10 Third, we include in our models the annual variation of Chinese Development Assistance, also measured as a percentage of GDP. We use data from the Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset (Custer et al. Reference Custer2023; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Andreas Fuchs, Strange and Tierney2022), which is widely used in previous literature on the issue (Blair et al. Reference Blair, Marty and Roessler2022; Brown Reference Brown2023; Dreher and Fuchs Reference Dreher and Fuchs2015).

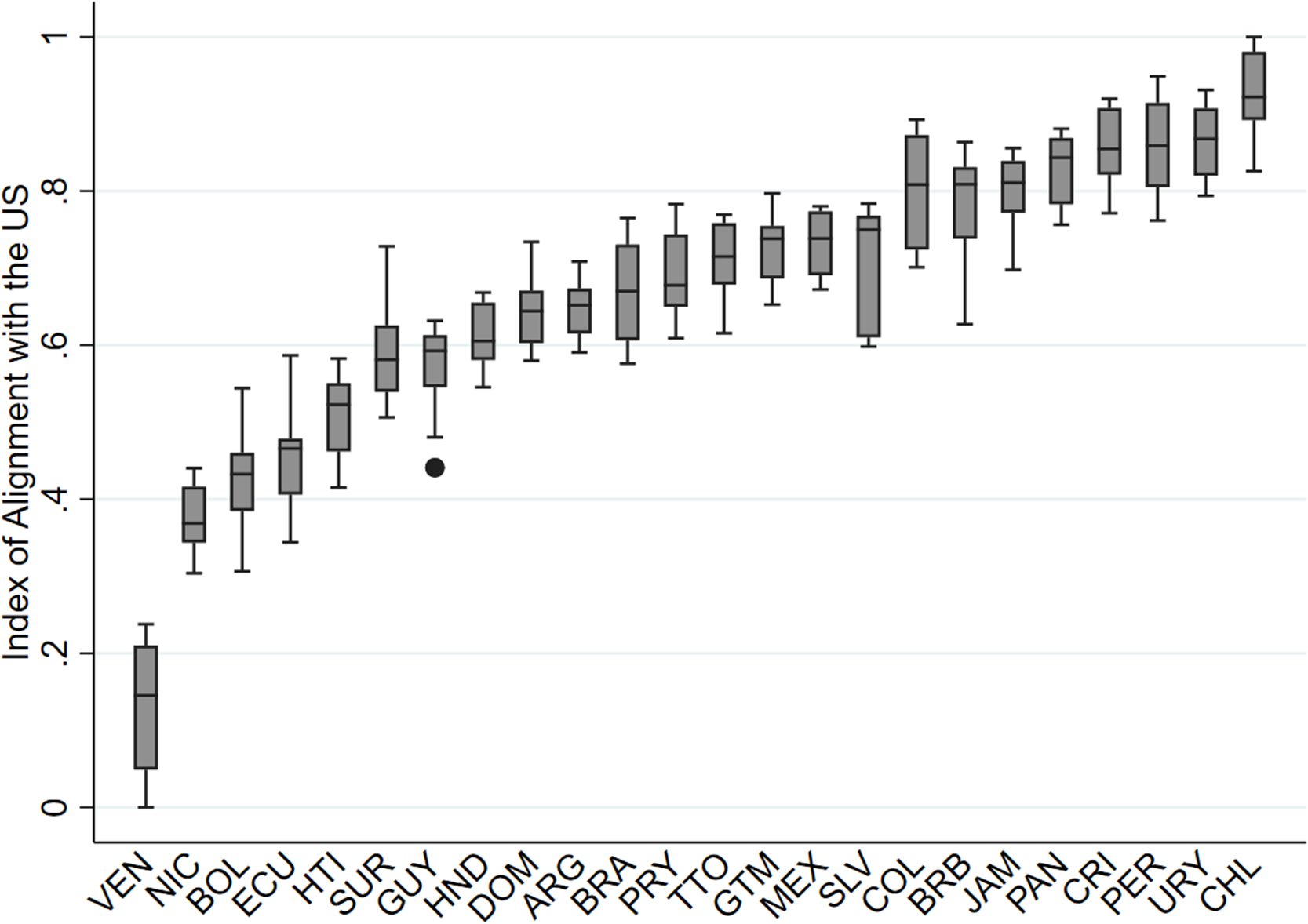

Regarding our intervening variable, we built an index to measure Latin American and Caribbean countries’ alignment with the United States, following other examples in the literature (Urdinez et al. Reference Urdinez, Mouron, Schenoni and de Oliveira2016). Our index includes the level of democracy, the respect for market economy principles, and the proximity of voting in the United Nations General Assembly, as proxies for the countries’ preferences on domestic politics, market economy, and the US-led international order. In order to measure the three aspects, we took the level of democracy from the Electoral Democracy Index of Varieties of Democracy; the Economic Freedom Index of the Heritage Foundation; and the annual reports on Voting Practices in the United Nations from the Department of State, where they provide the voting coincidence of each country in the world for important issues. With these three proxies, we created a composite index using dynamic principal component analysis (PCA), a useful technique for reducing dimensionality in large amounts of data. In order to simplify its interpretation and its inclusion in the regression models, we normalized the index between 0 and 1 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Distribution of Scores of Alignment with the United States.

In order to test our hypothesis, we include an interaction term between each indicator of economic engagement with China and the index of alignment with the United States to capture how they operate together. If our hypothesis is correct, all interaction terms should be positive and statistically significant, indicating that the effect of a greater economic engagement with China on the allocation of US foreign assistance increases along with the alignment to the United States.

The model also incorporates other predictors commonly used as drivers of official foreign aid. First, we control for the level of development, measured by the GDP per capita, using data from the International Monetary Fund. Second, we consider the relevance of exports to the United States, as a percentage of GDP. Third, we include fixed effects by subregion. Finally, we include a lagged dependent variable as a predictor to control for autocorrelation. Additionally, all predictors are lagged by one year in relation to the dependent variables to control for inverse causality.

