INTRODUCTION

This article focuses on people’s long-term contractual commitments. We ask whether people’s perceptions of the intertemporal malleability of their and others’ personalities correlate with their tendency to engage in long-term contracts.

There is a large body of scholarship in social psychology (to be surveyed below) that shows that people differ in their views as to the intertemporal malleability of the self and that these differences correlate with people’s behaviors, beliefs, and types of interactions. Yet, this rich body of literature fails to distinguish between the effects of people’s views of the intertemporal malleability of their own personalities and the effects of their views of the intertemporal malleability of other people’s personalities. This gap implies that while this literature may help capture people’s tendency to make intrapersonal intertemporal commitments (as in vows), it seems insufficiently refined for studying their tendency to make long-term contractual commitments, which involve interpersonal commitments.

Adding the missing piece to the existing literature is important both for its own sake and because long-term contracts, especially the relational contracts on which we focus here, play a significant role in our social life. These long-term contracts are situated between purely intimate interpersonal interactions, which are valuable only if driven solely by ongoing internal motivation, and mundane sales contracts, epitomized by the canonical case of a future delivery of a widget for an agreed-upon price, which are purely instrumental. Contract law, at least in a liberal setting, has very little to say about people’s internal motivations. But its ambition goes well beyond the latter pole of the widget-like spot exchange projected into the future, which does not implicate people’s personality, and may fit into the simple “classical” picture of This for That (Macneil Reference Macneil and McAuslan2001, 300–01). Most contracts are different: they involve long-term interactive engagements that require complex adaptations (Goetz and Scott Reference Goetz and Scott1981).

These long-term contracts, and in particular relational contracts, are best understood as the parties’ joint plan (Dagan Reference Dagan2021). They necessarily involve both a commitment of oneself, which encumbers the autonomy of one’s future self, and a commitment of the other party, which is often critical to one’s ability to plan and is thus conducive to her own self-determination. Therefore, the tendency to make such long-term commitments may implicate both beliefs about the relative intertemporal malleability of one’s own personality and beliefs about the relative intertemporal malleability of the other party’s personality. This means that what is missing from that empirical literature, and crucial for our purposes, is a study that distinguishes between people’s beliefs regarding the malleability of their own personality and their beliefs as to the malleability of others’ personalities, and then tests whether these two sets of beliefs affect people’s tendency to engage in long-term contractual commitments.

This is, as noted, exactly the task of this article, in which we zoom in on relational contracts whose performance implicates the person of the promisor (as where the promisor is the promisee’s employee). We seek to study how people perceive these types of long-term commitments. Our question, more specifically, is whether their beliefs that their and others’ personalities are relatively malleable (or not) correlate with their tendency to engage in such long-term contracts.

Because people’s beliefs about the intertemporal malleability of their own personality tend to be correlated with their beliefs about the malleability of other people’s personalities, it is challenging to empirically examine our research question through observational data regarding people’s actual experiences. But our question can be tested through a survey experiment. The survey experiment we designed exploits the variation that exists (as we’ve shown) between people’s perceptions of themselves and others to better understand what makes them make long-term commitments. Testing our question in two contexts—a noncompete employment term and covenant marriage—we find that the more people believe that their own personality is intertemporally malleable the less they tend to make long-term commitments; by contrast, we demonstrate that the more they believe that others’ personalities are malleable, the more they tend to engage in such commitments.

Our findings seem intuitive and they indeed are. But we think that highlighting the effect of the variation between the perception of people’s own malleability and others’ is nonetheless significant. It implies that people’s intuitive tendencies to make long-term commitments align with those that underlie liberal contract law, which is careful about enforcing contracts that constrain the self-determination of contractors’ future selves. Our study may also open up directions for future research as per the possible causes of people’s divergent views as to the malleability of their and others’ personalities, as well as the possibility that these views may correlate with socioeconomic inequalities and that they may generate systemic effects on parties’ bargaining power in the context of certain long-term contractual commitments.

Section I sets the stage by clarifying the value added of our experiment, and Section II describes its design. Section III presents our empirical results, and Section IV provides discussion.

