Mercy is exercised by someone who has the effective authority to impose some burden or suffering, and the discretion to vary or even to remit that burden or suffering. (Duff Reference Duff2006, 363–64)

INTRODUCTION

Mercy is inherently intertwined with power for, in the absence of power, mercy cannot be granted. Spanning eras of human history, as well as nations and cultures across the world, the authority to grant clemency—the legal prerogative to order mercy—has consistently belonged to the most powerful members of society (Hay Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975; Martin Reference Martin1983; Ruckman Reference Ruckman1997; Morison Reference Morison2005; Foucault Reference Foucault2012). But clemency has not merely been a benevolent discretionary right of the powerful. Prominent theoretical discussions emphasize that, historically, clemency has served a broader societal purpose. Mercy has operated alongside punishment to maintain and reinforce existing social hierarchies and has been an essential component of social control (Hay Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975; Garland Reference Garland2010; Foucault Reference Foucault2012). However, these theoretical explanations do not offer an account of this mercy in the present, leaving the role of modern clemency unclear.

In the United States, the legal authority to grant mercy is termed “executive clemency.” This power belongs to the president for persons indicted by the federal government and, typically, to state governors for those charged with state crimes (Martin Reference Martin1983; Love Reference Love2010). The current use of executive clemency has been largely neglected empirically, with a few studies highlighting its declining use over time (see, for example, Ruckman Reference Ruckman1997; Moore Reference Moore2001; Love Reference Love2010; Seeds Reference Seeds2019; Horowitz Reference Horowitz, Pamela, Beth and Faye2020). Interestingly, the discretionary power of executive clemency has remained nearly unchanged since the founding of the United States, even while other forms of criminal justice discretion have been curtailed (Love Reference Love2010). The proliferation of a series of law and policy changes that largely limited the discretion of legal actors across the country are hallmarks of the “punitive turn.” Three-strike laws, mandatory minimum sentences, and sentencing guidelines all reduced judicial discretion. The cumulative effect of these and similar modifications to penal policies was a tremendous and unprecedented growth in the prison population. Imprisonment rates in the United States grew and surpassed those of any other nation as well as at any other time in history (National Research Council 2014). Although, in the last decade, prison populations have slowly begun to decline, US imprisonment rates remain historically high (Minton, Beatty, and Zeng Reference Minton, Beatty and Zeng2019).Footnote 1

In the context of unprecedented punitiveness and clemency’s steep decline, we know very little about its current operations, especially in state systems, a gap that this study addresses. Using intensive field methods, this research asks several interrelated questions: how do these rare but persistent clemency processes currently operate; what are the forms of behavior that clemency officials seek to encourage in hearing, granting, and denying clemency requests; and, more broadly, what might modern iterations of mercy reveal or communicate about power and social control and to whom? I investigate these questions through an in-depth analysis of one form of executive clemency in four sites. While part of a larger project, the present analysis primarily draws on rich qualitative data from clemency hearings.

As currently practiced, clemency provides a unique framework to explore social control; the process involves direct interactions between powerful state actors and marginalized citizens (who arguably hold the least amount of power in society). Empirically, my findings make a foundational contribution; I identify a set of behaviors and beliefs that state actors seek to elicit from incarcerated persons through the commutation process, both of which may serve to sustain state power and control. I also uncover two unique components of modern clemency, hearings for persons who are denied release and the subset of individuals who receive this rare form of mercy.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the sociology of mercy, punishment, and power. I extend Michel Foucault (Reference Foucault2012), Douglas Hay’s (Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975), and David Garland’s (Reference Garland2010) explanations of the historical function of mercy into the present. While modern clemency faces a different and notably smaller audience than in prior eras, my analysis reveals that state actors may seek to achieve the same ends served by clemency historically: the reification of social hierarchies and the maintenance of social control. Using the ritual of commutation processes as a medium, state actors can communicate to applicants their expectations of the narratives, behaviors, displays of remorse, and apology that they expect (Horwitz Reference Horwitz1990; Tavuchis Reference Tavuchis1991; Weisman Reference Weisman2016). Legal actors may use the perceived hope that mercy facilitates in both overt and covert efforts to manufacture compliance and generate consent from applicants, even—and in some cases especially—when denying clemency requests.

EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY IN THE PRESENT

Executive clemency is under-explored in empirical research, with federal presidential pardons and clemency from execution generating the bulk of scholarly attention to date (Brett Reference Brett1957; Wolfgang, Kelly, and Nolde Reference Wolfgang, Kelly and Nolde1962; Harrison Reference Harrison2001; Dinan Reference Dinan2003; Crouch Reference Crouch2008; Colgate Love Reference Colgate Love2010; Love Reference Love2010). The most frequent conclusion drawn by the few scholars studying executive clemency’s present use in the United States is that it has declined precipitously since the 1980s (Ruckman Reference Ruckman1997; Moore Reference Moore2001; Love Reference Love2010; Horowitz and Uggen Reference Horowitz and Uggen2018; Seeds Reference Seeds2019). While clemency’s decline is well established, accompanying explanations have been varied and speculative, generally connecting it with crime politics during the punitive era (Moore Reference Moore2001; Erler Reference Erler2007; Barkow Reference Barkow2009; Gill Reference Gill2010; Love Reference Love2010).Footnote 2

Commutations are one form of executive clemency whereby the court-imposed sentence for a conviction may be reduced. Commutation may be issued to spare a prisoner’s life, converting a death sentence into life without parole, but have the broad potential as an avenue of release for persons serving life or lengthy sentences. This is especially true for those in state, rather than federal, prisons who constitute about 87.5 percent of the US prison population (Minton, Beatty, and Zeng Reference Minton, Beatty and Zeng2019). Commutation as a possible mechanism of release from prison has received very little academic inquiry (Jacobsen and Lempert Reference Jacobsen and Bex Lempert2013; Horowitz and Uggen Reference Horowitz and Uggen2018; Seeds Reference Seeds2019).

Clemency Processes in State Systems

Commutation as a prison-release mechanism exists in most states systems, but there is wide variation in the policies, regulations, practices, and procedures that govern its use. In most states, there is an appointed board that reviews clemency applications and holds hearings, before issuing a recommendation to the governor. These boards have different names (such as “Board of Pardons,” “Clemency Board,” and so on), but, in many states, the same individuals serve on both boards of pardons and boards of parole. Further, although it is typically the governor who has the ultimate authority to grant or deny clemency, in some states, the governor is constrained if the board makes an unfavorable recommendation, whereas, in others, the governor has unfettered authority and discretion to take or ignore recommendations. However, this distinction may not be meaningful in practice. It is quite unusual for a governor to grant an act of clemency against a board’s recommendation, though it is not uncommon for a governor to deny a request despite a favorable recommendation (Martin Reference Martin1983; Barkow Reference Barkow2009; Gill Reference Gill2010).

In the four sites investigated in this study, as is typical, an incarcerated person must request and apply for clemency (with many required application materials) to be considered. If granted a hearing, the applicant must present themselves to a board. During this hearing, applicants aim to convince board members to support their plea. In the rare cases where an applicant receives support from the board, they must then wait for the governor to make the final decision, often years later.

MERCY AND POWER: THEORIZING CLEMENCY IN THE SOCIOLOGY OF PUNISHMENT

Through its very definition, mercy is integrally bound to power. While mercy can, and does exist outside of the law, it cannot exist in the absence of power. In the field of criminal law and punishment, mercy requires several additional components. As explained by Andrew Brien (Reference Brien1998), legally sanctioned mercy involves discretionary power to either refrain from imposing a penalty or to replace a punishment with one less severe. Mercy is exercised when the person holding this discretionary prerogative uses it to reduce or remit a sanction that would otherwise be imposed.

