No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

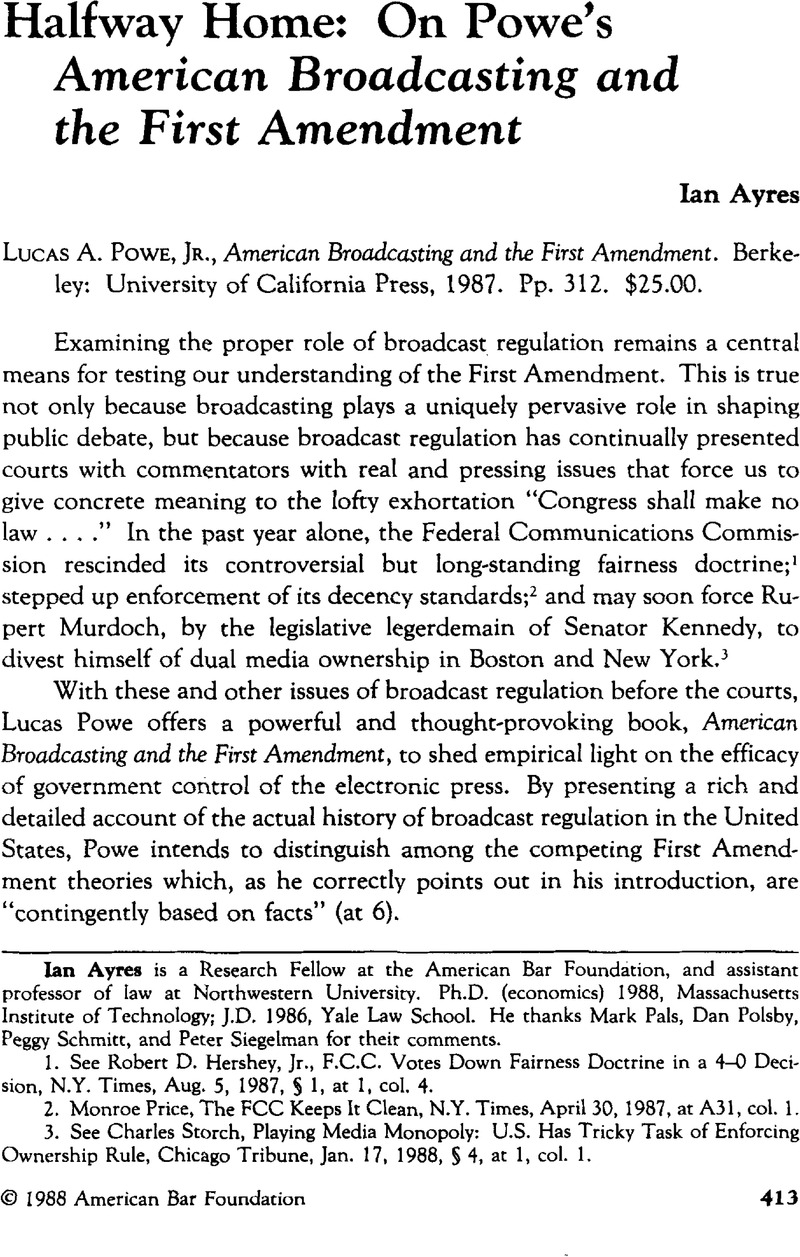

Halfway Home: On Powe's American Broadcasting and the First Amendment

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 December 2018

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Bar Foundation, 1988

References

1. See Robert D. Hershey, Jr., F.C.C. Votes Down Fairness Doctrine in a 4-0 Decision, N.Y. Times, Aug. 5, 1987, § 1, at 1, col. 4.Google Scholar

2. Monroe Price, The FCC Keeps It Clean, N.Y. Times, April 30, 1987, at A31, col. 1.Google Scholar

3. See Charles Storch, Playing Media Monopoly: U.S. Has Tricky Task of Enforcing Ownership Rule, Chicago Tribune, Jan. 17, 1988, § 4, at 1, col. 1.Google Scholar

4. See, e.g., Schauer, Frederick, Free Speech and the Demise of the Soapbox (Book Review), 84 Colum. L. Rev. 558, 559 (1984).Google Scholar

5. Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. Federal Communications Commission, 395 U.S. 367 (1969).Google Scholar

