Hierarchy and stratification characterize labor markets all over the Western world. Racial, ethnic, and national minorities; women; and those belonging to lower socioeconomic classes are underrepresented in prestigious positions and overrepresented in lower-paying jobs in proportion to their percentage in the general population. Even when employed in similar positions, members of devalued social groups earn lower wages and are promoted less frequently. The legal profession is no different. Decades of research have clearly shown that the market for legal services follows the same patterns that determine the outcomes in other domains of social and economic life (see, e.g., Reference CarsonCarson 2004). Yet in the spirit of Tolstoy's famous maxim, while all egalitarian labor markets are alike, each hierarchical market is stratified in its own way. Stratification is based on numerous distinctive characteristics such as the legal profession's structure, size, and degree of homogeneity, as well as the regulations governing it and the legal culture it exists in. Likewise, factors related to the general social structure—such as the stratification in broader society and the social role of the legal profession—also affect stratification within the legal profession. In this paper we seek to contribute to the literature on hierarchy and stratification within the legal profession through an in-depth examination of the patterns of inequality in the Israeli legal profession.

Israel is a particularly interesting case study due to the rapid and inordinate transformation the Israeli legal profession has undergone over the past two decades. The Israeli legal field comprised a small, homogenous, and closed profession until the 1990s, but doubled in size every decade since; today, Israel holds the dubious title of the country with the highest rate of lawyer per capita in the world. Thus, examining patterns of inequality within the Israeli legal profession can shed light on the ways in which systems of inequality reproduce themselves under conditions of dramatic social changes, such as the massive recent growth in the number of lawyers.

Up until the mid-1990s, the Israeli legal profession was virtually blocked to large segments of the population. Accredited law schools existed only at four universities; consequently, the average number of law graduates admitted annually to the bar between 1948 (when the state was established) and 1994 remained steady at 337 (Reference Zer-GutmanZer-Gutman 2012). Resultantly, only an elite group of people could become lawyers in Israel. The early 1990s witnessed a revolution in legal education. On the supply side, a shift in the regulatory regime enabled the opening of many new law colleges—professional schools that operate independently of the research universities. In conjunction, a growing demand for legal education resulted in a sharp rise in the number of lawyers during a very short period of time. As of 2016, 14 law schools operate in Israel: four in universities and 10 in colleges. Whereas in 1990 there were only 10,697 lawyers, currently, 64,000 lawyers are registered with the Israel Bar Association: one lawyer per 132 people (Reference ZalmanovitshZalmanovitsh 2017). This ratio is likely to grow (although perhaps at a slower pace), since every year approximately 3,000 law graduates are licensed as lawyers.

The accreditation of law colleges during the 1990s and the early 2000s led to a dramatic change in the composition of the Israeli legal profession. Population groups previously largely excluded from the profession—which traditionally was dominated by males of Ashkenazi (European Jewish) origin—are increasingly gaining entry. Women, Arabs (i.e., Palestinian citizens of Israel), Jews of Mizrahi (North-African and Middle-Eastern) origin, and ultra-Orthodox Jews now comprise a large proportion of the profession. Since the annual number of law college graduates greatly exceeds that of the university law school graduates, and the former tend to be of lower socioeconomic status than the latter, the social and cultural elite's domination of the legal profession has been disrupted. Some view this transformation as destructive to the profession (Reference KatvanKatvan 2012), while others have welcomed it as a change that better reflects Israel's heterogeneous society (Reference Zer-GutmanZer-Gutman 2012). Yet neither of these views is informed by any sound data and systematic analysis of the actual impact of such transformation on patterns of hierarchy and stratification in the Israeli legal profession.

In this article we seek to fill in the research gap regarding the Israeli legal profession through a comprehensive, systematic evaluation of the trends of inequality and stratification that occurred following the sharp increase in the number of lawyers. We investigate whether inequality and stratification in the Israeli labor force are predetermined so that they are maintained and reproduce themselves even in times of social and economic changes, like the dramatic increase in the size of the bar.

In the American context, research drawing on interviews with Chicago lawyers has shown that the increasing overall size of the bar in general, and the growing number of women and minorities in the bar in particular, led to a stratified legal profession on the basis of gender, race, and religious background (Reference HeinzHeinz et al. 2005). More generally, studies revealed that patterns of inequality tend to recreate themselves through numerous complimentary processes, resulting in persistent inequality even in times of technological, social, or demographic changes (Reference ReskinReskin et al. 1999; Reference Ridgeway and CorrellRidgeway and Correll 2000; Reference RidgewayRidgeway 2011; Reference RismanRisman 1998). Our focus on the case study of the Israeli legal profession thus contributes to the literature that demonstrates how systems of inequality are reproduced in times of structural changes.

We designed a large-scale survey of graduates from university law schools and law colleges between the years 1995 and 2015; 6,639 graduates responded (a response rate of 15 percent). An analysis of the responses to the survey exposes the changes in the legal profession, demonstrating that despite its openness to previously excluded population groups, the profession remains deeply hierarchical and stratified. Male Ashkenazi university graduates continue to secure the most lucrative jobs in the private and public sectors. They earn more than women, non-Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and college graduates, reflecting the ongoing entrenchment of gender, nationality, ethnic, and class-based hierarchies existent in the general Israeli labor market.

Because our study is the first to explore these issues systematically, and given our sample size, we focus here on the gender, nationality, ethnicity, and class inequality systems without exploring how these systems intersect with each other to create additional categories of stratification and inequalities (like in the cases of Arab women or lower-class Mizrahi Jews). We leave questions related to intersectionality in the Israeli legal profession for future studies.

Hierarchy and Stratification in the Legal Profession

Contemporary literature on inequality, hierarchy, and stratification in the legal profession distinguishes between two stages: entry into the profession and the conditions of law practice. Below, we survey studies covering both stages and relating to different forms of discrimination in different jurisdictions.

Gender

Studies in the United Kingdom and United States have found that in the last decades, external occupational barriers that had traditionally excluded women from entering the legal profession have been reduced or completely removed, such that the scholarly discussion has shifted focus to the feminization of the profession and to the strides women lawyers have made in the field (Reference Abel, Abel and LewisAbel 1988; Reference Dinovitzer, Garth, Sarat and EwickDinovitzer and Garth 2015; Reference Dixon and SeronDixon and Seron 1995; Reference TsangTsang 2000). These changes are largely attributed to reforms in legal education. Opportunities internal to the legal profession, however—such as promotion to partnership, appointment to prestigious positions, and equalization of pay—remain barred or extremely limited by powerful gender-exclusionary mechanisms and result in a gendered professional environment in which women fair worse than men (Reference Bolton and MuzioBolton and Muzio 2007).

Wage disparities between women and men in the legal profession have been documented in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom (Reference Dixon and SeronDixon and Seron 1995; Reference HaganHagan 1990; Reference HuangHuang 1997; Reference Kay and HaganKay and Hagan 1995; Reference Rachman-MooreRachman-Moore et al. 2006). According to Reference Bolton and MuzioBolton and Muzio (2007), in the United Kingdom, exclusionary mechanisms function through processes of stratification (denial of access to senior positions), segmentation (channeling women to practice areas that generate less income), and sedimentation (utilization of feminine skills in the professional work of female lawyers). Reference Rachman-MooreRachman-Moore et al. (2006) suggested that psychological, human, and social capital, alongside occupational segmentation, explain gender-based earning disparities. Reference Kay and GormanKay and Gorman (2008) traced gender disparities in the legal profession in the United States to variables such as a gendered law school experiences, differences in the career entry and hiring stages, patterns of sex segregation in practice, sexual harassment, and work/family conflicts. Moreover, Reference Hagan and KayHagan and Kay (2007) showed that women are more likely to respond to their professional grievances and challenges with feelings of despondency than with expressions of job dissatisfaction.

