Introduction

In Thunder Bay, off the northern shores of Lake Superior, the Ontario government recently built a new consolidated courthouse, with a wing of the building designed to accommodate Indigenous justice methods and procedures. As to the catalyst for this wing of the new courthouse, several people whom I interviewed credited a judge and the court’s Ojibway interpreter/Aboriginal liaison who together pushed the Ministry of the Attorney General to include the idea in their design plans and construction.Footnote 1 During our interview, I learned that the judge had been flying to conduct court in remote northern communities well before Canada’s period of introspection into its colonial legacy, which resulted in part in reforms to sentencing legislation and “the development of Aboriginal justice alternatives” (Rudin Reference Rudin2005, 23) (outlined in greater detail below). Despite a succession of official inquiries, reports, and reforms targeting Indigenous peoples, the judge felt that the levels of violence, poverty, feelings of despair, and conflict with the law in remote First Nations communities were worse than thirty years ago when the judge began work as a lawyer: “It’s been very discouraging. Things are worse now than when I started by a long shot. That’s awful to have to recognize that.”Footnote 2

I was surprised that this judge, who everyone said had taken the position that the new courthouse ought to include a space for Indigenous law, was nonetheless candid about a belief that the circumstances for Indigenous peoples in Canada had not improved.

Let me put it another way. This judge put the idea of a space designed to accommodate Indigenous justice “on the table and kept it there,”Footnote 3 in spite of having witnessed decades of commissions, reports, and legal reforms aimed at improving the lives of Indigenous peoples—which included legal interventions to promote Indigenous approaches to justice—and despite feeling that Indigenous people’s confrontation with the criminal justice system had not improved. Why would the judge promote this project while feeling that First Nations communities in northern Ontario were worse off despite the introduction of other similar legal interventions?

This phenomenon of trying to work through the paradoxical effect of being hopeful about law despite misgivings and awareness of its failings is not limited to Canadian Aboriginal law (Matsuda Reference Matsuda1987; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1988; Dingwall Reference Dingwall2002; Riles Reference Riles2006; Abel Reference Abel2010).Footnote 4 The field of law and development is, or at least should be, notorious for this. Former World Bank staff Deval Desai and Michael Woolcock observe that a “remarkably broad set of actors” believe that justice systems are essential for development (Reference Desai and Woolcock2015, 156). Unfortunately, they write, “enthusiasm for ‘building the rule of law’” does not mitigate “the absence of a coherent track record on which it might be realized” (Reference Desai and Woolcock2015, 156).Footnote 5 Mari Matsuda writes that the “dissonance” of combining “an aspirational vision of law” with deep criticism is a regular part of the experience of racialized people (Matsuda Reference Matsuda1987, 333). Similarly, past president of the Law and Society Association, Richard Abel, tracks a number of past presidents who, while continuing to be key players in the Law and Society Association, express a loss of “faith in the progressive possibilities of law” (Abel Reference Abel2010, quoting Merry 1995, 12).

For years, scholars have brought to our attention the discrepancy between goals and outcomes of law reform projects (Trubek and Galanter Reference Trubek and Galanter1974; Nonet and Selznick Reference Nonet and Selznick1978; Sarat and Simon Reference Sarat, Simon, Sarat and Simon2003; Riles Reference Riles2006; Hacker Reference Hacker2011). Yet legal actors continue to value law as a problem-solving technical instrument (Riles Reference Riles2005; Desai and Woolcock Reference Desai and Woolcock2015; see, e.g., Shapiro Reference Shapiro2011) and repeatedly recommit to using law as a tool for social change (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1988; Stoddard Reference Stoddard1997; Davis and Trebilcock Reference Davis and Trebilcock2008; Abel Reference Abel2010; Nichols Reference Nichols2014; Trubek Reference Trubek2016). How are we to understand this? How is it possible that legal actors continue to work with law while being skeptical of its potential to effect sociolegal change? Are we as legal actors broadly defined generally unaware of law reform failures? Are we engaging in a kind of collective cognitive dissonance?

The argument that I wish to make is complicated and will be one that unfolds over the course of this article, but I will attempt a shortened version here. First, while legal scholars generally credit the American legal realists with the idea that law could be used as a tool to achieve sociolegal goals (Sarat and Silbey Reference Sarat and Silbey1988; Posner Reference Posner1990; Macaulay Reference Macaulay2005, 367; Dagan Reference Dagan2013), the legal realists’ initial stance was more symbolic than nonfictional. Legal realists advocated treating law as if it was a means to an end (Riles Reference Riles2005; Riles Reference Riles, Miyazaki and Swedberg2016; see, e.g., Llewellyn Reference Llewellyn1930, 452). Law as a tool was a metaphor (Riles Reference Riles2005, 980), a fiction like other legal fictions which stated facts “that did not ‘really’ exist” (Pottage Reference Pottage2014, 155).

However, during what Duncan Kennedy calls the second period of globalization of law and legal thought (Kennedy Reference Kennedy, Trubek and Santos2006), the dominant legal consciousness embraced a more literal approach to the law-tool and its ability to effect social change (Summers Reference Summers1982; Kelman Reference Kelman1983; Stoddard Reference Stoddard1997). Thus, second, in forgetting or obscuring the “as if” part of law’s tool-like nature, law reformers (of the rational legal instrumentalist variety) have pushed to the sidelines the symbolic, referential, or expressive form of law (Riles Reference Riles, Merry and Brenneis2004) in favor of the controllable, quantifiable, and measurable instrument (see, e.g., Davis, Kingsbury and Merry 2015; Sarfaty Reference Sarfaty, Merry, Davis and Kingsbury2015). This gives legal actors a sense of control over the tool, belying the much more complicated nature of legal reform and social change through law. In addition, at the same time as law reformers embrace the tool-like nature of law, I suspect that most would never fully divorce themselves from law’s expressive potential.

Would it be prudent for lawmakers and those involved in law reform to embrace the “as if” (Fuller Reference Fuller1930; Riles Reference Riles, Miyazaki and Swedberg2016) and take a more honest approach that recognizes our inability to have full mastery over our legal instrument? Not that this should ever dissuade us from working with law as a tool for social change. Still, I recommend that our “rational lawmakers” (Kennedy Reference Kennedy, Trubek and Santos2006, 45) or rational law-reformers should come to terms with the dual material and expressive aspects of law, particularly as aspects of law reform projects. Moreover, while beyond the scope of this article, it may be that law needs to be instantiated in both its expressive/symbolic and instrumental/material form (Stoddard Reference Stoddard1997, Riles Reference Riles2005; Resnik Reference Resnik2012).Footnote 6

As a way of presenting the ideas described above, I employ the courthouse as an artifact of law that instantiates both material and symbolic import. Specifically, I tell the story of the Thunder Bay courthouse construction project, the Aboriginal Conference Settlement Suite (ACSS), and efforts in Canada to incorporate community-based justice programs into the criminal justice system. The Thunder Bay courthouse provides a useful entry point into broader conversations about law reform because of courthouses’ instrumental and expressive aspects. The courthouse is a “symbol that stands for itself” (Wagner Reference Wagner1986). It has a functional purpose in addition to encompassing and defining collective symbols and larger cultural frames (Wagner Reference Wagner1986, 11). It is therefore a useful artifact to demonstrate the reciprocal and dialectical movement between expression and instrumentality in law (Riles Reference Riles, Merry and Brenneis2004). The courthouse is material and symbolic combined—it is both the physical structure of the building and a representational object meant to embody and convey aspirations of justice. The duality of the courthouse thus serves as a point of departure for challenges to the current preferencing for instrumentalism in law.

This article proceeds as follows. In the next section, I outline this article’s methodological orientation and method of analysis. Following this, I briefly outline the history and context in which the Thunder Bay courthouse project took place. I next describe the courthouse construction project, detailing what took place and the goals that have been articulated for the ACSS and the justice programs it will house. I then explore how courthouses generally are both concretely present and transcendent of their context (Keane Reference Keane1997). The final sections explore what this courthouse project—as a representational structure—can teach us about how legal actors engage with law as a tool.

FOREGROUNDING KNOWLEDGE PRACTICES

This article is part of a larger multi-sited ethnographic project that examines law reform practices by looking at instances of judges’ non-case-related work in the areas of judicial administration and procedural reform (Goldbach Reference Goldbach, Sourdin and Zariski2018). As part of this research, I attended the court opening ceremonies for the Thunder Bay consolidated courthouse in April 2014 and conducted semi-structured interviews in person and by phone with judges, court staff, ministry staff, and law clerks. In addition, I reviewed internal ministry documents and architectural plans, conducted archival research, reviewed reports, and collected photographs and audio recordings of speeches and prayers. While this article focuses on the courthouse in Thunder Bay, I will occasionally refer to examples from significant courthouse projects in Israel, South Africa, and the United States.