6. Id. at 387-88. White elaborated: “Before 1927, the allocation of frequencies was left entirely to the private sector, and the result was chaos. It quickly became apparent that broadcast frequencies constituted a scarce resource whose use could be regulated and rationalized only by the Government. Without government control, the medium would be of little use because of the cacophony of competing voices, none of which could be clearly and predictably heard.” Id. at 375-76 (footnote omitted).Google Scholar

7. See Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241 (1974).Google Scholar

8. 80 Harv. L. Rev. 1641 (1967).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

9. Id. at 1666. Professor Owen Fiss goes beyond Barron's access theories to suggest that government will at times need to limit some speech to ensure that other voices will not go unheard. See Fiss, , Free Speech and Social Structure, 71 Iowa L. Rev. 1405 (1986). See also Powe, , Scholarship and Markets, 56 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 172 (1987) (criticizing Fiss's theory).Google Scholar

10. 418 U.S. 241.Google Scholar

11. Lee Bollinger, C. Jr., Freedom of the Press and Public Access: Toward a Theory of Partial Regulation of the Mass Media, 75 Mich. L. Rev. 1 (1976).Google Scholar

12. Powe at 5 (citations omitted) (quoting Bollinger, 75 Mich. L. Rev. at 36, 27, 36).Google Scholar

13. Under Powe's theory, society extends First Amendment protection only after the new speakers have gained society's respect. To support this thesis Powe points out how even Milton, one of the first great exponents of the virtues of a free press in his Areopagitica, “did not find the licensing of newsbooks inconsistent with freedom of the press” (at 2). Powe explains: “Newsbooks were, at the time, a relatively young phenomenon, initially introduced only thirty years before. … Milton could easily distinguish newsbook authors from thoughtful, serious people who gave, as he himself did, time and care to their work” (at 2-3). Similarly, Powe suggests that the courts initially refused to extend radio First Amendment protection because radio broadcasts “were much closer to circus acts” (at 29); see Trinity Methodist Church v. FRC, 62 F.2d 850, 851 (D.C. Cir. 1932). Powe extends this thesis not only to the development of cable, but to our current attitudes as to whether a child playing Pac-Man is “having a First Amendment experience” (at 23). Powe's descriptive thesis can interestingly be tied to those of Professors Meiklejohn and Bork, who prescriptively have suggested that absolute free speech protection might be limited to public or political discourse; see A. Meiklejohn, Free Speech and Its Relation to Self Government (1948), and Robert H. Bork, Neutral Principles and Some First Amendment Problems, 47 Ind. L.J. 1 (1971). Powe's theory might be seen as a dynamic analog to those theories whereby purveyors of new forms of communication gain protection only when they begin to seriously concern themselves with governmental affairs.Google Scholar

14. Shuler, a self-described “scrapper for God,” broadcast from a one-kilowatt station in Los Angeles (at 13-15). In 1930 the Federal Radio Commission refused to renew his license because his attacks on local public officials were, in the commission's words, “sensational rather than instructive” (at 16; quoting Trinity Methodist Church v. FRC, 62 F.2d 850, 853 (D.C. Cir. 1932)).Google Scholar

15. Dr. Brinkley's epithet derives from his advertised practice of implanting the gonads of a young Ozark goat into the scrotum of a patient to increase his (the patient's) libido. In 1930 the Federal Radio Commission refused to renew his license (Powe at 26).Google Scholar

16. See Bollinger, 75 Mich. L. Rev. at 33 (cited in note 12). Bollinger's partial-regulation thesis is deserving of such attention because it, according to Powe, “swept the legal academy … becoming the standard citation in any discussion of the topic” (at 5).Google Scholar

17. See Powe at 4: “Nor is this a book extolling the successes of American broadcasting, although to be sure there have been many.”Google Scholar

18. Powe understandably fails to define his phrase “served us well.” Notions of efficiency or wealth maximization have little empirical content in the First Amendment context. More fundamentally, it is impossible to aggregate the disparate preferences of society in a unified maximand. See K. Arrow, Social Choice and Individual Values (1951); In re Changes in the Entertainment Formats of Broadcast Stations, 57 F.C.C. 2d 580, 598 (1976).Google Scholar

19. The “Love Boat” image of First Amendment failure was first articulated by Professor Fiss. See Fiss, 71 Iowa L. Rev. at 1411 (cited in note 10).Google Scholar

