I just want to say that if this can happen to a guy whose parents were virtually slaves, a guy from a broken home, a guy whose mother worked as a domestic from sun-up to sun-down for a number of years; if this can happen to someone who, in his early years, was a delinquent and who learned that he had to change his life—then it can happen to you kids out there who think that life is against you.Footnote 1

One week after being named the first Black player to be inducted to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Jackie Robinson penned this message “for all kids—not just youngsters of [his] race,” though he made no apologies “for being particularly interested in the youngsters of my own race for they belong to a minority which has been abused and held back for many years.”Footnote 2 The baseball player who broke Major League Baseball's color line in 1947 recognized the exceptional nature of his accomplishment but also wanted the young people who looked up to him to see how sports created opportunities for success and routes away from trouble.

In some ways, this notion that organized athletics occupied idle time and prevented crime can be traced all the way back to the 1618 Book of Sports in which King James I of England voiced his concern that an absence of sports on Sundays meant more idle time to be spent in alehouses.Footnote 3 But, as sports historians have shown, the notion gained particular traction in the United States during the Progressive Era, when athletics became “part of a social control movement designed to channel people, especially working-class and immigrant youths, into safe activities.”Footnote 4 Frontline social reformers such as Jane Addams implemented recreation and sport as a key feature at the Hull-House, a settlement house she co-founded with Ellen Gates Starr on the West Side of Chicago. Countless city youths, mostly white immigrants, who went to the Hull-House learned that “small parks, municipal gymnasiums and schoolrooms open for recreation, can guard from disaster.”Footnote 5 This model was duplicated at settlement houses and gymnasiums across the country, spreading a seemingly simple notion far and wide: that the value of sport lay in its ability to teach discipline, teamwork, and leadership for future responsibilities.Footnote 6

These efforts in fact often fell short because reformers sought to address character deficiencies instead of societal structures. “Reformers repeatedly described social problems as cultural in origin,” historian Eric C. Schneider argues, and “focused on providing delinquents with new cultural values while ignoring issues of economic inequality, power, and class.”Footnote 7 Nevertheless using organized sports to steer kids away from trouble gained even more popularity during the second half of the twentieth century. This history is much less known, and among the most unheralded athletes to commit time and money to combatting postwar juvenile delinquency from the earliest days of his professional baseball career was Jackie Robinson. His efforts ranged from various institutional endeavors to everyday conversations. Robinson, and his Dodgers teammate Roy Campanella, hosted numerous sports camps at the Harlem Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA); he wrote various newspapers columns on the problem of youth crime; he regularly called on athletes and celebrities to be more involved with youth organizations seeking to steer youngsters down the right path; and, in 1959, Robinson started a program, Athletes for Juvenile Decency, that connected professional athletes with young adults in schools, settlement and youth houses, the Police Athletic League (PAL), Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) groups, the YMCA, and other youth organizations. But it was not until he faced the issue firsthand as father of a son who was adjudicated as delinquent that Jackie fully understood the pervasiveness of youth crime, the shortcomings and, oftentimes, ill-intended consequences of using organized sports as crime prevention, and the level of societal commitment it was going to take to address the postwar youth crime problem.

For an exceptional athlete like Jackie Robinson, sports did keep him out of trouble, which gave him reason to believe in its transformational powers. But as historians of the carceral state have demonstrated, even well-intended crime prevention efforts can have detrimental impacts on the communities they serve if they increase police contact or expand surveillance structures that reinforce racial divides.Footnote 8 Too many historians have overlooked the ways in which organized sports were not free of these relations and indeed may have aided in the expansion of the carceral state by promoting a means of crime prevention that ignored structural failures and growing police power, which contributed to the social problems many youths faced.Footnote 9 These forces have created what I consider to be the carceral boundaries of sport.

While researching the criminalization of Black youth for my first book, I was struck by the way in which the state extended its surveillance powers through organized sports. So I developed this framework, the carceral boundaries of sport, to encourage scholars to consider the ways that the sporting world navigates the incessant growth of the carceral state. Mining sports archives for police presence offers invaluable insights, and largely untapped narratives, to demonstrate how police power has evolved in public and private ways to expand its reach, especially on account of increased police contact and extended surveillance. As historian Elizabeth Hinton contends, the foundational logic of American policing is to maintain the social order through “the surveillance and social control of people of color.”Footnote 10 Historians should extend this reasoning to sports by recognizing its ties to behavioral reform, state surveillance, exploitive capitalism, and police violence. Instead of seeing in organized sports the potential for crime prevention, I argue, we must search for how that assumption has, at minimum, failed to address the structural issues that contribute to many of the crime problems that youths faced, especially Black youths, amid an unprecedented growth of police power in the United States—and, at most, contributed to the growth of the carceral state.

This article analyzes these possibilities by examining not only how Jackie Robinson sought to combat juvenile delinquency through various organizational and individual efforts but also how his eldest son's struggles with the criminal legal system forced the Hall of Fame second baseman to confront the expanding, unrelenting reach of the carceral state. It was difficult for the public to understand how Jackie Jr., who did not fit the usually ascribed factors such as parental neglect and an unfavorable environment, became delinquent. But his encounters with the criminal legal system in the mid-twentieth century matched the lived experiences of many Black youths in the postwar United States. Tracing his father's efforts to grapple with that reality sheds important light on the often-unseen relationships between sports and the carceral state.

