A CRIMINAL HISTORY

Edinburgh is a historic city, and few institutions are prouder of their part in the capital's history than the University of Edinburgh. The School of Law boasts a prime location in the University's Old College campus, the dome of which is a landmark feature of Edinburgh's skyline.

The site where Old College now sits was once called the Kirk O’ The Fields and mainly consisted of religious dwellings and a hospital. It was also the location of lodgings of Lord Darnley, Mary Queen of Scots’ second husband, on the night of his murder.Footnote 1 He amassed many enemies and some of them conspired to place barrels of gunpowder under his room causing the lodging house to explode one February night in 1567. However Darnley's body was found, strangled, some miles away in an orchard the next morning. His murder remains a mystery to this day.

The University of Edinburgh took over this site in 1583Footnote 2 and added facilities and buildings as the needs of the university grew. Interestingly the library collection was established three years prior to this as the result of a bequest from Clement Littil, a lawyer who donated 276 volumes to found the university library.Footnote 3 In 1617 the Duke of Chatelherault built a mansion on this site which later became the library building - some decorative stones from this were retained from the demolition in 1798 and have since been incorporated into the vestibule entrance to the Law Library; one was also built into the exterior of Sir Walter Scott's house at Abbotsford.Footnote 4

Old College as it stands was designed and built by architects Robert Adam and William Playfair. The University desired a purpose-built campus to encompass its teaching, and Robert Adam won the competition with his plan which featured a two-part quad and a bell tower. The foundation stone was laid in 1789 but numerous delays meant that building was incomplete when Adam died in 1792.Footnote 5 Playfair took over but the build took a further 95 years to completeFootnote 6, with the final touch being the completion of the dome at the South Bridge entrance in 1887 which was financed by a bequest from Robert Cox, a lawyer from the Gorgie area of Edinburgh.Footnote 7

Figure 1: Edinburgh University Old College.

From: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edinburgh_University_Old_College_05.jpg Attribution: Stinglehammer, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

While the renovations were ongoing, Edinburgh's most notorious murderers were operating just a few streets from the new campus buildings. Burke and Hare were ‘resurrectionists’, grave robbers who would dig up bodies to sell to the medical school for profit. The ‘Act for Better Preventing the Horrid Crime of Murder’ – the so-called Murder Act of 1752 - stated that bodies for anatomical dissection were meant to be those of convicted and executed murderers only.Footnote 8 However in 1828 there was a shortage of available convicted murderers and increasing demand from medical schools, particularly the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh. Burke and Hare took it upon themselves to create a supply to meet the demand. They murdered at least sixteen people, usually by getting them drunk and then suffocating them by kneeling on their chest - a technique which became known as ‘Burking’. The bodies were sold to Robert Knox's anatomy school, leading to the charming children's rhyme:

When they were caught Hare turned King's evidence and gave up the names of his co-conspirators to escape the gallows. Burke was sentenced to death and hanged at Lawnmarket on 28th January 1829. His sentence also demanded that his body was to be dissected in the same way his victims had been; however, there was rioting in the streets following his execution and so his body was brought to Old College using the network of underground passages in the Old Town. He was brought in using a corridor and stairs in what now forms part of the Law Library's lower ground floor.Footnote 10 His skeleton and death mask are still held in the Anatomy Museum at the University; the Centre for Research Collections holds a note said to have been written in his blood following his dissection.

Figure 2: The skeleton of William Burke.

From: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_skeleton_of_William_Burke_(geograph_2621217).jpg Attribution: Kim Traynor / The skeleton of William Burke.

Another link between Burke, Hare and Knox and the University's estate comes in the form of the second architect to work on the creation of the Old College campus – William Playfair. Not only did he oversee completion of Adam's design in the 19th century, but he also won a commission from the Royal College of Surgeons (headed by Robert Knox) to design their Edinburgh building.Footnote 11 The Playfair Building remains an opulent legacy of his work and is now used as an events venue, just as the Playfair Library in Old College is today. The University's library collection was originally housed in the extravagant hall named in honour of Playfair from 1820s until the 1960s. Eventually, however, the main collection was moved from the Old College campus to George Square along with the migration of all departments except for the School of Law.Footnote 12 The Playfair Library remains a jewel in the university's estate and is used for events, receptions and lectures.