Racial Minorities

The literature on race and the legal profession points to barriers faced by racial minorities both at the entry stage and in career development. In the United States, findings indicate that minority lawyers are less likely to be hired at a private law firm as their first job; they tend to work at smaller firms when they do enter private practice; and they are less likely to become partners than White lawyers. Thus, despite of the increase in the numbers of Black lawyers and judges since the early 1970, the percentage of Blacks in the bar remains lower than in the general population, and Black lawyers are less likely to be employed in higher-status legal positions or as partners (Reference CappellCappell 1990; Reference Payne-PikusPayne-Pikus et al. 2010). Mechanisms producing such disparities include direct discriminatory patterns, such as less mentorship and indirect ones such as fewer networking opportunities (Reference Dinovitzer, Garth, Sarat and EwickDinovitzer and Garth 2015; Reference WilkinsWilkins 1999).

Studies on minority lawyers in the United Kingdom (labeled “BME” or “Black and Minority Ethnics” lawyers) have also indicated the persistence of inequalities despite their increased entry into the legal profession. BME lawyers are overrepresented in small firms and legal aid, while White male lawyers are overrepresented in the highest-paying jobs in large urban firms following their graduation from the elite universities (Reference NicholsonNicholson 2005; Reference ZimdarsZimdars 2010). Reference TomlinsonTomlinson et al. (2013) describe how BME lawyers apply a series of “career strategies” (assimilation, compromise, “playing the game,” reforming the system, location/relocation, and withdrawal) in contending with structural barriers to equality in the profession.

Social Class

For decades, the question of the possible impact of social class on success in the legal profession has captured the attention of both critical scholars and empirical researchers. In the United States, early studies by Reference CarlinCarlin (1966) and Reference AuerbachAuerbach (1976) described a professional elite using closure mechanisms to exclude racial, ethnic, and religious minorities from the organized bar. A Study on lawyers in Chicago (Reference Heinz and LaumannHeinz and Laumann 1982) demarcated “two hemispheres” of lawyers—those working for corporations and those serving individuals—and found that the former were more likely to be White, Protestant males. And Reference KennedyKennedy (1982) claimed that legal education produces and reproduces social hierarchies through teaching methods, institutional culture, and value-laden legal doctrines.

The correlation between the law school attended, social class, and professional mobility has also been the subject of broad investigation. Regarding the Reference DalyUnited States, Daly (2002) claimed that “[t]he identity of the institution from which a graduate receives the J.D. degree may be the single most important factor in the graduate's career path,” reflected directly in the marketplace for legal services. Reference JewelJewel (2008) traced the historical roots of law school ranking and classification systems in the United States, which have led to the establishment of an “underclass of American attorneys—with no autonomy, no contact with clients, no job security,” reinforced by a “myth of merit.” Although research has shown that overall, the premium yielded by a law school degree is higher than that of both a humanities degree and a science and technology degree (Reference McIntyre and SimkovicMcIntyre and Simkovic 2016; Reference Simkovic and McIntyreSimkovic and McIntyre 2014), differentiations between elite law schools and low-tier law schools seem to persist over time (AJD3, 46-47). Interestingly, satisfaction levels among graduates of elite law schools are lower than they are among graduates of lower-tiered schools (Reference Dinovitzer, Garth, Sarat and EwickDinovitzer and Garth 2015).

Social class was revealed to be a substantial factor in law school enrollment (Reference StevensStevens, 1983). Moreover, as discussed above, the status of law school attended affects the future careers of law graduates (Reference Sander and BambauerSander and Bambauer 2012). Yet, Reference Sander and BambauerSander and Bambauer (2012) showed that grades in law school mitigate the effects of law school status and similar trends were also found in the United Kingdom (Reference NicholsonNicholson 2005). The Canadian structure of law schools is somewhat different, barring comparison on this issue to the United States and the United Kingdom.

Inequality in the Israeli Labor Market

Two major national groupsFootnote 1 comprise Israeli society: Jews account for 75 percent of the population and Arabs constitute 21 percent (the rest are non-Arab Christians and “unclassified” residents) (Central Bureau of Statistics [CBS] 2017). Both large groups are internally fragmented along religious and ethnic lines. “Arabs” include Muslims (16.5 percent), Christians (2.1 percent), and Druze (1.7 percent), whereas “Jews” subdivide into two large ethnic groups: Ashkenazi Jews of European ancestry (55 percent) and Mizrahi Jews of North African and Middle Eastern ancestry (45 percent).Footnote 2

The Israeli labor market is segregated by gender, ethnicity, and nationality. Similarly to other Western countries, Israeli women participate in the labor force in growing numbers. In recent years, women have entered more high-skilled and previously male-dominated positions in the professional and managerial sectors. Nonetheless, many women in Israel still work in different occupations than men do, and tend to earn less than men when employed in the same occupation (Reference Mandel, Birgier and KhaṭṭābMandel and Birgier 2016). In the years 2012–2014, Israeli female workers’ average hourly wage amounted to approximately 83.7 percent of the average hourly wage of Israeli male workers (Reference SwirskiSwirski et al. 2015). Mizrahi Jews are disadvantaged relative to their Ashkenazi counterparts in terms of both hiring and wages (Reference Rubinstein and BrennerRubinstein and Brenner 2014; Sasson 2006); indeed, in 2012–2014, the average monthly wage of Mizrahi Jews amounted to approximately 78.2 percent of that of Ashkenazi Jews (Reference SwirskiSwirski et al. 2015). Likewise, Arabs in Israel face labor market disadvantages relative to the Jewish population. Arab citizens live and work in areas with limited industrial and occupational opportunities, indicating that a substantial proportion of the income gap between Jews and Arabs can be attributed to local labor market characteristics (Reference Lewin-Epstein and SemyonovLewin-Epstein and Semyonov 1992). In 2012–2014, Arab Israelis’ monthly wage on average was 21 percent lower than the Israeli average monthly wage (Reference SwirskiSwirski et al. 2015).

Another factor perpetuating inequality in the Israeli labor market is the level and type of higher education, as well as parents’ education. Jewish first- and second-generation higher-education studentsFootnote 3 tend to study more rewarding and prestigious professional fields than Arab students—albeit at different types of institutions. First-generation students tend to study at second-tier institutions (i.e., colleges), whereas second-generation students often attend the more prestigious universities. First-generation Arab students, like their Jewish counterparts, prefer the professional fields as well; but unlike their Jewish peers, they tend to be concentrated in less prestigious professions (Reference Ayalon, Mcdossi and KhaṭṭābAyalon and Mcdossi 2016).

