No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

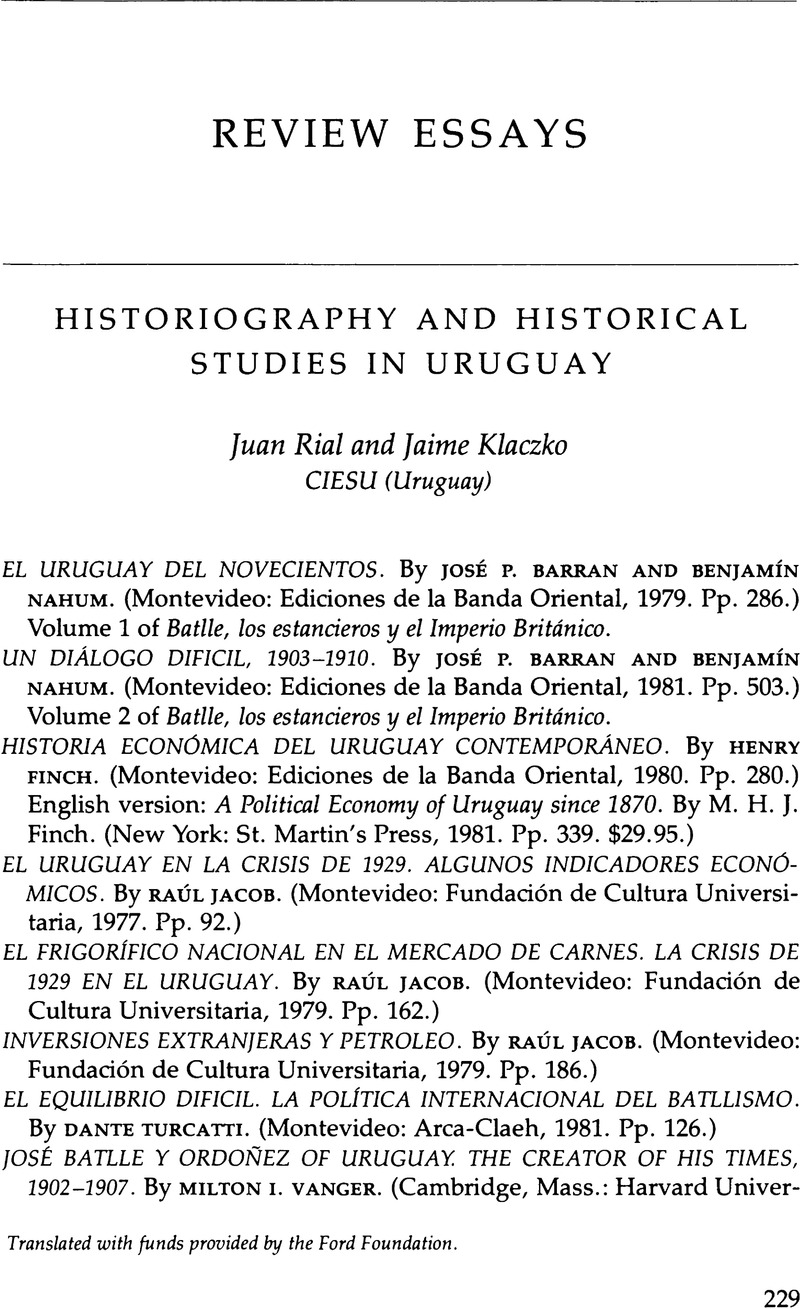

Historiography and Historical Studies in Uruguay

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1982 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Refers to the activity of commercial intermediaries in importation (and, to a lesser degree, in exportation) carried out in the port of Montevideo, serving the riparian regions of the rivers above the basin of the Plata and the southern part of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul.

2. In the area of history, only one meeting was organized during the period, in 1970, in CIESU. It was organized in conjunction with the Commission of Regional and Urban Development of CLACSO, and brought together various researchers from the Southern Cone. This is also true at a national level, so that at the initiative of various centers, meetings of historians have been taking place since 1980 to discuss problems that affect the limited academic community and the fruits of its research.

3. Different meanings are attributed to the term batllismo. In one sense, it can refer to a period of study. Thus, for some, batllismo would be defined as a phase of national life that extended from the first (or second) presidency of José Batlle y Ordoñez—1903 or 1911—to the coup d'état of 1933. This was the period of the greatest activity of the movement's leader, who died in 1929. For others, the phenomenon is characterized as the politico-economic and social regime dominant in Uruguay during the greater part of the twentieth century, at least until the beginning of the 1970s. From another position, use of the term would be limited to the ection of the political movement initiated by Batlle y Ordoñez and others, concentrating exclusively on the personal action of this politician.

