Introduction

Lichenicolous fungi in the strict sense live exclusively on lichens (Hafellner Reference Hafellner and Blanz2018). Since they are recognizable by morphological features displayed on their host, the study of lichenicolous fungi dates back to before it was understood that lichens themselves were fungal organisms. With increasing knowledge, it became clear that most lichenicolous fungi apparently occur with high specificity on their host organisms (Lawrey & Diederich Reference Lawrey and Diederich2003; Diederich et al. Reference Diederich, Lawrey and Ertz2018). The presence of lichenicolous fungi might therefore provide information about the relationships of the hosts, especially when molecular data provide limited resolution.

The common rim lichens in the genus Lecanora represent a prototype of crust-forming lichens with their apothecial ascomata, furnished in most cases by an algal-containing margin and single-celled, hyaline spores. Since the premolecular era of lichenology, studies of lichens with these characters clearly indicated that the group must be heterogenous (Hafellner Reference Hafellner1984). A high level of polyphyly was also suggested in early studies of the family Lecanoraceae (Arup & Grube Reference Arup and Grube1998), although the taxon sampling was limited at that time. More recently, the phylogenetic work of Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2016) provided new insights into the relationship of this morphological assemblage. Their study revealed that several genera, recognized by phenotypic features, such as Adelolecia, Arctopeltis, Bryonora, Carbonea, Frutidella, Lecidella, Miriquidica, Palicella, Protoparmeliopsis, Pyrrhospora and Rhizoplaca, are nested within Lecanora s. lat. Three well-supported monophyletic clades correlated also with phenotypic features: Myriolecis (including the Lecanora dispersa group and the monotypic Arctopeltis with shield-like morphology, now Polyozosia), Protoparmeliopsis (the L. muralis group), and Rhizoplaca (which includes some placodioid taxa previously classified in Lecanora). Lecidella was strongly supported as a monophyletic group while other distinct clades were not recognized at the genus level, pending further analyses of critical taxa.

One of these lineages, the Lecanora polytropa group, contains widespread species with usnic acid as the major compound and regularly accompanied by fatty acids. Motyka (Reference Motyka1996) coined the name Lecidora for this lineage, but his work is suppressed by nomenclatural measures and thus all names and combinations are invalid according to ICN Art. 34.1 (Shenzhen Code). Interestingly, Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019) left the Lecanora polytropa group untouched, while accepting Omphalodina for related species segregated from Rhizoplaca and species of lobate lecanoroid lichen assigned to Sedelnikovaea. All of these could represent a single genus, including the Lecanora polytropa group. Yakovchenko et al. (Reference Yakovchenko, Davydov, Ohmura and Printzen2019) showed that the Lecanora polytropa group is closely related to Lecanora species lacking usnic acid but instead containing pulvinic acid derivates. It may remain a matter of opinion at which level in the phylogenetic reconstruction the limits of genera should be drawn in the future. Nevertheless, the diversity of lichenicolous fungi on the Lecanora polytropa group is remarkable. A considerable number of those are restricted to Lecanora polytropa s. lat. and/or related species, which indicates a certain taxonomic distance from other lecanoroid lichenized fungi.

Arthonia is one of the genera especially rich in lichenicolous species. Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Lawrey and Ertz2018) propose 140, however, we traced c. 230 epithets of both accepted species and supposed heterotypic synonyms. Since historical times, it has been known that a considerable number of taxa are able to infest lecanoroid lichens (Almquist Reference Almquist1880). The first species recognized dates back to a time when all lichens were still classified in one genus, Lichen (i.e. Lichen varians Davies). In this particular case, the infection with a lichenicolous Arthonia has been regarded as constituting a lichen close to what is now known as the host Lecanora (Glaucomaria) rupicola (L.) Zahlbr., but with fruiting bodies of variable colour (Davies Reference Davies1794). Although subsequently recognized as a tripartite system (Nylander Reference Nylander1861), only rather recently the name was finally fixed to the organism responsible for this variation, an endohymenial species of Arthonia (Hafellner Reference Hafellner2013), for which the heterotypic synonym Arthonia glaucomaria Nyl. was in use for many decades. Some 15 Arthonia names are associated with lecanoroid hosts today. This, however, reflects only part of the extant diversity and here we describe two additional species developing on Lecanora polytropa s. lat. We compare these two species with other species on lecanoroid lichens.

Methods

For morpho-anatomical analyses, air-dried herbarium specimens from herbarium GZU were used. External morphology was studied with dissecting microscopes (WILD M3, Leica MZFl3), and anatomical studies of the thallus and ascomata were carried out using compound microscopes (Zeiss Axiophot with epifluorescence equipment, Leitz Biomed). Sectioning was performed with a freezing microtome (Leitz Kryomat; preparing sections of 12–15 mm) with squash preparations used for measurements of ascospores and conidia in particular. Preparations were mounted in water and when necessary, contrasting was performed by a pretreatment with lactic acid-cotton blue (Merck 13741). Sections and squash preparations were not pretreated with potassium hydroxide solution (K), unless otherwise stated. Measurements refer to dimensions in tap water. Only mature ascospores released from the asci were measured. Amyloidy of hymenial elements was tested by the application of iodine solution (Lugol) (Merck 9261) (I) without and with pretreatment of K. Calcofluor white (Sigma 3543) was applied as a freshly prepared 1% aqueous solution for epifluorescence microscopy.

Abbreviations for institutional herbaria follow Holmgren et al. (Reference Holmgren, Keuken and Schofield1990). Author's abbreviations are those proposed by Brummitt & Powell (Reference Brummitt and Powell1992).

Selected reference material examined

Arthonia clemens (Tul.) Th. Fr. hosts: Omphalodina chrysoleuca (Sm.) S.Y. Kondr. et al. (syn. Rhizoplaca chrysoleuca (Sm.) Zopf) (1, also host of lecto-/neotype to be designated) (apothecia), Omphalodina opiniconensis (Brodo) S.Y. Kondr. et al. (2) (apothecia). Italy: Trentino-Alto Adige: Prov. Bolzano (Südtirol), Central Alps, Ötztal Alps, Val Venosta (Vinschgau), hill S of Tárces (Tartsch) = Tartscher Bichl, NE of Glorenza (Glurns), 46°40ʹ35ʺN, 10°33ʹ40ʺE, elev. 1000 m, (1), 2002, Hafellner 61277 (GZU).—Kazakhstan: Vost Kazakhstanskaja, N of the road SE of Karatogay, 48°15ʹN, 84°36ʹE, elev. 610 m, (1), 1993, Moberg & Nordin s. n. (GZU).—Mongolia: 10 km N von Ulan-Bator, (1), 1978, Huneck MVR-16a (GZU). Umnugobi (Omnogov) Aimag: Gobi Desert, Chanchongor Somon, Central Gurvansaikhan (Gurvan-Saichan), (1), 1988, Huneck MVR 88-276a (GZU).—Russia: Siberia: Chukotka, on the upper reaches of the River Milkera, (1), 1977, Andreev s. n. (GZU).—Greenland: SW Greenland, head of Søndre Strømfjord, Ravneklippen, 67°N, 50°41ʹW, (1), 1998, Hansen (GZU).—USA: Colorado: Larimer Co., 0.8 km S of Wyoming State Line, just N of Virginia Dale, 41°N, 105°22ʹW, alt. 2256 m, (1), 1961, Shushan (GZU); Clear Creek Co., 3.8 miles E of Georgetown, 1.5 miles N of Interstate Hwy 70 near junction with Hwy 40, 39°45ʹ30ʺN, 105°39ʹ30ʺW, elev. 2500 m, (2), 1985, Ryan 20586a (GZU).

