Article contents

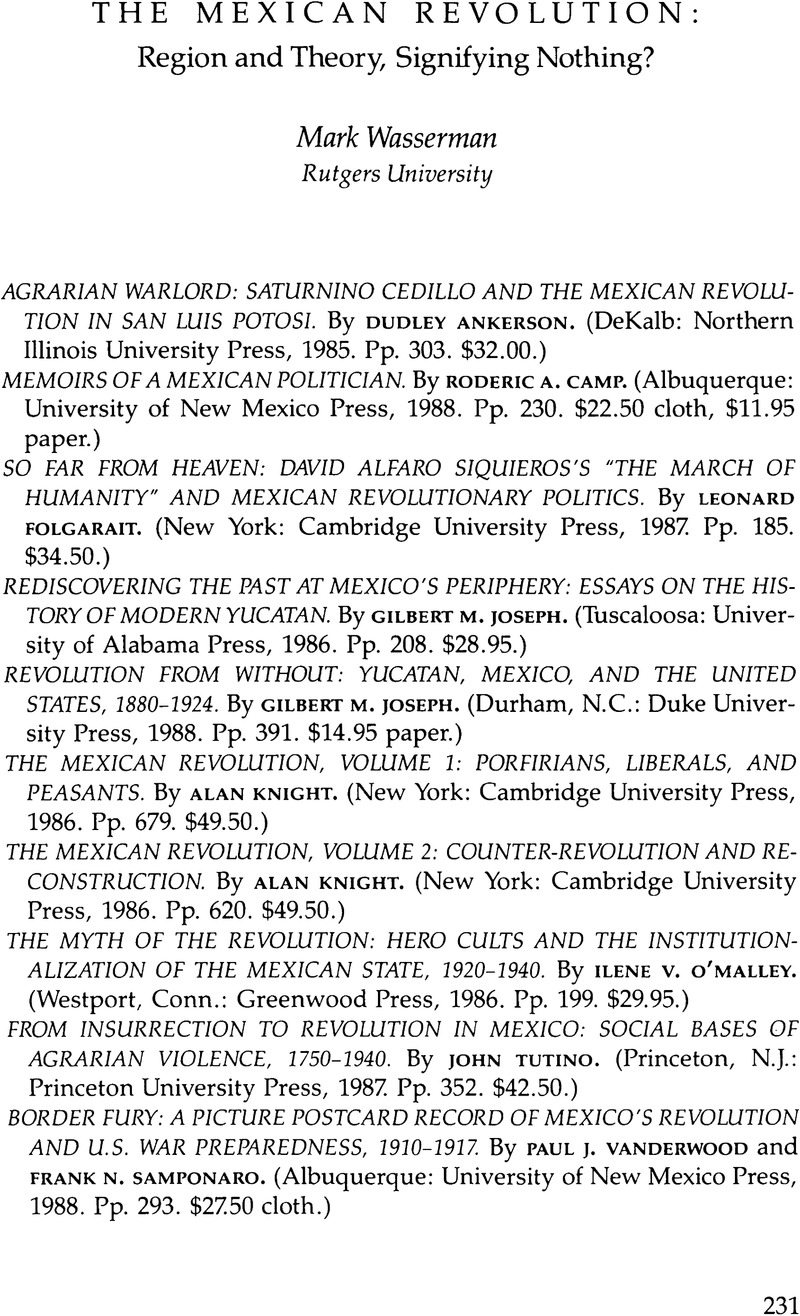

The Mexican Revolution: Region and Theory, Signifying Nothing?

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1990 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Paul J. Vanderwood, “Review of Capitalists, Caciques, and Revolution: The Native Elite and Foreign Enterprise in Chihuahua, Mexico, 1854-1911 by Mark Wasserman,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 88, no. 4 (Apr. 1985):434-35. Earlier Vanderwood asserted that the “the warp and woof of the historical cloth ripped apart in the Revolution of 1910.” See Vanderwood, Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981), p. xii.

2. Richard Morse maintained much the same about periodization that focused on the Wars of Independence. His argument proved persuasive for a generation of historians, judging from the proliferation of recent studies of the late colonial and early independence eras. See “The Heritage of Latin America,” in The Founding of New Societies, edited by Louis Hartz (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1964), 164–69.

