Over the last ten years, Mexico and other countries in Latin America have gone through a deep crisis of insecurity (Reference Bisogno, Dawson-Faber, Jandl, Kangaspunta, Kazkaz, Motolinia-Carballo, Oliva and ReitererBisogno et al. 2014). To cope with this crisis, some individuals have reached out to their neighbors in attempts to form stable or ephemeral organizations to address their concerns about crime.Footnote 1 Although not all of these attempts have been successful, the ones that have pose a threat to the rights, lives, and livelihoods of alleged criminals, innocent bystanders, and vigilantes themselves (Reference Bates, Greif and SinghBates, Greif, and Singh 2002; Reference HineHine 1998). Just months before this piece was written, for example, two surveyors working for a polling firm were confused for kidnappers and burned alive by citizens of a small town in Puebla (central Mexico).

Given that anti-crime organization attempts can result in the emergence of stable vigilante organizations, they can represent a serious challenge to the state’s capacity to monopolize the coercive use of violence (Reference SilkeSilke 2001; Reference Weber, Garth and MillsWeber 1919). By 2014, for instance, a significant area spanning the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Michoacán (southwest Mexico) was controlled by self-defense organizations. The dominance of these organizations led journalists, scholars, and policy makers to consider the possibility of Mexico becoming a failed state (Reference GrantGrant 2014). What forces propel individuals to reach out to their neighbors in an attempt to defend themselves from crime?

In this article, I propose that when citizens distrust the effective intervention of law enforcement, their perception of the trustworthiness of their neighbors translates into an increased probability of them reaching out to other community members to defend themselves from crime (whether through prevention or control). To test this claim, I analyze the determinants of anti-crime organization attempts over several years in Mexico, using the National Survey of Victimization and Perception of Public Safety (Encuesta Nacional de Victimización y Percepción sobre Seguridad Pública, ENVIPE). The findings presented here are important because, in recent years, citizens reaching out to their neighbors in attempts to fight crime have challenged the capacity of the Mexican state to maintain social and political order.Footnote 2 These results contribute to our understanding of the state’s moderating role in society and suggest that, when the connection between citizens and the state erodes significantly, citizens turn to other actors (in this case their community) as potential substitutes for the state.

Organizing against Crime in Mexico

Neighborhood watches, communitarian police forces, paramilitary self-defense movements, and harmless anti-criminal committees are some of the types of organizations that can evolve from citizens’ attempts to address their concerns about crime. In Mexico and other countries, these organizations have introduced social uncertainty and have seriously challenged the power of the state.

In urban centers, citizens have reached out to community members to illegally close streets, set up threatening signs, and start neighborhood watches (Reference SalgadoSalgado 2014). In some neighborhoods of Mexico City, for instance, anonymous groups of citizens have posted signs promising severe punishments against thievery. In recent years, victims of crime have also turned to their neighbors to violently attack alleged criminals and police officers (Reference AlarcónAlarcón 2015).

In rural areas, citizens have turned to their communities to set up night watches, citizen-run community police forces (policías comunitarias), and other self-defense organizations (grupos de autodefensa) in an attempt to directly confront criminals.Footnote 3 In one of the most extreme examples, citizens concerned about deforestation near the town of Cherán (in the state of Michoacán, western Mexico) mobilized their community to violently confront the illegal loggers that crossed the town every day. Soon after, they formed a policía comunitaria and expelled the elected authorities from the municipality. Today, citizens of Cherán manage their own security, elect their own authorities outside the established electoral system, and abstain from participating in state and federal elections (Reference Cendejas, Arroyo and SánchezCendejas, Arroyo, and Sánchez 2015).

Similarly, tired of being extorted by drug cartels, agricultural producers from Michoacán turned to their community to start an armed paramilitary movement popularly referred to as the Autodefensas de Tierra Caliente (the self-defense movement of Tierra Caliente). This group occupied several municipalities in the state of Michoacán. It collected donations, recruited men, distributed guns, and assassinated alleged drug cartel members in the region. At its peak (January 2014), this organization controlled an area larger than the state of Delaware and seriously challenged the capacity of the Mexican state (Reference Malkin and VillegasMalkin and Villegas 2014).Footnote 4 Although these cases are extreme examples (as most anti-crime organizations only have a very local impact), they illustrate how anti-crime organization has the potential to carry with it important social and political consequences.

