1. Introduction

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs)Footnote 1 have proved to be highly influential in shaping law, policy, advocacy and scholarship in the business and human rights (BHR) field.Footnote 2 Irrespective of whether human rights due diligence (HRDD) is ‘at the heart’ of the UNGPs or not,Footnote 3 this has become the new lingua franca of discourse around the business responsibility to respect human rights.Footnote 4 The language of HRDD is being used by states, international organizations, businesses, industry associations, civil society organizations (CSOs), trade unions, scholars, lawyers, and policy makers. Moreover, the concept of HRDD under the UNGPs is also informing mandatory HRDD laws at national or regional level in EuropeFootnote 5 as well as the draft of the proposed international legally binding instrument.Footnote 6

It is therefore timely to interrogate the potential and limitations of mandatory HRDD laws in preventing business-related human rights abuses. As part of this interrogation, this article develops a two-layered critique of mandatory HRDD laws. As part of the first layer, it problematizes the very concept of HRDD as articulated by the UNGPs. I will argue that due to various conceptual, operational and structural limitations, HRDD alone – even if practiced by corporations – will not bring the desired changes for rightsholders. The second layer of critique concerns the content of mandatory HRDD laws that have been enacted so far: leaving aside inherent limitations of HRDD, these laws are merely half-hearted attempts to tame business-related human rights abuses and hold the relevant corporate actors accountable. If not drafted properly, mandatory HRDD laws may in fact prove counter-productive by either encouraging ‘cosmetic compliance’ on the part of corporationsFootnote 7 or institutionalizing HRDD as a defence to legal liability. They may also help in covering up existing imbalances of power between states, corporations and communities, instead of addressing them.

Therefore, regulators and policy makers should carefully consider limitations of HRDD in practice and look beyond making HRDD mandatory to make any real difference to the situation of rightsholders on the ground or bring a fundamental shift in how businesses are currently run. They should do so despite calls to preserve, what I would call, the ‘sanctity’ or ‘conceptual purity’ of HRRD under the UNGPs.Footnote 8 (Mandatory) HRDD should not end up becoming the end in itself. Rather, HRDD should be treated merely one of the many means to ensure that businesses respect internationally recognized human rights, and states should use all available regulatory options as part of their duty under Pillar I of the UNGPs instead of focusing solely on enacting mandatory HRDD laws.

I begin in Section 2 by situating my critique in the context of theorical literature concerning vulnerability of rightsholders and power imbalances between rightsholders and corporations. Because of these reasons, states have an indispensable role in regulating corporate behaviour, including by orchestrating the potential of various market actors towards this goal. Section 3 of the article outlines potential advantages of HRDD and also highlights why HRDD is slowly changing its colour from an extra-legal to a legal notion. Section 4 then elaborates various conceptual, operational and structural limitations inherent in the concept of HRDD as articulated under the UNGPs, while Section 5 shows why the conversion of HRDD from a voluntary to a mandatory process in itself will not address many of these limitations. I will argue that mandatory HRDD laws should satisfy, at a minimum, six preconditions in order to be able to protect effectively people and the planet from business-related harms: require holistic HRDD, capture as many businesses as much as feasible, address power imbalances, go beyond process, draw certain ‘red lines’ and provide for effective access to remedy.

Section 6 critically examines the extent to which five mandatory HRDD laws enacted in Europe so far – the French Duty of Vigilance 2017, the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act 2019,Footnote 9 the Swiss Due Diligence Legislation 2021, the German Law on Supply Chain Due Diligence 2021,Footnote 10 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2021Footnote 11 – meet these six effectiveness preconditions. It will be argued that while these mandatory HRDD laws are a step in the right direction to encourage businesses to take their human rights responsibilities seriously, they might only bring limited positive change in the situation of affected rightsholders. Section 7 offers some concluding thoughts as the regulatory trajectory required to bring more systemic changes to the current relation of business with society.

Due to space constraints, this article will not consider other issues related to Pillar II or HRDD. For example, as other scholars and I have argued,Footnote 12 the minimum responsibility of businesses should not be limited to respecting human rights: rather, they should also have a responsibility to protect and fulfil human rights. Pillar II of the UNGPs both under-sells (by not including the responsibility to protect and fulfil human rights as part of social expectation) and over-sells (by including some ‘responsibility to protect’ elements under the ‘responsibility to respect’) the human rights responsibility of businesses. This pragmatic approach is normatively unsound. It is also creating practical challenges in the legalization of Pillar II. Similarly, this article will not consider whether the three-prong recipe proposed by Principle 15 of the UNGPs to meet the responsibility to respect human rights is practicable for micro enterprises or businesses which are part of the informal economy. Finally, as the European Commission’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive has not been adopted at the time of writing this article,Footnote 13 I will not analyse it. However, the two-layered critique of mandatory HRDD laws should generally hold even in relation to the proposed Directive.

2. Analytical framework

This article invokes two theoretical strands of literature to critique mandatory HRDD laws. The first is the concept of vulnerability, especially vulnerabilities of affected individuals and communities. The second strand concerns the power enjoyed by corporations in the current free market economy and the consequent power imbalances between corporations and rightsholders. There is a correlation between these two strands because some vulnerabilities of rightsholders are linked to these power imbalances.

Peroni and Timmer note that ‘harm and suffering feature centrally in most accounts of vulnerability’.Footnote 14 Because of their vulnerability, rightsholders are ‘constantly susceptible to harm’.Footnote 15 In the context of this article, harm to people and the planet is caused, or contributed to, by business operations.Footnote 16 Although all human beings are vulnerable in certain ways, some rightsholders and communities are more vulnerable due to their special circumstances concerning age, colour, caste, class, ethnicity, religion, language, literacy, access to economic resources, marital status, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, and migration, indigenous or minority status. While this categorization of vulnerability may lead to stigmatization and stereotyping of certain rightsholders or groups,Footnote 17 it also opens pathways for substantive equality and need for decision-makers to be responsive to these differences and unique vulnerabilities.Footnote 18

The conceptualization of HRDD under the UNGPs is conscious of the vulnerability of rightsholders and therefore requires ‘meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders’.Footnote 19 Moreover, ‘where such consultation is not possible, business enterprises should consider reasonable alternatives such as consulting credible, independent expert resources, including human rights defenders and others from civil society’.Footnote 20 The UNGPs also encourage business enterprises to ‘pay special attention to any particular human rights impacts on individuals from groups or populations that may be at heightened risk of vulnerability or marginalization’.Footnote 21

The real problem is that these HRDD steps recognize but do not address adequately various vulnerabilities of communities related to information, expertise, economic dependency, resources and historical injustices that exist on the ground. For example, members of a community consulted about a mining or hydropower project may not fully understand long and complex impact assessment reports solicited by the concerned corporations or may need much more time to digest and discuss internally the viability of a given project. Alternatively, workers trapped in modern slavery in the supply chains of a corporation may not be aware of their rights or may lack the ability to complain about abuses of rights due to their dependency on such exploitative jobs for survival.Footnote 22

