INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV)Footnote 1 victimization among women is well documented in the United States (Reference Breiding, Smith, Basile, Walters, Chen and MerrickBreiding et al., 2014). According to the 2010–2012 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), 4 out of 10 women in the U.S. experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner at some point in their lifetimes, with the majority having suffered physical violence (Reference Black, Basile, Breiding, Smith, Walters, Merrick, Chen and StevensBlack et al., 2011; Reference Smith, Basile, Gilbert, Merrick, Patel, Walling and JainSmith et al., 2017). Based on 2010–2012 NISVS estimates, 1 in 15 women have experienced IPV in the last 12 months (Reference Smith, Basile, Gilbert, Merrick, Patel, Walling and JainSmith et al., 2017). Most women who experienced IPV reported harmful psychological, physical, health, housing, and/or financial impacts (Reference Smith, Basile, Gilbert, Merrick, Patel, Walling and JainSmith et al., 2017).

Economic impact of intimate partner violence

Experiencing IPV impacts women's economic well-being. Among lower-income women, experiencing IPV is associated with employment and income insecurity in the short-term (Reference Rothman, Hathaway, Stidsen and de VriesRothman et al., 2007; Reference Staggs and RigerStaggs & Riger, 2005); and, the impact of IPV on women's economic well-being often continues after women exit abusive relationships (Reference Lindhorst, Oxford and GillmoreLindhorst et al., 2007). Lower-income women reporting a need for IPV services also report lower wage-based income than lower-income women not reporting a need for IPV services (Reference Meisel, Chandler and RienziMeisel et al., 2003).

Although experiencing lower income or poverty increases IPV risk (Reference Cunradi, Caetano and SchaferCunradi et al., 2002), increasing income, especially through employment wages, has been linked to a reduced risk of experiencing IPV (Reference Gibson-Davis, Magnuson, Gennetian and DuncanGibson-Davis et al., 2005). Economic strain (e.g., living in poverty) and victimization have a reciprocal relationship. This strain is linked to an increased risk of experiencing IPV, and experiencing IPV increases financial hardship (Reference Fahmy, Williamson and PantazisFahmy et al., 2016; Reference Renzetti and LarkinRenzetti & Larkin, 2009).

Prevalence of civil legal issues and access to legal services

Civil legal services address a myriad of legal issues, including consumer (e.g., bankruptcy, utility shut-offs), education (e.g., special education, discrimination), employment (e.g., employment rights/discrimination, wage claims), tax (e.g., tax fraud), family (e.g., divorce, child support, and civil protective orders), juvenile (e.g., child maltreatment, guardianship), health (e.g., benefits coverage, claims denials), housing (e.g., landlord/tenant disputes, housing discrimination), public benefits (e.g., unemployment, veterans benefits), individual rights (e.g., civil/disability rights), and other matters, such as powers of attorney, and torts (Legal Services Corporation [LSC], 2017).

According to a recent survey, most low-income households in the U.S. reported at least one civil legal issue in the last year (LSC, 2017). Available evidence indicates that the proportion of low-income households reporting civil legal needs has increased over the past few decades, from 50% in 1992 to 71% in 2017 (American Bar Association, 1994; Civil Legal Needs Study Update Committee, 2015; Reference FisherFisher, 2019; LSC, 2017). Furthermore, civil legal issues and experiencing IPV are almost universally and inextricably linked, with 97% of lower-income households with IPV experiences reporting at least one civil legal issue (LSC, 2017). Two out of three lower-income households with IPV experiences also reported higher numbers of civil legal issues (six or more individual needs) compared to one out of four lower-income households not experiencing IPV (LSC, 2017).

Lower-income women who experience IPV face a persistent lack of access to civil legal representation, despite the number and severity of civil legal issues they face. In a 2016 assessment of utilizers of domestic abuse shelters and services, participants (utilizers) reported the gap between needs and services was second largest for legal representation, only behind housing assistance (National Network to End Domestic Violence [NNEDV], 2017). This gap between needs and services is especially striking, given that many people do not recognize justice needs as legal issues and seek resolution outside the formal justice system (Reference SandefurSandefur, 2014).

Despite the high prevalence of civil legal needs, the majority (86%) of individuals in the United States with lower incomes receive no or inadequate legal services for their civil legal problems (LSC, 2017; Reference SandefurSandefur, 2014). Lack of access to legal services results in most civil legal needs going unaddressed or addressed without the support of legal counsel (LSC, 2009, 2017; Reference SandefurSandefur, 2014) and contributes to a high percentage of pro se (i.e., without legal representation or “self-represented”) litigants in family courts (Reference Knowlton, Cornett, Gerety and DrobinskeKnowlton et al., 2016; Reference MansfieldMansfield, 2016). Looking specifically at IPV, approximately 90% of low-income petitioners or respondents in family law cases involving IPV were pro se (District of Columbia Access to Justice Commission, 2008), and 80% of women petitioning for civil protection orders (CPOs) were filing pro se (Reference Knowlton, Cornett, Gerety and DrobinskeKnowlton et al., 2016; LSC, 2017; Reference MurphyMurphy, 2003). Not surprisingly, women experiencing IPV are less successful in obtaining CPOs when they do not have the benefit of legal counsel (Reference AdamsAdams, 2005; Reference DurfeeDurfee, 2009), especially if the perpetrator has an attorney (Reference MurphyMurphy, 2003). Victims who file pro se petitions often experience problems navigating legal procedures, policies, and processes (Reference AdamsAdams, 2005).