Yet prominent theoretical discussions of mercy emphasize that the exercise of clemency in criminal punishment serves a broader purpose. Mercy has not merely been a discretionary act of the powerful, reducing the severity of punishment received by subordinates. Mercy, exercised as legal clemency, has also served to maintain and reinforce existing social hierarchies and has been used as a tool of social control. Theorizations of punishment and mercy focus on the historical case of clemency being used as an expression of power (Hay Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975; Garland Reference Garland2010; Foucault Reference Foucault2012; McEvoy and Mallinder Reference McEvoy and Mallinder2012). Historically, mercy has been just as important to the maintenance of social control as the production of fear has been. Foucault (Reference Foucault2012) argues that during the era of torture and corporal penal practices, punishment was a public display, used by the powerful to instill fear and gain compliance from subordinates. But alongside public demonstrations of torture and execution, displays of mercy were equally important to demonstrating the absolute power of the sovereign. In cases where a penalty of death was ordered, the execution ritual would often begin quickly post-verdict, within hours. Yet when a pardon was issued, the order of the king’s mercy would often arrive at (what appeared to be) the very last moment. The condemned may have already been at the scaffold for all the public to see when the order of mercy arrived. Thus, the public display of impending punishment was not lost, and the total power of the sovereign—to order death and also to spare life, was exhibited and reinforced. The more excessive the punishment, the greater need for, and power to bestow, mercy (McEvoy and Mallinder Reference McEvoy and Mallinder2012).

Douglas Hay’s (Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975) examination of mercy and execution in eighteenth-century England illustrates that, in addition to the sovereign, the power of those with property, class-based personal connections, and powerful positions such as justices and legal actors were amplified and revealed by clemency requests and issuances. The discretionary nature of clemency enabled an excessively unequal distribution of resources and property to be upheld by punitive laws without an army or police department to maintain order. The occasional execution of a propertied person alongside pardons granted to impoverished individuals supported an illusion that the law was distributed fairly. Meanwhile, executions were carried out in moderation to instill fear while falling short of generating outrage and resistance.

Similarly, David Garland (Reference Garland2010) highlights the significance of mercy in establishing and maintaining power in eighteenth-century punishment. He emphasizes an additional process by which clemency facilitated governance: the spared (a point also made by Hays [Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975]). The frequent and regular use of pardons left recipients forever under the control of their benefactors. Upon the receipt of clemency, the spared were forever indebted to the persons who had saved their life. They would never be able to repay the favor they had been granted and would remain grateful for the mercy they received, reducing their likelihood of resistance. Mercy, thus, has operated alongside punishment to establish, demonstrate, and maintain power and social control.

In these historical contexts discussed above, punishment was highly visible and dramatic; public displays of physical punishment were the norm. And both Garland and Foucault agree that, as the nature of punishment changed from highly visible to hidden and from corporal and capital to surveillance and discipline, clemency no longer served its past power-maintaining functions. Foucault (Reference Foucault2012) contends that eighteenth-century reforms leading to punishment without torture required the pardon power be renounced as its continued presence would delegitimize the deterrent value of punishment. Hope for mitigation undermines the certainty of punishment, a principle upon which a new foundation of generalized punishment was formed. Similarly, Garland (Reference Garland2010) explains that in capital offenses state governors now use their clemency power only rarely—in unusual cases or if they will no longer be running for office.

Shifting Penal Practice and Control

The shift away from corporal public displays of penal power and governance was accompanied by more insidious strategies of social control in the form and nature of developing penal rituals (Garland Reference Garland1993, Reference Garland2010; Foucault Reference Foucault2012). Emergent rituals in criminal processes and procedures—like those in other aspects of the law—employ self-legitimizing practices. Thus, legal rituals are used to both gain and maintain the legitimacy of the elite, reflecting culture (Kertzer Reference Kertzer1988; Garland Reference Garland1991; Chase Reference Chase2005). Moreover, as Oscar Chase (Reference Chase2005, 116) posits, a legal ritual may “affect human belief and behavior because it enlists emotion in the service of persuasion.” Accordingly, the ritual of clemency hearings in the present, detailed later, provide a site for legitimating power, shaping attitudes and behaviors, and, relatedly, conveying hegemonic ideology.

Hegemony, a concept developed by Antonio Gramsci (Reference Gramsci1992), refers to the simultaneous use of force by the state alongside the manufacturing of consent from the powerless—an important development in the new penal order. Through the process of generating consent, the beliefs and ideas internalized by society are shaped by, and serve to benefit, the powerful, reducing resistance. Gramsci (Reference Gramsci1992) also emphasized the importance of concessions (minor sacrifices that the powerful give to their subordinates in order to maintain their general position) to the sustainment of power relations. Concessions may appease the masses, but they are never so generous as to allow for power imbalances to shift. Rather than examining how hegemonic ideologies are internalized by the powerless, this article centers on the theoretical concept of hegemony as a potential aim of the state.

Successful hegemonic projects result in the powerless internalizing the ideology of the powerful. In the case of commutation, the perception of board members that applicants view commutation as an achievable outcome makes hearings potential sites to communicate desired beliefs and behaviors. Therefore, if board members are aiming to use commutation to achieve social control, I predict they will incentivize their expectations of ideal behaviors and narratives to applicants during hearings by suggesting that complying may lead to the receipt of mercy. While some penal scholars link apology in criminal proceedings with restorative justice—where apology serves to help repair the harm caused by an offense (see, for example, Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite, von Hirsch, Julian, Anthony, Roach and Schiff2003; Rossner Reference Rossner, Liebling, Maruna and McAra2017)—and functionalist perspectives view apology in penal rituals as a mechanism by which collectively held social values are reaffirmed (see, for example, Durkheim Reference Durkheim1964; Garland Reference Garland1991; Collins Reference Collins2005), I offer an alternative interpretation. Consistent with the logic of constructed consent, the state pressures those who break the law in developed penal systems to engage in rituals and profess remedial responses that demonstrate an internalization of hegemonic values and adherence to, and acceptance of, existing penal practices (Murphy Reference Murphy2006; Weisman Reference Weisman2016). As self-interested agents of the state, legal decision makers may expect the actions and apology from the law breaker to meet conditions illustrative of internalized consent (Goffman Reference Goffman1971; Gramsci Reference Gramsci1992; Weisman Reference Weisman2016). These are likely to include an acceptance of the most severe possible outcomes from their offense, a satisfactory demonstration of remorse, and unquestioning participation in the ritual, conforming with existing norms.

In the context of commutation hearings, any contestation of the allegations made by the state or protests of potential or imposed penal decisions are obvious rejections of the hegemonic project. Therefore, should such a claim emerge during a clemency hearing, I predict immediate, harsh, chastising reactions from legal decision makers (as unsuccessfully manufactured consent is addressed through force (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1992; Weisman Reference Weisman2016; Herbert Reference Herbert2022). Additionally, as remorse is socially constructed, with convincing presentations seen to warrant mitigation, legal actors in the penal sphere are skeptical of displayed remorse. Broadly, to pursue punitive aims, state actors may seek to invalidate efforts to show remorse (Horwitz Reference Horwitz1990; Tavuchis Reference Tavuchis1991; Murphy Reference Murphy2006; Weisman Reference Weisman2016). For instance, during parole hearings, board members degrade and critique applicants (Herbert Reference Herbert2022). Therefore, during commutation hearings, I predict that applicant efforts to display remorse will be contested, subject to heavy scrutiny, and typically rejected.