The method of analysis emulates the style practiced by Annelise Riles, Marilyn Strathern, and others, exposing knowledge practices and analytic assumptions by thinking through familiar problems “as if” through the “eyes” of the researcher’s objects of study (Strathern Reference Strathern1988; Strathern Reference Strathern2001; Riles Reference Riles2005; Riles Reference Riles2008; Miyazaki Reference Miyazaki, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Pottage Reference Pottage2014). For example, Strathern (Reference Strathern1988) utilizes gender concepts in gift cultures as a way to challenge the anthropologist’s use of the problem–solution form, which presumptively imported to other societies Western concerns about commodity cultures and exchange. To counter the assumption, Strathern uses a strategy of juxtaposition, displacing the problem–solution aesthetic in order to foreground the analytic form as relation to be studied (Miyazaki Reference Miyazaki, Hicks and Beaudry2010).

The method of analysis draws on knowledge practices “out there” as a way to think through familiar problems “here” (Riles Reference Riles2008). If the familiar problem “here” is how to understand legal actors’ ongoing commitment to law as a tool for social change despite lackluster results. “Out there,” the physical, material, and metaphorical aesthetics of courthouse architecture encounter each other in ways that provide a useful backdrop to the interrogation of law reform’s problem–solution form. In particular, I use the dual material and symbolic nature of the courthouse, as evidenced by the Thunder Bay courthouse and the ACSS, as a comparative analogy to make visible the dual tool-like and expressive genres of law, particularly as seen in law reform projects. This article does not strive to assess the effectiveness of this specific legal intervention, at the very least because I argue that current methods of evaluation that are steeped in the problem–solution framework are flawed. Instead, I believe that the Thunder Bay courthouse and the ACSS furnish legal scholars with an opportunity to consider a more expanded and nuanced view of law reform and its effects.

The method of analysis involves highlighting “the relative character of [our] own culture through the concrete formulation of another” (Wagner Reference Wagner1986, 4). In other words, by describing the “culture” of the Thunder Bay courthouse project, I aim to create a sense of contingency for “our” culture of law reform. Wagner describes this as the process of making knowledge practices visible by experiencing a moment of “culture-shock” (Wagner Reference Wagner1986, 9). Venturing into courthouse architecture is an exercise in constructing discrepancy in order to realize and reflect on law reform culture and knowledge practices in using law as a tool for social change. My intention is to displace familiar thinking about law as a tool and highlight the forms of analytic relations in sociolegal thought that are at work but taken for granted.

“CULTURALLY APPROPRIATE” JUSTICE

On April 23, 2014, the Ministry unveiled a new courthouse in Thunder Bay, Ontario (Infrastructure Ontario 2014), featuring a conference area at the southeast part of the building that emulates a roundhouse or healing lodge. In contrast to the United States, which has kept tribal law institutionally separate from the conventional or mainstream legal system (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1997; Washburn Reference Washburn2017), Canada has been attempting to incorporate “culturally appropriate” justice programs into Canadian criminal law (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, iii). Elsewhere I have discussed the history of these efforts (Goldbach Reference Goldbach2015; see also Giokas Reference Giokas1993; Kwochka Reference Kwochka1996; McMillan Reference McMillan2011). The shortened version is as follows.

In the 1980s and 1990s, multiple reform commissions and task forces investigated various problematic aspects of the criminal justice system (Research Directorate 1993). These included the lack of direction of current sentencing procedures and ineffectiveness of deterrence; systemic racism in various parts of the criminal justice system; and overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in prisons (Canadian Sentencing Commission 1987; Ministry of the Solicitor General Canada 1988; Law Reform Commission of Canada 1991; Hamilton and Sinclair Reference Hamilton and Sinclair1991; Ministry of Justice and Solicitor General of Alberta 1991; RCAP 1996a; RCAP 1996b). For example, a task force for the province of Alberta found that, while only representing 4 to 5 percent of the general population, the percentage of inmates classified as Aboriginal was approximately 30 percent (Ministry of Justice and Solicitor General of Alberta 1991, 6-4). Across the country, the story was roughly the same, with people identifying as Aboriginal (Inuit, First Nations, or Metis) being incarcerated at five times that of the general population (representing approximately 3 percent of the population and 16 percent of the population in provincial and territorial prisons) (RCAP 1996a, 29–32).

Task forces and commissions also reported on Indigenous peoples’ feelings of alienation as a result of being subject to a justice system that was foreign, imposed, and not representative (Ministry of the Solicitor General 1988; Giokas Reference Giokas1993; Mandamin Reference Mandamin1993). Reports often focused on the conflict between various First Nations’ and Euro-Canadian principles of justice (Dumont Reference Dumont, Hamilton and Sinclair1990; see also Kwochka Reference Kwochka1996; Green Reference Green1998; Quigley Reference Quigley1999; Proulx Reference Proulx2005), suggesting that feelings of alienation resulted from fundamentally different worldviews and concepts of justice. For example, in a submission to the Public Inquiry into the Administration of Justice and Aboriginal People, James Dumont (Reference Dumont, Hamilton and Sinclair1990) outlined the values and belief systems that shaped the contours of behavior in a justice system. Focusing mostly on AnishinaabeFootnote 7 concepts, Dumont delineated a large “zone of conflict” (Dumont Reference Dumont, Hamilton and Sinclair1990, 29) between Indigenous peoples’ values and resulting behavior on the one hand and the expectations of the Euro-Canadian criminal justice system on the other.

Two developments ensued. First, in the mid-nineties, the government of Canada amended the sentencing provisions of the criminal code.Footnote 8 These amendments brought significant clarification to the principles of sentencing and included opportunities for alternative justice measures such as restorative justice and conditional sentencing (Sections 717 and 742 of the Criminal Code respectively). The new sentencing provisions also included a direction to judges to pay particular attention to “the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders” when considering alternatives to imprisonment (Section 718.2(e) of the Criminal Code; see Roberts and Melchers Reference Roberts and Melchers2003). Recognizing that settler colonialism has an ongoing impact on the social and economic lives of Indigenous people (Rudin Reference Rudin2008), the provision, currently in effect, asks judges to consider the “systemic or background factors which may have played a part in bringing the particular Aboriginal offender before the courts” (R. v. Ipeelee, para. 59). This includes “such matters as the history of colonialism, displacement, and residential schools and how that history continues to translate into lower educational attainment, lower incomes, higher unemployment, [and] higher rates of substance abuse and suicide” (para 60).

Section 718.2(e) has become known as the “Gladue provision,” named after the first Supreme Court of Canada case that challenged the scope of the amendments, R. v. Gladue, [1999] 1 SCR 688. Jamie Gladue, a Cree woman convicted of manslaughter, appealed a trial court decision that Section 718.2(e) did not apply because she did not live on a reserve. In addition to deciding that Section 718.2(e) did not differentiate based on place of residence, the Supreme Court held that judges must use “restraint in the resort to imprisonment” (Gladue 1999, para. 35) and employ alternative approaches that would restore “a sense of balance to the offender, victim, and community” (paras. 60–61). The Supreme Court in Gladue and in its subsequent decisions in R. v. Wells, [2000] 1 SCR 207 and R. v. Ipeelee, [2012] 1 SCR 433 thus endorsed community-based justice programs. The Court recognized that, on their own, sentencing innovations would not solve “the greater problem” of feelings of alienation (Gladue 1999, para. 60); nevertheless, Section 718.2(e) asks judges to approach the process of sentencing differently. Taking into consideration “the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders” also means considering “the types of sentencing procedures … which may be appropriate” because of the offenders’ “particular aboriginal heritage or connection” (Gladue 1999, para. 66, emphasis added; see also Wells 2000, paras. 37–39).

The second development of the early and mid-nineties was the establishment of a fund to support Indigenous community-based justice programs. Justice advocates had argued that the conflict between justice values could be attributed to a history of exclusion of Indigenous peoples from the design and delivery of justice services (Ministry of the Solicitor General Canada 1975). They argued that it was incumbent upon the various institutions involved in the delivery of justice services to incorporate Indigenous peoples’ justice values and methods (Kwochka Reference Kwochka1996). To support this effort, the federal government established the Aboriginal Justice Initiative in 1991 to build capacity for the operation of community justice programs and to “address the disproportionate rate of victimization, crime and incarceration among Indigenous people in Canada” (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 23).

Replaced by the Aboriginal Justice Strategy in 1996 and, as of October 2018, now called the Indigenous Justice Program, the program operates out of the Canadian Department of Justice. Through cost-sharing mechanisms with provincial and local governments, funding supports community-based justice programs such as diversion programs, victim support, and sentencing circles, which are annexed to the Euro-Canadian mainstream criminal justice system (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017). As of 2015–16, funding through the Indigenous Justice Program supported approximately two hundred community-based justice programs providing services to approximately nine thousand people from over 750 communities (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 3). Resources allocated to the program for the five-year period between 2012 and 2017 totaled just under CAD $80 million (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 7).