I. WHY DO PEOPLE ENGAGE IN LONG-TERM CONTRACTUAL COMMITMENT?

Studies in social psychology have shown that people vary in the extent to which they believe personality is malleable (as opposed to fixed) and that these beliefs about the self tend to affect how people perceive others and behave toward them (Chiu, Hong, and Dweck Reference Chiu, Hong and Dweck1997; Molden and Dweck Reference Molden and Dweck2006; Rattan and Dweck Reference Rattan and Dweck2010; Dweck Reference Dweck2013). These studies have distinguished people who believe that personalities are fixed intertemporally (often referred to as entity theorists) and people who believe that personalities are malleable (incremental theorists). This rich body of research shows that the latter are less confident than the former that personality-related behaviors are consistent across circumstances and domains. Therefore, they are less likely to form early impressions of others (Butler Reference Butler2000) and are less likely to believe that specific behaviors are good predictors of people’s global character (Chiu, Hong, and Dweck Reference Chiu, Hong and Dweck1997; Dweck, Hong, and Chiu Reference Dweck1993). Relatedly, people who believe that personalities are malleable are less likely to believe that it is possible to infer from a person’s behavior in one situation how this person would behave in a new situation (Chiu, Hong, and Dweck Reference Chiu, Hong and Dweck1997). Concomitantly, they are also more likely to believe that change and improvement in others are possible and to behave accordingly (Kammrath and Dweck Reference Kammrath and Dweck2006; Rattan and Dweck Reference Rattan and Dweck2010; Schumann and Dweck Reference Schumann and Dweck2014).

We propose to distinguish between people’s beliefs about whether their own personalities are malleable on the one hand and their beliefs about whether other people’s personalities are malleable on the other hand, and to test whether these two sets of beliefs affect people’s tendency to engage in long-term contractual commitments. This distinction is important in the context of contractual relations because such relations simultaneously involve both the commitment of oneself, which limits one’s future options, and the commitment of the other party, which provides the assurance of her future performance.

Building on the existing literature and on the intertemporal interpersonal nature of long-term contractual commitments, we predict that the tendency to believe that one’s own personality is relatively malleable, so that a current commitment might be perceived by one’s future self as an undesirable encumbrance, will be associated with a smaller tendency to engage in a long-term contractual commitment. We further predict that the tendency to believe that other people’s personalities are relatively malleable, so that their future selves might repudiate a plan that both parties currently contemplate, will be associated with a greater tendency to engage in such long-term contractual commitment.

To be sure, we naturally assume that people’s beliefs about themselves and their beliefs about others are correlated, so that people who tend to believe that their personality is relatively malleable also tend to think that other people’s personalities are malleable. Yet, we wish to exploit the variation that does exist in people’s perceptions of themselves and others to better understand what makes people commit. To do so, we build on the existing measure of views regarding the intertemporal fixity of personality but construct three submeasures: the first for views regarding the fixity of one’s own personality; the second for views regarding the fixity of other people’s personalities; and the third for views regarding the fixity of one’s own and others’ personalities.

II. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

The experiment involved American participants and was conducted in the spring of 2021. Participants, recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk (a crowdsourcing marketplace), were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions. In the first condition participants were asked to report their agreement with the four items presented to them, which were designed to measure their perceptions regarding the fixity of their own personality (the first measure). In the second condition participants were asked to report their agreement with four other items presented to them, which were designed to measure their perceptions regarding the fixity of other people’s personalities (the second measure). In the third condition participants were asked to report their agreement with two items that measure perceptions regarding the fixity of participants’ own personalities and two that measure their perceptions regarding the fixity of other people’s personalities (the third measure). Finally, the fourth condition was a control condition (in which no perceptions were measured). Participants reported their agreement with each of the four items presented to them item on a 5-point scale (1 = very strongly disagree and 5 = very strongly agree).

The three measures we used were adopted from the “implicit theory of personality measure” (Dweck, Chiu, and Hong Reference Dweck, Chiu and Hong1995; Chiu, Hong, and Dweck Reference Chiu, Hong and Dweck1997; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Chiu, Dweck, Lin and Wan1999). In the original “implicit theory of personality measure,” a few items address views of one’s own personality and others address views of the personalities of others. The three measures we used in the experiment borrow the four items from the original measure but focus either only on participants’ own personalities (the first measure), only on other people’s personalities (the second measure), or on both (the third measure; items randomly addressed participants’ own personalities or others’).Footnote 1 We reverse the scores of the two malleability items to create a four-item fixity measure (“my personality is fixed”), with higher scores indicating a perception of a fixed personality of self/others.

Participants were then randomly assigned one of two scenarios describing long-term relational contractual commitments. The two scenarios we chose involved relational contractual commitments that might compromise the self-determination of the promisor’s future self and implicate their personality: the first dealt with a noncompete term in an employment contract; the second involved a covenant-marriage-like agreement.