Arthonia subvarians Nyl. hosts: Lecanora (Polyozosia/Myriolecis) dispersa s. lat. (1, also host of type) (apothecia), Lecanora (Polyozosia/Myriolecis) semipallida (syn. L. flotoviana auct.) (2) (apothecia), Lecanora (Polyozosia/Myriolecis) crenulata (3) (apothecia), Lecanora (Polyozosia/Myriolecis) perpruinosa (4) (apothecia). Austria: Kärnten (Carinthia): Gailtaler Alpen, Reißkofel c. 11 km E von Kötschach-Mauthen, am Steig von der Reißkofel-Biwakschachtel entlang des W-Grates zum Gipfel, in den Nordhängen am Fuß des Gipfelaufbaus des W Vorgipfels, 46°41ʹ15ʺN, 13°08ʹ33ʺE, elev. 2190 m, GF 9344/2, (2), 2009, Hafellner 76050 & A. Hafellner (GZU). Niederösterreich (Lower Austria): Nördliche Kalkalpen, Schneeberg NW von Neunkirchen, Kaiserstein, knapp E unter dem Gipfel am Südrand der Abbrüche in die Breite Ries, 47°46ʹ25ʺN, 15°48ʹ45ʺE, elev. 2000 m, GF 8260/2, (2), 1997, Hafellner 42152 (GZU). Steiermark (Styria): [Nordalpen], Dachstein-Gruppe, Ramsau, Weg von der Dachsteinsüdwandhütte in Richtung Hunerscharte, unterhalb des Scheiblingsteins, elev. 1900–2000 m, GF 8547/2, (4), 1993, Poelt & Grube s. n. (GZU). Nördliche Kalkalpen, Mürzsteger Alpen, Veitsch Alpe, Großer Wildkamm, am SE-Grat ober der Gingatzwiese, 47°39ʹ40ʺN, 15°24ʹ30ʺE, elev. 1850 m, GF 8358/1, (1), 1997, Miadlikowska & Hafellner 40429 (GZU). [Zentralalpen], Niedere Tauern, Wölzer Tauern, Planneralpe, am Steig vom Plannerknot zum Hochrettelstein, [47°25ʹ00ʺN, 14°13ʹ28ʺE], elev. 2050 m, GF 8551/3, (3), 1985, Hafellner 14228 (GZU). Tirol (Tyrol): Osttirol, Nationalpark Hohe Tauern, Glockner-Gruppe, Teischnitztal N von Kals, untere NW-Hänge des Fiegerhorns, SW ober der Teischnitzeben, 47°02ʹN, 12°39ʹ40ʺE, c. 2200 m, GF 8941/4, (1), 1997, J. Hafellner 47134 (GZU). Vorarlberg: Rätikon, Berge W über Gargellen, kurz E unter dem St. Antönier Joch, etwas SE vom kleinen namenlosen See, 46°58ʹ00ʺN, 09°52ʹ40ʺE, elev. 2300 m, GF 9025/1, (1), 2008, Hafellner 73056 (GZU).—Italy: Trentino-Alto Adige: Prov. Trento, Südtiroler Dolomiten, Mte Castellazo N vom Passo di Rolle, S-Abhänge am Fuß der Schutthalden, 47°18ʹ20ʺN, 11°47ʹ50ʺE, elev. 2150 m, (2), 1976, Hafellner 41849 (GZU).—Switzerland: Kanton Graubünden: Engadin, Ofenpass, elev. 2300 m, (2), 1954, Schröppel s. n. (GZU). —USA: Colorado: Jefferson Co., Rocky Mountains, near mouth of Mt Vernon Canyon, near the Interstate Hwy, 39°41ʹ30ʺN, 105°12ʹ30ʺW, elev. 1950 m, (3), 1977, Anderson & Poelt s. n. (GZU).

Results

Arthonia epipolytropa Hafellner & Grube sp. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 849058

Species non lichenisata sed lichenicola. Infectio in hospiti non cecidiogena sed distincte parasitica. Ascomata humide fuscoatra ad nigra, aggregata, convexa, Ascomata ut descripta. Asci fissitunicati, octospori. Ascosporae 1-septatae, cellulis subaequalibus, (9–)10–12(–13) × 4–5 μm. Species habitu specie Arthonia subvarians similis sed ab ea differt ascomatibus in gregibus maioribus compositis et selectio hospitis. Habitat in lichene Lecanora polytropa (Hoffm.) Rabenh. praecipue supra hymenia, sed etiam in marginibus apotheciorum et areolis adhuc in regione holarctica.

Typus: Austria, Kärnten (= Carinthia), Ostalpen, Zentralalpen, Saualpe W von Wolfsberg, sanfte SE-exponierte Hänge zwischen Ladinger Spitz und Speikkogel, NE unterhalb der Wolfsberger Hütte, 46°50ʹ10ʺN, 14°39ʹ50ʺE, elev. c. 1750 m, GF 9153/4, Zwergstrauchheiden im Waldgrenzökoton, auf kleinen, losen Glimmerschieferplatten, auf Lecanora polytropa (apothecia, thallus), 24 September 2010, Hafellner 76280 (GZU—holotype; isotypes to be distributed in Lichenicolous Biota no. adhuc ined. to BR, CANB, GZU, LE, NY, UPS).

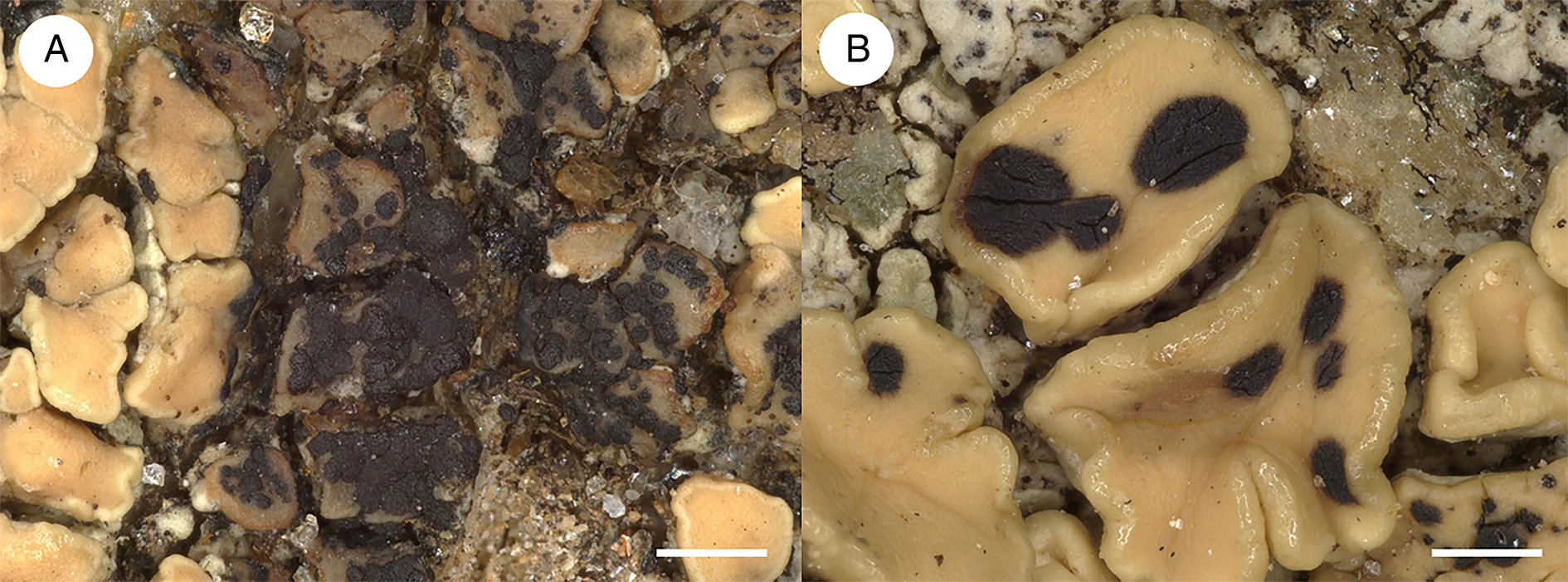

Figure 1. A, Arthonia epipolytropa (type material); habitus. B, Arthonia subclemens (type material); habitus. Scales = 0.5 mm.