The Current Study

While it is certainly the case that the nature of punishment has changed, and clemency no longer operates as it did in the past, I maintain that current scholarship overlooks clemency’s enduring importance. Life sentences have emerged as the new dominant method of harsh punishment in the United States (Ogletree and Sarat Reference Ogletree and Sarat2012; Nellis and Chung Reference Nellis and Chung2013; Kazemaian and Travis Reference Kazemaian and Travis2015; Smit and Appleton Reference Smit and Appleton2016; Nellis Reference Nellis2017), eclipsing the comparably tiny population of persons facing execution (Garland Reference Garland1993, Reference Garland2010; Girling Reference Girling2016; Garrett, Jakubow, and Desai Reference Garrett, Jakubow and Desai2017; Widgery Reference Widgery2019).

With capital punishment increasingly rare, clemency from execution has declined in frequency and significance. However, commutation release, though rare, has remained in place across the country. In the present penal context, sentence commutation—the only avenue of release for thousands of people—is of increased significance. Its potential to alleviate severe punishment with mercy gives clemency decision makers considerable power. Although those imprisoned in state facilities constitute the vast majority of the prison population (Minton, Beatty, and Zeng Reference Minton, Beatty and Zeng2019), state-level commutation releases have received little scholarly attention. This study helps fill this gap, exploring four state systems in depth. My analysis focuses on both describing the clemency process and investigating how state actors engage with those seeking mercy in the rituals of site-specific commutation processes and hearings, investigating the three predictions derived from the literature above.

Prediction 1: Board members will communicate their expectations of behaviors and statements to applicants during hearings and suggest that complying with these can result in a grant of mercy.

Prediction 2: Any statement made by an applicant during a hearing that contests allegations made by the state or critiques the potential consequences of these allegations will be met with an immediate, harsh, chastising response by the board.

Prediction 3: Applicant efforts to display remorse during commutation hearings will be contested and subject to heavy scrutiny by board members and typically rejected.

METHODOLOGY

Site Selection

I sought to develop a broad understanding of state-level commutation release in the United States. Thereby, I selected four states for case studies (Iowa, Louisiana, Pennsylvania,Footnote 3 and Washington) for an in-depth examination of how commutation was operating under four unique regimes. For inclusion in my analysis, I considered only states that had released at least one individual through commutation in their relatively recent history (the year 2000 and on) because to explore current clemency processes it was pertinent that the system was operating in some capacity. I aimed to identify patterns that emerged consistently in commutation hearings across a range of conditions. Therefore, my site selection considered several criteria of variation, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Selected site characteristics

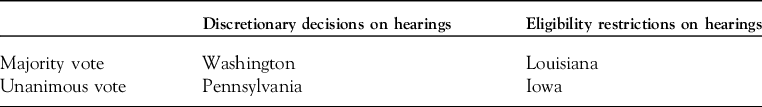

I selected states from different regions as defined by the census: Midwest, South, West, and Northeast. I used data from the 2016 Gallup poll, which assessed the conservative advantage in a state for variation in the political ideology of residents.Footnote 4 Two of my states had a relatively high conservative advantage (Iowa and Louisiana) and two had a relatively low conservative advantage (Pennsylvania and Washington). Another consideration of variation was state incarceration rates; Louisiana led the country incarcerating 776 individuals per one hundred thousand residents followed by Pennsylvania with the twenty-fourth highest rate of incarceration in the United States. Iowa ranked thirty-eighth, and Washington ranked forty-second. I also considered recent changes to release decision making—a measure developed by the Robina Institute that categorized states by changes to prison-release decision making from 2000 to 2015 (Ruhland et al. Reference Ruhland, Rhine, Robey and Kelly Lyn Mitchell2016). I included states from all three categories; Iowa was contracting, Louisiana had not changed, and both Pennsylvania and Washington were expanding. Finally, I selected sites with variation in the characteristics of their clemency boards, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2. Determinations of hearings and votes required across sites

The Hearing Process

As a form of executive clemency, commutation operates through the executive, rather than the judicial, branch. Accordingly, applicants do not have the right to due process or legal counsel, with considerable variation across my sites in the role of attorneys in hearings for those with representation. In Iowa, Louisiana, and Washington, incarcerated applicants attend their own hearings through video calls. In Iowa, victims are entitled to speak, and they speak first. However, the prisoner’s supporters cannot speak on behalf of the applicants. Iowa defendants cannot have counsel speak on their behalf or coach them during the hearing. In Louisiana, victims and supporters each get a chance to speak, as do law enforcement members. The process begins with the applicant’s interview, then their supporters, and lastly the victims and law enforcement. Louisiana clients are allowed to have counsel speak for them as supporters. In Washington, like Louisiana, supporters speak after the defendant, followed by opposition from victims or law enforcement. However, unlike Louisiana, legal counsel (if an applicant has it) plays a prominent role in the process, making opening and closing statements as well as answering questions from board members. In all three of these sites, board members routinely give explanations for their votes. Pennsylvania, however, is notably different. In Pennsylvania, the board conducts a confidential in-prison interview prior to the public hearing. During the hearing, a corrections representative employed by the Department of Corrections (the same white man throughout my data collection), speaks on the applicant’s behalf, answering board member questions if any exist. Supporters, then opposition, get the chance to speak if any are present. Finally, the board members vote formally and generally give no explanation for their votes.

Hearing Screenings

Washington and Pennsylvania screen commutation applications subjectively on the front end, and only a few commutation applicants receive an opportunity to argue their case in a hearing. In Pennsylvania, merit review hearings are held quarterly where the board members each vote on whether to grant an applicant a hearing, based on a brief case analysis provided to them by pardon board staff. A majority vote is required for a hearing to be granted, and, at the time of my data collection, there had been fewer than twenty hearings since the year 2000; only three hearings were granted in 2016. In Washington, two board members review each case and vote on whether to grant a hearing, and only one yes is required per case. In the year 2016, Washington heard sixteen commutation cases.

Iowa and Louisiana, on the other hand, screen hearings primarily through eligibility requirements. In Iowa, once denied, commutation applicants cannot reapply for ten years. It often takes years between applying and receiving a hearing, with a relatively small population sentenced to life (760 people in 2016). This lengthy waiting time between applications ensures very few hearings will occur each year. In 2016, Iowa only heard two commutation cases. In Louisiana, applicants do not get hearings until they have served ten years of their sentences (fifteen years if they have been sentenced to life without parole). Further, applicants must have been free of disciplinary reports for a period of at least twenty-four months prior to the date of the application or hearing (if a hearing is granted). They must possess a marketable job skill and must not be classified as maximum custody status at the time of their application or hearing. Louisiana heard the most cases in 2016 by far, with 178 applicants receiving a hearing in 2016.

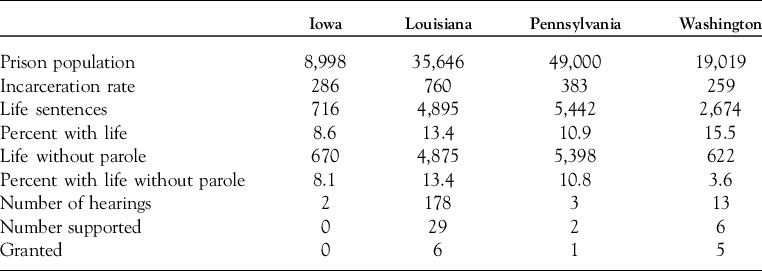

Table 3 depicts basic descriptive information on my four sites, illustrating the size of the prison population and the rate of incarceration. While Pennsylvania had the largest prison population, the rate of incarceration was highest in Louisiana. Table 3 also contains information on the number and percentage of persons with life and life without parole sentences. As is illustrated, in Iowa, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania, persons sentenced to life without parole constitute the bulk of the lifer population, but this is not the case in Washington. Table 3 also shows the rarity of hearings granted, the number supported, and the number granted.

