INTRODUCTION

The past two decades have witnessed rapid and remarkable growth in internationalization activities such as exporting, licensing, and outward foreign direct investments (FDIs) from emerging economies (e.g., BRIC countries) (Chen & Young, Reference Chen and Young2010; Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Morck, Yeung, & Zhao, Reference Morck, Yeung and Zhao2008; UNCTAD, 2008). In response, the literature has turned increasing attention to the internationalizationFootnote [1] of emerging market firms. Nevertheless, mainstream international business theory largely focuses on developed economies (Boisot & Meyer, Reference Boisot and Meyer2008; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson, & Peng, Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa, Peng, & Deeds, Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). Although scholars have gradually conceded that emerging market firms are significantly different from developed market firms in terms of elements affecting internationalization processes (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Deng, Reference Deng2004, Reference Deng2007; Lu, Liu, & Wang, Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Makino, Lau, & Yeh, Reference Makino, Lau and Yeh2002; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Rui & Yip, Reference Rui and Yip2008), it remains unclear what special elements may facilitate or constrain international expansion of emerging market firms.

Emerging economies such as China's are characterized by underdeveloped institutions and heavy government involvement (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008; Yang, Jiang, Kang, & Ke, Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). Governments in emerging economies largely interfere with business operations by controlling many strategic resources (Fan, Wong, & Zhang, Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2007; Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Li & Atuahene-Gima, Reference Li and Atuahene-Gima2001; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). On the other hand, foreign firms with many critical resources (e.g., advanced technologies, know-how, and brand assets) are often more powerful than and impose significant dependence constraints on emerging market firms in their home market (Guler, Guillén, & Macpherson, Reference Guler, Guillén and Macpherson2002; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Peng, Reference Peng2003; Xia, Ma, Lu, & Yiu, Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). That is, local governments and foreign firms are critical sources of external uncertainty and interdependence facing emerging market firms (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Hillman, Withers, & Collins, Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). To cope with those external dependence constraints, emerging market firms tend to use international expansion as an avoidance strategy to reduce their home dependence concentration (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003; Witt & Levin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). Alternatively, emerging market firms may also use an adaptation strategy to absorb the influence of the constraints by local governments and foreign firms in their home market (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). In this study, we argue that one main form of the co-optation strategy for emerging market firms would be to appoint managers who have prior political backgrounds, defined as political connections following the economics and finance literature (Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Fisman, Reference Fisman2001; Sun, Mellahi, & Wright, Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). These political connections can help emerging market firms establish linkages with government agencies and then reduce their resource dependence and the institutional constraints imposed by local governments (Boyd, Reference Boyd1990; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Lester, Hillman, Zardkoohi, & Cannella, Reference Lester, Hillman, Zardkoohi and Cannella2008; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sun, Wright, & Mellahi, Reference Sun, Wright and Mellahi2010b). Meanwhile, these connections can also allow emerging market firms to increase their power relative to that of foreign firms at home by providing government-controlled strategic resources and preferential treatment (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). Therefore, we argue that emerging market firms with political connections at home may be less susceptible to the constraints imposed by local governments and foreign firms to internationalize. Yet we know little about whether and how political connections at home are related to international expansion of emerging market firms. Although the extant literature has recognized the importance of political connections in emerging economies (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011), most previous studies focus on exploring their effects on firm performance rather than on international expansion or other strategic behaviors. Since the narrow focus has drawn inconclusive findings (Boubakri, Cosset, & Saffar, Reference Boubakri, Cosset and Saffar2008; Faccio, Reference Faccio2006, Reference Faccio2009; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2007; Fisman, Reference Fisman2001; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012), research is needed to explore potential operating mechanisms through which political connections may improve or damage firm performance.

Meanwhile, in studying emerging economies, scholars increasingly recognize that institutionsFootnote [2] play an important role in shaping firms’ strategies and behaviors within those economies (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik, & Peng, Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009; Peng, Wang, & Jiang, Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005). Unlike developed economies, most emerging economies such as China's are in economic transition and are experiencing substantial institutional changes (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). In particular, although the literature has emphasized that institutions may determine international expansion of emerging market firms (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Luo, Xue, & Han, Reference Luo, Xue and Han2010; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2005; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008), the proposition is largely untested (Wang, Hong, Kafouros, & Boateng, Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Boateng2012). In addition, most previous studies focus on host formal institutions (e.g., antidumping laws and tariff barriers) but usually neglect the effect of home formal institutions (Buckley, Clegg, Cross, Liu, Voss, & Zheng, Reference Buckley, Clegg, Cross, Liu, Voss and Zheng2007; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009). Therefore, it is far from clear how home formal institutions may influence international expansion of emerging market firms.

More importantly, since political connections at home play a strong role mainly because of underdeveloped institutions and heavy government regulation in emerging economies (Ambler & Witzel, Reference Ambler and Witzel2004; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng, Lee, & Wang, Reference Peng, Lee and Wang2005; Wu, Li, & Li, Reference Wu, Li and Li2013), the linkage between political connections and internationalization should be context specific rather than universal. Emerging economies have institutions that substantially vary in views of time and space (Chan, Makino, & Isobe, Reference Chan, Makino and Isobe2010; Fan, Wang, & Zhu, Reference Fan, Wang and Zhu2011; Li, He, Lan, & Yiu, Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012). As the external environment is so uncertain, emerging market firms may need to exploit political connections to reduce dependency on the external environment (e.g., foreign firms and local governments in this study) (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wright and Mellahi2010b; Sun, Mellahi, & Liu, Reference Sun, Mellahi and Liu2011). Therefore, institutional characteristics may moderate the role of political connections in shaping emerging market firms’ strategies of internationalization. However, few studies, if any, have theoretically or empirically addressed this issue.

