It is difficult to reflect on the association between the police and the public in the United States without talking about race and ethnicity; persons of color are disproportionately crime victims and suspects, and their police-related attitudes and experiences with law enforcement often diverge from those of other groups across dimensions of underpolicing and overpolicing (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005; Rios Reference Rios2011; Langton and Durose Reference Langton and Durose2013). Less explicitly, race also influences the discourse and practice of law enforcement tactics (Patterson Reference Patterson1997; Alexander Reference Alexander2010; Fagan et al. Reference Fagan, Braga, Brunson and Pattavina2016; Owusu-Bempah Reference Owusu-Bempah2017).

Yet, the mechanisms by which race and ethnicity shape the association between police encounters and general attitudes about the police remain underdeveloped, particularly in quantitative research. In this article, we extend prior work on social identity, procedural justice, and attitudes toward the police to propose a framework for how race and ethnicity may act as a “prism” through which people view their experiences with law enforcement. Specifically, we argue that, while social and neighborhood markers influence experiences with law enforcement, the subsequent appraisal of these contacts is sensitive to the extent to which individuals identify with their racial/ethnic group. For those whose race/ethnicity is a central part of their identity, the larger historical and social context of the group’s experience with the state may influence their interpretation of specific encounters as well as the configuration of more general opinions about the police (Bell Reference Bell2017). For other individuals, race or ethnicity may be a more tangential part of their social identity, making interactions with law enforcement narrowly framed in terms of individual trade-offs or viewed as less contextualized discrete events and, as such, devoid of a collective “resonance” mechanism.

Similarly, not all types of police contact are equally likely to be viewed through the lens of racial/ethnic identification nor is this framing equally relevant for all judgments that people make about the police. Assessments of police legitimacy may be particularly sensitive given that they convey an opinion not only about the police as a key representative of the state (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003b) but also about their more general role as moral enforcer (Fassin Reference Fassin and Fassin2015) and the type of order that they uphold (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005; Legewie Reference Legewie2016). Conversely, racial and ethnic identification may be less relevant for assessments of police effectiveness, which reflect more narrow, uniform concerns tied to “bottom-line” functions of crime control and prevention (Schuck and Rosenbaum Reference Schuck and Rosenbaum2005, 409) and, therefore, are less likely to vary across group identities (Fielding and Innes Reference Fielding and Innes2006; Taylor, Wyant, and Lockwood Reference Taylor, Wyant and Lockwood2015).

After developing our theoretical framework, we provide a preliminary test of these ideas using surveys collected as part of a multimethod study of young people in New York City (N = 451). We draw on these data to model how experiences with law enforcement relate simultaneously to key components of perceived police legitimacy and effectiveness and to explore how these associations may be conditional on racial/ethnic identification. Our emphasis is on police stops, and we include measures that capture the procedural justice or perceived quality of treatment during the last reported encounter as well as the extent to which police exerted their authority through actions that can be seen as coercive or intrusive (for example, used force, made threats, pulled their weapon) (Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014). We also consider other indicators of contact between police and citizens such as the number of lifetime stops and the variety of citizen-initiated contacts.

This approach echoes new contributions that distinguish between “how” and “whether” police exercise their authority in order to more effectively guide policy, and, thus, this study contributes to efforts to unpack the underlying mechanisms that link people’s lived experience to attitudes toward law enforcement (Worden and McLean Reference Worden and McLean2017; see also Nagin and Telep Reference Nagin and Telep2017; Rengifo, Slocum, and Chillar Reference Rengifo, Slocum and Chillar2019). Our focus on varying forms of interactions with the law also contributes to ongoing discussions regarding the micro-macro links that connect structural racism and “institutional bias” to the lived experiences of people of color (Perez Huber and Solorzano Reference Perez Huber and Solorzano2014; Lara-Millán and Gonzalez Van Cleve Reference Lara-Millán and Gonzalez Van Cleve2017).

A number of studies have explored how identity conditions the effect of experiences with the police on legitimacy and related outcomes, although assessments of the role of racial identity remain rare. Consistent with Henri Tajfel’s (Reference Tajfel1974) social identity theory, research has largely drawn on measures of group membership and sense of belonging, focusing on the extent to which individuals align themselves with the nation-state or specific institutions such as the police (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a; Jackson and Sunshine Reference Jackson and Sunshine2007; Bradford, Murphy, and Jackson Reference Bradford, Murphy and Jackson2014). Other contributions have emphasized more multidimensional approaches to social identity that emphasize heterogeneity in values and “cultural repertoires” and heightened attention to the role of neighborhood context in shaping patterns of legal socialization (Harding Reference Harding2007; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014).

In the context of an oversized and racialized criminal justice system, such as in the United States (Alexander Reference Alexander2010; Rios Reference Rios2011), racial and ethnic group attachments may be more salient than other forms of identification when people frame their interactions with the police (Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006; Solis, Portillos and Brunson Reference Solis, Portillos and Brunson2007; Bradford, Murphy, and Jackson Reference Bradford, Murphy and Jackson2014). We argue that racial and ethnic affiliation, in particular, work as a proxy for common history or experience that helps individuals make sense of police encounters by identifying reference groups and scripts. As Akwasi Owusu-Bempah (Reference Owusu-Bempah2017, 26) notes, “race (and ethnicity) are not ahistorical essences … but rather concepts ‘rooted in a particular culture and a particular period of history’ (Banton Reference Banton1980, 39)”. In this way, racial identity can be studied as a particular form of knowledge that modulates specific attitudes toward legal institutions. This may be critical in urban environments where social identities based on national affiliation are often times superseded by more local forms of identification that are actualized by routine experience and performance and by “public” narratives of the self as well as the behavior of others who may associate specific visual cues (for example, skin color) as proxies for racial or ethnic affiliation (Jackson Reference Jackson2001; Harding Reference Harding2007; Epp, Haider-Markel, and Maynard-Moody Reference Epp, Haider-Markel and Maynard-Moody2014; Owusu-Bempah Reference Owusu-Bempah2017).

Our study focuses primarily on individuals who self-identify as non-Latino/a Black, Latino/a Black, and Latino/a non-Black because, aside from their disproportionate contact with the police, these groups confront a complex legacy of strained relations with state institutions that have undermined their status in society (Kubrin, Zatz, and Martinez Reference Kubrin, Zatz and Martinez2012; Fernández-Kelly Reference Fernández-Kelly2015; Ryo Reference Ryo2016; Bell Reference Bell2017).Footnote 1 The coercive power embodied in law enforcement has been instrumental in defining and defending these stratified spaces (Alexander Reference Alexander2010).

In addition, quantitative studies of legal socialization and police contact have seldom documented experiences of police contact across marginalized groups. Instead, dominant frameworks have simplified the context and consequence of encounters with law and law enforcement by pooling together “non-White” research participants, by limiting analyses to systematic comparisons to the dominant or “super-ordinate” group, or by ascribing identities on the basis of neighborhood or self-defined racial or ethnic membership. Other studies have addressed some of these issues in more detail, highlighting, for example, the importance of specific modes of appraisal, such as respect, across intersections of race and gender or the relative importance of cumulative and vicarious experiences (Solis, Portillos and Brunson Reference Solis, Portillos and Brunson2007; Rengifo and Pater Reference Rengifo and Pater2017). We bridge and expand these approaches to better specify how racial identity may help shape attitudes toward the police among individuals with varying experiences of exclusion and disadvantage. Thus, our study not only bifurcates racial and ethnicity membership (that is, self-identifying as “Black” or “Latina”) from racial/ethnic identity, which explicitly affirms affiliation (that is, signaling that race/ethnicity is a key part of self-image), but it does so across multiple dimensions of stratification—for example, foreign-born/US-born individuals—and across lived experiences of police contacts—for example, lifetime/most recent encounters.