Although access to remedy is not a part of HRDD, it is an integral component of the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, especially because prevention is never full proof. However, various vulnerabilities also undermine the capability of victims of business-related human rights abuses to seek an effective remedy. Jos, for instance, illustrates how corporations exploit the inequality of bargaining power under legal waivers to deny victims effective remediation for human rights abuses.Footnote 23 Principle 31 of the UNGPs outlines several effectiveness criteria for non-judicial grievance mechanisms. However, most of these criteria are again process-related and do not pay adequate attention to achieving effective remedial outcomes. Consequently, the result, as shown by Wielga and Harrison, often is that even a grievance mechanism designed in line with effectiveness criteria may fail to deliver effective remedy to rightsholders in practice.Footnote 24 One reason for such an unsatisfactory outcome is that these grievance mechanisms are not responsive to specific vulnerabilities of victims. Nor do they often take affirmative steps to overcome power imbalances.Footnote 25

Brinks et al. argue that ‘the inequalities and disparities of power and wealth that are a key characteristic of the contemporary global economy’.Footnote 26 Powers that corporations have come to enjoy in the current economic model is the main reason for such disparities of power. Birchall, for instance, analyses corporate power over human rights in four settings: power over individuals, power over materialities, power over institutions, and power over knowledge.Footnote 27 Neither the UNGPs nor the mandatory HRDD laws seem to challenge the corporate power in any of these settings. In fact, even human rights experts engaged by corporations to conduct HRDD, who confer a certain level of legitimacy to corporate actions,Footnote 28 may inadvertently entrench further the power imbalances between rightsholders and corporations.

Addressing these power imbalances would require regulators – whether state-based or market-based – to be responsive to this state of play and take proactive measures. This responsiveness is different from the one articulated by Ayres and Braithwaite as part of responsive regulation:Footnote 29 while the former focuses on the position of rightsholders vis-à-vis corporations, the latter focuses on the conduct of corporations as regulatees. It is trite that states alone cannot regulate effectively corporations. For example, they often have to harness and facilitate the regulatory potential of other non-state actors. However, this orchestrating role of statesFootnote 30 should not be at the cost of their non-delegable role in effectively regulating corporations and addressing power imbalances. In other words, the reliance on market forces to regulate corporate behaviour too has its limitations.

Within this analytical framing, this article develops a critique of mandatory HRDD laws. The objective of this critique is not to dismiss the value of such laws. Rather, the goal is to show the limitations of the very concept of HRDD and how this has been implemented so far by various laws in Europe. Regulators and policy makers should, therefore, develop more robust mandatory HRDD laws as well as explore other regulatory tools which are outcome-oriented and pay more attention to corporate accountability.

3. Potential of (mandatory) human rights due diligence

Under Pillar II of the UNGPs, all business enterprises have a responsibility to respect all internationally recognized human rightsFootnote 31 ‘regardless of their size, sector, operational context, ownership and structure’.Footnote 32 Respecting rights means that businesses ‘should avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved’.Footnote 33 Businesses have a responsibility, though of a varying degree, if they cause, contribute to, or be directly linked to adverse impacts through their operations, products or services by their business relationships.Footnote 34 Moreover, if a business enterprise has leverage (or can acquire it) to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts, it should exercise it. Footnote 35

In addition to making a policy commitment to respect human rights at the most senior level and having processes in place to enable remediation of any adverse impact they cause or contribute to,Footnote 36 conducting HRDD is the main pathway prescribed by the UNGPs for businesses to discharge their responsibility to respect human rights. The section showcases the potential of HRDD as a process as well as the value addition of this process being made mandatory by laws.

3.1 Potential of the HRDD process

HRDD enables business enterprises ‘to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their adverse human rights impacts’. Footnote 37 It is an ongoing process entailing four steps: (i) identify and assess any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts; (ii) take appropriate action by integrating the findings from impact assessments; (iii) track the effectiveness of their response; and (iv) communicate externally how adverse impacts are being addressed.Footnote 38 If it is necessary to prioritize actions to address actual and potential adverse human rights impacts, business enterprises ‘should first seek to prevent and mitigate those that are most severe or where delayed response would make them irremediable’.Footnote 39 While remediation is not part of HRDD, it is in built in Pillar II as part of corporate responsibility to respect human rights. Therefore, if a business enterprise identifies that it has ‘caused or contributed to adverse impacts’, it should ‘provide for or cooperate in their remediation through legitimate processes’.Footnote 40

HRDD seeks to shift the narrative around the business responsibility to respect human rights from ‘naming and shaming’ to ‘knowing and showing’. As Ruggie explained: ‘To discharge the responsibility to respect human rights requires that companies develop the institutional capacity to know and how that they do not infringe on others’ rights.’ Footnote 41 Drawing on processes already used by corporations on how ‘they are accounting for risks’ in other domains, Ruggie introduced HRDD as ‘a means for companies to identify, prevent, mitigate, and address adverse impacts on human rights’. Footnote 42 At the same time, as HRDD is aimed at protecting rightsholders rather than managing risks to corporations, it is consciously differentiated from typical corporate due diligence processes in several ways. Footnote 43 For example, HRDD is not an one-off exercise and requires meaningful consultation with the relevant stakeholders.

HRDD has become the lingua franca in the BHR field. This is an impressive achievement in the space of just 11 years. However, the common usage of a terminology does not necessarily denote a common understanding about a given concept. One could draw an analogy with the concept of the rule of law. Even if we leave aside debates about the ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ versions of the rule of law, the term is used very differently in liberal democracies from how this is invoked, for example, by the Chinese government.Footnote 44 We can see the same trend in relation to HRDD. Quijano and Lopez note that there are ‘significant divergences among scholars and stakeholders in their understanding of the concept and, importantly, its relationship, if any, with legal liability’.Footnote 45 Scholars have fiercely debated the origin of HRDD and its relationship with similar concepts in other branches of law.Footnote 46 These divergent understandings about HRDD are also reflected in what mandatory HRDD laws actually mean and entail for businesses. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in an Issues Paper noted that ‘there is not one, single model for mandatory human rights due diligence regimes’ and that ‘when people are discussing mandatory human rights due diligence regimes they are potentially discussing a wide range of legal and regulatory possibilities’.Footnote 47

Despite these divergences in the understanding of HRDD, it has significant potential in at least three ways: socialization, common currency, and prevention. As HRDD offers a business-familiar language and process, this has helped significantly in engaging businesses on human rights issues. Due diligence is something which businesses can relate to, as it has been an established practice of corporations for taking routine commercial decisions – from hiring to investment, takeovers, mergers and acquisitions, taxation and anti-bribery. This familiarity makes corporate embracement of HRDD much easier. As noted below, this advantage has its trade off though. Since old habits die hard,Footnote 48 businesses may continue to focus on managing risks to themselves rather than to rightsholders.

In the BHR field, HRDD provides a common currency as to what is expected of business enterprises to respect human rights. This means that all stakeholders such as states, business enterprises, CSOs, trade unions and lawyers are able to speak the same language when having conversations about the human rights responsibility of business.

HRDD provides a prevention blueprint for businesses by asking them to ‘know and show’ their adverse impacts. HRDD:

is the practice of a company looking for risks to people which are connected to what the company does, including who it relates to, and taking appropriate action to ensure that those risks do not turn into an adverse impact on people’s rights.Footnote 49

Therefore, if done in a meaningful manner and regularly,Footnote 50 HRDD should be able to pre-empt a significant percentage of corporate human rights abuses. HRDD could also play a preventive role in another way: conducting appropriate HRDD ‘should help business enterprises address the risk of legal claims against them by showing that they took every reasonable step to avoid involvement with an alleged human rights abuse’.Footnote 51 HRDD may though not be a complete or automatic defence to legal liability.

