Introduction

In the last twenty years, Pakistan’s Supreme Court has brushed aside a history of judicial caution, overruling and undermining elected and unelected regimes and claiming a central role in the policy-making processes of the state. This transformation of the court’s role within Pakistan’s political order is, at least partially, a product of the judges’ espousal of a populist mission as judges claimed to represent the interests of the people against civilian and military political elites and adapted the language and procedures of the court to the demands of this mission. Populist leaders are conventionally popular outsiders to the state elite, challenging and disrupting the political status quo. How can unelected judges, who are lifetime appointees of a state institution, become populists? In this article, I study the transformation of the Pakistani Supreme Court to address this puzzle. As I show in this article, populist judges bypass legal and procedural rules and constraints, seek a more direct, unmediated relationship with the public both on and off the bench, and claim to represent the public better than political elites. The adoption of this populist repertoire is a product of a shift in role conception as judges assume the role of being representatives of the people and hold other branches of government accountable to their interpretation of the public interest.

I argue that judges may be motivated to adopt this new role conception in political systems characterized by dissonant institutionalization. By dissonant institutionalization, I mean the legal and political entrenchment of conflicting visions of authority across state institutions. In these political systems, contestation occurs between elites embedded within state institutions, competing over the organization and ideology of the state. In a dissonantly institutionalized system, contestation between competing institutions undermines the legitimacy of representative state institutions and draws the judiciary into a prominent political role as an arbiter of institutional disputes. The legitimacy crisis and judicialization of politics that emerge in a dissonantly institutionalized political system can lead to an ideational shift regarding the judiciary’s role within the political system. Judges may come to see themselves as better representatives of the public interest than other state institutions and state elites, and this will motivate them to challenge the authority and agenda of political branches. These populist judges then adapt the procedures and priorities of the judiciary to fit this new role.

In Pakistan, competing visions of the political order emerged early on, as elected civilian governments and the civil-military bureaucracy both developed different visions of authority. Contestation between parties elected to executive and legislative office and the civil-military bureaucracy led to military coups and disruptions in the development of the political branches of government. These competing visions were entrenched in Pakistan’s constitutional framework, particularly after 1985, leading to years of repeated legal and political struggles over the authority and discretion of the elected and unelected branches of government.

I trace the impact of this dissonant institutionalization, particularly after 1985, on the development of the role conception within the modern judiciary. In this system, civilian and military leaders suffered from limited legitimacy, and the judiciary arbitrated disputes between state institutions. Using archival research of newspaper articles and bar association resolutions, secondary historical sources, interviews with lawyers and judges, and even my own participant observations of bar association activity, I show how this institutionalized dissonance shaped the ideas, preferences, and discourses of the legal elites, from among which high court and Supreme Court judges emerged and with which they worked, trained, and socialized. Lawyers and judges sought to expand the political and policy-making authority of the judiciary, and reform the procedures of the judiciary, in service of this new role, which brought judges into conflict with primarily electoral, as well as military, centers of power. The judges’ ambitions were realized through the expansion of public interest litigation, a body of jurisprudence in which the Supreme Court bypassed procedural restrictions to deal with questions of significant “public importance.”

Through a study of 160 reported public interest litigation judgments of the Supreme Court, archival research of newspapers and bar association resolutions, and interviews with lawyers and retired judges and my own observations of judicial proceedings, this article examines the judicial behavior of Supreme Court judges both on and off the bench between 2005 and 2019.Footnote 1 It closely scrutinizes judicial decisions on questions of political corruption, bureaucratic appointments, and the substance of security and socioeconomic policies and describes the populist role that the court has progressively adopted within the political system, which has manifested itself in changes in the content of judicial decisions, the observance of judicial procedures, and the relationship between judges and the general public. Thus, the article sheds light on both the content of judicial populism as a novel judicial approach and role conception as well as the factors that can facilitate the rise of this distinct and highly consequential form of populism.

Can a judge be a populist?

An emerging political science literature engages with the global wave of populism seeking to explain its origins and its implications for democracy (Urbinati Reference Urbinati2015; Müller Reference Müller2016; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018). There is broad agreement on the main conceptual components of populism as a form of political discourse. Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker2017) argues that we should conceive of populism as a repertoire with the key defining element being the claim to speak and act in the name of “the people” in opposition to “the elite.” The “people” in this case are defined in opposition to economic, political, and cultural elites who are rich, powerful, well connected, institutionally empowered, and playing by different rules.Footnote 2 Brubaker expands on this conceptualization of populism by arguing that different manifestations of populism will include some or all of the following elements: (1) a claim to reassert democratic control over domains of life that are seen as having been de-democratized; (2) an assertion of the interests, rights, and will of the majority; (3) a distrust of the mediating functions of institutions, including political parties and courts; and (4) an emphasis on plain speaking over polite and inaccessible technical language. So how can judges—office holders in an unelected mediating institution who work in the language of law and legal precedent—present themselves as credible populists?

Judges are actually well positioned to claim that they speak and act in the name of the general “public” in opposition to perhaps an out-of-touch or authoritarian elite. Daniele Caramani (Reference Caramani2017) describes the similarities in the political alternatives to party-based political systems presented by populists and technocrats, including (1) a unitary, general interest of a given society, which factional partisan politicians are unable to find; (2) a leader that can be entrusted with the responsibility of realizing this common interest; and (3) the absence of institutions and procedures that constrain the leadership’s ability to realize this common interest. The judge can be the kind of leader that populists and technocrats both propose as an alternative to the party leader. The judge is a legal expert who does not belong to any political party or faction and thus does not represent any factional interest. The judge possesses a specialized body of knowledge that can be suited to the task of realizing the common interest. The Constitution, after all, is the state’s unifying charter, and the judge is the guardian and interpreter of this charter. Thus, when we consider the similarities in populist and technocratic critiques of party-based systems, and the alternatives they propose, we see how judges can actually exemplify that alternative leadership.

But the judge is still a technical expert in an unelected mediating state institution. Populist judges must therefore diverge from their traditional institutional role by altering procedures and discourses that mediate and limit the access of the public to the court. The term “judicial populism” came into popular use in India when it was used to refer to the rise of public interest litigation, where judges increasingly dispensed with procedural restrictions on public access to the high courts and Supreme Court by relaxing the rules of standing. Upendra Baxi (Reference Baxi1985, 111) describes this “judicial populism” as an “assertion of judicial power in the aid of the deprived and dispossessed” and focuses on the relaxation of procedural restrictions and an increasingly people-oriented rhetoric infused in this jurisprudence as the features of judicial populism. Anuj Bhuwania’s (Reference Bhuwania2017) less laudatory account of the expansion of public interest litigation highlights how judicial populism has operated as a counter to, and constraint on, political society and its institutions, including political parties and elected governments, and has shifted courts away from playing a counter-majoritarian role as they seek legitimation from the “people” as a whole.

Scholars of judicial populism in Pakistan similarly have labelled the more recent explosion of public interest litigation in Pakistan, particularly under Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, as judicial populism. Anil Kalhan (Reference Kalhan2013) highlights how the judiciary has assumed the role of upholding a “popular sovereignty”-based understanding of constitutionalism, in which the judiciary sees itself as directly legitimated by the people. Osama Siddique (Reference Siddique2013) explains that the “populist” attributes of the Pakistani Supreme Court under Chief Justice Chaudhry includes a rhetorical positioning of judges as superior representatives of the people compared to elected officials and an active courting of public visibility and the curation of public image both through on-bench and off-bench behavior, attributes that have been identified by Diego Arguelhes (Reference Arguelhes2017) in populist judges in Brazil as well.