Organizations of this type vary in their structures, challenges, methods, and specific objectives. However, most anti-crime organizations (even the most violent and sophisticated) start from small, and seemingly harmless, individual attempts by citizens to fight crime with the help of their community.Footnote 5 Thus, without dismissing the need for nuance in the treatment of anti-criminal groups, from a dynamic perspective, it is important to understand under what conditions individual citizens are more likely to turn to their community to attempt to defend themselves from crime. Only on this basis will it be possible to understand why some of these anti-criminal attempts consolidate and diverge in different types of organizations.

The Origins of Anti-crime Organization

Although the individual origins of anti-crime organization have rarely been investigated, this is not the first time that their manifestations have been studied. Secondary (anti-criminal groups) and tertiary (violent events perpetrated by anti-criminal groups) manifestations of anti-crime organization attempts have captured the attention of social scientists for a long time. Contributions on the subject have come from a diversity of fields and can be organized into three general groups.

First, some propose understanding anti-criminal action as a manifestation of group conflict. They suggest that ethnic, political, economic, and demographic change increases citizens’ likelihood to associate with their in-group to confront threatening out-group members (see Reference Hepworth and WestHepworth and West 1988; Reference Levine and CampbellLevine and Campbell 1972; Reference Tadjoeddin and MurshedTadjoeddin and Murshed 2007).Footnote 6 Others propose that, in hierarchical communities, anti-criminal action is more likely to target crimes committed against those with high social status. This type of behavior therefore serves to restore social order (Reference BlackBlack 1976; Reference Senechal de la RocheSenechal de la Roche 2001; Reference Tolnay and BeckTolnay and Beck 1995).Footnote 7

A second group of scholars (mostly focused on vigilante groups) has argued that this phenomenon can be understood as a manifestation of institutional competition, that is, a conflict between the norms, values, and structures that preexist in specific societies and the legal framework of the state.Footnote 8 Some authors have found that vigilante organizations are more prevalent in communities with indigenous legal frameworks (Reference Owumi and AjayiOwumi and Ajayi 2013; Reference VilasVilas 2009), cultures of honor and violence (Reference ClarkeClarke 1998; Reference Hayes and LeeHayes and Lee 2005; Reference TysonTyson 2013; Reference Wolfgang and FerracutiWolfgang and Ferracuti 1967), and historically inherited security structures (Reference BatesonBateson 2013; Reference Osorio, Weintraub and SchubigerOsorio, Weintraub, and Schubiger 2016).Footnote 9

Finally, a third strand of scholarship has seen vigilantism as a direct reaction to crime and insecurity. Seligson (Reference Seligson2003) argues that fear of crime erodes citizens’ support for democracy and can increase their support for vigilantism. For their part, Ungar (Reference Ungar2007) and Smulovitz (Reference Smulovitz, Hugo Frühling, Tulchin and Golding2003) propose that vigilantism emerges as an attempt by citizens to reestablish order within their community. Finally, Huggins analyzes vigilantism as a way by which citizens defend themselves from crime in the absence of alternative resources (Reference HugginsHuggins 1991, Reference Huggins2000). Consistent with this view, Malone (Reference Malone2012), Bateson (Reference Bateson2012), Hinton et al. (Reference Hinton, Montalvo, Maldonado, Moseley, Zizumbo-Colunga and Zechmeister2014), and others have found that citizens exposed to crime directly or indirectly are more likely to support vigilante justice and other drastic control measures.

Although these studies provide a strong theoretical and empirical platform from which to investigate citizens’ willingness to engage in anti-crime organization attempts, they are not without their limitations. First, most studies have focused on in-depth investigation of specific cases. While this strategy is useful for exploring the contexts in which extralegal violence occurs, it is of limited use for investigating why some individuals are more likely than others to engage in anti-crime organization attempts. To do so, it is necessary to compare across cases.

Second, quantitative studies investigating vigilantism have largely analyzed media reports of spectacular displays of collective violence conducted with the manifest purpose of deterring or punishing crime (e.g., Reference Hepworth and WestHepworth and West 1988; Reference MendozaMendoza 2006). Although some of these events may involve anti-crime organization attempts, they are only imperfect proxies. On the one hand, some of these actions may reflect socially or politically motivated mob violence, only interpreted or rationalized as anti-criminal after the fact. On the other hand, even when vigilantes face incentives to engage in lethal violence (see Reference HineHine 1998), not all anti-crime organizations act violently. Thus, it is hard to know the extent to which analyzing media reports of lynchings (and other spectacular displays of collective violence) can help us understand anti-crime organization more generally.