3.2 Value addition of the legalization of HRDD

Human rights are not optional, either for states or businesses. From this normative perspective, the responsibility of businesses to respect internationally recognized human rights should not be voluntary.Footnote 52 Yet, for pragmatic reasons, the UNGPs differentiate the voluntary responsibility of businesses under Pillar II from the obligatory duty of states under Pillar I.Footnote 53 Pillar II of the UNGPs – which includes the HRDD process – is not grounded in legal norms. Footnote 54 Ruggie and Sherman asserted that ‘the corporate responsibility to respect human rights under the Guiding Principles … is neither based on nor analogizes from state-based law. It is rooted in a transnational social norm, not an international legal norm’. Footnote 55 In other words, instead of being legally binding, Pillar II has been envisaged to operate as a supra-legal norm coexisting with other (legal) norms.

This pragmatic approach has helped in socialization and normalization of the business responsibility to respect human rights. At the same time, the experience of the UNGPs’ implementation in first 11 years shows that most businesses are not taking their soft responsibility seriously. The impressive on-paper uptake of HRDD as an extra-legal norm (including by many big business enterprises and major industry associations) has not been matched by the practice of HRDD. Ruggie claimed that the voluntary corporate responsibility to respect human rights standards under the UNGPs has ‘several bites’.Footnote 56 For example, advocacy for HRDD by various stakeholders such as consumers, investors and CSOs may pressurize businesses to take seriously their human rights responsibilities. However, these bites are patchy and unpredictable in practice and do not hurt all types of businesses. Consequently, a great majority of corporations are not yet walking the talk on HRDD. Footnote 57 For example, in the 2020 Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, 46.2 per cent of 229 assessed corporations from five different sectors did not score any points for HRDD. Footnote 58 Moreover, most of the corporations captured in the 2022 Benchmark ‘are taking a hands-off approach to human rights in their supply chains’,Footnote 59 which is not in line with the UNGPs. The reality is that in ‘the absence of a legally binding requirement, only a minority of well-intended companies or those facing consumer scrutiny decide to invest in improving their performance’.Footnote 60 In addition, voluntary frameworks do not often ‘provide victims of corporate misconduct with remedy, resulting in a denial of their human right to access justice’.Footnote 61

This led to many CSOs demanding for mandatory HRDD lawsFootnote 62 and also supporting the proposed treaty process as part of the Treaty Alliance. The civil society advocacy has started to bear some fruits with France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway and Germany adopting mandatory HRDD laws, and the European Commission releasing a draft of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive in February 2022.Footnote 63 We should see the push for the legalization or hardening of the UNGPs – including HRDD – at the national, regional and international levels in this context.

These attempts to legalize the extra-legal norm of Pillar II are welcome, because the UNGPs recommend states to adopt a ‘smart mix’ of measures to promote business respect for human rights. Footnote 64 The regulatory vision of a smart mix, which envisages a complementary role for voluntary and binding measures at both national and international levels, seeks to ‘take us beyond the stalemate induced by the mandatory-vs.-voluntary divide’.Footnote 65 From this perspective, the legalization of HRDD should add value to the current regulatory ecosystem in several ways. First, it should encourage more enterprises and their business partners to conduct HRDD. Second, mandatory HRDD laws should reduce free riders (i.e., those businesses which see more economic benefits in ignoring human rights standards) and in turn creating a global level playing field for businesses. Third, these laws would also enhance the leverage of market actors over business enterprises in integrating respect for human rights as a new normal of doing business. Fourth, mandatory HRDD law may reduce some imbalances of power between corporations and communities, e.g., by requiring disclosure of information or insisting on the need for meaningful consultations. Fifth, mandatory HRDD laws should open new pathways for access to remedy and corporate accountability due to the conversion of a social expectation into a legal requirement.

At the same time, the legalization of Pillar II to make HRDD mandatory should not erode the independent extra-legal status of the corporate responsibility to respect human rights. As I have argued elsewhere,Footnote 66 Pillar II should not be subsumed by Pillar I: rather, the former should stand independent in parallel to any legalization of the human rights responsibilities of business flowing from Pillar I.Footnote 67 Such an ‘independent but complementary’ status of Pillar II will be especially critical in situations where there is no legalization of HRDD, or legalization under Pillar I does not cover all human rights or all businesses, or mandatory HRDD laws do not provide for remediation.

It is also worth acknowledging that despite the popularity of ‘smart mix’ as a new regulatory mantra, the cleavage between voluntary and mandatory measures remains, as some states and business associations continue to resist the legalization of business responsibility to respect human rights at national, regional and international levels. The support of some businesses and investors for mandatory HRDD laws should also be accepted with caution, as this may be part of a corporate ploy to undermine from the inside the robustness of such laws.Footnote 68 After all, corporate lobbying against such laws including liability provisions or providing for reversal in burden of proof is very much alive. Such lobbying may also have contributed to the delay on the part of the European Commission in releasing its draft Directive.Footnote 69

4. Limitations of human rights due diligence

There are a few studies suggesting that corporations are either not conducting HRDD despite making a commitment to respect human rights or not doing HRDD in line with the UNGPs,Footnote 70 thus casting doubts about its efficacy in preventing and mitigating adverse human rights impacts in practice. More importantly, HRDD under Pillar II of the UNGPs suffers from several conceptual, operational and structural limitations. Because of these limitations, we should not consider HRDD – irrespective of whether voluntary or mandatory – as a ‘fool-proof’ or ‘fix-all’ tool. States enacting mandatory HRDD laws as part of their Pillar I duty should keep this in mind.

4.1 Conceptual limitations

HRDD enables businesses to respect human rights by preventing adverse human rights impacts.Footnote 71 It embraces the methodology of ‘knowing and showing’: businesses should first know adverse impacts and then show to their stakeholders the steps taken to prevent or mitigate such impacts. To guide the scope of business responsibility and in turn HRDD, Principle 12 provides a definition of ‘internationally recognized human rights’ which enterprises should respect ‘at a minimum’. However, the relevance of some of these rights – articulated in state-focal international instruments – may not be obvious to many businesses, e.g., right of self-determination, protection against cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment, right to acquire a nationality, right to work, and right to housing. On the other hand, certain issues which may be very real to businesses on the ground are not adequately captured by the ‘moral minimum’ articulated by Principle 12. Environmental rights, climate change considerations or the human rights of women as elaborated in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women illustrative this limitation. In other words, the conceptual mooring of HRDD is not straight forward. Rather, it requires translation of state-focal human rights standards to non-state actors and if businesses own this translation exercise, this might result in weak or inconsistent adaptation of standards.

Second, as business responsibility to respect human rights under Pillar II is voluntary, conducting HRDD is also non-obligatory for businesses. This is a major limitation because market pressures or courts of public opinion do not always work against all enterprises. Nor are all businesses self-conscious of their human rights responsibilities. This means that only a small number of business enterprises have started doing some kind of HRDD. A 2018 report of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights concluded that ‘the majority of business enterprises around the world remain unaware, unable or unwilling to implement human rights due diligence as required of them in order to meet their responsibility to respect human rights’.Footnote 72 This position is confirmed by other studies and indicators.Footnote 73

Third, HRDD does not contemplate any responsibility to achieve a ‘result’, even in situations where adverse human rights impacts are caused or contributed to by a business enterprise.Footnote 74 The value of HRDD to achieve outcomes – in the form of non-infringement of human rights and/or effective remediation – from the perspective of rightsholders is still unproven.Footnote 75 One main reason for this limitation is perhaps that HRDD is a business-led process: rightsholders at risk are only expected to be consulted as passive participants, rather than being active agents. Therefore, some form of HRDD in practice often ends up becoming a social legitimization tool, because development projects still go ahead even if a significant portion of affected communities are against it. Out of many examples, one may refer to an integrated steel plant in the state of Odisha in India built by Jindal Steel Works (JSW). Despite opposition by thousands of farmers to acquire their land, the JSW’s project – at a site abandoned by POSCO after many years of protest by these farmers – is going ahead.Footnote 76 JSW has conducted a public consultation and offered alternative livelihood and employment package,Footnote 77 but these are essentially to ensure that the project goes ahead, rather to address genuine concerns of farmers.

