No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

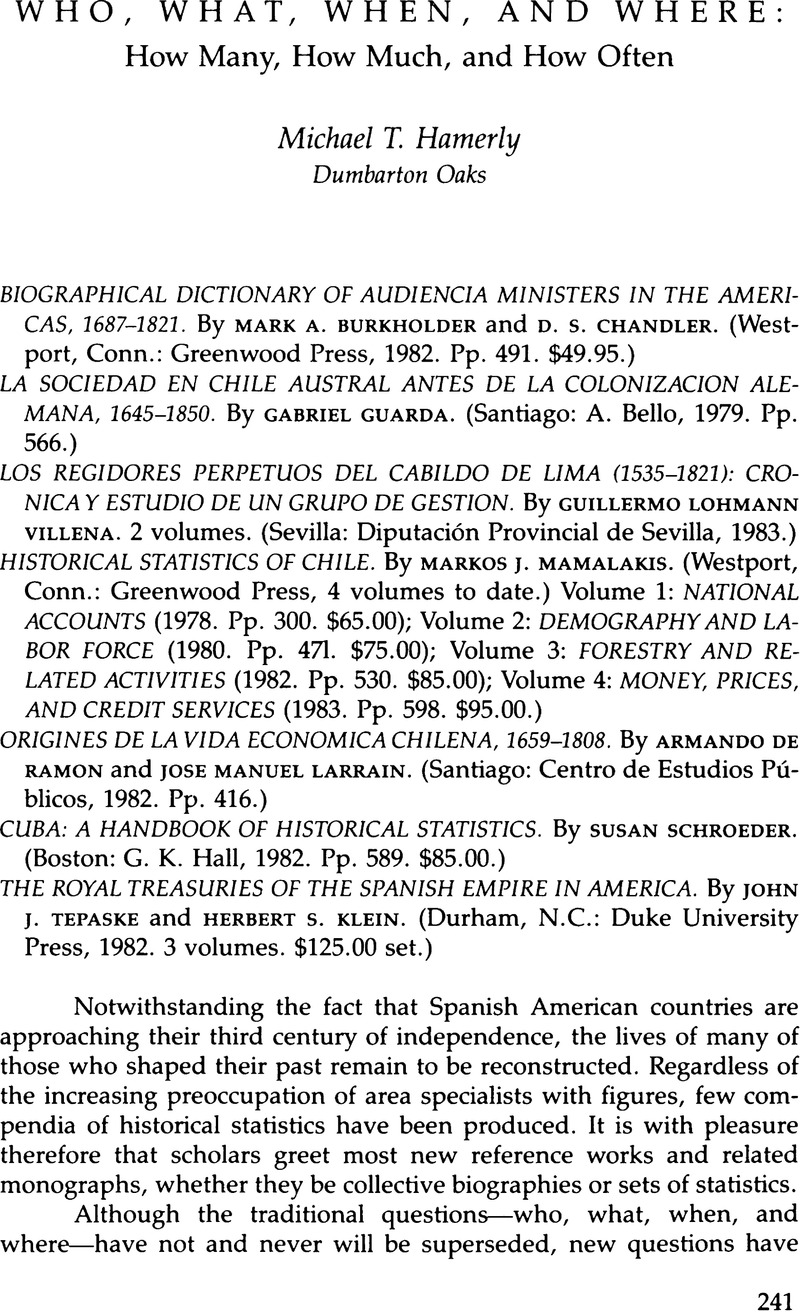

Who, What, When, and Where: How Many, How Much, and How Often

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1985 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. The same is true of his brother Ramón García de León y Pizarro, Governor of Guayaquil from 1779 to 1790.

2. From Impotence to Authority: The Spanish Crown and the American Audiencias, 1687–1808 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1977). Only publishers of works in print are given in this and subsequent notes.

3. Apparently there are only three other biographical dictionaries of audiencia ministers, at least of Spanish South America, all of which are audiencia and period specific: Guillermo Lohmann Villena, Los ministros de la Audiencia de Lima en el reinado de los Borbones, 1700–1821 (Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1974); José María Restrepo Saenz, Biografías de los mandatarios y ministros de la Real Audiencia, 1671 a 1819 (Bogotá: 1952); and Abraham de Silva i Molina, Oidores de la Real Audiencia de Santiago de Chile durante el siglo XVII (Santiago: 1903). Lohmann Villena, however, includes entries on fifty-one “ministros criollos y peninsulares casados con criollas que integraron la Audiencia de Lima en los siglos XVI y XVII.”

4. Los regidores perpetuos includes a chronological chart, but it is keyed by numbers, not by names (1:241–47).

5. John Preston Moore, The Cabildo in Peru under the Habsburgs: A Study in the Origins and Powers of the Town Council in the Viceroyalty of Peru, 1530–1700 (Durham: 1954); and The Cabildo in Peru under the Bourbons: A Study in the Decline and Resurgence of Local Government in the Audiencia of Lima, 1700–1824 (Durham: 1966).

