No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

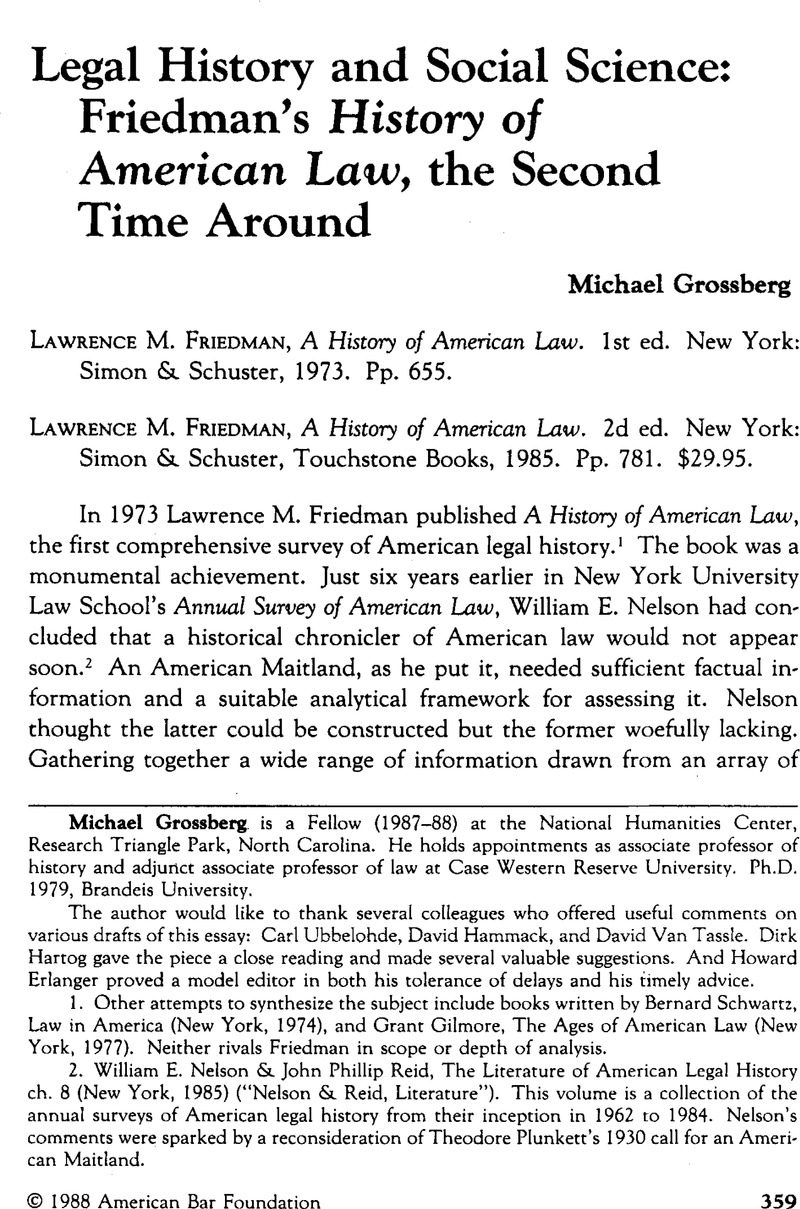

Legal History and Social Science: Friedman's History of American Law, the Second Time Around

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 December 2018

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Bar Foundation, 1988

References

1. Other attempts to synthesize the subject include books written by Bernard Schwartz, Law in America (New York, 1974), and Grant Gilmore, The Ages of American Law (New York, 1977). Neither rivals Friedman in scope or depth of analysis.Google Scholar

2. William E. Nelson & John Phillip Reid, The Literature of American Legal History ch. 8 (New York, 1985) (“Nelson & Reid, Literature”). This volume is a collection of the annual surveys of American legal history from their inception in 1962 to 1984. Nelson's comments were sparked by a reconsideration of Theodore Plunkett's 1930 call for an American Maitland.Google Scholar