We contend that ratings of police legitimacy represent individual’s views of the police as well as broader judgments on the social contract that law enforcement reflects as principal “moral agents” (Fassin Reference Fassin and Fassin2015; see also Patterson Reference Patterson1997). Racial and ethnic identity serves as a micro-macro link that connects these assessments to personal encounters with the police, particularly when these experiences are seen as reflective of a recurring pattern of treatment (Epp, Haider-Markel, and Maynard-Moody Reference Epp, Haider-Markel and Maynard-Moody2014). We hypothesize that for Blacks and Latino/as, the extent to which stops and arrests trigger these collective experiences is shaped by racial/ethnic identification. In contrast, we argue that individual ratings of police effectiveness are more narrowly bounded by law enforcement actions and expectations, and, as a result, these ratings are less likely to evoke broader or more collective appraisal frames. Beyond the specification of these relationships, our research contributes to ongoing efforts to reconsider trust in the police and police legitimacy in the context of a broader conversation about race and ethnicity, law, and the quality of citizenship and democracy.

LEGITIMACY, EFFECTIVENESS, AND THE POLICE

Classic approaches to legitimacy have linked it to a particular form of authority rooted in process and consent (Weber [Reference Weber1922] 1978). More recent scholarship has expanded this perspective to better account for patterns of grounded experience with law and law enforcement. As Robert Worden and Sarah McLean (Reference Worden and McLean2017, 44) note, however, “it would be an exaggeration to say that a consensus has emerged on the definition of legitimacy.” In one of the earliest reconceptualizations, Tom Tyler ([Reference Tyler1990] 2006) specified legitimacy as the acceptance of authority marked by the obligation to obey the law and the support for legal authorities. Yet other contributions note that obligation to obey may be grounded in motives, such as fear, that have little to do with shared norms or other key underlying components of the model (Bottoms and Tankebe Reference Bottoms and Tankebe2012; Tankebe Reference Tankebe2013). These approaches highlight instead the notion of legitimacy as the recognition “as normatively valid the police’s claim to exercise power” based on law and shared community values (Tankebe Reference Tankebe2013, 105) or as the “judgments that ordinary citizens make about the rightfulness of police conduct” (National Research Council Reference Skogan and Frydl2004, 291). Taken together, these normative, value-based perspectives are thus more proximate to studies that consider legitimacy in terms of broad assessments of the “right (moral or legal) to make decisions” (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2018, 7) and more distal from narrower domains associated with compliance or institutional support (Tyler [Reference Tyler1990] 2006).

We posit that institutions such as the courts or the police are more likely to be assessed based on normative grounds given their explicit roles in order maintenance and social regulation (versus hospitals, schools, and mail service). In particular, as law “enforcers,” the police not only exert a monopoly over the legal use of force and the street-level adjudication of order and disorder, but they also play a key role in local “moral economies” determined by the production and circulation of “values and affects” (Fassin Reference Fassin and Fassin2015, x). Citizen ratings of the legitimacy of the police are also more likely to “signal” a rather stable attribution about forms and mechanisms of authority (Innes Reference Innes2014; see also Bottoms and Tankebe Reference Bottoms and Tankebe2012) sensitive to shared histories of oppression and domination (Solis, Portillos, and Brunson Reference Solis, Portillos and Brunson2007; Bell Reference Bell2017). According to Richard Chackerian (Reference Chackerian1974, 142), “the feeling that government is remote and that officials are corrupt may be more important for one’s evaluation of the police than the crime rate, arrest rate, or police observance of due process.” This makes perceptions of police legitimacy inherently collective, moral, and enduring.

In contrast, judgments about police “effectiveness” tend to be driven by more concrete, instrumental, function-specific concerns about the specific contribution of law enforcement to preventing and controlling crime (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a; Holn, Bradford and Stanko Reference Holn, Bradford and Stanko2010; Miller and D’Souza Reference Miller and D’Souza2016). Similar ratings about the “responsivity” of the state consider policing as a government service that contributes to the formation of citizen opinions about authority and representation (Tankebe Reference Tankebe2013). If the police are viewed as ineffective, people may come to perceive that the costs associated with cooperating outweigh the benefits, and, as such, they may refrain from mobilizing law or may be more prone to break it (Skogan Reference Skogan1990; Huo et al. Reference Huo, Smith, Tyler and Lind1996; Tankebe Reference Tankebe2013). This makes ratings of police effectiveness inherently individual, instrumental, and shifting. Although the precise nature of the relationship between legitimacy and effectiveness has been the subject of debate, they are generally viewed as interdependent and mutually reinforcing as both are anchored to lived experience (Bottoms and Tankebe Reference Bottoms and Tankebe2012).

THE ROLE OF PERSONAL EXPERIENCES IN SHAPING VIEWS OF THE POLICE

Process-based models of regulation assert that people’s personal contact with law enforcement shapes perceptions of police legitimacy because these encounters provide an opportunity to confirm expectations regarding police action and also serve as a point of validation of their own identity (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003b). In this set of approaches, it is procedural justice, or the fairness and justness of procedures and decision-making, that plays the biggest role in determining whether people view the police as legitimate because this reaffirms principles of inclusion and representation (Tyler and Lind Reference Tyler and Lind1992). People are more likely to view interactions with authority as procedurally just when they perceive they have been given a voice in the process, have been treated with dignity and respect, trust the motives of authorities, and believe that decisions were based on facts (Tyler [Reference Tyler1990] 2006). Further, there is some evidence that links how people perceive they have been treated by the police during specific encounters to legitimacy. For example, Tom Tyler and Jeffrey Fagan (Reference Tyler and Fagan2008) find that individuals who rate specific police stops as more procedurally fair subsequently report higher levels of police legitimacy even when the outcome of the stop was unfavorable to them. Other types of police encounters, including experiences shared by others, also have shown rather consistent associations with perceptions of legitimacy (Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello, Hawkins and Ring2005; Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014; Fagan et al. Reference Fagan, Braga, Brunson and Pattavina2016; Rengifo and Pater Reference Rengifo and Pater2017; for reviews, see also Mazerolle et al. Reference Mazerolle, Bennett, Davis, Sargeant and Manning2013; Donner et al. Reference Donner, Maskaly, Fridell and Jennings2015).

Research has yielded more equivocal findings on the role of citizen-police encounters in shaping perceptions of police effectiveness. One study of citizens residing in New York City found that individuals who rate their police stops more negatively tend to view the police as less effective (Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2007). Similar results have been reported in connection to experiences of police harassment (Wu, Sun, and Triplett Reference Wu, Sun and Triplett2009) and racial profiling (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2002). However, in other cross-sectional studies the association of police mistreatment to ratings of effectiveness is conditioned by race (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005) or neighborhood context (Wu, Sun, and Triplett Reference Wu, Sun and Triplett2009), or it is sensitive to modeling choices (Taylor, Wyant, and Lockwood Reference Taylor, Wyant and Lockwood2015). Findings from studies using longitudinal data have also shown mixed results. For example, a study by Dennis Rosenbaum and colleagues (Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello, Hawkins and Ring2005) indicates that negative evaluations of citizen-initiated contacts harm ratings of police performance, but a concomitant negative effect is not observed for police-initiated encounters in which people perceive they have been treated poorly. Further, these effects emerged for Whites, but not for Blacks or Latino/as. The authors suggest this variability might be due to the fact that people of color have strong preexisting negative opinions of police, making the effect of any one discrete encounter less relevant, or that they might have come to expect negative interactions with law enforcement (see also Miller and D’Souza Reference Miller and D’Souza2016).