In this study, therefore, we address the literature gaps by examining the impact of political connections in the home market, home formal institutions, and their interactions on the internationalization of emerging market firms in the context of China. We chose China as the research context for three reasons. First, since implementing the ‘go global’ strategy in 1999 and entering the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has become the world's largest exporter with the most outward foreign direct investor among emerging economies (Gao, Murray, Kotabe, & Lu, Reference Gao, Murray, Kotabe and Lu2010; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Yeung and Zhao2008; UNCTAD, 2008). Thus, China's increasing importance in the global economy deserves more research attention. Second, China has long been characterized as a guanxi society, where formal institutions (e.g., laws and regulations) are weak and managers cultivate social ties (e.g., political connections) as important nonmarket strategies for dealing with environmental uncertainty and interdependence (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Luo, Huang, & Wang, Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2011; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011; Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996). Thus, China provides an excellent setting to explore the potential role of political connections in shaping firms’ strategies and behaviors. Third, China's ongoing transition from a planned to a market-based economy and its diverse markets and geographic regions provide substantial variations within China in formal institutional development (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Makino and Isobe2010; Child & Tse, Reference Child and Tse2001; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wang and Zhu2011; Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012; Luo & Peng, Reference Luo and Peng1999). This special institutional context enables us to explore the role of formal institutions in one country without potential disturbances resulting from unobserved country factors in cross-country studies (Li, Yue, & Zhao, Reference Li, Yue and Zhao2009; Luo, Wan, Cai, & Liu, Reference Luo, Wan, Cai and Liu2013; Wang, Wong, & Xia, Reference Wang, Wong and Xia2008).

Drawing on the resource dependence theory and institution-based view, we argue that political connections at home may help emerging market firms handle environmental fluctuations resulting from interdependence on external organizations (i.e., local governments and foreign firms) and ultimately obtain competitive advantage in their home market (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Li & Atuahene-Gima, Reference Li and Atuahene-Gima2001; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). Therefore, emerging market firms with effective political connections may have less need to use international expansion as an avoidance strategy than their counterparts without political connections (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Deng, Reference Deng2004, Reference Deng2007; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Rui & Yip, Reference Rui and Yip2008; Witt & Levin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). That is, political connections at home may hinder emerging market firms from international expansion. Meanwhile, the development of home formal institutions will bring about increasing competitive market conditions and free market business operations (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Sun, Mellahi, & Thun, Reference Sun, Mellahi and Thun2010a; Yiu, Bruton, & Lu, Reference Yiu, Bruton and Lu2005), which may make the home market a more rigorous training ground to develop and improve the emerging market firms’ managerial and absorptive capabilities needed for international expansion (Deng, Reference Deng2009; Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010). In addition, given that political connections play institutional context-specific roles, we also propose that home formal institutional development may moderate the impact of political connections on international expansion of emerging market firms. Finally, our findings, based on a data set of 6,320 firm-year observations for 1,547 Chinese listed firms from 2005 to 2010, provide solid empirical support for our three theoretical proposals. We demonstrate that both political connections and formal institutions at home have an important impact on international expansion of local firms in the context of China and, by extension, other emerging economies.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

What drives or hinders international business strategies? Scholars of international business have debated that popular topic throughout the last two decades or so (Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Liang, Lu, & Wang, Reference Liang, Lu and Wang2012; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008). However, most previous studies focus on multinational enterprises (MNEs) from Western developed economies (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009), so the debate continues as to whether the literature can be applied to emerging market MNEs (Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Dunning, Reference Dunning2006; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006). The fundamental OLI framework in international business (Dunning, Reference Dunning1988, Reference Dunning2001) argues that firms internationalize to exploit ownership-specific advantages (O-advantages), location advantages (L-advantages), and internationalization advantages (I-advantages) (Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Liang et al, Reference Liang, Lu and Wang2012; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010). However, emerging market firms apparently expand internationally not to exploit previously developed advantages but largely to overcome their competitive disadvantages at home (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Makino et al., Reference Makino, Lau and Yeh2002; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). Given that MNEs from developed and emerging economies differ essentially in their motivation for internationalization, scholars have gradually conceded that they may also differ significantly in terms of elements that influence internationalization processes. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to explore two specific elements – political connections in the home market and home formal institutions – in shaping internationalization strategies of emerging market firms in the context of China.

Political Connections and Internationalization

Despite global trends toward privatization and deregulation, governments are still a critical source of external interdependency and uncertainty for business (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012), particularly in emerging economies with underdeveloped institutions and heavy government regulation (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wright and Mellahi2010b; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). Therefore, a critical element of business success in emerging economies is to build and maintain political connections by appointing managers with prior political backgrounds (Khanna, Palepu, & Sinha, Reference Khanna, Palepu and Sinha2005; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Hillman, Zardkoohi and Cannella2008; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2011; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Thun2010a; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). As resource dependence theory suggests, political connections link firms to the government and protect them from external environmental fluctuations, especially in emerging economies (Boyd, Reference Boyd1990; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wright and Mellahi2010b). Regarding internationalization strategies, political connections at home, performing as an important co-optation strategy (Boyd, Reference Boyd1990; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Lester et al., Reference Lester, Hillman, Zardkoohi and Cannella2008; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Wright and Mellahi2010b), may reduce emerging market firms’ need to use international expansion to avoid institutional and resource dependence constraints imposed by local governments in their home market (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007). First, political connections may give focal firms access to government-controlled strategic resources (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000), such as more and easier access to bank financing (Khwaja & Mian, Reference Khwaja and Mian2005), corporate bailouts (Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, Reference Faccio, Masulis and McConnell2006), and government subsidies (Wu & Liu, Reference Wu and Liu2011). Second, as emerging economies such as China's usually lack developed formal institutions, the enforcement of business exchanges and contracts is usually difficult and largely dependent on the support of local governments. The government linkages (i.e., political connections) then may substitute for formal institutional support for protecting business interests and reducing external uncertainty (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2011; Peng & Health, Reference Peng and Health1996; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996). Third, in addition to controlling strategic resources, the government retains considerable power in approving projects and regulating industrial development in emerging economies (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Li & Atuahene-Gima, Reference Li and Atuahene-Gima2001; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). Emerging market firms can exploit their political connections to get approval for business projects from the government and gain access to government-regulated industries (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). Finally, as the government makes many critical decisions in transition processes (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000), emerging market firms face substantial policy uncertainties in their home market. Managers can leverage their government linkages to access valuable political decision making and even proactively shape favorable government policies and, thus, help emerging market firms absorb significant external uncertainty and dependence regarding government policy, regulation, and enforcement at home (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003).

