INTRODUCTION

Autonomy is an important motivator for those starting and running their own business (Dawson & Henley, Reference Dawson and Henley2012; Edelman, Brush, Manolova, & Greene, Reference Edelman, Brush, Manolova and Greene2010; Stephan, Hart, & Drews, Reference Stephan, Hart and Drews2015). It is a main driver of satisfaction, well-being, and persistence among business owners (Benz & Frey, Reference Benz and Frey2008a, Reference Benz and Frey2008b; Gimeno, Folta, Cooper, & Woo, Reference Gimeno, Folta, Cooper and Woo1997; Lange, Reference Lange2012; Prottas, Reference Prottas2008; Stephan, Reference Stephan2018). Autonomy is also considered to be the basis for entrepreneurial action (Autio, Kenney, Mustar, Siegel, & Wright, Reference Autio, Kenney, Mustar, Siegel and Wright2014; Bradley & Klein, Reference Bradley and Klein2016; McMullen, Bagby, & Palich, Reference McMullen, Bagby and Palich2008). Consequently, the degree of experienced autonomy and the factors that affect it are likely to have significant effects on business ownership, business decisions, growth rates, innovation, and the development of a start-up culture (Heritage Foundation, 2015; Ireland, Tihanyi, & Webb, Reference Ireland, Tihanyi and Webb2008; Wiklund, Davidson, & Delmar, Reference Wiklund, Davidsson and Delmar2003). A vast body of research has shown entrepreneurship to drive job creation, innovation, and economic growth (Audretsch, Keilbach, & Lehman, Reference Audretsch, Keilbach and Lehmann2006; Zhang & Stough, Reference Zhang and Stough2013). The psychology of the founding entrepreneur has a large influence on the operation and success of their firms (Frese & Gielnik, Reference Frese and Gielnik2014). Given the crucial importance of autonomy to business owner/founders, and of entrepreneurship to the economy, it is surprising how little we know of what entrepreneurs do to attain and retain autonomy and the challenges and tensions they face in doing so (Ryff, Reference Ryff2018).

This is partly because entrepreneurship studies have tended to focus on financial performance, despite the well-known importance of motivators related to intangibles such as autonomy and challenge (Davidsson, Reference Davidsson2004; Stephan, Reference Stephan2018). Another reason is that the literature takes autonomy for granted by assuming it comes automatically with the rights of ownership (Croson & Minniti, Reference Croson and Minniti2012; Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996). For example, Lumpkin, Cogliser, and Schneider (Reference Lumpkin, Cogliser and Schneider2009) posit that autonomy may not be an issue among independently owned and managed entrepreneurial firms because such founders are innately acting autonomously. However, Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016) refutes this picture by showing how Dutch business owner/founders make active efforts to attain and maintain autonomy. In that study, and in our present study, the term entrepreneur refers to an individual who founds and owns an independent business. Entrepreneurial autonomy means having decisional freedom with regard to what, how, and when venture-related work will be done, including setting the strategic direction of the firm (Breaugh, Reference Breaugh1999; Lumpkin et al., Reference Lumpkin, Cogliser and Schneider2009). This study asks, ‘What determines the level of autonomy that entrepreneurs experience’? and aims to better understand how entrepreneurs experience autonomy, the factors that affect this experience, and the actions that business owners take to attain and retain it. This implies consideration of the different meanings and purpose of autonomy in different cultures. How autonomy is experienced, the factors that affect it, and the actions that business owners take to attain and retain are likely to vary between countries and cultures. As our study builds on Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016), it can be qualified as an empirical generalization study (Tsang & Kwan, Reference Tsang and Kwan1999). Overall, these types of studies are important because they build a cumulative body of knowledge (Bettis, Helfat, & Shaver, Reference Bettis, Helfat and Shaver2016; Miller & Bamberger, Reference Miller and Bamberger2016). Social science has come under increased pressure to show the contextual nature of its findings (Miller & Bamberger, Reference Miller and Bamberger2016; Welter, Reference Welter2011).

In order to increase our theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial autonomy, we strategically chose to replicate his study in a context, which – at least from a Western perspective – is not often associated with autonomy or freedom: Russia. Given that Russia and the Netherlands have noticeable historical, institutional, cultural, and economic differences (Dumetz & Vichniakova, Reference Dumetz, Vichniakova and Crane2015; McCarthy & Puffer, Reference McCarthy and Puffer2013), we expect the meaning of autonomy in Russia, as well as the strategies to attain and maintain it, to diverge from those observed in the Netherlands. The Russian case is intriguing because, as the literature review section will outline, formal institutions, cultural characteristics, and economic conditions may challenge decisional authority at the level of the individual business owners. Nevertheless, both older and more recent studies have revealed the importance of autonomy as a motive for Russian start-up founders (AGER, 2016; Tkachev & Kolvereid, Reference Tkachev and Kolvereid1999; Zhuplev & Shtykhno, Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009). Equal to their Dutch counterparts, Russian business owners strive for autonomy and take action to achieve it.

Our article begins with a brief summary of the literature on entrepreneurial autonomy and the insights it provides into factors that potentially affect how business owners experience entrepreneurial autonomy. We then contextualize our study by describing the setting under which Russian business owner/founders operate. We discuss the literature on Russian institutions, culture, and business environment and their implications for entrepreneurial autonomy. We then outline the qualitative research design and methodology, before presenting the findings in Russia and comparing them with those found in the Netherlands. A first contribution of this study is therefore to outline and compare the meanings entrepreneurs attach to autonomy, the factors that affect their experience of autonomy, and the actions they take to attain and retain it. In our discussion section we add three further contributions. Firstly, we generalize the differences between the Netherlands and Russia in terms of the experience of entrepreneurial autonomy to what the World Values Survey describes as cultures of self-expression and survival. Secondly, we theorize from context (Whetten, Reference Whetten2009) by highlighting an underlying similarity between the two settings through a model we develop, which posits the level of experienced autonomy to be a result of the balance between factors affecting power (defined as the ability or capacity to do something or act in a particular way) and dependency (defined as the state of relying on or being controlled by someone or something else) (Oxford Online Dictionary, 2015). Rather than taking a top-down approach and theorizing from institutional theory or cultural dimensions, our approach to theorizing is bottom-up, an approach which, according to recent pleas for context theories and research (Bamberger, Reference Bamberger2008; Michailova, Reference Michailova2011), is as needed as it is scarce. Thirdly, throughout the discussion we outline the relevance of autonomy for entrepreneurial practice and speculate about the effects that the experience of autonomy may have on a variety of economic outcomes.

ENTREPRENEURIAL AUTONOMY

While theorizing about entrepreneurial autonomy is absent from the business literature, significant attention has been given to the autonomy of employees. Historically, autonomy has been investigated in the context of the relationship between employers and their employees, with the focus being on the employees rather than the entrepreneurs/employers. Autonomy was originally studied as a unitary concept (Hackman & Oldham, Reference Hackman and Oldham1975). Later, various forms of autonomy were discerned, including scheduling, method, and criterion autonomy (Breaugh, Reference Breaugh1999). These aspects refer to decision rights regarding when work is done, how it is done, and according to which criteria it is evaluated, respectively. Based on their study of employees working for entrepreneurial firms, Lumpkin et al. (Reference Lumpkin, Cogliser and Schneider2009) further developed the concept of ‘strategic autonomy’, which refers to the freedom for employees to set the strategic direction of the venture. All mentioned forms of autonomy equally apply to business ownership, and autonomy (also labeled as independence or freedom) has been found to be the most commonly listed reason for people to start and run their own venture (Dawson & Henley, Reference Dawson and Henley2012; Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Hart and Drews2015). The promise of freedom brought on by business ownership applies in both developed and developing countries (Sen, Reference Sen1999). Autonomy is not only a dominant entrepreneurial motivation, but also a dominant source of entrepreneurial satisfaction and well-being. Available research shows that business owners rate themselves as having a high degree of work-related autonomy. Although sizeable variation occurs, their high levels of satisfaction compared to their employees can – to a large extent – be explained by the increased level of autonomy they enjoy (Benz & Frey, Reference Benz and Frey2008a, Reference Benz and Frey2008b; Hundley, Reference Hundley2001; Lange, Reference Lange2012; Prottas, Reference Prottas2008; Stephan, Reference Stephan2018).