Civil legal representation and intimate partner violence

Unlike criminal law cases for which most defendants have a right to counsel regardless of their ability to pay, individuals in most civil law cases do not have a similar right to counsel. Individuals secure civil legal counsel through one of five options: fee-for-service, hourly rate payments, contingency fees, pro bono volunteerism, or subsidized legal services. Civil legal aid is most commonly provided pro bono or subsidized by state and federally funded legal providers to lower-income people (typically, the service eligibility upper income limit is 125–200% of the Federal Poverty Level). The foundation of the federal civil legal aid efforts has roots in the mid-1960s War on Poverty (LSC, 2019), and previous evaluations have supported anti-poverty effects of participation in civil legal aid (Reference HousemanHouseman, 2015; Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2014); however, longitudinal research supporting this anti-poverty effect has been limited (Reference HousemanHouseman, 2015).

As previously noted, women who experience IPV and seek help often want legal advocacy services (NNEDV, 2016, 2017). Previous researchers have found positive changes in psychological well-being among women who experienced IPV and received legal aid representation (Reference Renner and HartleyRenner & Hartley, 2018). Researchers have also supported a potential material empowerment (i.e., income) impact of legal aid representation among women who experienced IPV (Reference Hartley and RennerHartley & Renner, 2016, Reference Hartley and Renner2018). In particular, women reported increases in personal income over time, despite an average decrease in public benefits receipt (Reference Hartley and RennerHartley & Renner, 2018). With women experiencing IPV having substantial civil legal needs and some evidence that receiving civil legal aid improves these women's economic situations, the association between legal services and income among women experiencing IPV is worth further study.

Exploring this link is especially relevant given the research on having legal representation and better family law case outcomes. Courts deny relatively few people with legal representation who are pursuing CPOs (17%); in contrast, most people without representation are denied a CPO (68%) (Reference MurphyMurphy, 2003). Similarly, IPV victims who have legal representation achieve a more likely to finalize a divorce and are more likely to receive child support and child custody than those without representation (Reference KernicKernic, 2015). Generally, lower-income women who receive civil legal aid fare better with divorce outcomes than women who receive self-help materials, advice, or external referrals (Reference Degnan, Ferriss, Greiner and SommersDegnan et al., 2018). For example, in exploring the impact of representation in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, approximately 9 out of 10 low-income women with an attorney achieved a divorce within 3 years, where only 1 in 20 women without representation achieved a divorce within the same time frame (Reference Degnan, Ferriss, Greiner and SommersDegnan et al., 2018).

Civil legal aid, thrivership, and economic well-being

Several theories provide insight into links between women's access to legal representation and economic well-being. Survivor theory holds that people experiencing IPV engage in active help-seeking behaviors, and the gap between remaining in an abusive relationship or leaving the relationship is the amount of positive support and services available to the victim (Reference Gondolf and FisherGondolf & Fisher, 1988). Thrivership theory builds upon survivor theory and posits three elements essential to women thriving after experiencing relationships characterized by IPV: (1) provision of physical and emotional safety, (2) story sharing, and (3) social response (Reference Heywood, Sammut and Bradbury-JonesHeywood et al., 2019, p. 12). Engaging with an attorney to navigate the justice system provides for physical safety through CPOs and emotional safety through women's acquisition of knowledge of their legal rights to help protect them from current and future abuse. With their attorney's support, participating in a procedurally fair justice system allows women to tell their stories. Sharing their stories, in this case publicly in court, contributes to women's thriving by empowering them to take ownership of their pasts and move forward in their healing (Reference Heywood, Sammut and Bradbury-JonesHeywood et al., 2019). Social responses, such as positive interactions with professionals who socially validate women's experiences, further enable and reinforce women's thriving (Reference Heywood, Sammut and Bradbury-JonesHeywood et al., 2019).

Civil legal aid received by women experiencing IPV can provide concrete income assistance by increasing women's income and decreasing their economic liabilities (Reference Hartley, Renner and MackelHartley et al., 2013). For example, through civil legal proceedings, women can receive adequate child and spousal support and equitable distributions of marital assets and property. Civil attorneys can also help reduce women's economic liabilities when exiting a marriage by reducing fraudulent debt accrued during the marriage or medical bills resulting from the abuse to the perpetrator of IPV.

Beyond concrete income assistance, civil legal representation more broadly supports women's transitions from IPV relationships and improved personal thriving (Reference Heywood, Sammut and Bradbury-JonesHeywood et al., 2019) by contributing to material empowerment (Reference PaynePayne, 2017), which improves as material resources such as income, insurance, housing (quality or security), food, employment, legal status, and education increase. Furthermore, based on social control and bargaining theories, women experiencing IPV who access supportive services, such as civil legal aid, experience less violence than those who did not receive services (Reference Farmer and TiefenthalerFarmer & Tiefenthaler, 1996, Reference Farmer and Tiefenthaler1997, Reference Farmer and Tiefenthaler2003). Supportive services create a foundation for women's self-sufficiency, especially economic self-sufficiency (Reference Farmer and TiefenthalerFarmer & Tiefenthaler, 2003, Reference Farmer and Tiefenthaler2004). In turn, increasing women's income-related self-sufficiency decreases IPV by mitigating the potential for financial, emotional, or physical abuse (Reference Farmer and TiefenthalerFarmer & Tiefenthaler, 1997; Reference Gibson-Davis, Magnuson, Gennetian and DuncanGibson-Davis et al., 2005; Reference ReskoResko, 2008; Reference TiefenthalerTiefenthaler, 2012). The social–ecological model holds that IPV is simultaneously an issue of person, relationship, family, community, and society (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). For an individual to thrive, superordinate levels of influence must facilitate thriving. Social or legal services can act as violence disrupters. In this case, an attorney (community) offers proxy expert agency to an individual experiencing IPV to interrupt relationship patterns and enact the protections allowed under the rule of law (society).