LOCATING THUNDER BAY

Within this context of promoting and funding “culturally appropriate” justice programs, the Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General set out to build the new courthouse. Ontario is one of the largest and busiest court systems in North America (Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario), Court Services Division 2012, i). In addition, it is home to the largest number of people in Canada who identify as Aboriginal (Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation 2017, 8). Approximately 20 percent of the 1.67 million people who identify as being of Inuit, First Nations, or Metis descent live in Ontario (Statistics Canada 2018a and 2018b), including a total of 133 First Nations communities (Chiefs of Ontario n.d.). A large proportion of this population lives in the major urban centers of Thunder Bay, Sudbury, Sault Ste. Marie, Ottawa, and Toronto (Statistics Canada 2018b).Footnote 9

Designated as a city following the amalgamation of Fort William and Port Arthur in 1970, Thunder Bay is located at the northern rim of Lake Superior, in the western part of Ontario. The history of Thunder Bay and the surrounding region is mired in colonial governance and nonconsensual resource extraction (Roland Reference Roland1887; Wilson et al. 1909; Nishnawbe Aski Nation v. Eden, 2009 259 O.A.C. 1 (Div. Ct.); Comiskey Reference Comiskey2015; Sinclair Reference Sinclair2018). In the early years of settler encroachment on Indigenous lands (Stark Reference Stark2016), the English Hudson’s Bay Company and French North West Company were given exclusive trading rights in the area north and west of Thunder Bay, then known as Rupert’s Land (Arthur Reference Arthur1973, xxi; Miller Reference Miller1989, 117). The North West Company used Fort William as a depot for its trade route along the St. Lawrence Seaway until it merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821.

In the mid-1800s, when the colonial government turned its attention to mining (Roland Reference Roland1887), the Crown Lands Department issued orders-in-council to regulate prospector licenses and mining claims (Surtees Reference Surtees1986). First Nations reacted to unsanctioned prospecting by petitioning and sending letters of complaints. In response, the colonial government sent commissioners to investigate land claims and in January 1850 appointed William Benjamin Robinson to negotiate the purchase of lands surrounding Lake Superior and Lake Huron (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2018). Ultimately, with a total budget of approximately £7,500, Robinson negotiated the purchase of over 50,000 square miles. In addition to circumscribing mineral, hunting, and fishing rights, treaties created a schedule of reserves, twenty-four in total. In 1885 the Sisters of St. Joseph established the Fort William Residential School (also known as the St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School), which operated until 1966. Until the land was expropriated in 1905 it was located on Fort William First Nation reservation land (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2018). During the school’s eighty years of operation, police removed thousands of children from their families in surrounding reserves and communities in order to indoctrinate them into the dominant Euro-Christian Canadian culture.

In 1858, the colonial government created the Provisional Judicial District of Algoma, which included the districts of Thunder Bay, Rainy River, and Kenora (Wright Reference Wright2012). Today, Thunder Bay is the largest community and the main urban center located in the Ministry’s Northwest Judicial Region (Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario), Court Services Division 2012, 13). While it is the largest region geographically, the Northwest Judicial Region contains less than 2 percent of the population in Ontario (Ontario Court of Justice 2011) and has the fewest overall civil, criminal, and family matters (Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario), Court Services Division 2012). Thunder Bay is one of four “base courts” operated by Court Services (Ontario Court of Justice and Ministry of the Attorney General Joint Fly-In Court Working Group 2013). Court Services also manages thirty-six “satellite courts,” most of which are only accessible by air.Footnote 10

BUILDING A NEW COURTHOUSE

In Thunder Bay, the idea to build a consolidated courthouse for the Superior and Ontario Court of JusticeFootnote 11 had been in discussion for approximately twenty-five years.Footnote 12 Previously, the Superior Court of Justice sat at a historic courthouse built in 1924 in Port Arthur, with judges of the Ontario Court of Justice in Fort William at a courthouse built in 1974 (Phillet Reference Phillet2007, 1). With its modest population, Thunder Bay had a small number of lawyers servicing two courthouses. The local law association thus actively supported the idea of consolidating the courts into one location. The law association “took the position that … being separated by ten kilometers and a couple of railway tracks really placed them in an awkward position.”Footnote 13

The Ministry similarly found that “limited judicial and legal resources” were serving two separate courthouses at opposite ends of the city (Phillet Reference Phillet2007, 1). While judges of the Superior Court of Justice would have preferred to stay in their historic courthouse,Footnote 14 nevertheless, limited access to conference rooms and other “courthouse support spaces” led the Ministry to conclude that “serious deficiencies” warranted the construction of an entirely new building (Phillet Reference Phillet2007, 1–3). Under the province’s “Architectural Design Standards for Court Houses,” once the Ministry commits to building a new courthouse, it is directed to consolidate the two levels of trial court into one building (Veskimets and Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario) Reference Veskimets1999, A1). This would have the effect of “creating more functional efficiency … [as well as] collegiality … amongst the Judiciary.”Footnote 15

In its needs-assessment phase, the Ministry also concluded that the existing spaces did not reflect the significant “Aboriginal contextual influence” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 5). Local justice councils were conducting healing circlesFootnote 16 and other justice programs, but they did so in community centers and at the Thunder Bay Indigenous Friendship Centre. The Ministry concluded that without a “dedicated and reliable space,” administering these programs would become increasingly “difficult and inefficient” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 7). In fact, the Ministry projected that while the total population in the region was expected to decrease, the Indigenous population in Thunder Bay would see an increase due to urban migration. That projection compounded with the assessment that 80 percent of matters in front of the Ontario Court of Justice “originate within the aboriginal population” (Phillet Reference Phillet2007, 2) led the Ministry to conclude that it was “important to explore ways that the courthouse design or spaces within the courthouse can respond to this uniqueness” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 5). One Ministry architect referred to this as a “facilities solution.”Footnote 17 Considering the area’s needs projected over the next thirty years, the architect’s operative question was “from a facility’s and from an architectural standpoint, what is it that we can do to help facilitate some of the proceedings and trials that [are] being influenced by the community?”Footnote 18

For their part, judges in the region were alert to the directive issued by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Gladue. As one judge explained:

Well, it became pretty clear … after amendments to the Criminal Code … and the Gladue decisions [sic] in 1999 … and our dockets which are significantly populated with a growing Aboriginal population and the changing demographics of the Aboriginal population in this jurisdiction that we had a lot of work to do in servicing that population. I think Gladue is a big … it was a whack on the head to all of us … that we had to do things differently….Footnote 19

Nevertheless, it appears that the idea to build a space reflecting Indigenous architecture came about in a somewhat happenstance manner. Early in the consultation process, the lead Ministry architect scheduled a meeting with a judge from the Ontario Court of Justice, who in turn invited the court’s Ojibway Interpreter and Aboriginal Liaison. The judge recalled the meeting as follows:

We were talking about various things and I think we were describing the way we set up court in the north, where it’s an open square typically, to mimic as much as we can [a] circle, and how everyone stays seated while court’s on. So lawyers don’t stand to make submissions and will remain seated and we even arraign the accused from a seated position, just to try to lower the formality a little bit, and increase the comfort level…. Somehow, the conversation then moved to what we could do in terms of courtrooms…. And we were lucky because [the architect] got inspired by our chatter, and when we suggested that we have at least one room in this new courthouse that is going to, um, capture traditional Aboriginal spirituality, he said yeah, let’s try to do that.Footnote 20