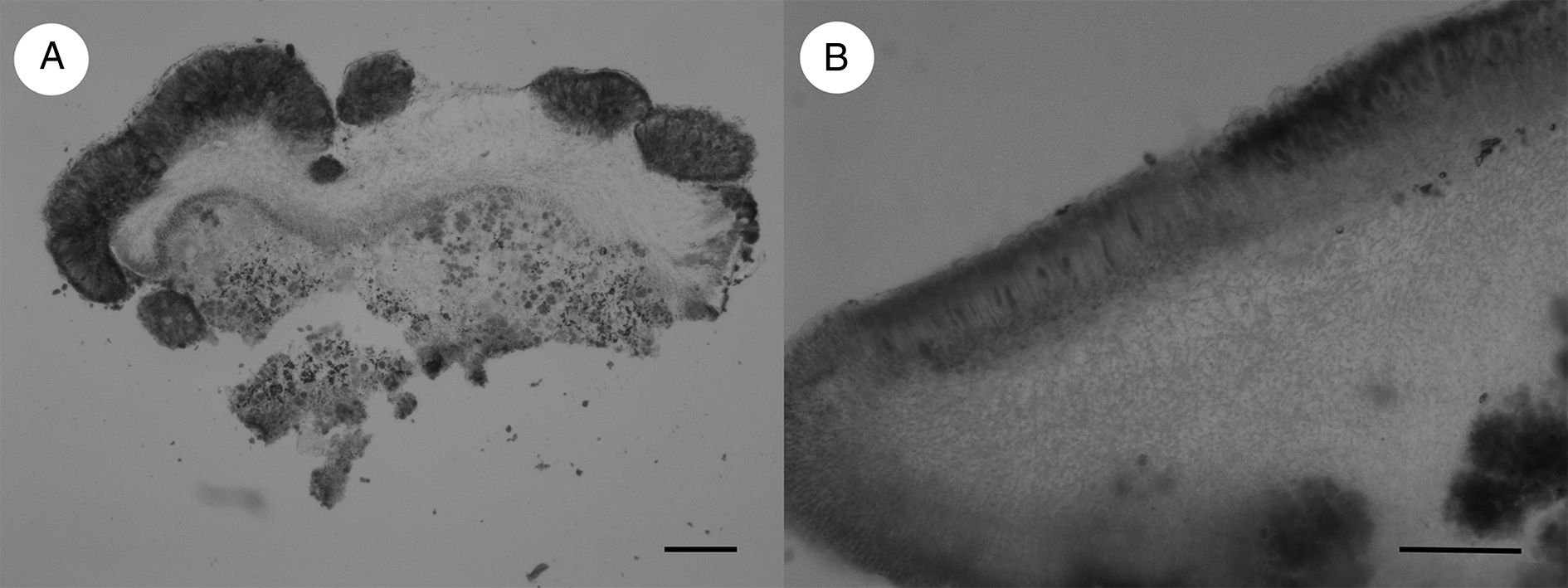

Figure 2. A, Arthonia epipolytropa (type); cross-section. B, Arthonia subclemens (type); cross-section. Scales = 100 μm.

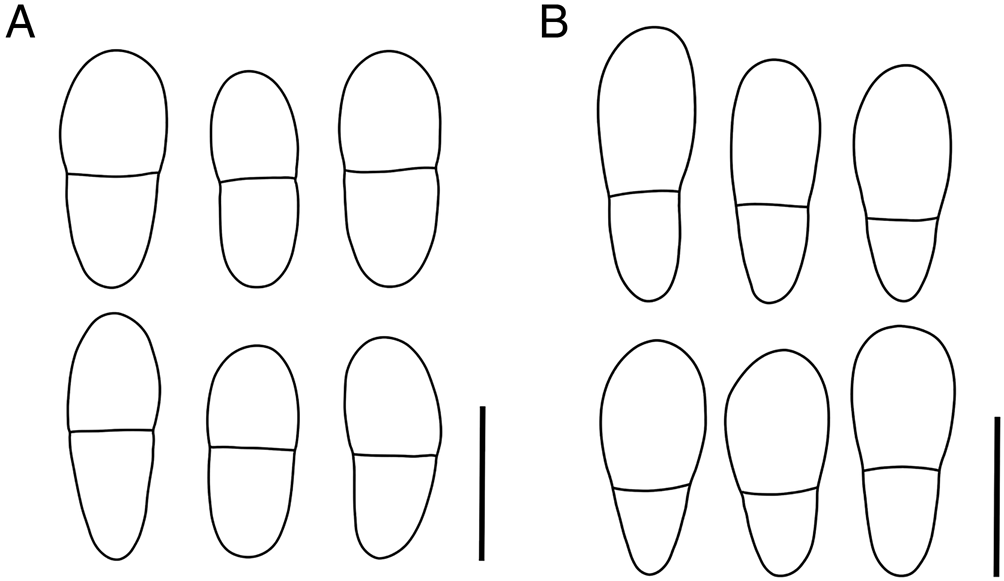

Figure 3. A, Arthonia epipolytropa (type material); ascospores. B, Arthonia subclemens (type material); ascospores. Scales = 10 μm.

Non-lichenized but lichenicolous. Infections causing bleaching spots and destroying the host apothecia, c. 0.5–1 mm diam., in dense and often agglomerated groups of c. 5 to more than 30 ascomata, these individual infections later sometimes merging into larger complexes. Development of ascomata usually starting on host apothecia, later spreading to thalline margins and occasionally also to sterile thalline areolae, here ascomata also remaining individually discernable. Vegetative hyphae imbedded in host plectenchyma, hard to detect, I−.

Ascomata black with slight brownish tinge (fresh material) to matt black, developing in upper part of hymenia of the host (several simultaneously), later on also in the phenocortex of thalline margins and areolae, appearing superficially cushion-like, and becoming crowded and confluent in progressive state of infections. Individual ascomata rounded, immarginate, in longitudinal section up to 300 μm diam. and 100–120 μm tall, except for hypothecial stipe. Hymenium 45–55 μm tall, light greyish brown, the uppermost 10–15 μm forming a brown epithecium. Hypothecium 50–70 μm tall (except for a central stipe), medium brown, when on the thallus then sometimes incorporating algae of the host. Paraphysoids branched and anastomosing, with hyphal cells 5–6 × c. 1 μm, becoming wider in the excipuloid margin (6–8 × 2–3 μm), paraphysal tips as part of the epithecium with indistinct caps and otherwise amorphous pigment, occasionally amorphous pigment dispersing in small granules, uppermost cells of epithecial hyphae c. 2 μm wide, becoming deflated and gelatinizing. Asci fissitunicate of Arthonia-type, clavate, 25–30(–35) × 10–15 μm, 8-spored, connected to ascogenous hyphae c. 4 μm wide, these distinctly fluorescent with Calcofluor white. Ascospores obovate, remaining hyaline, (9–)10–12(–13) × 4–5 μm, 1-septate, septum more or less median, upper cell slightly or hardly wider, lower cell virtually somewhat longer, not (or very indistinctly) constricted at the septum, not distinctly halonate in LM.

Pycnidia not seen.

Reactions

Hymenial and ascal gel Idil+ red, I+ red, KI+ blue, ascus with tiny KI+ blue ring basally in the tholus of the endoascus.

Etymology

The epithet is an adjective, compound of epi- (Greek = upon, over), and of the host species, on which the fungus develops.

Remarks

Concerning the apothecial characters, A. epipolytropa shows little variability. Among the Arthonia taxa invading species of Lecanora or one of its recently segregated genera, it is notable by being distinctly parasitic and discolouring the host in the infected areas, by having the largest agglomerations of ascomata, and finally by the capability to spread to thalline margins and areolae of the host. In this respect, it recalls infections of Arthonia parientinaria Hafellner & A. Fleischhacker on Xanthoria parietina (L.) Th. Fr. (Fleischhacker et al. Reference Fleischhacker, Grube, Frisch, Obermayer and Hafellner2016).