Not all measures of the quality of treatment may reflect similar appraisals. For example, in some studies, ratings of officers’ politeness, respect, or friendliness are generally higher than markers of “satisfaction” or other perceptual measures of procedural justice associated with “voice,” “neutrality,” or “affect” (Skogan Reference Skogan2006; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014). Importantly, several studies have found that perceptual measures are not tightly coupled to behavioral markers of specific protocols such as officers identifying themselves to residents (Skogan Reference Skogan2005; Fratello, Rengifo, and Trone Reference Fratello, Rengifo and Trone2013; Worden and McLean Reference Worden and McLean2017; Nagin and Telep Reference Nagin and Telep2017).

There is emerging evidence that for shaping view of the police, the extent to which police exert their authority may be more important than how they exert it (Worden and McLean Reference Worden and McLean2017). Stops that involve personal searches or force have been specifically labeled by some studies as “intrusive” or “opaque” and have shown independent associations with lower ratings of police legitimacy and effectiveness (Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014; Miller and D’Souza Reference Miller and D’Souza2016; see also Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski, and Moyal Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski and Moyal2015) and heightened public scrutiny (Rengifo and Fowler Reference Rengifo and Fowler2016). Measures that capture police behaviors provide a less subjective framing for the recounting of specific incidents, as these measures typically focus on narrowly defined items (for example, “officers displayed a weapon,” “officers searched or frisked”) without overarching frames of “respect” or “fairness.” In contrast, measures that capture citizens’ evaluations of police behaviors embed more subjective, group-based meanings to these exchanges (Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006; Goffman Reference Goffman2014). For these reasons, it is important to assess how evaluations of police behavior as well as their actions relate to ratings of legitimacy and effectiveness, something missing from most research.

We suggest that general attitudes toward the police may not be exclusively driven by personal or vicarious discrete encounters or associated perceptions but, rather, prompted by a cognitive process that connects individual experience to more collective, general sentiments that moderate their direction and significance. In her discussion of legal estrangement, Monica Bell (Reference Bell2017) describes a cultural collective consciousness and “memory” among Blacks built on marginalization and the accumulation of personal and shared unjust criminal justice system interactions. Other approaches explore similar notions tied to varying forms of linked fate and a sense of belonging (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2018). We expand these arguments to suggest that racial/ethnic identity provides a link between this macrolevel form of group consciousness and individual-level evaluations of personal and vicarious police encounters. In the following section, we unpack this process further and relate it to prior research and theory.

RACIAL IDENTITY AND POLICE ENCOUNTERS

Social identities are built on subsets of stable and dynamic characteristics that link individuals to referent groups on the basis of demographic factors, religion, or national origin (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1974). While these affiliations are partially shaped by person-level cognitive strategies, they also develop through social interaction, serving as intertwined “sense-making” devices that help shape attitudes and chart behaviors (Stets and Burke Reference Stets and Burke2000). Consistent with Tajfel’s “social identity” theory, normative theories of compliance have focused on one specific type of identity—namely, identification with the mainstream, “superordinate,” or “in group” (that is, the group that the police represent)—as a key correlate of legitimacy (Bradford, Murphy, and Jackson Reference Bradford, Murphy and Jackson2014; Tyler and Lind Reference Tyler and Lind1992). Several studies have found that perceptions of procedural fairness of the police are “identity relevant” (Radburn et al. Reference Radburn, Stott, Bradford and Robinson2018), showing, for example, that individuals with a closer affiliation with specific superordinate categories, such as the nation-state or citizenship, rate the police as more procedurally just and tend to weigh these forms of authority more heavily (Bradford Reference Bradford2014). We argue that a more complete understanding of this phenomenon in the United States requires consideration of other dimensions of self-representation that are more likely to be actualized through police contact and neighborhood context; racial/ethnic identity may be particularly salient.

Racial/ethnic identity is defined by the extent to which these attributes are central to an individual’s sense of self, their affiliation with similar others, and their general appraisals of these affiliations (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton and Smith1997). Similar to other aspects of identity, racial/ethnic identity may be mobilized to recognize specific situations or behaviors or to interpret exchanges “across situations” (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton and Smith1997). In addition, racial or ethnic affiliation also highlights individual and group-level struggles for equality and justice and dispels the notion that people of color hold “monolithic” views of the police (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005, 1025; see also Sellers and Shelton Reference Sellers and Shelton2003) and of their own group identity (Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2018). However, unlike other social identities, it conveys a more pronounced role of the state as an adjudicator of these struggles and as a key agent in the legitimation or condemnation of specific groups (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton and Smith1997; Alexander Reference Alexander2010; Ward Reference Ward2015).

In the United States, exchanges with law enforcement are particularly salient in the configuration of these identities, as the primary roles of the police revolve around identifying “deviants,” enforcing majority rules and serving as “prototypical group representatives of a group’s moral values” (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003b, 153; see also Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006). As such, specific encounters are pivotal to actualizing a variety of identities (sexual/racial/ethnic) because they communicate a perceived status through discrete routines and practices—checking IDs, administering sanctions, providing help—a process that is akin to the development of a “critical self-awareness,” which is described by Anthony Bottoms and Justice Tankebe (Reference Bottoms and Tankebe2012, 163). Simultaneously, these identities may recast the interpretation of police encounters, serving as a “prism” that refracts their meaning in accordance with shared experiences and narratives, projecting it into broader domains of judgment—courts, schools, hospitals (Rios Reference Rios2011; Lara-Millán and Gonzalez Van Cleve Reference Lara-Millán and Gonzalez Van Cleve2017)—or forms of discrimination (Sellers and Shelton Reference Sellers and Shelton2003).

Much of the work that relates interactions with the police to identity has focused on how these interactions shape social identity (Bradford Reference Bradford2014; Slocum, Wiley, and Esbensen Reference Slocum, Wiley and Esbensen2016). This work has also explored how police encounters influence the development of racial identity (Epp, Haider-Markel, and Maynard-Moody Reference Epp, Haider-Markel and Maynard-Moody2014), with some research identifying police stops as a “race-making factor” (Fagan and Davis Reference Fagan and Davis2000, 483) or the criminal justice system as an “engine of identity production and influence” (Bradford, Murphy, and Jackson Reference Bradford, Murphy and Jackson2014, 527). Less theoretical and empirical attention has been directed at understanding how identity—particularly racial and ethnic identity—may acts as a lens through which people project interactions with police into broader assessments of legitimacy or effectiveness. Work that has examined this issue has relied on explicit markers of conventional group identity that capture the status and views of the dominant group (“social,” “national” identities). Other studies have inferred identity with marginalized groups from demographic characteristics (minorities, immigrants, youth), distance from a “conventional” standard, including serious criminal involvement (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2002; Lee, Steinberg, and Piquero Reference Lee, Steinberg and Piquero2010; Goffman Reference Goffman2014; Slocum Reference Slocum2018), or markers of racial membership (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a). Inferring identity from markers is problematic because people are embedded in multiple subgroups, and they may align themselves more strongly with some and not at all with others (Oliveira and Murphy Reference Oliveira and Murphy2015).

The studies that do bridge the police contact/attitudes literature with explicit forms of identity suggest that these matter. Yuen Huo and colleagues (Reference Huo, Smith, Tyler and Lind1996), for example, find that compliance with figures of authority is challenged when individuals have a strong subgroup identification as well as weak superordinate group identification. In another study, Alessandro Oliveira and Kristina Murphy (Reference Oliveira and Murphy2015) show that minority survey respondents that identified more with a subordinate ethnic group were less likely to rate police services as fair, although more general forms of identity mattered for other sorts of attitudes toward the police. In a study based in the United Kingdom, Jonathan Jackson and Jason Sunshine (Reference Jackson and Sunshine2007) found that respondents were more likely to rate the police as effective in reducing crime and engaging the community when they identified more strongly with the values of the local officers.

