“They come from Central America. They’re tougher than any people you’ve ever met.… They’re killing and raping everybody out there. They’re illegal. And they are finished” (Michael Scherer, Time, December 19, 2016, 66, quoting Donald Trump). While these and similar remarks by Donald Trump have provoked controversy and public outrage in some quarters, commentators have observed that such statements helped propel him onto the national stage by activating people’s deep-seated fears about immigrants (Nicholas Confessore, New York Times, July 14, 2016, A1). Invocations of immigrant criminality play a powerful role in US politics despite the well-established empirical evidence that shows that immigrants, including undocumented immigrants, are significantly less likely to engage in crime than the native-born population (Waters and Pineau Reference Waters and Pineau2015; Ousey and Kubrin Reference Ousey and Kubrin2018).

What factors shape perceptions of danger posed by immigrants? I address this question by examining the danger determinations of immigration judges, public officials who decide on a daily basis which immigrants ought to be included in or excluded from our society. This examination has the potential to open new insights into the socio-legal construction of immigrant criminality. The specific empirical focus of this study is immigration bond hearings.Footnote 1 Immigration bond hearings are civil hearings that require immigration judges to decide whether noncitizens should be released or continue to be detained pending the completion of their removal proceedings.

Given the immense case backlogs in immigration courts, noncitizens who are denied release are confined for months, sometimes years, under conditions that are indistinguishable from criminal incarceration. Danger determinations play an especially important role in this process because such determinations result in denials of release, whereas flight risks can be mitigated through the setting of a bond amount or nonmonetary alternative conditions of release (e.g., electronic ankle monitors).Footnote 2 Yet, due to a lack of available data, researchers have been unable to analyze what factors shape immigration judges’ danger determinations.Footnote 3 This study fills this critical gap in knowledge by using original survey data on long-term immigrant detainees in the Central District of California, and unique data coded from the audio recordings of their bond hearings held primarily in 2013 and 2014. Together, these data sets offer rich individual-level information on detainees and their bond hearings that are currently unavailable through any other data source.

Understanding judicial determinations of danger is important and timely for at least two reasons. First, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) currently places hundreds of thousands of noncitizens in detention every year, pending the completion of their removal proceedings. Studies in the criminal justice context suggest that there are significant adverse legal, social, and economic impacts of pretrial detention on defendants and their families, resulting from the defendants’ loss of jobs, socioeconomic dislocation, and alienation from society (Berry Reference Berry2011). The same is likely true for immigrant detainees and their families, given the practical and structural similarities between immigration detention and pretrial criminal detention (see Ryo Reference Ryo2017). Thus, an analysis of immigration judges’ danger determinations promises to shed light on an important, yet overlooked, aspect of the legal stratification mechanism that impacts an ever-widening network of immigrant communities throughout the United States.

Second, identifying the factors that predict judicial determinations of danger is a critical first step in developing policies to improve the accuracy of these decisions and to prevent over-detention.Footnote 4 After all, to evaluate how immigration judges ought to be making danger determinations, we first need to understand how these decisions are presently made. In the criminal justice context, researchers have been able to study pretrial criminal behavior and, at times, the accuracy of pretrial decisions (for a review, see Baradaran and McIntyre Reference Baradaran and McIntyre2012). By contrast, the federal government does not collect, or if it does, does not release, data that will enable a systematic analysis of whether and to what extent immigration authorities are accurately assessing the likelihood of immigrant detainees’ future criminal conduct. For example, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) will not release even a redacted version of the agency manual that “reportedly describes the information DHS collects and tracks on detainees, the officials responsible for entering and screening this data, and those who can access this information” (Kerwin Reference Kerwin2015, 331–32). This lack of public transparency further underscores the need to elucidate the current judicial decision-making process in immigration courts.

Background

I begin with a brief discussion of immigration detention and bond hearings to contextualize my analysis (for a detailed description of the immigration custody determination process, see Gilman Reference Gilman2016). Immigration detention is civil in nature under the law because the stated goal of immigration detention is to confine noncitizens for the “administrative purpose of holding, processing, and preparing them for removal” (GAO 2013, 8, emphasis added). This practice of civil confinement has become an increasingly important and visible tool of immigration enforcement. For example, the total number of individuals who entered ICE detention in any given fiscal year more than doubled from a little over 200,000 in 2001 to more than 425,000 in 2014 (ICE 2011; Baker and Williams Reference Baker and Williams2016).Footnote 5 In early 2017, the Trump Administration ordered increases in the use of immigration detention (Kelly Reference Kelly2017). In June 2017, ICE submitted a fiscal year 2018 budget request that included $4.9 billion to expand the average daily detained population by about 30 percent, from 39,610 to 51,379 (Homan Reference Homan2017).

Broadly speaking, there are two types of immigration detention: discretionary and mandatory detention. For noncitizens held under the discretionary detention provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act, immigration officers may release the noncitizen on conditional parole or on a bond of at least $1,500 (8 U.S.C. § 1226(a)). At this stage, the burden is on the noncitizen to demonstrate that such release would pose neither a danger to the community nor a flight risk (8 C.F.R. § 236.1(c)(8)). A noncitizen may seek a review of this initial custody decision by the immigration court, which is part of the Department of Justice. The immigration judge’s decision may be appealed to the Board of Immigration Appeals, an administrative body also within the Department of Justice.

In contrast, noncitizens subject to mandatory detention are generally ineligible for an individualized hearing as to whether they constitute a danger to the community or a flight risk. These noncitizens include, for example, (1) certain classes of “arriving aliens,” such as individuals seeking asylum who have not yet passed their credible fear determination, and (2) noncitizens, including lawful permanent residents (LPRs), convicted of certain criminal offenses enumerated in the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. §§ 1225(b), 1226(c)). However, a class action lawsuit brought on behalf of long-term detainees in the Central District of California, Rodriguez v. Robbins, changed this legal landscape by requiring a bond hearing before an immigration judge for noncitizens (including certain classes of mandatory detainees) who were continuously detained for 180 days or more (see Rodriguez v. Robbins 2015).

