Since President Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019, Brazil has become an emblematic case of a populist leader seeking to seize the power of the state by controlling bureaucrats throughout the federal administration (Peci Reference Peci2021; Hunter and Vega Reference Hunter and Vega2022).Footnote 1 This might not surprise some observers who have assumed that Latin American states are generally weak and unprofessional, with bureaucrats who are, for the most part, mere agents of more powerful political masters (see, e.g., Geddes Reference Geddes1994; Ames Reference Ames2002). This perspective relies on a rational choice model depicting bureaucrats as tools of ambitious politicians whose own interests dictate state outcomes.

That Bolsonaro was able to exert control over the bureaucracy might therefore be expected. Yet wide-ranging empirical studies have highlighted the strength and autonomy of bureaucratic actors in relation to political actors in Brazil (see, e.g., Nunes Reference Nunes2015; Bersch et al. Reference Bersch, Praça, Taylor, Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017a, Reference Bersch, Praça and Taylor2017b; Abers Reference Abers2019; Rich Reference Rich2019; Lopez and Praça Reference Lopez and Praça2015; Cavalcante and Lotta Reference Cavalcante and Lotta2015; Bersch Reference Bersch2019; Lopez and Cardoso Reference Lopez and Celso Cardoso Junior2023). Indeed, the Brazilian bureaucracy is organized to provide expertise and stability despite turnover at the top. While there are numerous political appointee positions, many of them are reserved for career civil servants, and a strong core of meritocratically recruited civil servants enjoy robust tenure protections, especially in the federal government. Given the strength of the Brazilian federal bureaucracy, most observers did not expect the Bolsonaro government to succeed.

During its first few months in office, the chaotic new administration seemed outmatched, but over the next few years, the Bolsonaro government managed to defeat such resistance in many areas and impose its preferred policies (Peci Reference Peci2021; Milhorance Reference Milhorance2022). Consider the response to the pandemic: nearly all specialists expected that the public health system, Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), would fare well regardless of the president’s actions, inaction, or policies. They were wrong. Bolsonaro dismissed COVID-19 as “a little flu,” downplayed problems associated with it, sought to maintain an open economy, railed against social distancing and lockdowns, and organized large gatherings of his supporters while disparaging scientists and mask wearers.

The pandemic revealed that Bolsonaro had rendered SUS much weaker than most analysts realized. Similarly, despite strong administrative capacity and environmental activism in environmental agencies that had developed over time to protect the Amazon, the Bolsonaro administration eroded the ability of such agencies to enforce environmental safeguards. Satellite images suggest that twice as much forest was lost in 2022 as the average from January 2010 to April 2021 (Economist 2022). How? What explains this turn of events?

The conflict between politicians and bureaucrats is nothing new, of course. Weber observed that democracy needs bureaucracy as a stable authority guaranteeing the impersonal and equal application of the law (Weber Reference Weber, Gerth and Wright Mills1946). At the same time, bureaucracy can pose a risk to democracy if it corrupts democratic processes or uses institutions to its own ends. Therefore, modern democracies face a difficult balancing act between the power of politicians and weight of the bureaucracy. Many analyses explore political control, but the bureaucracy has increasingly been an arena of contention in states governed by populists.

We define political control of the bureaucracy as actions taken by political leaders, whether in democracies or autocracies, to ensure compliance with an executive’s policy preferences.Footnote 2 Political actors can exert control over bureaucrats in a variety of ways. Cases such as Hungary under Viktor Orbán offer dramatic examples of populist political control and clear democratic backsliding. The bureaucracy was one of Orbán’s first targets: he abolished the career civil service and allowed dismissal without justification, purged the upper echelons, and diminished expertise plus centralized control over budgeting and funding. Those who remained in the service of the state were cowed. Similarly, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela colonized the bureaucracy to consolidate control. Other cases of populist strategies tear at the institutional fabric of the state. In Mexico, the executive has attacked bureaucrats, forced resignations, defunded certain agencies, and closed others wholesale, although some agencies have resisted, thanks to the strength of the civil service.Footnote 3 In Brazil, Bolsonaro has stated his desire to dismantle policies and institutions associated with previous administrations. He has sought to reintroduce the power of the military within the civilian bureaucracy. In response, many public sector workers who remember the years of military dictatorship and entered the bureaucracy in democratic Brazil have sought to preserve institutions by defending civil service protections, countering efforts to marginalize public sector workers, defying threats, and resisting selective inducements.

Although efforts to exert political control of the bureaucracy may exist in any democracy, populists are particularly likely to seek to dominate the executive, due to their personalistic leadership, which rests on unbounded agency and resists institutionalization (Weyland Reference Weyland, Taggart and Ostiguy2017). Moreover, populist governments present a specific dimension of this problem because they demonize expertise, including scientists, beyond most ordinary governments, which might seek to change the content of policy without attacking bureaucrats as a class (Lockwood Reference Lockwood2018).

Strategies of control and forms of bureaucratic resistance have been analyzed by scholars. Focusing on the ways populist leaders have sought to control the bureaucracy and undermine the democracy at the cross-national level, Bauer et al. propose that politicians have three choices in dealing with the bureaucracy: sidelining, ignoring, or using it (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer and Guy Peters2021; Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019; Rockman Reference Rockman and Hill2020). Such tendencies have been countered by public sector workers who seek to safeguard the state’s ability to act in the public interest, resisting political control through subversive guerrilla tactics (Golden Reference Golden1992; Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997). Most scholars have offered static assessments of political control or bureaucratic resistance, however, to show how and why certain strategies were adopted at a particular moment. Yet strategies are flexible as well as mutable, and we see tremendous variation in the abilities of leaders to control the bureaucracy, as well as efforts by public sector workers to resist.

We argue that bureaucrats in countries with strong civil service protections and meritocratic recruitment initially have the upper hand, thanks to their expertise. New populist leaders often rely on outsiders who lack the expertise of their bureaucratic counterparts and make problematic inferences that undermine the leaders’ efforts to seize control of the state (Moynihan Reference Moynihan2022). As leaders learn, however, they are better able to calibrate their strategies by embedding political control into the institutional framework and individualizing repercussions for specific individuals, isolating them from collective and institutional support. Thus, public sector workers are induced to remain silent and implement a president’s policy preferences.

