INTRODUCTION

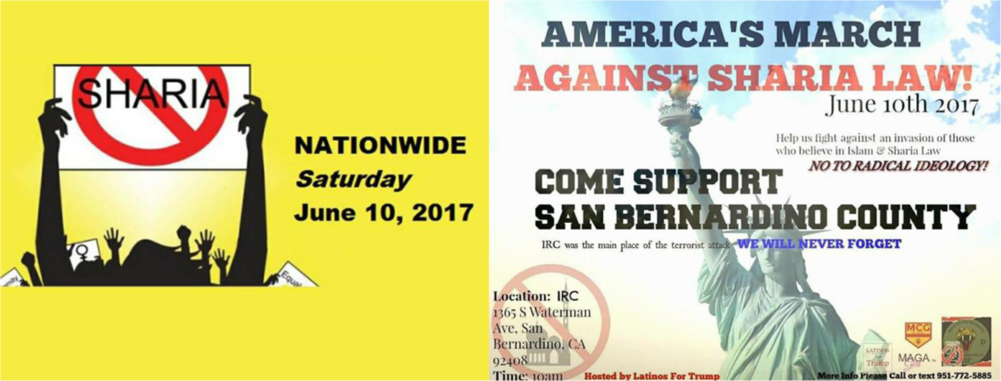

In a 2010 referendum, Oklahoma voters passed by a 70 percent majority a constitutional amendment called “Save Our State,” which forbids state judges from considering shari‘a (commonly translated as Islamic law) in their decisions. Although Oklahoma’s measure was eventually struck down by a federal appeals court, forty-two other states later introduced more than two hundred anti-shari‘a bills of legislation (Elsheikh, Sisemore, and Lee Reference Elsheikh, Sisemore and Lee2017). Legislators were not alone; citizen battles against shari‘a reached a tipping point in the summer of 2017, when thousands of anti-Muslim activists in twenty-nine cities took to the streets in a national “March Against Sharia.” Many of these protests were sponsored by Act for America, whose founder said that any “Muslim … who believes in the teachings of the Qur’an, cannot be a loyal citizen to the United States” (Beinart Reference Beinart2017).

Wealthy individuals and charitable foundations have given millions of dollars to self-proclaimed “Islam experts” to travel around the United States endorsing model legislation that vilifies Islam (Duss, et al. Reference Duss, Taeb, Gude and Sofer2015). They have produced research reports, participated in litigation, and appeared on news programs to describe the dangers they feel Islam poses to America. Anti-shari‘a bills were a leading maneuver in their efforts to fuel anti-Muslim attitudes, which got people asking, “What is shari‘a?”Footnote 1 Critics of the movement said its most tangible impact was to spread an alarmist message about Islam aimed at keeping Muslims on the margins of American life.

These efforts beg the question of what the word shari‘a means to Muslims, and the extent to which shari‘a is relevant in Muslim Americans’ lives. In this historical context fraught with particular challenges for Muslim Americans, we sought to study how Muslims understood shari‘a. To answer this question, we conducted fieldwork across California, home to one of America’s largest and most diverse groups of Muslims. We met participants in the places where Muslims are producing (and challenging) knowledge about shari‘a—in youth groups, college campuses, mosques, Quranic study circles, workplaces, restaurants, and homes. We sought to gauge evolving and fluid perceptions of shari‘a and to learn how legal and religious values are generated, debated, and transformed. By providing results from a study of Muslims in California, this article shows how shari‘a is lived, from urban to suburban and rural settings and from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. In the political context of social marginalization, we found that many Muslims in this study worked to educate themselves about faith, social justice, and rights in order to practice ethical citizenship. This article also uncovers how Muslims have responded to the fear-based portrayal of shari‘a as anti-American, emphasizing the spirit of shari‘a—at once religious and legal—as a rich and diverse ethical and normative code. Defining shari‘a, especially in America, is a political act, and many of the Muslims in our study saw it as a guide for ethical living, not necessarily as a state-posited law (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2018; Stone Reference Stone2011). Demonstrating this relationship between law and religion in everyday life is a particularly useful path to decentering the law, even as we demonstrate the power of law to organize experience.

To investigate how shari‘a and anti-shari‘a hate shape legal consciousness, this article adopts a grassroots approach to the study of law from the perspective of those who encounter and reject populist understandings of Islam. Combining the sociolegal literature on legal consciousness with religious studies literature on lived religion, we contend that anti-shari‘a populism exists alongside a burgeoning Islamic-American “spring” (Massoud and Moore Reference Massoud and Moore2015). Muslims are learning about and adopting principles of shari‘a to make legal decisions or voting choices and to challenge marginalization, including when legislative proposals attempt to eliminate shari‘a. Law and religion are interpretive frameworks that combine and sometimes contradict one another; this article uncovers how people see shari‘a as having both legalistic and extralegal dimensions and, more broadly, how religion and religious law stand in relation to other interpretive and catalyzing frames for legal activism, including human rights and social justice.

Scholars have labeled the fear, anger, or hostility toward Islam as “Islamophobia” or “anti-Muslim racism” (Shryock Reference Shryock2010; Bravo Lopez Reference Bravo Lopez2011; Ernst Reference Ernst2013; Cheng Reference Cheng2015; Green Reference Green2015; Love Reference Love2017; Beydoun Reference Beydoun2018). Because Muslims and Islamic faith are in the public eye and subject to negative publicity in political discourses, the term shari‘a has become a shibboleth—used with the intent of generating fear that a repressive Islamic theocracy might be imposed on an unwilling and unsuspecting American public (Figure 1). Deeply ingrained anxieties against Muslims are also shaping Muslims’ consciousness of the law. In calling attention to the role religion plays in shaping legal consciousness, we do not diminish the importance of other variables such as race, gender, and class, which intersected with religion for many of the people we met.

Figure 1. National “March Against Shari‘a” Posters

The othering of Islam echoes a centuries-long history of racism against ethnic minority groups in the United States (Gotanda Reference Gotanda2011; Selod and Embrick Reference Selod and Embrick2013; Sheehi Reference Sheehi, Daulatzai and Rana2018). The patterns driving Islamophobia are also strikingly similar to those driving anti-Semitism; both use cultural and phenotypical attributes to dehumanize ethnic or religious minorities.Footnote 2 Though present in some form since US independence, the drive to dehumanize religious minorities has taken a remarkable transnational turn against shari‘a since the mid-2000s. Political alarmism has cut across political lines and provoked ideas that welcoming Muslims also means ushering in immigrants who refuse to integrate or who support medieval legal systems that relegate women and religious minorities to second-class citizenship.

But anti-Muslim hate departs from other forms of racism and discrimination in its unusual preoccupation with the law. Virulent opposition to mosque-building in the United States and anxieties about “creeping shari‘a” portray Muslim Americans as supporters of terrorism and link Muslim “foreignness” with a threat to the US legal system (Wright Reference Wright2016; Esposito and Delong-Bas Reference Esposito and Delong-Bas2018). For instance, in a 2009 Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, Yale Law School Dean Harold Koh’s views on transnationalism nearly derailed his confirmation as legal adviser to the US State Department because his detractors distorted his position on shari‘a as foreign law.Footnote 3 The hatred of shari‘a is associated with a fear that any accommodation of Islam—particularly by state and federal legal systems—poses a threat to democratic values, the separation of church and state, and the rule of law (e.g., Boykin et al. Reference Boykin2010). Thus, people’s understandings or misunderstandings of shari‘a as a foreign and threatening legal system render Islam into a visible religious and legal problem.

