The diffusion of legal institutions, policies, and techniques has tremendous consequences for the interaction between law and society. New technologies' diffusion can potentially revolutionize legal practice, general assumptions, and material outcomes. These consequences have followed many innovations, including alternative dispute resolution (Reference Edelman and SuchmanEdelman and Suchman 1999), rights talk (Reference MilnerMilner 1989), problem-centered courts (Reference NolanNolan 2001), and “mega” law firms (Reference Galanter, Dingwall and LewisGalanter 1983). Significantly, it is these innovations' diffusion across organizations and states, not just their emergence that increases their ability to affect legal processes and outcomes. Understanding how legal innovations diffuse is, thus, necessary to understand law's impact on society.

Unfortunately, scholars rarely investigate the mechanisms that spread criminal justice innovations (Reference Grattet, Jenness and CurryGrattet, Jenness, and Curry 1998). Studies of penal change have primarily analyzed innovations or their widespread consequences. Thus, to understand the popularity of three strikes laws (Reference Zimring, Kamin and HawkinsZimring, Kamin, Hawkins 2001), supermaximum-security prisons (Reference ReiterReiter 2012), or “sunbelt justice” (the strange mixture of racially tinged punitiveness and a cost-conscious small-government ethos) (Reference LynchLynch 2010), scholars study the first instance or the most copied examples. While this approach is vital, similarly enthusiastic examinations of diffusion are necessary to better understand change.

Instead, scholars treat diffusion as a natural consequence of innovation. They implicitly posit that whatever zeitgeist caused the innovation was present elsewhere, albeit less intensely. Alternatively, scholars argue widespread belief in innovations' efficacy at reducing crime, or generating political capital, explain jurisdictions’ adoption. Indeed, scholars have amply illustrated the political utility of adopting tough-on-crime policies (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997; Reference Campbell and SchoenfeldCampbell and Schoenfeld 2013; Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2006; Reference SimonSimon 2007). However, this approach overlooks the mechanisms by which innovations spread and understates the contingent nature of diffusion. An emphasis on diffusion would interrogate the factors motivating different jurisdictions’ adoption of new practices.

Several exceptional studies have examined the diffusion rather than emergence of criminal law technologies. Studies of community-based policing (Reference CrankCrank 1994), COMPSTAT (Reference Willis, Mastrofski and WeisburdWillis, Mastrofski, and Weisburd 2007), and hate crime definitions (Reference Grattet and JennessGrattet and Jenness 2005) have carefully reconstructed police departments’ decision-making processes, highlighting the mechanisms carrying innovations to subsequent adopters. Other scholars have quantitatively modeled worldwide changes in sex crime laws (Reference Frank, Camp and BoutcherFrank, Camp, and Boutcher 2010), the national proliferation of hate crime laws (Reference Grattet, Jenness and CurryGrattet, Jenness, and Curry 1998), or the Progressive-Era diffusion of juvenile justice programs (Reference SuttonSutton 1988, Reference Sutton1990) and mental institutions (Reference SuttonSutton 1991). However, documenting a general shift in approaches to criminal justice without identifying the mechanisms that spread innovations remains the dominant framework for both historical and contemporary studies.

Departing from this trend, this article examines the diffusion of one of the most significant innovations in legal history: the modern prison. By the Civil War, more than 30 state prisons had been established, at least one in almost every state. While the prison's early history has enjoyed great scholarly attention,Footnote 1 most accounts explain the prison's initial emergence, design, and functioning. The prison's subsequent diffusion has received far less attention. Indeed, leading accounts convincingly explain the prison's birth in large, Eastern-seaboard cities through cultural, political, and economic factors (Reference FoucaultFoucault 1977; Reference RothmanRothman 1971; Reference Rusche and KirchheimerRusche and Kirchheimer 1939). However, the prison's diffusion was largely divorced from these same factors. These standard frameworks cannot explain why the prison diffused so rapidly, widely, and homogeneously across the country, despite great cultural, political, and economic diversity. This subsequent diffusion is an equally important, but largely unexplained, part of prison history.

Using a neo-institutional perspective, this article re-examines the rise of the prison, focusing on its diffusion across the United States. Neo-institutional theory (Reference DiMaggio and PowellDiMaggio and Powell 1983; Reference Meyer and RowanMeyer and Rowan 1977) emphasizes the influence of normative prescriptions and cognitive models within an organizational field, instead of technical imperatives or local needs. Three features of the prison's diffusion suggest the importance of field-level developments: this diffusion was rapid (20 of the 26 existing states adopted prisons in the first two decades), widespread (affecting the North and the South, frontier and established states), and homogenous (almost all prisons adopted the same model of confinement). Local factors would likely have produced greater variation in the timing, location, and character of prisons adopted.

Drawing on a wealth of primary and secondary sources, this article grounds the prison's diffusion in field-level pressures that stretched across the country's diverse terrain. Prisons initially emerged as technical solutions to problems in Northeastern cities; once developed, however, prisons became symbols of national progress. Reliance on outdated penal technologies became a liability. Frontier and Southern states, despite their distinctive cultural, political, and economic needs, adopted prisons to avoid criticism. While the prison spread across the country, other institutional pressures encouraged similarity of design. Uncertainty surrounding both the new prison technology and the goals of punishment incentivized states to copy existing, apparently successful models of confinement. Moreover, penal reformers’ impassioned debate over the dangers and benefits of competing designs encouraged states to adopt a particular model of confinement. Finally, a variety of contingent historical factors reinforced these two pressures, leading to the prison's incredibly homogenous diffusion. This neo-institutional framework usefully supplements existing theories of the prison's development by moving beyond its initial innovation.

The next section reviews leading explanations of early prison development. While noting that these theories persuasively account for the prison's birth in major northern coastal cities, this article questions their ability to explain the prison's adoption across a diverse array of states with different cultural, economic, and political contexts. The following section outlines key features of neo-institutional theory, especially the mechanisms responsible for diffusion of this kind. The penultimate section exhibits a neo-institutional account of antebellum prison diffusion. There I first discuss the temporal and spatial dimensions of diffusion, linking prison adoption to early adopters’ technical needs and later adopters’ legitimacy concerns. I then show how the uniformity of prison design must be attributed to mimetic and normative pressures, reinforced by contingent factors. The final section discusses this article's theoretical contribution, the value of treating diffusion separately from innovation, particularly for criminal justice developments throughout history, especially the mass incarceration era.

Prior Research

An extensive body of scholarship has emerged to explain the rise of the prison. Three particularly influential accounts describe the cultural, political, and economic factors behind the prison's origins. While each account primarily examines the transition from corporal and capital punishment to incarceration, they implicitly speak to the prison's subsequent popularity and diffusion. However, these accounts are more useful for explaining the prison's initial innovation than its diffusion.

First, Reference RothmanRothman (1971) suggests that upper- and middle-class reformers in the Jacksonian Era reacted to their social order's (perceived) disintegration. In the wake of revolutionary social changes, they turned to prisons and other asylums to impose strict order on troublesome populations and cure the most glaring manifestations of disorder—crime, poverty, insanity. The prison, they believed, would replace traditional social institutions (church, family, tight-knit community) the authority of which was fading in the postrevolutionary period. The prisons’ emergence, thus, resulted from changing cultural perceptions following seismic shifts in social, political, and economic relations (see also Reference HirschHirsch 1992).