This article illustrates how populist leaders learn, evolve, and tighten their grip on the bureaucracy. Its contribution is both theoretical and empirical. It explores how learning on both sides shapes patterns of resistance and control, ultimately revealing when and how bureaucrats may reach the limits of their resistance. This theoretical framework helps set an agenda for scholarship in political science and public administration on populist leaders and bureaucratic resistance, exploring patterns of bureaucratic resistance and political control.

Drawing on an in-depth study of political control during the Bolsonaro administration in Brazil and more than one hundred interviews with bureaucrats, this article offers a process-tracing analysis of the dynamic of resistance and control. Surveys have already demonstrated that the majority of civil servants throughout Brazil’s public administration fear reporting illegal conduct within their organizations and that political interference increased during the Bolsonaro administration (World Bank Group 2021). This article’s empirical contribution is to identify causal mechanisms and processes that have led to this result and may shed light on similar cases elsewhere. This article opens the “black box” of decisionmaking within the state to reveal the actions and considerations of crucial bureaucrats as they develop plans and tactics, strive to outmaneuver political leadership, and modify their approaches over time.

Political Learning: The Dynamic of Political Control and Bureaucratic Resistance

During the last decade, in light of democratic backsliding around the world, scholars have increasingly sought to understand the ability of populist leaders to control the bureaucracy and to analyze the strategies of resistance by bureaucrats (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2020). Scholars have studied how populist leaders have sought to control the bureaucracy at the cross-national level (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer and Guy Peters2021). Authors suggest that, in certain instances, high levels of cooperation exist between technocrats and populists. Indeed, when politicians have a positive image of bureaucrats and believe they can be used to effect change, political leaders seek to gain their loyalty, capture, or empower them (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2020; Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019). When leaders view bureaucrats as barriers to their goals, however, they may decide to attack, sideline, or sabotage them (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer and Guy Peters2021).

Some strategies to eliminate bureaucratic resistance include centralizing structures and resources, politicizing staff and norms (Story et al. Reference Story, Lotta and Tavares2023), bashing bureaucrats (Caillier Reference Caillier2020), forcing new budget cuts, reducing organizational autonomy, and interfering in technical decisions (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2020; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer and Guy Peters2021; Caillier Reference Caillier2020; Hassan Reference Hassan2020).Footnote 4 These strategies may generate compliance (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer and Guy Peters2021; Gilad et al. Reference Gilad, Ben-Nun Bloom and Assouline2018).

But scholars have also documented the strategies adopted by public sector workers in attempting to resist populist authoritarian tendencies and safeguard the state’s ability to act in the public interest. Scholars have highlighted a number of strategies of counterattack, including shirking and sabotage, exit, neglect, voice, subversive action, resistance, and forms of guerrilla dissent, such as “deviant destroyers” who work clandestinely against their superiors (Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997;’ Ingber Reference Ingber2018; Guedes-Neto and Peters Reference Guedes-Neto and Peters2021). We underscore that these strategies are not static but highlight the dynamic, relational process of political control and bureaucratic resistance.

If political leaders are seeking to control the state and bureaucrats are mounting resistance, who then gains the upper hand? We know that human decisionmaking is subject to mistakes and problematic cognitive shortcuts; humans are boundedly rational (Bendor Reference Bendor2003). Researchers have applied insights from bounded rationality to political phenomena, and some have shown how bureaucrats learn from experience and an iterative, incremental approach over time (Weyland Reference Weyland2009; Bendor Reference Bendor2010; Bersch Reference Bersch2019). But political leaders can learn as well. Indeed, scholars have shown how leaders can benefit from political experience (Weyland Reference Weyland2014, Reference Weyland2021). What allows one group to outflank the other?

Long ago, Herbert Simon argued that overcoming cognitive limitations depends on expertise and collective organization, as well as the ability to break down problems into less complex parts. Whereas ordinary individuals or novices may be subject to tight bounds of rationality, constraints loosen as individuals gain experience. Over time, actors learn through trial and error; iterative attempts cultivate a sense of best responses. Moreover, dividing complex problems into smaller steps has been shown to enhance learning and expertise. Collective organizations divide tasks and foster specialization, as well as debate and deliberation, which can cross-check problematic inferences (Bendor Reference Bendor2010; Jones Reference Jones1999; Weyland Reference Weyland2014). Individuals with experience can check others, and decisionmaking can overcome cognitive limitations to become more rational. Thus, the bounds of rationality vary, given the environment (the complexity of the situation) and the computational capability of the actors, which act together, according to Simon, like “scissors [with] two blades” (Bendor Reference Bendor2003).

Our argument draws on what we know about learning over time, as well as political experience and collective organization, to understand the dynamic between bureaucratic resistance and political control. Based on this literature and scholarship exploring strategies of resistance and control, we might expect that when populists assume power, their ability to control the bureaucracy depends on the level of expertise within, and organization of, the bureaucracy. Where expertise is low and public sector workers lack strong organizations, such as unions, we would not expect much resistance. In countries with high levels of expertise (both educational and experiential) and firm organizations (e.g., public sector unions), we might expect that bureaucrats initially have the upper hand. To the extent that populist leaders take an interactive, experimental approach and rely on leaders with previous experience and expertise, as well as organizations that can break down complex tasks, we would expect such leaders to gain the upper hand, especially when they are able to transform the institutional framework and dismantle the capacity for collective organizing. Political leaders can also learn from each other by observing and applying tactics from abroad or choosing among the most successful attempts at change. Thus, we might see a dissemination of learning. In sum, we expect to find patterns of resistance and control based on the levels of expertise and ability to rely on collective organizations, both of which can vary across and within states and can change over time. The Brazilian case under Bolsonaro illustrates how this dynamic can play out and generates questions that future studies might evaluate.

Research Design

Brazil is a federal country, composed of national, state, and municipal levels, and it has undergone a recent democratic transformation since the adoption of the federal constitution in 1988. Since then, the country has made significant strides in establishing a more meritocratic and service-oriented bureaucracy. This process has led to the creation of various career paths and the recruitment of tenured civil servants based on meritocratic principles. As of 2019, Brazil had more than 11 million public servants, only 10 percent of them employed by the federal government (Atlas do Estado Brasileiro 2023).

However, it is important to note that the Brazilian bureaucracy exhibits significant heterogeneity and inequality across different levels of governance. While the national level has been successful in structuring a strong and institutionalized bureaucracy, the same cannot be said for many municipalities. Consequently, while certain regions boast autonomous and well-developed bureaucracies with extensive expertise, many others still rely on less institutionalized recruitment systems and even exhibit remnants of patronage. We therefore analyze here the case of national civil servants.