“A Hit with the Kids”: Robinson's Anti-Delinquency Work in New York City

By the time Robinson joined the Dodgers, others had set examples of how professional athletes could get involved with youth in their communities and join crime prevention efforts—not least the man who broke Major League Baseball's color line to hire him, the Brooklyn Dodgers manager Branch Rickey. Rickey was a child-saver, and though he never used the title, his efforts to use his baseball platform to keep kids out of trouble was very much in line with the Progressive Era movement. In 1917, when he was a front-office executive for the St. Louis Cardinals, Rickey organized the nation's first major league knot-hole club, a promotional effort that gave boys discounted or free tickets to attend ball games and special clinics.Footnote 11 Participation in the program thrived from the very first summer when roughly 30,000 youths gathered at Cardinal Field to watch the Redbirds.Footnote 12 For Rickey, adolescent boys were acting out not because they were bad, but because they were bored.Footnote 13 “It has always seemed to me that a boy's greatest enemy is idleness,” he said. “It's a damnable thing for boys to have to look for something to do, even to think about it.”Footnote 14 Thus for Rickey, the program prioritized boys but was about more than getting them to the ballpark and turning them into lifelong fans; it was an opportunity to incentivize less-advantaged youngsters to walk the straight and narrow with “two rules for attendance: (1) No boy could attend without his parents’ consent; [and] (2) No boy could skip school to attend.”Footnote 15 Knot-hole clubs brought fun, but they also brought surveillance, and they went with Rickey to New York City when he joined the Dodgers in 1942.Footnote 16

But Rickey, like many reformers, failed to account for the changing demographics of U.S. cities after World War II and how this reshaped the racial make-up of the “boy delinquency problem.” By 1950, nearly two-thirds of the U.S. population was urban or suburban, and, by 1960, 64.6 percent of the Black population lived in metropolitan areas.Footnote 17 But the youths who participated in knot-hole clubs were almost exclusively white boys between 10 and 18 years old. Rickey and the Dodgers’ inability to reach Black youths—increasingly the city's primary cause for concern—changed when Robinson signed with the club in 1945. In his first season with Brooklyn, Robinson expressed interest in fighting juvenile delinquency with a boys’ club and, like Rickey, he believed an occupation of idle time was key.

Admitting he was “no angel,” Robinson often reminisced of his childhood mishaps in Pasadena, California, and blamed them on “the fact that his mother worked late and he had too much free time on his hands to keep out of mischief.”Footnote 18 As a member of the Pepper Street gang, Robinson recalled, “hardly a week went by when we didn't have to report to Captain Morgan, the policeman who was the head of the Youth Division.” Though there are no reports of a young Robinson having ever been involved in serious crimes, he often regarded the idle time as ripe for youthful mischief. “We threw dirt clods at cars,” Robinson detailed, “we hid out on the local golf course and snatched any balls that came our way and often sold them back to their recent owners; we swiped fruit from stands and ran off in a pack; we snatched what we could from the local stores; and all the time we were aware of a growing resentment at being deprived of some of the advantages the white kids had.” Acknowledging that he was treading a fine line, Robinson realized, “I supposed I might have become a full-fledged juvenile delinquent if it had not been for the influence of two men who shared my mother's thinking.”Footnote 19 Those two men were Carl Anderson, a neighborhood automobile mechanic, and Reverend Karl Downs, whose lessons encouraged the young Jackie Robinson to trade the street corner for the church and to trade gang life for team sports.Footnote 20

This part of Robinson's early life shaped much of his approach to the antidelinquency work he picked up when he joined the Dodgers. From the outset of his efforts, he stressed “the value of good character, dignified behavior and sportsmanship as virtues for all Negro youngsters,” and told a reporter from Ebony Magazine that he “sees his own baseball career as a step forward in giving them an opportunity.”Footnote 21 Robinson spoke on several occasions about wanting to commit time to fighting juvenile delinquency specifically, though it was not until his second season with the team that he started to do so in a more structured manner.

In September 1948, Robinson and Campanella, his Dodgers teammate and the second Black player to be called up by the team, signed contracts to coach boys’ clubs at the Harlem YMCA during the baseball off-season. Their duties included leading clubs in indoor baseball, basketball, and other activities. But this position was about more than coaching young athletes. “Both Roy and I like this kind of work,” Robinson told a reporter from the New York Times, “and we are both crazy about children. Since both of us have children of our own we are proud to be getting this chance to work at a job so near our hearts.”Footnote 22 Jackie and Campy—a popular handle used to refer to the duo—invested in the youths at the Harlem YMCA not only because they hoped to inspire New York City youths to stay out of trouble but also because they saw themselves and their own kids in them.

Already an important social and cultural center in New York City, the Harlem Branch YMCA became by the 1950s, under the leadership of Rudolph J. Thomas, the largest community-based institution committed to combatting juvenile delinquency. Thomas, who started working at the Harlem YMCA in 1920 as an elevator operator, exhibited drive and persistence when he assumed the Y's executive director position in 1947, improving its activities, membership, and facilities.Footnote 23 Yet few of Thomas's accomplishments measured up to signing Jackie and Campy to run clubs to promote indoor baseball, basketball, and other competitive sports in 1948. Thomas's intentions when he added Jackie and Campy to the Y's staff were clear and direct. They “should be helpful in the fight against juvenile delinquency,” he explained. Their presence would “do more to influence the boys of the community for good than any previous experiment which has been used.”Footnote 24

From a sheer-numbers perspective, he appeared to be right. Hundreds of youths rushed to inquire about Harlem YMCA memberships and how they could become eligible for the Jackie Robinson–Roy Campanella Competitive Clubs. Other youths requested information regarding the basis upon which a few youngsters will be eligible to appear on Jackie Robinson's radio show. “Youngsters throughout the community are coming in daily,” Thomas claimed, “inquiring how they can learn ‘from our big league heroes.’”Footnote 25