Besides local governments, foreign firms are another group of powerful actors with which emerging market firms have exchange relationships in their home market (Guler et al., Reference Guler, Guillén and Macpherson2002; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Peng, Reference Peng2003; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). Foreign firms who are usually global giants with critical technology, know-how, or brand, are often more powerful than local firms in emerging economies (Guler et al., Reference Guler, Guillén and Macpherson2002; Inkpen & Beamish, Reference Inkpen and Beamish1997; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Yan & Gray, Reference Yan and Gray1994). As emerging market firms often have difficulty absorbing the constraints imposed by foreign firms, they tend to use international expansion as a springboard to reduce their home dependence concentration and, thus, increase their relative power (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer1976; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). Again, political connections may reduce emerging market firms’ need for using international expansion as an avoidance strategy by altering the power imbalance between emerging market firms and foreign firms. Due to the liability of foreignness, foreign firms usually depend on local partners for host country/region knowledge and resources (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). This is particularly true in emerging economies, because in emerging economies with underdeveloped institutions and heavy government regulation, nonmarket guanxi and related knowledge (e.g., political connections) are often much more important for business success than market-based skills and resources that foreign firms are in control of (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). In this context, emerging market firms can leverage their political connections at home to increase their bargaining power relative to foreign firms and, thus, reduce their susceptibility to the pressures imposed by foreign firms to diversify internationally (Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer1976; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). In addition, since the nonmarket strategy of building and maintaining political connections at home may help emerging market firms balance the power advantage of local governments and foreign firms and ultimately succeed in their home market, emerging market firms would be accustomed to this nonmarket strategy with low competitive pressure and unaware of the rapidly changing competitive environment and the urgent need to develop market-based capabilities (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). Then these lock-in effects would further hinder those politically connected firms from international expansion in emerging economies (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Geringer, Tallman, & Olsen, Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009).

Therefore, we propose that emerging market firms may exploit their political connections at home to reduce the dependence constraints imposed by local governments and foreign firms and, thus, have less need for using international expansion as an avoidance strategy. In short, political connections at home may hinder emerging market firms from international expansion. On the other hand, political connections at home may also promote emerging market firms to internationalize to some extent, because politically connected firms’ resource advantages may facilitate their international diversification and emerging market governments such as China's may have political and economic ambitions to encourage their firms, especially politically connected firms, to invest abroad (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Xue and Han2010; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). However, since international expansion is a risk-taking strategy involving uncertainties, difficulties, and obstacles from foreign markets and vitals, managerial capabilities would be much more important than external resources and government support (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). That is, in this case, political connections are at most necessary but not sufficient conditions for emerging market firms to internationalize. In summary, taking into account two competing effects of political connections on the internationalization of emerging market firms, we suggest that the negative effect would dominate the positive one.Footnote [3] Then we arrive at our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Internationalization will be less likely when emerging market firms have political connections in their home market.

Home Formal Institutions and Internationalization

Western developed economies, such as in the United States, operate under relatively stable and market-based institutional frameworks, but emerging economies, such as in China, are experiencing significant institutional changes as they transition from planned to market-based economies (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). The emerging institution-based view stresses that institutions determine strategic choices and behavior in emerging market firms (North, Reference North1990; Scott, Reference Scott1995; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). ‘It is research on emerging economies that has pushed the institution-based view to the cutting edge of strategy research’ (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008: 923). However, the institution-based view of strategy still remains in its infancy. Although institutions may significantly shape international expansion strategies of emerging market firms (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Hotho & Pedersen, Reference Hotho and Pedersen2012; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Xue and Han2010; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2005; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008), few studies have systematically tested that proposition (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Boateng2012). In particular, the extant literature on institutions and international expansion largely focuses on host formal institutions but usually neglects home formal institutions (Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Clegg, Cross, Liu, Voss and Zheng2007; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009). Since developed economies have relatively stable, market-based institutional frameworks, previous studies have reasonably focused on host formal institutions when studying MNEs based in developed economies (Boisot & Meyer, Reference Boisot and Meyer2008; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008). However, studies of emerging market firms increasingly recognize that home formal institutions determine internationalization strategies (Deng, Reference Deng2009; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Eden, Lau and Wright2000; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009; North, Reference North1990; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005).

First, home formal institutions may affect whether firms can upgrade their internal resources and discipline their capabilities, both so fundamental to global expansion (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Boateng2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). As new institutional economics suggest, with developed formal institutions at home, emerging market firms may face effective protection of property rights and enforcement of contracts and low transaction frictions and costs in business exchanges (Coase, Reference Coase1937; Hotho & Pedersen, Reference Hotho and Pedersen2012; North, Reference North1990; Williamson, Reference Williamson1975), resulting in increasing competitive market conditions and free market business operations (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Thun2010a; Yiu et al., Reference Yiu, Bruton and Lu2005). Market competitiveness at home may then become a rigorous training ground to develop and improve emerging market firms’ managerial and absorptive capabilities needed for international expansion (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010). Second, the development of formal institutions is usually accompanied by reduced government interference and industry deregulation (Yiu et al., Reference Yiu, Bruton and Lu2005), which would substantially reduce transaction costs of exchanges between focal firms and the government (North, Reference North1990; Williamson, Reference Williamson1975). Firms would then depend less on the government and have less need for government linkages through political connections for the sake of smoothing the running of business operations (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Thun2010a). As social networking strategy declines, managers may focus instead on developing and improving managerial skills and capabilities, thereby facilitating internationalization strategies. Third, the market would be gradually opened along with the development of formal institutions. The open market then would attract much investment from foreign MNEs (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; UNCTAD, 2005). Through direct interaction with global MNEs at home, emerging market firms would learn technological and organizational skills and accumulate foreign market knowledge, giving them real options to undertake outward internationalization (Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007). Finally, most emerging economies implement export-led growth strategy, and their governments are intrinsically incentivized to encourage local firms to globalize (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007). As formal institutions develop, numerous foreign investments are attracted to emerging economies. The government then accumulates massive foreign exchange reserves and uses them to subsidize international expansion for local firms (Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Globerman & Shapiro, Reference Globerman and Shapiro2009). China's three-decade economic reform has followed that pattern. Taken as a whole, we argue that the development of home formal institutions may enable emerging market firms to engage in international expansion. Therefore,

Hypothesis 2: Internationalization will be more likely when emerging market firms are located in regions that have higher levels of formal institutions.

The Moderating Effect of Home Formal Institutions

In emerging economies, home formal institutions may do more than directly affect internationalization. They may also indirectly affect internationalization through interplay with political connections (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Murray, Kotabe and Lu2010; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010). As explained before, political connections are essential mainly because of underdeveloped market-supporting institutions and heavy government regulation in emerging economies (Ambler & Witzel, Reference Ambler and Witzel2004; Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Lee and Wang2005; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li and Li2013). In other words, political connections at home, international expansion, and home formal institutional context are specifically linked in emerging economies, where institutional context varies substantially (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Makino and Isobe2010; Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012). Institutional contexts may influence the extent to which political connections at home help emerging market firms reduce external uncertainty and interdependence imposed by local governments and foreign firms. Therefore, we argue that the institutional characteristics of emerging economies may moderate the role of political connections in shaping local firms’ internationalization strategies.