Brazilian national civil servants offer the best-case scenario for resistance because civil servants have developed high levels of expertise and collective organization, thanks to meritocratic recruitment, high salaries, and strong tenure protections (Bersch et al. Reference Bersch, Praça, Taylor, Centeno, Kohli, Yashar and Mistree2017a, 2017b; Cavalcante and Carvalho Reference Cavalcante and Carvalho2017; Lopez and Silva Reference Lopez and Moreira da Silva2019). Yet the Bolsonaro government was able to assert political control over the bureaucracy in many areas, with the country now recognized as an emblematic case of democratic backsliding (Peci Reference Peci2021). There is ample evidence suggesting that sectors of the administration have been subjected to intense forms of political control. For example, a World Bank study finds that, under the Bolsonaro administration, 56 percent of public sector workers experienced such unethical practices and political interference. Of those asked to engage in unethical practices, 65 percent were pressured by their superiors, and 18 percent of the respondents preferred not to reveal who exerted the pressure (World Bank Group 2021).

This study examines the case of Bolsonaro in Brazil and Brazilian bureaucrats, attending to the variation within state agencies to identify causal mechanisms and processes. To investigate the dynamics of control and resistance in Brazil, the research drew on more than one hundred original, semistructured interviews with bureaucrats from different organizations and sectors of the Brazilian federal government, in addition to media reports, government documents, and data from governmental and private sources.

We focus on bureaucrats who resisted the Bolsonaro administration to understand the dynamic of bureaucratic resistance and political control from their perspective. Although scholars have identified some areas within the administration with civil servants loyal to Bolsonaro’s agenda (Peci Reference Peci2021), we focus on bureaucrats who experienced political control. The resistance analyzed here includes only cases in which bureaucrats were defending the rule of law, such as the legality of decisions, constitutional rights, and democratic rules. We do not focus on resistance based on defense of individual or corporative agendas.

Given the sensitive nature of the subject, we sought to reach bureaucrats who had been subject to various forms of political control yet were still willing to participate in our research. We asked explicitly about cases in which legality and rules were under political attack. We opted to approach interviewees using snowball sampling, a method recognized by scholars as an effective way to reach interviewees when discussing sensitive issues (Cohen and Arieli Reference Cohen and Arieli2011; Cohen Reference Cohen2016). To guarantee diversity, we asked interviewees to suggest other tenured civil servants who were experiencing forms of political control and seeking to resist using strategies of voice, sabotage, or exit during the Bolsonaro presidency. Eight other bureaucrats who heard about the research also contacted us asking to be interviewed, and we included them in the sample.

The sample comprises bureaucrats of different ages (from 35 to 65) from various professions, with different degrees of expertise and organizational affiliations. In total, interviewees worked in 15 different federal organizations, including education, health, social assistance, environment, and agriculture. We finished collecting interviewees when we reached a saturation of responses, meaning that the interviews provided repeated information from diverse subjects (Henink and Kaiser Reference Hennink, Kaiser and Atkinson2019).Footnote 5

The Brazilian State and Political Control of the Bureaucracy

All presidents seek to control the bureaucracy to a certain extent, and some control is typical. During Dilma Rousseff’s presidency from 2011 to 2014, for example, bureaucrats interviewed recognized a high degree of centralization as Rousseff shifted responsibility to technicians close to her inner circle. As her political support eroded and the economic situation deteriorated, however, she lost control; budgets were slashed, and she was pressed to appoint officials from parties not previously aligned with the government, creating a “schizophrenic government” (I18 2021) characterized by a lack of policy alignment and high fragmentation.Footnote 6

Michel Temer, President Rousseff’s vice president from 2011 to 2016, assumed the presidency in the wake of her impeachment. Interviewees noted that strategies of political control increased markedly under Temer, who compiled a “red list” of bureaucrats in high or midlevel positions in agencies that mattered most to his key policies. Temer removed red list bureaucrats in priority positions while leaving in office many working in less strategic places (I9 2021). While Temer’s red list is an extreme example of political control, Dilma, Temer, and previous Brazilian presidents all made changes to the budget, personnel, and scope of authority of the bureaucracy, plus intervened in agency decisionmaking and processes.

We focus on populist leaders because their antagonism toward the state fuels an effort to exert political control. Thus, dynamics of political control and bureaucratic resistance tend to be more observable during populist administrations. As we will see, Bolsonaro increased control over time by modifying his strategies and diminishing the capacity of resistance.

Political Control Under the Bolsonaro Administration

Bolsonaro had an agenda for most areas of the government, dismantling policies, processes, and procedures connected with the previous administrations. “First we have to destroy everything, have razed land,” he insisted, “then build the new country we want” (Marin Reference Marin2019). When he formed his government in January 2019, he proposed withdrawing support for a variety of policies and programs related to human rights, minority groups, science, the environment, health, and education.

Even while recognizing his radical positions, many bureaucrats believed that they could withstand the assault. “We thought that things could not be worse,” one explained. “We expected the democratic institutions would be able to stop him” (I87 2021). Another noted that “when Bolsonaro entered the government, we bureaucrats were still strong. We knew he brought people with no qualifications into the government, who knew nothing about the state and its processes, and who would depend on us to make the machine work” (I25 2021). Initially, bureaucrats resisted changes using the same strategies they had deployed under Temer’s administration: voicing complaints at demonstrations, as well as in letters and articles, while shirking certain duties. Bureaucrats reported that shirking was a way for them to stay in their jobs without advancing the government’s agenda. As one explained, “Now I pretend I’m working, that I am reading stuff, attending meetings and webinars. But I just want to stay low profile” (I21 2021). Another admitted, “I just look for an agenda that doesn’t attract so much attention, so I can stay quiet during this period and not get engaged in the president’s agenda” (I35 2021).

At first, bureaucrats were able to outmaneuver the Bolsonaro administration, sabotaging unethical policies or making under-the-table agreements with organizations working against the governmental agenda. As one explained, “At the beginning of the administration, we still had the freedom to count on companies and NGOs, as nobody was looking at us, and this allowed us to continue our work for a while” (I88 2021). Some sent reports to organizations that could sue the government, wrote anonymous articles, or participated in clandestine meetings. “I continued to participate in secret meetings of international organizations that the government banned,” one admitted (I86 2021). These efforts relied on leveraging existing connections with outside actors.

