Sociological research on class stratification and mobility has reemerged in Latin America. After an initial boom in the 1960s and 1970s (Reference Germani, Lipset and BendixGermani 1963; Reference Labbens and SolariLabbens and Solari 1961; Reference RaczynskiRaczynski 1972; Reference Balán, Browning and JelinBalán, Browning, and Jelin 1977; Reference Muñoz and de OliveiraMuñoz and Oliveira 1973; Reference PastorePastore 1979), followed by few developments during the 1980s and 1990s, several studies have been published in recent years (Reference ScalonScalon 1999; Reference Pastore and do Valle SilvaPastore and Do Valle Silva 2000; Reference León and MartínezLeón and Martínez 2001; Reference BenavidesBenavides 2002; Reference Torche and WormaldTorche and Wormald 2004; Reference TorcheTorche 2005; Reference SolísSolís 2005; Reference Cortés and EscobarCortés and Escobar 2005; Reference EspinozaEspinoza 2006; Reference JorratJorrat 2000, Reference Jorrat2008; Reference Costa RibeiroCosta Ribeiro 2007; Reference BoadoBoado 2008; Reference TorcheTorche 2014; Reference Solís and BoadoSolís and Boado 2016). These studies have increased our understanding of class structures and intergenerational class mobility patterns in the region.

Parallel to sociological research, economists have also developed a new interest in social class and social mobility (Reference Behrman, Gaviria, Székely, Birdsall and GalianiBehrman et al. 2001; Reference Gaviria and DahanGaviria and Dahan 2001; Reference Ferreira, Messina, Rigolini, López-Calva, Lugo and VakisFerreira et al. 2012; Reference López-Calva and Ortiz-JuarezLópez-Calva and Ortiz-Juarez 2014). There is an obvious overlap in research topics between sociological and economic studies. However, integration and cross-disciplinary efforts are scarce. This is explained in part by disciplinary differences in the theoretical approach to social class and mobility (Reference GruskyGrusky and Kanbur 2006). Most sociological studies adopt a structural approach and define social classes as groups of similar occupational positions in the labor market, under the assumption that these positions regulate access to unequal “reward packages” in a multidimensional space of resources or “social rewards” (e.g., income, social protection, power, prestige) (Reference WrightWright 1997; Reference Grusky and GruskyGrusky 1994; Reference TorcheTorche 2006). From this perspective, occupational mobility is interpreted as social mobility. In contrast, economic studies define social classes as statistical strata in a distribution of income, wealth, or other economic resources, or alternatively on the basis of patterns and levels of consumption. In the economic approach, social mobility takes place when individuals or families experience changes in their position in this distribution, across either a continuous scale or predefined thresholds that mark the limits between strata (i.e., mobility from “poverty” to “the middle class”) (Reference Fields and OkFields and Ok 1996).

The sociological approach to social class highlights the role of occupational positions as institutionalized entities that mediate between individuals and social rewards.Footnote 1 These structural foundations are obscured in the economic approach, which focuses directly on the position of individuals or families in the distribution of income, wealth, or other economic resources. On the other hand, a defining trait of the sociological approach is that the association between class membership and living conditions is probabilistic, not deterministic. Given that sociological classes are defined in the space of labor market positions, the extent of this association depends on the correlation between these positions and distributional inequalities, a correlation that is assumed by sociologists but not often empirically analyzed (Reference GruskyGrusky and Kanbur 2006), particularly in Latin America (Reference Solís and BoadoSolís and Boado 2016).Footnote 2 Members of the same “sociological” class may be located in different regions of the distribution of income or other economic resources and therefore belong to different economic strata. This characteristic is problematic for economists, who are mainly interested on directly describing inequalities in economic conditions, and therefore view the sociological approach as an inefficient method to characterize such inequalities.

In summary, sociological class analysis emphasizes the structural foundations of social positions but offers only an indirect approach to distributional inequalities. Consequently, the utility of class analysis in studies of inequality depends on the strength of the empirical association between class membership and the distribution of resources, both economic and not economic. The goal of this article is precisely to demonstrate that a sociological approach to social class in Latin America not only is relevant to characterize labor market positions and identify national similarities and differences in class structures but also contributes to understand social and economic inequalities.

To achieve this, a first step is to discuss the concept of social class and its empirical implementation in the Latin American context. In advanced industrialized societies, the Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero (EGP) class schema (Reference Erikson, Goldthorpe and PortocareroErikson, Goldthorpe, and Portocarero 1979; Reference Goldthorpe, Halsey, Heath, Ridge, Bloom and JonesGoldthorpe et al. 1982; Reference Erikson and GoldthorpeErikson and Goldthorpe 1992) has become a standard among sociologists working in the field of social stratification and mobility. This schema was developed initially for European countries but has been extensively used in other regions of the world, including Latin America. Even when labor conditions in European labor markets have deteriorated in recent decades, particularly among youth (Reference Breman and LindenBreman and Linden 2014; Reference BlossfeldBlossfeld 2008), and some Latin American countries experienced an improvement in labor conditions during the 2000s (Reference WellerWeller 2014), the gaps between these two regions in terms of the heterogeneity of productive structures and the segmentation of labor markets is still significant. Therefore, an important question is whether a class schema such as EGP is appropriate to depict the specific features of Latin American class structures.