Second, focusing primarily on Europe, Reference FoucaultFoucault (1977) suggests that older forms of punishment, especially scaffold-based executions, became increasingly problematic technologies of power. Rather than illustrating the monarch's political might, they became liabilities as crowds cheered the condemned or picked audience members’ pockets, clearly undeterred by the spectacle. As societies entered new economic and social orders requiring greater restraint and fixed work schedules (disrupted by day-long execution festivals), authorities preferred more “efficient” forms of punishment. In prison, surveillance and control mechanisms could teach inmates to internalize self-control, “discipline” themselves, and ultimately behave as authorities wanted—without the expensive, time-consuming, and otherwise problematic penal festivals. Prisons, thus, represented a more efficient and appropriate exercise of power than earlier penal technologies (see also Reference MeranzeMeranze 1996).

Finally, Reference Rusche and KirchheimerRusche and Kirchheimer (1939) suggest prisons emerged from the shift toward a more industrial economic order in Europe and America. Penality follows the current economic order's labor needs. The sixteenth century witnessed an increased demand for labor following population declines and the transition to mercantilism. The existing, heavy reliance on capital and corporal punishments suddenly appeared wasteful to social elites who needed productive bodies; alternatives like galley slavery, convict transportation, and houses of correction appeared more attractive. Similarly, Rusche and Kirchheimer argue that America experienced a significant labor demand during industrialization. Factory-style prisons, which preserved and extracted labor from productive bodies, represented attractive alternatives to capital punishment (Reference Rusche and KirchheimerRusche and Kirchheimer 1939: 127–34). The particular needs of the labor market, thus, accounted for the turn to modern prisons in the United States (see also Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008; Reference Melossi and PavariniMelossi and Pavarini 1981).

While scholars have identified theoretical or factual problems with each, these accounts have nevertheless been tremendously influential. Indeed, this article does not challenge these mechanisms as inspiring the initial idea of reform or even early support for prisons. These accounts plausibly explain penal reform's salience in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. These large cities had active penal reform movements while Philadelphia and New York were penal innovators for the first five decades of American independence. Their population density concentrated and rendered visible social ills like poverty and criminality (Katz, 1986: 16). They had strong labor pools and were among the first to witness unionization (Reference Geffen and WeigleyGeffen 1982; Reference WilentzWilentz 1984). These cities also hosted a large merchant and middle class, the groups most supportive of penal reform (Reference ColvinColvin 1997; Reference WaltersWalters 1978). Existing theories, thus, explain early penal reform efforts in New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, states with unparalleled levels of urbanization.

These compelling theories cannot account for the prison's subsequent diffusion across a culturally, politically, and economically diverse terrain. Each theory assumes that the same mechanism is responsible for both the initial idea of the prison and its diffusion. However, these mechanisms—the perception of social disorder, the appeal of disciplinary power, and the demand for labor—were not static across time or place. The prison's antebellum diffusion did not reflect this variation.

Rapid, Widespread, and Homogenous Diffusion

Three noteworthy characteristics of the modern prison's diffusion cast doubt on these explanations: First, the diffusion was incredibly rapid. 17 prisons opened between 1825 and 1836 (including eight between 1828 and 1831). By the early 1830s, more than 50 percent of states had adopted a prison. By 1840, 20 of the existing 26 states, and the District of Columbia, had adopted a prison; several states built more than one. Thereafter, new states entering the Union quickly authorized and built prisons (if they had not already). Three decades after the first modern prison opened, most American states had adopted a state prison. (See Figure 1.) If factors like social anxiety or labor markets drove this adoption, adoption should have been slower as localities experienced these needs differentially over time.

Figure 1. The Cumulative Diffusion of Modern Prisons Across States, 1821–1860. This Graph Illustrates the Portion of States (By Year) that had a Prison, Stratified by Their Choice of the Auburn System or Pennsylvania System. Although Several States Adopted more than One Prison, Each State is Represented Only Once. A Reference Line is Imposed at 1835. As the Number of States in the Union Increased Over Time, Both the Numerator and Denominator Expand Over Time. Source: Dataset Compiled by Author from State Statutes, Other Primary Sources, and Secondary Sources; Available on Request. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Second, the diffusion was widespread. Prisons were adopted in nearly every state by the beginning of the Civil War; only Delaware and (the brand-new state) West Virginia lacked state prisons by 1867 (Reference Wines and DwightWines and Dwight 1867: 86, 100). Prisons were adopted in frontier states and more established coastal states, and more surprisingly, in both the North and the South. Early frontier states Kentucky and Ohio adopted state prisons simultaneously with their coastal counterparts. As the frontier extended, former territories (Michigan, Iowa, Texas, Wisconsin, California, and Minnesota) adopted prisons upon statehood, or even before (states listed in the order of prison adoption, sometimes before statehood). Southern states (Kentucky, Virginia, Maryland, Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana) adopted prisons concurrently with their northern counterparts, despite their largely agrarian, slave-based economies and racially stratified criminal justice system. The Carolinas and Florida were the lone Southern hold-outs by 1860. However, as Reference AyersAyers (1984: 35) explains, Florida was “virtually empty throughout the antebellum era, … and the Carolinians fiercely debated the issue for decades.” If cultural, economic, or political factors drove prison adoption as theorized, we should observe greater regional variation.Footnote 2

Finally, the resulting carceral field was highly homogenous: only two models of prison discipline were developed and the vast majority of prisons built followed the same model. Under New York's popular Auburn System, prisoners worked in large rooms performing factory-like labor and retreated to solitary cells at night. Under the Pennsylvania System, prisoners remained in solitary cells where they performed workshop-style labor and received visits from prison personnel. French emissaries Gustave de Beaumont and Alexis de Tocqueville inventoried America's prisons in 1831: Auburn State Prison and “Sing-Sing, in the State of New York; Wethersfield, in Connecticut; Boston, in Massachusetts; Baltimore, in Maryland” and recent additions in Kentucky, Tennessee, Maine, and Vermont followed the Auburn model. “On the other side, Pennsylvania stands quite alone” (Reference de G. and de Tocquevillede Beaumont and de Tocqueville 1833: 20). By 1860, almost all the country's 32 modern prisons followed the Auburn System.Footnote 3 (See Figure 2.) Only three states (four prisons) adopted the Pennsylvania System, including Quaker strongholds, New Jersey (1836–1858) and Rhode Island (1838–1844). After 1858, only Pennsylvania's two prisons followed the flagging system. If states adopted prisons according to their local needs, we should see greater variation in the kind of prison adopted as states would customize prison structures to their specific circumstances. Instead, the variation observed was minimal and short lived.

Figure 2. The Diffusion of Modern Prisons in 1821, 1840, and 1860. Dark Grey States Represent Adoption of the Pennsylvania System. Black States Represent Adoption of the Auburn System. White states Represent Those States in the Union that Lacked Modern State Prisons. Light Grey States Represent Territories or Other Lands Not Yet Admitted to the Union. Source: Dataset Compiled by Author from State Statutes, Other Primary Sources, and Secondary Sources; Available on Request.

While cultural, political, and economic factors may have played a large role in precipitating the prison's birth in more urbanized, industrialized states, they cannot explain its diffusion. Consequently, we lack a compelling account that explains why such diverse societies adopted prisons at all, let alone strikingly similar prisons. We must search for new theoretical frameworks that complement these existing accounts, while moving beyond the particular features of the states that created modern prisons. In part, this involves shifting the analytical locus from local settings to the messy interactions between and among states (legislatures), prisons (administrators), and the public (especially reformers). Neo-institutional theory can motivate this shift in focus and account for the prison's diffusion.