More recently, some studies have turned to media reports of vigilante organizations (e.g., Reference Osorio, Weintraub and SchubigerOsorio, Weintraub, and Schubiger 2016; Reference PhillipsPhillips 2015). However, not all anti-crime organization attempts crystalize into formal and stable organizations. Many of these attempts find little resonance within the larger community or result only in informal or ad hoc anti-criminal groups. Of the few that succeed, not all engage in crime-control actions or become violent, and even fewer engage in an act of sufficient notoriety to be reported by the media.Footnote 10

Finally, to date, there is little consensus about the criteria for classifying an organization as “vigilante.” It is unclear whether we should look at intentions, actions, or effects as indicators of vigilantism, or how extensively or consistently these indicators should be present before a successful classification can be made. To mitigate the risks of this multilevel selection process, it is necessary to look at firsthand accounts of citizens’ behavior.

Risks and Opportunities of Anti-criminal Action

Although anti-crime organizations can vary in their structures, methods, and specific objectives, they frequently emerge from earlier (harmless and unorganized) attempts by individuals to fight crime as a collective. Thus, it is critical to understand the incentives (i.e., risks and opportunities) for citizens attempting to fight crime with their neighbors.

The first set of incentives is noncontingent, or independent of citizens’ success in fighting crime. Simply by broadcasting their intention to confront criminals, for example, citizens may raise wrongdoers’ perceived likelihood of being captured and, thus, deter some crime.Footnote 11 Further, by engaging in anti-criminal action and standing up to perceived wrongdoers, citizens may experience positive emotions (Reference De Quervain, Fischbacher, Treyer, Schellhammer, Schnyder, Buck and Fehrde Quervain et al. 2004; Reference Maitner, Mackie and SmithMaitner, Mackie, and Smith 2006). Finally, just by broadcasting their intention to fight crime directly, citizens may feel gratified because they have expressed their nonconformity with the insecurity in their communities (Reference Gollwitzer and DenzlerGollwitzer and Denzler 2009).

Conversely, citizens may experience noncontingent costs of anti-criminal action. First, citizens may have to invest valuable economic resources to mobilize their community. Second, they may need to spend time, effort, and resources that they could invest in more productive activities (Reference Bates, Greif and SinghBates, Greif, and Singh 2002). Third, although some may experience a thrill from confronting wrongdoers, others may experience a diversity of negative emotions. Just days after the start of the anti-criminal movement in Cherán, for example, one of the leaders explained, “We are experiencing ire, anger, fear, dread, and rage. But above all, we are experiencing a sentiment of humiliation for the inaction of the authorities.”Footnote 12

Although it is important to consider these consequences, it is critical to note that the biggest risks and opportunities of anti-criminal action are contingent. That is, they depend on whether citizens are successful in fighting crime with impunity. Citizens who successfully fight crime stand to benefit from their actions. Citizens who rally their community to fight crime effectively might experience a sense of satisfaction from punishing wrongdoers (Reference De Quervain, Fischbacher, Treyer, Schellhammer, Schnyder, Buck and Fehrde Quervain et al. 2004). Further, in contexts of high impunity, citizens may experience gratification from restoring what they see as justice (Reference LernerLerner 1980). Further, citizens stand to recover lost income and property and achieve an even larger deterrent effect if they can confront criminals successfully. That is, they stand to gain from a reduction in the material and immaterial costs of crime.Footnote 13

In contrast, those who unsuccessfully engage in anti-criminal actions may incur significant costs. First, citizens who do not succeed in fighting crime directly may unintentionally increase the future costs of crime. Kidnappers often kill their hostages after a failed rescue attempt, and many extortion rackets in Mexico have increased their rates after failed self-defense attempts (Reference Scandizzo and VenturaScandizzo and Ventura 2015). Second, those engaging in anti-criminal action may suffer physical, emotional, and psychological harm. The Michoacán autodefensas, for example, were not always successful, and whenever they lost territory to the drug cartels they had to endure humiliation and the loss of members and leaders (Reference Gómez, Ángel, Nácar, Reyes, Villanueva and VillalpandoGómez et al. 2014). Finally, since many forms of anti-criminal action are considered illegal, even if successful in confronting crime, citizens risk duplicating official law enforcement efforts or incurring legal sanctions. The Mexican authorities have overtly condemned vigilante justice, and many vigilante leaders have been jailed or killed by federal forces (Reference CruzCruz 2015).Footnote 14

All in all, a significant portion of the risks and opportunities associated with anti-criminal action are contingent on citizens effectively fighting crime with impunity. Since this depends on the actions of other agents, it is important to consider citizens’ perceptions of others as a potential determinant of their willingness to participate in anti-criminal action. In the following section I focus on two actors: the community and law enforcement authorities.