In spite of its importance, the conceptual treatment of entrepreneurial autonomy has been shallow, with little theorizing pertaining to the construct. Autonomy is loosely associated with independence, freedom, and influence (Lange, Reference Lange2012), as well as taking responsibility (Shane, Locke, & Collins, Reference Shane, Locke and Collins2003), having control (Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Hart and Drews2015), and having flexibility (Edelman et al., Reference Edelman, Brush, Manolova and Greene2010; Jayawarna, Rouse, & Kitching, Reference Jayawarna, Rouse and Kitching2013). When comparisons to employees are made, it is assumed that the measures of ‘job autonomy’ hold equal validity for employees and entrepreneurs (Benz & Frey, Reference Benz and Frey2008b; Prottas, Reference Prottas2008). One of the few studies specifically directed at entrepreneurial autonomy was conducted by Van Gelderen and Jansen (Reference Van Gelderen and Jansen2006), who asked a sample of autonomy-motivated business founders why they wanted autonomy. They found that entrepreneurs desired autonomy at two levels. The first is the intrinsic enjoyment of having decisional freedom with regard to the what, how, and when of executing a venture. The second is the realization of three motives for which autonomy is instrumental, in other words a prerequisite: freedom from constraints (i.e., the absence of a boss or rules), self-endorsement (do one's ‘own thing’), and the exercise of control. The study implies that autonomy does not come automatically with business ownership, as there are numerous challenges associated with each of these autonomy-related motives. For example, having decision rights may be inherently enjoyable, but less so when making decisions with painful consequences; entrepreneurs may have the right to take time off, but nevertheless find themselves working long hours. With regard to the motives for which autonomy is instrumental, instead of working for a boss, the owner must now deal with the demands of clients, employees, and other stakeholders. The business owner may enjoy doing his or her own thing, or doing them in a specific way, but customers may want the business owner to work according to their specifications. The owner may be in control within the firm but may work in an uncertain environment; business partners will want to have their say, and uncertainty about developments in the business environment can be severe. Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016) asked a sample of 61 Dutch entrepreneurs about such challenges and, indeed, found that entrepreneurial autonomy is continuously being negotiated vis-à-vis a variety of stakeholders, and that a range of factors can cause the level of experienced autonomy to increase or decrease. In that study, customers regularly represented a threat to autonomy, whereas business partners were often seen as enhancing autonomy. Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016) also showed that self-endorsement is integral to autonomy; business owner/founders regularly autonomously (by their own volition) decide to temporarily forego their autonomy; this is then meant to be temporary. Therefore, the study concluded that autonomy is not only about currently exercised decisional freedom, but also about whether the current degree of experienced decisional freedom is self-determined.

ENTREPRENEURIAL AUTONOMY IN THE RUSSIAN CONTEXT

As the previous section made clear, no theory of entrepreneurial autonomy currently exists. In the discussion section, we seek to theorize about entrepreneurial autonomy based on our qualitative cross-country comparison. First, in this literature review section, we set out to contextualize our study. Thus, we follow the distinction made by experts of context theory between contextualizing on the one hand, and context theorizing (Bamberger, Reference Bamberger2008), theories of/about context (Whetten, Reference Whetten2009), context-effects theory (Whetten, Reference Whetten2009), or deep contextualizing (Tsui, Reference Tsui2007) on the other hand. Contextualizing is the ‘linking of observations to a set of relevant facts, events or point of view that make possible research and theory that form part of a larger whole’ (Rousseau & Fried, 2001: 1). Context theorizing goes beyond contextualization as it ‘goes beyond the sensitization of theory to possible situational or temporal constraints or boundary conditions by directly specifying the nature and form of influence such factors are likely to have on the phenomenon under investigation’ (Bamberger, Reference Bamberger2008: 842). Bamberger (Reference Bamberger2008) and Michailova (Reference Michailova2011) claim that such theorizing is best done by means of qualitative, comparative studies that proceed from the embedded actions, cognitions, and emotions of social actors in real settings, ‘although such bottom-up context theorizing remains quite rare’ (Bamberger, Reference Bamberger2008: 842). This is what we set out to do in our discussion section. However, we first contextualize our study by reviewing the extant literature on Russian entrepreneurship as it sheds a light on the experience of autonomy of Russian business owners and the factors that affect it. To this end, we now first review the literature on formal institutions, cultural dimensions (informal institutions) and economic conditions. We take a creative step in discussing this literature in terms of implications for individual level autonomy.

A large set of the literature on entrepreneurship in Russia focuses on institutions (Aidis, Estrin, & Mickiewicz, Reference Aidis, Estrin and Mickiewicz2008; Puffer, McCarthy, & Boisot, Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Boisot2010; Puffer, McCarthy, May, Shirokova, & Panibratov, Reference Puffer, McCarthy, May, Shirokova, Panibratov, Grosse and Meyer2018). Institutions are defined as the rules of the game in a society (North, Reference North1990) and include formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include laws and regulations, which promote order and stability by providing guidelines for individual and organizational behavior (Scott, Reference Scott1995). Laws and regulations are explicitly codified and can be enforced and sanctioned (although this does not necessarily always happen). Informal institutions constitute a culturally based and historically enduring set of norms, meanings, and understandings that are shared by a country's inhabitants and shape social cohesion and coordination (Scott, Reference Scott1995). It was through the study of transition economies, such as Russia, that the importance of institutions came to the fore (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2005, Reference Meyer and Peng2016). Studies of entrepreneurship in Western countries have tended to take institutions for granted and leave them out of consideration; in transition economies these are far more than background conditions (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2016).

Starting with formal institutions, in Western economies, entrepreneurial autonomy is facilitated by laws (for example, those relating to property or contracts) that apply to all (rule of law) and are enforced by an independent judiciary. With regard to Russia, by contrast, authors have highlighted: the poor protection of property rights, weak capital market institutions, and corrupt law enforcement and juridical systems (Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011); corruption (Aidis et al., Reference Aidis, Estrin and Mickiewicz2008); violations of the minority shareholder rights (Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011); an increasing lack of a free press that could hold culprits accountable (Rochlitz, Reference Rochlitz2014); and the sense that, under the current situation, Russian entrepreneurs fear bureaucrats more than criminals (Aidis et al., Reference Aidis, Estrin and Mickiewicz2008). The characteristics of formal institutions in Russia, as well as their instability, can generally be seen as undermining autonomy (defined as having venture related decision rights), apart from the autonomy of insiders in entrenched positions. Those who do start and run productive, non-rent seeking ventures spend vast amounts of time fulfilling everyday government requirements and improvising ways to avoid state pressure and administrative measures (Ivy, Reference Ivy2013). This is mostly disempowering for (small) business owners and reduces autonomy with regard to what, how, and when work is done. Furthermore, although the power of criminal groups, and therefore destructive entrepreneurship (Baumol, Reference Baumol1990), has greatly decreased since the 1990s (Yakovlev, Reference Yakovlev2014; Zhuplev & Shtykhno, Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009), rent-seeking entrepreneurship (Baumol, Reference Baumol1990) continues to exist because some entrepreneurs who profited from the first wave of privatization in the 1990s now hold entrenched interests and, motivated by their desire to maximize their continued opportunities to profit from rent-seeking behavior, resist change (Yakovlev, Reference Yakovlev2014; Yakovlev, Sobolev, & Kazun, Reference Yakovlev, Sobolev and Kazun2013). The power held by those insiders comes at the expense of the autonomy of the vast majority of business owners, particularly of newcomers without connections to those with entrenched power.

In sum, the development of formal institutions and the associated indictors of ‘the Ease of Doing Business’ as reported by the World Bank (2016) not only enable (or hinder) business owners from effectively and efficiently engaging in economic transactions, but also fulfill (or frustrate) their realization of the autonomy motive. According to the Heritage Foundation (2015: 5), ‘the idea of economic freedom is to empower people with more opportunity to choose for themselves how to pursue and fulfill their dreams, subject only to the rule of law and honest competition from others’. If economic freedom is equated with a lack of regulation, this would open the door for the infringement of decision rights of business owners by others. Autonomy-enhancing regulation is not absent but efficient, stable, and applicable to all (The Heritage Foundation, 2015).