Law and society literature has given little attention to how anxiety around shari‘a shapes the perception of Islam as an overly legalistic religion. Scholarship on the recognition and accommodation of Islamic law has focused on American courts and the judicial recognition of Islam in family law, contract law, or arbitration and court-ordered alternative dispute resolution (Moore Reference Moore2010; MacFarlane Reference MacFarlane2012; Richardson and Springer Reference Richardson, Springer, Lori and Sullivan2013). This article, instead, offers an analysis based on the voices of Muslims who experience shari‘a not inside courts but outside of them, in the ordinariness of daily living (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Sunier Reference Sunier, Beekers and Kloos2018). Muslims in our study responded to the othering of Islam through an emerging legal consciousness that incorporated facets of shari‘a. Our interviews with them demonstrate how religion works as an ethical framework for action, acting as a check on the lapses of American law and politics at the very moment that national political discourse seemed least likely to protect Muslims from marginalization.

Legal consciousness exists in political, social, and religious context. Refocusing our attention on nonstate normative orders—and decentering the law—helps uncover how people invoke religious sensibilities to respond to inequality by sometimes challenging and at other times enacting the status quo. While this article is based on ethnographic fieldwork in one place, time, and faith, the results of our study may not be unique to California, to Islam, or to an epoch of rising populism. Rather, shari‘a is part of a narrative long circulating in global politics and shaping ideas about ethical citizenship for people facing government scrutiny, including in India, Malaysia, Nigeria, Sudan, and Kenya at different times (see, e.g., Hirsch Reference Hirsch1998; Massoud Reference Massoud2013; Eltantawi Reference Eltantawi2017; Moustafa Reference Moustafa2018; Lemons Reference Lemons2019). Yet, like law, religion is not an isolated, stable, and coherent category, and it cannot be singled out from other aspects of human experience like work, play, governance, and exchange. In exploring how Muslims draw on shari‘a, including as a source of social justice, we contribute to transnational sociolegal scholarship that brings religion to bear on legal consciousness. In showing how racism and sexism shape interest in shari‘a and investigating what shari‘a does and does not do for those who invoke it, we respond to Susan Silbey’s call (Reference Silbey2005) to theorize the relationship between law and inequality. Relying on law’s authority or invoking religion may preserve racial and gender hierarchies, but the Muslims in our study invoked religion precisely to challenge those hierarchies.

US Supreme Court cases have upheld constitutional protections of religious attire and grooming.Footnote 4 But Muslims in the United States still encounter government-sanctioned profiling and surveillance practices, including through community-based “countering violent extremism” programs and the “Muslim travel ban” of 2017. When the Muslims in this study perceived that US laws fell short of their aspirations—from laws that target minorities and immigrants to issues surrounding prison overcrowding, poverty, or the failure to protect LGBTQ rights—some of them instead turned to and mobilized Islamic values of fairness, equality, and justice as their framework for critique. They used shari‘a to challenge and expose flaws in state and society when (to them) state laws failed to live up to the values of fairness or justice. By aligning shari‘a with social justice standards, many of the Muslims in this study made shari‘a a source of their legal consciousness. In this way, shari‘a was not just a legal ideal but an ethical standard by which they judged the US legal system’s ability to produce just outcomes for the poor or marginalized. Thus, shari‘a matters not only because anti-Muslim discourse makes the word itself cogent and visible to non-Muslims. It also matters to the development of legal consciousness, particularly for people who confront a virulent and legalistic form of racism rooted in the fear of Islamic law as un-American.

Recognizing the failure of law to fulfill its aspirations of fairness and justice, Muslims are countering narrow representations of Islam as an intrinsic and dangerous alterity. Their experiences of discrimination bring into sharper relief how legal consciousness is shaped by everyday beliefs and practices understood as religious. Our study finds three formative stages of individual legal consciousness that, together, form the nascence of mobilization: perceiving shari‘a and discriminatory depictions of it, educating oneself about shari‘a’s social and political relevance, and forming an intention for social change. Documenting these three interrelated stages of personal development uncovers how group identity formation processes are a precursor to legal mobilization.

Drawing on interviews with Muslims across California, this article illuminates the relationship between legal consciousness, lived religious experience, and the battle against inequality. Some work in law and society has illustrated the interrelationship of rights, religion, and politics (see, e.g., Chua Reference Chua2019; Darian-Smith Reference Darian-Smith2010; Wilson and Hollis-Brusky Reference Wilson and Hollis-Brusky2018). But much of the sociolegal literature on marginalization and disputing in twenty-first century America does not treat religion—especially Islam—seriously, and most of the literature on law and religion does not treat legal consciousness seriously. Inattentiveness to the ways religion matters to inequality and legal consciousness has stunted the development of a sociolegal theory on religion. Our empirical study of Muslim experiences of shari‘a in California exposes an alternative site to understand the consequences of anti-Muslim populism, and how shari‘a matters (and fails to matter) in the lives of Muslims. By addressing the interplay between legal consciousness and everyday religious practice, at the understudied intersection of sociolegal studies and religious studies, this article reveals the complex processes through which ordinary people make sense of the multiple normative worlds they inhabit (see, e.g., Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse1986).

In adopting a “lived” or bottom-up approach to religion and law, this study privileges the meanings people give to and the intentions they derive from shari‘a, shifting the discourse on Islam away from its colonialist or Islamist history and toward Muslim Americans’ actual experiences. To do so, this article first explains the concept of shari‘a and provides a history of its public representation in national discourses as a source of fear of Muslims and foreign law. Second, the article situates our research investigating the lived experience of law and religion in the context of sociolegal literature on legal consciousness and religion. Third, we describe the field research methods used in this inquiry. Fourth, we explain how the participants in our study experienced the concept and term, shari‘a, by perceiving shari‘a and discriminatory representations of it, educating themselves about shari‘a, and forming intentions for social change. Finally, we conclude by discussing the implications of this inquiry into shari‘a at this historical moment in the United States for the study of legal consciousness and mobilization among religious and ethnic minorities.

WHAT IS SHARI‘A?

Shari‘a is an Arabic term with no easy English equivalent. Literally it refers to a pathway, usually toward a water spring, which signifies purity and cleansing. In theological and juridical spheres, it is understood to mean God’s divinely revealed law (Afsaruddin Reference Afsaruddin, Yvonne and Jane2014; Ahmed Reference Ahmed2016; Ahmad Reference Ahmad2017). Over time, shari‘a has come to be understood as the moral, ethical, and behavioral principles that jurists interpret to yield specific rulings. Shari‘a, thus, encompasses both the legal principles of jurists and the discursive principles guiding people’s actions. While often presented in the West as the core concern of Islam, and often only in relation to corporal punishments (called huduud), the word shari‘a appears only once in the Qur’an, the holy book of Islam. For scholars of Islam, shari‘a is also only one part of the many disciplines of Islamic studies.Footnote 5

Shari‘a is a word whose full meaning and elasticity render it indeterminate. It is not a unified set of laws to which Muslims are uniquely bound. Instead, it encompasses relationships between humans and the divine through acts of worship (ibadat) and it guides social relationships, including among family and economic relationships (mu‘amalat). Shari‘a is founded on a triangular relationship between God, the individual, and society; its meta-principles (maqasid) include the preservation of faith and life.

“Doctrinally minded” scholars of Islamic law study shari‘a to investigate how human reasoning interprets divine Islamic sources (March Reference March2009). Their juristic elaborations of shari‘a have produced two disciplines in Islamic theology called usul al-fiqh (legal theory, or how to use Islamic sources to create legal rules) and fiqh (the rulings of jurists over the centuries). These fiqh opinions are varied and diverse: there are four major schools of Sunni Islamic legal thought, in addition to the Shi‘a Jafari school.

For nonexperts, shari‘a may be a set of values that uphold democratic ideals such as good governance, basic freedoms, and accountability (Esposito and Delong-Bas Reference Esposito and Delong-Bas2018). Others associate shari‘a with barbarism, misogynistic men, and oppressed women (see Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod2013). For many Muslims in America, the word shari‘a historically had not been a major part of an everyday vocabulary, until it was splashed onto newspaper headlines after 9/11. Muslim Americans have come to make shari‘a matter, however, by relabeling what anti-Muslim discourse considers something to despise into a resource for justice. In a national space dominated by negative opinions of shari‘a, Muslims are giving shari‘a a new utility by consciously inverting it from a foreign discourse to be feared into a domestic resource for justice.