Thus, what we see in this literature on public interest litigation in South Asia is an identification of features of judicial procedure and rhetoric that help us recognize a particular judge or judicial action as “populist.” Building on, and synthesizing, this rich literature, I seek to develop a general framework for understanding the phenomenon of judicial populism. Traditionally, the judge interprets, elaborates, and enforces public laws and applies those laws to facts filtered through formal adjudicative process (Scott and Sturm Reference Scott and Sturm2007). The judge reacts to factual evidence and legal argument presented through formal proof in court and defines and redresses a problem through articulation and application of an appropriate legal rule. Courts apply statutory and constitutional principles and law to disputed laws, and the actions of private and public parties, all filtered through formal processes.

The populist judge assumes a different role from the traditional role of judges, not only seeking to apply the law or to work through formal adjudicative processes but also seeking to champion the public interest and bypass formal legal language and procedures (Baxi Reference Baxi1985; Kalhan Reference Kalhan2013; M. Khan Reference Khan2014). If judicial review is traditionally understood as a tool for horizontal accountability—that is, holding the executive and legislative branches of government accountable to the law and constitution—populist courts seek to reconceptualize the role of judicial review as a tool for carrying out vertical accountability—that is, holding the executive and legislative branches of government accountable to the people. Thus, while other judges challenge or overturn actions of other branches of government on the basis of legal norms, whether they are established through constitutional articles and principles, statutory laws, procedural rules, or judicial precedent, the populist judge also overturns the actions of other branches of government on the basis of a more nebulous notion of the “public interest” as processed through the mechanics of constitutional interpretation. In this role, the Constitution is understood as representing the “will of the people.” In holding the government accountable to the Constitution, the judiciary is holding the government accountable to the people, and where the laws and procedures restrain the courts from holding the government’s conduct, law, and policies accountable to the people, the courts may amend, reinterpret, or bypass these legal constraints to realize this role. The populist judge does not only hold other institutions of government accountable to the law but also to the interest of the general public. And they adapt the institutional role and procedures of their office to accommodate their role as representatives of the public interest.

The repertoire of the populist judge includes (1) the relaxation of restrictions on the public’s ability to access their courts; (2) the restructuring of court proceedings to enable public petitioners to approach judges more directly rather than through their lawyers; (3) the invitation of media coverage of their speeches and judgments so as to speak more directly to the public; (4) the interpretation of the Constitution as the manifestation of the will of the people rather than a document organizing and distributing authority between institutions; and (5) the usage of simplified language invoking the interests of the general public rather than the esoteric vocabulary of constitutional interpretation and legal precedent. However, two questions that remain unanswered are: why would judges do this, and when would they do this?

Why judges become populists?

There is a growing literature that examines the reasons for judges to shift out of traditional roles and into new roles more directly pertaining to questions of politics and policy making. Judges around the world now routinely make important policy decisions that, only a few years ago, would have been seen as properly the purview of bureaucrats, politicians, and private actors, a phenomenon described as the judicialization of politics (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2008). Scholars studying judicial institutions have explained the judicialization of politics as a product of changing political contexts, long-term shifts in state-society relations, the institutional leadership of powerful judges, and even changes in the institutional norms of the judiciary. Scholars of the political context have focused on growing political fragmentation (including in states like India and Pakistan in the 1990s) as a driver of the judicialization of politics (M. Khan Reference Khan2014; Mate Reference Mate2014). Scholars focused on state-society relations argue that the liberalization of economies shifted the role of the state in the economy from driving and guiding the economy to regulating it, which provided motivation for courts to play an increasingly prominent role in enforcing the rules and regulations of an increasingly privatized economy (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg, Ginsburg and Chen2009). Osama Siddique (Reference Siddique, Tushnet and Khosla2015) points out the role of Chief Justice Chaudhry in driving the judicialization of politics in Pakistan after 2007.

But the judicialization of politics does not look identical across states. Courts in some jurisdictions may pursue the championing of socioeconomic rights, while courts in other jurisdictions may focus more on issues of pure politics. In some judicialized political systems, courts may seek a more dialogic relationship with the other branches, while courts in other judicialized systems may seek to displace the other branches of government. The choices that judges make in terms of the issues upon which they assert and expand their authority, the justifications they provide for their actions, the legal principles they prioritize in their jurisprudence, the precedents they seek to overturn and entrench, and the repertoire they hone for conflict with other state institutions can all vary from state to state and even judge to judge. Therefore, understanding the trajectory of the judicialization of politics in each state requires understanding the different roles that judicial institutions adopt in either pursuing or adapting to the judicialization of politics.

The expanded roles that judges play in different jurisdictions in response to the political and socioeconomic conditions facilitating a more expanded and politically engaged role for the courts, often depends on the institutional design, norms, and internal culture of the judiciary. (Clayton and Gillman Reference Clayton and Gillman1999; Hilbink Reference Hilbink2007; Kapiszewski Reference Kapiszewski, Couso, Huneeus and Sieder2010). The professional institutions, communities, and networks within which judges train, socialize, and work act as a site for preference formation, and the norms and discourses within these institutions and communities shape judges’ conception of their role within the state structure (Clayton and Gillman Reference Clayton and Gillman1999; Hilbink Reference Hilbink2007; Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg, Ginsburg and Chen2009; Mate Reference Mate2015). Javier Couso and Lisa Hilbink (Reference Couso, Hilbink, Helmke and Rios-Figueroa2011) argue that the shift in the role conception of the Chilean judiciary was a result of institutional reforms that transformed the training, socialization, and incentives of Chilean judges. Chilean judges learned to embrace a rights-protecting role, motivating them to embrace a strong form of judicial review.

In his account of the judicialization of politics in Latin America, Ezequiel Gonzales-Ocantos (Reference Gonzales-Ocantos2016) argues that the increased willingness of Latin American judiciaries to prosecute government officers for human rights violations was a product of interactions with courtroom litigants who pushed for a shift away from a positivist judicial ideology and toward a rights-protecting responsibility. Thus, understanding variation in the role conceptions of judges requires paying attention to the prevalent ideologies, norms, values, and discourses about the nature of law and the demands and expectations within the institutional networks and communities within which the judicial elite is embedded. Manoj Mate’s (Reference Mate2014) study of the rise of selective judicial activism in India emphasizes how the surrounding political and social environment and discourses of the 1990s shaped the ideational consensus regarding values and goals amongst the networks within which the judicial elite were embedded, thus shaping the values and discourses that were prevalent within the judiciary itself.

If we understand the judges’ adoption of a populist repertoire as one particular trajectory that the judicialization of politics can take, and this trajectory is a product of a shift in role conception, where judges now see themselves as representing the “public interest” and holding government accountable to this public interest rather than purely to the law and legal process, then we must pay attention to the ideational consensus within the professional networks and communities within which the judiciary is embedded to understand the emergence of norms, ideas, and discourses that would inspire such a populist judicial role conception within the judiciary and consider the reasons underlying the emergence of such norms, ideas, and discourses.

When do judges become populists?

In the broader literature on populism, populism is seen to emerge in response to crises in the legitimacy of the present political system, whether as a result of long-standing political corruption (Betz Reference Betz1994), deep inequality (de la Torre Reference De la Torre2010), uncertain democratization and democratic disenchantment (Panizza and Miorelli Reference Panizza and Miorelli2009), electoral volatility, or political polarization (Hawkins, Read, and Pauwels Reference Hawkins, Read, Pauwels, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). What this literature indicates is that populists emerge when the prevalent institutional order suffers from a lack of legitimacy, creating space and motivation for a populist outsider to disrupt the political order. However, if a lack of legitimacy in the political system provides the facilitating conditions for a populist political outsider to challenge the established order, what type of legitimacy crisis can motivate a judge—an appointed official in one of the key branches of government—to adopt a populist role repertoire—that is, to claim the mantle of the public interest and challenge politicians for not doing so themselves?