REIMAGINING THE PAST

In 2014 on the 225th anniversary of the laying of the Foundation Stone, the school began the largest and most challenging renovation in the University's history. The school buildings and Law Library were entirely refurbished in a project which took took 8 years from first meeting to final completion, and cost the school £35million.Footnote 13 Although not quite as long as Adam and Playfair's original project, this ambitious reimagining of the building still caused a great deal of upheaval for the staff of the school and library whose services remained operational throughout.

Planning for the Law Library to move out and back in to the building took place in 2013 and 2014, and this included an extensive weeding and deduplication exercise as the library would return with approximately 40% less shelving capacity. In some ways this was beneficial as it meant less stock to move in 2016 when the collection was temporarily housed in 40 George Square (formerly the David Hume Tower).Footnote 14 Lectures and seminars took place in the same building so although the surroundings were much less picturesque, the library was able to function much as it always had.

As any library staff who have been involved in moving an entire collection will be aware, there were difficulties at both ends of the process. Continuity was a real problem as large institutions often have high staff turnover, with people involved in very specific tasks moving to different positions or leaving the organisation between the planning and implementation stages. An operation of this magnitude required many moving parts and excellent communication in order to be completed in the most efficient way, and when decisions were not punctual or followed up difficulties arose in even the most basic areas such as available shelving and technology access points.

When the two year relocation came to an end the library staff moved the collection back over a condensed period of eleven days in January 2019. This time frame was chosen in order to minimise disruption to users and allowed the full library to be accessible for the start of teaching in Semester Two. This was no mean feat!

Figure 3: The Senate Room, University of Edinburgh Law Library.

Image location: https://www.law.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large_image/public/2019-04/Card%20images%20alumni%20support%20you.jpg?itok=NuH38eOf. From: https://www.law.ed.ac.uk/about-us/facilities-and-resources.

The new library operates over three levels. There is less shelving, fewer study spaces, and an unconventional but distinctive shelving layout, but where some compromises had to be made there are original features which were maintained and enhanced. For example, the Senate Room was the original Senate Room for the university; the architects replicated original details as far as possible right down to the colour of the walls. The height of the ceilings allow for the housing of huge collections of law reports in stacks ten shelves high, and make for an atmospheric study environment. The Oval Room which is dedicated to Scots law material echoes the architect's original plans for the building and looks out onto the quad. The Gordon Duncan room on the lower floor contains a collection of older Scots law material and is named after a former Professor of Private Law at the School who left a bequest in his will. The William Burke corridor and stairs feature in the farthest room of the library; a glass floor preserves this original feature and an information plaque will soon be mounted alongside.

Figure 4: The Oval Room, University of Edinburgh Law Library.

Image location: https://www.law.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/large_image/public/2019-04/Masters-Online.jpg?itok=xlBsspKb. From https://www.law.ed.ac.uk/about-us/facilities-and-resources.

There are many favourable features in the new library. Oak panelling and shelving features heavily throughout, just as it does through the rest of the school, and this implies warmth, quality and a solid foundation which is what students would expect from their time with the School of Law at Edinburgh. It also speaks to the respect that the School has for the importance of the library, the collection and the staff. They have always worked closely with the Helpdesk and Academic Support Librarian teams, and this bond has only strengthened in recent years. The unusual octagonal shape of the shelving in the library floors replicates the layout of the Usha Kasera lecture theatre located directly above it (formerly the Adam lecture theatre and the site of Burke's dissection)Footnote 15, which suggests the impact of teaching resonates through library floors just as the knowledge contained in the stacks may echo upwards.

Although the refurbished space required the librarians to reduce holdings by some margin, this has now left the library with a curated collection. Retention policies which were formally in place in line with the wider network of University Libraries had to be examined, and informal policies requested by the school required renegotiation. For example, previously the library retained one copy of previous editions for non-Scots Law titles and two copies of previous editions for Scots Law titles. However, in light of the reduced shelving capacity, staff must now assess on a case-by-case basis using usage statistics and the position of the publication on course reading lists.

Unfortunately, each of these advantages can also cause difficulties for the staff. The iconic setting of the library means that it is a favourite spot in which to study for students of all disciplines, much to the disquiet of some in the School of Law. As one of eleven libraries across the University estate, students from all subjects are welcome to use the building. With limited seating some law students find that there is not always room for them on busy days and this can create an ‘us and them’ mentality which leads to complaints to the Helpdesk staff. While the School and University want their students to feel a belonging and ownership of their environment, vying for space causes consternation. Helpdesk staff have developed procedures in order to monitor and troubleshoot study space issues, but the situation remains challenging at peak times.