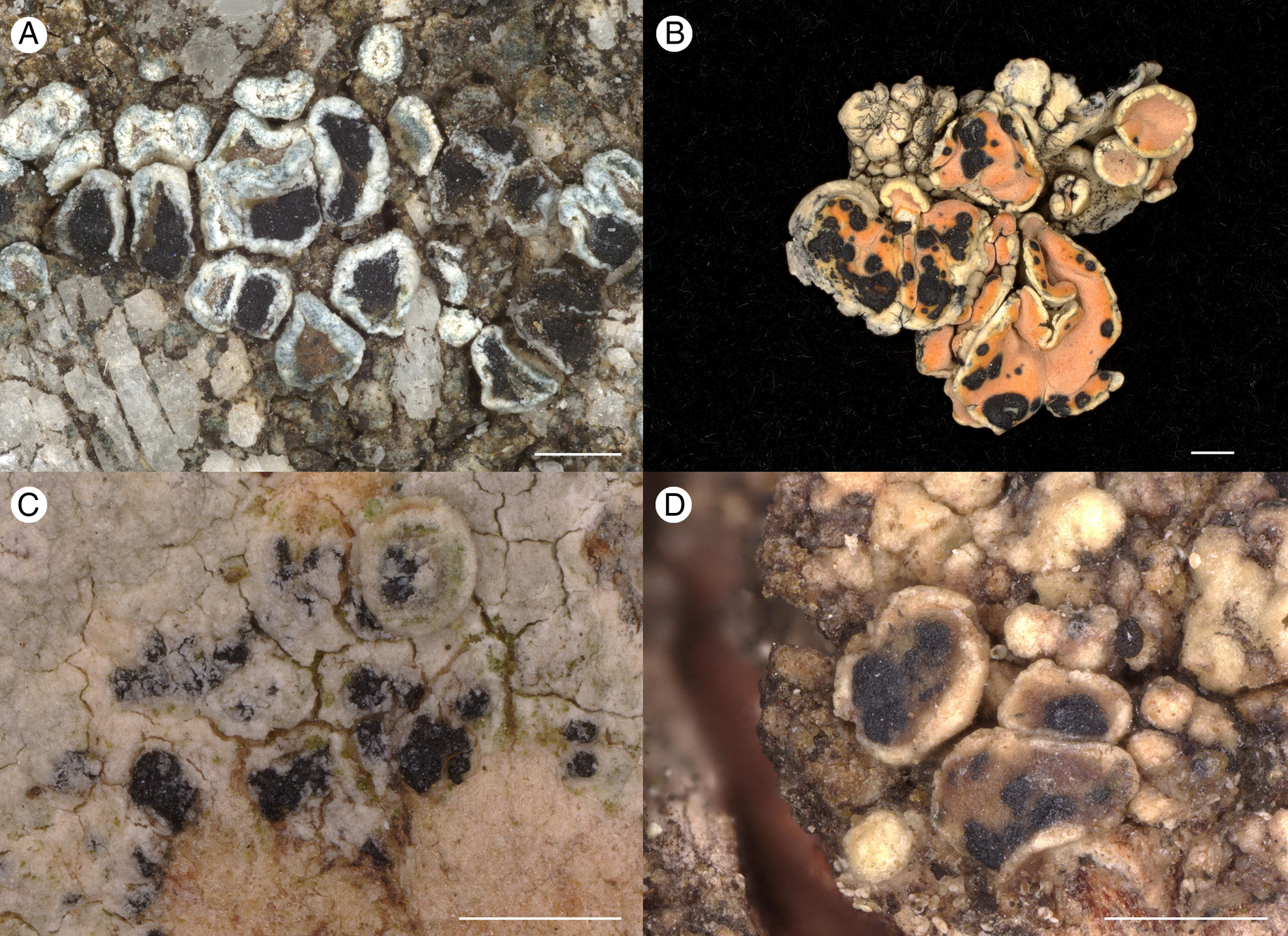

Judging from the protologue, Arthonia subvarians is not a possible name for A. epipolytropa, although this name has often been applied to it in the past (see below). Arthonia subvarians s. str. (Fig. 4A; Nylander Reference Nylander1868) is a species invading the apothecia of Lecanora dispersa (Pers.) Röhl. (in the protologue the host is named ‘Lecanora galactina var. dispersa’), hence a species considered to be a member of Polyozosia (syn. Myriolecis). Typical for that species is the presence of one to few merging ascomata restricted to the hymenia, not distinctly harming the host lichen except in the portions of the host apothecia where the ascomata develop. If Arthonia apotheciorum (A. Massal.) Almq. (type host: Lecanora (Polyozosia/Myriolecis) albescens) is proved to be a different species, Arthonia subvarians would be the correct name for this widely distributed species on various taxa of the Lecanora dispersa group (Polyozosia), replacing the so far repeatedly used heterotypic synonym Arthonia galactinaria Leight. (Leighton Reference Leighton1879).

Figure 4. A, Arthonia subvarians (Hafellner 73605); habitus. B, Arthonia clemens (Hafellner 36683); habitus. C, Arthonia subfuscicola (Hafellner 78035); habitus. D, Arthonia caerulescens (Mayrhofer 641); habitus. Scales = 0.5 mm.

Arthonia sherparum Grube & Matzer, a rarely collected species on Lecanora sherparum Poelt, differs by the distinctly convex ascomata with a dark brown hypothecium (Grube & Matzer Reference Grube and Matzer1997).

Host

Lecanora polytropa s. lat. (1) (apothecia). Lecanora polytropa in the wide sense applied here, includes a number of morphs for which sometimes specific or infraspecific names have been used (e.g. Lecanora polytropa var. alpigena (Ach.) Rabenh. incl. homotypic synonyms), and in other cases not. Recent split-offs, such as those introduced by Roux et al. (Reference Roux, Bertrand, Poumarat and Uriac2022), have also not been distinguished.

Initially, the ascomata develop in groups on/in hymenia. In older infections, the parasite frequently spreads to apothecial margins and adjacent thalline areoles.

Distribution

The species is so far known only from Europe and North America. Most specimens have been seen from higher altitudes in Central Europe (Alps). However, we also saw material from mountains in Scandinavia (Norway) and from the Balkans (Albania), as well as from the North American Rocky Mountains (USA, Wyoming). As the host lichen, if not too narrowly circumscribed, is one of the most common lichens on siliceous rocks and reported from many additional countries on other continents, it is not unlikely that A. epipolytropa will prove to be also present at least in Asia.

Previous records

Literature records applying various names and from different parts of Europe may refer to the species described here. It is probably identical with a lichenicolous Arthonia growing on Lecanora polytropa previously recorded under various names: by Arnold (Reference Arnold1873a, Reference Arnoldb, Reference Arnold1874, Reference Arnold1876a, Reference Arnoldb, Reference Arnold1878, Reference Arnold1879, Reference Arnold1893, Reference Arnold1896; sub Conida subvarians sensu auct. non Arthonia subvarians) from Austria and Italy, by Arnold (Reference Arnold1891; sub Conida apotheciorum (A. Massal.) A. Massal.) from Germany, by Kernstock (Reference Kernstock1890, Reference Kernstock1895; sub Conida subvarians (Nyl.) Arnold) from Italy, and by Lettau (Reference Lettau1958; sub Conida clemens p.p.) from Austria. More recently, we traced comparable records by Triebel & Scholz (Reference Triebel and Scholz2001; sub Arthonia subvarians p.p.) from Germany, by Brackel (Reference Brackel2013a, Reference Brackel2016; both sub A. subvarians) from Italy, by Brackel (Reference Brackel2013b; sub A. subvarians) from Switzerland, by Brackel (Reference Brackel2014; sub A. subvarians) from Germany, and by Darmostyuk (Reference Darmostuk2018; sub Arthonia subvarians) from the Ukraine.

We are not able to decide if the record by Zhurbenko & Brackel (Reference Zhurbenko2013; sub Arthonia apotheciorum (A. Massal.) Almq.) from Svalbard belongs to one of the two species described here. This is also true for an undescribed species (Arthonia polytropae ad int.) mentioned by Roux et al. (Reference Roux, Masson, Bricaud, Coste and Poumarat2011) from the Pyrenees in France. As no phenotypic characters are indicated, it remains unclear to which Arthonia species this material belongs.