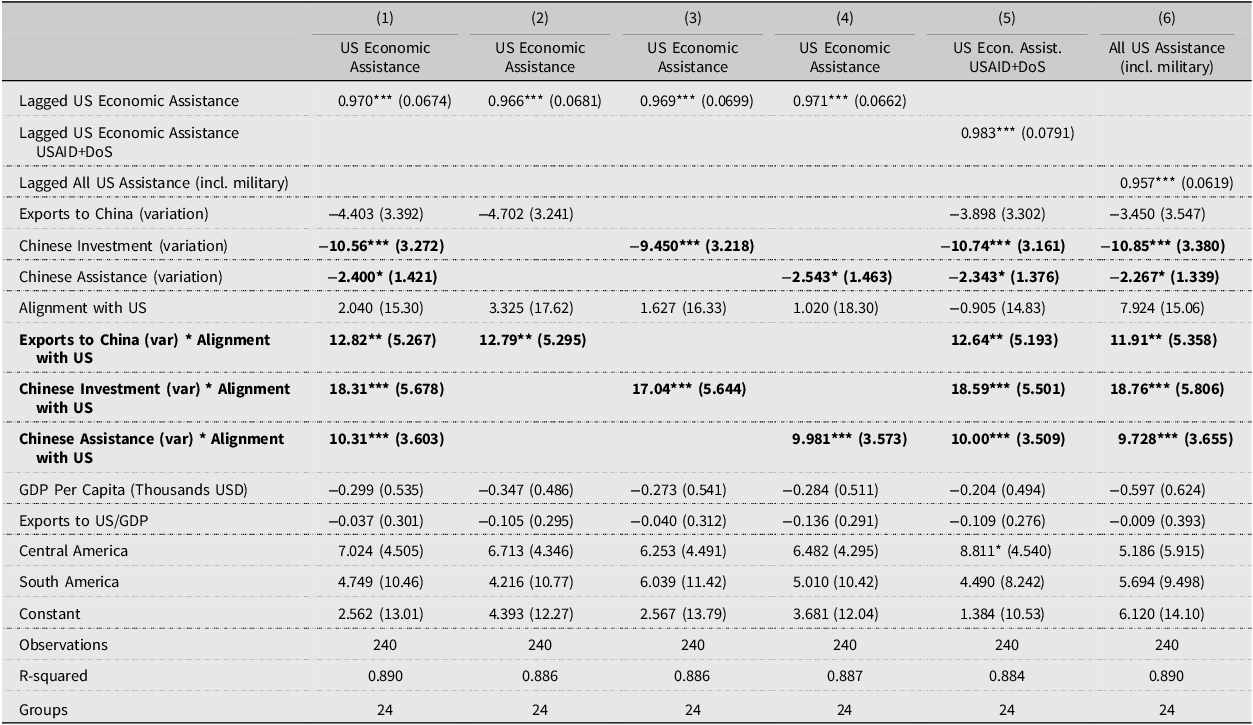

Results of the regressions are presented in Table 2. Models 1 to 4 use the annual US economic disbursements as dependent variables, but they differ in their specifications. Model 1 is comprehensive, including all three indicators of economic engagement with China. Models 2 to 4 include only trade, investment, and development assistance variations, respectively. Both Models 5 and 6 encompass all predictors, but they test different dependent variables. The former uses economic disbursements made solely by USAID and DoS, while the latter includes both economic and military assistance.

Table 2. Regression Outputs

−***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Standard errors ————— in parentheses. All predictors are lagged.

Coefficients for the main independent variables, meaning variation in trade, investment, and development assistance by China, estimate the effect of increasing economic engagement with China when alignment with the United States equals to 0. Predictably, all coefficients are negative, suggesting a decrease in US foreign assistance when a non-aligned country moves closer to Beijing. It should be noted, however, that results vary across indicators, as coefficients are statistically significant at a 0.01 level for Chinese investment and construction; at a 0.10 level for development assistance; and they are not significant for variations in trade.

Interaction coefficients can be interpreted as the additional change in US foreign assistance when countries exhibit the highest levels of alignment. In line with our theoretical expectations, all interaction terms present positive and statistically significant coefficients. This indicates that the impact of higher economic engagement with China on the allocation of US foreign assistance tends to strengthen with the level of alignment with Washington. Notably, interaction coefficients surpass those of the independent variables in absolute terms, implying that the negative effect of engaging with China observed in non-aligned countries is reversed in countries with a higher level of alignment. Countries that are aligned with the United States, consequently, can expect an increase in its foreign assistance when moving economically closer to China.