The bond hearings I analyze in this study pertain to the long-term detainees in Rodriguez. The Rodriguez class consists of “all noncitizens within the Central District of California who: (1) are or were detained for longer than six months pursuant to one of the general immigration detention statutes pending completion of removal proceedings, including judicial review, (2) are not and have not been detained pursuant to a national security detention statute, and (3) have not been afforded a hearing to determine whether their detention is justified” (Rodriguez v. Robbins 2015, 1066).

The district court initially issued a preliminary injunction in 2012, holding that the immigration judge must release these detainees “on reasonable conditions of supervision, including electronic monitoring if necessary, unless the government shows by clear and convincing evidence that continued detention is justified based on his or her danger to the community or risk of flight” (Rodriguez v. Robbins 2012, 2). The district court’s preliminary injunction and the subsequent permanent injunction were affirmed by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. In February 2018, however, the US Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s ruling on statutory grounds and remanded the case for further proceedings to determine whether the detainees have a constitutional right to periodic bond hearings (Jennings v. Rodriguez 2018).

The immigration judge has “broad discretion in deciding the factors that he or she may consider in custody redeterminations,” and the judge may give greater weight to certain factors “as long as the decision is reasonable” (In re Guerra 2006, 40). There are no statutory guidelines on what factors are relevant for making danger determinations. However, the following factors are enumerated in the Immigration Judge Benchbook as “significant factors” in bond determinations generally (EOIR n.d., internal citations omitted):

(1) Fixed address in the United States, (2) Length of residence in the United States, (3) Family ties in the United States, particularly those who can confer immigration benefits on the alien, (4) Employment history in the United States, including length and stability, (5) Immigration record, (6) Attempts to escape from authorities or other flight to avoid prosecution, (7) Prior failures to appear for scheduled court proceedings, and (8) Criminal record, including extensiveness and recency, indicating consistent disrespect for the law and ineligibility for relief from deportation/removal.

Theoretical Framework

Although a growing number of legal scholars are beginning to examine US immigration detention (García Hernández Reference Hernández and Cuauhtémoc2014; Das Reference Das2015; Gilman Reference Gilman2016; Tovino Reference Tovino2016), empirical studies of immigration bond hearings are rare (see Gilboy Reference Gilboy1987; Ryo Reference Ryo2016).Footnote 6 Thus, I turn to the longstanding body of research on bail decisions in the criminal justice context to develop a theoretical framework for my empirical analysis. The research on bail or pretrial hearings has assessed the effects of various legal and extralegal factors on hearing outcomes.Footnote 7 With respect to legal factors, studies have found that judges often rely on offense severity and past criminal history in making pretrial decisions (Nagel Reference Nagel1983; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger2005; Williams Reference Williams2017). Below, I review bail studies that have examined extralegal factors that are likely to be of close relevance in the immigration bond hearing context.

Personal Characteristics

Many studies have found that the defendant’s race, ethnicity, and gender play an important role in pretrial decisions (Ayres and Waldfogel Reference Ayres and Waldfogel1994; Free Reference Free2002; Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger2005; Spohn Reference Spohn2009). For example, Demuth and Steffensmeier (Reference Demuth and Steffensmeier2004) find that Hispanic males face the least favorable set of outcomes throughout the pretrial release process and are the group most likely to be detained. The focus on gender and racial or ethnic disparities in studies of pretrial criminal processing is unsurprising, as these characteristics are considered the most basic and enduring axes of inequality in US society. Thus, a natural starting point for the current study’s analysis might be to investigate possible gender and racial/ethnic disparities in judicial determinations of danger. Such a focus, however, is theoretically and empirically problematic here, given that the detention/deportation regime in the United States is a “gendered racial removal program” that targets Latino men (Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo Reference Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo2013; see also Provine and Doty Reference Provine and Doty2011; Armenta Reference Armenta2016). In the current study, 93 percent of the detainees are men, and 84 percent are Hispanic or Latino/a.Footnote 8 These statistics are reflective of the detained population across the United States (Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo Reference Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo2013, 284; see also Simanski Reference Simanski2014, 5–6).Footnote 9

High levels of gender and racial/ethnic homogeneity in the detained population likely attenuate the usefulness of gender and race/ethnicity as differentiating cues or heuristics for immigration judges. We might thus expect other extralegal factors to play an important role in their danger determinations. One such extra legal factor that warrants careful consideration is national origin. National origin is likely to have temporal primacy in immigration proceedings, as it is often one of the first pieces of information that immigration judges encounter on various forms in the detainees’ files, including the Notice to Appear (the charging document that triggers the start of removal proceedings), and applications for relief from removal. Moreover, many immigration judges in bond hearings often seek to confirm the detainees’ national origin after they have been sworn in.

National origin is also likely to be chronically accessible in immigration judges’ working memory given its critical role in immigration proceedings. For example, judges in removal proceedings must approve the country to which the noncitizen must be removed pursuant to statutory requirements (8 U.S.C. § 1231(b)).Footnote 10 In asylum proceedings, evidence pertaining to the applicant’s country-of-origin conditions constitutes an essential element of his or her case (Kerns Reference Kerns2000). That national origin is chronically accessible in immigration judges’ working memory means that national origin need not have been discussed explicitly in any given bond hearing for it to be an important social category that influences the judge’s decision-making process (see Fiske and Neuberg Reference Fiske, Neuberg and Zanna1990; for research on judging and heuristics, see Albonetti Reference Albonetti1991; Steffensmeier, Ulmer, and Kramer Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and Kramer1998; Guthrie, Rachlinski, and Wistrich Reference Guthrie, Rachlinski and Wistrich2007; Hartley and Armendariz Reference Hartley and Armendariz2011).

