Article contents

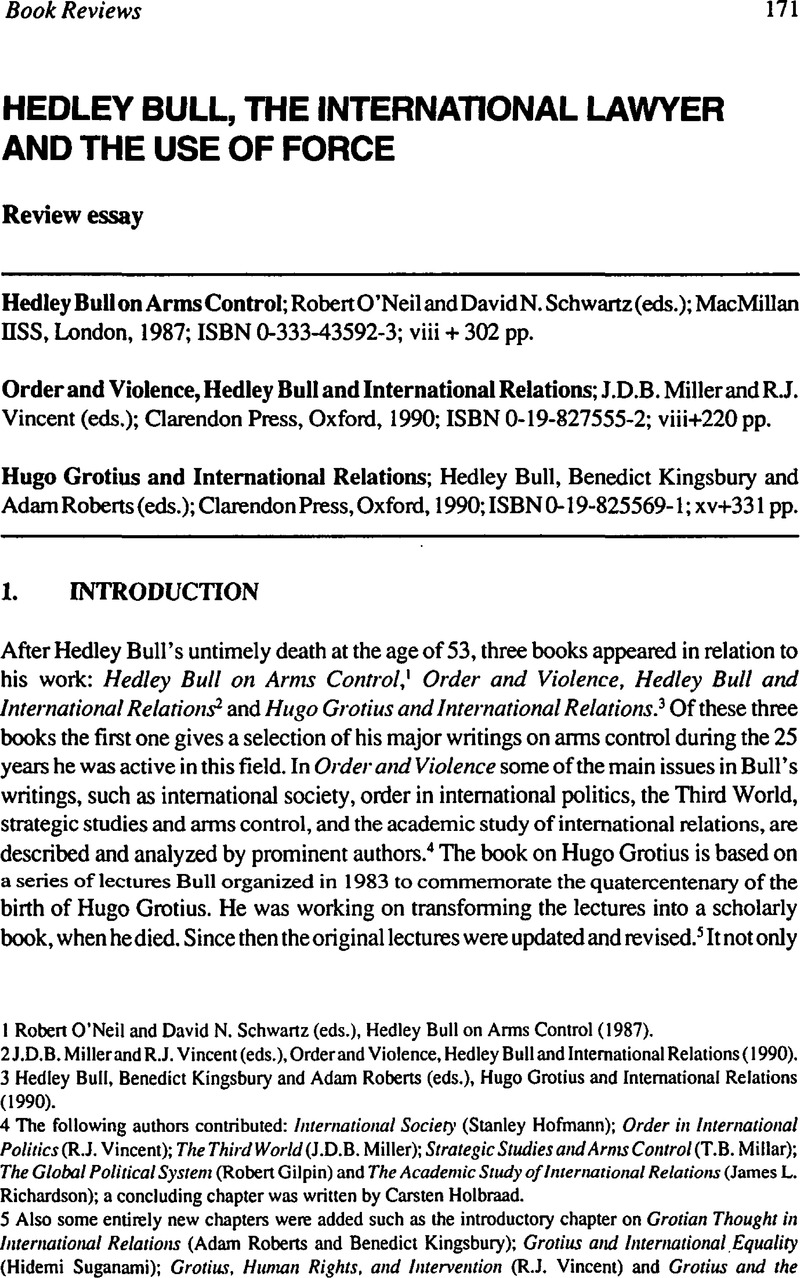

Hedley Bull, the International Lawyer and the Use of Force - Hedley Bull on Arms Control; Robert O'Neil and David N. Schwartz (eds.); MacMillan HSS, London, 1987; ISBN 0-333-43592-3; viii + 302 pp. - Order and Violence, Hedley Bull and International Relations; J.D.B. Miller and R.J. Vincent (eds.); Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1990; ISBN 0-19-827555-2; viii+220 pp. - Hugo Grotius and International Relations; Hedley Bull, Benedict Kingsbury and Adam Roberts (eds.); Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1990; ISBN 0-19-825569-1; xv+331 pp.

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 July 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Book Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Foundation of the Leiden Journal of International Law 1993

References

1 Robert O'Neil and David N. Schwartz (eds.), Hedley Bull on Arms Control (1987).

2 J.D.B. Miller and R.J. Vincent (eds.), Order and Violence, Hedley Bull and International Relations( 1990).

3 Hedley Bull, Benedict Kingsbury and Adam Roberts (eds.), Hugo Grotius and International Relations (1990).

4 The following authors contributed: International Society (Stanley Hofmann); Order in International Politics (R.J. Vincent); The Third World (J.D.B. Miller); Strategic Studies and Arms Control (T.B. Millar); The Global Political System (Robert Gilpin) and The Academic Study of International Relations (James L. Richardson); a concluding chapter was written by Carsten Holbraad.