6. Jean Pierre Blancpain, Les Allemands au Chile (1816–1945), Lateinamerikanische Furschugen 6 (Cologne: Bohlau, 1974).

7. Guarda is as competent a historian as he is a genealogist. See his Historia urbana del reino de Chile (Santiago: Ed. A. Bello, 1978), which is as monumental as La sociedad en Chile austral.

8. Apparently the only account books published to date are the Libro común and Toma de cuentas of 1529–38 of the Caja Real of Coro, the oldest royal treasury in Spanish South America. See El primer libro de la Hacienda Pública Colonial de Venezuela, 1529–1538, compiled by Eduardo Arcila Farías, Proyecto de la Hacienda Colonial Venezolana 1 (Caracas: Centro de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1979). TePaske and Klein's time series of cartas cuentas of Potosí would have been far less complete had Peter Bakewell not prepared the equivalent of “about a third” of them, “most of those for the first half of the seventeenth century” from libros manuales or daily ledgers.

9. An excellent introduction to accounts and accounting procedures of the royal treasury system is the little-known 1806 work by José Antonio Limonta, Libro de la razón general de la Real Hacienda del Departamento de Caracas, with an introduction by Mario Briceño Perozo (Caracas, 1962), Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de la Historia 61; Fuentes para la historia colonial de Venezuela.

10. Only a handful of scholars other than TePaske, Klein, and Bakewell have begun to mine royal treasury accounts. In addition to Bakewell's “Registered Silver Production in the Potosí District, 1550–1735,” Jahrbuch für Geschichte von Staat, Wirtschaft und Gesselschaft Lateinamerikas 12 (1975):67–103, see María Luisa Laviana Cuetos, “Organización y funcionamiento de las cajas reales de Guayaquil en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII,” Anuario de Estudios Americanos 37 (1980):313–49; and Javier Tord and Carlos Lazo, Hacienda, comercio, fiscalidad y luchas sociales (Perú colonial) (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 1981). Municipal treasury accounts are even less known and all but virgin. For examples of the extraordinarily detailed, frequently unique data they contain and their importance to the history of towns and their districts, see Alfred Moreno Cebrián, “Un arqueo a la hacienda municipal limeña a fines del siglo XVIII,” Revista de Indias 41, nos. 165–66 (July-Dec. 1981):499–540.

11. I suspect that the answer to this and other chronological questions may be found in the manuscript works of Francisco López de Caravantes, contador of the Tribunal de Cuentas of Lima from 1607 to 1634. López de Caravantes recounts the early history of the cajas reales of Lower and Upper Peru and Quito. See Guillermo Lohmann Villena, “El contador Francisco López de Caravantes y sus obras,” in Memoria del cuarto congreso venezolano de historia del 27 de octubre al 19 de noviembre de 1980, 3 vols. (Caracas: Academia Nacional de la Historia, 1983), 2:157–72; and Engel F. Sluiter, “Francisco López de Caravantes's Historical Sketch on Fiscal Administration in Colonial Peru, 1533–1618,” Hispanic American Historical Review 25, no. 2 (May 1945):224–56.

12. John J. TePaske in collaboration with José y Mari Luz Hernández Palomo, La Real Hacienda de Nueva España: la Real Caja de México (1576–1816) (Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1976), Colección Científica 41. The accounts of the twenty-two other treasuries of Mexico proper will appear in John J. TePaske and Herbert S. Klein, Ingresos e egresos de la Real Hacienda en México (forthcoming).

13. For example, Centro de Estudios Demográficos, Universidad de la Habana, La población de Cuba (Havana: 1976); O. Andrew Collver, Birth Rates in Latin America: New Estimates of Historical Trends and Fluctuations (Berkeley: 1965); Gordon Douglas Inglis, “Historical Demography of Colonial Cuba, 1492–1780,” Ph.D. diss., Texas Christian University, 1979; Kenneth F. Kiple, Blacks in Colonial Cuba, 1774–1889 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1976); United States Bureau of the Census, Cuba: Summary of Biostatistics (Washington, D.C.: 1945); and United Nations, Demographic Yearbook: Historical Supplement (New York: 1978).

14. Larraín's “Movimientos de precios en Santiago de Chile, 1749–1808: una metodología aplicada,” Jahrbuch für Geschichte von Staat, Wirtschaft und Gesselschaft Lateinamerikas 17 (1980): 199–259, preceded Ramón and Larraín's Orígenes. But the former work, Larraín's licentiate thesis, was prepared under Ramón's supervision; and Ramón and Larraín had already begun work on Orígenes as a team.

15. The only other price series of which I know for colonial Chile are those of Marcello Carmagnani, which are data deficient. See, for instance, his incomplete series of flour, dried beef (charqui), and suet prices for 1680–1811, drawn from accounts of the subasta of Valdivia, in Les Mécanismes de la vie économique dans une société coloniale: le Chili (1680–1830) (Paris: SEVPEN, 1973), 319–21. No disparagement of Carmagnani or his valuable pioneering work is intended.

16. For a précis of the original work, see Mamalakis, “Historical Statistics of Chile: An Introduction,” LARR 13, no. 2 (1978):127–37.