Theoretical Framework

Neo-institutional theory locates the causes of organizational behavior in collective understandings of legitimate behavior. Specifically, neo-institutional scholars argue that organizations visibly behave according to the normative demands and cognitive frameworks or expectations of their field (the aggregate of all similar organizations and their affiliates, e.g., regulators, resource-granting agencies, clients, competitors). Conformity with these norms or expectations conveys legitimacy; consequently, the norms, cognitive expectations, and legal regulations prevalent in the field determine what constitutes legitimate organizational forms or behaviors. These beliefs, rules, and cultural scripts can emerge organically and contingently in the field, or interested actors may manipulate them (Reference DiMaggio and PowellDiMaggio and Powell 1983; Reference Meyer and RowanMeyer and Rowan 1977). For neo-institutional theorists, legitimacy concerns are more influential than rationality (adopting the most efficient practices, policies, or structures to satisfy their technical needs), while field-level developments and organizations’ environments are frequently more influential than organizations’ local characteristics.

Nevertheless, neo-institutional scholars recognize that different organizations adopt innovative technologies or practices at different times for different reasons. As Reference Tolbert and ZuckerTolbert and Zucker (1983) have demonstrated, new structures may emerge as rational responses to technical problems. Organizations that adopt these structures early in the process do so because they are legally required or because the structure solves a particular problem. Over time, these structures become institutionalized: they become widely accepted or taken for granted as routine features of organizational practice or social life (Reference Tolbert and ZuckerTolbert and Zucker 1983: 25; see also Reference ZilberZilber 2006). Indeed, once a structure is institutionalized, failure to adopt it indicates nonconformity with the field's norms or rules, a mark of illegitimacy (Reference Meyer and RowanMeyer and Rowan 1977; Reference Tolbert and ZuckerTolbert and Zucker 1983). Thus, even organizations with no technical need for these structures will adopt them: the legitimacy of the structures themselves serves as the impetus for later adoption (Reference Tolbert and ZuckerTolbert and Zucker 1983: 35).

Neo-institutionalists also predict that, after new organizational forms are created, or when changes are imposed on an existing field, organizations involved in the same line of work will achieve significant structural similarity, or institutional isomorphism. Scholars argue that the pressure to adopt institutionalized structures encourages similarity in these new structures’ form or appearance. In their classic article, Reference DiMaggio and PowellDiMaggio and Powell (1983) outline the three mechanisms (“institutional pressures”) that produce institutional isomorphism (see also Reference Washington and VentrescaWashington and Ventresca 2004). First, through “coercive pressures,” resource-granting or regulating agencies can persuade organizations to adopt specific policies or structures or face the consequences (Reference EdelmanEdelman 1990, Reference Edelman, Abraham and Erlanger1992; Reference Tolbert and ZuckerTolbert and Zucker 1983). Second, organizations may imitate other, apparently successful organizations to minimize uncertainty surrounding their technology, goals, or environment, which imposes “mimetic pressures” (Reference McTague, Stainback and Tomaskovic-DeveyMcTague, Stainback, and Tomaskovic-Devey 2009; Reference Studer-EllisStuder-Ellis 1995). Finally, networks of professionals introduce “normative pressures” by advising organizations to adopt specific structures and by propagating “rational myths” (Reference Meyer and RowanMeyer and Rowan 1977), or stories about the utility or acceptability of particular structures or practices (Reference DiMaggio, Powell and DiMaggioDiMaggio 1991; Reference DobbinDobbin 2009). Remarkably, each of these mechanisms can exert pressure without actual evidence of these structures’ technical value (Reference DiMaggio and PowellDiMaggio and Powell 1983: 153).

Once a structure achieves widespread approval, organizations that fail to adopt it can face significant consequences to their legitimacy, and thus, to their ability to obtain resources, maintain autonomy, or even survive (Reference Meyer and RowanMeyer and Rowan 1977; Reference SuchmanSuchman 1995). While exceptions to institutional isomorphism have been demonstrated (Reference Kraatz and ZajacKraatz and Zajac 1996; Reference Strandgaard Pedersen and DobbinStrandgaard Pedersen and Dobbin 2006), it remains a central framework to explain diffusion patterns and organizational change in multiple organizational fields and multifarious types of organizations (e.g., schools, corporations, nonprofit organizations, countries) (Reference DiMaggio and PowellDiMaggio and Powell 1983).

Institutional mechanisms of diffusion have been demonstrated in criminal justice contexts. Legitimacy has been a powerful motivator driving criminal justice policies. While innovative police departments develop technologies to address particular problems, other police departments adopt these technologies, without customizing them to local needs, to appease local constituencies who believe in their utility, even where such technologies are inappropriate for the locale (Reference KatzKatz 2001; Reference Willis, Mastrofski and WeisburdWillis, Mastrofski, and Weisburd 2007).

Indeed, institutional pressures are especially likely to shape behavior in penal settings (Reference SuttonSutton 1996: 948). Mimetic pressures are likely because profound uncertainty surrounds penal goals and technologies. Punishment's traditional justifications (deterrence, rehabilitation, incapacitation, retribution) often offer conflicting recipes. Meanwhile, adopting new penal practices creates periods of novelty and, consequently, uncertainty about their effectiveness or their implementation. Normative pressures are likely to result from networks of experts expressing their judgment about penal policy. Today, this may be national networks of law enforcement or correctional personnel, including those trained in specialized university programs. In the nineteenth century, similar pressures were exerted by penal reformers (Reference SuttonSutton 1988, Reference Sutton1990). While normative and mimetic pressures may be present in penality during many periods, coercive pressures may be less common in general (Reference Grattet and JennessGrattet and Jenness 2005) and in the nineteenth century specifically. Coercive isomorphism may result when the federal government requires states to institute specific policies, or ties funding to policy adoption. However, the federal government's role in criminal justice was rather limited until the late twentieth century (Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2006). Thus, we should primarily expect mimetic and normative pressures within the nineteenth-century criminal justice setting.

A Neo-Institutional Account of Antebellum Prison Diffusion

This section offers a neo-institutional account of antebellum prison diffusion. Instead of focusing entirely on the first tumultuous experiments that produced the modern prison, this account privileges both the spatial and temporal aspects of diffusion. It, thus, accounts for the prison's early and later adoption and the regional variation in states’ motivations for adoption. Additionally, as the prison's diffusion is inextricably linked to the diffusion of the Auburn System, this section describes the mechanisms that diffused this model and established its dominance.

The Temporal-Spatial Diffusion of Modern Prisons

By the mid-nineteenth century, modern prisons populated the American North and South and both coasts, covering a great diversity of social, cultural, and political contexts. We cannot point to a single local variable (e.g., social anxiety, labor demands, or new limits on power) that transcends this diversity. Instead, field-wide dynamics, linking Southern states with Northern states and former territories with former colonies, account for this widespread diffusion: when one set of states initiated changes in punishment, it set precedents, provided models, and applied pressure on other states to follow.

To understand this process, we must examine the temporal and spatial dimensions of prison diffusion. While there were no spatial differences in the prison's adoption by the end of the period, spatial differences emerged in the timing of states’ adoption. These temporal-spatial trends can be attributed to a fundamental difference in the reasons why different states adopted the prison.

Early adopter states were driven by a perceived need that, supporters believed, modern prisons filled: their proto-prisons were deteriorating in the 1810s and 1820s. By contrast, late-adopter states were driven by legitimacy concerns: once the prison became sufficiently common, states that failed to adopt a prison appeared backward and even barbaric, relying on dilapidated jails and capital and corporal punishments. By adopting a modern prison, Deep-Southern states like Alabama and Mississippi could demonstrate conformity with their northern counterparts while former territories like Michigan and Minnesota could display the trappings of statehood. The historical narrative that follows explores the emergence and diffusion of modern prisons while addressing these temporal and spatial dimensions. This more dynamic account provides a fuller understanding of why the prison spread so widely and rapidly.