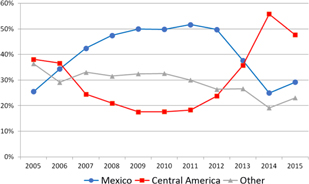

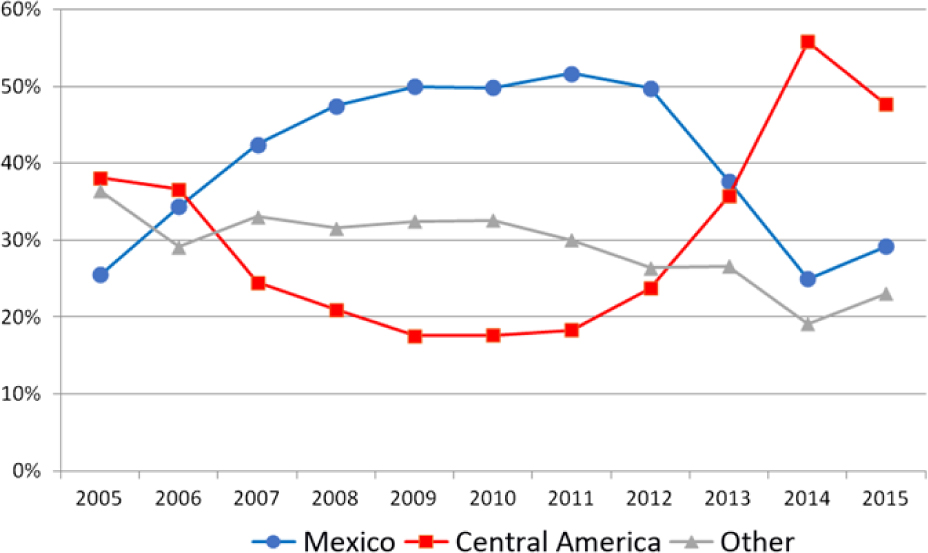

The foregoing discussion underscores the ways in which national origin might become a highly salient basis for categorical thinking in immigration bond hearings. In the current study, I focus on the Central American/non-Central American divide in light of the following legal context. Between 2013 and 2014, the period during which most of this study’s bond hearings took place, immigration courts across the United States saw a steep rise in removal cases of noncitizens originating from the Northern Triangle region of Central America—El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (collectively, Central Americans). Figures 1 and 2, respectively, illustrate these trends nationally and in the Los Angeles Immigration Court—the court in which most of the current study’s bond hearings took place.

Figure 1. Removal Proceedings in US Immigration Courts by Origin Country, Fiscal Year 2005–2015

Figure 2. Removal Proceedings in LA Immigration Court by Origin Country, Fiscal Year 2005–2015

This trend is notable because as group threat theorists have argued, the population dynamics most likely to trigger in-group members’ perceptions of threat—including perceptions of criminal threat—are “sudden demographic changes [that] generate uncertainty and attention” (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010, 40; see also King and Wheelock Reference King and Wheelock2007; Kane, Gustafson, and Bruell Reference Kane, Gustafson and Bruell2013; Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, Martinez, Baumer and Gertz2015).

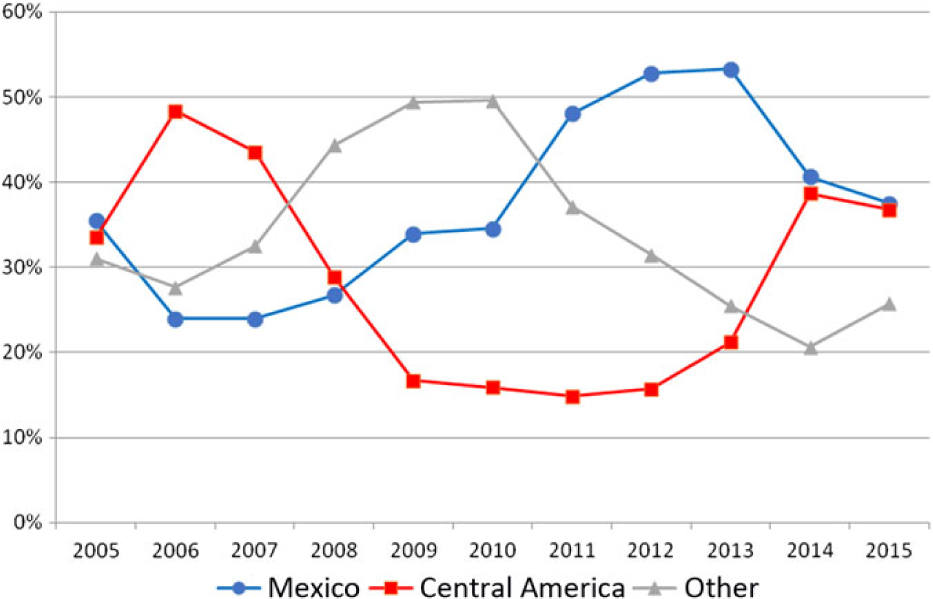

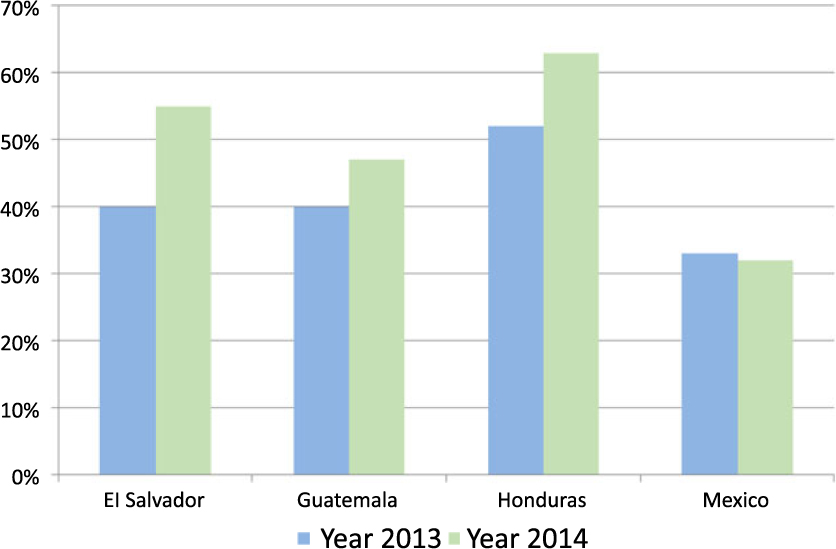

Of note, the rapid rise in removal cases of Central Americans mirrors the “surge” in 2014 of individuals and families apprehended at the southern border fleeing violence in Central America (Restrepo and Garcia Reference Restrepo and Garcia2014; Hiskey et al. Reference Hiskey, Córdova, Orcés and Malone2016). Evidence suggests that the Central American detainees in the current study were not part of the border surge. Specifically, only four Central Americans in this study’s analysis sample had been apprehended at the border, and those Central Americans had been living in the United States long term (twelve to twenty-nine years). Nonetheless, their bond hearings were taking place at the same time as US media reports of the surge and of the conditions in these countries were dominated by stories of crime and violence. For example, my review of relevant news articles published in the Los Angeles Times suggests that a substantial proportion of articles on these countries published in 2013 and 2014 contained references to violence (see Appendix A). Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, the share of news articles during this period that contained violence-related words was significantly higher for El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, respectively, than for Mexico, another country the US public commonly associates with crime and violence.