One basic tenet of resource dependence theory is that firms need environmental linkages depending on the levels of dependence they face (Boyd, Reference Boyd1990; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). The development of formal institutions will usually bring about stable and predictive public policies and less government regulation (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Thun2010a; Yiu et al., Reference Yiu, Bruton and Lu2005). For instance, relative to emerging market firms, firms based in economies with developed institutional infrastructures are less able to expropriate rents from public policies. They have better access to most industries, a more effective legal system for protecting their business interests, and more dependence on efficient external markets to obtain necessary strategic resources. Therefore, higher development levels of formal institutions mean less risk and less government-created external uncertainty. That is, the development of home formal institutions may not only reduce emerging market firms’ dependence constraints imposed by local governments, but also reduce the emerging market firms’ need for a nonmarket strategy for building and maintaining political connections at home (Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). In addition, the effectiveness of political connections would also decrease. Since market competition increases and the nonmarket strategy declines, emerging market firms may focus instead on developing and improving their managerial skills and capabilities that would be needed for international expansion (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). Meanwhile, the development of home formal institutions would increase power imbalance between foreign firms and local firms in emerging economies. Higher development levels of formal institutions may provide better market environment for foreign firms to fully exploit their market-based skills and capabilities to create and sustain competitive advantages in host emerging economies. Then foreign firms may impose more dependence constraints on emerging market firms in their home market (Guler et al., Reference Guler, Guillén and Macpherson2002; Inkpen & Beamish, Reference Inkpen and Beamish1997; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Yan & Gray, Reference Yan and Gray1994). Since emerging market firms are often unable to absorb those constraints at home, they may be more inclined to avoid their home dependence constraints by expanding internationally (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Witt & Levin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013). In other words, with the development of home formal institutions, political connections at home would be increasingly unable to reduce emerging market firms’ need to use international expansion as an avoidance strategy.

Therefore, we anticipate that political connections at home will negatively affect internationalization depending on the institutional conditions in which emerging market firms are embedded. Thus:

Hypothesis 3: The negative relationship between internationalization and political connections at home will be weaker for emerging market firms located in regions that have higher levels of formal institutions.

METHOD

Sample and Data

Our original sample included all companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Chinese Stock Exchanges from 2005 to 2010 (inclusive). We chose 2005 as the beginning of our sample period for two reasons. First, most Chinese listed firms did not annually report their managers’ detailed resumes until 2004, and we needed those resumes for data regarding political connections. Second, to control the potential problem of endogeneity between focal firms’ political connections and their internationalization strategy, we used internationalization in the next year as the dependent variable.

Our original sample included 9625 firm-year observations from 2005 to 2010. To minimize the influence of potentially abnormal samples, we excluded financial firms (145 observations), firms that were in a state of special treatment (ST) (804 observations),Footnote [4] firms that had listed less than one year (718 observations), firms that had issued debt exceeding asset value (89 observations), and firms that had missing data (1,549 observations). The final sample included 6,320 firm-year observations for 1,547 listed firms. Firms in each sample year from 2005 to 2010 numbered 1,082, 1,161, 870, 965, 819, and 1,423, respectively.

Our data on formal institutions across regions in China came from the National Economic Research Institute's (NERI's) marketization index (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wang and Zhu2011). We obtained detailed resumes of all managers for each Chinese listed company in each fiscal year and other financial data from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research database (CSMAR; www.gtarsc.com), a major provider of China data.

Measures

Dependent variable. We used two proxies to measure the dependent variable, internationalization. One is a dummy variable, denoted by INTDUM, to capture the likelihood of internationalization; the other is a continuous variable, denoted by INTRATIO, to capture the degree of internationalization. In China, listed companies usually report total overseas sales without detailed information about the composition of that sales. Therefore, following previous studies (e.g., Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Hitt, Hoskisson, & Kim, Reference Hitt, Hoskisson and Kim1997; Tan, Peng, & Sun, Reference Tan, Peng and Sun2008), we calculated the degree of the internationalization variable, i.e., INTRATIO, as the ratio of a focal firm's overseas sales, which includes sales from exporting and foreign subsidiaries, to its total worldwide sales. Then the likelihood of the internationalization variable, i.e., INTDUM, equals one if INTRATIO is larger than zero, and zero otherwise. Given the distinctive difference in institutions between the Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan regions and mainland China (Tan et al., Reference Tan, Peng and Sun2008), most Chinese listed firms still regard sales from the Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan regions as overseas sales and add the sales from these three regions to their total overseas sales.

Independent variables

We had two independent variables in this study. One is the variable corporate political connections. Following prior studies (e.g., Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2007; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li and Li2013), we defined focal firms’ political connections as their chief executive officers (CEOs) or chairmen of directors having political experience, which includes serving in the government, the Party committee, the People's Congress, the People's Political Consultative Conference, the People's Court, the People's Procuratorate, or the People's Bank at both local and central levels. In China, besides the CEO, the chairman of directors is also one of the most important executives in making and implementing strategic decisions in a firm. Thus, the political experience of both the CEO and the chairman of directors may influence a firm's international business strategy in China. Specifically, we measured corporate political connections with a dummy variable, which equals one if the CEO or chairman of directors had political experience, and zero otherwise.