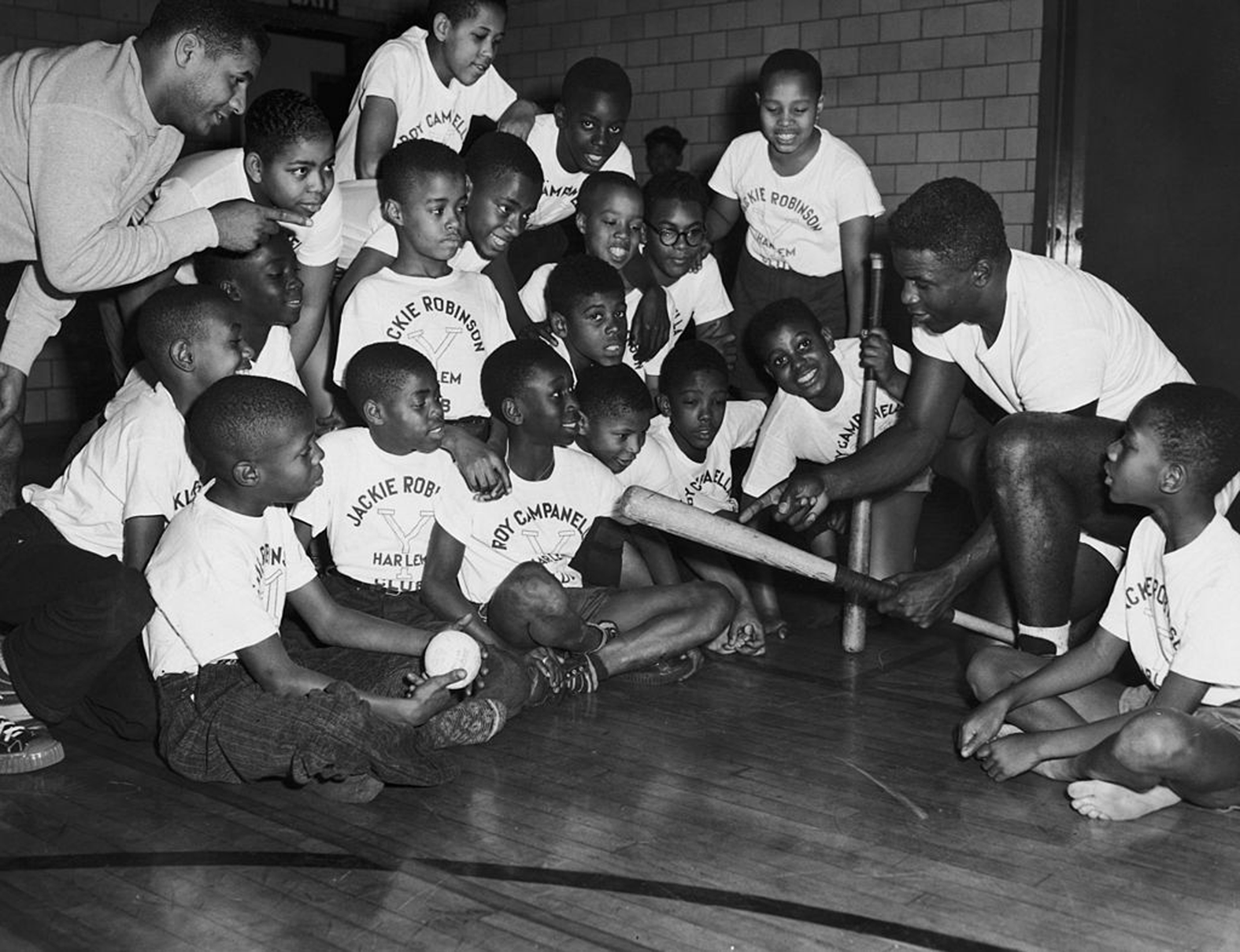

Young people flocked wherever Jackie and Campy made an appearance (Figure 1). At the Harlem Y, though, their appearance became the norm. They worked from 1 to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday and from 10 a.m. until 2 p.m. on Saturdays. Their goal was to be considered “just another pair of workers” at the Y, while understanding their position was also to attract large numbers. In their first year, the Harlem Branch experienced significant growth. Robinson and Campanella led classes and clubs, coached various sports, and made hundreds of speeches at schools and churches. From November to February, Jackie and Campy spoke to over 30,000 student-aged youths and numerous adult groups. “In every possible way,” according to the Harlem Y's chairman Alan L. Dingle, “they directed the attention of youngsters to the principles of clean living, clean speech and clean sportsmanship.” When their first season at the Harlem Y came to its end in February 1949, some 200 kids “put together their pennies, nickels, and dimes to give them a farewell party.” The youths presented Jackie and Campy with plaques “in appreciation of meritorious services rendered.” Campanella, choked up, managed to tell the kids, “No words can ever express what this award means to me.” And Robinson, speechless for a moment, professed, “You know, I really got more out of being with you than you got out of me. Of course, I'll be back next year.” And there was hardly any doubt that the YMCA wanted them back.Footnote 26

Figure 1. Brooklyn Dodgers Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella (left) demonstrating some baseball techniques to children at the YMCA in Harlem, November 17, 1948. Photo by Al Gretz/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images.

In 1948, the membership at the Harlem Y reached 4,537, which was an increase of more than 500 permanent members over 1947. This included almost 9,000 young men and women who were enrolled at some point during the twelve-month period. The growth in membership meant a growth of revenue and, by the fall of 1949, that revenue was used to remodel the building “from the basement to the roof,” making the Harlem Y “one of the best” in the nation. More than 10,000 gathered in the street for a ceremony devoted to the institution's rededication. Among those who shared congratulatory words was General Dwight D. Eisenhower, then president of Columbia University, who “noted the progress of Negroes despite serious handicaps,” “lauded the Y's role,” and said the newly renovated building was “Americanism at its best.”Footnote 27 Yet “Americanism” was never really the goal. Sports encouraged youths to take instructions and follow rules, which was crucial if the goal was to curb juvenile delinquency in the city.Footnote 28

Following his success at the Harlem Y, Robinson expanded his efforts to reach youths through other outlets and avenues that he believed held the most potential to make change regarding postwar delinquency problems. The Dodgers all-star worked to develop new projects in cooperation with various New York City schools, the PAL, the CYO, and the Young Men's Hebrew Association. Building on the camps and radio show that he implemented at the Harlem YMCA, by the 1950s, Robinson hoped by branching out beyond the Harlem Y that he would be able to utilize different platforms to reach a wider audience. This included a regular newspaper column for the New York Post and a nationwide program, Athletes for Juvenile Decency, which built on the organized efforts of the Boys’ Clubs of America.Footnote 29