In the next section we briefly describe the EGP schema and discuss its main limitations to characterize occupational positions in Latin America. This leads us to propose an adapted version of the EGP schema that attempts to solve these shortcomings. We use this adapted schema to conduct an empirical description of class structures and the association between social class and social conditions in nine Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, and Uruguay), including selected markers of social protection and monetary income.

The EGP Class Schema in Latin America: Limitations and Proposed Adaptations

The EGP class schema was designed to analyze the process of class formation through social mobility in Western European countries (Reference Erikson, Goldthorpe and PortocareroErikson, Goldthorpe, and Portocarero 1979; Reference Goldthorpe, Halsey, Heath, Ridge, Bloom and JonesGoldthorpe et al. 1982; Reference Erikson and GoldthorpeErikson and Goldthorpe 1992). The theoretical approach was, according to its creators, “in its inspiration rather eclectic … drawn on ideas, whatever their source, that appeared to [be] helpful in forming class categories capable of displaying the salient features of mobility among the populations of modern industrial societies—and within the limits set by the (available) data” (Reference Erikson and GoldthorpeErikson and Goldthorpe 1992, 35). In this sense, even when the influence of Marx and Weber is directly acknowledged by the authors, the resulting scheme should not be considered as a theoretical exercise but as an “instrument de travail” (Reference Erikson and GoldthorpeErikson and Goldthorpe 1992, 46), a tool for empirical research.

The point of departure is the distinction of three major class positions: (1) employers, or those who hire the labor of others; (2) self-employed without employees, or independent workers who neither buy the labor of others nor sell their own; and (3) employees, or those who sell their labor to employers. In addition to this primary division, a second major distinction is introduced among employees, between those who are engaged in labor contract or service labor relations. This separation captures the differentiation in labor relations among salaried workers in modern capitalism noted by sociologists such as Renner and Dahrendorf, between the traditional working class, composed of manual workers with labor contracts based on a short-term exchange of money for labor under conditions of direct supervision, and a service class, composed fundamentally of managerial and supervisory staff and professionals who are engaged in longer-term salaried relationships and often possess a higher degree of autonomy, some extent of delegated authority, and specialized skills.

Two characteristics of the EGP schema are particularly important for our discussion. First, the key principle of classification is the type of labor relationship. To be clear, the schema uses other characteristics (i.e., distinctions between manual and nonmanual or skilled and unskilled workers), but these distinctions are either a proxy of predominant labor relationships in certain groups of occupations or a source of secondary distinctions. Second, even when the EGP scheme was inspired on theoretical ideas, it was mainly guided by contextual and practical considerations in two major respects: an evaluation of the predominant labor relations in advanced capitalist societies and a series of empirical criteria of classification based on an “ideal-typical” association between labor relationships and groups of occupations.

We acknowledge that labor relations must be the principal criterion for elaborating a class schema, but we argue that labor relations are more heterogeneous in Latin America than in advanced industrialized nations, and therefore the “ideal-typical” association between labor relationships and occupations described by Goldthorpe and colleagues for these countries does not hold in Latin America for certain groups of occupations.

Latin American Labor Markets, Limitations of the EGP Schema, and Proposed Adaptations

Several studies in Latin America have adopted the EGP schema (Reference TorcheTorche 2005; Reference Costa RibeiroCosta Ribeiro 2007; Reference Espinoza, Barozet and MéndezEspinoza, Barozet, and Méndez 2013; Reference Solís and BoadoSolís and Boado 2016).Footnote 3 The use of this schema has been crucial to introduce the “Latin American case” to the academic discussion on intergenerational class mobility taking place in advanced industrialized nations. However, advances in comparability might have come at a high price because this schema fails to adequately capture three important sources of heterogeneity in Latin American labor markets: the distinction between formal and informal salaried workers, the heterogeneous job conditions among self-employed workers, and the conformation of a separate class integrated by economic and bureaucratic elites.

The distinction between formal and informal salaried workers derives from the important role of the informal sector in the structuration of labor relations in Latin America. There are two predominant perspectives of the informal sector (Reference Portes and SchaufflerPortes and Schauffler 1993; Reference Cortés and de la Garza ToledoCortés 2000; Reference Gasparini and TornarolliGasparini and Tornarolli 2009): the structuralist or productive perspective and the regulationist perspective. The structuralist perspective focuses on the heterogeneity in productivity levels among firms and defines informal workers as those in low-productivity firms (Reference TokmanTokman 1992, Reference Tokman1995). This structural heterogeneity was initially described by Latin American economists and structural sociologists such as Prebisch, Furtado, and Pinto (Reference Di Filippo and JadueDi Filippo y Jadue 1976; Reference Feito AlonsoFeito Alonso 1995; Reference PintoPinto 1973) as a situation in which two economic sectors coexist, one with high productivity, closer to that of advanced industrialized nations but unable to absorb the complete labor force, and the other in which productivity levels are much lower and subsistence economic activities prevail. The regulationist perspective emphasizes labor conditions and defines informal jobs as those that are not legally or formally regulated and therefore do not offer job protection and benefits (Reference Portes, Castells, Benton, Portes, Castells and BentonPortes et al. 1989).

In this article, we adopt the structuralist perspective because we are interested on highlighting the effects of Latin America’s heterogeneity of productive units on class formation and labor conditions, including the regulation of labor. Employers in the high-productivity or “formal” sector have incentives to offer relatively better wages and labor conditions, to retain the more productive labor force, reduce conflict, increase skills and, through these actions, increase productivity (Reference WellerWeller 2000, 33). In contrast, in the low-productivity or “informal” sector, labor relations are not guided by productivity demands or an interest to retain skilled or experienced workers but by supply factors and survival strategies. Labor relations are often embedded in kinship, friendship, or acquaintance ties, and salaries, job benefits, and job security tend to be significantly lower than in the formal sector.