The Transformation in the Israeli Legal Profession

As noted above, the Israeli legal profession underwent a radical transformation since the mid-1990s; the number of law graduates rose as new law colleges opened. This growth coincided with the liberalization and expansion of the Israeli market economy that took place since the 1980s. Lawyers have both benefitted from and contributed to Israel's globalizing economy. Reference ZalmanovitshIndeed, Zalmanovitsh (2017) reports that the revenue of Israeli law firms rose from around 11.1 billion ILS in 2009 to a whopping 16.1 billion ILS in 2016. Globalization created a demand for legal services and affected the structure and scope of the legal profession (Reference Barzilai and FeeleyBarzilai 2007: 255–256). Moreover, as mentioned above, the vast majority of recent law graduates studied at one of the relatively new second-tier colleges, rather than at one of the four more prestigious university law schools. In 2012–2013, for example, approximately 13,000 students were enrolled in law colleges and only 3,000 in universities (Reference KatvanKatvan 2012; Reference Zer-GutmanZer-Gutman 2012; Reference ZivZiv 2012, Reference Ziv2015).Footnote 4

A number of factors led to the increase in the number of law schools and of lawyers in Israel. Already in the early 1990s, both the Israel Bar Association (IBA) and the university law schools faced mounting pressures to “open the doors” of legal education to more people. The official claim was that the existing arrangement amounted to numerus clausus, resulting in the exclusion of under-privileged segments of Israeli society from legal education. The unofficial (and uncorroborated) story, on the other hand, is that some children of senior partners at elite law firms were refused admission to Israeli law schools, thus compelling the guild's “insiders” to support its expansion. Be that as it may, around 1990, both the IBA and university law schools collaborated to amend the Israel Bar Association Act to enable the establishment of professional law schools, alongside the academic institutions and subject to their monitoring and approval.Footnote 5

Within a few years, it became clear that the universities’ attempt to “tame the beast” and curb competition to their own law schools had failed miserably. At this stage, however, it was already too late to reverse the process. The demand for legal education was on the rise, as was the call to liberalize legal education. In 1995, the Israeli parliament (the Knesset) amended the Council of Higher Education Act, allowing the accreditation of private colleges to award law degree. The removal of numerous regulatory barriers further enabled the opening of many new law colleges since the mid-1990s (Reference Ben-Yaakov and LandauBen-Yaakov 2000). This system sustains itself, as significant economic incentives exist for establishing a private law school. Running a law school requires relatively little investment, whereas demand for legal education remains rather high, and law colleges charge tuition that is double or triple that of universities (Reference KatvanKatvan 2012). On the supply side, a growing number of Israeli law graduates obtained a doctoral degree abroad (mainly in the US), and upon return to Israel found an employment opportunity in the emerging field of legal education. Likewise, retired law faculty members of Israel's universities have attained high paying teaching opportunities at these schools.

The opening of the law colleges accomplished a diversification of both the law student population and the legal profession. These colleges enabled access to law studies to population groups that had been excluded from the university law schools. Reference KatvanKatvan (2012) noted that the colleges tend to attract older students, who are more likely to be married and have children. There are also fewer students in law colleges whose parents have an academic education, implying a lower socioeconomic status. Moreover, many more Arabs, ultra-Orthodox Jews, and Israelis of Ethiopian origin study at law colleges than at universities (Reference KatvanKatvan 2012). Reference Zer-GutmanZer-Gutman (2012) pointed to the growth in the number of both lawyers and law firms in the Israeli geographic periphery since the opening up of law colleges, which she attributes to greater opportunities for residents of these areas to attain a law degree.

Unsurprisingly, the sharp increase in the number of law graduates propelled the IBA to try to tighten entry barriers into the profession (Reference KatvanKatvan 2012; Reference Zer-GutmanZer-Gutman 2012; Reference ZivZiv 2012, Reference Ziv2015). For many years, those initiatives were largely unsuccessful due to a fierce opposition from the Knesset, the Ministry of Justice, and the law colleges and their students, who were averse to implementing a broad reform that would reverse or halt the influx in the number of lawyers (Reference ZivZiv 2015). Since 2015, however, the tides have changed, probably as a result of the strengthening of the IBA and its close political alliance with the Minister of Justice. Two substantial changes emerged. First, in the last three consecutive years, the passage rate of the bar exam—a prerequisite for practicing law—has fallen sharply, exposing a significant gap between the pass rates of college graduates and university graduates. In October 2014, for example, 70 percent of those who took the exam passed it; the two top universities (Tel Aviv University and the Hebrew University) ranked highest, with a pass rate of over 97 percent, while the lower-tier law colleges had a pass rate of about 60 percent (The Israel Bar Association 2014). In 2015, the overall pass rate fell to 59.7 percent. The two top universities again ranked highest, with a pass rate of approximately 95 percent, in contrast to 45 percent for the lower-tier colleges (The Israel Bar Association 2015). The same trend continued, and even intensified, in 2016 and 2017 (with a general passage rate of below 50 percent). Second, in 2017, the IBA successfully lobbied to amend the IBA Act, extending the mandatory apprenticeship—a prerequisite for sitting the bar exam—from 12 to 18 months.Footnote 6 It is too early to predict, however, whether these changes will affect the demand for legal education and the rate of new lawyers entering the profession.

Thus, the state of the Israeli legal profession is highly dynamic and in constant flux. The transformations in the legal education and the increase in the number of lawyers are commonly perceived to have propelled a decline in the profession's prestige, but no previous study attempted to quantify this effect (which is very hard to assess). In any case, the decline in prestige is probably not evenly divided across all types of lawyers; Most Israeli lawyers (about 75 percent) work in private law firms at some stage of their careers; some turn to the public sector, and a small number of lawyers (a few hundred at most) work in NGOs. The private, public, and nonprofit sectors themselves are not monolithic both in terms of pay and prestige. Working in mega law firms is more financially rewarding and prestigious than working solo or in small law firms, but in some segments of the profession—such as family law and employment law—small boutique firms abound and are considered quite prestigious. In the public sector, working as a state attorney (while less financially rewarding than working at large law firms) is considered highly prestigious, whereas working as a lawyer at local governments is much less prestigious. Lawyering for NGOs, although not financially rewarding, is nonetheless recognized as a status-worthy career choice (Reference ZivZiv 2015).

Methodology

Data collection for this study was based on an anonymous email survey. Respondents were asked to supply information about their job (firm size and number of weekly working hours), fields of expertise, law school background, and demographic characteristics (nationality, ethnicity, religion, marital status, number of children, etc.). Respondents were also asked about their current work positions, including scope of employment (full-time, part time, or unemployed), and their salaries and other benefits. Lastly, they were asked to report on their level of satisfaction with their decision to have gone to law school and to share their future plan.

We attempted to distribute the survey to all those graduating from law schools at all the Israeli legal educational institutions (universities and colleges) between 1995 and 2015. We chose this timeframe because one of the central goals of our research was to understand the state of the Israeli legal profession after the mass accreditation of the law colleges and the ensuing upsurge in the number of law graduates. The year 1995 was the graduation year for the first group of students who had studied in law colleges rather than at university law schools.

The survey was distributed in two phases. In the first phase, which was carried out in collaboration with the IBA, the survey was sent to all law graduates admitted to the bar between 1995 and 2015. In Israel, current membership in the IBA is a perquisite for practicing law. The IBA maintains two databases: one for active bar members—namely, registered lawyers who pay annual fees; the second for all lawyers who had at some point entered the bar, some of whom no longer pay the annual fees to the IBA (and are therefore prohibited from practicing law). The total number of email recipients on both lists was about 45,000. Following the initial distribution of the surveys, nonrespondents were sent a second email with the survey a few weeks later.

The second phase of the survey distribution was conducted in partial collaboration with the law schools. We sought to reach not only practicing lawyers but all law graduates, including those who did not take or pass the bar exam, those admitted to the bar who have never practiced law (either willingly or due to employment constraints), and those admitted to the bar who at some point left the profession and did not update their email address with the IBA. Deans of all the university law schools and law colleges were asked to: (1) supply us with the number of annual law graduates from their institutions between 1995 (or the year in which the first class graduated) and 2015; and (2) distribute our survey to their graduates via their alumni mailing lists. All but three of the 14 institutions agreed to both requests. This process yielded responses from additional few hundred lawyers.