Fourth, as Pillar II conflates the business responsibility to ‘respect’ and ‘protect’ human rights, this has implications for HRDD too. Businesses are expected to conduct HRDD in all variations of the tripartite typology (causation, contribution and direct linkage) envisaged by Principle 13. This however means that the HRDD process does not differentiate much between situations in which adverse human rights impacts are the result of an enterprise’s ‘own’ actions or omissions and where such impacts are the result of their business relationships with other parties.Footnote 78 For obvious reasons, the threshold to discharge the responsibility should be higher for the former set of situations and HRDD mere as a standard of conduct should not suffice in such cases.

Fifth, the UNGPs often use ‘prevention’ and ‘mitigation’ together. While it is true that not all risks or impacts could be prevented and every business activity would inevitably result in some adverse impact on people or the planet, there is a significant difference between prevention and mitigation from the perspective of rightsholders. However, this clubbing of mitigation with prevention without any clear differentiation or sequencing hierarchy in practice creates the impression that businesses may be justified to cause or contribute to adverse human rights impacts as long as they take certain steps to mitigate such impacts. This may encourage businesses to use the ‘cost benefit’ analysis to determine whether to prevent (which may require ceasing a business activity) or merely mitigate and later remediate harms.

Sixth, since remediation is not an integral part of HRDD, it often gets ignored or side-lined,Footnote 79 perhaps under the assumption that businesses should be able to prevent or mitigate most of adverse human rights impacts by conducting HRDD. However, prevention is never full proof. Nor should remediation be relegated only to situations where prevention fails.Footnote 80 Remedies could be preventive too.Footnote 81 Failure of businesses to conduct any HRDD or conduct HRDD in a tick-box manner should also trigger remediation.Footnote 82

4.2 Operational limitations

There are also operational limitations in the four-step HRDD process. For example, it does not adequately acknowledge or address the problems flowing from the imbalance of power, information and resources between businesses and rightsholders. Principle 18 expects businesses to do ‘meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders’. However, this does not go far enough in practice when the very consultation process is designed by actors in position of power, that is, an enterprise or an external consultant engaged by such an enterprise.Footnote 83 There are also asymmetries related to information and resources. In the absence of accessible information about a proposed project or the risk of losing a day’s wage for joining a consultation, affected communities may not be able to participate effectively in the HRDD process.

Another operational limitation arises from the conscious choice of business-friendly terminology built into HRDD.Footnote 84 As I have argued elsewhere, Pillar II’s preferred terminology of ‘adverse impact’ can hardly carry the weight of serious human rights abuses committed by or linked to businesses.Footnote 85 On the other hand, capturing a wider universe of adverse impacts might result in businesses not taking seriously all such impacts. Introduction of HRDD as a ‘risk assessment’ tool provides another example. While businesses are encouraged to consider risks to people (rather than risks to businesses), in practice this has led to corporations focusing mostly on risks to themselves, especially if they rely on traditional due diligence tools. Footnote 86 In other words, HRDD as a risk management tool in practice tends to be profit-driven rather than rights-driven.

The responsibility to respect human rights as well as HRDD as the main tool to discharge this responsibility applies to all business enterprises. However, it seems that the articulation of this responsibility as a social expectation in Pillar II was not assessed in relation to a range of informal economy enterprises. Ruggie admitted that ‘for small companies due diligence typically will remain informal’ under the UNGPsFootnote 87 and that the viability of HRDD process was tested mostly in relation to the practice of multinational corporations (MNCs).Footnote 88 This means that HRDD – despite its flexibility and adaptability – may not be an equally suitable tool for all types of business enterprises. For instance, the stakeholders of many of these enterprises might not think of the International Bill of Rights as a reference point to unpack their role in society, or expect them to do more than merely respect human rights.

More importantly, various Pillar II recommendations – including the four-step HRDD process – may not be practical for enterprises part of the informal economy. It is difficult to conceive how could an informal family-run snack shop in a village could meet expectations of Principle 16 of the UNGPs, that is, express its commitment to meet the responsibility to respect human rights through a statement of policy that is ‘approved at the most senior level of the business enterprise’, is ‘informed by relevant internal and/or external expertise’ and is ‘publicly available and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and other relevant parties’. Similarly, many informal business actors will not be able to relate to the HRDD process as stipulated in Principles 17–21 of the UNGPs. The problem is that since Pillar II is primarily built on the experiences of MNCs and their value chain management expectations, HRDD as the proposed solution to corporate governance challenges is not representative of a wide variety of experiences of different types of business enterprises.

Taking a cue from the fact that ‘[s]eparate legal personality is rarely invoked in relation to enterprise risk management’,Footnote 89 Ruggie proposed (and would have hoped) that HRDD could similarly be operationalized across corporate groups without going into technical legal distinctions of corporations of a group being separate legal persons. In practice however, different subsidiaries in a corporate group may have different decision-making structures, commercial priorities, stakeholder demands and domestic legal regulations shaping the practice of HRDD. Considering that each business enterprise has an independent responsibility to conduct HRDD, in a given situation there could be overlapping HRDD processes done by a parent corporation, its subsidiary and the supplier engaged by the subsidiary about the same factual matrix. These multiple HRDD processes might result in divergent remedial responses to prevent, mitigate or account for actual and potential human rights abuses.Footnote 90

4.3 Structural limitations

HRDD also suffers from certain structural limitations in that this tool may not be able to dismantle business models of irresponsibility or to bring systemic changes to the current model of economic production. The main reason for this seems to be that the UNGPs do not challenge or confront the existing structure of irresponsibility and inequality utilized by businesses to their advantage. Rather, they consciously work around (or ‘put under the carpet’) difficult or contentious issues. Footnote 91 Although there may be legitimate reasons for taking this approach grounded in ‘principled pragmatism’, some of the existing as well as future challenges in the BHR field might not be overcome without disrupting current structures employed by businesses to entrench irresponsibility and inequality.

Businesses are good at turning models of innovation into models of irresponsibility. Footnote 92 It is well-documented how parent corporations have employed their relation with subsidiaries to deny, delay or altogether avoid responsibility for human rights abuses.Footnote 93 While no efficient approach was yet found to hold parent corporations accountable in an effective manner, Footnote 94 corporations started using global supply chains to outsource their risks and responsibilities to independent contractors spread across the globe. The creation and usage of gig platforms is taking the distancing of responsibility to the next level. In future, automation of manufacturing may pose newer challenges. Although automation might eliminate forced and child labour from manufacturing, there might be no jobs for many – consequently, individuals would have the right to work and the availability of decent work standards, but no work in practice.