Figure 3. News Articles on El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico that Contain Violence-Related Words, 2013–2014

Taken together, both the sudden rise of the Central Americans in the removal docket and the prevailing media portrayal of this region as crime ridden and violence prone suggest that the Central American/non-Central American divide might have been an easily accessible heuristic for dangerousness in the current study’s bond hearings.

Legal Representation

Because immigration proceedings are civil in nature, noncitizens are not provided government-appointed legal counsel in these proceedings, including in bond hearings. This means that detainees must either retain legal counsel at their own expense or obtain pro bono assistance through nonprofit organizations, law school clinics, or law firms (see generally Eagly and Shafer Reference Eagly and Shafer2015). By contrast, the Sixth Amendment right to appointed counsel in criminal prosecutions applies to any “critical stage of trial” (National Right to Counsel Committee 2015),Footnote 11 but whether a bail hearing is such a critical stage remains an open question. Thus, in many states, defendants often appear without counsel at their bail hearings (Bunin Reference Bunin2016).

Against this legal background, empirical investigations of legal representation in bail hearings have focused on two key questions. The first question relates to whether legal representation matters at all for pretrial decisions. The second question concerns the relative efficacy of different types of legal representation—that is, do defendants with privately retained counsel obtain more favorable outcomes than defendants with public defenders? On the latter question, a growing body of empirical research has emerged, but the findings have been mixed. Some studies have found little to no relationship between the type of attorney and bail decisions, while other studies have found that public defenders secure less favorable bail outcomes than privately retained counsel (Turner and Johnson Reference Turner and Johnson2007; Williams Reference Williams2017; Hissong and Wheeler forthcoming).

On the first question of whether legal representation (of any type) matters at all for bail outcomes, surprisingly little empirical research exists (for a review, see National Right to Counsel Committee 2015).Footnote 12 The best-known contemporary research on this question comes from the Baltimore City Lawyers at Bail Project. In this project, Colbert, Paternoster, and Bushway (Reference Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway2002) used a randomized experiment to measure the effects of legal representation on the bail hearing outcomes of low-income defendants accused of nonviolent offenses. Colbert, Paternoster, and Bushway found that represented defendants were more likely to be released on their own recognizance and to receive lower bail amounts. In addition, represented defendants were more likely to perceive the legal system as operating fairly than did defendants without representation. As to why legal representation might have produced such a significant impact, Colbert, Paternoster, and Bushway observed: “One reason is that represented defendants could better present beneficial and verified information that supplemented the information provided by the pretrial release representative” (Reference Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway2002, 1755).

This observation by Colbert, Paternoster, and Bushway (Reference Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway2002) suggests that all else equal, detainees with legal counsel may face lower odds of being deemed dangerous than pro se detainees, since lawyers are more likely to be skilled at submitting evidence and presenting arguments that the noncitizen is not a threat to public safety. This expectation emphasizes the importance of substantive knowledge and expertise of legal counsel (see Taylor Poppe and Rachlinski Reference Taylor Poppe and Rachlinski2016, 934–35). Recent studies of legal representation in the civil justice context, however, suggest that lawyers might also matter because they serve a signaling function. Specifically, the presence of lawyers might legitimate their clients and their cases in the eyes of the judges (see Quintanilla, Allen, and Hirt Reference Quintanilla, Allen and Hirt2017). As Sandefur has argued, “lawyer representation may act as an endorsement of lower-status parties that affects how judges and other court staff treat them and evaluate their claims” (Reference Sandefur2015, 16–17, emphasis added). In sum, the foregoing discussion underscores the need to evaluate the possible relationship between legal representation and danger determinations in immigration bond hearings.

Data and Method

Data

The study draws on two data sets. The first data set comes from the Rodriguez Survey. This is an in-person survey of long-term immigrant detainees in the Central District of California who had received a bond hearing notice pursuant to Rodriguez v. Robbins, the class action litigation described earlier (for additional details on the Rodriguez Survey, see Ryo Reference Ryo2016). Between May 2013 and March 2014, a total of 565 detainees who were eighteen years of age or older participated in the survey. The survey was conducted as soon as practicable after the detainees’ scheduled bond hearings; as a result, all but thirty-six detainees (6 percent) had had a substantive bond hearing at the time of the survey. The interviewers provided each eligible detainee a detailed set of information about the survey, and only those detainees who voluntarily consented to participate were surveyed. More than 92 percent of the detainees who were provided information about the survey by the interviewers completed the survey; refusal rates did not vary significantly by gender or country of origin. The survey captures diverse information, including the detainees’ demographic backgrounds, case backgrounds, pre-detention criminal and employment histories, household statuses and family relationships, detention experiences, health conditions, views about the law and legal authorities, and bond hearings.

At the time of the survey, the detainees were held in four facilities across the Central District of California pending their removal proceedings. These facilities are the James A. Musick Facility (Musick), the Theo Lacy Facility (Theo Lacy), the Santa Ana City Jail (Santa Ana), and the Adelanto Detention Facility (Adelanto). Approximately 23 percent of the respondents were held at Musick, 21 percent at Theo Lacy, 13 percent at Santa Ana, and 43 percent at Adelanto. Musick and Theo Lacy are county jails operated by the Orange County Sheriff’s Department. Santa Ana is a city jail operated by the Santa Ana Police Department. Adelanto is operated by a private prison company called the GEO Group, and it houses only immigrant detainees. At the time of the survey, ICE had contracted with each of these facilities to confine immigrant detainees pending their removal proceedings.