To avoid double counting, we specifically instructed law graduates who had received the survey from both the IBA and their academic institution not to respond to the survey twice. Then, after gathering all the surveys, we searched the entire list for duplications in email addresses supplied by the respondents, striking out responses when the same email address appeared twice on our lists. To increase the survey response rate, respondents were offered the incentive of entry in a raffle for prizes, such as restaurant vouchers.

At the end of the second phase, 6,639 respondents had answered the survey. When compared with external data—including data obtained from the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, data obtained from the universities and law colleges, and the IBA yearly reports on bar exam pass rates for each institution—our sample emerged as representative of the general population being surveyed in terms of gender, ethnicity, and type of law school attended. However, Arab law graduates are underrepresented in our sample.

Our study has some limitations. Notably, the response rate to the survey was of about 15 percent of the people to whom the survey was distributed. The After the JD (AJD) and the Law and Beyond: A National Study of Canadian Law Graduates (LAB) response rates were higher. However, the present study differs from the AJD and LAB studies in both scope and methodology. The AJD was based on a sample of 5,000 lawyers from different geographical areas encompassing only lawyers who entered the profession in the year 2000. The LAB surveyed all lawyers admitted to the Canadian bar in 2010. Our sample, on the other hand, included all law graduates—whether practicing or not—who graduated between the years 1995 and 2015, numbering about 45,000 people.

Naturally, it was much harder to trace those who graduated many years before the survey was conducted and get all or most of them to complete it. To overcome this limitation, we compared the demographic characteristics of the respondents to our survey with the entire population of law graduates in the years 1995–2015, using data obtained from both the IBA and the law schools. The comparison confirmed that our sample is unbiased in terms of both the gender and ethnicity of respondents and the type of law school they attended. Therefore, we are confident that the response rate does not affect the validity of our findings regarding these variables. We did find, however, that our sample is biased with regard to Arabs, who are underrepresented in our dataset. Thus, further research is needed in order to verify and better understand the findings regarding the career patterns of Arab law graduates.

Our methodology aligns with recent studies suggesting that lower response rates do not necessarily generate meaningful differences in the accuracy of measurements, if measures are taken to ensure that the respondents represent the surveyed population (Reference CurtinCurtin et al. 2000; Reference Holbrook and LepkowskiHolbrook et al. 2007; Reference VisserVisser et al. 1996). In one notable meta-analysis, the effects of low response rates on the demographic representativeness of the samples were explored in 81 national surveys with response rates ranging from 5 percent to 54 percent. The study found that lower response rates generated only small differences in the demographic representativeness of the samples (Reference Holbrook and LepkowskiHolbrook et al. 2007).

Another limitation of our study is that we lack data about the geographical location of our respondents’ practice. Due to the nonrandom distribution of respondents across Israel in terms of both nationality and ethnicity, we cannot rule out that some of the findings—especially those related to salary—are driven by the respondents’ geographic location rather than by their nationality or ethnicity. We further discuss this limitation below and demonstrate that at least with regard to ethnicity, it does not affect the validity of our findings.

Data and Results

A total of 6,639 law graduates responded to our survey. Of these, 52 percent were women, 3.3 percent defined themselves as Arabs, and 95 percent identified as Jews. Among the graduates who defined themselves as Jewish, 52 percent identified as Ashkenazi, 25 percent as Mizrahi, and the remainder as either “Mixed Ethnicity Jewish” or “Other.” 42 percent of all respondents are university graduates, while 58 percent are graduates of law colleges.

Tables 1 to 5 present the variables we used in our analysis of the data. These variables were presented first generally for all the respondents in our dataset and then by gender, ethnicity, nationality, and type of law school attended. “University graduate,” “works in the profession,” and “works full-time” are dummy variables, generated by the respondents’ answers to questions about their status. Salary is a categorical variable constructed based on respondents’ answers to a question regarding their monthly salary. It includes ten pay-level categories, ranging from less than NIS 10,000 (approximately $2,600) monthly to more than NIS 50,000 (around $13,200) monthly.Footnote 7 “Satisfied with having gone to law school” is a variable constructed based on respondents’ answers to the question, “On a scale of 1–5, how satisfied are you with having gone to law school?” (1 = not satisfied at all and 5 = very satisfied).

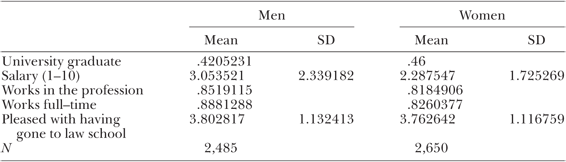

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics by Gender, After the LL.B

As noted, about half of the respondents in our dataset are women; around half are Ashkenazi Jews; and only around 3 percent are Arabs. Most of the lawyers in our dataset tend to work in the private sector.

Table 2 shows that on average, female respondents were more likely to be university graduates (as opposed to graduates from a law college) than male respondents. Women are less likely to work in the profession or to work full-time in the profession; they also tend to earn less and to be less pleased with their decision to have gone to law school than men.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics by Gender, After the LL.B

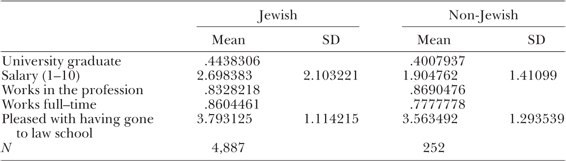

Table 3 reveals that a relatively small number of non-Jewish law graduates (the majority of whom identified as Arabs) responded to our survey. Notably, however, there is little reason to assume a selection bias among Arab respondents.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics by Nationality, After the LL.B

Table 3 also shows a lower tendency for Jewish lawyers, compared to their non-Jewish counterparts, to work in the profession; but among those who do, a greater tendency to work full-time. In addition, Jewish respondents tend to earn more and be happier with their decision to attend law school.

Table 4 compares Ashkenazi Jewish law graduates in our sample to graduates from all other Jewish ethnic groups. It reveals that compared to their non-Ashkenazi counterparts, there is a greater tendency for Ashkenazi Jews to have graduated from university rather than colleges and to be pleased with their decision to have attended law school. While they tend to work less in the profession, on average they earn more and are more likely to be employed full-time.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics by Ethnicity (only Jewish), After the LL.B

Lastly, Table 5 shows that compared to law graduates who studied at colleges, the university graduates in our sample tend to work less in the profession and be less happy with their decision to have attended law school. However, they are likely to earn higher salaries and more likely to be employed full-time.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics by Type of Law School, After the LL.B