3. Ramón Eduardo Ruiz, The Great Rebellion: Mexico, 1905-1924 (New York: Norton, 1980), delineates 1905 to 1924 as his period of study. He ends in 1924 because he thinks that “the rebel masters had consolidated their control” by that time (p. 5).

4. Two excellent studies that do not look backward, although they include introductory chapters, are: Romana Falcon, Revolución y caciquismo: San Luis Potosí, 1910-1938 (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1984); and Heather F. Salamini, Agrarian Radicalism in Veracruz, 1920-1938 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971).

5. John Womack, Jr., Zapata and the Mexican Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1968); and Arturo Warman, We Come to Object: The Peasants of Morelos and the National State (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980).

6. Alan Knight, “The Mexican Revolution: Bourgeois? Nationalist? Or Just a ‘Great Rebellion‘?,” Bulletin of Latin American Research 4, no. 2 (1985):3.

7. Enrique Semo, Historia mexicana: economía y luchas de clases (Mexico City, 1978), p. 299, as cited by Knight in Mexican Revolution.

8. Roger D. Hansen, The Politics of Mexican Development (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972).

9. A compelling case can be made for earlier origins for this struggle. See for example, Stuart Voss et al., Notable Family Networks in Latin America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

10. Rather than enter the difficult debate involved in defining theory, I would propose that for my purposes, a theory provides a means for interpreting cross nationally, while a framework has a more specific use in assisting interpretation of a particular historical phenomenon in one country or region.

11. Friedrich Katz, The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 3–21.

12. Eric Wolf, Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century (New York: Harper and Row, 1968).

13. The weakness of elites as prerequisite for revolution derives from Theda Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

14. Vanderwood purports not to “insist that all regional historians must be engaged in social history.” He goes on to say that regardless of the previous statement, it “is not expecting too much, to be informed, even inspired, by the best thought, methodology, writing and conceptualization of their profession.” Vanderwood, “Building Blocks But Yet No Building: Regional History and the Mexican Revolution,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos (Summer 1987):422. He finds inspiration in the French mentalité school; all else is “tired and well-worn.”

15. Eric Van Young, “Doing Regional History: Methodological and Theoretical Considerations.” Paper presented to the Conference of Mexican and United States Historians, Oaxaca, Mexico, 23–26 Oct. 1985.

16. Eric Van Young, “Mexican Rural History since Chevalier: The Historiography of the Colonial Hacienda,” LAR 18, no. 3 (1983):25. Van Young considers regional history “at once difficult and rewarding to produce” (p. 33). Van Young begins his paper entitled “Doing Regional History” with almost the same quote: “regions are like love— they are difficult to describe, but we know them when we see them.”

17. Van Young, “Doing Regional History,” 2.

18. There are exceptions to be sure. For examples, see William K. Meyers, “Interest Group Conflict and Revolutionary Politics: A Social History of La Comarca Lagunera, Mexico, 1888–1911,” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1979; and Frans J. Schryer, The Rancheros of Pisaflores (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980). I categorize local history as another genre.

19. For the Porfiriato, see W. Stanley Langston, “Coahuila: Centralization against State Autonomy,” in Other Mexicos: Essays on Regional Mexican History, 1876-1911, edited by Thomas Benjamin and William McNellie (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984), 55–76; and all of the essays in Caudillo and Peasant in the Mexican Revolution, edited by David A. Brading (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

20. See Ernest Gruening, Mexico and Its Heritage (New York: Century, 1928), 391–493, which is not included in Ankersons's bibliography; see also two works he cites, Jean Meyer et al., Historia de la Revolución Mexicana, período 1924–1928: estado y sociedad con Calles (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1977); and Lorenzo Meyer, Historia de la Revolución Mexicana, período 1928–1934: el conflicto social y los gobiernos del Maximato (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1978).

21. Mary Sarber, Photographs from the Border: The Otis A. Aultman Collection (El Paso: El Paso Public Library, 1977).

22. Rod Aya, “Theories of Revolution Reconsidered: Contrasting Models of Collective Violence,” Theory and Society 8 (1979):66.

23. Ruiz's The Great Rebellion was based on secondary sources written before the boom in regional history and suffers from not using this body of work.

- 1

- Cited by