“It would be easier, perhaps, just to go ahead and enjoy life and take no interest in politics, or juvenile delinquency, or race relations, or world affairs,” Jackie Robinson wrote in his debut newspaper column for the New York Post on April 28, 1959. “In fact, I've sometimes been told: ‘Jack, if you'd only kept your mouth shut, you've have won even more honors than you have!’” But after retiring from baseball in 1956, Robinson's off-the-field work expanded even further. Penning a regular New York Post column, which at the time was considered a liberal news outlet, gave him an important platform with extensive reach. Robinson regularly reminded his readers that he did not “speak for all other Negroes, any more than other columnists speak for all those in whatever their racial, religious or nationality group,” but he understood his privileged status allowed him “to speak to so wide an audience concerning just what we feel and think” that it was too significant an opportunity to pass up.Footnote 30

In his thrice-weekly New York Post column, Robinson sometimes offered his perspective on the problems of delinquency that continued to plague the nation—a perspective that was shaped mostly from his earlier work at the Harlem YMCA. “One out of every five youngsters in the country between the ages of 10 and 17 had some brush with the law,” Robinson wrote on May 5, 1959. Certainly for anyone who may not have been paying attention to postwar youth crime rates, these numbers may have been alarming. Even as antidelinquency efforts increased in the 1950s, Robinson recognized “our juvenile delinquency rate is high, and growing higher every year.” He was right. From 1948 to 1959, arrests of juveniles increased six times as fast as arrests of adults. “It's frightening to think that sooner or later one of your own children, or one of the neighbor's, or one of your relatives’ youngsters,” he prophetically detailed, “will wind up in a police station charged with some offense against the public good.” Instead of dwelling on the numbers, though, Robinson rightly directed attention to the fact that print media too often emphasized “the 4 or 5 per cent who do get into serious trouble, and [that] more attention [should be] paid to the great majority who don't.” He identified the work of two individuals, Dorothy Gordon and Reverend Osborne, who worked to prevent “the ‘JD’ rate” from continuing to rise. Gordon, who conducted the New York Times “Youth Forum” on TV, encouraged youngsters to “just be what they are—young people, with the accent on people.” For Robinson, “Miss Gordon” built up a very effective way of reaching and dealing with kids by “simply recognizing them as individuals, just as adults like to be recognized.” On the other hand, Rev. Osborne used his church and accompanying community center in Stamford, Connecticut, to keep youngsters out of trouble. “Since it is more difficult to rehabilitate youngsters who have reached 16 and 17,” Rev. Osborne suggested, “getting them to come to the church, the temple and the community center at an early age is the best possible way of keeping them out of difficulty.” It was going to take this kind of communal work, according to Robinson, to curb juvenile delinquency.Footnote 31

Not all of Robinson's New York Post columns dedicated to delinquency were as optimistic as his first. For example, in his May 15 column, he shared his perspective on the criminal justice system more broadly, especially prisons. Centered around an interview with Robert Neese, who published the book Prison Exposures, which detailed his own prison experiences, Robinson expressed his concern about the justice system's inability, or its lack of interest, to reform incarcerated people. Robinson was a member of the Connecticut Parole Board, so he was “already aware of some of [the] problems” that Neese shared. Neese told Robinson he first got into trouble when he was nine years old.Footnote 32 “[Neese] and his companion found themselves with lots of time on their hands and nowhere but the streets to spend it,” according to Robinson. “So they attempted to break into a school gymnasium in order to play basketball, and in so doing set the school on fire.” From there, it was “just one scrape after another” until he landed in reform school. But for Neese, “Despite the ‘reform’ in the school's name, it was the most thorough school for crime he has ever seen.” Neese admitted to Robinson that he learned more about picking locks and stealing cars than anything else: “There wasn't the slightest attempt to actually reform anybody.”Footnote 33 For Robinson, this fit perfectly into the narrative of how a delinquent turned into a criminal. Idle time was compounded by the lack of available recreational spaces for the youth, which turned into the initial contact with law enforcement. Unfortunately, for Neese, this eventually led to a ten-year term for burglary in the Iowa State Prison.

In a later column, Robinson reiterated a similar message and called on those who were able to contribute financially to these organizations to do so. “Whether it's the Knight of Pythias, the YMCA, the YMHA, the Boy Scouts, the Camp Fire Girls, or any of the many others isn't at all important,” Robinson wrote. “The important thing here is the lives and limbs of our kids.” These organizations and their efforts to keep kids safe and occupied during the summers deserve our support, according to Robinson:

But they don't need me to speak for them. They'll be out seeking your contribution themselves very soon. And when they do, I hope you'll stop a moment, as I did, and think about those kids playing stick-ball in the street. And particularly if you're a driver, I hope you'll join me in helping to send them to summer camp, if only for a week or two.Footnote 34

These calls for financial support would soon be extended to other professional athletes who Robinson believed needed to utilize their platforms and their privilege to give back.

Putting money where his mouth was, Jackie Robinson regularly matched his energy toward antidelinquency efforts with his dollars. For example, in February 1958, when the Harlem Branch YMCA appeared to be well under its $100,000 financial campaign, “Old ‘42’ stepped up to the plate … and slammed $55,000 cash dollars down on the speaker's podium for the greatest homerun he had ever fashioned.” The $100,000 goal was “more than twice the amount it [had] ever raised,” but for Black New Yorkers, many in attendance in the final night of the drive, “raising this huge sum of money by Harlemites demonstrates an increasing awareness among Negroes to shoulder their responsibilities in an atomic age.” And Robinson knew other professional athletes ought to be able to contribute in similar ways.Footnote 35

In September 1959 Jackie Robinson gave congressional testimony on juvenile delinquency and shortly thereafter participated in a WABC radio panel discussion on the subject with New York City Mayor Robert Wagner, former Davis Cup captain Billy Talbert, Carl Braun of the New York Knicks, and sportscaster Howard Cosell. “Most ‘problem’ kids came from broken homes, and had no one to turn to,” Mayor Wagner opened the discussion. “They are often more than ready to transfer their need for guidance, and their desire to ‘belong’ to someone else. Too frequently, this someone turns out to be the gang leader,” he explained. And, this was important, because Mayor Wagner publicly viewed himself as a proponent of youth culture and opponent of juvenile delinquency. Such a perception aligned with Robinson's own conviction that it was vital for professional athletes to fill in for said influence. “By giving them positive ‘heroes’ they know and could talk to,” Robinson believed, “they could greatly aid in guiding these kids’ normal aspirations for fame and status into wholesome, progressive channels.”Footnote 36