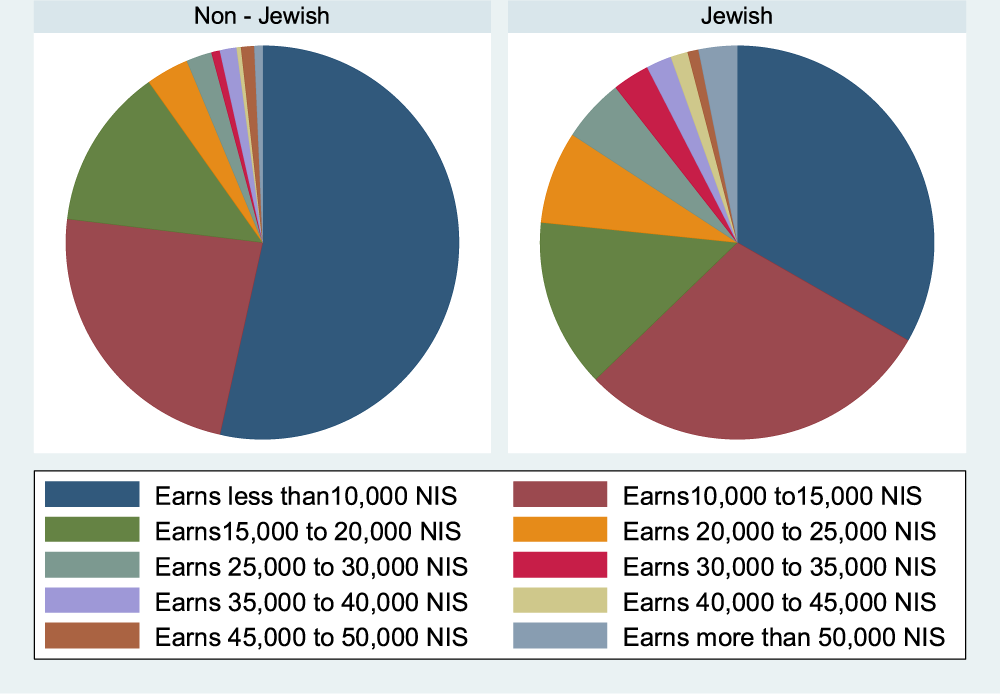

The women in our sample who work in the legal profession tend to earn less compared to their male counterparts (Figure 1). To predict the salaries of respondents, we used multinomial regression models, in which demographics, experience, specialty, education, and employment conditions were controlled for. We found that women earn less than similarly situated men (Table 6, model 1; p < .001).

Figure 1. Monthly Salary by Gender, After the LL.B.

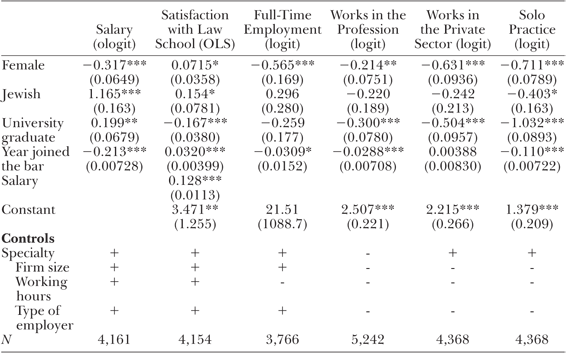

Table 6. Regression Models Predicting Employment Outcomes, by Gender, Nationality, and Type of Law School

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses, +p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

A logistic regression model predicting full-time employment suggests that women in our sample who work in the profession are less likely to be employed full-time and tend to work fewer hours compared to otherwise similarly situated men (Table 6, model 3; p < .05). In addition, women lawyers in our sample have a lower tendency to remain in the profession and tend to be employed more in the public sector and less in solo practice compared to men of similar education, ethnicity, and nationality (Table 6, models 4, 5, and 6; p < .01).

To better understand the mechanisms that generate salary differences between the women and men in our sample, we ran additional regression models predicting the salary of respondents, by the interaction between gender and family status (Table 1A in the Supporting Information) and gender and experience. The analysis suggested that women start out with lower salaries than men, but over time as the workers gain experience, the gap narrows for those who remain in the profession. Similarly, whereas men enjoy wage premiums for cohabitating with a partner and becoming parents, women are penalized for cohabitating but not for becoming parents.

Although the descriptive statistics suggested that on average women are less satisfied with their decision to have attended law school compared to men, an OLS regression model predicting satisfaction with having gone to law school among those graduates who remained in the profession revealed that women tend to be happier with the decision to enter the profession compared to men with similar experience, specialty, education, and employment conditions (Table 6, model 2; p < .05).

Nationality

The Jewish respondents who work in the legal profession earn more than their non-Jewish counterparts (Figure 2). In multinomial regression models predicting salaries, being Jewish correlated with higher salaries (when demographics, experience, specialty, education, and employment were held constant; see Table 6, model 1; p < .001). Jewish law graduates who work in the profession also seem to be more satisfied with their decision to have attended law school compared to similarly situated non-Jewish law graduates (Table 6, model 2; p < .05). Jewish lawyers also tend to work more in the public sector and less as solo practitioners relative to non-Jewish lawyers (Table 6, models 5 and 6; p < .001). However, statistically significant differences between Jewish and non-Jewish law graduates were not found in the regression models predicting full-time employment and working in the profession (possibly due to the relatively small number of non-Jewish respondents in our dataset).

Figure 2. Monthly Salary by Nationality, After the LL.B.

Ethnicity

The Ashkenazi Jews in our sample who work in the legal profession tend to earn more compared to all the other Jewish respondents (Figure 3). In multinomial regression models predicting the salaries of respondents—which controlled for demographics, experience, specialty, education, and employment conditions—being Ashkenazi resulted in a higher salary (Table 7, model 1; p < .01). Likewise, Ashkenazi Jews tend to be more satisfied than their non-Ashkenazi counterparts about having gone to law school but tend to be employed full-time less (Table 7, models 2 and 3; p < .001). Ashkenazi Jewish lawyers also are less likely to be solo practitioners compared to non-Ashkenazi Jewish lawyers (Table 7, model 6; p < .01). No statistically significant differences were found between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi Jews in their tendency to remain in the profession or to work in the private sector.

Figure 3. Monthly Salary by Ethnicity, After the LL.B.

Table 7. Regression Models Predicting Employment Outcomes, by Ethnicity (only Jewish Respondents)

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses, +p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Type of Institution

University law graduates who work in the legal profession tend to earn more than college law graduates (Figure 4). In multinomial regression models predicting salaries, university graduates tended to earn more (with demographics, experience, specialty, education, and employment controlled for) (Table 6, model 1; p < .001). Those who studied law at universities and work in the profession also tend to be less pleased with their decision to have attended law school compared to similarly situated college law graduates (Table 6, model 2; p < .001). University graduates (in contrast to college graduates) have less of a tendency to remain in the profession and tend to work more in the public sector and less as solo practitioners (Table 6, models 4, 5, 6; p < .001). No statistically significant differences between university and private college graduates were found in the regression models predicting full-time employment.

Figure 4. Monthly Salary by Type of Law School.

The Public and Private Sectors

To test whether the disparities we found amongst the different groups are less significant in the public sector compared to private practice, we ran additional regression models only on respondents who work in the public sector (Table 2A in the Supporting Information). As expected, we found no salary differences between Jewish and non-Jewish public-sector lawyers or between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi Jewish public-sector lawyers, while the gap between university law graduates and college law graduates narrows. Surprisingly, our analysis found that the gender wage gap is greater in the public sector than in the private sector. Figure 5 presents the salary levels according to gender in the private and public sectors.

Figure 5. Monthly Salary by Gender and Employment Sector, After the LL.B.

Discussion

Our study clearly reveals that the legal profession is stratified along gender, nationality, ethnicity, and class lines, exhibiting the same patterns of inequality and hierarchy that plague the Israeli labor market in general. These findings are consistent with the findings of empirical studies conducted on the legal profession in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. But while similar tendencies were found, some interesting divergences emerged as well between the situations in the Israeli legal field and in the legal profession elsewhere. In what follows, we analyze the stratification of the Israeli legal profession as compared to stratification of the Canadian and US legal domains—regarding gender, nationality and ethnicity, and social class. We conclude by examining the correlation between level of income in the profession and level of satisfaction with the decision to have attended law school.