ISLAMOPHOBIA IN AMERICA

Pundits have long decried immigration’s impact on the United States as one of loss and violation—declining economic opportunities and an altered identity brought on by foreign migrants who do not love “ordinary” America (Sara Ahmed Reference Ahmed2004, 118). These discourses have been applied to Islam and Muslims for decades (Beydoun Reference Beydoun2018). The 1967 war over Israel’s boundaries, the long lines at American gas pumps brought on by the 1970s oil embargoes, and the occupations of US embassies all generated stereotypes that Muslims—particularly those from the Middle East—were a politically explosive group who controlled critical natural resources. During the 1980s and 1990s, Americans responded to images of a shadowy Middle Eastern terrorist enemy with collective fear and loathing, which leveraged considerable support for securitizing US borders.

Contemporary attitudes toward shari‘a are a product of a long history of associating Islam with extreme legalism and corporal punishment in order to promote European imperialism or Islamism (Hallaq Reference Hallaq2009). Popular books and articles have since posited the image of a civilizational clash (e.g., Huntington Reference Huntington1993). Terrorist attacks on US embassies in 1998 and in New York and Washington, DC, in 2001 facilitated the image of America locked in combat with religious extremism. President George W. Bush’s administration used highly publicized detentions and special registrations of young men from Muslim-majority countries in a manner that was “geared to salve the nation’s thirst for action against a newly reviled group” (Haney Lopez Reference Haney Lopez2014, 117; see also Cainkar Reference Cainkar2009; Shiekh Reference Shiekh2011; Bayoumi Reference Bayoumi2015). In a 2006 national address, Bush warned of a civilizational jihad, saying that the American war on terror “is a struggle for civilization. We are fighting to maintain [our] way of life” (President Bush’s Address to the Nation, September 11, 2006, cited in Haney Lopez Reference Haney Lopez2014, 119). These words and others like it further cemented the new category of “Muslim” as a threatening group, leading to calls to excise Muslims and Islamic institutions (Apuzzo and Goldstein Reference Apuzzo and Goldstein2014; Johnson Reference Johnson2015; Beydoun Reference Beydoun2018; Kashani Reference Kashani2018). Paranoia over “sleeper cells” and Barack Obama’s rise to national prominence in 2004 were conflated with conspiracies surrounding his citizenship and that he was a “stealth Muslim” who would introduce Islamic law by swearing his presidential oath on the Qur’an (Kristof Reference Kristof2008).

These examples touch the surface of how shari‘a has been used as a weapon of Islamophobia. By 2008, the growing perception of Muslims as a security threat metastasized to state legislatures, where the term shari‘a took center stage as the signifier for local anti-Islamic sentiments. That year, anti-Muslim activists began to promulgate legislation that would “ban” shari‘a state by state (Patel and Toh Reference Patel and Toh2014; for maps of the spread of anti-Muslim hate across America, see Elfenbein, et al. Reference Elfenbein2018). By the end of 2011, more than half of American states had introduced such a bill. By 2020, only a handful of states had not introduced this legislation.Footnote 6

Shari‘a also became a wedge issue in electoral politics. In 2010, Newt Gingrich, a former speaker of the House of Representatives, warned of a jihadist conspiracy underway in the United States to implant shari‘a as a system of law explicitly at odds with core American and Western values. In his speech that year to the American Enterprise Institute, Gingrich called for “a federal law that says shariah law cannot be recognized by any court in the United States” (Gingrich Reference Gingrich2010). In a foreign policy speech a few months later, Rick Santorum, then a US senator from Pennsylvania and a candidate for the Republican nomination in the 2012 presidential race, described “creeping shari‘a” as “an existential threat to America.”Footnote 7 Santorum and Gingrich were not alone: five of the nine major Republican presidential candidates that year had also publicly denounced shari‘a.

Shari‘a, and anti-Muslim hate in general, persisted in the 2016 presidential election. Following a shooting in San Bernardino in 2015, candidate Donald Trump called for a “total and complete shutdown on Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on” (Johnson Reference Johnson2015; see also Hauslohner Reference Hauslohner2016).Footnote 8 Senator Ted Cruz, then a rival for the Republican presidential nomination, proposed to “empower law enforcement to patrol and secure Muslim neighborhoods before they become radicalized” (Zezima and Goldman Reference Zezima and Goldman2016). Other nationally prominent politicians also carried the banner. After an attack in Nice, France, in which eighty-four people were killed, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich called for a “test” of every Muslim in the United States and for deporting those who believe in shari‘a (Etehad Reference Etehad2016).

These statements from political leaders are representative of the negative perceptions of Muslims as believers in a rigid, foreign law and, thus, as unreliable and disloyal.Footnote 9 But how have Muslims responded to this perception of Islam and shari‘a as anti-American? Some, whose speech has been chilled by these debates, are much more reluctant to discuss the importance of religious law and ethics. Others, particularly Muslim scholars and Islamic civic groups, have openly discussed shari‘a and its place in American law and society, identifying points of convergence with democratic values (Jackson Reference Jackson2011a; Howe Reference Howe2018). The internal diversity of their views typically goes ignored in the polarizing context of partisan, anti-shari‘a politics that relies instead on tropes that depict Islam and Muslims as anti-modern and inherently incompatible with American political liberalism.

Prior to national scrutiny of shari‘a, many Muslims had never felt pressure to explain the term, much less define it as a discrete discursive object (Howe Reference Howe2018, 173). But anti-shari‘a campaigns, particularly since 2009, have caused alarm not only among non-Muslim Americans but also among Muslim Americans who saw a public image of shari‘a emerge as a foreign and anti-American law. Individual Muslims facing discrimination began to educate themselves about the term, its meanings, and its relationship to American law. Advocacy groups redoubled their efforts to explain Islam and shari‘a in a politically viable way, appealing both to courts of law and courts of public opinion to showcase Islam’s compatibility with American political liberalism and the rule of law (Moore Reference Moore, Kenney and Moosa2014).

SHARI‘A IN CONTEXT: LEGAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND LIVED RELIGION

To understand, in the context of this disparagement, how some Muslims make shari‘a resonate with daily realities and how shari‘a has become a resource for social justice, it is necessary to bring together two parallel lines of scholarship on everyday interactions: law and society studies of legal consciousness and religious studies of lived religion. Combining these two fields reveals how the meaning of law and the concept of fairness emerge together, often through normative frameworks outside state authority.

Legal Consciousness

As law becomes part of people’s daily interactions, it becomes unmoored from its official materials (e.g., doctrines, statutes, cases), personnel (e.g., lawyers and judges), and institutions (e.g., courts and bureaucratic agencies) (Silbey Reference Silbey, Smelser and Baltes2001, 730). For this reason, many sociolegal scholars have looked beyond courts to observe how ordinary people talk about law. Legal consciousness, thus, refers to “the ways … individuals mobilize, invent, and interpret legal meanings and signs” (Silbey Reference Silbey, Smelser and Baltes2001, 726). Put another way, legal consciousness scholars are interested in the thoughts, actions, ideologies, and practices of so-called “ordinary people as they navigate their way through situations in which law could play a role” (Chua and Engel Reference Chua and Engel2018, 1). The experience of the discursive and cultural practices commonly recognized as “legal” can bring people to accept legal systems that reproduce inequalities (Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998). Legal consciousness is neither static nor unitary. Rather, it holds in tension a multiplicity of actors and their often contradictory or overlapping ideas about the nature and function of law and the variable ways people encounter and reconcile the law in their lives (see, e.g., Halliday and Morgan Reference Halliday and Morgan2013).