The second data set comes from audio recordings of the substantive bond hearings of a subset of the Rodriguez Survey respondents (Rodriguez Audio Data).Footnote 13 To my knowledge, the Rodriguez Audio Data is the first and only data set that codes information from audio-recorded hearings in immigration courts. Working with a team of law students, I systematically coded the audio recordings for many different issues spanning wide-ranging topics, including (1) background information on the detainees, (2) bond hearing basics such as whether a translator was present, (3) bond hearing outcomes and duration, and (4) nature of the discussion and exchanges between various actors in the courtroom, including the immigration judges, government attorneys, detainees, and the detainees’ attorneys (to the extent the detainees were represented).

Most relevant for this study, the Rodriguez Audio Data contain information on the immigration judges’ stated rationale for denying bond. The stated rationale refers to a judge’s statement as to whether the judge found the detainee a flight risk, dangerous, or both. No other existing data—including government data obtainable through public records requests—contain such information, making the Rodriguez Audio Data uniquely valuable. However, it is important to note that in most cases, judges do not explain precisely how they have arrived at their flight risk and danger findings, which precludes a more in-depth analysis of the danger determinations than presented in this study.

To conduct my analysis, I merged the Rodriguez Survey with the Rodriguez Audio Data. Given that there were only twenty-nine female detainees in the merged data set, my analysis is restricted to male detainees. I was not able to code the judges’ rationale for denying bond in eleven of the audio recordings, as the judges in those recordings did not explicitly state their rationales. For example, in one such hearing, the immigration judge denied bond by merely stating that he agreed with the government’s position of “no bond.” I excluded these recordings from my analysis.Footnote 14 I also focused only on substantive hearings by excluding all hearings that were continued, and hearings in which the judge held that there was no jurisdiction to hold the hearing for one reason or another. My final analysis sample consists of 350 substantive bond hearings pertaining to male detainees after list-wise deletion. Approximately 49 percent of the 350 hearings were held in fiscal year 2013, 50 percent in fiscal year 2014, and 0.57 percent in fiscal year 2015.

Measures

The dependent variable, Danger, is whether or not the immigration judge determined that the detainee was a danger to the community (Danger = 1 if the judge deemed the detainee to be dangerous, and Danger = 0 otherwise). More specifically, Category 1 for Danger includes detainees whom the judges explicitly stated posed a danger (19 percent), and detainees whom the judges explicitly stated posed a danger and a flight risk (13 percent). In both situations, the detainees were denied release. Category 0 for Danger includes detainees who were released (62 percent), and detainees for whom the judges explicitly stated posed a flight risk and denied release (6 percent).

The main independent variable of interest, Central American, is whether the detainee is from one of the countries in the Northern Triangle region of Central America. Non-Central Americans, the reference group, consists of detainees from Mexico and twenty-eight other countries (approximately 52 percent and 13 percent, respectively, of the analysis sample). The other main independent variable of interest, Had Attorney at Hearing, is whether the detainee had legal representation at the bond hearing.

In addition, I include in my multivariate analyses two different sets of independent variables that may be related to judicial determinations of danger. The first set of independent variables consists of detainee background characteristics, including (1) the detainee’s age at the time of the bond hearing, (2) whether or not the detainee has a child or a spouse who is a US citizen or an LPR, (3) whether or not the detainee had been employed within the six-month period prior to being detained, (4) the detainee’s English fluency, (5) whether or not the detainee has a high school diploma or more, and (6) the length of stay in the United States in years.

The second set of independent variables measures the recency, seriousness, and extensiveness of the detainee’s criminal history. These criminal-conviction-related measures include (1) the number of days since the detainee’s last criminal conviction, (2) the number of felony convictions, (3) whether or not the detainee has a violent conviction, and (4) the total number of convictions. As noted in Appendix B, violent offenses include assault, battery, assault with a deadly weapon, endangerment, threats, domestic violence, robbery, and homicide. I used the above-described aggregate measures of criminal history to maximize the power and parsimony of my multivariate models, but I also conducted supplemental analyses using disaggregated conviction categories (e.g., assault, robbery, etc.), as discussed in the next section.

Analytical Strategy

First, I examined bivariate relationships between the dependent variable (danger determinations) and each of the independent variables discussed above. Second, I conducted a series of nested binary logistic regression analyses of danger determinations. The full logistic regression model takes the form:

where log represents the natural logarithm; π is the probability that the dichotomous outcome variable Y = 1 (i.e., deemed to be a danger); α is the Y intercept; βs are regression coefficients; X 1 is a vector of detainee background characteristics; and X 2 is a vector of conviction-related measures.Footnote 15 I adjusted the standard errors using the vce cluster option in Stata, given that the hearings are clustered by twenty judges in the analysis sample.

Third, I conducted two sets of supplemental analyses given the significant effects of Central American origin and legal representation on the odds of being deemed a danger. I first examined the bivariate relationship between Central American origin and each of the disaggregated criminal conviction categories to explore whether there are significant differences in the criminal history of Central Americans versus non-Central Americans. I also examined whether there are significant differences in the criminal history of detainees who lacked legal representation versus those who had legal representation. My main goal in conducting these supplemental analyses was to check that the significant effects of Central American origin and legal representation were not due to higher rates and/or a more serious nature of criminal convictions among Central Americans and detainees who lacked legal representation, respectively.

Finally, I re-estimated the same series of nested binary logistic regression models of danger determinations as described above after excluding respondents who did not identify themselves as Hispanic or Latino. This re-estimation required excluding fifty-six detainees from the analysis, reducing the sample size from 350 to 294 bond hearings. The purpose of this supplemental analysis was to test whether the regression results from the analysis using the full sample were being driven by the Hispanic/non-Hispanic divide, rather than the Central American/non-Central American divide.Footnote 16

Results

Table 1 shows univariate and bivariate statistics on the variables used in the analysis of danger determinations (for a correlation matrix of these variables, see Appendix C). Table 1 shows two notable results with respect to detainee background characteristics. First, Central Americans constitute a significantly higher proportion of those deemed dangerous (43 percent) than those not deemed dangerous (32 percent). Second, detainees with legal representation constitute a significantly lower proportion of those deemed dangerous (39 percent) than those not deemed dangerous (57 percent).