Gender

One of the prominent changes that occurred in the Israeli legal profession since the 1970s is the increase in the number and proportions of women lawyers. Whereas in the 1970s women comprised only 13.4 percent of all registered lawyers, by the 1980s they accounted for 35 percent of the profession, and the proportion of females among registered lawyers continued to climb to 40 percent in the late 1990s and to 43 percent in 2010 (Reference Elias and ShitraiElias and Shitrai 1998). Currently, women account for almost half of all registered lawyers in Israel (Reference ZalmanovitshZalmanovitsh 2013), as reflected in our dataset. Since this trend began well before the growth in the total number of lawyers, which only occurred in the mid-1990s, we do not attribute it to the latter development. Nonetheless, the accentuated entry of women into the legal profession likely contributed to its acceleration (Reference Zer-GutmanZer-Gutman 2012).

The empirical literature investigating gender differences in legal practice reveals that such differences tend to emerge in the following frameworks: choice of practice setting, labor force participation (full-time/part-time and number of working hours), career advancement, and earnings.

Labor force participation: Our study found that women are more likely to be employed part-time; and even when they are employed full-time, they tend to work less hours than similarly situated men. These findings are consistent with the findings of United States and Canadian empirical studies. The AJD study found that women lawyers move from full-time to part-time jobs at a much higher rate than men do. In the 5-year period between AJD1 and AJD2, the total number of lawyers working full-time dropped from 94 percent to 87 percent, but women were seven times more likely than men to have transitioned to part-time. Overall, women were also found to work less than men: 49 weekly hours for women compared to almost 52 for men (AJD2, at 68).

Our study explored the reasons for the transition from full-time to part-time employment. The primary reason women lawyers gave for their decision to work part-time was childcare responsibilities (61 percent of all women who work part-time); this was followed by difficulty in finding a full-time job (13 percent). In contrast, only one percent of male lawyers who work part-time reported doing so to care for their children. This, again, is not surprising in light of the existing literature. AJD3 revealed that female lawyers’ decisions to work part-time or to completely exit the labor market are often influenced by family and childcare responsibilities: 15 percent of all women surveyed stated that they work part-time, while 9 percent reported that they do not work at all due to childcare responsibilities. In contrast, 96 percent of the male lawyers surveyed continue to work full-time despite having a larger number of children than the women surveyed (AJD3, at 68).

Practice settings: Our study revealed that women lawyers tend to be employed in the public sector (including NGOs) more so than their male counterparts (35 percent of the women and 24 percent of the men in our dataset). Women also tend to leave the legal profession at a greater rate than men (18.3 percent of women and 15 percent of the men in our dataset) and are less likely to start a solo practice (22 percent of the women and 35 percent of the men in our dataset are solo practitioners). These findings are similar to those in the United States and Canadian studies. In the United States, the AJD study showed that over time, both men and women tend to leave private practice (especially at an early stage in their careers), but women leave law firms (especially big ones) at a higher rate than men. For lawyers employed in large law firms with over 250 lawyers, 31 percent of the women and 20 percent of the men left their firms between AJD2 and AJD3; with regard to midsize law firms numbering between 101 and 250 lawyers, women left at a rate of 40.4 percent whereas men left at a rate of 9.5 percent. Transition patterns for smaller firms emerge as less gendered.

Gender differences in practice settings were also found in the Canadian LAB study, showing that 25 percent of the women lawyers surveyed work in the public sector, compared to 20 percent of the male lawyers. Half as many women as men were working in solo practice, but on the other hand, more women worked in the smallest private firms (2–20 lawyers).

Earning disparities: Perhaps our study's most troubling finding with regard to gender is the existence of earning disparities. An Israeli female lawyer tends to earn less than a male lawyer of the same ethnicity and nationality, even when they work at the same type of firm and practice the same area of law. This is true not only in the private sector but also—and more pronouncedly—in the public sector. Indeed, our data analysis revealed that the gender-based earning disparity in the public sector is greater than in the private sector. This picture diverges from the findings of studies of the legal profession conducted elsewhere and could be attributed to what sociologist Reference WilliamsChristine Williams (1992) coined the “glass escalator” phenomenon. According to Williams, in a female-dominated profession or career field, stereotypes about what a prototypical man is match with stereotypes about what a prototypical manager is. Thus, women tend to be promoted less than men in these female-dominated occupations and careers. Similarly, although women fill many of the positions in the Israeli public sector (where the working hours are better suited to their needs and responsibilities as mothers and less demanding than the private sector), the men employed in the public sector are probably more quickly promoted and, therefore, attain higher salaries. Because men—mostly Ashkenazi Jewish men—are those who occupy the top legal positions in the Israeli public sector, they have the power to reproduce their privileges in the legal field.

Interestingly, our study also showed that whereas women start their careers at a lower salary level than men, the gap narrows as they gain experience, so that women enjoy a higher salary premium for every additional year in the profession. Notably, however, women tend to leave the profession at a much greater rate than men do. If the women who leave the profession tend to be those who earn less than the women who stay, this may explain the narrowing of the wage gap over time.

Gender-based disparities in earnings in the private sector are not unique to Israel. A pay gap emerged also in the Canadian LAB study, where women's earning were 93 percent of men's ($75,000 compared to $80,000). The widest gender earning disparity was found in the business law sector, where the median salary for men was $100,000 while for women it was $79,000. The AJD study similarly found an earning disparity between men and women in private law firms, which persists and even exacerbates over time. At the early career stage, the gender gap was 5 percent; this increased to 12 percent after 7 years in the profession and to 20 percent after 12 years. The greatest pay gap was found in the largest law firms. The AJD study also revealed that men were more likely to be promoted to become equity partners than women, who were more likely to become nonequity partners. However, in contrast to the Israeli case, in the US public sector, the income gap stood at a meager 2–4 percent (AJD 3, at 67).

Lastly, our study confirms and supplements earlier studies on the motherhood wage penalty (Mandel and Kricheli-Katz forthcoming). Many studies have documented wage disparities between women and men in both the Israeli and American labor markets. Nonetheless, in the United States, it is primarily mothers who are discriminated against, compared to both men and women who are not mothers. On average, mothers in the United States suffer a wage penalty of approximately 5 percent per each additional child, as well as discrimination in hiring and promotion (Reference Budig and EnglandBudig and England 2001; Reference CorrellCorrell et al. 2007).

In Israel, only one study has documented discrimination against mothers in the labor force. This study suggests that mothers in Israel do not face a wage penalty compared to women who are not mothers (Mandel and Kricheli-Katz forthcoming). This does not mean that women in Israel are not discriminated against compared to men, but rather that amongst women workers, mothers are not particularly disadvantaged. Furthermore, we found in the present study that while women are not penalized for becoming mothers, they do receive a wage penalty for cohabitating, which usually precedes becoming a mother.

What can account for this divergence between the United States and Israel in the treatment of mothers in the work force? In the United States, the percentage of women who are not mothers has been increasing dramatically over the past few decades. The more successful a woman is in her career, the less likely she is to become a mother. In Israel, the number of women who choose not to become mothers still appear to be very low, as Israeli society continues to encourage motherhood. Indeed, the majority of Israelis view motherhood as the most rewarding and fulfilling activity for women and assume it to be the default choice. Some Israelis even regard motherhood for Jewish women as a civil duty toward the Jewish state, under the perception that Jews in Israel are in a demographic contest with Palestinians (both those who are Israeli citizens and those living in the occupied territories). Most women in Israel report experiencing motherhood not as a voluntary choice but as an inevitable occurrence, and women who choose to forego motherhood are generally viewed as selfish, cold, and even troubled (Reference DonathDonath 2017). As a result, when an Israeli woman begins to cohabitate with her partner, employers tend to regard her as a potential mother.