Trust in neighbors and anti-crime organization attempts

The first factor that may influence an individual’s expectation of benefiting from organizing with others to fight crime is her perception that her community is united and trustworthy. First, well-connected and united communities provide citizens with a social scaffolding in which resources and information can be mobilized (Reference Nahapiet and GhoshalNahapiet and Ghoshal 1998; Reference Narayan and PritchettNarayan and Pritchett 1999). Citizens who perceive their community as strong and united may expect that news of their attempts at organizing others to fight crime will spread rapidly and resonate with their neighbors. Conversely, those who perceive their community as weak and divided may have to face criminals with the help of only a handful of neighbors. Thus, there is a greater probability that they will suffer the physical, emotional, and psychological harm discussed previously.

Second, trustworthy neighbors are more likely to interact with individuals pro-socially. Therefore, when citizens perceive their neighbors as trustworthy, they may anticipate experiencing positive emotions from engaging in effective collaboration with them (Reference Jung, Choi, Lim and LeemJung et al. 2002). On the contrary, if citizens perceive their community as untrustworthy, they may anticipate frustration and other negative emotions from failing to mobilize their neighbors. Considering citizens’ perceptions of the trustworthiness of their neighbors may be important to identify the individuals who are most likely to reach out to their community to fight crime.

Many studies have considered community trust as an important determinant of collective action. Citizens who perceive others to be more trustworthy may be more likely to take a collective approach to problem solving (Reference Nahapiet and GhoshalNahapiet and Ghoshal 1998), be less fearful of free riders, be more likely to perceive that they will benefit from collective action (Reference Ostrom, Walker and GardnerOstrom, Walker, and Gardner 1992), and be more collectively efficacious (Reference Welch, Rivera, Conway, Yonkoski, Lupton and GiancolaWelch et al. 2001; Reference PutnamPutnam 1995).Footnote 15 However, most of the literature has made strong normative assumptions about the nature of social trust. I join a new group of scholars challenging this assumption by considering social trust as a motor that propels collective action but that, depending on the context, can have mixed implications for the state and society.Footnote 16 In what contexts are citizens more likely to invest their social capital outside the established institutions of the state?

The moderating effect of the state: An interactive trust hypothesis

Since the first works in modern political thought, the state has been seen as more than a repository of symbolic representation. For a long time, authors from very different backgrounds have conceded that, beyond its role as a representative, the state plays an important role as a social moderator (e.g., Reference HobbesHobbes 1651; Reference Locke and MacphersonLocke 1689), that is, as a force that structures the contexts in which citizens can exercise their liberty to pursue their individual interests at the expense of the common good. Building on this notion of the state, a number of scholars have proposed (and identified empirically) citizens’ distrust in state law enforcement to be an important predictor of state reliance (or a lack thereof).Footnote 17

Undoubtedly, there are reasons to expect citizens to delegate to the authorities when they see them as trustworthy. When the likelihood of state authorities intervening effectively is high, citizens can expect to obtain a positive outcome from reporting crime and to incur legal costs if they take the law into their own hands. Since appealing to law enforcement authorities is less costly and risky than confronting criminals directly, ceteris paribus, as the probability of effective police intervention increases, the relative utility of citizens taking the law into their own hands decreases.

Trust in state authorities has been found to be a significant determinant of citizens’ willingness to support harsh anti-criminal punishment (Reference Soss, Langbein and MetelkoSoss, Langbein, and Metelko 2003), report crime (Reference Messing, Becerra, Ward-Lasher and AndroffMessing et al. 2015; Reference MaloneMalone 2012), and uphold and collaborate with law enforcement authorities to fight and prevent crime (Reference Hough, Jackson, Bradford, Myhill and QuintonHough et al. 2010; Reference Tyler and FaganTyler and Fagan 2008).Footnote 18 In the midst of police reform in Latin America, citizens who trust the police have also been observed to be more likely to participate in programs in which the state authorities invite local citizens to help them prevent, monitor, denounce, or persecute crime (Reference Arias and UngarArias and Ungar 2009; Reference SabetSabet 2014).