In line with Mate (Reference Mate2014), I argue that we need to consider how the broader social and political conditions and discourses of a particular period impact the norms, values, and discourses within legal and judicial networks and communities. We need to consider what kind of legitimacy challenges within the broader governing order may facilitate a populist discourse regarding the role of the judge emerging within judicial networks. Scholars have identified how the judicialization of politics can occur in response to an increasingly fragmented polity (M. Khan Reference Khan2014), but I argue that a populist approach to the judicialization of politics is not only a product of political fragmentation but also a product of an emerging aspirational norm and discourse within the elite networks within which the judiciary is embedded regarding the illegitimacy of other state institutions and the comparative representativeness of the judiciary itself.

The reasons for this systemic legitimacy deficit within these elite judicial networks may vary from system to system. In India, Mate (Reference Mate2014) considers how the broader elite agenda for economic reform and liberalization from corrupt and inefficient government and bureaucratic control led to the changing role of the judiciary in India, facilitating the rise of public interest litigation. Alternatively, the condition that I believe facilitated a similar legitimacy deficit in Pakistan was the condition of dissonant institutionalization. Dissonant institutionalization, as conceptualized by Daniel Brumberg (Reference Brumberg2001), describes the entrenchment of contradictory and competing ideologies within the state’s political and legal structure. Autonomous institutions within the political system develop contradictory visions of the polity and clash with each other in seeking to realize these visions (Shambayati Reference Shambayati, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008). This dissonant institutionalization leads to heightened tensions and raises the stakes of political conflict.

In Iran, dueling ideological legacies of Iran’s 1979 revolution were institutionalized in the constitutional system, with the post-revolution institutional structure integrating both theological and representative institutions, generating competition between post-revolutionary elites representing both the theocratic and democratic ideals of the revolution (Brumberg Reference Brumberg2001). In Turkey, Hootan Shambayati (Reference Shambayati, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008) identifies similar dueling frameworks institutionalized within the political and constitutional system prior to the rise of President Recep Erdogan in 2010, with power shared between elected civilian institutions representing popular interests and a powerful military protecting the state’s Kemalist ideology. In these systems, members of each set of institutions will seek alliances with like-minded groups in civil society as well as public support as they attempt to weaken, delegitimize, and/or capture institutions beholden to an opposing vision of authority (Shambayati Reference Shambayati, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008). Thus, political contestation does not only occur between political parties competing for electoral control of the state’s institutions but also between coalitions of aligned state institutions, politicians, and civil society members competing over the organization and ideology of the state.

Brumberg (Reference Brumberg2001) argues that dissonant institutionalization is not necessarily destabilizing but that achieving equilibrium in such a system is difficult and that competing elites will frequently try to alter the political system toward their advantage and entrench their ideas and authority across state institutions. In the competition to resolve the dissonance in their favor, competing state elites will seek to delegitimize each other. Thus, where dissonant institutionalization is formalized in the constitutional framework and embedded into mass politics, competing state elites will frequently clash over roles and authority and undermine each other. Shambayati (Reference Shambayati, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008) points out that controversies between competing state elites tend to be taken to the courts, placing the courts in a more actively political role, resolving disputes that inevitably emerge regarding the distribution of authority and power within a dissonant system.

Intra-institutional competition and the judicialization of politics may provide judges with an opportunity to challenge the established authority of the other branches of government. But, more importantly, this intra-institutional competition means that competing state institutions undermine each other’s legitimacy, leading to a legitimacy deficit for either or both sets of competing institutions. Further, as judges arbitrate the disputes between competing state institutions, they operate as outsiders to these delegitimized institutions. Thus, a sustained legitimacy crisis within the political branches produced by prolonged institutionalized dissonance, and the judicialized contestation that comes with it, may shape the ideas and discourses that develop within legal and judicial networks regarding the appropriate role for the judiciary. Lawyers and judges may see the political leadership of government as increasingly illegitimate and unrepresentative of the interests of the public and see judges who have been arbitrating political contestation as better equipped to represent and protect the public interest than the dueling state elites running the other branches of government. Hence, in this legally institutionalized dissonance, a growing normative consensus may emerge among lawyers and judges regarding the need for judges to represent the public interest and hold the other branches of government accountable to the people.

Hence, the ideas and norms underlying judicial populism can emerge over time in the context of institutionalized dissonance, and when these ideas take hold within the intellectual and professional communities within which judges work, train, and socialize, they percolate into the courts and impact judicial behavior. Judges are then motivated to disrupt the formal distribution of power and expand their jurisdiction and authority on the basis of this representative conception of their role. Thus, where there is dissonant institutionalization, judges may see themselves as outsiders to the sections of the political system suffering from a legitimacy deficit and challenge the other branches of government on this basis. This is not the same as a judiciary taking advantage of an unpopular political leader or fragmented political authority to assert its authority. The populist court is not merely expanding its authority over other branches but is seeking to compete with, and, on some issues, even supplant, the political branches as the more representative branch of government.

Therefore, I argue that, in political orders characterized by dissonant institutionalization, the contestation across political institutions, the increased judicialization of politics, and the limited legitimacy of the representative branches of government may drive a shift in the normative and ideational discourse in legal and judicial networks regarding the role of the judiciary and thus push a judge to adopt a populist role and associated repertoire. Judges who take on this role will then adjust the legal language and procedures that mediate their access to the public and limit their populist appeal and prioritize public interest over questions of jurisdiction and precedent. Dissonant institutionalization is not a necessary condition for the emergence of populist judges, nor is it inevitable in systems that are characterized by dissonant institutionalization. Dissonant institutionalization can reshape the normative and ideational discourses present within legal and judicial networks, providing the grounds for adopting a populist role conception within the judiciary, but its impact depends on how it impacts the professional networks in which the judiciary is embedded and that shape the dominant norms and values held by the judicial elite. This is the process in Pakistan that I will now discuss.

The emergence of judicial populism in Pakistan

Pakistan’s dissonant political order

In Pakistan, after independence, a powerful set of paternalistic executive institutions were established by the British Empire, while political institutions were weakly developed (Talbot Reference Talbot1998). Military officers and civil servants imbibed the colonial officials’ view that nationalist politicians and political parties were untrustworthy agitators and that politics were divisive and parochial; together, these necessitated the oversight and guidance of organized professional institutions (Shah Reference Shah2014). They sought to establish a political structure that ensured their role overseeing and guiding Pakistan’s political system. Kalhan (Reference Kalhan2013) called this the “viceregal” model as it was modeled on the colonial state and privileged centralized authority and presidential power. On the other end, several of Pakistan’s political parties sought to mobilize popular national and subnational identities and patronage networks in order to win parliamentary elections and gain control over the distribution of political resources (Talbot Reference Talbot1998). These parties favored elected parliamentary supremacy and a more decentralized and “representative” system that empowered Pakistan’s ethnically defined provinces. The result was an antagonistic relationship between Pakistan’s civil-military bureaucracy and the popular political parties. However, the relationship was rarely symmetrical as, from the start, there was a clear imbalance of power in favor of the civil-military bureaucracy, which ensured that the “viceregal” model retained primacy through most of Pakistan’s early years (Jalal Reference Jalal1990).

The differences between the political parties and the civil-military bureaucracy resulted in a series of military coups. At the end of each period of military rule, elected governments would seek to establish a democratic political order. However, even during periods of civilian rule, the military indirectly intervened in the political process on multiple occasions to ensure that civilian governments did not threaten their autonomy and interests (Shah Reference Shah2014). The military would adapt its tactics and political approach in order to entrench and extend its authority, autonomy, and influence under civilian rule, which was an iterative process that Kalhan (Reference Kalhan2013, 10) termed “transformative preservation.” Thus, Pakistan’s political history was marked by repeated disruptions in the development of its elected institutions juxtaposed against the comparative continuity in its unelected institutions, a juxtaposition that affected the strength and legitimacy of the elected governments and the perceptions within the unelected branches about their relationship with the elected branches.