The most exemplary studies of legal consciousness have focused on how people experience “official” law (see, e.g., Merry Reference Merry1990; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004; but see Hertogh Reference Hertogh2004). Some of this research has focused on how experiences of race and racism shape legal consciousness (Nielsen 2000; Reference Nielsen2004; Lovell Reference Lovell2012). Other research focuses on the highly contingent nature of law in welfare agencies (Sarat Reference Sarat1990), at the workplace (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2003), in emergency shelters (Ranasinghe Reference Ranasinghe2014), and on the streets (Levine and Mellema Reference Levine and Mellema2001; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004; Wilson Reference Wilson2011), in addition to comparative studies outside the United States (e.g., Hertogh Reference Hertogh2004; Kurkchiyan Reference Kurkchiyan2011; McCann Reference McCann2012; Chua and Engel Reference Chua and Engel2018). Over time, legal consciousness becomes a “naturalized” way of understanding state law, as people’s “habitual patterns of talk and action, and their common-sense understanding of the world” become infused with a juridical awareness or vocabulary (Merry Reference Merry1990, 5). Suggesting that investigations of law’s power are best when focused at the level of lived experience, this line of sociolegal research locates the diverse ways law’s power is exercised, understood, and sometimes resisted by individual actors (e.g., Fritsvold Reference Fritsvold2009; Hull Reference Hull2016). But little is known about how religious alternatives to official law shape legal consciousness (but see Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse1986; Barak-Corren Reference Barak-Corren2017; Lemons Reference Lemons2019).

This line of research provides a common language from which sociolegal scholars can analyze how shari‘a resonates in everyday lives. By not examining alternative normative frameworks, scholarship on legal consciousness has sidelined the “jurisgenerative” power of communities outside of the formal boundaries of the state (Cover Reference Cover1983; see esp. pp. 26–40). An individual’s understanding of shari‘a, for instance, may shape their understanding of social relations, authority, and practices that are normative and regulatory but not necessarily official state law. Combining legal consciousness with shari‘a consciousness reveals how individuals contest, confirm, or correct the meanings of their roles, obligations, responsibilities, identities, and behaviors, and the meanings they attach to law itself. Training our lens more explicitly on the cultural dimensions of discourse offered by shari‘a underscores how normative frameworks outside of state law shape people’s experiences of law and how nonlegal resources help people resist debilitating forces.

Lived Religion

Just as traces of law can be found in people’s ordinary lives, traces of religion also can be found. For this reason, the academic study of religion has taken a cultural turn, giving attention to discourse, identity, symbols, meaning-making, lived experience, and the ways religion shapes and is shaped by everyday practices (Ammerman Reference Ammerman2016, 83). Just as the extensive literature in legal consciousness locates law in everyday life, studies of “lived” religion locate faith, rituals, symbols, behavior, and religious tradition in everyday patterns of communication and action. Scholarship on lived religion can provide an important heuristic device to analyze how shari‘a resonates in everyday lives or, in other words, how the concept of shari‘a as fixed and canonical is modified within the analytical field of the “everyday.”Footnote 10 Lived religion is a field that explores the materiality of religious life, the embodiment of religious practices, and daily discourse far from the elite spaces of religious and cultural authority. It focuses on the embeddedness and local inflection of religious epistemology and behavior as individuals and groups make sense of their experiences and religious practices. Lived religion, as historian Robert Orsi put it,

refers to the places and times where the ordinary and the daunting, the exhilarating and joyful realities of human experience are taken hold of, by men and women in the company of their gods, and where other discourses (nationalism, for instance, or political fearfulness) are most intimately encountered and engaged…. These other discourses do not … always … dominate (Reference Orsi, Schielke and Debevec2012, 153).

Religious norms form an alternative framework to state law, guiding decision-making, rule following, and legal mobilization. Diverse studies of lived religion illuminate how these “many messy qualities” of religious content exist outside of formal religious institutions, including in the household, marketplace, workplace, or informal religious gathering (Bender Reference Bender2016, 101; see also Orsi Reference Orsi1985, Reference Orsi, Schielke and Debevec2012; Ammerman Reference Ammerman2007, Reference Ammerman2014; McGuire Reference McGuire2008; Schielke and Debevec Reference Schielke and Liza2012; D’Antonio, Dillon, and Gautier Reference D’Antonio, Dillon and Gautier2013). Like law, religion “is always … in-action [or] in-relationships between people, between the ways the world is and the way people … want it to be” (Orsi Reference Orsi2003, 172).

An emphasis on the lived experience of law and religion presents an energetic alternative to canonical accounts in both domains. In short, law and religion are, together, dynamic producers of meaning in the home, workplace, schoolhouse, and public spaces. Attending to law and religion in these circumstances offers the theoretical resources for developing the study of law and society. For sociolegal scholars, law and religion are not separate as much as they are a helix, “twisting … sacred and profane around each other through the movement of people’s days, the contingencies of their social circumstances, and the dynamics of their relationships” (Orsi Reference Orsi, Schielke and Debevec2012, 154).

Similar to the relationship between sociolegal studies and doctrinal law, literature on how people experience religion outside of official institutions has come largely from scholars on the field’s margins that felt their concerns were neglected or overlooked by the field’s mainstream. These include growing numbers of women, people of color, immigrants, and queer scholars who give attention to how gender, race, and power reflect or challenge the discursive authority of religion (Min Reference Min2010; Wilcox Reference Wilcox2009; Ammerman Reference Ammerman2016; Chan-Malik Reference Chan-Malik2018).

While the literature on lived religion helps to understand the dynamics that encompass people’s everyday lives and how religion remains important in pluralist societies, this work has focused largely on Christianity, with little attention to the lived experience of Islam for Muslims in non-Muslim majority contexts. What remains to be addressed is how, if at all, are Muslims discussing shari‘a; how are religious values produced, debated, and challenged in the course of these conversations; and how is shari‘a understood as an intellectual project of medieval authorities overseas or something more contemporary or even American? Answering these questions helps to develop links between studies of lived religion and legal consciousness.

Insufficiently studied in both legal consciousness and lived religion scholarship is how the politicization of shari‘a shapes the experiences of Muslims and how Muslims are responding to it. Combining the legal consciousness literature with lived religion reveals an important research question: how do Muslims understand, experience, and mobilize shari‘a in the context of virulent attacks on it? To answer this question, we turned to qualitative and empirical research with Muslims in California.

METHODS

This section explains the methods we adopted to study how Muslims experience shari‘a. Because the sociolegal literature has been remarkably silent on the Muslim experience of Islamic law and discrimination in non-Muslim majority contexts, our work has been purposefully inductive and theory-generating. The scarcity of empirical research on shari‘a in the United States demanded a bottom-up case study approach.

Case Selection

To understand how Muslims are responding to the fear-based narrative of shari‘a and creating different meanings of shari‘a, we draw from material gathered during 104 interviews with Muslims across California. We chose California because of its broad racial and ethnic diversity and because many Muslims call California home, almost more than any other US state.Footnote 11 The northern California city of Berkeley is home to the country’s first fully accredited Islamic liberal arts college (Zaytuna College) and the southern California city of Claremont has been home to America’s first Islamic graduate school (Bayan Claremont). In 2015, the first women-only mosque in the United States opened in Los Angeles to increase access to female Muslim scholars and perspectives.Footnote 12 Of the nation’s two premier Islamic civil rights organizations, one was co-founded by a Muslim from the San Francisco Bay Area, and the other continues to be based in Los Angeles.Footnote 13 Islamic nonprofit organizations across the state have provided curricula, trainings, speakers bureaus, and social services to the poor and politically underrepresented. In 2018 the California Assembly named one of them the state’s “non-profit of the year.” These diverse people and institutions from and in California are helping plant the seeds of an American Islam. California has long been a cultural bellwether in the United States, and diverse ethnic communities in the state have also been at the forefront of shaping religious discourses (Leonard Reference Leonard1992; Morales Reference Morales2018).