With both scenarios, participants were presented with a choice between a long-term contractual commitment with a high payoff and a shorter one with a lower payoff and were asked to report which one they would prefer. The first scenario presented a choice between “A 5yr commitment to not compete (after leaving) and a 30% raise in your salary (the raise applies only to the first 5 yrs of employment)” and “A 1yr commitment to not compete.” In the second scenario, participants were asked to choose between “A covenant marriage in which you have to live apart from each other for two years before a divorce can be granted” and “A non-covenant marriage (with a no-fault divorce).” Participants were then asked a set of demographic questions and were instructed as to how to receive payments.

Naturally, we assume that many factors might affect people’s tendencies to commit to a longer noncompete term in an employment context or to a longer covenant-marriage-like agreement. We also assume that the context of employment and the context of marriage are significantly different. Here however we wish to focus on the tendencies to perceive one’s own and others’ personalities as malleable. Thus, significant effects of perceptions of one’s own and others’ personalities on the tendency to make long-term contractual commitments would imply that in addition to all other factors that might affect one’s tendency to engage in longer commitments, perceptions of malleability matter.

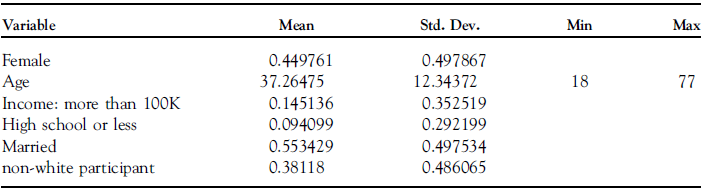

Altogether 627 participants passed the attention tests and completed the full questionnaires. Table 1 presents the sample characteristics.

TABLE 1. Descriptive Statistics

One hundred and fifty four participants participated in the “own personality is fixed” condition; one hundred and fifty five participants participated in the “others’ personalities are fixed” condition; one hundred and fifty one participants participated in the “mine and others’ personalities are fixed”; and one hundred and sixty seven participants participated in the control condition. Out of the six hundred and twenty seven participants, three hundred and twenty eight were presented with the first scenario (“noncompete”) and two hundred and ninety nine with the second scenario (“covenant marriage”).

III. RESULTS

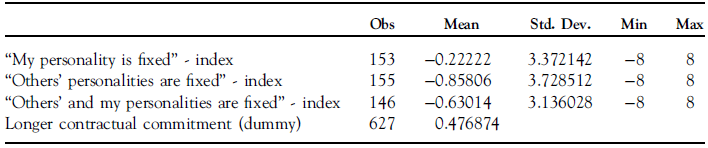

In Table 2, we report participants’ responses to the questions we asked them (the fixity index) and their willingness to make a longer contractual commitment.

TABLE 2. Participants’ Responses

Participants’ tendency to prefer a longer commitment varies by scenario. Whereas in the “noncompete” employment scenario 60 percent of the 299 participants were interested in entering into the longer commitment, in the covenant marriage scenario only 37 percent of the 328 participants were interested in entering into the longer commitment (z<0.01).