Table 3. Commutation requests and prison populations in each site in 2016

What Constitutes a Favorable Hearing?

In both Iowa and Pennsylvania, unanimous votes are required for a hearing outcome to be considered favorable, whereas, in Washington and Louisiana, only a majority vote is needed. This requirement of undivided support in the former sites gives any particularly punitive or politically concerned board member the power to derail an otherwise successful case. Unsurprisingly, Louisiana and Washington had the highest number and percent of favorable recommendations, albeit still very small numbers (twenty-nine in Louisiana and six in Washington in 2016) relative to these states’ larger populations of lifers (4,895 in Louisiana and 2,674 in Washington in 2016).

Applications

It is difficult to make across-site comparisons of the number or portion of applications submitted or receiving hearings. In Iowa and Pennsylvania, there are often years in between the time an applicant applies and when they are granted a hearing. In Iowa, everyone sentenced to life is granted a hearing, assuming they wait ten years in between applications. In Iowa, thirty-two people applied for commutation between 2010 and 2017, yet only two had been granted a hearing. In Pennsylvania, from 2003 to 2017, there were 687 applications, and only eight of those cases received a hearing. Washington received 405 applications for commutation since 2012. Of these, seventy-eight received a hearing. In 2016, fifty-two prisoners applied for commutation. Of those, thirteen were granted a hearing. In Louisiana, 342 applications were received in 2016, with 178 hearings granted.

Board Composition

Louisiana and Pennsylvania both had a “victim representative” on their boards. Iowa’s statute requires that the board contain both a disinterested layperson and a person with a master’s degree in either social work or counseling and guidance. Washington’s board contains a Washington resident without a relationship to the criminal justice system. In Louisiana, a former judge, probation officer, child-protective services investigator, and a former warden served on the board. In Washington, two former police chiefs and a former US attorney served as board members along with a former public defender, serving as a city judge. In Iowa, the board members at the time of my research included a former judge and former correctional officer, along with a former private defense attorney.

The victim representatives in both Louisiana and Pennsylvania were among the most frequent oppositional voters in hearings. The same was true of members from specific legal career backgrounds: former judges, police chiefs, and prosecutors. Former wardens and correctional officers, in contrast, seemed more amenable to pleas for mercy, perhaps due to their proximity to those convicted of serious crimes decades after the crime occurred in their past careers.

Political Influences

Politics plays an important role in both who is on the board and how members of the board, at least those with political ambitions, vote. In Iowa, the governor appoints board members, although one board member is the attorney general, and two are also members of the parole board. In Pennsylvania, the attorney general is also a board member, the lieutenant governor serves as chairman, and the other three members are appointed by the governor with the approval of the state Senate. In both Louisiana and Washington, all board members are appointed by the governor and subject to confirmation by the state Senate.

The relationship between political ambitions and the voting decisions of the board members was most visible in my fieldwork in Pennsylvania. Unlike my other three sites, in Pennsylvania, as a rule, the Board of Pardons does not give applicants explanations for their votes. The board secretary records the vote of each board member at the end of the session’s hearing. However, a single case resulted in a brief aberration from this no-explanation practice. In the winter of 2016, I attended Pennsylvania hearings for the first time and learned about the case of William Smith.Footnote 5 William was an aging Black man and an ideal candidate for clemency. He had served nearly forty-five years in prison for a murder in which he had not pulled the trigger—an unplanned robbery in which he was the driver. He worked as the prison electrician for decades, saving the institution from two major power outages. He was so trusted that, despite his life-without-parole sentence, he received permission to travel to other states and to perform live music in the prison band he had started. He had a favorable recommendation from the prison, no disciplinary reports for decades, and strong family support.

At a 2012 hearing, William was denied clemency by a single vote. Subsequently, he had a stroke, leaving him unable to speak clearly and confined to a wheelchair, the condition he was in during the hearing I attended where he was again denied by a single vote. In response, a local reporter wrote an article singling out the individual responsible, then Attorney General Josh Shapiro.Footnote 6 Shortly thereafter, in the next election cycle, several long-standing relatively conservative incumbents were unexpectedly uprooted by their more liberal opponents. Shapiro, I learned, was aiming for a prominent political position (apparently successfully as he is now the governor). Six months later when I returned to Pennsylvania, William was having another hearing based on a motion for reconsideration made by Shapiro. Through conversation with key informants, I learned that Shapiro had recently requested and received a supporting letter from the district attorney’s office. Then, when voting on William’s request, Shapiro deviated from standard practice by making a public statement about his decision-making criteria before voting in favor of William, who finally had unanimous support. This case illustrates how political forces can drive outcomes beyond the governor; the political ambitions of a board member, a reporter, and shifting public support for prison reform changed the outcome of this case.

DATA

This article used data collected in a larger, multi-method research project, investigating clemency in the United States. It relied primarily on commutation hearing data collected (to the extent possible) from all four sites, including hearing observations, transcripts, and media files of hearings. Regarding the observations, I was able to attend hearings in Louisiana five times, observing about ten commutation hearings each trip; Washington hearings twice, with a total of nine commutation hearings observed; Pennsylvania three times,Footnote 7 with a total of seven hearing observations; and Iowa zero times as no commutation hearings occurred from 2016 to 2018 (while I was in the field). I obtained additional data through open records requests for transcripts and/or audio files of hearings from 2000 to the present (determined by data available). I received 115 transcripts from Iowa, eighty-six audio files from Louisiana, and forty-eight transcripts from Washington. Pennsylvania determined that past hearings were not open records so I could not obtain additional hearing data. However, Pennsylvania uniquely allowed me to film the hearings, so I have complete audio and video from the hearings I observed.

The data used in this article are exempt from Institutional Review Board requirements since it is public (public hearings, transcripts, and audio files obtained through open records requests). However, to protect the privacy and confidentiality of board members, victims, and applicants, I use pseudonyms throughout.

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

Being physically present was invaluable to my understanding of the commutation process. In the hearings that I attended, I began my field note process during the hearings; I took jottings focused on pertinent information that I knew would not be documented in transcripts. I took notes on the setting and structure of the hearing room; the relative positions of board members, defendant supporters, and victims in the room; before and after hearing chatter among board members and others present; the presence or absence of nonprofits or other actors; the demographics of those present; the body language and tone; and the periods of heightened emotions with thick descriptions of such moments. Once the day’s hearings were over, I took my jottings and typed them out, adding as much detail as I was able to recall to my notes along with an overall assessment of each case. I noted what seemed to me the primary cause of the hearing outcome; in many hearings that were denied, I felt there was a point when the outcome became obvious, a statement made by a victim or a shift in focus. I detailed whether I thought the applicant could have done something differently or better to potentially receive another outcome and described what seemed to have the strongest impact on each case. I paid close attention to discrepancies between what board members conveyed to applicants during hearings and what they indicated to one another. As the data presented later show, the dialogue board members had amongst themselves and casual conversations they had with me was revealing.