5 Also some entirely new chapters were added such as the introductory chapter on Grotian Thought in International Relations (Adam Roberts and Benedict Kingsbury); Grotius and International Equality (Hidemi Suganami); Grotius, Human Rights, and Intervention (R.J. Vincent) and Grotius and the Development of International Law in the United Nations Period (Rosalyn Higgins). Next to Bull's contribution on The Importance of Grotius in the Study of International Relations the book furthermore contains contributions on: Grotius and the International Politics of the Seventeenth Century (C.G. Roelofsen); Grotius and Gentili (Peier Haggenmacher); Grotius's Place in the Development of Legal Ideas about War (G.I.A.D. Draper); Grotius and the Law of the Sea and Grotius' Influence in Russia (W.E. Butler); Are Grotius' Ideas Obsolete in an Expanded World (B.V.A. ROIing) and The Grotius Factor in International Law and Relations: a Functional Approach (Georg Schwarzenberger).

6 One can see this reflected for instance in the work of Gerrit W. Gong, one of his students, who wrote The Standard of ‘Civilization’ in International Society (1984), with a foreword by Bull. Gong focussed on the standard of civilization as a legal principle in international law. Cf. Art. 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice ‘recognized by civilized nations’ [E.M.]. Here we find again the elements of ‘international society’ and ‘international law’.

7 For more detailed discussions regarding the different contributions see reviews such as: David J. Bederman, 86 AJIL 411–412 (1992); Kinji Akashi, NILR 64–66 (1991); Carl Landauer, 33 Harv. Im'l L.J. 327–33(1992).

8 Few of Martin Wight's works were published during his lifetime. Important are his Western Values in International Relations 89–131 and The Balance of Power 149–175 in H. Butterfield and M. Wight, Diplomatic Investigations (1969, 1st ed. 1966); H. Bull (ed.), Systems of States (1979); H. Bull and C. Holbraad (eds.), Power Politics (1978) and G. Wight and B. Porter (eds.). International Theory, The Three Traditions (1991).

9 “These lectures made a profound impression on me, as they did on all who heard them. Ever since that time I have felt in the shadow of Martin Wight's thought – humbled by it, a constant borrower from it, always hoping to transcend it but never able to escape from it”, H. Bull, Martin Wight and the Theory of International Relations, delivered as the Second Martin Wight Memorial Lecture on January 29, 1976 at the LSE and reprinted as an introduction to Martin Wight, International Theory, supra note 8, at ix.

10 “For the Machiavellians -who included such figures as Hobbes, Hegel, Frederic the Great, Cllmenceau, the twentieth-century Realists such as Carr and Morgenthau- the true description of international politics was that it was international anarchy, a war of all against all […]; it was for each state or ruler to pursue its own interest: the question of morality in international politics, at least in the sense of moral rules which restrained states in their relations with one another, did not arise. For the Grotians -among whom Wight included the classical international lawyers [italics added, E.M.] together with Locke, Burke, Castlereagh, Gladstone, Franklin Roosevelt, Churchill- international politics had to be described not as international anarchy but as international intercourse, a relationship chiefly among states to be sure, but one in which there was not only conflict but also cooperation. To the central question of Theory of International Relations the Grotians returned the answer that states, although not subject to a common superior, nevertheless formed a society – a society that was no fiction, and whose workings could be observed in institutions such as diplomacy, international law, the balance of power and the concert of great powers. States in their dealings with one another were not free of moral and legal restraints: the prescription of the Grotians was that states were bound by the rules of international society they composed and in whose continuance they had a stake. The Kantians rejected both the Machiavellian view that international politics was about conflict among states, and the view of the Grotians that it was about a mixture of conflict and co-operation among states. For the Kantians it was only at a superficial and transient level that international politics was about relations among states at all; at a deeper level it was about relations among human beings of which states were composed […]. The Kantians, like the Grotians appealed to international morality, but what they understood by this was not the rules that required states to behave as good members of the society of states, but the revolutionary imperatives that required all men to work for human brotherhood. See H. Bull, supra note 9, at xi–xii.