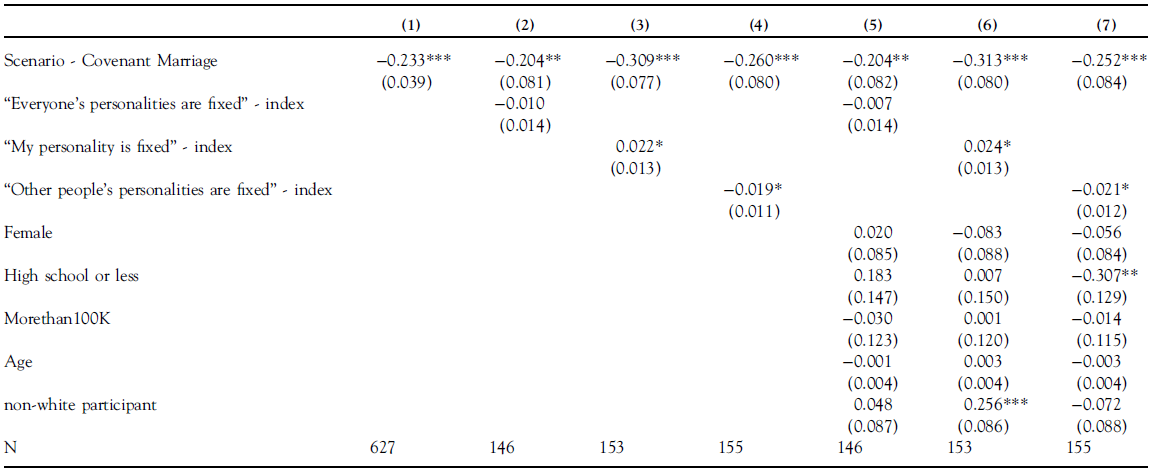

We tested whether participants’ willingness to make a longer commitment varies according to their beliefs that their and others’ personalities are relatively malleable. In Table 3 we report participants’ tendency to prefer a longer contractual commitment by the scenario to which they were exposed and their perceptions regarding the fixity of their and others’ personalities. The table reports marginal effects. Marginal effects can be interpreted as the change in the probability of preferring a longer contractual commitment given a one-unit change in the independent variables (such as being exposed to the “covenant marriage” compared to the “noncompete” scenario). We first investigate the effects of these scenarios (Model 1). We then include the fixity index for participants who were asked general questions about the fixity of their and others’ personalities (Model 2).

TABLE 3. Probit Models Predicting the Tendency to Make a Longer Commitment (Marginal Effects)

Marginal effects; standard errors in parentheses.

* p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

In Model 3, we include the fixity index for people who were asked questions about the fixity of their own personalities. In Model 4, we include the fixity index for the people who were asked questions about the fixity of other people’s personalities. Models 5, 6, and 7 include demographic controls.

In all models, participants who were exposed to the “covenant marriage” scenario were less interested in entering into a longer commitment, compared to those who were exposed to the “noncompete” scenario (p<0.01). Being exposed to the covenant marriage scenario generated at least 0.204 change in the probability of preferring a longer contractual commitment, compared to being exposed to the noncompete scenario. Models 2–7 are each estimated on a different population: those who were asked about the fixity of everyone’s personalities (theirs and others’) (Models 2 and 5), those who were asked about the fixity of their own personalities (Models 3 and 6), and those who were asked about the fixity of others’ personalities (Models 4 and 7).

Interestingly, people’s combined perceptions regarding the fixity of their and others’ personalities (Models 2 and 5) were not associated with their tendency to make longer contractual commitments. However, as predicted, the more people thought that their own personalities were fixed, the higher the probability that they would be interested in entering into a long-term commitment (Models 3 and 6) (p<0.1). And vice versa: the more people thought that other people’s personalities were fixed, the lower the probability that they would be interested in entering into a long commitment (Models 4 and 7) (p<0.1).

