No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

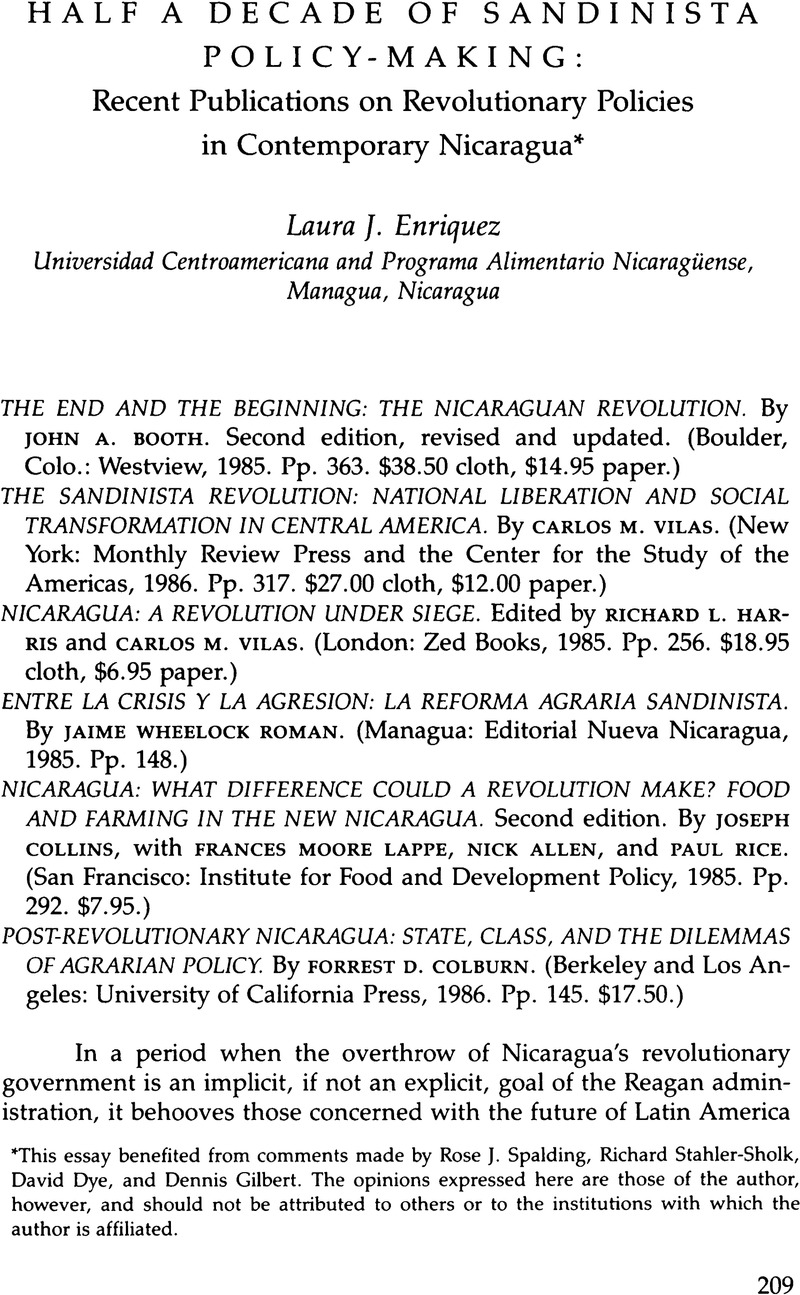

This essay benefited from comments made by Rose J. Spalding, Richard Stahler-Sholk, David Dye, and Dennis Gilbert. The opinions expressed here are those of the author, however, and should not be attributed to others or to the institutions with which the author is affiliated.

1. Nicaragua: The First Five Years, edited by Thomas Walker (New York: Praeger Books, 1985), has been left out of this review because I contributed one of its chapters. The notes below refer to a number of additional recent publications that address some aspect of Sandinista policy-making.

2. In Comisión Económica para América Latina (CEPAL), Nicaragua: el impacto de la mutación política (Santiago, Chile: CEPAL, 1981). The assumptions underlying this program accorded with the critiques of prerevolutionary Nicaragua developed over many years by the FSLN. See Jaime Wheelock Román, Nicaragua: imperialismo y dictadura (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1980); and Orlando Núñez Soto, El somocismo y el modelo capitalista agro-exportador (n.p.: Departamento de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Autónoma de Nicaragua, n.d.).