Table 1. Descriptive and Bivariate Statistics for Variables Used in Analysis of Danger Determinations

a For categorical variables, bivariate tests consist of chi-square tests; for continuous variables, bivariate tests consist of t tests.

b Reference category is “Speaks English Just a Little/Not at All.”

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

With respect to the conviction-related measures, Table 1 shows that while there are no significant differences across the two groups (Dangerous = No; Dangerous = Yes) in terms of the average number of days since the last conviction, other conviction-related measures do differ across the two groups. First, the detainees who are deemed dangerous have a higher number of felony convictions (an average of 0.65) than those who are not deemed dangerous (an average of 0.29). Second, those who are deemed dangerous are more likely to have prior violent convictions (45 percent) than those who are not deemed dangerous (34 percent). Third, the detainees who are deemed dangerous have a higher total number of convictions (an average of 3.79) than those who are not deemed dangerous (an average of 3.25).

Next, I conducted multivariate regression analyses of danger determinations. Table 2 shows the results of the nested binomial logistic regressions. For ease of interpretation, Table 2 presents odds ratios in addition to coefficient estimates. An odds ratio higher than 1 indicates an increase in the odds (of being deemed dangerous) associated with a one unit increase in a given independent variable. An odds ratio between 0 and 1 indicates a decrease in the odds associated with a one unit increase in a given independent variable.

Table 2. Results from Logistic Regression Models of Danger Determinations

a Reference category is “Speaks English Just a Little/Not at All.”

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Notes: N = 350. Standard errors are in parentheses and clustered by judges.

According to Table 2, Model 3 (full model), two detainee background characteristics are statistically significant. The odds of being deemed dangerous are about 68 percent higher for Central Americans than for non-Central Americans. Detainees with an attorney at their bond hearings have about 47 percent lower odds of being deemed dangerous than detainees who lack legal representation. Two conviction-related measures are also statistically significant: the odds of being deemed dangerous increase by 77 percent with each additional felony conviction, and the odds of being deemed dangerous increase by about 51 percent for detainees with a prior violent conviction. These results are net of not only all the detainee background characteristics, but also criminal-conviction-related measures, including the number of days since the detainee’s last conviction and the total number of convictions.

Do Central Americans have higher odds of being deemed dangerous because they have a longer, more serious criminal history? To address this question, I conducted a supplemental analysis that examined the relative prevalence of different types of criminal convictions among Central Americans and non-Central Americans. Consistent with the official government reporting convention, I categorized individual criminal offenses using the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) classification scheme (see the list of variables under “Conviction Type” in Table 3). I also examined possible group differences in terms of various aggregated conviction-related measures that were included in my multivariate analysis (see the list of variables under “Other Crime-Related Measures” in Table 3). My bivariate tests indicate that most of the differences between these two groups in terms of their criminal history are not statistically significant. Moreover, the two differences that are statistically significant in Table 3 provide evidence contrary to the hypothesis that Central Americans have a longer, more serious criminal history. Specifically, Central Americans are less likely to have drug-related convictions, and more likely to have older criminal convictions than non-Central Americans.

Table 3. Criminal History of Central Americans vs. Non-Central Americans

a For categorical variables, bivariate tests consist of Fisher’s exact tests; for continuous variables, bivariate tests consist of t tests.

b Criminal offenses were categorized following the classification system used in GAO (2011), Table 7, which is based on the FBI classification scheme. All categories include attempt or conspiracy to commit the respective offense. Any given respondent may have more than one conviction.

c Number of convictions lasting 366 days or longer.

d Violent offense includes assault, battery, assault with a deadly weapon, endangerment, threats, domestic violence, robbery, and homicide.

**p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Next, I consider the possibility that detainees without legal representation are more likely to be deemed dangerous because they have a longer, more serious criminal history. To test this hypothesis, I conducted a supplemental analysis that is analogous to the one I described above for Central Americans and non-Central Americans. Table 4 shows that with the exception of Other Offenses, there are no significant differences in the criminal history of detainees who have legal representation versus those who lack representation. The Other Offenses is a residual category of offenses under the FBI classification scheme that cannot be categorized into one of the major offense types. Examples of Other Offenses in the current study sample include a failure to provide child support, trespassing, and illegal sale of cigarettes. I conducted a separate bivariate analysis (results available upon request) that showed that these Other Offenses convictions are not significantly related to danger determinations.

Table 4. Criminal History of Represented vs. Unrepresented

a For categorical variables, bivariate tests consist of Fisher’s exact tests; for continuous variables, bivariate tests consist of t tests.

b Criminal offenses were categorized following the classification system used in GAO (2011), Table 7, which is based on the FBI classification scheme. All categories include attempt or conspiracy to commit the respective offense. Any given respondent may have more than one conviction.

c Number of convictions lasting 366 days or longer.

d Violent offense includes assault, battery, assault with a deadly weapon, endangerment, threats, domestic violence, robbery, and homicide.

* p < .05 (two-tailed tests).

Finally, I tested the robustness of the multivariate regression results presented above by excluding from the analysis non-Hispanic detainees. In effect, this supplemental analysis investigates whether Hispanic Central Americans face higher odds of being deemed dangerous than do Hispanic non-Central Americans, controlling for other relevant factors. This supplemental analysis produced substantially the same results (results available upon request) as the main analysis that included non-Hispanic detainees, suggesting that the significance of the Central American/non-Central American divide is not simply an artifact of the Hispanic/non-Hispanic divide.

Discussion

This study analyzes, for the first time, immigration judges’ decisions about which noncitizens in ICE custody constitute a danger to the community. These judicial determinations, largely hidden from public view and scrutiny, generate an underclass of noncitizens who are viewed as deserving of confinement. This confinement in turn imposes deep stigma and engenders multiple forms of legal, social, and economic disadvantage on the growing population of noncitizens and their families. Below, I consider the study’s key findings and possible interpretations, as well as the limitations of the study and promising directions for future research. Before doing so, I briefly highlight the ways in which detainees in this study might not be representative of the immigrant detainee population nationally.