The UNGPs’ response to all these business models has been to recommend that all business enterprises conduct ongoing HRDD to ‘identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address their adverse human rights impacts’. Footnote 95 This means that there are hardly any ‘red lines’: all business models and all business practices are acceptable as long as a HRDD process – relational to an enterprise’s size, sector, operational context, and severity of risks to human rights – is in place. The UNGPs do not ask whether it is even practicable to respect human rights within certain business models Footnote 96 or in certain situations and places. The case of gig economy workers illustrates this. Even if HRDD conducted by a gig platform corporation finds concerns about workers’ rights, those are likely to be addressed within an inherently exploitative business model which seeks to turn employees into autonomous entrepreneurs to maximize profits. Similarly, it is doubtful whether corporations producing products like tobacco could ever respect all human rights. Footnote 97 In relation to climate change, similar concerns could be raised about the business model of fossil fuel corporations.

Moreover, there may be situations in which it may not even be feasible to conduct meaningful HRDD or human rights abuses may occur despite conducting HRDD.Footnote 98 For instance, businesses with operations in the Xinjiang province of China may lack the ability to conduct independent HRDD or even do meaningful consultation with all relevant stakeholders to address serious allegations of human rights abuses involving Uyghurs. Footnote 99 Business operations in Myanmar after the 2021 coup pose similar challenges.Footnote 100 In situations like these, businesses may not even be able to exercise or increase their leverage to make a positive change in the human rights situation on the ground. In short, HRDD may not really assist businesses to identify, prevent and mitigate adverse human rights impacts in such situations and circumstances.

Supply chains pose serious challenges for MNCs even when not operating in complex environments. Let us take supply chains of major MNCs like Nestlé as an example. Nestlé has 165,000 suppliers and 695,000 farmers. Footnote 101 In such a scenario, one might wonder whether this model of multi-tiered global sourcing linked to a big brand in itself is problematic. Conducting ongoing HRDD without any limits on the numbers of tiers in an effective manner should be highly cumbersome, time-consuming and expansive for Nestlé or any other similarly-placed MNC. Footnote 102 Is it even possible to have complex global supply chains free from human rights abuses or will doing so undercut one key purpose (economic efficiency) of having such supply chains in the first place? Moreover, while global supply chains may create jobs in developing countries, they also entrench inequality in incomes, contribute to environmental pollution, or promote unsustainable consumption practices.Footnote 103 In this context, one should consider whether a better and more sustainable business model will be to have smaller corporations sourcing locally and seasonally.

There are also other structural problems with the current economic order. The extent and levels of economic inequality in today’s world is staggering. In 2008, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found evidence that ‘[i]nequality of incomes was higher in most OECD countries in the mid-2000s than in the mid-1980s’. Footnote 104 More recently, Oxfam estimated that the ‘world’s richest 1% have more than twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people’. Footnote 105 The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed or exacerbated the existing inequality: the ‘pandemic has hurt people living in poverty far harder than the rich, and has had particularly severe impacts on women, Black people, Afro-descendants, Indigenous Peoples, and historically marginalized and oppressed communities around the world’. Footnote 106

However, like poverty, inequality is not an accident. Footnote 107 Piketty unpacks politics and ideology leading to current levels of inequality. Footnote 108 Businesses actively lobby for low tax rates, minimum state regulation, diluted labour laws (including a limited role of trade unions), creation of special economic zones, and faster environmental clearance of projects. They also consciously innovate to create exploitative business models that limit risks and increase rewards. Moreover, businesses encourage states to negotiate trade and investment agreements not only to entrench their rights in such agreements but also create a system of ‘privileged justice’ in the form of investor-state dispute settlement. All these steps taken together create, sustain or exacerbate economic inequality at different levels in society.

In other words, even if ‘respecting rights [becomes] an integral part of business’ Footnote 109 by conducting regular HRDD, economic inequality may still remain. Is it then the limit of human rights to address economic inequality? Footnote 110 Or is it more to do with how we have employed and interpreted human rights in relation to business? I will argue that HRDD under the UNGPs provides businesses a tool to make some changes to their business models but only so much to sustain the current economic order by masking its structural and systemic problems. That means that HRDD could coexist with significant levels of economic inequality in a system in which the Chief Executive Officers of MNCs continue to earn more than 350 times the average salary of their typical workers.Footnote 111 In his remarks delivered at the 2008 World Economic Forum, Bill Gates lamented the fact that the ‘great advances in the world have often aggravated the inequalities in the world. The least needy see the most improvement, and the most needy see the least’. Footnote 112 Gates himself benefitted from the current economic system which is designed to create such level of inequalities. Therefore, a more fundamental question should be asked: will HRDD be able to address fundamental flaws in the current economic system which allows some to accumulate so much wealth in the first place? Or will HRRD be employed to sustain the current system by making superficial adjustments and masking deep-rooted problems?

5. Preconditions for effective mandatory human rights due diligence laws

There is a vital distinction between HRDD as a process in identifying business-related human rights abuses and the outcome it seeks to achieve in terms of preventing or mitigating such abuses. Due to this distinction, one should not confuse making obligatory the process (HRDD) with making the outcome (the responsibility to respect human rights) obligatory. Mandatory HRDD laws are only focusing on the former. Moreover, these laws may not be able to address all the conceptual, operational and structural limitations of HRDD highlighted in Section 4. In other words, mandatory HRDD laws should not be seen as a panacea.

Yet, if designed appropriately, such laws could play a key role in encouraging businesses to take seriously their human rights responsibilities. HRDD laws – in order to be able to make a real difference to people and the planet – should not merely seek to convert currently voluntary HRDD under Pillar II of the UNGPs into a mandatory requirement for all or certain types of businesses.Footnote 113 Rather, these laws should also try to address other limitations of HRDD as discussed above. This will be possible only if the mandatory HRDD laws satisfy the following six conditions at a minimum: require holistic HRDD, capture as many businesses as much as feasible, address power imbalances, go beyond process, draw certain ‘red lines’ and provide for effective access to remedy.

These six conditions are derived from the critique of HRDD as a concept, various vulnerabilities and power imbalances experienced by rightsholders, and the ability of mandatory HRDD laws to address systemic challenges inherent in the free market economy.Footnote 114 For example, if mandatory HRDD laws only applied to a small number of corporations or focused only on certain human rights, this will leave many rightsholders vulnerable to corporate abuses. Similarly, to ensure that HRDD has an intended effect for rightsholders, the new generation of mandatory HRDD laws should insist on achieving outcomes (at least in certain situations or circumstances) and have stronger provisions for access to remedy.

-

1. Require holistic HRDD: Although there are close connections between human rights and the environment and climate change,Footnote 115 there are separate international norms governing these areasFootnote 116 and the Pillar II of the UNGPs also does not expressly include environmental rights or climate change. Therefore, mandatory HRDD laws should explicitly require businesses to conduct holistic HRDD,Footnote 117 encompassing adverse impacts on human rights, labour rights, environmental rights and climate change. For this reason, any law which focuses only on selected human or labour rights will be problematic. Equally concerning will be to delink environmental rights and climate change from human rights, because doing so will make it difficult for corporations to manage their human rights risks.

-

2. Capture as many businesses as much as feasible: Due to interconnected economies and global supply chains, human rights abuses related to a business many unfold in almost any part of the world. Mandatory HRDD laws should therefore capture both inward and outward abuses, including those related to global supply chains. At the same time, conducting mandatory HRDD regularly may not be practical at this stage for many small and medium size enterprises or enterprises which are part of the informal economy. Some careful cost-benefit calibration may therefore be required. States may, for example, encourage all but require only certain business enterprises to conduct mandatory HRDD. On the other hand, in selected high-risk sectors or settings, all businesses may be required to conduct HRDD. Moreover, states should create incentives in the form of public procurement, tax rebates, preferential loans and responsible labelling for businesses doing HRDD properly.