A universal problem for libraries located in historic buildings is the lack of expansion space for stock, and when library staff were informed that the return to the refurbished building would require the collection be reduced by more than one third, hopes for future expansion were not optimistic. Despite the university operating an e-preference policy since 2005, Law (and particularly Scots Law) is an area which relies more heavily on print resources than almost any other academic discipline and so requires a steady hand to balance the need with the space. The Parliament House Book alone has grown to an unwieldy eight volumes in recent years and although it is available via subscription services, many smaller publishers cannot afford, or seem unwilling to, release their material in electronic copy.

The renovations were designed to create ‘state-of-the-art facilities fit for a 21st century, world-class law school,’Footnote 16 and while the design of the library has somewhat limited the potential for the growth of the print collection, the architects have managed to encompass a strong sense of history while still creating an iconic and popular working library space.

A TROUBLED FUTURE

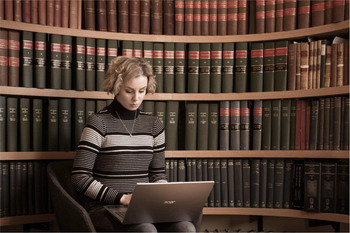

After the teething troubles of returning to Old College in early 2019, and staff changes which brought two new academic support librarians to the team early in the academic year, 2020 looked to be a fresh start for the law library. Unfortunately, the Coronavirus pandemic hit the UK in March and almost immediately all in-person activities on campus shut down. Library buildings were closed, staff worked from home, course organisers rushed to record lectures and find out if their course readings would be available in time for assignment deadlines and exams. While the country went into lockdown, yet due to external accreditation criteria, law students were still required to sit exams. Library staff founded themselves communicating with stressed staff and struggling students over the fact that the library could and would operate online.

Teams across the service were troubleshooting licensing problems as they arose, additional staff were seconded to the Acquisitions team and policies and procedures had to be developed and tested almost overnight as the situation developed. Print collections were inaccessible and although all subject areas were affected, law found more difficulties in locating readings than other subjects. A new designation for resources was created – key text – and although the definition of what was ‘core’ or ‘key’ developed over time, the main criteria was that the course could not run without it.

Figure 5: Edinburgh Everywhere. University of Edinburgh Library Services, updated May 2021.

In the period March to June 2020 73 requests for ebook access were made by academic staff. That number grew to over 100 by the end of 2021. Many of those were able to be supplied through usual purchasing methods, and some publishers reacted to the pivot to online learning quickly by allowing access to their online catalogues for free for a limited period. However, others reacted to the spike in demand by increasing prices for popular items. Academic librarians across the country noticed this and a campaign for fairer pricing began to create some publicity for the issue;Footnote 17 although there have been few measurable changes to the practice of publishers since the campaign began, it has provided a useful starting point for conversations with academics who would enquire as to why books are not available electronically.

Figure 6: Screenshot of Law Librarian Blog Post ‘The Problem with Ebooks’, February 2021. https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/lawlibrarian/2021/02/17/the-problem-with-ebooks/.

Some third party sites seemed to offer a solution to this problem. Companies such as Kortext operate by renting a book to an academic institution, charging the equivalent of the price of a print copy per student per year to access an electronic version of a text. For example, a print copy of a book for a course may cost £50. For a cohort of 300 students the University would be charged £15,000 per year – though some discounts may be applied. Books only available through these methods were named ‘etextbooks’ to differentiate those with annual renewal costs from those purchased from usual suppliers.

This was a huge departure from the traditional model of academic ebook sales, which might offer a university the option to purchase their book for a one-off fee according to how many people would need access to the book at any one time (e.g. 1-User, 3-User, Unlimited Access). Usually these prices would be higher than a single print copy but would then be accessible in perpetuity. An alternative access model would be that an institution may purchase single-use credits on the basis that when the credits had been used up another batch of credits would need to be purchased to ensure continued access.

In the summer of 2020 the Library secured additional University funding for etextbooks from publishers including Kortext where this was the only viable solution for key texts required for teaching. Of the additional budget allocation for etextbooks across the whole of library services, law resources constituted two fifths of the total. Law is only one of the thirty Schools which make up the University of Edinburgh so this shows not only how disproportionately Law have been affected by the pivot to online teaching but also reflects the difficult position caused by the reluctance of publishers of legal materials to make their monographs available electronically.