Thus, we conceive the heterogeneity of productive units as a determinant of heterogeneous labor relations and distributional outcomes, including the regulation of contracts, access to social security, and inequality in wages (Reference Chávez Molina, Sacco, Lindemboim and SalviaChávez Molina and Sacco 2015). This association would be concealed if we adopted the regulationist perspective, because indicators of labor regulation (e.g., a written labor contract, access to social security) would be considered as a defining feature of class membership, not as a consequence of it.

The diversity in labor relations associated with structural heterogeneity is not captured by the original EGP scheme. Among salaried workers, the EGP scheme considers only the distinction between “service” and “labor contract” relations. We propose including an additional distinction between workers in formal and informal firms. This distinction is particularly relevant for manual salaried workers, but it also applies to routine nonmanual workers, and specifically to sales employees, where heterogeneity in productive units and labor conditions is higher (Reference Cortés and CuéllarCortés and Cuéllar 1990).Footnote 4

A second characteristic of Latin American labor markets is the heterogeneity in labor conditions among self-employed workers. The EGP scheme divides self-employed workers in three groups: first, the class of agricultural self-employed workers (IVc), a category originally devised to include independent farmers with relatively high productivity levels in advanced industrialized nations, but in most Latin American countries mainly comprises peasants in subsistence farming or with very low productivity levels. Second, independent professionals, who are engaged in freelance service labor relations and therefore classified in the service class. Finally, self-employed workers in nonagricultural positions (IVb).

In Latin America, class IVb incorporates a very heterogeneous mix of occupations. It includes specialized manual workers who offer their services as freelancers, but also unskilled workers in a variety of activities, such as street sales, food vending, or cleaning services, who are subject to insecure work conditions and often engage in disguised precarious salaried labor relations. Unskilled self-employed occupations of this kind have also been linked to the expansion of the informal sector, because they often represent an alternative to the absence of employment opportunities (or at least well-paid opportunities) in formal firms. We argue that labor conditions and remunerations are significantly different for skilled and unskilled self-employed workers, and therefore suggest creating a division within class IVb to account for these differences.

Finally, we propose a third distinction at the top of the EGP class scheme (class I). In advanced industrialized countries, the expansion and increasing heterogeneity of the higher service class has led some researchers to suggest a subdivision between large employers and high-level managers, on the one hand, and professionals, on the other. The arguments for this distinction have been that these two groups are engaged in different labor relations, are subject to different mobility patterns, and even present contrasting political attitudes (Reference Güveli, Need and De GraafGüveli, Need, and De Graaf 2007; Reference Gerber and HoutGerber and Hout 2004). This distinction is probably also important in Latin America, where economic and political elites not only are more privileged in economic and social conditions, but also separate themselves from professionals in patterns of social reproduction and intergenerational mobility (Reference TorcheTorche 2005; Reference Solís and BoadoSolís y Boado 2016).

As a result of the previous discussion, we introduce several adaptations to the EGP scheme. These adaptations are summarized in Table 1. First, we divide manual salaried employees (V+VI and VIIa) into groups of formal and informal workers. We propose a similar distinction for lower-grade routine nonmanual employees (IIIb), a group comprising mostly sales workers. Second, we separate skilled or semiskilled from unskilled and self-employed workers. Finally, at the top of the class structure we distinguish large employers, high-level managers, and professionals with employees from salaried and self-employed professionals. As we have discussed, this adaptation creates a separate group for economic and bureaucratic elites.Footnote 5

Table 1 Adjustments to the EGP social class schema for Latin America.

In Table 2 we present a complete version of the adapted EGP schema. The schema consists of fifteen groups collapsed into six “macro” classes: the service class, formal routine nonmanual workers, small employers and independent workers, formal salaried workers, informal salaried and self-employed workers, and agricultural classes. This schema is compatible either with a ten-class or a seven-class version of the original EGP schema, thus allowing for comparability with other studies.

Table 2 Adapted EGP schema for Latin America.

Data and Methods

We use data from household surveys conducted by national statistical offices. We defined three requirements for inclusion of countries in our analysis: the data and documentation were available to the public; the surveys were conducted in the period 2011–2015; and the surveys included sufficient information to derive the proposed class scheme as well as selected indicators of social protection and household income. Our final sample includes nine countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, and Uruguay. With the exception of Argentina, all surveys have a national geographic coverage. The appendix presents the most relevant methodological characteristics of these surveys.

The adapted EGP schema was generated using information on the respondents’ current occupation, occupational position, and size of the firm. We classified workers in the informal sector using as a proxy the size of the firm, with a cutoff point of ten workers. This approach is frequent in empirical studies adopting the productivist approach. Productivity levels cannot be assessed with standard household surveys, and previous research has shown that there is a direct link between firm size and productivity in Latin America.Footnote 6

The crossing of this information produced a comparable classification of the working population in each country according to the schema presented in Table 2. We use this adjusted EGP schema to create a map of class structures across Latin American countries.

We propose to analyze class inequalities across two dimensions: social protection and income. Most national household surveys collect information in these two dimensions. However, the specific questions and methods of recollection vary significantly across countries. To maximize the number of countries included, we restricted our analysis to a limited number of variables and indicators.