3. A History of American Law 10(New York, 1973); the preface to the first edition is also reprinted in the second. In this essay the first edition is cited as “History, 1973” and the second edition as “History, 1985.”Google Scholar

4. History, 1973, at 15-16. Most reviewers lauded Friedman's heroic effort at synthesis; yet a persistent skepticism about his particular use of social science methodology also emerged. The most denunciatory critique came from Mark Tushnet, Perspectives on the Development of American Law: A Critical Review of Friedman's A History of American Law, 1977 Wis. L. Rev. 81-109; but see also the review by G. Edward White, 59 Va. L. Rev. 130-41 (1973), which questioned Friedman's use of social science.Google Scholar

5. History, 1985, at 12, 18, 19, 29.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

6. To take one measurement, Nelson observed that more work was published in 1979-80 than in all the years before 1960. Nelson & Reid, Literature 304.Google Scholar

7. Thomas Bender, Wholes and Parts: The Need for Synthesis in American History, 73 J. Am. Hist. 122 (1986).Google Scholar

8. Friedman's pioneering work has made him the most productive scholar in the field. Since he began publishing in the early 1960s, he had produced an incredible number of articles and monographs. Moreover, his work has been the most thorough application of the Wisconsin approach. A listing of the publications Friedman seems to consider most relevant to the volume under review can be found in the bibliography of the second edition (History, 1985, at 715-16).Google Scholar

9. This point is based on a comparison of History, 1973, at 30-32 and History, 1985, at 34-36.Google Scholar

10. These points are based on a comparison of History, 1973, at 184-86 and History, 1985, at 208-11.Google Scholar

11. Cal. L. Rev. 487 (1965).Google Scholar

12. This assessment is based on a comparison of History, 1973, at 397-405 and History, 1985 at 454-63.Google Scholar

13. History, 1985, at 18; History, 1973, at 14.Google Scholar

14. Herbert Jacob, Law and Politics in the United States 9, 13, 121-51, 152-70 (Boston, 1986).Google Scholar

15. The Emergence of Social Science 67 (Urbana, Ill., 1977).Google Scholar

16. History, 1973, at 9.Google Scholar

17. Nelson describes the shifts in the field by suggesting that “the discipline of American legal history has changed in recent decades from one in which nearly all scholars in the field shared a common sense of purpose to a field in which different scholars pursue quite different ends.” Nelson & Reid, Literature 303. For his general assessment of this development and its consequences see id. at ch. 17.Google Scholar

18. For helpful assessments of the Hurst approach see Gordon, Robert, Hurst, J. Willard and The Common Law Tradition in American Legal Historiography, 10 Law & Soc'y Rev. 9 (1975); Stephen Diamond, Legal Realism and the Historical Method: J. W. Hurst and American Legal History, 77 Mich. L. Rev. 784–94 (1979); Review Symposium: The Work of J. Willard Hurst, 1985 A.B.F. Res. J. 113-44.Google Scholar

19. The State of American Legal History, 17 Hist. Teacher 107, 110 (1983). Of course, Friedman does not speak for all of those in the Hurst tradition, which has produced a varied group of scholars. The work of historian Harry N. Scheiber is most divergent from key elements in Friedman's orthodox Wisconsin approach. See, e.g., his call to retrieve American constitutional history, a casualty of the private law focus on most Hurstians, American Constitutional History and the New Legal History: Complementary Themes in Two Modes, 68 J. Am. Hist. 337-SO (1981).Google Scholar

20. Friedman, 17 Hist. Teacher, at 110.Google Scholar

21. He does note that some legal historians (he mentions Nelson, John Reid, Robert Gordon, and Michael Hindus) do not fall within either the Hurst School or the Critical one. Id. at 108-9.Google Scholar