With hearing transcripts and field notes, my analytical procedure began with open coding, then moved into axial coding (more structured coding focused around specific categories), and, finally, ended up with selective coding once saturation was achieved (Strauss Reference Strauss1987). My coding was guided by theory, extant empirical literature, and prior quantitative findings. All qualitative data was imported into NVivo for organization and thematic coding. Given the intentional variation of my sites, the similarities I identified are striking. To understand this modern iteration of mercy, this article centers on board members’ strategic and/or seemingly intended aims, displayed during hearings. I prioritize points of congruence to provide a comprehensive explanation of how state actors across regimes use hearings as sites of targeted social control.

FINDINGS

My analysis provided support for the three predictions made above, indicating that state actors seek to use the commutation process to generate compliance and consent. Crucial to this aim is the consensus among board members that the possibility of clemency provides hope to those seeking mercy. Because of this perceived hope, commutation hearings give state actors a platform to communicate and incentivize what they want from applicants. Specifically, board members use this hope, both explicitly and implicitly in hearings, with the intent of inducing specific behaviors such as good institutional conduct and beliefs such as personal responsibility and state legitimacy. This illuminates a key function that clemency, although rarely given, may serve in modern practice. State actors use commutation as a social control strategy.

While I am not able to determine whether these efforts are successful in modifying the true behaviors and beliefs of applicants, which is beyond the scope of this study, the same is true of historical work on clemency. As Hay (Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975, 42) writes, “[w]e cannot, of course, infer gratitude from begging letters …many prosecutors, peers included, made the most of their mercy by requiring the pardoned man to sign a letter of apology and gratitude, which was printed in the county newspaper.” Instead, I focused on, and interrogated, messages conveyed by board members to applicants during hearings. My findings are organized into the following three sections: conduct and compliance; responsibility, remorse, and legitimacy; and concessions: hearings and the spared.

Conduct and Compliance

The idea that the hope of release that commutation provides is a crucial tool in inducing consent and compliance from those incarcerated and, further, that this strategy was seen by the state as necessary for the maintenance of institutional order and safety is evident in a statement made by the chair of the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons: “I think it’s critical to a moral society and a safe prison environment to provide hope for prisoners who do what is asked of them during their time behind bars. They serve as role models to younger offenders and illuminate a path toward rehabilitation and redemption.” This quote shows that Chair Clementine saw commutation as imperative for prison safety, as the hope of possible release provides incarcerated people with the motivation to comply with institutional requests and requirements of facilities that house them. Moreover, he posits, younger prison generations are impacted by attitudes and outcomes of older generations. This sentiment was echoed by Leonard, a staff member of Pennsylvania’s Board of Pardons in a comment made directly to me during an informal conversation: “If these guys can’t get out then the younger prisoners are gunna look at him and say ‘why should I follow the rules? What good did it do you?’”

Although clemency could potentially address clear miscarriages of justice, giving reprieve to those who received unwarranted punitive sentences on the front end, regardless of the sentence, board members deny applicants who do not embody the “model inmate.” As determined by the board, a “model inmate” is someone who has actively and extensively participated in available programming and subsequently encouraged others to do the same. They must follow all prison rules and display a strong work ethic regardless of the low-paying/low-skill job they are assigned. On top of facilitating the orderly operations of correctional institutions, board members seem to believe, and often state explicitly, that prison misconduct is directly related to an applicant’s risk of future recidivism. While some limited research suggests that serious, violent (Cochran et al. Reference Cochran, Mears, Bales and Stewart2014) or sexual misconduct in prison (Heil et al. Reference Heil, Harrison, English and Ahlmeyer2009) or a high frequency of prison infractions (Trulson, DeLisi, and Marquart Reference Trulson, DeLisi and Marquart2011) may predict recidivism post-release, much of the misconduct that board members cited as the basis of denying applicants is not empirically related to future reoffending (Flanagan Reference Flanagan1980; Cunningham and Sorensen Reference Cunningham and Sorensen2006).

In the absence of a relationship between adherence to prison rules and subsequent offending, the state’s interest in having well-behaved and institutionally invested people incarcerated is straightforward. Prison rules, even seemingly trivial ones, are intended to ensure orderly and efficient facility operations as do prison-work assignments like laundry and meal preparation. Prison programs may also support and reify state power but through different mechanisms. These courses keep prisoners occupied, teach them to internalize personal responsibility for their crimes and rehabilitation. This individualization may undermine the development of class consciousness (and accompanying resistance) among incarcerated individuals.

Failing to demonstrate “good institutional conduct” by following prison rules, completing assigned work, and insufficient involvement in prison programming are perceived by board members as choices. Accordingly, state actors often target institutional conduct as a key form of compliance that they seek to elicit through the possibility of “hope,” endeavoring to construct a hegemonic impetus for applicants to behave well in prison. While my data does not allow me to ascertain if an applicant adjusted their behavior because of this “hope,” it does indicate that applicants attempted to convince board members that their institutional behaviors evidenced that they had truly changed. For instance, although unsuccessful, a statement made by Mr. Dixon to convince the Washington board of his compliance and transformation through participation in institutional programming suggests he believed such behaviors might procure favorable votes: “I have taken a workbook course in chemical dependency. I have been programming since I have been here. I have got several certificates from work. I got my certificate for chemical dependency. I got my high school diploma since I have been down. I have been working. And I have learned a whole lot from being locked up.”

However, despite these efforts, discussions of institutional conduct during hearings are often deployed by board members seeking to modify behavior (when denying rather than supporting a request), and the possibility of future commutation (regardless of how unlikely) is used as motivation. In Dixon’s case, his programming was insufficient, yet while casting her negative vote, Chair Reichling explicitly offered “hope” to incentivize desired institutional behavior:

Mr. Dixon, what I would say to you is that you need to not lose hope and you need to keep looking at the opportunities that you have within the institution. Because you received a negative vote today does not mean that this fight is over for you. So, I think that you should not lose hope and you should continue and seek out any sort of opportunities that you have within the institution to demonstrate that you are in fact rehabilitated and that this is not an appropriate sentence for you.

State actors’ attempts to generate compliance through the “hope” of mercy manifests in various ways, some more coercive than others. In a Louisiana hearing that I observed, an intentionally deceptive generation of “hope” was explicit. The following is an excerpt from my fieldnotes:

The board had an executive session (which means they went off the record—muting their microphones to the prisoner) to discuss this case, but instead of leaving the room like they normally did, they discussed this case in front of me (I suspect it was because nobody else was present and they were used to me by then). They essentially concluded they did not want to release him because he had received an infraction within the last year (even though it was very close, ten days shy of a year). … They also decided they wanted to encourage him. One board member said to the others “I will vote yes, to give him hope.” They then went back on the record and the one member voted for him while the others voted against him, resulting in a denial of his request. When voting against him, on the record, the board cited his high risk to society and the DA’s [district attorney] opposition to his release. When the session was over, one of the board members turned to me and asked me how I would have voted. I said, “I think I’m a bit more sympathetic, I would have granted it.” The board member replied “yeah, he’s ready, but the reports … you can’t ignore disciplinary behavior.”

Geoff’s hearing in Iowa provides another illustration of board members’ explicit efforts to garner compliance through “hope” of commutation. At the time of his hearing, Geoff had served eighteen years of a life-without-parole sentence that he received at age nineteen. While Geoff had a stellar institutional record, he had strong victim opposition present at his hearing, and his crime was classified as a hate crime (both factors made Geoff an unlikely candidate for success). While voting to deny Geoff, a board member sought to motivate continued positive behavior by implying that it could lead to a possible positive future outcome:

I do commend you on the job that you have done. … Right now a second-degree murderer is serving more time than you have served. So, my vote today is going to be no. But I would like to encourage you to reapply. I know that’s several years away; it will be in [ten years later] that you could reapply. At that time if you continue with no reports, perhaps a different outlook from Department of Corrections, perhaps that board at that time will be able to look at you for some release. But again, I commend you on the job you have done.