Dissonance in Pakistan’s constitutional framework

In 1973, Pakistan’s first elected civilian government established the constitutional framework that has remained in place to date, albeit with periods of suspension and significant amendments along the way. The key features of the new Constitution included a democratic system of government with parliamentary supremacy, control over the unelected military, and bureaucracy placed, at least formally, firmly under elected leadership. In 1977, General Zia-ul-Haq seized power in a military coup and suspended the Constitution, only restoring it in 1985, after pushing through several constitutional amendments that decisively shifted executive power from the elected parliament to the presidency, which was Zia’s office at the time. The amendments gave the president a range of discretionary powers with respect to the federal and provincial governments, including the power to dissolve elected assemblies under Article 58(2)(b). Articles 62 and 63 gave the judiciary the power to disqualify elected representatives and electoral candidates from political office for not meeting a vague moral standard of morality and sagacity. Thus, after Zia’s amendments, Pakistan’s Constitution formalized and institutionalized, rather than resolving, the dissonance in Pakistan’s political system, not only placing executive and legislative power in the hands of an elected representative government but also giving the unelected branches significant autonomy and a role in overseeing and undermining the elected branches and protecting the unity, ideology, and security of the state.

The best term to describe the political and constitutional order that emerged in the aftermath of Zia’s regime and constitutional amendments is institutionalized dissonance. A constitutional system of divided sovereignty was established that institutionalized the dissonance between the viceregal and representative models in Pakistan’s political system. The elected parliament represented the different peoples of the country, spread across its provinces, and the unelected president, supported by the federal civil-military bureaucracy that represented the unity and ideology of the country. In this position, the president was authorized to prevent the factionalism of Pakistan’s political parties from dividing and destabilizing national unity or undermining the national ideology. This institutionalized dissonance shaped Pakistan’s constitutional and judicial politics in the coming years.

Institutionalized dissonance and political legitimacy

Political systems characterized by dissonant institutionalization embody a high level of tension within them, as they highlight a division in the ruling elites concerning the nature of the state itself. In this context of competing hegemonic elites seeking to displace each other, both sets of elites can see their legitimacy diminished with different groups in society, and the courts take on an actively political role. When General Zia was assassinated in 1988, the elected civilian government returned to Pakistan, and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) won the election and took office. Pakistan’s political parties had been decimated by Zia’s regime and its brutal repression of political activity. After years spent in the wilderness, when democratic rule resumed, these political parties were weak and had few direct connections to the voters and were dependent upon autonomous local actors, ranging from landlords and tribal leaders to clientelist exchanges amongst brokers, kin groups, and local party leaders (Mohmand Reference Mohmand2014). In this system, therefore, elite corruption, in-fighting, and governance failures plagued the political governments during the 1990s.

Zia’s constitutional arrangement was also maintained, ensuring that the unelected branches, particularly the presidency, continued to clash with the elected branches. When Benazir Bhutto’s PPP took power in 1988, it was faced with a strong military, a president who was a former bureaucrat and closely allied to the military, a federal bureaucracy that had mostly been staffed during the era of military rule, a judiciary that had mostly been appointed during military rule, and a strong parliamentary opposition comprised of mostly pro-military parties. The new elected government had few allies in the unelected sections of the political system and little space to operate. Efforts made by the government to expand civilian control over other executive institutions faced strong opposition. The presidential dissolution of elected governments became a recurring occurrence during the 1990s. Once elected, governments sought to exercise power independently and bring the unelected institutions under greater electoral control; they fell out of favor with the military and the presidency and, thanks to the president’s powers under Article 58(2)(b) of the Constitution, faced presidential dissolution.

The civilian governments tried to take more control of unelected institutions by staffing them with officers who were more partial to the civilian governments. This created considerable friction with the entrenched interests already present in the institutions, and disputes frequently arose over the appointment powers of the elected executive. Between 1991 and 1994, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and President Ishaq Khan clashed repeatedly over questions of authority, including who had the power to appoint the new chief of army staff and who had the power to remove provincial governments. Bhutto, in her second term in 1994, tried to appoint pro-PPP lawyers as judges (H. Khan Reference Khan2016). The attempts by the elected executive to build inroads into unelected institutions was a critical political flashpoint in this era. Thus, in the 1990s, the dissonance within Pakistan’s political system was mostly institutionalized, as the “viceregal” model and the “representative” models both sat uneasily within the constitutional structure, and the proponents of these competing models continued to clash over the architecture of the political system, seeking to establish and entrench the primacy of their preferred model of government.

During this era of divided sovereignty, contentious disputes regarding the dispensation of authority within the political system were repeatedly referred to the courts, which came to play a more active political role. Between 1988 and 1999, the Supreme Court had to rule four times on the constitutionality of the president’s dissolution of the elected parliament (Siddique Reference Siddique2006).Footnote 3 Similarly, appointments made by the elected government were repeatedly challenged before the courts. Thus, the fragmentation of authority across the elected and unelected branches created an outsized role for the judiciary as the venue for resolving major political disputes. The fragmentation of authority between the unelected branches and the elected branches (Newberg Reference Newberg1995), within this dissonant system, explains the judicialization of politics during this era.

This judicialization of politics, combined with the legitimacy crisis generated by this dissonance, impacted discourses and values held within judicial and legal communities regarding the role of the judiciary. The military and affiliated elites in the bureaucracy and presidency developed an “antidemocratic legitimating discourse” to justify their continued authority (Kalhan Reference Kalhan2013). The military presented itself as the guardian of the state’s unity, identity, and ideology and self-consciously presented its conception of professionalism in contrast to elected civilian politicians who they characterized as incompetent, corrupt, and beholden to factional subnational interests. Thus, the military justified the need for its continual authority and the sustained supervisory role of the unelected branches over the elected branches as necessary to prevent “corrupt self-serving” politicians from undermining the unity and Islamic ideology of the state (Rizvi Reference Rizvi2000).

The military narrative of political corruption and factionalism was seemingly corroborated by the actions of leading political parties as they adopted an approach of perpetual confrontation, always seeking to undermine and delegitimize each other based on allegations of corruption, incompetence, and anti-nationalism. Corruption became a common accusation during this era as ruling and opposition parties would routinely accuse each other of corruption, and both would face similar accusations from the military, the presidency, and the judiciary (Rizvi Reference Rizvi2000). In Transparency International’s survey of perceptions of corruption, Pakistan had the second highest perception of corruption among fifty-four countries surveyed around the world in 1996 (Talbot Reference Talbot1998). In a Gallup survey taken in 2000, 59 percent of people said that politicians were responsible for the problems faced by Pakistan (Gallup Pakistan 2011). Thus, presidential dissolutions, harsh adversarial competition between political parties, and growing concerns about political corruption helped entrench negative impressions of the political class. Thus, this era of institutionalized dissonance left the elected branches facing a significant legitimacy deficit.

At the same time, the dysfunction and illegitimacy of the elected executive did not mean that military rule had uncritical support. During Zia’s regime, his suspension of all fundamental rights, and his actions to control and weaken the judiciary, generated considerable opposition and resistance within Pakistan’s bar associations. Indeed, a generation of young lawyers became actively engaged in politics and mobilization against Zia’s military dictatorship (Dawn 1985). And when the military seized power in a military coup again in 1999, there was little appetite for extended and unfettered military rule. In 1999, in a Gallup survey conducted after Musharraf took power, a majority of respondents expressed a preference for a civilian government, and only one-third supported sustained military rule (Gallup Pakistan 1999). Within the urban centers, one of the most vocally critical segments of the regime was the legal community, to which I now turn.