First, all Rodriguez class members are contesting their removability and/or seeking legal relief from removal,Footnote 17 whereas that is not the case for all short-term detainees. Those who do not contest their removability and/or are not seeking legal relief from removal experience relatively shorter detention for the simple reason that they are no longer in the country. Second, Rodriguez class members may be more likely to have criminal convictions than short-term detainees, as some of the former were mandatorily detained due to their statutorily enumerated criminal offenses. Finally, given the substantial liberty interests implicated in long-term detention, Rodriguez class members are entitled to certain additional procedural protections that are not afforded to short-term detainees in their bond hearings.

The Significance of Central American Origin

My analysis of the immigration judges’ danger determinations produced three main findings. First, I found that the odds of being deemed dangerous are significantly higher for Central Americans than for non-Central Americans, controlling for a variety of detainee background characteristics and criminal-conviction-related measures. One possible explanation for this finding might be that the sudden surge in Central American removal cases triggered a growing sense of criminal threat. Prior research on group threat has documented a positive relationship between the out-group population size and in-group members’ fear of crime, perceived risks of victimization, and punitive attitudes toward minorities (Taylor and Covington Reference Taylor and Covington1993; Chiricos, McEntire, and Gertz Reference Chiricos, McEntire and Gertz2001; Ousey and Unnever Reference Ousey and Unnever2012; Wang Reference Wang2012; Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, Martinez, Baumer and Gertz2015). Of note, studies in this area have highlighted the significance of rapid changes in minority populations (rather than large, stable minority populations) in explaining in-group members’ perceptions of criminal threat and punitive attitudes toward out-group members.

Research on heuristics and categorical thinking suggests alternative or additional explanations as to why judges might view Central Americans as more dangerous. Studies show that decisional environments characterized by time pressure and incomplete information heighten the salience of social stereotypes and biases, as mental shortcuts and categorical thinking become essential cognitive strategies (Fiske, Lin, and Neuberg Reference Fiske, Lin, Neuberg, Chaiken and Trope1999; Kunda and Spencer Reference Kunda and Spencer2003). These studies are especially relevant for analyzing immigration judges’ danger determinations. Immigration bond hearings require judges to exercise wide discretion in making decisions under extraordinary time and informational constraints (Ryo Reference Ryo2016).Footnote 18

In this context, social stereotypes of Central Americans as criminals and gang members might become highly salient. As discussed earlier, US media portrayals of Central America have been dominated by images of violence. In addition, violent gangs that have received a great deal of public attention in the United States are often associated with Central Americans. For example, the Salvatrucha youth gang, or MS-13, which originated in the Salvadoran barrios of Los Angeles in the 1980s, has been called “the Most Dangerous Gang in America” (Dingeman and Rumbaut Reference Dingeman, Kathleen and Rumbaut2010, 367).

Although the data used here are the best and only source of data available for the investigation that I have conducted, these data do not allow me to test group threat theory and heuristics theory formally. One way to test whether and how heuristics and categorical thinking might affect immigration judges’ danger determinations is to conduct an experimental study that exogenously manipulates stereotype triggers. In terms of the group threat theory, data on bond hearings from other years and on bond hearings conducted in immigration courts across the United States will open valuable opportunities for further investigation. Specifically, such data will allow researchers to test whether variations in levels of Central American removal cases over time and across immigration courts are related to changes in the effect of Central American origin on danger determinations.

The Attorney Effect

The second main finding that emerged from my analysis is that the odds of being deemed dangerous are significantly lower for detainees with an attorney present at their bond hearings than for those who lack legal representation. This finding extends prior studies of legal representation in immigration proceedings, which have documented more favorable legal outcomes for represented noncitizens at various stages of the court process, including higher odds of seeking and obtaining legal relief (for a review, see Eagly and Shafer Reference Eagly and Shafer2015). Much like the current study, however, this existing body of research has yet to explore fully whether the attorney effect reflects a causal relationship, and what the specific mechanisms are through which legal representation might make a difference (but see Ryo Reference Ryo2018).

Nonetheless, it is important to underscore what my analysis does rule out. First, I find that the attorney effect is robust to the inclusion of various detainee background characteristics. This suggests that the attorney effect is not merely a reflection of the socioeconomic advantages associated with the ability to obtain legal representation. Second, my supplemental analysis confirms that the attorney effect is not attributable to differences in the criminal history of represented versus unrepresented detainees.

These results encourage us to consider other possible explanations about why having an attorney is associated with reduced odds of being deemed a danger. For example, do attorneys present arguments or otherwise engage in conduct that persuades immigration judges that their clients are not dangerous? One possibility is that lawyers advance personal or individuating information about their clients that makes it difficult for immigration judges to engage in simple heuristics or categorical thinking about detainees as dangerous criminals.

Does the mere presence of an attorney in the courtroom signal to the immigration judge that the detainee possesses personal characteristics (e.g., deference, trustworthiness) that mitigate his or her likelihood of posing a threat to public safety? Consider the recent experimental study by Quintanilla, Allen, and Hirt (Reference Quintanilla, Allen and Hirt2017) showing that employment claimants who lacked legal representation were subject to negative stereotypes. More specifically, Quintanilla, Allen, and Hirt found that law students and lawyers perceived pro se claimants as less competent than legally represented claimants, and that these competence stereotypes mediated the effect of pro se status on settlement awards. In the bond hearing context, do similar social-psychological processes trigger stereotypes about danger when a detainee appears before a judge without an attorney?

These and related questions present challenging issues for research in terms of both data requirements and research design. Yet, answers to such questions promise to inform current litigation and policy debates about the need to provide noncitizens in immigration proceedings meaningful access to competent counsel.