Fewer studies have examined whether identity shapes the impact of personal encounters with the police on perceptions of legitimacy and effectiveness. The research on racial or ethnic identity is even more limited, particularly across varying forms of identities and types of police contact. One exception is a study by Joanna Lee, Laurence Steinberg, and Alex Piquero (Reference Lee, Steinberg and Piquero2010) that is based on panel survey data collected from Black adjudicated youth. They found that individuals with a stronger sense of racial identity perceive greater police discrimination, but, counter to prior studies, they also tend to perceive the police as more legitimate. The authors posit that identity is a “proxy for cognitive and psychosocial maturity” that balances awareness of racial discrimination with an “understanding that the police [are] a necessary and legitimate institution” (787). Importantly, they find that racial identity does not moderate the relationship between perceived police discrimination and police legitimacy. Another, more recent contribution is James Gibson and Michael Nelson’s (Reference Gibson and Nelson2018) study of attitudes of Blacks toward the legal system, showing that the effect of vicarious negative police contacts on perceptions of legal fairness is amplified by higher levels of racial identification.

We hypothesize that for Blacks and Latino/as, a stronger sense of racial identification is negatively correlated with legitimacy as observed in some prior work. Directly, Blacks and Latino/as with a more salient racial identity are expected to view the police in less positive light because they see them as a foreign institution, fear their abuse and stigma, and consider their work to be an extension of past forms of racialized social control. Indirectly, racial/ethnic identification is hypothesized to amplify the negative effects of police encounters seen as disrespectful, unsatisfactory, or anchored on coercive actions because these events are viewed through racial frames (Lee, Steinberg, and Piquero Reference Lee, Steinberg and Piquero2010; Epp, Haider-Markel, and Maynard-Moody Reference Epp, Haider-Markel and Maynard-Moody2014) akin to other forms of discrimination (Sellers and Shelton Reference Sellers and Shelton2003; Rengifo and Pater Reference Rengifo and Pater2017). When Black and Latino/a youth identify more closely with their racial or ethnic group, they may see more intrusive police protocols as part of a larger historical and cultural context in which people of color are mistreated or neglected by not only the police but also by other representatives of the dominant social group (see, for example, the “prejudice hypothesis” provided by Dennis Rosenbaum and colleagues [Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello, Hawkins and Ring2005]). This cognitive process is not limited to the framing of specific incidents as “signal events” reflective of a racialized order; rather, it involves the projection and extrapolation of these judgments to adjacent domains in the form of behavioral policies—for example, when to call the police and when to avoid them—and more general scripts that highlight enduring attributes and higher-order rationales such as legitimacy and neutrality. Consistent with this approach, we do not expect that racial identification will influence views on police effectiveness directly or indirectly, as this specific domain of valuation arguably is defined by more uniform functional assessments and perceptions of treatment.

In sum, much of the existing research tells only part of the story. It looks at only the direct effect of racial identity on views of the police, includes a limited set of interactions for a limited period of time, and misses an important segment of the population that is particularly likely to encounter the police: young people of color. Most importantly, it does not embed individual experiences with the police in the larger historical and cultural context of marginalization and racial conflict. Our study seeks to address this gap by exploring the nuanced ways in which race acts as a prism through which people make sense of their experiences with the police.

THE CURRENT STUDY

Using a sample of Black and Latino/a youth, we explore how racial and ethnic identification moderates the relationship between police encounters and ratings of police legitimacy and effectiveness. Specifically, we examine whether or not the association between legitimacy and effectiveness and type of police contact or appraisal is contingent upon levels of racial or ethnic identification—that is, whether identity only “activates” the projection of certain encounters and not others in the formation of general attitudes toward the police and whether effects vary for effectiveness and legitimacy given that they signal different dimensions of police performance. While the constructs of legitimacy and effectiveness that we employ in our study do not fully capture more extensive operationalizations of similar concepts, they reflect core normative and instrumental elements and map key elements of our theoretical model. Unlike other components of legitimacy such as the obligation to obey or trust, our approach emphasizes value judgments of police behaviors, and, as such, it can better describe the type of “broad” assessments that individuals may mobilize when interpreting particular displays of state authority. In contrast and consistent with our proposed framework, the construct of effectiveness is defined in terms of specific measures of crime prevention and crime control.

As shown in Figure 1, we hypothesize that racial identification will amplify the links between experiences with the police and ratings of legitimacy, but not effectiveness, due to stated differences in their underlying framing and scope. In addition, we hypothesize that racial identity will be particularly salient for measures that encompass an enduring pattern of encounters (for example, lifetime stops as opposed to specific incidents) that “harden” other dispositions (Rosenbaum et al. Reference Rosenbaum, Schuck, Costello, Hawkins and Ring2005, 360; see also Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006). Racial identity also is expected to moderate the relationship between subjective valuations that may already embed a racialized interpretation—such as perceptions of “respectful” or “satisfactory” treatment—a pattern that may be less pronounced for more narrow, behavioral indicators of police coercive authority such as in connection to specific police actions.

Figure 1. Theoretical model

Data and Methods

Our study is based on survey data collected as part of a broader research project of youth and police practices conducted by the Vera Institute of Justice in New York City, which also included interviews with residents in neighborhoods marked by high rates of crime and police activity. The survey component engaged local persons between eighteen and twenty-five years of age reporting at least one police stop in their lifetime. The selection of this particular target group was meant to document the experience of people most likely to be engaged by the police (Langton and Durose Reference Langton and Durose2013). Importantly, age also conditions other mechanisms of attitude formation including legal socialization and racial identity (Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014). Fieldworkers in high-traffic areas approached potential respondents over the course of two to three consecutive days until a predefined number of respondents was reached. Upon screening for age, residency, and police stops, eligible persons who agreed to participate in the study were directed to complete a thirty-five-minute survey in a nearby community organization. Approximately 40 percent of eligible individuals completed the instrument (N = 508) and received a $25 gift card. About 89 percent of this sample self-identified as either non-Latino/a Black (n = 281) or Latino/a (n = 170). For the main analyses, we limit our sample to this subset of respondents.Footnote 2

Survey questions sought to elicit general perceptions of the neighborhood and law enforcement as well as more in-depth information regarding process, outcome, and perceptions attached to voluntary and involuntary encounters with the police and to other justice system contacts. In addition, respondents were asked about various markers of self-identity, criminal victimization, and recent discriminatory experiences. We draw on these data to specify the latent and observed variables of the structural equation models specified below (see Table 1 for summary statistics for all variables, including factor loadings and alpha scores).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample (N = 451)

Dependent Variables

We specify two latent variables that measure attitudes toward the police along the domains of legitimacy and effectiveness (Figure 1). These latent variables are derived from a set of four-point Likert-type items capturing degree of agreement/disagreement with general statements describing local law enforcement. The legitimacy scale reflects perceived local judgments about the specific form of authority exerted by the police. Two of the scale-items are reverse-coded (“the police have too much power around here,” and “the police around here bother kids for no reason”), and one is not (“the police are honest”) (alpha = 0.644).Footnote 3

The effectiveness scale rates the perceived ability of the police to meet service expectations of the public (“the police are good at catching the people who commit crimes in my neighborhood,” “the police are good at preventing crimes in my neighborhood,” “the police in this neighborhood respond quickly to calls”) (alpha = 0.743). Survey items loaded separately into each scale using principal components factor analysis (explained variance = 67 percent). As noted in Table 1, the average rating for effectiveness is slightly higher than the mean value reported for legitimacy. The correlation between these scales is positive (Pearson r = 0.420, p < 0.001).

