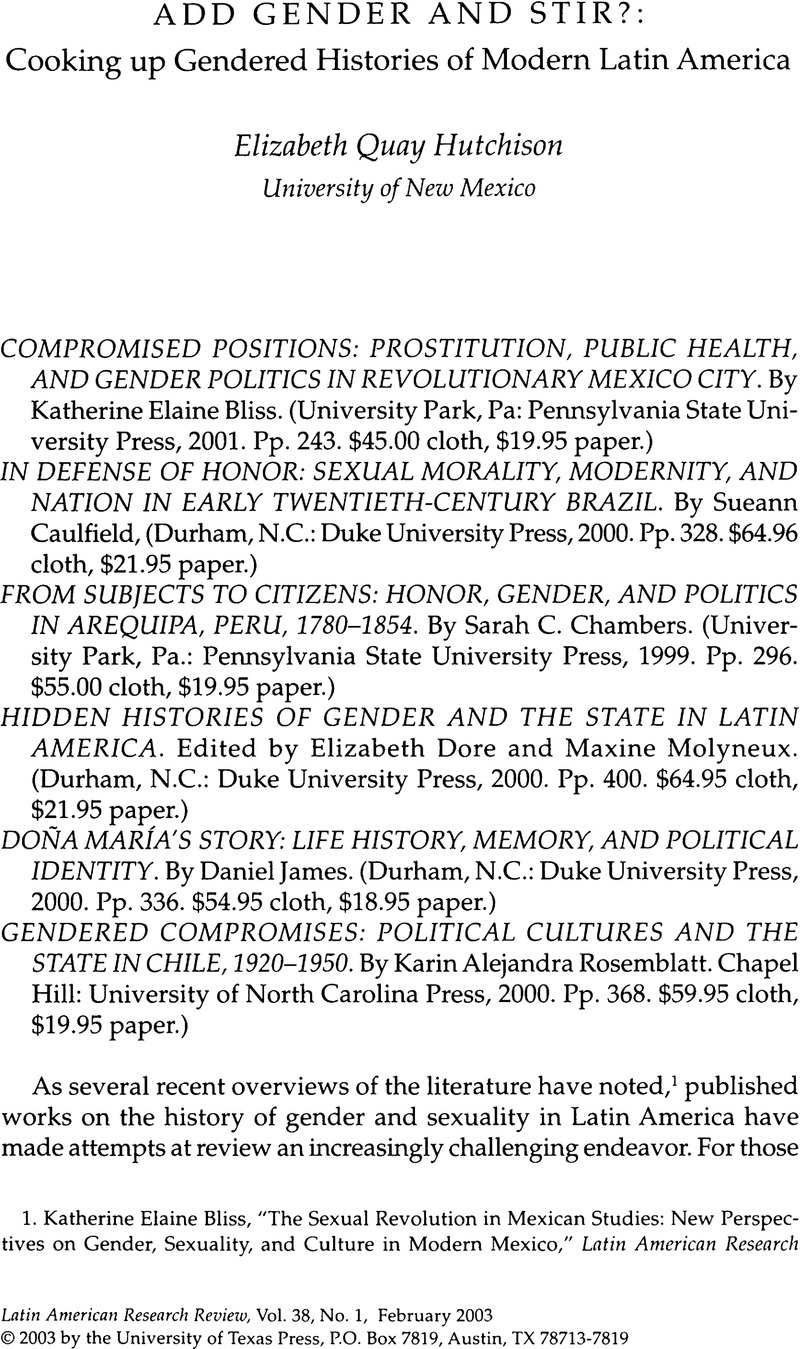

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

1. Katherine Elaine Bliss, The Sexual Revolution in Mexican Studies: New Perspectives on Gender, Sexuality, and Culture in Modern Mexico, Latin American Research Review 36, no. 1 (2001): 24768; Sueann Caulfield, The History of Gender in the Historiography of Latin America, Hispanic American Historical Review 81, nos. 34 (August-November 2001): 45190; Thomas Miller Klubock, Writing the History of Women and Gender in Twentieth-Century Chile, HAHR 81, nos. 34 (August-November 2001): 493518; Martin Nesvig, The Complicated Terrain of Latin American Homosexuality, HAHR 81, nos. 34 (August-November 2001): 689729.

2. Some of the more concrete examples of such attention include the recent catalogs of several university presses, including most prominently those of North Carolina, Duke, Penn State, and Nebraska; the special double issue dedicated to Gender and Sexuality in Latin America by the HAHR 81, nos. 34 (August-November 2001); numerous research and historiographical panels organized for the Conference on Latin American History of the AHA and the Latin American Studies Association; and the conference Las Olvidadas: Gender and Women's History in Postrevolutionary Mexico held at Yale University in May 2001. This summary does not even consider the numerous interventions of scholars specializing in gender in other venues, or attention to gender and sexuality incorporated into broader projects and research in the Latin American field.