Geoff’s case showcases that, even when an applicant is unlikely to receive mercy, the state continues their efforts to coerce compliance through the “hope” that clemency enables. Geoff was already compliant with institutional expectations so the board sought to sustain, rather than modify, his behaviors.

As noted earlier, ideal institutional conduct involved more than following prison rules. Compliance required heavy involvement with in-prison programs, classes, and leadership with the level of engagement elicited by the board going well beyond participating in a few courses. Individuals were expected to proactively seek out as many opportunities for self-improvement as possible and subsequently take on leadership roles, encouraging others to do the same. The specific manifestations of institutional involvement varied across my sites. In Louisiana, this was typically illustrated by earning trustee status in the prison. In Iowa, it was indicated by becoming an official prison “mentor” or leading institutional courses. In Washington, this often took the form of serving as a representative on an elected board (by votes of persons incarcerated in the facility). In Pennsylvania, this frequently meant active involvement in the Lifers group and the Pennsylvania Prison Society along with an exemplary in-prison work history. However, in all my sites, board members utilized commutation to impel applicants into immersion in institutionally sanctioned activities. This is highlighted below in an excerpt from my field notes from a hearing in Louisiana:

While I sit in the pardon hearing room waiting for the prison to be contacted through Skype so the hearings can start, I overhear a board member whisper to the DA that in her twenty-three years of incarceration, Abagail has had limited programming. When Abagail comes onto the screen all I can see is a white woman with graying brown hair that falls past her shoulders with bangs, wearing a light blue prison button-up shirt. Through the hearing I learn that Abagail was sentenced to life without parole for second degree murder. She is hearing impaired which does not work to her advantage, as the board must repeatedly ask her questions. … During the hearing the following conversation occurs regarding Abagail’s programming:

Board Member Kole: How many programs have you completed while in prison?

Abagail: Two years of Bible College, Survivors of Domestic Violence, Anger Management, Crises Intervention, Prerelease parts 1 and 2. Bible studies courses through the mail, and substance abuse. … I’ve tried to take more but it’s hard because of my hearing impairment. There are many programs that are not available because of my lifer status, and my hearing impairment makes it hard.

Board Member Kole: So, 6 programs in 23 years in prison?

In the end, despite Abagail’s understandable reason for limited programming—her hearing impairment—her clemency request was unanimously denied.

Another illustration of board members signaling the significance of programming to applicants is depicted in Justin Parker’s Washington hearing. Justin was fifty-six years old at the time of his hearing and had served thirty-one years of a fifty-life sentence for felony murder. During his hearing, Justin described what he saw as his stellar institutional behavior, indicating Justin believed his prison behavior would receive a positive response:

My last infraction was [twenty-nine years prior]. … I spend 90 percent of my time—my free time, that is—on tribal issues. I work closely with the Chaplin, the chief of the tribes. I have tried to be productive and constantly a positive role model for the younger kids coming in. … At the current time, I am active in what’s called “TOP,” Transition Offender Programs, which is mostly through the outside world right now.

However, during his hearing the board questioned Justin about his decision not to take a recommended cognitive behavioral therapy class called Thinking for a Change. The class was not offered in his facility, but he could have transferred to a different prison to take it and decided against doing so:

Chair Reichling: You don’t think you would have benefited from that programming?

Justin: No, I do not. And let me explain why I know why it wouldn’t benefit me. My brother, Chester Parker, who just got here in this institution in April, has taken that class. I have talked to many others who have taken that class. And they say, “If you want to go to sleep, bring a cup of coffee and eat popcorn, go to that class, and you can do it, because it doesn’t work.” And I asked my counselor at the time, “Can I get, you know, evidence-based, what we’re supposed to be doing, what curriculum,” and so far, DOC [Department of Corrections] has not been able to share with me any part of that.

The board unanimously voted against commutation for Justin. At the close of the hearing, Chair Reichling initiated the motion to deny the application, citing his programming decision as the paramount reason for her decision: “Most compelling to me, frankly, is the fact that he denied—he was given the opportunity to take “Thinking for a Change” and would not be transferred in order to take that because he didn’t believe he would benefit from that.”

This explicit reference to the class as the reason for denial clearly communicates behavioral expectations for the future. During my data collection, very few applicants were awarded hearings in Pennsylvania. And, unlike my other sites, Pennsylvania typically did not provide explanations for their decisions at any stage of the application or hearing process. However, the individuals who I saw attain hearings were infraction free for decades. An official from the Department of Corrections explained to me that, while the board could grant a hearing to any applicant, in practice, applicants without the support of the prison are not granted hearings. Incarcerated individuals tend to earn institutional support by engaging in the same behaviors that board members sought to generate (following prison rules, participating in the offered programing, and helping or mentoring younger prisoners). So, in Pennsylvania, rather than communicating desired conduct through discourse during hearings, these desirable behaviors were encouraged indirectly through prison administrators with the potential receipt of a hearing signifying the possibility of mercy. I return to this point in the third findings section.

Responsibility, Remorse, Legitimacy

Alongside the behaviors that board members encourage in hearings are a set of interrelated beliefs/attitudes applicants are expected to share. These include taking responsibility for their crimes, having remorse, and complete agreement with the findings and outcomes of their criminal cases. These beliefs legitimate the criminal-legal process and dissuade systemic critiques of the criminal-legal system. An unfortunate but foreseeable consequence is that applicants claiming innocence are destined for denial. Recent estimates suggest that up to 6 percent of the prison population may be factually innocent of the crimes for which they are convicted (Loeffler, Hyatt, and Ridgeway Reference Loeffler, Hyatt and Ridgeway2018), but board members do not see commutation as an appropriate mechanism for remedying such injustices.

Board members encourage applicants to internalize and engender these beliefs and attitudes using strategies that are similar to those used to shape behavior: leveraging the hope of commutation. Applicants who embody and articulate these beliefs signal that they do not, and will not, challenge the legitimacy of the legal system. Hence, adequate demonstrations of remorse and responsibility require applicants to convincingly convey the feeling that they fully deserve the punishment they received. This belief in deserved punishment reinforces the idea of the system as just. This likely explains why claims of innocence are largely dismissed—if the system was incarcerating the innocent, it implies that the system is flawed. Acknowledging such an error could undermine the legitimacy of the state, suggesting existing legal processes are not operating fairly. Similarly, board members compel applicants to accept full responsibility for their role in the offense for which they were convicted (and, occasionally, for offenses for which they were not convicted). Applicants attempting to communicate mitigating circumstances in a manner acceptable to the board are typically unsuccessful.

While most applicants do admit their guilt and express remorse, these accounts are rarely considered satisfactory. For instance, Susan Frost’s crime occurred when she got into an altercation with a friend’s landlord after drinking. According to her testimony, she hit the landlord in the head with a tool after she saw him grab a wrench. Her claims of self-defense, however, were dismissed because, after consuming more alcohol, she later went back and burned down the residence to destroy the evidence. She was fifty-three and had served over twenty-five years of her life-without-parole sentence when she came before the Iowa board. Susan admitted to killing the victim and setting fire to his house. When asked why she deserved a positive recommendation she answered:

Susan: Because I feel I’m not the same person that I was twenty-six years ago. And I realize the seriousness of my crime, which I am so sorry for—

But before she could finish her sentence, she was interrupted by Board Member Robertson

Board Member Robertson: You know we hear that a lot, that we’re sorry, that we’re not the same person …

At the close of her hearing, Board Member Chris gave the following rationale when explaining his negative vote:

Ms. Frost, my impression of you is that you had difficulty acknowledging the extent of the altercation. You accepted little responsibility for the offense. You basically blamed others for your conviction.