22. This disenchantment is perhaps most vividly presented in calls for the return of the narrative to history writing. Indeed, Lawrence Stone's plea for the narrative has become a signal event in the discipline because he had so fervently championed a social-science-dominated historical methodology; The Revival of Narrative: Reflections on a New Old History, 85 Past & Present 3-24 (1979). Similarly, in a recent assessment of social history, Olivier Zunz voiced the widely held view: “Social historians should now begin to free themselves from the theories of social scientists and use the vast accumulation of historical social description to generate their own theories. Greater independence from social science will also make it easier for social historians to integrate their findings with those of political and economic historians and build sound explanatory frameworks. It will also permit the links between intellectual and social trends to be more readily perceived. Understanding how ideas contribute to the course of history is as crucial as understanding how history shapes ideas.” The Synthesis of Social Change: Reflections on American Social History, in Zunz, ed., Reliving the Past: The Worlds of Social History 100 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1985)(“Zunz, Synthesis of Change”). See, e.g., Scheiber, 68 J. Am. Hist., at 338 (cited in note 19), for a discussion of similar developments in political science. Attacks on Friedman's use of social science methods are hardly new to him. As early as 1965, New York University legal historian John Reid took Friedman to task for his “behaviorist interpretation” in the article on occupational licensing cited in note 11; saying that Friedman was a young man, Reid paternalistically suggested that if “he can discipline himself to avoid such speculations, he may have something to contribute to American legal history in the years to come.” Nelson & Reid, Literature 81-82(cited in note 2). Such criticism did not daunt Friedman, and clearly he has had a lot to contribute to American legal history. But now the skepticism among historians is much greater than when Reid chided him.Google Scholar

23. 17 Hist. Teacher, at 106.Google Scholar

24. Appleby, Joyce, Republicanism and Ideology, 37 Am. Q. 462–63 (1985).Google Scholar

25. Maier, Pauline, A Pearl in a Gnarled Shell: Gordon S. Wood's The Creation of the Amerrcan Republic Reconsidered , 44 Wm. & Mary Q. 583 (1987); the entire forum on Wood's book, which includes a reaction by Wood himself, occupies pp. 549-640.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

26. History, 1973, at 107, 111, 112, 114, 115.Google Scholar

27. Id at 113, 117.Google Scholar

28. History, 1973, at 113, 117.Google Scholar

29. See in particular Wood, The Ambiguity of American Law, in The Creation of the American Republic ch. 24(Chapel Hill, N.C. 1969)(“Wood, Creation”); and Hendrik Hartog, Distancing Oneself from the Eighteenth Century: A Commentary on Changing Pictures of American Legal History, in Hartog, ed., Law in the Revolution and the Revolution in Law 229-57(New York, 1981).Google Scholar

30. Appleby, 37 Am. Q. at 463.Google Scholar

31. Wood, Creation 47.Google Scholar

32. Shallope, Toward a Republican Synthesis: The Emergence of an Understanding of Republicanism in American Historiography, 29 Wm. & Mary Q. 49 (1972). The seminal books that launched the attempt to recover republicanism include Wood's volume, that of his mentor, Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), and the work of J. G. A. Pocock, especially The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Republican Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (Princeton, N.J., 1975).Google Scholar

33. Edward Countryman, Of Republicanism, Capitalism, and the “American Mind,” 44 Wm. & Mary Q. 559 (1987); for a useful introduction to the debate on republicanism see the articles in Republicanism in the History and Historiography of the United States, 37 Am. Q. 461–598 (1985).Google Scholar

34. The Republican Ideology of the Revolutionary Generation, 37 Am. Q. 474 (1985).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

35. Appleby, 37 Am. Q. at 462.Google Scholar

36. Wood, , Ideology and the Origins of Liberal America, 44 Wm. & Mary Q. 629 (1987). For a discussion of the relationship of the scholarship on republicanism to larger movements in intellectual history see Robert Darton, Intellectual and Cultural History, in Michael Kammen, ed., The Past Before Use: Contemporary Writing in American History, 327-54, esp. 343-44 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1980) (“Kammen, Past”); for a recent example of these methods applied in legal history see Stephen Conrad, Polite Foundation: Citizenship and Common Sense in James Wilson's Republican Theory, 1984 Sup. Ct. Rev. 359-88.Google Scholar