The present study

Our aims are (1) to evaluate changes in private and public benefits income over time among women who experienced IPV and received civil legal aid services, and (2) to estimate the social return on investment (SROI) of providing civil legal aid services to women who experience IPV. Previous research investigating the potential longitudinal impacts of civil legal representation has not explored simultaneous changes in various types of private and public benefits income. Prior research on wage-based income among women seeking CPOs supported differing trajectories of income between women who were and were not participating in social welfare assistance (i.e., Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC] or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families [TANF]) (Reference Hughes and BrushHughes & Brush, 2015). More specifically, Reference Hughes and BrushHughes and Brush (2015) examined how women's earnings rose or fell at the time of petitioning and in the year after filing. Overall, they found that the period around filing for the CPO was characterized by significant earnings instability and financial costs, and many women did not recoup these losses in the 1-year post-filing assistance. However, women who participated in welfare (i.e., AFDC or TANF) and filed for a CPO had wages that increased at a higher level across time relative to women filing for a CPO who had not received welfare. Thus, they concluded the wage impact of filing a CPO is potentially moderated by social welfare assistance program participation. They also found that the average wage trajectory for welfare recipients who filed a CPO was similar 1 year before and 1 year after filing.

Researchers have not sufficiently examined the effects of material empowerment, changes in poverty status, and the social return on investment (SROI) of legal assistance among lower-income women who have experienced IPV. For example, Reference Degnan, Ferriss, Greiner and SommersDegnan et al. (2018) examined the impact of legal representation on divorce outcomes but not income over time. Changes in poverty status and the social return on investment (SROI) of legal aid have not been evaluated across time. In this study, we use the SROI of civil legal aid to estimate the potential material empowerment of income among women who experience IPV and receive civil legal assistance.

First, using existing prospective data, we assessed changes in amounts of income across multiple types of income (private, public, and total personal income) and poverty status among women who experienced IPV and sought assistance from legal aid. We tracked these outcomes across time, with approximately 12 months of study participation per individual. We assessed women's income before receipt of civil legal services (Wave 1) and at 6- and 12-months (Waves 2 and 3) after receiving services.

Four research questions guided the examination of the first aim: (1) Did overall personal income (combining private and public benefits income) and private income significantly increase across time, and did public benefits income significantly decrease across time (i.e., before and after receipt of civil legal aid services)?; (2) What types of private income increased across time?; (3) What types of public benefits income decreased across time?; and, (4) Assuming there was an increase in overall personal income across time, was there a change in the proportion of women below the federal poverty level at the study's beginning, before civil legal services, compared to their poverty status at 1-year follow-up?

Assuming private income increases across time and given the means-tested requirements of several public benefits (e.g., TANF, food stamps [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP], WIC [Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children], and Social Security benefits (Supplemental Security Income [SSI])), we hypothesized that as private income rose, there would be a subsequent drop in income from public benefits as individuals lose their eligibility for such programs. We expected to find fewer women living in poverty over time as prior researchers have supported a potential anti-poverty effect of civil legal aid participation (Reference Houseman and MinoffHouseman & Minoff, 2014).

Second, we estimated the SROI of civil legal aid service representation as a method to resolve civil legal needs among women who experienced IPV. One research question guides the examination of this aim: (1) after identifying the income outcomes, what was the SROI impact of civil legal aid services among women experiencing IPV? Prior evaluations support a potentially positive social return on investment of civil legal aid service provision (American Bar Association, 2019).

METHOD

Data source

Data come from a panel study of women who experienced IPV and received civil legal services from Iowa Legal Aid (ILA). Women in the larger study completed at least one, and up to five interviews, at 6-month intervals, over 2 years. Eligible participants were self-identified victims of IPV who contacted ILA for a civil legal matter. ILA is a nonprofit civil legal aid organization providing services to low-income Iowans from 10 regional offices. In 2015, ILA closed 16,300 cases serving nearly 38,000 Iowans. During 2016, an estimated 811,500 Iowans fell below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017), and the average household size in Iowa between the years 2015 and 2019 was 2.62 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Therefore, there were approximately 257,216 low-income households in Iowa with at least one civil legal need annually. ILA has a long-standing commitment to addressing IPV-related issues. One-third of ILA cases involve family law issues (e.g., divorce, custody, child support). The majority of these include IPV.

Recruitment and data collection

Recruited participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) identified as female and were 18 years of age or older; (2) currently experiencing IPV or had a recent history of IPV based on screening questions ILA uses during their client intake process; (3) had minor children in the home; and, (4) had a civil legal service request for assistance with a CPO or a family law problem (divorce, child custody, child support). We included both family law cases and CPOs because these are the two largest categories of legal services provided to women by legal aid offices (Institute for Law and Justice, 2005).

We recruited participants into the study within a few days after ILA took their case. Women who agreed to participate were assigned to an interviewer in their geographic area of the state. Interviewers in seven locations around the state conducted a baseline interview (Wave 1) and up to four follow-up interviews at 6-month intervals (Waves 2–5). Baseline interviews typically took place less than 2 weeks after ILA accepted a woman's case.

Interviewers conducted all interviews in-person unless a participant moved out of the area and was willing to complete a follow-up interview by phone. Interviewers asked study participants a set of project-specific and standardized scales, along with several open-ended questions. On average, Wave 1 interviews lasted 90 minutes, and subsequent interviews were approximately 1 h in length.

Data collection occurred between June 2012 and November 2015. Because of attrition at Waves 4 and 5, we limited the analyses to data from Waves 1, 2, and 3 (baseline, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up) to ensure the finding's statistical validity. A total of 150 women completed a Wave 1 interview. Approximately 75% (n = 112; 74.7%) of the Wave 1 sample was retained for Wave 2, and 75.9% (n = 85) of the Wave 2 sample was retained at Wave 3.