While some work considers the role of police performance evaluations in shaping views of legitimacy or views effectiveness as a component of legitimacy (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a; Tankebe Reference Tankebe2013; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014), we treat effectiveness as correlated with, but not causally related to or a component of, legitimacy for several reasons. First, in the process-based model, instrumental concerns (for example, effectiveness of the police) are not considered central to explaining legitimacy, and studies show inconsistent relationships between the two (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a). Second, instrumental concerns are often contrasted with normative explanations for understanding compliance (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a; Tyler [1990] Reference Tyler2006), making it important to understand the factors that differentially influence these two distinct perceptual measures of the police. Third, in conceptualizations in which effectiveness is a component of legitimacy, the distinction is still made between a “morally authoritative source for government, and an ability to satisfy the ends which justify its enormous concentration of power” (Beetham Reference Beetham1991, 137, cited in Tankebe Reference Tankebe2013, 126). Fourth, this specification fits with the exploratory nature of our analysis and allows for a clearer examination of how racial identity moderates the relationship between experiences with the police and perceptions of law enforcement.

Independent Variables

Cumulative and Indirect Experiences with the Police

Based on prior research on the saliency of cumulative experiences for attitude formation (for example, Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006), we capture each respondent’s lifetime number of police stops and, separately, a variety score capturing up to eight different ways they may have voluntarily engaged with the police (for example, through reporting of their own victimization or the victimization of others; in connection to a traffic accident or medical emergency; information requests; participation in local meetings). We also measure whether the respondent has ever been arrested using a dichotomous measure. We include two additional, but less direct, dichotomous measures of interactions with the police. One captures lifetime criminal victimization and another reflects whether respondents knew any incarcerated persons as a way to capture a serious form of vicarious justice contact.

As indicated in Table 1, which presents descriptive statistics for all measures and scale items, police stops are frequent among the respondents (M = 7.936, SD = 6.785). Incidents of citizen-initiated contact are not only diverse but also rather prevalent (53 percent report one or more lifetime events). There is also a high prevalence of arrest and victimization (35 percent and 67 percent, respectively).

Discrete Police Encounters

We explored whether discrete police encounters exert an influence on perceptions of law enforcement given their specific nature and recency. For their most recent police stop,Footnote 4 respondents were asked to report using a four-point Likert scale how strongly they agreed with the following statements regarding specific perceptions of procedural justice linked to the quality of their treatment: (1) “the police treated me with respect and dignity” and (2) “I am satisfied with the way police officers handled the situation.” Responses were used to create two dichotomous variables that capture whether respondents perceived they were treated with disrespect and whether they were dissatisfied with how the officers handled the encounter (1 = disagreed or strongly disagreed with these statements, 0 = agreed or strongly agreed). Table 1 shows that 82 percent of respondents felt disrespected during the last stop, and the same percentage were dissatisfied.

To supplement these perceptual measures of procedural justice, we created two measures that captured police actions tied to the same (last) stop incident. First, we included a scale of coercive police actions created by adding up specific behaviors: frisking/searching pockets; using force; displaying a weapon; and making threats (M = 1.916, SD = 1.379). Second, the outcome of the stop was measured using a dichotomous indicator of whether the contact resulted in an arrest or summons, which occurred in 28 percent of the events.

Racial/Ethnic Membership

Respondents were asked to self-report their ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino/a, West Indian/Caribbean, White/Caucasian, or other) and their race (White, Black, Asian, American Indian, or other). In addition, persons were asked about their country of birth, their parents’ country of birth, and the primary language spoken at home. We use this information to divide our sample into three groups: (1) non-Latino/a Black (n = 281); (2) Latino/a Black (including West Indian/Caribbean) (n = 58); and Latino/a White (n = 112). In the analyses, non-Latino/a Black is the reference category.

Racial/Ethnic Identification

Consistent with prior studies, we capture racial identity with a latent variable based on an integrated version of the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney Reference Phinney1992) and the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (Sellers et al. Reference Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton and Smith1997). These scales are designed to measure an individual’s affiliation with their racial or ethnic group across different subscales such as ethnic “identity achievement” or “ethnic behaviors,” with most studies showing no significant measurement variance across racial/ethnic groups. In criminology, varying components of these scales have been used as moderators of the effect of procedural justice on offending (McLean Reference McLean2017) and attitudes toward the police (Lee, Steinberg, and Piquero Reference Lee, Steinberg and Piquero2010). While these and other studies have tended to apply this scale to a single group on the basis of racial membership (that is, African American adolescent) or serious criminal justice contact (that is, incarcerated youth), our study focuses on a broader set of respondents with more diverse ethnic/racial backgrounds and experiences with law and law enforcement. Our measure of racial identification includes three items that reflect the construct of racial/ethnic “affirmation and belonging” in terms of Likert-type questions eliciting levels of agreement/disagreement with the following statements: “I feel good about the racial/ethnic groups I belong to,” “my race and ethnicity are an important reflection of who I am,” and “my race and ethnicity are an important part of my self-image” (alpha = 0.840). Scores were generally high (M = 3.285, SD = 0.628), and there were no significant differences in scale scores across the three racial/ethnic groups in the study sample.

Other Variables

We included a dichotomous measure of whether participants experienced discrimination in the past year because of their race, ethnicity, color, language, or country (0 = no, 1 = yes); discrimination was a relatively common experience for study participants (63 percent). This measure provides a point of comparison for our measures of police encounters. In addition, we controlled for immigrant status (0 = native born, 1 = foreign born) and gender (0 = male, 1 = female). Given the absence of income-related questions in the survey and the fact that participants were eighteen to twenty-five years old, we use a dichotomous indicator of educational attainment as a measure of socio-economic status (0 = without high school diploma, 1 = completed high school or higher).

Analytical Strategy

We use structural equation modeling to estimate direct and indirect associations between attitudes toward the police, police encounters, and racial identity. We rely on full information maximum likelihood estimation to maximize the use of cases with incomplete information. Our latent variables were constructed using factor analysis and relevant theory. We allowed all observed variables to correlate with each other, and we also correlated the errors of our two outcome variables.

Our analyses proceeded as follows. First, we estimated a base model including racial identification along with demographic control variables, discrimination, and vicarious justice contact (knowledge of incarcerated persons). These results provide baseline results against which to assess the contribution of more specific cumulative and discrete encounters with police to perceptions of legitimacy and effectiveness, which were added in Model 2. Next, one at a time, we introduced a series of multiplicative interaction terms created by multiplying our measure of racial identification with each of our variables capturing police contact. Interaction terms identified as significant were included in Model 3 and Model 4 along with all of the main effects. We report both unstandardized (b) and standardized (B) coefficients in the tables, although, in the text and graphs, we only reference unstandardized estimates due to the difficulty interpreting fully standardized coefficients for binary variables in structural equation modeling. Models were estimated on the full sample; there were no substantive differences when they were estimated separately by racial/ethnic group.