Selected additional specimens examined representing paratypes (all on Lecanora polytropa s. lat.)

Albania: Northern Albania: Malësi e Madhe Distr., Bjeshkët e Nemuna (Prokletije) mountains, saddle N above the village Theth, somewhat E above the saddle, 42°26ʹ40ʺN, 19°46ʹ20ʺE, elev. 1750 m, 2007, Hafellner 80349, 80360 (GZU).—Austria: Kärnten (Carinthia): Nationalpark Hohe Tauern, Ankogel Gruppe, am Westgrat des Greilkopf E ober der Hagener Hütte, elev. 2440 m, GF 8944/4, 1994, Hafellner 33025 (GZU). Gurktaler Alpen, Felsabbrüche am Grat zwischen dem Schoberriegel und Gruft, SE der Turracherhöhe, [46°55ʹ25–36ʺN, 13°53ʹ44–59ʺE], elev. c. 2150 m, [GF 9049], 1985, Mayrhofer, Poelt s. n. et al. (GZU) [note: with Cercidospora epipolytropa as admixture]. Zentralalpen, Saualpe W von Wolfsberg, Forstalpe, Forstofen (Kote 1967) am E-Rücken, 46°53ʹ25ʺN, 14°40ʹ10ʺE, elev. 1955 m, GF 9154/1, 2011, Hafellner 78147 & Hafellner (GZU). Steirisches Randgebirge, Koralpe, Moschkogel, kurz SW vom Gipfel NE über der Grillitschhütte, 46°49ʹ25ʺN, 14°59ʹ25ʺE, elev. 1800 m, GF 9155/4, 2007, Hafellner 70177 & Muggia (GZU, UPS). Karnische Alpen, Oisternig SW von Feistritz im Gailtal, Feistritzer Alm, silikatischer Rücken N von Maria Schnee, elev. 1750 m, GF 9447/1, 1987, Hafellner 17254 (GZU). Salzburg: Lungau, Ostalpen, Niedere Tauern, Radstädter Tauern, Speiereck N über St Michael im Lungau, im unteren Teil des E-Rückens am Steig von der Bergstation der Sonnenbahn zum Gipfel, 47°07ʹ15ʺN, 13°38ʹ30ʺE, elev. 2010 m, GF 8847/4, 2019, Hafellner 86369 (GZU). Steiermark (Styria): [Nordalpen], Eisenerzer Alpen, Blaseneck N von Treglwang, kurz S unter dem E Vorgipfel, 47°29ʹ50ʺN, 14°37ʹ15ʺE, elev. 1950 m, GF 8553/2, 1997, Hafellner 45984 & Hafellner (GZU). Niedere Tauern, Wölzer Tauern, Bergkette N von Lachtal c. 9.5 km NE von Oberwölz, Schießeck, S-Rücken zwischen dem Sattel zur Rossalm und Knappenstein, 47°14ʹ58ʺN, 14°20ʹ10ʺE, elev. 2120 m, GF 8752/3, 2014, Hafellner 83160 (GZU) [note: with Cercidospora epipolytropa as admixture]. Gurktaler Alpen, Kirbisch c. 11 km SW von Murau, oberhalb von St Lorenzen, NE-exponierte Hänge knapp unter dem Gipfel, 47°03ʹ05ʺN, 14°03ʹ05ʺE, elev. 2100 m, GF 8950/1, 2003, Hafellner 62440 (GZU). Seetaler Alpen, Fuchskogel c. 9 km W von Obdach, unterste NE-Hänge, 47°03ʹ10ʺN, 14°35ʹ05ʺE, elev. 1930 m, GF 8953/2, 2013, Hafellner 82097 (GZU) [note: with Cercidospora epipolytropa and Lichenoconium lecanorae as admixture]. Steirisches Randgebirge, Stubalpe, Ameringkogel-Massiv E von Obdach, Weißenstein, S-Hänge knapp unter dem Gipfel, 47°03ʹ55ʺN, 14°48ʹ30ʺE, elev. 2100 m, GF 8954/2, 2005, Hafellner 65188 (GZU) [note: with Cercidospora epipolytropa as admixture]. Tirol (Tyrol): Samnaun-Gruppe, Furgler W ober Serfaus, am Grat zwischen dem Furgler Joch und dem Gipfel, elev. 2800–2900 m, GF 8929, 1991, Hafellner 23523 (GZU). Vorarlberg: Silvretta-Gruppe, Kl. Lobspitze SW über der Bielerhöhe, NE-Rücken über dem Silvretta-Stausee, 46°54ʹ45ʺN, 10°05ʹ30ʺE, elev. 2080 m, GF 9026/4, 2008, Hafellner 81279 (GZU).—Italy: Piemonte: Prov. Torino, Western Alps, Alpi Cozie, mountains W of Pinerolo, north-eastern slopes and ridges of the Punta Cialáncia S above Perero Village, 44°53ʹ00ʺN, 07°07ʹ20ʺE, elev. 2350 m, 2001, Hafellner 69355 (GZU). Trentino-Alto Adige: Prov. Trento, Eastern Alps, Central Alps, Ortler-group (Stelvio-group), c. 8 km N above Cógolo, La Cascata S above Lago Lungo, summit area, 46°25ʹ30ʺN, 10°41ʹ00ʺE, elev. 2575 m, 2006, Hafellner 69336 (GZU).—Norway: Oppland: Lom, Jotunheimen, Glittertind-Massiv, frische Silikatblockhalde am Ausgang des Steinbudalen, elev. 1750 m, 1984, Hafellner 12212 & Ochsenhofer (GZU).—Switzerland: Kanton Bern: Berner Alps, c. 8 km SW above Meiringen, by the road from Schwarzwaldalp to the saddle Große Scheidegg, below Alpiglen, 46°40ʹ00ʺN, 08°07ʹ10ʺE, elev. 1650 m, 2006, Hafellner 75474 (GZU). Kanton Graubünden: Urner Alps, Gotthard group, Oberalppass c. 6 km NE of Andermatt, somewhat S above the pass, 46°39ʹ20ʺN, 08°40ʹ15ʺE, elev. 2100 m, 2006, Hafellner 77331 (GZU).—USA: Wyoming: Teton Co., Yellowstone National Park, Spruce Fir Picnic Area 7 miles SW of Bridge Bay, W shore of Yellostone Lake, 44°28ʹ05ʺN, 110°28ʹ02ʺW, elev. 7750 ft, 1998, Wetmore 81660a (GZU).

Arthonia subclemens Hafellner, Grube & Muggia sp. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 849059

Species non lichenisata sed lichenicola. Infectio in hospiti non cecidiogena. Ascomata nigra, plerumque singularia aut per 1–5 in hymenio hospitis immersa, haud aggregata, plana ad subconvexa, Ascomata ut descripta. Asci fissitunicati, octospori. Ascosporae 1-septatae, 12–15(–16) × 4–5(–6) μm, septis distincte basim versus excentricis ergo cellulis inaequalibus. Species habitu specie Arthonia clemens similis sed ab ea differt ascomatibus minus convexis et ascosporis aliquot maioribus cum septis excentricis. In hymeniis lichenis Lecanora polytropa vigens adhuc solum in Europa.

Typus: Italy, Trentino-Alto Adige, South Tyrol (Südtirol), Eastern Alps, Ötztal Alps, Val Venosta (Vinschgau), mountains NE above the village Silandro (Schlanders), ridge NNE above of Schönputz, 46°39ʹ13ʺN, 10°48ʹ23ʺE, elev. c. 2370 m, siliceous outcrops and boulders in treeline ecotone, on slightly inclined rock faces, on Lecanora polytropa s. lat. (apothecia), 28 June 2016, Muggia s. n. & Ametrano (GZU—holotype; isotypes to be distributed in Lichenicolous Biota no. adhuc ined. to BR, CANB, GZU, NY, TSB, UPS).