In the case of social protection, we focus on three variables: labor contract protection, inclusion in a retirement pension program, and health insurance coverage. For labor contract protection, we classified salaried workers according to whether they have a signed labor contract. In the case of retirement pensions, we identified salaried workers contributing or not to a public or private pension fund.Footnote 7 The third indicator (access to health insurance) is not restricted to salaried workers, because in several Latin American countries individuals can have access to public or private health insurance either as a job benefit or through other means.Footnote 8

As regards monetary income, we work with the household per capita income. A methodological problem is that our definition of social class is measured at the individual level, and therefore one household may include working individuals with different class positions. On the basis of previous research (Reference Solís and BenzaSolís and Benza 2013; Reference Davies, Elias, Rose and HarrisonDavies and Elias 2010), we assigned each household a class position according to the following set of rules: For households with only one working member, we assigned the social class of that member. For households with two or more working members, we assigned the class of the member with the highest monetary income. For households with no working members, we created a separate group of households with no working members.Footnote 9

We use the calculations of household income provided by the national statistical offices and included in the microdata files. There are significant methodological differences across countries in these calculations. For example, there is variation in the phrasing and scope of questions used to register the different sources of income. There are also differences in reference periods, in the inclusion of different sources of income, in the way tax deductions are managed, and in the use of explicit or implicit methods of imputation.

As Beccaría (Reference Beccaría2007) concluded after analyzing a previous round (1990–2004) of household Latin American surveys, these methodological differences may significantly affect the comparability of estimations. However, comparability problems are more likely to arise if we try to contrast absolute income levels rather than the relative position of classes in the income distribution. For this reason, our analysis is based exclusively on relative indicators of income.

The first indicator is the relative income share by social class. It is defined as the ratio of the proportion of national household income received by households in a class to the proportion of households in that same class. By definition, this ratio in the overall population is 1. A value larger than 1 indicates that a class is receiving more income than it would receive were the allocation of income proportional to its population size. Because relative income shares are adjusted both by the overall amount of income and by the size of classes registered in each country, they can be used to analyze income gaps among classes between countries.

The second indicator is relative poverty. We adopt a common definition of relative poverty and classify a poor household as that with a current per capita income below 60 percent of the overall national median income. Because median income values have important variations across Latin American countries, relative poverty should not be interpreted as an absolute measure of deprivation. Instead, it indicates that the household is located at the bottom of the income distribution, and therefore suffers a relative disadvantage compared to other households in the same country. Therefore, the proportion of households in relative poverty is comparable across social classes and countries.

Results

Class Structures in Latin America

Table 3 presents the class structures for nine Latin American countries, according to our adapted EGP class schema. Considering their similarities and differences, countries can be classified into three groups: Southern Cone countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay); Brazil and Mexico; and Central American and Andean countries (Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Peru).

Table 3 Class structure in Latin American countries, working population ages 15–64, 2011–2015.

Note: Estimates are based on microdata from national household surveys (see Table A1).

* Sample includes only thirty-one urban areas (70 percent of national urban population).

Southern Cone countries are characterized by relatively high numbers of individuals in the service class (21–24 percent) and the “administrative class” of routine nonmanual formal workers (15 percent). The proportion of salaried manual workers in the formal sector is also higher than in other Latin American countries (22–27 percent). There is also a significant number of manual workers in the informal sector (15–26 percent);Footnote 10 however, the informal sector is not as predominant as in other Latin American countries. Finally, the proportions of workers in agricultural classes are the smallest in our sample of Latin American countries (8 percent in Uruguay and 9 percent in Chile).

In Brazil and Mexico, the proportions of members of the service class (18 percent in both countries) and routine nonmanual class (12.9 percent and 9.3 percent, respectively) are lower than in Southern Cone countries. A second important distinction is that the informal sector plays a more important part in the provision of work opportunities for manual workers. Salaried and self-employed informal workers account for 24.1 percent and 29.5 percent of the working population, respectively, as compared to 19.5 percent and 18.0 percent of salaried formal workers. Finally, the relative weight of agricultural classes is also slightly higher, with proportions of 12.7 percent in Brazil and 10.8 percent in Mexico.

The class structures of Central American and Andean countries are characterized by the importance of agricultural classes (22.4 percent on average and as high as 27.4 percent in Nicaragua). Among manual nonagricultural workers, informal positions are predominant. On average, 24.6 percent of the working population is classified as informal salaried or self-employed workers, as compared to only 17.9 percent of manual salaried formal workers. In contrast, the service and administrative classes present lower expansion levels compared to the other two groups of countries.

In Brazil and Mexico, the proportions of members of the service class (18 percent in both countries) and routine nonmanual class (12.9 percent and 9.3 percent, respectively) are lower than in Southern Cone countries. A second important distinction is that the informal sector plays a more important part in the provision of work opportunities for manual workers. Salaried and self-employed informal workers account for 24.1 percent and 29.5 percent of the working population, respectively, as compared to 19.5 percent and 18.0 percent of salaried formal workers. Finally, the relative weight of agricultural classes is also slightly higher, with proportions of 12.7 percent in Brazil and 10.8 percent in Mexico.

Finally, the class structures of Central American and Andean countries are characterized by the importance of agricultural classes (22.4 percent on average, and as high as 27.4 percent in Nicaragua). Among manual nonagricultural workers, informal positions are predominant. On average, 24.6 percent of the working population is classified as informal salaried or self-employed workers, as compared to only 17.9 percent of manual salaried formal workers. In contrast, the service and administrative classes present lower expansion levels compared to the other two groups of countries.