-

3. Address power imbalances: HRDD under Pillar II of the UNGPs remains a business-centric process. This is so despite HRDD being about managing risks to people (and not merely to businesses)Footnote 118 and having a requirement for ‘meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders’.Footnote 119 The reason is HRDD is done in practice by businesses or by consultants hired by businesses, with potentially affected people only having a passive role of being consulted. Moreover, there is not much quality control or oversight on the part of state agencies. The result is an imbalance in power, information, resources and bargaining position enjoyed by businesses vis-à-vis affected individuals and communities. Mandatory HRDD laws should try to address this asymmetrical power dynamics to ensure that HRDD does not end up becoming a tokenistic or tick-box exercise.Footnote 120 They may do so, for example, by requiring enterprises to ensure effective participation of – not merely consultation with – independent trade unions and CSOs at all stages of the HRDD process. Contemplating a proactive role for state agencies to exercise oversight over HRDD could be another tool to address asymmetries.Footnote 121

-

4. Go beyond process: As noted above, HRDD is merely a process which may or may not achieve the expected outcome, the non-infringement of human rights. Landau argues against presuming ‘that the widespread institutionalisation of the concept will necessarily translate into significant improvements in corporate respect for human rights’.Footnote 122 This translation may not happen due to various reasons. Muchlinski, for example, points out that ‘unless a corporate culture of concern for human rights is instilled into the officers, agents and employees of the company due diligence could end up missing the very issues it is set up to discover’.Footnote 123 Therefore, mandatory HRDD laws should not focus merely on requiring business enterprises to conduct HRDD. Rather, they should also expect businesses to accomplish outcomes in certain situations, otherwise face legal liability. In this context, the distinction between adverse human rights impacts linked to a business’s ‘own’ actions or omissions and impacts linked to the conduct of business partners should become critical.Footnote 124 For the former set of situations, mandatory HRDD laws should require a standard of result rather than merely a standard of conduct.

-

5. Draw certain red lines: Even if businesses conduct HRDD in line with the UNGPs, they may not be able to respect ‘all’ internationally recognized human rights in certain situations, circumstances or settings. Even heightened or enhanced HRDDFootnote 125 may not be much useful in certain complex environments. Nor would there be a realistic chance of businesses able to exercise or increase leverage over the relevant actors in these environments. It is in this context that mandatory HRDD laws – and/or relevant laws and regulations – should start drawing certain context-specific ‘red lines’: that is, specific situations, circumstances or settings in which it may not be realistic to respect all human rights. Hence, not conducting certain business activities, not entering certain markets from the outset or disengaging responsibly should be the way forward. Similarly, certain products should fall foul of the red line approach. Tobacco products is a case in point, as tobacco corporations could never fully respect ‘all’ human rights. We should see the New Zealand’s government proposal to ban cigarettes for future generations – that is, prohibiting anyone born after 2008 to buy cigarettes – in this light.Footnote 126 In order to combat climate change effectively, states may need to draw a similar red line for fossil fuel corporations. In the absence of such red lines, corporations manufacturing and selling inherently harmful products may continue to trample basis human rights by creating an impression of mitigating risks, e.g., promoting the use of e-cigarettes as less harmful than normal cigarettes.Footnote 127

-

6. Provide for effective access to remedy: Remediation is not part of the four-step HRDD process, but a vital element of the business responsibility to respect human rights under Pillar II.Footnote 128 Therefore, mandatory HRDD laws should contain adequate provisions to enable access to effective remedy if covered businesses did not conduct HRDD, did it improperly, or human rights abuses occurred despite HRDD. A ‘bouquet of remedies’ with preventive, redressive and deterrent elements should ideally be available for efficacy purposes.Footnote 129 For these reasons, mandatory HRDD laws should provide for civil, administrative and criminal remedies as they serve different but complementary purposes. They should also include ways to overcome barriers to access to remedy faced by affected individuals and communities in holding businesses accountable. In short, in the absence of strong access to remedy provisions, mandatory HRDD laws may create incentives for businesses to indulge in tick-box compliance.

6. Mandatory HRDD laws in Europe: A half-hearted attempt?

This section will analyse the extent to which mandatory HRDD laws enacted so far in Europe – that is, in France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway and Germany – satisfy six preconditions articulated above: ambit, reach, asymmetries, outcomes, red lines and access to remedy.

6.1 French law

The French law imposes an

obligation of vigilance (devoir de vigilance) on companies incorporated or registered in France for two consecutive fiscal years that either employ at least 5,000 people themselves and through their French subsidiaries, or employ at least 10,000 people themselves and through their subsidiaries located in France and abroad.Footnote 130

The covered corporationsFootnote 131 should elaborate, disclose and implement a vigilance plan that should cover risks and serious harms linked to a corporation, its controlled subsidiaries, and suppliers with which the corporation maintains an established commercial relationship.Footnote 132 The plan shall include ‘reasonable vigilance measures to adequately identify risks and prevent serious violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms, risks and serious harms to health and safety and the environment’.Footnote 133 In other words, while reach of the French law is limited to large corporations and their business partners, its ambit is quite wide covering risks not only to human rights but also to occupational health and safety well as the environment.

The vigilance plan, which may be drafted in association with the relevant stakeholders or within multiparty initiatives, shall include the following five measures: a mapping that identifies, analyses and ranks risks; procedures to regularly assess the situation of subsidiaries and suppliers; appropriate action to mitigate risks or prevent serious violations; an alert mechanism that collects reporting of existing or actual risks, developed in partnership with the trade unions; and a monitoring scheme to follow up on the measures implemented and assess their efficiency.Footnote 134 These measures of the vigilance plan are broadly comparable to the four-step HRDD process under the UNGPs.

In terms of enforcement and access to remedy, French law provides for two pathways: any interested party can seek (i) an injunction from the court to order the corporation to comply with the law; and (ii) damages for the corporation’s failure to comply with its vigilance obligation causing a preventable harm.Footnote 135 However, the burden of proof under French law is still on the claimants ‘to prove a fault by the company and a causal link between the fault and the damage they have suffered’.Footnote 136 Moreover, the law merely imposes an obligation of process and not of results.Footnote 137 Therefore, ensuring compliance with the vigilance obligation or holding corporations accountable for breach of this obligation may still be a challenge.Footnote 138 This is partly because the law does not insist on corporations achieving certain outcomes. Not does it draw any red line or try to address the asymmetries in power, information and resources between MNCs and the affected rightsholders.