Distrust in law enforcement seems to set the conditions in which citizens are more likely to seek alternative sources of criminal justice. As Diamond (Reference Diamond1999, 91) famously noted, “In the context of weak states and inefficient, poorly disciplined police, crime may inspire drastic, illegal, unconstitutional, and grotesquely sadistic responses to try to control it.” Thus, I propose that trust informs citizens’ willingness to engage in an anti-crime organization attempt on two levels. First, distrust in law enforcement sets the stage for citizens to consider alternative sources of criminal justice.Footnote 19 Second, a citizen’s perception of the trustworthiness of her community informs her likelihood of turning to her neighbors to confront criminals directly.

Even though this interactive hypothesis has not been explicitly tested, previous scholarship has hinted at its general validity. Gamson (Reference Gamson1968) and then Seligson (Reference Seligson1980) proposed that trust in the state influences the degree to which collective efficacy translates into alienated or democratic activism. Similarly, in his in-depth study of lynchings in Guatemala, Mendoza (Reference Mendoza2006) suggests that solidarity links among co-ethnics can trump barriers to collective action, especially in areas in which the state has traditionally failed to provide citizens with basic security services.

Along the same lines, in her work in Central America, Malone (Reference Malone2012, 117) notes, “in order for the perceived failure of the justice system to translate into collective action, citizens would need to have some sense of solidarity with other members of their community and view citizen action as a viable means for achieving their goals.” In his in-depth investigation of the Mano Amiga program in Honduras, Ungar (Reference Ungar, Bergman and Whitehead2009) found that, faced with untrustworthy law enforcement authorities, a number of citizens invested their newly acquired social resources into the constitution of vigilante organizations. This led to an unintended increase in vigilantism which, in turn, prevented the program from resulting in a marked reduction in violence.Footnote 20

In the following section, I test the moderating effect of distrust in law enforcement over the effect of social trust. I do so using a rarely utilized data source that has collected information about citizens’ anti-crime organization attempts over the last ten years: ENVIPE.

Methods

Since 2006, Mexico has experienced one of its most serious security crises in modern history. In December of that year, the then newly elected president Felipe Calderón sent some 6,500 Mexican soldiers to the state of Michoacán to start the so-called war on drugs. Since then, Mexicans have faced an increase in the militarization of security (Reference AnayaAnaya 2014) and the aggressiveness of drug cartels (Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and MagaloniCalderón et al. 2015; Reference PhillipsPhillips 2015). Consequently, there has been a rapid rise in homicides, kidnappings, and other acts of violence (Reference Atuesta, Siordia and LajousAtuesta, Siordia, and Madrazo Lajous 2016; Reference SchedlerSchedler 2015; Reference Shirk and WallmanShirk and Wallman 2015).

Kidnappings increased from 2,687 (2001–2006) to more than 6,500 (2006–2012), and summary executions climbed from fewer than 1,000 per year prior to 2006 to nearly 13,000 in 2011 (Reference AtuestaAtuesta 2016). In total, drug-related homicides jumped from fewer than ten thousand between 2000 and 2006 to more than fifty thousand during the first phase of the war on drugs (2006–2012)—more than a fivefold increase (Reference Atuesta, Siordia and LajousAtuesta, Siordia, and Madrazo Lajous 2016; Reference RiosRios 2013). As a consequence of this increase in violence, since 2010 Mexico’s National Institute of Geography and Statistics (INEGI) has conducted annual nationally representative surveys (n ≈ 65,000 each) that recover information about citizens’ perceptions of insecurity and crime victimization histories.Footnote 21

Crucially, in addition to questions on these topics, the 460,329 respondents that participated in the six waves of ENVIPE were asked about their trust in neighbors, trust in the police, and their participation in anti-crime organization attempts.Footnote 22 On this topic, INEGI asked respondents: “In the previous year, did this household take joint action with its neighbors to defend itself from crime [Yes or No]?”Although this question does not allow us to identify actions involving extralegal violence, it gives us a unique opportunity to study Mexicans’ willingness to turn to their community to attempt to prevent or control crime at the individual level. Importantly, it is possible to use this information to compare how frequently individuals with different characteristics (including trust in neighbors and the government) attempt anti-crime organization, while holding other factors constant.