In the absence of well-functioning formal institutions to support equal opportunities, business owner/founders need to take actions in order to start, run, and grow their businesses. The most important action is to rely on networks, particularly relationships with government officials (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2005; Yakovlev et al., Reference Yakovlev, Sobolev and Kazun2013). Social networks such as these act as substitutes for formal institutional support and, thus, compensate for deficiencies in the formal institutional infrastructure (Ivy, Reference Ivy2013; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, McCarthy and Boisot2010; Smallbone & Welter, Reference Smallbone and Welter2001). Faced with actively involved government agencies, firms must develop both political and market capabilities (Li, Peng, & Macaulay, Reference Li, Peng and Macaulay2013). Utilization of ‘administrative resource’ (Russians use singular rather than plural), or sviazi (Batjargal, Reference Batjargal2007) (the concept of blat (Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2009) is considered outmoded), meaning network linkages in or with the government that facilitate doing business, is vital for mitigating state coercion and interference with commercial affairs and for protecting businesses from extortion and expropriation (Wales, Shirokova, Sokolova, & Stein, Reference Wales, Shirokova, Sokolova and Stein2016; Yukhanaev, Fallon, Baranchenko, & Anisimova, Reference Yukhanaev, Fallon, Baranchenko and Anisimova2015).

The use of networks (sviazi) and administrative resource allows productive ventures to get things done (Ivy, Reference Ivy2013; Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2009), thereby increasing the autonomy of those ventures. However, the use of administrative resource can also come at a price that may reduce autonomy. For example, an administrative resource may negotiate to become a co-owner of the business. The dependence on administrative resource by incumbents may limit the autonomy of newcomers and outsiders. It has been observed that much of the networking activity is not in the ‘productivity-enhancing’ sphere, but in the form of unproductive activities in the ‘control’ sphere (Aidis et al., Reference Aidis, Estrin and Mickiewicz2008). In Russia, networking is often less about getting better knowledge of business partners and their needs and more about pursuing the goal of conspiring against outsiders and avoiding legal control over financial and other transactions (Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2008).

It is generally considered that the characteristics of Russian institutions contribute to low levels of generalized trust (Bjørnskov, Reference Bjørnskov2007; Delhey & Newton, Reference Delhey and Newton2005; Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2008). A lack of generalized trust and the corresponding perception of a hostile business environment push entrepreneurs to substitute networking for market mechanisms. This results in the creation of trustworthy inner circles that entrepreneurs rely on to protect against potentially harmful outsiders. Moreover, this lack of trust has decreased transparency in business dealings (McCarthy & Puffer, Reference McCarthy and Puffer2013). In the past, some firms that were more transparent in order to raise capital became victims of predators who used company information to take over their assets (Puffer & McCarthy, Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011). Overall, this distrust challenges autonomy if it generates suspicions that others are out to violate or steal decision rights.

In addition to the formal regulatory environment, informal networks, and distrust, research has also focused on Russia's cultural dimensions, particularly using Hofstede's dimensions. Russia scores very high on power distance (93 out of 100) and uncertainty avoidance (95 out of 100) (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2016; McCarthy & Puffer, Reference McCarthy and Puffer2013). Within a firm, according to Puffer and McCarthy (Reference Puffer and McCarthy2011) and Saidov (Reference Saidov2014), the high-power distance dimension results in a tendency to adopt an authoritarian leadership style. Power distance and uncertainty avoidance, combined, may also propel employees to accept limitations to their autonomy. This is confirmed by the results of the GLOBE study (Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges, Dastmalchian, & House, Reference Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges, Dastmalchian and House2012), in which Russian leadership scored high on autonomous behavior and low on participative and humanistic approaches. Another cultural dimension on which Russia scores exceptionally high is particularism (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, Reference Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner2012; Voldnes, Grønhaug, & Sogn-Grundvåg, Reference Voldnes, Grønhaug and Sogn-Grundvåg2014), meaning situations are assessed on a case-by-case basis and that different rules apply to different contexts. This cultural dimension fits well with the effects of Russia's formal institutions; deficiencies and instability in the rule of law, as well as the lack of a level playing field, are more easily accepted and managed by decisions made on a case-by-case basis. As a result, autonomy is optimized in a flexible manner rather than in one following consistent rules.

Autonomy is also affected by current economic conditions, which are often challenging for small-scale Russian business owners, who are vulnerable because of their general lack of resources. They must cope with macroeconomic uncertainty and changing governmental policies. In late 2014, the global economy experienced a more than 60 percent drop in the price of oil – the main source of income for the Russian state budget. On top of this, economic sanctions were imposed on Russia, leading to an embargo which restricted trade of a wide range of products between Russia and a number of countries. Dependent on imports of finished goods and exports of raw materials, economic growth slowed, the national currency devaluated by nearly 50 percent, and the levels of inflation and unemployment increased; all factors which had particularly negative effects on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and, ultimately, led to a greater number of their bankruptcies (Federal State Statistics Service, 2016). This could mean that autonomy concerns have to take a backseat to mere economic survival and that the notion of autonomy takes on a different meaning. At the same time, Yakovlev et al. (Reference Yakovlev, Sobolev and Kazun2013) noted that the reduction in oil prices and international sanctions have since motivated Russian leadership to strengthen the small business sector, to compensate for the reduction in income streams derived from mineral resources. Indeed, the Russian federal government has increasingly acknowledged the importance of entrepreneurship and a thriving small business sector and has taken steps to strengthen the formal institutions and improve the business climate (Kremlin, 2015; Yakovlev, Reference Yakovlev2014; Yukhanaev et al., Reference Yukhanaev, Fallon, Baranchenko and Anisimova2015), which has thus increased the autonomy of business owners.

In sum, the existing literature strongly suggests that significant challenges to individual business owners’ autonomy exist. This, however, does not mean Russian business owners are not autonomous, or do not want to be. As our findings will show, they take active steps to attain and retain autonomy. Given the institutional, cultural, and economic conditions sketched above, we investigate the factors determining how business owners experience autonomy, as well as the meaning of autonomy in Russia. This will allow us to provide an account of both the unique features of the Russian and Dutch experience of autonomy, and their underlying similar structures (Tsang & Kwan, Reference Tsang and Kwan1999).

METHODS

This research provides an empirical generalization of the research of Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016) by studying the relationship between entrepreneurship and autonomy in Russia and comparing the findings with the Netherlands. Such studies help to establish the range of applicability and generalizability of the original research results to new contexts (Bettis et al., Reference Bettis, Helfat and Shaver2016). In this study we followed, as closely as possible, the methodology of the original study (Van Gelderen, Reference Van Gelderen2016) in relation to research design, data collection, measurement, and data analysis. Yet, as discussed below, some variations were made to account for the peculiarities of the Russian research context (Singh, Ang, & Leong, Reference Singh, Ang and Leong2003). The research design utilizes a qualitative methodology. Thirty-two Russian owner/founders of businesses were shown very small case studies (vignettes) depicting autonomy-related tensions to elicit their own experiences. We critically compare the responses of the Russian participants with the responses of the 61 Dutch owner/founders investigated in the original study (Van Gelderen, Reference Van Gelderen2016).