A detailed analysis of these national differences is beyond the scope of this article. However, three preliminary conclusions are in order. First, this characterization suggests that, rather than converging into a common Latin American pattern, the current map of class structures in Latin America is highly heterogeneous. Second, the differences in class structures among the three groups of countries seem to be related to their distinctive historical patterns of capitalist development, urbanization, and labor market transformation.

Compared to the rest of Latin America, Southern Cone countries show the highest levels of urbanization, a relatively advanced development of the manufacturing and service sectors, and a historical record of higher labor market regulation. These characteristics seem to have generated more favorable conditions for the expansion of urban service and administrative classes as well as a robust formal working class.

In contrast, Central American and Andean countries present the lowest levels of urbanization, a relatively weak development of the manufacturing and service sectors, and serious limitations to the creation of high-productivity labor-market positions. Consequently, the urban service and administrative classes represent only a minor fraction of the population, informal manual positions are predominant, and agricultural classes still represent a large fraction of the population.

Brazil and Mexico, the two most populated nations in Latin America, share with the countries of the Southern Cone a history of strong domestic industrialization and later expansion of the service sector. But they are also more internally diverse in terms of their regional patterns and levels of socioeconomic development and urbanization. Their class structures seem to reflect this diversity and adhere to a pattern located somewhat in between Southern Cone and Central American and Andean countries.

The third conclusion is that, despite the national differences just described, when compared with advanced industrialized nations, the class structures of Latin American countries are characterized by two general features: the segmentation of nonagricultural manual classes in the formal and informal sector and the underdevelopment of the urban service and administrative classes.Footnote 11 These two characteristics impose structural constrains to the expansion of urban middle-income strata.

Class and Social Protection

In addition to mapping current class structures in Latin America, we have proposed analyzing the association of class membership, social protection, and relative income. In this section we focus on social protection. Two of the three variables we have proposed (access to a written labor contract and pension coverage) can be alternatively interpreted as indicators of job security or, from the opposite point of view, precarity among salaried workers (Reference WresinskiWresinski 1987; Reference De Oliveira and GarcíaDe Oliveira y García 1998).Footnote 12 In contrast, access to health insurance is a more general measure of social protection available for the entire adult population in all countries, with the exception of Brazil.

Perhaps the most severe marker of job insecurity among salaried workers is the absence of a written labor contract (Table 4). Argentina and Uruguay do not include in their surveys specific questions about access to a written labor contract. However, the high levels of salaried workers contributing to pension plans (see Table 5) suggest that the two countries, along with Chile (where 80.9 percent of salaried workers have a written labor contract), present the highest proportions of salaried workers with contract protection in the region. In contrast, these proportions are much lower in Central American countries (34.8 percent in El Salvador and 32.5 percent in Nicaragua), followed by Mexico and Peru.

Table 4 Percentage of salaried workers with written labor contract by social class, Latin American countries, working population ages 15–64, 2011–2015.

Note: Estimates based on microdata from national household surveys (see Table A1).

* Sample includes only thirty-one urban areas (70 percent of national urban population).

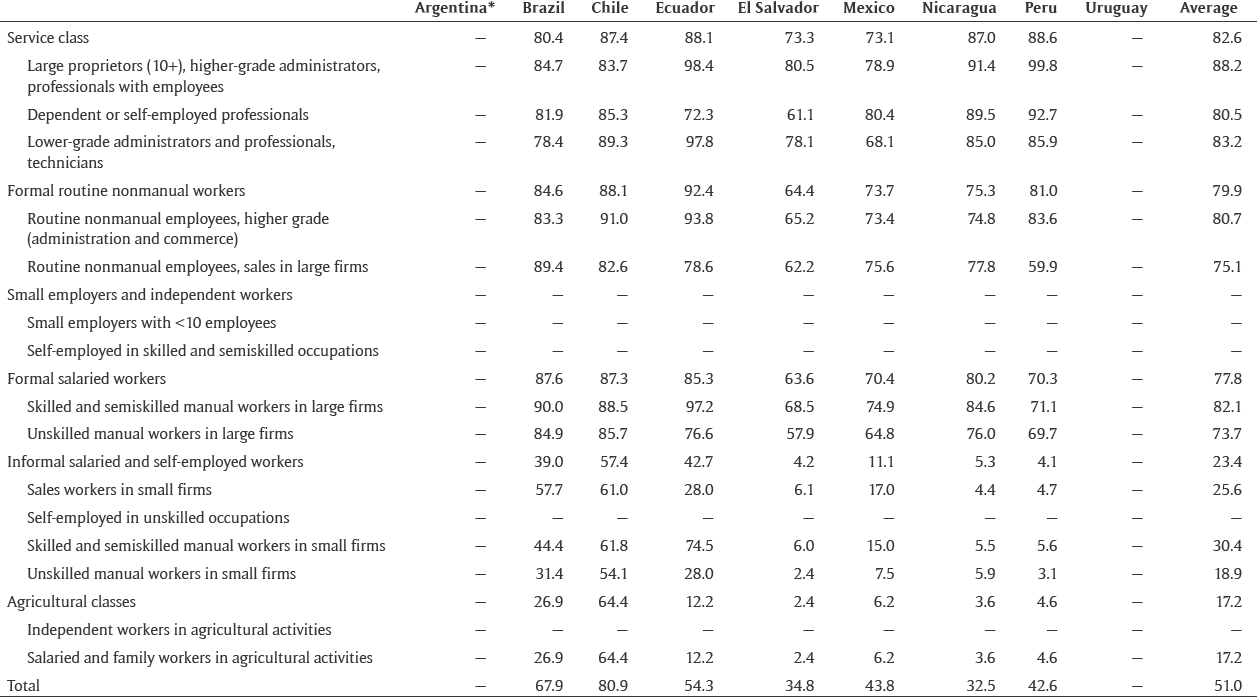

Table 5 Percentage of workers contributing to a pension plan by social class, Latin American countries, working population ages 15–64, 2011–2015.