RESULTS

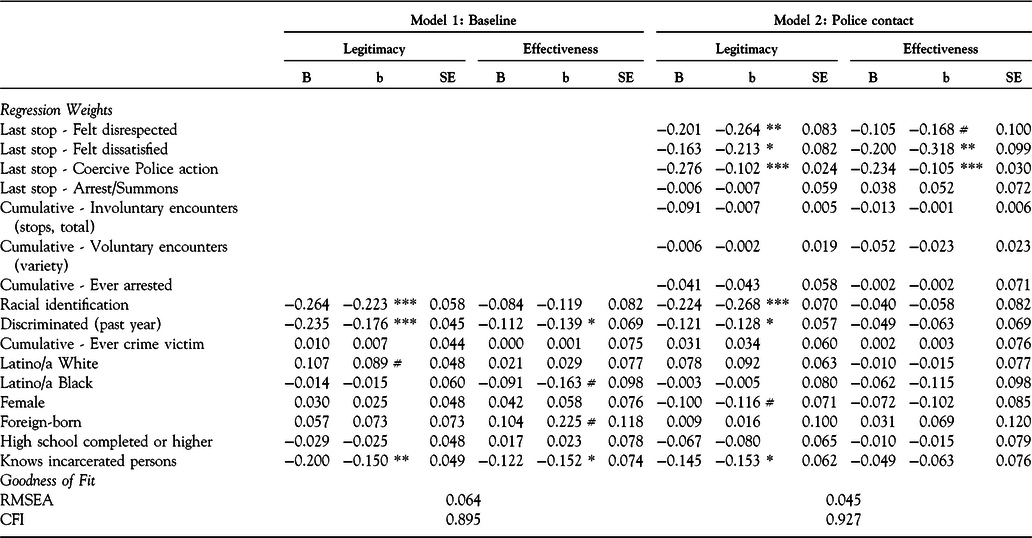

Baseline estimates shown in Model 1 of Table 2 indicate that respondents with a stronger sense of racial/ethnic identity tend to see the police as less legitimate (b = –0.223, SE = 0.058), but this measure does not show a statistically significant relationship with perceptions of effectiveness. More marginally, relative to non-Latino/a Blacks, Latino/a Whites perceive the police as more legitimate (b = 0.089, SE = 0.048), and Latino/a Blacks and native-born respondents give the police lower ratings of effectiveness (b = –0.163, SE = 0.098; b = 0.225, SE = 0.118). The experience of discrimination and knowledge of incarcerated persons shows a more uniform, negative association with both legitimacy and effectiveness. These preliminary results lend support to the decision to model effectiveness separately from legitimacy as racial/ethnic group membership and racial identification exhibit independent and sometimes contrasting associations with these two outcomes.

Table 2. Main effects for structural models predicting perceived legitimacy and effectiveness of the police

Note: B = Standardized coefficientl b = Unstandardized coefficient, SE = Standard Error *** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 #p<.10 (two-tailed tests).

Measures of police contact and victimization were added in Model 2. Results show that cumulative experiences in terms of stops, voluntary contacts, and arrests are not related to variation in measures of legitimacy or effectiveness. Instead, the scale of coercive police actions during the last reported stop is negatively related to legitimacy and effectiveness (b = –0.102, SE = 0.024; b = –0.105, SE = 0.030, respectively).Footnote 5 In addition, we find a significant inverse relationship between the appraisal of recent stops as disrespectful and legitimacy (b = –0.264, SE = 0.083) and a similar, albeit marginally significant, association between perceived disrespect and effectiveness (b = –0.168, SE = 0.100). There is a more consistent negative association between dissatisfaction with how the officer handled the stop and both legitimacy and effectiveness (b = –0.213, SE = 0.082; b = –0.318, SE = 0.099, respectively). Baseline associations between perceptions of the police and racial identity were relatively unchanged after the inclusion of the encounter-based variables. However, in Model 2, the effects of discrimination, vicarious justice system contact, and racial/ethnic membership became weaker, or nonsignificant, particularly in connection to effectiveness.

These findings suggest that measures of procedural justice may relate differently to police attitudes: respect-based judgments have a greater influence on legitimacy relative to effectiveness, while the opposite pattern is observed for satisfaction. The measure of coercive police action, which is not based on perceptions, is more evenly related to both legitimacy and effectiveness. These preliminary findings are consistent with results from prior studies that find that police contacts, including arrests and voluntary encounters, are inconsistent predictors of citizens’ evaluations of the police when devoid of further qualification (Tyler and Fagan Reference Tyler and Fagan2008).

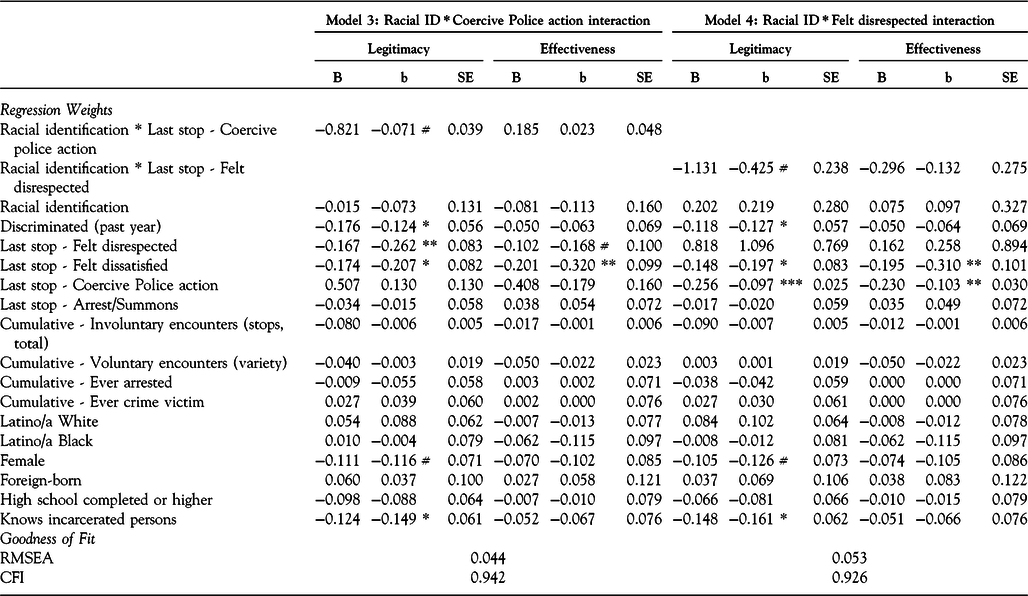

Next, we explored the role of racial identity as a potential moderator of police encounters and perceptions. We replicated Model 2 entering interactions between our measure of racial identity and measures of police contact one at a time. The results for the significant interactions are displayed in Table 3. Consistent with the main-effects models presented above, we did not find evidence linking legitimacy or effectiveness to cumulative stops, voluntary contacts, lifetime arrests, or sanctions tied to the last stop. More consistent with our expectations, however, we did find that racial/ethnic identification moderates the effects on legitimacy of action-oriented ratings of police behavior (Model 3) and perceived disrespectful treatment (Model 4). Specifically, results show that having a stronger racial identification marginally amplifies the association between more coercive police actions during the last stop and perceptions of legitimacy (b = –0.071, SE = 0.039), with a similar effect for the more narrow and subjective measure of perceived disrespect, which is also linked to the last stop (b = –0.425, SE = 0.238). When combined into a single model (results not shown), both interactions remain associated with legitimacy at p < 0.10 (b = –0.397, SE = 0.233; b = –0.077, SE = 0.043, respectively).

Table 3. Interactions of police contact and racial identification in structural models predicting perceived legitimacy and effectiveness of the police

Note: B = Standardized coefficient b = Unstandardized coefficient, SE = Standard Error *** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 #p < .10 (two-tailed tests).