Findings on Criminal History

The third key finding of the study is that felony and violent convictions significantly increase the odds of being deemed dangerous, regardless of the recency of the last conviction and the total number of convictions. Evidence of judicial reliance on prior felony and violent offenses as a proxy for future threat to public safety may be reassuring to many observers. However, predicting an individual’s future criminal behavior is a notoriously difficult task, and an exclusive and mechanical reliance on past criminal history is likely to lead to over-detention (Fagan and Guggenheim Reference Fagan and Guggenheim1996; Baradaran and McIntyre Reference Baradaran and McIntyre2012).Footnote 19 As the court in Chi Thon Ngo v. INS (1999, 398) has stated: “[P]resenting danger to the community at one point by committing crime does not place them forever beyond redemption. Measures must be taken to assess the risk of flight and danger to the community on a current basis.” An important task for future research in this area, then, is to identify and apply insights from criminal justice reform successes and failures in the pretrial hearing context to understand better whether, to what extent, and how detainees’ criminal histories should guide or inform danger determinations in the immigration bond hearing context.

I also found that the recency of the detainees’ criminal convictions and their total number of convictions are unrelated to danger determinations. This finding is largely consistent with increasingly harsh and punitive public attitudes that have animated the development of “crimmigration”—a growing convergence of immigration and criminal laws (Stumpf Reference Stumpf2011).Footnote 20 At the core of this convergence is “a system of tough penalties that favor removal even in cases involving relatively minor infractions or very old crimes” (Chacón Reference Chacón2007, 1844). As one of the detainees who participated in my study of immigration detention declared in describing how immigrants with criminal convictions are treated in the United States: “Once a criminal, always a criminal.”

Conclusion

I conclude by reviewing the current study’s contributions to research and implications for public policy. First, this study highlights the need to integrate our knowledge on heuristics and social cognition with research on immigration and inequality. The movement of people across national boundaries has become increasingly common in recent decades. Yet, national boundaries themselves have become more fortified and militarized. In this milieu, categorical thinking based on national-origin stereotypes is bound to become more prevalent, structuring a variety of social cognitive processes, including legal and judicial decision making. More generally, my findings support investigating alternative bases of bias beyond racial/ethnic bias in situations where social dynamics (e.g., residential segregation) or policy choices (e.g., law enforcement practices) have produced high levels of racial/ethnic homogeneity in certain settings. In these contexts, critical evaluations of other personal characteristics of out-group members that might function as a salient basis for social categorization and stereotypes may be central to understanding new and emerging axes of stratification.

Second, the current study contributes to research on judicial decision making by highlighting how legal processes may shape and, in turn, may be shaped by, social constructions of danger (Warner 2005). My findings also contribute more specifically to the literature on judicial decision making in immigration law. Existing studies of immigration court decisions have focused predominantly on the final outcomes, as researchers have been unable to look into the “black box” of immigration proceedings to examine the judges’ reasoning or rationale for their decisions. Shining a light into this black box is important, in part because noncitizens’ contacts with immigration authorities, including and especially immigration judges, constitute critical moments in the noncitizens’ legal socialization process—a process that could widely foster trust or distrust about the US legal system among noncitizens in the United States and abroad (Ryo Reference Ryo2015, Reference Ryo2017). How immigration authorities justify their decisions, quite apart from the final outcomes themselves, may have significant impacts on the legal attitudes of noncitizens.

Finally, this study contributes to research on social control and criminal punishment (Britt Reference Britt2000; Yates and Fording Reference Yates and Fording2005; Spelman Reference Spelman2009; Feldmeyer and Ulmer Reference Feldmeyer and Ulmer2011; Feldmeyer et al. Reference Feldmeyer, Warren, Siennick and Neptune2015). As I discussed earlier, group threat theory posits that racial prejudice and intergroup hostility are the dominant group’s reactions to perceived threats by growing minority groups. Consistent with this perspective, studies have found a positive relationship between the size of racial minority populations and expansions in both informal social control, such as violence (see Tolnay, Deane, and Beck Reference Tolnay, Deane and Beck1996), and formal social control, such as policing and criminal punishment (see Bridges, Crutchfield, and Simpson Reference Bridges, Crutchfield and Simpson1987; Liska Reference Liska1992; Jacobs and Carmichael Reference Jacobs and Carmichael2001; Smith and Holmes Reference Smith and Holmes2014; Jordan and Maroun Reference Jordan and Maroun2016). That Central American origin predicts danger determinations might suggest that judges are particularly sensitive to changes in the population dynamics of their court dockets. If so, government policies that prioritize or fast track certain types of cases, which may result in significant shifts in the composition of existing court dockets, may have unintended and negative consequences for the groups implicated in such cases.

The Trump Administration has implemented a campaign of mass detention and deportation. This campaign is largely predicated on the assumption that immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants, present a threat to public safety. Yet, as the US Supreme Court has stated in United States v. Salerno (1987, 766, internal quotation marks omitted): “Imprisonment to protect society from predicted but unconsummated offenses is … unprecedented in this country and … fraught with danger of excesses and injustice.” From this standpoint, judicial determinations of danger in immigration courts will continue to be of paramount public interest that require sustained and systematic empirical scrutiny.

Appendix A

News Articles that Contain Violence-Related Words, 2013–2014

To obtain a rough approximation of the extent to which the media coverage of each target country referenced violence, I examined news articles in the Los Angeles Times. To generate the percentages for each country shown in Figure 3, I implemented the following steps in Westlaw’s Los Angeles Times database. First, I searched for all news articles published in the Los Angeles Times in 2013 and 2014 that mention the target country in the article text (the “country search”). To obtain only news articles, the following sections were excluded from these country searches: Obituaries, Personal Announcements, Sports, and Routine Market/Financial Data. The number of articles resulting from the country search constitutes the denominator in the respective fractions shown in Table A.

Next, I filtered the country search results for articles that contain at least one of the following terms in the article text: gang! homicid! murde! kill! massacre! slaughter! An exclamation point after a given search term requires Westlaw to retrieve all possible endings of that term. For example, kill! retrieves articles containing any of the following terms: kill, kills, killed, killing, and killer. The number of articles resulting from the application of this filter constitutes the numerator in the respective fractions shown in Table A.

Table A. Los Angeles Times News Article Search Terms and Results

Appendix B

Description of Measures Used in the Bivariate and Multivariate Analyses

Appendix C

Correlation Matrix