3. The Spanish edition of this volume was published by Ediciones Era (Mexico City, 1985). It contains four additional chapters on the contradictions of the mixed economy, the transformation of the state, worker participation in state enterprises, and women in Nicaragua. The first of these additional chapters in particular makes reading the Spanish edition worthwhile.

4. See Nicaragua in Revolution, edited by Thomas Walker (New York: Praeger, 1982), and his Nicaragua: The First Five Years.

5. Agriculture generates 70.6 percent of Nicaragua's foreign exchange earnings and employs 47.2 percent of the total economically active population (EAP). See Fondo Internacional de Desarrollo Agrícola (FIDA), Informe de la misión especial de programación a Nicaragua (n.p.: FIDA, 1980).

6. See Wheelock Román, Nicaragua: imperialismo y dictadura.

7. See further, MIDINRA, “Transformación de la tenencia de la tierra para 1986,” Informaciones Agropecuarias 2, no. 17 (June–July 1986):4.

8. Colburn divides cotton growers into those with more or less than 50 manzanas, and coffee growers into those with more or less than 10 manzanas. The Nicaraguan banks (which provide credit to farmers) and MIDINRA (which makes agrarian policies) recognize a third important category of production—that of medium-sized producers. My analysis will rely on the following definition employed by MIDINRA: “Small Producers are those who possess up to 15 manzanas in basic grains, 10 in coffee or cacao, 3 in vegetables, 20 in cotton, or 10 in other perennial crops. Medium producers are those with 15–75 manzanas in basic grains, 10–30 in coffee or cacao, 20–100 in cotton, or 10–20 in other perennial crops. Large producers are those with more land in any of these categories.” See MIDINRA, Plan operativo de granos básicos: ciclo agrícola, 1982–83 (Managua: MIDINRA, 1982), 172.

9. A review of the various studies that stratify coffee producers can be found in Alicia Gariazzo, “El café en Nicaragua: los pequeños productores de Matagalpa y Carazo,” Cuadernos de Pensamiento Propio, Serie Avances no. 2 (Dec. 1984):21–29.

10. See “U.S. Role in Nicaraguan Vote Disputed,” New York Times, 21 Oct. 1984, p. 12; and La Nación, 25 Aug. 1985.

11. FIDA, Informe; and Banco Central de Nicaragua, Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Comercio, Censos Nacionales, 1971: Población, 1 (Oct. 1974):v.

12. Baumeister defines medium-sized multifamily farms as having between 50 and 500 manzanas. Small producers (which cover several categories from micro-finca to family fincas) have less than 50 manzanas, and large producers have more than 500. Note the difference between Baumeister's and Colburn's definitions.

13. Baumeister, “Structure of Nicaraguan Agriculture,” 24.

14. In a more recent article, Baumeister explains the significance of amendments to the agrarian reform law approved in early 1986. See Baumeister, “Estado-mundo agrícola: una relación cambíente,” Pensamiento Propio 4, no. 34 (July 1986).

15. See Rosa María Torres, Nicaragua: revolución popular, educación popular (Mexico City: Editorial Línea, 1985); Valerie Miller, Between Struggle and Hope: The Nicaraguan Literacy Crusade (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1985); Martin Diskin, Thomas Bossert, Salomon Nahmad S., and Stefano Varese, “Peace and Autonomy on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua: A Report of the Latin American Studies Association Task Force on Human Rights and Academic Freedom,” LASA Forum 16, no. 4 (Spring 1986) and 17, no. 2 (Summer 1986); and Rose Spalding, The Political Economy of Revolutionary Nicaragua (Winchester, Mass.: Allen and Unwin, 1986).

16. See Reid Brody, Contra Terror in Nicaragua: Report of a Fact-Finding Mission, September 1984–January 1985 (Boston: South End Press, 1985); E. V. K. FitzGerald, “An Evaluation of the Economic Costs of U.S. Aggression against Nicaragua,” in Spalding, Political Economy of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 195–213; and Raúl Vergara Meneses, José R. Castro, and Deborah Barry, “Nicaragua: país sitiado (guerra de baja intensidad: agresión y sobrevivencia),” in Cuadernos de Pensamiento Propio, Serie Avances no. 4 (June 1986).