Board members’ conclusions about inadequate responsibility/remorse emerged in many cases and contexts, some beyond the discourse of hearings. As described in an excerpt from my fieldnotes, recorded immediately after attending the Pennsylvania hearing in which he was denied, Reginald’s story showcases a situation in which the applicant’s responsibility was determined insufficient for reasons omitted in his hearing:

Reginald had been in prison for 39.5 years, sentenced to life without parole for murder. After the victim showed up at his home, striking him, Reginald went inside, got a gun, and shot the victim. During his incarceration Reginald earned an AA in business, many certificates of appreciation, and completed many treatment programs. He had full institutional support and several people spoke in his favor at his hearing, including the two sisters of Reginald’s victim. These victims had gone through restorative reconciliation and begged for the board to release Reginald, explaining that society would be a better place. So, when he was denied by two votes, I was shocked, as was the rest of the room. After the hearing I spoke with two informants in the Board of Pardons seeking to understand the denial and learned it was due to a denied appeal. During the private in-prison interview with Reginald, the board focused on a particular unsuccessful appeal in which Reginald pled self-defense by claiming he saw the victim pull a gun before shooting. A gun was never recovered, and although a witness came forward late, stating he had seen the victim pull something metal from his vehicle, this testimony was never allowed into evidence. Reginald lost this appeal, which is why he was still in prison seeking commutation release. But the fact that Reginald had tried to argue “self-defense” indicated to two board members he had not taken responsibility.

Reginald’s case exposes an additional mechanism by which state agents may use commutation to reify state power. By denying Reginald due to his appeal, potential applicants may be dissuaded from appealing their own sentences, which could reduce the burden on the state court system (obligated to respond to legal challenges) and, more significantly, ensures an ordered sentence will not be overturned.

As noted above, only very rarely do applicants convincingly demonstrate responsibility and remorse. Shelby was able to achieve this unusual accomplishment. Shelby had served twenty-six years of a hundred-year sentence in Iowa for murder and kidnapping. A crime in which she aided and abetted her abusive male partner. During her hearing, Shelby explained that, while she initially felt her sentence was unjust, she had since realized she was just as guilty as her ex-partner:

When I was told to hit Jessie Webster with that candle. I didn’t want to do that, I didn’t know either one of the victims at all period, that was the first day I ever laid eye on either one of them. For many years I did not take that responsibility. I felt I was innocent. I was told whatever I was supposed to do. I felt I was not guilty, but then as the years went by, I was blaming everybody else but myself, and my part in this crime is my cowardness because I felt I should of done more to try to help the situation then to stand back and watch it all happen. I really feel guilty and I feel that I deserve prison time. I felt I’m just as guilty because I was too scared to do anything else.

In Shelby’s statement, she first acknowledged that she had initially externalized blame but then realized she was “just as guilty” and emphasized that she deserved prison, convincing the board to vote favorably. A contrasting Iowa example shows the reverse, a remarkably failed demonstration of responsibility, along with the strong negative reaction that it provoked. Jordan had served twenty-six years of a life without parole sentence received at age twenty-one. He was involved in a planned burglary resulting in an unplanned murder. One of Jordan’s codefendants received a shorter sentence in a plea deal, and a second codefendant was acquitted. Jordan did not participate in the murder and thereby saw himself as less culpable and his sentence as unfair, a feeling exacerbated by being penalized more harshly than his codefendants. This stance did not serve him well:

I totally agreed with what you said. I was a twenty-one-year immature child who got involved with something he shouldn’t have. I tried stopping what happened, unfortunately I couldn’t, and the man died. Now, I’m the one. … I’m the only one paying the price for that, even though the other two, one got a plea bargain, the other one got found not guilty, the one who actually committed the murder got found not guilty.

Jordan’s request for commutation was unanimously denied, and, in accordance with Iowa policy, he must wait ten years before reapplying. This quote from Board Member Chris communicates how detrimental Jordan’s lack of responsibility was to this outcome:

Mr. Arnold, I came to this hearing with a leaning toward voting affirmative for you. I have to tell you now, it’s completely turned off by your apparent demeanor when you started the interview. Then as you continued the interview it’s been more of a blame of other folks and what bothers me most of all, I guess, is as you keep talking about how you were not involved and you were not this and not that the fact that you did not report the crime after you’ve gotten away from the individual from the place, and as a result this individual ended up spending something like about five hours bleeding out and dying. And so, I cannot favorably vote for a recommendation of commutation. My answer is “No.”

Applicants conveying their responsibility and remorse in ways deemed appropriate by the board are the exception. As this harsh denial exemplifies, board members respond to critiques by specifying the perspective they expect applicants to hold and articulate. The board made it clear to Jordan exactly how he should have been referencing his crime and conduct: by consenting to the consequences imposed by the state (that he deserved the punishment he received and was responsible for the death for which he was convicted). This assertion during Jordan’s denial displays the state’s incredible power, while conveying the perspective that Jordan is expected to present going forward. Through such unsuccessful hearings, the state aims to construct those who remain under its control into subjects that uphold—rather than question—the state’s ultimate authority. Correspondingly, the beliefs and attitudes that the state seeks to contrive are epitomized by applicants in rare, successful hearings. Dean, a black man serving a life-without-parole sentence for a third strike robbery in Washington illustrates one such extraordinary success. Dean’s approach of professing (rather than questioning) the authority and legitimacy of the state exemplified a narrative of responsibility viewed as adequate by the board:

You know, that lifestyle I once embraced is nothing. I’m not that same worthless person. My heart has changed, and I’m armed with the self-respect and also the utmost respect for other people and also the rule of law. I have come to a point in my transition when I get upset when I see crimes going unreported. That’s when I knew my heart has changed.

Board members rarely find an applicant’s discourse adequate, so the dialogue from those who accomplish this is illuminating. Walter’s unusual (successful) Louisiana hearing provides a final example. Walter was an elderly black man who had served twenty-nine years of a life-without-parole sentence for killing his mother-in-law. Walter had victim support (a rarity, especially in Louisiana) from the granddaughter of the victim, and no victim opposition. Walter had never received an infraction in prison. At the close of his hearing, he made the following statement:

Thank you for the hearing, the opportunity to speak. Even as I ask you for a pardon, I am unforgiven in my soul. I will never be … I regret my actions always. Twenty-nine years ago, I committed the most terrible sin, I killed a person who showed me love and kindness. I was married to the love of my life, living the dream, for twenty-eight years. For the twenty-nine years since I have also shown repentance. I have avoided conflicts; twenty-nine years I have shown I can stay out of trouble. In short … I will face eternal horror, eternal shame for what I’ve done. I spent twenty-nine years free, then as a prison inmate, twenty-nine more years, I’m almost sixty-seven years old. I face health, illnesses, infirmary, old age. … I humbly ask for the opportunity to live my remaining years outside of prison.

The board did vote in support of Walter’s commutation, though it should be noted that their vote included the caveat of a parole eligibility date at age seventy-two. Given his ailing health, Walter may not make it to this date, but, unlike most of those sentenced to life without parole, this decision has given him a chance at making it out of prison alive.