The Rise and Fall of Proto-Prisons, 1790s–1810s

After the Revolution, Americans grew increasingly uncomfortable with extant forms of punishment. Following several centuries of primacy, capital and corporal punishments declined during the eighteenth century. The former colonists, now masters of their own laws, revised their constitutions and penal codes to reduce the array of capital offenses. The new states, led by Pennsylvania, experimented with alternative forms of punishment, including public labor, to replace execution, whipping, branding, and other sanguinary punishments. Simultaneously, these states relied more extensively on local jails to maintain criminals for whom they had no other punishment (Reference BarnesBarnes 1921; Reference FriedmanFriedman 1993; Reference MeranzeMeranze 1996).

As states remodeled their dilapidated colonial jails and constructed new facilities, they created the first generation of state prisons (“penitentiary houses”). Colonial and European jails had contained a varied population including witnesses, debtors, vagrants, those awaiting trial, and condemned persons. Indeed, most inmates were held for administrative reasons; confinement was not considered punishment. This varied population, moreover, was often held together in large rooms, not segregated by sex, age, or criminality (Reference MeranzeMeranze 1996; Reference RothmanRothman 1971). By contrast, the new proto-prisons only confined convicted criminals, separated inmates by criminality and gender, and temporarily sent misbehaving prisoners to solitary cells (Reference MeranzeMeranze 1996: 196; Reference TeetersTeeters 1955: 19). The first proto-prison, Philadelphia's Walnut Street Prison, emerged in 1790, followed by New York City's Newgate Prison in 1796; by 1810, 9 of the 17 states had built a penitentiary house (Reference RothmanRothman 1971: 61). In the 1810s, however, these facilities erupted in riots, fire, and chaos (Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008; Reference MeranzeMeranze 1996). Some reformers suggested abandoning the whole project (Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008: 51; Reference RothmanRothman 1971: 93), while others searched for modifications that would enhance control and prevent future disruptions. In this atmosphere, the modern cellular prison emerged.

Technical Needs Drive Innovation and Early Adoption, 1810s–c. 1834

On Christmas Day, 1821, New York embarked on a bold experiment at its new upstate prison (Reference LewisLewis 1922: 81). Auburn State Prison's construction had been authorized in 1816 to supplement the Newgate proto-prison. Among other problems, Newgate suffered “serious insurrections in 1818, 1819, 1821, and 1822” (Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008: 44). Worried that the new Auburn facility would suffer similar upheavals, the New York legislature authorized a hybrid system at Auburn in 1819. Some of Auburn's prisoners would be housed in large rooms as in local jails and penitentiary houses. But officials worried that housing inmates together, enabling enthusiastic discussions of past misdeeds and other enticements, would induce their future criminality. Other inmates would remain in solitary confinement, sleeping and eating in cells approximately three feet wide, with no work, communication, or other distractions except a Bible.

The results were disastrous. The solitary cells were too narrow to allow inmates sufficient exercise, causing muscle atrophy and disease (Reference BarnesBarnes 1921: 53); insanity and suicide were also common. Auburn's Warden, Gershom Powers, reported, “one [inmate] was so desperate that he sprang from his cell, when the door was opened, and threw himself from the gallery upon the pavement…. Another beat and mangled his head against the walls of his cell until he destroyed one of his eyes” (cited in Reference LewisLewis 1922: 82). The surviving inmates received pardons.

Following this disaster, Auburn's administrators created a new system of confinement—one that would indelibly change the meaning of incarceration. Under the new system, inmates would still sleep in solitary cells at night, but during the day, they worked together in factories within the prison. Still concerned with potential mutual contamination, officials forbade inmates from looking at or speaking with each other. Inmates were ordered to walk in lockstep (to increase discipline and make conversation difficult) while misconduct was punished by whipping. This mode of confinement became known as the Silent System, the Congregate System, or the Auburn System. It was revolutionary: for the first time, the vast majority of a prison's inmates were confined in cells for a large portion of the day. The Auburn System became tremendously popular (Reference LewisLewis 1965; Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008).

In 1818 and 1821, before the Auburn disaster, the Pennsylvania legislature authorized the construction of two state prisons, Western State Penitentiary in Allegheny County (near Pittsburgh) and Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, respectively. Like New York, Pennsylvania needed more and stronger prisons to supplement Walnut Street, which was increasingly overcrowded and unruly—it experienced four large riots between 1817 and 1821 (Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008: 44). The new prisons were initially authorized to follow “the principle of solitary confinement” (Pennsylvania 1821) to prevent the chaos at Walnut Street. However, Western State Penitentiary's architecture quickly proved problematic: cells lacked sufficient ventilation to healthfully confine inmates for long periods of time and were too small to allow for exercise; soon, inmates were released from their cells for periods of fresh air (Barnes 1968: 140, 157; Reference DollDoll 1957). Meanwhile, the disaster at Auburn provided new anxieties about maintaining inmates in unmitigated solitary confinement. However, Pennsylvania reformers still believed that silence alone would not prevent cross contamination. They insisted on physically separating inmates from one another. The legislature compromised in 1829, authorizing “solitary or separate confinement at hard labor” in both Western and Eastern (Pennsylvania 1829).

Under this “Pennsylvania System,” inmates were housed separately in cells large enough to work, sleep, pray, read, and exercise alone, without leaving their cells, except to walk in a small yard attached to each cell. Inmates were not permitted to talk, except with official visitors (prison officials, penal reformers, legislators, and diplomats). A silent existence, with solitary labor and time for prayer, would enable reformation. Moreover, the System enabled inmates to reenter society unrecognized and unimpeded by stigma: inmates were known by numbers only and, during any egress from their cells, inmates were hooded to protect their identities even from guards. These ideas shaped the understanding of the Pennsylvania System for the next 40 years (e.g., Reference VauxVaux 1872). However, these ideas were showcased primarily at Eastern State Penitentiary, which opened in 1829, while Western continued to be plagued by architectural problems for a full decade before reconstruction allowed administrators to implement the Pennsylvania System.

New York and Pennsylvania's innovative modern prisons were direct responses to problems with their proto-prisons. Walnut Street and Newgate were the oldest proto-prisons in the country, in need of relief from overcrowding and architectural damage. Their deteriorating conditions, riots, and overcrowding created a pressing need for remodeling, more physical space, and greater control. Both New York (1816) and Pennsylvania (1818) responded by authorizing the construction of newer, bigger, and stronger facilities at Auburn State Prison and Western State Penitentiary, which were initially extended versions of the Walnut Street model. Other states faced similar strains in the 1810s and 1820s. These strains created a technical problem that drove early adoption of modern prisons following the Auburn or Pennsylvania plans.

By 1820, most Northern states and some Southern and frontier states had adopted a proto-prison. Their facilities had deteriorated by the 1820s, necessitating new prisons. Indeed, among states that had joined the Union by 1821 (roughly the end of the proto-prison movement), the presence of a proto-prison well predicts states’ early adoption of modern prisons: states that had adopted a proto-prison were early adopters of modern prisons, while states that had not adopted a proto-prison by 1820 waited to adopt a modern prison (Table 1). Even seemingly outlier states fit the pattern: When Louisiana authorized its modern prison in 1832, it sought to replace a decrepit jail holding the state's criminals. Indiana was a late adopter of its modern prison, but had not adopted a proto-prison until 1820.

Table 1. Proto-Prisons and Modern Prisons

The sample is limited to states in the Union by 1821 to improve comparability: the next state joined in 1836.