The other independent variable is the development level of China's regional formal institutions. We took the NERI's marketization index to measure formal institutional development across China's 31 provincial level regions (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wang and Zhu2011), an index many empirical studies have used to measure China's regional formal institutional development (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Yue and Zhao2009; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Wan, Cai and Liu2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wong and Xia2008). Specifically, this marketization index captures regional market development in five aspects – relationship between government and markets, nonstate sector in the economy, product markets, factor markets, and market intermediaries and legal environment (Li et al., Reference Li, Yue and Zhao2009). The Appendix shows details regarding the measurement process of this marketization index. Overall, higher index scores suggest greater formal institutional development.Footnote [5]

Control variables

As with previous internationalization studies, we controlled factors that may systematically relate to internationalization processes. We included firm size (measured as the natural log of total assets) as a control variable, since larger firms are more likely to internationalize as natural growth steps (Fernhaber, Gilbert, & McDougall, Reference Fernhaber, Gilbert and McDougall2008). Because international expansion strongly demands financial outlays (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009), we included leverage (measured as the ratio of total debt and total assets), operating cash flows (measured as the ratio of net cash flows from operating activities to total assets at the beginning of the year), ROA (measured as the ratio of net profit and total assets), and cross-listing (dummy variable, equals one if a focal firm is listed in both domestic and foreign capital markets), reflecting a firm's unused debt capacity, the availability of internal funds, past performance, and the potential capacity for raising outside capital, respectively. We controlled R&D intensity (measured as the ratio of R&D investment to total sales income), because proprietary assets from R&D investment provide a firm with a unique advantage and are highly transferable to foreign markets (Delios & Beamish, Reference Delios and Beamish1999). Given that highly valuable firms enjoy capital advantages that help them raise outside capital needed for international expansion (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Boateng2012), we also controlled focal firms’ market values, that is, Tobin's Q, which equals the ratio of the market value of equity plus the book value of debt over the book value of total assets.Footnote [6] Firm risk (measured by beta, computed by regressing a firm's weekly stock return on the corresponding market index return in a given year) is also included, because a firm's strategic decisions such as internationalization are largely affected by its operating risk. As Porter (Reference Porter1990) suggests that industrial conditions may determine a firm's strategy and performance, we controlled the industry competitive condition, denoted by Industry HHI and measured as the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index of sales income for all listed firms within a given industry.

Following prior research, we included largest shareholder's ownership as a control variable, because higher ownership may give the largest shareholder stronger power to influence a firm's strategy (Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012). As the board of directors makes a firm's strategic decisions, we controlled board size (proxied as the number of directors on the board) and board independence (proxied as the ratio of independent directors on the board). We included a dummy variable, CEO duality, which equals one if the same individual serves as the CEO and chairman of the board, and zero otherwise, to control the important effect of CEO power on strategy making. As we know, managerial experience, capabilities, and incentives are essential for firms to implement internationalization strategies (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Lu and Wang2012), so we also controlled for average age of top management team (TMT), gender ratio of TMT, and management ownership. Besides TMT, outside institutional investors are professional investors with rich business experience and can provide valuable resources and suggestions for firms going international. Thus, institutional ownership is included as a control variable. In addition, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) enjoy far more government support than non-SOEs in input factors, product market, and capital market (Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). Hence, we controlled an indicator variable, SOEs, which equals one if a government agency is the largest shareholder.

Finally, we included industry dummies and year dummies to control for industry effects and time effects, respectively.

The Model

As the likelihood variable is discrete, taking one or zero value, we used logistic regression models to examine the effects of political connections and formal institutions on the likelihood of internationalization (Hosmer & Lemeshow, Reference Hosmer and Lemeshow2000). Meanwhile, since the degree variable of internationalization is a limited dependent variable, taking on greater than or equal to zero values, we took Tobit models to investigate the relationship between political connections and formal institutions and the degree of internationalization (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2009).

One important issue of regression models is the potential endogeneity of the regressors. That is, the observed relationships between political connections and formal institutions and the likelihood and degree of internationalization in this study might be the result of a reversed causality. In this study, we mainly used the lagged independent variables to reduce the possibility of endogeneity. Alternatively, we also tried to use Heckman's two-stage model where we could apply Heckman's selection model to control for selection bias by including the inverse Mills ratio in the second stage regression, to control the questionable problem of endogeneity for the sake of a robustness check. We found consistent results (not reported here for brevity).Footnote [7] In addition, we did not use multilevel methods to examine our multilevel data (firms nested in provinces), because the intraclass correlation values for our two dependent variables, INTDUM and INTRARIO, are no larger than 0.2, which is close to zero and much less than the cutoff value 0.4. Despite that, we also tried to employ a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model and multilevel mixed-effects linear model for dependent variables INTDUM and INTRARIO, respectively, for robustness check and found statistically similar results (not reported here for brevity).

Furthermore, we centered the interaction variables and checked the average variance inflation factor (VIF) for each regression model and found that all VIFs are far below 10, the acceptable cutoff point (Neter, Wasserman, & Kutner, Reference Neter, Wasserman and Kutner1996). Thus, the issue of multicollinearity appears insignificant. Heteroscedasticity is corrected using robust (Huber–White) standard errors.

RESULTS

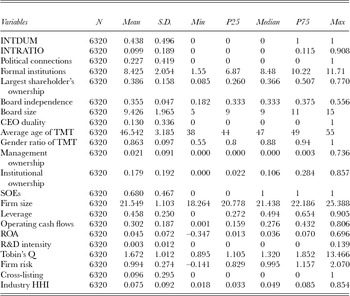

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics. In the total sample, 43.8% firms are MNEs that have implemented internationalization strategy and have overseas sales. However, the average degree of internationalization is only 9.9%, suggesting much opportunity for Chinese firms to internationalize. 22.7% of CEOs or chairmen of directors in our sampled firms had political connections, much higher than 2.83% for 47 countries or regions in Faccio (Reference Faccio2009), indicating that political connections are common in China. The largest shareholders have an average ownership of about 38.6%, indicating that the one-dominant controlling phenomenon (yigududa) is still severe in Chinese listed firms. On average, boards have more than nine directors and about 35.5% independent directors. The average 2.1% managerial ownership and 17.9% institutional ownership are much lower than those in Western developed countries. Participants averaged about 47 years of age, and the gender ratio was about 8.63% women, suggesting that TMT members were older individuals and that few women served in the TMTs of Chinese listed firms. In the total sample, 68.0% were state-owned or state-controlled firms, indicating that SOEs still dominate China's stock market. For the descriptive statistics of other variables, we noticed nothing unusual.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

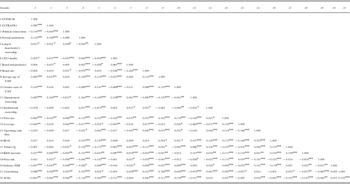

Table 2 represents the correlation coefficients of the variables. It shows two significant and negative correlations between political connections and the likelihood of internationalization (r = –0.110, p < 0.001) and between political connections and the degree of internationalization (r = –0.044, p < 0.001), which provides some preliminary evidence for Hypothesis 1. Consistent with the prediction in Hypothesis 2, we found two significant and positive correlations between formal institutions and the likelihood of internationalization (r = 0.134, p < 0.001) and between formal institutions and the degree of internationalization (r = 0.169, p < 0.001). Despite high correlation (r = 0.595, p < 0.001) between our two independent variables – INTDUM and INTRATIO – all the other correlation coefficients are much less than 0.5, indicating that the problem of multicollinearity may be weak in this study.