Bureaucratic resistance was effective especially because the Bolsonaro administration was initially disorganized and left many of the approximately 25,000 political appointee positions vacant. Moreover, during the first two years, the government was unable to establish a coalition, and as a consequence, unable to pass legislation to implement the Bolsonaro agenda. Thus, the administration was constrained not only by existing legislative statutes but also by personnel in the government, including many of the former president’s appointees. This slapdash start helped the bureaucracy to gain the upper hand, because bureaucrats could leverage their expertise in governing and collective organizing.

The new administration learned from these experiences, however, and soon developed new tools that rendered the bureaucratic resistance strategies ineffective. Officials recalibrated their approach. Over the course of the next year, the Bolsonaro administration iteratively—if unevenly—improved its tactics of bureaucratic control. Tactics were developed, applied, and improved in some agencies more quickly than others. The environmental ministry (comprising several different agencies) was the first to experiment with a new set of methods meant to transform the institutional framework to control public sector workers. Many strategies developed in the environmental agencies were disseminated across the rest of the administration over time.

Civil Servants in Environmental Organizations

During the campaign, Bolsonaro made clear that he favored deregulation and preferred agricultural development over environmental protection. The president vowed to pull Brazil out of the Paris climate accord, dismantle the Ministry of Environment, end the “industry” of environmental fines in Brazil, and reduce the extent of protected areas (Bolsonaro Reference Bolsonaro2018). In the first year, the government cut 95 percent of the budget for the National Policy on Climate Change and more than 20 percent of the budget of the inspection programs.

When Ricardo Salles was appointed minister of the environment, heading the principal ministry encompassing the other agencies, many in the environmental agencies thought they could still resist political control. Bolsonaro made public speeches disparaging the capabilities of the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) and issued public threats against the environmental agencies, insisting that he would arrest all environmental bureaucrats: “These people from the environment … if one day I can, I’ll confine them to the Amazon” (Andrade and Araújo Reference Andrade and Araújo2020). These informal attacks on the collective were damaging, but public sector workers were at first resilient and resourceful. Interviewees indicated that in the past these agencies had allowed criticism and debate, regardless of the government, so they believed they would be able to continue their work to preserve the environment. Indeed, as an interviewee explained, “Initially, we believed that the minister [Salles] wanted to do something technical because they kept some analysts in their positions” (I20 2021).

Contesting the Legal Framework

To resist changes that would weaken environmental protection, civil servants frequently drew on their knowledge of laws, rules, policies, and procedures. After all, the institutional framework of the environmental agencies had been developed to enforce the laws against deforestation and protect the environment. In the beginning, for example, bureaucrats used legal procedures as cover; government officials had yet to understand such policies, so struggled to work around them. One interviewee explained, “The law was in our favor. They did not know the procedures, and it was easy for us to say, ‘You cannot do this; the rules do not allow you to.’ They used to be afraid” (I49 2021).

Many interviewees acknowledged that because the administration did not yet know how to operate the levers of power, they used the legal framework of environmental protection to shield their efforts to protect the environment and carry out the law. “In 2019, when the new manager came in, I was in another department,” one recalled. “Every month they changed the chiefs. We were on standby, doing nothing. Because the people who arrived didn’t know the process, anything. And we didn’t want to help either, that was my way of imposing limits” (I33 2021).

Over time, however, the government learned and developed new practices, which diminished the capacity of bureaucratic resistance and increased political control. New tactics to undermine resistance emerged, which counteracted the civil servants’ use of law, rules, and guidance documents; the Bolsonaro administration started to change the legal framework itself. Minister Salles, a lawyer who had served as state secretary of the environment of São Paulo from 2016 to 2017, had previous experience with such resistance and deployed a number of tactics: infralegal change to the institutional framework; censorship processes; and the creative use of human resources to oust opponents (Souza Reference Souza2020).

One significant aspect of Salles’s approach was the effort to make legal changes to nonstatutory rules. Although most administrations make important changes at the beginning of a president’s term via executive decree and other types of regulation, Salles’s use of infralegal change was a new approach. Such infralegal changes typically involve changing the legal opinions or guidance documents to reorient the intent of existing laws and normative documents or their implementation. Drawing on his expertise as a lawyer, Salles sought both to transform rules not passed by Congress—and in Brazil, a great deal of the legal framework rests on agency policies, executive decrees, and the like—and to eviscerate the agencies’ ability to enforce the legislative statutes through such an infralegal process. Even the application of the strictest environmental legislation was weakened by the minister’s ability to repurpose, reinterpret, or suffocate the implementation of such laws.

This approach to swift environmental deregulation and dismantling of the environmental agencies from the inside was detailed by Minister Salles himself at a meeting of ministers on April 22, 2020, which was videotaped. Although the government sought to prevent the video from being made public, Supreme Court Chief Justice Celso de Mello allowed its release on May 22, 2020. Offering an unprecedented view into the inner workings of the Bolsonaro administration, the video reveals that during the cabinet meeting, Minister Salles argued that “in terms of press coverage, we are at a good moment, because COVID-19 is the only thing they talk about, and we need to push through changes [ir passando a boiada, literally push the cattle through].” This term, push the cattle through, originally described the hurried rounding up of cattle to get them across a river quickly. In this context, Salles seems to refer to deregulation, intending to enhance development in a protected region. Salles continued, “There’s an enormous list of things we can simplify in all the ministries that have a regulatory role. We don’t need Congress.” (Polícia Federal Reference Federal2020; see also O Globo 2020). He explained the strategy: “parecer, caneta; parecer, caneta” (legal opinion, signature; legal opinion, signature).Footnote 7

Interviewees recognized that the Salles administration “learned to lean on a new legalism. They do what they can now within the laws, even if it’s a different interpretation of the law” (I56 2021). This type of legislation relies on the executive’s extensive rulemaking powers and does not require congressional approval (Guimarães de Araujo Reference Guimarães de Araújo2020). A report by the Brazilian Climate Observatory (Observatório do Clima) highlights that the administration accelerated deregulation and rule changes in an infralegal way, moving to nonstatutory legislation (decrees, orders, norms, acts, and wide-ranging regulations that exist in Brazil) and working around the law (e.g., breaking up highway projects into smaller parts so they did not require the same environmental reviews) (Werneck et al. Reference Werneck, Sordi, Araújo and Angelo2021). In the environmental agencies, more than six hundred important regulatory changes were implemented, many of which only required the minister to sign (Werneck et al. Reference Werneck, Sordi, Araújo and Angelo2021). Such a transformation limited the formal scope of authority. Environmental bureaucrats had previously been able to fine individuals for legal infractions, for example, but were now required to obtain authorization from a committee of political appointees—most from the military.