Overall, amid the context of the ongoing war on drugs, 42.10 percent of Mexicans perceive the neighborhood in which they live as unsafe, and 32.9 percent of Mexican households report being victims of crime in an average year. This is particularly concerning if one considers that this number is double the average for the Latin American and Caribbean region (between 17 percent and 19.2 percent, according to Reference Hinton, Montalvo, Maldonado, Moseley, Zizumbo-Colunga and ZechmeisterHinton et al. 2014). In this context, Mexicans tend to be much more trusting of their neighbors than of the police. On a scale of 0 to 100, Mexicans’ trust in their neighbors is about 64.21. In contrast, on this same scale, citizens’ trust in the police is only about 40.5. Not surprisingly, about 10.49 percent of citizens take joint action with their neighbors to defend themselves from crime every year, and this number increased from about 7.9 percent in 2011 to about 14.4 percent in 2015. This represents an 80 percent increase.Footnote 23

As suggestive as these statistics may be, to evaluate whether citizens’ trust in their neighbors influences their participation in anti-crime organization attempts and whether this link is moderated by their distrust in the police, it is necessary to take a closer look at individual-level data. To do so, I specify a logistic regression model in which the probability of a citizen engaging in anti-crime organization is a function of the following equation:

In this equation, the term Trust N represents a variable that captures citizens’ trust in their community, Distrust P represents a variable that captures citizens’ distrust in the police, and Trust N × Distrust P represents the product of these two variables. This last term is included to estimate the degree to which distrust in the police modifies the effect of trust in neighbors. If the interactive trust hypothesis is consistent with this data, we should expect a positive and significant coefficient associated with this term.

The term φ′ CONTROLS′ represents a vector of control variables. This vector is composed of demographics (sex, education, age, size of the locality, and occupation) and other variables the literature highlights as important determinants of anti-crime organization.Footnote 24

First, I control for citizens’ perceived and actual exposure to crime and insecurity. Both variables have been shown to be negatively associated with social trust (Reference BatesonBateson 2012; Reference Corbacho, Philipp and Ruiz-VegaCorbacho, Philipp, and Ruiz-Vega 2015) and trust in law enforcement authorities (Reference BlancoBlanco 2013; Reference Blanco and RuizBlanco and Ruiz 2013; Reference Corbacho, Philipp and Ruiz-VegaCorbacho Philipp, and Ruiz-Vega 2015; Reference MaloneMalone 2010), but positively associated with citizens’ attitudes toward vigilantism (Reference BatesonBateson 2012; Reference MaloneMalone 2012; Reference SeligsonSeligson 2003). Thus, these variables could negatively bias our results. To be precise, if those who trust their neighbors are less likely to be exposed to crime and more likely to support vigilantism, our regression coefficient could fail to find a relation when one exists. To account for this potential source of bias, I control for crime victimization, for an index of perceived insecurity, and for an index of exposure to crime in the neighborhood.Footnote 25

Second, I consider whether respondents are embedded in communities with a strong indigenous presence. Previous studies have hypothesized a link between these contexts and citizens’ willingness to participate in anti-crime organization. In areas where strong traditional justice systems exist, the argument goes, citizens may be more inclined to turn to their community to apply what they consider fairer and more legitimate criminal sanctions (Reference Clunan and TrinkunasClunan and Trinkunas 2010; Reference VilasVilas 2001).Footnote 26 Given this argument and the stylized observation that violent anti-criminal events have been most frequently reported in traditionally indigenous regions (Reference Hawkins, McDonald and RandolphHawkins, McDonald, and Adams 2013; Reference VilasVilas 2009; Reference MendozaMendoza 2006), I control for the proportion of citizens self-identifying as indigenous in the interviewee’s municipality (from the 2015 inter-census survey). Although imperfect, this variable (municipal % indigenous) allows us to account for some of the variation associated with the diversity of indigenous cultural systems in Mexico.Footnote 27

Finally, I control for the subnational context in which the respondents are embedded. This is important, since different states have experienced different levels of violence. While some states, such as Guerrero and Michoacán, are very conflictive, states such as Yucatán, Campeche, and Aguascalientes tend to be more peaceful. Further, while some years have been particularly bloody, others have gone by with relatively less violence. To achieve this level of control, I include a vector of 192 dummy variables (θ′ STATEYEAR′) that identify each state-year in which the study was conducted.Footnote 28