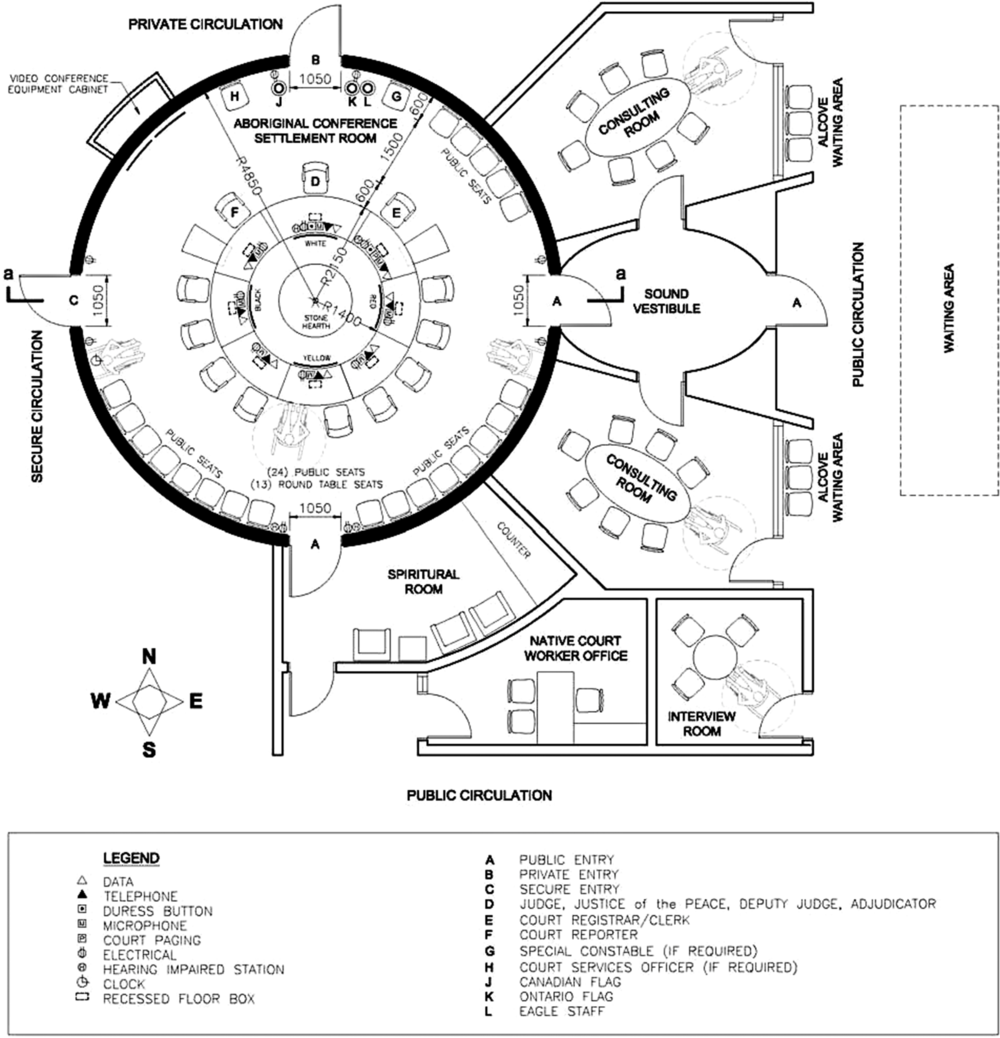

Following that initial meeting, the Ministry architect undertook to learn about different First Nations’ building designs. With introductions from the court interpreter, the architect and a research assistant visited the Sandy Lake Reserve, the Six Nations G.R.E.A.T. Opportunity Business Centre, the Naotkamegwanning First Nation health center, the Rat Portage pow-wow grounds and Anishinaabe roundhouse in Kenora, and the roundhouse in White Fish Bay (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009). At the Sandy Lake Reserve, council and elders recommended a settlement room with “circular shape and ribs, resembling a womb” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009). The elders expressed that it was important “to create a non-judgmental setting that lacks hierarchy” and that “it would be valuable if the space could be used for a number of purposes including sentencing circles, healing circles, and sharing circles” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009). The court interpreter also helped establish a local elders’ committee, which met with judges, court services, and architects throughout the construction process.Footnote 21

Today, the Thunder Bay courthouse houses fifteen courtrooms, including a larger courtroom for multiple offenders, and three settlement rooms. All courtrooms can serve as hearing rooms for either the Superior or Ontario Court of Justice, with changeable signage and rotating judicial coats of arms (Phillet Reference Phillet2007). The Aboriginal Conference Settlement Suite (ACSS) features a circle courtroom designed to emulate an Anishinaabe healing lodge or roundhouse (Sweet n.d.) (Figures 1 and 2), as well as interview and consulting rooms, a Native Court Worker Office, a spiritual room, and public waiting areas (Chiao Reference Chiao2012; Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario), Court Services Division 2012, 53) (Figure 3). The circle courtroom can accommodate sentencing circles, most simply defined as a hybrid between traditional healing circles and a sentencing hearing at the sentencing phase of a criminal trial (Goldbach Reference Goldbach2015). It can also host “case conferencing, pre-trials, Gladue Courts,Footnote 22 family and civil (not in-custody or low-risk in-custody) proceedings, general meetings, or ceremonial events” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 17; see also Rudin Reference Rudin2005). The room has a ventilation system for smudging.Footnote 23 Architects also designed an exterior space with a garden and a circular sitting area for smudging. The ACSS is located on the ground floor close to the courthouse’s main entrance in order to facilitate public access outside of court hours (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009; Sweet n.d.).Footnote 24

Figure 1. The Aboriginal Conference Settlement Suite Settlement Room. Unless otherwise specified, all pictures are my own taken in the field. Copyright Toby S. Goldbach 2020.

Figure 2. Aboriginal Conference Settlement Suite, Settlement Room Ceiling.

Figure 3. Aboriginal Conference Settlement Suite 179.3 sq. m. (1930 sp. ft.) Copyright Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General.

Goals and Objectives

What were the Ministry’s goals and expectations for the Thunder Bay courthouse and the ACSS? Infrastructure Ontario stated that the new courthouse would “improve access to justice … by consolidating the services of existing courthouses within one modern facility” and by increasing the number of available courtrooms (Infrastructure Ontario 2009, n.p.).Footnote 25 As for the ACSS specifically, objectives ranged from inclusion to ameliorating cultural conflict and accommodating restorative justice. The Ministry’s 2009 needs assessment and planning report, for example, states, “From the perspective of the Aboriginal population, the Euro-Canadian justice system is one that is adversarial, alien and in many ways inconsistent with their traditional values. This has bred a significant degree of resentment, disillusionment and animosity” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 5). As for a solution, the report continues, “Perhaps by constructing courthouses and providing architectural spaces that are more culturally relevant, we may increase the willingness of Aboriginals to actively participate in the justice system” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 5).

The Ministry’s 2009 report replays and reconstitutes the problem/solution iterated by multiple tasks forces and commissions in the 1980s and 1990s (see, e.g., Hamilton and Sinclair Reference Hamilton and Sinclair1991; RCAP 1996a; RCAP 1996b). The statistic that 80 percent of Ontario Court of Justice cases in the Northwest Region originate within the Indigenous community (Phillet Reference Phillet2007) is a fact. On the other hand, the problem is configured as an issue of cultural conflict between two (inaccurately characterized as monolithic) justice cultures: a European-based adversarial approach and an “Aboriginal culture [that] takes a holistic approach to justice and seeks to heal and re-establish balance” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 5). Finally, the solution offered is to create a space for the administration of culturally relevant justice programs.

In order to have a complete picture of law reform goals and objectives in this case study, one also needs to examine the expectations of the Indigenous Justice Program as outlined by the federal Department of Justice. In many ways, provincial and federal governments share carriage over the structure and administration of criminal justice. In Thunder Bay, the Thunder Bay Indigenous Friendship Centre administers the Aboriginal Community Council Program and Gladue Services Program, created in 1997 and 2009 respectively (Thunder Bay Indigenous Friendship Centre n.d.). Also in Thunder Bay, the Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services has been running a Restorative Justice Program since 1996 (Nishnawbe-Aski Legal Services Corporation n.d.). In nearby Kenora, a Treaty # 3 Community Justice Centre was recently announced, with implementation expected in 2020 (Grand Council Treaty #3 2018; Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario) 2018). All of these programs receive funding from the federal government. What are the stated goals for these community-based justice programs?