Non-lichenized but lichenicolous. Infections not distinctly parasitic except in well-defined areas on the host apothecia. Vegetative hyphae imbedded in host apothecia, hard to detect, I−. Forming one or few ascomata per apothecium of the host.

Ascomata conspicuous, visible as pure black (somewhat paler at the margins) roundish patches 0.2–0.6(–1) mm diam. on the usually yellowish discs of the host apothecia, remaining individual, rarely 1–3 merging but not agglomerating in dense groups, entirely immersed in the hymenium of the host apothecia, flat to hardly convex; when in advanced stage or dry, often showing one to few irregular fissures indicating a shrinking of the hymenial complex (Fig. 1B). Individual ascomata rounded, immarginate, in longitudinal section up to 600(–1000) μm diam. and 100–120 μm tall. Hymenium 50–60 μm tall, hyaline to pale brownish, the uppermost 15–20 μm dull brown to chestnut brown forming an epithecium, epithecial hyphae conglutinated by amorphous pigments, in between with granula of unclear origin. Hypothecium 40–50 μm tall, hyaline to pale brownish. Paraphysoids branched and anastomosing, with hyphal cells 6–8 × c. 1 μm, with slighty enlarged terminal cells. Asci fissitunicate of Arthonia-type, clavate, 30–40 × 15–18 μm, 8-spored, connected to ascogenous hyphae c. 4 μm wide, distinctly fluorescent with Calcofluor white. Ascospores obovate, remaining hyaline, 12–15(–16) × 4–5(–6) μm, 1-septate, septum closer to the lower end, upper cell distinctly wider and longer, hardly constricted at the septum, not distinctly halonate in LM.

Pycnidia not visible from the outside but in some sections detected adhering to or even embedded in ascomatal structures, subsphaerical, with brown walls. Pycnospores bacilliform, 5–6 × c. 1 μm.

Reactions

Hymenial and ascal gel Idil+ red, I+ red, KI+ blue, ascus with tiny KI+ blue ring basally in the tholus of the endoascus.

Etymology

The epithet refers to the habitually similar Arthonia clemens, a species restricted to Omphalodina.

Remarks

Concerning the apothecial characters, A. subclemens shows little varibility. Among the Arthonia taxa invading species of Lecanora s. lat. settling on acidic rocks, it is distinctive in its relatively large, plane to hardly convex, pure black ascomata, mostly 1–3(–5) per host apothecium and in the host selection. Among these taxa it is most similar to Arthonia clemens s. str. (Fig. 4B), in terms of morphology. However, this species exhibits small but distinctly convex, cushion-like ascomata, 1-septate ascospores with less excentric septa and somewhat smaller than in A. subclemens, and a host selection restricted to Omphalodina, namely its type species O. chrysoleuca (Sm.) S.Y. Kondr. This follows the commonly applied concept of Arthonia clemens, but depends on a wise type selection for Phacopsis clemens Tul., namely to a specimen from the Dauphinée in France (Tulasne Reference Tulasne1852: 125 ‘…in apotheciis cum Squamariae rubinae DC., e Delphinatus alpibus…’). This is necessary because in the protologue three different collections with three different hosts representing syntypes (but possibly belonging to three different species) are listed and the selection of a different type could destabilize the existing concepts of more than one of the lichenicolous Arthonia species. Similar in its habit is also Arthonia protoparmeliopseos Etayo & Diederich, but that species has 2–3-septate ascospores and appears to be restricted to Protoparmeliopsis muralis s. lat. (Etayo & Diederich Reference Etayo and Diederich2009). More distantly related appears to be Arthonia varians (Davies) Nyl., the ascomata of which develop in the hymenia of Lecanora rupicola and its close relatives (core group of Glaucomaria). Ascomata of Arthonia varians tend to merge and finally obtect the entire discs of the host apothecia and exhibit 3-septate ascospores. Arthonia sherparum, a rarely collected species on Lecanora sherparum, differs by the distinctly convex ascomata with a dark brown hypothecium (Grube & Matzer Reference Grube and Matzer1997).

Distribution

The species is so far known only from some scattered localities in mountain ranges of Central and Southern Europe, but we expect it to be more widely distributed.

Previous records

Earlier literature records applying various names and from different parts of Europe are evidently few. Arthonia subclemens is probably identical with a lichenicolous Arthonia on Lecanora polytropa recorded from Aragon in Spain (Etayo Reference Etayo2010: 43 ff., sub A. protoparmeliopseos p. p.) for which 1-septate ascospores with a strongly excentric septum have been reported. Whether an undescribed Arthonia species (Arthonia polytropae ad int.) mentioned by Roux et al. (Reference Roux, Masson, Bricaud, Coste and Poumarat2011) from the Pyrenees in France belongs here remains unclear, as no phenotypic characters are indicated.

Additional specimens examined representing paratypes (all on Lecanora polytropa)

Austria: Kärnten (= Carinthia): Ostalpen, Zentralalpen, Steirisches Randgebirge, Koralpe c. 10 km ESE über Wolfsberg, Sprungkogel W über der Grillitschhütte, ersten Blockwerk SW vom Gipfel, 46°48ʹ54ʺN, 14°58ʹ14ʺE, elev. 1860 m, (1), 2012, Fleischhacker 12375 & Muggia (GZU).—Greece: Epirus: Ioannina, municipality of Konitsa, northern Pindus Range, Mt Gramos massif, N above Plikati Village, on the crest next to the border with Albania, 48°19ʹ10ʺN, 20°45ʹ40ʺE, elev. 2000 m, 2014, Muggia s. n. (GZU, TSB).—North Macedonia: SE-Macedonia: Kožuf Mountain, Peak 92, 1.5 km NE of Kožuf summit, N surroundings of the meteorological station, 41°10ʹ25ʺN, 22°12ʹ59ʺE, elev. c. 2600 m, (1), 2017, Kaltenböck 405a (GZU).—Spain: Prov. Gérona: Pyrenäen, Nuria N von Ribas de Freser, NW-Hänge SE über der Bergstation der Zahnradbahn, elev. 2000–2100 m, (1), 1983, Hafellner 17632 (hb. Hafellner).

Discussion

Here we describe two new lichenicolous species of Arthonia occurring in the Lecanora polytropa group. For several reasons we refrained from using Bryostigma as a possible segregate name for the newly described species. First, after reanalyzing the type material of Bryostigma leucodontis, we confirm a relationship with Arthonia s. lat., as proposed by Coppins (Reference Coppins1989), but the phenotypic characters are not sufficiently developed to confirm a relationship with other species assigned to Bryostigma today. Notably, Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Upreti, Mishra, Nayaka, Ingl, Orlov, Kondratiuk, Lőkös, Farka and Woo2020) recombined several species in Bryostigma which did not belong to a monophyletic clade in other studies (e.g. Thiyagaraja et al. Reference Thiyagaraja, Lücking, Ertz, Wanasinghe, Karunarathna, Camporesi and Hyde2020). Despite possible taxonomic consequences, we prefer to wait until the phylogenetic concepts of lichenicolous species consolidate and the status of Bryostigma and other species groups within a wider circumscribed genus Arthonia is clarified (Sundin et al. Reference Sundin, Thor and Frisch2012; Frisch et al. Reference Frisch, Thor, Ertz and Grube2014).