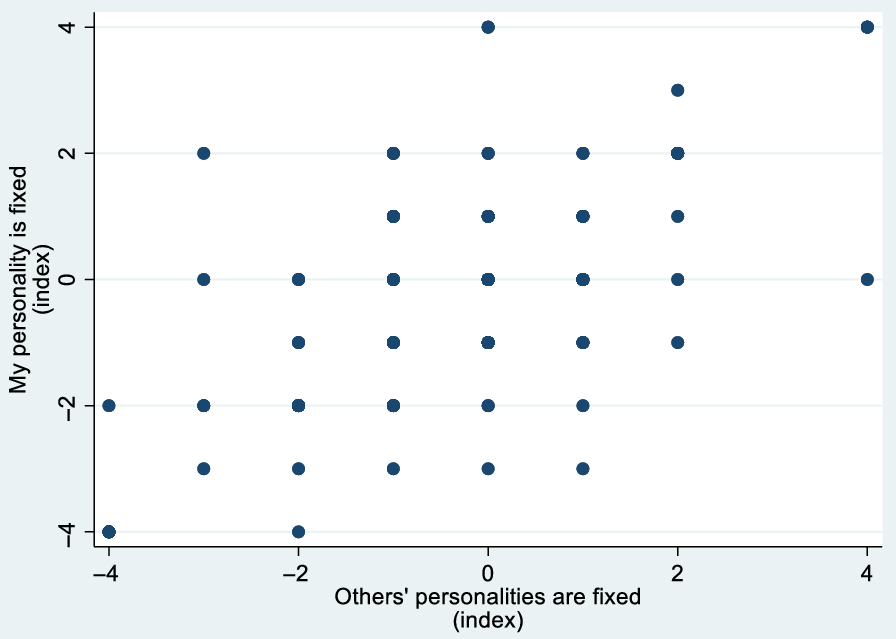

In our data, people’s beliefs about whether their own personalities were fixed were positively correlated with their perceptions of whether other people’s personalities were fixed. Recall that in only one of the experimental conditions were participants asked both about the fixity of their own personalities and about the fixity of others (the “everyone’s personalities are fixed” index captures their general beliefs about both themselves and others). In Figure 1, we present the correlations between believing that one’s personality is fixed and believing that others’ personalities are fixed for the 148 people who were asked about both aspects. The correlation coefficient is 0.6695 for these people, the average “my personality is fixed” score is −0.32 (SD = 1.76), and the average “others’ personalities are fixed” score is −0.33 (SD = 1.648) (the ranges of both indexes are −4 to 4).

FIGURE 1. Correlations between Beliefs about One’s Own Personality and Beliefs about Others’ Personalities.

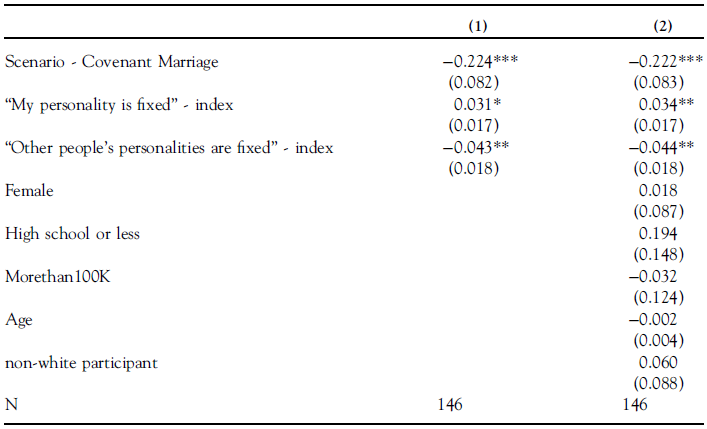

In Table 4 we present the results of logistic regression models predicting the probability of preferring a longer contractual commitment, by scenario: the “my personality is fixed” index and “others’ personalities are fixed” index for the 146 people who were asked questions about both aspects. The table reports marginal effects.

TABLE 4. Probit Models Predicting the Tendency to Make a Longer Commitment (Marginal Effects)

Marginal effects; standard errors in parentheses.

* p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

In both models we see that when both the effects of perceptions about participants’ own personalities and the effects of participants’ perceptions about others’ personalities are estimated simultaneously, the effects reported in Table 3 remain similar in magnitude and statistical significance: whereas believing that one’s own personality is fixed increases the probability of making a long-term contractual commitment, believing that others’ personalities are fixed decreases the probability of making a long-term commitment.

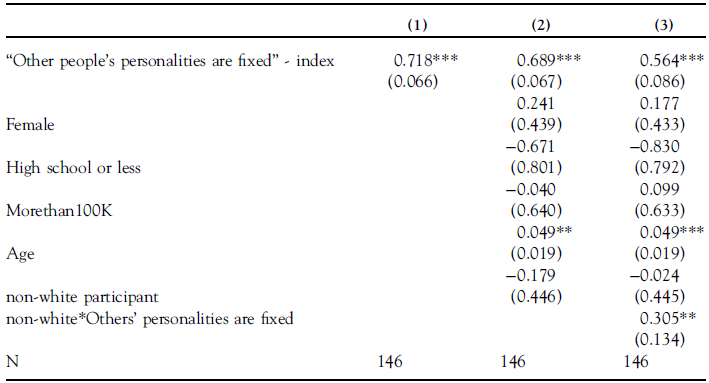

Finally, to better understand whether and how people vary in their perceptions of the fixity of their personalities, we report in Table 5 the results of OLS regression models predicting participants’ “my personality is fixed” indexes by their “others’ personalities are fixed” indexes and the demographic characteristics for the 146 participants who were asked questions about both aspects.

TABLE 5. OLS Regression Models Predicting Participants’ Entity Indexes (“my personality is fixed”)

Marginal effects; standard errors in parentheses.