For early adopters, modern prisons represented a rational solution to a pressing problem. New York and Pennsylvania provided new models of incarceration that state legislatures quickly copied when their own proto-prisons deteriorated. (As discussed below, institutional pressures also encouraged these states’ actions.) However, by the mid-1830s, adoption was apparently a response less to aging proto-prisons than to a changing field in which the modern prison had become a taken-for-granted tool of crime control.

Legitimacy Drives Late Adoption, c. 1835–1860s

With the exception of Rhode Island, states authorizing prisons after 1834 were located exclusively in the frontier and Deep South. Alabama, Missouri, and Mississippi each adopted a modern prison in the early 1840s, followed later by Texas and Arkansas. Frontier states wasted no time: Michigan, Iowa, Wisconsin, California, and Minnesota each adopted a prison either before or within a few years of achieving statehood. (After becoming a state in 1820, Maine followed the more traditional path, adopting a proto-prison in 1823, which it converted to a modern prison in 1839.) These states were responding to a gravitational force few could withstand.

By the late 1830s, authorizing a state prison was a natural, even expected piece of statecraft.Footnote 4 Sixty percent of states in 1835 had adopted a modern state prison.Footnote 5 States without prisons looked comparatively backward or severe in their continued reliance on capital punishment, corporal punishment, or dingy, overcrowded jails. Southern states that had not yet adopted prisons were criticized for retaining corporal and capital punishment and their disproportionate number of executions of African Americans accused of (frequently) petty crimes (Reference BannerBanner 2002). While citizens were fairly unconcerned with this criticism, “Southern legislators, governors, and newspaper editors … were aware that the rest of the Anglo-American world increasingly looked upon their slave South as a throwback to a part of a common past best forgotten” (Reference AyersAyers 1984: 55). Prison historian David Oshinsky suggests that this criticism drove Mississippi's adoption of a modern prison in the 1830s. One Mississippi newspaper complained, “Truly, we are gaining an unenviable character abroad!” (cited in Reference OshinskyOshinsky 1997: 6). Louisiana's reliance on an overcrowded, deteriorating jail built in 1803 incurred public embarrassment when de Beaumont and de Tocqueville published their 1833 report on American prisons (Reference CarletonCarleton 1971: 8). It is perhaps not a coincidence that Ohio and Louisiana authorized new prisons shortly after those gentlemen condemned their older facilities:

We have deeply sighed when at Cincinnati, visiting the prison; we found half of the imprisoned charged with irons, and the rest plunged into an infected dungeon; and we are unable to describe the painful impression which we experienced, when, examining the prison of New Orleans, we found men together with hogs, in the midst of all odours and nuisances.

During their visit, Louisiana's governor emphasized his own commitment to penal reform (Reference de G. and de Tocquevillede Beaumont and de Tocqueville 1833: 13).

Prison adoption offered legitimacy to former territories seeking equivalent status with more established states and Southern states facing criticism for other practices.Footnote 6 Indeed, it was the social and political elites—preoccupied with Northern opinion—who drove most Southern reform efforts; the average middle-class Southerner was less concerned with penal reform. The prison symbolized the Enlightenment, civilization, and progress, equations frequently discussed in Southern debates over adoption. A Texas legislator claimed building a modern prison would “afford the most satisfactory demonstration to the world of our onward march in improvement and civilization” (cited in Reference PerkinsonPerkinson 2008: 74). Where this concern did not exist, prisons did not develop. In their long-time refusal to build a prison, South Carolina's political elites “define[d] themselves in conscious opposition to the values of ‘progress’” (Reference AyersAyers 1984: 58). In most Southern states, however, political elites welcomed modern prisons as proof “that the slave south was not the barbaric land its detractors claimed” (Reference AyersAyers 1984: 54).

Indeed, legitimacy concerns may have outweighed traditional crime concerns when building prisons. Southern proponents understood the prison's practical utility, repeating many of the same advantages that northerners discussed (Reference AyersAyers 1984: 42–45). In practice, however, the Southern criminal justice system was not as significantly revised as its Northern counterpart. Only white criminals were incarcerated, while African Americans were punished on plantations (or executed). Consequently, southern prisons remained substantially smaller than Northern prisons. While many states’ prisons quickly succumbed to overcrowding, some Southern and frontier prisons were little used until population and crime rates matched institutional capacity. Illinois was still a frontier state when it adopted its first prison in 1831. This new prison at Alton was barely used between 1831 and 1833; in April 1833, the prison contained only one inmate (Reference GreeneGreene 1977: 188). Texas's 225-cell structure was sufficient for the state's needs until the Civil War (Reference McKelveyMcKelvey 1977: 47). This limited reliance in practice, in both frontier and Southern states, suggests prisons played a symbolic role in which adoption was more salient than actual use.

Isomorphism on the Auburn System

It would be misleading to suggest that legitimacy concerns only affected late adopters. Instead, legitimacy also shaped states’ decisions about prison design. Powerful institutional pressures stemming from uncertainty and penal reformers’ debates, combined with contingent factors, encouraged states to adopt the Auburn System. Indeed, the ultimate homogeneity in prison design masks the fact that most states seriously considered both the Auburn System and the Pennsylvania System and their respective benefits and risks.

To the modern observer, the differences between these two models may appear miniscule. Both entailed the long-term punishment of convicted criminals, hard labor, silence, and solitary confinement. Yet, the differences were crucial for contemporaries. Some reformers saw Auburn's factory-like discipline as the best way to subdue prisoners’ spirits and make them fear crime's consequences. Others argued that solitary confinement would accomplish these ends and enable reformation: solitary encouraged personal reflection and boredom, which would make prisoners want to work, rather than working for fear of whipping.Footnote 7

Contemporaries scrutinized these differences because the stakes were high. Implementing the wrong model might mean the death and insanity of inmates, as occurred during Auburn's early experiments, at a time when citizens strongly opposed cruelty and suffering (Reference DavisDavis 1957). More drastically, choosing an ineffective model, whether one that fails to deter or reform, could imperil the fragile Republic, which required virtuous citizens (criminals were not virtuous). As the fate of the Republic was still uncertain, some middle-class citizens feared (perceived) increases in urban crime, associated with the degenerating proto-prisons, foreboded the Republic's demise (Reference MeranzeMeranze 1996). With so much riding on the new prisons, a state's choice of prison model was vitally important. It was also shrouded in uncertainty.

Mimetic Pressures

Uncertainty permeated the young carceral field. First, there was widespread technological uncertainty. Incarceration as punishment was still a novel concept. Prison was an untested, poorly understood technology. Penal reformers, prison administrators, and politicians frequently referred to prison practice as an “experiment,” expressing the level of unpredictability. In heated philosophical debates over the Auburn and Pennsylvania System, penal actors had little evidence to rely on, turning to logical arguments in the absence of meaningful experience. One Pennsylvania prison administrator described the anxieties of the late 1820s and early 1830s:

The experiment of separate confinement by day and night was about to be made. Good men had doubts. None of us could say how far the mind and body could be in total seclusion from society and confinement to a cell for a length of time…. (Pennsylvania, 1835, Bradford testimony)

With few working models available, both recently established, there was widespread uncertainty over best practices.

Second, penal actors faced goal ambiguity. Reformers outlined multiple, conflicting purposes of punishment. Many commentators emphasized inmate reformation (changing the inmate's character through education, training, or spiritual reflection to make crime unnecessary or undesirable) and deterrence (dissuading would-be offenders from committing crime by imposing or displaying punishment for wrongdoing). Another theme cautioned against punishments that further induce criminality. While penal actors eschewed vengeance as an inappropriate goal of punishment, they acknowledged the propriety of punishing criminals and emphasized the need for proportionality (provided by prison sentences’ infinitely customizable length). More generally, punishment should ensure public safety but in cost-effective and humane ways. These standard goals (reformation, deterrence, proportionality, cost-effectiveness, humane treatment), however, are somewhat ambiguous and mutually exclusive.