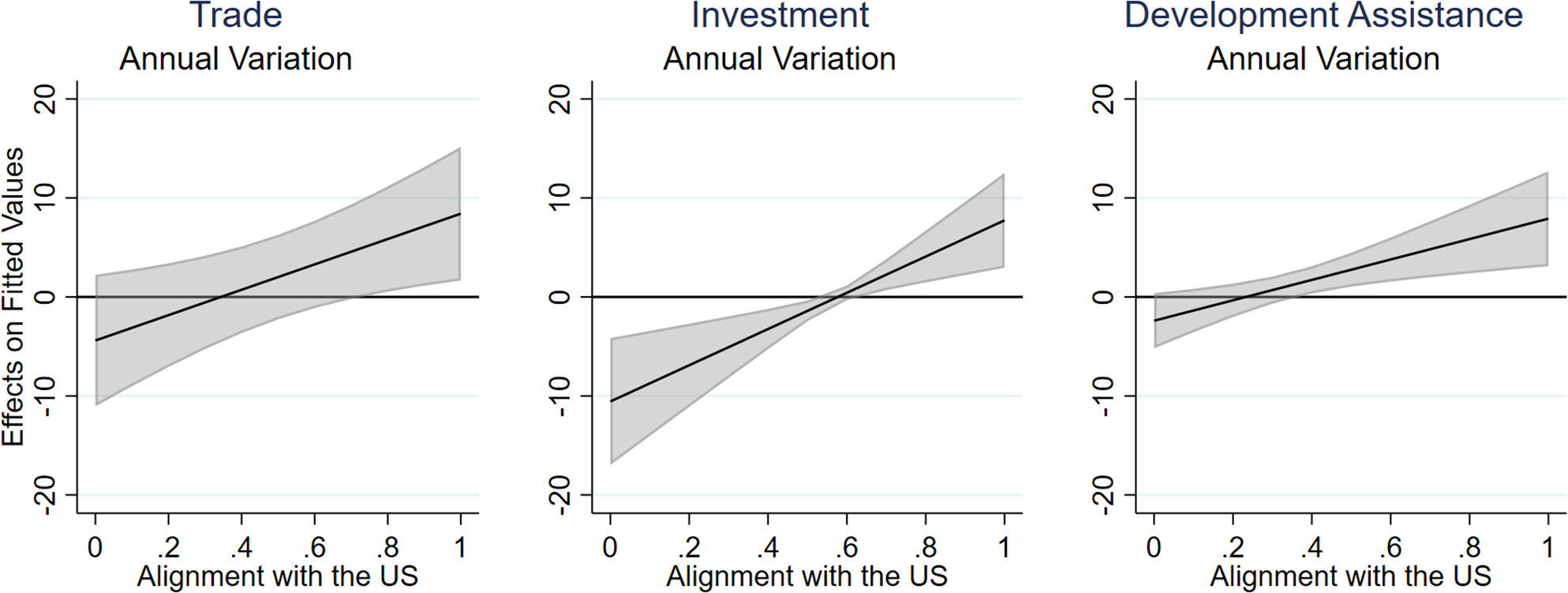

In order to fully grasp the interaction between economic engagement with China and the alignment with the United States, we also estimated the Average Marginal Effects of the former on the amount of foreign assistance received the following year. The results are depicted in Figure 5. Assuming a 95% Confidence Interval, Model 1 predicts that the effect of increasing economic ties with China on the US foreign aid obtained the following year is positive and statistically significant for countries with political and economic positions close to the United States across the three chosen indicators. These results are consistent with our hypothesis. Predictions for countries not aligned with the United States are less clear, though. Even when the predicted marginal effect is negative in the three cases, in line with our argument, only the estimated effect of investment is statistically significant in our plots, while the effect of development assistance is statistically significant at a 0.10 level, as we mentioned before.

Figure 5. Average Marginal Effects of Economic Engagement with China (95% CI)—Model 1.

Conclusions

In the context of global hegemonic competition and geoeconomic order, Latin America emerges as a significant arena for the application of economic statecraft from both China and the United States. This study has effectively illuminated the complex interplay between political and economic dynamics, by offering valuable insights into the scope conditions and salient characteristics of the implementation of carrots and sticks in the US response to Latin American countries’ economic engagement with China. First, we managed to trace how this economic presence was perceived as a direct challenge to American interests. Then, we showed how economic statecraft came out to be the chosen mechanism of response, and within it, how positive incentives were the prevailing policy choice.

Regardless of the ongoing debate concerning the novelty or rebranding of the BRI, our analysis has compellingly demonstrated how its expansion across the region, coupled with the growth of Chinese foreign direct investment and trade, led to the perception of a significant defiant situation that threatened US strategic interests in the area.