Robinson was certain of this because he had already “seen this technique work.” On the radio, the retired baseball player recounted his Harlem Y experiences and how he and Campanella were able to reach the kids. “Not just certain kids,” which appeared to be a push-back toward the New York City mayor's “problem” descriptor, “but all kids—kids from broken homes, kids from good homes, the ones from slum neighborhoods and the ones from good neighborhoods.” These regular, face-to-face interactions with youths encouraged them to emulate their heroes, who, in return, inspired them to stay out of trouble and to develop constructive ideals and aspirations. Talbert and Braun agreed and, “thus, on the spot, ‘Athletes for Juvenile Decency’ was created.” Building on the organized efforts of Boys’ Clubs of America, Athletes for Juvenile Decency was a committee that served to bring athletes together with youngsters in schools, settlement and youth houses, PAL and CYO groups, and other youth organizations. Mayor Wagner served as the head of the committee; however, it would be the professional athletes who participated that made it grow into a national movement.Footnote 37

Four weeks later, Robinson reported that the committee was “off the ground now and seems to be moving exceptionally well.” Thanks in large part to the organizational efforts of Cosell and Ed Silverman, who helped to coordinate the athletes, Athletes for Juvenile Decency received scores of letters from other athletes willing to participate. “Having three children who will, in a few years, be at the age where they, too, could possibly be swayed the wrong way,” the New York Yankees All-Star pitcher Whitey Ford wrote, “I am very much interested in such a program.”Footnote 38

Robinson, Mayor Wagner, and Andy Robustelli of the New York Football Giants hosted the first Athletes for Juvenile Decency program on January 27, 1960, when the trio visited the City Youth Board's East Harlem Meeting Room. As the men walked around “the teen-age couples who were dancing to rock ‘n’ roll music,” the youths hardly paid them any attention. The youngsters eventually opened up to Robinson and Robustelli, and they asked questions about sports and “talked about ‘the slot,’ a rock ‘n’ roll dance they had invented.” The mayor, on the other hand, was not received in the same manner. “There was not a ripple of reaction,” according to a New York Herald Tribune report of the event, “when the Mayor walked in and mingled with the youths.” Unphased by the cold shoulders, Mayor Wagner told Herald-Tribune reporters, “We're showing someone cares. The word will get around.” Robinson and Robustelli were just as optimistic. “The problem with most of us,” Robinson said, “is that we give up too easily.… If I can get to one, that will be of help.” The three men left the event believing the program was off to a good start.Footnote 39