11 H. Bull, id. at. xi.

12 H. Bull, The Anarchical Society, A Study of Order in World Politics (1977), at 24.

13 “Bull rejected a purely Hobbesian view of international affairs as a state of war, or a struggle of all against all. […] Bull also rejects what he considers to be Kant's universalism and cosmopolitanism […]” See S. Hoffman, International Society, in J.D.B. Miller et al. (eds.), supra note 2, at 23–24. See also R.J. Vincent, Order in International Politics, in J.D.B. Miller et al. (eds.), supra note 2, at 41.

14 See H. Bull, supra note 12, at ix; H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law (1978); R.J. Vincent, id., at 44; C. Holbraad, Conclusion: Hedley Bull and International Relations, in J.D.B. Miller et al. (eds.), supra note 2, at 189.

15 H. Butterfield et al. (eds.), supra note 8, preface at 11.

16 H. Bull, Society and Anarchy in International Relations, in Herbert Butterfield et al. (eds.), supra note 8, at 35–50.

17 H. Bull, The Grotian Conception in International Society, in H. Butterfield et al. (eds.), supra note 8, at 51–73.

18 H. Bull and Adam Watson, The Expansion of International Society (1984). Besides his contribution to the introduction and the conclusion as an editor, Hedley Bull also contributed the chapters European States and African Political Communities (at 99–114) and The Emergence of a Universal International Society (at 117–126).

19 H. Bull, Justice in International Relations, the 1983–84 Hagey Lectures, University of Waterloo (1984).

20 H. Bull, The Importance of Grotius in the Study of International Relations, in H. Bull et al. (eds.), supra note 3, at 65–93.

21 H. Bull (ed.). Intervention in World Politics (1984). Next to the introduction and the conclusion Hedley Bull's contribution is Intervention in the Third World at 135–156.

22 A study of justice in world politics “might yield some very different perspectives from those that are expressed here” (in The Anarchical Society, E.M.): see H. Bull, supra note 12, at xiii.

23 M. Howard, Hedley Bull: A Eulogy for his Memorial Service, in R. O'Neill et al. (eds.), supra note 1, at 275.

24 “[…] a classic of lucid judgement and common sense, had an international impact, on practitioners as well as theorists”, M. Howard, id., at 276.

25 J.D.B. Miller, Hedley Bull, 1932–1985 in J.D.B. Miller et al. (eds.), supra note 2, at 7.

26 H. Bull, International Theory, the Case for a Classical Approach, reprinted in Klaus Knorr and James N. Rosenau (eds.). Contending Approaches to International Politics (1969), at 20–38.

27 “From one perspective this stands as the classic refutation of the pretensions of the behaviouralist school, from another as the classic illustration of the wrong-headedness and obscurantism of the traditionalists”, James L. Richardson, The Academic Study of International Relations, in J.D.B. Miller et al. (eds.), supra note 2, at 140.

28 Id., at 140.

29 “[…] and that is characterized above all by explicit reliance upon the exercise of judgement and by the assumptions that if we confine ourselves to strict standards of verification and proof there is very little of significance that can be said about international relations, that general propositions about this subject must therefore derive from a scientifically imperfect process of perception or intuition, and that these general propositions cannot be accorded anything more than the tentative and inconclusive status appropriate to their doubtful origin”; H. Bull, supra note 26, at 20.

30 “Some of them dismiss the classical theories of international relations as worthless, and clearly conceive themselves to be the founders of a wholly new science. Others concede that the products of the classical approach were better than nothing, and perhaps even regard them with a certain affection, as the owner of a 1965 model might look at a vintage motor car. But in eiher case they hope and believe that their own son of theory will come wholly to supersede the older type […]”, id., at 21.

31 Text infra, 3.1.2.

32 “By world order I mean those patterns or dispositions of human activity that sustain the elementary or primary goals of social life among mankind as a whole”, H. Bull, supra note 12, at 20.

33 Id., at xi.

34 See H. Bull, supra note 16, at 48.

35 Text supra, 2.

36 H. Bull, supra note 17, at 52.

37 S. Hoffmann, supra note 13, at 15.

38 H. Bull, supra note 20, at 78–91.

39 H. Bull, supra note 12, at 9.

40 Id., at 13.

41 H. Bull, id., at 233.

42 Bull does not treat international organisations separately, but only in terms of the contribution they make to the basic institutions; supra note 117.