Results

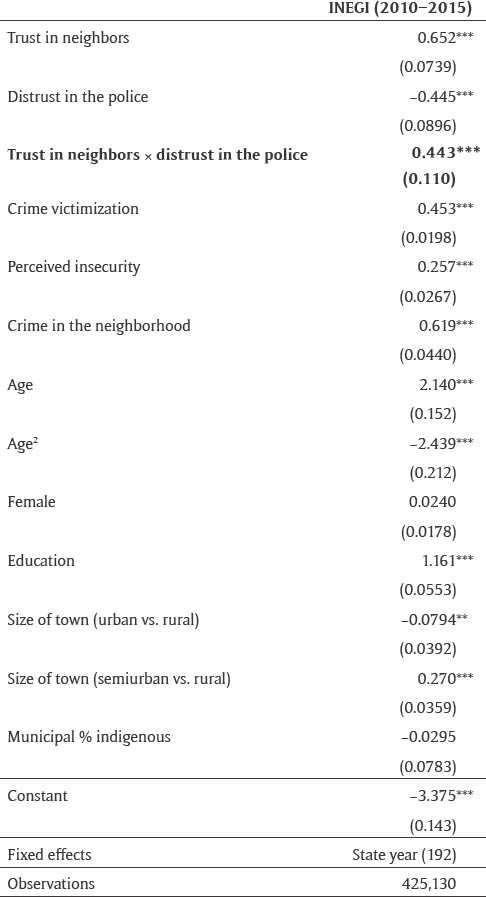

Table 1 shows the results of estimating the model described earlier. First, I find that middle-aged and educated individuals are more likely to seek out their neighbors to fight crime, holding other variables relating to insecurity, violence, and trust in the authorities constant. Second, in line with the previous literature, I find that individuals who have been personally victimized by crime, who perceive a high level of insecurity, and who live in crime-ridden neighborhoods are more likely to engage in anti-crime organization attempts, holding other variables constant.Footnote 29

Table 1: Determinants of anti-crime organization attempts in Mexico.

Design-based standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

In substantive terms, increasing an average citizen’s perception of insecurity from the minimum to the maximum is associated with a 2.5 percent increase in her probability of engaging in an anti-crime organization attempt. Moving this citizen from a household that has been victimized by crime to one that has not is associated with a 4.7 percent increase in the probability of her engaging in this type of behavior. And moving an average citizen from a household victimized by crime from an extremely safe to an extremely dangerous neighborhood is associated with a 6.78 percent increase in her probability of reaching out to her neighbors to fight crime. However, I do not find support for the sociocultural hypothesis. That is, I find that an average citizen living in a majority-indigenous municipality is not significantly more likely to engage in an anti-crime organization attempt than one living in a minority-indigenous municipality.

Although Table 1 shows significant coefficients associated with trust in neighbors and distrust in the police, these effects are not directly interpretable. Because of the inclusion of the interaction between both variables in the model, it is necessary to fix one variable to its mean before estimating the effect of the other. When doing this, I do not find the effect of citizens’ distrust in the police to be statistically distinguishable from zero. However, I find citizens’ trust in their neighbors to have a significant and strong effect on their likelihood to engage in an anti-crime organization attempt.