4. For example, among foreigners: Simon G. Hanson, Utopia in Uruguay: Chapter in the Economic History of Uruguay (New York: Oxford University Press, 1938); George Pendle, Uruguay. South America's First Welfare State (London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1952); Russell H. Fitzgibbon, Uruguay, Portrait of a Democracy (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1954); Philip B. Taylor, “The Uruguayan Coup d'État of 1933,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 22, no. 3 (Aug. 1952); Goran Lindahl, Uruguay's New Path (Stockholm: 1960. The version in Spanish is entitled Batlle, fundador de la democracia [Montevideo; Arca, 1971]). Among the most noted Uruguayans we cite the works of Carlos Real de Azüa, El impulso y su freno (Montevideo: EBO, 1964); Ricardo Martínez Ces, El Uruguay batllista (Montevideo: EBO, 1962); Carlos M. Rama, “Batlle: la conciencia social,” Enciclopedia Uruguaya No. 34 (Montevideo, 1969); Juan A. Oddone, “Batlle. La democracia uruguaya,” Historia de América en el siglo XX (Buenos Aires, 1972); Guillermo Vásquez Franco, El país que Batlle heredó (Montevideo: FCU, 1971); Julio A. Louis, Batlle y Ordoñez. Apogeo y muerte de la democracia burguesa (Montevideo: Nativa, 1969); Gerónimo de Sierra et al., series of five articles published by the Instituto de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad, Cuaderno No. 2 (Montevideo, 1972). Previously, from a critical position, the following had been written: Francisco R. Pintos, Batlle y el proceso histórico del Uruguay (Montevideo: Claudio Garcia, 1938); Vivian Trías, “Raíces, apogeo y frustración de la burguesía nacional,” Nuestro Tiempo, no. 3 (Montevideo: 1955). From an apologist position, among others, Roberto B. Giudice and Efrain Gonzales Conzi, Batlle y el Batllismo (Montevideo, 1928); José Buzzetti, La magnifica gestión de Batlle en Obras Públicas (Montevideo, 1946); Antonio M. Grompone, Batlle. Sus artículos. El concepto democrático (Montevideo, 1943); Justino Zavala Muníz, Batlle. Heroe Civil (México: FCE, 1945); Enrique Rodríguez Fabregat, Batlle. El Reformador (Buenos Aires: Claridad, 1942); Editorial Acción (various authors), Batlle. Su Vida. Su Obra (Montevideo, 1956).

5. Vanger notes the bias of “presentism,” which characterizes many of the historical interpretations of the Uruguayan process at the beginning of the century (1980, p. vii) but he, probably more than others, falls into this same “sin” (see pages 354 and, especially, 359 of Model Country, where he asks, “What would Don Pepe [Batlle] do if he were alive today?”)

6. Exception should be made of Barran and Nahum, El Uruguay, where they compare the different modes of access to power used by Batlle y Ordoñez and Yrigoyen of Argentina (one through access to government through manipulation of the state apparatus, and the other through the support of a party from the plains). Also Finch, based primarily upon the use of British sources, tends toward a global vision of the insertion of the Uruguayan economy into the capitalist market. Vanger in the introduction to Model Country, points out that his book could be a contribution to understanding, in a comparative manner, the rise of populism in the Southern Cone during the first three decades (p. viii) but this is his only reference to the topic.

7. This notion seems to have been taken from an earlier idea of Barran, in which he describes the “expulsion of young Montevidean intellectuals” in 1872; “uncontaminated … they felt like politicians and nothing more than that. This was also why they fell. They did not represent anyone but themselves” (in Marcha, 13/8/1965).

8. On the other hand, to carry forward a “political career,” which Tomas de Iriarte called a “revolutionary career” in the atmosphere of the “years of turmoil” of the nineteenth century, was, and is, an ambition common to all those who embark upon that path. It also supposes acceptance of both triumph and failure. The difficulties involved in the construction of the state in Uruguay—similar to those which occurred in the rest of Latin America—plagued with conflicts and violence, with winners and losers, allowed some to reach their goal while others did not. Thus, the members of the Colorado party, having power and, as a result, control of the incipient state apparatus, found themselves better off, having embarked upon this “career,” than their colleagues of the opposition party. Curiously, it was precisely the historical vicissitudes that derived from the predominance of batllismo and from defeat of their attempt to legalize constitutionally this arbitrary behavior that constituted a system of political coparticipation—pacific in tone—which permitted the “political career” at the national level to include members of the Blanco party.