Our potential sample was the 85 women who completed interviews at Waves 1, 2, and 3. We removed three women from the final sample because their reported income would have deemed them ineligible for legal aid services based on income criteria. The final sample consisted of 82 women (see Table 1). Additionally, 27 women who were retained only through Wave 2 were included in supplemental analyses. The mean age of the respondents at Wave 1 was 31.71 years (SD = 7.32). All the women had children (M = 2.54; SD = 1.65; range = 1–9). Most women identified as non-Hispanic White (n = 70; 85.37%), which reflects Iowa's population. However, the percentages of non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women in the sample were slightly higher the state population. Most of the women had at least some college education (n = 62; 75.61%). Approximately half were working either part-time or full-time at Wave 1 (n = 42; 51.22%).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and abuse characteristics for study sample (N = 82)

The women all had male partners who perpetrated violence against them and all reported high levels of physical and nonphysical IPV at Wave 1 based on the Index of Spouse Abuse (Reference Hudson and McIntoshHudson & McIntosh, 1981), the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (Reference TolmanTolman, 1999), and the Women's Experience of Battering scale (Reference Smith, Smith and EarpSmith et al., 1999). The average length of the women's relationship with the IPV perpetrator was 5.38 years (SD = 5.48). Over half the women were married to the perpetrator at some point (n = 47; 57.32%), and nearly all women (n = 78; 95.12%) lived with this person for a period of time. We used women's zip code to discern their county of residence at Wave 1. We identified counties as metro, urban, or rural based on 2013 Rural Urban Continuum codes. Over half the women lived in metro areas of the state (n = 45; 54.88%), while 23 (28.05%) and 14 (17.07%) resided in urban and rural areas, respectively. Fifty-three women (64.63%) received assistance for a CPO, while 29 (35.37%) sought services for a family law problem. The average hours spent on a CPO case by the legal aid organization was 12.15 (SD = 6.63; range = 3.50–35.30), and the average hours spent on a family law case was 35.06 (SD = 28.14; range = 10.50–137.65).

We tested associations between demographic variables and study retention at Waves 2 and 3 separately using chi-square tests and independent samples t-tests. Demographic variables included geographic location (urban vs. rural), race (non-Hispanic White vs. other), education (college degree vs. no college degree), employment (currently working vs. not working), type of legal services (family law vs. CPO), current relationship status with a partner (not limited to the original partner), amount of legal services received (based on the amount of hours and the type of legal matter addressed), age, number of children, and length of relationship with their partner. Geographic location and education were related to study retention at Wave 2 (p < 0.05), with women living in rural settings and women with college degrees more likely to remain in the study. Women with higher scores on several IPV measures at Wave 1 were also more likely to be retained at Wave 2. Location was the only variable related to retention at Wave 3, with women living in rural settings more likely to remain in the study.

Measures

Income

At each wave, women reported their exact monthly income from several sources. Monthly private income was a sum of wages, child support, rent from tenants, money from a new partner, and money from family and friends. Monthly public benefits income was a sum of food stamps, Social Security, FIP (Family Investment Program, Iowa's TANF program), WIC, unemployment benefits, and worker's compensation/disability. We calculated total monthly income as a dollar summation of private income and public benefits. The only category of income excluded from the calculation of total income, private income, and public benefits was “other income” because it was infrequently reported, and it was unclear if the “other” income was private or public. In Waves 1, 2, and 3, 8.5%, 7.3%, and 6.1% of women, respectively, reported income from other sources.

Poverty

We estimated poverty status during Wave 1 and Wave 3 by linking estimated total annual personal income and household size to appropriate wave-timed 2012–2015 Federal Poverty Guideline charts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012–15). We estimated women's annual total personal income by multiplying their monthly summed income amount during Waves 1 or 3 by 12. Household size was assessed at each wave based on participants' self-report.

Cost of legal aid services

We calculated the cost of providing legal aid services based on the number of hours spent on cases for each client multiplied by the average hourly cost to provide civil legal aid services. The hourly cost of civil legal aid in Iowa was $70 per hour on average as an upper limit (ILA, 2018), compared to the median comparable private-sector attorney hourly costs of $140 to $199 per hour (ILA, 2013, 2018; Reference ResearchResearch, 2015; Reference Rottler and GrossRottler & Gross, 2016).

Analysis plan

First, we used parametric and nonparametric repeated measures statistical procedures (ANOVA and Friedman) to separately examine the within-subjects omnibus time effects (across three waves) of monthly private income, monthly public benefits income, and total monthly personal income. Along with these inferential statistics, we calculated descriptive statistics (Table 2). Nonparametric analyses (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) accounted for the potential impact of skewed data. We tested changes across Waves 1 and 2 between those participants who remained in the study through Wave 3 and those who were retained only to Wave 2 with supplemental repeated measures ANOVA analyses.

Table 2. Means, medians, and standard deviations for economic self-sufficiency measures by wave (N = 82)

Second, assuming the overall time effect of income was statistically significant (indicating the mean and median differed across time), we analyzed the subscales that made up the summated income scales for within-subjects time effects. Third, assuming concordant significant findings of nonparametric and parametric repeated measures tests of income across time, we conducted polynomial analyses (linear and quadratic) and pairwise contrasts in repeated measures ANOVA. Additionally, we utilized nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank methods to test the pair-wise contrasts within the broader omnibus effects of time and also calculated eta squared effect sizes (η 2) for time, polynomials, and contrasts. We analyzed the potential anti-poverty effect of legal aid by comparing poverty at Wave 1 and Wave 3 using the nonparametric McNemar's test (significance) as well as the odds ratio of discordant cells across Wave 1 and Wave 3 (effect size). Moderate effect sizes were assumed, and a priori power was assumed to be >0.80.