California is also not immune to Islamophobia, as major anti-shari‘a advertising campaigns emerged across the state during the course of our research between 2013 and 2016. The campaigns attempted to appeal to progressive principles, shared by many Californians, on the protection of religious freedom and the promotion of sexual orientation equality (Figure 2). Later, in 2017, protests against shari‘a and Muslims took place across the state—in San Jose, Santa Clara, Roseville, and San Bernardino, among other cities nationwide (Figure 1, above). In these ways, California offers an important site to investigate how Muslims have received anti-Muslim discourse and how this discourse has influenced new forms of legal consciousness and social engagement.

Figure 2. Anti-shari‘a Advertisements on San Francisco Buses

Qualitative Interviews, Field Research, and Analysis

With the help of a graduate student researcher and a nonacademic specialist on our project, we began by contacting Muslims in urban and rural counties across California. Our interview team was made up of Muslims and non-Muslims; generally, at least one Muslim and non-Muslim team member cofacilitated every interview. We first met with imams and other leaders of mosques and then used a snowball sample, inviting people at the end of each interview to suggest others to meet, including those whom they respect but with whose perspectives they disagree. We made best efforts to reflect California’s diversity. Our interviewees ranged in age and experience, from young college students to retired grandparents. Seventy-seven of our 104 respondents (74 percent) were in their thirties or forties; we found that these younger and middle-aged persons were most often thinking about meaningful social engagement. Best efforts were made to ensure gender diversity; forty-four interviews (42 percent) were with women. Interviews were with Muslims of African, Arab, European, Latino, South Asian, and Southeast Asian descent, including converts to Islam and Muslims who identify as LGBTQ, who were US-born or foreign-born. Some interviewees attended mosque prayers regularly, while others—whom scholars sometimes label as “unmosqued”—did not.

Interviews took place in twelve counties representing California’s northern, southern, coastal, and central valley regions. All interviews were confidential and semi-structured. They ranged from forty-five minutes to more than two hours, with most lasting about ninety minutes. We asked interviewees to share important moments of choice, challenge or change in their lives, and to what extent religion, law, and the term shari‘a were relevant to those circumstances, decisions, and events. We also asked them to relate other words or concepts to shari‘a and to share experiences, if any, with federal or state legal systems (e.g., lawsuits or interactions with law enforcement) and whether and how shari‘a came up during those experiences. In these ways we were able to assess the extent to which knowledge of shari‘a, and of ban-shari‘a proposals, influenced their behaviors. All interviews were in English, though in many conversations we and our interviewees used Arabic-language words, phrases, and greetings. Visits to mosques, community centers, study circles, workplaces, nonprofit organizations, and homes, along with our recorded interviews, allowed us to appreciate the diverse contexts in which California Muslims work and worship as minorities.

We recorded and transcribed all interviews using N-Vivo software, which allowed us to divide text into searchable categories of codes. We created 375 codes that separated major life decisions and events—including around dating, drinking, marital or adoption choices, and death—from discussions of the legal system, justice, constitutional law, rights, and Islamic law. We also coded for how people experience, perceive, describe, or judge shari‘a. We searched our interview database across these codes and generated reports of common themes across the interviews. This systematic and qualitative analysis allowed us to make sense of how Muslims in our study gave meaning to the term shari‘a and how these diverse meanings informed their understandings of law.Footnote 14

SHARI‘A CONSCIOUSNESS IN PERCEPTION, EDUCATION, AND INTENTION

This section discusses the results of our analysis of how Muslims in our study responded to the rise of Islamophobic discourses of shari‘a as an anti-American form of law. The primary impacts were around the development of a new Islamic legal consciousness: how Muslims perceived shari‘a, educated themselves about it, and then formed an intention to live out shari‘a’s social relevance through a combination of American and Islamic laws. For the Muslims in our study who sought to mobilize or change laws in the United States, legal mobilization began with creating new perceptions of the self as a citizen and then educating oneself and others about religious faith and the meaning of the law itself. But the participants in our study were not taking their concerns to courts of law as much as they were taking them to courts of public opinion and self-consciously internalizing religious and legal norms.

In a cultural milieu of Islamophobia built on negative media representations of Islam, many of the Muslims we met were trying to live ethical lives, to educate themselves and others about Islamic faith and law, and to fight for social justice. A few people we met were inclined to view shari‘a through the lens of national security and counterterrorism—shari‘a as a threat to public order—reinforced by myriad journalists, academics, and pundits. Some of our interviewees, for instance, referred to a limited kind of shari‘a practiced “over there,” in countries that enforce draconian codes of criminal law, gender segregation, or inheritance. These references were often the premise for a meaningful juxtaposition for those who posited a different view of shari‘a in their lives, based on humanitarian and compassionate ethical principles. These contrasting tropes of “good” versus “bad” shari‘a, or unruly versus humane Muslims, are not surprising since they are part of the effects of Islamophobia. As with other forms of racism, Islamophobia is enacted through state power and its dominant culture. Muslims we met were not immune to these processes or to media representations of Islam as a problematically legalistic religion.

Facing racial or religious discrimination, people we met experienced three related and transformative stages of legal and religious consciousness: perception, education, and intention, which may be antecedents to mobilization (Table 1). Across these three stages, a new holistic legal consciousness emerged, tied to the experiences of racism or anti-religious bigotry. The end result was rarely a Muslim claimant filing a court case against an adversary. Rather, it was an attempt by a Muslim person or group to align shari‘a, and the law itself, with concepts that construct a more inclusive ethos of diversity and ethics in daily life and society.

Table 1. Formative Stages of Legal and Religious Consciousness

Perception

Perception is the process of becoming aware of a situation or fact that comes into contact with one’s life. Muslims in our study often first perceived shari‘a—as a term, much less as a theological principle—from a variety of sources, including through family members, mosque sermons, private study, media, or in schools and classrooms domestically or overseas. Younger people consistently reported that they first heard the term shari‘a from what they called “negative” news accounts of Islam or Muslims, particularly after 9/11, and typically centered on Islamic law.Footnote 15 These reports came alongside negative comments they encountered on social media, including Twitter feeds and Facebook posts.Footnote 16

Even among those who had long used or heard the term shari‘a in their homes or mosques, “after September 11th it became more meaningful, because people—non-Muslims, especially—started having these negative views … about ‘creeping shari‘a’….”Footnote 17 A Latina Muslim in her sixties in Los Angeles concurred, “Basically, this word came out not only for me but for the entire Latino community after 9/11.”Footnote 18 One Muslim in the US military said that he heard about shari‘a first from other soldiers “who wanted to kill ragheads.” He lamented that he, too, “bought it” because, in his words, “I didn’t know what I was talking about, either.”Footnote 19 It is not that these Muslim Americans perceived a personal harm or injury as much as they perceived a sense that their fellow citizens, including non-Muslims, saw Islam as excessively legalistic and, thus, potentially morally off-putting. The term shari‘a was linked to the consciousness of a legal “other” produced by the experience of racism and bigotry.