* p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

In all three models, participants’ “my personality is fixed” indexes and their “others’ personalities are fixed” indexes are positively correlated (p<0.01). Models 2 and 3 show that older participants tend to have a higher “my personality is fixed” score (p<0.01). In other words, older participants tend to view their personalities as less malleable compared to younger participants. Another, final impotrant finding is, the significant “non-white” “others’ personalities are fixed” interaction which suggests that whereas for all the participants “my personality is fixed” indexes and their “others’ personalities are fixed” indexes are positively correlated, effects are greater for non-white participants (p<0.05). In other words, the positive correlation between one’s own fixity index and her perceptions of the fixity of others’ personalities is greater for non-white participants. All other demographic characteristics (as well as interactions between them and the “my personality is fixed” index) are statistically nonsignificant.

IV. DISCUSSION

The results of our experiment highlight the importance of distinguishing between perceptions of the malleability of people’s own personalities and perceptions of malleability of other people’s personalities in the context of the tendency to make long-term contractual commitments. We show that people tend to vary in their willingness to make such commitments: the more people believe that their own personalities are fixed, the more they tend to make long-term contractual commitments. The tendency to commit is also affected by people’s perceptions of the fixity of other people’s personalities: the more they believe that other people’s personalities are malleable, the more they wish to engage in long-term commitments with them. Naturally, perceptions of the fixity of oneself are correlated with perceptions of the fixity of others’ personalities. Yet, we find that net of this positive correlation, older people tend to perceive their personalities as more fixed compared to younger people. Finally, we find that the positive correlation between perceptions of oneself and others are greater for non-white participants. We also find greater tendency to commit to longer noncompete employment contracts compared to covenant-marriage-like contracts, but this tendency might be specific to our concrete scenarios.

Our study has some limitations. Most notably, because we wish to distinguish between perceptions of one’s self and of others, and because it is hard to replicate a long-term contractual commitment in the lab, we use a survey experiment that involves scenarios, rather than observational data regarding people’s actual experiences or an experiment that involves monetary incentives. Thus, it is hard for us to know whether in reality people’s behavior corresponds to what they reported they would do. Relatedly, because we ask people about their implicit views (instead of manipulating these views), it is impossible for us to show causality. Yet, the correlations we observe nonetheless shed light on people’s motivations when making long-term contractual commitments.

Naturally, marriage and employment contexts vary significantly regarding the motivations that lead people to make longer contractual commitments. We therefore do not intend to imply that the motivations of parties in the two contexts are similar. We do argue and show that net of the other factors, the people who view others’ personalities as more malleable and theirs as more fixed are the ones who tend to make longer contractual commitments. And vice versa: the people who view others’ personalities as more fixed and theirs as more malleable are the ones who are reluctant about these types of contracts and thus tend to make shorter contractual commitments.

The differences observed by age and race suggest that older people—who tend to view their personalities as more fixed—would be more interested in entering into longer contractual commitments. Additionally, because the correlation between perceptions of one’s self and that of others was stronger for non-white participants in our study, it follows that their perceptions of the malleability of their own personalities would be associated less with their tendency to make long-term contractual commitments compared to white participants.

* * *

Our study contributes to the social psychology literature on perceptions of malleability by distinguishing between the effects of perceptions of self and those of perceptions of others and by showing that although they tend to be correlated, differences between them generate differences in the tendency of people to make long-term contractual commitments. It may also offer pertinent, albeit somewhat speculative, lessons for liberal contract law and theory.

Liberal accounts of contract celebrate the function of contract in empowering people by facilitating their ability to legitimately enlist the reliable collaboration of others in their projects. As Charles Fried famously argued, “In order that I be as free as possible, that my will have the greatest range consistent with the similar will of others, it is necessary that there be a way in which I may commit myself. [Therefore, t]he restrictions involved in promising are restrictions undertaken just in order to increase one’s options in the long run, and thus are perfectly consistent with the principle of autonomy” (Fried Reference Fried1981, 13–14). This proposition may imply that since people are planning agents, the greater law’s facilitation of their ability to reliably commit, the more it aligns with the liberal commitment to enhance individual autonomy.

But this conclusion is too fast. While the normative power to make binding commitment empowers people, autonomy also requires that the authority of the current self over her future self must not be boundless. After all, our self-determination requires both the power to write and the power to rewrite the story of our lives. This is why one of us recently argued that a genuinely liberal contract law, beyond enabling us to make credible commitments, should always be alert to its potentially detrimental implications for the autonomy of the parties’ future selves. This prescription regarding the self-determination of the future self requires contract law to carefully define the scope of the obligations it enforces and to circumscribe the implications of people’s contractual commitments (Dagan and Heller Reference Dagan, Heller, Dagan and Zipursky2020).