To blunt the effect of individuals’ denouncing what was happening in agencies, Minister Salles institutionalized censorship. The first effort to prevent information from becoming public began in March 2019, when the administration officially prohibited officials from the Ministry of the Environment (Ministério do Meio Ambiente) from giving interviews or publishing documents. The same act was applied to IBAMA, the agency charged with monitoring and fining violations of Brazil’s environmental law, as well as the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio). In this way, Salle pushed through legal changes to embed political control in the institutional framework.

Collective Resistance, Military Appointments, and Individual Attacks

In response to these strategies, many civil servants sought to work together as a collective to fight back. “We decided to protect ourselves from political persecution collectively,” one noted. “The idea was: if it’s to pick a fight, they’ll have to do it against the whole team. And that helped us, it worked well” (I25 2021). As another recounts, they faced new challenges: “Once a colleague was forbidden by our chief to put any information in the system, as they didn’t want any decision to be formalized. The chief threatened her if she included any new information.” Bureaucrats relied on challenging political decisions in concert. “The other day, we all decided to do the same and included her information all together. So, if they wanted to punish someone, they had to punish all of us together. This is how we gave them the message that we were not alone” (I22 2021). In this as in many other instances, bureaucrats learned that banding together and drawing on collective organization allowed them to avoid punishment for resisting changes to established institutional procedures and protocol. As a report by the National Association of Environmental Civil Servants regarding Bolsonaro’s dismantling of environmental policies states, “mess with one, mess with everyone.” (ASCEMA 2021).

In response to the collective action, the Salles administration shifted its approach, moving from attacks on the collective to attacks on individuals. Notably, the silencing approach was expanded and modified to target particular people rather than entire agencies. In May 2020, civil servants from the Ministry of the Environment and other environmental agencies were prohibited from posting on their own social media sites. Coupling collective censorship with individual silencing proved effective in undermining resistance. Whereas censorship of an entire agency might be met with a collective response, individual attacks isolated people from each other and reduced their ability to organize in response. That is, attacking an entire agency’s legitimacy does not prohibit civil servants from continuing their work; however, individual attacks are very effective in causing damage to civil servants individually and creating an environment of fear (Lotta et al. Reference Lotta and Ianna Lima2023).

Interviewees reported other informal means of reducing the ability to act collectively: “They changed the layout of the rooms, they opened everything, everybody together, no walls, glass,” one official shared. “So everyone is looking at each other. And then they put all the political appointees in another room where they can see us, but we don’t know what they’re doing” (I36 2021). When “they started taking individual action, acting on each of us individually,” an official explained, “we lost the control and the capacity to react” (I38 2021).

This strategy follows a pattern that Salles developed in São Paulo, where he opened investigations of civil servants to generate fear and pave a path for prosecution (Souza Reference Souza2020). These strategies were replicated at the Ministry of the Environment. The administration removed civil servants from appointed positions and replaced them with lawyers or military officials. Salles also appointed Bolsonaro’s allies and military officials throughout the agencies to key strategic positions such as directors, heads of departments of local agencies. While efforts to appoint loyalists are common, appointing military officials to those positions throughout the agencies was a novel approach. The same individual who acknowledged that Bolsonaro seemed to be doing “something technical” later saw “that intention proved to be a lie. Actually, they were trying to learn how to do the job, and they needed the technical bureaucrats to teach them. After that, they’ve been replacing everybody with outsiders that implement the minister’s agenda, especially the military” (I20 2021). Another interviewee explained, “They started to put in several lawyers. There was even a new lawyer coordinator who was the wife of a military man. And then it started to get harder for us. I tried to go head-to-head against some positions, I started writing technical reports to document everything. But after a while they decided to remove me from there (I18 2021).”

The strategy of replacing personnel, especially with military officials, soon extended across the decentralized units and participatory councils, which had enjoyed a degree of bureaucratic autonomy. Regional managers at ICMBio were soon replaced by officials with military experience. Salles reduced the command structure of regional managers from 11 to 5, “steps that erase[d] the institutional memory of environmental protection agencies” and ensured more centralized control (Menezes and Barbosa Reference Menezes and Barbosa Junior2021). Military officials increasingly filled the upper echelons of the ministries and were distributed in low-profile positions where they could significantly influence the capacity for control. For example, military officials came to assume more than 90 percent of mid- to high-level positions (Menezes et al. Reference Menezes, Mello and Couto2021). By incorporating people and procedures from the military, the government strengthened its control and guaranteed greater loyalty while experimenting with different forms of political control.

The president then used decrees to extend the use of the armed forces on the border, throughout Indigenous lands, and in federal units of conservation in nine states encompassing the Amazon (Decreto 512 10.234/2020; Decreto 10.394/2020). He also weakened the autonomy of two key participatory councils by using decree power to alter their composition. In the case of the National Environment Council (Conama), he slashed the number of members from 96 to 23 and decreased civil society seats from 23 to 4, chosen by lottery. The National Council of the Legal Amazon was shifted to the purview of the vice president without the participation of representatives from IBAMA or ICMBio. Installed on the council were 5 colonels, 1 general, 2 major brigadiers, and Bolsonaro’s vice president, Hamilton Mourão, as council president. Indigenous peoples and other traditional communities in the region were excluded (Tajra Reference Tajra2019).

The Salles administration also repurposed existing rules and procedures. Consider the application of the administrative disciplinary process (PAD), applied when civil servants have reportedly broken the law. When a disciplinary process is filed against a public sector worker—even without much evidence—a civil servant needs a lawyer, causing time, money, and hassle; dismissal is a real possibility. At first, the administrative disciplinary process was used as it had been under previous administrations. Over time, however, the Salles administration began an iterative process of repurposing PAD to harass and dismiss employees.

In a meeting with rural supporters in the state of Rio Grande do Sul in April 2019, Minister Salles threatened civil servants with the opening of a PAD for their absence at the event, even though they had not been invited. This instance prompted the president of ICMBio to resign, and in the days following, all the directors of the organization likewise resigned—only to be replaced by military police officers from the state of São Paulo (Éboli Reference Éboli2019).