Sample

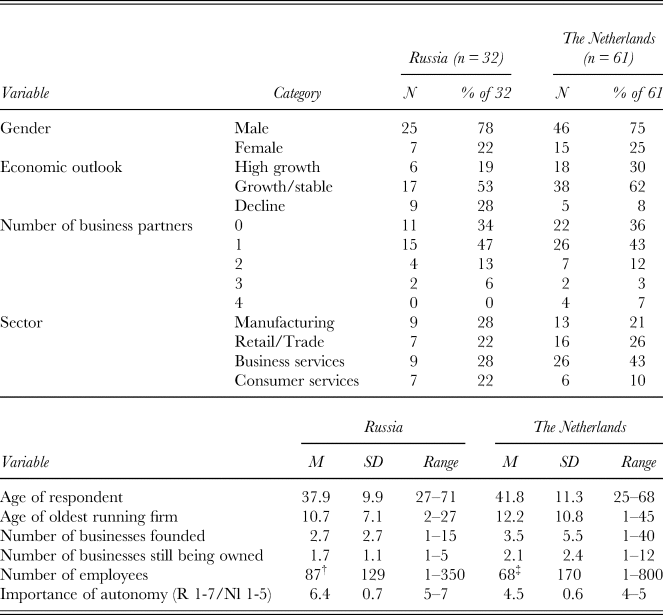

Using theoretical sampling, respondents were drawn from the extensive networks of Russian professors and were primarily based in St. Petersburg. In Russia, it is ineffective to approach random businesses from public registers as business owners tend to be suspicious of outsiders, particularly those who request information (Shirokova, Vega, & Sokolova, Reference Shirokova, Vega and Sokolova2013; Voldnes et al., Reference Voldnes, Grønhaug and Sogn-Grundvåg2014). Even though they were recruited from personal networks, some participants continued to wonder why certain interview questions were asked and what the purpose of the study was. So, to assuage these concerns, anonymity and confidentiality were assured. The sampling framework in the Dutch study is described in more detail by Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016). Descriptive statistics for the two samples are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive sample statistics

Note: Excluding large businesses with †2000 and ‡ 6000 and 6500 employees, respectively

The samples show no significant differences in terms of their characteristics, although tests have low statistical power because of the limited sample sizes. Data in the Netherlands were collected from 2013–2015 and in Russia from 2015–2016. The samples consist of business owner/founders with sizeable variation in the age of the participant, age of the business, business experience, firm size, sector, and current financial performance. This allowed us to analyze the experience of autonomy across a variety of settings and conditions. Furthermore, the business owners had to own at least one independent business that employed at least one employee. For business owners who are self-employed without employees (freelancers), autonomy considerations may also be of concern, but they are likely of a qualitatively different nature and are therefore not considered in this study. Finally, we asked all respondents to rate the importance of autonomy, and only those who considered autonomy as important were included in the sample, as we did not expect those unmotivated by autonomy to have stories about their actions to attain and retain autonomy. Nevertheless, only one Russian business owner found autonomy unimportant and was consequently excluded (three owners were excluded for this reason in the Netherlands). Thus, the study does not investigate variations in the level of importance attached to autonomy and all participants can be considered as motivated by autonomy. In other words, no variation in autonomy as trait, motive, or need is studied. All participants were interviewed face-to-face and the interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Data Collection

Responses about how business owners experience autonomy, its development over time, and the factors that affect the experience and its changes were elicited in different ways. First, we asked each respondent what ‘autonomy’ meant to them. We then used 10 vignettes to elicit responses about their experience of autonomy (see Table 2). Each vignette is a mini-case study depicting autonomy-related tensions and challenges, based on the types distinguished by Van Gelderen and Jansen (Reference Van Gelderen and Jansen2006): intrinsic enjoyment of decision rights and the three motives for which autonomy is instrumental: the absence of a boss or rules, self-endorsement (do one's ‘own thing’), and having control. Participants were asked to respond to the vignette by stating whether they had encountered such a situation, what their actions were, and to elaborate further with their own examples. Vignettes were used because autonomy is an abstract concept and they illustrated concrete tensions and challenges, which helped participants think about their own autonomy-related experiences and responses. These experiences may have taken place at any point in the participants’ business careers. The vignettes helped participants to recall emotionally charged experiences and to think visually, as advocated by proponents of context research (Shapiro, Von Glinow, & Xiao, Reference Shapiro, Von Glinow and Xiao2007). Hence, the design is retrospective, rather than prospective or based on an experience sampling methodology.

Table 2. Vignettes describing autonomy-related challenges

Note: A = Intrinsic enjoyment of autonomy; B = Avoiding a boss; C = Self-expression; D = Control.

The vignettes were originally written in the third person (for the vignette descriptions in the third person, see Van Gelderen, Reference Van Gelderen2016). Although this approach worked well in the Netherlands, the Russian business owners often focused on the specifics of the case laid out in front of them, rather than generalizing the issue and discussing their own experiences. This may be a reflection of the cultural dimension of particularism versus universalism, with Russia scoring high on particularism and the Netherlands scoring high on universalism (Trompenaars & Hampden-Turner, Reference Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner2012; Voldnes et al., Reference Voldnes, Grønhaug and Sogn-Grundvåg2014). Therefore, in the Russian study we designed a modified protocol in which vignettes were formulated in the second person instead of the third person. Apart from changing the protagonist, the content remained mostly identical; yet, because of the references in the literature to extortion and bribes in Russia (Aidis et al., Reference Aidis, Estrin and Mickiewicz2008; McCarthy & Puffer, Reference McCarthy and Puffer2013; Rochlitz, Reference Rochlitz2014), all of which could potentially affect entrepreneurial autonomy, we replaced a generic vignette about bureaucracy used in the Dutch study with two new vignettes relating to extortion and bribery (vignettes 9 and 10 in Table 2). Finally, and similar as in the original study, the owner/founders were asked to draw graphs projecting their degree of experienced autonomy over time. In the interview, each inflection point on the graph is investigated to understand why a change took place. Back translation procedures were followed.

Thematic Analysis Procedures

As in the Dutch study, the results were coded by means of the thematic analysis procedures outlined by Guest, MacQueen, and Namey (Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey2012) and Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Thematic analysis is a qualitative technique for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) in data that does not involve counting phrases or words as is done in content analysis. In the first step, any factor related to the experience of autonomy and its development over time is provided a code. Codes refer to ‘the most basic segment, or element, of the raw data or information that can be assessed in a meaningful way regarding the phenomenon’ (Boyatzis, Reference Boyatzis1998: 63). This first-order code is always literally drawn from the text and does not involve an interpretation or evaluation. Then, the first-order codes are grouped together at a higher level of abstraction based on similarities in content, and this process is repeated until a limited number of higher-order codes emerge, which can then be labeled as themes.

The interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed in Russian, and then translated into English for analysis by both Russian and international research team members. As strongly recommended in the literature on comparative studies of context (Meyer, Reference Meyer2014; Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Von Glinow and Xiao2007; Whetten, Reference Whetten2009), our research team consisted of multiple nationalities, including three local, Russian researchers. Context is easily missed or misinterpreted, both by ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’. Insiders may be so entrenched that it is difficult for them to capture influences other than those commonly acknowledged. Outsiders, on the other hand, may lack the intimate knowledge needed to thoroughly assess the local situation. The latter is particularly the case in research conducted in ‘high context cultures’, (Hall, Reference Hall1976) such as Russia, where meaning is more often derived from surrounding cues than from spoken or written words (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009: 139; Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, Von Glinow and Xiao2007). The entire team collaborated in all phases of the research, including research and method design. With respect to coding and in following the procedures for ‘investigator triangulation’, (Denzin, Reference Denzin1989) each interview was independently coded by at least three researchers using the pen and paper approach. Every paragraph in every interview was then discussed in detail in order to clarify the meaning and interpretation of the autonomy related-experiences described by the participants. This procedure led to numerous clarifications and coding refinements and also made both the local and international members aware of assumptions and biases. A process of consensual coding (Guest et al., Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey2012) was employed to resolve disagreements over codes.

A spreadsheet of codes was created with the codes identified for each interview. The codes were then analyzed, sorted, and aggregated to search for patterns, or themes, within the data. The themes were identified in an inductive or ‘bottom up’ way and were strongly linked to the data itself. A theme, formulated as a phrase or sentence, identifies ‘what a unit of data is about and/or what it means’ (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009: 139). Theme identification is initially approached by asking, ‘What is s/he saying here’? and evaluating the relevance of what is said to the research objectives, which frame how the text is viewed and determine which themes are worth defining. One of the most common theme recognition techniques is repetition – a concept consistently recurring throughout transcripts is likely a theme (Guest et al., Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey2012). With thematic analysis, the researcher continues to go back and forth between codes and data; if themes are identified, the interviews are coded again to determine whether pieces of information were overlooked, and, particularly, to see whether evidence which contradicts a theme can be found (deviant case analysis, Guest et al., Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey2012).