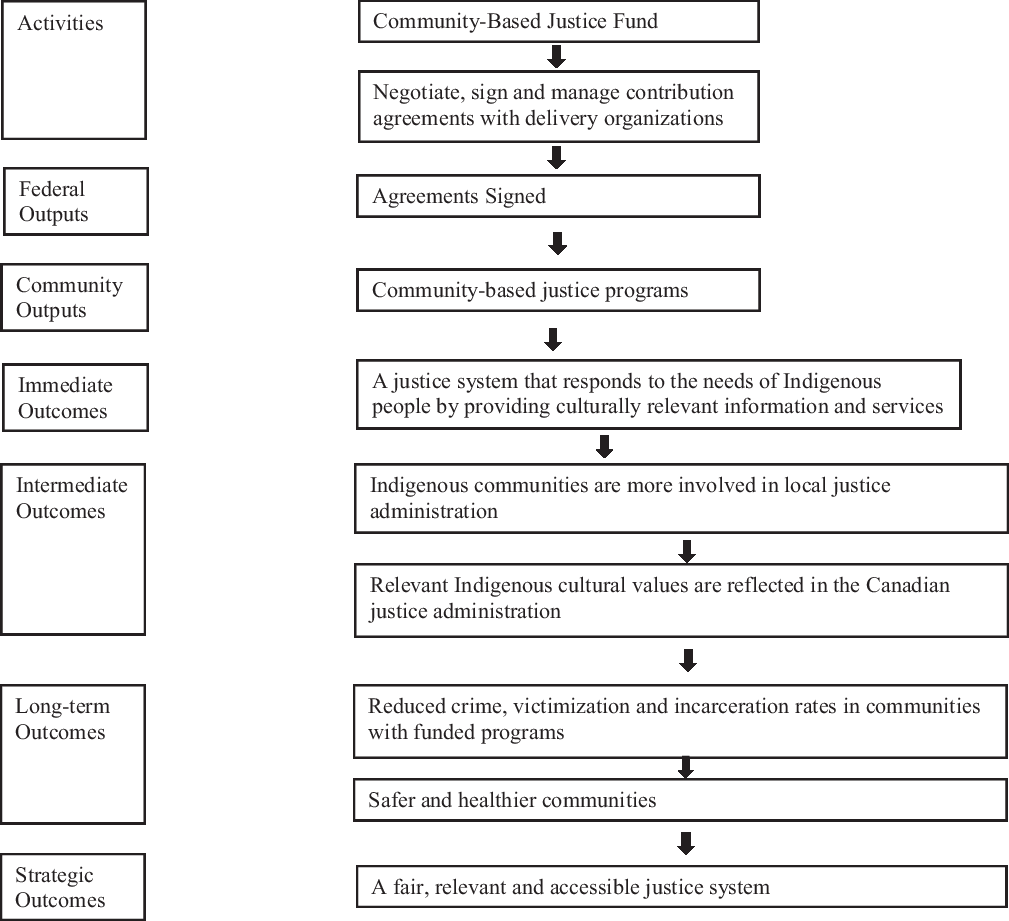

In its most recent project evaluation, the Department of Justice states that the goals of the Aboriginal Justice Strategy (now Indigenous Justice Program) include fostering a “more responsive” justice system so that Indigenous people have “increased access to and participation in culturally relevant, community-based justice programming” (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 12). The project evaluation also states, “In the long term, [these] programs effectively contribute to reducing crime, victimization and incarceration rates in communities with funded programs, as well as to safer and healthier communities” (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 13).

The recent project evaluation also reiterates the problem/solution as articulated in the 1980s and 1990s and summarized above. Here, however, the Department of Justice is more explicit about the expectation that community-based justice programs will reduce incarceration rates. Ironically, the project evaluation states that there is an ongoing need for the Indigenous Justice Program—operating under various names since 1991—because overincarceration of Indigenous peoples persists (Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 23).

In fact, quantitatively, Indigenous people are effectively in the same place as over twenty years ago when many of the legal reforms were first put into place (Roberts and Reid 2017). In 1996–97, people identifying as Aboriginal were incarcerated almost six times more than the rest of the population in Canada (Table 1). Ten years after the significant amendments to the sentencing provisions came into effect that rate decreased slightly, with persons identifying as Aboriginal being incarcerated at 5.3 times more than the overall population. In 2016–17, the most recent statistics that we have, this rate increased and is now the same as it was in the 1990s.

Table 1. Indigenous Persons Incarceration in Canada

Ontario is doing only marginally better, with incarcerated persons identifying as having “Aboriginal identity” totaling 12 percent with a percentage of provincial population at 2.8 percent, yielding a rate of overincarceration of 4.3. As Regional Chief Beardy described at the court opening ceremonies:

It is somewhat a sad day for me. Sad because I think of all my people who are in jail today…. Canada has a good legal system. But there is no justice for First Nations people. [The] justice system does not protect First Nation people. Despite … policy efforts to address the issue of over-representation of First Nations peoples within the criminal and family justice system, statistic show that things are getting worse. Based on statistics of July 2013, I want to share some information with you. Kenora district jail, July 2013 held 139 individuals. One hundred three of them were First Nations people. Fort Francis district jail held nineteen individuals; sixteen were First Nations people. Thunder Bay district jail held 118 individuals; sixty-four were First Nations. Thunder Bay correctional centre held ninety-three individuals; fifty-two were First Nations people.Footnote 34

These statistics will not surprise readers who are familiar with the ongoing impact of colonialism on the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Despite a myriad of sentencing and criminal justice reforms introduced over the last twenty-five years, Indigenous persons continue to be overrepresented in federal and provincial prison facilities (Rudin Reference Rudin2005; Nichols Reference Nichols2014; Reitano Reference Reitano2017; Malakieh Reference Malakieh2018). Similarly, notwithstanding Canada’s support of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, increased legal requirements on the duty to consult, and compensation for mass harms from the Sixties Scoop and Indian Residential Schools (Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada 2018; McKenna 2019), First Nations communities are among the poorest and have some of the highest suicide rates in the world (Patriquin Reference Patriquin2012). Many reside in communities without sewage or running water (Patriquin Reference Patriquin2012; Anaya Reference Anaya2014). And Indigenous children continue to be overrepresented in child welfare systems: 52.2 percent of children in foster care are Indigenous, even though Indigenous children only comprise 7.7 percent of the population of children under fourteen (Reference TaskerTasker 2018).

Why continue to reproduce the same problem–solution aesthetic when the statistics on overincarceration indicate that reforms are not achieving intended outcomes? What can justice advocates expect of the ACSS when sentencing reforms and the Gladue decision have had little impact on incarceration rates?

As-If Outcomes

I put this question as directly as I could to the judge who had pushed for the ACSS. Recall from the introduction that the judge stated in our interview that the socioeconomic circumstances and rates of crime in remote northern communities were worse than when the judge had started traveling to fly-in courts.

Author: I guess my question really is how do you still be optimistic enough to say to [the court liaison], ok, let’s go meet with the architect to try something new, to build an actual physical space … in the courthouse … because you have to somehow be maintaining some level of optimism.

Judge: I think I can answer it this way. I think reserves are a really bad idea. But at the same time I think we need to appreciate how important it is to protect Aboriginal languages, protect and promote them, but make sure people are in a place where they have a chance to be economically independent…. So certainly what was going on in terms of that Aboriginal Conference Settlement Room, it was an opportunity to show Aboriginal people that what they have is valuable in the bigger world, and that they have something to share and that they can be Aboriginal in a bigger community, living in the city and working in the city, going to school, getting a high degree of education, [it] doesn’t mean you have to give up being an Aboriginal person. Footnote 35

When the judge answered, it felt like a moment of sidestepping, or stepping through. I presented the judge with two options: optimism or skepticism (Davis and Trebilcock Reference Davis and Trebilcock2008) about the possibilities of law as a tool. Instead, the judge saw the symbolic statement and diffuse productive power (Barnett and Duval 2005) of legal action and the political contestation in reified formality (Keane Reference Keane1997). Putting aside for the moment the tone of paternalism in the judge’s answer, one can see how the judge walked through and presented a third option that maintained optimism because it moved beyond the immediately quantifiable to something beyond the concrete.

The latest project evaluation of the Indigenous Justice Program did something similar, linking the material and quantifiable to the qualitative and intangible. The evaluation report sets out a “Logic Model” to connect the dots between funding for community-based justice programs and reducing overincarceration (Figure 4). For space reasons, I reproduce the Logic Model in part, focusing on the community-based justice fund, while leaving out the capacity-building and policy development arms of the Indigenous Justice Program.

Figure 4. Logic Model – Aboriginal Justice Strategy (Evaluation Division - Corporate Services Branch 2017, 9).

The evaluation report’s Logic Model moves back and forth between material-based, quantifiable, measurable outcomes—such as incarceration rates—and diffuse qualitative, intangible and possibly immeasurable goals like a fair justice system. Under this view, law is a device, something that you might find on your reformer’s tool belt. Laws are part of the planning mechanisms that society uses to “achieve goods and realize values” (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2011, 119). At the same time, law is also a reflection of values, a tool for intangibles, if not metaphorically a tool (Riles Reference Riles2005).

It is this instinct to merge the two “genres” or “kinds of objectification” of legal knowledge (Riles Reference Riles, Merry and Brenneis2004, 190) that I wish to explore more fully in the next sections. Law has the dual character of being both “a thing in the world” and a reflection or expression of the world (Riles Reference Riles, Merry and Brenneis2004, 190). Law has productive or constitutive power (Barnett and Duval 2005) in its ability to “effectuate meaning” (Riles Reference Riles, Merry and Brenneis2004, 191) and mark groups or objects such as rights, property, or persons (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1988; Strathern Reference Strathern2001; Pottage Reference Pottage2014, respectively).Footnote 36 In addition, an instrumental genre of legal knowledge foregrounds the targets of legal production—law is a means to various ends, such as commercial agreements, property systems, or reduced crime. What we know of and how we use law is often both; law often functions in conversation between pragmatism and representation (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1988). Nevertheless, law reformers tend to direct our attention to “discrete deliverables that can be readily photographed, counted, tracked, aggregated, and compared” (Desai and Woolcock Reference Desai and Woolcock2015, 163). How did knowledge practices in law reform arrive at this place?