Note: Estimates based on microdata from national household surveys (see Table A1).

* Sample includes only thirty-one urban areas (70 percent of national urban population).

What is the association between social class and contract protection? On average, the highest levels of contract protection are for the service class (82.6 percent) and formal routine nonmanual workers (79.9 percent). In the other extreme, the lowest levels are for salaried and family workers in agriculture, with an average of 17.2 percent and coverage levels under 10 percent in El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru.Footnote 13

There is a significant gap between formal and informal salaried classes. On average, 77.8 percent of salaried workers in the formal sector have a written labor contract, as compared to 23.4 percent of informal salaried workers—that is, a coverage gap of 3.3 to 1. This gap is wider in Central American countries, Peru, and Mexico, with protection levels between 6.3 and 17.2 times higher for manual workers in the formal sector. Distances are still important but smaller in Ecuador (85 percent to 43 percent), Brazil (88 percent to 39 percent) and Chile (87 percent to 57 percent).

The distinction by skill level is also important. On average, 82.1 percent of skilled or semiskilled manual workers in the formal sector had a written labor contract, as compared to 73.7 percent of unskilled manual workers. This gap in coverage, always in favor of skilled or semiskilled workers, fluctuates between 2 percent (Peru) and 27 percent (Ecuador). For informal manual workers the skill gap is more important, with coverage by a written labor contract on average 61 percent higher for skilled or semiskilled workers, and variations between 14 percent (Chile) and 166 percent (Ecuador). In sum, qualifications and skills also seem to affect the chances of access to a written labor contract, particularly in the informal sector. However, differences are of lower magnitude than those associated with the formal-informal divide.

The number of workers contributing to a pension plan (Table 5) fluctuates between 27 percent in Nicaragua and 87 percent in Uruguay. The three Southern Cone countries show the highest coverage levels, followed by Brazil (60 percent). In the other five countries the fraction of covered workers is lower than 50 percent. In addition to these national differences, in all countries there is a significant association between social class and incorporation to retirement pension programs. Again, coverage levels are higher for the service class and formal routine nonmanual workers, with averages around 80 percent, followed by salaried manual workers in the formal sector (76.2 percent). Access to pension plans is drastically reduced among informal manual workers, with 24.7 percent, that is, a coverage ratio of 3 to 1 in favor of formal salaried workers. In Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru the gap between formal and informal workers is even larger. The largest estimated gap is in Nicaragua, where only 3.4 percent of informal workers contribute to pension plans, as compared to 69.6 percent of formal manual workers. Finally, with the exception of Southern Cone countries, agricultural workers present the lowest coverage levels, with proportions below 10 percent.

In Mexico, Brazil, and Chile, where we have information of access to pension plans for small employers and self-employed workers, our results indicate that coverage levels for workers in these positions are lower in relation to other social classes. Thus, even in countries where access to pension plans is open for independent workers, effective coverage levels are low and the gap in access to pension programs between self-employed and salaried workers remains.

Finally, in relation to health insurance (Table 6), there is great variability in national health systems, in terms of both the extent and mechanisms of incorporation and the levels of segmentation within health institutions (Reference Wagstaff, Cotlear, Eozenou and BuismanWagstaff et al. 2016; Reference Cotlear, Gómez-Dantés, Knaul, Atun, Barreto, Cetrángolo, Cueto, Francke, Frenz, Guerrero, Lozano, Marten and SáenzCotlear et al. 2015; Reference Londoño and FrenkLondoño and Frenk 1997). In Brazil, Mexico, and Uruguay, public health insurance programs have high coverage levels, but the quality and effective access to services is highly segmented either geographically or according to the type of coverage (Reference Jaimes and FlamandJaimes and Flamand 2016). Other countries, such as Argentina, have lower coverage rates but offer universal access to a complementary network of public services, again with very unequal quality (Reference CetrángoloCetrángolo 2014). Additionally, in most countries affluent classes have access to private health insurance plans. This complexity deserves a more detailed analysis that is out of reach of this article. However, we can explore differences by social class using a simple variable of access to a health insurance plan (either public or private) as a broad indicator of medical protection.

Table 6 Percentage of workers subscribed to a health insurance plan* by social class, Latin American countries, working population ages 15–64, 2011–2015.

Note: Estimates based on microdata from household surveys (see Table A1).

* Includes membership to public or private plans. Does not include public health services with open access for the overall population.