Table 2. Pearson correlation coefficients (excluding industry and year indicators) (N = 6320)

Notes:

+ p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

All two-tailed tests.

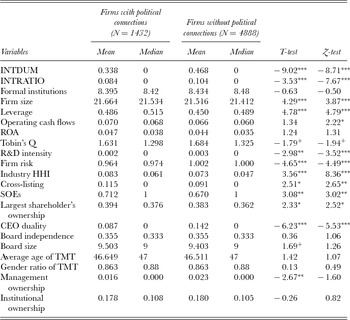

Table 3 displays the statistics for two subsamples of firms sorted by whether their CEOs or chairmen of directors were politically connected. Consistent with Table 2, the mean and median likelihood and degree of internationalization for firms with political connections at home are statistically significantly lower than those without political connections, indicating that political connections hamper firms from implementing internationalization strategy. Moreover, our between-group comparison shows that politically connected firms have larger firm size and higher leverage, but lower Tobin's Q, lower R&D intensity, and lower firm risk than do their politically unconnected counterparts.

Table 3. Difference between firms with and without political connections

Notes:

+ p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

All two-tailed tests.

Table 4 documents the regression results with eight models. The first four models (i.e., Models 1–4) take the likelihood variable of internationalization (i.e., INTDUM) as the dependent variable. Thus, we used the logistic regression model to examine Models 1–4. Since the degree of internationalization is the dependent variable in Models 5–8, we used the Tobit regression model in these. In particular, we employed the hierarchical regression approach to test our three hypotheses. The model fit, as indicated by the log likelihood ratio, improved consistently step by step. Both industry and year indicators are included in all regression models but not reported.

Table 4. Regression results on political connections, formal institutions and internationalization (N = 6320)

Notes: Z-statistics, based on standard errors adjusted for Huber–White, are in parentheses.

+ p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. All two-tailed tests.

The interaction variables were mean centered. Industry and year indicators were included but not reported here.

Hypothesis 1 relates to the impact of political connections. As Table 4 shows, the Political connections variable is negatively and significantly related to the likelihood of internalization (Model 2: β = –0.399, p < 0.001) and to the degree of internationalization (Model 6: β = –0.041, p < 0.001). From the logistic regression model, we can further calculate the odd ratio and marginal effect of the Political connections variable. Specifically, the odd ratio and marginal effect of the Political connections variable in Model 2 are 67.1% and –9.4%, respectively. The economic implication of these two values is that the likelihood of internationalization for politically connected firms is only about 67.1% of that for their counterparts without political connections, and the likelihood of internationalization for focal firms would be cut down by 9.4% for their political connections, displaying the substantial impact of political connections on international expansion of focal firms. In consequence, these results indicate that compared with their counterparts without political connections, politically connected firms have lower likelihood and degree of internationalization, strongly supporting Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 pertains to formal institutions in firms’ home regions. As Table 4 shows, the Formal institutions variable positively and significantly affects the likelihood and degree of internationalization (Model 3: β = 0.162, p < 0.001; Model 7: β = 0.037, p < 0.001). The odd ratio and marginal effect of the Formal institutions variable in Model 3 are 117.6% and 3.9%, respectively. These results suggest that the development of formal institutions in focal firms’ home regions may substantially strengthen the motives of internationalization. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is also fully supported.

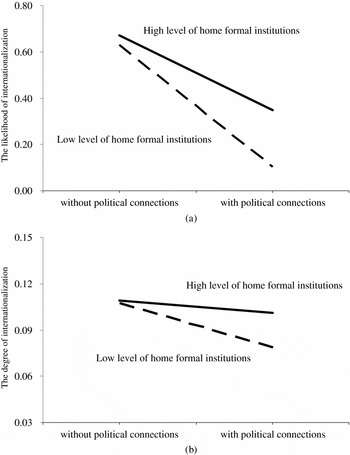

Hypothesis 3 predicts an interactive effect of political connections and formal institutions at home on the likelihood and degree of internationalization. As Table 4 shows, the interaction of political connections and formal institutions, i.e., Political connections × Formal institutions, gets positive and significant regression coefficients in both Model 4 (β = 0.103, p < 0.01) and Model 8 (β = 0.027, p < 0.001). The results indicate that the development of formal institutions in firms’ home regions is able to reduce the negative effect of political connections at home on the likelihood and degree of internationalization. These results are visually plotted in Figure 1. To create this figure, following Aiken and West (Reference Aiken and West1991) and Luo et al. (Reference Luo, Wan, Cai and Liu2013), we constrained all control variables to their mean values in Models 4 and 8 in Table 4 and then conducted simple slope tests after splitting our sample into two groups according to the level of home formal institutions – high (above the mean) and low (below the mean). Specifically, Part (a) of Figure 1 shows that the negative effect of political connections on the likelihood of internationalization is weaker for firms located in regions with high levels of formal institutions than for firms located in regions with low levels of formal institutions; similarly, Part (b) of Figure 1 displays that the negative effect of political connections on the degree of internationalization is also weaker for firms located in regions with high levels of formal institutions than for firms located in regions with low levels of formal institutions. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 has strong empirical support, too.

Figure 1. The graphic representation of the interaction effects for Hypothesis 3

Finally, as to the regression results of control variables, we found that Leverage, ROA, Tobin's Q, Cross-listing, SOEs, Average age of TMT, Gender ratio of TMT, and Management ownership had consistent and significant coefficients in all models, suggesting that these factors have systematic impacts on the internationalization strategy of firms. Specifically, firms with higher leverage, performing worse, with lower Tobin's Q, and having the government as the controlling shareholder may engage less in internationalization, whereas firms that are cross-listed on several stock markets and have male TMTs with more experience are much more likely to internationalize.

DISCUSSION

This study aims to enrich our understanding of the role of political connections and formal institutions at home and their interaction in shaping emerging market firms’ strategies of internationalization. Our results suggest that compared with their politically unconnected counterparts, politically connected firms have a lower likelihood to expand internationally and experience a lower degree of internationalization in emerging economies. Meanwhile, we find that emerging market firms located in regions with a higher development level of formal institutions are more likely to go global and invest more abroad. What is more, home formal institutions would also reduce the impact of political connections on international expansion of emerging market firms. Our findings illustrate how political connections and formal institutions at home matter in international business, particularly the internationalization of emerging market firms.