Without a clear hierarchy, individuals disagreed over the prison's purpose. In one year, Eastern State Penitentiary's administrators offered different views of reformation's importance. The prison's Board of Inspectors noted, “While reformation is not the sole or even main object of punishment, it is, nevertheless, a most desirable effect of it” (Annual Report 1850: 5). However, the prison physician believed he lived “in an age which declares the reformation of the convict to be the chief motive for his incarceration, and [worked] under a system of discipline which professes to accomplish this desirable result more effectually than any other…” (Annual Report 1850: 28). Some penal actors did not believe such goals were possible. Auburn State Prison's Warden Elam Lynds proclaimed his disbelief in the possibility of inmates’ “complete reform, except with young delinquents.” He explained, “Nothing, in my opinion, is rarer than to see a convict of mature age become a religious and virtuous man. I do not put great faith in the sanctity of those who leave the prison; I do not believe that the counsels of the chaplain, or the meditations of the prisoner, make a good Christian of him” (Reference de G. and de Tocquevillede Beaumont and de Tocqueville 1833: 202). These goal ambiguities exacerbated technological uncertainty: if the reason for the technology is unclear, selecting the best technology must rely on other factors.

Third, penal actors may have experienced a kind of epistemic uncertainty as they questioned the reliability of statements disseminated as truth. During the debate over prison models, penal reformers and prison administrators from warring camps expressed skepticism toward each other's statements. In 1835, the pro-Auburn Boston Prison Discipline Society (BPDS) wrote,

It has often been said, and generally believed, that all communication between the convicts is rendered physically impossible, in this [Pennsylvania] Prison, by the construction. If persons investigating this subject for the public benefit, would be a little more thorough in their investigations, they would find that this is not true. (BPDS, 1835: 883)

Both sides claimed their opponents doctored their statistics or otherwise hid the truth. One BPDS member and former Auburn supporter, Samuel Gridley Howe, experienced his own crisis of confidence, explaining,

The spirit of our Reports was so partial, the praises of the Auburn system were so warm, and the censure of the Pennsylvania prisons was so severe, that one could not help suspecting the existence of violent party feeling…. A personal inspection of the principal prisons in the United States, and reflection upon the subject, afterwards convinced me that very little reliance could be placed upon those Reports, either for facts or doctrines. (BPDS, 1846: iii)

With statements like these circulating, interested parties likely questioned the reliability of “facts” and were more inclined to defer to common sense and any unambiguously concrete data (like inmates' insanity during solitary confinement at Auburn).

In light of these several layers of uncertainty and ambiguity, we should expect penal actors to have resorted to mimicry—essentially copying existing models, especially apparently successful models. Adopting established models resolves anxieties about how to proceed in ambiguous situations, while deflecting blame from decision makers if the model does not perform well. By contrast, adopting a unique model renders decision makers vulnerable if it later fails.

Indeed, once the Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems were established, penal actors in other states copied these models instead of inventing their own. As Illinois poised to adopt its first state prison, Lieutenant Governor William Kinney visited established prisons on the east coast before adopting the Auburn System (Reference GreeneGreene 1977: 187). Before adopting the Auburn System, Alabama's prison commissioners visited Tennessee's Auburn-style prison, which served as their model (Reference Ward and RogersWard and Rogers 2003: 48). Likewise, Texas sent its prison commissioners to Mississippi's Auburn-style prison, “The Walls,” before borrowing that prison's design and even its name (Reference McKelveyMcKelvey 1977: 47). Although Louisiana's prison commissioners were “not bound to adhere to the plan of the penitentiary-house at Wethersfield…” (Louisiana 1833: 106), their new prison was modeled specifically on Connecticut's exemplar of the Auburn System. Small variations existed across states, but every state prison outside of Pennsylvania officially followed the Auburn System by the Civil War.

Importantly, states officially adopted these models; in practice, prison officials departed from the model and legislatively mandated rules. The rule of silence was frequently violated in Auburn-style prisons, while administrators at several Pennsylvania-style prisons violated the dictate of total separation. From the neo-institutional perspective, this behind-the-scenes rule bending is entirely expected. Organizations must loosely couple formal structures, like the Auburn System or Pennsylvania System, to actual practice to achieve rational ends like organizational efficiency and cost-effectiveness, ends which are not always achieved by structures adopted for legitimizing purposes.

Normative Pressures

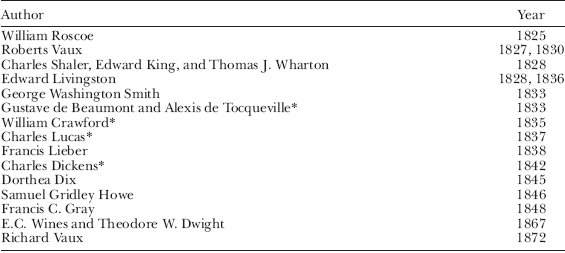

Despite this uncertainty, states did not automatically adopt either system: they were influenced by penal reformers championing these different models. Even before the Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems were implemented, let alone fully operational, a great debate arose between competing groups of penal reformers over the question of “prison discipline,” or how prisons should be operated. The debate took place primarily in published documents: penal reform societies’ widely circulated annual reports, single-authored pamphlets, small treatises, travel diaries, and letters to and from other penal reformers on both sides of the Atlantic. The debate peaked in the 1830s and 1840s, subsided in the 1850s, and ended by the 1860s (see Table 2). This debate stimulated the prison's rapid, widespread, and homogenous diffusion.

Table 2. The Debate Over Prison Discipline

These represent widely published letters, pamphlets, and reports on “prison discipline” published by individual penal reformers. I exclude the hundreds of other articles published in newspapers and other periodicals. For example, penal reform societies' annual reports and their privately funded journals (e.g., the Pennsylvania Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy) offered another forum for discussion. Both kinds of publications were also discussed in North American Review, a popular review. As the publication dates illustrate, the debate was most intense in the 1830s and 1840s. Note: Starred authors were British or European.

The lines in the Auburn-Pennsylvania debate were clear. The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons (PSAMPP, f. 1787), which championed the Pennsylvania System, competed with the Boston Prison Discipline Society (BPDS, f. 1825) and (later) the New York Prison Association (NYPA, f. 1844), which supported the Auburn System. As Barnes (1968: 177) explains, “Both [sides] were fiercely partisan and both were disgracefully unscrupulous in their use of statistics designed to support their cause or damage their opponents.”

Most influentially, Auburn's supporters crafted explanations about moral and practical problems with the Pennsylvania System. First, it was too expensive and unprofitable. Building sufficiently large cells for each inmate was prohibitively expensive, while traditional craft-style labor could not repay this expenditure. By contrast, Auburn's factory-style labor was more efficient and produced higher-demand goods. Second, the Pennsylvania System's reliance on “solitary confinement” was dangerous to inmates’ mental and physical health, which seemed especially plausible after Auburn's (1821–1823) fatal experiment with total solitary confinement. Third, the Pennsylvania System was cruel and inhumane: humans are social creatures and preventing human contact for years was akin to torture. Finally, the Pennsylvania System was impractical and ineffective: too many problems would plague its implementation while the hardest criminals would be unaffected by their conscience and not repent. For all these reasons, they argued, the Pennsylvania System was vastly inferior to the Auburn System.