Introduction to Metaphorical Tools

For early legal realists and advocates of sociological jurisprudence, the idea of law as a tool for social change was only referential and metaphorical (Riles Reference Riles2005), part of legal scholars’ agenda to get judges to think about the consequences of their decisions and to be transparent about competing interests (Holmes Reference Holmes1896–97; Pound Reference Pound1908; Cohen Reference Cohen1935; Nonet and Selznick Reference Nonet and Selznick1978). Law was a means to the goals and results we wish to achieve in society, “the social ideals by which the law is to be judged” (Cohen Reference Cohen1935, 812). To be a legal realist meant being committed to treating law as (if it was) a tool. As Karl Llewelyn wrote, “only a gain in realism … can come from consistently (not occasionally) regarding the official formulation as a tool … as a means without meaning save in terms of its working” (Llewelyn 1930, 452).

By the middle of the twentieth century, legal scholars’ metaphorical use of means and tools to refer to law “was literalized” (Riles Reference Riles2005, 981).Footnote 37 The legal realist insistence on identifying and evaluating effects (Llewelyn 1931, 1237) morphed into a belief about the rational and targeted use of law to bring about particular social ends (Kennedy Reference Kennedy, Trubek and Santos2006, 21).Footnote 38 In some contemporary legal theory, legal instrumentalism suggests that legal actors can manipulate law to bring about certain ends.Footnote 39 Thus Scott Shapiro refers to the “social planning” function of law (2017, 5) and argues that “legal activity … seeks to accomplish the same basic goals that ordinary, garden-variety planning does, namely, to guide, organize and monitor the behavior of individuals and groups” (Reference Shapiro2017, 8). Rules about legal tender “solve coordination problems” (2017, 8). Laws that regulate pharmaceuticals ensure the safety of patients who may not have capacity to obtain the requisite information. Once you identify the goals that you want to achieve, you can craft and enact Law X (and Law X will be able to achieve those goals).

Yet the law-tool is not (merely) instrumental. In order to demonstrate this dual nature, I return in the next section to the Thunder Bay courthouse, describing its material and symbolic aspects. My suggestion is that a similar oscillation between the symbolic and material happens for the courthouse as it does for law as a tool.

MATERIALITY AND REPRESENTATION IN THE COURTHOUSE

Courthouses are one of the places we use to “make things public” (Dölemeyer Reference Dölemeyer, Latour and Weibel2005)—designated sites where the community comes “together to affirm its values and decide its future (Woodlock Reference Woodlock and Flanders2006, 155). Historically, matters such as the dispensing of laws, settling disputes, or imposing penalties were addressed publicly, often at sites that were significant for their natural landscape. Sites might have had naturally occurring physical features “like megaliths, great trees, large water meadows or fields, clearings or springs” (Dölemeyer Reference Dölemeyer, Latour and Weibel2005, 260). Public spaces might also have been constructed, allowing for larger gatherings in open fields or on mountains or hills.

As the making of law moved indoors, the courthouse grew in significance.Footnote 40 For example, the old county courthouse was a central feature in towns across the United States, serving multiple public functions, such as posting public notices and housing public records, in addition to holding trials (Breyer Reference Breyer and Flanders2006, 11). Planners arranged towns in such a way as to allow not just church steeples but also the upper quarters of courthouses to remain visible to people who approached towns slowly, traveling by horse or foot (Seale Reference Seale and Flanders2006, 37). The historic Superior Court of Justice courthouse in Port Arthur, for example, satisfied this requirement. Set atop a hill overlooking the bay of Lake Superior (Phillet Reference Phillet2007, 96), those approaching Port Arthur by water—one of the main methods of transportation for both private and commercial travel to the area—would have easily seen the courthouse.

More recently, new courthouses have served to support political or socioeconomic goals. In South Africa, judges who were involved in the construction of the Constitutional Court chose to build their new court on the grounds of the notorious Old Fort Prison, where “everybody locked up everybody. Boers locked up Brits, Brits locked up Boers, Boers locked up Blacks” (Law-Viljoen and Buckland 2006). The location was “saturated with a history that bore directly on the themes of human rights” (Law-Viljoen and Buckland 2006).

This section explores the symbolic and material aspects of the courthouse, first describing the symbolic meaning of the courthouse building, as well as the use of representation in design elements. Representational practices in courthouse architecture can sometimes overshadow immediate material considerations (Resnick and Curtis Reference Resnik and Curtis2007). Material concerns can seem crass or unimportant next to grander notions of justice. Yet the symbolic is always connected to “things in the world” (Keane Reference Keane1997, 8). The words, statements, and actions of those involved with the Thunder Bay courthouse demonstrate the importance of the material elements, such as the location of the building or layout of courtrooms. Thus, for example, while most of my interview with the Ministry architect focused on the meaning of the design elements of the building, the politicians’ speeches brought into full view the economic considerations in the construction, location, and financing of the courthouse.

This section ends with a recounting of the court opening ceremonies, a moment of both action and objectification. I argue that, as with the courthouse where differing elements—the symbolic and material—hold together without resolving one into the other (Strathern Reference Strathern1991, 35), so, too, the dual instrumental and intangible possibilities of law as a tool subsist.

What the Courthouse Building Represents

The courthouse is imbued with meaning in the “metaphors and allegorical dimensions of space that mobilize sensation and affect” (Silbey and Ewick 2003, 87). Senior District Judge Woodlock, who worked on the construction of the federal courthouse in Boston, describes the courthouse as “the Law’s citadel of civilized honor” (Woodlock Reference Woodlock and Flanders2006, x). In his article, “Drawing Meaning from the Courthouse,” Justice Woodlock writes that the “open courtroom, where the public has the opportunity to observe formal proceedings for the resolution of its legal disputes” is at the core of US “cultural and constitutional values of democratic transparency” (2006, 155–56).

Judges and architects often speak of justice principles embodied in the courthouse building (Greene Reference Greene and Flanders2006, 63; Resnik and Curtis Reference Resnik and Curtis2011; Resnik, Curtis, and Tait Reference Resnik, Curtis, Tait and Wagner2013; Ananth Reference Ananth2014; Khorakiwala Reference Khorakiwala2018). As the “solid artifice of law” (Haldar Reference Haldar1994, 187), courthouses are meant to project values that are important to the community. Thus, a former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Israel described that country’s decision to move judges out of an old Russian monastery into a new courthouse as an effort to improve the public’s perception of the judiciary and strengthen a “belief in the existence of justice that could defend them, protect them” (Freiman Reference Freiman1993, 80).

Several stakeholders in Thunder Bay noted the important symbolic function of the courthouse. In the needs assessment phase, the consultant found those interviewed “were firm in the communication of the idea that the new courthouse must be representative of the ideals of the justice system” (Phillet Reference Phillet2007, 19). In our interview, the Ministry architect also highlighted the denotive function of the courthouse. While the “primary function” of the courthouse is the delivery of justice, the courthouse is also a “high-profile civil institution” that “represents the community and … the value and importance of that community.”Footnote 41

In his speech at the court opening ceremonies, one the region’s Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) and Minister of Northern Development and Mines, Michael Gravelle, spoke of fairness and justice emanating from the new courthouse:

When you walk into this building … it really is about justice, and it really is about a sense of a fairness that we have every expectation of achieving and reaching…. So this is a great day of excitement, but it’s also one where we get to increase our expectations and our dreams … that seeking … justice for all is alive and well.”Footnote 42

Symbolic Design Elements

Inside the courthouse, design elements bridge the material “workmanship of the courthouse” with principles of justice that the law is meant to embody (Phillips Reference Phillips and Flanders2006, 223). For example, the concave public hall of the Boston federal courthouse, which allows courtroom entrances to be visible to the downtown, is meant to be suggestive of “modern” justice values, including transparency, accessibility, civic engagement, and expressions of “openness and accountability” (Greene Reference Greene and Flanders2006, 63). In South Africa, judges of the Constitutional Court sit at eye level with lawyers, conveying a “sense of equality” so that all are “reminded that people … are not deferring to oracles, they are [all] South Africans” (Law-Viljoen and Buckland 2006, quoting Justice Albie Sachs, 70).Footnote 43 Similarly, design elements inside the Supreme Court of Israel juxtapose “internal and external boundaries” with an effort to “express the connection and reciprocal relationship between the Court and society” (Supreme Court 2017). Another design motif brings together circles and straight lines or squares, which “geometrically plays out the conflict” between justice, described in “biblical scriptures … as a circle provided by god,” and fact, law, or truth, which “is described as a line made by man” (Supreme Court of Israel 2017, 7).

To assist with the design of the new Thunder Bay courthouse, architects consulted with the Eagle Lake First Nation, Naotkamegwanning First Nation, Nishnawbe Aski Nation, the Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto, and the Aboriginal Community Health Centre in order to learn about Cree and Anishinaabe justice principles (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009). The resulting design features of the new building include entrances to the courthouse and to the ACSS facing east “toward the rising sun to symbolize the beginning of life” (Sula and Titus Reference Sula and Titus2014, 109). The ceiling of the center settlement room of the ACSS features a curvilinear layout with features symbolic of a starburst (Figure 2) and the color scheme replicates a medicine wheel: “North=White=Wisdom, South=Yellow=Kindness, East=Red=Honesty, West=Black=Strength” (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009, 19).