Institutionalized dissonance, the legal community, and the courts

The 1973 Constitution also endowed both the Supreme Court and the provincial high courts with original jurisdiction with jurisdictional, procedural, and remedial powers devoted to the enforcement of fundamental rights and strengthened the judiciary’s power to enforce these rights by providing that laws that were inconsistent with, or made in derogation of, these fundamental rights were void (M. Khan Reference Khan2014). Article 184(3) of the Constitution also gave the Supreme Court the power to make orders on questions that the court deemed of public importance with reference to the enforcement of fundamental rights. Article 184(3) became the constitutional basis for public interest litigation in Pakistan.

In 1988, the Supreme Court made a landmark judgment that commenced the development of public interest litigation in Pakistan. In Benazir Bhutto v Federation of Pakistan, the court asserted its fundamental rights jurisdiction in order to overrule government legislation and held that access to justice is pivotal in “advancing the national hopes and aspirations of the people.”Footnote 4 Therefore, the court held that it had to show flexibility in its procedures by relaxing the requirement that the court’s original jurisdiction could only be asserted in cases brought forward by an aggrieved party. Initially, the exercise of this public interest litigation was limited (M. Khan Reference Khan2014).Footnote 5 In Pakistan, most high court judges were lawyers appointed laterally from the bar of professional lawyers, usually after fifteen to twenty years of professional practice. The high court bar was the professional network within which lawyers trained and socialized, including those who go on to become high court judges, and it is the community with which judges seek to build their reputations as judges (Kureshi Reference Kureshi2022). The values and discourse of the legal elites in these networks shape the dominant values and discourses held within the judiciary. As one former judge from this period explained, “[w]ho is the judge’s audience? It is basically first the bar.”Footnote 6

Therefore, in this section, I turn to examining the prevalent ideas, values, and discourses within the elites of these professional networks since 1985, examining how these dominant ideas and discourses have been shaped by the dissonant institutionalization of the period. In order to understand the development of the role conception of high court and Supreme Court judges, I examine the language and discourse regarding the state of national political institutions and the role of the judiciary amongst the legal elites of the bar and the institutional practices that gained greatest support in these networks (Chanock Reference Chanock2001; Mate Reference Mate2014). This is not an exhaustive study of legal culture in Pakistan’s bar of professional lawyers but only focused on the dominant ideas and discourses regarding the political system, the role of the judiciary, and the popular judicial practices among key elites within these networks.

For this study, I relied on the following sources of information: (1) high court bar resolutions regarding national politics and the role of the judiciary within the system; (2) public statements made by senior lawyers and leaders from Pakistan’s high court bar associations on the same subjects during these periods; (3) interviews with judges and lawyers; and (4) my own more contemporary observations over a year of fieldwork that included spending time in the courtrooms of high court judges and on the campaign trail of bar association election candidates between 2016 and 2018. The interviews that I conducted were semi-structured interviews with lawyers and retired judges conducted in both English and Urdu. I used a method of snowball sampling to recruit and interview retired judges and lawyers who had either served on, or participated in, public interest litigation cases over the past three decades or played important roles in the politics of bar-bench relations during the same period. The interviews and fieldwork observations enriched the narrative constructed through case law and archival data by providing insights into the politics, norms, and preferences informing bar-bench relations and public interest litigation that are not available within the public record. These sources of information helped me to identify the key ideas and discourses regarding the place of the judge within the political system of the time from the sources that would be most directly relevant to shaping the preferences held by present and future high court judges.

Judicial role conceptions in the bar and bench

The dissonant institutionalization embedded in the constitutional order since 1985, the experience with unfettered military rule in the 1980s, the weakness and limited legitimacy of the political class in the 1990s, and the attempts by both unelected and elected governments to capture and control state institutions significantly shaped the ideas that developed within the legal community regarding the role of the judge in the 1990s and 2000s. Opposition to Zia’s military rule did not mean that there was support for the rule of civilian political parties in the 1990s. During this period of institutionalized dissonance and the efforts to weaken and delegitimize the parties staffing the political branches of government, much of the legal community also internalized the narrative of corruption and incompetence of the political parties. The urban middle-class lawyers of the bar associations were disdainful of what they saw as the corruption and factionalism of elite-driven political parties during the 1990s. Sadaf Aziz (Reference Aziz, Cheema and Gilani2015) explains that for the sections of the urban middle class represented in the bar, there was an ascendant aspiration to assert “control over the political process through an anti-corruption movement.”

In the late 1980s and 1990s, with the resumption of democracy, the high court bar associations expanded their political priorities beyond democratic rights to speak out and mobilize on all matters of state, including foreign policy, economic policy, and welfare, and they distrusted the intent and capability of the elected state institutions. In 1992, the Lahore High Court Bar Association sent notice to the United Nations (UN) Security Council to revisit its sanctions against the Iraqi populations.Footnote 7 In 1994, the same bar association condemned the situation of law and order in the province of Sindh and the city of Karachi and demanded the installation of a new government to deal with the situation.Footnote 8 Bar leaders regularly spoke out against the perceived corruption of the political parties and specifically criticized the arbitrariness and nepotism in the elected executive’s appointments to state institutions. In 1992, Hamid Khan, the president of the Lahore High Court Bar Association said in a speech:

Corruption in the ranks of the government has exceeded all imaginable proportions. The country has been rendered into a cauldron of hate and prejudice. The stories about bribery, graft, commissions and other methods of corruption can put to shame the worst during the Byzantine Empire. The main concern of legislative members is the transfers and postings of their favourites with the evident motive of making money and to use such favourites for oppressing and tyrannizing their opponents. (News 1992)

For leading members of the bar, only the institution with which they had the strongest linkages—the judiciary—could rescue the state from its decline. As courts resolved major disputes arising from the dissonant politics of the 1990s, including disputes over the distribution of political authority, the legality of electoral procedures and practices, the criteria for executive and judicial appointments, and the oversight of security operations, lawyers and judges grew increasingly ambitious about the role that the courts could play in shaping national politics. Given the historic separation between the unelected and elected branches, the elected executive’s claim to discretion over the unelected institutions, including state bureaucratic and judicial institutions, was also challenged by leaders of the bar associations, who feared the political capture of state institutions by the political parties. When the Supreme Court overruled executive discretion in judicial appointments, the bar celebrated this decision.

After General Pervez Musharraf took power in 1999, large segments of the leading bar associations around the country opposed his attempts to subordinate the judiciary and challenged his legislative and electoral actions in the courts and out in the streets. Judges who cooperated with the regime were not spared. These bar associations mobilized against Musharraf’s efforts to manipulate judicial appointments, condemned judges who upheld Musharraf’s early changes to the state’s constitutional structure and interference in the political system, and lauded judges who were more willing to confront the regime (Kureshi Reference Kureshi2022).Footnote 9 Thus, the community of high court lawyers in Pakistan was deeply affected by the dissonant institutionalization that characterized this period, the consequent legitimacy crisis facing elected and unelected rulers and institutions, and the increasingly visible role of the courts. The legal community had become more politically engaged, and the elites within the bar coalesced around distrust of both unfettered military rule and the corruption and factionalism of elected political parties. The dissonance meant that neither the elected branches’ claims to authority based on representing the public interest, nor the unelected branches’ claims to authority based on protecting the country’s unity and ideology, went unchallenged within the legal community.