Contributions

Our study offers a number of contributions to the extant literature. First, theoretically, we use the resource dependence theory to explain political actions and their effects on international expansion of emerging market firms (Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003). The resource dependence theory is useful for analyzing the use of political connections in emerging economies to counter institutional voids and heavy government regulation (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Thun2010a). Institutional voids and government regulation may cause significant external uncertainty and interdependence, so firms can use political connections to reduce dependence on the larger social system (i.e., local governments and foreign firms in this study) (Boyd, Reference Boyd1990; Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Hillman et al., Reference Hillman, Withers and Collins2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik2003; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). We argue that emerging market firms may leverage their political connections at home to buffer them from environmental fluctuations resulting from significant dependence constraints imposed by powerful local governments and foreign firms, and thus reduce their susceptibility to external pressures in their home market to internationalize (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Makino et al., Reference Makino, Lau and Yeh2002; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Yiu2013; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). What is more, cultivating political connections constitutes a nonmarket strategy that may also bring structural and cognitive negative lock-ins that hinder emerging market firms from developing managerial skills and capabilities essential for internationalization (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Geringer et al., Reference Geringer, Tallman and Olsen2000; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). Specifically, our results suggest that political connections at home may harm long-term growth by keeping emerging market firms from expanding internationally. Overall, this study enriches the literature on resource dependence theory and its application in explaining the roles of corporate political actions in the context of emerging economies.

Second, this study is one of the few to examine the role of home formal institutions in shaping internationalization decisions of emerging market firms. Although the literature has increasingly emphasized that institutions have a fundamental impact (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Xue and Han2010; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2005; Witt & Lewin, Reference Witt and Lewin2007; Yamakawa et al., Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2008), the proposition has rarely been systematically tested. Drawing on the institution-based view, we argue that home formal institutions create free and competitive market environments allowing emerging market firms to accumulate their basic technology and managerial capabilities for internationalization possibilities (Cui & Jiang, Reference Cui and Jiang2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hong, Kafouros and Boateng2012; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). Thus, home formal institutions would encourage emerging market firms to pursue internationalization.Footnote [8] Meanwhile, developed external markets could reduce the costs of formal transactions and provide firms with resources necessary for growth, thereby reducing dependence on political connections and their effects on internationalization (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Murray, Kotabe and Lu2010; Li et al., Reference Li, He, Lan and Yiu2012; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011; Wan, Reference Wan2005). We gathered a large firm-level dataset from China and found strong evidence that developed home formal institutions are positively related with internationalization, and also positively moderate the relation between political connections and internationalization. This study largely extends the institution-based view by examining the direct and indirect moderating effects of home formal institutions on the internationalization of emerging market firms.

Finally, in an effort to reconcile prior inconsistent findings, we join the ongoing debate and recent research attention regarding the value of political connections (Boubakri et al., Reference Boubakri, Cosset and Saffar2008; Faccio, Reference Faccio2006, Reference Faccio2009; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2007; Fisman, Reference Fisman2001; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Sheng et al., Reference Sheng, Zhou and Li2011). Most prior literature focused on the effects of political connections on firm performance, with mixed findings (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Mellahi and Wright2012). For example, some studies found that political connections enhanced firm performance (Faccio, Reference Faccio2006; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). Others found that politically connected firms had poor accounting practices and lower market performance (Boubakri et al., Reference Boubakri, Cosset and Saffar2008; Faccio, Reference Faccio2009; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2007). Since firm performance is a complicated function of many factors, significant research is needed to explore potential operating mechanisms through which political connections may improve or damage firm performance. In this study, therefore, we argue and find that emerging market firms may temporarily need political connections to acquire strategic resources, run their businesses more smoothly, and add value, but political connections may prevent them from expanding internationally, damaging firm growth in the long run. More generally, Prashantham and Dhanaraj (Reference Prashantham and Dhanaraj2014) suggest that different relational capital resources may bring differential effects on the internationalization of emerging market firms, while this study further asserts that even the same relational capital resource (here, political connections) may have diverse effects in different contexts (e.g., at home or abroad) and stages of development. In short, political connections are a double-edged sword for emerging market firms.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, the data availability limited our sample to publicly listed companies. In China, listed companies are relatively large and most are SOEs; unlisted firms are small, young, and mostly private. Chinese private unlisted firms may behave differently from listed or state-owned counterparts along many dimensions of internationalization such as motivation, entry modes, and ownership decisions (Ge & Wang, Reference Ge and Wang2013; Lin, Reference Lin2010). In particular, recent practical evidence also suggests that small private firms perform more actively in international expansion than SOEs in China. Therefore, future studies may need to validate our results for firms in different organizational contexts.

Second, our understanding on the antecedents of firm internationalization seems limited and far from clear since our regression models only account for 11.28%–13.06% variance of the likelihood or degree of internationalization. Given the fact that we have followed mainstream international business theory to include most factors that have been argued or found to be systematically related to firm internationalization, our results remind us again that emerging market firms are significantly different from developed market firms in terms of elements affecting internationalization processes (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Deng, Reference Deng2004, Reference Deng2007; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Makino et al., Reference Makino, Lau and Yeh2002; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Rui & Yip, Reference Rui and Yip2008), and so far we know little about this. In particular, as emerging economies such as China's have joined the global economy for a relatively short history and emerging market firms face great liability of foreignness in international expansion, foreign experience would be an important determinant of internationalization. For example, Giannetti, Liao, and Yu (Reference Giannetti, Liao and Yu2014) recently showed that Chinese firms with returnees as board members who have accumulated foreign experience and connections are more likely to make an international merger or acquisition than their counterparts without returnees as board members. Therefore, returnee managers or entrepreneurs would represent another important kind of social capital that may encourage emerging market firms’ internationalization strategies (Filatotchev, Liu, Buck, & Wright, Reference Filatotchev, Liu, Buck and Wright2009; Prashantham & Dhanaraj, Reference Prashantham and Dhanaraj2010). Consequently, much more study is warranted to explore the impact of foreign experience and other special factors on the internationalization of emerging market firms.