43 Compare the decisions within the CSCE system that are of a political and not legally binding character.

44 H. Bull, supra note 12, at 129.

45 H. Bull, id., at xiv. In this context Bull offers a rare view on his private opinion: “It is, I believe, one of the defects of our present understanding of world politics that it does not bring together into common focus those rules of order or coexistence that can be derived from international law and those rules that cannot, but belong rather to the sphere of international politics. Id., at xiv.

46 Id., at 128.

47 Id., at xiii.

48 Id., at 130.

49 See H. Kelsen, General Theory of Law and State (1949), in particular Chapter VI, at 328–388.

50 H. Bull, supra note 12, at 130.

51 Id., at 132.

52 Id., at 131.

53 “It is only if power, and the will to use it, are distributed in international society in such a way that states can uphold at least certain rights when they are infringed, that respect for rules of international law can be maintained”. See H. Bull, supra note 12, at 131/132.

54 Id., at 132–133.

55 Supra note 17.

56 H. Bull, supra note 12, at 135, refers to Hart, supra note 14, at 231, where Hart adds two comments “First that the analogy is one of content, not of form. Secondly that, in this analogy of content, no other social rules are so close to municipal law as those of international law”.

57 H. Bull, supra note 12, at 136.

58 Id., at 140.

59 Id., at 142.

60 Id., at 143.

61 “The achievement of international law in our own times may be not to have brought about any strengthening of the element of order in international society, but rather to have helped to preserve the existing framework of international order in a period in which it has been subject to especially heavy stress”. See H.Bull, id., at 160.

62 Id., at 156. Bull understands consensus as general agreement, but rather in the sense of the agreement of the overwhelming majority in favour of the view that a particular rule has the status of law (at 156/157). The promising aspect would be that “[recognition of its legal status cannot be averted merely because a particular recalcitrant state or group of states withholds its consent”(at 156).

63 Id., at 158.

64 Id., at 149–150

65 Id., at 160. See also Hedley Bull, International Law and International Order, 26.3 International Organization (1972), at 585–586.

66 Hedley Bull, I Arms Control and World Order, 1 International Security (1976), reprinted in R. O'Neill et al. (eds.), supra note 1, at 191–206.

67 Id., at 197.

68 Id., at 194.

69 Id., at 195.

70 Id., at 196.

71 Bull distinguishes five areas in which demands for justice have been put forward by the Third World: (1) demands for equal rights of sovereignty or independence; (2) demands for just or equal application of the principle of national determination; (3) demands for racial justice or equality; (4) demands for justice in the economic domain; (5) demands for justice in matters of the spirit of the mind. See H. Bull, supra note 22, at 2–5.

72 Id., at 10.

73 Id., at 10.

74 Id., at 10.

75 Id., at 2.

76 H. Bull, supra note 2, at 196.

77 Text supra, 5.1.2.

78 “There is no convincing evidence that the system of states is in decline and about to give place to some different form of universal political organization”; H. Bull, supra note 66, at 197–198 “[…] The problem of world order is not that of how to move beyond the state system, but that of how to make it work”; id., at 198.

79 Id., at 198.

80 Id., at 199.

81 “It follows from this that our conception of world order should not be shaped by prescriptions for a more centralized system, expressed in an expanding United Nations or upon ‘non-territorial centralizing direction’. The third world countries are oposed to centralizing tendencies in world politics, percieving correctly that if more powerful centralized institutions were to be established now, they would probably be controled by the present great powers and would reflect their special interest. It is more likely that world order will continue to rest upon a decentralized system, and that if a greater role is to be played by international institutions these will be regional ones rather than global ones”; id., at 199.

82 Id., at 190.

83 Id., at 200.

84 Id., at 200.

85 Id., at 205.

86 H. Bull, supra note 19, at 71. On Bull's views on Grotius see also C.G. Roelofsen, Grotius and the ‘Grotius Heritage’ in International Law and International Relations, Grotiana(ns) II (1990), at 6–28.

87 H. Bull, supra note 17. at 55. C. Van Vollenhoven in his The Framework of Grotius' Book de lure Belli Ac Pacis -1625- (1931) argues that Grotius makes adistinction between “The first right of war: Enforcement of state duties” (at 66) and “The second right of war: punishment of state crimes” (at 80). “Grotius expressel y denied the existence of a third right of armed coercion against states; be it a right to wage war from fear that crimes may be committed […] – be it a right to wage war because a prince oppresses his own citizens unless the crime smells to high heaven […] – be it a right to wage war on backward nations […] or on the ground of ingratitude” (at 81–82).