Instead, for leading members of the bar, only the institution with which they had the strongest linkages—the judiciary—could rescue the state from its decline. As the judiciary’s role as an arbiter of political disputes grew increasingly significant, leaders of the politically active bar associations wished to see the judiciary intervene in the affairs and actions of other state institutions and rule on a broad range of political and socioeconomic issues in order to remove corruption and cronyism and ensure that the state acted in the public interest. Legal elites championed the utility of institutional practices that liberated the courts from procedural restrictions so that judges could play a more prominent political role, upholding the interests of the public. For instance, the National Lawyers’ Conference of 1993 resolved that “the judiciary, particularly, the superior courts … should serve as a symbol of liberty, equality and social justice” (Lodhi Reference Lodhi1993).

Similarly, Khalid Ranjha, a bar leader during this period stated that the judiciary had to “go for public interest litigation. … And take suo moto action (cases initiated by the courts without any petitioners) in the affairs pertaining to political corruption to save the system. … Courts should take suo moto of all the corruption of the political culture and take those to task who conduct themselves in breach of political ethics” (Nation 1995). Among serving judges as well, Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah initiated suo moto proceedings to address policy issues such as the increasing violence and criminality in the city of Karachi in the mid-1990s and the growth of corruption in the state. He directly courted media newsmen and issued populist statements to the public such as: “[T]here was a need (for the judiciary) to end the source of corruption afflicting the country” (Haider Reference Haider1997). Justice Wajihuddin Ahmed also stated that that “suo moto is the hallmark of our judicial activism” (Frontier Post 1997). Thus, the discourse of leading figures within the bar and bench was increasingly supportive of the judiciary playing a more prominent and public-facing role in the state, and the relaxation of procedural and jurisdictional restrictions on judicial action in the public interest became an increasingly popular practice within these legal elites.

Most Supreme Court judges emerged from, and were embedded in, this community and enjoyed long-standing ties with the legal elites of the high court bars. Thus, the prevalent values and ideas within these networks during this period shaped their worldview and their conception of what role they needed to play as judges.Footnote 10 Justice Asif Saeed Khosa, a lawyer in the 1990s who became chief justice of Pakistan in 2019, wrote during the 1990s that “legislators passed their time passing motions about breaches of privileges, and the judiciary had to arrest this repugnancy” (Azeem Reference Azeem2017, 224). Lawyers in the bar associations celebrated judges who assertively challenged civilian and military governments and chastised those who were deemed to be too close to the political and military elites.

In interviews, senior lawyers and former judges also highlighted both the importance of the bar as the core network shaping the ideas and preferences held by high court judges and the increasingly populist role conception of Pakistan’s judges that emerged among legal elites in the bar. One senior lawyer explained that “[t]he relationship between lawyer and judges has become far too cozy. As a judge you carry over your prejudices from the bar. Judges come to the bench as fully formed lawyers. You become a judge after having … ideological preferences developed in the bar.”Footnote 11 A former judge explained that “judges … attempted to be ‘effective and bold,’ reaching decisions that would be popular among the lawyers populating their courtrooms. He … did not consider himself bound by procedure, and promises to do substantive justice.”Footnote 12 Another former judge explained that during his tenure he observed that “[j]udges … play to the gallery of the bar, and project populism with the bar.”Footnote 13 Hence, the effect of this era of dissonant institutionalization was that the norms of opposition to military rule, distrust of political parties and representative institutions, and concerns over political corruption and nepotism in bureaucratic appointment processes shaped the legal culture within the high court bar, impacting the discourses and institutional practices that percolated from the lawyer’s community into the superior judiciary.

The populist Supreme Court under military rule, 2005–7

In this section, I lay out how the dissonant institutionalization described above explains the emergence of a populist role conception evident in the Supreme Court of Pakistan’s judiciary between 2005 and 2007. In 2005, Justice Chaudhry was appointed chief justice. Under him, public interest litigation witnessed explosive growth. One of the first steps that he took up was to reactivate the Human Rights Cell of the court (M. Khan Reference Khan2014). The Human Rights Cell received numerous complaints about human rights violations and converted these into formal human rights petitions. The court also took up an increasing number of cases suo moto. The court started taking suo moto notice of issues based on newspaper articles. If a news item struck a chord with an individual judge, the chief justice could directly convert it into a petition. Maryam Khan (Reference Khan2014) explains that this created a feedback loop between the Supreme Court and the media; as the newspapers and electronic media reported on an important policy failure or human rights issue, the court took notice of it, and the media outlets publicized the court’s actions. As the number of suo moto cases increased rapidly, the judges became media favorites, picking up issues that had been the focus of media coverage. The court developed an unprecedented level of visibility. The suo moto power was a potent tool in the hands of the chief justice as there were no prescribed standards or criteria for determining if an issue was worthy of suo moto action, and it was entirely at the discretion of the chief justice if he wanted to intervene, making it easy for him to respond to popular sentiments and issues that would maximize the visibility, popularity, and impact of the court. Bar associations lauded and celebrated the judiciary’s increased interventions in a wide range of governance issues.

The initial focus of public interest litigation under Justice Chaudhry involved regulating the process of economic liberalization by intervening in issues such as unsafe high-rise construction, questionable land acquisitions, and the zoning of prime real estate (Ghias Reference Ghias2010). But this began to change as the judiciary grew more ambitious in challenging the regime’s core policy decisions. The turning point came when the court stalled the privatization of Pakistan’s largest state-owned steel mill in Watan Party v. Chief Executive, President of Pakistan in 2006.Footnote 14 This judgment highlighted key features of the populist jurisprudence of the Chaudhry court. The court accepted a public interest petition challenging the privatization of Pakistan’s main steel mill. The petition claimed that the steel mill’s assets were sold for a price lower than their value and asked the court to review the privatization process. The court asserted that it had jurisdiction to intervene in the privatization process, claiming: “Normally, this Court will not scrutinize the policy decisions or substitute its own opinion in such matters…. However, in this case, we are seized not with a policy centric issue as such but with the legality, reasonableness and transparency of the process of privatization of the project.”Footnote 15

This became the method through which the court turned policy issues into justiciable questions—namely, by framing an issue with a policy outcome as a problem created by unreasonable or non-transparent processes. The court determined that the procedure through which the government had determined the sale value of the steel mill’s assets was “unreasonable” and “betrayed disregard of relevant material” for arriving at a fair price. Therefore, the court overruled the sale of the steel mill, holding that the government had “violated its fiduciary responsibility to its citizens” and that the court had to “rectify the wrong when assets of the nation were at stake.” The court’s decision was a significant assertion of the court’s jurisdiction over the substance of a policy decision—the pricing of steel mill’s assets. It justified intervention on the basis of its role as a protector of the “nation’s assets.” This judgment became the touchstone for much of the populist decision making in the coming years.

The Watan Party judgment had significant repercussions on the relationship between the judiciary and the regime. The military regime was not willing to tolerate a potentially unreliable judiciary that could threaten the regime’s political stability (News 2007). In March 2007, Musharraf forced the suspension of Justice Chaudhry from his post as chief justice, levelling a series of allegations against him. The military regime’s treatment of Justice Chaudhry and his refusal to resign brought the entire lawyer’s community of the country out on the streets in a movement that came to be known as the Lawyers’ Movement. The government responded to the lawyers’ protests with heavy-handed tactics, attacking and injuring protesting lawyers. Images of the black-coated lawyers protesting and braving bleeding wounds captured the headlines (M. Khan Reference Khan2014; Shafqat Reference Shafqat2017) The Lawyers’ Movement turned the dismissal of the chief justice into a massive public controversy. Ousted from public office, Justice Chaudhry became a folk hero, attending well-attended rallies around the country. In these rallies, he emphasized his role as a champion for the people against authoritarianism (Dawn 2007). Through his public interest litigation and actions on and off the bench, Justice Chaudhry was fulfilling the role that many in the legal community had come to favor for judges over the previous two decades, making him a hero to many in the bar.