Concessions: Hearings and the Spared

Hearings and Audiences

In Pennsylvania and Washington, unlike Louisiana and Iowa, only a small fraction of those that apply for commutation are granted hearings. Those who receive them are typically the “model prisoners” described earlier. However, hearings are periodically given to applicants who have very little chance of success due to circumstances outside of their current control (strong victim opposition or an especially notorious crime). Victim opposition may not be apparent to the board until a hearing is granted, which explains how these cases get through screening. But this is not the case for crimes of conviction seen as particularly egregious. In such cases, these hearings may represent a targeted strategy to provide applicants “hope” of receiving mercy, motivating continued compliance from individuals who display the state’s ideal behaviors and attitudes.

While incarcerated persons seeking mercy are the primary audience, granting hearings to individuals with strong victim opposition or those convicted of especially heinous crimes may also provide a platform for the state to communicate with a broader audience. In such hearings, the state may communicate values and social control (or at least state actors may consider how their decisions could garner public and media attention). The denial of cases with victim opposition and/or particularly heinous crimes are most indicative of such broader potential public considerations. Victims of crime, especially punitive crime victims, have gained a tremendous amount of political power in recent decades due to their ability to garner sympathetic public attention (Garland Reference Garland1993; Simon Reference Simon2007; Page Reference Page2011). Victims that attend and oppose a commutation hearing believe that their wishes and interests are being taken seriously by the state, yet real services that may help them or remedies for the socioeconomic disparities that they often share with defendants—the very structural conditions that correlate not only with crime but also with victimization—are ignored through this individualized and punitive focus. At the same time, cases with vocal victim opposition and cases of particularly unsettling crimes or persons with extensive criminal records are the most likely to gain public attention should mercy be granted. These types of cases have the potential to be used strategically by political interest groups for political gain and, accordingly, are not granted mercy.

The occasional, but extremely rare, release of individuals through commutation in all four of my sites and the granting of hearings in Washington and Pennsylvania to applicants whose crime of conviction hinders their likelihood of release, but who otherwise embody the ideal applicant, represent modern iterations of the minor “concessions” defined by Gramsci (Reference Gramsci1992). In places where commutation is so rarely granted, a mere hearing may be sufficient to give a person hope. In holding the occasional hearing for well-behaved applicants, all the state gives up is a small amount of time (typically, each hearing lasts between twenty minutes to 2.5 hours), but these hearings do nothing to shift the imbalance of power between the board and the applicant. It is unclear the extent to which this “concession” strategy is effective at generating hope among applicants. However, my data suggests that state actors may be using these hearings as a hegemonic tool—to generate compliance and consent through this mechanism.

Successful Outcomes

In a similar vein, releasing only a small fraction of persons through commutation in no way diminishes state power. If the state is relying on the “hope” that commutation provides to modify the behaviors and beliefs of persons in prison, then the state ought to grant occasional clemency releases for these same reasons. For commutation to serve as a hegemonic strategy to generate hope of release, it follows that release should be granted, even if only rarely. If no cases are successful, then board member’s may expect that their instructing applicants to “take responsibility for their crimes” or “improve their behavior in prison” may carry little weight over time. Therefore, persons released through commutation may also be “concessions,” facilitating the credibility of hope of release through commutation as a strategy of social control by agents of the state.

Furthermore, the small and unique population released through commutation may have broader importance, with these individuals representing a modern adaptation of the “spared.” Historically, those granted mercy played a role in ensuring the continued power of their benefactors. Upon the receipt of clemency, the spared would be forever under the control of the persons who spared their life, unable to repay the favor they had been given, which reduced their likelihood of resistance (Hay Reference Hay, Peter Linebaugh, Rule, Winslow and Hay1975; Garland Reference Garland2010). The same is true of those released through commutation in the modern era. These individuals typically remain on lifetime supervision post-release, keeping them literally under the control of those who granted their limited freedoms. Moreover, the state can (and does) use its power to ensure that this small population is comprised of only those who appear to have internalized personal responsibility, remorse, and view the state as legitimate.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While this research provides greater depth and insight to an understudied arena, its limitations should be noted. First, I examine only four states. Although they were selected for variation, future scholarship should explore if these findings are true of the commutation process in other states. Another limitation, stemming from the nature of the hearing data, is that this analysis focuses on state agents rather than applicants. This study cannot assess if consent and compliance are internalized and adopted or resisted by those seeking mercy. Such research is difficult. Incarcerated people are a vulnerable population. Both the review boards and state the corrections departments for each human subject must approve such research, and access must be granted by the prison. When incarcerated people are seeking clemency, these questions might be especially difficult to ask. Nevertheless, future research should investigate this process from the perspective of applicants.

Another important area for future scholarship is analyzing the content of commutation applications, which could provide a more robust description of the clemency process from beginning to end. In addition to impacting outcomes, these documents may be analyzed for other content. Austin Sarat (Reference Sarat2008), for instance, found that death penalty clemency petitions provided applicants with a medium to document the injustices they had had experienced and express their remorse. A final suggested area for future inquiry is a systematic investigation of the race, gender, and class of applicants and board members in shaping the hearing process. Given existing literature on in-group advantage in recognizing emotion (Elfenbein and Ambady Reference Elfenbein and Ambady2002; Halberstadt et al. Reference Halberstadt, Cooke, Garner, Hughes, Oertwig and Neupert2020), it seems plausible that board members are less likely to consider demonstrations of remorse acceptable when they are made by members of racial groups that differ from their own. The hearings I attended, particularly in Louisiana where the video quality was often poor, indicated that board members’ ability to assess remorse may be impacted by such applicant characteristics.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In analyzing the hearings of commutation applicants across four distinct sites, I developed a partial explanation of how clemency operates in its present form across the country, despite its rarity. The findings of my analysis provide support for all three predictions that I derived from theorizing clemency and social control in modern penal practice.

Prediction 1: Board members will communicate their expectations of behaviors and statements to applicants during hearings and suggest that complying with these can result in a grant of mercy.

My first prediction was heavily supported by results in my findings on conduct and compliance. Not only did the board members explicitly communicate the institutional behaviors they were hoping to elicit, but they also overtly and covertly drew upon the possible hope of commutation release to encourage these aims. My findings section on responsibility, remorse, and legitimacy also supports this first prediction, evidenced by the instructions that board members gave applicants on the need to take responsibility or adequately demonstrate remorse.

Prediction 2: Any statement made by an applicant during a hearing that contests allegations made by the state or critiques the potential consequences of these allegations will be met with an immediate, harsh, chastising response by the board.

Prediction 3: Applicant efforts to display remorse during commutation hearings will be contested and subject to heavy scrutiny by board members, and typically rejected.

The second and third predictions were largely supported by the findings section on responsibility, remorse, and legitimacy. Any applicant statement that could be interpreted as questioning the legitimacy of the sentence, reduced culpability of the defendant, or legitimacy of the state were abrasively dismissed, and the applicant was reprimanded. Similarly, the many unsuccessful attempts at displaying appropriate remorse during hearings suggest that board members approached such displays with heavy skepticism and scrutiny.

Overall, this study, has highlighted the way in which state agents deploy power through the clemency hearing process, finding that state actors use the hope of release through mercy as a potentially hegemonic strategy targeting the behaviors and professed beliefs of the incarcerated. Commutation hearings are contemporary legal rituals that perpetuate their own legitimacy and provide a site for the powerful to convey hegemonic ideologies to the powerless, shaping behaviors and attitudes (Kertzer Reference Kertzer1988; Garland Reference Garland1991; Chase Reference Chase2005). The behaviors that the state seeks to elicit from incarcerated persons include abiding by institutional rules and engaging in employment, programs, and courses, while sought attitudes include accepting personal responsibility, feeling remorse, and viewing the legal system as fair.