6.2 Dutch law

The Dutch law is intended to address child labour in supply chains of enterprises selling or supplying goods or services to the end users in the Netherlands.Footnote 139 Section 2 of the law defines ‘child labour’ in line with international standards: the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention 1999 and the Minimum Age Convention 1973. Although this law is narrow in ambit (i.e., only focuses on child labour), its reach is very extensive in that it applies to all business enterprises selling or supplying goods or services to the end-users in the Netherlands.Footnote 140 It is also worth noting that the Dutch government has recently announced its intention to enact a comprehensive mandatory HRDD law.Footnote 141

The law requires all covered enterprises to adopt and implement a HRDD plan if there is a ‘reasonable suspicion’ that the supplied goods or services have been produced using child labour.Footnote 142 It makes a reference to ‘ILO-IOE Child Labor Guidance Tool for Business’, which is developed in line with the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines. The law also requires the enterprises to make a declaration to the superintendent that they exercise HRDD.Footnote 143

In terms of enforcement of the law and access to remedy, the superintendent has been charged with the supervision of compliance with the provisions of the law: any natural person or legal entity whose interests are affected by the conduct of an enterprise relating to compliance with the provisions of this law may submit a complaint to the superintendent.Footnote 144 However, a complaint can only be dealt with by the superintendent ‘after it has been dealt with by the company, or six months after the submission of the complaint to the company without it having been addressed’.Footnote 145 The superintendent may impose an administrative fine for breach of HRDD or reporting obligation under the Dutch law.Footnote 146 The fine can be up to €8,200 for not submitting the declaration, whereas the fine can be up to ten per cent of the worldwide annual turnover of the enterprise for failing to carry out HRDD.Footnote 147 Section 9 of the law also contemplates a criminal liability:

a director may … be imprisoned for up to two years if, in the prior five years, a fine previously had been imposed for violating the same requirement of the Act and the new violation is committed under the order or de facto leadership of the same director.Footnote 148

The Dutch law contains no provisions to draw any red lines or strict liability even regarding child labour; it focuses on obligating enterprises to follow a process. Nor is there any provision to address asymmetries: in fact, the impacted individuals or entities are first required to approach the enterprise in question to resolve their grievances before lodging a complaint with the government regulator.

6.3 Swiss law

The Swiss law introduces two new obligations.Footnote 149 First, selected large Swiss corporations (those with at least 500 employees and a minimum turnover of CHF20 million, or a minimum turnover of CHF40 million) are required to report on ‘environmental, social and labour-related issues as well as on human rights and measures against corruption’.Footnote 150 Second, corporations with their registered office, central administration or principal place of business in Switzerland are required to conduct HRDD in two situations: (i) if they import or process above a certain threshold ‘minerals or metals in Switzerland, containing tin, tantalum, tungsten or gold originating from conflict-affected and high-risk areas’; (ii) if they sell goods or services in Switzerland with ‘reasonable grounds to suspect that they were produced with child labour’.Footnote 151

It is thus clear that the scope of the Swiss law’s HRDD obligation is quite narrow both in terms of its ambit and reach: leaving aside potential situations of child labour,Footnote 152 corporations are required to conduct HRDD only if they import or process conflict minerals above a certain threshold. The law is also weak on the question of enforcement of these obligations and the related issues of access to remedy and corporate accountability. A breach of these twin obligation can only result in a criminal fine of up to CHF100,000.Footnote 153 In comparison, the Swiss Responsible Business Initiative – which was narrowly rejected in a public vote – had envisaged stronger HRDD and corporate liability provisions.Footnote 154 The Swiss law contains no provisions to draw red lines or bridge asymmetries in power.

6.4 Norwegian law

The Norwegian law seeks to ‘promote enterprises’ respect for fundamental human rights and decent working conditions’ concerning the production of goods and the offering of services.Footnote 155 It also aims to ‘ensure the general public access to information regarding how enterprises address adverse impacts on fundamental human rights and decent working conditions’.Footnote 156 The definition of ‘fundamental human rights’ is comparable to how the UNGPs define ‘internationally recognised human rights’. Section 3(b) provides that ‘decent working conditions’ means work that safeguards fundamental human rights as well as ‘health, safety and environment in the workplace’ and ‘provides a living wage’. By expressly including a living (not minimum) wage as part of decent work, the Norwegian law sets a higher expectation for businesses, which is line with a public commitment made by certain MNCs.Footnote 157 At the same time, the law does not explicitly contemplate HRDD in relation to the environment or climate change.Footnote 158

The law applies to larger business enterprises that are resident in Norway and offer goods and services in or outside Norway, as well as to larger foreign enterprises that offer goods and services in Norway and are liable to pay tax to Norway.Footnote 159 Section 3 of the law provides that larger enterprises means ‘enterprises that are covered by Section 1-5 of the Accounting Act’ or which satisfies two of the following three conditions: sales revenues of NOK70 million, balance sheet total of NOK35 million, and average number of employees in the financial year is 50 full-time equivalent. ‘It is estimated that the law will apply to about 8,830 enterprises.’Footnote 160 As parent corporations shall be considered larger enterprises ‘if the conditions are met for the parent company and subsidiaries as a whole’,Footnote 161 the Norwegian law follows the enterprise principle to satisfy the threshold of law’s application. However, it is unclear whether the enterprise principle will also be available to hold parent corporations liable for abuses of their subsidiaries.

In terms of obligations, Section 4 of the Norwegian law requires all covered enterprises to ‘carry out due diligence in accordance with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises’. Because of the alignment of the OECD Guidelines with the UNGPs, HRDD steps proposed by this provision are very similar to the four-steps process outlined in the UNGPs. Moreover, embedding responsible business conduct into the enterprise’s policies as well as providing for or co-operating ‘in remediation and compensation where this is required’ have been included as part of this HRDD obligation. Furthermore, the enterprises are obligated to publish an easily accessible ‘account of due diligence pursuant to Section 4’.Footnote 162 The HRDD obligation under ‘the Norwegian Act extends to the operations of the enterprise, supply chains and business partners’.Footnote 163

A unique aspect of the Norwegian law is the right to information under Section 6: ‘any person has the right to information from an enterprise regarding how the enterprise addresses actual and potential adverse impacts pursuant to Section 4’. The information sought under this provision could be general in nature or be related a specific product or service offered by the enterprise. This provision provides a potential tool for affected individuals and communities to seeks relevant information in a time-bound manner and in turn address partially the informational asymmetry that exits between businesses and rightsholders. It is, however, unclear how such a pathway would be accessible to the affected rightsholders abroad and to what extent the enterprises will disclose in good faith the requested information.

In terms of access to remedy and corporate accountability, the Consumer Authority may issue prohibitions and orders to ensure compliance with various provisions related to HRDD and the right to information. Section 13 also provides for enforcement penalties in case of non-compliance with such orders. Beyond these administrative enforcement tools, the Norwegian law contains no express provisions for civil or criminal liability of enterprises for not conducting HRDD at all or conducting it inadequately. Nor are there any provisions concerning red lines or strict liability.

6.5 German law

The German law applies to all business enterprises which have their central administration, principal place of business, administrative headquarters or statutory seat in Germany provided they normally have at least 3,000 employees.Footnote 164 It also applies to foreign corporations with a domestic branch if they normally have 3,000 employees. It is estimated that ‘the law will apply to approximately 900 companies from 1 January 2023 and to approximately 4,800 companies from 1 January 2024’.Footnote 165 In terms of the ambit, the law captures risks to international human rights, labour rights and the environment.Footnote 166

The covered enterprises are required to conduct HRDD in relation to risks concerning all listed international human rights and environmental rights.Footnote 167 Section 3 provides an inclusive list of HRDD steps, which are mostly in line with the UNGPs and are further elaborated by Sections 4–7 and 10. The HRDD obligations extend to enterprises’ own activities as well as the activities of their direct and indirect suppliers necessary to product or provide services. The covered enterprises are expected to conduct HRDD in an ‘appropriate manner’ which is determined based on the nature and extent of their activities, their ability to influence the conduct of their business partners, the severity of the violation, and the nature of the causal contribution of the enterprise.Footnote 168

In terms of access to remedy, the German law requires the covered enterprises to put in place an ‘appropriate internal complaints procedure’ to enable affected rightsholders to report risks and violations linked to their business activities as well as of their direct suppliers.Footnote 169 The law also provides for financial penalty and administrative fines being imposed by the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control.Footnote 170 At the same time, Section 3(3) provides that a ‘violation of obligations under this Act does not give rise to any liability under civil law’, though civil liability arising independently of this law remain unaffected. Nor is there any provision for criminal sanctions. On the positive side, Section 22 of the German law provides that enterprises subject to administrative fines shall be excluded from the award of public contracts for a period of maximum three years.