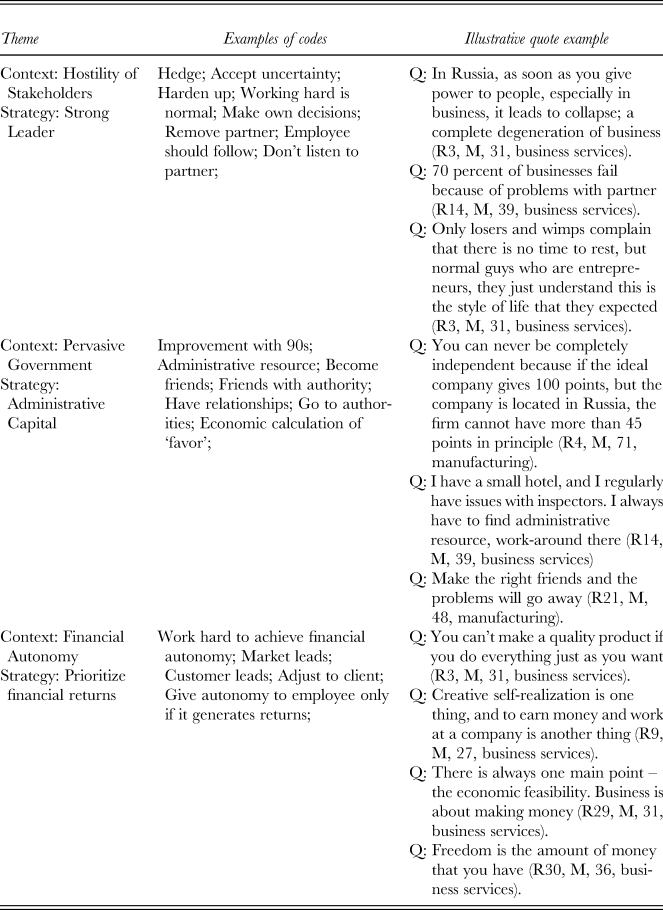

While thematic analysis is well-suited for inductive and exploratory research designs, it is imperative that the themes are not obviously stated in to the questions posed to the respondents; if they are, the analysis would be trivial and unlikely to establish previously unidentified patterns (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). In this study, this pitfall is prevented by the vignette-based methodology, which encourages respondents to share firsthand stories of their experiences, which were the only part of the responses that were coded. The themes, examples of codes, and illustrative quote examples are provided in Table 3 and discussed in more detail in the results section.

Table 3. Themes, codes, and quote examples

RESULTS

This study investigates how 32 Russian business owners experience autonomy, as well as the conditions, circumstances, and individual actions of the entrepreneurs that affect their autonomy. Three themes emerge from the data, each of which is split into a contextual element and a corresponding strategy aimed to further autonomy (Table 3). The themes are: (1) the perceived hostility of the business environment and of stakeholders, which elicits a forceful, powerful leadership style; (2) the pervasiveness of the government, which requires the development of so-called ‘administrative resource’, or sviazi (network linkages in or with the government that facilitate doing business); and (3) the focus on autonomy in a financial sense (financial freedom), which entails the prioritization of financial considerations. Throughout our findings section, we compare these three themes with the experience of autonomy of the sample of 61 business owners in the Netherlands, as reported by Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016).

In terms of prevalence, the first and second theme emerged in the 23 out of the 32 cases, while the third theme appeared in 29. Thus, there are several exceptions to each theme. Moreover, deviant case analysis uncovered contradictory findings to each theme, such as an owner who ‘had a passion for bureaucracy’ (Respondent 13, male, age 52, trade). As a consequence, the findings with regard to both the Russian and Dutch themes should be understood as relative rather than absolute, similar to the results of most quantitative studies. Also, the contexts of hostility, government pervasiveness, and financial autonomy, as well as the corresponding strategies business owners adopt to navigate them, are not necessarily encountered every hour of the work day or even every day; however, they are mentioned in the interviews as factors affecting how business owners experience autonomy.

Theme 1 – Hostile Environment

The hostility and corresponding distrust of stakeholders (customers, competitors, suppliers, financers, employees, and the government [the role of the government will be further discussed under Theme 2]) is a significant theme among Russian business owners. In particular, the topic of business partners gave rise to many negative responses. The Dutch respondents often see business partners as furthering autonomy, explaining that having a business partner doesn't infringe upon individual autonomy, but instead enhances decision-making. On the other hand, most Russian respondents see co-ownership as something that should be avoided, claiming co-owners cheat and cannot be trusted. Some even discussed having tried it in the past, but explained it was full of conflict, which ultimately led to dissolution of the partnership. For example, one respondent went as far as to state that, ‘In Russia, 70 percent of businesses fail because of problems with partners’ (R14, M, 39, business services). Another owner/founder said, ‘If there is a possibility to do your own business, you should do your business. Partnerships generate a lot of problems, but very often it is impossible to do it alone’ (R 28, M, 34, trade). Given the negativity expressed, it may be surprising that the percentage of solo-owned Russian businesses is not higher than in the Netherlands (Table 1). One reason for this is that some business partners, due to the administrative capital they directly or indirectly represent, force themselves into ownership positions (see next theme).

Some of the negativity is related to external business partners, such as clients, suppliers or other businesses they work together with, or have at least tried to work together with. As one owner proclaimed, ‘Clients dictate their terms to you, and the reason why they do it is to make you disappear. They will eviscerate you, and that's all’ (R22, M, 48, consumer services). While the literature reports that there is little generalized trust in the Russian business environment, one would expect trust to be reserved for those inside the company; however, insiders (employees and fellow owners) are sometimes also seen as untrustworthy. Conversely, some outsiders are trusted even more than insiders; several participants commented that they prefer to work with Western companies who, aside from providing a degree of protection from hostile elements in the business environment (also see theme 2), are seen as more reliable.

In response to this perceived hostility of stakeholders, most Russian business owners protect their autonomy by adopting a powerful stance, including toward their employees. Whereas the Dutch leadership style tends to be more participative, with Dutch business owners being far more likely to appreciate independent attitudes, provide autonomy to employees, and adapt their management approach to make such individuals more productive, Russian business owners are suspicious of this style and tend to take on a more authoritarian approach, as is noted in the literature (McCarthy & Puffer, Reference McCarthy and Puffer2013; Saidov, Reference Saidov2014). As one Russian respondent illustrates, ‘In Russia, as soon as you give power to people, especially in business, it leads to collapse, a complete degeneration of business’ (R3, M, 31, business services). A similar sentiment is expressed by another owner/founder, who said, ‘The constant adoption of individual decisions definitely leads to a collapse, and very quickly’ (R28, M, 34, trade). A next one added, ‘To work effectively, one needs a team that will obey’ (R10, F, 28, consumer services). On top of this general feeling of distrust, a lack of powerful unions and weak labor law protections for employees, as well as the greater cultural acceptance of power distance in Russia, also make it possible for Russian business owners to employ an authoritative style. This may be accepted by both sides because of the greater acceptance of power distance in Russia (Dorfman et al., Reference Dorfman, Javidan, Hanges, Dastmalchian and House2012; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2016). Even if employees are involved in decision-making, it may not result in success: ‘You want someone to argue with you. You may try it with an employee, but it is difficult in Russia in business. They all say, “Yes, it's okay”’ (R31, M, 36, consumer services). Just one Russian respondent observed that, by restricting the autonomy of employees, and making all decisions themselves, the boss eventually restricts his or her own autonomy, for example, by always having to be present. A few respondents mentioned they would accept the employees’ need for autonomy only if it would earn them financial returns, which underscores the importance of financial autonomy (Theme 3).