Architects also worked with the elders’ committee to design an eagle feather staff and flag, which could be brought out and displayed during appropriate occasions.Footnote 44 The staff includes the animal symbols from the teachings of the grandfathers, as well as depictions of official symbols of provincial and federal governments such as flags, Ontario’s flower emblem (trillium), and the province’s official bird (Common Loon).

On the outside the courthouse, on the external walls where the ACSS is located, there is an etching of the Seven Grandfathers (Figure 5). Indigenous teachings, including beliefs of the Anishinaabe (Bouchard et al. 2009), speak of the original Seven Gifts given by the Grandfathers (Dumont Reference Dumont, Hamilton and Sinclair1990, 4). Stories of the Turtle, Buffalo, Wolf, Bear, Eagle, Sabe, and Beaver represent teachings for Truth, Respect, Humility, Courage, Love, Honesty, and Wisdom, respectively. The teaching on Honesty, for example, explains that,

Long ago, there was a giant called Kitch-Sabe. Kitch-Sabe walked among the people to remind them to be honest to the laws of the creator and honest to each other. The highest honor that could be bestowed upon an individual was the saying “There walks an honest man. He can be trusted.” To be truly honest was to keep the promises one made to the Creator, to others and to oneself. The Elders would say, “Never try to be someone else; live true to your spirit, be honest to yourself and accept who you are the way the Creator made you.” (Alberta Regional Professional Development Consortia 2018)

Figure 5. Courthouse Exterior, Outside the Aboriginal Conference Settlement Suite Area.

The etching features an unbroken line “merging the seven figures into one interconnected” form, depicting how each figure depends “on another for its own formation” (Sweet n.d., quoting Adamson Associates Architects). The architectural firm provides explanations of the design motif and other courthouse art on plaques prominently displayed in the ACSS area (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Courthouse Art, “Change” by Bart Meekis.

Materiality in the Courthouse Building

While the courthouse may represent society’s attempt at “an authentic ‘architecture of justice’” (Phillips Reference Phillips and Flanders2006, 223), it is also “concretely present” (Keane Reference Keane1997, xiii), a physical material space where judges hear cases and write decisions. Immediate “here-and-now” concerns like the location of the building or layout of courtrooms were of fundamental importance to the participants in the Thunder Bay courthouse project. In addition, some of the material aspects were sources of controversy in ways that seem counter to the high ideals represented in design features. These next subsections describe the courthouse’s material elements.

For the site of the new Thunder Bay courthouse, the province and city agreed on downtown Fort William,Footnote 45 an area known for its high rate of crime and low average incomes (Savoie and Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics 2008). The site was a strategic choice to help with the rejuvenation of Thunder Bay’s downtown core (Infrastructure Ontario 2009). As the Minister of Northern Development stated, there were potential benefits “from an economic point of view” of the new courthouse’s location in the south side of Thunder Bay.Footnote 46

Governments often choose to locate new courthouses in depressed parts of municipalities as a kind of “civic engagement” or as an “anchor for urban redevelopment” (Greene Reference Greene and Flanders2006, 76). Examples include various federal courthouses in the United States and the children’s court in Dublin, Ireland. While courthouses may not have clientele or the more “conventional urban development anchors,” they have consistent and stable uses and “provide a 24-hour presence that helps make the neighborhood more secure” (Greene Reference Greene and Flanders2006, 76).

Regrettably, judges of the Northwest Region were not happy with the location of the new building.Footnote 47 As one judge stated:

It was a big fight as to where the courthouse should go. And the government insisted that it be an urban renewal project … so they positioned the courthouse in an area of downtown Fort William that was economically stressed as a deliberate way of rejuvenating the area. But again, many people were upset because they thought that was a ridiculous place to put the courthouse, you know right across street from the massage parlors and the area where the prostitutes gather.Footnote 48

A second economic benefit of the courthouse project was the jobs created by the four-year construction project. At the court opening ceremonies, several government officials noted the courthouse’s role in “boosting” the economy. Local MPP and Minister of Northern Development Michael Gravelle boasted about the number of people who were “working on a construction site for a significant period of time.” Footnote 49 Similarly in his speech, Bill Mauro, MPP and Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, praised his government’s close to one-hundred-billion-dollar commitment toward infrastructure and job creation:

This today is part of and testament to a commitment that we made years ago that started with about a 60-billion-dollar commitment over eight years, with 35 billion more over the next three years to infrastructure in its various forms right across the Province of Ontario. And here in Thunder Bay and Northwestern Ontario, Michael [Gravelle] and I have been very proud to be able to announce a significant number of projects that are benefiting our city and our region and will for years to come, this Courthouse facility in fact being one of them. As I mentioned the efficiency of justice services is the point, it’s the focus of what we’re doing here today, the endgame. But there are significant other benefits that will accrue from the creation of this courthouse. We know that. We know the significant employment was created. Footnote 50

Physical Aspects of the Standard Courtroom

In addition to the importance of the physical location of the courthouse building, the material details of the courthouse interior are also paramount (Ananth Reference Ananth2014). Inside the courthouse, the layout of the courtroom affects the active social practices involved in relaying information, such as sharing documents and receiving oral testimony (Silbey and Ewick 2003). Physical features influence the production of facts and the information that factfinders are able to absorb (Spaulding Reference Spaulding2012; Dahlberg Reference Dahlberg2009; Mulcahy Reference Mulcahy2011; Parker Reference Parker2015). As the early legal realist justice Jerome Frank argued, judges construct facts through the process of a trial. Facts “are not what actually happened between the parties but what the court thinks happened” (Frank Reference Frank1931, 649). Physical features that impact on processes of giving and receiving information are therefore critical to trial outcomes (Rossner, Tait, McKimmie, and Sarre Reference Rossner, Tait, McKimmie and Sarre2017).

Other than ACSS, however, courtrooms inside the new Thunder Bay courthouse follow a standardized layout that the Ministry has been unveiling across the province (Ontario Courts Accessibility Committee 2006; see also Veskimets and Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario) Reference Veskimets1999). During interviews, several judges expressed concerns about the standard design.Footnote 51 One judge took me down to a courtroom so that I could experience it for myself. In order to accommodate wheelchair access, the standard courtroom features a large gap between the dais, as well as a large desk for court clerks, registrars, and transcribers. The judge had me sit in the dais and asked me what I noticed, to which I responded that the lawyer’s table felt far away. The judge agreed and added that the location of the defendant, the “prisoner’s box,” was so far way that the judge was concerned that accused would not feel like part of the proceedings. The judge described a recent bail review hearing with two young accused:

I decided I was going to release them, but I wanted to say to them, because the parents were here: look, your parents are posting a lot of money, don’t let them down because they can’t afford it, and so on. So I was trying to engage them, from the dais, but my sense was it was like shouting down a football field, you know they are so far away that probably they can’t see me…. They’re not close enough, it’s not intimate enough to engage them. Footnote 52

In that courtroom, the chairs for the jury were in a row and bolted to the floor, so that jury members at the far end of the rows might have a hard time hearing and seeing witnesses. The benches for the public were hard wood and had no shape or form to them. “Would you want to sit all day on one of those watching a case?” the judge asked.Footnote 53 In addition, the chair in the witness box was low in comparison to the exterior of the box. This could affect the ability of a judge or jury to hear the witness and see facial expressions or other visual information that comes from witness testimony. The judge noted that sightlines were particularly poor for a witness who may be looking down and slumping as a result of being upset or embarrassed. Footnote 54

Other judges also expressed concern about the distance between the judge’s dais and the public watching the court proceedings:

But what I don’t like about the standard courtroom is how far away people are from the judge. I think that’s a big mistake. I think that what happened is the designers were listening to all kinds of users, and so they ended up giving the clerk’s reporters a lot more working space, but at the price of moving everybody else farther away from the judge. And it seems to me that this was the wrong tradeoff.Footnote 55

Courtroom formations can reflect exogenous interests such as budget constraints, jurisdictional preferences (Rossner, Tait, McKimmie, and Sarre Reference Rossner, Tait, McKimmie and Sarre2017), and, as in this case, accessibility requirements. This physical material layout regulates the experiences of judges and court participants, notwithstanding the impact of symbolic design elements.