In June 2007, the court dismissed the presidential reference against Justice Chaudhry and ruled in favor of reinstating him as chief justice. The judgment restoring him clearly articulated the court’s new role conception. The court held that, “[i]n a system where the people had opted to be governed by a written and federal constitution … the judiciary was obliged to act as the administrator of the public will.”Footnote 16 He defended the interventionist approach that the court adopted under Justice Chaudhry, saying that the court had to defend the rights of the people “against any violations and encroachments,” which included the duty of “guarding public property and the public exchequer.” He explained that the judiciary overruled actions and policies of the government because “it stood commanded by the people through the Constitution framed by them to preserve it.” In short, the constitution was the manifestation of the will of the people, and the Court was upholding the “people’s will.”Footnote 17

After Justice Chaudhry’s restoration, the Supreme Court dominated the headlines daily as judges dealt with multiple petitions that challenged Musharraf’s political agenda and destabilized the regime. On November 3, 2007, Musharraf retaliated, and a state of emergency was declared, with the Constitution being suspended once more. Many judges were purged from the judiciary, lawyers and activists around the country were arrested and detained, and curbs were placed on the media. However, the regime did not last long. Agitation on the streets grew as lawyers, civil society activists, and political parties resisted curfews and arrests and continued to pour out on the streets calling for a return to democratic rule (Shafqat Reference Shafqat2017). Musharraf rapidly lost support, and his political party was wiped out in the elections. The PPP and the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), which were the parties he ousted from power, were victorious. He resigned from his office soon after, bringing an end to his regime. Bar associations continued their agitation, demanding Justice Chaudhry be reinstated. Under pressure, the new PPP government conceded and reinstated Chief Justice Chaudhry in March 2009. Thus, Justice Chaudhry became the central figure in Pakistan’s politics after 2007 as a mass movement that built up around him helped bring down a military regime and return democracy to Pakistan.

The populist court and the democratic transition, 2009–18

The end of Musharraf’s military regime did not bring an end to the institutionalized dissonance in Pakistan’s politics. The leading political parties—the PPP and PML—which won the largest number of votes and seats in the 2008 election, were still weak and rebuilding, hobbled by the years of military rule. People still remembered the bruising years of the 1990s, and segments of the elite and urban middle classes who had benefited from Musharraf’s liberalization policies were skeptical of the return of these patronage-based political parties. Musharraf’s constitutional amendments initially remained in place, the military retained significant autonomy and influence in the political system, and elected governments faced stiff resistance as they made efforts to expand their authority over the civil-military bureaucracies (Shah Reference Shah2014).

Once Chief Justice Chaudhry was restored, the Supreme Court did not retreat in favor of elected civilian supremacy. Over the next ten years, the court challenged the actions and decisions of Pakistan’s other power centers, particularly the elected executive and legislature, justified by an apparent interest in ensuring the welfare of the people, often with the tacit backing of the military. Dissonant institutionalization had shaped perceptions among lawyers and judges regarding the need for them to play a role in upholding the public interest, and the Lawyer’s Movement’s success and Justice Chaudhry’s widespread support confirmed for judges and lawyers that the bar and the bench had a legitimate claim as representatives of the public interest.Footnote 18 The vindication and triumphalism in the judiciary, and in the legal community more broadly, and its implications for the role that the judiciary intended to play in the coming years, was evident from a speech that Justice Chaudhry gave at the retirement of a fellow Supreme Court judge, where he stated:

[T]he resistance of the Honourable Judges, the historic movement of learned lawyers’ community … marked a watershed in the political annals of Pakistan. … The superior judiciary has emerged as … the guarantor of the constitutional dispensation in the country…. It is the singular duty of the apex Court not only to enforce the freedom of life of people but also to ensure that complete quality of life is provided to the citizens. … This is what empowers the superior Courts to exercise the power of judicial review in legislative and administrative enactments and actions.”Footnote 19

These judges, who had mostly been part of the bar during the 1990s, retained their skepticism and disdain for the elected political leaders, and the superior judiciary vigorously intervened in the actions of all branches of government, overturning bureaucratic appointments, challenging fiscal and economic policy decisions, and pursuing corruption cases against the political leadership. Even after Justice Chaudhry’s retirement in 2013, the court did not significantly retreat from its assertive new role. Similarly, even as discontent grew within segments of the bar regarding the nature and targets of Justice Chaudhry’s populist jurisprudence, the appetite for judicial populism persisted, even if the preferred targets of populist interventions varied across groups within the bar. As a senior lawyer explained, “[p]opulism is a way to prove yourself to the bar. This is their audience, they are playing to the bar.”Footnote 20 Under Chief Justice Saqib Nisar, the chief justice who served the longest tenure after Justice Chaudhry (2016–19), the court increased the number of cases it took up suo moto, issued policy directives directly from the court, and, with the tacit support of the military, spared no aspect of governance from judicial intervention (Mir Reference Mir2019; Kureshi Reference Kureshi2022).

I had the opportunity to observe the campaign for the elections of the Supreme Court Bar Association in 2016, where the two leading factions within the high court bars across the country—the Professionals Group and the Independents Group—competed against each other for the bar association presidency. In attending campaign events for the two candidates, I observed that the primary accusation hurled against the Independent’s Group’s candidate—Farooq Naek—was his proximity to the politicians from the PPP, which tainted his credibility in the bar. Speech after speech at the Professionals Group’s campaign event in Karachi focused on the corrupt politicians of the PPP and criticized Naek for his affiliation with them.Footnote 21 Soon after winning the elections, the Professionals Group-led Supreme Court Bar Association organized a national lawyer’s convention in the Lahore High Court, which I attended. Leaders from the Supreme Court Bar Association openly chanted “Go, Nawaz, Go,” imploring the Supreme Court to act on corruption allegations against the then elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and disqualify him from political office.Footnote 22 These populist sentiments were not specific to the Professionals Group. When Justice Nisar commenced his spree of populist jurisprudence in 2018, it was leading lawyers from the Independents Group who were regularly invited by Justice Nisar to join, and become party to, the suo moto legal proceedings on all manner of governance and policy issues, to which they willingly agreed.Footnote 23 Thus, even as criticism of Justice Chaudhry’s own approach to judicial populism grew by 2013, the appetite for a populist judicial role, and a more direct relationship between the courts and the people, persisted across large swathes of the legal elites within judicial networks, shaping judicial behavior throughout this period.

The repertoire of the populist court, 2009–18

The judges of the Supreme Court sought to remake the politics and governance of the state by holding the federal and provincial governments accountable to the court’s conception of the interest and will of the people. And the judges justified this expanded role in populist terms, articulated in their judgments, oral proceedings, and off-bench activities, as highlighted in this quote from one such judgment: “Whenever the Court will notice that there is corruption or corrupt practices, it would be very difficult to digest it because the public money of the country cannot be allowed to be looted by anyone whatsoever status he may have.”Footnote 24 One lawyer, explaining the approach of populist Chief Justice Nisar, said: “Populist judges spent a long time sermonizing in the court, and were keen on having their words reported (in the press). … In selecting issues for the court to take up, judges belonged to the urban middle-class, and took up issues which were popular with people from this background … for these judges procedure took a backseat.”Footnote 25