Third, we evaluated the social return on investment (SROI) of civil legal aid. SROI analyses extend outcomes (i.e., changes directly measured within a program or project) to impacts (i.e., the inferred net effects linked to a program or project over time) and differ from traditional financial return on investment due in that they do not assume that benefits directly return to the originating funder (Reference Then, Schober, Rauscher and KehlThen et al., 2017). We calculated the overall SROI as (benefits − costs)/costs. The benefits were based on estimated income impacts (i.e., the estimated change in income of participants across time) and cost-efficiency of accessing civil legal aid (i.e., the cost difference of service provision of legal aid relative to a private attorney at market rate) after adjusting for deadweight, drop-off, duration, and effect attribution (Reference Then, Schober, Rauscher and KehlThen et al., 2017). Deadweight adjusts for natural effects or changes in an outcome (i.e., income) over time that would have likely occurred regardless of intervention. Drop-off adjusts for the reasonable reduction of the impact effect of the intervention over time. For example, participants may differentially retain the amount of income gain across time, and attributable intervention effects are assumed to decrease over time. Duration of the outcome, or the benefit period, considers how long the impact of the intervention on the outcome will last after the intervention has ended. Attribution addresses the proportion of the impact that was due to the contribution of other programs or services received outside of the intervention being examined. Deadweight, drop-off, and attribution often adjust the measured outcomes downward, whereas duration typically increases the measured outcomes across time (Reference Then, Schober, Rauscher and KehlThen et al., 2017). For the impact of duration and drop-off of income, we estimated a boost hypothesis across time, with a boost assuming a short-term income gain that plateaus as opposed to an upward shift that assumes an ongoing income increase across time. Income benefits were a function of these adjusted amounts. Additionally, deadweight was adjusted based on previous experimental studies that explored offers of representation and actual receipt of representation (Reference Greiner and PattanayakGreiner & Pattanayak, 2012).

The SROI total benefit was based on the combination of income gains of participants and the lower cost of accessing justice through legal aid. We estimated the costs of civil legal services as the sum of the product of hours spent on a participant's case and an average of $70 per hour of legal aid time (ILA, 2018). Means, medians, and standard deviations of all income sources are presented in Table 2. We included both family law cases and civil protective orders in this study. Because prior research supported that case type and amount of service did not predict outcomes (Reference Hartley and RennerHartley & Renner, 2016), we collapsed case type and quantity.

RESULTS

Changes in income

Research Question 1: Did overall personal and private income increase, and did public benefits income decrease across time?

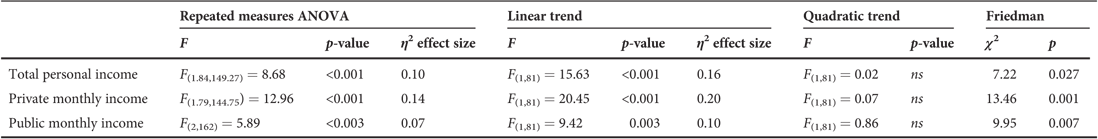

We used repeated-measures ANOVA with the Huynh-Feldt correction, Friedman test, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test to analyze changes in overall personal income across time. To account for skewed data distribution and to explore potential statistical methods bias, supplemental Friedman nonparametric repeated measures tests were used to test ranks across time in total personal income (private and public benefits income combined; see Table 3).

Table 3. Overall changes in income across waves 1, 2, and 3 (N = 82)

The mean and rank in total, private, and public benefits income significantly changed across Waves 1, 2, and 3 (n = 82; Table 3). Increases in women's mean total monthly income (combined private and public) and private income were significant between all three waves. Public benefits income significantly decreased between Waves 1 and 3 and between Waves 2 and 3 but did not significantly change between Waves 1 and 2 (Table 4). The results of nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests supported the parametric findings. Women retained through Wave 3 (n = 82) and those retained through Wave 2 (n = 27) reported increases in total and private income from Wave 1 to 2 across both wave retention groups. Those only retained through Wave 2 reported higher total and private income overall, but we found no significant time by retention wave interactions (Table 5). There were no changes across time (Wave 1 to 2) or retention wave for public benefits income.

Table 4. Changes by wave in categories of monthly income, paired comparisons (N = 82)

Table 5. Repeated measures ANOVA: Income by wave of retention, Wave 2 versus 3 (N = 109)

Research Question 2: What types of private income increased across time?

Similar to overall private income increases, mean monthly wage income significantly increased between Waves 1 and 3, Waves 1 and 2, and Waves 2 and 3. Monthly child support income significantly increased between Waves 1 and 3 and Waves 1 and 2 but not between Waves 2 and 3 (Tables 6 and 7). The average increases from Wave 1 to 3 of wages (62%) and child support (11%) accounted for the majority (73%) of the average personal income changes across the same time period (n = 82). The nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test further supported the direction of the parametric findings. Only the nonparametric Friedman test supported changes in income from friends and family money. Due to discordant parametric and nonparametric findings, we excluded the statistical significance of the small effects of money from friends and family from further analyses.

Table 6. Type of income changes across time for participants retained through Wave 3 (N = 82)

Table 7. Type income changes by wave, paired comparisons (N = 82)

In the supplemental analyses, although total private income increased by wave of retention, those retained through Wave 3 (n = 82) had gains between Wave 1 and 2 primarily based on wages and child support whereas those who discontinued after Wave 2 (n = 27) had gains primarily based on money from a new partner (Table 8). For those retained through Wave 3, the private income increases between Waves 1 and 2 were mostly linked to wages (44%) and child support (27%). For those retained through Wave 2, the increases were almost solely linked to money from a new partner.

Table 8. Mean differences of income between Waves 1 and 2 within retention group

Research Question 3: What types of public benefit income decreased across time?

Based on parametric statistical tests, SNAP (food stamps) significantly decreased between Waves 1 and 3, Waves 1 and 2, and Waves 2 and 3 (Tables 6 and 7). The average SNAP benefit decrease from Waves 1 to 3 accounted for the majority (61%) of the public benefit decrease across the same time period. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test results supported that money from SNAP was not statistically significantly lower at Wave 2 than at Wave 1 (Z = 1.50, p = 0.067) but was statistically lower at Wave 3 than at Wave 1 (Z = 3.32, p = 0.000) and at Wave 3 than at Wave 2 (Z = 3.05, p = 0.001). Based on discordant findings between parametric and nonparametric statistical tests, the significant change of decreasing SNAP income between Waves 1 and 2 was considered statistically nonsignificant due to potential statistical method bias. Only the nonparametric Friedman test supported changes in income from FIP. Due to discordant findings, we excluded the statistical significance of the small effects of FIP from further analyses.