Many of the Muslims we met, including those born in the United States, felt that they had to “earn” their citizenship because the political context openly vilified shari‘a.Footnote 20 “What shari‘a is thought of today [is] cutting off the hand, and … whipping … the adulteress,” said an activist, echoing many of our respondents.Footnote 21 Even popular representations of Muslims turn to tropes of corporal punishment: “When I was in high school I saw … Aladdin, and he steals … something, and the guy brings out his big ….machete [like] he’s ready to chop [Aladdin’s] arm. Like, that was my understanding [of] shari‘a.”Footnote 22

While some Muslims we met tended to reproduce the binary between what they called “bad” and “good” interpretations of shari‘a, more often we found ourselves in conversations in which images of shari‘a spanned the spectrum as people struggled to define it and explain its relevance. Sousan, for instance, a woman who left Malaysia for the United States in her twenties, said she would not “want to be in a situation like in Saudi Arabia, where you cannot drive.” Similarly, she was nostalgic for “the Islam” of her childhood in 1960s Malaysia “before all the fanatics [came] in.” Initially, Sousan associated shari‘a with law—typically around inheritance, marriage, and divorce—as she had learned from her family overseas. But in moving to California and becoming an ethnic and religious minority, her understanding of shari‘a broadened into a term encompassing her everyday concerns. When she settled in California in the 1990s, she wrote a letter to the imam of the local mosque to ask where she could buy halal (Arabic, permissible) foods. The imam invited her to attend a mosque picnic, where she began to build relationships with others and, over the years, she came to understand shari‘a as practices related to prayer, hygiene, hospitality, weddings, and “who’s gonna say the final rites for me?” These questions and practices broke the hold that an “unruly versus humane” binary once had on her thinking.Footnote 23

The creation of a perception that the United States is against shari‘a reminded Muslims whom we met of their status as minorities and of the need to resist false or stereotypical views. Said one college student in southern California, “I like the idea of being a minority. I feel like whenever a religious group is a minority, they’re always stronger…. They hold on tighter for a little bit.”Footnote 24 This ability to “hold on tighter” involves educating oneself and others to investigate what shari‘a—and law itself—means. The next section elucidates this education process.

Education

The previous section described how Muslim Americans we met came to perceive Islam as a cultural and legal problem through depictions that related shari‘a to excessive legalism demonstrated by acts of terrorism, corporal punishment, or the repression of women. This section shows how and why Muslims responded to this perception of shari‘a as contrary to liberal values by educating themselves. Education is seeking information or training, including by studying shari‘a to confirm or challenge mainstream perceptions of it. A particular kind of Muslim American legal consciousness is being formed in private spaces through personal education about shari‘a—not simply as a response to anti-shari‘a discourse but as an effort to understand one’s background and faith and an act of resistance to the discursive production of a violent or oppressed Muslim figure that American law can set right. The result is a growing awareness of law’s elasticity. With their newfound knowledge, the persons we met learned to think as legal or religious scholars, combining historical facts, contexts, analogical reasoning, and proofs to repurpose the stories that had earlier facilitated discrimination.

Many persons we met reported not feeling “expert” in shari‘a, which led to confusion why state legislatures had been trying to ban it.Footnote 25 Some questioned why we even cared about studying shari‘a or about documenting their personal experiences. “We never grew up with the word shari‘a,” an interfaith activist in coastal California told us when asked to describe shari‘a.Footnote 26 Another echoed these comments: “I think I am a good Muslim [because] I want to be more knowledgeable. [But] right now if you ask me about shari‘a, I don’t know anything, except for that little bit … that my grandfather taught me.”Footnote 27

A Personal Shari‘a Education

Studying shari‘a—even under conditions absent discrimination or Islamophobia—is a challenge due to the time and investment involved. A few of our respondents went overseas to study classical Islamic jurisprudence, spending years in the Middle East or North Africa, learning to be proficient in Arabic, taking courses in the language, memorizing the Qur’an, and parsing thousands of the Prophet’s teachings and actions, and centuries of jurists’ interpretations. But many spoke of the difficulty of sustained theological study, particularly in the United States. “We can’t all be scholars,” a college student lamented.Footnote 28 Many had a feeling that shari‘a had something to do with promoting human rights, social justice, or being “a good Muslim.”Footnote 29 But contradictory media coverage led them, too, to study: “If this is Islamic, and it’s [simultaneously] a bad thing, then that can’t be right.”Footnote 30

As more non-Muslim Americans began to talk about shari‘a in the 2000s as a direct or proximate cause of terrorism and the threat of theocratic takeover, those Muslims we met felt the need to learn more about the term. According to one interviewee, “After September 11th, I think a lot of Muslims’ experience changed, and their own need to know more about themselves and what other people think about them changed.”Footnote 31 One respondent lamented that learning about shari‘a from mainstream media, rather than from within the Muslim community, led her to educate herself from sources she could trust: “All that … hate when people say, ‘Oh, they’re imposing shari‘a.’ That’s the only context I’ve heard it, and I haven’t … learned about it from an Islamic perspective.”Footnote 32 What are those trusted sources of Islamic legal knowledge? For the people we met, they included talking with parents, spouses, other family members, friends, and imams, and by engaging in formal study or informal self-education and reading. Some attended weekly halaqas, or study circles. Some of these study circles were by and for women to discuss issues specific to women’s lives. Others were designed for men and women. Halaqas we attended during our research involved informal meetings (often weekly in someone’s living room) to discuss a range of topics, including how to be a better person and how to maintain respect for the poor, elderly, or incarcerated. College-aged students and recent graduates spoke about seeking Islamic legal knowledge by “following” their favorite imams and other religious scholars on Twitter or YouTube—watching recorded sermons and reaching out to them through private chats on social media platforms to ask questions.

Results of Educational Experience

Muslims we met gained new perspectives on shari‘a’s legal and extralegal dimensions. They also highlighted the importance of diverse and even contradictory interpretations of Islamic rules.Footnote 33 Becoming aware of multiple perspectives within religious law also nuanced their understandings of state law—that state actions may be judged by ethical principles beyond the state’s reach. In these ways, the individualism of private study, and coming together in study circles, reveal how purposeful the experience of living in accordance with shari‘a principles has become.

Contrary to dominant representations in the West of an immutable “shari‘a law,” people we met knew or learned that there was no dominant or monolithic view of shari‘a. “My early … exposure to shari‘a was a misappropriation of … what I feel now that the shari‘a really is,” said an African-American graduate student in Los Angeles.Footnote 34 Anti-shari‘a discourse flattened the complexity of law and ethics, and even rudimentary study revealed that shari‘a encompassed much more than criminal law. “You think of [shari‘a as] these [corporal] punishments [but] I [had] never thought about it as how I treat my neighbor, or my parents … or my prayer … or my fasting,” an imam told us.Footnote 35 Although people did not generally use shari‘a in daily vocabulary, they spoke of more specific daily actions guided by shari‘a principles, such as eating clean foods (halal), dressing modestly, and avoiding forbidden (haram) behavior like littering, stealing, or cheating on spouses. These shari‘a practices that they already aimed to do—healthy interactions with others and the environment—became reclassified under the broader label of shari‘a, a term they realized had been hijacked.

Kamila, an attorney in her early thirties born and raised in southern California, offered that in practicing civil rights law,

… Shari‘a comes up [in] how we balance Islamic values with American law and what we’re advocating for…. [W]e live Islam, we understand what shari‘a is, but … the word and concept don’t come up very much … except … Islamophobes putting it out there, or making people afraid of it. [We try to] protect it from extremists inside and outside the religion.

Kamila was clear that pundits and activists had formed shari‘a into a discursive problem against American law. But she also knew that its multiple interpretations complicated the term both among Muslims and between Muslims and non-Muslims. Railing against corporal punishment and the death penalty, she said, “Sometimes what the huduud prescribes—although it may appear to be harsher than what California prescribes—is often comparable.”Footnote 36 Kamila and a few of our respondents explained how corporal punishment in Islam was comparable to California state law, not in the punishment itself but in evidentiary requirements necessary for extreme punishments. Others argued that influential scholars of Islam sometimes interpret the Arabic word qata‘a (to cut) metaphorically, to mean the “cutting” of family ties (typically by isolating the thief) rather than any physical cutting of limbs.Footnote 37 Awareness, investigation, and comparison exhibit the social relevance of shari‘a, informing ethical choices and legal consciousness.