The tough attitude of Russian entrepreneurs also emerges in response to the vignette about being able to decide your own work schedule but finding yourself working nearly all the time. Dutch business owners tend to see this as an undesirable situation in which steps, such as outsourcing, delegating, or working more efficiently, need to be taken to avoid having to work so many hours. However, with a few exceptions, the Russian business owners see this as an irrelevant issue, viewing 80- to 100-hour workweeks as part of being a business owner. Those who complain about it should ask themselves whether they are fit to run a business. ‘A normal business man does not count work hours’, said one owner (R30, M, 36, business services) and a second stated, ‘He is a big boy and has to understand that if he earns money, the compensation of his freedom is in the monetary equivalent’ (R23, M, 30, manufacturing). Furthermore, being present at work also helps one stay in control: ‘An option is to hire a manager, go live in the Seychelles, and just receive money. But there is always the possibility that you can be deceived; this is Russia’ (R29, M, 31, business services). This attitude toward taking time off can be seen as an expression of low indulgence – a dimension on which Russia scores low (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2016).

Theme 2 – Pervasive Government

One respondent made the following statement, ‘You can never be completely independent, which is understandable, because…suppose my company is the ideal one, for 100 points, but the company is located in Russia, which, say, gives 45 points. So the company cannot have more than 45 points in principle, because there exists a certain limit’ (R4, M, 71, manufacturing). This business owner refers to the pervasive presence of the state. One business owner/founder even defines autonomy as having no connection or affiliation with government structures and depending entirely on the market. How can business owners be autonomous if the state is so pervasive in so many areas of business life? The solution is to develop so-called ‘administrative resource’ or administrative capital.

Adding to the theme of hostility (theme 1), the government is regularly referred to as hostile and can represent a powerful foe, although many Russian entrepreneurs comment that if the business is small, it is less likely to be hassled. Moreover, several respondents state that the situation has improved significantly since the 1990s, during which time criminals often engaged in practices of extortion and corporate raids. As one owner commented, ‘In general, it seems, it is better now than in the ‘90s, although I do not know for sure how this took its course; I was a child then. As far as I know, thugs do not come straightforward now, everything has become civilized – but still everyone pays the money’. (R31, M, 36, consumer services). A second one adds, ‘Now all these bandits have certificates of deputies, helpmates, and representatives from a number of organizations – department for combating economic crime, special task police squad, fire-fighting service, migration service, etc. They are numerous…[but] there is always some method of influence – friends who may help, if anything. Everyone has faced this probably in a different way’ (R30, M, 36, business services). As the last quote indicates, Russian entrepreneurs rely on ‘friends’ or administrative resources within the government to help protect them from such practices. The following quotes illustrate the importance of networks: ‘I have a good partner, who is now well known; he helps me a lot. Otherwise, I would simply be slammed’ (R22, M, 48, consumer services); ‘Best of all is to have friends in all areas, including investigative authorities’ (R3, M, 31, business services); and ‘Make the right friends, and the problem will go away’ (R21, M, 48, manufacturing). Several business owners stated that they would report extortion to the authorities. However, one owner advises, ‘If these people are like gangsters, then contact the law enforcement agencies. If these people are from the law enforcement agencies, it is better to agree’ (R24, M, 32, business services). Thus, the use of administrative resources can both enhance and limit autonomy, as it can increase one's decisional freedom, but something will often be asked for in return, including, sometimes, shared ownership. Actually, one does not even need to have friends or a network, as an industry of consultants or mediators with good connections to the governmental agencies has sprung up, who can be hired if needed. Finding protection through administrative resource is seen as a better option than giving in to extortion. As one respondent explained, ‘One always has to fight, especially with such people, and actually with all the people. If you give a bit away, everything else will be taken from you’ (R14, M, 39, business services). One owner sees opportunities: ‘You can also make good relations with this extortion group. If they are powerful people, you can even take advantage of it’ (R27, M, 31, manufacturing). However, as one respondent observed: ‘Autonomy is always high if your business is not related only to the sales based on the administrative resource, which can disappear at some point and that's all’ (R14, M, 39, business services).

Much more common than extortion is bribery. As one business owner says, ‘Doing everything according to the law is, in a sense, impossible in Russia’ (R3, M, 31, business services). Another adds that, ‘the severity of Russian laws is compensated by the optionality of their performance’ (R28, M, 34, trade). The literature reports that it is common for Russian business owners to give bribes (Djankov, Roland, Miguel, Zhuravskaya, & Qian, Reference Djankov, Roland, Miguel, Zhuravskaya and Qian2005; Zhuplev & Shtykhno, Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009). At the same time, Zhuplev and Shtykhno (Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009) report that only 17 percent of the respondents identified corruption as a major constraint. This suggests that bribery may be perceived as a normal business practice. Our study confirms this picture; one owner said, ‘If there was something to bribe for and someone to bribe, I certainly would…it's Russia’ (R13, M, 52, trade). Another reported, ‘I live in Russia…here I follow the rules of the game; that is, if you can get something not quite legally, then yes, I always do it because it is easier [and more] cost-effective. I do not see the harm’ (R5, F, 47, retail). Nonetheless, many respondents stated they prefer to use terms other than ‘bribe’, such as ‘work around’ or ‘to get a person interested in order to let him be happy’. One entrepreneur stated, ‘Well, it is not a bribe exactly, everything is more complicated. It is not that you come and say, “Here, take some money”, of course not. It turns out that someone is making (something possible) during 712 days, and someone during 30 days in terms of the same contract. Of course, it is more profitable for me to pay, because the money will come back to me in a month already, not in 20 months’ (R15, M, 37, construction). Apart from resistance to the term bribe, the quote also indicates that Russian business owners see the use of bribes as an economic trade-off. One owner reported, ‘This is a normal business challenge and should be correctly calculated’ (R3, M, 31, business services). Another one said, ‘Any bribe is considered in terms of risk and return. It is not a question of ethics; it is a question of business’ (R7, M, 28, consumer services). Thus, the use of bribes (or whatever term is used) serves to enhance autonomy if employed in the context of pursuing opportunities or serves to mitigate losses to autonomy if used in the context of extortion. As noted by Ivy (Reference Ivy2013), the business owner is not a passive victim; they instead can have leverage by means of supporting those representing administrative capital by pursuing mutual benefits. Ivy (Reference Ivy2013) explains that such a choice is rational, instrumental, and based on an expectation of future benefits that businesses could receive from these particular state representatives in exchange for the support that SMEs provide.

The government is nearly absent from the interviews with the Dutch entrepreneurs, who, in spite of media reports about bureaucracy, rarely refer to the government as restricting freedom in response to a vignette about governmental regulations. Instead, they believe that, although certainly not pleasant, it is necessary that certain rules are in place and (uniformly) enforced.

Theme 3 – Financial Autonomy

For Russian business owners, although autonomy is primarily understood as independence, our participants quickly pointed out that a business owner depends on others. When they shared their experiences related to autonomy-related challenges to the exercise of their decision rights, financial considerations came up as having top priority. Ultimately, we found autonomy, in the Russian context, to mean financial independence. When asked to chart their experience of autonomy over time, the level of autonomy usually corresponded directly with financial performance. ‘Freedom is the amount of money that you have’, said one participant (R30, M, 36, business services) and ‘The availability of money is the tool for independence’, added another (R22, M, 48, consumer services). This is in line with the study by Zhuplev and Shtykhno (Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009), who found that ‘making money to become wealthy and ensure security’, was the top-ranked motivation for becoming an entrepreneur. This focus on material security is understandable in the context of an institutional and economic environment that is perceived as unstable, hostile and where generalized trust is low (Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2008; Yakovlev et al., Reference Yakovlev, Sobolev and Kazun2013). Additionally, it provides another explanation for working long hours (Theme 1) – working these hours is worth it if it contributes to achieving financial independence. Moreover, the lack of capital and high interest rates are listed as the most significant barrier for Russian business owners (Molz, Tabbaa, & Totskaya, Reference Molz, Tabbaa and Totskaya2009; Yukhanaev et al., Reference Yukhanaev, Fallon, Baranchenko and Anisimova2015). This may force them to reinvest profits rather than to rely on loans, which further necessitates the generation of profit (Estrin, Meyer, & Bytchkova, Reference Estrin, Meyer, Bytchkova, Casson, Yeung, Basu and Wadeson2006). There is also sizeable capital outflow out of Russia, again in pursuit of material security (Yukhanaev et al., Reference Yukhanaev, Fallon, Baranchenko and Anisimova2015).