20. Our First Amendment “tradition” of securing and extending the right of free speech arguably only has the recent pedigree of Holmes's opinions in the 1910s and 1920s. See, e.g., Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting). See generally H. Kalven, A Worthy Tradition (1988).Google Scholar

21. A similar slanting of the cost-benefit balance can be found at times in the writings of Judge and Professor Richard Posner: “This slanting of the empirics rises sometimes to theoretical proportions as [Posner] ignores entire well-accepted categories of costs or benefits.”Donohue, John & Ayres, Ian, Posner's Symphony No. 3: Thinking About the Unthinkable, 39 Stan. L. Rev. 791, 801 (1987).Google Scholar

22. Controversies concerning the fairness doctrine transcend the FCC's August repeal of the rule. 52 Fed. Reg. 3176 (August 24, 1987). Even before the FCC's action, the House and the Senate had passed a bill, S. 742, codifying the doctrine. On June 20, 1987, President Reagan vetoed the measure, calling it “antagonistic to the freedom of expression guaranteed by the First Amendment.” Fairness Doctrine Vetoed, The Week in Congress (CCH) No. 25, at 1 Uune 26, 1987). Subsequent to the FCC's repeal, the House in December attached another codification of the fairness doctrine to a $593 billion appropriations bill. House Passes All-in-One Appropriations Bill, 45 Cong. Q. 2972 (Dec. 5, 1987). This so-called Dingell amendment was subsequently sent to the Senate and defeated on the Senate floor. See 133 Cong. Rec. §§ 17719-20 (daily ed. Dec. 10, 1987). At this writing, Congress has failed to pass a srarutory codification of the doctrine.Google Scholar

23. 395 U.S. at 369.Google Scholar

24. See Thomas G. Krattenmaker & Lucas A. Powe, The Fairness Doctrine Today: A Constitutional Curiosity and an Impossible Dream, 1985 Duke LJ. 151.Google Scholar

25. Powe at 43-44; see also Red Lion, 395 U.S. at 393-94.Google Scholar

26. Powe suggests that White's arguments against the existence of a chilling effect must be based on the assumption that broadcasters are “a durable lot and would be undaunted” or are “a heartier breed than print journalists” (at 44, 45). This is one of a few instances in the book in which rhetorical excess eclipses Powe's analytics. White's theory belies any notion that broadcasters are heartier than print journalists. Instead, it assumes that, in following their self-interest, broadcasters will respond to incentives under the regulatory regime.Google Scholar

27. It should be noted that Justice White did not rely wholly on the fulfillment of the government's promise: “And if experience with the administration of these doctrines indicates that they have the net effect of reducing rather than enhancing the volume and quality of coverage, there will be time enough to reconsider the constitutional implications.” Red Lion, 395 U.S. at 393.Google Scholar

28. Inquiry into Section 73.1910 of the Commission's Rules and Regulations Concerning the General Fairness Doctrine Obligations of Broadcast Licensees, 102 F.C.C. 2d 143 (1985); see also Krattenmaker & Powe, 1985 Duke L.J. at 165-66 (cited in note 24).Google Scholar

29. The recent demise of the fairness doctrine was, in fact, only a rescission of the diversity branch, as broadcasters are still required “to meet local needs as a condition for holding a license.” Hershey, Aug. 5, 1987, N.Y. Times, S 1, at 1 (cited in note 1). The FCC decision also does not affect the equal time rule for competing federal political candidates; the personal attacks rule (requiring stations to offer individuals who are personally attacked during a discussion of a controversial issue a reasonable opportunity to respond); or, the political editorial rule (requiring a station taking an editorial position against a political candidate to provide a response). IdGoogle Scholar

30. Telecommunications Research and Action Center v. F.C.C., 801 F.2d 501, 516 (D.C. Cir. 1986) (“In practice, … the Commission exercises very limited review of … the obligation to devote an adequate amount of time to the discussion of public issues”).Google Scholar

31. Id.; Fairness Report, 48 F.C.C.2d 1, 9 (1974).Google Scholar

32. Bollinger, 75 Mich. L. Rev. at 33 (cited in note 12) (“broadcasters may initially have been reluctant to cover Watergate events because of fears of official reprisals and access obligations, but a decision not to cover the story would have been impossible once the print media began exploring it”).Google Scholar