3. Caulfield, The History of Gender. Caulfield's essay places the study of women and gender in Latin America in the context of U.S.-Latin American scholarly dialogue and the emergence of women's and gender studies in U.S. circles, emphasizing (as she demonstrates in her own work in Brazilian history) the importance of scholarship on women in development and the colonial period for the conceptualizations employed in studies of the modern period. Caulfield's essay builds on and updates a series of historiographical surveys of Latin American women's history produced since the 1970s, including Meri Knaster, Women in Latin America: The State of Research, 1975, Latin American Research Review 11, no. 1 (1976): 374; Marysa Navarro, Research on Latin American Women, Signs 5, no. 1 (1979); K. Lynn Stoner, History in Latinas of the Americas: A Source Book, edited by K. Lynn Stoner (New York: Garland Publishers, 1989), 23761. In her 1994 presentation to the Conference on Latin American History, Donna Guy was among the first to observe the significant turn towards Joan Wallach Scott's conception of gender analysis in the Latin American field; Future Directions in Latin American Gender History, The Americas 51, no. 1 (July 1994): 19.

4. Additional testimony to the dynamic state of this field is the fact that LARR received many more works than was possible to review here and, while this essay was in preparation, several important monographs have been released or are currently in press.

5. An assessment of the scholarly attention devoted to women and gender by Latin American scholars lies outside of the scope of the present review, but is critical to our understanding of the intellectual challenge faced by historians based or trained in U.S. institutions. For information on research and publication on women and gender by Latin American scholars, see Carmen Ramos Escandn, La nueva historia, el feminismo y la mujer, in Gnero e historia: La historiografa sobre la mujer, edited by Carmen Ramos Escandn (Mexico City: Universidad Autnoma Metropolitana, 1992); Flix V. Matos Rodrguez, Women's History in Puerto Rican Historiography: The Last Thirty Years, in Puerto Rican Women's History: New Perspectives, edited by Flix V. Matos Rodrguez and Linda C. Delgado (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1998); Caulfield, The History of Gender, 45051, 47375; and especially Klubock's insightful and detailed analysis of Chilean gender studies in Writing the History of Women and Gender, 493505.

6. Another fundamental element of this teleologythe pervasive argument that Colonial Latin America was rigidly patriarchal in social organizationhas also recently begun to unravel in debates on gender relations in the early period. On the one side stand a set of widely-read studies that portray colonial society as composed of multiple levels of mutually-reinforcing instances of patriarchal powerfrom individual families to the political and symbolic order of the colonythat are continually challenged, but more often indirectly subverted, by women actors: see especially Irene Silverblatt, Moon, Sun and Witches: Gender Ideologies and Class in Inca and Colonial Peru (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987); Sylvia Marina Arrom, Women of Mexico City, 1790-1857 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985); and Steve J. Stern, The Secret History of Gender: Women, Men, and Power in Late Colonial Mexico (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995). A newer cadre of colonialists have challenged this view, arguing instead that women's ability to challenge male domination was integral to social organization and royal control in the Americas, and that intensified or increased patriarchal control was rather a late colonial development that emerged only with Bourbon political centralization. See Patricia Seed, To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574-1821 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988); Lisa Mary Sousa, Women, Rebellion, and the Moral Economy of Maya Peasants in Colonial Mexico, in Susan Schroeder, Stephanie Gail Wood, and Robert Stephen Haskett, eds., Women of Early Mexico (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997); Kimberly Gauderman, Playing the System: Women's Lives in Seventeenth-Century Quito (Austin: University of Texas Press, forthcoming). Although Arrom and Stern in particular have elucidated some key aspects of gender relations for the late colonial period, this newer scholarship problematizes assumptions about the scope and operation of male domination under colonial rule, and like the works discussed here for the nineteenth century, contributes to a more historically-specific account of the relationship between political symbols, organization, and gender relations. On the need to continue reworking our understanding of patriarchy for the modern period, see Klubock, Writing the History of Women and Gender, 51018; and Heidi Tinsman, Reviving Patriarchy, Radical History Review 71 (Spring 1998): 18395.

7. The works of Patricia Seed and Ramn Gutirrez were among the first to establish the relevance of honor and shame for colonial historians: Seed, To Love, Honor, and Obey; Ramn A. Gutirrez, When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500-1846 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991). The promise of this paradigm in colonial studies was later developed further in the essays included in Asuncin Lavrn, ed., Sexuality and Marriage in Colonial Spanish America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989). The malleability and historically-specific constructions of elite and plebeian notions of honor have been further explored in Ann Twinam, Public Lives, Private Secrets: Gender, Honor, Sexuality, and Illegitimacy in Colonial Spanish America (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999); Lyman L. Johnson and Sonya Lipsett-Rivera, eds., The Faces of Honor: Sex, Shame, and Violence in Colonial Latin America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998).

8. Eileen J. Surez Findlay, Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870-1920 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1999); Sandra Lauderdale Graham, House and Street: The Domestic World of Servants and Masters in Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Kristin Ruggiero, Honor, Maternity, and the Disciplining of Women: Infanticide in Late Nineteenth-Century Buenos Aires, Hispanic American Historical Review 72, no. 3 (1992): 35373.