More specifically, insofar as general contract law is concerned, this maxim vindicates the common law’s traditional strong preference for monetary recovery over specific performance (Dagan and Heller Reference Dagan and Heller2022); it also explains why where a contract’s basic assumption fails, the doctrines of mutual mistake, impossibility, impracticability, and frustration render it voidable or dischargeable (Dagan and Somech Reference Dagan and Somech2021). But the sharpest implications of the liberal prescription regarding the future self come up in the context of long-term commitments that implicate a promisor’s person, such as co-ownership of land, employment, and marriage. With both co-ownership and employment, law limits the enforceability of long-term tie-ins: the former invalidates or renders voidable agreements to restrain alienation that exceed a certain number of years (Dagan and Heller Reference Dagan and Heller2001, 616, 618); the latter conditions enforcement of noncompetes by examining their reasonableness in terms of occupational, geographic, and temporal scope (Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 188 cmt. d). The position of liberal law regarding marriage is even sharper: liberal law carefully delimits the spousal agreements it sanctions so as to ensure that it is not used to undermine a spouse’s ability to write one’s life story anew; it does not support a marriage in which no divorce is permitted or practically available (Dagan Reference Dagan, Psarras and Steel2022).

Our findings may suggest that people’s tendencies to make long-term contractual commitments largely align with this refined account of the implications of autonomy to contract. When thinking about the performance of others, people appreciate the service that contract provides in terms of assurance as per the contingency of changes in these others’ future selves. But at the same time, they are acutely aware that contract is a two-way street. Therefore, people are careful not to overly constrain themselves, a care that increases with their perception of the malleability of their own self. This care is of course what matters most to the law—and specifically to liberal law—which must approach this dilemma “behind the veil of ignorance” and adhere to the “priority of liberty” (Rawls Reference Rawls1971). This means that liberal law should apply the cautious attitude people adopt when thinking about the implications of long-term commitments on themselves and that it should follow the guide of those who indeed appreciate the priority of liberty.

* * *

These contributions to the social psychology literature and to the liberal theory of contract demonstrate—or at least so we hope—the significance of investigating the connection between people’s perceptions of the malleability of their and others’ personalities and their willingness to engage in long-term contractual commitments. But we also think that this study is only the first step in this pursuit. Indeed, some of its findings, which do not yield clear conclusions, raise intriguing issues that we hope will be studied in future research.

One such topic, which is closely connected to the liberal theory of contract, relates to the greater tendency we found to commit to longer “noncompete” employment contracts compared to the tendency to commit to a time-limited waiting period before divorce under the covenant-marriage-like scenario. As noted, this tendency might be specific to our concrete scenarios. But it does not seem coincidental; quite the contrary. Recall that liberal contract theory is not troubled by all encumbrances of a person’s future self, but rather focuses on those that might impinge on her ability to govern herself. This position implies a qualitative distinction between economic obligations and personal ones, and may suggest a further differentiation among the latter obligations in line with the degree to which they implicate the person of the future self. Our tentative finding regarding the difference between the two types of long-term contractual commitments studied in our experiment may be suggestive here, and further studies may enrich our understanding of this important dimension.

Another, maybe even more expansive, research agenda that this study hopefully opens up relates to the causes and implications of people’s tendency to view their personalities (and others’) as more or less malleable compared to others’. Thus, it is surely unsurprising to see, as our study demonstrates, that older people tend to perceive their personalities as more fixed than younger ones do. But there is no reason to think that this is the only relevant variable. Moreover, there may well be additional sociodemographic factors that we do not fully capture in our study that may be relevant here. Similarly, it may be interesting to examine how prior experience in long-term (successful and less successful) contractual commitments affects perceptions of the malleability of one’s own and others’ personalities, and as a result the willingness to engage in other long-term contracts. Finally, our results call for a more thorough examination of the demographic characteristics and life experiences of the group of people who view their own personality as relatively fixed but others’ as relatively malleable.

Turning from causes to implications, we assume that because people’s views as to the malleability of their and others’ personalities affect their tendency to engage in long-term contractual commitments, they may also affect their respective bargaining powers in these contractual contexts. If this is indeed the case, it may be important to study this implication in more detail and examine whether it further reinforces the causes mentioned in the previous paragraph. In this context our finding that the correlation between perceptions of one’s self and of others’ selves was stronger for nonwhite participants than for white participants may also be of some significance.