Supplemental analyses supported that when combining or separating those continuing through Wave 3 and those discontinuing after Wave 2, overall public benefits income decreases were not significant between Waves 1 and 2 (Tables 5 and 8). Overall, public benefits income did not decrease between Waves 1 and 2 when combining groups (n = 109; Table 5). Participants who discontinued the study after Wave 2 reported significantly decreased SNAP income (Table 8). However, unlike those participants who were retained through Wave 3, the decrease in SNAP between Wave 1 and 2 among those who were only retained through Wave 2 was maintained during the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (Z = 2.13, p = 0.017).

Research Question 4: Does the proportion of women below the federal poverty level decrease across time?

Table 9 displays the changes within poverty status of the study participants from Wave 1 to Wave 3. In total, 18 women shifted out of poverty, 5 women shifted into poverty and the remainder experienced no change. McNemar's test showed there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of women above the federal poverty line at Wave 3 (following receipt of civil legal aid services) compared to the proportion of women above the federal poverty line at Wave 1 (when beginning to receive civil legal aid services) (χ 2 = 6.26, p = 0.01). The discordant odds ratio was also significant, meaning the odds of women being in poverty 1 year after receipt of civil legal services were less than before receiving legal services (OR = 0.28), indicative of a moderate to large effect size (Reference CitromeCitrome, 2014).

Table 9. Poverty status of study participants from Wave 1 to Wave 3

Social return on investment

Research Question 1: What was the social return on investment impact of civil legal aid services among women who experienced IPV?

First, we calculated the mean differences in overall monthly personal income between Waves 1 and 2 among participants only retained through Wave 2 (n = 27) and those retained through Wave 3 (n = 82) ($308.48 and $232.32, respectively). Then, we applied the same calculation for the difference between Waves 2 and 3 for those participants retained through Wave 3, with a difference of $208.28 found. Five cases with unreasonably high income or missing income data during Wave 1, as well as 36 participants who were assessed in Wave 1 but were not retained in Wave 2, had their estimated gains per month set to $0. Third, the effect size (eta squared) of overall income changes for participants retained in Wave 2 and Wave 3 was adjusted proportionally to account for deadweight. In this case, a small effect size of 0.01 (eta squared) was subtracted from the original effect size (eta squared) and then divided by the original effect size. This deadweight adjustment was calculated as 91.5% of the effect for total income changes between Wave 1 and 2 for participants retained through Wave 2; 87.7% of the effect of Wave 1 to 2 changes for participants retained through Wave 3; 73.7% of the effect of Wave 2 to 3 changes for participants retained through Wave 3; and 93.8% of the effect Wave 1 to 3 changes for participants retained through Wave 3. Fourth, we estimated the attribution effect of legal aid representation on the case outcomes for divorce and orders of protection based on the attributable risk identified in previous research (92% and 76%, respectively; Reference Degnan, Ferriss, Greiner and SommersDegnan et al., 2018; Reference MurphyMurphy, 2003). We based the average attributable risk on the proportion of case types, arriving at a program effect attribution of 81.6%. Fifth, the duration of the effect was assumed to be 5 years. Sixth, we estimated drop-off based on measured patterns of attrition across waves. After the last measured period, the drop-off was assumed to be 75% for the first 6-month period after measurement and was multiplied by 66.7% for each subsequent 6-month period, with the drop-off effect estimated downward to 3% for months 55–60 for participants retained through Wave 2, and 4% for those retained through Wave 3. This means that almost all projected value of income gains had been lost by the end of 5 years. Additionally, after 1 year, we further decreased the effect (additional drop-off beyond attrition) cumulatively by 1% every sixth months to account for cost of living adjustments across time (a multiplier of 99% for months 13–18 and 92% for months 55–60) (Social Security Administration, 2019).

The income impact was further adjusted between months 1 and 6 for women retained through Wave 2 and 1–12 for women retained through Wave 3 instead of assuming that the average monthly gain applied equally to all months in which gains were measured. For example, if there was a monthly gain between Months 1 and 6 of $232, then one-sixth of the effect was linked to Month 1, two-sixths in Months 2, and incrementally increasing through Month 6 that assumed the full monthly gain. The average income gains adjusting for attribution, deadweight, drop-off, and duration for women retained through Waves 2 and 3 are depicted in Figure 1. The estimates in Figure 1 assumed that income gains did not increase after the last wave of measurement (incomes increase then plateau, as specified in the boost hypothesis, which holds that there is a short-term increase after services that maintains across time). In other words, gains were maximized shortly after services (within 12 months) and then plateaued for women maintaining the gains across time. We did not expect all women to maintain gains, and those lost to follow-up shifted to $0 (baseline) for subsequent periods after drop-off. For low-income service utilizers, however, one could argue that this estimate is too conservative. Among women filing for a CPO and assuming legal aid to be a form of social welfare assistance, a comparison of income gains of women utilizing public assistance to those who did not, supports that the relative income increase may be higher than a zero slope. For social assistance utilizers, filing orders of protection could help to maintain income gains across time (Reference Hughes and BrushHughes & Brush, 2015).