In a notable departure from conventional expectations in Latin American foreign policy discussions, for whom sanctions are the foreseeable reaction by the hegemon, our investigation has decisively shown that the predominant response to this challenge has been rooted in “carrots” rather than “sticks.” Our research adopted a mixed-methods approach to show how, in the case of democracies with non-revisionist governments, the US response was an increase in its economic engagement in the region, mainly driven by the Department of State programs. These findings corroborate existing theories that underscore the legitimacy conditions guiding economic statecraft, especially in the case of positive engagement. Regarding economic based threats, and democracies with politically aligned governments, it is more plausible for economic engagement to supersede sanctions, aligning with expectations established by academic discourse. Moreover, the observed expansion of US economic engagement in Panama under the administration of Cortizo underscores the heightened significance of political alignment among target states. Furthermore, our findings highlight the effect of third options as a mechanism to reduce vulnerability in asymmetric interdependence, dissuading the application of sanctions. “Sticks” were seldom employed and primarily manifested as threats rather than actual disruptions of economic flows. Our data shows that these threats were implemented to influence specific policy change decisions. In contrast, “carrots,” encompassing both promises and payments, emerged as the predominant instrument for countering Chinese presence and fostering a shift in preferences.

These outcomes contribute substantially to enhancing our comprehension of economic statecraft, the intricate process between positive and negative incentives policy choices, and the broader debate surrounding Latin American foreign policy strategies vis-à-vis China and the United States. The statistical analysis results are encouraging for broader research on the twists and turns of economic statecraft in the regional dynamics; enlarging the plausibility of finding a similar pattern of carrots to that of the US-Panama relationship in other linkages in the region This underscores the necessity for empirically grounded studies that illuminate the costs and opportunities inherent in diplomatic decision-making within the geoeconomic order.