Both species on Lecanora polytropa s. lat. can easily be distinguished from each other by their morphological characters. The immersed ascomata of A. subclemens possess pale to brownish hypothecia whereas the sessile ascomata of A. epipolytropa have dark hypothecia and become distinctly crowded. Furthermore, ascospore shape and size easily distinguish the two species in squash preparations or sections (see descriptions or key). Both seem to reflect two distinct growth strategies of ascomata in lichenicolous Arthonia species. One of these, A. epipolytropa, is characterized by ascomata that emerge early from the surface of the host and tend to form agglomerations of more than 10 ascomata. In later stages, the ascomata also appear on the thallus. In the second type, represented by A. subclemens, the ascomata remain more or less immersed and tightly integrated in the host hymenia where they seem to use the host structures, for example by acting as a functional unit to maintain the lateral pressure for well-functioning ascospore release. Arthonia varians, occurring on part of the Lecanora rupicola group (Glaucomaria), has a similar strategy to immerse its structures in the host apothecia, but it is easily distinguished by its 3-septate ascospores (13–18 × 4–7 μm). Smaller, 2–3-septate ascospores (10–14.5 × 4–5.5 μm) are known from Arthonia protoparmeliopseos Etayo & Diederich, which grows preferably in the ascomata of Protoparmeliopsis muralis (Schreb.) M. Choisy (Etayo & Diederich Reference Etayo and Diederich2009). An extreme outcome of this strategy has evolved by the intrahymenial parasitism of Arthonia intexta Almq., which occurs in the ascomata of Lecidella species (Hertel Reference Hertel1969). The parasitic structures are indistinct in external view because both fungal species develop merged black, slightly swollen ascomata complexes scarcely differing from healthy Lecidella fruiting bodies. Infections are usually detected in sections and are recognized under the microscope as single or few grouped asci of the parasite which are hidden and develop intermingled with hymenial elements of the host in the ascomata of the host. A closer relationship of that species with A. varians is probable judging from shared ascospore characters.

A reduction of its own ascomatal structures and integration in the host hymenia reflects evolutionary specialization of the parasites, and it also reflects a general evolutionary trajectory in the Arthoniaceae. While ascomatal excipula are present in most members of Arthoniales, Arthonia has indistinct or reduced structures to laterally delimit ascomata. Further steps to an almost complete reduction of auxiliary plectenchyma surrounding meiosporangia (asci) can be seen in the diffuse ascigerous structures in Crypothecia and related taxa (e.g. Santesson Reference Santesson1945; Thor Reference Thor1997; Wolseley & Aptroot Reference Wolseley and Aptroot2009; Bungartz et al. Reference Bungartz, Dután-Patiño and Elix2013). Many of the c. 140 parasitic species known so far in Arthonia (Diederich et al. Reference Diederich, Lawrey and Ertz2018) emerge from the upper surface of the host thallus and have hyphal structures at the lateral delimitation of the ascomata, but it seems that lecanoroid lichens are particularly suitable hosts for evolving arthonioid parasites that colonize and specialize on hymenia.

Nevertheless, species with ascomata immersed in the hymenia do not spread to thalline structures. It is still difficult to visualize the course of the parasitic hyphae, but observations of the occasionally browning hyphae of Arthonia diploiciae on thalli of Diploicia canescens (unpublished data), indicate an affinity for the algal cells of the hosts. We can only speculate whether the hymenial specialists extend their hyphae in the host thallus or have adapted to feed either on intracellular gels or plasma of thin-walled apothecial hyphae. The loss of hypothecial pigmentation appears to be a precondition for a formation of immersed intrahymenial ascomata.

Apart from the two species newly described on Lecanora polytropa, the genus Lecanora s. lat. supports a surprising diversity of Arthonia species on either thalli or ascomata. Several species appear to be restricted to epiphytic species of Lecanora agg. Arthonia subfuscicola (Linds.) Triebel occurring on Lecanora albella (Pers.) Ach. and L. carpinea (L.) Vain. differs from the newly described species by its 3-septate ascospores and occurrence mostly on thalli (Fig. 4C). The presence of the ascomata on the thallus is also characteristic for Arthonia agelastica R. C. Harris & Lendemer, a species on Lecanora louisiana B. de Lesd. Its brownish ascomata occur in groups of few to many, and they have 2(–3)-septate, halonate ascospores (13–17 × 5–7.5 μm). Arthonia caerulescens (Almq.) R. Sant. (Fig. 4D), a species with 1-septate ascospores occurring on Lecanora varia (Hoffm.) Ach., is more distinctive due to the blue-green pigments in the epithecia. Moreover, Grube & Matzer (Reference Grube and Matzer1997) observed conspicuously thick-walled ascogenous hyphae in this species. The circumscription of Arthonia lecanorina (Almqu.) R. Sant., a further didymosporous species on apothecia of Lecanora albella (Pers.) Ach. (apothecia), needs clarification.

Some other species with 1-septate spores, however, seem to be notoriously difficult to distinguish by morphological characters. From other families, we have learned that phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences suggest sufficient genetic differences between morphologically similar species on different hosts (see Fleischhacker et al. Reference Fleischhacker, Grube, Frisch, Obermayer and Hafellner2016), which supports the host-specificity of species. More generally, there is not really evident transgression of well-circumscribed Arthonia species, neither between taxonomic host species groups within Lecanora agg. nor between the main substratum types (saxicolous vs corticolous).

Particularly problematic are species on members of Polyozosia (syn. Myriolecis), which is a segregated genus name for the Lecanora dispersa group. The oldest available name for an Arthonia on Polyozosia is A. apotheciorum (A. Massal.) Almq. with P. albescens (Hoffm.) S.Y. Kondr. et al., a lowland species as the type host. If A. apotheciorum turns out to be a highly specialized species (which requires further study), Arthonia subvarians (syn. A. galactinaria Leight.) would be the correct name for the common species parasitizing the ascomata of various Polyozosia species, specifically those growing on rock in higher altitudes. Its cushion-shaped ascomata, usually 1–3 per host hymenium, have brownish olivacous pigments in the epithecium and a distinctly brownish hypothecium. However, there are also only distantly related parasites on Polyozosia species. For example, Arthonia lecanoricola Alstrup & Olech [as ‘lecanoriicola’] on ascomata of P. populicola (DC.) S.Y. Kondr. et al. which has 2(–3)-septate ascospores (11–13 × 4–4.5(–5) μm, or up to 6–6.5 μm wide in the type material); or A. oligospora Vězda on a lowland morph of P. crenulata auct., non (Ach.) S.Y. Kondr. et al. growing close to the sea which is primarily distinguished by 4-spored asci (ascospores 10–12 × 5–6 μm) and ascomata that develop on the thallus with the infection apparently spreading to intermingled Lecania nylanderiana A. Massal.

Further species on silicicolous lichens include Arthonia sherparum on apothecia of the distinctive Himalayan species Lecanora sherparum, which has distinctly convex sessile ascomata with intensely brownish pigments in the epithecium and hypothecium. Arthonia glacialis Alstrup & E. S. Hansen occurs on Rhizoplaca melanophthalma (DC.) Leuckert & Poelt where it develops large, sessile and convex ascomata with pigment caps in the epithecia and brownish hypothecia (spores 11–13 × 4.5–5.5 μm). This behaviour differs clearly from Arthonia clemens (type of Conida) forming only slightly convex semi-immersed cushions on the related host Omphalodina chrysoleuca (former Rhizoplaca chrysoleuca).

Finally, we want to return to the old, yet still interesting topic of lichen parasites as indicators of host relationships (Hafellner Reference Hafellner, Reisinger and Bresinsky1990). The host spectra of lichenicolous Arthonia species with lecanoroid lichens as hosts is a particularly interesting case. We observe that species are fairly host-specific and specialize in representatives of different groups in Lecanora s. lat. (some of which are now segregated), with some difficult to clearly delineate (e.g. those occurring on Polyozosia). However, we also demonstrate here that some Lecanora species can be colonized by clearly different species, which have close relatives on more distantly related hosts, indicating potential host jumps within Lecanoraceae. It remains to be investigated whether such host jumps could be facilitated by required parallelisms in host morphology for infection.

Recent work shows that after decades of hesitation, phenotypically circumscribed species are carved out from the Lecanora polytropa group (Śliwa & Flakus Reference Śliwa and Flakus2011; Roux et al. Reference Roux, Bertrand, Poumarat and Uriac2022), and that the diversity might be massively underestimated when molecular data are considered (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Clancy, Jensen, McMullin, Wang and Leavitt2022). As genetic diversity is high in the Lecanora polytropa group, and taxonomy now proceeds with segregating phenotypically characterized species, it will be interesting to examine whether lichenicolous Arthonia species have preferences for either certain eco-, pheno- or genotypes of their hosts.

Key to lichenicolous fungi regularly occurring on Lecanora polytropa s. lat.