37. Friedman, 17 Hist. Teacher, at 113(his emphasis). The difficulties of integrating republicanism into a larger analytical approach ought not be minimized, however. For a critique of my use of the term see Emily Field Van Tassel, Judicial Patriarchy and Republican Family Law, 74 Geo. L. Rev. 1567(1986).Google Scholar

38. History, 1973, at 12. For an earlier attempt to define a social history of American law, one much like Friedman's, see Richard B. Morris, The Courts, the Law, and Social History, in Morris N. Forosch, Essays in Legal History in Honor of Felix Frankfurter 409-22 (Indianapolis, 1966).Google Scholar

39. Zunz, Synthesis of Change (cited in note 22). Typical of the era was French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie's declaration: “Tomorrow's historian will program computers or will cease to exist.” The Territory of the Historian 14 (trans. Chicago, 1979).Google Scholar

40. Harold Woodman, Preface in Elizabeth Fox-Genovese & Eugene D. Genovese, The Fruits of Merchant Capital: Slavery and Bourgeois Property in the Rise and Expansion of Capitalism xviii (New York, 1983) (“Genoveses, Fruits”).Google Scholar

41. This has been in part an implicit recognition of what the Genoveses call the “political crisis of social history”; by that they mean the inability of social historians to integrate political power and public institutions into their analyses. Genoveses, Fruits 7; Bender, 73 J. Am. Hist. 123–32, (cited in note 7).Google Scholar

42. For general discussions of these issues see Zunz, Synthesis of Change (cited in note 22), and Peter N. Stearns, Toward a Wider Vision: Trends in Social History, in Kammen, Past, at 205-30 (cited in note 36) (“Stearns, Toward a Wider Vision”). Stearns, in particular, makes the point that the methodological controversies among social historians are not merely repeats of earlier debates over the value of quantification but are rather more fundamental inquiries into the notion of social analysis itself: “Certainly, issues remain to be debated, related to but broader than the choice of quantitative or qualitative emphasis. The concern for outlook or mental attitude relates social historians not only to cultural but also to psychological theory, in intent if not usually in conceptional arsenal.” Stearns, id. at 229.Google Scholar

43. Zunz, Synthesis of Change 58.Google Scholar

44. Stearns, Toward a Wider Vision.Google Scholar

45. Lears advocates that social historians turn to Gramsci because the concept of cultural hegemony can aid “social historians seeking to reconcile the apparent contradiction between the power wielded by dominant groups and the relative cultural autonomy of subordinate groups whom they victimize. T. Jackson Lears, The Concept of Cultural Hegemony: Problems and Possibilities, 90 Am. Hist. Rev. 568(1985); and for a related argument cast in terms of legal history see Peter Linebaugh,(Marxist)Social History and (Conservative) Legal History: A Reply to Professor Langbein, 60 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 212-43 (1985). For examples of the social history mentioned in the text see Peter Dublin, Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860 (New York, 1979); Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788-1850 (New York, 1984); Paul Mattingly, The Classless Profession: American Schoolmen in the Nineteenth Century (New York, 1975).Google Scholar

46. Genoveses, Fruits 198 (cited in note 40).Google Scholar

47. History, 1973, at 226; and for Friedman's comments on the issue of economic determinism see Friedman, 17 Hist. Teacher, at 110-11(cited in note 19). For Nash's argument see his articles A More Equitable Past? Southern Supreme Courts and the Protection of the Antebellum Negro, 48 N.C.L. Rev. 197 (1970); id., Reason of Slavery: Understanding the Judicial Role in the Peculiar Institution, 32 Vand. L. Rev. 7 (1979); id., In re Radical Interpretations of American Law: The Relationship of Law and History, 82 Mich. L. Rev. 274–345(1983).Google Scholar

48. Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (New York, 1982); James Oakes, The Ruling Race: A History of American Slaveholders (New York, 1982).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

49. On this point see William Forbath, Hendrik Hartog, & Martha Minow, Introduction: Legal Histories from Below, 1985 Wis. L. Rev. 759-66; Genoveses, Fruits 370.Google Scholar

50. “Society Is Not Marked by Punctuality in the Payment of Debt”: The Chattel Mortgage of Slaves, in David J. Bodenhamer & James W. Ely, Jr., eds., The Ambivalent Legacy 160(Jackson, Miss., 1984)(“Bodenhamer & Ely, eds.”); Mark Tushnet, The American Law of Slavery, 1810-1860: Considerations of Humanity and Interest (Princeton, N.J., 1981); Paul Finkelman, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1981) (“Finkelman, Imperfect Union”); and Nash, 32 Vand. L. Rev., at 49 (cited in note 47).Google Scholar

51. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom 284 (New York, 1976). And see James Oakes, From Republicanism to Liberalism: Ideological Change and the Crisis of the Old South, 37 Am. Q. 569-70 (1987), for an effort to link changes in republicanism to the beliefs of white yeomen and black slaves.Google Scholar

52. Genoveses, Fruits 365; and see Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll 25-49 (New York, 1974). For a critique of Genovese's approach see John Patrick Diggins, Comrades and Citizens: New Mythologies in American Historiography, 90 Am. Hist. Rev. 616 (1985).Google Scholar

53. E.g., see the articles collected in Bodenhamer & Ely, eds.(cited in note 50); and see the pieces by Paul Finkelman and William Wiecek in the forthcoming proceedings of a March 1987 conference on “The South and the American Constitutional Tradition,” held at the University of Florida. For an adherent of the Wisconsin school who gives greater credence to regional differences see Harry N. Scheiber, Xenophobia and Parochialism in the History of the American Legal Process, 23 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 625-61 (1982); id., Federalism, the Southern Regional Economy, and Public Policy Since 1865,” in Bodenhamer & Ely, eds,. at 69-105.Google Scholar

54. The Law Between the States, in Bodenhamer & Ely, eds., at 42; for a more complete discussion of Friedman's views on legal culture see Total Justice 38-43, 97-101(New York, 1985).Google Scholar

55. For a discussion of these methodological issues in a larger North American context, see Michael A. Goldberg & John Mercer, The Myth of the North American City: Continentalism Challenged (Vancouver, Can.: 1986).Google Scholar

56. History, 1973, at 229.Google Scholar

57. In contrast, Finkelman offers this view of the relationship between law and society: “The conflict was undoubtedly social and economic at its roots, but the arguments were often legal. And as law is both a molder of society and a product of it, these legal arguments were as important and real as the economic and social issues.” Finkelman, Imperfect Union 310 (cited in note 50).Google Scholar

58. Friedman, 17 Hist. Teacher, at 110. For a similar questioning of the notion of law as a reflection of society in terms of English legal history, see Palmer, Robert C., The Origins of Property in England, 3 Law & Hist. Rev. 1–50 (1985).Google Scholar

59. We need to approach the issues in terms like those political historians are using to understand American political culture. Particularly helpful are definitions such as that of political culture as “the system of empirical beliefs, expressive symbols, and values which define the situation in which political actions takes place.” Lucien Pye & Sidney Verba, Political Culture and Political Development 513 (Princeton, N.J., 1965); for an application of this definition see Jean Baker, Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Ithaca, N.Y., 1983); id. Republicanism in the Antebellum North, 37 Am. Q. 538-39 (1987).Google Scholar

60. Bender, 73 J. Am. Hist., at 122 (cited in note 7).Google Scholar

61. Bellah et al., Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life 297(Berkeley, Cal., 1985).Google Scholar