9. Vanger indicated that if Batlle's base of support was the political elite, the defeat of the Colegiado in 1916—a formulation which was proposed constitutionally—and the later deterioration of batllismo would be inexplicable.

10. Carlos Zubillaga notes, among other examples relating to the behavior of political personnel, the relationship of this to economic interests. He cites, in this case, the activity of the legislator Antonio María Rodríguez, one of the principal professional politicians noted by Barran and Nahum, who in his role as representative of some of the creditors of the Ferrocarril Pan-Americano, exercised various pressures in favor of those he represented. This was done within the legislative branch itself and was the object of a denunciation in the Senate.

11. He analyzes the period by examining how the various protagonists identified one another, particularly in the press, or in the diplomatic dispatches of the Foreign Office. His study offers a view of the everyday expressions and polemics by which the actors recognized one another. Since these were characteristic of a combative, opinionated press or of the threatened British interests, this diminishes any attempt at objectivity.

12. Although the use of the private archives of the principal actors is infrequent in our own historiography, their use here by Vanger lends the text a human dimension, characterized by Batlle's attitudes toward specific events. It is, however, necessarily partial, since it offers only his perspective and not that of his antagonists.

13. Vanger's tone is polemical, more energetic in the second volume than in the first, dealing very specifically with events and people. The author directly states that a book that studies the political activity of an individual should include sufficient politics (Model Country, p. viii) since its principal documentary source, Batlle's private archive, pursues a political end (p. 361, note 1). Another difference is due to developments in the author's own viewpoint. In the first volume, the description of the political process makes Batlle “the creator of his times”; in the second volume, he is the man determined to construct and direct the “model country,” within a specific political setting. This had also been alluded to in 1963, when Vanger indicated that his study examined “the way in which a great Latin American reformist leader obtained and consolidated his power, of his transformation from Batlle into BATLLE.”

14. Thus, Vanger refers to how the partisan electoral committee was dissolved after the election (p. 117), noting the absence of any permanent organization. Further on, he underscores that Batlle preferred the position of party chief to any other role in the state apparatus and that he wanted to reserve it for himself exclusively (p. 227). See Aldo Solari in Estudio sobre la sociedad Uruguaya (Montevideo: Arca, 1964).

15. The author compiles, in tables 1 and 3 (p. 159), the electoral history of Radicalismo Blanco. It is evident there that, even in 1922, the Nacional party sustained the lowest electoral percentage in the lema of Montevideo than in any other section in which it had candidates. Carnelli, identified by his program as a representative of the urban population, lost votes in successive elections while the radical bastions, Soriano and Tacauarembo, held strong. In the 1931 election, they achieved a vote that was, in absolute terms, higher than that in the capital. The action of local leaders, like Ricardo Paseyro in Soriano and even the activity of Carnelli in his role as a lawyer in Tacuarembo, seem to explain the behavior of radical dissidence better than any doctrinaire statements.

16. The originality of this initiative, attributed to Batlle in our country, has been recently questioned. In the archives of the Ecclesiastical Tribunal of Montevideo, there is a personal letter from Monseñor Mariano Soler, Bishop of Montevideo, to Dr. Juan Zorrilla of San Martín, Uruguayan delegate to the Ibero-American Judicial Conference in Madrid in 1892. In the letter, he proposed the arbitration of international conflicts by the Pope, in light of his having political authority without temporal interests. Zorilla made the proposal in Congress (25/10/1892), but without mentioning the participation of the Papacy (radio interview with Carlos Zubillaga, 22/3/1981).

17. Vanger indicates that Batlle himself stated in his private correspondence that the role of Uruguay in the conference was “insignificant;” during the four-month period the Uruguayan delegate only spoke twice. The proposal was sent to a commission, treated as the last item of the final agenda and, finally, removed from the agenda.

18. The authors cite the works of P. Guillaume and J. P. Poussou, Demographie historique (Paris, 1979), and Louis Henry, Manuel de demographie historique (1970); they do not mention the studies of Lattes and Recchini de Lattes on Argentina, a setting fairly similar to that of Uruguay (at least with regard to the region of the Pampa), nor that of Ana M. Rothman, Evolución de la fecundidad en Argentina y Uruguay (Buenos Aires, Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, 1979).