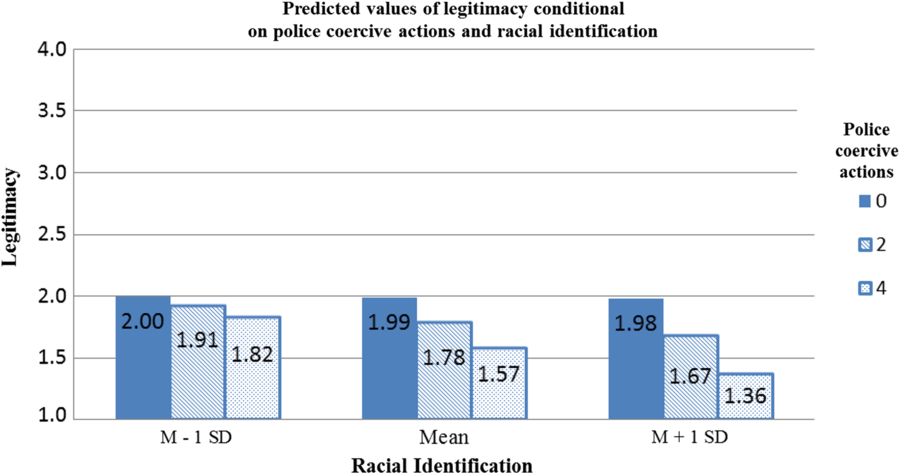

To illustrate the nature of these interaction effects, we first plotted predicted values of legitimacy at varying values of the racial/ethnic identification and coercive police action scales (Figure 2). Predicted values of legitimacy were computed at one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, and at one standard deviation above the mean of the racial/ethnic identification scale and at zero, two, and four coercive police actions.Footnote 6Figure 2 indicates that, at low levels of racial/ethnic identification, coercive actions by the police during the last reported stop have little substantive effect on legitimacy. For example, on a scale of one to four, with higher values meaning more positive attitudes, the predicted value of legitimacy is 2.00 for people who did not experience coercive police actions and decreases slightly to 1.82 for people who experience all four forms of coercive behavior. For people who more strongly identify with their racial/ethnic group (that is, have scores one standard deviation above the mean), the relationship between coercive actions and legitimacy remains negative but is stronger; those who reported experiencing none of these actions during their most recent police stop have predicted legitimacy values of 1.98, while those who scored a four on this index have predicted scores of 1.36. The figure also provides some evidence that the salience of racial/ethnic identification for evaluations of police legitimacy is activated by coercive treatment by the police.

Figure 2. Results from Model 3: Moderating Effect of Racial Identity on the Relationship between Police Coercive Actions and Legitimacy

Figure 3 provides predicted values of legitimacy for people who reported they were treated disrespectfully during their most recent stop and for those who did not at various values of racial/ethnic identification. At low levels of identification, the predicted value of legitimacy for respondents was remarkably similar across feelings of respect/disrespect (1.95 versus 1.88). However, for individuals with high levels of racial identification (that is, having scores one standard deviation above the mean), this gap was more pronounced (2.03 versus 1.59). While the observed interaction effects are relatively small, it is important to keep in mind the relatively limited amount of variability in the legitimacy outcome (M = 1.780, SD = 0.619).

Figure 3. Results from Model 4: Moderating Effect of Racial Identity on the Relationship between Disrespectful Treatement and Legitimacy

It is also important to note that the specification of interaction effects does not alter the overall goodness of fit statistics of the main effects models shown in Table 2, with parameters remaining within conventional thresholds employed to define appropriate fit (Model 3: root mean square of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.044, comparative fix index [CFI] = 0.942; Model 4: RMSEA = 0.053, CFI = 0.926). Other results (not shown) for Models 3 and 4 confirm that measures of police contact and other variables tend to account for evaluations of police legitimacy better than effectiveness (R 2 for legitimacy = 0.511 versus R 2 for effectiveness = 0.214) and that these two constructs are positively related to one another (coefficient of variation = 0.125).Footnote 7

In a set of supplementary analyses, we expanded our examination of racial identity to include the group of survey respondents who self-identified as “White” (non-Latino/a) or “Other.” Results from a series of one-way analyses of variance tests confirm that our measure of racial identity did not vary significantly across the expanded set of racial/ethnic groups in the survey (F = 6.01, non-significant). However, and consistent with our expectations, we did find differences across groups with regard to the measure of perceived police legitimacy (F = 2.58, p < 0.05). More specifically, Whites reported the highest ratings of police legitimacy among survey respondents relative to all other groups. On par with our propositions, there were no significant differences by racial membership for the measure of police effectiveness or in lifetime measures of variety of citizen-initiated encounters or police stops.

Thus, while the size and nature of the survey sample limits the observed variation in some of the key measures of the study, our analyses lend some support to the idea that opinions about the police, particularly police legitimacy, may not be explained by isolated measures of racial membership or police contact but, rather, by a more fluid framework that relates racial identity to specific forms of lived experience of law and law enforcement. In particular, our results point to racial identity as a “resonance mechanism” for population subgroups with heightened exposure to crime and police contact, which are far from rare for young people in New York, particularly young people of color (Solis, Portillos, and Brunson Reference Solis, Portillos and Brunson2007; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014).

More specifically, our multivariate findings based on the sample of Black and Latino/a respondents lend support for the idea that racial identification matters in the configuration of opinions about the police, particularly for legitimacy. This influence operates directly and indirectly by amplifying the effects of some contacts (last stop) but not others (cumulative events) and across both action-based and perceptual measures. In the following section, we discuss these results in the context of the broader literature and chart new directions for theory and research.

DISCUSSION

Over a decade ago, Ron Weitzer and Steven Tuch (Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005, 1024) wrote: “Race structures citizen views of police racial bias, as it does other aspects of policing.” We agree. However, the specification of the association between race and opinions about the police has remained elusive, especially in quantitative studies. In part, this is due to the “uncritical” use of racial categories (Owusu-Bempah Reference Owusu-Bempah2017, 26), the lack of integrated frameworks that combine procedural justice with other perspectives, and the relative absence of models that consider concurrently multiple forms of police contacts and appraisal mechanisms. Instead, conventional frameworks have often limited the role of race and ethnicity to issues of selection into police contacts or obscured the notion of identity by equating it with demographic controls or other proxies for neighborhood or value orientation. Our work contributes to the growing set of more expansive views that seek to reconsider these notions as reflective of broader struggles with the maintenance of specific forms of social order and political representation (Fassin Reference Fassin and Fassin2015; Legewie Reference Legewie2016; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2018). To this end, we propose an individual-level framework and empirical strategy that link opinions about the police to both cumulative and discrete encounters, their subsequent appraisal, and variation in the relative centrality that respondents give to race and ethnicity as part of their own identity. In this conceptualization, racial identity acts as a situated form of self-representation and knowledge that links (microlevel) attitudes toward the police to (macrolevel) processes of social integration and regulation.

We find that both racial identification and experiences with abuse and discrimination vary across people of color, but their experiences with abuse and discrimination largely do not; three out of five respondents reported discrimination in the past year, and four out of five felt disrespected during their last police stop. On average, the young people in our sample had been stopped eight times—about three times a year since turning twenty-one years of age and becoming “full” (adult) members of society. We also found that racial identification shapes perceptions of police legitimacy irrespective of race and other markers of stratification by gender or national origin (Lee, Steinberg, and Piquero Reference Lee, Steinberg and Piquero2010; Kubrin, Zatz, and Martinez Reference Kubrin, Zatz and Martinez2012; Oliveira and Murphy Reference Oliveira and Murphy2015).

Our results also lend support to the robust literature on the direct association between indicators of procedural justice based on the perceived “quality” of police encounters and more general dispositions toward the police (Sunshine and Tyler Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003a; Fagan et al. Reference Fagan, Braga, Brunson and Pattavina2016). However, results from our moderation models indicate that this association is not only sensitive to specific domains of evaluations about the police but also, and perhaps more critically, sensitive to racial identification and to the appraisal process of specific modalities of police contact. In particular, we found that racial identification amplifies the negative association between the extent of coercion exerted by the police during the last stop and broader ratings of police legitimacy. Consistent with our theoretical framework, we argue that these ratings of police legitimacy are anchored on individual experiences (stops) and their specific rendition (behavior-based markers of police use of coercion) that are reconciled with broader assessments about social integration and control. In our sample, this micro-macro link is provided by racial identity.