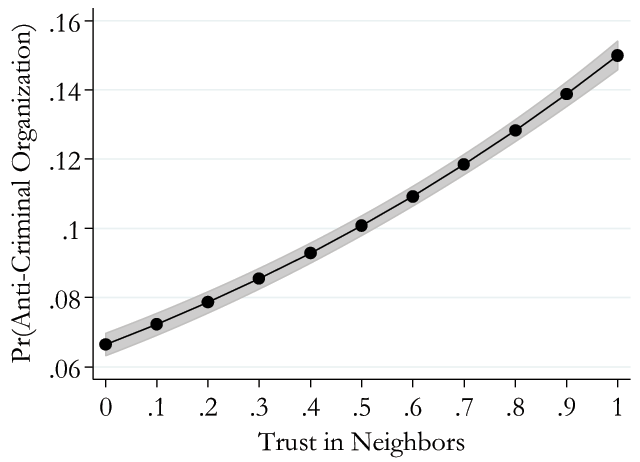

As Figure 1 shows, when distrust in the police is set to its mean, a minimum to maximum change in an average citizen’s trust in her neighbors is associated with an 8.3 percent change in her probability of engaging in an anti-crime organization attempt. Moreover, consistent with the idea that citizens’ distrust in the authorities activates the link between these two variables, I find a positive and significant interaction between police distrust and citizens’ trust in neighbors (in bold in Table 1). In other words, I find that as respondents’ distrust in the police increases, so does the effect of trust in neighbors. Figure 2 illustrates this moderating effect more closely. The vertical axis in the figure displays the estimated min-max effect of trust in neighbors, and the horizontal axis displays an average citizen’s distrust in the police. The confidence intervals in the figures (the shaded area) account for the complexity of the ENVIPE samples.

Figure 1: Trust in neighbors and anti-crime organization.

As Figure 2 shows, among citizens with a low level of distrust in the police, a min-max change in an average individual’s trust in neighbors is associated with a 6.5 percent change in her probability of engaging in an anti-crime organization attempt. Figure 2 shows that among those with a high level of distrust in the police, a maximum change in an average individual’s trust in neighbors is associated with a 9.3 percent change in her probability of engaging in an anti-crime organization attempt. This represents an increase of 43.4 percent in the effect of trust in neighbors.Footnote 30

Figure 2: Moderating effect of police distrust on the effect of trust in neighbors.

Taken together, these results are consistent with the common observation that anti-crime organization tends to emerge in crime-ridden and insecure neighborhoods. They show that individuals are more likely to engage in anti-crime organization attempts when they perceive more insecurity and live in a neighborhood where crime occurs more frequently. The latter factor carries the strongest effect. This is perhaps due to citizens considering it more likely that others will join in with their anti-crime organization attempts when they share the costs of crime.

Further, they show that, when these contextual variables are held constant, individuals who possess the most educational, physical, and social resources are most likely to turn to their neighbors to confront crime. Indeed, middle-aged individuals with high levels of education and trust in neighbors, in semirural contexts with high insecurity, seem to be the most likely to engage in an anti-crime organization attempt. The effect of increasing an average citizen’s trust in neighbors from the minimum to the maximum equates to moving her from a neighborhood in which gunshots, extortions, assaults, or kidnappings do not occur to one in which they do.Footnote 31

Finally, although I do not find distrust in the police to have a significant effect for the average citizen, in line with the interactive hypothesis, I find this variable to have a significant moderating role. That is, I find distrust in the police to increase the positive effect of citizens’ trust in neighbors.Footnote 32 While trust in neighbors has a positive effect among both sectors, it translates most strongly into an increased likelihood to engage in an anti-crime organization attempt among Mexicans who distrust the police.Footnote 33

Conclusion

This article has sought to contribute to our understanding of anti-crime organization by empirically investigating the factors that influence individuals’ likelihood to reach out to their neighbors to defend themselves from crime. I have argued that, all other things being constant, citizens’ likelihood to engage in an anti-crime organization attempt is influenced by their evaluation of their neighbors. Further, I have argued that the effect of this variable is exacerbated in contexts in which citizens distrust law enforcement bodies. To test these ideas, I analyzed individual-level data that INEGI has collected over the last ten years.

Consistent with the framework presented earlier, I find evidence that citizens who trust their neighbors more are more likely to join them in an attempt to defend themselves from crime. Further, I find this effect to be stronger among citizens who distrust the police. More broadly, the theoretical approach presented in this article is supportive of Gamson’s (Reference Gamson1968) view that trust in the government moderates the effect of citizens’ collective efficacy. However, it also pushes this framework forward by theorizing about the way citizens’ distrust in state authorities moderates their intra- and extra-state investments. All in all, the evidence presented here suggests that when citizens lose their confidence in law enforcement authorities, they are more likely to engage in what Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1978) once described as an “exit strategy” and invest their social resources in an attempt to resolve their most urgent problems by themselves.

It is true that many community efforts to replace the state can be preventive, innocuous, or go completely unnoticed. However, citizens’ attempts to defend themselves from crime can sometimes become active and violent. They can infringe on the alleged criminal’s individual rights, carry with them important opportunity costs, and in extreme cases shake the very foundations of the state. Even if this article is not directly connected to these outcomes, it tries to contribute to an empirical platform through which the emergence of established, violent crime-control organizations can eventually be understood by shedding light on the determinants of early individual manifestations of this phenomenon.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

† Additional file Online appendix. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.324.s1