Of course, staff were keen to ensure that the requirements of law students ensconced in study and research from home were met in any way they could. By January 2021 risk assessments had been completed and some staff were allowed back onto campus. A new Scan & Deliver service was set up providing students the chance to request a copyright compliant scan of a book chapter or article, which would then be emailed to them by the Helpdesk teams on site. Previously this service had been available to distance students studying online only but never to all students at this scale. During the period of January to July 2021 447 requests were fulfilled in the Law Library alone. Shortly after the launch of ‘scan & deliver’ and ‘click & collect’ services began in February by offering items from the Main Library only. The stock from site libraries was able to be retrieved as procedures were established and developed, and in the period February to May 2021 414 item requests were fulfilled by the law library team.

The speed with which solutions were produced, tested and applied to the problems which arose in the early lockdown periods shows the immense dedication of the library services teams during an exceptionally busy time. As one site library operating as part of a large network it can be difficult to retain a balance between the individual identity of the law library and the united front of library services, a centralised department with some 200 staff working across the university. The unprecedented level of traffic in requests and new service delivery would not have been possible without the dedicated Helpdesk staff on-site.

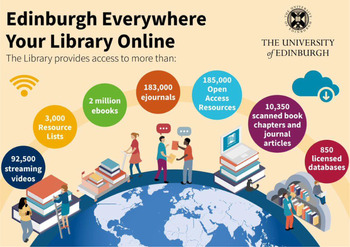

Despite the many challenges of the past year, some of the library's work has changed for the better. Book ordering processes have been streamlined and online resource lists are now required for every new course, where previously course organisers were not required to log their reading list in any centralised system. The shift to online learning has somewhat reduced the stress on capacity for print collections. A focus on online information literacy has been fast-tracked, allowing staff to prioritise critical information skills teaching to help prepare students to study and later work online. The LibSmart course hosted on the University's virtual learning environment was awarded funding to develop a new programme which included subject specific modules – the law librarian team wrote the legal information, and co-wrote, the government and policy research sections to help students across the university gain a better understanding of the legal information landscape.

As difficulties in accessing ebook and online resources have developed, a greater awareness of the importance of publisher licensing terms and Open Access have arisen. Academic researchers and teaching staff have been negatively affected by the restrictions placed on the resources they need across the board; this may lead to a gradual shift towards Open Access and prioritising the production of Open Educational Resources. For example, several of the resources created for the LibSmart modules have reuse and share alike Creative Commons licenses appended to them, with the intention of creating a higher standard of openly available academic resources particularly pertaining to Scots Law.Footnote 18

Figure 7: Screenshot of Scots Law presentation, by SarahLouise McDonald & Donna Watson, University of Edinburgh. (CC-BY-SA 4.0) https://prezi.com/view/GwQpcRQOIbrCMzOYBzjx/.

Some publishers have also taken this opportunity to improve their portfolio in the area of Scots Law, with Lexis Nexis being an example of a company who have worked with universities and practitioners to create new online content. Modules in LexisPSL have been updated to reflect current practice in devolved areas of law such as property and private client. They've also created an add-on subscription bundle for ebooks which includes some key texts for the curriculum, demonstrating that a strong relationship between publisher and institution can have benefits for both.

Although many academics will welcome the opportunity to return to campus in the coming semester, the surroundings they return to will differ from what they're used to in several significant ways. With reduced reliance on print material, students may find the library less busy than usual. On the other hand, while restrictions continue in Scotland social distancing may still need to be observed in indoor spaces which will further limit the availability of seating, compounding the difficulties concerning the existing study space. Academic staff may spend less time on-campus as they have grown used to working remotely, and therefore the strong community of Old College may evolve into something new.

However, as the development of Old College has shown, the identity of a space is not just in its physical surroundings or its print resources. The campus has been knocked down and rebuilt several times and each refurbishment has added a new layer to the complex history of the school. The university is a place of education for students but staff are also learning all the time; it's essential to take the best elements of tradition and use them to build a better future for both the university community and library profession. These past eighteen months have shown more than ever that a library is more than bricks and books, and though it is not possible to predict what form the service will take years from now, there is no doubt that the law library will endure.