Note: The cited references for each of the species refer to publications including full descriptions. Stigmidium congestum (Körb.) Triebel and Tetramelas pulverulentus (Anzi) A. Nordin & Tibell, which are both reported (Vouaux Reference Vouaux1912; Alstrup & Hawksworth Reference Alstrup and Hawksworth1990) but unlikely to occur on Lecanora polytropa, have not been included.

1 Infection inducing the formation of convex brownish swellings (i.e. basidiomata) on the host apothecia, spores produced on basidia; Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Millanes and Wedin2022) Tremella pyrenaica Diederich et al.

Infection not gall-inducing, spores not produced on basidia 2

2(1) Fructifications (conidiomata and/or ascomata) are superficial granules entirely made of spherical yeast-like cells that easily separate in squash preparations, either with asci containing hyaline, later brown 1-septate ascospores or with brown subspherical conidia composed of c. 10 spherical cells; Berger & Brackel (Reference Berger2011), Ertz et al. (Reference Ertz, Lawrey, Common and Diederich2014), occurrence on L. polytropa fide e.g. Zhurbenko & Brackel (Reference Zhurbenko2013) Lichenostigma chlaroterae (Berger & Brackel) Ertz & Diederich

Reproductive structures different 3

3(2) Spores are pigmented or hyaline ascospores 4

Spores are pigmented conidia 21

4(3) Ascomata are apothecia or apothecioid 5

Ascomata are perithecia or perithecioid 13

5(4) Ascospores brown, septate 6

Ascospores hyaline, septate or aseptate 7

6(5) Ascospores in optical section usually with 3 trans-septa and 1–2 incomplete longisepta, 17–20 × 8–10 μm; Alstrup & Hawksworth (Reference Alstrup and Hawksworth1990) Rhizocarpon destructans Alstrup

Ascospores 1-septate, 9–10 × 5–6 μm; Müller (Reference Müller (Argoviensis)1872), Vouaux (Reference Vouaux1913). Note: a poorly known species, possibly a species of Sclerococcum (Dactylospora) ‘Buellia vagans’ Müll. Arg.

7(5) Ascospores septate 8

Ascospores aseptate, asci lecanoralean, with I+ intensely blue tholus and/or apical cap 10

8(7) Ascomata deeply urceolate, in section with prominent crown of periphysoids, asci ostropalean with I− tholus, ascospores with up to 5 trans-septa, later additionally with 1–2 incomplete longisepta; Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Zhurbenko and Etayo2002) Sphaeropezia figulina (Norman) Baloch & Wedin

Ascomata different, asci arthonialean, ascospores 1-septate9

9(8) Ascomata sessile, agglomerated, ascospores (9–)10–12(–13) × 4–5 μm with submedian septum Arthonia epipolytropa Hafellner & Grube

Ascomata dispersed and sunken in hymenium of host, ascospores 12–15(–16) × 4–5(–6) μm with septum closer to the lower end, cells therefore distinctly unequal Arthonia subclemens Hafellner et al.

10(7) Ascospores 14–17 × 5–7 μm, with pointed ends; Steiner (Reference Steiner1898). Note: a poorly known species, according to Rambold & Triebel (Reference Rambold and Triebel1992) possibly a synonym of Carbonea supersparsa ‘Nesolechia’ oxysporiza J. Steiner

Ascospores shorter 11

11(10) Ascomata strongly convex, virtually immarginate, often agglomerated, ascospores 9.5–12 × 3–4 μm; Vouaux (Reference Vouaux1913), Cannon et al. (Reference Cannon, Malíček, Ivanovich, Printzen, Aptroot, Coppins, Sanderson, Simkin and Yahr2022) Carbonea aggregantula (Müll. Arg.) Diederich & Triebel

Ascomata flat, distinctly marginate 12

12(11) Epihymenium in longitudinal section bluish to blue-green, ascospores 8.5–13 × 4.5–7 μm; Vouaux (Reference Vouaux1913), Cannon et al. (Reference Cannon, Malíček, Ivanovich, Printzen, Aptroot, Coppins, Sanderson, Simkin and Yahr2022) Carbonea supersparsa (Nyl.) Hertel

Epihymenium sec. protologue colourless, ascospores 9–9.5 × 5–5.5 μm; Alstrup & Hawksworth (Reference Alstrup and Hawksworth1990). Note: a poorly known species, according to Rambold & Triebel (Reference Rambold and Triebel1992) a synonym of Carbonea supersparsa ‘Lecidea’ diexcipula D. Hawksw. & Alstrup

13(4) Ascospores hyaline, septate 14

Ascospores pigmented, aseptate or septate 17

14(13) Ascospores with up to 5 trans-septa, later additionally with 1–2 incomplete longi-septa, the virtually perithecioid ascomata are urceolate apothecia; Diederich et al. (Reference Diederich, Zhurbenko and Etayo2002) Sphaeropezia figulina (Norman) Baloch & Wedin

Ascospores 1-septate 15

15(14) Mature ascomata without interascal filaments, exciple in longitudinal section brown throughout; Roux & Triebel (Reference Roux and Triebel1994) Stigmidium squamariae (de Lesd.) Cl. Roux & Triebel

Ascomata with persistent interascal filaments, exciple in longitudianal section with pigment in shades of blue 16

16(15) Asci predominantly 8-spored; Calatayud et al. (Reference Calatayud, Navarro-Rosinés and Hafellner2013) Cercidospora epipolytropa (Mudd) Arnold

Asci predominantly 4-spored; Calatayud et al. (Reference Calatayud, Navarro-Rosinés and Hafellner2013) Cercidospora stenotropae Nav.-Ros. & Hafellner ad int.

17(13) Ascospores aseptate, asci 4-spored, interascal filaments persistent; Brackel (Reference Brackel2021) Roselliniella silvae-gabretae Brackel

Ascospores septate18

18(17) Ascospores 1-septate, interascal filaments in mature ascomata indistinct 19

Ascospores with more than 1 trans-septa, interascal filaments in mature ascomata distinct or indistinct 20

19(18) Asci multi-spored; Triebel (Reference Triebel1989), occurrence on L. polytropa fide e.g. Triebel (Reference Triebel1989) Muellerella pygmaea (Körb.) D. Hawksw. var. athallina agg.

Asci with 8 spores; Triebel (Reference Triebel1989), occurrence on L. polytropa fide e.g. Brackel & Wirth (Reference Brackel and Wirth2023) Endococcus brachysporus (Zopf) M. Brand & Diederich agg.

20(18) Interascal filaments lacking; Pérez-Ortega & Halıcı (Reference Pérez-Ortega and Halıcı2008). Lasiosphaeriopsis lecanorae Pérez-Ortega & Halıcı

Interascal filaments persistent; Navarro-Rosinés & Roux (Reference Navarro-Rosinés, Roux, Nash TH, Gries and Bungartz2008), occurrence on L. polytropa fide e.g. Brackel (Reference Brackel2014) Pyrenidium actinellum Nyl. agg.

21(3) Conidia developing on endohymenial conidiophores; Hawksworth (Reference Hawksworth1979), occurrence on Lecanora polytropa fide e.g. Alstrup & Hawksworth (Reference Alstrup and Hawksworth1990) Intralichen lichenicola (M. S. Christ. & D. Hawksw.) D. Hawksw. & M. S. Cole

Conidia developing in conidiomata 22

22(21) Conidia aseptate, spherical; Hawksworth (Reference Hawksworth1981) Lichenoconium lecanorae (Jaap) D. Hawksw

Conidia 1-septate, basally truncate; Hawksworth (Reference Hawksworth1981), occurrence on L. polytropa fide e.g. Brackel (Reference Brackel2014) Lichenodiplis lecanorae (Vouaux) Dyko & D. Hawksw.

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Muggia for contributing relevant specimens to this study and W. Obermayer for graphical work. Furthermore, the authors gratefully acknowledge valuable comments from Damien Ertz and Andreas Frisch.

Author ORCID

Martin Grube, 0000-0001-6940-5282.