** Sample includes only thirty-one urban areas (70 percent of national urban population).

*** No information available in national survey.

With the exception of Uruguay and Chile, where health insurance is almost universal (98 percent and 95 percent, respectively) and therefore inequalities reduced to a minimum, in all other countries the levels of coverage vary significantly across social classes, and particularly among formal and informal workers. Coverage levels are very similar for the service class (82.0 percent on average), formal routine nonmanual workers (84.3 percent) and formal salaried manual workers (82.1 percent). In contrast, in most countries informal workers present much lower coverage levels, with an average of 47.9 percent, similar to that observed among agricultural workers (51.9 percent). The formal-informal divide is particularly high in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Ecuador, but there are also significant differences in Argentina, Peru, and Mexico.

Class, Income Inequality, and Relative Income Poverty

We now analyze the association between social class and household income.Footnote 14 The first measure is the relative income share (Table 7). Despite the underreporting problem among high-income households, in all countries the service class absorbs the highest income shares, with levels fluctuating between 1.5 (Argentina) and 2.1 (Brazil). Within the service class, the group of lower-grade administrators, professionals, and technicians has a lower income share than large proprietors, higher-grade administrators, and professionals.

Table 7 Relative income share of household per capita income by social class, Latin American countries, 2011–2015.

Note: The social class of the household is defined as that of the principal earner among working household members. Estimates based on microdata from national household surveys (see Table A1).

* Sample includes only thirty-one urban areas (70 percent of national urban population).

Two other social classes concentrate average income shares larger than the average. One is the “administrative” class of formal routine nonmanual workers, with an average income share of 1.13. It must be noted, however, that in Chile and Brazil routine nonmanual workers present income shares similar or lower than the average, indicating that in these two countries their economic position is less advantaged and lower in relation to the service class. The other class with an income share higher than average is small employers and independent workers (income share = 1.06). A closer look shows that high relative income levels in this class are mostly explained by small employers, with income shares significantly higher than 1 in all countries, except Mexico.Footnote 15 In contrast, self-employed workers in skilled occupations present an average income share of 0.69.

In all countries, salaried workers in the formal sector, salaried and self-employed workers in the informal sector, and agricultural workers concentrate a lower proportion of income than their population size. However, there are important differences among these three classes. Salaried workers in the formal sector present the highest income share (average of 0.82), followed by workers in the informal sector (0.64), and agricultural workers (0.49). The magnitude of these gaps varies in each country, but the hierarchical ordering prevails. This pattern confirms the importance of the formal-informal-rural class divide to explain distributional inequalities at the bottom of the income distribution in Latin America.

In contrast, differences between skilled and unskilled salaried workers in the formal and informal sectors are also important, but in most countries those differences are not as large as those associated with the formal-informal gap.Footnote 16 Thus, to explain income differentials among manual nonagricultural workers in Latin America, the sectoral division between formal and informal workers is as important as the distinction usually made in conventional class schemas between skilled and unskilled workers.

Table 8 presents the percentage of households in relative poverty by social class. Because households in relative poverty are those located at the lower end of the income distribution, it is not surprising to find similarities in trends with relative shares. In all countries, the risk of poverty is higher among agricultural classes, with an average incidence of 54.9 percent. In urban settings (among nonagricultural classes), informal manual workers are significantly more likely to be in relative poverty, with an average incidence of 35.3 percent and national levels as high as 48.7 percent in Argentina and 42.4 percent in Uruguay. Within this class, in most countries the highest prevalence of relative poverty is among unskilled self-employed workers. The exceptions are Argentina and Brazil, where unskilled salaried informal workers are in a higher risk than the other groups. The prevalence of relative poverty is much lower among formal salaried workers (20.5 percent on average), and within this class, skilled workers do significantly better, with risks of poverty on average 40 percent lower than unskilled workers.

Table 8 Percentage of households in relative poverty by social class, Latin American countries, 2011–2015.

Note: Households in relative poverty are defined as those with a per capita income lower than 60 percent of the median. The social class of the household is defined as that of the principal earner among working household members. Estimates based on microdata from national household surveys (see Table A1).

* Sample includes only thirty-one urban areas (70 percent of national urban population).

Relative poverty among small employers and independent workers is on average 24.5 percent. This figure is higher than expected given the high relative share of income for this class (see Table 7). This indicates that even when the average income levels are higher in this class than, for example, among formal manual workers, there is a higher dispersion in income and a larger proportion of members of this class are at the lower part of the income distribution. This dispersion is mostly explained by the heterogeneity in incomes among self-employed skilled workers. The relative income share of this group is 0.85, slightly higher than the 0.82 of formal salaried workers, but the prevalence of relative poverty is 27.9 percent, significantly higher than the 20.5 percent of formal salaried workers.

Finally, the risk of relative poverty is the lowest among the service class (6.4 percent on average) and routine nonmanual workers in the formal sector (10.9 percent).Footnote 17 An overall view of the cross-class variation in the prevalence of relative poverty in each country indicates that in Latin America only these two social classes are relatively free of the risk of relative income poverty. At the other extreme, agricultural workers and informal nonagricultural workers (particularly those in unskilled self-employed and salaried occupations) are the most vulnerable to poverty.

Discussion and Conclusions

Two central arguments of this article are that class structures in Latin America present specific characteristics that distinguish them from advanced industrialized nations, and to draw a map of social class in Latin America and evaluate the association between class and socioeconomic conditions, these specific features must be incorporated into class schemas currently used by sociologists to study social stratification in advanced industrialized societies.

We proposed a class schema to characterize class structures in Latin America. Our point of departure was the EGP schema, created originally by Erikson and Goldthorpe for Western European societies and extensively used in international comparative research on social stratification and mobility. We preserved the key conceptual and empirical components of this schema but introduced additional distinctions specific to Latin American societies.