The Boston and New York societies propagated these critiques in their annual reports and independent writings. In one annual report, the BPDS cautioned:

we have not known, from the nature of man, how he could be confined day and night in solitude, for a short term of years, to so narrow a space, and have his cell made his work-shop, his bed-room, his dining-hall, his water-closet, his chapel, &c., without getting the air and himself into a condition unfavorable to health. (BPDS, 1835: 884)

The Society usually paired such statements with statistics comparing Eastern to the Auburn, Charlestown (Massachusetts), and Wethersfield (Connecticut) prisons. In an 1839 report, for example, the Society complained:

The Tenth Report on the Eastern Penitentiary, by the inspectors, warden, and physician, is in excuses and opinions very fair, but in facts, AWFUL!—402 prisoners, 26 deaths; 23 recommitments, 18 cases of mania, &c., and expenses above earnings, untold by the government of the Prison, but disclosed by the treasurer of the commonwealth, to be the amount of $34,38 in a single year. (BPDS, 1839: 353)

Although the debate centered in the Northeast, the societies' arguments reached other regions. In 1829, the BPDS reported it had

printed about sixteen thousand copies, or 1,600,000 pages of the Annual Reports of the Society, and furnished them, at a moderate price, to the Legislatures of Maine, Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey…and gratuitously to the Legislators of some other States, and to benevolent individuals and Societies in America and Europe. (BPDS, 1830: 303)

Reform societies' annual reports and other writings were frequently republished or summarized by reviews, newspapers, and other periodicals. As a writer for the popular North American Review explained, “the cause of truth and justice and humanity, as well as of policy, is deeply concerned in having both sides of the question illustrated by all the light that their advocates can throw upon them” (Reference Meyer and RowanNAR 1977: 501). When legislators, governors, and prison commissioners considered adopting a prison, they were cognizant of the arguments supporting each model.

Reformers’ critiques of the Pennsylvania System worked much like the “rational myths” (Reference Edelman and SuchmanEdelman et al. 1999; Reference Meyer and RowanMeyer and Rowan 1977) that often propel isomorphic diffusion. These critiques explained the pragmatic purposes behind adopting or relying on a particular structure and helped institutionalize that structure. They incentivized states and prisons to adopt the Auburn System (and provided cover, should anything go wrong at their prisons), while creating substantial problems of legitimacy for those few that adopted the Pennsylvania System. Like rational myths, these statements became taken for granted, even while Philadelphia reformers and others continuously contested them.

States adopting the Auburn System frequently mentioned at least one of its relative merits, while states abandoning the Pennsylvania System repeated the standard critiques. By their fourth year of operations, the Rhode Island prison's Board of Inspectors called for an investigation, noting widespread insanity among the inmates; after adopting the Auburn System, the warden wrote a report condemning the Pennsylvania System (Reference Wines and DwightWines and Dwight 1867: 54–55). In New Jersey in the 1840s, the prison's physician and other administrators criticized the effects of the Pennsylvania System on inmate well-being (Reference Wines and DwightWines and Dwight 1867: 52). They later complained about their failure to profit and expressed a disbelief in the Pennsylvania System's reformatory power (Reference Wines and DwightWines and Dwight 1867: 53–54; see also Barnes 54; see also Barnes 1968: 173). In the 1860s, Western's prison administrators began criticizing the Pennsylvania System as impracticable—difficulties of implementation had long superseded faithful application—and ineffective at reforming inmates. They also hinted that separate confinement was cruel. These problems, and administrators’ belief in the Auburn System's benefits, grounded their request to abandon the Pennsylvania System (Barnes 1968: 307–09). The widely believed critiques of the Pennsylvania System solidified Auburn's victory.

Contingent Factors

Despite widespread uncertainty and reformers’ normative pressures, Auburn's victory was not preordained. The Auburn System's desirability was bolstered by four factors. First, Auburn supporters were better organized. The BPDS had more connections “throughout the country” than PSAMPP (Barnes 1968: 177), including other states’ prison administrators among their “corresponding members.”Footnote 8 Strong networks would have helped the BPDS propagate their claims about Auburn's superiority across the country.

Second, the Auburn System appeared to have a greater potential for profit, strengthening its supporters’ claims that it was profitable. Auburn's reliance on factory-style labor over workshop-style labor implied more efficient (and cost-effective) production. Additionally, inmates’ cells could be much smaller and, consequently, were cheaper to construct. By contrast, under the Pennsylvania System, inmates needed large cells, with sufficient workspace (and external yards), to preserve their health. Auburn's cheaper architecture and seemingly more efficient labor were particularly attractive for states struggling to tax their citizens. This economic explanation has received much of the credit for Auburn's success, despite states’ repeated failure to actually profit from these prisons (Ayers 1984: 67; Barnes 1968: 177; Reference McLennanMcLennan 2008: 8, 63–64; Reference RothmanRothman 1971: 88). Importantly for our purposes, many continued to believe Auburn was profitable.

Third, Auburn's failed experiment with solitary confinement left an indelible impression on penal reformers and citizens. BPDS members and other Auburn supporters capitalized on Auburn's early disaster, claiming that the Pennsylvania System would likewise produce disease, insanity, and death. Pennsylvania supporters sought to distinguish their “separate confinement” from total solitary confinement, emphasizing the role of approved visitors and labor (e.g., Eastern, Annual Report 1846: 7), but for many observers, it resembled Auburn's first plan too closely.

Fourth, the Pennsylvania System began slowly. Western's architectural problems prevented a working model of the Pennsylvania System until 1829. By that time, the Auburn System had two functional models in New York alone (Auburn and Sing Sing), plus models in Kentucky, Connecticut, DC, Virginia, Maryland, and Massachusetts. This popularity provided states ample prisons to visit and model new prisons after. Additionally, any observer using popularity as a proxy for success would have rightly deemed Auburn the more successful model, reinforcing Auburn supporters' claims of superiority.

Discussion

Summary

This article has offered a neo-institutional account of antebellum prison diffusion, emphasizing the role of legitimacy and institutional pressures. The prison's innovation and early adoption was driven by the need to replace deteriorating proto-prisons. Once prison became the modal punishment, prison adoption provided much-needed legitimacy in the frontier and South while states without a prison became vulnerable to criticism. Two institutional pressures, reinforced by contingent factors, shaped these prisons' structure. First, intense uncertainty about the new technology of the prison; ambiguous, sometimes conflicting, goals of punishment; and a general epistemic anxiety made mimicry an attractive option. Second, the intense debate over prison's appropriate form, centering around penal reformers' claims about the Pennsylvania System's flaws and the Auburn System's concomitant advantages, exerted normative pressures on states to adopt New York's less criticized mode of confinement. In this setting, the Auburn System represented the advised choice, while the Pennsylvania System posed liabilities. Finally, contingent factors, including Auburn supporters' better organization and the Pennsylvania System's late start, reinforced these mimetic and normative pressures.

Extant theories of the prison's emergence cannot account for the way in which prisons diffused rapidly, widely, and homogeneously. Unlike those explanations, this framework prioritizes field-wide dynamics over states' unique social, economic, or political characteristics. Under this framework, we can understand why slave states and free states; large, urbanized states and smaller, rural states; industrial and agricultural states; established coastal and new frontier states alike simultaneously adopted fairly identical prisons. These state-level differences may explain states' differential reliance on the prison, but they had little impact on states' willingness to build a prison or what it looked like.