Ceremonial Encounters

To celebrate the completion of the construction project, the Ministry’s Court Services Division hosted opening ceremonies on April 23, 2014. Then Attorney General Madeleine Meilleur and Deputy Attorney General Patrick Monahan attended, as did Ontario Regional Chief Stan Beardy and Cathy Rodger, Councilor from Fort William First Nation (attending on behalf of Chief Georjann Morriseau). Other local politicians also participated, including MPP for Thunder Bay/Superior North Michael Gravelle, MPP for Thunder Bay/Atikokan Bill Mauro, and Mayor of Thunder Bay Keith Hobbs. Judges from both courts attended but did not participate in the procession or other ceremonial events.

The court opening ceremonies began with drumming and prayers outside in the courtyard. Immediately following the drumming and prayers, Court Services Division conducted a gift exchange between politicians and local elders. The exchange was hurried and conducted with little notice. Staff from Court Services Division had moved the gifts indoors because, even though it was the end of April, it was too cold, and everyone had moved inside. As the rest of the hall was set up with rows of chairs for the speeches, staff were forced to place the tables with the gifts under the stairs and off to the side. The ceremony was unclear to the participants, and each did different things when they received their gifts. The deputy attorney general tried to look inside his bag and dropped it. The attorney general’s aide kept checking her schedule to make sure the politicians kept to their itinerary, which also included a tour of the new courthouse and the ACSS.

Following the gift exchange and tour, members of local First Nations led a procession through the courthouse atrium. At the front of the procession was Regional Chief Stan Beardy, who held the ACSS eagle feather staff and flag (Figure 7) and a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in full regalia. Drummers at the front of the room played for the procession. The attorney general and some of the other politicians danced as they proceeded to a temporary stage at the front of the room. The deputy attorney general, still holding his gift bag, walked to the podium. The rest of the attendees—the media, as well as Crown prosecutors and Court Services staff who have offices in the new building—stood and watched, taking pictures and recording the dancers with phones and cameras. The day’s events also included a ribbon-cutting ceremony as well as speeches from local politicians.

Figure 7. Regional Chief Stan Beardy with Eagle Feather Staff and Flag at Thunder Bay Courthouse Opening Ceremonies.

Webb Keane (Reference Keane1997) reminds us that signs and symbols are often subject to the hazards and vicissitudes that accompany material objects. Thus, what was meant to be a public gift exchange ceremony to commemorate the collaboration between the Ministry and the Indigenous community that had taken place over the previous four years was instead an awkward and mostly invisible encounter. The dancers’ performance was also subject to a kind of hazard. Most of the audience, positioned on stairs above or on the floor of the atrium, watched and took pictures. This effectively put culture on display. What should have signified a celebration and acceptance of local Indigenous culture felt instead like a spectacle demonstrating “racialized hierarchy” (Nichols Reference Nichols2014, 442) and a vast chasm between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

The courthouse, the design elements of the building, and even the court opening ceremonies are artifacts intended to convey a connection to socially symbolic reference points (Wagner Reference Wagner1986) like justice, fairness, order, or inclusion. However, the vulnerability of material objects (Keane Reference Keane1997, 32)—the incongruity of the courthouse’s surrounding neighborhood, the cumbersome setup of the standard courtroom, and the palpable awkwardness of the opening ceremonies—prompts us to recall the dual nature of the courthouse.

Recognizing Metaphorical Tools

Whereas in courthouse architecture, symbolic and expressive elements tend to predominate (Breyer Reference Breyer and Flanders2006; Phillips Reference Phillips and Flanders2006; Resnik and Curtis Reference Resnik and Curtis2011), law reform and law and development projects often hone in on measurable targets such as signing on to human rights treaties, establishing property regimes, or developing community justice programs (Davis, Kingsbury, and Merry Reference Davis, Kingsbury and Merry2012; Department of Justice 2017). Reform projects and evaluation criteria can overestimate law’s instrumentality while ignoring its expressive form. To instrumentalists, law is “a kind of technology that social engineers use to serve goals” (Summers Reference Summers1982, 193). However, even though the idea of law as a tool was made popular through legal realist calls to identify and evaluate effects (Llewelyn 1931, 1237), their critique of legal formalism was not meant as a statement about the ability of law to effect social change.

For a variety of reasons that are beyond the scope of this article, it seems that we are bringing back the immeasurable, holistic, or intangible when we speak of law reform goals and objectives. Alongside efforts to quantify development objectives (Davis, Kingsbury, and Merry Reference Davis, Kingsbury and Merry2012; Sarfaty Reference Sarfaty, Merry, Davis and Kingsbury2015), theorists and practitioners have been advancing the notion of “comprehensive development” (Wolfensohn Reference Wolfensohn2005; see, e.g., Reference SenSen 2000; World Bank 2002; Rittich Reference Rittich, David and Santos2006). This move in development literature has parallels to Canadian criminal justice reforms, which sought—and continue to seek—to address disproportionate incarceration rates and Indigenous peoples’ feelings of alienation (Ministry of Justice and Solicitor General of Alberta 1991; RCAP 1996a; Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017, 72). Law reform targets and outputs now include the not-material and intangible. Yet lawmakers and legal scholars continue to insist that law is a tool that one can manipulate and control (Stoddard Reference Stoddard1997; World Bank 2002; Shapiro Reference Shapiro2011, Reference Shapiro2017; Evaluation Division of the Corporate Services Branch 2017). Moreover, while legal actors seek intangible outcomes, we continue to emphasize positivistic methods of review and analysis (Sarat and Simon Reference Sarat, Simon, Sarat and Simon2003).

Law as a tool for social change is employed in an effort to reimagine “the present from the point of view of the future” (Riles Reference Riles, Miyazaki and Swedberg2016, n.p.). Power and hope inhere in “potential capacities” and the prospect of reorienting failure and reversing disappointment (Katzenstein and Seybert Reference Katzenstein and Seybert2018). In other words, it is precisely the unknowable, the uncertain, the fictional, immaterial, and symbolic that engage and generate hope. It is time to admit that our “tool” is both real and symbolic (and that it may need to be both).

Conclusion

Writing shortly after World War II, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno (Reference Horkheimer and Adorno1973) criticized what they saw as a singular focus of rationality and enlightenment thinking that put calculability and utility over everything else. They likened enlightenment thinking to a dictator who knows its subjects only “to the extent that he can manipulate them” (Horkheimer and Adorno Reference Horkheimer and Adorno1973, 6). Moreover, they argued, rationalists’ complete confidence in managing the world through the use of science and technology was reminiscent of pre-Enlightenment myths and “magical incantations” (7).

In law reform projects, quantifiable elements like the number of courtrooms or the amount of money spent to construct a new courthouse “give a nice feeling for dealing with the phenomenal universe in the precise, accountable, predictable ways in which we like to think we run our own shop” (Wagner Reference Wagner1986, 4). These measurable elements of law reform attend to our desire for agency in working to effect change. Governments can then assert that building a new courthouse or culturally relevant architectural space will increase access to justice (British Columbia Attorney General 2017; Infrastructure Ontario 2018) and facilitate Indigenous peoples’ active participation in the justice system (Chiao and Hingston Reference Chiao and Hingston2009).

Unfortunately, uncertainty is pervasive. Law reformers and legal scholars long to “put the unexpected aside” (Katzenstein and Seybert Reference Katzenstein and Seybert2018, 4). Yet unanticipated and unintended consequences of law reform efforts are far from exceptional (Abel Reference Abel1982; Hunt Reference Hunt, Banakar and Travers2002). Peter Katzenstein and Lucia Seybert argue that in international politics, “Actors at the front lines of financial, humanitarian, energy, environmental, and other political crises routinely acknowledge the pervasive intermingling of the known and unknown” (Katzenstein and Seybert Reference Katzenstein and Seybert2018, 4). Similarly, in law and law reform, scholars routinely demonstrate complexity and the unexpected in the areas of human rights (Stoddard Reference Stoddard1997; Riles Reference Riles2006), legal transplants (Shaffer Reference Shaffer2012; Goldbach Reference Goldbach2015), and development (Trubek and Galanter Reference Trubek and Galanter1974; Sarfaty Reference Sarfaty, Merry, Davis and Kingsbury2015).

In Thunder Bay, unanticipated events have brought into view the dangers of presuming a direct line from law reform inputs to output imperatives. In 2015, the Ontario government convened a joint inquest to investigate the deaths of seven First Nations high school students who died between 2000 and 2011 while living in Thunder Bay. The police were slow to respond to reports of missing youth and evidenced racist attitudes, for example by remarking that a youth was partying “like any other native kid” (Sinclair Reference Sinclair2018, 37). Just a year before the inquest, the ACSS had been celebrated as the first of its kind, yet the coroner did not conduct the inquest in the ACSS settlement room and instead scheduled a small courtroom that had capacity for only ten observers. The community saw the room assignment as insulting, “a continuing injustice” (CBC 2015). Nishnawbe Aski Nation Grand Chief Alvin Fiddler publicly criticized the choice of room: “You know we have lots of room for First Nations peoples in jails…. But when it comes to access to the courtroom, there’s no room at all” (CBC 2015).