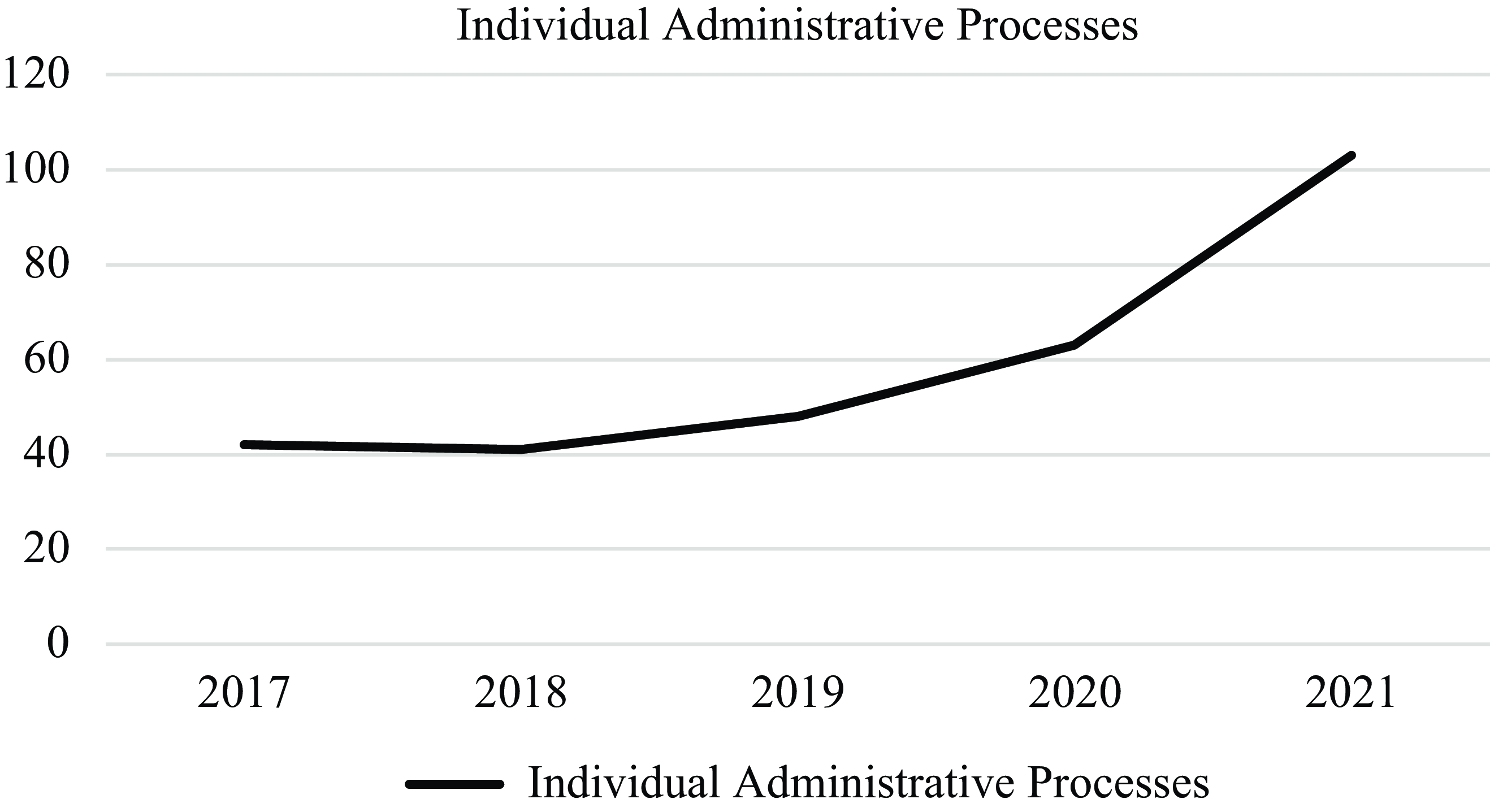

The administration learned, over time, just how effective administrative disciplinary processes could be against civil servants. The number of cases brought against public sector workers in the Ministry of the Environment steadily increased: from 2019 to 2021, disciplinary cases more than doubled (figure 1). In 2021, 103 new cases were created.

Figure 1. Administrative Disciplinary Processes (PAD) in the Ministry of the Environment

Source: The Federal Comptroller: Portal of Internal Affairs, compiled by authors.

The increase in disciplinary cases created an environment of fear. Bureaucrats felt that they were being closely watched, so that any action could trigger a disciplinary proceeding. “There is a threat in the air that you can receive a PAD for anything you do,” one confessed (I19 2021). “We keep all the time taking care of what we do, of what we think” (I23 2021). Another stated, “I never received a PAD, but it seems that things are veiled, and you are watched all the time” (I35 2021). In some organizations, bureaucrats were removed from their positions with no explanation. As one bureaucrat said, “We are now terrified of being sent to the Human Resources Department” (I42 2021). In 2020 alone, 10 percent of the civil servants in the Ministry of the Environment left.

The political control in the environmental agencies had its desired effect. This selective, incremental, legal harassment effectively silenced public sector workers. Dismantling the capacity for environmental oversight increased deforestation, forest fires, and land conflicts. Despite a strong legal framework for environmental protection and a bureaucracy that was able to resist political control in many areas, the Bolsonaro administration was able “to dismantle the environment ministry from within,” as Suely Araújo, former president of IBAMA, explained. It also dismantled the national environmental council, reducing the interference of civil society.

In sum, the environmental agencies were, in some ways, a best-case scenario for resistance, because a strong legal-institutional framework supported environmental protection, and the agencies charged with this task contained a committed core of civil servants with a strong sense of mission and tenure protections. Moreover, these bureaucrats had a strong ethos and had developed, historically, many practices of institutional activism (Abers Reference Abers2019). They also had developed extensive capabilities to reduce deforestation over time, and numerous departments were charged with discrete tasks, such that decentralized units worked with a degree of autonomy.