Nationality and Ethnicity

As discussed above, Israeli society is stratified along national and ethnic lines. The Arab citizens of Israel are disadvantaged in relation to Israeli Jews, while within the Jewish population, Mizrahi Jews are traditionally less privileged than Ashkenazi Jews. The question we investigated was whether these divisions and hierarchies manifest also in the legal profession. The results were unequivocal: we found clear disparities between the three social groups—Arabs, Ashkenazi Jews, and Mizrahi Jews—in terms of practice settings and earnings, but no statistically significant differences with regard to labor force participation.

Nationality-based practice settings and earnings: Our study found that Arab lawyers tend to work less in big law firms and more in solo practice than their Jewish counterparts. This is due, in all likelihood, to the persistent discrimination against Arabs in the Israeli labor market in general, and the Israeli-Jewish market for legal services in particular, as well as the absence of large and medium-sized Arab law firms, which compels many Arab law graduates to opt for solo practice. The ADJ study also found racial and ethnic-based discrimination in the US labor market. Although the latter found varying patterns of job mobility in the legal profession for different racial and ethnic minorities (Black, Hispanic, and Asian lawyers), overall, these groups tended to be underrepresented in private law firms. Private law firms employed the lowest proportion of Black lawyers (one-third of all Black lawyers at the AJD3 stage), while the number of Black lawyers employed at both small and large private law firms declined over time. The number of Hispanic lawyers at medium and large firms (but not at small firms) also declined over time. Asian lawyers exhibited a slightly different employment pattern; they were highly represented in private firms at the first two stages of the study (AJD1 and AJD2), but their proportion declined significantly by AJD3. Notably, these findings should be understood in light of indications that working at large versus small law firms affects lawyers’ prestige, income, associational networks, and autonomy (Reference Heinz and LaumannHeinz and Laumann 1982).

The Israeli legal market exhibits certain unique characteristics concerning minority employment in the public sector. Both the ADJ and LAB studies revealed that lawyers from minority groups tend to be overrepresented in the American and Canadian public sectors. It clearly emerged from the ADJ studies that Black lawyers are more likely than any other minority groups to work in the public sector; and indeed, at the AJD3 stage, 42 percent of all lawyers employed in the different branches of government were Black. Hispanic lawyers were also found to be disproportionately represented in the government and public sector. The LAB study similarly indicated that minority lawyers were more likely to work in the public sector (29.9 percent as opposed to 21.7 percent for White lawyers). White lawyers were found to be strongly represented at private law firms (70.1 percent versus 58 percent for nonWhites), while Black lawyers were overrepresented in the public sector.

Our study, in contrast, revealed a different pattern of minority employment: a lower proportion of Arab lawyers are employed in the public sector than their Jewish counterparts. These results are not surprising for anyone acquainted with the Israeli labor market. In general, the employment of Arabs in the public sector is quite low, standing at 7 percent in 2010 and 9 percent in 2015 (Knesset, Research and Information Center 2015), due to discrimination as well as the poor educational infrastructure in Arab localities. The Israel Supreme Court, the Knesset, and the Israeli government have been allegedly trying to amend this situation and advance Arab employment in the public sector, through judicial decisions and legislation mandating “adequate representation” of Arabs in the public sector. But as our study clearly demonstrates, this goal is yet to be attained.

Comparing the earnings of Arab and Jewish lawyers, our study found that Jewish lawyers who work in the private sector earn more than Arab lawyers in that sector, when holding constant other relevant variables that can affect salary (other than geographic location),Footnote 8 such as demographics, education, firm size, and field of practice. For those Arab lawyers who do manage to find a job in the public sector, the earning disparity with Jewish lawyers disappears. Minority groups’ earnings in other countries follow a similar pattern. Although the earnings of racial and ethnic minorities vary across practice settings and geographic areas, minority lawyers in private practice clearly earn less than their White counterparts do. Over time, all groups experience an increase in earnings, with Asians and Blacks showing the smallest salary growth (14.81 percent and 15.5 percent, respectively) and Hispanics the largest (32 percent) (AJD3, at 76).

Ethnicity-based practice settings and earnings: Focusing on Jewish lawyers, our study found that non-Ashkenazi Jews are more likely to be in solo practice and less likely to work in the public sector than similarly situated Ashkenazi Jews. These trends, which resemble the pattern that emerged for Arab lawyers relative to Jewish ones, can be explained similarly: non-Ashkenazi lawyers are more likely not to be employed by big law firms or in the public sector and therefore more likely to start a solo practice. Note that unlike the transformations that occurred in the United States and Canada, where the public sector opened its gates to lawyers from minority groups, in Israel, large segments of the population are still excluded from the lucrative public-sector positions, including Arabs and Mizrahi Jews. Thus, both Arab and non-Ashkenazi lawyers are yet to attain access to the most prestigious positions in the Israeli legal profession that is proportionate to their representation in the general lawyer population. Interestingly, non-Ashkenazi Jews are more likely to work full-time than Ashkenazi Jews.

Lastly, our study also found an earning disparity between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi lawyers in the private sector—a gap that does not exist in the public sector. While Jewish lawyers in general earn more than Arab lawyers do, amongst Jewish lawyers, Ashkenazis earn more than otherwise similar non-Ashkenazis. A presumed limitation of our study is that we lack information about the respondents’ geographic location in practicing law. Since lawyers who work in the center of Israel earn on average more than those lawyers practicing in the periphery, we could hypothesize that if more non-Ashkenazi lawyers than Ashkenazi lawyers practice law in the periphery (which is conceivable), the earning disparity could be attributed to geographical location of the firm rather than the lawyer's ethnicity. However, this hypothesis is countered by the finding that non-Ashkenazi lawyers who work in big law firms (firms with over seventy lawyers) earn less than similarly situated Ashkenazi lawyers. And given that there are no big law firms (only small and medium-sized firms) outside Israel's center, clearly, the difference in earnings must be attributed to ethnicity rather than geography.

Social Class

Determining our respondents’ social class was a difficult task, especially in the absence of comprehensive data on their socioeconomic background. While a partial overlap exists between social class and nationality/ethnicity, the latter categories do not serve as a good enough proxy for the former in the case of the respondents, especially given the considerable upward mobility of Arabs and Mizrahi Jews during the last couple of decades (Reference DahanDahan 2013). The best proxy for social class within our dataset is the type of law school respondents attended, which is often used in empirical studies of the legal profession (Reference Dinovitzer and GarthDinovitzer and Garth 2007). As discussed, prior to the reform in legal education of the 1990s, only the socioeconomic elite had access to the legal profession. Following the reform and the opening-up of 10 new accredited law colleges, population groups hitherto excluded from the profession were increasingly allowed in, many of whom belonged to the lower classes seeking upward mobility through professionalization (Reference KatvanKatvan 2012). Moreover, recent studies confirm that one of the best predictors of the ability to study at an Israeli university (rather than a college) is the student's socioeconomic background (Council for Higher Education 2016). Thus, we might assume that the numerous students at the new law colleges during the period under investigation were mainly from the lower social strata.