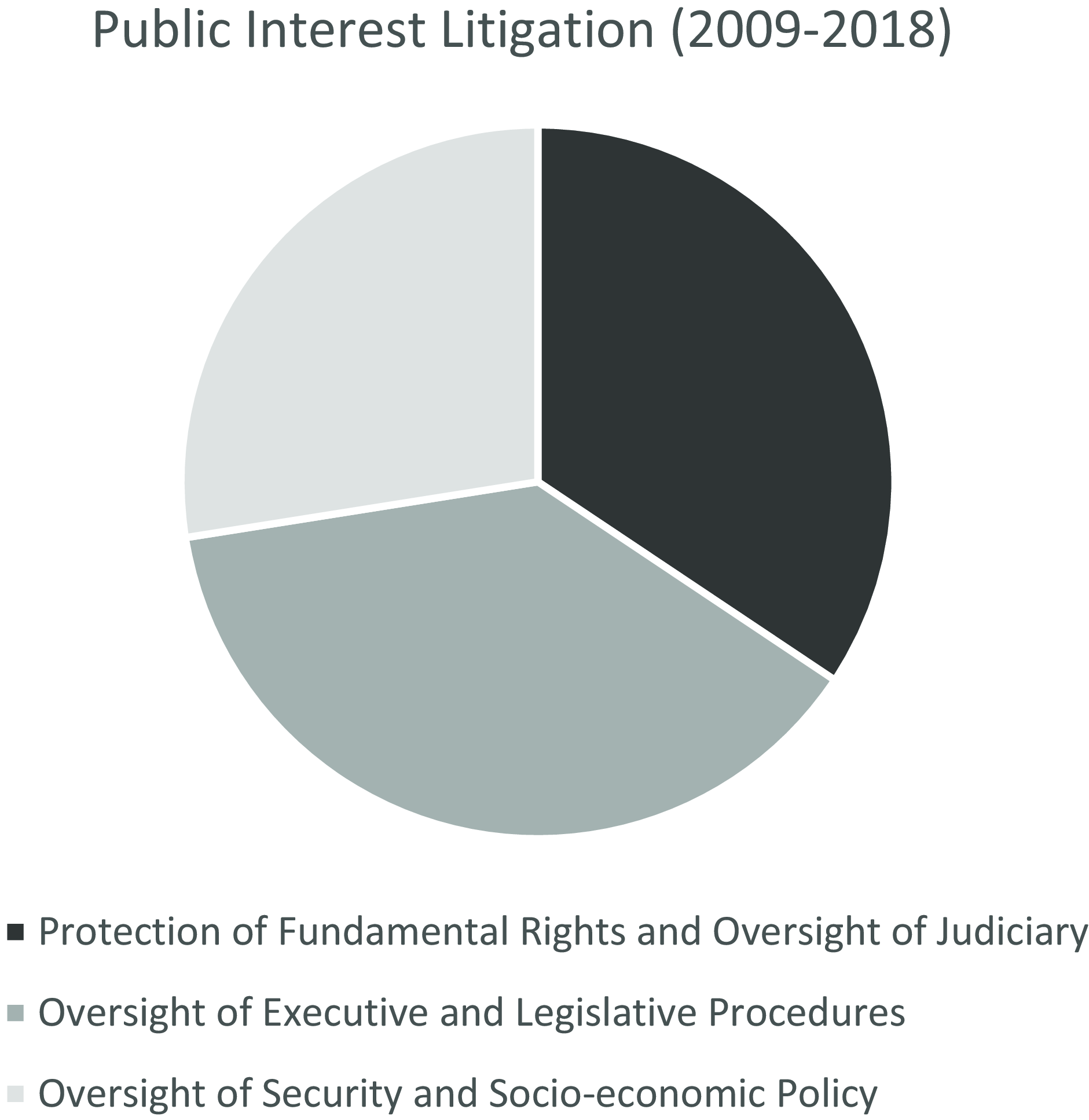

Between 2009 and 2018, the Supreme Court reported 160 judgments in which the court asserted its public interest jurisdiction under Article 184(3). In Figure 1, I divide these judgments into three categories based on their functional distance from the court’s core functions. The core functions of the court include managing the judicial hierarchy and protecting and enforcing the fundamental rights of members of society. Judgments that deal with questions that fall within the scope of these core functions fall into the first category. Judgments that deal with questions pertaining to the internal procedures of the executive and legislature, including procedures of appointments and promotions, fall into the second category. Judgments where the court intervened in policy making on key questions of socioeconomic policy fall into the third category.Footnote 26 What is observable is that, in a majority of the reported cases, the court used its original jurisdiction to deal with questions that fell into the second and third category as it sought to supplant the representative branches.

Figure 1. Public interest litigation, 2009–18 (n = 160).

I will discuss six populist Court judgments in three areas of judicial intervention from 2009 to 2018—(1) political corruption; (2) bureaucratic appointments; and (3) security and socioeconomic policy—to shed light on the court’s populist repertoire and establish how it closely reflected the role conception that developed within the legal community during the 1990s and was cemented by the events of 2007.

Political corruption

As part of its drive against political corruption between 2009 and 2018, the court ousted two elected prime ministers along with scores of elected members of parliament. The Supreme Court retained its power to oust parliamentarians for not fulfilling vague standards of morality and sagacity, as stated under Articles 62 and 63 of the Constitution. The adversarial dynamics of Pakistan’s political system provided the court with an opportunity to act against the political leadership as both political leaders had fallen out with the military leadership and the political opposition courted the judiciary’s intervention. In both cases, the court justified this intervention, claiming to be holding the corrupt political class accountable to the people.

In 2012, the Supreme Court ousted Prime Minister Yousaf Gilani (of the PPP) after convicting him of contempt of court because he refused to write a letter to Swiss authorities to reopen closed corruption cases against his party leader. Justice Chaudhry had ordered Gilani to write this letter because the court wanted to pursue corruption cases against the PPP’s leadership. The Supreme Court bench, chaired by Justice Chaudhry, determined that the actions that the prime minister had taken in defiance of the court amounted to contempt and merited disqualification. The court’s judgment highlighted the consensus view of the judiciary that closely reflected widespread views within the bar: political parties were corrupt and did not act in the public interest, and the judiciary was best suited to tackle this corruption (Aziz Reference Aziz, Cheema and Gilani2015). Justice Khosa stated that the Constitution represented the will of “we the people,” and the executive, in defying the judicial verdict, was defying the will of the people. He famously adapted the poem of the poet Khalil Gibran “Pity the Nation” in order to list rhetorical charges against the government, stating: “Pity the nation that elected a leader as redeemer but expects him to bend every law to favour his benefactors … that launches a movement for rule of law but cries foul when the law is applied against its bigwigs … that punishes its weak and poor but is shy of bringing its high and mighty to book.”Footnote 27

In 2017, the court once again ousted the elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif (of the PML) from power, under Article 62, based on a misdeclaration of assets and allegations of corruption. The judiciary’s actions in this case were even more assertive: Gilani’s removal was based on an actual conviction, but Sharif had not yet been convicted of a crime. A misdeclaration of assets was considered enough to have him removed from power without the possibility of appeal. Justice Khosa, once again a leading member of the bench, opined that Article 62 “provides a recipe for cleansing the fountainhead of authority of the State so that the trickled down authority may also become unpolluted. If this is achieved then the legislative and executive limbs of the State are purified at the top.”Footnote 28 Justice Khosa’s opinions closely matched his own rhetoric when he was a lawyer in the 1990s, as discussed earlier. In defending the court’s power to disqualify a prime minister without a criminal conviction and without the chance for appeal, Justice Gulzar Ahmed stated: “The Court cannot be expected to sit as a toothless body … but it has to rise above the screen of technicalities to give positive verdicts for meeting the ends of justice.” Similarly, Justice Efzal Afzal stated: “[E]xtreme measures have to be taken. The culture of passing candidates by granting grace marks has not delivered the goods. It has corrupted the people and corrupted the system.” The court’s mission to hold the political elite accountable to the people and purify the political system of corruption, and its willingness to bypass procedural limitations to do so, was apparent.

Bureaucratic appointments