The Problems of Crime and Delinquency Come Home

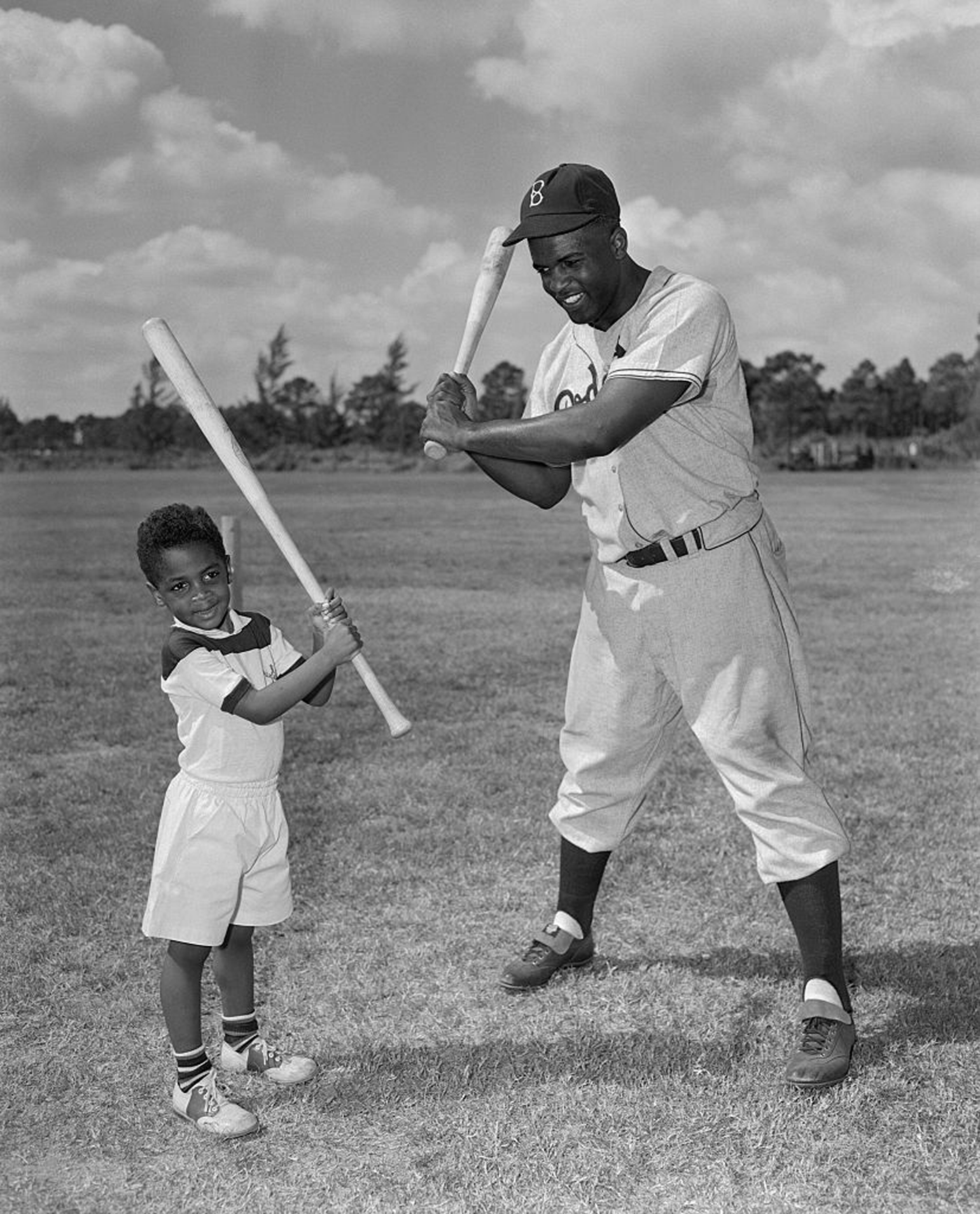

Robinson believed in the transformational power of organized sports not only because of the influence it had on his personal life but also his ability to reach countless others with the message (Figure 2). Its impact, however, was tested by his eldest son, Jackie Jr., whose repeated run-ins with the police, and subsequent early death, forced the Dodgers Hall of Famer to accept an unfortunate reality: the magnitude of crime and delinquency problems in the United States outweighed any solutions that sports offered.

Figure 2. Brooklyn Dodgers second baseman Jackie Robinson teaches his eldest son Jackie Jr. how to hold a bat. Photo by Bettmann.

The first of Robinson's three children, Jackie Jr.'s early years in school were tumultuous and, before long, his disdain for schooling “earned him the reputation of being a troublemaker.”Footnote 40 Rachel Robinson, his mother, took up the task to help Jackie Jr. stay on track and “had endless and seemingly fruitless conferences with the teachers,” Robinson wrote. “Her efforts to help Jackie [Jr.] with his homework were untiring.” He displayed an interest in athletics and enjoyed playing little league baseball, but Jackie Jr. was regularly taunted “not so much by the youngsters as by their parents, who made loudly vocal comparisons between the way [he] played and the way [Jackie Sr.] played.” According to Robinson, they tried everything. “We had conscientiously tried not to submit Jackie [Jr.] to the pressures a lot of parents put on their children,” Robinson wrote. “We didn't demand high marks or a super performance.” They tried therapy for several months, “until he decided it was of little value,” and when Jackie Jr. was twelve, they tried psychological testing. The results “showed that he was a normal boy” and that the Robinsons had little to worry about—except for raising a Black boy in the postwar United States.Footnote 41

Jackie Jr.'s poor grades became “a real disaster,” and, per the recommendation of a close friend, the Robinsons decided to send their son to boarding school. “Jackie [Jr.] seemed to need more freedom,” Robinson wrote, “but at the time he probably needed more guidance and structure.” This turned out badly, and “his stay at the school ended abruptly when he was suspended for breaking too many of the school rules.” When Jackie Jr. returned home from the boarding school “he seemed lost,” and when he was seventeen, he decided to hitchhike from Stamford, Connecticut, to California with a friend. Hoping to find employment as migrant farm workers, the two realized “they had arrived during the wrong season.” Jackie Jr. returned home and “made it clear that his running away was not a sign of rejection … he had to get away and see if he could get by on his own.” A few months later, he dropped out of high school and volunteered to join the Army with hopes “to pull himself together, get the discipline he knew he needed badly, and establish his own identity.”Footnote 42

In less than a year, Jackie Jr. was shipped to Vietnam. The young Robinson, like many African American soldiers who were deployed during the war, saw combat firsthand.Footnote 43 He arrived in Vietnam in July 1965 with the 1st Infantry Battalion and served from then on with front-line units. In November, “A Vietcong mortar shell exploded near him spraying the area with shrapnel and killing his two best pals.” Jackie Jr. “miraculously escaped with only minor injuries.” According to his father, he shrugged off the various portrayals of the heroics. “I just got shrapnel in the ass,” the senior Robinson recalled his son telling him, but the reports indicated a traumatic experience. The young Robinson received a Purple Heart as a result of the battle.Footnote 44

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Jackie Robinson never took a public stance against the Vietnam War and “felt strongly that those who opposed the war had no right to call the black kids who served in it willing dupes of imperialism and to ridicule and denigrate our men.” As an Army veteran who served during World War II, Robinson empathized with Black soldiers “who sought opportunities in the Armed Forces that were denied them in civilian life.” And though he understood why a civil rights leader like Martin Luther King, Jr. opposed the war, even after Rev. Jesse Jackson pointed out that “Dr. King was against the war but not against the soldiers,” Robinson thought it was a contradiction to confine “criticism to the deeds of the U.S. and to ignore the deeds of the Viet Cong.”Footnote 45 This was amplified while his son was in the hospital recovering. The elder Robinson watched his son realize the contradiction of having fought for freedom abroad while being denied full citizenship at home. “Jackie [Jr.] supported the war,” Robinson wrote, “but he didn't buy a system of government that preached democracy in Vietnam but had neither homes for blacks in certain neighborhoods nor jobs for the black veteran in certain areas like the construction industry.”Footnote 46 Perhaps worse was that Jackie Jr. returned home with a drug addiction that his father had yet to learn about.

On March 4, 1968, “the roof fell in” on the Robinson family when a reporter from the Associated Press called Jackie Robinson and asked, “Don't you know that your son was arrested about one o'clock this morning on charges of possession and carrying a concealed weapon?”Footnote 47 Robinson was stunned. Based on the reports, Jackie Jr. was arrested by a detective of the Stamford Police Department's narcotics division near the Allison Hotel. “Police said Jackie Jr. fled when the detective called to him but was captured after a brief chase,” according to a report. “Police said they found several packets of heroin inside a portable radio. A pouch of marijuana also was found on the suspect … as well as an Italian made .22 caliber revolver.” The 21-year-old was arraigned on the charges and tried to plead guilty; however, the judge told him it was not the proper time, and a court hearing was set for the following Monday. Jackie Robinson paid the $5,000 bond and bailed his son out of jail. He told reporters, “We have obviously failed somewhere” (Figure 3).Footnote 48

Figure 3. Jackie Robinson follows his son, Jackie Jr., out of Stamford circuit court following his son's arrest for possession of a firearm and drugs. His wife and daughter, Rachel and Sharon, respectively, are behind the two men. Photo by Bettmann.