19. The authors use gross rates of birth and mortality in an open population, which includes a heavy influx of foreign immigrants that raised considerably the ratios' denominators; they should have used life expectancy at birth. The results reached through the use of these data on fecundity are not convincing since the 1908 census did not cross the variable of the number of children with that of the age of the mothers. Although it might be said that foreign women had a lower fecundity, this is not easily proven; moreover, it is probable that if this were the case, it would not be so much a result of their being immigrants, as it was of the economic conditions to which they were subjected. But, the most important thing to bear in mind is that while there were many immigrant marriages, many others took place between immigrant males and native females. The importance attributed by Barran and Nahum to the decrease in the marriage rate should be balanced against the high number of nonlegal unions, of more uxorio marriages. These were prevalent in the rural areas and resulted in a high rate of illegitimate births.

20. Nahum—in a work made available in 1975, La época batllista (Montevideo: EBO)—has maintained that Batlle attempted to create a country composed of middle classes. Vanger, in Model Country, completely denies this possibility, believing that any characterization of Uruguay as a country of middle classes must be postponed until after the Second World War. On this topic, one can turn to the work of Germán Rama, El ascenso de las clases medias (Montevideo: Arca, 1969); Solari, Estudios sobre la sociedad Uruguaya (Montevideo, 1964), p. 113 and ss; and G. de Sierra, “Estructura económica y estructura de clases en el Uruguay,” Cuadernos de Ciencias Sociales (Montevideo, 1970).

21. See H. Finch: “Three Perspectives on the Crisis in Uruguay,” Journal of Latin American Studies 3 no. 2 (Nov. 1971): 173–90.

22. This is the result of a program which was adequate for times of prosperity. (Similar expressions have been used by Tulio Halperin Donghi and Guillermo Vázquez Franco.) This has been noted not only during the first period of batllismo, but also after the Second World War, a period in which there was also important economic growth, especially in industry and agriculture, backed by an international climate which permitted a favorable placement of our primary export product.

23. The ordering of the chapters is noticeably improved in Finch's English edition. Page references, except for the final chapter—which does not appear in Spanish—are from the Montevidean edition.

24. Finch emphasizes that salary adjustment is the product of a theory that exalts the role of private entrepreneur, and its implementation leads to a decline in real wages. This should not be seen as a deliberate attack upon the working class, even though this is what it is. The government did not wish to punish the members of the working class since they did not support the subversive movement, and Finch feels they should not be considered a principal component of the leftist coalition of 1971, the Frente Amplio.

25. More recent analyses examine the role of the financial sector and of the possible problems that maintenance of the interrelationship between the present neoliberal economic model and the possible processes of redemocratization would generate. (See J. Notaro, Estado y Economía en el Uruguay: Hipotesis sobre sus interrelaciones actuales [Montevideo: Ciedur, 1980], mimeo.)

26. On this topic, Luis E. Gonzalez and Jorge Notaro recently wrote an interesting article, “Alcances de una política estabilizadora heterodoxa, Uruguay, 1974–1978,” Latin American Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C., 1979.

27. See Barran and Nahum, Historia rural del Uruguay moderno, volume 6, La civilización ganadera bajo Batlle (Montevideo, 1977), pp. 386ff, and volume 7, Agricultura, crédito y transporte bajo Batlle (1978), pp. 187ff. The hypotheses of Luis E. Gonzales and D. Pineiro, in accordance with Finch, can be examined in Racionalidad empresaria y tecnología en el Río de la Plata hacia 1900 (Montevideo: Ciesu, 1980) and José M. Alonso and C. Perez Arrarte, Adopción de tecnología en la ganadería vacuna uruguaya (Montevideo: Cive, 1980).

28. “The State must initiate a public works plan capable of dispelling the present atmosphere of laziness and of breathing life into all the producers in the entire country,” said Eduardo Acevedo, one of Batlle's ministers. This was an attitude that he would repeat on various occasions, especially in light of the crisis of 1929.

29. More precisely it would be necessary to distinguish between capital applied directly to production (there was no such case) and capital applied to infrastructure (ports, roadways), research, and technology, from that which pursued social ends (promotion and welfare, urban infrastructure, drainage, education, etc.). Zubillaga grouped all of these together as productive capital, as well as the loans destined to financial entities (state banks). He considers nonproductive capital that which is destined to handle treasury budget deficits, to refinance earlier debts, and that applied to the construction of public buildings, parks, etc.—which he considers sumptuary.