Figure 1. Average income gains by month by wave of retention

Lastly, after estimating adjusted income impact (income benefit), we estimated costs. To conservatively conduct the SROI calculation, the costs were based on the hours of legal service provided to all participants who began the study during Wave 1, not only those participants retained through Waves 2 or 3. This meant that costs were associated with provision to all participants evaluated in Wave 1 (n = 150), but income benefits were linked only to those completing at least Wave 2 (n = 109). The income benefit for all women in the sample income gains under the boost hypothesis was $591,031. The costs for legal service provision were estimated at $245,347 (approximately 3505 h at $70 per hour). As an additional conservative adjustment, participants with missing or inaccurate data (n = 5) or those with data in Wave 1 but neither Waves 2 or 3 (n = 36) had their costs included in the SROI cost calculations, while their assumed benefits were set to zero resulting in a downward adjustment to the income-based SROI. The income-based SROI, therefore, was estimated to be 141% for the boost hypothesis—meaning that for every $1 spent on legal aid, $2.41 of attributable income was gained.

These income-based SROI analyses exclude the cost-efficiency of accessing justice via civil legal aid. The cost of accessing an hour of civil legal aid was estimated to be $70–$129 lower in cost per hour than the private sector rate. We used an attribution of 78% to adjust for the effect of offering and utilizing civil legal aid services (Reference Degnan, Ferriss, Greiner and SommersDegnan et al., 2018). The cost-efficiency benefit of civil legal aid as a point of service was between $191,370 and $352,668. Collectively, using the boost income benefit and mid-point cost-efficiency benefits, the total SROI was estimated to be 252%—meaning that for every $1 spent on legal aid, $3.52 of income or access to justice was gained.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the material empowerment effect of legal assistance among lower-income women who experienced IPV. The study purpose was twofold: (1) to evaluate changes in private and public benefit income over 1 year among women who experienced IPV and received civil legal aid services, and (2) to estimate the social return on investment (SROI) of providing civil legal aid services to women who experience IPV. We found that receipt of civil legal aid, specifically family law services and assistance for CPOs, was associated with increases in women's total and private income and decreases in reliance on public benefit income. Spreading the SROI income gain across the women assessed in Waves 2 and/or 3 supported an average income gain of approximately $5500 over time. Looking across all types of private income reported, we found that a significant portion of the average private income increase from Wave 1 to 3 was due to wage increases. Women who experience IPV frequently experience employment instability (i.e., fewer weeks worked in a calendar year, employment termination, and fewer number of months at the same job) (Reference Adams, Tolman, Bybee, Sullivan and KennedyAdams et al., 2012; Reference Tolman and WangTolman & Wang, 2005) often due to their partners' interference with their ability to work. Exiting an abusive relationship through civil legal aid assistance appears to positively impact women's wage-earning, thereby reducing the economic inequity of women experiencing IPV.

Public benefits income decreased between Wave 1 and 3, most notably between Waves 2 and 3. This was not unexpected because as women's private income increased over time, they likely became ineligible for means-tested programs such as SNAP. Due to the structure of the U.S. social welfare system, many public income services are means-tested, wherein a person or family has to fall below a threshold to qualify, often set relative to the Federal Poverty Levels (FPLs). For example, the threshold to qualify for the National School Lunch Program is ≤130% below the FPL, ≤100% for TANF, ≤100–130% for SNAP, ≤138% for Medicaid, and ≤185% for WIC (Reference MoffittMoffitt, 2018). The decrease in means-tested public benefits also makes sense because 22% (n = 18) of women in the study shifted out of poverty at the 1-year mark compared to baseline. The odds of women being in poverty 1 year after the initial receipt of civil legal services were approximately 2.5 times lower than before receiving legal services. Related to the absolute increases in income found in this study, some women transitioned out of poverty.

We statistically tested income gains (continuous) and poverty status changes (discrete threshold) among women who had experienced IPV and received legal aid services, finding that income increased and poverty decreased. To some degree, poverty is a more arbitrary and less informative financial position measure than continuous income. In our study, women's incomes increased overall, and they were less likely to be in poverty. However, as supported by the decreases in SNAP income we found, means-tested social welfare can create losses in public income as private income exceeds set thresholds.

Our poverty status changes used the Federal Poverty Levels, which were originally established based on multiplying the cost of family food subsistence by three (Reference FisherFisher, 1997). However, more recent discussions regarding income thresholds have suggested the minimum income for healthy living (MIHL) should encompass additional factors such as nutrition, housing, and medical care (Reference Morris, Wilkinson, Dangour, Deeming and FletcherMorris et al., 2007) or the level of income needed to produce more perceived well-being (Reference PaynePayne, 2017). Future research on the material empowerment effects of legal aid services should assess a more expanded measure of income adequacy.

The estimated SROI was positive for income gains alone, as well as income gains plus cost-efficiency of accessing civil justice through legal aid. For every $1 of legal aid service, there was an estimated income benefit of $2.41. Given that most people with civil legal issues are not represented by legal counsel and considering the remarkable impact of legal representation on case outcomes (Reference Caplan, Liebman and SandefurCaplan et al., 2019), cost-efficient access to civil legal services, like legal aid, must be part of the solution to the justice gap.

The positive SROI supports that more investment could be made in legal aid while maintaining positive societal benefits. It should be noted that this was a quantitative study, and the estimated benefits were income changes. We did not explore the qualitative impacts of any income increases or women's perception of their legal representation experience. Previous research among women who received civil legal aid after experiencing IPV concluded that subjective experiences (psychosocial empowerment) improved (Reference Hartley and RennerHartley & Renner, 2018), and women's objective experiences (material empowerment) also changed (Reference Hartley and RennerHartley & Renner, 2016).

Limitations

Selection bias in recruitment may limit the generalizability of our results. We did not have information about nonparticipants, so we could not examine possible nonresponse bias of women who declined to learn more about the study or did not seek assistance from legal aid at all. It could be that service utilizers apply more personal or colletive agency in their problem-solving, in addition to being more likely to engage in proxy agency (i.e., seeking and maintaining help from a lawyer). Adopters of legal innovations could socioecologically differ from nonadopters. ILA has income restrictions for case eligibility and prioritizes cases due to limited resources. As such, our findings may only apply to lower-income women who faced more imminent legal needs because of their experiences of violence. The sample focused on women who contacted ILA for one of the two most commonly sought types of legal services, assistance with a CPO or a family law case. Results may differ for women seeking other types of legal services or not seeking help at all.