Our measure of the law school hierarchy in Israel is based on the rankings in Forbes Magazine in 2012, which placed Israel's four university law schools in the top five places and all of the law colleges but one—the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC)—below them.Footnote 9 Based on this ranking, we divided all law schools into two tiers: in the first tier, we placed the four universities; and in the second tier, the law colleges (excluding the IDC). Our analysis of the intersection between respondents’ nationality and ethnicity and the type of institution attended (university or law college) yielded, as we expected, a partial correlation between the two: only 38 percent of the Ashkenazi respondents in our dataset graduated from law colleges, as opposed to 59 percent of the Arab respondents and 60 percent of the non-Ashkenazi respondents. A higher proportion of the women in our dataset graduated from university law schools (53 percent) than the male respondents (48 percent).

Our study also found that university law graduates have a greater tendency than college graduates to leave the legal profession for other occupations, likely because of the greater job opportunities open to the elite as compared to lawyers from lower socioeconomic strata. University graduates also tend to work more in the public sector and are less likely to practice law solo, compared to similarly situated law college graduates. These findings can be explained in a similar manner to our suggestion above with regard to nationality and ethnicity: law college graduates are less likely to be offered a job in either private law firms or the public sector and are thus forced to enter solo practice. Last but certainly not least, university graduates earn significantly more than their college graduate counterparts. While this earning disparity exists in all sectors, the wage gap is wider in the private sector and narrower in the public sector.

Level of Satisfaction

Our study found a fairly high overall level of satisfaction amongst respondents regarding their decision to become a lawyer: 76 percent. Moreover, we found a significant positive correlation between level of income and degree of satisfaction with having gone to law school. Lawyers who work in the public sector are more satisfied with their decision than similarly situated lawyers in the private sector, and those who work for NGOs are the most satisfied with their decision, although they earn less. Using lawyers who practice tort law as our reference point, lawyers who practice commercial, corporate, or real estate law were found to be less satisfied with their decision to become a lawyer, while lawyers who practice employment, family, or criminal law were found to be more satisfied. The overall rate of satisfaction of 76 percent is slightly lower than the satisfaction rate found in the LAB study, where 79.3 percent of the respondents reported being extremely or moderately satisfied with their decision to become a lawyer.

The picture is more complex and interesting when we consider the level of satisfaction among the different groups comprising the profession. Both Arab and non-Ashkenazi lawyers report lower levels of satisfaction with their decision to become lawyers than similarly situated Ashkenazi lawyers; Arabs are the least satisfied. A likely explanation for this finding is that lawyers from these minority groups feel disadvantaged relative to their Ashkenazi counterparts in both the opportunities available to them and their earnings. Our findings in this regard are only partially consistent with those in the United States and Canadian studies. While in the AJD, Black and Hispanic respondents reported the highest levels of career satisfaction, more than their White counterparts, the LAB found that lawyers from minority groups expressed lower levels of satisfaction than White lawyers regarding the decision to become a lawyer.

Regarding levels of satisfaction by gender, our study reveals that although on average, men in our dataset tend to be more satisfied than women with their decision to become lawyers, a regression analysis revealed that in fact women tended to be more satisfied than similarly situated men. Notably, the comparable AJD study found that women lawyers expressed a higher level of satisfaction when they worked solo or in small firms as well as when they worked with legal services, the public defender, public interest, nonprofit organization and educational settings. Men were more satisfied in medium and large firms (but not in mega-firms) and in government positions in general (ADJ3 at 69). The LAB study found that overall, women reported slightly lower satisfaction rates than men (77.2 percent vs. 81.6 percent) and pointed to the substance of their work as well as to their work setting as significant in determining level of satisfaction. Women also reported lower level of satisfaction than men with regard to their career tracks and the social value of their work (LAB at 48). In our dataset, further analysis reveals that working solo positively affects women's satisfaction but not men's, whereas working in the public sector affects both women's and men's satisfaction to a similar extent. Finally, the number of lawyers at the law firm affects neither women's nor men's career satisfaction.

One of the most interesting and counterintuitive finding that emerged from our study is that university graduates who work in the profession are less satisfied with their decision to have attended law school than similarly situated college graduates: among university graduates, the median level of reported satisfaction was 3.73, compared to 3.82 among college graduates. At first glance, this is surprising, since law college graduates are at a disadvantage relative to university graduates in almost every respect. They are less likely to find a lucrative job in either the private or public sector and, therefore, often have no option but to become solo practitioners, and on average, they earn much less than university graduates. Despite this reality, college law graduates are clearly more satisfied with their decision to have attended law school than their university graduate counterparts are. Following Reference Dinovitzer and GarthDinovitzer and Garth (2007), we suggest that this can be explained by the correlation between type of institution attended and social class.

Reference Dinovitzer and GarthDinovitzer and Garth (2007) have shown, based on data from the AJD1 study, that law graduates from lower-tier law schools experience greater satisfaction with their decision to become lawyers. They found a strong inverse correlation between the ranking of the law school attended by respondents and their level of satisfaction, with graduates of the lowest-tier law schools reporting the highest levels of satisfaction and vice versa. The authors accounted for this apparent paradox using a Bourdieusian theoretical framework. According to Bourdieu, social stratification is not externally produced; rather, as part of the function of habitus (namely, the set of practices and dispositions one acquires through the repetition of living life), individuals internalize what they can and cannot reasonably expect in life (Reference Calhoun and RitzerCalhoun 2003). Thus, it is people's choices and expectations that reproduce patterns of stratification, and Bourdieu reminds us to recall that the “dispositions that incline them [people] toward this complicity are themselves the effect, embodied, of domination” (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1998, at 4). This is particularly true with regard to educational institutions. According to Reference BourdieuBourdieu (1977, Reference Bourdieu1998), “schools are a key site through which students acquire their professional expectations—schools thereby play a critical role in the reproduction of social stratification, with students not merely acquiring the skills they require for professional life” (Reference Dinovitzer and GarthDinovitzer and Garth 2007, at 10).

This Bourdieusian theoretical framework can also help explain our findings. University graduates’ relative lack of satisfaction may be due to their privileged, elitist position and expectations, which creates in them the expectation of being able to do almost anything they want and to reap any professional reward they pursue. Therefore, they are in a constant state of discontent over what they have not (yet) achieved. In contrast, despite their worse objective circumstances, college law graduates are aware of the advantage and career opportunities that their law degree has given them. Had they not decided to attend law school, the alternative career path would have often been far worse. Hence, they consider themselves lucky, and it is perfectly reasonable that they would not seek positions and professional rewards that are out of their reach.

Conclusion

The Israeli legal profession, like the legal profession in other countries, replicates the gender, ethnic, national, and class segregation that occurs in the Israeli labor force and in the Israeli society in general. Although since the 1990s, a greater number of new lawyers have been admitted to the bar, women, Arabs, non-Ashkenazi Jews, and people who study in private colleges still fare much worse in the legal profession. They do become lawyers, but they are employed in less prestigious jobs, earn less money, and are more likely to become solo practitioners; thus, their degree of satisfaction with their decision to have attended law school is significantly different than that of similarly situated Ashkenazi Jewish men. Thus, the Israeli case study provides evidence for the over-determinacy of systems of inequality that manage to maintain and reproduce themselves even at times of social and economic changes—as in the case of a sharp increase in the number of lawyers.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's Web site:

Table 1A. Ordered Logistic Regression Models Predicting Salary, After the LLB.

Table 2A. Ordered Logistic Regression Models Predicting Salary, After the LLB.