The focus on financial autonomy in an unstable, hostile environment leads to a short-term orientation. One business owner said: ‘Our market is so unpredictable, it is difficult to predict in which direction it goes’ (R12, F, 38, construction). Another stated: ‘You start to do something, but the law changes … to diametrically opposite. What you did becomes irrelevant’ (R1, M, 54, retail). It also detracts from innovation, as can be seen in responses to the vignette (v5) in which someone has an innovation that has not yet attracted interest from paying customers. Some of the Russian business owners either feel that this person should do away with the innovation entirely, as the market shows no interest, or change the product or service so that it does. One Russian entrepreneur said, ‘Why horse around with this nonsense? Who is going to believe you’? (R4, M, 71, manufacturing). Another one added, ‘I am against this, I do not understand it. How can it be that you have created [a product] that is not needed by anyone’? (R5, F, 47, retail). On the other hand, a sizeable number of both Dutch and Russian business owners felt that this entrepreneur should continue pushing the product or service, by stepping up marketing or consumer education efforts to persuade the customers or clients. However, the two groups provided different rationale for doing this. The Dutch respondents recommended better marketing in order to follow one's dream, while their Russian counterparts emphasized better marketing in order to earn money. The primacy of financial considerations comes to the fore when relaying experiences with customers who make difficult or demanding requests or ask to deliver a substandard product. A vast majority of Russian owners believe that one should comply. ‘You can't make a quality product if you do everything just as you want’, explained one respondent (R3, M, 31, business services). ‘There is no other option. The market is difficult today. When a person brings you money, yes, you have to take it’, said another (R15, M, 37, construction). One respondent stated, ‘I came across those customers who dictate how to do things, but business is business. We'll have to put up with it’ (R10, F, 28, consumer services). This quote shows that Russian owners tend to relinquish decision rights to customers if it serves financial goals. A similar sentiment is expressed in the following: ‘If they are income-generating customers, you will be motivated to find a common ground with them and take that dictatorship easy’ (R25, F, 27, consumer services). A Russian owner concluded, ‘The creative self-realization is one thing, and to earn money and work at a company is another thing’ (R9, M, 27, business services).

Conversely, the majority of the Dutch owners feel that business owners should uphold their standards, as this is what autonomy is about; plus, many believe that agreeing to do substandard work will also eventually harm the business because of how it might negatively affect the business’ reputation. In the Netherlands, autonomy is seen as being separate from financial gains, as can be understood from Van Gelderen and Jansen (Reference Van Gelderen and Jansen2006), in which only a few business starters mentioned financial autonomy. Instead, they found that most Dutch business owners, while also motivated by financial considerations, will either forego financial returns altogether or aim to sacrifice their autonomy temporarily when financial and autonomy motivations conflict. When temporarily relinquishing their autonomy, Dutch business owners hope to regain it after finishing an assignment or project that merely raised money or was instrumental for future success. Van Gelderen (Reference Van Gelderen2016) labeled this pattern in the development of autonomy over time as ‘temporary sacrifice’– a pattern absent in the Russian study. In other words, financial success in the Netherlands is seen as instrumental in the service of autonomy, whereas in Russia financial success is directly equated to autonomy. For Russian entrepreneurs, when depicting their experienced level of autonomy over time, the scores have a direct positive relationship with financial performance. Furthermore, one conundrum for Russian business owners is that they associate autonomy with financial success, yet some mention that financial success potentially attracts unwanted attention from extortionists, which may result in challenges to their autonomy.

DISCUSSION

This study provides further evidence that autonomy does not automatically arise when one becomes a business owner. As one Russian entrepreneur stated, ‘This is Russia. The autonomy scale runs from 0 to 45 rather than from 0 to 100’ (R4, M 71, manufacturing). Still, having decisional freedom was considered important by nearly everyone approached to participate in the study, with only one Russian respondent excluded. Both Dutch and Russian entrepreneurs understand that autonomy is, necessarily, relative. Both understand that business owners always deal with a variety of stakeholders and that there will be interdependencies. However, the study establishes that the themes associated with autonomy are markedly different in both countries. Different factors in the two countries impact how business owners experience autonomy, and autonomy is valued for different reasons in the two settings. Some strategies to achieve autonomy are even diametrically opposed in the two countries. That our study reveals differences between Russia and the Netherlands will not come as a surprise. Yet, our study contributes to the literature by means of the explanations of the patterns we uncovered. First, we will generalize the differences in themes between the two countries by incorporating the distinction of the World Values Survey (2016) between survival- and self-expression cultures. Second, we will explore the underlying similarity in structure by positing that, in both contexts, the level of experienced autonomy depends on entrepreneurs’ attempts to optimize autonomy by increasing power and reducing dependencies. We also discuss implications for the practice of entrepreneurs by outlining the potential up- and downsides of each autonomy-enhancing tactic, and the relevance of individual-level entrepreneurial autonomy for the wider economy.

Survival versus Self-Expression

In Russia, reducing one's vulnerability in a hostile, intrusive, and low-trust environment by means of a forceful leadership stance, administrative resource, and focus on financial returns means that autonomy is concerned with negative freedom, or freedom from interference with decision rights. In the Netherlands, by contrast, autonomy can be understood as positive freedom, or freedom to act on opportunities in line with self-endorsed beliefs and values. The distinction between negative and positive freedom (cf. Fromm, Reference Fromm1941) corresponds strikingly to a distinction made by the World Values Survey research project (WVS, 2016) between survival and self-expression values. The World Values Survey (www.worldvaluessurvey.org) is a global network of social scientists studying changing values and their impact on social and political life. Its annual survey has been conducted in almost 100 countries since it began in 1981. The WVS scores Russia high on survival values, which place an emphasis on economic and physical security. The Netherlands scores high on self-expression values, which place liberty over security. Thus, autonomy mostly serves survival in Russia and self-expression in the Netherlands. When the focus is on survival in a hostile business environment, as is the case in Russia, autonomy primarily refers to financial independence and security. The WVS (2016) links survival values not only to the prioritization of economic and physical security, but also to low levels of generalized trust, which was evident in the responses of our Russian participants. Conversely, self-expression values are characterized by trust and tolerance of outsiders.

The differences in values also reflect socio-economic conditions; Russians have to navigate a much more difficult business environment than the Dutch. The WVS initiator, Ronald Inglehart, explains the development of self-expression or survival values as a function of the conditions one grows up in (the scarcity and socialization hypotheses, Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977; Reference Inglehart, Dalton and Klingeman2007). Material sustenance and physical security are immediately linked with survival, and when they are scarce people give top priority to these ‘materialistic’ goals. In the Netherlands, physical and economic security have been ubiquitous throughout the second half of the 20th century, enabling what Inglehart refers to as ‘a post-materialistic culture’ that emphasizes self-expression. Russia, in contrast, has faced a much more uncertain environment and has therefore emphasized survival values geared towards materialism. The scarcity and socialization hypotheses point to the importance of the temporal context. According to Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1977, Reference Inglehart, Dalton and Klingeman2007), one's basic values reflect the conditions that prevailed during one's pre-adult years and change mainly through intergenerational population replacement. As a result, the differences between the two contexts may change over time. According to Peng (Reference Peng2003), transforming economies may move from network-based institutions to rule-based institutions. So, in other words, if the economy of Russia develops further, or if the economic situation of the Netherlands deteriorates, their two conceptions of autonomy may start to converge.

The way autonomy is understood and experienced in different cultures is likely to have economic implications. The forceful leadership, administrative resource, and a focus on financial autonomy characteristic of a survival culture are likely to deter some from starting their own venture. Indeed, levels of actual and aspiring business ownership in Russia are very low by international standards (AGER, 2016; GEM, 2017; Zhuplev & Shtykhno, Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009). Those who do start may prefer immediate profitability rather than uncertain long-term ones, which detracts from innovation (Kravchenko, Kuznetsova, Yusupova, Jithendranathan, Lundsten, & Shemyakin, Reference Kravchenko, Kuznetsova, Yusupova, Jithendranathan, Lundsten and Shemyakin2015; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2005), in spite of Russian business owners being better educated and having higher IQs than non-business owners (Djankov et al., Reference Djankov, Roland, Miguel, Zhuravskaya and Qian2005). Also, existing SMEs are relatively large, as the SMEs that do exist must achieve a certain threshold of strength in order to survive (Zhuplev & Shtykhno, Reference Zhuplev and Shtykhno2009).

