No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

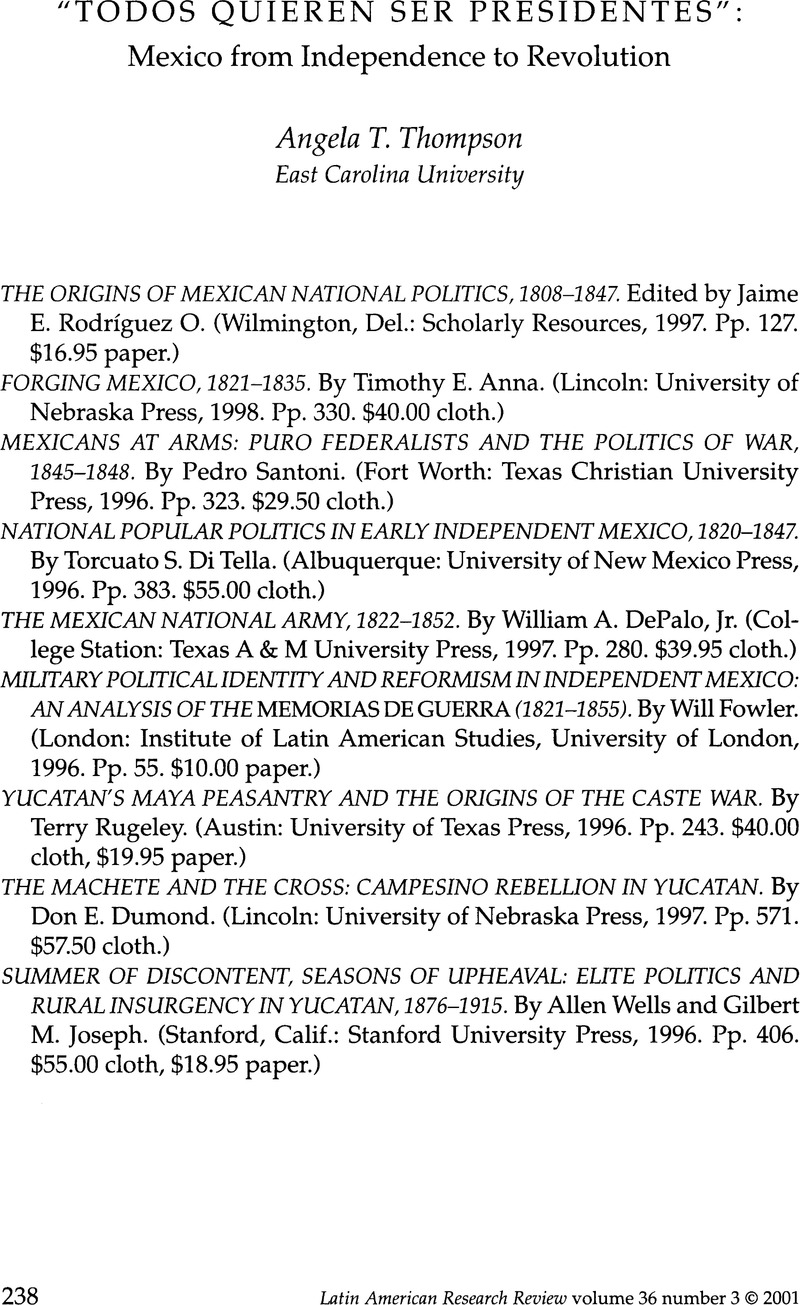

“Todos Quieren Ser Presidentes”: Mexico from Independence to Revolution

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2001 by the University of Texas Press

References

1. Juan Bautista Morales, El gallo pitagórico, with a prologue by Carlos Monsiváis, facsimile reproduction of the original edition printed by Imprenta Tipográfica y Litográfica Ignacio Cumplido in 1845 (Guanajuato, Mexico: Gobierno del Estado de Guanajuato, 1987).

2. Daniel Cosío Villegas, Historia moderna de México: La república restaurada, la vida política (Mexico City: Hermes, 1955); Daniel Cosío Villegas, Historia moderna de México: El porfiriato, la vida política interior, 2 vols. (Mexico City: Hermes, 1970); and Moisés González Navarro, Historia moderna de México: El porfiriato, la vida social (Mexico City: Hermes, 1957). The other multi-authored volumes of Historia moderna de México and numerous individual works by this group of historians also included the work of Emma Cosío Villegas and Luis González y González.

3. Rodríguez has edited another important work on this period: The Independence of Mexico and the Creation of the New Nation (Los Angeles and Irvine: UCLA Latin American Center Publications and the Mexico-Chicano Program, University of California, Irvine, 1989).

4. Nettie Lee Benson, The Provincial Deputation in Mexico: Harbinger of Provincial Autonomy, Independence, and Federalism (Austin: Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas Press, 1992); originally published in Spanish as Diputación provincial y el federalismo mexicano (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1955).

5. See Michael Costeloe, The Central Republic of Mexico, 1835–1846: Hombres de Bien and the Age of Santa Anna (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). In Costeloe's account, Santa Anna comes out as a sometime mediator among all the contending political forces rather than just an opportunistic caudillo.

6. Anna's earlier work on this period includes The Fall of the Royal Government in Mexico City (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978); and The Mexican Empire of Iturbide (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990).

7. Donald Stevens has argued that political leaders like the conservative Alamán and the radical Gómez Farias remained politically consistent in their actions, but their political zeal and determination drove them to any lengths to impose their own political will on the nation. See Stevens, Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1991).

8. See Torcuato S. Di Telia, Latin American Politics: A Theoretical Framework (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990).

9. Di Telia first used the term dangerous classes to refer to various popular Mexican groups that tended to participate in revolts and uprisings in “The Dangerous Classes in Early Independent Mexico,” Journal of Latin American Studies 5, pt. 1 (1973):79–105. In the work under review here, he explores their continuing involvement in Mexican politics after independence. For an explanation why these groups became politicized and insecure and thus bound to participate in insurgent, rebellious activity, see Brian Hamnett, Roots of Insurgency: Mexican Regions, 1750–1824 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

10. Elizabeth Salas has explored the role of soldaderas in greater detail in Soldaderas in the Mexican Military: Myth and History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990).

11. This comment is based on my own reading of ayuntamiento records for the city of Guanajuato in the 1820s.

12. See Nelson Reed, The Caste War of Yucatán (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1964). Another work emphasizing the land question is Moisés González Navarro, Raza y tierra: La guerra de castas y el henequén (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1970).

13. Some of their works include Allen Wells, Yucatan's Gilded Age: Haciendas, Henequen, and International Harvester, 1860–1915 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985); and Gilbert Joseph, Revolution from Without: Yucatán, Mexico, and the United States, 1880–1924, rev. ed. (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1988).

14. Even in the case of the Yucatec Maya, the availability of arms contributed to their ability to mount a revolt and maintain it. It was not until the Maya were forced into the military that they gained the right to carry firearms. Once they obtained this right, the Maya sought arms from whatever source, whether smuggling or legitimate commerce, often through British Belize. It seems doubtful that they could have carried out their revolt for so long with only their machetes.

15. Alicia Hernández Chávez, La tradición republicana del buen gobierno (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1993).