Under the Salles administration, however, the dynamic struggle between bureaucratic resistance and political control tilted in favor of Salles. Initially, civil servants used the law to protect actions aligned with their mission, but the administration countered by reshaping the legal framework, including rewriting regulations and transforming the infralegal landscape. Censorship laws limited reporting, prompting civil servants to unite in collective resistance. In response, the administration shifted tactics to target individuals, suppressing agency and collective dissent. Coupled with centralized human resources control, this facilitated the systematic replacement of civil servants with military officials. In cases of resistance, bureaucrats faced harassment, trumped-up legal charges, or were relegated to insignificant roles, illustrating a strategy to stifle opposition and assert control. Many interviewees reported that after the death of Bruno Araújo Pereira, a former government official who was an environmental and Indigenous activist, they were too afraid to resist.Footnote 8 One interviewee recalled entering a meeting where a military official sat down and placed a gun on the table. Isolated and attacked, civil servants had few good options left.

The Diffusion of Political Control Tactics in the Bureaucracy

Tactics iteratively improved in the environmental agencies—relying on infralegal changes, censoring agencies and individuals, controlling human resources departments—were soon applied to other areas. For example, in 2020, the publication of data from the Ministry of Health was censored. That July, the Bolsonaro administration filed lawsuits against professors at federal public universities who spoke out on social media, and the internal audit body (Contraloria Geral da União; CGU) issued a technical note prohibiting public servants from posting political positions on social networks. Although this note was later revoked in court, it left a chilling effect on the CGU’s work.

In March 2021, the administration published an IPEA censorship law prohibiting publication of research without prior evaluation of the research by political appointees. In 2020–21, civil servants at the Brazilian Communication Company (Empresa Brasil de Comunicação) were censored for broadcasting reports criticizing the government. In 2021, civil servants were censored in Brazil’s Fundação Cultural Palmares, the foundation responsible for preserving and promoting Black and Afro-Brazilian culture. Publications by Brazil’s Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (INEP), an agency connected to the Brazilian Ministry of Education in charge of evaluating educational systems and the quality of education in Brazil, were censored in 2021.

In the case of censorship, we observe the diffusion of management practices, often originating in environmental organizations, that subsequently permeated the government. How did interactive learning occur; through what mechanisms? While our evidence does not allow us to identify the exact mechanisms in all cases, the leaked video of Salles detailed above reveals a rare opportunity to observe some of them. Salles’s comments reveal a strategy that exploited the pandemic to enact infralegal modifications, not only in his own agency but also across other ministries. “We can simplify in all the ministries,” he asserts, by requiring only a minister’s signature on legal opinions. Thus, we witness him using his extensive experience in administrative law to advocate these strategies to the entire cabinet.

We also observe the Ministry of the Environment’s human resources strategy replicated across the other ministries. While our evidence does not specifically identify the environmental ministry as the originator, the similar pattern implies the possibility of either shared lessons learned or the deliberate implementation of explicit strategies. Indeed, human resources departments took on renewed importance as agents appointing military officials and other Bolsonaro allies, as well as engaging in tactics of intimidation. Human resources departments installed politicians and individuals loyal to Bolsonaro’s agenda—many from the military—throughout these institutions (Hunter and Vega Reference Hunter and Vega2022).

Under Bolsonaro, ministries and agencies were filled with military officials who applied hierarchical command structures to the bureaucracy. Bolsonaro increased by 193 percent the presence of military officials in civil positions (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2022). For example, in 2022, military officials occupied 15 percent of positions in the executive, 10.8 percent in the Ministry of Energy, 10 percent in the Ministry of Science and Communication, 8.3 percent in Environment, 7.3 percent in Health, and 4.3 percent in Education. In some organizations, including the CGU, military officials composed more than 90 percent of middle- to high-level positions (Menezes et al. Reference Menezes, Mello and Couto2021). Bolsonaro also staffed the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (ABIN) with members of the military. The agency is responsible for what the president considers sensitive issues, including compiling the lists of bureaucrats and academics monitored by the government.

The threats of administrative disciplinary processes increased, and bureaucrats became afraid of suffering individual sanctions. As one said, “I used to publish opinion articles in the newspapers, but now I don’t do it anymore as I am afraid of receiving a PAD. I can’t say what I think anymore” (I9 2021). Many left social media. “I left Facebook and Twitter,” one explained, “as we did not know who was observing us. I am afraid of everything” (I16 2021). Others reported that they were afraid that their computers or telephones were hacked. In this way, the Bolsonaro administration institutionalized and individualized attacks over time. Because the administration developed a hierarchical infrastructure of control that penetrated deep into the organizational framework, replacing human resources with military personnel, civil servants in the government had nowhere to turn to raise concerns or seek redress (Williams and Yecalo-Tecle Reference Williams and Yecalo-Tecle2020).