Jackie Robinson was not stunned because his son had been apprehended by law enforcement. As one reporter from the Pittsburgh Courier underscored, the Robinsons “were going through the same teen-age delinquency problems that many other Negro families in the ghettos [were] experiencing.” A longtime Los Angeles Sentinel writer A. S. “Doc” Young added, “Their predicament, in fact, [was] being shared by many well-to-do parents of all races throughout America.” Before he joined the army, Jackie Jr. had gotten himself into minor scrapes with the law. And though these charges were more severe, Robinson assured his son that he and his mother were behind him, “but he's got to take this punishment” and shoulder the consequences of the mistakes.Footnote 49

What concerned Jackie Robinson the most about Jackie Jr.'s arrest was the drugs. When Jackie Jr. was discharged from the service, Robinson was worried about his son; however, he felt their communication improved. “He was most persuasive when he frankly admitted using marijuana, warning us that there was no point in our forbidding him to use it, telling us that he liked grass, that he was not going to give it up,” Robinson recalled. “We didn't have a thing to worry about in terms of his sticking a needle in his arm. He was afraid to stick himself with needles. It would never get to that. Not with him.” After posting bail, the Robinsons decided to put Jackie Jr. in the psychiatric section of the Yale-New Haven Hospital. Because Rachel worked on campus, she could see that Jackie Jr. received proper attention. But the young Robinson knew otherwise. “You're really just wasting your money,” he told his parents. “I'm the only addict here. The other people have mental problems. I need to be with some people who have the same kind of problems I have. That way we could learn from one another, help one another.” In advance of his trial, Jackie Jr. admitted one of his father's greatest fears—he was addicted to heroin.Footnote 50 The judge agreed and on May 7 ordered that the prosecution of the young Robinson be delayed for two years. Jackie Jr. was found to be a “‘narcotics-dependent person’ … and was ordered to undergo treatment and rehabilitation for two years.” Jackie Jr.'s road to recovery began at the Daytop program; Jackie Robinson's personal experience with delinquency deepened.Footnote 51

Jackie Jr. spent a little over two years doing rehabilitation treatment at the Daytop Center in Seymour, Connecticut. The “oldest and largest drug-treatment program in the United States,” Daytop is based on the therapeutic community model, a “residential treatment, in which addicts help[ed] other addicts kick their drug habits by living together in a drug-free environment that emphasizes hard physical work, counseling and communication.”Footnote 52 This proved to be an effective model for Jackie Jr. “I have found a lot of direction now in my life,” the young Robinson stated in his testimony before the United States Senate Sub-Committee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency on October 30, 1970. “I was involved in a lot of other programs before I came to Daytop and I have found that for me this has been, I think, the only effective change.”Footnote 53

Jackie Jr. had come clean about his addiction. His congressional testimony, which came days after President Richard Nixon signed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 and was part of an effort to pass another bill that authorized members of the Armed Forces to be discharged from active military service by reason of physical disability when such members suffered from drug addiction or drug dependency, marked a critical moment in his transformation.Footnote 54 For the young Robinson, his time in the Army worsened his connection to drugs and they offered no corrective support. “I was a pretty mixed-up kid when I went into the Army,” Jackie Jr. testified. “If I had received the proper type of help, I might not have gone to the extent that I went to and my involvement with drugs and my involvement with other crimes and a lot of the activities I was involved with.” He called on the government to support programs like Daytop, which decriminalized drug addiction, with not only legislation but also funding. The government, according to Jackie Jr.,

… [has] been looking at the problem and treating these people as criminals. Addicts are not criminals. I feel we are people who are sick. I feel that drug addiction is the symptom of a problem. The problem, the sickness must be treated. To look at this as a crime is really wrong and it will not solve the problem. I think it is part a reflection of a lot of the confusion we find around us in society today.

Reflecting on his privilege, the young Robinson discerned, “I think a lot of people now who are being sent to jail really should not be and a lot of people who aren't being helped at all who should be.” Daytop helped Jackie Jr. and he believed “that the government should allot more money to different drug programs so that we in the programs could handle a larger input of people who are using drugs.” The transition from rehabilitant at Daytop to employee made Jackie Jr. realize “they could probably do a lot more if [they] had more funds.” The elder Robinson agreed.Footnote 55

Like Jackie Jr. though, Robinson was disgruntled by not only the lack of support Daytop received but also society's inadequate solutions to a growing drug problem. He was thankful for his son's growth at Daytop. “I don't have the words to pay tribute to what the Daytop experience did for him,” Robinson wrote. “And while he was learning, we were learning that the Daytop philosophy is perhaps the one viable approach to the narcotics addiction problem.” More than a decade after his playing days, Robinson saw an opportunity for sports to get involved. “I went to the baseball commissioner [Bowie Kent Kuhn],” Robinson recollected. “I thought that, since the drug problem is a big problem among our youth and since baseball has many young fans, it would be a great idea for baseball to indulge in a creative and constructive program, at least an educational program.” Robinson suggested to Commissioner Kuhn that “at time when games are not being televised—and even when they are—the baseball idols of young people could say a word about the perils of drugs.”Footnote 56 Robinson was given the courtesy and attention from the commissioner's office and in March 1971, Major League Baseball launched the first organized drug education program in team sports history, a “preventive program aimed at aiding and educating youngsters in how to avoid the drug scene,” as Commissioner Kuhn explained it.Footnote 57 At that season's World Series, television ads in between innings warned youngsters, “When you're high on pot, acid, or speed, you can't concentrate on whether the ball is high or low, fast or a curve, inside or out. Don't let people talk you into trying things.” The National Football League and the National Collegiate Athletic Association followed suit with their own antidrug programs.Footnote 58 But this was not what Jackie Robinson intended. “Given the scope of the problem and the resources of the business,” he felt the campaign had not been adequate.Footnote 59

What was not inadequate was the work that Jackie Jr. continued to do while on the staff at Daytop. “He had been clean for three years,” Robinson recalled, “and he spoke with authority about all that he had been through—about the way he had become an addict, the reasons for it, the hell into which he had been plunged as an addict—stealing, robbing, pushing dope, pimping—anything to get the money for dope.” For Jackie Robinson, the journey was worth it. “That single moment paid for every bit of sacrifice, every bit of anguish,” Robinson wrote. “I had my son back.”Footnote 60 This caused Robinson not only to reflect on his son's journey and the family's journey, but on the antidelinquency work he had been committed to off the field since the beginning of his playing days with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Jackie Robinson learned, through his son, that the fight against juvenile delinquency started at a young age but required a sustained effort into adulthood to see substantive change.