A similar pattern emerges for the measure of procedural justice based on feelings of disrespect during the last reported stop. For people who identify strongly with their racial/ethnic group, we once again observe the expected, inverse relationship between disrespect and perceptions of legitimacy. In comparison, a weaker, but still negative, association between these two variables is observed for those with low values on the racial/ethnic identity scale. Further, our analyses suggest that, while both perceptions of respect and the coercive action scale are based on the same “last stop,” the conditional effect of racial identity is stronger for the former term. This lends some credence to the notion that identity may influence legitimacy not only as a moderator of “objective” behavioral measures but also in terms of the cognitive process associated with some types of appraisals and not others—in this case, the saliency of “respect” is consistent with other studies that highlight its connection to varying ideals of decency and morality (Brunson and Miller Reference Brunson and Miller2006). In contrast, the public value of “satisfaction” is less clearly connected to normative standards or particular group identities.

More generally, our contrasting findings on measures of quality of treatment suggest that concepts such as “respect” and “satisfaction” may be sensitive to preconceived notions of subordination and recognition that could vary not only in terms of racial identification but also across age, gender, and other forms of identity. This is important given the growing use of procedural justice models in national contexts with varying forms of social conflict and “moral economies” (Fassin Reference Fassin and Fassin2015). In the United States, where our research was based, issues tied to racial/ethnic identity and affiliation mark debates about both crime and crime control. Other types of identity may be more salient for the configuration of police attitudes in other contexts with a different set of police powers and practices and varying forms of social stratification (Radburn et al. Reference Radburn, Stott, Bradford and Robinson2018).

Importantly, the conditioning effects of racial identity do not apply to other measures of police contact or to ratings of police effectiveness in our study. As noted by Gibson and Nelson (Reference Gibson and Nelson2018, 118), this may be due to the fact that “sociotropic” frames of interpretation used by individuals to reinterpret discrete experience as “having meaning for the group and the larger political system” may only be activated in connection to normative judgments such as those reflected in our measure of legitimacy. We argue that ratings of police legitimacy are particularly sensitive to this cognitive process as they imply a broad judgment over the moral economy that sustains law enforcement practices. As such, we contend that this judgment is not only social but also an enduring perspective on the “quality” of the bond between specific citizens and the state (see Bell Reference Bell2017). Our findings on the significant relationship between legitimacy and discrete markers of threat (discrimination) and group affiliation (racial identity) support this general idea. The fact that stops matter for legitimacy, particularly when considered in conjunction with racial identification, also supports the notion that lived (as well as shared) experiences become signals that individuals identify and project into adjacent semantic domains.

Moreover, we argue that patterns of association between individual experiences of police contact and varying forms of group identity are better captured by models that examine police attitudes across multiple domains of valuation and include both “objective,” narrowly defined patterns of police actions or behaviors (for example, “officers displayed a weapon,” “officers identified themselves”) as well as more “subjective,” perceptual measures that consider quality of treatment as well as other dimensions of procedural justice. Whereas the specificity of the former set of measures facilitates revisions to policies and training given their alignment with institutional procedures and local contexts (Lum and Nagin Reference Lum and Nagin2017), the use of subjective measures may be better positioned to account for appraisal mechanisms grounded in local experience and “situated knowledge” (Jackson Reference Jackson2001; Goffman Reference Goffman2014). As noted by Daniel Nagin and Cody Telep (Reference Nagin and Telep2017), these distinctions are crucial to understanding the multiple “sources” of legitimacy and legal compliance.

Still, there is much that these quantitative data cannot tell us about the role of race, ethnicity, and identity in the police appraisal process. We have no information on how individuals conceptualize the meaning of being “being Black” or “being Latina and Black,” and, therefore, we assume that the “collective consciousness” mobilized by police encounters is uniform and largely negative. This may not always be the case as intersections of race, class, gender, and national origin often result in varying forms of group identity and exposure to police contact—for example, via stereotypes of dangerousness for Black males versus stereotypes of inferiority for Black females (Rengifo and Pater, Reference Rengifo and Pater2017) or in connection with the protective function ascribed to the police by members of immigrant groups that rate them relative to law enforcement in their home countries (Menjivar and Bejarano Reference Menjivar and Bejarano2004). Heterogeneity within racial groups also implies that the constitutive role that police encounters play in identity formation may be substituted or supplemented in some cases by contact with other institutions: educational institutions, religious organizations, neighborhood organizations.

Importantly, our assessment of racial identity and other key variables was limited by the design of the study, which targeted young people with a prior police-initiated contact. While this strategy enabled us to deepen our understanding of these interactions, it likely conditioned the range of observed variation in measures of procedural justice and ratings of legitimacy/effectiveness. As such, it is unclear whether the effects of racial identity noted in this study can be replicated in samples with lower levels of police contact. However, it is worth noting that our findings on specific correlates of legitimacy are generally aligned with results from prior New York City research (Solis, Portillos, and Brunson Reference Solis, Portillos and Brunson2007; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014).

More critical theory paired with more rigorous research designs can help with the additional specification of the postulates developed in this article. The empirical assessment of how (and when) racial identification matters was admittedly bounded by the use of cross-sectional data and the limitations of the sample discussed above. Thus, we cannot explore whether racial identification or previous perceptions of the police shape how people evaluate their encounters with law enforcement or the extent to which legitimacy or effectiveness vary across groups of people with or without personal contact. These are important omissions because research has found that perceptions of police encounters often do not map onto actual police behaviors, and police contact tends to undermine citizen attitudes (for example, Worden and McLean Reference Worden and McLean2017).

In addition, some measures are incomplete or missing from this analysis. For example, the measure of legitimacy only captures its normative foundation. Our survey did not include indicators of the police officers’ race or any other demographic attributes. And we lacked measures of other forms of group identification including the sense of “shared fate” or the extent to which people identify with the police, the in-group, or the nation. As noted by prior research, individuals may actualize different identities in different contexts, and these may change over time and in connection to specific experiences, including police contact (Stets and Burke Reference Stets and Burke2000; Lee, Steinberg, and Piquero Reference Lee, Steinberg and Piquero2010). While our use of cumulative/lifetime experiences for stops and other police encounters helps to address some of these issues, research is needed to understand how other types of identities act in concert with racial identity to shape the meaning that people take away from their encounters with the law.

Future research on race and policing may consider going beyond assessments of law enforcement institutions and practices as to better anchor opinions about the police with opinions about the state and other bureaucracies that also enforce a disciplinarian model. Emerging work on housing regulation and other adjacencies of the punitive turn are encouraging developments in that regard (Fernández-Kelly Reference Fernández-Kelly2015; Ryo Reference Ryo2016; Lara-Millán and Gonzalez Van Cleve Reference Lara-Millán and Gonzalez Van Cleve2017). As part of these ongoing efforts, it is critical to recall that the standard of “lawfulness” used to assess state policies and institutions not only reflects a minimum threshold for judgment but also a distinct “moral economy” (Fassin Reference Fassin and Fassin2015). The notion of legitimacy, while potentially difficult to operationalize in terms of policy, provides a key bridging role in terms of micro-macro links across domains of experience, ideology, and stratification and also a potential avenue to reconsider the role of law as a mechanism of social integration and not just as an instrument of coercion.