88 H. Bull, supra note 17. at 54.

89 As opposed to the Clausewitz war. See also E.P.J. Myjer, Militaire Veiligheid door Afschrikking, Verdediging en hei Geweldverbod in het Handvest van de Verenigde Naties (Military Security via Deterrence, Defence and the Ban of Force in the UN Charter) (1980), at 5.

90 H. Bull, supra note 17, at 56.

91 H. Bull, supra note 19, at 78. Basing himself on Grotius, Lauterpacht says that this law of nature “[…] is the law which is most in conformity with the social nature of man and the preservation of human society – a law of nature, in its ‘primary sense’, which includes the duty of refraining from appropriating what belongs to others, restoration of what belongs to them, the obligation to fulfil promises, reparation of injury, and the right to inflict punishment”; see H. Lauterpacht, The Grolian Tradition in International Law, British Yearbook of International Law (1946), at 7.

92 H. Bull, supra note 20, at 79 and 88.

93 Id., at 88.

94 Id..

95 Id..

96 Id., at 55.

97 Id., at 88.

98 Id., at 86.

99 During World War I, Van Vollenhoven in De Drie Treden van hei Volkenrecht (1918) (The Three stages in the Evolution of the Law of Nations) (1919) attacked in clear and uncompromising terms what he called the second stage of international law (second international law), or the international law of De Vattel of which the central thesis is the state sovereignty implying that it is up to the state to decide whether it wants to wage war or not

100 H. Lauterpacht, supra note 91, at 1–53.

101 H. Bull, supra note 17, at 51.

102 Id., at 69.

103 Id., at 55. See also supra note 20. at 89.

104 H. Bull, supra note 20. at 79.

105 Id., at 89. Röling, one of the Tokyo judges, was more unambiguous: “The judgement of Nurenberg stated that “the very essence of the Charter (of Nurenberg, E.M.) is that the individuals have international duties which transcend the national obligations of obediences imposed by the individual State. Nurenberg and Tokyo signified a revollion in law”. B.V.A. Röling, International Law in an Expanded World (1960), at xxiii.

106 H. Bull, supra note 17. at 70–71.

107 H. Bull, supra note 20, at 76.

108 “[…] It has become a dangerous theory. Some aspects of it, such as the duty to refuse participation in an illegal war, may still play a decisive role for states and individuals”; see B.V.A. Röling, Jus ad Bellum and the Grotian Doctrine, in International Law and The Grotian Heritage (1985), at 133. See also his Are Grotius' Ideas Obsolete in an Expanded World?, in H. Bull et al (eds.), supra note 3, at 281–299.

109 H. Bull, Commentary on Röling supra note 108, at 138.

110 “[…] the doctrine today of a right to wage just wars of national liberation […] asserts a right that is not strictly speaking one of self-defence, but a right to begin war so as to enforce rights”, id., at 139.

111 Id., at 138.

112 Id., at 139.

113 Text supra, 3.1.2..

114 Text supra, at 5.

115 I agree with Lachs: “thus political conditions are favourable for the opening of a new are in international relations, beginning with the reshaping of Europe. It will be an era in which law will play a decisive role by denning the rights and obligations of states and their mutual relationships. With the instruments of law becoming even more effective, power in its physical dimensions will lose its importance”; see Manfred Lachs, Politics and International Law – Vision of Tomorrow, in P. de Klerk and L. van Maarle, Een kwestie van Visie (1990), at 78.

116 “You see, as the Cold War drew to an end we saw the possibilities of a new order in which nations worked together to promote peace and prosperity. I am not talking here of a blueprint that will govern the conduct of nations or some supernatural structure or institution. The new world order does not mean surrendering our national sovereignty or forfeiting our interests. It really describes a responsibility imposed by our success. It refers to new ways of working, with other nations to deter aggression and to achieve stability, to achieve prosperity and, above all, to achieve peace. It springs from hopes for a world based on a shared commitment among nations large and small, to a set of principles that undergird our relations. Peacful settlement of disputes, solidarity against aggression, reduced and controlled arsenals, and just treatment of all peoples. This order, this ablility to work together got its first real test in the Gulf war”; George Bush, The Possibility of A New World Order, Unlocking the Promise of Freedom, April 13,1991 in (LVII) Vital Speeches of the Day, No. 15, May 15, 1991.

117 See H. Bull, supra note 12, at xiv.

- 1

- Cited by