The views people developed on financial affairs, business transactions, and interest-bearing loans (riba) were similarly diverse. Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) generally bans interest-bearing loans due to the burdens they place upon the poor who are asked to return more than they borrowed. But people we met offered a variety of interpretations. For some, Muslims should be free to pay interest if it is common practice in the society where they live.Footnote 38 Others said that prohibitions on interest payments prevent exploitation (e.g., excessive interest or predatory loans), which is different from paying a fair rate of interest to an honest lender, particularly given rising inflation rates. These persons differentiated the letter of the prohibition on interest payments from its spirit.Footnote 39 Others we met explained how they purchased smaller or less expensive homes (such as was possible in California) to pay down loans more quickly and avoid decades of interest payments.Footnote 40

Collectively, the people we met who had educated themselves about shari‘a spoke to the reality of shari‘a’s diversity. Many told us that they did not see a major difference between shari‘a and the US legal system, including the federal Constitution, where no single or monolithic interpretation of its text prevails. This diversity enabled being Muslim in the United States to feel quintessentially American. Shari‘a is “kind of like the Bill of Rights … general principles … applying the Qur’an and Hadith to your personal life.”Footnote 41 Shari‘a became evident in people’s moral vocabulary and changed the meaning of law in public spaces: “On the road, when you’re between work and home, your eyes and ears are not looking at things you shouldn’t be, you are polite to drivers, [obeying] the speed limit,” a lawyer said of how he recalls shari‘a on California’s clogged freeways.Footnote 42 Others commented how tax regulations are arguably shari‘a-compliant: “Some of the laws in the United States fall within shari‘a—like, you have to pay taxes [to help] the poor.”Footnote 43 One Los Angeles-based lawyer who studied Islamic jurisprudence said he “saw connections” between US and Islamic laws.Footnote 44 “There’s no discrepancy,” one went so far as to say, between “the laws of the United States and the principles of fiqh [such as] preservation of the environment.”Footnote 45 Ultimately, a person “could even find shari‘a here applied [when the government is] doing things for the betterment of society.”Footnote 46

If even religious law is elastic, people suggested to us, then state law must also be subject to revision or change. That is, realizing that God’s law is subject to interpretation led to deeper, more sociolegal understandings of state law: “I still believe our [American] constitutional system is one of the better systems, and … it aligns with what we believe as Muslims…. I see Islamic law in the same way, that we have … a set way of looking at the law, but we can, through a process, make changes as we need to [the law]. It’s not static; it’s more living, breathing,” said a social worker.Footnote 47 One young man who had studied Islamic jurisprudence in the Middle East put the result of his education succinctly:

My study of shari‘a showed me that law is not static…. By definition, it should change [with] time and context [and] should adapt in accord with that land. And … that’s part of shari‘a, not to impose medieval law, but actually to adapt to a society…. I only came to that conclusion through my study of … shari‘a.Footnote 48

Paradoxically, populist invocations of a fear of shari‘a led to a renaissance among Muslim Americans in our study about how to create a good society rooted in values. “Religious law has limitations because it’s a prescriptive law. But all law is prescriptive.… There isn’t one particular answer but … that complexity is part of what I try to get across,” a lawyer told us about how she understood law’s elasticity as a result of learning about shari‘a.Footnote 49 Because state law, like Islamic jurisprudence, relies on proofs and logic, an imam told us, his “perception—of what law was—was changing.”Footnote 50 Similarly, when we asked the extent to which her views of the American legal system changed as she learned more about shari‘a, a college student said, “at the beginning I thought there was only one [interpretation], and now I think that there’s more than one way” to interpret law.Footnote 51 Recognizing multiple, competing interpretations means that learning about law, including Islamic law, does not provide clear answers. But the effort motivates one to learn more: “the more I study, the more confused I am. But not in a bad way, you know? [I am] interested and motivated.”Footnote 52

Learning about shari‘a also developed an interpretive, ethical posture. Speaking about the problem of overcrowding in California’s prisons, ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court, a lawyer told us that her personal studies of shari‘a made her “more critical of the faults of our … criminal justice system … [and simultaneously] critical of the way the Muslim-majority countries … are allegedly implementing shari‘a.”Footnote 53 A deeper respect for law also emerged: law became unfixed, “very nuanced, and very diverse [with] a rich history … there isn’t in fact one right answer.”Footnote 54

Intention

Intention is acting with a specific purpose or aim. The Muslims in our study who educated themselves about shari‘a were contesting dominant stereotypes and envisioning shari‘a as an interpretive frame for good deeds. Explaining how learning about shari‘a led to new forms of consciousness and action, one person said acquiring knowledge of the tenets of shari‘a “has made me more respectful of law…. I’m more hesitant to break rules than I may have before … like running a red light or going through a stop sign.”Footnote 55 Other Muslims we met turned to shari‘a when legal frames created or enforced by states, such as human rights or social justice, no longer seemed enough. They repurposed shari‘a when secular frames stopped working for them.

This constructive impact of shari‘a was no more clear than one woman who told us that studying the Qur’an led her to vote to protect same-sex marriage rights when those rights were under threat in California in 2008, saying “my views on gay marriage … changed … because of … shari‘a.”Footnote 56 That Americans vote according to their religious principles is not new. Despite the anti-shari‘a discourse around her suggesting otherwise, studying the Qur’an made her “a lot more merciful…. Shari‘a does a really great job of … ensuring [a balance between] justice and mercy … so that one doesn’t overtake the other and oppress.”Footnote 57

Intentions to act with kindness toward neighbors were based on trust, appreciation, and acceptance rather than on fear, even in the context of systemic Islamophobia: “You see the quality of the people … of their good deeds, their sincerity of religion, and being good to people in general.”Footnote 58 One person informed a cashier that he had been undercharged for a large purchase by 200 dollars. “There’s no blessing” from God, he told us, had he accepted this windfall dishonestly.Footnote 59 A social services agency employee spoke of cleanliness in food preparation not only because it is a legal requirement but also because it is a religious one: “shari‘a emphasizes … cleanliness.”Footnote 60 Put succinctly, mobilization starts with aligning one’s intentions with “healthier choices [to] be a good citizen.”Footnote 61

People also began to see the intellectual work of lawyering as a spiritual gift. “Shari‘a gave me a lot of experience in law … arguments, [and] I came to realize that … you can negotiate” any law, a student of Islamic law told us.Footnote 62 Rather than taking discrimination claims to court, a graduate student said that he decided to enter the teaching profession because learning about shari‘a “changed my entire understanding of the way law is perceived, and that’s one of the main reasons I wanted to start teaching … because … so many people out there … see Islamic law as black-and-white … even Muslims themselves.”Footnote 63

Some interviewees we met contrasted “man-made” laws (either in the United States or in Muslim-majority countries) that were potentially unfair with God-made principles that were oriented toward values like social justice.Footnote 64 For them, a God-consciousness (taqwa, often translated as “mindfulness of God”) informed legal consciousness. This religiolegal consciousness, in the words of one middle-aged professional, opened the “doors of courage … to try other things that I wouldn’t have tried.”Footnote 65 Some of these goals included volunteering to help refugees in America. “The American legal system has flaws in it…. No judicial system is perfect … but we have to improve upon it. We have to work with the legislators … to improve the laws that are out there,” one woman said of her goals to make the United States more welcoming of immigrants.Footnote 66 As dreams that once seemed impossible become possible, people discovered shari‘a as a source of resilience in the face of discrimination or disputes over identity.Footnote 67

Some participants in our study linked an Islamic and an American ethos to challenge flaws of the criminal justice system: “As Muslims, we’re supposed to work against oppression…. It’s my responsibility as an American living here to obey the laws of the United States but to also try to change the ones that … are just wrong or oppressive.”Footnote 68 Others who experienced discrimination began their own personal journeys to understand themselves and the law. “You’re your own mufti (legal scholar),” said one white, male, Muslim lawyer.Footnote 69 “Consult yourself [with] a purity of intentions.” He concluded, admonishing, “Don’t take away people’s ability to choose between right and wrong.”