9. In so doing, Caulfield applies the analytical lens of gender so seamlessly that readers might be tempted to overlook the significance of her contribution to the wider field of gendered history, viewing this instead as a more traditional social and family history. In her own review of the state of the field, Caulfield demonstrates a clear preference for historical scholarship that engages withbut does not overemphasizegrand theory. See Caulfield, The History of Gender, 455, 48090.

10. Joan Wallach Scott, Gender as a Category of Historical Analysis, in Gender and the Politics of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 46.

11. Sandra McGee Deutsch, Gender and Sociopolitical Change in Twentieth-Century Latin America, Hispanic American Historical Review 71, no. 2 (1991): 259306.

12. Maxine Molyneux, Mobilization without Emancipation? Women's Interests, the State, and Revolution in Nicaragua, Feminist Studies 11, no. 2 (Summer 1985): 22754; ibid., The Politics of Abortion in Nicaragua: Revolutionary Pragmatismor Feminism in the Realm of Necessity?, Feminist Review 29 (May 1988): 11432; Donna Guy, Sex and Danger in Buenos Aires: Prostitution, Family, and Nation in Argentina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991).

13. Rosemblatt, Gendered Compromises, 14. Thomas Klubock's recent study of the El Teniente mining community draws similar conclusions about the importance of gender to the popular front project; his micro-level analysis of community relations and local politics complements Rosemblatt's national-level discussion of the popular fronts, illuminating the relative consensus between corporate and state policies, as well as popular actors' ability to reshape and appropriate elite family norms for their own ends. Thomas Miller Klubock, Contested Communities: Class, Gender, and Politics in Chile's El Teniente Copper Mine, 1904-1951 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996).

14. Ann Farnsworth-Alvear, Dulcinea in the Factory: Myths, Morals, Men and Women in Colombia's Industrial Experiment, 1905-1960 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2000); Elizabeth Quay Hutchison, Labors Appropriate to Their Sex: Gender, Labor, and Politics in Urban Chile, 1900-1930 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2001); Deborah Levenson-Estrada, The Loneliness of Working-Class Feminism: Women in the Male World of Labor Unions, Guatemala City, 1970s, in John D. French and Daniel James, eds., The Gendered Worlds of Latin American Women Workers: From Household and Factory to the Union Hall and Ballot Box (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997): 20831; Heidi Elizabeth Tinsman, Partners in Conflict: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality, and Labor in the Chilean Agrarian Reform, 1950-1973 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2002).

15. Guy, Sex and Danger; William E. French, Prostitutes and Guardian Angels: Women, Work, and the Family in Porfirian Mexico, Hispanic American Historical Review 72, no. 4 (November 1992): 52953. Several recent and in-press works have shifted the emphasis on prostitution even further away from its categorization as a discreet occupation and instead examined its ties to the structure of the labor force; normative sexuality and popular practice; and its imbrication with the structure of the family. Representative works include Findlay, Imposing Decency, chapters 3 and 6; Klubock, Contested Communities, chapter 7; Lara Putnam, Public Women and One-Pant Men: Gender and Labor Migration in Caribbean Costa Rica (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming).

16. The rise of professional social work as an arena of class relations and mechanism for increased state intervention is also examined in Ann Shelby Blum, Children Without Parents: Law, Charity and Social Practice, Mexico City, 18671940, Ph.D. Diss., University of California at Berkeley, 1998, especially. chapter 9; Klubock, Contested Communities, chapter 2.

17. Mary Kay Vaughan, Modernizing Patriarchy: State Policies, Rural Households, and Women in Mexico, 19301940, in Dore and Molyneux, eds., Hidden Histories of Gender and the State, 194214; Florencia Mallon, Exploring the Origins of Democratic Patriarchy in Mexico: Gender and Popular Resistance in the Puebla Highlands, 18501876, in Heather Fowler-Salamini and Mary Kay Vaughan, eds., Women of the Mexican Countryside, 1850-1990 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1994): 326; Las Olvidadas.

18. Domitila Barrios de Chungara with Moema Viezzer, Let Me Speak!: Testimony of Domitila, A Woman of the Bolivian Mines, translated by Victoria Ortiz (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1978); Rigoberta Mench, with Elizabeth Burgos-Debray, I, Rigoberta Mench: An Indian Woman in Guatemala (London: Verso, 1984); Mara Teresa Tula, Hear My Testimony: Human Rights Activist of El Salvador, edited and translated by Lynn Stephen (Boston: South End Press, 1994).

19. Mench, I, Rigoberta Mench; Arturo Arias, ed., The Rigoberta Mench Controversy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001); If Truth Be Told: A Forum on David Stoll's Rigoberta Mench and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans, Latin American Perspectives 26, no. 6 (November 1999).

20. Gilbert M. Joseph, A Historiographical Revolution in our Time, Hispanic American Historical Review 81, nos. 34 (August-November 2001): 44547.