The most important distinction is between formal and informal workers. Latin American economies are characterized by structural heterogeneity, that is, the coexistence of a formal sector with relatively high productivity levels and an informal sector characterized by low productivity and survival activities. This segmentation implies that individuals in apparently similar occupational positions are involved in different labor relations depending on whether they belong to the formal or the informal segment of the economy.

This distinction, along with other minor adjustments, such as the subdivision of the service class and the reordering of independent agricultural workers at the bottom of the class structure, led us to propose a class schema with fifteen groups, which can be collapsed into either the traditional ten-class EGP schema or a six-class collapsed class schema.

On the basis of this adapted schema, in the empirical part of this article we used national household surveys to characterize class structures across nine Latin American countries. In addition, we obtained comparable information on social protection (labor contract, access to retirement pension plans and health insurance coverage), as well as on household income and relative poverty, to assess social and economic inequalities between classes.

We highlight two conclusions from our empirical findings. First, there is great diversity in class structures across Latin American countries, and therefore any effort to classify all countries in the region under a “Latin American class structure” might be misleading. Instead, our analysis suggests that countries can be classified in three groups: Southern Cone countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay), Brazil and Mexico, and Central American and Andean countries (Ecuador, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Peru).

Compared to the rest of Latin America, Southern Cone countries stand out by the expansion of managerial, professional, and routine nonmanual positions. Larger numbers of nonagricultural manual workers are in the formal sector, and agricultural classes represent only a minor fraction of the population. In contrast, class structures in Central American and Andean countries are defined by a much larger proportion of members in the agricultural classes, the preponderance of the informal sector in nonagricultural manual positions, and a relatively small expansion of the service and nonmanual administrative classes. Brazil and Mexico, with higher internal diversity, present class distributions with proportions located between the other two groups.

Despite the aforementioned differences, a common feature of Latin American countries is the relative small size of the service class and the class of formal salaried routine nonmanual workers. Even for Southern Cone countries, where the expansion of these two classes has been the largest, their overall share is much lower than in advanced industrialized countries.

We have suggested that the grouping of countries according to their similarities and differences in class structures might be explained by their historical paths of capitalist development, labor-market transformation, and urbanization. This interpretation, however, must be validated by additional research, which we plan to address in future studies. A detailed reconstruction of historical trends and intracountry regional differences, as well as the expansion of our analysis to a larger group of countries, could provide a more solid basis for developing a typology of class structures in Latin American countries. In addition, it is important to study whether there is an association between types of class structures and other macrosocial markers of differentiation in the region, since there is certain similarity between our grouping of countries and typologies of social policy or welfare regimes proposed by other studies (Reference Barba SolanoBarba Solano 2013; Reference Martínez FranzoniMartínez Franzoni 2006).

The second conclusion is that there is a strong association between social class, social protection, and monetary income, suggesting that class membership in Latin America is a strong predictor of social and economic conditions.Footnote 18 In most countries, access to a written labor contract, pension programs, and health insurance among salaried workers is highly dependent on their specific class position. Informal manual workers and salaried workers in agriculture are significantly more exposed to unprotected social conditions.Footnote 19 Relative income levels are lower and relative poverty significantly higher among informal salaried workers and agricultural classes. In contrast, the service class and routine nonmanual salaried workers in the formal sector experience better social conditions.

These results lead us back to our initial discussion on the differences between the sociological and economic approaches to social class. We finished this discussion with an open question about the pertinence of “sociological” social classes to study the structural foundations of social and economic inequality and poverty in Latin America. By establishing that there is a significant association between social class, social protection, income, and relative poverty, we have shown that a sociological approach to social class is still relevant to understand the relationships among productive structures, labor markets, and social/economic conditions.

An example of the pertinence of the sociological approach is its contribution to the ongoing debate about the expansion of the “middle class” in Latin America. Recent economic studies have shown that the middle class, defined as the fraction of the population escaping from income poverty, increased in Latin America during the first decade of the century (Reference Ferreira, Messina, Rigolini, López-Calva, Lugo and VakisFerreira et al. 2012; Reference López-Calva and Ortiz-JuarezLópez-Calva and Ortiz-Juarez 2014). With a different conceptual approach to social class, our analysis suggests that the low expansion of the service and routine nonmanual classes, as well as the persistence of high levels of inequality between formal and informal manual classes, represent serious structural constrains for further progress in this direction.

In sum, we believe that our proposal of an adapted class schema is a useful clarification and contributes to improve our understanding of class structures in Latin America, but at the same time creates challenges for future research. As we mentioned, it is necessary to extend our analysis to a larger number of countries. This will help validate our classification of countries in three groups and evaluate whether this classification effectively correspond to “ideal-typical” patterns of class structures. Second, our analysis is based on cross-sectional data and does not address the topic of class reproduction and class mobility. An analysis of intergenerational class mobility using the adapted EGP schema would indicate whether the proposed class distinctions are relevant to understanding the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. Finally, a third area for future exploration is the intersection of social class and other structural axes of social inequality, such as gender and race/ethnicity. We have shown that the association between social class and socioeconomic rewards is important but that at the same time there are important inequalities within social classes. An important question is whether other structural markers of social inequality can explain these intraclass disparities.

Appendix

Table A1 Data sources.

Acknowledgements

Part of this article was elaborated in the context of INCASI Network, a European project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie GA No 691004. The article reflects only the authors’ view and the agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.