Theoretical Contribution

Examining an innovation's diffusion by interrogating the process that leads to field-wide dominance has revealed two fundamental features that neo-institutional analyses rarely examine: contingency and agency. Neither the prison's dominance, nor its form, was a foregone conclusion; rather, these resulted from institutional pressures, fierce debate, and historical accidents. We often forget about models that did not diffuse, the competitors to the versions of technologies or practices that did succeed (Reference Strang and SouleStrang and Soule 1998: 285). Without examining such failures, we cannot identify the factors that lead to one model's success over another. While traditional institutional pressures (rational myths, uncertainty) were present, contingency was critical. Had New York's failed experiment relied on public labor instead of solitary confinement, or had Pennsylvanian reformers weakened the association between fatal solitary confinement and the Pennsylvania System, more prisons may have followed Pennsylvania's lead. Had Western not suffered architectural problems from the outset, it would have provided states with a working example of the Pennsylvania System ready for copying.

This study has also revealed the importance of actors, which is somewhat obscured by neo-institutionalists' focus on organizational environments (but see, e.g., Reference Hallett and VentrescaHallett and Ventresca 2006). Neo-institutionalists tend to examine disembodied change rather than “the contested construction of…models” (Reference ScottScott 2001: 118). As Reference DiMaggio and ZuckerDiMaggio (1988: 10) explains, scholars infrequently ask, “Who has institutionalized the myths (and why)?” and “Who has the power to ‘legitimate’ a structural element?” Indeed, these questions are particularly consequential because organizational structures are, as Gouldner explained, “the outcome of a contest between those who want it and those who do not” (Reference GouldnerGouldner 1954: 237, cited in Reference DiMaggio and ZuckerDiMaggio 1988: 12). More recently, scholars have demonstrated how personnel professionals, not legislators or judges, invented and disseminated equal opportunity compliance techniques, encouraging employers to adopt such strategies by exaggerating the legal threat of noncompliance (Reference DobbinDobbin 2009; Reference Edelman, Abraham and ErlangerEdelman, Abraham, and Erlanger 1992). Reference DiMaggio, Powell and DiMaggioDiMaggio (1991) himself has explored the contestation between groups with different views on how art museums should function. But there has been little theoretical work on the conflict that precedes a structure's dominance.Footnote 9

In the case of antebellum prisons, penal reformers, prison administrators, and other observers played a significant role in constructing what a legitimate prison should look like. The Auburn–Pennsylvania debate in particular provided a forum for reformers to peddle their preferred method in ways that offered prospective adopters—governors, legislators, prison commissioners, and even prison administrators—high-stakes incentives for avoiding the Pennsylvania System. By repeatedly condemning the Pennsylvania System (and prisons following that model), reformers created and reinforced beliefs about that system's flaws, normalizing the decision to adopt the Auburn System. Combined with apparent lessons from history (Auburn's fatal experiment with solitary) and the Auburn System's growing numerical dominance, these myths made Auburn the practical, moral, and expected choice.

More than shaping the new prisons, however, this debate may have sped the prison's diffusion. Scholars have previously noted that “theorization,” creating abstract accounts about the technologies or practices' outcomes, not only aids but speeds these forms' diffusion (Reference Strang and MeyerStrang and Meyer 1993). Others have shown that once a form is institutionalized, or taken for granted, adoption becomes more rapid (Reference Tolbert and ZuckerTolbert and Zucker 1983). Likewise, conflict over the appropriate model of prison may have sped the prison's diffusion. Penal reformers' competitive proselytizing certainly helped disseminate information about the models, but they also elevated the prison's public profile. The debate centered on models; it presupposed the prison. Indeed, few reformers opposed the idea of prison altogether. Rather than slowing diffusion, conflict over models may have provided a faster medium for the prison's diffusion.

Future Research

While this study has focused on a historical case study, it offers several lessons for sociolegal scholars interested in large-scale change in any period. These lessons will be particularly valuable when examining the innovations that contributed to mass incarceration and other aspects of the punitive turn.

This article has emphasized the distinction between the prison's emergence or innovation and its diffusion or spread across the country. This distinction is fundamental for sociolegal analyses more generally because the factors that first spark innovation may significantly differ from the reasons an innovation diffuses. Even when practices or technologies offer the same technical or rational purpose, different jurisdictions may turn to these practices for other reasons, including external legitimacy. Sociolegal scholars should investigate the variation in reasons for adoption.

Examining diffusion highlights the contingency stemming from multiple available models. It encourages examining competition among models and the process by which one model dominates others. Many traditional accounts of penal changes are incomplete. They ground change in political, economic, social, or cultural factors, which shift public opinion about crime, criminals, and punishment. However, even when prevailing views are consistently punitive, such views could authorize a wide variety of practices; yet, history offers multifarious examples of homogenous rather than heterogeneous responses. While it is necessary to understand why these technologies are attractive to policy makers or constituents, we must also examine the mechanisms that lead states to adopt such similar technologies.

Indeed, as Reference SuttonSutton (1996) has argued, neo-institutional theory links macro-level factors, a major focus in studies of penality, to the adoption of specific techniques or practices. This article has emphasized the role of legitimacy, uncertainty, and reformers' normative debates in the nineteenth century. Understanding the role of uncertainty today may help explain why states simply copy innovations from other states instead of inventing their own technologies. Uncertainty is particularly likely in the penal context because penal goals are ambiguous and conflicting, while the difficulties surrounding experimental evaluation render the technologies untestable (Reference SuttonSutton 1996).

Reformers may play a smaller role in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, but rational myths offer another useful concept for sociolegal scholars. Many penal technologies are supported by taken-for-granted justifications that are unsustained by the data. The “broken windows” theory (Reference Kelling and WilsonKelling and Wilson 1982) bolstered order-based policing in the 1980s and 1990s. Despite a tenuous connection between the actual study and the policies it sustained (Reference Sampson and RaudenbushSampson and Raudenbush 1999), the idea of broken windows provided a common-sense explanation for (what became) popular policies. The assumption that the death penalty deters, despite ambiguous and conflicting data (Reference Donahue and WolfersDonahue and Wolfers 2006), offers another rational myth. Rational myths are also powerful forces behind practices' abandonment. Robert Martinson's oft-cited and misunderstood article evaluating rehabilitative programs (Reference MartinsonMartinson 1974) has been used to suggest “nothing works” and consequently in-prison rehabilitation should cease (see, e.g., Reference AllenAllen 1981). Researchers should examine how these and other myths are generated, who distributes them, and the process by which myths acquire fact-like status (see Reference BerginBergin 2011).

While coercive pressures were rare in the nineteenth century, these pressures, particularly from the federal government, may play a greater role in the contemporary context. Reference SimonSimon (2007) demonstrates how federal funding for schools that adopt exclusionary punitive practices (Safe Schools Act) or prison building in states that adopt mandatory-minimum sentencing laws (Violent Crime Control Act) significantly encouraged these practices' adoption. Similarly, federal courts' influence over penal practices nationwide increased during the second half of the twentieth century (Reference Feeley and RubinFeeley and Rubin 2000).

Examining the role of institutional pressures illustrates the underlying mechanisms driving both civil and criminal law changes. Civil and criminal law studies appear fundamentally different: the former primarily examine companies, nonprofit organizations, lawyers, personnel professionals, and settings (e.g., workplaces) familiar to everyday people; the latter primarily examine state-run organizations, policy changes, public opinion, and mostly unfamiliar settings (e.g., courts, prisons). However, major legal changes in both sectors are driven by similar forces. To rephrase Reference Grattet, Jenness and CurryGrattet, Jenness, and Curry (1998: 304), identifying similar processes underlying change makes criminal law studies “more relevant for the general socio[legal] community.”