Shari‘a matters not only because it is part of an anti-Muslim discourse. It is an interpretive frame through which Muslims commit to ethical living. This is not to say that shari‘a is or should be compatible with all forms of social and political life in the United States, in all its diversity. Muslims we met saw the problem not of opposing the nation of America but of opposing a discourse of hate that refuses to assimilate Muslims and Muslim ethics. As legal scholar Sherman Jackson writes, “for Muslims to … bring shari‘ah into blanket conformity with every aspect … of the American state would … undermine Islam’s socio-political significance. After all, if Islam merely confirms every value that secular, liberal democracy produces on its own, it is not entirely clear what Islam’s practical relevance might be and why it should not be privatized” (Jackson Reference Jackson2015, 276). Shari‘a allows for a kind of popular sovereignty where individual persons, through personal autonomy and interpretation of religious faith, collectively participate in the creation and interpretation of state law and nationhood itself.

The people we met for this study developed a sense that law and discrimination induced not just public action but the precursors to action: private identity formation, education, and intention. In keeping with the expectations of liberal citizenship, they defined their experiences of shari‘a largely as aspects of their private lives, influencing their choices to consume, obey traffic laws, and exercise their own religious authority. In these ways, Islam has never been more American, shaped by the individualized demands of political liberalism. In other words, Muslims are interpreting, discussing, and operationalizing shari‘a in multiple ways. It could be around dietary and alcohol choices (e.g., eating halal), consumer purchases, or life rituals (e.g., marriage and burial). The prevailing anti-shari‘a discourse, and the racializing project underlying it, has shaped a counter-discourse of agency for Muslim Americans, which involves a changing legal consciousness characterized by personal analysis of religious norms and American laws. Ultimately, legal consciousness may come from sacred sensibilities and the desire to be a more ethical servant of God and not merely to be a more ethical subject of the state.

Many of the persons we met were already trying to be better people; they did not try to become better people simply because Islam was vilified. While shari‘a may not have been the driving force of their ethical deeds—for instance, dressing modestly or acting with temperance—for many who foreground being Muslim as their defining identity, it consciously has become so, both in their affirmation of American laws and their resistance to injustice. The first steps toward their mobilization lay in how they perceived shari‘a, educated themselves about it, and repurposed their intentions with a consciousness that combines law, religion, and justice.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have tried to show three main points about how shari‘a shapes legal consciousness in the United States. First, populist discrimination against Muslims and Islam saturates everyday experience, and certain depictions of shari‘a and of the US legal system are instrumental for that project. Second, the analysis we presented of Californian Muslim responses to anti-shari‘a populism demonstrated the importance of studying how religious minorities experience and learn particular lessons about the intersection of law and faith. Third, Muslims we met educated themselves about faith, law, and rights in order to be better positioned to lead ethical lives in the context of a broader fear of shari‘a. The othering of Muslims emerged in part when people defined shari‘a narrowly as criminal law. But when Muslims faced inequality, shari‘a became a guide to ethical living.

Far from making unreasonable or illiberal demands on American society, as alarmists depict, the Muslims in this study did not expect shari‘a to be implemented as such into US law. Instead, many consciously followed shari‘a principles to answer everyday life questions, including around finances, marriage and divorce, dietary restrictions, and how to treat the environment. Our respondents were reflective about the place of shari‘a in their lives and the impact of shari‘a on their interactions with a dominant, non-Muslim society.

According to a study released by the Institute for Social and Public Understanding, a nonprofit think tank, 42 percent of Muslims with school-aged children reported their children experienced bullying because of their faith, compared to 23 percent of Jewish and 20 percent of Christian parents (Mogahed and Chouhoud Reference Mogahed and Chouhoud2017, 4). A 2018 survey by the Council on American-Islamic Relations revealed that 53 percent of California’s Muslim youth between the ages of eleven and eighteen reported being bullied over their religion—more than twice the national average. And a child in Ventura, California, reportedly missed several days of school in 2017 “because he was afraid of his teacher and classmates” after his teacher printed and handed to him a website detailing “so-called aspects of Islamic Sharia … including how a man could marry an infant … and that [he] has ‘sexual rights’ over a woman who is not wearing a hijab” (Bharath Reference Bharath2018). For Muslim youth, bullying is the new norm, with their tormenters using shari‘a as a cudgel or weapon of shame against them.

The critique of Islam embedded in this type of legalistic bullying around shari‘a has, in part, animated Muslim Americans’ efforts to shift the discourse or to ensure continuity with an American ethos. Many of the Muslims we met engaged Islam (and shari‘a as a part of Islam) because of what they argued was its flexible and accommodating nature and its inherent compatibility with a liberal ethos. Their concerns about shari‘a dovetailed with concerns over authority, inclusion, and justice. More to the point, we found shari‘a consciousness to reproduce normative authority rather than simply pronounce ethical standards. The people we met were attuned to the obligations and logics of multiple, overlapping communities.

Non-Muslim American interest in shari‘a has largely been triggered by a fear that it constitutes a challenge or even a threat to Americans’ shared identity and values. Electoral politics, the far right, and mainstream media, for instance, continue to warn about the dangers of “creeping shari‘a.” But there is no empirical evidence to show that shari‘a is supplanting civil or criminal law in the United States. Negative portrayals of shari‘a have long been associated with terrorism and the most extreme forms of corporal punishment, which was a source of great frustration for Californian Muslims in our study. The blame fell on the media and politicians for having framed a national discourse in ways that misrepresented shari‘a in order to elicit Islamophobic sentiment. Despite this, many of the people we interviewed were able to live in accordance with shari‘a principles around life, liberty, and the protection of family and faith.

Muslim Americans are not alone in shaping legal consciousness through attention to shari‘a. In Nigeria, India, and Egypt, among other places, colonial legacies and postcolonial violence and marginalization have triggered support for shari‘a when governments seem unwilling to provide basic security and freedom from injustice (see, e.g., Eltantawi Reference Eltantawi2017). As democratic political systems collapse into populism, people may begin to rely on shari‘a or what they identify as religious law more broadly as a means for law and order, operating outside of but in dynamic relation to state courts (Lemons Reference Lemons2019).

For the authors of this study, participating in this research has created space for us to see the category of shari‘a as a matter of comparative law and society studies. The intersection of sociolegal and religious studies marks out a complex, multilayered, and shifting terrain in which shari‘a is a referent for legal consciousness, an object of public policy, and an administrative concern, simultaneously separate from the state and mediating the relation between state and citizen. By following the nexus of legal consciousness and lived religion, our accounts of the perceptions and behaviors of some Muslims in California shed light on transformations that occur in legal and religious consciousness, particularly when minorities are subjected to entrenched forms of discrimination. Without an adequate understanding of how Muslims experience law, and how the concept of shari‘a is deployed to disguise or justify inequality, we are left with conditions that fuel greater anxiety and othering. This process has implications for how Muslims, as subjects of discourse, rework the narrative of US law.

Future research is needed to examine additional vantage points of the othering of Muslims, and how Islam is changed through the law itself, not only in deployments of shari‘a in political discourse but also in legislative remarks and bills. Doing so would continue to develop interdisciplinary approaches to law and society that draw upon the relationship between religion, law, and populism. Muslims in the United States live and work within “not only an imagined Islam but a contrived America,” and neither are free from suffering and discrimination (Jackson Reference Jackson, John and Kalin2011b, 96). Many Muslim Americans react to anti-Muslim discourse like ban-shari‘a legislation as an annoying if not life-threatening aberration in the political sphere. This response generates self-study of faith and law, as well as self-study of how to construct ethical frameworks to navigate the boundaries between state law and private intentions. While many of our respondents expressed concern that lawmakers and the broader public just “didn’t get it,” their efforts to bring together law and faith underscore how religiosity shapes both the liberal subject and the legal mobilizer.