Another potential limitation was the use of self-reported data, which may be limited by recall and social desirability. Women self-reported their private and public benefits income, but there was no objective verification of these data. We presumed any misreporting was steady across time and adjusted for underreporting (missing data) in the SROI analysis. Research comparing administrative income and survey income supports high correlations between survey and administrative data and that most people accurately report income. However, there is a trend toward underreporting public benefits income compared to known transfers based on administrative data (Reference Moore, Stinson and WelniakMoore et al., 2000). Survey methods are more sensitive to collecting income data that may not be reported administratively to the Internal Revenue Service, such as tips, cash earnings, or under the table income (Reference Bee and RothbaumBee & Rothbaum, 2019).

True income likely falls between administrative and survey estimates (Reference Bee and RothbaumBee & Rothbaum, 2019), and both survey and administrative data include measurement error and bias (Reference Oberski, Kirchner, Eckman and KreuterOberski et al., 2017). Although some argue that using administrative data is more accurate, using these data presents various ethical and feasibility issues, such as gaining access to information across multiple agencies and systems to estimate overall income. Survey data can, in some cases, be more feasible to collect and is seemingly a reasonable representation of administrative data overall. Research also supports that lower-income people may report more overall income in surveys relative to administrative data (Reference Bee and RothbaumBee & Rothbaum, 2019).

A third limitation pertains to court outcomes. We did not objectively track the outcome of the legal representation via court records. We can reasonably assume a “successful” court finding (e.g., receiving a favorable child support award) would result in better outcomes than an “unsuccessful” one (e.g., being denied an order of protection).

Retention was also a challenge and may have influenced the results. Only three-quarters of the Wave 1 sample was retained for Wave 2, and only three-quarters of these women were retained for Wave 3. Whether women were retained or not was not significantly associated with their overall income or most demographic characteristics. Still, there may be unobserved characteristics among the participants that accounted for their income improvements that were not captured in our data collection. Despite retention not being linked to total, private, or public benefits income overall, this study did support a potential bias in retention across time, as women with income increases due to earning job-related wages or garnering child support were retained longer than women with income gains primarily based on the income of a new partner.

Finally, we did not have a comparison group of women who experienced IPV but did not receive civil legal services. We utilized SROI methods (Reference Then, Schober, Rauscher and KehlThen et al., 2017) to adjust study outcomes and to account for the lack of a comparison group in this longitudinal panel study. When evaluating interventions or as part of applied research, there are often trade-offs along the dimensions of feasibility, utility, and accuracy, especially when considering vulnerable, marginalized, or disadvantaged populations where comparison or control groups may not be ethically or practically feasible (Reference Yarbrough, Shulha, Hopson and CaruthersYarbrough et al., 2011). Although SROI methods make it feasible to estimate net effects of interventions on a scale useful to policymakers, it is possible accuracy could be traded for feasibility and utility. Future studies should more directly address these limitations to adequately examine the benefits of receiving civil legal services among women who experience IPV. They should also examine the effects of different characteristics of civil legal representation (i.e., representation type, quality of representation, case decision outcomes) on various social impacts (e.g., objective changes in income, health, violence, service utilization) across time.

Implications for policy

The U.S. invests in civil legal aid far less than comparable countries (Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2014) and falls well outside of other high income countries regarding access to and availability of civil legal aid (World Justice Project, 2019). The U.S.’s expenditures on civil legal aid is less than seven-thousandths of 1% of the gross domestic product (GDP) (Reference HousemanHouseman, 2015; Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2014). Relative to the GDP of respective countries, the U.S. spends less than one-tenth of the amount of the United Kingdom on civil legal aid, one-sixth of Norway, less than one-quarter of Canada, and less than one-half of Germany (Reference JohnsonJohnson, 2014).

The primary sources of civil legal assistance for low-income Americans are state legal aid organizations that receive most of their funding from the LSC. In 2015, LSC provided $343 million in grants to state legal aid agencies (LSC, 2015). However, annually, approximately half the eligible low-income individuals who contacted an LSC funded legal-aid agency were turned down for services (LSC, 2017). This represents approximately one million cases each year that—despite having legal merit—are rejected by legal aid offices because they lack the resources to serve these clients (LSC, 2017). Funding for civil legal aid is seen as unequal across and within states (Reference HousemanHouseman, 2015) and although programs in urban areas may have adequate funding, people in rural areas have a much lower level of access to legal services (Brennan Center for Justice, 2003).

Our study supports a potentially positive social return of access to justice through civil legal aid via improvements in economic self-sufficiency. Access to justice improves through the cost-efficiency of utilizing legal aid as a lower-cost access point compared to the private market rate. As such, we need to examine federal, state, local, and philanthropic avenues for increasing the legal assistance available to individuals who experience IPV who cannot afford private attorneys by advocating for increased funding for state legal aid agencies (Institute for Law and Justice, 2005). Reference AbelAbel (2006) argues that funding should be prioritized for institutional providers, like state legal aid agencies, because the services they provide are higher quality than private attorneys as their staff has specialized training in IPV, and they are able to deliver more cost-efficient services.

A limitation of legal aid programs is their income means eligibility test. Some women who experience IPV may not be eligible for state legal aid services but still lack sufficient income to hire a private attorney. Although legal aid programs have some flexibility in disallowing income and assets based on a woman's lack of access to the perpetrator's income, a woman's income still needs to be less than 125% of the federal poverty level to receive assistance. Pro bono assistance by private practice attorneys and university legal clinics may help to address this gap (Institute for Law and Justice, 2005), as would encouraging states to allow the use of victim compensation funds to pay for legal services for victims of IPV.