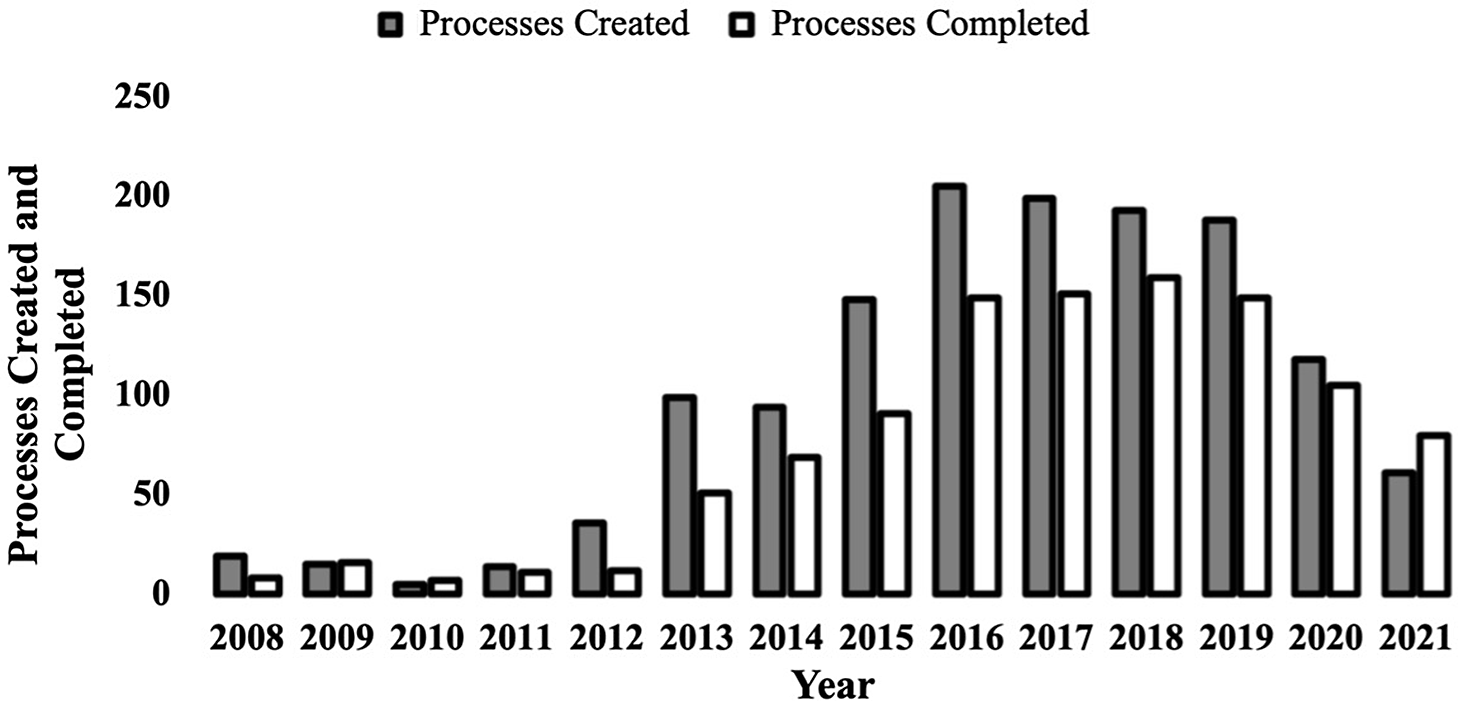

As trust in the institutions of government waned, civil servants were less willing to voice their concerns through formal institutional procedures for fear of being individually prosecuted (World Bank Group 2021; Story et al. Reference Story, Lotta and Tavares2023). Figure 2 shows the number of harassment complaints by public servants through official channels, according to the Portal de Corregedorias. In addition, a World Bank report from December 2021 reveals that 51.7 percent of Brazil’s civil servants felt unsafe reporting illegal conduct within their organizations. That procedural legality can no longer be guaranteed reveals the extent to which political control went beyond its legitimacy.

Figure 2. Formal Harassment Complaints to the Internal Audit Agency (CGU)

Source: The Federal Comptroller: Portal of Internal Affairs, compiled by author.

Targeting individuals and institutionalizing control have proven effective in generating fear and paralysis among bureaucrats, plus decreasing their capacity for resistance. These changes from informal to formal control and collective to individual attacks have increased the costs of bureaucratic resistance. The success over time in securing political control induces public sector workers to remain silent or loyal and to implement a president’s policy preferences, which, in this case, lead to institutional dismantling.

Although bureaucrats encountered limitations in their ability to resist institutional dismantling, however, the presence of checks and balances and other governmental components played a significant role in preventing numerous changes. Judicial decisions permitted or blocked certain aspects of Bolsonaro’s agenda, particularly its administrative components, and the administration’s environmental legislation faced obstacles in Congress. Ultimately, Minister Salles was dismissed; observers noted that this was largely due to the severe deforestation, which led to sanctions that left the agricultural sector unable to sell certain crops. Therefore, while the game seemed over for bureaucratic resistance, other checks and balances still existed at a higher level. These are blunt tools, however, and can be activated only after considerable devastation. By that point, substantial damage has already been inflicted.

Conclusions

When political leaders enter office, they inherit a bureaucracy and administrative apparatus filled with individuals who may or may not agree with their approach and be willing to comply with orders. This fact of governance raises questions about bureaucratic autonomy, technocracy, and principal-agent theories; the rise of populists makes such questions more urgent. Bureaucrats serve their political principals, but they are also bound to the faithful implementation of the law. When political leaders are unprincipled or breach the law, bureaucrats often serve as internal resistance.

We contend that bureaucratic resistance and political control form a dynamic power relationship. We have illustrated this dynamic in Brazil, a country where we would expect considerable bureaucratic resistance to populist tendencies, based on the strength and stability of civil service at the federal level. Nonetheless, the Bolsonaro administration exerted increasing control. This article has explained the administration’s success in controlling the bureaucracy by tracing the iterative, experimental approach the administration adopted in the environmental agencies and then applied across many areas of the government.

Evidence from Brazil suggests that political leaders strengthened the hierarchy and shifted strategies over time to isolate bureaucrats with formal mechanisms of fear and punishment. These forms of political control weakened the capacity of civil servants to protect the law and democratic procedures (Du Gay Reference Du Gay2020). We have also demonstrated how the institutional framework initially served as a means of resistance for civil servants, but that certain leaders in Bolsonaro’s administration were able to transform the regulatory framework and repurpose it to exert political control over the environmental ministries. The institutionalized procedures and rules allowed bureaucrats to resist, but when these rules were changed by executive authority rather than legislative statutes, rules became a tool of political control.

To what extent does this evidence from environmental agencies in Brazil apply more broadly? We suspect that the ability to control the bureaucracy varies considerably within and across countries, depending on factors that influence the insulation of civil servants from political interference (e.g., tenure protections, connections to powerful external groups, or budget rules). While we offer initial hypothesis-building evidence, we leave it to others to test our conclusions on other cases and in other ways.

These initial findings also have important implications for understanding the prospects for strengthening democracy after populists leave office and government. Retaining civil servants in the public sector is crucial for a country’s stability and democracy. Losing experienced public sector workers shreds the fabric of the state; the loss of expertise takes decades to rebuild, and agencies that have been gutted often remain politicized bastions of corruption for years to come. The kneejerk reaction of a new administration is often to purge anyone associated with the previous government and create new technocratic teams. But with each purge, the institutional memory dissipates and a dynamic of polarization can develop. Thus, safeguarding democratic norms and institutions requires understanding the extent of institutional damage and taking a measured approach to strengthening civil service protections by reemphasizing the importance of nonpartisanship and meritocratic appointments in the state.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mariana Costa Silveira for helping in data collection. We are grateful to Iana Alves, Olivia Guaranha, João Pedote, and Michelle Fernandez for inspiring some of the ideas of the paper, and to Daniel Thomas for research assistance. Our appreciation goes to Kurt Weyland as well as to the participants of the “Technocracy vs Politics” session at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies at Harvard University for their comments that contributed to the development of this work.