33. Powe at 138: “The total time devoted on the news to all Watergate coverage on NBC was slightly over forty-one minutes; ABC had sixty-five seconds more.”Google Scholar

34. Powe at 106-7: “Commission decisions favor, first, the president over all others and, second, incumbents over challengers.”Google Scholar

35. For various expositions of capture theory, see Stigler, George, The Theory of Economic Regulation, 2 Bell J. Econ. & Mgmt. Sci. 3 (1971);Peltzman, Sam, The Growth of Government, 23 J.L. & Econ. 209 (1980); Gabriel Kolko, Railroads and Regulation: 1877-1916 (1965); Wiley, John Shepard Jr., A Capture Theory of Antitrust Federalism, 99 Harv. L. Rev. 713 (1986).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

36. See, e.g., Hilton, George W., The Consistency of the Interstate Commerce Act, 9 J.L. & Econ. 87, 113 (1966); Richard E. Caves, Air Transport and Its Regulators (1962); Plott, Charles R., Occupational Self-Regulation: A Case Study of the Oklahoma Dry Clearners, 8 J.L. & Econ. 195 (1965).Google Scholar

37. See Ayres, Ian, How Cartels Punish: A Structural Theory of Self-enforcing Collusion, 87 Colum. L. Rev. 295, 296 (1987).Google Scholar

38. Id. at 298-304.Google Scholar

39. See Krattenmaker, Thomas G. & Salop, Steven C., Anticompetitive Exclusion: Raising Rivals' Costs to Achieve Power over Price, 96 Yale L.J. 209 (1986) (describing “ring- master” theory of collusion).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

40. In a series of rulemaking proceedings, the FCC applied antitrust analysis of market power to the telecommunications market and eliminating regulations for certain nondominant carriers. See In re Policies and Rules Concerning Rates and Facilities Authorizations for Competitive Carrier Services (CC Docket 79-252), Notice of Inquiry and Proposed Rule Making, 77 F.C.C.Zd 308 (1979), First Report and Order, 85 F.C.C. 2d | (1980). For a general discussion of the ensuing proceedings, see MCI Telecommunications, 765 F.2d at 1188-89.Google Scholar

41. Under the regulations adopted by the FCC, MCI and Sprint are not subject to tariff-filing regulations. Fourth Report and Order, 95 F.C.C. 2d at 578-79.Google Scholar

42. Bollinger, 75 Mich. L. Rev. at 33 (cited in note 12).Google Scholar

43. As a theoretical matter, it is not even clear that there is a direct correspondence between creating cartels and market failure in the marketplace for ideas. Professor Peter Steiner suggested that a monopolist might provide more diverse programming than competitors clustering around the median taste. See Steiner, Program Patterns and Preferences, and the Workability of Competition in Radio Broadcasting, 66 Q.J. Econ. 194 (1952); Daniel D. Polsby, F.C.C. v. National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting and the Judicious Uses of Administrative Discretion, 1978 Sup. Ct. Rev. 1.Google Scholar

44. See Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action 29 (2d ed. 1971) (“there is a systematic tendency for exploitation of the great by the small”); Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy 254-56 (1957); Haddock, David D. & Macey, Jonathan R., Regulation on Demand: A Private Interest Model, with an Application to Insider Trading Regulation, 30 J.L. & Econ. 311, 312 (1987) (“Modern public choice theory suggests that regulatory actions … will divert wealth from relatively diffuse groups toward more coalesced groups whose members have strong individual interests in the regulation's effect” (footnote omitted)).Google Scholar

45. This is not to say that political influence might not readily translate into economic gain for the president and the ruling party.Google Scholar

46. See Polsby, 1978 Sup. Ct. Rev. 1.Google Scholar

47. See United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 143, 152-53 n.4 (1938); Laurence Tribe, American Constitutional Law 1001 (1978).Google Scholar

48. Cf. Ayres, 87 Colum. L. Rev. at 318 n.116 (cited in note 37) (targeting U.S. policies to encourage individual OPEC nations to breach cartel agreement could destabilize other nations' cartel restrictions).Google Scholar

49. See H. Kalven, A Worthy Tradition (1988).Google Scholar

50. This may more aptly be termed “cost-assumption” analysis, where Powe's assumptions suhstitute for the usual analysis of benefits.Google Scholar