In contrast, in the Netherlands, the rule of law, the protection of contract and property rights, an independent judiciary, and a transparent and stable economic environment all enable initially weak and powerless actors to be successful, cultivating a start-up culture (Ireland et al., Reference Ireland, Tihanyi and Webb2008; Kuznetsov & Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova2008). However, the focus on self-expression may explain why the vast majority of business starters lack the desire to grow and prefer to stay small (Van Gelderen, Thurik, & Bosma, Reference Van Gelderen, Thurik and Bosma2005). Instead of seeing financial success and firm growth as promoting autonomy because of the ability to delegate and to work on preferred work tasks, most view firm growth as decreasing autonomy because of the increased responsibilities and decision rights of stakeholders, a finding also encountered in Sweden (Wiklund et al., Reference Wiklund, Davidsson and Delmar2003).

Power and Dependencies

The job demand–control model (Karasek, Reference Karasek1979) and the job demand–resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007) explain the experienced level of stress of employees (with job autonomy figuring as a job resource). Somewhat similarly, we propose a power-dependency model, which explains the level of experienced autonomy to be a result of a balance between factors affecting power (defined as the ability or capacity to do something or act in a particular way) and dependency (defined as the state of relying on or being controlled by someone or something else) (Oxford Online Dictionary, 2015). Our power-dependency model posits that the level of experienced autonomy is a balance of the power one has over others, versus the powers that others have over the entrepreneur. This underlying structure (Tsang & Kwan, Reference Tsang and Kwan1999) is the same in both settings, but the means to increase power or to reduce dependencies differ.

The second column in Table 4 provides an overview of the actions taken by Dutch and Russian business owners to increase autonomy, with power increases being translated as ‘having more’ and dependency reductions as ‘needing less’. In both countries entrepreneurial practice is significantly affected by autonomy concerns. A purely financial point of view cannot explain the resistance against well paying customers in the Netherlands, or against administrative resources who enhance profit and turnover in return for ownership positions in Russia. The third column in Table 4 conveys that the actions taken to increase power or reduce dependencies do not necessarily result in a net autonomy gain. They can potentially lead to reductions in autonomy, which further conveys the overall finding that autonomy is not guaranteed even if actively pursued. This can be seen with each of the themes in both countries. Russian business owners reduce their dependency on stakeholders by adopting a powerful posture, hoping to reduce the chance that stakeholders will take hostile actions. Unfortunately, this takes a continuous investment of resources involved in projecting strength, which concurrently reduces autonomy. For example, if a business owner always has to be present in order to prevent employees or team members from taking advantage of him or her, the autonomy to take a break or even a holiday is reduced. Administrative resources help to reduce dependency on government-related factors that infringe on decision rights. At the same time, this resource may demand a return of favors and may even insist on having decision rights (Ivy, Reference Ivy2013; Ledeneva, Reference Ledeneva2009). One way financial autonomy is obtained is by reducing dependency on the Russian institutional environment by channeling wealth to countries where institutions are more stable and reliable. This also helps business owners avoid negative consequences and unwanted attention that financial success may attract. For the same reason, some Russian business owners report that they try to be less vulnerable by staying under the radar or by choosing a venture based on human capital, which lends itself less easily to extortion.

Table 4. Autonomy as the outcome of ‘having’ and ‘needing’

For Dutch business owners, on the other hand, autonomy is about staying true to one's own values, beliefs, and mission. Having fewer material requirements serves to reduces dependencies and power resides in the ability to say no to threats to autonomy, particularly in relation to customers. A Dutch PSED study found that 60% of new ventures were initially run part-time and 80% of those were intended to remain so (Van Gelderen et al., Reference Van Gelderen, Thurik and Bosma2005). In the long run, however, a lack of revenue may reduce the viability of the business, and therefore the autonomy derived from it. Although business owners aim to reduce dependencies within decision-making realms by assigning clear and separate roles and responsibilities, having a partner could potentially lead to conflict. Yet, in the Dutch context, business partners are ultimately seen as enhancing autonomy. Finally, a Dutch business owner may sacrifice autonomy temporarily by taking on less favorable assignments in order to become more autonomous at a later stage; however, this runs the risk of becoming permanent if the business continues to be dependent on assignments initially thought to be temporary.

The majority of business owners take these actions of attaining power and reducing dependencies to promote autonomy because they feel that the benefits outweigh the disadvantages. As stated at the start of the findings section, the reported patterns represent the majority of respondents, in each country there are exceptions in terms of actions taken to further autonomy. For example, most Russian business owners will limit the autonomy of employees because they feel that employees will abuse their decisional freedom or turn it against the owner. However, a minority of the Russian participants argues that their own autonomy is strengthened if their employees have autonomy because it allows them to direct their attention to the aspects of the business they find most important and/or like best or because it provides them with more financial autonomy. If minority positions such as these become more prevalent, and there are initial signs that Russian HRM practices are beginning to change (Andreeva, Festing, Minbaeva, & Muratbekova-Touron, Reference Andreeva, Festing, Minbaeva and Muratbekova-Touron2014; Koveshnikov, Barner-Rasmussen, Ehrnrooth, & Mäkelä, Reference Koveshnikov, Barner-Rasmussen, Ehrnrooth and Mäkelä2012), a wider cultural change may be brought about (cf. Coleman's (Reference Coleman1990) bathtub model).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Our power-dependency model is at an early stage of theorizing (Weick, Reference Weick1995) and clearly more can and needs to be done. Notably, it is of interest which power enhancing and dependency reducing actions are most effective, in terms of the level of experienced autonomy as well as the subsequent effects on individual well-being and intended venture performance.

A further limitation of this study may lie in its timing. In 2015 and 2016, the Russian economy was hit by sanctions, low oil prices, and a devaluated currency. Yet, we do not believe this significantly affected the findings, as participants could discuss their experiences with autonomy over time and, on average, they had been in business for 10 years. Moreover, it is difficult to point to a period in the economic history of Russia during which conditions were easy for Russian owners of small and medium-sized businesses. Another limitation concerns the representativeness of the sample. Since the participants came from the networks of professors at two universities, they may have had more exposure to Western ideas than the average business owner.

Regarding future research, the finding that autonomy-motivated business owners in Russia are survival-focused calls into question the distinction between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship that is used in international comparative studies such as GEM (GEM, 2017). GEM studies have recently started grouping independence motives under a motive called, ‘improve oneself’ in opportunity entrepreneurship (GEM, 2017). However, our study shows that, in Russia, autonomy is mostly related to improving one's financial situation rather than the more personal developmental motive that GEM seems to assume. In light of this and of the differences in the meaning of autonomy between Russia and the Netherlands, it would be worth exploring whether autonomy takes on different meanings in other countries and whether more constructs used in international comparisons such as GEM vary in the way they are understood (Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, Reference Tsui, Nifadkar and Ou2007; Van der Vijver & Leung, Reference Van der Vijver, Leung, Matsumoto and Van der Vijver2011). As Rousseau and Fried (Reference Rousseau and Fried2001: 2) state, ‘It often takes researchers years to realize that they are labeling different things in the same way’. Hopefully our study helps to reduce this length of time. A further future research suggestion, given that the distinction between survival and self-expression cultural values explains the findings so well, would be to study the experience of autonomy and its determinants in countries that are extreme on the other axis used by the World Values Survey (2016) to classify cultures. This other axis is traditional (e.g., Qatar, Ghana) versus secular-rational (e.g., Japan). In addition, the World Values Survey shows countries in Southeast Asia, such as Vietnam, Thailand, and India, score approximately neutral on both dimensions, which raises the question of how business owners experience autonomy in these cultures.

CONCLUSION