Jackie Robinson Jr. was killed in the small hours of the morning on Thursday, June 17, 1971. On his way home from New York City, his “car spun out of control, slammed into an abutment, severing guard rail posts and crashing to a halt, leaving Jackie pinned under the wreckage, his neck broken, his life swiftly fading when the state police arrived a little after two o'clock that tragic morning.” He was 24 years old.Footnote 61

The sudden death of Jackie Jr. left a void in the Robinson household, but it allowed them to learn about the impact he was making with others. Days before the accident, Jackie Jr. was the Youth Day speaker at the Nazarene Congregational Church in Brooklyn where he participated in a dialogue sermon with Rev. Samuel L. Varner on “the story of his life as an addict, his rehabilitation and the work that he [was] now doing in the Daytop Program.” The program awarded more than $18,000 in college scholarships and awarded six other high school graduates with the Nazarene incentive award.Footnote 62 This was just part of the work that Jackie Jr. had been doing since he started working as a full-time staff member at Daytop. “He made great contributions to Daytop and to the community,” Kenneth Williams, the executive director of Daytop said of the young Robinson. “His death was a ‘great loss.’” The police report also confirmed what Williams promised Jackie Robinson: Jackie Jr. “was not on dope.”Footnote 63

The Robinson family also received affirmation of Jackie Jr.'s impact by the countless letters, telegrams, and phone calls they received. This included childhood friends who made diligent efforts to attend the funeral but also from the people at Daytop. “I'm thirty-three and he was twenty-four,” an unnamed person told Jackie Robinson. “But often, when we were having dialogue, I got the feeling like he was thirty-three and I was twenty-four.” Another forty-year-old member of the Daytop community wrote the Robinsons to express “what it had meant to him in terms of being black to have Jackie [Jr.] working with the program.” These messages, according to Robinson, “took some of the pain away to see the contributions he had made.”Footnote 64

The day of the accident, Jackie Jr. had been working on plans for a music festival for the benefit of Daytop to be held at his parents’ home. “The Robinsons thought it over, and going ahead with the concert seemed to be the right thing to do,” the elder Robinson told Bob Johnson of the Los Angeles Times. “So, on a sunny summer afternoon, just five days after the funeral, the green lawns of the Robinson home were filling with people.” The concert was a huge success. More than $40,000 was raised by the more than 3,000 people who attended the “star-studded benefit.” Among the artists who performed were Roberta Flack (Jackie Jr.'s “idol”), Herbie Mann, Dave Brubeck, Billy Taylor, Terry Gibbs, and Leon Thomas; speakers included the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Bayard Rustin, Mrs. Arthur Logan, as well as his brother, David. In a moving and dramatic talk, Jackie Robinson “expressed his thanks and explained since the affair had been a dream of Jackie Jr. who had worked so hard on the arrangements, he felt unable to cancel it.” Throughout the day, the audience cried, laughed, cried, and prayed, and the Daytop director concluded the event encouraging everyone in attendance to remember Jackie Jr. “as a beautiful black young warrior.” Certainly, the elder Robinson obliged.Footnote 65

“I shall never get over the loss of Jackie,” Robinson wrote. Confounded that he spent much of his life trying to reach other kids and, then, having to deal with the weight of losing his own, it is difficult to know just how much of an impact this had on the health of the Hall of Famer, who died the following fall. He was only 53 years of age.Footnote 66

Sports History and the Carceral State

For Jackie Robinson, baseball was his ticket. He believed, like many others, that sports not only had the ability to occupy the idle time of youngsters who might otherwise find trouble where they lived, but also, if they were lucky enough, it had the ability to change their lives for the better. And he was not wrong. The challenge, however, was that sports were never designed to address the structural issues—poor housing, disproportionate access to education, inadequate healthcare, income inequality, racial profiling, racist drug laws—that contributed to the social problems that many Black youths faced. In fact, his son's firsthand encounter with the criminal legal system was emblematic of Black youth encounters with a growing carceral state, fueled by the War on Drugs, during the second half of the twentieth century.

This understudied part of Robinson's biography offers a glimpse of the possibilities for future research that can bring together two seemingly disparate histories, those of sports and the carceral state. To examine the carceral boundaries that govern the sports world, we need to be more attentive to how we research, write, and teach about the police in non-police spaces—for example in stadiums and recreational centers or through the work of Police Athletic League—as well as how non-police authorities have been empowered to carry out police-like functions, such as professional sports league commissioners and other governing sports bodies.

We also need to be, like Amira Rose Davis, “interested in histories of the bad, the messy, the mean.”Footnote 67 Prominent athletes, such as Jackie Robinson, have been written about in great depth often because their biographies exemplify the best (read: progress) the United States has to offer. But they can also provide a valuable lens to view the limits of triumphant sports histories, similar to how Jackie Jr.'s story serves as a unique way to study the war on drugs. Or, as Theresa Rundstedtler puts it in her article on college athletics and the war on drugs, “The broader war on drugs and the exploitation of black ‘student athletes’ are not two separate phenomena, but rather two sides of the same neoliberal, carceral coin.”Footnote 68 As the legendary Chicago youth sport authority Larry Hawkins told a reporter from Sports Illustrated in the early 1990s, “People at the top of sports talk about the subject as if the bottom wasn't there.”Footnote 69 One way to foreground the histories from “the bottom” is to recover and center the stories of the countless athletes whose careers were cut short for whatever reasons, including run-ins with the expanding carceral state.