By conferring a legal standing on domestic trade unions and NGOs to bring proceedings on behalf of affected rightsholders, the German law provides an important tool to bridge asymmetry of power between large German corporations and the victims of human rights abuses in seeking access to remedy.Footnote 171 Section 7(3) of the law expressly contemplates the possibility of terminating a business relationship in certain situations, which is an indication of the German law adopting a somewhat limited red line approach.

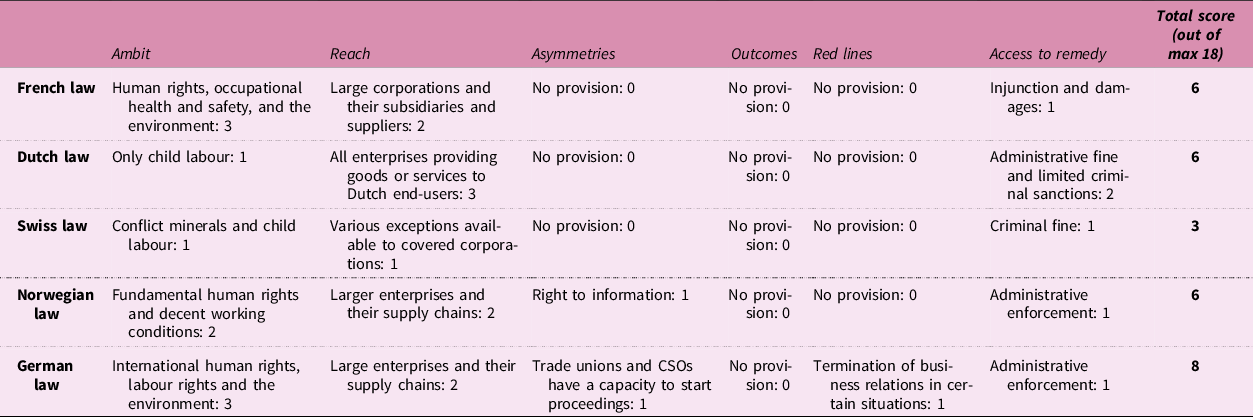

Based on the above review of the provisions of five mandatory HRDD laws in Europe, a qualitative assessment could be made vis-à-vis the identified six preconditions for a robust legislation. In Table 1 (below), the points on a scale of 0–3 are allocated as follows: 0 point for the total absence of a precondition, 1 point for low presence of a precondition, 2 points for medium presence of a precondition, and 3 points for high presence of a precondition. As per this scale, maximum possible score for any law will be eighteen points.Footnote 172 The German law scores maximum points (8/18), whereas the Swiss law scores the least number of points (3/18). The three other laws have an overall score of 6/18, though there are variations in their respective strengths and weaknesses. For example, the Dutch law is very wide in its reach, whereas the French law is quite wide in terms of its ambit.

Table 1. Qualitative assessment of five mandatory HRDD laws vis-à-vis six preconditions

It seems that it would be difficult in practice to have a law with both wide ambit and wide reach, that is, covering all human rights, labour rights and environmental rights and capturing all business enterprises and their supply chains. Out of these five laws, the German law is the most ambitious in that it has a wide scope on both counts. On the other hand, the Dutch law has a narrow ambit but very extensive reach.

None of the five laws insist on businesses achieving outcomes and hence obtain a 0 score. Rather, they focus mostly on making mandatory the process of HRDD. With the exception of the German law providing for termination of business relation in certain specific situations, rest of the laws draw no red lines, perhaps under the assumption that HRDD should be able to prevent and mitigate adverse human rights in all situations and circumstances. All laws are also quite weak – with little variations among them – on the issue of access to remedy and corporate accountability. Apart from the Dutch law scoring 2 points, rest score only 1 point (out of maximum 3 points) for the access to remedy precondition, as they do not provide for a full regime of civil, administrative and criminal liabilities. Nor these laws give adequate attention to overcoming asymmetries of power, information and resources between business enterprises and the affected rightsholders – only the German and Norwegian laws take baby steps in this direction.

7. Conclusion

In a span of just over 11 years, HRDD has become a common currency in the BHR field used by all players as a tool for business enterprises to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for adverse human rights impacts. Although not a prominent component of Pillar I, HRDD has also become a key tool employed by states to discharge their duty to protect human rights. This in itself is a significant achievement for a deeply polarized field historically.

However, as this article has tried to show, we should not accept HRDD as a panacea to either prevent human rights abuses or hold businesses accountable. In fact, because of its popularity and impressive uptake, HRDD – as part of the Pillar II of the UNGPs or of a mandatory regime at the national, regional or international level – has the potential to create a false impression of change, without making any substantial positive impact on the situation of rightsholders on the ground. I have elaborated various conceptual, operational and structural limitations of the concept of HRDD under the UNGPs. Moreover, as a critical review of five mandatory HRDD laws shows, many of these limitations will not be overcome by states simply making HRDD mandatory in line with the UNGPs.

Based on the existing practice of HRDD (including mandatory HRDD laws), one can draw at least four lessons for regulators and policy makers. First, social expectations or market forces alone will not be adequate orchestrators for businesses to take seriously their responsibility to respect human rights. Although it may sound paradoxical, the role of states as regulator, monitor, enforcer, facilitator and co-ordinator will be critical to support the operationalization of the independent responsibility of businesses to respect human rights under Pillar II of the UNGPs.

Second, a key distinction should be made between the outcome (the business responsibility to respect human rights) and the process (HRDD). The current mandatory HRDD laws are only seeking to make the latter obligatory. While this is a step in the right direction, it will not be sufficient. States and other actors should pay greater attention to achieving outcomes and this should also be reflected in their mandatory regulatory regimes.

Third, the 3.0 versionFootnote 173 of laws under Pillar I of the UNGPs, including mandatory HRDD laws, should set much more ambitious goals, some of which are articulated in the six preconditions discussed above. They should, for example, focus on addressing imbalances of power, information and resources between enterprises and rightsholders. Moreover, such laws should combine a variety of carrots and sticks. By providing for incentives for businesses taking their human rights responsibilities seriously, states should both create and facilitate proactively market rewards for responsible business conduct. In addition, there should be effective provisions for access to remedy and corporate accountability.

Fourth, the entire state-based regulatory universe should not be limited to mandatory HRDD laws. Although prevention under Pillars I and II may be ‘inextricably linked’,Footnote 174 unlike businesses’ prevention responsibility under Pillar II, states’ prevention duty under Pillar I is not mostly limited to HRDD. Rather, states should employ a range of additional regulatory tools such as obliging the adoption of a precautionary approach, establishing a strict liability regime, imposing import-export bans, drawing red lines in certain situations or addressing systemic problems with the free market economy. In other words, mandatory HRDD laws should be part of a wider regulatory menu instead of being the only item on the menu.Footnote 175