Third, although we have provided consistent and robust evidence showing that political connections at home would hamper emerging market firms from international expansion, we cannot deny that in some cases political connections may also drive some internationalization decisions. For example, as part of the country's foreign policy to build and maintain economic and trade cooperation with developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the Chinese government would encourage domestic firms, especially politically connected firms, to invest in those developing countries without any requirement of performance. In return, the government would provide some valuable resources and preferential policies to these firms. More generally, emerging market firms can fully exploit their connections with the government to invest in those foreign countries that have built a bilateral political/trade relationship with their home country (Zhang & Jiang, Reference Zhang and Jiang2012). Taken together, political connections may play diverse roles in shaping emerging market firms’ internationalization strategies as a result of different country destinations. Future research would significantly extend and complement our study by integrating several explanatory theories to examine the moderating roles of foreign country destination and bilateral political/trade relationship on the association between political connections and firm internationalization.

Fourth, although our study follows the mainstream literature to use a binary measure of political connections, that proxy is still incomplete for fully identifying and capturing the influence of political connections. The binary measure cannot differentiate the degree of political connections and the frequency of firms’ use of their connections. In practice, the political system generally has a strict hierarchy of ranking and such ranking makes it feasible to quantify the degree of political connections. Therefore, with the development of a degree variable of political connections, future research should try to explore nonlinear impacts of political connections on firm outcomes. What is more, Du, Zeng, and Du (Reference Du, Zeng and Du2014) recently found that Chinese firms also build political connections by inviting retired government officials to be independent directors besides appointing managers with prior political backgrounds. This finding means that existing research, including this study, probably underestimates the impact of political connections. Future research with richer data should further examine the influence of independent directors’ political connections and even differentiate the extent and nature of the influence between independent directors’ and managers’ political connections. Meanwhile, due to the availability of data, we only took foreign to total sales income ratio but not foreign to total assets ratio, foreign to total employee ratio, or other meaningful alternative measurements to measure the degree of internationalization. In short, our limitations in variable measurement lead to several meaningful avenues for future research.

Fifth, although this study is a useful first step, it focuses on formal institutions and informal political connections and ignores other informal institutions such as norms, cultural distances, and values that may also affect internationalization strategies (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2007; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Filatotchev, Hoskisson and Peng2005; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Jiang, Kang and Ke2009). In fact, with underdeveloped formal systems, emerging economies such as China's tend to have a typical relation-based society where informal social norms and culture are playing significant roles (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; North, Reference North1990; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). In other words, informal social norms and culture may play a more important role in shaping emerging market firms’ internationalization strategies than formal institutions. Thus, future investigations could expand to the effects of diverse informal institutions and also interaction effects between formal and informal institutions, in both home and host countries/regions.

Finally, our picture of internationalization is somewhat coarse grained in that we fail to differentiate types of internationalization such as exporting, licensing, and equity investments. Firms pursuing different types of internationalization activities may need different resources and institutional support and take different risks (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Murray, Kotabe and Lu2010; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Lu and Wang2012; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009). Therefore, political connections and institutions would have different impacts on different types of internationalization activities. Future research with richer data should systematically explore those differences.

CONCLUSION

Emerging market firms are an important force in today's global economy. However, they are significantly different from firms in developed markets regarding their potential for adopting internationalization strategies (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu and Wang2010; Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Yeung and Zhao2008; Rui & Yip, Reference Rui and Yip2008; UNCTAD, 2008). In this study, we draw on the resource dependence theory and institution-based view to show that nonmarket strategies of establishing political connections may keep emerging market firms from expanding globally. The development of home formal institutions, however, may promote internationalization and reduce the dark side of political connections. Empirically, our arguments are strongly supported by a large dataset of 6,320 firm-year observations for 1,547 Chinese listed companies from 2005 to 2010. This study adds to the growing literature on the internationalization of emerging market firms by showing that political connections and formal institutions at home can shape motives and abilities of globalization.

APPENDIX

Measurement Process of the Marketization Index

The marketization index is compiled annually by the NERI and is a comprehensive relative ranking index that captures the regional market development in China. It covers 23 factors in five categories as follows.

Relationship between government and markets: (1) the role of markets in allocating resources using the ratio of government spending to GDP, (2) the level of tax burden on rural residents using the ratio of farmer families’ tax bills to their annual income, (3) the role of government in business using the ratio of total hours firm managers spent dealing with government and government officials to their total working hours, (4) the level of enterprise burden in addition to normal taxes using the ratio of nontax levies to sales, and (5) the size of government using the ratio of employment by the central and local government and various social organizations to population.

Development of nonstate sector in the economy: (1) the ratio of industrial output by the private sector to total industrial output, (2) the ratio of capital investment by the private sector to total capital investment, and (3) the ratio of employment by the private sector to total employment.

Development of product markets: (1) the extent to which prices are set by market demand and supply – (a) the extent to which prices of retail merchandises are set by market demand and supply, (b) the extent to which prices of production factors are set by market demand and supply, and (c) the extent to which prices of farm products are set by market demand and supply; and (2) the extent of regional trade barriers using the ratio of number of trade barriers to GDP.

Development of factor markets: (1) banking development – (a) competitiveness of the banking sector using the ratio of deposits taken by nonstate financial institutions to total deposits and (b) the extent to which banks employ economic criteria in their capital allocation using the ratio of short-term loans to the nonstate sector (such as agricultural loans, loans to village/township enterprises, loans to private enterprises, and loans to foreign-owned enterprises) to total short-term loans; (2) FDI using the ratio of FDI to GDP; (3) mobility of labor using the ratio of employment provided by migrant workers to total employment; and (4) commercialization of technological innovation using the ratio of volume of technological transfers to employment by the technology sector.

Development of market intermediaries and legal environment: (1) Development of market intermediaries – (a) the ratio of number of lawyers to population and (b) the ratio of registered accountants to population; (2) protection of producers’ legal rights using the ratio of number of economic crimes to GDP; (3) protection of property rights – (a) the average number of patents applied per engineer and (b) the average number of patents approved per engineer; and (4) protection of consumer rights using the ratio of number of consumer complaints received by the Consumer Association to GDP.

In summary, the marketization index consists of 23 components. The year 1999 is used as the base year, and the minimum and maximum values for each component are specified as 0 and 10, respectively. Values of each component in other years are normalized by the corresponding base year values. The final marketization index is an arithmetic average of these 23 components. It is worth noting that using the principal components analysis to determine the weights on each of the 23 components leads to no major difference in the relative ranking of regions. For more detailed information about the marketization index, refer to Fan et al. (Reference Fan, Wang and Zhu2011).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/mor.2015.40